Introduction

Stylosanthes viscosa (L.) Sw. (Fabaceae) is a herbaceous legume with a native range that includes much of the Neotropics, from Argentina to Texas and several West Indian islands (POWO 2024; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Reid, Schultze-Kraft, Sousa Costa, Thomas, Stace and Edye1984). Non-native populations of S. viscosa are known from Africa, Asia, Australia, and Hawaii (POWO 2024). Except for native populations in Texas, there are no published records of S. viscosa growing outside cultivation in the continental United States. There are, however, records of this species being cultivated in Florida to test its potential usefulness, for example, as forage for livestock, most notably at the Agricultural Research Center, Fort Pierce (ARC-FP; now the Indian River Research and Education Center [IRREC]) in St Lucie County, FL. Kretschmer and Brolmann (Reference Kretschmer, Brolmann, Stace and Edye1984: 470) wrote that S. viscosa “have been growing at ARC-FP since 1976 in a Pangola sod. S. viscosa is early flowering, produces abundant seed, and spreads easily.” Lenne and Sonoda (Reference Lenne and Sonoda1982) studied the pathogenicity of Colletotrichum spp. fungus on several different species of Stylosanthes, including three lines of S. viscosa originally from Brazil and growing in field plots at the Agricultural Research Center, Fort Pierce, Florida. Vouchers for two of these lines are deposited at the University of Florida Herbarium (FLAS) (the third S. viscosa line grown at Fort Pierce was designated IRFL 1713; Lenne and Sonoda Reference Lenne and Sonoda1982).

St Lucie Co.: “Herbarium of ARC Ft. Pierce, No. 336, IRFL 1692, Ibirarema, Brazil (Paul Rayman) 1973, IRFL BLK 2E, 1/24/75, Dr. A.E. Kretschmer, Jr.”

St Lucie Co.: “Herbarium of ARC Ft. Pierce, No. 379, IRFL 1712: Fazinda Schrefferdecker, Marilia, S.P. Brazil, Jan. 1976, Dr. A.E. Kretschmer, Jr.”

There are three other Stylosanthes species known from the southeastern United States: sidebeak pencilflower [Stylosanthes biflora (L.) Britton, Sterns & Poggenb.], cheesytoes [Stylosanthes hamata (L.) Taubert], and Everglade Key pencilflower Stylosanthes calcicola Small. One character that distinguishes S. viscosa from these three species is the abundant sticky hair on its stem (Weakley et al. Reference Weakley2024). Globules of viscid exudate are usually visible in close-up photos of this species, particularly when the plant is backlit (Figures 1 and 2). Calles and Schultze-Kraft (Reference Calles and Schultze-Kraft2010: 319) wrote: “Viscid forms of Stylosanthes guianensis and S. scabra are sometimes misidentified as S. viscosa. However, characteristic features of S. viscosa are its particular pod shape and the coiled pod beak … both features are quite constant and permit accurate identification” (see Figure 3). English common names for S. viscosa include: “viscid pencil-flower” (Texas), “sticky stylo” (Australia), and “poor man’s friend” (Jamaica) (Cook et al. Reference Cook, Pengelly, Schultze-Kraft, Taylor, Burkart, Cardoso Arango, González Guzmán, Cox, Jones and Peters2020).

Figure 1. Stylosanthes viscosa flowering in a field at the Indian River Research and Education Center, Fort Pierce, FL (October 21, 2024; JK Wetterer, inaturalist.org/observations/248497924).

Figure 2. Stylosanthes viscosa growing by NW East Torino Parkway, Port St Lucie, FL (December 4, 2024; JK Wetterer, inaturalist.org/observations/254136106).

Figure 3. Stylosanthes viscosa pods from plants growing along SE Westmoreland Boulevard in Jensen Beach, FL (November 15, 2024; JK Wetterer, inaturalist.org/observations/251802405).

Here, I report extensive populations of S. viscosa growing outside cultivation in eastern Florida.

Materials and Methods

While surveying plants in southeastern Florida and posting photos to the iNaturalist website, I encountered a Stylosanthes species in southern St Lucie County, FL, that appeared different from the three species previously reported in the state. I matched my photos with S. viscosa photos from Texas posted to iNaturalist. Alan Franck, collections manager at the University of Florida Herbarium (FLAS), agreed with the identification and sent me information on FLAS voucher specimens of S. viscosa from the Agricultural Research Center, Fort Pierce, FL. Searching the area surrounding my initial observation, I found many more S. viscosa growing nearly in monoculture, in a neighboring part of Jensen Beach in Martin County, FL. I then set about documenting the distribution of this species in Florida.

I went through all Florida observations of Stylosanthes and related Fabaceae species posted to iNaturalist, identifying photos of this species, some of which were misidentified as S. hamata or S. biflora, including three of my own. I searched for S. viscosa, particularly in areas near and between sites where there were earlier observations of this species, photographing the plants and posting the observations to iNaturalist.

Results and Discussion

I documented the first records of S. viscosa growing outside cultivation in Florida. I found S. viscosa growing outside cultivation most easily when it was flowering and growing up to ∼80 cm tall in un-mowed areas next to mowed paths (Figure 4). I also found this species, but with greater difficulty, growing in areas mowed close to the ground (Figure 5). I most commonly observed this species growing in and along paths next to canals and ponds and on mowed roadsides.

Figure 4. Stylosanthes viscosa growing in near monoculture next to a path in Spruce Bluff Preserve, Port St Lucie, FL (June 10, 2023; JK Wetterer, inaturalist.org/observations/166650977).

Figure 5. Stylosanthes viscosa growing in near monoculture in a mowed path in Savannas Preserve State Park, Port St Lucie, FL (November 1, 2024; JK Wetterer, inaturalist.org/observations/250046206).

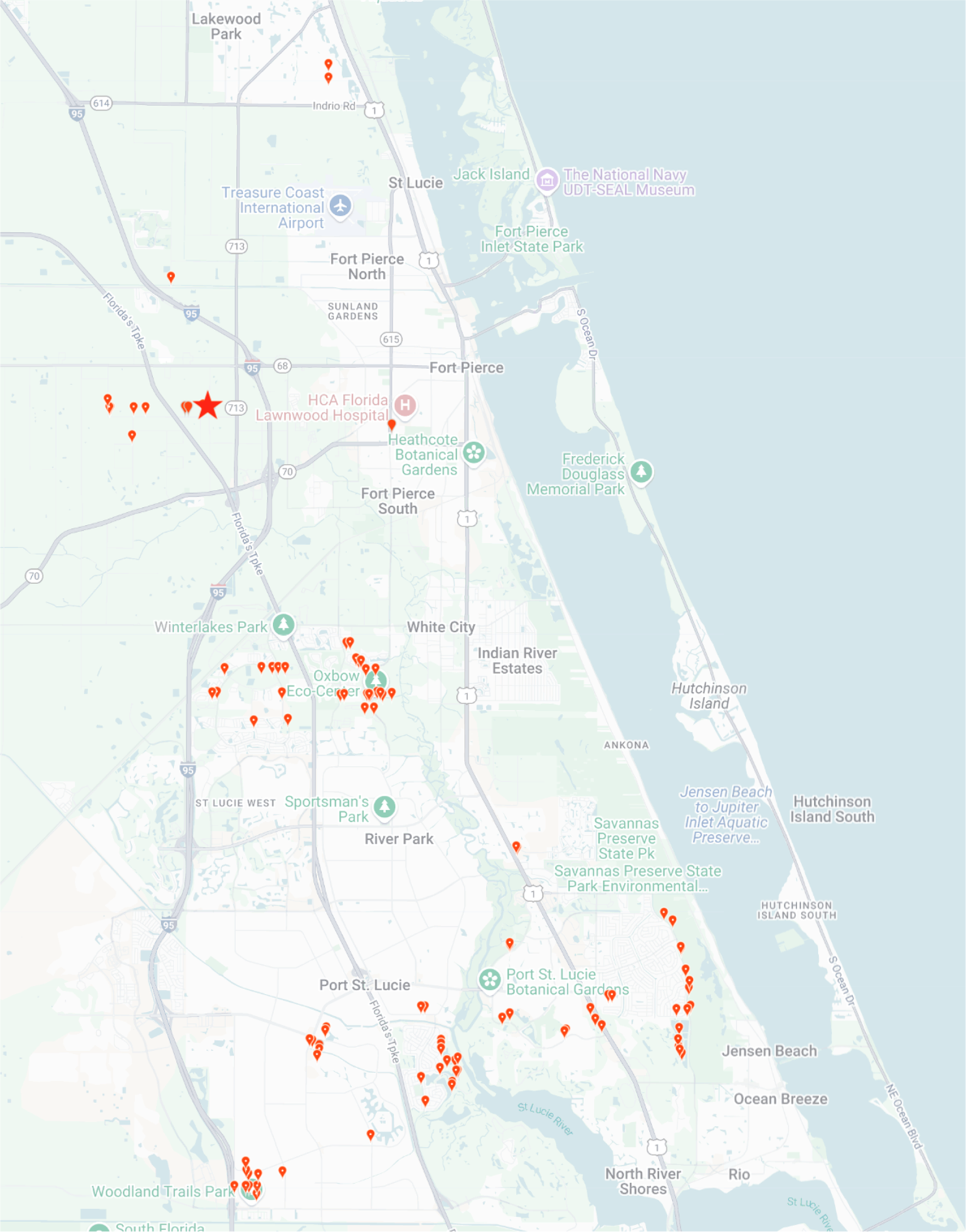

I mapped 266 observations of S. viscosa posted to iNaturalist; 257 by me, plus 9 by others. All observations were from St Lucie County (n = 239) and northernmost Martin County (n = 27) (Figure 6). Six of the nine observations by others (and one by me) were made in one field where this species is growing in near monoculture at the IRREC, near the corner of Picos Road and Rock Road in Fort Pierce (star in Figure 6).

Figure 6. Stylosanthes viscosa observations posted to iNaturalist. Star = Indian River Research and Education Center (formerly Agricultural Research Center–Fort Pierce). Map made using inaturalist.org.

Observations of S. viscosa ranged from the northernmost site in Indrio Savannahs Preserve, Lakewood Park (27.5297°N, 80.3697°W; JK Wetterer, inaturalist.org/observations/262874259) to the southernmost site, 35.4 km away, next to a drainage channel in Woodland Trails Park, Port St Lucie (27.2110°N, 80.3926°W; JK Wetterer, inaturalist.org/observations/250472252). Observations in Martin County were all in Jensen Beach, within 1.5 km of the southeastern border of St Lucie County.

This species is well established in St Lucie County and northernmost Martin County, a range extending from 27.21°N to 27.53°N (Figure 6). This range is at the southernmost edge of a region classified as having humid subtropical climate (Cfa, using the Köppen-Geiger system), although with climate change, this area will soon be classified as tropical (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Zimmermann, McVicar, Vergopolan, Berg and Wood2018). It seems likely that this S. viscosa population descends from plants that escaped from cultivation at the IRREC in Fort Pierce (star in Figure 6). This could potentially be confirmed through DNA analyses comparing vouchered specimens with extant populations. Brolmann (Reference Brolmann1980: 104) wrote: “Experiments at the ARC, Ft. Pierce showed that some accessions of S. viscosa were very persistent. Seed production is usually abundant and many new seedlings are produced each year. Most accessions of S. viscosa are drought tolerant as well as flood tolerant.” Few observations of S. viscosa in Florida come from north of the IRREC (star in Figure 6). This could be, in part, an artifact of less-intensive surveying in these areas. However, it may be that S. viscosa brought to Florida are better adapted to the more tropical climate of the source regions of Ibirarema (22.8°S) and Marilia (22.2°S), both in the state of São Paulo, Brazil (see “Introduction”).

Coelho and Blue (Reference Coelho and Blue1979) and Coelho et al. (Reference Coelho, Mott, Ocumpaugh and Brolmann1981) reported studies of S. viscosa planted in fields at the University of Florida Beef Research Unit (29.744°N, 82.264°W) in Alachua County, 20 km northeast of the main campus of the University of Florida using strains obtained from the Agricultural Research Center in Fort Pierce. Whether this species has escaped cultivation in Alachua County is not known. It may be that S. viscosa populations are unable to persist over winter in the cooler subtropical climate of Alachua County in northern Florida.

Stylosanthes viscosa is able to form dense, almost monotypic stands in southeastern Florida in open areas (see Figures 4 and 5), displacing other plant species, and thus should be considered invasive. The displaced species, however, may often be other invasive, weedy species. Stylosanthes viscosa could also negatively impact arthropod populations. Sutherst et al. (Reference Sutherst, Jones and Schnitzerling1982, Reference Sutherst, Wilson, Reid and Kerr1988) found that the exudate produced by S. viscosa is highly lethal to entrapped cattle ticks (Boophilus microplus). The sticky exudate of S. viscosa probably traps many other types of arthropods as well, functioning as an antiherbivore defense.

If the populations of S. viscosa in Florida descend from plants cultivated in experimental fields in Fort Pierce beginning in 1975 to 1976, then their southward spread has averaged <0.6 km yr−1, and their spread north has been half that. It seems likely that populations of S. viscosa will continue to spread in south Florida, particularly southward into Palm Beach, Broward, and Miami-Dade counties. In part based on my findings, UF/IFAS (2025) has assessed S. viscosa to be “High Invasion Risk” in Florida’s natural areas.

Data availability

All observation data are available on the iNaturalist website: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=21&taxon_id=169425&verifiable=any.

Acknowledgments

I thank A. Franck and M. Wetterer for comments on this article; A. Franck, J. Horn, and other botanists for their taxonomic expertise that have made my plant studies possible; and S. Kim for providing the UF/IFAS assessment.

Funding statement

This research was funded by Wilkes Honors College, Florida Atlantic University.

Competing interests

The author declares no conflicts of interest.