1. Introduction

Failures in complex systems often originate not only from faulty components but also from interactions and hidden dependencies introduced during conceptual design. Prominent examples in automotive and aerospace systems, including unintended acceleration events and tightly coupled control–software interactions, illustrate how indirect coupling across mechanical, electrical and software domains can propagate failures in unpredictable ways. In many cases, these vulnerabilities are embedded early in the system architecture, long before detailed design or validation begins. The complexity can be the root cause for a major costly failure, as in the case of Boeing 737 (Herkert, Borenstein, & Miller Reference Herkert, Borenstein and Miller2020), and the Fukushima disasters (Kuczynski et al. Reference Kuczynski, Wang, Glass and Hoffman2021). Design patterns are effective ways to achieve the intended solution for a single discipline or for simple, multi-disciplinary systems. However, the increasing number of disciplines will increase uncertainty and may make it more challenging to achieve an ideal design. The leading cause might be rooted in the product’s nature and the required functionality. As a result, the design approach, methodology or framework may also unintentionally increase product complexity, as each team tries to improve their design without a complete understanding of others’ (Suh Reference Suh2005). In other words, if any problems occur after production, it might not be easy to identify the design cause. Instead, justifications and alterations might not necessarily offer practical solutions. According to Tomiyama et al. (Reference Tomiyama, Amelio, Urbanic and Maraghy2007), a cause has been identified as the multi-disciplinary complexity of product design.

The authors suggested the need for a new design method in the case of such complex products, based on the existing Vis (Reference Vis2006) Systematic approach. Accordingly, Al-Fedhly & ElMaraghy (Reference Al-Fedhly and ElMaraghy2020) suggested an altered framework to address the increasing complexity of multi-disciplinary product design. The authors approached the multi-discipline as combining more than two diverse specializations, mainly in mechanical, sensory, computer, data and human. However, each discipline may be divided into sub-disciplines within the main category (De, Zhou, & Moessner Reference De, Zhou and Moessner2017). The main challenge may lie in the human factors of stakeholders when the designer is mapping concepts to customer requirements at the early design stage. However, it can be rooted in the design team’s educational and experience backgrounds within each trained discipline team, apart from individual variations.

The conceptual design phase is a crucial step in any product lifecycle. It is so likely because all later steps depend on the conceptual phase. Additionally, the paradigm shift is mainly a change in the concept. For example, the Industrial Revolution began by changing the concept of power through the steam engine. The second revolution began by substituting steam with electrical energy. The third is when computers are utilized in machine control and the fourth is when data technology, including artificial intelligence, is integrated into the product.

Cyber-physical vehicles (CPVs) exemplify this challenge. A single driver input, such as an acceleration command, can trigger tightly inter-connected responses across sensors, controllers, software algorithms, power electronics, communication networks and human–machine interfaces. While each sub-system may be well-designed individually, its combined behaviour can exhibit cascading failure risks that are difficult to anticipate with existing conceptual design tools.

Current design methodologies offer valuable support for system representation, modularization and dependency analysis; however, they exhibit notable limitations at the conceptual stage. Established coupling and complexity metrics, such as the coupling index, cluster independence and inter-dependence degree, primarily assess structural connectivity or change propagation and typically require mature architectural or historical change data. As a result, they provide limited insight into indirect multi-component coupling and risk-weighted dependency behaviour during early design, when architectural decisions have the most significant leverage.

1.1. Aim and significance

The primary contribution of this research is methodological: it provides a structured, transparent and reproducible approach for revealing hidden coupling, assessing architectural vulnerability and supporting informed design decisions before detailed system definition. The framework is demonstrated through a CPV acceleration module case study, illustrating how abstraction-based modelling and ICX analysis can be used to reduce complexity and mitigate cascading failure risks at the source.

This study confirmed that while current methods can represent system structure or functional behaviour, none simultaneously support:

-

1. unified representation of multi-disciplinary components,

-

2. early detection of indirect (multi-component) coupling, and

-

3. quantitative assessment of dependency strength.

This article addresses this gap by proposing a conceptual design framework for managing multi-disciplinary complexity in CPVs and similar cyber-physical systems. Grounded in design research methodology (DRM), the framework integrates two complementary methods: the abstractional design method (ADM) for unified early-stage system representation and the inter-coupling index (ICX). This novel reliability-aware coupling metric quantifies both direct and indirect dependencies during conceptual design. The significance of the study lies in addressing a critical gap in the early-stage design of complex systems, where multi-disciplinary integration often leads to unmanaged complexity, hidden inter-dependencies and increased risk of failure. The proposed methodology provides a novel and practical approach to simplifying conceptual system modelling and quantitatively evaluating functional coupling. This contribution is substantial in enabling design teams to identify indirect dependencies, prevent cascading failures and rationally compare alternative system architectures. The proposed methodology promotes clarity, modularity and collaboration across disciplines, supporting more robust and resilient cyber-physical system (CPS) designs – an increasingly important priority in automotive, aerospace and intelligent manufacturing industries.

2. Literature review

Sawyer et al. (Reference Sawyer2025) proposed a framework that integrates standard design practice with existing methods to systematically guide designers through the product’s problem definition and conceptual design stages. The framework emphasizes identifying external factors influencing mode selection, defining functional requirements for each mode and iteratively developing conceptual forms inter-connected through transformation methods. While this framework is an essential step towards systematically addressing the physical and functional complexities of multi-mode products, it has certain limitations when evaluated against the needs of multi-disciplinary products. First, the scope remains confined mainly to mechanical transformations in consumer products, with limited consideration for integrating embedded intelligence, sensing or control systems that characterize modern CPSs. The transformation methods described are structural and passive, and do not address active control, adaptive behaviour or real-time feedback, which are increasingly critical in intelligent vehicle systems.

Second, while the framework offers a structured approach to early design stages, its emphasis remains primarily on problem definition and conceptual ideation, with less focus on the multi-disciplinary integration required for complex CPS products. In contrast, the development of multi-disciplinary systems demands convergence across mechanical design, electronics, software, human–machine interfaces and system-level improvements – dimensions that extend beyond the proposed framework’s boundaries.

Finally, the demonstration of the framework on children’s furniture, though illustrative, may limit its generalizability to highly dynamic and safety-critical domains such as automotive or complex systems. This study builds on the foundational concepts of structurally transforming multi-mode design to address these gaps. Still, it extends the scope into multi-disciplinary conceptual product design within the context of cyber-physical vehicles. The proposed approach emphasizes the holistic integration of physical structures with computational intelligence, adaptive functionality and human-factors considerations, aiming to address the unique challenges posed by complex products.

The cyber-physical vehicle (CPV) is attracting growing attention from both research and industry. Bradley & Atkins (Reference Bradley and Atkins2015) carried out a survey focusing mainly on design optimization and feedback-driven regulation of embedded CPV. The authors concluded that the main challenge of CPV design is addressing all disciplines of conceptual architecture. Even though much research focuses on energy consumption, given that batteries are the primary power source, it is vital to increase single-charge mileage and reduce the final product’s cost. A high trend is the increased use of cyber technology to improve safety and increase reliability. Nevertheless, the trend towards increased electronic and data use may result in higher power consumption, greater data processing and increased storage demand, as well as introduce more system failure points. However, Bradley & Atkins (Reference Bradley and Atkins2015) suggest that addressing the problem in the design phase can be achieved by introducing a uniform design method that accommodates functionality and variables. Furthermore, human factors are a significant subject within the CPV, as the machine interacts with multiple types of operators. Instead, it has to interact with multiple users, passengers and other humans while driving, as well as with other vehicles, pedestrians and cyclists. Darwish & Hassanien (Reference Darwish and Hassanien2018) identified the challenges of cyber-physical systems as:

-

• System consistency. The authors acknowledged that the main challenge may be rooted in the design phase. They also noted the challenges of a possible linkage between components and the need to mitigate their adverse effects.

-

• System reliability. The principal highly depends on CPS for connectivity, computer functionality and time.

-

• Dependability. According to the authors, this issue needs to be addressed at the design level, where the system can tolerate some undesirable inputs, such as feedback or delay disturbance.

-

• Security. Security should be designed to deal with both attacks and natural disasters.

-

• Internal attacks. The system needs to be designed to be intelligent enough to detect false data and statistics.

-

• Simulation tool. It is essential to test and update CPV before further development.

-

• Embedded system issue. A new component is required to enable the cyber system to read the product’s current status.

Hence, it is understood that a design methodology framework might address some of these challenges. In contrast, a design method might address other challenges within unavoidable constraints, such as technological availability and economic factors. Also, a successful vehicle design might need to satisfy multiple disciplinary objectives, including potential constraints (Kodiyalam & Sobieszczanski-Sobieski Reference Kodiyalam and Sobieszczanski-Sobieski2001).

2.1. Technical collaboration

It is the technical team’s ability to communicate and collaborate to achieve a task, objective or goal effectively. It is believed that collaboration is a crucial element of concurrent engineering for solving multi-disciplinary design issues. Chen & Lewis (Reference Chen and Lewis1998) proposed the use of the decision support problem (DSP) in two decision-making levels to increase the design variation flexibility of an inter-dependent system. The main objective is to increase design robustness by minimizing tradeoff issues. However, it is believed that this methodology is to improve an agreed design towards more reliable performance after an agreed concept. According to D’Amelio (Reference D’Amelio2010), one of the main challenges of multi-disciplinary design can be the lack of a common communication framework among parties from different disciplines. As a result, design failure may not be identified using the established measures; for example, an issue is beyond the reach of a single expert because it falls within a gap between two or more disciplines. Hence, the authors strongly agree that behaviour might be unpredictable in some cases due to undefined cross-disciplinary relations. Henceforth, it can be concluded that multi-disciplinary challenges are related to multiple connected domains, whether the link is physical or virtual. To address these challenges, D’Amelio, Chmarra, & Tomiyama (Reference D’Amelio, Chmarra and Tomiyama2011) identified a multi-disciplinary linkage problem. Accordingly, the authors introduced the design interface detector (DID) software based on qualitative reasoning, the physical feature reasoning system (PFRS), to predict as many linkages as possible between components. However, it is agreed that it might not be an efficient way to scan all solutions provided by the software. So, the authors improved their method to include two filters that can discriminate ‘negligible’ solutions and identify the only potential cross-disciplinary linkage. This is especially important for addressing issues arising from the design, functionality and coupling of two or more components, as each component may function perfectly on its own. For example, the heat generated by one component can affect the functionality of another component linked to it. Also, it has been indicated by Tomiyama et al. (Reference Tomiyama, Amelio, Urbanic and Maraghy2007) that the cause of system failure may result from one of the other systems’ inter-connected components.

Luo (Reference Luo2017) proposed the use of the ‘System-of-Systems’ methodology to overcome complexity challenges at the conceptual design level. The methodology can mainly be used to map a product’s components into a uniform system representation across multiple systems. The author based the outcome on literature research on system definition, characteristics and management approaches. It is agreed that the majority of research in this area remains at the stage of theory development. Furthermore, it is agreed that adapting such a method or methodology can serve in the new product component compatibility issue. By adapting the author’s example, the use of complexity reduction tools, such as the system-of-systems approach, to conceptualize a CPV can result not only in improved vehicle design but also in improved roads, communication technology and data technology. In the system-of-systems approach, the main characteristic of each module, or of a component to be identified as a module, is that it should function as an independent unit. At the same time, the system is not entirely functional if a single module is removed. Furthermore, the system can serve as a module within another synthesis system. It is believed that the main idea is to define systems into the main module and then divide them into sub-modules based on the macro network map concept or hierarchy structure. As suggested by Luo (Reference Luo2017), the main challenges of this approach may include:

-

• It requires a high level of standardization whenever possible to provide a common interface between each system.

-

• It requires central coordination.

-

• The behaviour of systems is not easy to predict despite their high modularity.

-

• The newly generated system of systems may not guarantee a value-added process or even a product.

Often, the currency equivalent value is used in system assessments, especially in design optimization. According to the European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (2021), the current assessment methods of currency equivalency cannot provide an accurate measure of device assessment. A significant drawback of such practice is the omission or misvaluation of sustainability, resilience and social aspects. Especially in addressing the need for an alternative assessment approach to currency equivalency, given that the currency is a domestic relative. For example, the Canadian dollar might be used to evaluate a system’s performance in Canada. In contrast, the Euro can be used to evaluate a system in a European country that may not project accurate evaluations. Primarily, currency values fluctuate over time, which means performance may vary from one calculation time to another, as currency values differ. Furthermore, regional price variation may affect the same system’s performance due to different evaluation zones. So, this study may propose an alternative approach to evaluating the system’s complexity without converting variables into currency equivalents. In addition, it may address the need for a unified design method as a basis for communication among designers.

2.2. Design knowledge

It is understood that knowledge is an important aspect of engineering design. According to ElMaraghy (Reference ElMaraghy2009), knowledge may be defined as ‘information combined with experience, context, interpretation, and reflection’. It is believed that knowledge can have a significant impact at the early stage of design, while the concept is being developed. Although a human can use knowledge to solve an existing problem efficiently, it can be used more effectively at the level of innovation or invention. Therefore, it is believed that any revolutionary development may start with a change in a concept driven by knowledge evolution. For example, a CPV might be considered a conceptual shift of the existing vehicle innovation. However, the current challenge tradeoff may lie in the multi-disciplinary nature of such a product in general. Furthermore, multi-disciplinarity might be blamed as a root cause of problems, including behavioural and functional failures, that might not have existed when products were simple in design and architecture. According to Tomiyama et al. (Reference Tomiyama, Amelio, Urbanic and Maraghy2007), multi-disciplinarity can increase all types of complexity during product and process development as well. However, it is agreed that the multi-disciplinary complexity can result from design knowledge, which differs from other types of complexity, including computational and uncertainty types.

2.3. Design structure matrix (DSM) method

This section is mainly based on Eppinger & Browning (Reference Eppinger and Browning2012) book, as it contains many relevant empirical cases of DSM application in well-known complex products and organizations. One common DSM use in product design is managing the complexity of multi-disciplinary components. It can serve as a tool for determining and classifying component linkages. DSM is a handy tool because it projects the system’s architecture in a compact, easy-to-comprehend manner. The simplicity of this tool makes it easy to scale and perform some basic calculations. It can represent systems at varying levels of detail or decomposition. It has been used to varying degrees and with different link values to indicate connection strength, active or passive status, impact size and multiple dimensions.

Ford motor company had one of the earliest known DSMs in product design in 1994. Steven Eppinger and Thomas Pimmler developed a DSM to understand better the climate control network in terms of spatial adjacency, energy dynamics, material dynamics and status signal flow between elements. However, the designers neglected the heating system as part of the climate control, which might have led to different variants. Additionally, the combination or correlation among the main metrics was not part of this analysis, which could yield an additional matrix.

Crag Rowles carried out the project while he was a MIT system design student and an employee of Pratt and Whitney to examine the integration of the PW4098 jet engine into the system. He interviewed all subject engineers to develop a model of 8 main sub-systems and 54 principal components. The researcher used a binary value to determine the links among spatial adjacency, energy dynamics, material flow, physical connectivity and data flow. Two main components are identified as highly connected despite their spatial separation – mechanical components and externals.

According to Tim Brady and Deborah Nightingale, the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) investigated the effectiveness of DSM as a functional system architecture visual tool and its viability to reflect the system’s technology maturity and risk assessment. They used failed missions as validation cases. A technology risk factor (TRF) is a variable that can be added to each system component in the original DSM. The resulting matrix is named technology risk DSM (TR-DSM). The dependency variable was generated by summing four interface values: physical, energy and information flow (Eppinger & Browning Reference Eppinger and Browning2012, chap. 3).

A network node-link organizational architecture representation can be mapped into a DSM. It has been used since 1972, even before the common name was used. The primary purpose was to visualize the nodes and associated links. The connection links may refer to interaction frequency, location, meetings, administrative communications, information flow control and outcome expectation (Eppinger & Browning Reference Eppinger and Browning2012, chap. 4).

According to Tyson Browning, a cross-functional engineering team was formed to compare two situations: the A–D and the later redesigned Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet, which McDonnell Douglas had initially built. The primary purpose of the DSM was to identify changes in interactions between departments and in organizational evolution. It used the unit-total communication intensity, along with the average. A notable finding is that the DSM can justify the organizational structure in terms of the interaction rate of recurrence (Eppinger & Browning Reference Eppinger and Browning2012, chap. 5).

Boeing had developed a DSM to evaluate the effect of its product design architecture process on risk, cost and delivery time disciplines. One of the findings is that rearranging the matrix components can improve clustering activity, potentially negatively impacting other measures like cost or delivery time (Eppinger & Browning Reference Eppinger and Browning2012, chap. 7).

According to Carlos Gorbea, a DSM was used to investigate the relationship between functions and components in multiple variants of a BMW hybrid vehicle. An asymmetric, non-directional, unweighted connection is used to represent both cross-component and functional links. The DSM was built based on a conceptual draft of a powertrain architecture. The relationship between components is considered in terms of physical connection and energy flow, including mechanical, electrical, thermal and chemical. A delta DSM can indicate a difference between two design structures or two varied component linkages of two alternatives of the same architecture with the same functional and componential contents. One of the delta DSM’s identified benefits is determining which function or component can be manipulated through different variants. A summation DSM can also expose critical links, mostly unchanged in all variants (Eppinger & Browning Reference Eppinger and Browning2012, chap. 9).

Hence, DSM is a powerful tool for identifying direct coupling between components, blocks or any pair of entities in any system. This is very useful in complex engineering systems with inter-connected components in various domains. As such, many types of coupling can be uncertain during design and undocumented due to knowledge or complexity. DSMs can be combined to produce new information about two systems or the same system in different organizations. It can also measure the link strength between components for different system indications. In some cases, basic algebraic calculations can be performed on the matrix contents to identify key components, such as critical elements.

However, there is no standard framework that multi-disciplinary systems follow to quantify DSM utilization.

2.4. Model-based systems ontology

An ontology of a system is a result of connected concepts. Objects and functional connections can describe or define a system’s ontology. This section will review two conceptual modelling languages, object process methodology (OPM) and systems modelling language (SysML). Object process methodology (OPM), founded by Dov Dori, is a process-based ontology representing a system’s contents from behavioural or functional aspects (Dori Reference Dori2015). In OPM, a process is an ultimate thing that can be generalized, just like a functional override in object-oriented programming (International Organization for Standardization 2015). It is a powerful design method and methodology that uses abstraction principles to represent systems and products at varying levels of detail, tailored to the required design level. The OPM defines the system’s components to describe any system in a standard structure and language.

SysML is an object-based object management group (OMG) standard system design language. It uses the same object-oriented approach to represent systems. SysML is a subset of UML 2.5 with extensions to address additional system requirements in an engineering context (OMG 2018).

3. Research methodology

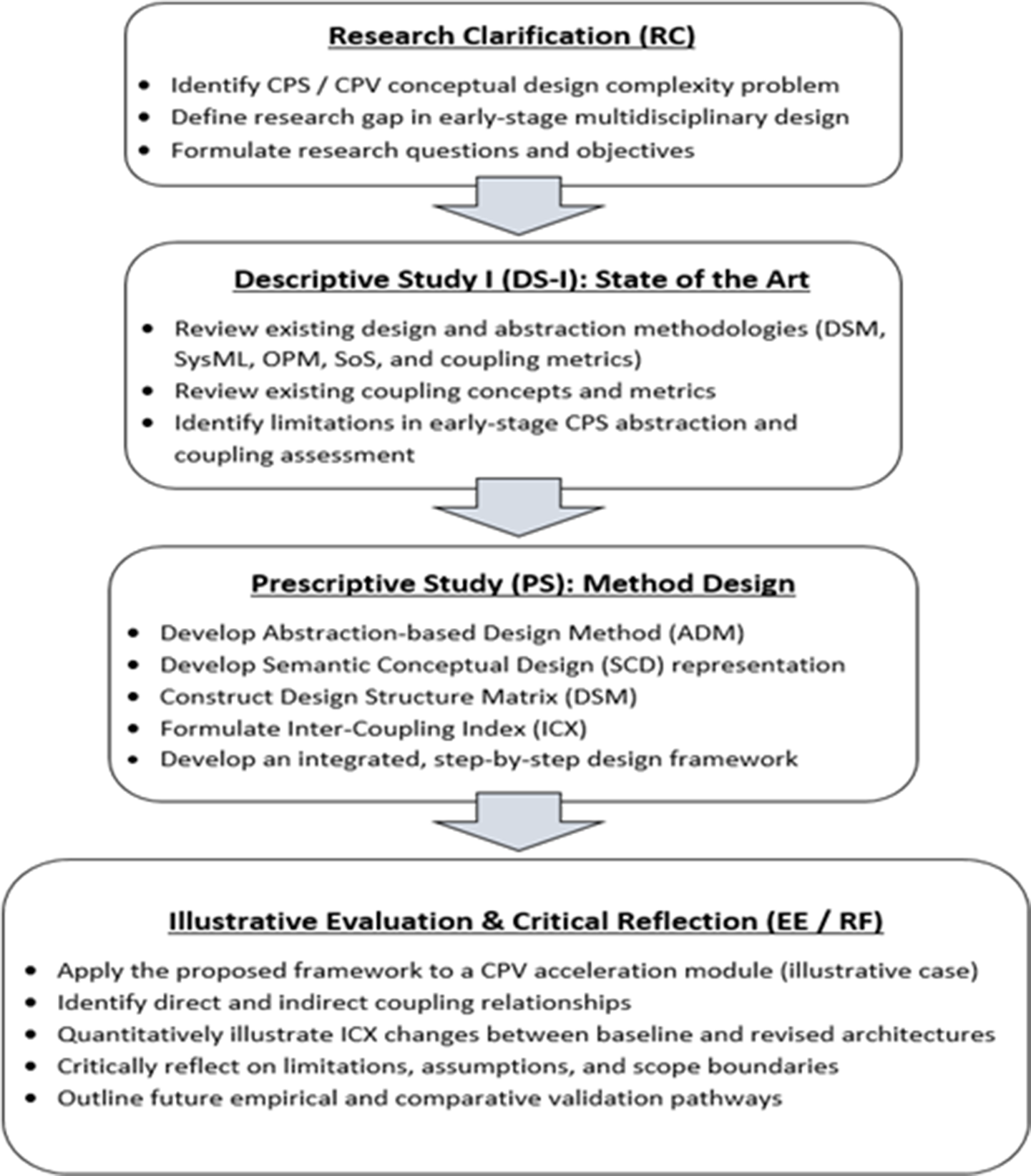

This research follows a structured design research methodology (DRM) (Blessing & Chakrabarti Reference Blessing and Chakrabarti2009). It draws on principles from the DRM to ensure methodological transparency, reproducibility and rigorous knowledge generation. Within the DRM, the case study serves as an illustrative evaluation to demonstrate feasibility and plausibility of the proposed method rather than a full empirical validation. The methodology consists of four inter-connected phases: (1) research clarification, (2) descriptive study I, (3) prescriptive study and (4) illustrative evaluation and critical reflection. Figure 1 illustrates the overall research methodology.

Figure 1. Research methodology based on design (DRM).

3.1. Research clarification (RC)

The research begins by identifying the core problem: increasing multi-disciplinary complexity in conceptual design. Prior literature highlights challenges such as hidden functional inter-dependencies, inadequate early-stage modelling, difficulty in cross-disciplinary communication and the inability to detect indirect component coupling. These challenges often result in unpredictable system behaviour, cascading failures and inefficient collaboration among design teams.

From this analysis, three research questions were formulated:

Q1: How can conceptual design complexity in multi-disciplinary CPV systems be more effectively represented and managed at the early design stage?

Q2: How can model-based exhibiting enhance communication and reduce ambiguity across design disciplines?

Q3: How can indirect component coupling be quantified to reveal hidden dependencies and potential cascading failure risks?

The corresponding research objectives are:

-

1. To develop a unified conceptual design framework integrating abstractional design (ADM) with a new inter-coupling index (ICX).

-

2. To establish an abstraction-based modelling approach that supports cross-disciplinary communication while minimizing cognitive load.

-

3. To introduce a quantitative metric capable of assessing direct and indirect coupling in multi-disciplinary systems, ICX.

-

4. To apply and evaluate the proposed framework through a complex case of a cyber-physical vehicle (CPV).

3.2. Descriptive study I (DS-I): understanding the problem and existing approaches

In this phase, the existing state of knowledge was analysed through a structured review of relevant design methodologies, including:

-

• Design structure matrix (DSM).

-

• Object-process methodology (OPM).

-

• Systems modelling language (SysML).

-

• System-of-systems modelling.

-

• Multi-disciplinary optimization and reliability modelling.

-

• Qualitative physics–based interference detection methods.

-

• Existing conceptual design frameworks for CPS and CPVs.

3.3. Prescriptive study (PS): development of the new design method

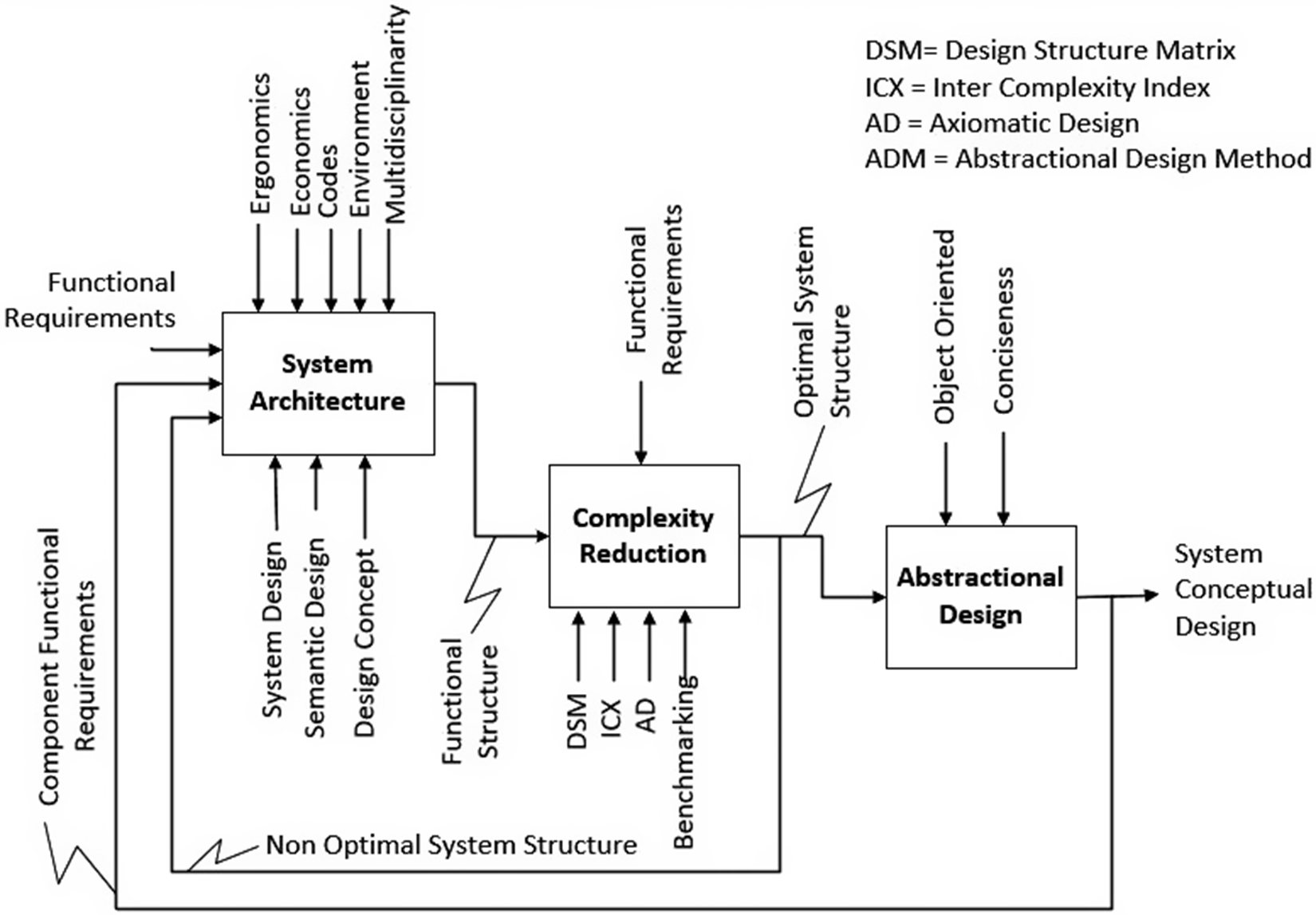

This section will demonstrate how the proposed methodology can synthesize an improved product design. The suggested design methodology combines a model-based approach, AD, DSM, ADM, a network analysis and an ICX complexity measure, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. IDEF0 conceptual design framework for multi-disciplinary products showing the integration of abstraction, DSM and ICX for complexity reduction.

This approach can be applied to various multi-disciplinary systems, including complex engineering and cyber-physical systems. The methodology is intended to ensure that the system has a relatively low functional complexity and high robustness, and is based on sound principles of system design and improved methods. The abstractional design method (ADM) is a part of this methodology that provides a uniform model for systems and components by treating them as objects, thereby simplifying the overall understanding of the system.

3.3.1. Abstractional design method (ADM)

Abstraction is a known method in software design and development. According to Kramer (Reference Kramer2007), it is the process of simplifying the details of an object to reduce its complexity. In object-oriented software, it is the level of detail that carries only the necessary information. By treating a thing as an object in software, this approach can provide a uniform representation for components. Hence, by applying the same principle to any system of systems methodology, abstraction can be a valuable tool for including enough detail about components to show each system component’s basic functionality and attributes. Also, it may reduce the system’s complexity by eliminating excess information, thereby providing a brief understanding of the system through its components’ abstracts. Accordingly, each element in a system can be described in an arrangement of name, functions and attributes. This unifying description can provide a common platform for different associated parties. It can simplify understanding by providing a single standard communication format among various parties.

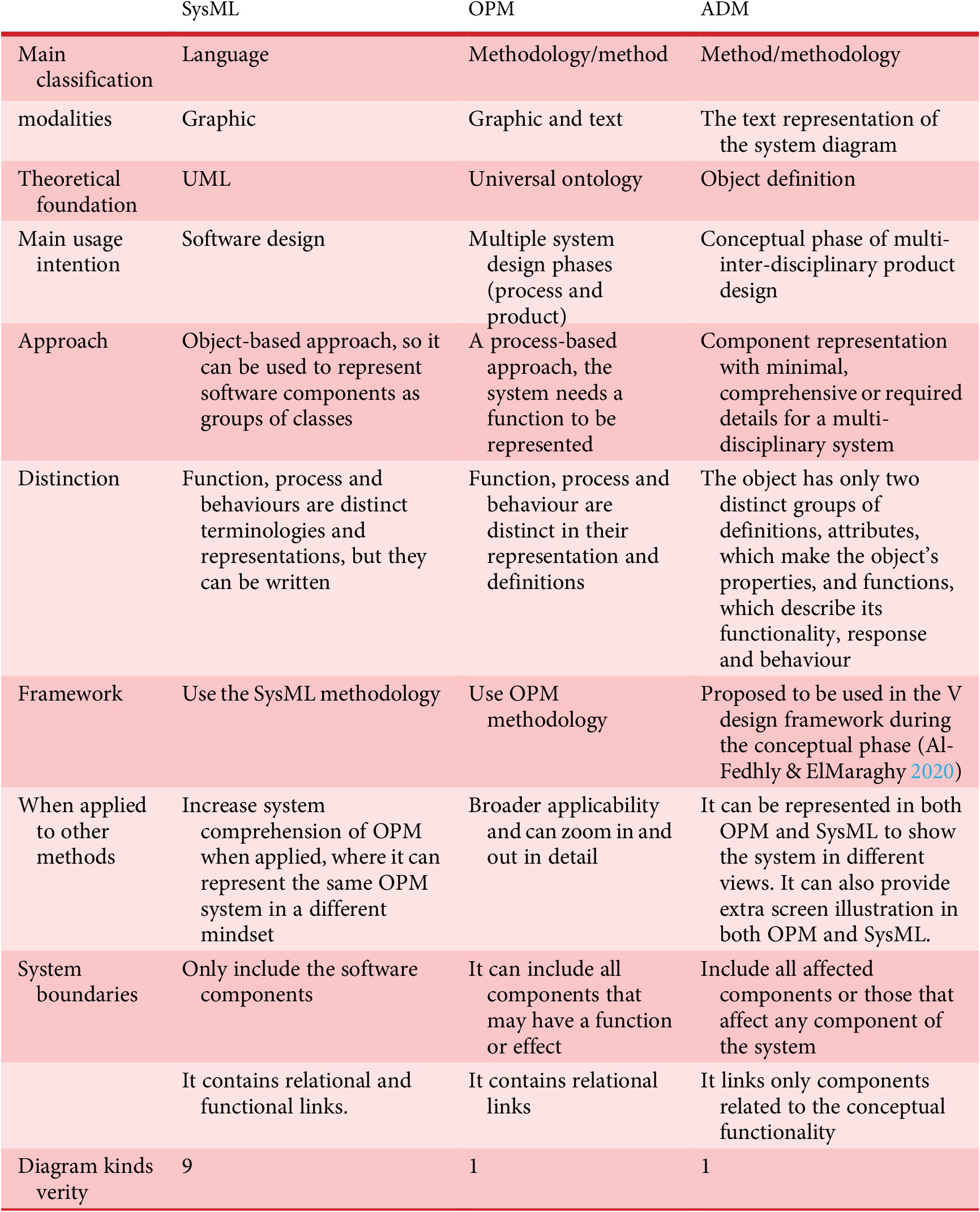

3.3.2. OPM, SysML and ADM compression

This section compares the two primary system design methodologies with ADM. ADM uses an object definition that is closer to object-oriented programming, allowing it to represent the entire system. That said, a process cannot be created without an existing object that is defined to perform a function initiated by that object. Additionally, the function can be used as an interface between objects to pass information, instructions or to change the status of the current object or other objects. Additionally, in ADM, status is an object attribute; no separate annotation is required. So, if it is a required attribute, it can be part of an object just like other attributes, for example, surface finish, colour, strength.

Also, in OPM, the relationship between process and object can take different types to indicate. However, ADM connects objects directly to demonstrate a link without specifying the relationship type. As a process-based method, OPM may start with the primary process, then add objects. ADM starts with only objects, then connects them via functions and attributes that can be added.

The OPM represents the system based on an event in which time is critical for building and understanding the system. The ADM requires only basic information sufficient to construct a distinctive system in terms of components and functionality, without extensive detail.

ADM can be the simplest form of SysML or UML, in which an object is defined abstractly in terms of attributes and functionality. So, a better understanding of the system can be developed earlier in the design phase. However, ADM does not define connection type, other variables or entities as SysML requires. Instead, ADM provides an extra system view within the conceptual design phase.

OPM integrates objects (systems/components) and processes (operations/functions) in unified diagrams, providing a holistic view of systems’ behaviour. It is a powerful representation of early-stage complex systems design (Dori Reference Dori2015). Table 1 concludes a comparison between OPM and SysML based, in addition to ADM.

Table 1. Comparison between OPM and SysML with ADM based on (Dori Reference Dori2015).

3.3.3. Inter-coupling index

The inter-coupling index (ICX) is a quantitative measure that captures the degree of interaction and dependency among system components or sub-systems across the different phases of the design process. It reflects the complexity introduced by inter-dependencies, enabling designers to benchmark, assess and manage coupling in multi-disciplinary design environments.

According to the International Organization for Standardization (2017), in a multi-disciplinary system, coupling is the ‘manner and degree of inter-dependence between modules (components)’. Although the carrier’s total connections are close to the battery and sensors, both may have different failure rates, depending on their composition, based on EV risk assessment values (Tang et al. Reference Tang, Shu, Zhu, Wang and Yang2021). As a result, reliability might be measured as a degree of total inter-dependency and vulnerability, and the reliability of a component might be defined in terms of failure rate. Therefore, a failure analysis, for example, FMEA or a failure tree, can be conducted at this level to obtain the failure rate, which can be used as a dependency factor.

So, the following formula:

where ICX is the inter-coupling index of a system, component or multiple linked systems or components. L is the total number of functional links in and out of the component. f is the failure rate of the component.

Then

where the literature considers only direct coupling, indirect coupling can introduce additional complexity due to multiple dependencies. The case study will demonstrate indirect coupling.

As discussed earlier, multi-disciplinary complexity arises from integrating multiple components within the same functional domain to perform the desired action and contribute to the required function. However, using DSM or any matrix tool makes direct coupling easy to detect. Unlikely, indirect coupling can group multiple components in a loop dependency. Hence, a failure in one component may trigger failures across inter-coupled components, leading to a domino effect. Such an effect is not found in the related literature so that it will be demonstrated in the showcase illustration. Non-loop, or open-loop, coupling can be as effective as looped coupling, but it may result in redundant calculations due to a single dependency that has already been considered. Equation 3 shows the calculation of multiple-component coupling, which can be used to calculate indirect coupling.

Although several established metrics exist for quantifying coupling in product and system architectures, such as the coupling index (Martin & Ishii Reference Martin and Ishii2002, cluster independence/module coupling independence (Newcomb, Bras, & Rosen Reference Newcomb, Bras and Rosen1998 and inter-dependence degree (Eckert, Clarkson, & Zanker Reference Eckert, Clarkson and Zanker2004), these measures primarily evaluate structural or change-based dependencies and do not explicitly incorporate component reliability, failure likelihood or indirect multi-component propagation effects in early conceptual design. To clarify the unique contribution of the inter-coupling index (ICX), a critical comparison is provided next.

3.3.4. Coupling index (Martin & Ishii Reference Martin and Ishii2002)

The coupling index quantifies design modularity by measuring the number and strength of inter-connections relative to component interactions. It is highly effective for structural design decisions and for predicting change propagation. However, it is based on design change sensitivity rather than the functional vulnerability or reliability of interacting components.

Thus, it does not address how the likelihood of failure interacts with dependency strength, nor does it quantify cascading effects in multi-disciplinary CPS contexts where software, electrical and mechanical domains interact with different hazard profiles. The ICX incorporates failure rate (f) as a parameter directly tied to system reliability, enabling evaluation of the risk-weighted effect of coupling during the conceptual stage – before geometric or change-based analyses are possible.

3.3.5. Cluster independence and module coupling independence (Newcomb et al. Reference Newcomb, Bras and Rosen1998)

These clustering metrics support modularity optimization by evaluating how well components can be grouped into independent modules. They are powerful for configuration design but assume:

-

• a stable component decomposition,

-

• architecture-level clustering logic and

-

• that dependencies are primarily structural or functional.

They do not incorporate reliability or vulnerability factors, nor do they provide a mechanism for quantifying indirect coupling loops spanning disciplines. The proposed ICX handles direct and indirect coupling, capturing multi-component dependency loops.

3.3.6. Inter-dependence degree (Eckert et al. Reference Eckert, Clarkson and Zanker2004)

The metric evaluates the density and relative strength of relationships in a system architecture, focusing on the structural connectivity of functions or components. While it quantitatively expresses dependency, it does not differentiate components based on failure likelihood or operational hazard. The proposed ICX links component reliability to component dependencies, producing a measure that reflects not only how much components depend on each other, but also the riskiness of each dependency.

Cyber-physical vehicles exhibit multi-disciplinary interactions in which mechanical components (e.g. pedals, carrier), electrical and electronic hardware (battery, motor, sensors) and software and data modules (control algorithms, cloud services) exhibit different failure behaviours and propagation characteristics. Traditional coupling metrics treat all dependencies as structurally equivalent. ICX instead captures how a component’s intrinsic vulnerability amplifies its influence within a coupled network. Specifically:

-

• Failure rates are grounded in reliability engineering and widely used in CPS hazard analysis.

-

• They provide a quantitative reflection of risk during operation, not merely during design change.

-

• They enable early detection of components that cause cascading faults due to high-risk coupling.

-

• They are available even when geometric or detailed parametric models are not, making them suitable for conceptual design.

However, ICX is not intended to replace existing structural or change-based indices, but it can serve as a complementary or extending metric in the domain of early-stage reliability-aware multi-disciplinary design.

4. Case study (evaluation): cyber-physical vehicle conceptual design

Adapting the integration method, the cyber-physical vehicle (CPV) is used to represent the next-generation mobility system, integrating mechanical, electrical and digital components into a unified intelligent product platform. At the conceptual design stage, multiple design variants can be generated to explore different configurations and technologies. The goal is to manage product complexity early while maintaining flexibility in exploring alternatives.

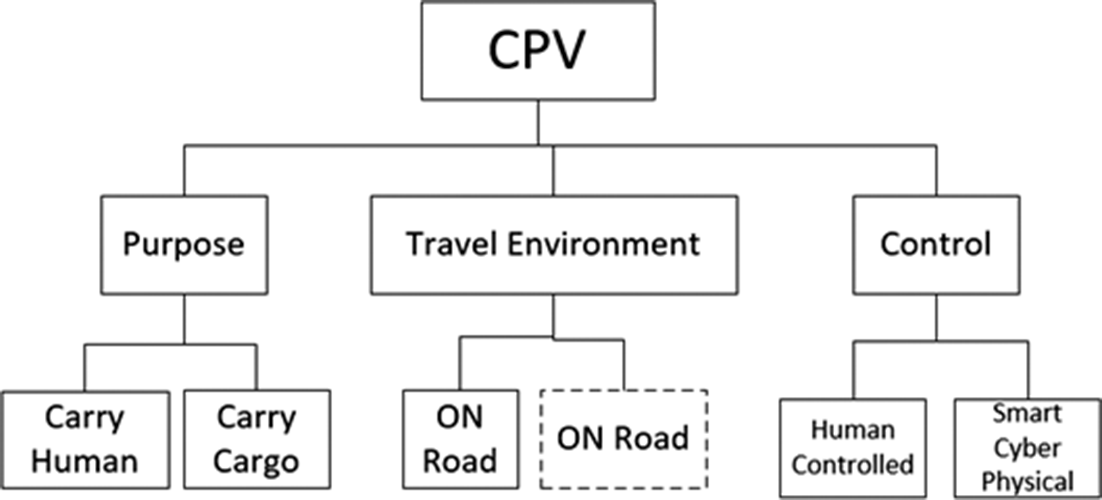

After identifying the main functional requirements of a cyber-physical mobility system – such as propulsion, control, energy storage and driver interaction – a simplified conceptual design is developed to demonstrate the proposed framework. These functions can be decomposed into sub-functions using a system-of-systems approach, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Hierarchical decomposition of functional requirements for a cyber-physical vehicle (CPV) at the conceptual design stage.

This hierarchical structure shows how simple a complex system can be represented with minimal details during early design. Each function can evolve into several conceptual solutions, depending on available technologies, design tools and resource constraints. The technology may refer to digital design tools (e.g. simulation software), production technology (e.g. automated assembly) or product-embedded technology (e.g. sensors, processors).

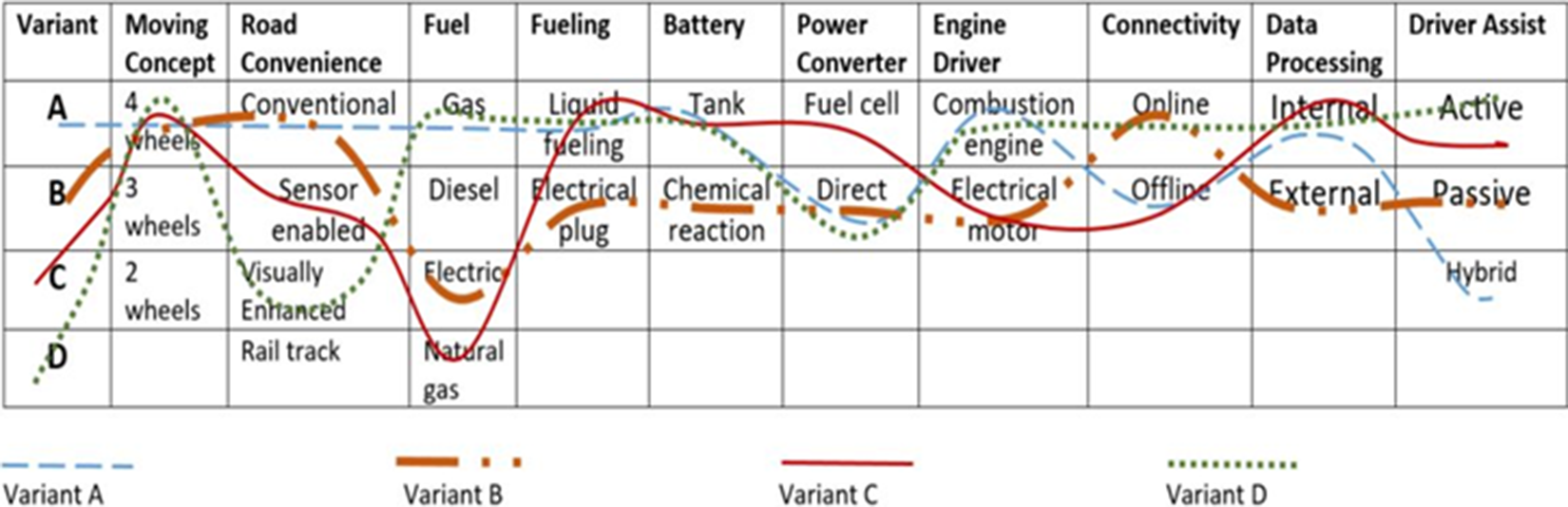

4.1. Concept generation using morphographic analysis

A morphographic table (Figure 4) is used to explore combinations of design options, producing multiple CPV variants. While many combinations are possible, three representative variants were selected to demonstrate the process and avoid redundancy.

Figure 4. Morphographic table to develop design concepts.

Each column in the table corresponds to a functional attribute, such as propulsion type, energy source, connectivity mode or driver assistance level. For example,

-

Mobility concept: Ranges from traditional wheel-based designs to novel rail or guided systems, influenced by human factors and market trends.

-

Road convenience: Example of an external factor that affects even the system’s concept. For this case, a conventional road, a sensor-enabled, graphically marked road or a railroad alternative has been used.

-

Fuel type, fuelling, battery and power converter: The commonly used fuel types have been included in the ‘fuel’ column. The ‘fuelling’, battery and ‘power converter’ depend on the fuel type, available technology, constraints and design preferences.

-

Engine driver: The power generator to drive the vehicle.

-

Connectivity and data processing: Online (real-time data transfer) or offline (data stored and processed within the vehicle), depending on available convenience and safety constraints.

-

Driver assistance: Active means the system can take over vehicle control from the driver to perform safety actions, such as braking or lane-changing. In contrast, passive means the vehicle provides warnings to the driver about the situation and lets the driver decide on an action. A hybrid may make its way between some active and passive features, but it cannot be either one at the same time.

For this study, Variant B was selected as the baseline design. It features four wheels operating on conventional roads, powered by an electric motor with plug-in charging, internal data processing, active connectivity and passive driver assistance. This variant represents a balanced design between feasibility and cyber-physical functionality.

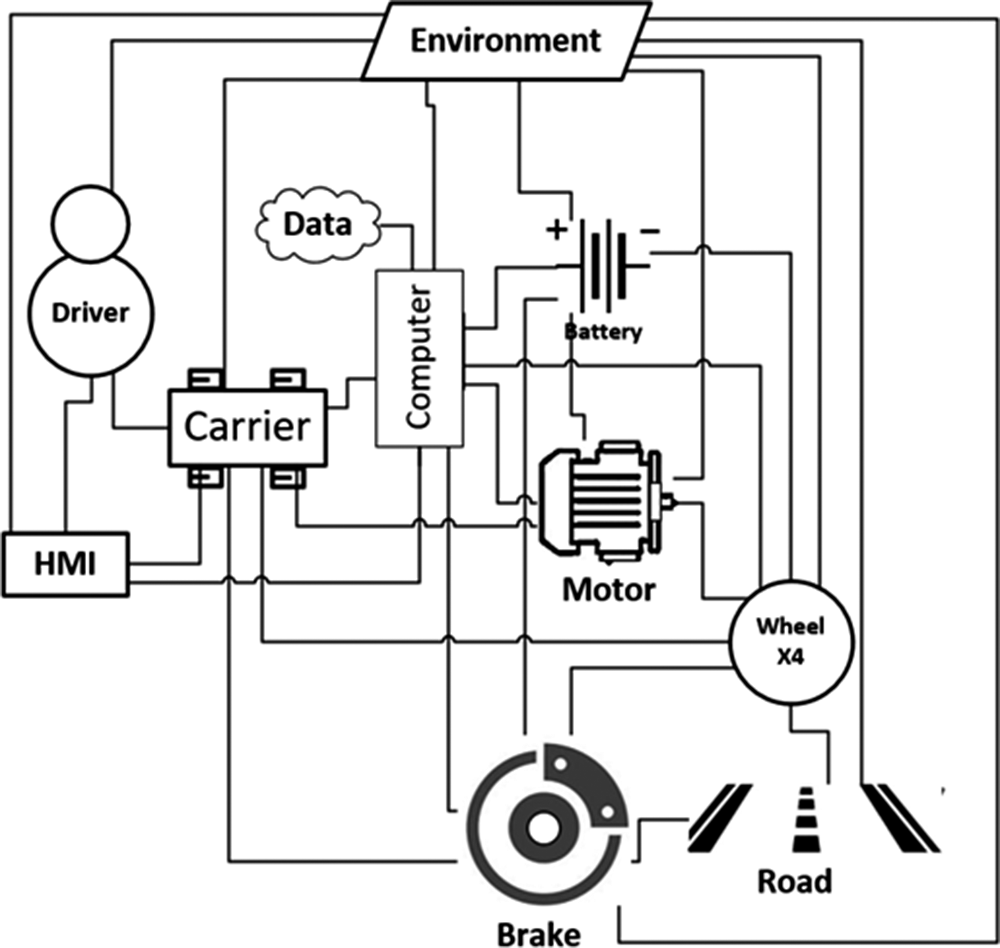

To explore its internal structure, a semantic conceptual design (SCD) network diagram was developed (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Semantic conceptual design network of the selected CPV variant, showing functional dependencies among core sub-systems.

The SCD identifies core sub-systems, including the carrier, wheel, pedal, motor and control unit, along with their interactions. This usually happens because components, such as a brake system, might be unique or limited across all variants and are necessary for the basic function of many travelling concepts. Consequently, the semantic conceptual design stage is essential for exposing the basic components of any system. The connections between components can be used to identify functional relationships and dependencies. The semantic network diagram is characterized as a functional dependency (FD) between components. For example, if the wheel is on the road, then the wheel is a system component, and the road is another component. Thus, they are inter-dependent. Likewise, the computer is mounted on the vehicle carrier; thus, the carrier may transfer vibration, mechanical stress or noise to the computer, affecting its functionality or causing a system failure due to the functional dependencies.

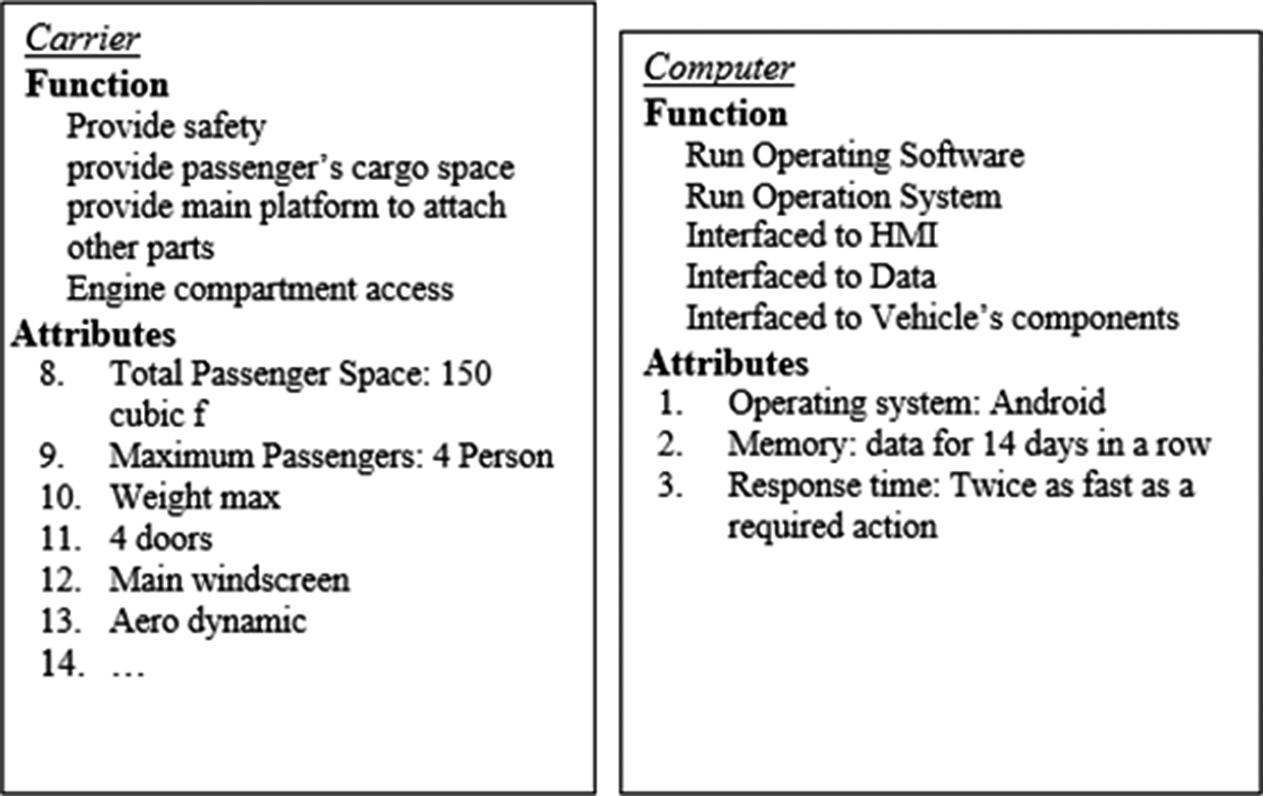

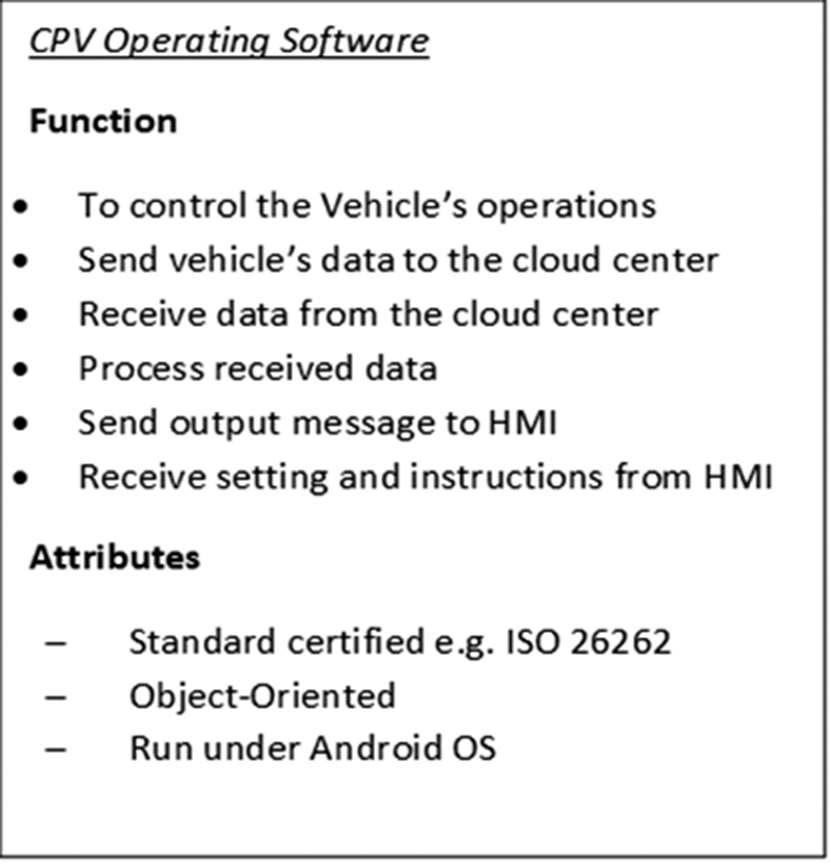

4.2. Abstractional design

To further abstract and classify these components, the abstractional design method is applied. Each system object is defined by its name, functions and attributes, facilitating reusability and cross-disciplinary understanding as demonstrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Application of the abstractional design method (ADM) illustrating object definition through functions and attributes for representative CPV components.

This approach allows designers to share concise component information across teams. For instance, the computer module combines software (functional) and hardware (attribute) aspects. Figure 7 illustrates the abstractional design of the vehicle’s operational software, emphasizing how functional behaviour evolves into detailed sub-components as the design matures.

Figure 7. Abstractional representation of CPV operational software, demonstrating functional decomposition and attribute definition within the ADM framework.

The abstractional model serves as a communication layer on top of the SCD between mechanical, electrical and software disciplines, ensuring that functional dependencies remain consistent throughout the design process by providing further essential details among the concerned design disciplines without overloading ‘unnecessary’ details at this stage.

4.3. Design structure matrix (DSM) and coupling analysis of acceleration pedal

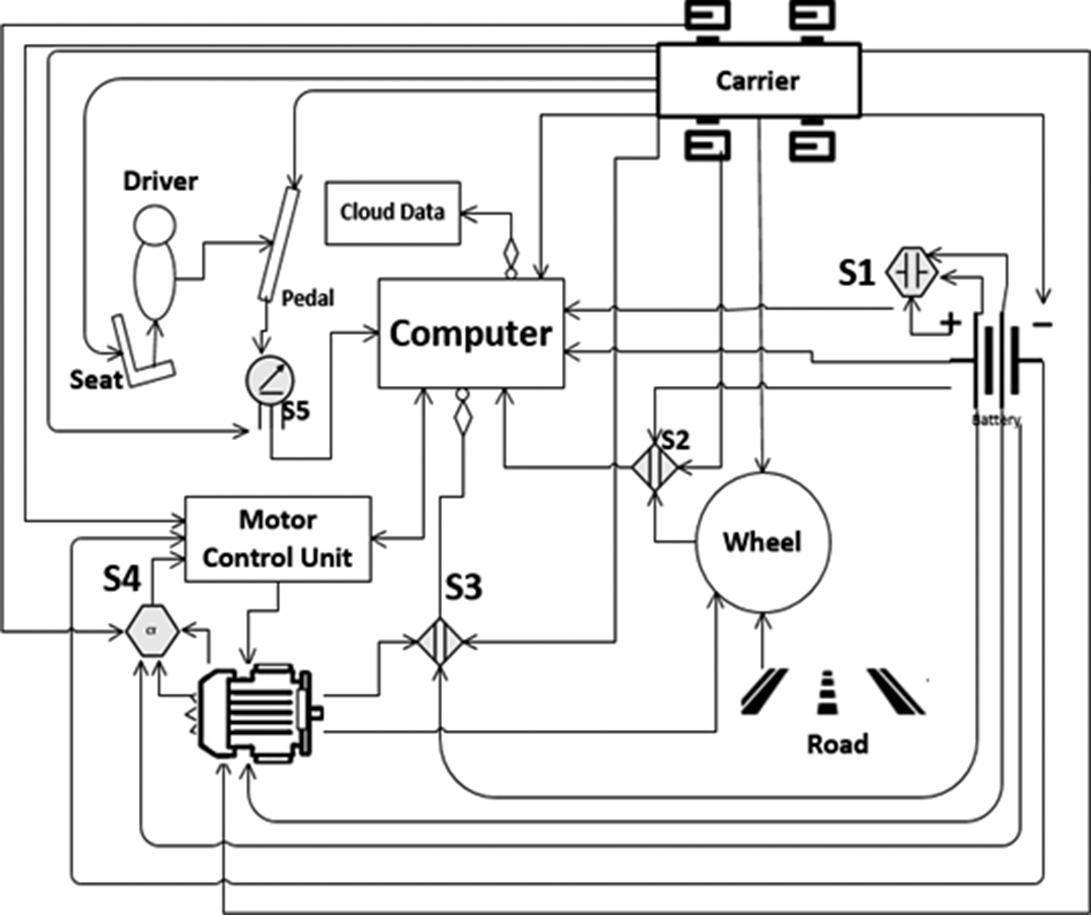

A design structure matrix (DSM) is developed from the CPV architecture to represent the interactions among components. The acceleration pedal sub-system was chosen as a representative component for analysis (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Baseline conceptual architecture of the CPV acceleration pedal sub-system showing multi-disciplinary component interactions.

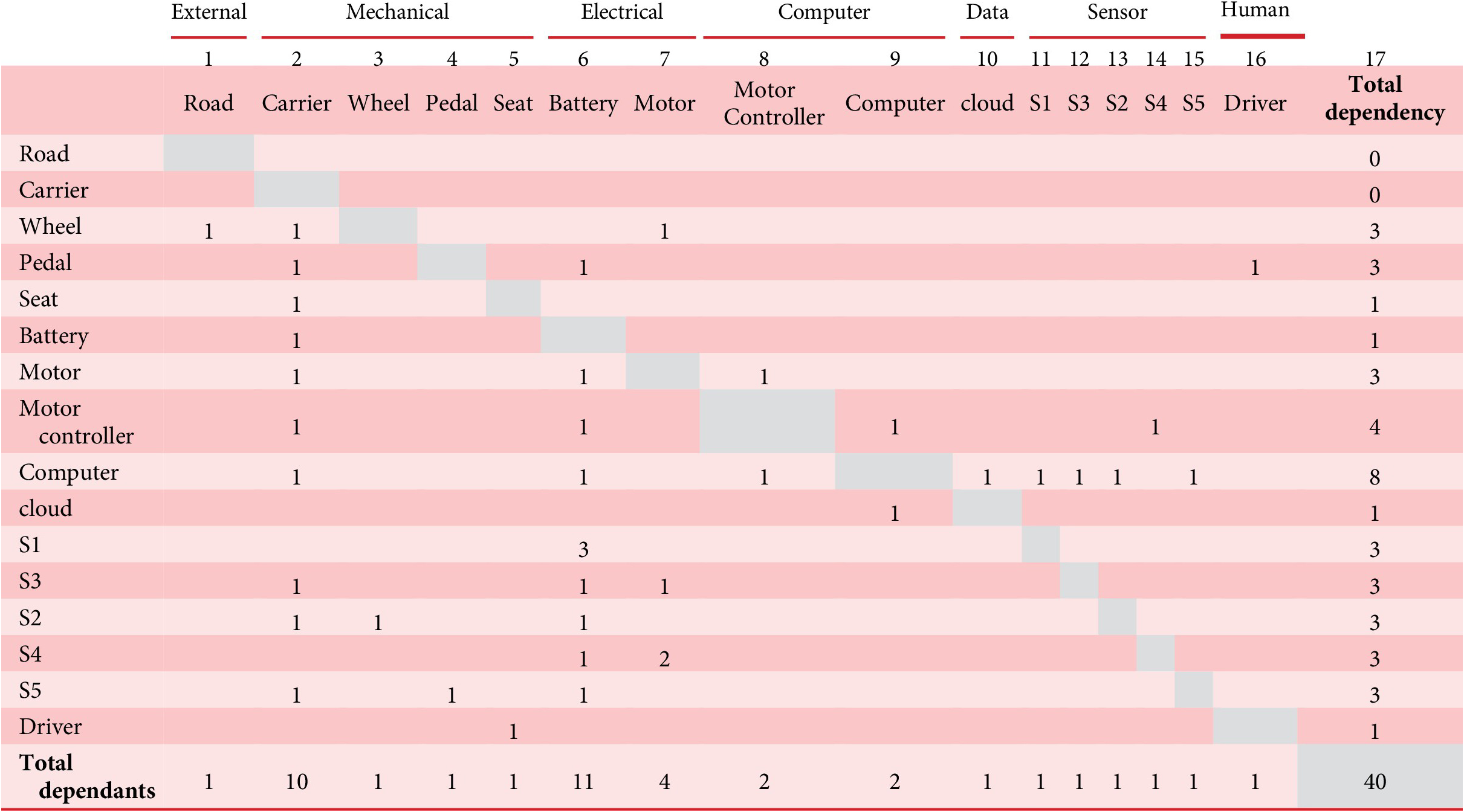

The DSM (Table 2) quantifies the inter-dependencies between elements such as the pedal, motor controller, battery, computer and cloud system. Each cell indicates the strength or direction of functional dependence between two components.

Table 2. DSM matrix for acceleration pedal design.

The matrix can be read horizontally as a functional dependency. Intuitively, the linking value is directional. The links are defined in terms of functional dependencies between multi-disciplinary components.

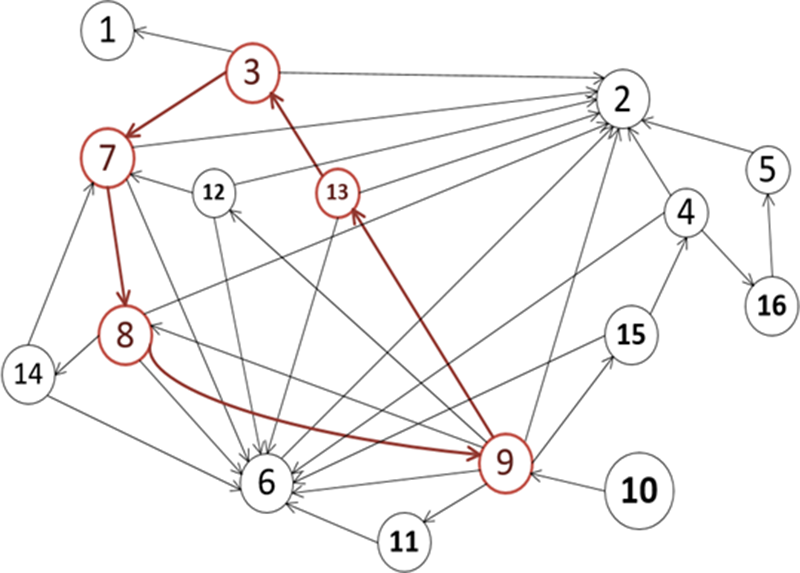

Analysis of the DSM revealed indirect multi-component coupling between elements (3, 7, 8, 9, 13), forming a closed dependency loop (Figure 9). Such loops can propagate failures through the system, a phenomenon known as the domino effect in system reliability. This coupling can be classified as a multi-component coupling because it forms a closed loop of dependencies among more than two components.

Figure 9. Network representation of indirect multi-component coupling within the acceleration pedal sub-system, illustrating a closed dependency loop.

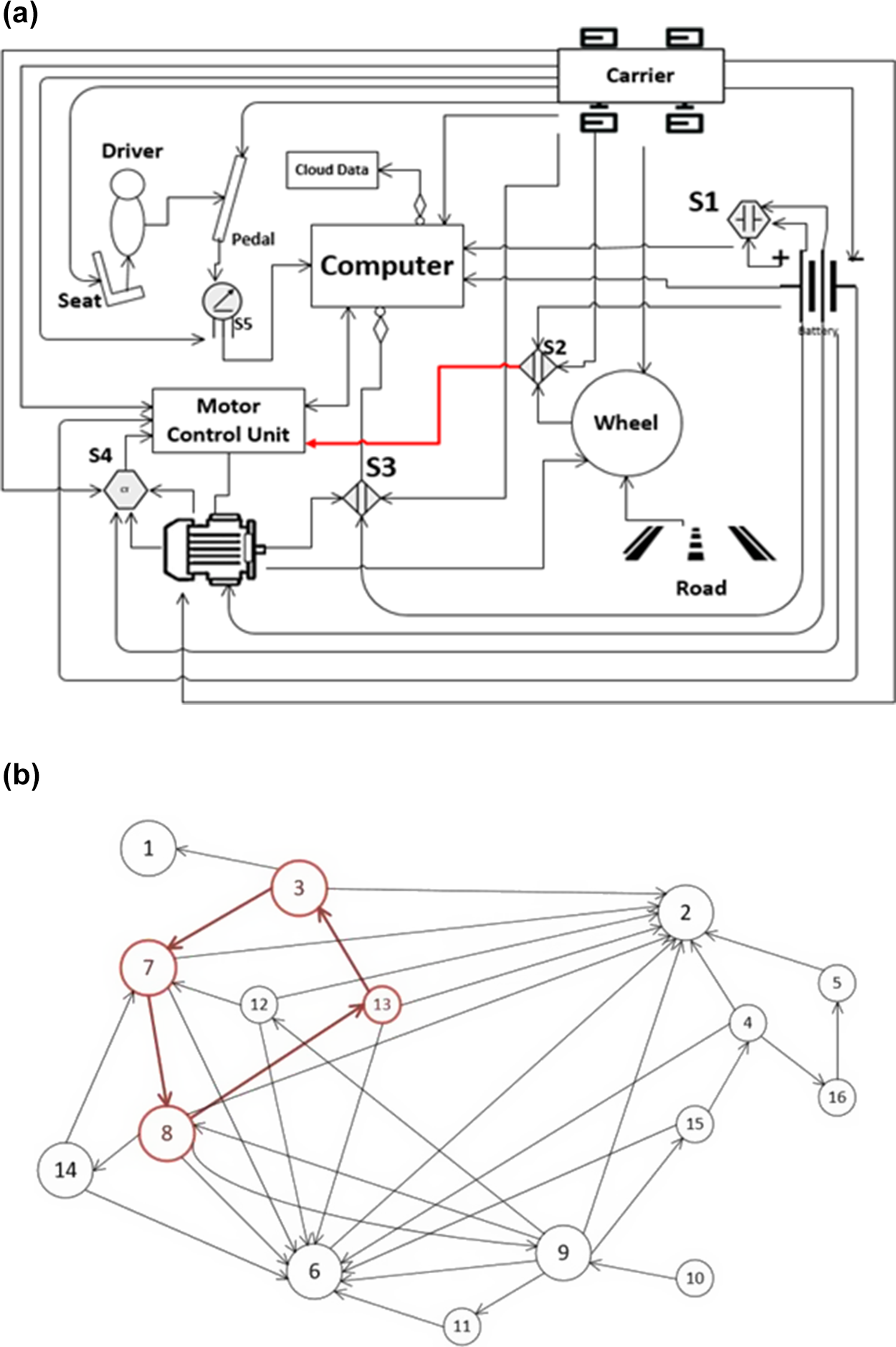

To mitigate this, an improved design (Figure 10) is proposed by reconfiguring the data flow and reducing inter-connections. This reduced the number of coupled components from six to five, thereby decreasing system complexity and potential failure propagation.

Figure 10. Modified CPV acceleration sub-system, (a) architecture and (b) network, after coupling reduction, demonstrating decreased indirect dependency and improved modularity.

4.4. Inter-coupling index (ICX) calculation

Using the values from Table 2 and the formula defined in Section 3.2, the ICX for the initial design (Figure 8) is calculated as:

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{c}{\mathrm{ICX}}_{3,7,8,9,13}=\left(4\times 0.01\right)+\left(6\times 1.378\right)+\left(4\times 4.522\right)\\ {}+\left(9\times 5.99\right)+\left(4\times 0.0375\right)=80.456\end{array}} $$

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{c}{\mathrm{ICX}}_{3,7,8,9,13}=\left(4\times 0.01\right)+\left(6\times 1.378\right)+\left(4\times 4.522\right)\\ {}+\left(9\times 5.99\right)+\left(4\times 0.0375\right)=80.456\end{array}} $$

The value of wheel failure could not be found, so it is presumed. The ICX value of these coupled components indicates their relative complexity. To examine the reduction of the complexity of the improved design in Figure 9, then:

This reduction confirms that modifying the conceptual architecture can quantitatively reduce system complexity by minimizing functional inter-dependencies.

4.5. Critical reflection and limitations

While the proposed framework effectively combines abstractional design and inter-coupling index (ICX) analysis to manage complexity, several limitations exist:

-

Subjectivity of decomposition: The identification of functional and sub-functional relationships depends on the designer’s interpretation, which may vary across teams or disciplines.

-

Scalability: As system size increases, the DSM and ICX calculations become computationally intensive, requiring automated tools for practical use.

-

Single-case validation: While reductions in ICX values are quantitatively demonstrated, the validation remains primarily conceptual and limited to illustrating coupling changes within the modelled architecture. Future work could strengthen validation through comparative multi-case studies, integration of empirical reliability data and benchmarking against established coupling metrics to assess scalability and system-level effects more rigorously.

-

New system-level implications: The emergence of new dependencies or shifts in risk distribution are not quantitatively assessed, as they fall outside the scope of the present methodological study.

-

Assumed data and simplifications: Some component parameters (e.g. failure probabilities) are estimated for demonstration purposes, which may affect the precision of ICX results.

5. Conclusion

This study advances the field of design science by introducing an integrative methodology for managing complexity in the conceptual design of multi-disciplinary systems, with a focus on cyber-physical vehicles (CPVs). By combining the abstractional design method (ADM) with the inter-coupling index (ICX), the proposed framework enables designers to model functional dependencies and evaluate indirect component interactions at an early stage.

ICX introduces the following innovations:

5.1. Integration of dependency and reliability

It is the first conceptual design metric to integrate coupling structure with failure-based vulnerability, enabling risk-weighted complexity assessment.

5.2. Inclusion of indirect coupling loops

Existing metrics typically assess pairwise dependencies.

ICX provides a mechanism to quantify multi-component, closed-loop coupling, a known source of cascading failures in CPS.

5.3. Applicability during conceptual design

Because it does not require geometric, change history or module structure data, ICX can be used directly at the earliest stage, where traditional metrics cannot be applied.

5.4. Cross-disciplinary suitability

ICX handles software, electrical, mechanical, data and human components equally, supporting multi-disciplinary CPS evaluation.

These characteristics collectively represent a methodological advance beyond purely structural or change-propagation-based coupling metrics. Additionally, this dual approach supports improved system comprehension, facilitates cross-disciplinary communication and promotes robustness in system architecture by revealing and reducing hidden couplings.

The case study of the CPV acceleration module illustrates the practical applicability of the methodology. It demonstrates how abstraction and dependency quantification can be leveraged to identify cascading failure risks and improve system modularity through conceptual restructuring. Furthermore, the proposed ICX metric provides a new quantitative lens for assessing design alternatives, making it a valuable tool for comparative evaluation in concurrent engineering environments.

Beyond the immediate application to CPVs, the methodology presented here is broadly transferable to other complex systems that require concurrent design across multiple engineering domains. Future research may extend this work by formalizing the ICX within broader design optimization frameworks, automating abstraction-based modelling processes and validating the approach across additional CPS domains. In line with the aims of Design Science, this research contributes not only a methodological innovation but also an actionable pathway towards more transparent, rational and resilient design practices in the face of growing systemic complexity.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Ontario Graduate Scholarship (OGS), Queen Elizabeth II and the NSERC Discovery Grants programme.