Introduction

State formation in Ancient Egypt and the processes that led to it are difficult to conceptualise. Although anthropological and theoretical approaches provide some insight into this pivotal moment in prehistory, our understanding of the events that took place in Upper Egypt during the second half of the fourth millennium BC has not evolved much in recent years. Archaeology provides a considerable amount of data regarding the formation of the Egyptian state, but much derives from documents (decorated and inscribed portable objects, iconographic material, etc.) that were unearthed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and discussions surrounding this complex period need a new impetus (Stevenson Reference Stevenson2016).

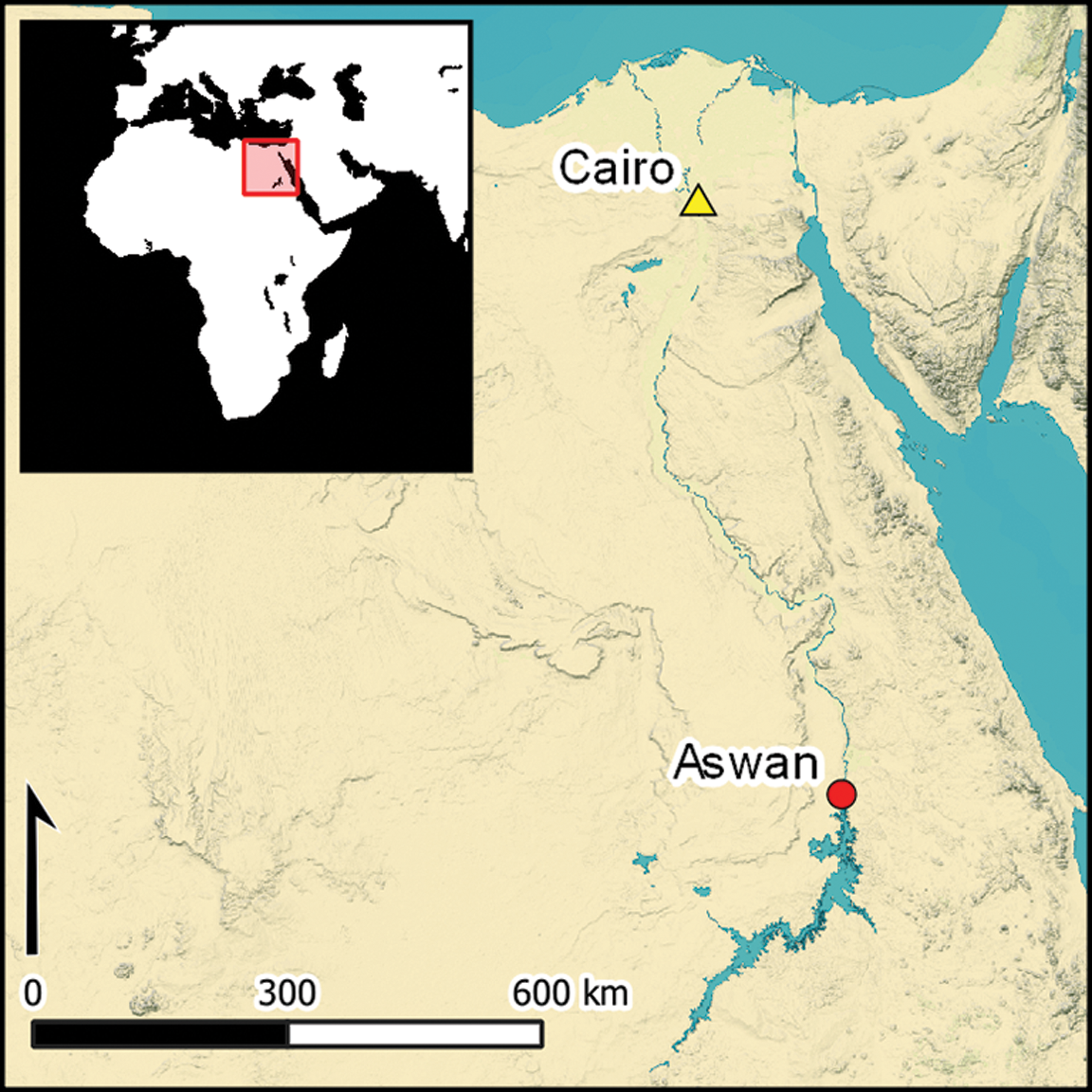

Rock engravings from the Lower Nile Valley have the potential to help explain early forms of political power and how the landscape was exploited to express and consolidate authority (Vanhulle Reference Vanhulle2024). However, the number of relevant examples is limited, and most of them are found in the southern part of Upper Egypt, particularly in the area of Elkab and the border region of Aswan (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map locating the Egyptian sites mentioned in the text (base map © Google Earth, modified by the author).

This article introduces an intriguing new addition to this restricted catalogue and explores its informative potential. Uncovered on the west bank of the Nile at Aswan, the engraving consists of a putative authority representative seated in a processional boat, a scene that is otherwise well attested in Late Predynastic (Naqada IIC–D, c. 3450–3350 BC) and Protodynastic (Naqada IIIA–B, c. 3350–3085 BC) iconography. Stylistic similarities between this decorated rock panel and Protodynastic and early First Dynasty official imagery suggest the existence of rock-art specialists commissioned by regional authorities. Building on this contextual analysis, this article also advocates for the better integration of rock art in discussions focusing on the development of kingship and state formation in Egypt and Lower Nubia.

The sociocultural and historical context

Although debate continues to surround the specifics of processes that ultimately saw the expansion of the cultural complex of Upper Egypt and the birth of the Egyptian state, the grand narrative that Upper Egypt was the core region of the Predynastic (c. 4500–3350 BC) ‘Naqada’ culture is generally accepted. This material culture spread through the entire territory of Egypt and into Lower Nubia during the second half of the fourth millennium BC where it mingled with the Lower Egyptian and A-Group cultures, leading to a ‘cultural unification’ of Lower and Upper Egypt that may have facilitated the political unification achieved in its aftermath (Hendrickx Reference Hendrickx, Shaw and Bloxam2020). This period is characterised by the presence of early forms of polities in both Egypt and Nubia (Moreno Garcia Reference Moreno Garcia2023: 4–8), and the development of writing in Egypt.

The first authority figures in the Egyptian Nile Valley are identified in Upper Egypt and are associated with “centres of power” (Kemp Reference Kemp2018: 70–109). Abydos, Naqada and Hierakonpolis are recognised as the main centres, providing information on the development of politico-religious power in Egypt (Figure 1). Other sites, poorly preserved in comparison, probably played a similar role on a local/regional scale (e.g. Gebelein; Ejsmond Reference Ejsmond, Kabaciński, Chłodnicki, Kobusiewicz and Winiarska-Kabacińska2018). Early forms of power in Egypt were local and regional, sometimes co-operative, but presumably also often in competition. Indeed, violence, both actual and symbolic, can be inferred from Upper Egyptian archaeological and iconographic material (Bestock Reference Bestock2018). ‘Elites’, often depicted as a group of figures capped with feathers and with their arms raised above their heads in Predynastic iconography (Hendrickx & Eyckerman Reference Hendrickx and Eyckerman2012), progressively disappear in favour of depictions of a single character wearing a crown by the Late Predynastic and Protodynastic periods.

Mobile communities and desert groups showing strong ties with southern Nubian regions roamed the deserts and were in regular contact with the politically structured societies in the Nile Valley (Gatto Reference Gatto and Exell2011; Cooper & Vanhulle Reference Cooper and Vanhulle2023). Their role in the sociopolitical processes at play during state formation remains to be evaluated, but it was certainly less marginal than previously thought (Moreno Garcia Reference Moreno Garcia2023: 6, 22).

The role of Lower Nubia in the development of political and religious authority in Upper Egypt and the region of the First Cataract deserves reassessment, as the First Cataract was neither completely dependent on nor independent from the polities developing in what was to become the territory of Ancient Egypt (Török Reference Török2009). The Nubian A-Group is contemporaneous with the Egyptian Predynastic and Protodynastic, during which periods the communities of Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia shared common roots and were in close contact. The A-Group also initiated socio-political processes aimed at complexity and power, though these pathways diverged from those of Upper Egypt, reaching full development at the time of Egyptian unification (c. 3100 BC) but disappearing from the archaeological record shortly afterwards (c. 2900 BC) (Gatto Reference Gatto, Emberling and Williams2020: 125). At least two Protodynastic centres of power are identified at Sayala and Qustul in Lower Nubia (Williams Reference Williams1986).

The Aswan-Kom Ombo region and the First Cataract were inhabited by a population mixing Upper Egyptian and Lower Nubian cultural traits (Gatto Reference Gatto and Raue2019, Reference Gatto, Emberling and Williams2020). Various forms of political and territorial power could, therefore, have emerged at the same time in the Lower Nile Valley, with their evolution shaping the process of state formation in Egypt. It could also be suggested that Lower Nubian polities were less able to control a population that largely remained attached to a nomadic way of life. Differences in pace and form in the structuring of power in Egypt and Nubia could partly explain the outcome, which saw Narmer found the First Dynasty in Egypt c. 3085 BC and the A-Group disappear from the Nubian archaeological record in the subsequent reigns. Pharaonic kingship is the result of a centuries-long process, and its inception was not as straightforward as generally assumed, nor was it restricted territorially or culturally (Manzo Reference Manzo2020).

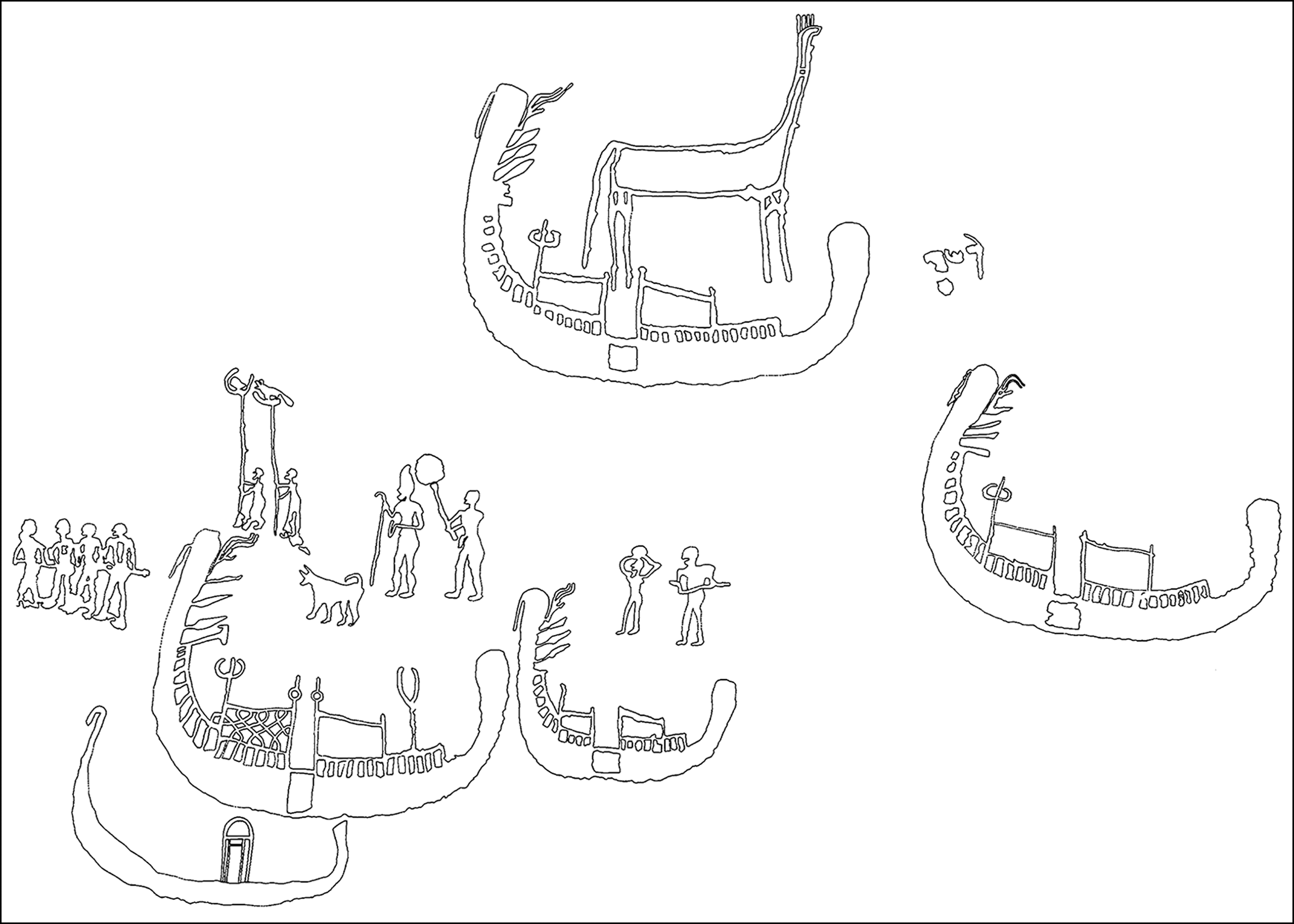

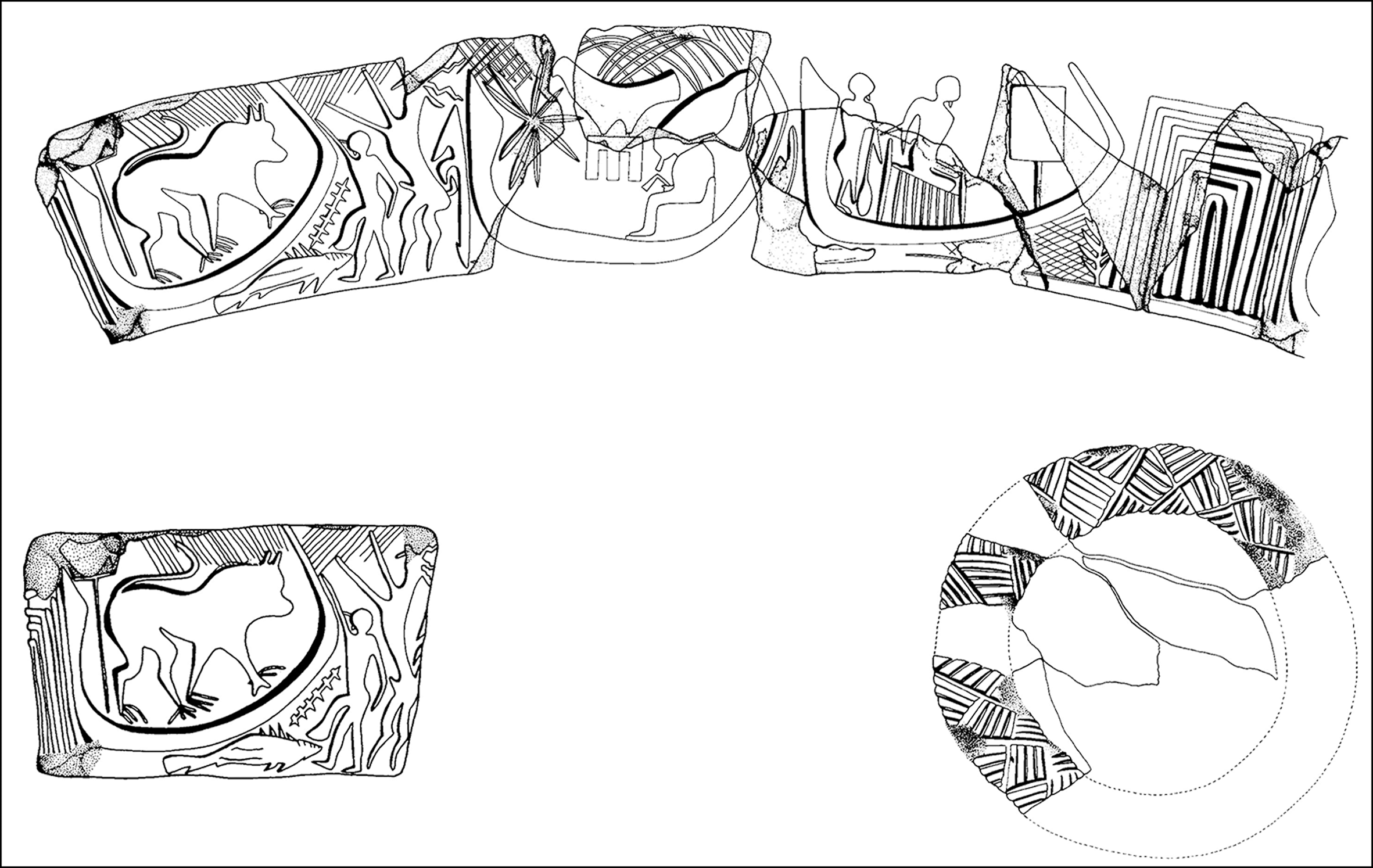

Recent excavations at the site of Nag el-Hamdulab provide a compelling argument for including rock art from the Lower Nile Valley and archaeology from Lower Nubia in contemporary discussions on the formation of the Egyptian state. These excavations were conducted on a plateau overlooking the valley, in the same place where engravings were discovered at seven sites forming part of what is interpreted as a rock art royal cycle (Hendrickx et al. Reference Hendrickx, Darnell, Gatto, Eyckerman, Huyge and Van Notten2012). Compositions consist of naval processions, potential military victories and hunting scenes, and stylistic and technical characteristics indicate that all the drawings were very probably made by the same hand or by the same group of craftsmen. Three sites also offer depictions of a crowned figure, bearing all the characteristic attributes of Egyptian kingship (e.g. the false beard and the Heqa-sceptre), accompanied by their followers/court (Figure 2). Stylistic typologies of the boats and human figures and a small proto-hieroglyphic inscription attribute this rock art to Naqada IIIA–B (Darnell Reference Darnell2015). Excavations further revealed the remains of a funerary structure reminiscent of nomadic structures documented in the Eastern Desert (e.g. Osypiński et al. Reference Osypiński, Osypińska and Zych2021; Gatto et al. Reference Gatto, Nicolini and Curci2022). The artefacts discovered combine Upper Egyptian and Lower Nubian traditions. Thus, this site might be “the resting place of important individuals related to mobile communities” connected with both Nubia and the deserts (Bourgeois et al. Reference Bourgeois, Crépy and Gatto2024). It remains to be confirmed whether the individuals buried there are responsible for some, or all, of the Nag el-Hamdulab rock art, but should this be the case, it would have a profound impact on our current understanding of the Protodynastic period and the development of kingship in Egypt. Indeed, this would question the cultural affiliations of the first Upper Egyptian kings and the role played by Nubian desert communities in the processes that led to state formation. Some 5.5km north of Nag el-Hamdulab, as the crow flies, another rock panel is challenging our understanding of this crucial phase in the history of Egypt.

Figure 2. Drawing of site 7, panel 7a at Nag el-Hamdulab showing a crowned, bearded figure holding a Heqa-sceptre (this ‘shepherd’s crook’ is a traditional attribute of Egyptian kings) and its followers alongside a naval procession (width of panel: 2.9m; after Hendrickx et al. Reference Hendrickx, Darnell, Gatto, Eyckerman, Huyge and Van Notten 2012 : fig. 4; reproduced with the permission of M.C. Gatto).

The context of discovery

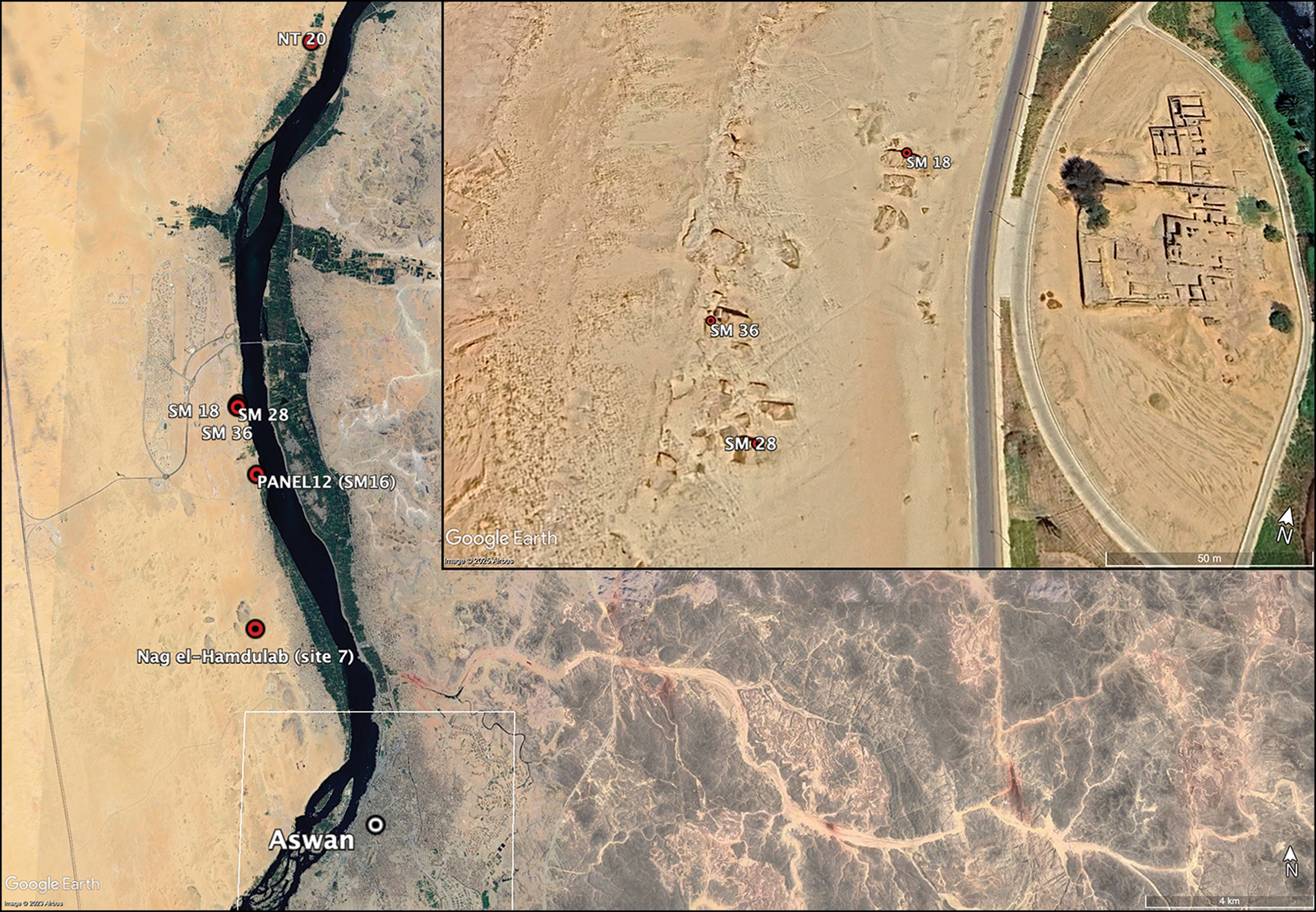

Since 2005, the Aswan-Kom Ombo Archaeological Project (AKAP) has been operating in a vast archaeological concession that spans the Nile Valley and its surrounding deserts in the Aswan-Kom Ombo region. One of the AKAP’s most urgent missions is to document, process and publish archaeological material from the area where the New Aswan City is being built. As part of this, a survey conducted at Gebel Qurna in the Sheikh Mohamed District (approximately 10km north of Aswan, on the West Bank; Figure 3) in November 2022 aimed to process all previously recorded rock art panels and to document those that remained unattributed (Vanhulle Reference Vanhulle2023). The prospected sector faces the Coptic monastery of Shiha, which is located at the emplacement of a Ptolemaic temple dedicated to Khnum and other deities (Figure 3: inset) (Junker Reference Junker1922; Dekker Reference Dekker, Gabra and Takla2013: 94). Most of the petroglyphs date from the fourth millennium BC (e.g. SM28) but one site offers images dating to the Old Kingdom (c. 2750–2250 BC), Middle Kingdom (c. 2045–1700 BC) and from Late Antiquity to the Byzantine era (c. 664 BC–AD 640) (SM18).

Figure 3. Aswan’s West Bank and the location of panel SM36 at Sheikh Mohamed (base map © Google Earth, modified by the author).

Gebel Qurna is located at the southern fringe of the Sheikh Mohammed District. The eastern side of the hill faces the river, from which it is separated by a modern road running north–south. Gebel Qurna served as a quarry for the Ptolemaic kingdom (332–30 BC), and its western part is still being exploited today (De Morgan Reference De Morgan1894: 201–203). Such activities have altered the upper section of this rocky hill, whose slope is strewn with quantities of rubble and large, fallen sandstone boulders. Many of these boulders are covered with petroglyphs and inscriptions from various periods, particularly at and near the current ground level.

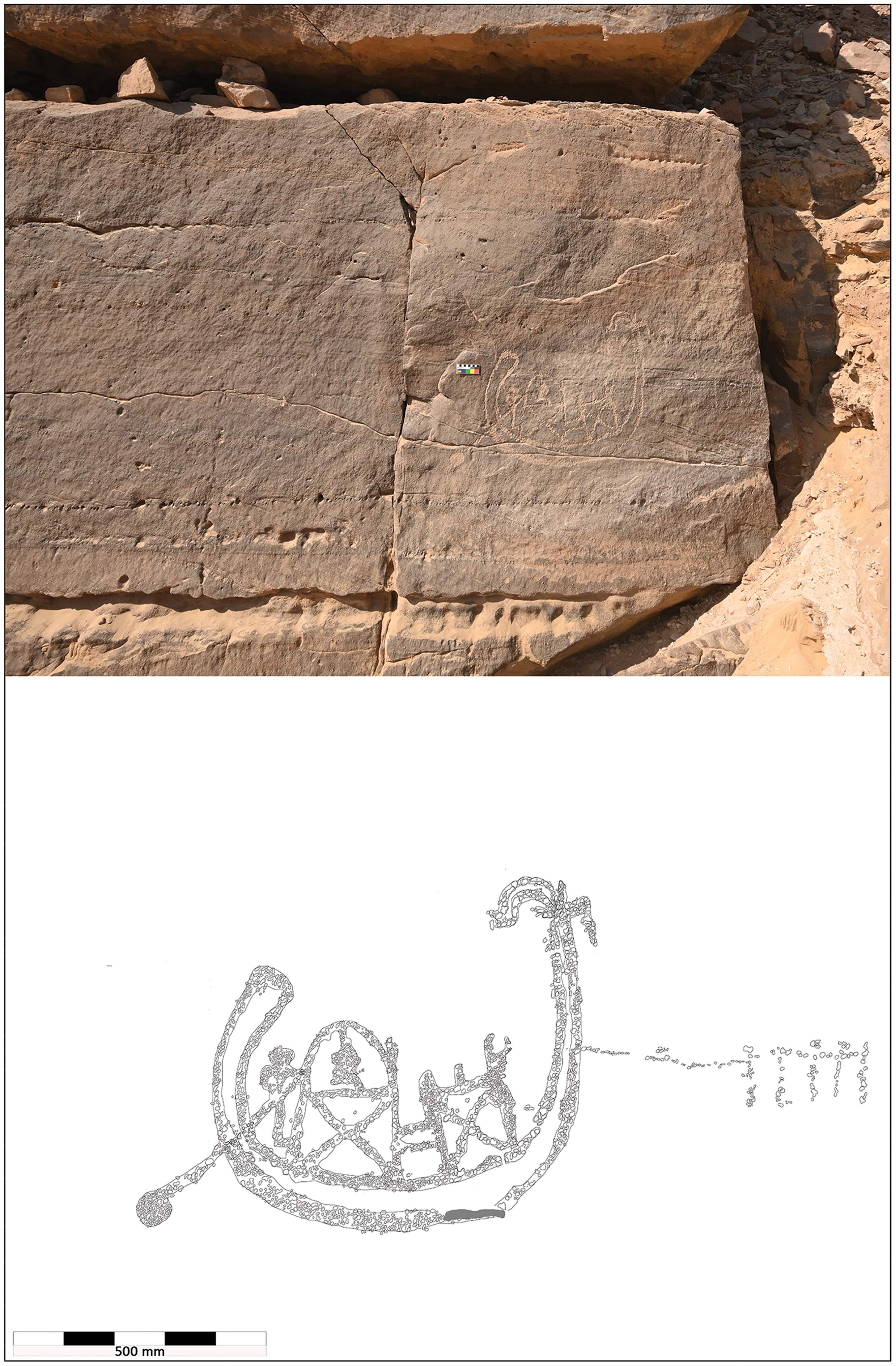

During the survey, a well-preserved engraving of a dragged boat supporting what appears to be a human figure seated on a palanquin-like structure was uncovered (designated as SM36). The rock panel lies on the northern edge of a small recess characterised by a compact sand terrace around 5m long and 2m wide, which offers a good viewpoint towards the Nile and the East Bank (Figure 4). The rock surface is flat and approximately 3m high, topped by a large rock outcrop marking the summit of the hill. The northern side of the outcrop is covered by an accumulation of rocks mixed with a few archaeological materials, such as sherds and bone fragments, that have fallen from the plateau above. Some of this material might relate to tombs documented in the area (Junker Reference Junker1919, Reference Junker1920). Discovered by chance, SM36 was almost completely covered by rubble (Figure 5), explaining its good preservation and the fact that it has not previously been documented despite intense prospecting in this region (Gatto et al. Reference Gatto, Hendrickx, Roma and Zampetti2009).

Figure 4. Panel SM36 partially covered by rubble (photograph by author).

Figure 5. Panel SM36 during the cleaning process (photograph by author).

Description and typo-chronological analysis

The engraved composition consists of an ornate boat dragged by five figures to the right (Figure 6). The boat is propelled by a standing figure holding a rudder-oar and transports what seems to be a seated figure. The engraving is positioned at the eastern edge of a long, flat and otherwise untouched sandstone canvas that is visible from the modern road, although the drawing is too small to be observed from that distance. The current topography of the hill has, however, been drastically altered by quarrying activities and does not offer a pristine image of the original landscape. The (lack of) visibility of the panel in antiquity would have varied depending on factors such as the level of river water during flooding, light levels and the time of day/year.

Figure 6. Panel SM36 after cleaning (photograph and drawing by author).

The outline of the boat is traced by an accumulation of peckmarks. The inner part of the hull is left untouched. No trace of smoothing nor any kind of enhancement of the final image has been identified. The boat consists of a sickle-shaped hull completed by two vertical extremities. The apex of the prow (pictured right) ends with a horizontal bar from which emerge two short garlands that curl down inwards and another that falls vertically outwards. The stern (pictured left) adopts a slightly incurved movement and shows a rounded profile. The standing figure, with a rounded head and square shoulders, is wedged between the stern and the rear deck structure. Only the right arm and front leg are depicted, the other limbs being hidden as an effect of the perspective. The figure is holding a long rudder-oar that ends with a rounded blade. The prow is oriented to geographical north, and the boat is thus depicted sailing downstream, against the wind, which could justify the presence of the stylised figures that appear to be pulling it. Yet even if the direction of travel is incidental, ceremonial barques, with no proper means of propulsion, were presumably always dragged.

There are two deck structures on the boat. One is twofold and consists of a roughly square structure resting on the deck, the interior of which is crossed by two pecked diagonals, topped by a vaulted shelter. A short vertical bar is visible at the top right corner of the vaulted structure, possibly suggesting the presence of a pole or a similar addition. The shape engraved inside the shelter is interpreted as a seated human figure, of which only the head and right shoulder are visible, along with a chin elongation typical for depictions of early rulers that might designate the false beard worn by kings since the First Dynasty (Hendrickx et al. Reference Hendrickx, De Meyer, Eyckerman, Jucha, Dębowska-Ludwin and Kołodziejczyk2014). Although this identification is not uncontentious, careful observation of the panel and its reconstruction based on photogrammetry leaves no other satisfactory conclusion. The vertical stroke on the head of the seated figure cannot be easily explained, although it might be a headdress of some sort. The second structure on the deck is similar to the first and connected to it by two short horizontal bars. The lateral pillars of this second structure are slightly higher than its roof and two curved elements are fixed to the top right corner behind the prow. These could represent horns.

In contrast to the figures depicted on the boat, the figures pulling it are extremely stylised, and the diameter of the peckmarks used to create them and the connecting rope is smaller, presenting the possibility that these two elements are not contemporaneous. Yet, the patina is identical across the engraving and the schematic representation of the pullers is consistent with depictions of dragged boats in Pre- and Protodynastic rock art (Nicolini & Gatto Reference Nicolini, Gatto and Polkowski2023). At this stage, it is reasonable to consider that the whole scene was produced in a single process.

Boats are among the most frequently recurring motifs in Egyptian iconography. This is especially true for Predynastic and Early Dynastic (First and Second Dynasties: Naqada IIIC–D, c. 3085–2686 BC) imagery, in which the boat is ubiquitous and invested with complex ideological and symbolic meanings (Vanhulle Reference Vanhulle2018). As a result of this ubiquity, several typo-chronologies have been suggested (for references see Lankester Reference Lankester2013). Contrary to the high typological variety of boats in the Predynastic period, the Protodynastic and Early Dynastic periods offer highly standardised boat types attested in both rock art (Somaglino & Tallet Reference Somaglino and Tallet2014; Tallet Reference Tallet2015) and portable objects (Vanhulle & Lorre Reference Vanhulle and Lorre2018).

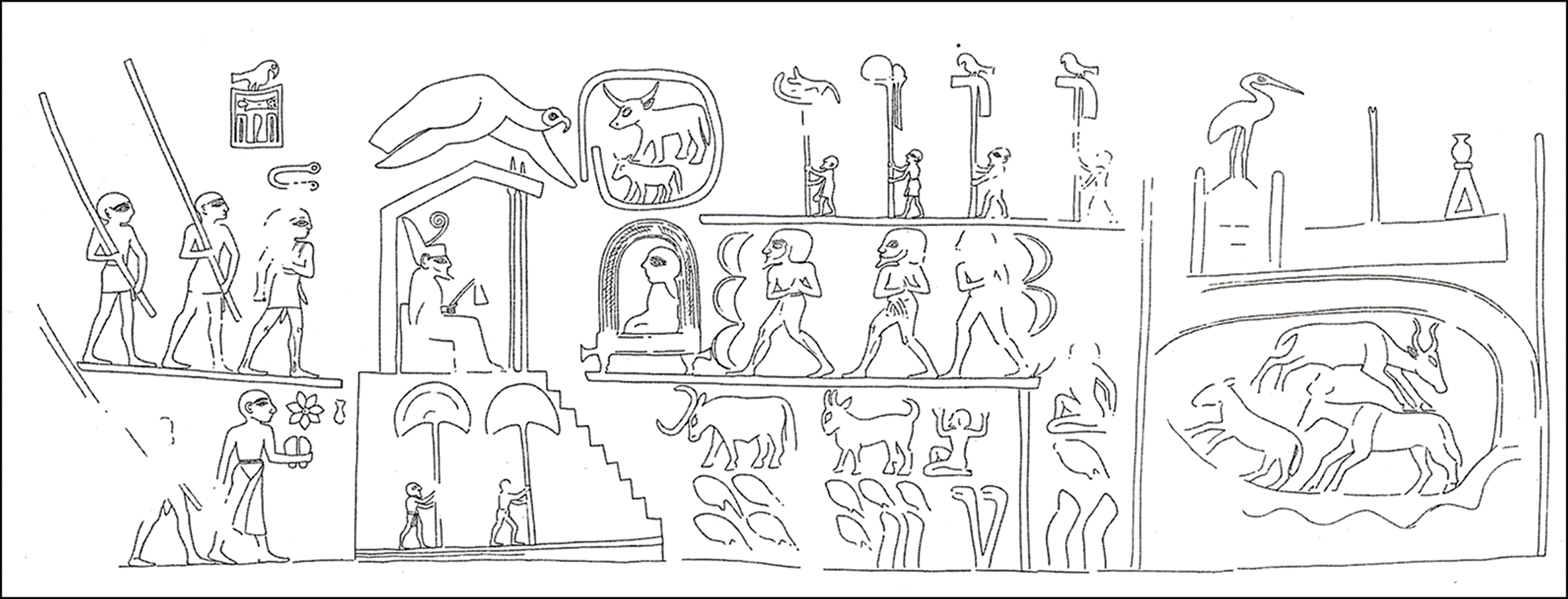

The boat at SM36 belongs to a type typical of the transition from the Protodynastic to the Early Dynastic periods. The vertical extremities, along with the ‘knife-shaped’ profile of the stern, are good chronological markers. Comparable examples are depicted on the Protodynastic Qustul censer (Figure 7; Williams Reference Williams1986: 108–12, 138–47, 360, fig. 171, pl. 34), on a jar probably from the same site (Huyge & Darnell Reference Huyge and Darnell2010) and in engravings at Wadi Abu Subeira (Figure 8; Lippiello & Gatto Reference Lippiello, Gatto, Huyge, Van Notten and Swinne2012: 273, tab. 1). Sterns with a rounded profile are also attested (e.g. an engraved boat at Vulture Rock, Elkab: Huyge Reference Huyge2014: fig. 6c; boat models: Vanhulle & Lorre Reference Vanhulle and Lorre2018: figs. 8, 12, 13). Only a few examples of oarsmen like the one at SM36 are known in rock art, all attributed to the Protodynastic period (Elkab: Červíček Reference Červíček1974: 41, 99, fig. 156; Wadi Abu Subeira: Lippiello & Gatto Reference Lippiello, Gatto, Huyge, Van Notten and Swinne2012: 273, tab. 1; Lower Nubia: Váhala & Červíček Reference Váhala and Červíček1999: 91, pl. 134–530.2; Basch & Gorbéa Reference Basch and Gorbea1968: 232, fig. 230).

Figure 7. A decorated censer from Qustul (height: 85–90mm, diameter: 150mm; image courtesy of the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures of the University of Chicago; E24069).

Figure 8. A Protodynastic boat engraved at Wadi Abu Subeira (photograph by author).

Connected central structures, possibly cabins, and the presence of a pole merging with one of the cabin’s side walls, are more typical of Late Predynastic boats found on contemporaneous Decorated Ware ceramics (Graff Reference Graff2009) and in the exceptional Painted Tomb at Hierakonpolis (Quibell & Green Reference Quibell and Green.1902: pl. LXXV–LXXIX). The presence of lateral pillars higher than the roof also advocates for a Late Predynastic–Early Protodynastic date (Angevin et al. Reference Angevin, Vanhulle, Hendrickx and Madrigal2020: 83–84). The tentative pair of horns attached to the top of the second cabin recalls the Pharaonic Sokar barque; the early form of this ceremonial barque appears at the beginning of the First Dynasty (Darnell Reference Darnell2009: 102–103). Although uncommon, the depiction of an animal head with horns at the top of the prow is attested in Late Predynastic–Protodynastic elite iconography (Vanhulle Reference Vanhulle2019: 10). Its presence on top of a cabin is so far unique.

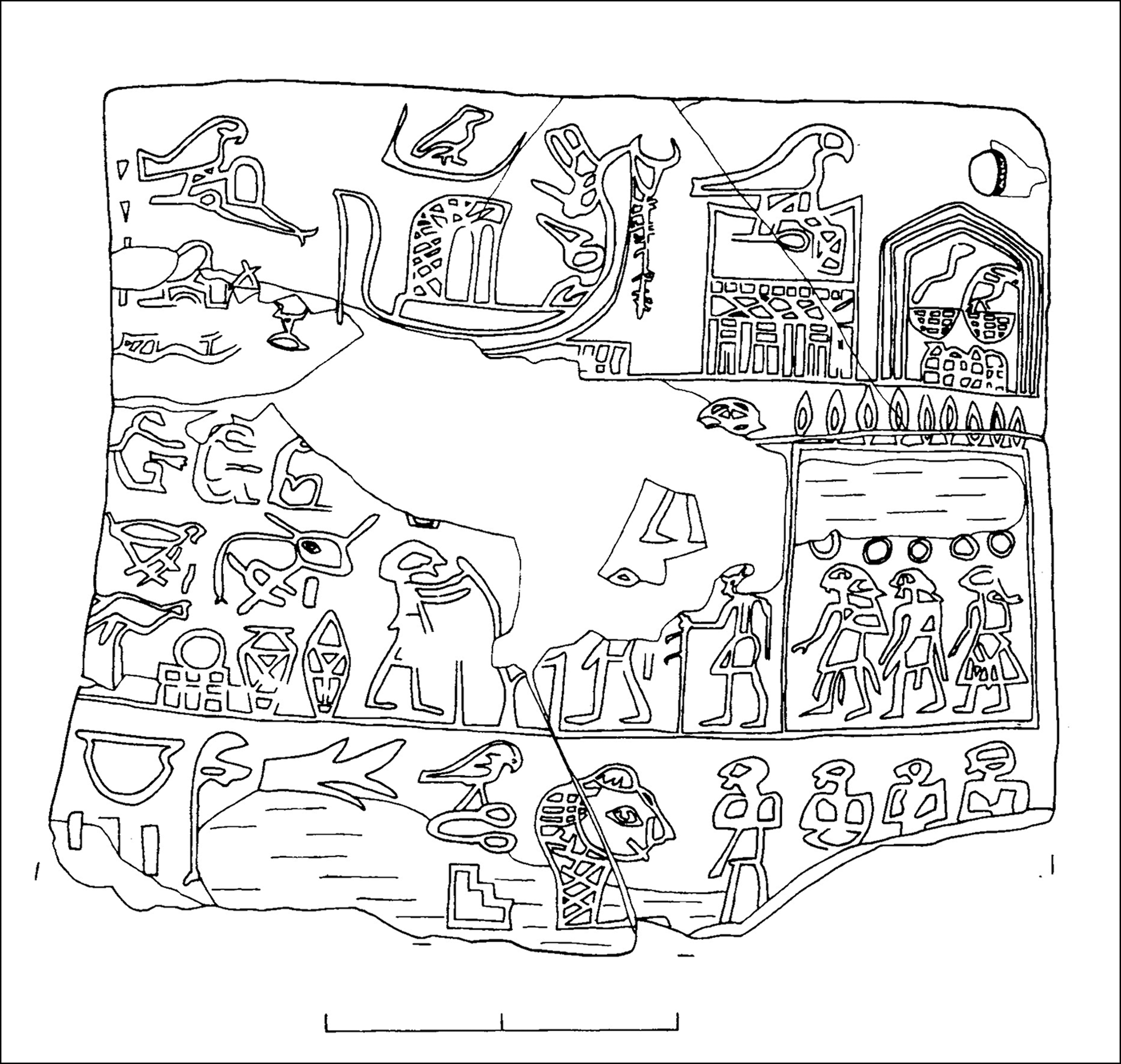

Several highly detailed Protodynastic boat models include a seat on the deck (Vanhulle & Lorre Reference Vanhulle and Lorre2018: figs. 9–13), but depictions of authority figures (identified from their crown and/or stick/sceptre) related to boats never portray these figures inside a closed structure (e.g. Hendrickx et al. Reference Hendrickx, Darnell, Gatto, Eyckerman, Huyge and Van Notten2012: 1074, figs. 7 & 8). The closest currently known parallel for the seated figure at SM36 can be found on the Narmer mace-head, which shows a figure with a similar profile seated in a vaulted palanquin and being introduced to Narmer (Figure 9). Such similarity in style, coupled with the high quality of the engraving, suggests that panel 36 was an official commission.

Figure 9. Decoration on the Narmer mace-head (maximum diameter: 187mm; © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford; E.3631, reproduced with permission).

The boat at SM36 offers structural elements characteristic of the transition between the Predynastic and the Protodynastic periods (Naqada IID–IIIA). Its typology is more typically Early Protodynastic (Naqada IIIA) while the seated figure finds parallels in Late Protodynastic and early First Dynasty official iconography (Naqada IIIB–C). An ivory label bearing the name of Horus Aha, Narmer’s successor, shows a boat with a vaulted cabin, a bovid head and a similar hull typology (Figure 10; Kahl Reference Kahl2001: fig. 10; Jimenez-Serrano Reference Jimenez-Serrano2002: 94–96, fig. 55). The absence of a serekh (a rendering of a palace facade inscribed with the name of a king and surmounted by the falcon-god Horus) associated with the boat at SM36 is significant as this combination is commonly found in royal rock engravings from the First and Second dynasties (Somaglino & Tallet Reference Somaglino and Tallet2014; Tallet Reference Tallet2015: 3–15). This absence would suggest that the seated figure is not a First Dynasty king, and that the engraving probably pre-dates the widespread use of serekh in official rock art. In light of these observations, it seems reasonable to suggest that the panel at SM36 was produced at the dawn of the First Dynasty, perhaps shortly before the reign of Narmer.

Figure 10. Decoration from the ivory label of Horus Aha (height: 48mm, width: 56mm; Egyptian Museum, Cairo: CG14142; drawing by Jochem Kahl/Eva-Maria Engel; © Jochem Kahl, reproduced with permission).

Discussion

Although compositions involving boats and figures representing authority through their posture and paraphernalia are not exceptional in Late Predynastic and Protodynastic iconography (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Logan and Murnane1987), the addition of the engraving at SM36 to this corpus is unique in several ways. Rare images of Protodynastic authority figures, identified as such because of their headdress reminiscent of the Pharaonic white crown and ‘shepherd stick’-style sceptre, are attested before the First Dynasty (Winkler Reference Winkler1938: pl. 6, pl. XIV; Ward Reference Ward2006: 120, fig. 2a; Hendrickx et al. Reference Hendrickx, Darnell, Gatto, Eyckerman, Huyge and Van Notten2012; Hardtke et al. Reference Hardtke, Claes, Darnell, Hameeuw, Hendrickx and Vanhulle2022). The seated figure at SM36 cannot be compared with these images, but it could be related to the official introduced to Narmer on the mace-head discussed above. It is not possible to determine the gender and status of the figure. The image acknowledges his/her social importance as a potential member of the ruling class at the dawn of the First Dynasty.

Egyptologists benefit from a relatively large amount of archaeological data related to the evolution and increasing complexity of Predynastic society, and how these processes impacted craftmanship. The existence of specialised workshops has been postulated, particularly for painted vases and ripple-flaked knives, and sites such as Hierakonpolis offer insights on the specialisation of a part of the population for the production of goods, such as beer and ceramics, in great quantities (Takamiya Reference Takamiya, Hendrickx, Friedman, Ciałowicz and Chłodnicki2004). It is also acknowledged that one of the characteristics of the Early Dynastic period is the standardisation of official discourses, which were expressed through a “formal iconography and its syntax” (Hendrickx & Förster Reference Hendrickx, Förster and Lloyd2010: 852). At the same time, artistic productions also became more standardised, to the extent that the existence of specialised workshops under the commission of the elite and first kings could reasonably be postulated. Rock art has never been considered in these discussions, and it remains to be asked how the formation of the state, and the contemporaneous invention of writing, affected its production.

The techniques used to engrave rock in Egypt included pecking, hammering, incision, grooving, rubbing and smoothing. Rock painting is almost completely absent in Egypt during the fourth millennium BC. In contrast to the Epipalaeolithic (c. eighth–sixth millennia BC), when engravings appear to have been made entirely using the simpler heavy-hammering techniques (Storemyr Reference Storemyr2009), the full range of techniques was used in subsequent periods. Technique is therefore not a generally useful chronological criterion, particularly as the technique employed is often determined by individual arbitrariness, the nature and condition of the rock and the availability of tools. Traceology—the analysis of the operational sequences in the production of an image, with the analyses of use-wear, manufacturing technologies and both macro- and microscopic modifications of the original surfaces included under this umbrella term—might offer new perspectives but reference data from systematic field analysis needs to be collected first.

The general quality and care imbued in the production of SM36 suggests that its creators were masters in their discipline; the tracing of the motifs complies precisely with the canons of the time, it is highly standardised and the seated figure echoes those depicted on prestigious objects discovered in centres of power both in Egypt and Lower Nubia. All this suggests that the panel is a production commissioned by an early form of politico-religious power at the onset of the First Dynasty.

Conclusion

Rock art studies in Egypt and Sudan are constantly developing thanks to new theoretical and methodological approaches, prospecting and fieldwork (Varadzinová Reference Varadzinová2017; Polkowski Reference Polkowski and Smith2018, Reference Polkowski2023; Polkowski & Förster Reference Polkowski and Förster2022). Rock art stands out for its ability to drive discussions surrounding the movement of populations and intercultural landscapes, highlighting communication networks encompassing the deserts and the Nile Valley. Egyptian rock art contributed to the display of authority messages in the landscape, and thus the political construction of territory. From the Protodynastic period, classical Predynastic rock art productions were progressively replaced by strategically located productions restricted to the Nile Valley and its hinterland (Darnell et al. Reference Darnell, Vanhulle, Brémont-Bellini, Urcia, Darnell., Gatto, Medici, Polkowski, Förster and Riemerin press). Rock compositions became a tool for the authorities to communicate, mark the landscape and assert their power.

Rock art was not an accidental practice but rather a social action that followed rules and had intrinsic meanings, functions and goals. Addressing the use of rock art by local and regional rising powers in Egypt during the fourth millennium BC offers new insights on the Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods. It also facilitates discussions about the constitution of a centralised management of the original Egyptian territory and its administrative delimitation. It offers information on how Nilotic and desert landscapes were invested with codified messages by local authorities, and the ways in which these messages were diffused, influenced and appropriated by groups of different ethnic origins.

The rock panel at SM36 is an important addition to the existing corpus of engravings that can help us to better understand the role of rock art in the crucial events that led to the formation of the Egyptian state. Its fortuitous discovery shows the extent of the work to be done and the wealth of data yet to be discovered in the vast open-air museums of Egypt and Nubia.

Acknowledgements

The author expresses his most sincere gratitude to the Egypt Exploration Society, the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (Belgium) and the Centre de Recherches en Archéologie et Patrimoine (Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium) for their financial and logistical support. The fieldwork was undertaken under the umbrella of the Aswan-Kom Ombo Archaeological Project, and the author thanks its directors, Prof. M.C. Gatto and Prof. A. Curci. He extends his deep thanks to the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities and to the colleagues of the Aswan Inspectorate, without whom none of this would have been possible. Last but not least, the author thanks his Egyptian collaborators from Gharb Aswan for their invaluable help in the field.

Funding statement

The fieldwork during which this panel was found has been funded thanks to a Centenary Grant of the Egypt Exploration Society. It benefited from the logistical support of the Aswan-Kom Ombo Archaeological Project and the CReA-Patrimoine (Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium). This research was conducted at the Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures, Polish Academy of Sciences as part of the project PowerArt co-funded by the National Science Centre in Poland and the European Union (Framework Programme for Research and Innovation Horizon 2022 under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 945339. Project no. 2022/47/P/HS3/02953).