1. Introduction

The Latent Position Model (LPM) was introduced for social network analysis by Hoff et al. (Reference Hoff, Raftery and Handcock2002). An important feature of the LPM is that it facilitates network visualization via latent space modeling. The LPM assumes that the data distribution depends on the stochastic latent positions of the nodes of the network. Usually these latent positions are assumed to lie in a Euclidean space. We refer the reader to Kaur et al. (Reference Kaur, Rastelli and Friel2023); Rastelli et al. (Reference Rastelli, Friel and Raftery2016); Salter-Townshend et al. (Reference Salter-Townshend, White, Gollini and Murphy2012) for detailed reviews of this model. Clustering of nodes plays a central role in statistical network analysis: the LPM can be extended to this context following the pioneering work of Handcock et al. (Reference Handcock, Raftery and Tantrum2007). This leads us to the well-known Latent Position Cluster Model (LPCM) whereby the latent positions of the nodes are assumed to follow a mixture of multivariate normal distributions. With these assumptions, the network model can better support the presence of communities and assortative mixing.

A limitation of the original LPM and LPCM models is that they are only defined for the networks with binary interactions between the individuals. An interesting extension of these models to the weighted setting is provided by Sewell and Chen (Reference Sewell and Chen2015, Reference Sewell and Chen2016), where the authors extend the LPM to dynamic unipartite networks with weighted edges and propose a general link function for the expectation of the edge weights. In this paper, we focus on non-dynamic unipartite networks with non-negative discrete weighted edges, corresponding to networks where the edge values are typically integer counts.

Missing data is a common issue in statistical data analysis which generally leads to an overabundance of zeros. In this paper, we classify zero entries in a dataset either as “true” zeros or as “unusual” zeros. A zero-inflated model proposed by Lambert (Reference Lambert1992) assumes a probability model for the occurrence of unusual zeros, which can be paired with the Poisson distribution as a canonical choice for count weighted data. In this situation, an unusual zero may correspond to an edge that although present, the corresponding edge weight is not recorded.

Zero-inflation is well-explored in the area of regression models with many extensions, for example, Hall (Reference Hall2000), Ridout et al. (Reference Ridout, Hinde and Demétrio2001), Ghosh et al. (Reference Ghosh, Mukhopadhyay and Lu2006), Lemonte et al. (Reference Lemonte, Moreno-Arenas and Castellares2019) to cite a few. By contrast, zero-inflated models are not widely applied in the statistical analysis of network data. Zero-inflation is mentioned in Sewell and Chen (Reference Sewell and Chen2016): while their dynamic latent space model may be extended to the zero-inflated case for sparse networks, their applications do not cover this extension. Some advancements in this line of literature include Marchello et al. (Reference Marchello, Corneli and Bouveyron2024), which incorporate the zero-inflated model within the Latent Block Model (LBM) (Govaert and Nadif, Reference Govaert and Nadif2003) for dynamic bipartite networks, and Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Durante and Friel2025), which adopts the zero-inflation to the Stochastic Block Model (SBM) for unipartite networks. The SBM is widely used clustering model for network analysis that shares some similarities with the LPM, since both models are based on a latent variable framework. Differently from the LPM, the SBM is capable of representing disassortative patterns, but, on the other hand, the LPM can provide clearer and more interpretable network visualizations.

In this paper, we propose to incorporate a Zero-Inflated Poisson (ZIP) distribution within the LPCM leading to the Zero-Inflated Poisson Latent Position Cluster Model (ZIP-LPCM), and, in doing so, we create a simultaneous framework that can be used to characterize zero inflation, clustering and the latent space visualization. Similar model assumptions can be found in Ma (Reference Ma2024) where a Latent Space Zero-Inflated Poisson (LS-ZIP) model is proposed. However, differently from our model structure, their LS-ZIP embeds an inner-product latent space model (Hoff, Reference Hoff2003; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Ma and Yuan2020) and proposes two different sets of latent positions for the Poisson rate and for the probability of unusual zeros, respectively. Furthermore, their model does not account for the clustering of nodes, which is a central feature of our proposed model.

We employ a Bayesian framework to infer the model parameters and the latent variables of our ZIP-LPCM. Our inferential framework takes inspiration from the literature on the LPCM, the Mixture of Finite Mixtures (MFM) model (Miller and Harrison, Reference Miller and Harrison2018; Geng et al., Reference Geng, Bhattacharya and Pati2019), and collapsed Gibbs sampling, and we combine some key ideas from the available literature to create our own original procedure. As regards the LPCM, commonly used inference methods include a variational expectation maximization algorithm (Salter-Townshend and Murphy, Reference Salter-Townshend and Murphy2013), and Markov chain Monte Carlo methods (Handcock et al., Reference Handcock, Raftery and Tantrum2007). A contribution close to our own is that of Ryan et al. (Reference Ryan, Wyse and Friel2017) where the authors exploit conjugate priors to calculate a marginalized posterior in analytic form, and then target this distribution using a so-called “collapsed” sampler. Similar parameter-collapsing ideas are also employed in McDaid et al. (Reference McDaid, Murphy, Friel and Hurley2012); Wyse and Friel (Reference Wyse and Friel2012). In this paper, we propose to follow a similar strategy as that presented in Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Durante and Friel2025) for the inference task leveraging the partially collapsed Gibbs sampler introduced by Van Dyk and Park (Reference Van Dyk and Park2008); Park and Van Dyk (Reference Park and Van Dyk2009).

As regards the choice of the number of clusters, we also make an original contribution by combining some approaches and ideas available from the literature. We highlight Nobile and Fearnside (Reference Nobile and Fearnside2007), where the authors introduced an Absorb-Eject (AE) move to automatically choose the number of clusters. Here we propose a variant of this move to better match our framework. Indeed, as a prior distribution for the clustering variables and number of clusters, we adopt a MFM model, along with the supervision idea introduced by Legramanti et al. (Reference Legramanti, Rigon, Durante and Dunson2022). In this case, the AE move can further facilitate the estimation of clusters, but such a step can only be defined if the framework allows for the existence of empty clusters. Unfortunately, this is not the case for MFMs, and so the move and the model are incompatible. To address this impasse, we propose a new Truncated Absorb-Eject (TAE) move which allows us to efficiently explore the sample space thus obtaining good estimates of the clustering variables and of the number of groups.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a detailed introduction of our proposed ZIP-LPCM. Section 3 explains how we design the Bayesian inference process of our model where the incorporation of a mixture of finite mixtures model as well as its supervised version is included in Section 2.3. The idea of partially collapsing the model parameters in the posterior distribution, and the newly proposed TAE move, are introduced in Sections 3.1 and 3.2, respectively. The detailed steps and designs of the Partially Collapsed Metropolis-within-Gibbs (PCMwG) algorithm for the inference are illustrated in Section 3.3. In Section 4, we show the performance of our strategy via three carefully designed simulation studies within which different scenarios are proposed to tackle different real world situations. Applications on four different real social networks with different network sizes are included in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 concludes this paper and provides a few possible future directions.

2. Model

In this paper we focus on weighted networks with non-negative discrete edges, and denote

![]() $N$

as the total number of individuals in the network. This framework is particularly common in observed real datasets, most notably whereby edges indicate the intensity or frequency of interactions. Examples include some types of friendship and professional networks, email networks, phone call networks, proximity networks. In this paper we consider several real datasets, including a summit co-attendance network which records the number of times that two criminal suspects co-attended summits within a specified period. Since the edges indicate the number of co-attendances, these are observed as non-negative integers. The model introduced in this section is designed for directed networks, however it is straightforward to apply it to the undirected case. A network is usually observed by an

$N$

as the total number of individuals in the network. This framework is particularly common in observed real datasets, most notably whereby edges indicate the intensity or frequency of interactions. Examples include some types of friendship and professional networks, email networks, phone call networks, proximity networks. In this paper we consider several real datasets, including a summit co-attendance network which records the number of times that two criminal suspects co-attended summits within a specified period. Since the edges indicate the number of co-attendances, these are observed as non-negative integers. The model introduced in this section is designed for directed networks, however it is straightforward to apply it to the undirected case. A network is usually observed by an

![]() $N \times N$

adjacency matrix denoted as

$N \times N$

adjacency matrix denoted as

![]() ${\boldsymbol{Y}}$

, where each element

${\boldsymbol{Y}}$

, where each element

![]() $y_{ij}$

is a non-negative integer indicating the interaction from node

$y_{ij}$

is a non-negative integer indicating the interaction from node

![]() $i$

to node

$i$

to node

![]() $j$

, and reflecting the corresponding interaction strength. An element

$j$

, and reflecting the corresponding interaction strength. An element

![]() $y_{ij}=0$

corresponds to a non-interaction or a zero interaction. Self-loops are not allowed.

$y_{ij}=0$

corresponds to a non-interaction or a zero interaction. Self-loops are not allowed.

2.1 Zero-inflated Poisson model

In real networks which are observed in practice, there is often an overabundance of zeros. It is possible that these zeros are due to the nature of the network’s sparse architecture, but they may also be due to missing data or misreported data. Since practitioners are typically not aware of the presence of unusual zeros, we aim to provide a model-based solution that helps detecting any unusual zeros in the observed data.

We consider the ZIP model (Lambert, Reference Lambert1992), which is a commonly used framework to deal with an excessive number of zeros in

![]() ${\boldsymbol{Y}}$

. The ZIP model assumes that each observed interaction

${\boldsymbol{Y}}$

. The ZIP model assumes that each observed interaction

![]() $y_{ij}$

follows

$y_{ij}$

follows

\begin{align} \text{P}(y_{ij}|\lambda _{ij},p_{ij}) = \begin{cases} p_{ij} + (1-p_{ij})f_{\text{Pois}}(0|\lambda _{ij}),&\text{if } y_{ij}=0;\\[3pt] (1-p_{ij})f_{\text{Pois}}(y_{ij}|\lambda _{ij}),&\text{if } y_{ij}=1,2,\dots , \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} \text{P}(y_{ij}|\lambda _{ij},p_{ij}) = \begin{cases} p_{ij} + (1-p_{ij})f_{\text{Pois}}(0|\lambda _{ij}),&\text{if } y_{ij}=0;\\[3pt] (1-p_{ij})f_{\text{Pois}}(y_{ij}|\lambda _{ij}),&\text{if } y_{ij}=1,2,\dots , \end{cases} \end{align}

for

![]() $i,j=1,2,\dots ,N;\; i\neq j$

, where

$i,j=1,2,\dots ,N;\; i\neq j$

, where

![]() $f_{\text{Pois}}(\!\cdot |\lambda _{ij})$

is the probability mass function of the Poisson distribution with parameter

$f_{\text{Pois}}(\!\cdot |\lambda _{ij})$

is the probability mass function of the Poisson distribution with parameter

![]() $\lambda _{ij}$

. Here, the zeros assigned with probability mass

$\lambda _{ij}$

. Here, the zeros assigned with probability mass

![]() $p_{ij} + (1-p_{ij})f_{\text{Pois}}(0|\lambda _{ij})$

can be classified into two types: “structural” zeros, which are observed with probability

$p_{ij} + (1-p_{ij})f_{\text{Pois}}(0|\lambda _{ij})$

can be classified into two types: “structural” zeros, which are observed with probability

![]() $p_{ij}$

, and Poisson zeros, which naturally arise from the Poisson distribution, and are observed with probability

$p_{ij}$

, and Poisson zeros, which naturally arise from the Poisson distribution, and are observed with probability

![]() $(1-p_{ij})f_{\text{Pois}}(0|\lambda _{ij})$

, respectively. If we treat the Poisson zeros as the conventional zeros, then we refer to the other observed zeros as the “structural” or “unusual” zeros, since these are not determined according to the natural distribution that we assume on the data. We formalize the two possibilities by augmenting the model in Eq. (1) with a new indicator variable,

$(1-p_{ij})f_{\text{Pois}}(0|\lambda _{ij})$

, respectively. If we treat the Poisson zeros as the conventional zeros, then we refer to the other observed zeros as the “structural” or “unusual” zeros, since these are not determined according to the natural distribution that we assume on the data. We formalize the two possibilities by augmenting the model in Eq. (1) with a new indicator variable,

![]() $\nu _{ij}$

, indicating whether the corresponding

$\nu _{ij}$

, indicating whether the corresponding

![]() $y_{ij}$

is a structural zero or not, and thus the data distribution is determined separately for the two cases below:

$y_{ij}$

is a structural zero or not, and thus the data distribution is determined separately for the two cases below:

\begin{align} y_{ij}|\lambda _{ij},\nu _{ij} \sim \begin{cases} \unicode {x1D7D9}(y_{ij}=0),&\text{if } \nu _{ij}=1;\\[3pt] \text{Pois}(\lambda _{ij}),&\text{if } \nu _{ij}=0, \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} y_{ij}|\lambda _{ij},\nu _{ij} \sim \begin{cases} \unicode {x1D7D9}(y_{ij}=0),&\text{if } \nu _{ij}=1;\\[3pt] \text{Pois}(\lambda _{ij}),&\text{if } \nu _{ij}=0, \end{cases} \end{align}

where, for every

![]() $i$

and

$i$

and

![]() $j$

, the collection of

$j$

, the collection of

![]() $\nu _{ij}\sim \text{Bernoulli}(p_{ij})$

constitutes the

$\nu _{ij}\sim \text{Bernoulli}(p_{ij})$

constitutes the

![]() $N \times N$

structural zero indicator matrix

$N \times N$

structural zero indicator matrix

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }$

. The function

$\boldsymbol{\nu }$

. The function

![]() $\unicode {x1D7D9}(y_{ij}=0)$

is an indicator function returning

$\unicode {x1D7D9}(y_{ij}=0)$

is an indicator function returning

![]() $1$

if

$1$

if

![]() $y_{ij}=0$

and returning

$y_{ij}=0$

and returning

![]() $0$

otherwise.

$0$

otherwise.

As far as

![]() $\nu _{ij}=1$

, the observed

$\nu _{ij}=1$

, the observed

![]() $y_{ij}$

is a structural zero with probability

$y_{ij}$

is a structural zero with probability

![]() $1$

. Here, we interpret such a “structural” zero as an “unusual” zero or missing data that replaces a true interaction weight which follows the corresponding

$1$

. Here, we interpret such a “structural” zero as an “unusual” zero or missing data that replaces a true interaction weight which follows the corresponding

![]() $\text{Pois}(\lambda _{ij})$

distribution. A zero arising from

$\text{Pois}(\lambda _{ij})$

distribution. A zero arising from

![]() $f_{\text{Pois}}(\!\cdot |\lambda _{ij})$

is thus treated as a “true” zero. We denote the covert true interaction as

$f_{\text{Pois}}(\!\cdot |\lambda _{ij})$

is thus treated as a “true” zero. We denote the covert true interaction as

![]() $x_{ij}$

: we assume that this value is not observed when

$x_{ij}$

: we assume that this value is not observed when

![]() $\nu _{ij}=1$

, and that it follows the same Poisson distribution of

$\nu _{ij}=1$

, and that it follows the same Poisson distribution of

![]() $y_{ij}|\lambda _{ij},\nu _{ij}=0$

. Thus, based on the augmented zero-inflated model in Eq. (2) as well as the observed

$y_{ij}|\lambda _{ij},\nu _{ij}=0$

. Thus, based on the augmented zero-inflated model in Eq. (2) as well as the observed

![]() ${\boldsymbol{Y}}$

, the augmented data

${\boldsymbol{Y}}$

, the augmented data

![]() ${\boldsymbol{X}}$

, which is a

${\boldsymbol{X}}$

, which is a

![]() $N \times N$

matrix with entries

$N \times N$

matrix with entries

![]() $\{x_{ij}\}$

, is in the form

$\{x_{ij}\}$

, is in the form

\begin{align} \begin{cases} x_{ij}\sim \text{Pois}(\lambda _{ij}),&\text{if } \nu _{ij}=1;\\[3pt] x_{ij}=y_{ij},&\text{if } \nu _{ij}=0. \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} \begin{cases} x_{ij}\sim \text{Pois}(\lambda _{ij}),&\text{if } \nu _{ij}=1;\\[3pt] x_{ij}=y_{ij},&\text{if } \nu _{ij}=0. \end{cases} \end{align}

Here, the case

![]() $x_{ij}=y_{ij}$

is equivalent to

$x_{ij}=y_{ij}$

is equivalent to

![]() $x_{ij} \sim \unicode {x1D7D9}(x_{ij}=y_{ij})$

when

$x_{ij} \sim \unicode {x1D7D9}(x_{ij}=y_{ij})$

when

![]() $\nu _{ij}=0$

. A similar data augmentation framework has appeared in other works, for example, Tanner and Wong (Reference Tanner and Wong1987), Ghosh et al. (Reference Ghosh, Mukhopadhyay and Lu2006). The augmented

$\nu _{ij}=0$

. A similar data augmentation framework has appeared in other works, for example, Tanner and Wong (Reference Tanner and Wong1987), Ghosh et al. (Reference Ghosh, Mukhopadhyay and Lu2006). The augmented

![]() ${\boldsymbol{X}}$

is known as the missing data imputed adjacency matrix.

${\boldsymbol{X}}$

is known as the missing data imputed adjacency matrix.

2.2 Zero-inflated Poisson latent position cluster model

To characterize the Pois(

![]() $\lambda _{ij}$

) distribution under the

$\lambda _{ij}$

) distribution under the

![]() $\nu _{ij}=0$

case of the augmented ZIP model in Eq. (2), we employ the LPCM (Handcock et al., Reference Handcock, Raftery and Tantrum2007), which is an extended version of the Latent Position Model (LPM) (Hoff et al., Reference Hoff, Raftery and Handcock2002). Each node

$\nu _{ij}=0$

case of the augmented ZIP model in Eq. (2), we employ the LPCM (Handcock et al., Reference Handcock, Raftery and Tantrum2007), which is an extended version of the Latent Position Model (LPM) (Hoff et al., Reference Hoff, Raftery and Handcock2002). Each node

![]() $i\,:\, i=1,2,\dots ,N$

in the network is assumed to have a latent position

$i\,:\, i=1,2,\dots ,N$

in the network is assumed to have a latent position

![]() ${\boldsymbol{u}}_i\in \mathbb{R}^d$

, and we denote the collection of all latent positions as

${\boldsymbol{u}}_i\in \mathbb{R}^d$

, and we denote the collection of all latent positions as

![]() ${\boldsymbol{U}} \, :\!= \, \{{\boldsymbol{u}}_i\}$

. A generalization of the latent position model without considering covariates can be expressed in the form

${\boldsymbol{U}} \, :\!= \, \{{\boldsymbol{u}}_i\}$

. A generalization of the latent position model without considering covariates can be expressed in the form

![]() $g[\mathbb{E}(y_{ij})]=h({\boldsymbol{u}}_i,{\boldsymbol{u}}_j)$

, where

$g[\mathbb{E}(y_{ij})]=h({\boldsymbol{u}}_i,{\boldsymbol{u}}_j)$

, where

![]() $g(\! \cdot \!)$

is some link function, and

$g(\! \cdot \!)$

is some link function, and

![]() $h\,:\,\mathbb{R}^d\times \mathbb{R}^d\rightarrow \mathbb{R}$

is a function of two nodes’ latent positions. Here, we make standard assumptions on the functions

$h\,:\,\mathbb{R}^d\times \mathbb{R}^d\rightarrow \mathbb{R}$

is a function of two nodes’ latent positions. Here, we make standard assumptions on the functions

![]() $g(\! \cdot \!)$

and

$g(\! \cdot \!)$

and

![]() $h(\cdot ,\cdot )$

, which link the Poisson rate

$h(\cdot ,\cdot )$

, which link the Poisson rate

![]() $\lambda _{ij}$

in Eq. (2) with the latent positions

$\lambda _{ij}$

in Eq. (2) with the latent positions

![]() ${\boldsymbol{U}}$

as follows:

${\boldsymbol{U}}$

as follows:

In the equation above,

![]() $||\cdot ||$

is the Euclidean distance, while

$||\cdot ||$

is the Euclidean distance, while

![]() $\beta \in \mathbb{R}$

can be interpreted as an intercept term where higher values bring larger interaction weights as well as lower chance of a true zero. Note that the model characterization in Eq. (4) is symmetric for directed edges in directed networks, that is,

$\beta \in \mathbb{R}$

can be interpreted as an intercept term where higher values bring larger interaction weights as well as lower chance of a true zero. Note that the model characterization in Eq. (4) is symmetric for directed edges in directed networks, that is,

![]() $\log (\lambda _{ij}) = \log (\lambda _{ji})$

. This may be seen as a limitation of the framework, but it can be overcome when additional information, such as covariates, are available and thus are characterized in Eq. (4). We note that also other variations of latent space models, such as the projection model discussed in Hoff et al. (Reference Hoff, Raftery and Handcock2002) or the random effects model of Krivitsky et al. (Reference Krivitsky, Handcock, Raftery and Hoff2009), can be formulated in ways that allow for non-symmetric patterns. However, in this paper, we do not pursue this characteristic directly, but our model can certainly be adapted to deal with non-symmetric patterns.

$\log (\lambda _{ij}) = \log (\lambda _{ji})$

. This may be seen as a limitation of the framework, but it can be overcome when additional information, such as covariates, are available and thus are characterized in Eq. (4). We note that also other variations of latent space models, such as the projection model discussed in Hoff et al. (Reference Hoff, Raftery and Handcock2002) or the random effects model of Krivitsky et al. (Reference Krivitsky, Handcock, Raftery and Hoff2009), can be formulated in ways that allow for non-symmetric patterns. However, in this paper, we do not pursue this characteristic directly, but our model can certainly be adapted to deal with non-symmetric patterns.

The LPCM further assumes that each latent position

![]() ${\boldsymbol{u}}_i$

is drawn from a finite mixture of

${\boldsymbol{u}}_i$

is drawn from a finite mixture of

![]() $\bar {K}$

multivariate normal distributions, each corresponding to a different group:

$\bar {K}$

multivariate normal distributions, each corresponding to a different group:

\begin{equation} {\boldsymbol{u}}_i\sim \sum _{k=1}^{\bar {K}}\pi _k\text{MVN}_d(\boldsymbol{\mu }_k,1/\tau _k\mathbb{I}_d). \end{equation}

\begin{equation} {\boldsymbol{u}}_i\sim \sum _{k=1}^{\bar {K}}\pi _k\text{MVN}_d(\boldsymbol{\mu }_k,1/\tau _k\mathbb{I}_d). \end{equation}

Here, each

![]() $\pi _k$

is the probability that a node is clustered into group

$\pi _k$

is the probability that a node is clustered into group

![]() $k$

, and

$k$

, and

![]() $\sum _{k=1}^{\bar {K}}\pi _k=1$

. The combination of Eqs. (2), (4) and (5) defines our ZIP-LPCM.

$\sum _{k=1}^{\bar {K}}\pi _k=1$

. The combination of Eqs. (2), (4) and (5) defines our ZIP-LPCM.

Letting

![]() $z_i \in \{1,2,\dots ,\bar {K}\}$

denote the group membership of node

$z_i \in \{1,2,\dots ,\bar {K}\}$

denote the group membership of node

![]() $i$

, the mixture in Eq. (5) can be augmented as

$i$

, the mixture in Eq. (5) can be augmented as

where a multinomial

![]() $(1,\boldsymbol{\Pi })$

distribution is assumed for each

$(1,\boldsymbol{\Pi })$

distribution is assumed for each

![]() $\boldsymbol{z}_{\boldsymbol{i}}$

, and

$\boldsymbol{z}_{\boldsymbol{i}}$

, and

![]() $\boldsymbol{\Pi } \, :\!= \, (\pi _1,\pi _2,\dots ,\pi _{\bar {K}})$

. The notation

$\boldsymbol{\Pi } \, :\!= \, (\pi _1,\pi _2,\dots ,\pi _{\bar {K}})$

. The notation

![]() $\boldsymbol{z}_{\boldsymbol{i}} \, :\!= \, (z_{i1},z_{i2},\dots ,z_{i\bar {K}})$

is equivalent to

$\boldsymbol{z}_{\boldsymbol{i}} \, :\!= \, (z_{i1},z_{i2},\dots ,z_{i\bar {K}})$

is equivalent to

![]() $z_i=k$

if we let

$z_i=k$

if we let

![]() $z_{ig}=\unicode {x1D7D9}(g=k)$

for

$z_{ig}=\unicode {x1D7D9}(g=k)$

for

![]() $g=1,2,\dots ,\bar {K}$

, and thus

$g=1,2,\dots ,\bar {K}$

, and thus

![]() $f_{\text{multinomial}}(\boldsymbol{z}_{\boldsymbol{i}}|1,\boldsymbol{\Pi }) = \pi _{z_i}$

. Note that

$f_{\text{multinomial}}(\boldsymbol{z}_{\boldsymbol{i}}|1,\boldsymbol{\Pi }) = \pi _{z_i}$

. Note that

![]() $\bar {K}$

here denotes the total number of possible groups that the network is assumed to have, even though some groups may be empty. Further, we denote

$\bar {K}$

here denotes the total number of possible groups that the network is assumed to have, even though some groups may be empty. Further, we denote

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}} \, :\!= \, (z_1,z_2,\dots ,z_N)$

as a vector of group membership indicators for all

${\boldsymbol{z}} \, :\!= \, (z_1,z_2,\dots ,z_N)$

as a vector of group membership indicators for all

![]() $\{z_i\}$

, while

$\{z_i\}$

, while

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mu } \, :\!= \, \{\boldsymbol{\mu }_k\,:\,k=1,2,\dots ,\bar {K}\}$

, and

$\boldsymbol{\mu } \, :\!= \, \{\boldsymbol{\mu }_k\,:\,k=1,2,\dots ,\bar {K}\}$

, and

![]() $\boldsymbol{\tau } \, :\!= \, (\tau _1,\tau _2,\dots ,\tau _{\bar {K}})$

.

$\boldsymbol{\tau } \, :\!= \, (\tau _1,\tau _2,\dots ,\tau _{\bar {K}})$

.

The indicator of unusual zero

![]() $\nu _{ij}$

in Eq. (2) is proposed to instead follow a

$\nu _{ij}$

in Eq. (2) is proposed to instead follow a

![]() $\text{Bernoulli}(p_{z_iz_j})$

, that is, a typical Stochastic Block Model (SBM) structure is further assumed for

$\text{Bernoulli}(p_{z_iz_j})$

, that is, a typical Stochastic Block Model (SBM) structure is further assumed for

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }$

, where we replace the probability of unusual zero

$\boldsymbol{\nu }$

, where we replace the probability of unusual zero

![]() $p_{ij}$

with a cluster-dependent counterpart

$p_{ij}$

with a cluster-dependent counterpart

![]() $p_{z_iz_j}$

, as in a network block-structure. One intuition behind this is that the probability of an unusual zero observed between two nodes is expected to vary depending on their respective groups. Taking the summit co-attendance real network for criminal suspects as an example here, the occurrences of unusual zeros possibly correspond to different group-level secrecy strategies applied by the group leaders where some summits are intentionally hidden to the law enforcement investigations (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Durante and Friel2025), leading to different levels of unusual zero probability within and between different groups.

$p_{z_iz_j}$

, as in a network block-structure. One intuition behind this is that the probability of an unusual zero observed between two nodes is expected to vary depending on their respective groups. Taking the summit co-attendance real network for criminal suspects as an example here, the occurrences of unusual zeros possibly correspond to different group-level secrecy strategies applied by the group leaders where some summits are intentionally hidden to the law enforcement investigations (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Durante and Friel2025), leading to different levels of unusual zero probability within and between different groups.

There are other possible ways to model the probability of unusual zeros. A homogeneous setup where the probability is the same for all pairs of nodes is also possible, albeit naive. This would correspond to a special case of our framework. Alternatively, one may characterize the probability of unusual zeros using the latent distances. However, we eventually decided not to pursue this type of model formulation in this paper. One could argue: should the unusual zero probability be larger or smaller when the nodes are close to each other? Intuitively one could choose that a large distance would make it more likely that there is an unusual zero. However, it turns out that the Poisson distribution would also be more likely to give a zero in that case. So, the logic behind this assumption does not seem particularly convincing. On the other hand, a SBM structure can give disassortative patterns which can be more flexible for this particular task. In any case, we emphasize again that there is no one solution to this, and alternative approaches to ours may be perfectly valid. We denote

![]() ${\boldsymbol{P}}$

as a

${\boldsymbol{P}}$

as a

![]() $\bar {K} \times \bar {K}$

matrix with each entry

$\bar {K} \times \bar {K}$

matrix with each entry

![]() $p_{gh}$

denoting the probability of unusual zeros for the interactions from group

$p_{gh}$

denoting the probability of unusual zeros for the interactions from group

![]() $g$

to group

$g$

to group

![]() $h$

, where

$h$

, where

![]() $g,h=1,2,\dots ,\bar {K}$

.

$g,h=1,2,\dots ,\bar {K}$

.

The following Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) provides a clear visualization of the relationships between the observed adjacency matrix data

![]() ${\boldsymbol{Y}}$

and all the model latent variables and parameters as well as the augmented missing data imputed adjacency matrix

${\boldsymbol{Y}}$

and all the model latent variables and parameters as well as the augmented missing data imputed adjacency matrix

![]() ${\boldsymbol{X}}$

for our proposed ZIP-LPCM:

${\boldsymbol{X}}$

for our proposed ZIP-LPCM:

The complete likelihood of the ZIP-LPCM is thus written as:

\begin{align} & f({\boldsymbol{Y}}, \boldsymbol{\nu },{\boldsymbol{U}},{\boldsymbol{z}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{P}}, \boldsymbol{\mu }, \boldsymbol{\tau }, \boldsymbol{\Pi }) = f({\boldsymbol{Y}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })f(\boldsymbol{\nu }|{\boldsymbol{P}},{\boldsymbol{z}})f({\boldsymbol{U}}|\boldsymbol{\mu }, \boldsymbol{\tau }, {\boldsymbol{z}})f({\boldsymbol{z}}|\boldsymbol{\Pi }) \nonumber \\[2pt] &= \prod ^N_{\substack {i,j\,:\, i \neq j, \nonumber \\[2pt] \nu _{ij} = 0}}f_{\text{Pois}}(y_{ij}|\text{exp}(\beta -||{\boldsymbol{u}}_i-{\boldsymbol{u}}_j||)) \prod ^N_{i,j\,:\,i \neq j} f_{\text{Bern}}(\nu _{ij}|p_{z_iz_j}) \nonumber \\[2pt] &\hspace {1em}\times \prod ^N_{i =1} f_{\text{MVN}_d}({\boldsymbol{u}}_i|\boldsymbol{\mu }_{z_i},1/\tau _{z_i}\mathbb{I}_d) \prod ^N_{i =1} f_{\text{multinomial}}(\boldsymbol{z}_{\boldsymbol{i}}|1,\boldsymbol{\Pi }), \end{align}

\begin{align} & f({\boldsymbol{Y}}, \boldsymbol{\nu },{\boldsymbol{U}},{\boldsymbol{z}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{P}}, \boldsymbol{\mu }, \boldsymbol{\tau }, \boldsymbol{\Pi }) = f({\boldsymbol{Y}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })f(\boldsymbol{\nu }|{\boldsymbol{P}},{\boldsymbol{z}})f({\boldsymbol{U}}|\boldsymbol{\mu }, \boldsymbol{\tau }, {\boldsymbol{z}})f({\boldsymbol{z}}|\boldsymbol{\Pi }) \nonumber \\[2pt] &= \prod ^N_{\substack {i,j\,:\, i \neq j, \nonumber \\[2pt] \nu _{ij} = 0}}f_{\text{Pois}}(y_{ij}|\text{exp}(\beta -||{\boldsymbol{u}}_i-{\boldsymbol{u}}_j||)) \prod ^N_{i,j\,:\,i \neq j} f_{\text{Bern}}(\nu _{ij}|p_{z_iz_j}) \nonumber \\[2pt] &\hspace {1em}\times \prod ^N_{i =1} f_{\text{MVN}_d}({\boldsymbol{u}}_i|\boldsymbol{\mu }_{z_i},1/\tau _{z_i}\mathbb{I}_d) \prod ^N_{i =1} f_{\text{multinomial}}(\boldsymbol{z}_{\boldsymbol{i}}|1,\boldsymbol{\Pi }), \end{align}

which can be calculated analytically and efficiently for all choices of parameter values.

2.3 Mixture of finite mixtures and supervision

Instead of the multinomial distribution, we further consider the Mixture-of-Finite-Mixtures (MFM) model for the clustering

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}$

, because such a model is actually an extension of the Dirichlet-multinational conjugacy and allows the corresponding inference procedure to automatically choose the number of clusters.

${\boldsymbol{z}}$

, because such a model is actually an extension of the Dirichlet-multinational conjugacy and allows the corresponding inference procedure to automatically choose the number of clusters.

A natural conjugate prior for the multinomial parameters is

By further proposing a prior

![]() $\bar {K}\sim \pi _{\bar {K}}(\! \cdot \!)$

, the MFM marginalizes both

$\bar {K}\sim \pi _{\bar {K}}(\! \cdot \!)$

, the MFM marginalizes both

![]() $\boldsymbol{\Pi }$

and

$\boldsymbol{\Pi }$

and

![]() $\bar {K}$

, leading to the probability mass function of a MFM, which is defined for the unlabeled clustering and reads as follows:

$\bar {K}$

, leading to the probability mass function of a MFM, which is defined for the unlabeled clustering and reads as follows:

\begin{equation} \begin{split} f({\boldsymbol{C}}({\boldsymbol{z}}))= \sum _{k=1}^{\infty } \frac {k_{(K)}}{(k\alpha )^{(N)}}\pi _{\bar {K}}(k)\prod _{G\in {\boldsymbol{C}}({\boldsymbol{z}})} \alpha ^{(|G|)}, \end{split} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{split} f({\boldsymbol{C}}({\boldsymbol{z}}))= \sum _{k=1}^{\infty } \frac {k_{(K)}}{(k\alpha )^{(N)}}\pi _{\bar {K}}(k)\prod _{G\in {\boldsymbol{C}}({\boldsymbol{z}})} \alpha ^{(|G|)}, \end{split} \end{equation}

where

![]() ${\boldsymbol{C}}({\boldsymbol{z}}) \, :\!= \, \{G_k\,:\, k=1,2,\dots ,\bar {K};\;|G_k|\gt 0\}$

is a set of non-empty unordered collections of nodes with each collection

${\boldsymbol{C}}({\boldsymbol{z}}) \, :\!= \, \{G_k\,:\, k=1,2,\dots ,\bar {K};\;|G_k|\gt 0\}$

is a set of non-empty unordered collections of nodes with each collection

![]() $G_k \, :\!= \, \{i\,:\,i=1,2,\dots ,N;\;z_i=k\}$

containing all the nodes from group

$G_k \, :\!= \, \{i\,:\,i=1,2,\dots ,N;\;z_i=k\}$

containing all the nodes from group

![]() $k$

. Here,

$k$

. Here,

![]() $|G_k|$

denotes the number of nodes inside the collection, and the number of non-empty collections/groups

$|G_k|$

denotes the number of nodes inside the collection, and the number of non-empty collections/groups

![]() $K \, :\!= \, |{\boldsymbol{C}}({\boldsymbol{z}})|$

. In the case that

$K \, :\!= \, |{\boldsymbol{C}}({\boldsymbol{z}})|$

. In the case that

![]() $G_k$

is the empty set, we have

$G_k$

is the empty set, we have

![]() $|G_k|=0$

. The ascending factorial notation

$|G_k|=0$

. The ascending factorial notation

![]() $\alpha ^{(n)} \, :\!= \, \alpha (\alpha +1)\cdots (\alpha +n-1)$

, while the descending factorial notation

$\alpha ^{(n)} \, :\!= \, \alpha (\alpha +1)\cdots (\alpha +n-1)$

, while the descending factorial notation

![]() $k_{(K)} \, :\!= \, k(k-1)\cdots (k-(K-1))$

. The parameter

$k_{(K)} \, :\!= \, k(k-1)\cdots (k-(K-1))$

. The parameter

![]() $\bar {K}$

is collapsed by summing over all the possible

$\bar {K}$

is collapsed by summing over all the possible

![]() $\bar {K}=k$

values from

$\bar {K}=k$

values from

![]() $k=1$

to

$k=1$

to

![]() $k=\infty$

. Note that

$k=\infty$

. Note that

![]() ${\boldsymbol{C}}({\boldsymbol{z}})$

is invariant under any relabeling of

${\boldsymbol{C}}({\boldsymbol{z}})$

is invariant under any relabeling of

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}$

. The

${\boldsymbol{z}}$

. The

![]() $k_{(K)}\equiv \binom {k}{K}K!$

term in Eq. (7) is the number of ways to relabel a specific

$k_{(K)}\equiv \binom {k}{K}K!$

term in Eq. (7) is the number of ways to relabel a specific

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}$

or to label the unlabeled partition

${\boldsymbol{z}}$

or to label the unlabeled partition

![]() ${\boldsymbol{C}}({\boldsymbol{z}})$

provided with

${\boldsymbol{C}}({\boldsymbol{z}})$

provided with

![]() $\bar {K}=k$

. The natural choice of

$\bar {K}=k$

. The natural choice of

![]() $\bar {K}$

prior is a zero-truncated Poisson(1) distribution (Geng et al., Reference Geng, Bhattacharya and Pati2019; Nobile, Reference Nobile2005; McDaid et al., Reference McDaid, Murphy, Friel and Hurley2012) that is assumed throughout this paper.

$\bar {K}$

prior is a zero-truncated Poisson(1) distribution (Geng et al., Reference Geng, Bhattacharya and Pati2019; Nobile, Reference Nobile2005; McDaid et al., Reference McDaid, Murphy, Friel and Hurley2012) that is assumed throughout this paper.

To ensure that the clustering

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}$

is invariant under any relabeling of it, we adopt a particular labeling method following the procedure used in Rastelli and Friel (Reference Rastelli and Friel2018). We assign node

${\boldsymbol{z}}$

is invariant under any relabeling of it, we adopt a particular labeling method following the procedure used in Rastelli and Friel (Reference Rastelli and Friel2018). We assign node

![]() $1$

to group

$1$

to group

![]() $1$

by default, and then iteratively assign the next node either to a new empty group or to an existing group. In this way, the defined

$1$

by default, and then iteratively assign the next node either to a new empty group or to an existing group. In this way, the defined

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}$

only contains

${\boldsymbol{z}}$

only contains

![]() $K$

occupied groups and is one-to-one correspondence to

$K$

occupied groups and is one-to-one correspondence to

![]() ${\boldsymbol{C}}({\boldsymbol{z}})$

regardless of whether the clustering before label-switching has empty groups or not. The clustering dependent parameters,

${\boldsymbol{C}}({\boldsymbol{z}})$

regardless of whether the clustering before label-switching has empty groups or not. The clustering dependent parameters,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mu },\boldsymbol{\tau }$

and

$\boldsymbol{\mu },\boldsymbol{\tau }$

and

![]() ${\boldsymbol{P}}$

are relabeled accordingly and the entries relevant to empty groups are treated as redundant. The probability mass function of the MFM in Eq. (7) may be rewritten as

${\boldsymbol{P}}$

are relabeled accordingly and the entries relevant to empty groups are treated as redundant. The probability mass function of the MFM in Eq. (7) may be rewritten as

\begin{equation} \begin{split} f({\boldsymbol{z}})= \mathcal{W}_{N,K}\prod ^K_{g=1} \alpha ^{(n_g)}, \end{split} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{split} f({\boldsymbol{z}})= \mathcal{W}_{N,K}\prod ^K_{g=1} \alpha ^{(n_g)}, \end{split} \end{equation}

where

![]() $n_g$

is the number of nodes in group

$n_g$

is the number of nodes in group

![]() $g$

. The non-negative weight

$g$

. The non-negative weight

satisfies the recursion

![]() $\mathcal{W}_{N,K} \, :\!= \, (N+K\alpha )\mathcal{W}_{N+1,K}+\alpha \mathcal{W}_{N+1,K+1}$

with

$\mathcal{W}_{N,K} \, :\!= \, (N+K\alpha )\mathcal{W}_{N+1,K}+\alpha \mathcal{W}_{N+1,K+1}$

with

![]() $\mathcal{W}_{1,1}=1/\alpha$

, and we refer to Miller and Harrison (Reference Miller and Harrison2018) for the details of the computation of

$\mathcal{W}_{1,1}=1/\alpha$

, and we refer to Miller and Harrison (Reference Miller and Harrison2018) for the details of the computation of

![]() $\mathcal{W}_{N,K}$

.

$\mathcal{W}_{N,K}$

.

One could proceed to determine a generative/predictive urn scheme by checking the formulae differences between the

![]() $f({\boldsymbol{z}})$

and each

$f({\boldsymbol{z}})$

and each

![]() $f(\{{\boldsymbol{z}},z_{N+1}\})$

for

$f(\{{\boldsymbol{z}},z_{N+1}\})$

for

![]() $z_{N+1}=1,2,\dots ,K,K+1$

. Then, sampling from Eq. (8) can be performed using the following procedure: assuming that the first node labeled as node

$z_{N+1}=1,2,\dots ,K,K+1$

. Then, sampling from Eq. (8) can be performed using the following procedure: assuming that the first node labeled as node

![]() $1$

is assigned to group

$1$

is assigned to group

![]() $1$

by default, then the probability of the subsequent node being assigned to existing non-empty groups or to a new empty group is defined as:

$1$

by default, then the probability of the subsequent node being assigned to existing non-empty groups or to a new empty group is defined as:

\begin{align} \text{P}(z_{N+1}=k|{\boldsymbol{z}}) \propto \begin{cases} n_k+\alpha , & \text{for}\;k = 1,2,\dots ,K;\\[8pt] \dfrac {\mathcal{W}_{N+1,K+1}}{\mathcal{W}_{N+1,K}}\alpha , & \text{for}\;k = K+1, \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} \text{P}(z_{N+1}=k|{\boldsymbol{z}}) \propto \begin{cases} n_k+\alpha , & \text{for}\;k = 1,2,\dots ,K;\\[8pt] \dfrac {\mathcal{W}_{N+1,K+1}}{\mathcal{W}_{N+1,K}}\alpha , & \text{for}\;k = K+1, \end{cases} \end{align}

that is conditional on the current clustering

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}$

with parameters

${\boldsymbol{z}}$

with parameters

![]() $N$

and

$N$

and

![]() $K$

, where

$K$

, where

![]() $n_k$

is defined as the number of nodes in group

$n_k$

is defined as the number of nodes in group

![]() $k$

. We refer to Theorem 4.1 of Miller and Harrison (Reference Miller and Harrison2018) for a more detailed discussion on this generative procedure. This generative scheme also belongs to the Ewens-Pitman two-parameter family of Exchangeable Partitions (Gnedin et al., Reference Gnedin, Haulk and Pitman2009; Pitman, Reference Pitman2006).

$k$

. We refer to Theorem 4.1 of Miller and Harrison (Reference Miller and Harrison2018) for a more detailed discussion on this generative procedure. This generative scheme also belongs to the Ewens-Pitman two-parameter family of Exchangeable Partitions (Gnedin et al., Reference Gnedin, Haulk and Pitman2009; Pitman, Reference Pitman2006).

Some exogenous node attributes may be available when analyzing real datasets, and, in this case, we leverage the idea of supervised priors proposed by Legramanti et al. (Reference Legramanti, Rigon, Durante and Dunson2022) to account for such information in the modeling. We use

![]() ${\boldsymbol{c}} = \{c_1,c_2,\dots ,c_N\}$

to denote the categorical node attributes in our context where each

${\boldsymbol{c}} = \{c_1,c_2,\dots ,c_N\}$

to denote the categorical node attributes in our context where each

![]() $c_i\in \{1,2,\dots ,C\}$

, and propose that

$c_i\in \{1,2,\dots ,C\}$

, and propose that

\begin{align} f({\boldsymbol{z}}|{\boldsymbol{c}}) &\propto \mathcal{W}_{N,K}\prod ^{K}_{g=1}\text{P}({\boldsymbol{c}}_g)\alpha ^{(n_g)}, \end{align}

\begin{align} f({\boldsymbol{z}}|{\boldsymbol{c}}) &\propto \mathcal{W}_{N,K}\prod ^{K}_{g=1}\text{P}({\boldsymbol{c}}_g)\alpha ^{(n_g)}, \end{align}

where

![]() ${\boldsymbol{c}}_g \, :\!= \, \{c_i\,:\, z_i = g\}$

and where the distribution

${\boldsymbol{c}}_g \, :\!= \, \{c_i\,:\, z_i = g\}$

and where the distribution

![]() $\text{P}({\boldsymbol{c}}_g)$

is chosen as the Dirichlet-multinomial cohesion of Müller et al. (Reference Müller, Quintana and Rosner2011), which is given by:

$\text{P}({\boldsymbol{c}}_g)$

is chosen as the Dirichlet-multinomial cohesion of Müller et al. (Reference Müller, Quintana and Rosner2011), which is given by:

\begin{align} \text{P}({\boldsymbol{c}}_g) = \frac {\prod ^C_{c=1}\Gamma \left (n_{g,c}+\omega _c\right )}{\Gamma \left (n_g+\omega _0\right )}\frac {\Gamma \left (\omega _0\right )}{\prod ^C_{c=1}\Gamma \left (\omega _c\right )}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \text{P}({\boldsymbol{c}}_g) = \frac {\prod ^C_{c=1}\Gamma \left (n_{g,c}+\omega _c\right )}{\Gamma \left (n_g+\omega _0\right )}\frac {\Gamma \left (\omega _0\right )}{\prod ^C_{c=1}\Gamma \left (\omega _c\right )}. \end{align}

Here,

![]() $n_{g,c}$

denotes the number of nodes in group

$n_{g,c}$

denotes the number of nodes in group

![]() $g$

that have the node attribute

$g$

that have the node attribute

![]() $c$

, whereas

$c$

, whereas

![]() $\omega _c$

is the cohesion parameter for each level

$\omega _c$

is the cohesion parameter for each level

![]() $c$

of the node attributes and

$c$

of the node attributes and

![]() $\omega _0 = \sum ^C_{c=1}\omega _c$

. Similar to Eq. (9), we can determine an urn scheme also for the supervised MFM as:

$\omega _0 = \sum ^C_{c=1}\omega _c$

. Similar to Eq. (9), we can determine an urn scheme also for the supervised MFM as:

\begin{align} \text{P}(z_{N+1}=k|{\boldsymbol{z}},{\boldsymbol{c}},c_{N+1}) \propto \begin{cases} \dfrac {n_{k,c_{N+1}}+\omega _{c_{N+1}}}{n_k+\omega _0}(n_k+\alpha ), & \text{for } k=1,2,\dots ,K; \\[12pt] \dfrac {\omega _{c_{N+1}}}{\omega _0}\dfrac {\mathcal{W}_{N+1,K+1}}{\mathcal{W}_{N+1,K}}\alpha , & \text{for } k = K+1, \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} \text{P}(z_{N+1}=k|{\boldsymbol{z}},{\boldsymbol{c}},c_{N+1}) \propto \begin{cases} \dfrac {n_{k,c_{N+1}}+\omega _{c_{N+1}}}{n_k+\omega _0}(n_k+\alpha ), & \text{for } k=1,2,\dots ,K; \\[12pt] \dfrac {\omega _{c_{N+1}}}{\omega _0}\dfrac {\mathcal{W}_{N+1,K+1}}{\mathcal{W}_{N+1,K}}\alpha , & \text{for } k = K+1, \end{cases} \end{align}

which, compared to Eq. (9), is inflated or deflated by a term that favors allocating the new node

![]() $N+1$

to the group with higher fraction of the same node attribute as the

$N+1$

to the group with higher fraction of the same node attribute as the

![]() $c_{N+1}$

, that is, the allocation is supervised by

$c_{N+1}$

, that is, the allocation is supervised by

![]() ${\boldsymbol{c}}$

.

${\boldsymbol{c}}$

.

Note that, in the case that some categorical node attributes

![]() ${\boldsymbol{c}}$

are available, these can be considered as a reference clustering under the MFM framework. For example, individuals in a social network can be clustered into different groups based on their affiliations, while they can also be clustered in a different way according to their job categories. However, none of these reference clusterings might be the “true” clustering or the “best” clustering for the network. Our supervised MFM framework can be treated as a type of supervised prior, in the sense of Legramanti et al. (Reference Legramanti, Rigon, Durante and Dunson2022), with a reference clustering

${\boldsymbol{c}}$

are available, these can be considered as a reference clustering under the MFM framework. For example, individuals in a social network can be clustered into different groups based on their affiliations, while they can also be clustered in a different way according to their job categories. However, none of these reference clusterings might be the “true” clustering or the “best” clustering for the network. Our supervised MFM framework can be treated as a type of supervised prior, in the sense of Legramanti et al. (Reference Legramanti, Rigon, Durante and Dunson2022), with a reference clustering

![]() ${\boldsymbol{c}}$

: this should not be confused with the general idea of supervised learning, which is often used in similar contexts. We refer to Legramanti et al. (Reference Legramanti, Rigon, Durante and Dunson2022) for more details on the use and terminology of supervised priors.

${\boldsymbol{c}}$

: this should not be confused with the general idea of supervised learning, which is often used in similar contexts. We refer to Legramanti et al. (Reference Legramanti, Rigon, Durante and Dunson2022) for more details on the use and terminology of supervised priors.

3. Partially collapsed Bayesian inference

In this section, we illustrate our original inference processes which aim to jointly infer the intercept

![]() $\beta$

, the indicator of unusual zeros

$\beta$

, the indicator of unusual zeros

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }$

, the latent positions

$\boldsymbol{\nu }$

, the latent positions

![]() ${\boldsymbol{U}}$

, the latent clustering indicator

${\boldsymbol{U}}$

, the latent clustering indicator

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}$

and the number of occupied groups

${\boldsymbol{z}}$

and the number of occupied groups

![]() $K$

. The model includes other parameters, such as

$K$

. The model includes other parameters, such as

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mu }$

and

$\boldsymbol{\mu }$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{\tau }$

, which are dealt with via marginalization, as shown in Section 3.1. We emphasize that

$\boldsymbol{\tau }$

, which are dealt with via marginalization, as shown in Section 3.1. We emphasize that

![]() $K$

indicates the number of occupied groups for the clustering

$K$

indicates the number of occupied groups for the clustering

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}$

, and thus can be calculated directly from

${\boldsymbol{z}}$

, and thus can be calculated directly from

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}$

. This should not be confused with the total number of groups

${\boldsymbol{z}}$

. This should not be confused with the total number of groups

![]() $\bar {K}$

. This distinction is crucial since we leverage mixture-of-finite-mixtures (Miller and Harrison, Reference Miller and Harrison2018; Geng et al., Reference Geng, Bhattacharya and Pati2019) to marginalize

$\bar {K}$

. This distinction is crucial since we leverage mixture-of-finite-mixtures (Miller and Harrison, Reference Miller and Harrison2018; Geng et al., Reference Geng, Bhattacharya and Pati2019) to marginalize

![]() $\bar {K}$

in Section 2.3. As a result, we only need to focus on non-empty groups during the inference procedures.

$\bar {K}$

in Section 2.3. As a result, we only need to focus on non-empty groups during the inference procedures.

3.1 Inference and collapsing

In the case that the exogenous node attributes

![]() ${\boldsymbol{c}}$

are available, adopting the supervised MFM introduced in Eq. (10) as well as the missing data imputation shown in Eq. (3) leads to the posterior distribution of our ZIP-LPCM being written as:

${\boldsymbol{c}}$

are available, adopting the supervised MFM introduced in Eq. (10) as well as the missing data imputation shown in Eq. (3) leads to the posterior distribution of our ZIP-LPCM being written as:

\begin{align} \pi ({\boldsymbol{X}}, \boldsymbol{\nu }, {\boldsymbol{U}}, {\boldsymbol{z}},\beta ,{\boldsymbol{P}},\boldsymbol{\mu },\boldsymbol{\tau }|{\boldsymbol{Y}},{\boldsymbol{c}}) &\propto f({\boldsymbol{X}}|{\boldsymbol{Y}}, \beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })f({\boldsymbol{Y}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })f(\boldsymbol{\nu }|{\boldsymbol{P}},{\boldsymbol{z}})f({\boldsymbol{U}}|\boldsymbol{\mu },\boldsymbol{\tau },{\boldsymbol{z}}) f({\boldsymbol{z}}|{\boldsymbol{c}}) \nonumber \\[4pt]&\hspace {1em}\times \pi ({\boldsymbol{P}})\pi (\boldsymbol{\mu })\pi (\boldsymbol{\tau })\pi (\beta ) \nonumber \\[4pt] &=f({\boldsymbol{X}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}})f(\boldsymbol{\nu }|{\boldsymbol{P}},{\boldsymbol{z}})f({\boldsymbol{U}}|\boldsymbol{\mu },\boldsymbol{\tau },{\boldsymbol{z}})f({\boldsymbol{z}}|{\boldsymbol{c}})\pi ({\boldsymbol{P}})\pi (\boldsymbol{\mu })\pi (\boldsymbol{\tau })\pi (\beta ), \end{align}

\begin{align} \pi ({\boldsymbol{X}}, \boldsymbol{\nu }, {\boldsymbol{U}}, {\boldsymbol{z}},\beta ,{\boldsymbol{P}},\boldsymbol{\mu },\boldsymbol{\tau }|{\boldsymbol{Y}},{\boldsymbol{c}}) &\propto f({\boldsymbol{X}}|{\boldsymbol{Y}}, \beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })f({\boldsymbol{Y}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })f(\boldsymbol{\nu }|{\boldsymbol{P}},{\boldsymbol{z}})f({\boldsymbol{U}}|\boldsymbol{\mu },\boldsymbol{\tau },{\boldsymbol{z}}) f({\boldsymbol{z}}|{\boldsymbol{c}}) \nonumber \\[4pt]&\hspace {1em}\times \pi ({\boldsymbol{P}})\pi (\boldsymbol{\mu })\pi (\boldsymbol{\tau })\pi (\beta ) \nonumber \\[4pt] &=f({\boldsymbol{X}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}})f(\boldsymbol{\nu }|{\boldsymbol{P}},{\boldsymbol{z}})f({\boldsymbol{U}}|\boldsymbol{\mu },\boldsymbol{\tau },{\boldsymbol{z}})f({\boldsymbol{z}}|{\boldsymbol{c}})\pi ({\boldsymbol{P}})\pi (\boldsymbol{\mu })\pi (\boldsymbol{\tau })\pi (\beta ), \end{align}

where the

![]() $f({\boldsymbol{Y}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })$

, the

$f({\boldsymbol{Y}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })$

, the

![]() $f(\boldsymbol{\nu }|{\boldsymbol{P}},{\boldsymbol{z}})$

and the

$f(\boldsymbol{\nu }|{\boldsymbol{P}},{\boldsymbol{z}})$

and the

![]() $f({\boldsymbol{U}}|\boldsymbol{\mu },\boldsymbol{\tau },{\boldsymbol{z}})$

are exactly the same as the ones shown in the complete likelihood in Eq. (6). Furthermore, similar to the

$f({\boldsymbol{U}}|\boldsymbol{\mu },\boldsymbol{\tau },{\boldsymbol{z}})$

are exactly the same as the ones shown in the complete likelihood in Eq. (6). Furthermore, similar to the

![]() $f({\boldsymbol{Y}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })$

, the

$f({\boldsymbol{Y}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })$

, the

![]() $f({\boldsymbol{X}}|{\boldsymbol{Y}}, \beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })$

above can be obtained based on its sampling process in Eq. (3). The combination of the

$f({\boldsymbol{X}}|{\boldsymbol{Y}}, \beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })$

above can be obtained based on its sampling process in Eq. (3). The combination of the

![]() $f({\boldsymbol{Y}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })$

and the

$f({\boldsymbol{Y}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })$

and the

![]() $f({\boldsymbol{X}}|{\boldsymbol{Y}}, \beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })$

in Eq. (13) is equivalent to the

$f({\boldsymbol{X}}|{\boldsymbol{Y}}, \beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })$

in Eq. (13) is equivalent to the

![]() $f({\boldsymbol{X}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}})$

which reads as follows:

$f({\boldsymbol{X}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}})$

which reads as follows:

\begin{align*}f({\boldsymbol{X}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}})&=\prod ^N_{i,j\,:\,i \neq j}f_{\text{Pois}}(x_{ij}|\text{exp}(\beta -||{\boldsymbol{u}}_i-{\boldsymbol{u}}_j||)). \end{align*}

\begin{align*}f({\boldsymbol{X}}|\beta , {\boldsymbol{U}})&=\prod ^N_{i,j\,:\,i \neq j}f_{\text{Pois}}(x_{ij}|\text{exp}(\beta -||{\boldsymbol{u}}_i-{\boldsymbol{u}}_j||)). \end{align*}

However, in our context, not all the real networks that we work on provide exogenous node attributes. In the case that

![]() ${\boldsymbol{c}}$

is not available, the unsupervised prior

${\boldsymbol{c}}$

is not available, the unsupervised prior

![]() $f({\boldsymbol{z}})$

from Eq. (8) is instead proposed in Eq. (13) to replace the

$f({\boldsymbol{z}})$

from Eq. (8) is instead proposed in Eq. (13) to replace the

![]() $f({\boldsymbol{z}}|{\boldsymbol{c}})$

.

$f({\boldsymbol{z}}|{\boldsymbol{c}})$

.

We leverage conjugate prior distributions to marginalize a number of model parameters from the posterior distribution in (13). This methodology is also known as “collapsing” and has already been exploited in, for example, McDaid et al. (Reference McDaid, Murphy, Friel and Hurley2012); Wyse and Friel (Reference Wyse and Friel2012); Ryan et al. (Reference Ryan, Wyse and Friel2017); Rastelli et al. (Reference Rastelli, Latouche and Friel2018); Legramanti et al. (Reference Legramanti, Rigon, Durante and Dunson2022); Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Durante and Friel2025). By proposing the conjugate prior distributions:

where

![]() $(\alpha _1,\alpha _2,\omega )$

are hyperparameters to be specified a priori, the collapsed posterior distribution of the ZIP-LPCM is obtained as:

$(\alpha _1,\alpha _2,\omega )$

are hyperparameters to be specified a priori, the collapsed posterior distribution of the ZIP-LPCM is obtained as:

where the

![]() $f({\boldsymbol{U}}|{\boldsymbol{z}})$

is calculated according to the methodology explored in Ryan et al. (Reference Ryan, Wyse and Friel2017):

$f({\boldsymbol{U}}|{\boldsymbol{z}})$

is calculated according to the methodology explored in Ryan et al. (Reference Ryan, Wyse and Friel2017):

\begin{align} f({\boldsymbol{U}}|{\boldsymbol{z}}) = \prod ^{K}_{k=1} \!\left \{\frac {\alpha _2^{\alpha _1}}{\Gamma (\alpha _1)}\frac {\Gamma \big(\alpha _1+\frac {d}{2}n_k\big)}{\pi ^{\frac {d}{2}n_k}}\left (\frac {\omega }{\omega +n_k}\right )^{\frac {d}{2}}\!\left [\alpha _2-\frac {{\left \|{\sum _{i\,:\,z_i=k}{\boldsymbol{u}}_i}\right \|}^2}{n_k+\omega }+\!\!\sum _{i\,:\,z_i=k}\left \|{{\boldsymbol{u}}_i}\right \|^2\right ]^{-(\frac {d}{2}n_k+\alpha _1)}\right \}\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} f({\boldsymbol{U}}|{\boldsymbol{z}}) = \prod ^{K}_{k=1} \!\left \{\frac {\alpha _2^{\alpha _1}}{\Gamma (\alpha _1)}\frac {\Gamma \big(\alpha _1+\frac {d}{2}n_k\big)}{\pi ^{\frac {d}{2}n_k}}\left (\frac {\omega }{\omega +n_k}\right )^{\frac {d}{2}}\!\left [\alpha _2-\frac {{\left \|{\sum _{i\,:\,z_i=k}{\boldsymbol{u}}_i}\right \|}^2}{n_k+\omega }+\!\!\sum _{i\,:\,z_i=k}\left \|{{\boldsymbol{u}}_i}\right \|^2\right ]^{-(\frac {d}{2}n_k+\alpha _1)}\right \}\!. \end{align}

Now that we have our target collapsed posterior distribution, we apply a partially collapsed Markov chain Monte Carlo approach (Van Dyk and Park, Reference Van Dyk and Park2008; Park and Van Dyk, Reference Park and Van Dyk2009) aiming to infer the latent clustering

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}$

, the latent indicators of unusual zeros

${\boldsymbol{z}}$

, the latent indicators of unusual zeros

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }$

, the intercept

$\boldsymbol{\nu }$

, the intercept

![]() $\beta$

and the latent positions

$\beta$

and the latent positions

![]() ${\boldsymbol{U}}$

from the posterior in Eq. (16). This is accomplished by constructing a sampler which consists of multiple steps for each of the target variables and parameters, and for the number of occupied groups

${\boldsymbol{U}}$

from the posterior in Eq. (16). This is accomplished by constructing a sampler which consists of multiple steps for each of the target variables and parameters, and for the number of occupied groups

![]() $K$

simultaneously. The sampling of the imputed adjacency matrix

$K$

simultaneously. The sampling of the imputed adjacency matrix

![]() ${\boldsymbol{X}}$

straightforwardly follows from Eq. (3), and we leverage ideas similar to those in Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Durante and Friel2025) to infer

${\boldsymbol{X}}$

straightforwardly follows from Eq. (3), and we leverage ideas similar to those in Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Durante and Friel2025) to infer

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }$

and

$\boldsymbol{\nu }$

and

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}$

. Another layer of conjugacy is proposed for the inference procedure of the probability of unusual zeros

${\boldsymbol{z}}$

. Another layer of conjugacy is proposed for the inference procedure of the probability of unusual zeros

![]() ${\boldsymbol{P}}$

that is required by the sampling step of

${\boldsymbol{P}}$

that is required by the sampling step of

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }$

, and we further develop a new TAE move tailored for the clustering without empty groups to facilitate the clustering inference. The sampling of

$\boldsymbol{\nu }$

, and we further develop a new TAE move tailored for the clustering without empty groups to facilitate the clustering inference. The sampling of

![]() ${\boldsymbol{U}}$

and

${\boldsymbol{U}}$

and

![]() $\beta$

are performed via two standard Metropolis-Hastings steps. More details of all these sampling steps are carefully discussed and provided next.

$\beta$

are performed via two standard Metropolis-Hastings steps. More details of all these sampling steps are carefully discussed and provided next.

3.1.1 Inference for

$\boldsymbol\nu$

$\boldsymbol\nu$

Recall that each of the latent indicators of unusual zeros

![]() $\{\nu _{ij}\}$

is assumed to follow the

$\{\nu _{ij}\}$

is assumed to follow the

![]() $\text{Bern}(p_{z_iz_j})$

distribution. However, note that each

$\text{Bern}(p_{z_iz_j})$

distribution. However, note that each

![]() $\nu _{ij}$

must be zero by assumption when the corresponding observed

$\nu _{ij}$

must be zero by assumption when the corresponding observed

![]() $y_{ij}\gt 0$

, so only those

$y_{ij}\gt 0$

, so only those

![]() $\{\nu _{ij}\,:\,y_{ij}=0\}$

are required to be inferred during the inference. Conditional on that the observed interaction

$\{\nu _{ij}\,:\,y_{ij}=0\}$

are required to be inferred during the inference. Conditional on that the observed interaction

![]() $y_{ij}$

is a zero interaction, the probability of such an interaction being an unusual zero is:

$y_{ij}$

is a zero interaction, the probability of such an interaction being an unusual zero is:

and, on the contrary, the conditional probability of it not being an unusual zero is

![]() $\text{P}(\nu _{ij}=0|y_{ij}=0,p_{z_iz_j},\beta ,{\boldsymbol{u}}_i,{\boldsymbol{u}}_j)=1-\text{P}(\nu _{ij}=1|y_{ij}=0,p_{z_iz_j},\beta ,{\boldsymbol{u}}_i,{\boldsymbol{u}}_j)$

. This motivates the sampling of each

$\text{P}(\nu _{ij}=0|y_{ij}=0,p_{z_iz_j},\beta ,{\boldsymbol{u}}_i,{\boldsymbol{u}}_j)=1-\text{P}(\nu _{ij}=1|y_{ij}=0,p_{z_iz_j},\beta ,{\boldsymbol{u}}_i,{\boldsymbol{u}}_j)$

. This motivates the sampling of each

![]() $\nu _{ij}$

to follow:

$\nu _{ij}$

to follow:

\begin{align} \nu _{ij}|y_{ij},p_{z_iz_j},\beta ,{\boldsymbol{u}}_i,{\boldsymbol{u}}_j &\sim \begin{cases} \text{Bern}\left (\dfrac {p_{z_iz_j}}{p_{z_iz_j}+(1-p_{z_iz_j})f_{\text{Pois}}(0|\text{exp}(\beta -||{\boldsymbol{u}}_i-{\boldsymbol{u}}_j||)}\right ), & \text{if}\;y_{ij}=0; \\[12pt] \unicode {x1D7D9}(\nu _{ij}=1), & \text{if}\; y_{ij} \gt 0. \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} \nu _{ij}|y_{ij},p_{z_iz_j},\beta ,{\boldsymbol{u}}_i,{\boldsymbol{u}}_j &\sim \begin{cases} \text{Bern}\left (\dfrac {p_{z_iz_j}}{p_{z_iz_j}+(1-p_{z_iz_j})f_{\text{Pois}}(0|\text{exp}(\beta -||{\boldsymbol{u}}_i-{\boldsymbol{u}}_j||)}\right ), & \text{if}\;y_{ij}=0; \\[12pt] \unicode {x1D7D9}(\nu _{ij}=1), & \text{if}\; y_{ij} \gt 0. \end{cases} \end{align}

This distribution is actually the full-conditional distribution of

![]() $\nu _{ij}$

under the posterior:

$\nu _{ij}$

under the posterior:

which further marginalizes the augmented missing data imputed elements from Eq. (16), that is, collapsing the

![]() $f({\boldsymbol{X}}|{\boldsymbol{Y}}, \beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })$

therein. The sampling in Eq. (19) requires the inference of the probability of unusual zeros defined for the interactions between and within those occupied groups. This can be accomplished by further proposing the conjugate prior distributions:

$f({\boldsymbol{X}}|{\boldsymbol{Y}}, \beta , {\boldsymbol{U}},\boldsymbol{\nu })$

therein. The sampling in Eq. (19) requires the inference of the probability of unusual zeros defined for the interactions between and within those occupied groups. This can be accomplished by further proposing the conjugate prior distributions:

leading to a typical Gibbs sampling step for each non-redundant probability of unusual zeros:

where

![]() $(\beta _1,\beta _2)$

are hyperparameters, and

$(\beta _1,\beta _2)$

are hyperparameters, and

![]() $n_{gh} \, :\!= \, \sum _{i,j\,:\,i\neq j}^N\unicode {x1D7D9}(z_i=g, z_j=h)$

. The notation

$n_{gh} \, :\!= \, \sum _{i,j\,:\,i\neq j}^N\unicode {x1D7D9}(z_i=g, z_j=h)$

. The notation

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }_{gh}$

denotes the sum of all the

$\boldsymbol{\nu }_{gh}$

denotes the sum of all the

![]() $\nu _{ij}|z_i=g, z_j=h, i \neq j$

. Note that the conditional probability of unusual zero provided that the corresponding observed interaction is a zero interaction shown in Eq. (18) is of key interest for practitioners to explore when observing a zero interaction. We refer to Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Durante and Friel2025) for a detailed discussion of the

$\nu _{ij}|z_i=g, z_j=h, i \neq j$

. Note that the conditional probability of unusual zero provided that the corresponding observed interaction is a zero interaction shown in Eq. (18) is of key interest for practitioners to explore when observing a zero interaction. We refer to Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Durante and Friel2025) for a detailed discussion of the

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }$

sampling in Eq. (19).

$\boldsymbol{\nu }$

sampling in Eq. (19).

3.1.2 Inference for

$\boldsymbol{z}$

$\boldsymbol{z}$

Carrying out inference for the clustering variable

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}$

based on the supervised MFM prior in Eq. (12) simultaneously infers the clustering allocations and automatically chooses the number of groups. However, the dimension of the model parameter matrix

${\boldsymbol{z}}$

based on the supervised MFM prior in Eq. (12) simultaneously infers the clustering allocations and automatically chooses the number of groups. However, the dimension of the model parameter matrix

![]() ${\boldsymbol{P}}$

becomes problematic when the nodes are proposed to be assigned to a new empty group. Thus, following the prior distribution introduced in Eq. (21), we can marginalize the target posterior in Eq. (16) in a different way compared to the posterior in Eq. (20). Here, we collapse the parameter

${\boldsymbol{P}}$

becomes problematic when the nodes are proposed to be assigned to a new empty group. Thus, following the prior distribution introduced in Eq. (21), we can marginalize the target posterior in Eq. (16) in a different way compared to the posterior in Eq. (20). Here, we collapse the parameter

![]() ${\boldsymbol{P}}$

from Eq. (16) following, for example, McDaid et al. (Reference McDaid, Murphy, Friel and Hurley2012); Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Durante and Friel2025), and this leads to a posterior:

${\boldsymbol{P}}$

from Eq. (16) following, for example, McDaid et al. (Reference McDaid, Murphy, Friel and Hurley2012); Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Durante and Friel2025), and this leads to a posterior:

where the collapsed likelihood function

![]() $f(\boldsymbol{\nu }|{\boldsymbol{z}})$

reads as follows:

$f(\boldsymbol{\nu }|{\boldsymbol{z}})$

reads as follows:

\begin{align} f(\boldsymbol{\nu }|{\boldsymbol{z}}) &= \prod ^{K}_{g=1,h=1}\left [\frac {\text{B}\left (\boldsymbol{\nu }_{gh} + \beta _1,n_{gh}-\boldsymbol{\nu }_{gh}+\beta _2\right )}{\text{B}(\beta _1,\beta _2)}\right ]. \end{align}

\begin{align} f(\boldsymbol{\nu }|{\boldsymbol{z}}) &= \prod ^{K}_{g=1,h=1}\left [\frac {\text{B}\left (\boldsymbol{\nu }_{gh} + \beta _1,n_{gh}-\boldsymbol{\nu }_{gh}+\beta _2\right )}{\text{B}(\beta _1,\beta _2)}\right ]. \end{align}

Here, B(

![]() $\cdot ,\cdot$

) is the beta function. The sampling of each

$\cdot ,\cdot$

) is the beta function. The sampling of each

![]() $z_i$

is based on the normalized probability proportional to its full-conditional distribution of the posterior in Eq. (23) (Legramanti et al., Reference Legramanti, Rigon, Durante and Dunson2022), that is,

$z_i$

is based on the normalized probability proportional to its full-conditional distribution of the posterior in Eq. (23) (Legramanti et al., Reference Legramanti, Rigon, Durante and Dunson2022), that is,

where the notation

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}^{-i} \, :\!= \, {\boldsymbol{z}}\backslash \{z_i\}$

contains all the clustering indicators except

${\boldsymbol{z}}^{-i} \, :\!= \, {\boldsymbol{z}}\backslash \{z_i\}$

contains all the clustering indicators except

![]() $z_i$

, and the

$z_i$

, and the

![]() $\text{P}(z_i = k|{\boldsymbol{c}}, {\boldsymbol{z}}^{-i})$

follows the supervised MFM urn scheme in Eq. (12) by assuming that the node

$\text{P}(z_i = k|{\boldsymbol{c}}, {\boldsymbol{z}}^{-i})$

follows the supervised MFM urn scheme in Eq. (12) by assuming that the node

![]() $i$

is removed from the network and then is treated as a new node to be assigned a group in the network. More specifically, we have

$i$

is removed from the network and then is treated as a new node to be assigned a group in the network. More specifically, we have

\begin{align} \text{P}(z_i = k|{\boldsymbol{c}}, {\boldsymbol{z}}^{-i}) \propto \begin{cases} \dfrac {n^{-i}_{k,c_i}+\omega _{c_i}}{n^{-i}_k+\omega _0} \big(n^{-i}_k+\alpha \big), & \text{for}\; k=1,2,\dots ,K^{-i}; \\[14pt] \dfrac {\omega _{c_i}}{\omega _0}\dfrac {\mathcal{W}_{N^{-i}+1,K^{-i}+1}}{\mathcal{W}_{N^{-i}+1,K^{-i}}}\alpha & \text{for}\; k = K^{-i}+1, \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} \text{P}(z_i = k|{\boldsymbol{c}}, {\boldsymbol{z}}^{-i}) \propto \begin{cases} \dfrac {n^{-i}_{k,c_i}+\omega _{c_i}}{n^{-i}_k+\omega _0} \big(n^{-i}_k+\alpha \big), & \text{for}\; k=1,2,\dots ,K^{-i}; \\[14pt] \dfrac {\omega _{c_i}}{\omega _0}\dfrac {\mathcal{W}_{N^{-i}+1,K^{-i}+1}}{\mathcal{W}_{N^{-i}+1,K^{-i}}}\alpha & \text{for}\; k = K^{-i}+1, \end{cases} \end{align}

where

![]() $(\! \cdot \!)^{-i}$

denotes the corresponding statistics obtained after removing node

$(\! \cdot \!)^{-i}$

denotes the corresponding statistics obtained after removing node

![]() $i$

from the network. If removing node

$i$

from the network. If removing node

![]() $i$

makes one of the groups empty, the remaining non-empty groups in

$i$

makes one of the groups empty, the remaining non-empty groups in

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}^{-i}$

should be relabeled in ascending order by letting

${\boldsymbol{z}}^{-i}$

should be relabeled in ascending order by letting

![]() $z_j=z_j-1$

for all the

$z_j=z_j-1$

for all the

![]() $\{z_j\,:\,j=1,2,\dots ,N;\, j\neq i;\, z_j\gt z_i\}$

during the inference procedures. If

$\{z_j\,:\,j=1,2,\dots ,N;\, j\neq i;\, z_j\gt z_i\}$

during the inference procedures. If

![]() ${\boldsymbol{c}}$

is not available, the

${\boldsymbol{c}}$

is not available, the

![]() $\text{P}(z_i = k|{\boldsymbol{c}}, {\boldsymbol{z}}^{-i})$

should be replaced with the

$\text{P}(z_i = k|{\boldsymbol{c}}, {\boldsymbol{z}}^{-i})$

should be replaced with the

![]() $\text{P}(z_i = k|{\boldsymbol{z}}^{-i})$

which instead follows the unsupervised MFM urn scheme in Eq. (9), that is, the specific form can be obtained by removing the

$\text{P}(z_i = k|{\boldsymbol{z}}^{-i})$

which instead follows the unsupervised MFM urn scheme in Eq. (9), that is, the specific form can be obtained by removing the

![]() $(n^{-i}_{k,c_i}+\omega _{c_i})/(n^{-i}_k+\omega _0)$

and the

$(n^{-i}_{k,c_i}+\omega _{c_i})/(n^{-i}_k+\omega _0)$

and the

![]() $\omega _{c_i}/\omega _0$

terms in Eq. (26). We refer to Miller and Harrison (Reference Miller and Harrison2018), Geng et al. (Reference Geng, Bhattacharya and Pati2019), Legramanti et al. (Reference Legramanti, Rigon, Durante and Dunson2022), Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Durante and Friel2025) for more details of the inference procedure of

$\omega _{c_i}/\omega _0$

terms in Eq. (26). We refer to Miller and Harrison (Reference Miller and Harrison2018), Geng et al. (Reference Geng, Bhattacharya and Pati2019), Legramanti et al. (Reference Legramanti, Rigon, Durante and Dunson2022), Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Durante and Friel2025) for more details of the inference procedure of

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}$

.

${\boldsymbol{z}}$

.

3.2 Truncated absorb-eject move

Since the latent clustering variable

![]() ${\boldsymbol{z}}$

is updated one element at a time based on Eq. (25), the inference algorithm is susceptible to getting stuck in local posterior modes. Thus, we propose to leverage an Absorb-Eject (AE) move proposed by Nobile and Fearnside (Reference Nobile and Fearnside2007) to facilitate the clustering inference and to deal with such a sampling issue. However, the AE move, as suggested by Nobile and Fearnside (Reference Nobile and Fearnside2007), may create empty groups, and this does not work well with our method, which requires non-empty groups. Thus we instead propose a TAE move which specifically addresses this issue by no longer creating empty groups, as we describe more in detail here below.

${\boldsymbol{z}}$

is updated one element at a time based on Eq. (25), the inference algorithm is susceptible to getting stuck in local posterior modes. Thus, we propose to leverage an Absorb-Eject (AE) move proposed by Nobile and Fearnside (Reference Nobile and Fearnside2007) to facilitate the clustering inference and to deal with such a sampling issue. However, the AE move, as suggested by Nobile and Fearnside (Reference Nobile and Fearnside2007), may create empty groups, and this does not work well with our method, which requires non-empty groups. Thus we instead propose a TAE move which specifically addresses this issue by no longer creating empty groups, as we describe more in detail here below.

Similar to a typical AE move, we have two reversible moves in each iteration of the inference algorithm: a truncated

![]() $eject$

move, denoted as

$eject$

move, denoted as

![]() $eject^T$

, and an

$eject^T$

, and an

![]() $absorb$

move. In general, with probability

$absorb$

move. In general, with probability

![]() $\text{P}(eject^T)$

, the

$\text{P}(eject^T)$

, the

![]() $eject^T$

move is applied and, with probability

$eject^T$

move is applied and, with probability

![]() $1-\text{P}(eject^T)$

, the

$1-\text{P}(eject^T)$

, the

![]() $absorb$

move is applied. As an exception, the

$absorb$

move is applied. As an exception, the

![]() $eject^T$

move is applied with probability

$eject^T$

move is applied with probability

![]() $1$

if

$1$

if

![]() $K=1$

, while the

$K=1$

, while the

![]() $absorb$

move is applied with probability

$absorb$

move is applied with probability

![]() $1$

when

$1$

when

![]() $K=N$

.

$K=N$

.

-

•

$Eject^T$

move: first randomly pick one of the

$Eject^T$

move: first randomly pick one of the

$K$

non-empty groups, say group

$K$

non-empty groups, say group

$g$

. Then, we sample an ejection probability from a prior distribution,

$g$

. Then, we sample an ejection probability from a prior distribution,

$p_e\sim \text{Beta}(a,a)$

, and each node in group

$p_e\sim \text{Beta}(a,a)$

, and each node in group

$g$

has probability

$g$

has probability

$p_e$

to be reallocated to the new group labeled as

$p_e$

to be reallocated to the new group labeled as

$K+1$

. Thus, on the contrary, each node stays in group

$K+1$

. Thus, on the contrary, each node stays in group

$g$

with probability

$g$

with probability

$1-p_e$

. The proposed state is denoted as

$1-p_e$

. The proposed state is denoted as

$({\boldsymbol{z}}',K'=K+1)$

after the reallocation. If this process creates an empty group, that is, either the proposed group

$({\boldsymbol{z}}',K'=K+1)$

after the reallocation. If this process creates an empty group, that is, either the proposed group

$g$

or the proposed group

$g$

or the proposed group

$K+1$

in

$K+1$

in

${\boldsymbol{z}}'$

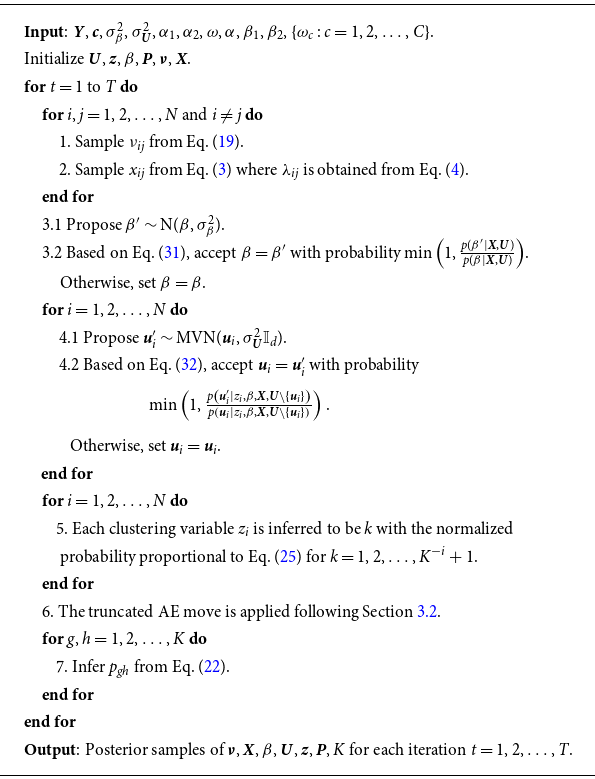

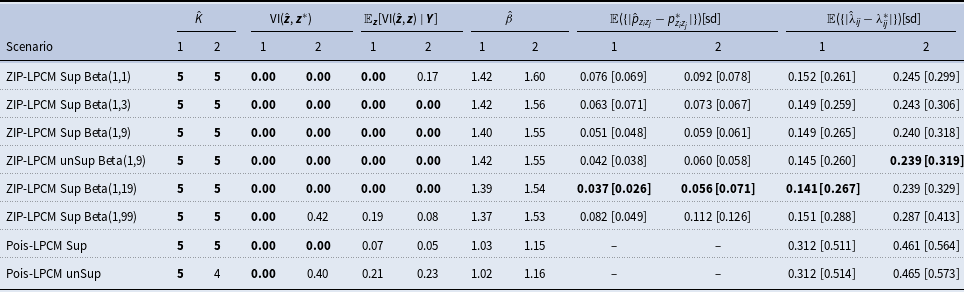

is an empty group, we propose to abandon this truncated AE move and remains at the current state,