Introduction

Whilst still managing the emergency caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Conte II government had to deal with a very instable political situation. In January, after few months of quarrels, the leader of Italy Alive/Italia Viva (IV) (a centrist liberal party), Matteo Renzi, announced that his party would not vote in favour of the reform of the statute of limitations proposed by the Minister of Justice, Alfonso Bonafede. This meant that the government had de facto lost its majority. Thus, on 26 January, before the Senate would vote on Bonafede's reform, Giuseppe Conte resigned as Prime Mister.

The refusal to vote for the reform of the statute of limitations was not primary caused by a disagreement based on content, but by the need, according to Italia Viva and its leader, of a change of Prime Minister, as they did not see Conte fit to manage the large subsidies coming from Europe via the Recovery Fund.

The President of the Republic, Sergio Mattarella, accepted Conte's resignation, dismissed both chambers, and started the consultations for the formation of a new government, as elections were normally scheduled for 2023. Furthermore, all institutional actors agreed that holding an election during the pandemic and with a vaccination plan to organize was not feasible. Then, on 3 February, Mattarella asked Mario Draghi to formally hold a meeting with parties to verify whether a government under Draghi's premiership could be formed. Draghi was the main name proposed by Italia Viva because of his indisputable reputation in both Italy and Europe. He was President of the European Central Bank (BCE) from 2011 to 2019, during the European debt crisis, which he navigated by adopting several measures, including quantitative easing (European Parliament 2015).

After consulting twice with all parties, on 13 February the new government took office. This government was immediately branded as a national unity government, which had two main objectives: the management of the pandemic (which was still very prominent), and the management of the stream of money from the NextGenerationEU Recovery Fund by drafting and implementing Italy's NRRP (Russo & Valbruzzi Reference Russo and Valbruzzi2022). This national interest feature was also reflected in the government composition, as all parties but Brothers of Italy/Fratelli d'Italia (FdI), an extreme right party) were represented in the Cabinet.

The only other major event of 2021 were the local elections held on 3–4 October in almost 1400 municipalities, among which the five largest Italian cities (Rome, Milan, Naples, Turin and Bologna). Overall, the two main issues dominating the political agenda in 2021 were, on the one hand, the COVID-19 pandemic and the related policy issues aimed at managing the health crisis and the vaccination strategy, and, on the other, Italy's macroeconomic policy measures to counteract the pandemic-induced crisis, and more specifically the management of the European recovery package through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NPPR).

Election report

Regional elections

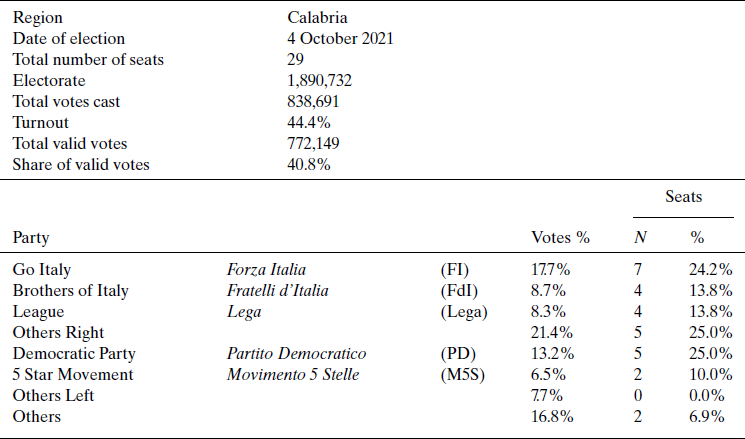

In 2021, only one out of 20 Italian regions, Calabria, held elections. The ballot took place on 3–4 October, following the dissolution of the regional Parliament after the death of Regional President Jole Santelli in October 2020. The ballot was originally scheduled to take place on 14 February and then on 11 April 2021, and was delayed twice due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy.

In terms of electoral supply, a large number of local parties and local electoral lists supporting the same regional president candidate usually compete in regional elections. Table 1 thus shows high levels of party fragmentation. For instance, in Campania, seven different electoral lists supported the centre-left regional president candidate, of which only two (Five Stars Movement/Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S), a populist party, and Democratic Party/Partito Democratico (PD), centre-left) obtained at least one seat in the regional Parliament. The centre-right winning candidate, Roberto Occhiuto, was also supported by seven parties, among which were Silvio Berlusconi's Go Italy/Forza Italia (FI), a conservative right party), the League for Salvini Premier/Lega (Lega per Salvini Premier), a populist radical right party) and Fratelli d'Italia, plus four smaller and local parties. The third candidate to regional president, former mayor of Naples Luigi De Magistris, was supported by six different local lists.

Table 1. Results of regional (Calabria) elections in Italy in 2021

Notes: Others Right: four parties supporting Roberto Occhiuto (then elected).

Others Left: five parties supporting Amalia Bruni.

Others: seven parties, six of which supported Luigi De Magistris and one Cosimo Oliviero.

Source: Archivio Storico Elezioni (2021).

Local elections, which were supposed to be held in spring but were postponed, also took place on the same two days as the Calabrian regional elections. The elections involved 1342 municipalities across Italy, among which were six capitals of region (among which Milan and Rome) and 14 capitals of province. Overall, the centre-left scored good results, including winning in Rome and Milan. The centre-left coalition won in Bologna, Milan and Naples in the first round of the ballot. On 17–18 October, a runoff was held in Rome between centre-right candidate Enrico Michetti and his centre-left competitor Roberto Gualtieri (who was then elected). In Milan, the centre-left incumbent mayor Beppe Sala was re-elected with 57.7 per cent of the votes, while in Naples, candidate Gaetano Manfredi (supported by centre-left lists and M5S) collected 62.8 per cent of the votes, winning in the first round. In Bologna, centre-left candidate Matteo Lepore won in the first round with 61.9 per cent. Overall, the turnout remained relatively low, at 54.7 per cent: almost one in two voters decided not to cast a ballot; particularly in Naples, Turin and Milan the turnout was the lowest ever recorded, at 47.2 per cent, 48.1 per cent and 47.6 per cent, respectively.

M5S lost all the cities in which they previously had a mayor. Also the centre-right did not perform well, losing in all the five largest cities which were electing a mayor.Footnote 1 The leader of Fratelli d'Italia, Giorgia Meloni, highlighted that this bad result could be ascribed to the current divided state of the centre-right coalition (Lauria Reference Lauria2021).

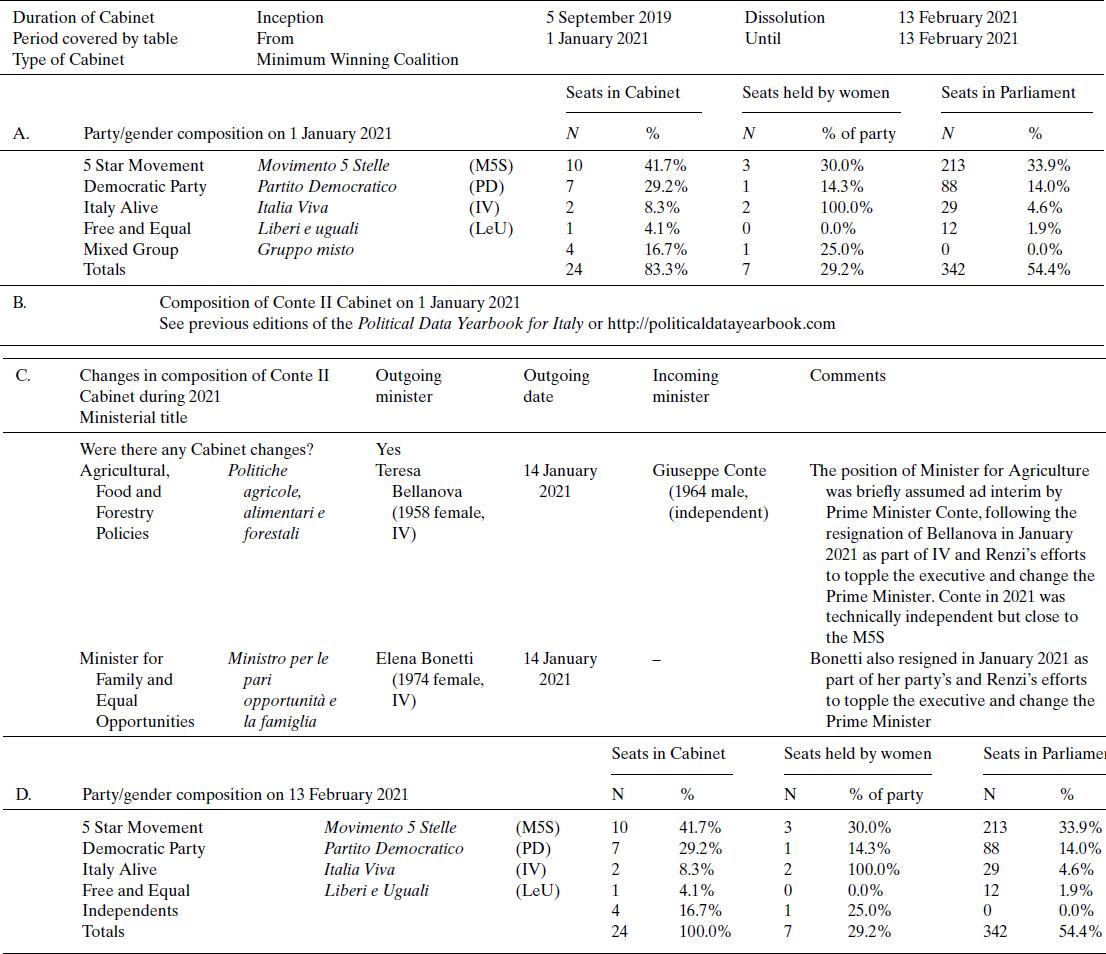

Cabinet report

The Cabinet in office in January 2021 was the second Cabinet formed under the leadership of Giuseppe Conte (Conte II). This government was in charge since September 2019, when the Lega toppled the previous Cabinet (Conte I). The Cabinet in office in January and February 2021 was supported by a minimum winning coalition composed by M5S, Free and Equal/Liberi e Uguali (LeU), a radical left party), Italia Viva and Partito Democratico. Despite having a relatively ample majority in Parliament, this Cabinet was challenged by both the external pressure of the opposition (led by the Lega), and the continuing intra-coalition disputes, raised in particular by Italia Viva. This ultimately led to the collapse of Conte II at the end of January 2021. Until that point, though, the so-called ‘yellow-red’ governmental coalition remained relatively cohesive. There were almost no significant changes in the Cabinet composition until February 2021, as shown in Table 2, except for the position of Minister for Agriculture, which was briefly assumed ad interim by Prime Minister Conte following the resignation of Teresa Bellanova (IV) in January 2021 as part of Italia Viva and Renzi's efforts to topple the executive and change the Prime Minister. Also Elena Bonetti, Minister for Family and Equal Opportunities and member of Italia Viva, followed her party leader's line and resigned the same day as Bellanova.

Table 2. Cabinet composition of Conte II in Italy in 2021

Note: Mixed Group is not a real party but a parliamentary group composed of MPs that had been either elected in smaller parties or used to be part of a party and then left it. The entire group was composed of 46 members, of which 28 were part of the majority and 18 part of the opposition.

Source: Authors’ elaboration of data taken from the website of the government, 2021, www.governo.it.

[Correction added on 22 September 2022, after first online publication: The date mentioned in Table 2 Part D's header has been updated.]

The government coalition created after the 2018 elections, and in particular the one set up in the summer of 2019, has been characterized by a high degree of instability. This is mostly due to the high degree of fragmentation of the Italian party system since 2013 and its somewhat tripolar format, as it is composed by a multitude of sometimes small parties coalesced around a centre-left pole, the M5S, and a centre-right or rather right to extreme right pole. Already at the end of 2020, the conflict within the Conte government worsened, in particular with regard to the European Stability Mechanism (EMS) and the opposition of M5S to it, while internal tensions continued to grow concerning the reform of the electoral law and of symmetric bicameralism. In January, several parties of the government coalition, but especially Italia Viva, started to criticize more openly and aggressively the way in which the executive was managing its relations with Parliament, the Recovery Fund, the health emergency and the secret services.

The failure to put an end to this conflict led, on 26 January 2021, to the resignation of Giuseppe Conte, following a desperate attempt by M5S and the Partito Democratico to put together an alternative parliamentary majority without Italia Viva, by replacing its support with that of the so-called parlamentari ‘responsabili’ (responsible parliamentarians). On 13 February, therefore, the Draghi government took office, with the support of all the parties represented in Parliament with the exception of the extreme right Fratelli d'Italia.

Draghi's mandate was clearly described in the appeal of the President of the Republic, Sergio Mattarella, on 2 February 2021 when he called upon the political parties to confer a vote of confidence on a national unity government that would be able to tackle the various emergencies facing the country, and in particular the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic crisis (De Angelis Reference De Angelis2021). Italian political parties complied with the request of the Head of the State by participating in a government with an exceptionally large majority.

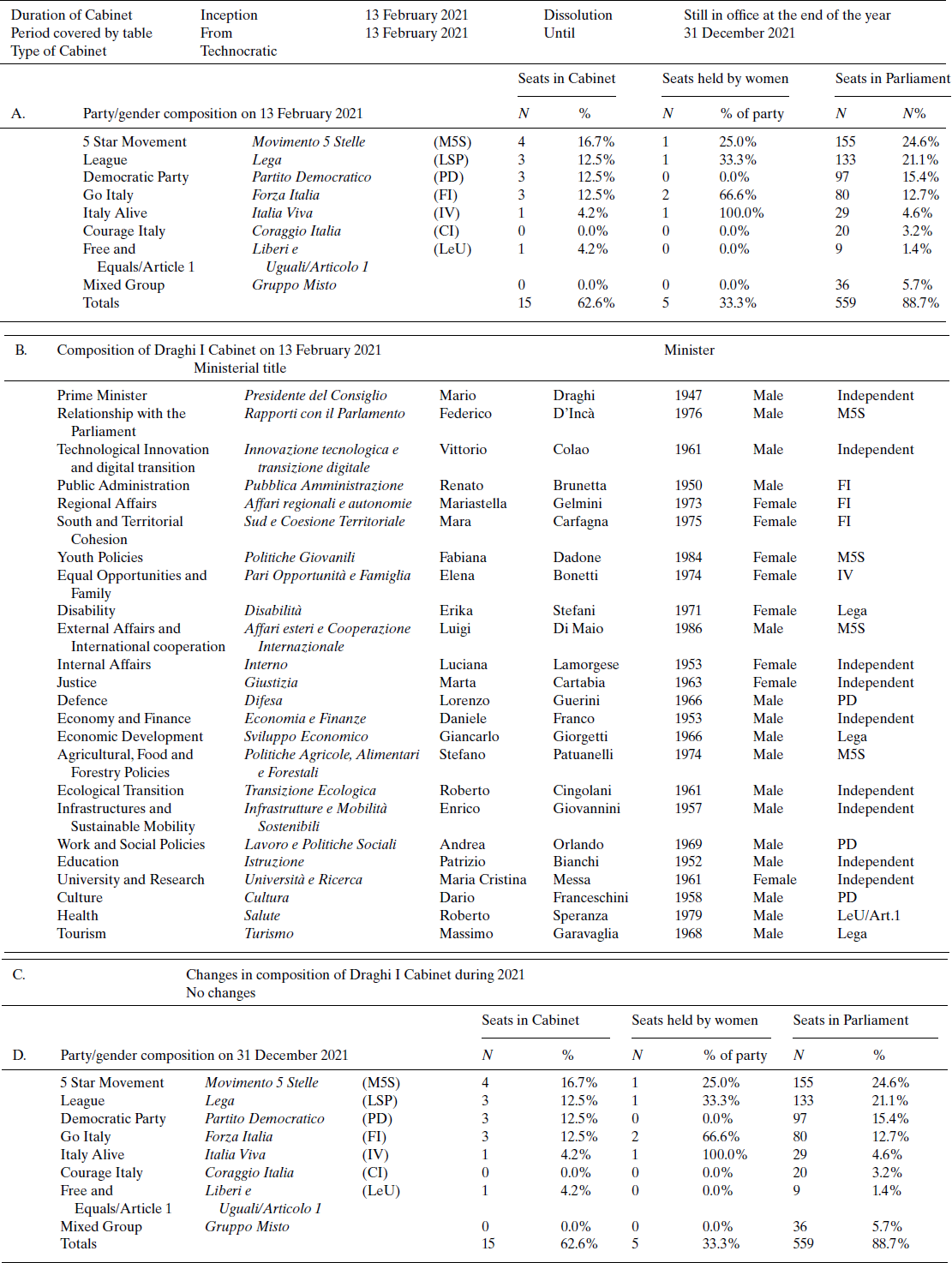

The Cabinet, as shown in Table 3, comprises a mixture of independent experts as well as politicians from most political parties: M5S, Partito Democratico, Lega, Forza Italia, Italia Viva and LeU. The parliamentary majority supporting the executive is also exceptionally broad, given that the executive obtained 535 (over 630) favourable votes in the Chamber of Deputies and 262 (over 315) in the Senate.Footnote 2 The size of the parliamentary majority supporting the executive in the initial vote of confidence was smaller only to the majority obtained by the Monti government in 2011 (556 favourable votes in the lower house and 281 in the upper house) (Kreppel & Marangoni Reference Marangoni and Kreppel2022). This shows the fragility of the unmanageable and fragmentary majority sustaining the government in office, something that is also a reflection of the growing electoral volatility of recent decades and of the very high level of fragmentation of the party system (Emanuele & Chiaramonte Reference Emanuele and Chiaramonte2020; Seddone & Valbruzzi Reference Seddone and Valbruzzi2020).

Table 3. Cabinet composition of Draghi I in Italy in 2021

Notes: ‘Mixed Group’ is not a real party, but a Parliamentary group composed of members of Parliament that had been either elected in smaller parties or used to be part of a party and then left it. The entire group was composed of 62 members, of which 36 were part of the majority and 26 part of the opposition.

Independents are not counted in the number of seats in the Cabinet.

Source: Authors’ elaboration of data taken from the website of the government, 2021, www.governo.it.

While the government type is technocratic, the exact nature of the executive, and whether or not it is a technocratic Cabinet is subject to debate among observers (Kreppel & Marangoni Reference Marangoni and Kreppel2022). A technical expert leads the government, with a core executive that has certainly a technocratic nature, but that includes representation in the Cabinet for nearly all political parties, as only Fratelli d'Italia remain formally outside of the government coalition. As shown in Table 3, 38 per cent of ministers of the Draghi government, including the Prime Minister, are proper technocrats. However, the overall level of partisanship of the Cabinet distinguishes the Draghi government from past technocratic executives, especially Monti's (Garzia & Karremans Reference Garzia and Karremans2021). M5S, Partito Democratico and Lega have three ministers each.

Nevertheless, seven of the eight technocratic ministers of the Draghi executive have a portfolio, while many of the political members of the Cabinet are ministers without portfolio. Moreover, technocratic members of the government hold crucial ministries. Draghi chose a series of very well-qualified experts as ministers of the economy, interior, justice, education, universities, environment, infrastructure and technological innovation, while excluding all the party leaders from positions in Cabinet (Capano & Sandri Reference Capano and Sandri2022; Kreppel & Marangoni Reference Marangoni and Kreppel2022). Thus, the new Prime Minister adopted a highly centralized style of governance and a rather autocratic style of leadership. These choices had significant consequences in terms of the personalization of politics and in terms of political polarization (Russo & Valbruzzi Reference Russo and Valbruzzi2022).

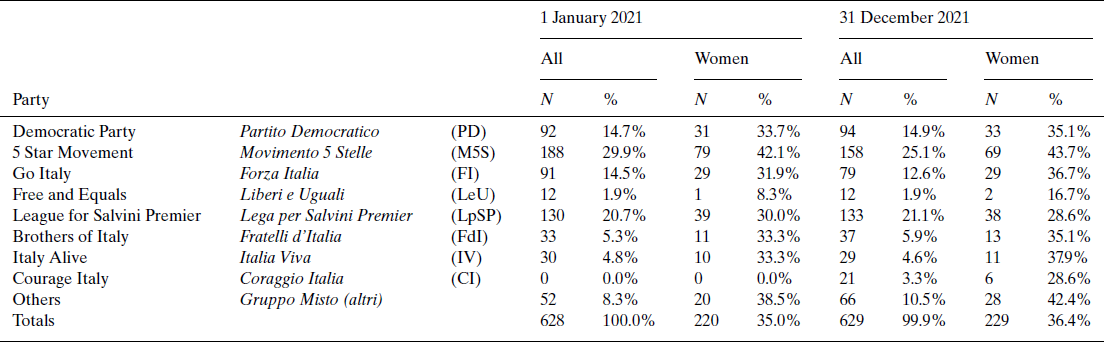

Parliament report

In this legislature, 214 MPs have turned their coats: 143 deputies and 71 senators (Cottone Reference Cottone2021). Many MPs, however, turned their coats several times, jumping from one group to another: 304 MPs in total have switched parties/parliamentary groups since the beginning of the 18th legislative term, averaging about six per month. There were 45 switches in 2021, as Table 4 on the lower house shows (see also Table 5 on the upper house). M5S (with 30 MPs defecting) and Forza Italia (with 12) are the parties most affected by this phenomenon. Forza Italia MP's defections were mainly related to disagreements with the party line. Most of Forza Italia MPs joined Courage Italy/Coraggio Italia! (CI) (a liberal-conservative party and parliamentary group) created in May 2021 by Giovanni Toti, President of Liguria, and by Luigi Brugnaro, former Mayor of Venice, which attracted new members from the more centrist wing of Silvio Berlusconi's party. Most of M5S’ defections can be ascribed to internal disputes regarding the creation of the new government, with several M5S MPs refusing to support the executive led by a ‘Brussels technocrat’.

Table 4. Party and gender composition of the lower house of the Parliament (Camera dei Deputati) in Italy in 2021

Source: Authors’ elaboration of data taken from the website of the Chamber of Deputies, 2021, www.camera.it.

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the upper house of the Parliament (Senato) in Italy in 2021

Source: Authors’ elaboration of data taken from the web site of the Senate, 2021, www.camera.it.

Political party report

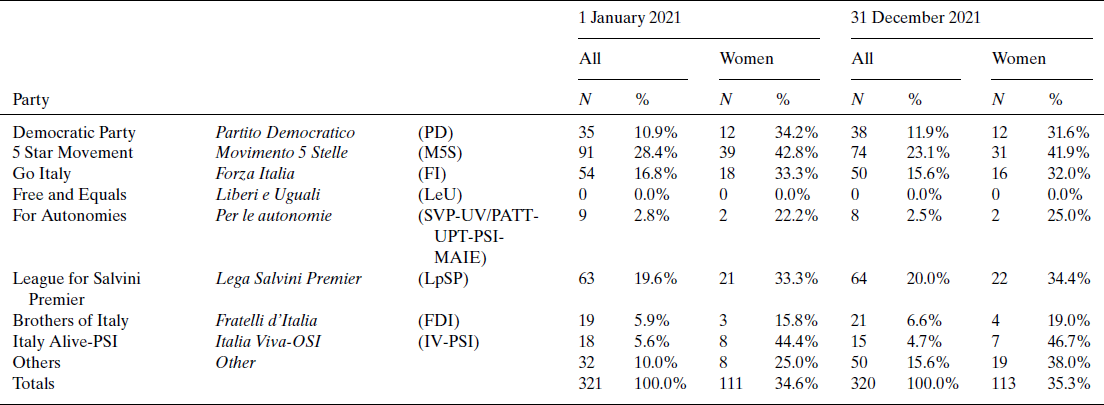

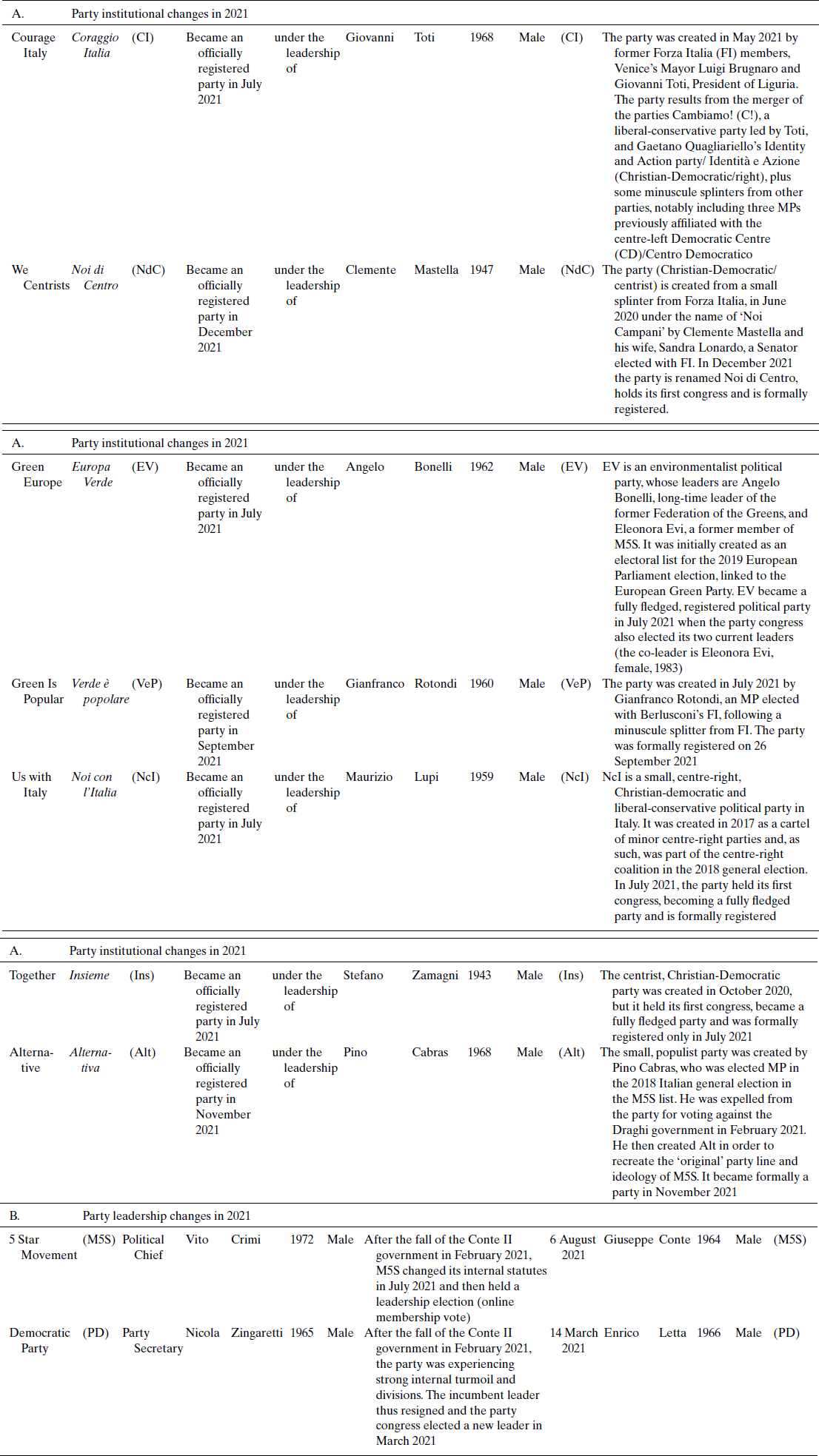

As Table 6 shows, the Italian party system has been characterized by a high degree of instability in 2021. Two major parties (M5S and Partito Democratico) changed their leader, while seven new (quite small and personal) parties were created.

Table 6. Changes in political parties in Italy in 2021

Source: Authors’ elaboration of data taken from the web site of the Chamber of Deputies, 2021, www.camera.it.

In terms of splinters and the emergence of new political parties, four small centrist (either Christian-democratic or liberal-conservative) parties – Coraggio Italia, We Centrists/Noi di Centro (NdC), Us with Italy/Noi con l'Italia (NcI) and Together/Insieme (Ins) – were created throughout 2021 from minuscule splinters from Forza Italia or as a cartel of minor existing centre-right parties (Table 6). They are mentioned here because they all have at least one MP sitting in either the lower or upper house of Parliament and they contribute to increasing the number of small centrist forces in the Italian party system. The minuscule centrist party Alternative/Alternativa (Alt) was created by a former M5S MP in November 2021, after having been expelled from the party for voting against the Draghi government in February 2021. Two other small parties were also created in 2021, either by splinters from the existing green party Green Europe/Europa Verde (EV) or by Forza Italia defectors (Green Is Popular/Verde è popolare – VeP). This shows that not only is the party system fragmented, but the parties themselves are very unstable and internally divided.

In terms of party leadership change, Enrico Letta succeeded Nicola Zingaretti at the head of Partito Democratico by obtaining 860 votes in the party's national congress on 14 March. Zingaretti resigned two weeks before because he deemed to have failed to maintain party unity and manage internal factions after the splinter of Italia Viva and the dissatisfaction with the creation of Draghi's Cabinet.

M5S was plagued by overall high levels of internal conflict and instability, parliamentary defections and expulsions of elected officials for not respecting the party line or financial engagements with the party and by internal conflict. The party also changed its leader in August 2021. For M5S, founded by Beppe Grillo and Gianroberto Casaleggio in 2009, 2021 was a very complicated year. The party was significantly divided on its support for the new technocratic Cabinet since the fall of the Conte II government, and on the organizational model to follow. Davide Casaleggio's and Grillo's vision of an inherently ‘digital party’, devoid of intermediate structures, contrasted with Conte's idea of strengthening the party on the ground and developing more traditional organizational settings. In June, Casaleggio left M5S and took with him the party platform Rousseau (its main organizational tool) and the whole membership register.

M5S finally held an internal online membership ballot on 6 August for selecting a new leader and replacing the interim leader Vito Crimi (nominated in January 2020) on the new platform SkyVote. Giuseppe Conte was elected with 94.2 per cent of the 59,047 votes cast. These lines of conflict also led to further defections of MPs from the ranks of M5S, with a total loss of about a third of the number of representatives it had at the beginning of the legislature. The departing MPs joined either the Lega or the so-called ‘Mixed Group’ (for parliamentarians without a recognized party affiliation).

In 2021, Draghi's centralized style of leadership heightened internal tensions, especially in the parties of government. The internal fractures were to be found in all the parties. Within M5S, divisions between Giuseppe Conte and Luigi Di Maio increased in 2021. Within the Lega, Matteo Salvini appeared to be holding on to his position of leader, but also seemed increasingly vulnerable. There were also divisions in the coalition within the centre right (between Salvini and Giorgia Meloni and within Forza Italia). And even though they are less visible than in other parties, divisions were also apparent in the Partito Democratico (Capano & Sandri Reference Capano and Sandri2022).

Institutional change report

In Italy, in 2021 there were no significant changes to the constitution, to the basic institutional framework, the electoral law or any other major reform. In terms of structural reforms, notwithstanding the positive results in managing the COVID-19 pandemic, the related economic crisis and the NRRP, the government's record was relatively poor. While the reform of the system of taxation had already been initiated, as had the reform of the judicial system, with legislative decrees having been adopted in the fall of 2021 to improve the efficiency of civil and criminal proceedings, several important reforms have yet to come (from social and civil rights to public administration reform).

From a foreign policy perspective, however, the new Cabinet achieved an important result in 2021: on 26 November, the Quirinal Treaty was signed in Rome. Formally called the Treaty between the Italian Republic and the French Republic, it enshrines enhanced bilateral cooperation between the two countries and aims to provide a stable and formalized framework for cooperation between them, as a kind of transalpine equivalent of the Elysée Treaty and the Treaty of Aachen on Franco-German cooperation.

Issues in national politics

As the pandemic was still prominent in 2021, and the vaccination campaign took off in February, on 4 March the government decided to postpone to the fall the local elections, which were expected to take place in spring. The vaccination campaign started on 31 December 2020, giving priority to essential workers (i.e., those working in hospitals, school, police, etc.) and vulnerable citizens. On 13 March the appointed Extraordinary Commissioner, General Francesco Paolo Figliuolo, presented the national vaccination plan, which aimed at vaccinating 80 per cent of the Italian population by September 2021 (Istituto Superiore di Sanità Reference Sanità2021). As of 1 July, the government ratified the measures linked to the so-called Green-Pass, which regulated travel within the European Union (EU) and access to public venues and private leisure establishments (Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri 2021a). To obtain a Green-Pass, citizens needed to be either vaccinated, recovered or have tested negative for COVID-19. All parties in government formally supported the Green-Pass regulations, but inside the Lega there were diverging opinions. Fratelli d'Italia, in the opposition, strongly opposed the measures. This unique position in the party supply was probably one of the reasons for the wide support elicited by the measures among the Italian population and, at the same time, the cause for the growing tensions within the right-wing coalition, especially with the Lega (Russo & Valbruzzi Reference Russo and Valbruzzi2022).

During the summer, the number of infections stayed low, but on 26 November, with the trend increasing again, the government ratified a more restrictive law, requiring a Super Green-Pass in order to access publics places and events. The main difference consisted in the fact that a negative test was no longer one of the valid options to acquire the pass (Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri 2021b). Thus, only vaccinated or recovered citizens had access to public places such as gyms, restaurants, cinemas, etc. These further restrictions were harshly criticized by the opposition (Fratelli d'Italia) and caused again some divisions in the Lega, which, however, did vote in favour of them (Zapperi Reference Zapperi2021).

On 23 December further COVID-19 related restrictions were adopted, including lowering the validity of the Green-Pass from nine to six months, compulsory masks also in open spaces, and mandatory use of FPP2 masks in closed spaces, along with the ban of large group gatherings in both closed and open spaces until end of January 2022 (Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri 2021c).

The other significant issue in national politics in 2021 was the management of the stream of money from the Recovery Fund by drafting and implementing Italy's NRRP. The centralized style of governance adopted by Draghi in the management and development of the NRRP, vis-à-vis both the governing parties and the regional governments, provided the EU with the reassurance it required to enable Italy to become the main beneficiary, together with Spain, of the Recovery Fund. Draghi obtained a large amount for the NRRP and increased it with national funds. The government achieved by 31 December 2021 the first 55 goals and milestones listed in the plan, and had initiated the other 102 planned for 2022 (Capano & Sandri Reference Capano and Sandri2022).