During the war the theatre has in many ways done its duty to the public. It has contributed its quota to the fighting Services, and some of its most promising recruits will not return. It has taken the lead in all charitable projects. By special performances of every kind it has raised hundreds of thousands of pounds, and no deserving cause has asked its help in vain. Above all, it has carried on its task of entertaining the people, in the face of many hardships and discouragements.

This tribute, published in The Times on 18 November 1918, one week after the Armistice, reveals the central role that British theatre played throughout the First World War, or, as it was known at the time, the Great War. Yet, reflecting on the dramatic output of the period, the article was less commendatory. ‘The war has not stirred the imagination of the British dramatist … the function of the English stage has been, indeed, frankly to entertain’, it asserted, adding that ‘more will be asked from it in the days of peace that are to come.’ Looking ahead and hoping for ‘something more substantial in prospect’, this commentator, like many others at the time, effectively wrote off wartime theatrical output and condemned it to be forgotten by history.

A century later, the legacy of this critical attitude towards drama of the Great War has been profound. The perception that theatre did not deal with the war, combined with the idea that, as entertainment, it lacked any intrinsic value, has resulted, until recently, in the period’s drama being largely ignored and misunderstood: a situation which this Companion seeks to remedy. As a result, in 1993 Michael Woolfe could confidently argue that:

In the theatre at this time … the war seems to have passed across the stage making little impact outside a handful of plays. The history of theatre in this time is curiously untouched by the tragedy of war and its cosmic reverberations, strangely untroubled and persistently faithful to the patterns of the past and the imperatives of commerce.1

Almost fifteen years later, Heinz Kosok began his 2007 The Theatre of War by noting the continuing elision of drama within studies on the literature and fiction of the war. With his ground breaking study of more than 200, largely forgotten, plays about the war, Kosok began the important work of repositioning drama within the wider field of literary and cultural studies of the conflict. As the first critical analysis of war-themed plays during and after the First World War, Kosok’s analysis of structure, thematic content, reception and representation, remains a valuable introduction to the literary features of First World War drama over the last century.

Central to Kosok’s argument is that whether plays about the war are literary masterpieces or not, they are important for the ways in which they ‘reflect attitudes and preoccupations in British culture during or after the war.’2 The idea that drama is an important means of understanding wartime experiences, ideas and concerns is also at the heart of this Companion. In addressing this, the chapters which follow look beyond value judgements about the artistic quality of the dramatic texts and draw on diverse examples of drama and performance, including Shakespeare, revue, melodrama, pantomime, musicals, cinema and dance. With this attention to the popular and lowbrow alongside the classics, the Companion’s contributors implicitly recognise, as Peter Swirski puts it in From Lowbrow to Nobrow, that whilst much popular fiction might be meant to go ‘in one eye and out the other’, at the same time it is, ‘a universal forum for the propagation and stimulation of ideas. It refers to and comments on all aspects of contemporary life, in the end informing, and in some cases even forming, the background of many people’s values and beliefs’.3

Attention to lowbrow and popular art forms has been a feature of cultural studies over recent years. In theatre history, the work of Jackie Bratton, Jim Davis, Katherine Newey, and Janice Norwood, among others, has drawn new attention to the period just prior to the First World War, whilst Adam Ainsworth, Oliver Double and Louise Peacock’s 2017 edited collection, Popular Performance, defined and historicised forms of performance with the primary purpose of entertaining audiences. At the same time, in First World War studies, there has been increasing interest in the cultural outputs of the war, whether literary, musical, artistic, poetic, or screen and cinematic. Responding to this, the work of academics and public volunteers on the Great War Theatre project has revealed, for the first time, the extent of wartime theatre and the dominance of the popular and lowbrow during the war years. Comprehensively mapping all new plays written and licensed for performance during the conflict and recording information on performances and playwrights in the open-access online database at www.greatwartheatre.org.uk, the project has also revealed the longevity of many of the period’s plays in the national repertoire between the wars. Alongside this wider context, between 2014 and 2018 there was a growing interest in wartime theatre and in the use of theatre within commemoration. The wake of the centenary of the conflict therefore offers an apt moment to reflect both on the diversity of theatre produced during the war, and on the afterlife of the war in British theatre over the last century.

The Companion to British Theatre of the First World War responds to and marks this shift in critical, academic and public interest in, and understandings of, British theatre during and about the First World War. In doing so it builds on a small, but important, number of studies on the subject including Kosok’s Theatre of War. Gordon Williams’s British Theatre in the Great War (2003) was the first single-author study of British theatre of the war and rightly identifies the period as ‘one of the most exciting half-decades in British twentieth-century theatre.’4 Whilst Williams pays attention to the diversity of theatre during the period, the predominantly London-centric perspective elides the breadth of theatre being produced across Britain, a limitation that the Companion directly addresses through drawing on examples of regional as well as international theatre practice. Whilst L.J. Collins’s Theatre at War (2004) does explore regional performance – as well as performance at the front – here the focus is largely on the industry’s response to the war through recruitment, fundraising, and camp entertainments. Ten years later, in Andrew Maunder’s collection of essays, British Theatre and the Great War (2015), the valuable insight into the function of theatre in military settings which Collins had opened up, was brought together with new analysis of theatre on the home front. Including contributions from scholars working across English, Drama and History, the collection offered valuable new insights into questions around women’s involvement and representation in theatre, as well as drawing links between performance cultures in Britain, at the front, and in Australia.

Building on some of the areas addressed in these previous studies – most notably mobilisation, theatre in the war zone, cinema, and popular genres – in part, this Companion offers new perspectives on familiar themes: for example, rethinking the established narrative that cinema overtook theatre and instead examining how cinema intersected with, and borrowed practices from, the theatre. At the same time, it goes beyond common themes to address aspects of First World War theatre which are often touched on in passing but rarely receive attention in their own right: topics such as changing practices of theatre-making and theatregoing, and theatrical resistance to the war. It also introduces new areas of analysis, looking at the role that theatre played in centenary commemorations, and also at international theatrical influences and transmission of plays. This exploration of the relationship between British and international theatre has a particularly important place in a volume which is otherwise focussed predominantly on British theatre. Not only does it provide an important reminder of the global context but it also opens the door to future scholarship which might offer comparative and international perspectives on theatre of the period. The more restricted geographic focus is also counterbalanced by the temporal spread of the volume: from before the war to the end of its centenary in 2018. Covering this long period, as well as in considering theatre as both an industry and literary–cultural artform, the Companion aims to be an accessible and informative guide for any student or scholar interested in the intersection of the Great War with theatre and performance culture over the last century.

Overview

The Companion to British Theatre of the First World War has a dual focus: both on the war and on the memory of the war. In addressing this, the volume is divided into three parts – ‘Mobilising for War’; ‘Theatre during the War’; and ‘The Memory of War’. The sections are chronologically ordered but the chapters intersect thematically to offer different perspectives on key topics. For readers interested in attitudes towards the war and pro- or anti-war sentiments, for example, Robert Dean’s examination of mobilisation and the comic revue (Chapter 2) can be productively read alongside Anselm Heinrich’s exploration of theatrical dissent and the representation of objectors to the war (Chapter 11). The theme of resistance is also taken up by Helen E. M. Brooks in her examination of the 1963 production of Oh What a Lovely War (Chapter 13). Similarly, readers interested in questions of gender during the war might find of particular use: Dean’s exploration of gendered ideology in propagandistic and recruiting performances (Chapter 2), Viv Gardner’s examination of female theatregoing (Chapter 5), Rebecca D’Monté’s consideration of interwar sexuality and female playwrighting (Chapter 12), and Rebecca Benzie’s focus on centenary performances inspired by the experiences of women during wartime (Chapter 14).

Part I begins by examining the period in which peace changed to war. In Chapter 1, Ailise Bulfin sets the scene by considering the ways in which dramatic output in the period leading up to the war prefigured and worked through fears over a coming conflict. She points out that from 1900 to 1914 tensions between Western colonial powers and unrest in colonies both gave rise to invasion narratives in literature and in theatre. While the majority of these narratives provided templates for wartime propaganda plays, she also reveals the existence of theatrical sketches that sent up the fear of invasion, suggesting that pre-war audiences were at least somewhat sceptical. In Chapter 2, Robert Dean takes us into the early months of the war, looking at how music hall and revue created support for, and capitalised on, the war effort. Importantly, he points out how music hall performers such as Vesta Tilley and Marie Lloyd incorporated social change around gender relations to send up the propaganda messages that were prevalent in the press and in recruitment drives.

Part II forms the core of the Companion and the chapters here address the theatre produced and staged during the conflict itself. Across these chapters, theatre is placed within the wider social, international and cultural context. Attention is also paid to a range of theatrical genres including revue (Chapter 2), melodrama (Chapter 7) and Shakespeare and the classics (Chapter 6). The hybrid and intertwined nature of the arts is also emphasised: in particular, in Emma Hanna’s examination of drama’s place within the wider musical and entertainment culture at the front and within military contexts (Chapter 5) and in Hammond’s exploration of theatre’s place within a wider leisure context in which cinema was growing fast (Chapter 8).

Claire Cochrane’s analysis of the material conditions of theatre-making during the war (Chapter 3) opens Part II and provides an important framework for the following chapters. Cochrane looks at the financial pressures created by the war for regional theatre managers and shows how managers responded by mixing popular West End touring productions with more highbrow fare. She also reminds us of the importance of understanding the double bind of censorship and governmental regulation which theatre had to operate under. The long-standing Theatres Act of 1843 gave the Lord Chamberlain, Viscount Sandhurst, control over what could and could not be performed on public stages with all plays having to be licensed by the Lord Chamberlain before being publicly performed. With the introduction of the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) in August 1914, however, an additional layer of war-specific censorship was introduced. Not only could DORA be used to ban plays but the regulations introduced impacted directly on theatre-making and theatregoing. Viv Gardner picks up on the theme of theatregoing in Chapter 4 and uses evidence found in diaries and the popular press to offer new insights into the war’s impact on audiences. She focuses on the ‘new’ audiences of servicemen and women – in particular mothers and single women – and argues that the war resulted in a gradual democratisation of theatre audiences. In Chapter 5, Emma Hanna brings the themes of theatre-making and theatregoing together, examining theatre both for and by the armed services. Hanna shows how morale was boosted by professional performers touring the front lines and hospitals, concert parties given by the soldiers themselves, and shows offered by non-governmental organisations such as the YMCA. Whilst attention has previously been paid to performance for and by soldiers, Hanna breaks new ground here in also examining the navy and air force. As such the chapter offers the first analysis of military performance culture as a whole.

Ailsa Grant Ferguson picks up on the theme of performance in military contexts in Chapter 6, where she highlights the unique place of Shakespeare within wartime culture. Shakespeare productions, she argues, not only survived a broader rejection of other classical dramas, but became synonymous with British cultural values. Shakespeare was mediated in this way, she points out, both through the efforts of women who ran productions and through the incorporation of Shakespearean vignettes in variety programmes. From here, Chapter 7 picks up on the theme of the popular stage, with Maggie B. Gale drawing our attention to the way the war was represented across two popular genres: the one-act domestic war play and the spy drama. Gale emphasises how the former drew upon established comic and dramatic traditions while the latter was influenced by nineteenth-century melodrama: in particular, structurally and through the use of sensation scenes.

In Chapter 8, Michael Hammond also looks at transmission of practice, considering the close relationship between theatre and cinema, both in terms of industry practice and output. He points out that newsreels and official war films such as The Battle of the Somme (1916) were important in showing audiences at home something of life at the front. Yet he also recognises that, like theatre, cinema’s most effective role in the war effort was as an entertainment source. Hammond’s discussion of the growth of Hollywood and American domination of the cinema industry is developed in Chapter 9 where Philippa Burt examines anxieties over American ‘invasions’ of the British theatre industry, with a particular focus on the growing popularity of the ‘crook’ play. Burt argues that attitudes towards American drama should be read in light of America’s neutral stance in the war before April 1917, as well as for what they reveal about a sense of threat to national identity. In Chapter 10, Eva Krivanec picks up on the importance of international influences and reminds us that the close interconnectedness between British and European performance in the early twentieth century continued in adapted form into the war. Yet, whilst plays by Belgian and allied writers were welcomed, the work and even theatrical styles of the new enemy were firmly suppressed. The theme of censorship which emerges here is picked up in the final chapter of Part II. In Chapter 11, Anselm Heinrich considers how both formal and informal censorship constrained playwrights with pacifist leanings. Focussing both on how theatre questioned or challenged the war, and on the representation of objectors to the war, Heinrich’s chapter shows that the theatre was not always unquestioningly supportive of the national war effort. Linking to Part III, he also reminds us that attitudes towards the war changed as the conflict wore on.

The chapters in Part III focus on how theatre continued to engage with, reflect and remember the war after it was over and in the context of changing attitudes towards the conflict. In doing so, these chapters build on the body of work examining the war’s cultural legacy which has been produced, in particular, by literary and film and screen studies scholars. Rebecca D’Monté opens Part III with a focus on the theatre immediately following the war and through the interwar period. In Chapter 12 she reveals the range of post-war theatre about the conflict beyond R.C. Sherriff’s well-known play Journey’s End (1928). Considering both dominant themes and dramatic styles D’Monte shows how playwrights sought to tackle the complex legacy of the war. Throughout the interwar period, she argues, plays about the war became more downbeat and bitter, and lay the foundation for the memory of the war as an exercise in futility. In Chapter 13, Helen E. M. Brooks takes up the story after the Second World War, looking at the shift in how the war has been imagined over the last half century. Examining productions of Oh What a Lovely War (1963), Birdsong (2010), Private Peaceful (2004) and War Horse (2007), she shows how the war has been re-imagined on stage through political, educational and commemorative lenses. Linking to the theme of commemoration, in the final chapter of the volume Rebecca Benzie takes stock of the expansion of theatre about the First World War during the centenary of the conflict. She explores varied forms of performance including the British Legion’s installation of ceramic poppies, Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red (2014) at the Tower of London, and the nationwide, we’re ‘ere because we’re ‘ere (2016). In doing so, Benzie shows how these centenary productions built upon and revised the existing palimpsest of memory and narratives of the war.

During the war there had been a sense that the conflict could only be dealt with fully in the theatre, or in other narrative forms, once more distance had been gained from it. ‘The theme is too great for expression’ wrote the Globe in reviewing Stephen Phillips’s 1915 play Armageddon, ‘and only in transitory moments do we get a suggestion of the epic drama which the author has sought to unfold’.5 Similarly, Jules Romains commented in 1938, ‘there was no lack of eyewitnesses, but none of them could get far enough away from the drama to see it as a whole’.6 Yet whilst distance from the war might have created the critical and artistic successes that commentators felt were sorely missing during the conflict, these later works, as the chapters in Part III reveal, are as much a product of their social and cultural context as those produced during the war. Recognition of the integral relationship between theatre and the society in which it is made runs through all the chapters in this Companion. By focussing our attention in this way moreover, the contributors collectively seek both to broaden our understanding of the war itself, and to open up new insights into the cultural outputs which emerged from the conflict.

A Brief History: Theatre during the Great War

The chapters which follow each take a specific aspect of First World War theatre, consolidating, extending, and opening up new research in the field to provide an invaluable guide to theatre of, and about, the conflict. As the theatre of the period remains relatively under-researched when compared to the cinema or literature of the period, or indeed when compared to other periods of theatre history, we begin with a broad contextualisation of wartime theatre, setting the scene for the more in-depth discussion which readers can find in subsequent chapters.

As soon as war began in August 1914, theatre-makers rallied to the national cause, directing their energies towards encouraging enlistment. At the same time, large numbers of theatrical personnel – most prominently actors and musicians – signed up to join the forces. In July 1915, on the eve of the first year of the war, leading theatre actor–manager, Sir Herbert Tree, estimated that out of 8,000 actors of all ages, over 1,500 had already enlisted: a significant proportion considering that the total number of actors included many who would have been ineligible for service due to age or infirmity.7 Absolute numbers of actors and performers who served in the armed forces are impossible to determine since performers would sign up using their ‘private’ rather than their ‘stage’ names. Yet throughout the war, programmes frequently declared that every male member of the company had either served at the front, had attested or was ineligible. In 1917 the Stage also informed readers that prior to conscription’s introduction in January 1916, not only had ‘no class enlisted or attested more freely than actors’, but ‘all actors physically fit for military service have been taken.’8 Whether or not this was true, it served as a valuable protection for actors who were vulnerable to attacks for appearing to shirk their duty.

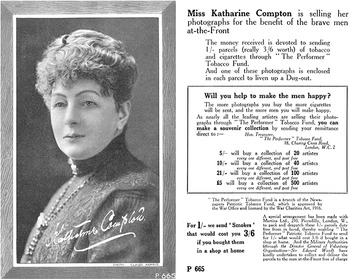

In addition to encouraging enlistment and sending its men to the front, the theatre industry also raised significant amounts of money and supported the various war charities which proliferated over the course of the conflict. Through charity matinees, souvenir sales, theatrical auctions, special concerts and more, the theatre industry raised the equivalent of more than £100 million by the end of the war, supported by the generosity of audiences (Figure 1).9

Figure 1 ‘The Performer’ Tobacco Fund postcard, featuring Miss Katharine Compton.

When we imagine audiences during the Great War, it can be easy to slip into thinking of theatres full of civilians. However, as Viv Gardner points out in Chapter 4, soldiers and servicemen were an active presence in the theatres of wartime Britain. This was especially evident in London, with many servicemen going to the theatre during their short periods of leave. Theatres catered to these military audiences and showed their support for the national war effort by offering discounted tickets to those who came in uniform and, in 1917, the value of this support for men on leave was recognised in a speech by Lord Derby. Servicemen’s leave, Derby declared, should ‘be marked by amusements that will abstract them from all the anxieties and dangers they have undergone, and fit them for further exertion, with renewed vigour.’10 For Derby, entertainment had military value: re-fitting the troops to return to the trenches. A similar point was made by The Times in 1915: when the soldiers ‘are by and by storming another Hill No. _’ the paper announced, ‘they will achieve their task with all the more zest for a lively recollection of MISS ETHEL LEVEY teaching MR GEORGE GRAVES the ‘fox-trot’, or of MISS ELSIE JANIS blithely out-laudering Mr Harry Lauder.’11 The idea that soldiers might be more enthusiastic going over the top having seen a musical whilst on leave might seem questionable, however as Emma Hanna explores in Chapter 5, entertainments were widely recognised as playing an important role in maintaining the morale and fighting spirit of servicemen across the armed forces.

The value of theatre was also recognised when it came to the wounded. Like those on active duty, wounded servicemen were a frequent presence in theatres, and reserved seats and dedicated performances for the wounded were another way in which theatres could support the national war effort and make their own war ‘sacrifice’, as the Yorkshire Evening Post put it describing the ‘sacrifice’ of 700 ‘saleable seats’ to wounded soldiers each week at the Leeds Empire.12 Individual theatre enthusiasts could also make a personal contribution to the war effort by supporting the wounded in accessing entertainment, as we see in the example of B. F. Findon, editor of the theatrical periodical, The Play Pictorial, who used his publication to call for donations to a ‘Wounded Soldiers Matinee Tea Fund’. The funds were used to take wounded soldiers from London’s Endell Street Military Hospital to a matinee followed by high tea and cigarettes. Publicised donations from Mrs Kate Flowers of Mafeking (now Mahikeng) in South Africa, and Mr J.P. Mollison of Yokohama, Japan, are a reminder of the global reach of the war.

Where servicemen were too ill to leave the hospitals in which they were being treated, performers would also go to them, performing in hospital wards, canteens and YMCA huts across the country. In 1917, Lt-Col Bruce Porter, the London hospital commandant, highlighted the value of these hospital entertainments, noting that, ‘in nothing done in the present war has there been better work than the provision of healthy entertainments.’ He continued that, laughing at an amusing show ‘does more good than physic as a tonic and helps to a brighter and more hopeful outlook and consequently more rapid recovery’.13 With patients recovering four-to-five days earlier, entertainments, he even concluded, could be equated to the release of a ward of 260–300 beds.

The idea that entertainment was a ‘military necessity’ because the ‘curing of the wounded was not merely an affair of drugs and dressings’ was also recognised by Neville Chamberlain, who had organised entertainments for the sick as Lord Mayor of Birmingham.14 Yet the ‘partly psychic’ role of entertainment went beyond the war-wounded and also benefitted home front war workers, as well as parents, sweethearts and families anxious over the safety of their loved ones at the front.

Throughout the war theatre played an important role in distracting, amusing, entertaining and re-energising audiences of both servicemen and civilians: a role which led to a dominance of melodramas, revues, farces, light comedies and musical extravaganzas. As the Stage Yearbook reflected in 1916, ‘the public’:

has wanted nothing that will wring its withers – no inspissated gloom, no problems of sex, no polemics, no whips of satire. Its serious thinking is all about the War: and it does not wish to go to the theatres to be ‘perplexed in the extreme’ in either its emotions or its thoughts…the public wants to be taken out of itself.15

This was certainly true, yet as Ailsa Grant Ferguson reminds us in Chapter 6, the wartime dominance of these genres was also shaped by the economy of the theatre industry. Prior to the introduction of arts funding there was no subsidisation for theatre. Much like the commercial sector today, theatres could only survive by putting ‘bums on seats’. And during the war, a period in which the theatre industry faced ‘enormous and unparalleled difficulties’ as the Stage put it on 1 March 1917, attracting audiences was all the more important.

The challenges faced by theatres between 1914 and 1918 are explored by both Claire Cochrane and Viv Gardener in their partner chapters on theatre-making and theatregoing. One of these challenges, for metropolitan theatres in particular, was air raids. Whilst a theatre like the Criterion, which was built underground, could be advertised as, ‘nothing more or less than an admirable little dugout in the centre of Piccadilly Circus’, few other theatres were as well set-up.16 Nevertheless, despite a small number of theatres which chose to close, the majority stayed open and, in some cases, even thrived in the face of adversity. As Gardner explores in Chapter 4, this was partly due to changing audiences and, in particular, growing numbers of women and servicemen on leave going to the theatre. Moreover, this new, more mixed audience was, as Charles B. Cochran commented in 1917, ‘without preconceived ideas as to what a theatrical production should be. It is prepared to find new authors and new players for itself. It is less influenced by the names on the playbill than formerly’.17 As Cochran was clearly aware, audiences shaped the content of the wartime repertoire and were crucial in supporting the theatre industry throughout the conflict.

The popularity of theatre during the war is evident in the number of long-running, hit shows produced between 1914 and 1918, many of which could be seen both in London and on tour, as well as being adapted for film. These include Lechmere Worrall and J.E. Harold Terry’s The Man Who Stayed at Home (1914); The Bing Boys are Here (1916) and its spin-offs The Other Bing Boys (1917), The Bing Girls (1917) and The Bing Boys on Broadway (1918); and Chu Chin Chow (1916) which was seen by over 2.8 million people over five years. So embedded was Chu Chin Chow in the national culture that one of the show’s numbers, ‘The Robber’s March’, was played by the military band when the first British troops marched into Germany in 1918. It is a moment which exemplifies the ways in which theatre provided a bridge between home and fighting fronts throughout the war: something which was also evident in Bruce Bairnsfather and Arthur Eliot’s hit trench musical, The Better ‘Ole (1917) which showed those at home, as one newspaper put it, ‘the daily lives led by our soldiers, a subject about which very few of us possess nay but the very faintest idea’.18

Looking at the most popular shows of the war, the fallacy that entertainment always meant ignoring or distracting audiences from thinking about the conflict becomes immediately apparent. Both The Man Who Stayed at Home and The Better ‘Ole were widely celebrated for thrilling, amusing and entertaining audiences but they did so whilst also directly tackling the context of the war. As a Sheffield review of The Man Who Stayed at Home noted, the play was ‘full of excitement and topical interest’ adding that whilst, ‘one has a natural prejudice against drama dealing with [the war] much before the end of the first act … that prejudice had been dissipated’.19 When looking at the wartime repertoire more broadly, this same dissipation of the prejudice against war-themed drama is equally evident and challenges the long-held narrative that wartime theatre was popular because it distracted audiences from thinking about the war. As researchers on the Great War Theatre project have revealed, in their mapping of all the plays licensed by the Lord Chamberlain’s office during the war, over a quarter of the near 3,000 plays licensed during the war tackled the theme of war directly and did so across a variety of genres. Beyond anxieties over enlisting and dying at the front in recruiting dramas, plays dealt with a range of wartime themes and experiences. These included the changing role of women in society, conscientious objection, loss and bereavement, injury and disability, front-line experiences, shell-shock and more. Whilst most frequently these issues were discussed in ways which were comical, romantic, thrilling, sentimental or musical (often at one and the same time), serious and poetic treatments can also be found, such as J.M. Barrie’s one-act wartime plays The New Word (1915), Charwomen and the War, or The Old Lady Shows her Medals (1917) and A Well-Remembered Voice (1918).

Looking across this body of wartime plays it becomes clear that, however the theme was treated, the war was, if not ubiquitous, certainly a familiar theme within the theatrical repertoire of wartime Britain. And, as the chapters in Part III show, this dramatic exploration of wartime experience continued into the post-war period, with the Great War remaining a recurrent theme in plays through to the end of the centenary. Yet, as the essays in the Companion to British Theatre of the First World War show, it is only by resisting binaries of amateur and professional, low and high, and London and the regions, that we can begin to recognise the diversity of war-themed plays produced in anticipation of, during, and after the Great War. And in turn, it is only by developing this more diverse and nuanced understanding of Great War theatre that we can appreciate the distinctive and multiple ways in which theatre pre-empted and foreshadowed the war in the early part of the century; responded to and mediated experiences of the war between 1914 and 1918; and ultimately how it has become a central feature in remembrance and commemoration of the conflict over the last one hundred years.