Introduction

This article seeks to shed light on why it is that democratically elected representatives are typically much better off than the citizens they represent. Unequal responsiveness to the concerns and preferences of different income groups or social classes has recently become an important topic in comparative politics (e.g. Schakel et al., Reference Schakel, Burgoon and Hakhverdian2020) as well as American politics (e.g. Bartels, Reference Bartels2008; Gilens, Reference Gilens2012). By virtually any measure of socio‐economic status, US congressmen and congresswomen are vastly better off than most American citizens (Carnes, Reference Carnes2013). The United States may be an extreme case, but comparative studies show that descriptive misrepresentation by income and class is pervasive in contemporary democracies (Best, Reference Best2007; Carnes & Lupu, Reference Carnes and Lupu2015; Norris, Reference Norris1997).

While electoral competition and party discipline surely constrain the effect of the social background of legislators on legislative outputs, it is well established that female and minority legislators often play the role of group representatives in legislative voting and, above, agenda setting.Footnote 1 If ascriptive characteristics such as gender and race affect legislators' attitudes and behaviour, why not social class? Carnes' (Reference Carnes2013) pioneering study provides extensive evidence that US legislators with backgrounds in business or white‐collar professions have significantly more conservative attitudes and voting records than legislators who held working‐class occupations before they were elected (see also Griffin & Anewalt‐Remsburg, Reference Griffin and Anewalt‐Remsburg2013; Grumbach, Reference Grumbach2015). Extending this research agenda to Latin America, Carnes and Lupu (Reference Carnes and Lupu2015) demonstrate, with data for 18 countries, that middle‐class legislators consistently have more conservative attitudes on economic issues than working‐class legislators and, with data for Argentina, that middle‐class legislators are more likely to co‐sponsor bills that are economically conservative. In a similar vein, Hemingway (Reference Hemingway2022) shows that prior occupation matters for the policy preferences of legislators across 14 European countries and that legislators from working‐class backgrounds are more likely to have ongoing contacts with trade unions than other legislators. Most convincingly, O'Grady (Reference O'Grady2019) distinguishes between ‘careerist’ and ‘working‐class’ British Labour MPs and shows that parliamentary speeches by the former were significantly more supportive of welfare reforms proposed by the Blair government in 1994–2007 than speeches by the latter and that the former were also less likely to join backbench rebellions against the Blair government.Footnote 2

The importance to be assigned to descriptive representation relative to other factors that might explain unequal responsiveness – e.g. unequal turnout or the role of lobbying – remains an open question, but there can be little doubt that descriptive representation by social class does matter to agenda setting and policy outcomes. Indeed, we are not aware of any recent study that finds that occupational background has no effect on the attitudes and behaviour of legislators.Footnote 3 This then motivates us to contribute to the nascent literature on what might account for the over‐representation of businessmen and, above all, middle‐class professionals in the legislative assemblies of contemporary democracies.

A simple explanation of the over‐representation of businessmen and professionals would be that citizens prefer to be represented by well‐to‐do individuals. It seems reasonable to suppose that many citizens interpret income and wealth as signs of competence and that they believe that wealth renders politicians independent of special interests (Steen, Reference Steen2006). While Arnesen et al. (Reference Arnesen, Duell, Johannesson and Peters2019) present experimental evidence suggesting that low‐income citizens prefer candidates that have higher socio‐economic status than they themselves have, most experimental studies to date challenge this line of reasoning. Carnes and Lupu (Reference Carnes and Lupu2016) report on the results of a survey experiment fielded in Argentina, Britain, and the United States, presenting respondents with a choice between a ‘business owner’ and a ‘factory worker’ as candidates for local political office. In all three countries, respondents were indifferent between the two candidates on offer. Campbell and Cowley (Reference Campbell and Cowley2014a) in turn report that, for parliamentary candidates described as either a self‐made businessman or an employee of an international finance company, British respondents prefer candidates with an average rather than a high income. For the United States, Sadin (Reference Sadin2016) also reports a bias against affluent candidates relative to candidates with twice the median household income. As argued most forcefully by Carnes and Lupu (Reference Carnes and Lupu2016), these results suggest that descriptive misrepresentation has to do with the supply of candidates for elected office – the kinds of individuals who aspire to elected office and are selected by parties – rather than voter preferences in favour of candidates with high‐status occupations and high incomes.

In what follows, we present the results of a conjoint survey experiment in which Swiss citizens were asked to choose among parliamentary candidates distinguished by occupation, education and income. We seek to go beyond the aforementioned studies by taking into account the effects of all three of these characteristics. In addition, and more importantly, we explore the effects of ‘social class’ understood as a combination of occupation, education and income. The setup of our experiment allows us to estimate respondent preferences between candidates with the following class profiles: (1) a routine working‐class candidate with low income, (2) a skilled working‐class candidate with average income, (3) a lower middle‐class candidate with average income and (4) an upper middle‐class candidate earning three times the average income. To anticipate, our results indicate that Swiss citizens are biased against upper middle‐class candidates but also against routine working‐class candidates. While the bias against upper middle‐class candidates is primarily a bias among working‐class respondents, the bias against routine working‐class candidates is more pronounced among middle‐class respondents.

Akin to Carnes and Lupu (Reference Carnes and Lupu2016), our experiment explored potential mechanisms behind preferences for different candidates by asking survey respondents to rate candidates on competence and ability to understand the concerns of ‘people like myself’. According to our results, skilled working‐class, lower middle‐class and upper middle‐class candidates all enjoy a ‘competence bonus’ relative to routine working‐class candidates while upper middle‐class candidates suffer an ‘understanding penalty’ relative to skilled working‐class and lower middle‐class candidates.

It has recently become commonplace to argue that scholars doing experimental research should make more of an effort to replicate their results with real‐world data. In this spirit, we will also present an analysis of the success rate of candidates with different class profiles, based on observational data for the 2007 Swiss parliamentary election. Controlling for list placement and other characteristics, we find that routine working‐class candidates are less likely to be elected than skilled working‐class and lower middle‐class candidates, but upper middle‐class candidates are just as likely to be electorally successful as candidates with the class profiles that our experiment identifies as the most preferred by Swiss citizens.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

Canonical models of voting are distinguished from one another by the emphasis they place on party identification (the Michigan model), the policy positions of voters and candidates or parties (spatial voting) and the performance of incumbents (retrospective voting). None of these models feature candidate characteristics as an important parameter, but an extensive empirical literature demonstrates that voters commonly evaluate party leaders and candidates for public office in terms of competence and empathy – listening to voters and responding to their concerns – and that such evaluations influence vote choices (e.g. Funk, Reference Funk1996, Reference Funk1999; Stewart & Clarke, Reference Stewart and Clarke1992). The comparative literature on this topic suggests that sociodemographic characteristics as well as traits that candidates might strategically project are most salient to voters in countries with single‐member district (SMD) electoral systems (see Aarts et al., Reference Aarts, Blais and Schmitt2013; King, Reference King2002). More importantly for our present purposes, a number of recent studies suggest the salience of candidate characteristics is also conditioned by partisan polarization (Buttice & Stone, Reference Buttice and Stone2012; Green & Hobolt, Reference Green and Hobolt2008; Stone & Simas, Reference Stone and Simas2010). Simply put, voters appear to be more likely to base their vote choice on candidate characteristics when they find it difficult to differentiate among candidates based on policy positions.

In seeking to link the literature on voter evaluations of candidates in terms of competence and empathy to the literature on descriptive (mis)representation by social class, we draw on insights from social psychology. More specifically, we build on the work of Susan Fiske and collaborators, which teaches us that people evaluate individuals and groups along two primary dimensions: competence and warmth (Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002, Reference Fiske, Cuddy and Glick2007). In the words of Fiske et al. (Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002, p. 879),

[w]hen people meet others as individuals or group members, they want to know what the other's goals will be vis‐à‐vis the self or in‐group and how effectively the other will pursue those goals. […] perceivers want to know the other's intent (positive or negative) and capability; these characteristics correspond to perceptions of warmth and competence, respectively.

Structural features of interpersonal and intergroup relations determine perceptions of warmth and competence. Individuals and groups are perceived as relatively warm to the extent that their goals are compatible with those of the perceiver and as relatively cold to the extent that their goals are incompatible or competing with those of the perceiver. On the other hand, individuals and groups are perceived as more competent to the extent that they are powerful and have high socio‐economic status.

Experiments presented in Fiske et al. (Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002) show that Americans consistently perceive middle‐class individuals as warmer than blue‐collar workers as well as the poor and that they perceive blue‐collar workers as warmer than the rich. On the other hand, the rich are perceived as more competent than middle‐class individuals and the latter as more competent than blue‐collar workers, let alone the poor. In keeping with existing literature in political science, we will here use ‘empathy’ rather than ‘warmth’ as the label for the ‘other quality’ that voters are looking for in their representatives, but we consider empathy and warmth to be equivalent. For our purposes, the important implication of the findings reported by Fiske and her collaborators is that efforts by candidates for public office to convince voters that they are competent and empathetic are constrained by their class identity.

The class categories deployed by Fiske and her collaborators are broad and arguably specific to the cultural context of the United States. We seek to integrate the core insights of these authors with a conceptualization of social class that is more fine grained and relies on objective criteria. In so doing, we also seek to advance the growing literature on the politics of inequality and unequal political representation. While contributors to this literature frequently refer to social classes, it is fair to say, we think, that they use the concept of class in a rather casual manner and rarely explain how they conceive the class structure of contemporary capitalist societies. Class and relative income are often conflated as citizens are sorted into equal‐sized income groups. Carnes and Lupu (Reference Carnes and Lupu2015, Reference Carnes and Lupu2016) argue persuasively for an occupational approach to social class, but their approach also leaves something to be desired to the extent that it treats the white‐collar/blue‐collar distinction as the fundamental class divide in contemporary societies. The category ‘white‐collar’ encompasses school teachers as well as investment bankers, and it is far from obvious that individuals in these two occupations would recognize themselves – or be recognized by others – as members of the same social class. If all current or former teachers holding elected office were replaced by investment bankers, the percentage of elected officials from white‐collar backgrounds would be the same, but we would all agree that descriptive representation had changed in a meaningful way.Footnote 4 Similarly, it seems plausible to suppose that occupational distinctions among ‘workers’ matter. Carnes and Lupu's (Reference Carnes and Lupu2016) finding that survey respondents are indifferent between a ‘factory worker’ and a ‘business owner’ running for public office is certainly interesting and pertinent, but it does not follow that voter preferences have nothing to do with descriptive misrepresentation by social class. It could still be the case, for example, that voters prefer a well‐paid lawyer over a poorly paid janitor or sales clerk.

Building on occupational class schemas developed in sociology (Erikson & Goldthorpe, Reference Erikson and Goldthorpe1992; Oesch, Reference Oesch2006b), we propose to distinguish two large classes in contemporary capitalist societies, the working class and the middle class, and then to disaggregate each class into two segments: the routine working class and the skilled working class, on the one hand, and the lower middle class and the upper middle class, on the other hand. The middle class, as we conceive it, encompasses self‐employed professionals, but the vast majority of people who belong to the middle class work for corporations or public authorities. Importantly, the class schema that we have in mind does not distinguish between employees in production and services: the class composition of employment in these sectors differs, but there are workers as well as middle‐class employees in both sectors. Fundamentally, the middle class is distinguished from the working class by educational credentials, opportunities for upward advancement through internal promotion and external labour markets as well as income and savings. As each of these characteristics represents a continuum, the case for class analysis hinges on the proposition that the characteristics are combined in ways that generate (cumulative) discontinuities in the distribution of skills, income and opportunities.

As illustrated by Oesch (Reference Oesch2006b), fine‐grained occupational categories can be used to distinguish between lower and upper segments of the working class as well as the middle class. We propose instead to draw these distinctions based on education and income, on the premise that they cut through many occupations, as conventionally understood. Concretely, we want to distinguish between a cashier in the local supermarket and someone who sells customized luxury products (both ‘salespersons') and, similarly, between a lawyer with her own practice and a partner in a corporate law firm (both ‘lawyers').

To clarify further, it should be noted that our class schema includes two classes that do not feature in the design of our survey experiment: the upper class and the ‘petite bourgeoisie’ (farmers and other small business owners). With substantial income‐generating wealth as the boundary between the middle class and the upper class, the upper middle class extends well into the 10th decile of the income distribution. On the other hand, the skilled working class and the lower middle class overlap in the middle of the income distribution.Footnote 5

Mindful that skilled workers are commonly perceived, and perceive themselves, as part of the ‘middle class,’ we derive the following expectations from the social psychology literature on group‐based perceptions of warmth and competence. First, we expect that candidates from the skilled working class and the lower middle class are, on average, perceived as more empathetic than candidates from the routine working class, who in turn are perceived as more empathetic than candidates from the upper middle class. Second, we expect that candidates from the upper middle class are perceived as more competent than candidates from the lower middle class and the skilled working class and that the latter are perceived as more competent than candidates from the routine working class. Combining these expectations leads us to our first hypothesis about citizen preferences for candidates with different class profiles:Footnote 6

Hypothesis 1. On average, citizens prefer skilled working‐class and lower middle‐class candidates over routine working‐class and upper middle‐class candidates.

If Hypothesis 1 is true and all citizens are equally likely to vote, we would expect skilled working‐class and lower middle‐class candidates to be more likely to be elected to parliament than routine working‐class and upper middle‐class candidates. However, we know that less affluent, less educated, and working‐class citizens are less likely to participate in elections (e.g. Franko et al., Reference Franko, Kelly and Witko2016; Leighley & Nagler, Reference Leighley and Nagler2014). One plausible explanation of why upper middle‐class candidates are successful in elections is that middle‐class citizens, who are more likely to vote than working‐class citizens, are not biased against such candidates relative to candidates from the skilled working class or the lower middle class. As Fiske et al. (Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002) emphasize, the extent to which an individual perceives other individuals (or groups) as warm depends on how compatible their goals are. Middle‐class citizens might have goals that overlap with the goals of upper middle‐class candidates. Sharing similar educational backgrounds, they might also rate upper middle‐class candidates higher on competence than less educated working‐class citizens do. As a consequence, middle‐class citizens’ overall evaluation of upper middle‐class candidates might be similar to their evaluation of skilled working‐class and lower middle‐class candidates. Our second hypothesis follows from this reasoning:

Hypothesis 2: Middle‐class citizens are not biased against upper middle‐class candidates relative to skilled working‐class and lower middle‐class candidates.

Yet another explanation of why upper middle‐class candidates do well in elections is that parties – or, more generally, ‘selectors’ – favour them in the candidate nomination process (Carnes & Lupu, Reference Carnes and Lupu2016). This explanation is plausible so long as voters' bias against upper middle‐class candidates is not strong enough to make them vote for a competing party that fields candidates with more attractive class profiles. As suggested above, the effects of candidate characteristics on vote choice may be small relative to those of party identification and policy preferences, but they will likely become more important in contexts characterized by low party polarization, that is, when party labels are less informative and competing candidates share similar policy positions. We shall return to this question.

The Swiss case

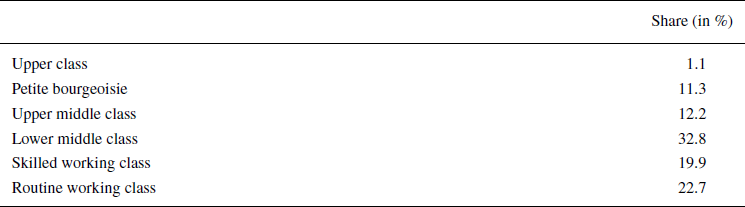

Some background information about the Swiss case is in order before we present our conjoint experiment. To begin with, Table 1 presents estimates of the distribution of the economically active population by social class, based on Oesch's (Reference Oesch2006a) analysis of the Swiss Household Panel Survey of 1999. For this purpose, we assign Oesch's ‘higher‐grade managers’ and ‘self‐employed professionals’ to the upper middle class and equate the upper class with ‘large employers’.

Table 1. The class composition of the economically active population in Switzerland, 1999

Note: Adapted from Oesch (Reference Oesch2006a, p. 273).

Comparing available data on the occupational background of members of parliament with Oesch's (Reference Oesch2006a) data suggests that descriptive misrepresentation by social class is quite pronounced in the Swiss case. Most strikingly, Pilotti (Reference Pilotti2015) reports that nearly one third of the members of the Swiss parliament were lawyers or entrepreneurs in 2000 and 2010, while large employers and the upper middle class together account for only 13% of the economically active population. Pilotti (Reference Pilotti2015) also reports that the majority of Swiss MPs have a university degree while university graduates constitute about 28% of the Swiss population as a whole.Footnote 7

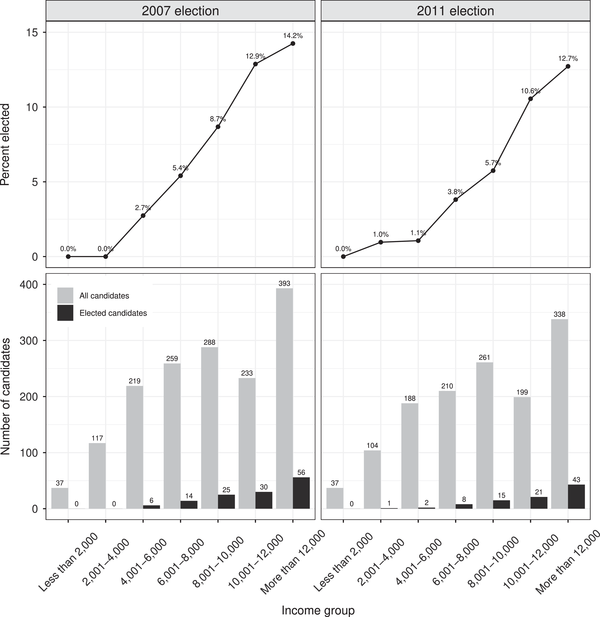

Based on candidate surveys for the 2007 and 2011 elections to the Swiss parliament (FORS, 2009a, 2012a), Figure 1 shows the total number of candidates and the number of successful candidates by income group. Median gross monthly household income for the Swiss population as a whole was somewhat below CHF 8000 in 2006–2008 and somewhat above CHF 8000 in 2009–2011 (CHF = Swiss francs).Footnote 8 The figure shows that most successful candidates had a substantially higher income than the median household, but this is not true for the population of all candidates. Of the 2883 candidates who reported their income in the 2007 and 2011 candidate surveys, 59.4% reported incomes higher than CHF 8000. Of 221 successful candidates, 86.0% reported incomes higher than CHF 8000. In the Swiss case, then, descriptive misrepresentation appears to emerge primarily in the election phase rather than the candidate selection phase. For our purposes, it is particularly noteworthy that low‐income candidates very rarely succeed.Footnote 9

Descriptive misrepresentation by income is not nearly as pronounced in Switzerland as in the United States. Applying Hout's (Reference Hout2004) formula for dealing with open‐ended top income categories to the candidate survey data, and assigning candidates to the midpoint of their income category, we estimate that the average household income of successful candidates to the Swiss parliament was 1.6 times as large as the average Swiss household income in both 2007 and 2011.Footnote 10 We have not been able to come up with a similar estimate for members of the US Congress, but their congressional salary alone was 2.2 times as large as the gross income of the average US household in 2015, and most members of Congress receive ‘outside income’ far in excess of their congressional salary (Carnes, Reference Carnes2013, Reference Carnes2016).

Candidates to the lower chamber of the Swiss parliament (National Council) are elected in a system of proportional representation with open party lists.Footnote 11 Parties can favour some candidates over others by placing them higher on their list of candidates. They can also ‘pre‐cumulate’ candidates, that is, putting them twice on a list, so that these candidates can receive two votes from the same voter (each candidate can receive at most two votes from a single voter). The higher success rate of affluent candidates shown in Figure 1 might be due to bias in party lists, that is, a bias in favour of affluent candidates on the part of parties rather than voters. It should also be noted, however, that citizens who vote for a particular list can express their preferences over candidates by removing candidates from that list, by adding candidates from other lists, and by cumulating candidates that are not yet twice on the list. According to Lutz (Reference Lutz2011, p. 167), 54% of voters exercised some form of preferential voting in the 2007 election.Footnote 12 Finally, it should be noted that campaign financing is primarily party based in Switzerland and, as a result, personal economic resources are unlikely to provide affluent candidates with a big advantage. If voters clearly prefer less affluent candidates, parties should have little incentive to rank more affluent candidates higher or pre‐cumulate them more often.

Experimental design

Our online conjoint survey experiment presented respondents with hypothetical candidates to the National Council. Along with other candidate attributes, we varied three attributes related to social class: occupation, education and income. Hypothetical candidates could be retail salespersons, engineers, lawyers or executives of an international company and could have one of four levels of educational achievement: basic vocational education certificate, higher vocational education certificate, master's degree, or Ph.D.Footnote 13 Referring to gross monthly salary, the income attribute could take one of three values: CHF 5000, CHF 10,000 or CHF 30,000. For reference, it might be noted that the median salary was CHF 6502 in 2016 according to the Federal Statistical Office. It seems likely, we think, that our respondents considered CHF 10,000 to be an average salary.

The other candidate attributes included in our experiment were selected based on the literature that identifies candidates' ideology or policy preferences, political experience, gender, and local roots as important for voters (e.g. Cowley, Reference Cowley2013; Campbell & Cowley, Reference Campbell and Cowley2014b; Shugart et al., Reference Shugart, Valdini and Suominen2005). Providing respondents with information about these attributes enables us to compare the effects of class‐related attributes to the effects of other candidate characteristics and also allows us to control for potential confounding of the effects of social class (Dafoe et al., Reference Dafoe, Zhang and Caughey2018).

In summary, the candidate profiles in our experiment were composed of the following eight attributes: occupation, education, gross monthly salary before entering parliament, political party, political ideology, previous experience in the National Council, gender and residence. For each attribute, a value was randomly drawn from a set of possible values, but we imposed a number of randomization restrictions to exclude candidate profiles that would appear highly unrealistic or impossible.Footnote 14 First, retail salespersons were only paired with basic vocational and higher vocational education while engineers, lawyers, and business executives were only paired with master's and Ph.D. degrees. Second, retail salespersons were only allowed to earn a monthly salary of either CHF 5000 or CHF 10,000 while business executives were only allowed to earn either CHF 10,000 or CHF 30,000. Finally, candidates of the Social Democratic Party (SPS) were restricted to left‐wing or center‐left ideological positions, candidates of the Christian Democratic People's Party (CVP) to center‐left or centrist positions, candidates of the Liberal Democratic Party (FDP) to centrist or center‐right positions and candidates of the Swiss People's Party (SVP) to center‐right or right‐wing positions.

It is important to keep in mind that, in real‐world elections, voters do not necessarily possess all the information about candidates that our experimental design provides. Based on ballots and campaign materials, voters can be expected to know the age, gender, occupation and party affiliation of candidates. News media frequently provide additional information, but the extent to which voters seek and have access to such information obviously varies a great deal (by locality, election context, candidates and voters). As in any experimental study of this kind, we are essentially asking, ‘how would voters respond if they possessed the information provided in the experiment?'

The experiment was fielded in May 2017 to a sample of over 4500 Swiss citizens between 18 and 79 years of age.Footnote 15 We presented each respondent with two pairs of hypothetical candidates.Footnote 16 Following each pair, we asked the respondent multiple questions about his or her voting intentions. First, we asked which candidate the respondent would choose if he or she had to vote for one of the two candidates (‘forced choice'). Second, we asked how likely the respondent would be to vote for each candidate in an election to the National Council (‘vote propensity'). These questions were followed by questions designed to capture respondents’ perceptions of candidates’ competence and empathy. For each candidate, we asked respondents to evaluate how qualified the candidate would be to serve as a member of parliament and how likely the candidate would be to understand the problems facing people like themselves.Footnote 17

Results

Before testing the hypotheses articulated above, we present the marginal means (MMs) of individual candidate attributes on respondents’ vote intentions. For reasons of space, we confine our presentation to results based on respondents' propensity to vote for candidates. Presented in the SI, the results based on forced vote choice are very similar. We prefer vote propensity over forced vote choice for two reasons: first, vote propensity provides more finely grained information about respondents' preferences; and, second, the vote propensity design resembles voter decision‐making in an open‐list proportional representation (PR) system more closely than the forced‐choice design (since such a system allows respondents to express their preference for more than one candidate).

Following Hainmueller et al. (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014) and Leeper et al. (Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020), we use the candidate profile as the unit of analysis and estimate an ordinary least‐squares regression of vote propensity on dichotomous indicator variables for the attribute levels to obtain the MM of each level.Footnote 18 We cluster standard errors by respondent because each respondent evaluated multiple candidate profiles. Also note that we have rescaled vote propensity to range from 0 (very unlikely to vote for a candidate) to 1 (very likely to vote for a candidate), so that the MM of an attribute level shows the average likelihood that a respondent will vote for a candidate on a 0–1 scale, and that we have dropped all respondents who answered ‘don't know’ to the vote propensity question.

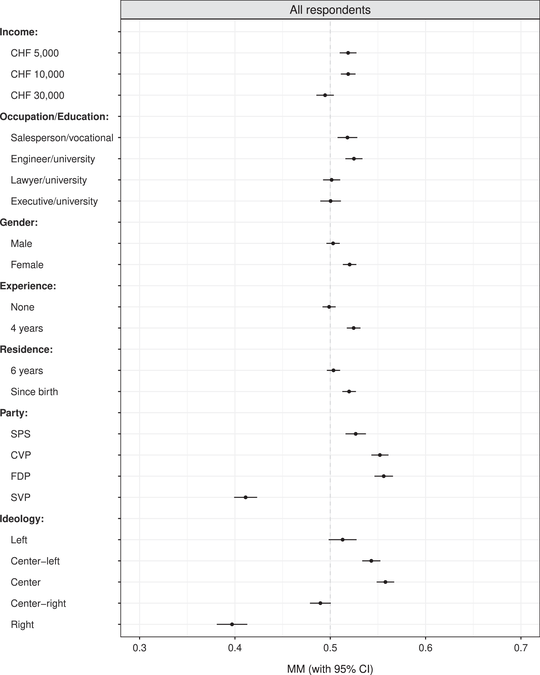

Figure 2 shows aggregate results – point estimates and 95% confidence intervals – for all respondents.Footnote 19 On average, respondents favour candidates earning CHF 10,000 over candidates earning CHF 30,000, and they tend to be indifferent between candidates earning CHF 10,000 and those earning CHF 5000. Relative to average‐income candidates, there is a clear bias against high‐income candidates, but not against low‐income candidates. Turning to the candidates' occupation and education, we find that respondents favour salespersons with basic or higher level vocational education over lawyers and business executives with master's or Ph.D. degrees, but they are indifferent between salespersons with vocational training and engineers with university education.Footnote 20 The effects of a candidate having an average rather than a high income and a candidate being a salesperson with vocational training rather than a university‐educated lawyer or executive manager are similar in magnitude to the effects of attributes that have been shown to be important to voters in previous literature. Specifically, having an average income (relative to a high income) or being a salesperson with vocational training (relative to a lawyer or executive manager with university education) provides about the same advantage in terms of respondents' support as 4 years of previous experience in the National Council (relative to having no such experience) and at least as great an advantage as having lived since birth in the respondent's canton (relative to having lived there for 6 years).Footnote 21

Figure 2. MMs of candidate attributes on vote propensity.

To test our hypotheses about the effects of social class, we identify four ideal‐typical class profiles based on the class schema outlined above: a routine working‐class (RWC) candidate, a skilled working‐class (SWC) candidate, a lower middle‐class (LMC) candidate, and an upper middle‐class (UMC) candidate. The RWC candidate and the SWC candidate are both salespersons, but they have different levels of education and income: the former has basic vocational training and a monthly salary of CHF 5000, and the latter has higher vocational training and a salary of CHF 10,000. Likewise, the LMC candidate and the UMC candidate both have middle‐class occupations, the former is an engineer and the latter is a lawyer, but they differ with respect to education and income: the former has a master's degree and a salary of CHF 10,000 and the latter has a Ph.D. and a salary of CHF 30,000.Footnote 22

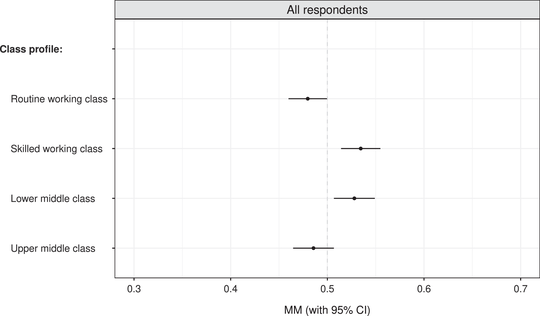

Figure 3 shows the average propensity of respondents to vote for the RWC candidate, the SWC candidate, the LMC candidate, and the UMC candidate, respectively. The results support our first hypothesis. On average, respondents clearly prefer both the SWC candidate and the LMC candidate to the RWC candidate. They also prefer the SWC and LMC candidates to the UMC candidate. Respondents seem to have a slight preference for the UMC candidate over the RWC candidate, but this effect is not statistically significant.Footnote 23

Figure 3. MMs of candidates' social class on vote propensity.

There are undoubtedly some Swiss MPs from SWC backgrounds and a fair number from LMC backgrounds, but, as we have seen, more affluent, UMC candidates also fare quite well in Swiss elections. This may be because of unequal electoral turnout. Our second hypothesis posits that middle‐class citizens, who are more likely to vote than working‐class citizens, are not biased against UMC candidates relative to SWC and LMC candidates. To test this hypothesis, Figure 4 replicates Figure 3 with respondents split into working‐class respondents (shown in gray colour) and middle‐class respondents (shown in black colour).Footnote 24 Since we are only able to distinguish between working‐class and middle‐class occupations for a subset of respondents, we here proxy respondents' social class by education and household income. Specifically, we operationalize ‘working‐class respondents’ as respondents with secondary education or less and below‐median household income (![]() $\le$ CHF 8000) and ‘middle‐class respondents’ as respondents with tertiary education and above‐median household income.Footnote 25 When we include occupation along with education and household income as a criterion for distinguishing between working‐class and middle‐class respondents, we obtain point estimates that are almost identical to those shown in Figure 4, but the confidence intervals are much larger, due to the smaller sample size.Footnote 26

$\le$ CHF 8000) and ‘middle‐class respondents’ as respondents with tertiary education and above‐median household income.Footnote 25 When we include occupation along with education and household income as a criterion for distinguishing between working‐class and middle‐class respondents, we obtain point estimates that are almost identical to those shown in Figure 4, but the confidence intervals are much larger, due to the smaller sample size.Footnote 26

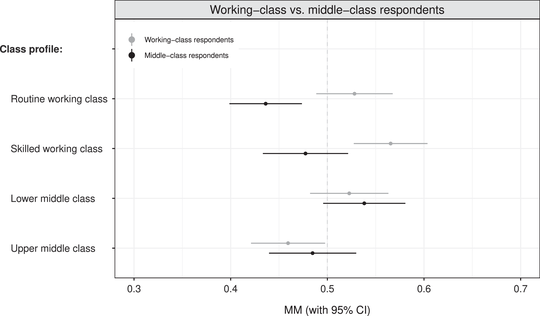

Figure 4. MMs of candidates’ social class on vote propensity by respondents' social class.

The results presented in Figure 4 are straightforward and quite revealing. Though some of the effects fall short of the 95% significance threshold, working‐class respondents and middle‐class respondents alike prefer the SWC class candidate over the RWC candidate and the LMC candidate over the UMC candidate. In all other races, however, the relative preferences of the two types of respondents diverge noticeably or, in other words, the effects of presenting them with pairs of candidate profiles differ. Working‐class respondents prefer the RWC candidate as well as the SWC candidate over the UMC candidate, while they are indifferent between the RWC candidate and the LMC candidate. By contrast, middle‐class respondents prefer the LMC candidate and the UMC candidate over the RWC candidate and they are indifferent between the SWC candidate and the UMC candidate. These results provide at least partial support for our second hypothesis in that middle‐class respondents are not biased against UMC candidates relative to SWC candidates but prefer LMC candidates over UMC candidates.

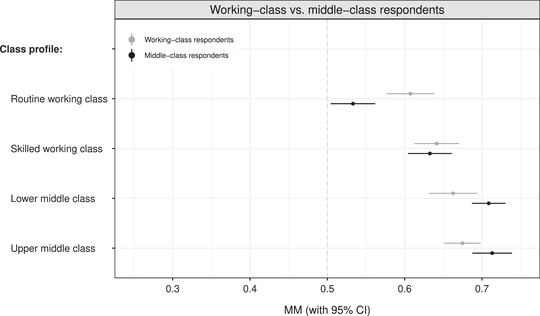

Addressing the reasoning behind respondents' preferences for candidates with different class profiles, Figure 5 reports on the assessments of candidates' competence made by working‐class and middle‐class respondents while Figure 6 reports on their assessments of candidates' ability to understand the ‘problems facing people like me’.Footnote 27 Assessments of competence differ by socio‐economic status in that middle‐class respondents rate the relative competence of LMC and UMC candidates significantly higher than do working‐class respondents. While middle‐class respondents consider both middle‐class candidates to be more competent than the SWC candidate, working‐class respondents consider the UMC but not the LMC candidate to be more competent than the SWC candidate. At the same time, we find that working‐class respondents as well as middle‐class respondents rate the RWC candidate as less competent than all other candidates.

Figure 5. MMs of candidates' social class on perceived candidate competence by respondents' social class.

Notes: Candidate competence has been rescaled to range from 0 (not at all qualified) to 1 (very qualified).

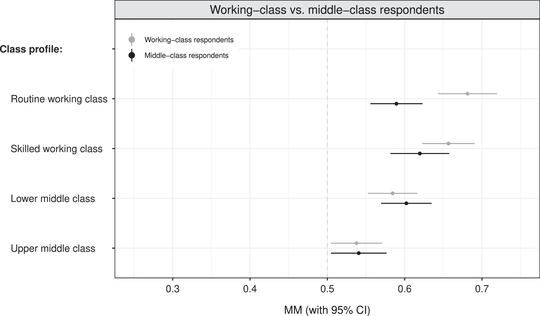

Figure 6. MMs of candidates' social class on perceived candidate empathy by respondents' social class.

Notes: Candidate empathy has been rescaled to range from 0 (very unlikely to understand ‘problems facing people like me') to 1 (very likely to understand them).

The framework developed by Fiske et al. (Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002) treats perceptions of competence as a function of the socio‐economic status of the perceived. The results reported here suggest perceptions of competence vary with the perceiver's own socio‐economic status as well. Quite plausibly, high‐status individuals are more prone to correspondence bias than low‐status individuals, as the conception of a meritocratic world where talent and hard work pay off justifies their own success.

As for assessments of empathy, UMC candidates are deemed to be out‐of‐touch by working‐class and middle‐class respondents alike, although this is more pronounced for the former. Among working‐class respondents, LMC candidates also suffer an ‘understanding penalty’ relative to working‐class candidates. However, middle‐class respondents consider all candidates other than UMC candidates to be more or less the same on this dimension.

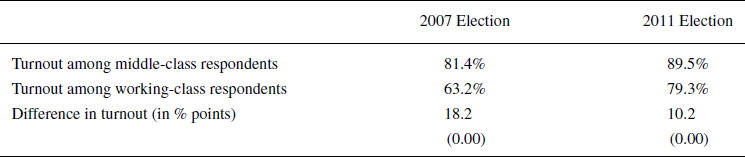

Returning to the implications of electoral turnout, the results presented in Figure 4 suggest that if only middle‐class citizens voted, RWC candidates would be more likely to lose while the other candidates would compete in tight races, with LMC having some advantage over SWC and UMC candidates. Based on data from Swiss national election surveys (FORS, 2009b, 2012b), Table 2 shows our estimates of turnout by social class in the 2007 and 2011 elections to the National Council, with social class again proxied by education and household income. Whether or not the observed class gap is sufficiently large enough to account for the unequal descriptive representation documented above (Figure 1) is a thorny question that we cannot resolve here.Footnote 28

Table 2. Reported turnout in the 2007 and 2011 elections to the national council among middle‐class and working‐class respondents

Note: The numbers in parentheses are the ![]() $p$‐values from (two‐tailed) tests for equality of proportions.

$p$‐values from (two‐tailed) tests for equality of proportions.

Observational data

Seeking to assess the real‐world relevance of our experimental results, we use data on occupation, education and income from the 2007 candidate survey (FORS, 2009a) to code candidates for the National Council as belonging to the routine working class, the skilled working class, the lower middle class or the upper middle class. We then fit a multilevel logistic regression model with candidates nested within party lists, which, in turn, are nested within cantons. Specifically, we regress a binary variable indicating whether candidates were elected to parliament on candidates’ class profiles as well as their gender and age and variables indicating candidates' (normalized) position on their party list and whether candidates had been pre‐cumulated by their party.Footnote 29 Summarizing the results of this exercise, Figure 7 shows box plots of the predicted probability of electoral success by social class, holding candidates' party list position fixed at the middle of the list for the left panel and the top of the list for the right panel while averaging over candidates' sex, age, and pre‐cumulation.

Figure 7. Effect of social class on the electoral success of real‐world candidates.

Simply put, we find that SWC, LMC and UMC candidates are considerably more likely to be elected to office than RWC candidates. Even when the latter candidates are placed at the top of their list, their predicted probability of being elected tends to be lower than the one of SWC, LMC and UMC candidates positioned in the middle of the list. In other words, the observational data confirm the bias against RWC candidates identified by our survey experiment, but not the bias against UMC candidates. Regarding the discrepancy between the experimental and observational findings for UMC candidates, it deserves to be noted that the UMC candidate in our experiment has a very high salary and that this is an important source of the bias against her.Footnote 30 It seems likely that UMC candidates in the real world are, on average, less affluent than the UMC candidate in our experiment. Alternatively, it may be that real‐world UMC candidates are indeed very affluent, but real‐world voters lack the information to recognize them as such. Yet another explanation might be that the greater financial resources of UMC candidates allow them to run more effective election campaigns and thus overcome their class‐profile disadvantage. According to data from the 2007 candidate survey, the average campaign budget was CHF 2230 for RWC candidates, CHF 12,248 for SWC candidates, CHF 16,817 for LMC candidates and CHF 17,327 for UMC candidates. While the average campaign budgets of SWC, LMC and UMC candidates differ significantly from those of RWC candidates, the average budgets of the former three groups of candidates are not significantly different from one another. Based on these data, we cannot conclude that campaign spending explains why there is no real‐world bias against UMC candidates relative to SWC and LMC candidates.

Conclusion

Pooling all respondents, our Swiss survey experiment confirms the bias against high‐income candidates identified, for the UK, by Campbell and Cowley (Reference Campbell and Cowley2014a) and, for the United States, by Sadin (Reference Sadin2016). Going beyond previous studies, our analysis shows that this bias is primarily, if not entirely, a bias held by working‐class citizens. Against the background of unequal turnout, the asymmetric nature of the bias against upper middle‐class candidates renders descriptive misrepresentation less puzzling than it would be if this bias were shared by all citizens. As noted above, however, it remains an open question whether class‐based differences in voter turnout are large enough to explain why upper middle‐class candidates do well in Swiss elections. In addition, and perhaps more important for real‐world politics, our analysis uncovers a bias against routine working‐class candidates that most previous studies have missed. Contrary to Arnesen et al. (Reference Arnesen, Duell, Johannesson and Peters2019), our experimental results indicate that this is first and foremost a bias held by middle‐class citizens, but our analysis of observational data suggests that it is more widely held, or more salient for voting behaviour, than the first bias.

In closing, we want to underscore that our survey experiment assigns ideological positions to candidates and that ideological proximity between respondents and candidates turns out to be a very strong predictor of respondents' propensity to vote for particular candidates. As we show in Section 12 of the SI, candidates' class profiles have an important effect on voters' choice between candidates that are ideologically close to each other, but the importance of class profiles decreases with the ideological distance between candidates. When choosing between a candidate with the most preferred class profile and a candidate with the least preferred class profile, both having ideological positions identical to those of respondents, working‐class and middle‐class respondents alike are more likely to vote for the candidate with the class‐profile advantage. When the candidate with the most preferred class profile has an ideological position that differs moderately from those of respondents while the candidate with the least preferred class profile has an identical position, working‐class and middle‐class respondents are indifferent between the two candidates. Finally, when the candidate with the most preferred class profile has an ideological position that differs strongly from those of respondents while the candidate with the least preferred class profile has an identical position, the effect of ideological proximity dominates the effect of class profile and respondents are substantially more likely to vote for the ideologically identical candidate even though they find that candidate's class profile the least attractive.

Ideological proximity can offset the bias against upper middle‐class candidates, but the same logic should also apply to routine working‐class candidates. While our analysis in this article shows that voters do have preferences among candidates with different class profiles, we do not wish to suggest that these preferences alone explain the descriptive misrepresentation by social class that we observe in the Swiss case, let alone the American case. According to the results of our survey experiment, there must also be unequal electoral participation by social class in order for voter preferences to explain over‐representation of the upper middle class in legislatures. And political parties may be biased in favour of upper middle‐class candidates as well. Indeed, Wüest (Reference Wüest2019) shows that Swiss parties typically place candidates with higher education degrees and more prestigious occupations in more favourable positions on the lists that they present to voters. In future work, we want to explore whether or not this bias is more pronounced for some parties than for others. A reasonable hypothesis emerging from the preceding analysis is that parties with weak ideological profiles – or, alternatively, parties with ideologically close competitors – will be more likely to feature skilled workers and lower middle‐class candidates in prominent positions.

There is no a priori reason to suppose that the biases revealed by our survey experiment are uniquely Swiss. Indeed, survey experiments that we have carried out in Great Britain and the United States reveal the same bias against routine workers as candidates for parliament (the House of Representatives in the US experiment) that we find in the Swiss case. In these experiments, respondents were randomly presented with candidates with jobs corresponding to the four classes identified in the preceding analysis: shop assistant or cleaner as the RWC job, law clerk or paramedic as the SWC job, lawyer with own practice or primary care physician as the LMC job and managing partner of a corporate law firm or cardiologist as the UMC job. British as well as American respondents consistently favoured skilled workers and middle‐class professionals over routine workers.Footnote 31

To the extent that voter preferences for candidates with different class profiles are more or less similar across countries, the relationship between class differences in electoral turnout and descriptive misrepresentation by social class becomes an important topic for comparative inquiry. In future work, we also want to leverage cross‐national variation to test the hypothesis that partisan polarization is associated with descriptive misrepresentation by social class. Opening space for parties (selectors) to field upper middle‐class candidates without losing voters to their competitors, the polarization of American politics over the last 20–30 years (McCarty et al., Reference McCarty, Poole and Rosenthal2006) may have contributed to descriptive misrepresentation by social class.

Finally, a limitation of our experimental design is that it does not allow us to test whether perceived candidate competence and empathy are causal mechanisms underlying the effect of candidates' class profile on respondents' vote intention. Further research is therefore necessary to explore the extent to which perceived competence and empathy mediate the relationship between the social class of candidates and the vote propensity of respondents.

Acknowledgments

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the Conference of the ECPR Standing Group on Parliaments (2017), the Annual General Conference of the European Political Science Association (2017), the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (2017), the Annual Conference of the Swiss Political Science Association (2018), and the Unequal Democracies Seminar at the University of Geneva (2018). A pre‐analysis plan for the survey experiment was presented at a workshop held at the University of Zurich in 2017. In addition to participants at these events, we thank Nathalie Giger, Dominik Hangartner, Enrique Hernández, Simon Hug, Marcello Jenny, Josh Kalla, Simon Lanz, Lucas Leemann, Noam Lupu, Tamaki Ohmura, Jan Rosset and the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions. We would also like to thank Giacomo Benini, Fabio Cappelletti, Fabien Cottier, Federico Ferrara, Julien Jaquet and Jasmine Lorenzini for their help with the translation of the survey and Valentina Holecz, Max Joosten and Jérémie Poltier for the coding of social classes. The survey experiment was financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 100017_166238). The write‐up has also been supported by the European Research Council (grant agreement no. 741538).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table S1: Citizens' Utility Functions

Table S2: Attributes and Possible Values in the Candidate Choice Experiment

Table S3: Distribution of Socio‐Demographic Characteristics

Figure S1: AMCEs of Candidate Attributes on Vote Propensity

Figure S2: MMs of Candidate Attributes on Forced Vote Choice

Figure S3: AMCEs of Candidate Attributes on Forced Vote Choice

Figure S4: MMs of Candidate Attributes on Perceived Candidate Competence

Figure S5: AMCEs of Candidate Attributes on Perceived Candidate Competence

Figure S6: MMs of Candidate Attributes on Perceived Candidate Empathy

Figure S7: AMCEs of Candidate Attributes on Perceived Candidate Empathy

Figure S8: MMs of All Combinations of Candidate Occupation, Education, and Income on Vote Propensity

Figure S9: AMCEs of Candidates' Social Class on Vote Propensity

Figure S10: MMs of Candidates' Social Class on Forced Vote Choice

Figure S11: AMCEs of Candidates' Social Class on Forced Vote Choice

Figure S12: MMs of Candidates' Social Class on Perceived Candidate Competence

Figure S13: AMCEs of Candidates' Social Class on Perceived Candidate Competence

Figure S14: MMs of Candidates' Social Class on Perceived Candidate Empathy

Figure S15: AMCEs of Candidates' Social Class on Perceived Candidate Empathy

Figure S16: AMCEs of Candidates' Social Class on Vote Propensity by Respondents' Social Class

Figure S17: MMs of Candidates' Social Class on Vote Propensity by Respondents' Social Class

Figure S18: AMCEs of Candidates' Social Class on Vote Propensity by Respondents' Social Class

Figure S19: MMs of Candidates' Social Class on Perceived Candidate Competence by Respondents' Social Class

Figure S20: AMCEs of Candidates' Social Class on Perceived Candidate Competence by Respondents' Social Class

Figure S21: MMs of Candidates' Social Class on Perceived Candidate Empathy by Respondents' Social Clas

Figure S22: AMCEs of Candidates' Social Class on Perceived Candidate Empathy by Respondents' Social Clas

Figure S23: MMs of Candidates' Social Class on Vote Propensity by Respondents' Social Class

Figure S24: AMCEs of Candidates' Social Class on Vote Propensity by Respondents' Social Class

Figure S25: MMs of Candidates' Social Class on Perceived Candidate Competence by Respondents' Social Class

Figure S26: AMCEs of Candidates' Social Class on Perceived Candidate Competence by Respondents' Social Class

Figure S27: MMs of Candidates' Social Class on Perceived Candidate Empathy by Respondents' Social Class

Figure S28: AMCEs of Candidates' Social Class on Perceived Candidate Empathy by Respondents' Social Class

Table S4: Class Profiles for Real‐World Candidates and Hypothetical Candidates

Figure S29: AMCEs of Candidates' Social Class on Vote Propensity by Respondents' Social Class in a No‐, Moderate‐, and High‐Polarization Context

Figure S30: AMCEs of Candidates' Social Class on Vote Propensity by Respondents' Social Class in a No‐, Moderate‐, and High‐Polarization Context

Table S5: Attributes and Possible Values in the Candidate Choice Experiments in GB and the US

Figure S31: MMs of Candidates' Social Class on Vote Propensity for All Respondents and by Respondents' Social Class