Introduction

The ever-growing problem of climate change and climate variability continues to pose a major threat to the survival of humankind worldwide. Smallholder farmers have been particularly affected, with their capacity to adapt to climate change being poor. The sustainable use of genetically diverse genotypes is an important strategy for responding to the various biotic and abiotic stresses arising due to climate change (Henry Reference Henry2020). Genebanks are repositories of useful plant diversity and play a critical role in enhancing climate resilience and improving agricultural productivity. The rich genetic diversity held in genebanks comprising multiple ecotypes of documented provenance is a great resource harbouring great potential for adapting crops and their varieties to current and future climates as well as responding to other challenges (Wambugu et al. Reference Wambugu, Nyamongo and Kirwa2023). The limited deployment of this valuable treasure trove in research, breeding and direct use by farmers, however, remains one of the largest constraints facing genebanks, particularly the national germplasm collections. Among other factors, this situation can be attributed to weak or non-existent linkages between genebanks and germplasm users (Engels and Ebert Reference Engels and Ebert2021).

There is a need for a paradigm shift in the way genebanks engage with different users and stakeholders. This calls for genebanks to explore new partnerships with different users and be responsive to their needs in order to ensure greater use of their collections, the majority of which remain grossly underused (FAO 2010; Wambugu et al. Reference Wambugu, Furtado, Waters, Nyamongo and Henry2013). Traditionally, the greatest role and contribution of genebanks have been in the provision of germplasm for crop improvement and research purposes. Over the years, the direct use of genebank materials by farmers has to a large extent been neglected or not given priority. However, as noted by Westengen et al. (Reference Westengen, Skarbø, Mulesa and Berg2018), there is an emerging trend where genebanks are increasingly working directly with farmers through diverse approaches. Efforts by genebanks to meet the seed and varietal demands of farmers is therefore providing an alternative pathway through which germplasm collections are being utilized to support farmer-managed seed systems (Stoilova et al. Reference Stoilova, van Zonneveld, Roothaert and Schreinemachers2019). The Genetic Resources Research Institute (GeRRI), under which Kenya’s national genebank falls, holds a large collection of over 51,000 accessions representing close to 2,000 known plant species (GeRRI 2025). Despite the collection and the associated data being freely available under the terms of existing national and international policy frameworks, it remains poorly accessed and thus grossly underutilized. Over the past decade, only 3,612 accessions have been distributed to users, underscoring a substantial gap between conservation efforts and germplasm use (GeRRI 2025).

GeRRI’s engagement with small holder farmers has been extremely low and has largely been passive, ad hoc and opportunistic, thereby contributing to the limited use of conserved germplasm. In order to enhance the contribution of GeRRI’s collections to increased agricultural productivity and food security, there is need to ensure greater, coordinated and more structured engagement with primary germplasm users such as breeders, researchers and farmers. In the last five years, GeRRI undertook active structured engagement with breeders and farmers aimed at increasing farmers’ access to conserved germplasm and facilitate its use. The genebank and its partners pursued this goal by piloting a new concept called ‘Germplasm User Group (GUG)’ that is intended to facilitate organized engagement between the national genebank and germplasm users as well as other stakeholders who seek to increase crop and varietal diversity/options. These groups involved farmers, researchers, breeders, extension service, policy makers and other actors in the agricultural sector who are involved or benefit from the conservation and utilization of germplasm. The goal of the GUG initiative is to strengthen the linkages between genebanks and germplasm users through structured engagement that enables farmers and other stakeholders to access and sustainably use conserved crop diversity to enhance food security and climate resilience. The main objective of this paper is to gain understanding on the feasibility and effectiveness of the GUG model as a structured approach in supporting farmers in crop and varietal diversification using genebank collections. Specifically, the study sought to (1) examine the technical and socio-organizational aspects influencing the formation, functioning and management of GUGs (2) document and analyze the process of assembling diversity sets for participatory evaluation by GUGs, including the use of characterization and passport data; (3) assess the effectiveness of GUG activities in enhancing farmers’ access to and use of crop diversity conserved in the national genebank.

Methodology

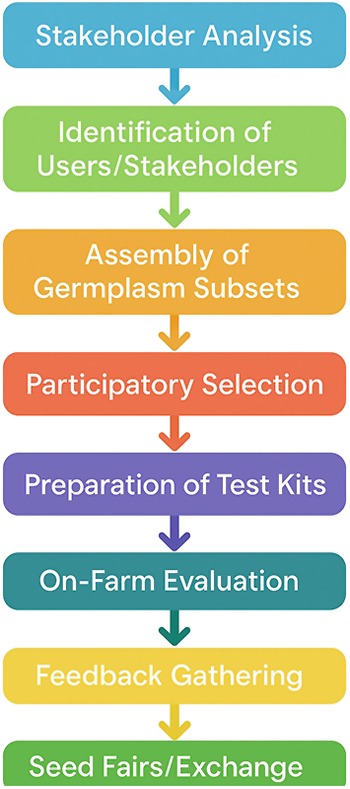

GeRRI used various approaches to establish GUGs and support their activities to facilitate farmers’ access and use of conserved accessions of sorghum (Fig. 1). The planning and implementation of these approaches are detailed below.

Figure 1. Pathway for farmers’ access to crop diversity conserved in genebanks.

Establishing germplasm user groups

Study sites

The GUG activities were undertaken in Busia and Siaya Counties in Western Kenya. Busia County experiences a bimodal rainfall pattern, with the long rains occurring from March to May and the short rains from August to October. The mean annual rainfall ranges between 750 and 2,000 mm. Temperatures vary from an annual mean maximum of 26–30 °C to an annual mean minimum of 14–22 °C. The altitude ranges from 1,130 to 1,500 meters above sea level (asl). The County is divided into four agro-ecological zones: Lower Midland (LM1–LM4). Most of the soils are sandy loam with dark clay domination in some parts and have low natural fertility (County Government of Busia 2023a, 2023b).

Siaya County has a bimodal rainfall regime, with long rains occurring from March to June and short rains from September to December, receiving 800–2,000 mm annually. The altitude ranges from 1,140 m to 1,400 m asl. Temperatures range between 16 and 29 °C, and the area spans Lower Midland agro-ecological zones (LM1–LM5). Soils are predominantly ferralsols of moderate to low fertility, with localized black cotton, loamy and red volcanic soils (County Government of Siaya 2023).

Study crop

The GUG activities reported in this paper focused on sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.), which is a major food and nutritional security crop in western Kenya. Sorghum has important climate resilience traits making it a good option for small-scale farmers to adapt to climate change in this region, which currently faces increased frequency of droughts and high temperatures. Production of traditional drought tolerant crops such as sorghum is common in this region but has been declining. In order to realize the full potential of sorghum, it is important that efforts are made to promote its production and consumption, and to take advantage of its immense value addition opportunities.

In addition to its capacity to enhance food security and climate resilience, this study targeted sorghum due to the high sorghum diversity conserved at GeRRI. GeRRI holds the duplicate collection of African sorghum diversity, with the total sorghum collection amounting to 6418 accessions. Although sorghum was selected as the initial crop for piloting, the GUG model is inherently scalable and can be applied to any crop conserved in the genebank.

Stakeholder analysis

A detailed stakeholder analysis was conducted to initiate the process of establishing GUGs using the ‘snowball approach’ through a questionnaire survey (Goodman Reference Goodman1961). Using this approach, an initial group of stakeholders provided names of other organizations that they work with or are relevant to the sorghum value chain. The stakeholders were identified by evaluating their mandate, interest and level of engagement in planting materials, germplasm, sorghum production and marketing as well as climate resilience issues related to sorghum cultivation. Additionally, their experience, resources, capacities and the nature of engagement with other stakeholders were also considered. The analysis also helped define the farmers’ and other stakeholders’ goals and interests. The aim of the stakeholder mapping and analysis was to identify actors along the entire sorghum value chain. User engagement meetings and workshops were also conducted and assisted in supplementing the stakeholder analysis in identifying and developing new partnerships. The selected actors were those whose mandate, activities or expertise included one or more of these activities: sorghum production, processing and marketing; germplasm conservation and utilization; climate resilience, adaptation and sustainable agriculture initiatives; sorghum research and breeding; capacity building, extension services and farmer organization support.

Identifying germplasm subsets for farmer-managed on-farm testing

With a sorghum collection of 6,418 accessions, Kenya’s national genebank faces a challenge of identifying genotypes that may provide diversity that meets the needs and preferences of specific groups of farmers. A multi-stage process was used to identify germplasm subsets for on-farm evaluation by GUGs, with the initial diversity subsets planted in 3 locations namely Kibos, Samanga and Kakamega. For subsets planted in Kibos and Samanga, the initial selection was done using characterization data, with the goal being to identify subsets with as wide diversity as possible for key agro-morphological traits. Out of the total sorghum collection, a total of 3,864 accessions had varying levels of characterization data. Out of these, a total of 712 accessions had complete data for the traits of interest namely time to flowering, plant height and panicle size and colour. From this subset, 360 accessions were selected based on the diversity observed across these traits. Further selection within this latter subset was done using passport data through a random stratified sampling method, through which 200 accessions were selected. The key criteria at this stage were the identification of subsets with wide eco-geographical distribution. Passport data basically indicates the origin of the accessions. The third stage of constituting the subsets involved participatory variety selection (PVS) where farmers were accorded an opportunity to select their preferred genotypes based on their own selection criteria. In addition to PVS conducted on the subset described above, another PVS event was conducted in Kakamega. This PVS was done on accessions planted in germplasm regeneration fields established for materials whose viability had declined below recommended conservation standards.

A total of five farmer PVS field days were conducted both on-station and on-farm, with the participants per selection event ranging from 30 to 60 farmers. The main criteria for selecting the farmers were gender balance, participants must have been sorghum farmers and they should have been picked from wide geographical areas and different agro-ecological zones across Busia and Siaya Counties. The farmers were provided with a data collection tool in which they recorded the preferred selection criteria and the reasons why they selected particular accessions. There was no limit on the number of accessions that a farmer could select. During the five PVS field days, a total of 2,041 sorghum accessions were evaluated across the three sites: 200 at Kibos, 200 at Samanga and 1,841 at Kakamega. From these diversity sets, only the farmer-preferred accessions selected at the Kibos site were advanced to on-farm evaluation, where farmers further assessed them under their own production conditions.

Analysis of the PVS data was conducted to identify the most popular farmer-preferred accessions for seed bulking and further on-farm evaluation by the GUGs. Preference was determined by examining the number of farmers who selected each accession during the scoring exercise. During the PVS conducted at Kibos, a total of 51 accessions were selected by at least one farmer. Seeds of these accessions were multiplied in plots measuring 10 m x 10 m following standard agronomic practices in order to increase the seed quantity.

On-farm testing of accessions by GUGs

The farmer-managed evaluation was conducted through a modified tricot approach following crowdsourcing and citizen science approaches (van Etten Reference van Etten2011; Van Etten et al. Reference Van Etten, Beza, Calderer, Van Duijvendijk, Fadda, Fantahun, Kidane, Van De Gevel, Gupta, Mengistu, Kiambi, Mathur, Mercado, Mittra, Mollel, Rosas, Steinke, Suchini and Zimmerer2016). This involved engaging a large number of farmers to test, evaluate and select varieties that best suit their needs and local conditions on their own farms. The bulked seeds were organized into test kits, with each kit comprising of two farmer-preferred accessions and a check variety. The check variety that was used was called Seredo, an open-pollinated released variety. The check variety was selected in consultation with the farmers. The seed kits were distributed randomly to participating farmers affiliated with different GUGs thus helping to achieve replication across farms. Most of the farmers, even within the same GUG, received different sets of genebank accessions for testing. The genotypes were labelled A, B and C, with C being the check variety. The farmers planted the three genotypes in small plots in their farms and maintained them using their normal management practices. On average, plot sizes measured about 20 m2 consisting of four rows each 5 m long with 0.75 m inter-row and 0.25 m intra-row spacing. Sowing across the various farms was done between 15th and 31st March. Data was collected at harvest by enumerators using a questionnaire. The collected data was mainly on farmer profile, trial setup, variety ranking, number of farmers who had requested specific accessions and those who had saved seeds of particular accessions. Farmers evaluated the three genotypes and ranked them (1st, 2nd, 3rd) according to various farmer-preferred traits such as grain colour, plant height, panicle size, time to maturity and overall performance. This ranking enabled pairwise comparison of the genotypes.

Feedback gathering

A series of farmer feedback meetings involving different GUGs was held. The meetings were intended to provide an opportunity for farmers to share information and their experiences on the various GUG activities that have been implemented together with the national genebank. Farmer feedback was collected on (1) suitability and usefulness of the methods used in supporting the farmers in varietal diversification efforts, including PVS and tricot approach where different farmers evaluated different sets of accessions and (2) strategies of enhancing sustainability by ensuring that the promising accessions are maintained within the GUGs and also shared with other farmers and stakeholders outside the GUGs.

Data analysis

Trait means for selected and rejected sorghum accessions from the PVS trials were computed using Microsoft Excel. Differences in trait means between the two groups were tested using a Welch’s t-test implemented in R, which does not assume equal variances between groups. To complement significance testing, effect sizes were estimated using Cohen’s d, which standardizes the mean difference by the pooled standard deviation to quantify the magnitude of differences. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed to test whether selected and non-selected accessions differed significantly across the six traits (seed weight, panicle length, days to 50% flowering, plant height, grain number and panicle width). Analyses were conducted using the statsmodels MANOVA procedure in Python (v3.11).

The interest of the farmers in genebank accessions relative to the check variety were evaluated in the on-farm trials by calculating: (i) the percentage of trials in which neighbours and relatives requested seed of the test entries, (ii) the percentage of trials in which the farmer evaluating the accessions saved seed themselves and (iii) the percentage of trials in which either a genebank sample or the check variety was ranked as the best for overall performance. This data was analyzed using chi-square tests of independence. For each aspect (neighbours requesting seed, seed saving and overall performance ranking), the observed percentages were converted to counts, and 2 × 2 contingency tables were constructed comparing genebank accessions against the check variety. Significance was assessed at p < 0.05, and results were verified with two-proportion z-tests and Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Stakeholders identified and partnerships developed

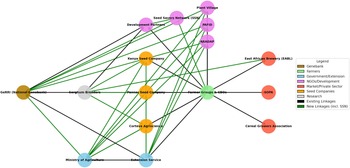

The stakeholder mapping and analysis was conducted on 44 actors and enabled the identification of key stakeholders, the majority of whom have an interest in the sorghum value chain. In total, 35 actors including 26 farmer groups, public breeders, marketers/aggregators, extension service, universities, grass root organizations such as Seed Savers Network, NGOs and CBOs were identified as important partners (Fig. 2). The partners assumed different roles including farmer mobilization, conducting and coordinating germplasm characterization, variety selection and evaluation, training and linking farmers to markets and aggregation centres. The aggregation centres were intended to collect sorghum produce from many farmers in an area before the bulked harvest was transported to buyers or processing facilities (Table S1). The identified farmer groups were from different agroecosystems and had a membership of more than 1000 farmers in total, with each group having 25-80 members. These existing groups, the majority of which were formally registered as ‘saving associations’ and engaged in diverse agricultural activities, were transformed into 26 GUGs and they subsequently engaged in various GUG activities. Each farmer group had a local leadership structure and this provided structured channels through which communication was done. These leadership structures were crucial for sustained engagement between GUGs and GeRRI. Partnerships were developed with the sorghum breeding and research teams from local universities and research centres namely Rongo University, KALRO – Kakamega and Maseno University as well as Seed Savers Network and various NGOs working on seed and diversity issues (Table S1).

Figure 2. Stakeholder network for sorghum value chain in western Kenya.

During the user engagement workshops some of the additional actors mentioned above that are relevant in the sorghum value chain were identified. During these workshops in-depth discussions on farmers’ seed and varietal needs and preferences as well as the opportunities that exist for the genebank to respond to them were conducted. The workshops also provided an opportunity to set priorities, plan and review the GUG activities, including discussing results of PVS. Discussions also focused on available market opportunities, with farmers requesting to be linked with markets for their sorghum produce. In order to address this request, stakeholders involved in the aggregation and marketing of sorghum were identified and invited to subsequent workshops where they had constructive engagements with farmers and other GUG members. These include Sopa supplies, Cereal Growers Association (CGA), Plant Village and East African Breweries. Through this engagement, farmers were provided with linkages to markets and aggregation sites, particularly the East African Breweries, which provides the largest and ready market for sorghum in Kenya. Training was also provided to GUGs, particularly on seed production and handling in order to ensure that farmers would harvest and save quality seed.

The partnerships were organized around a multi-stakeholder, participatory framework coordinated by GeRRI. Over time, the partnerships in some of the GUGs matured from top-down coordination to more decentralized and independent collaboration to the extent that some farmer groups integrated GUG activities and discussions into their regular meetings. The groups also took greater control and ownership of decision-making over their activities such as sharing of crop diversity within the groups. The diversity was also shared with neighbours, relatives and other farmers that were outside the GUGs.

Accessions identified for testing by GUGs

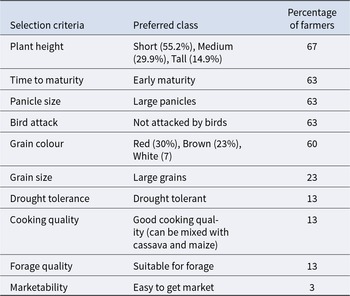

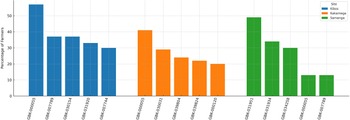

Out of the 2,041 accessions evaluated by farmers, 393 of them were selected as preferred varieties by at least one farmer. These include 41 and 51 accessions selected at Kibos during the first and second season respectively, 262 selected in Kakamega and 39 in Samanga. Farmers preferred accessions with traits that determine their climate adaptability, cooking quality, marketability and degree of bird damage. At Kibos location, farmers reported that the key selection criteria included plant height, time to maturity, panicle colour and resistance to bird’s attack (Table 1). Although farmers had reported a clear preference for early maturing varieties (Table 1), analysis of PVS data indicated farmers mainly selected mid maturing accessions (Fig. 3). Similarly, while farmers had indicated their preference for accessions of short and medium plant height (Table 1), PVS data indicates that farmers mainly selected medium statured plants (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Frequency distributions for (a) days to 50% flowering and (b) plant height for accessions selected and not selected by farmers during participatory variety selection (PVS).

Table 1. Traits and percentage of farmers preferring them during participatory variety selection in Kibos, Western Kenya (n = 30)

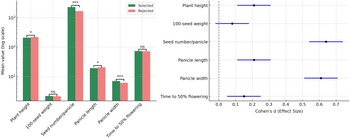

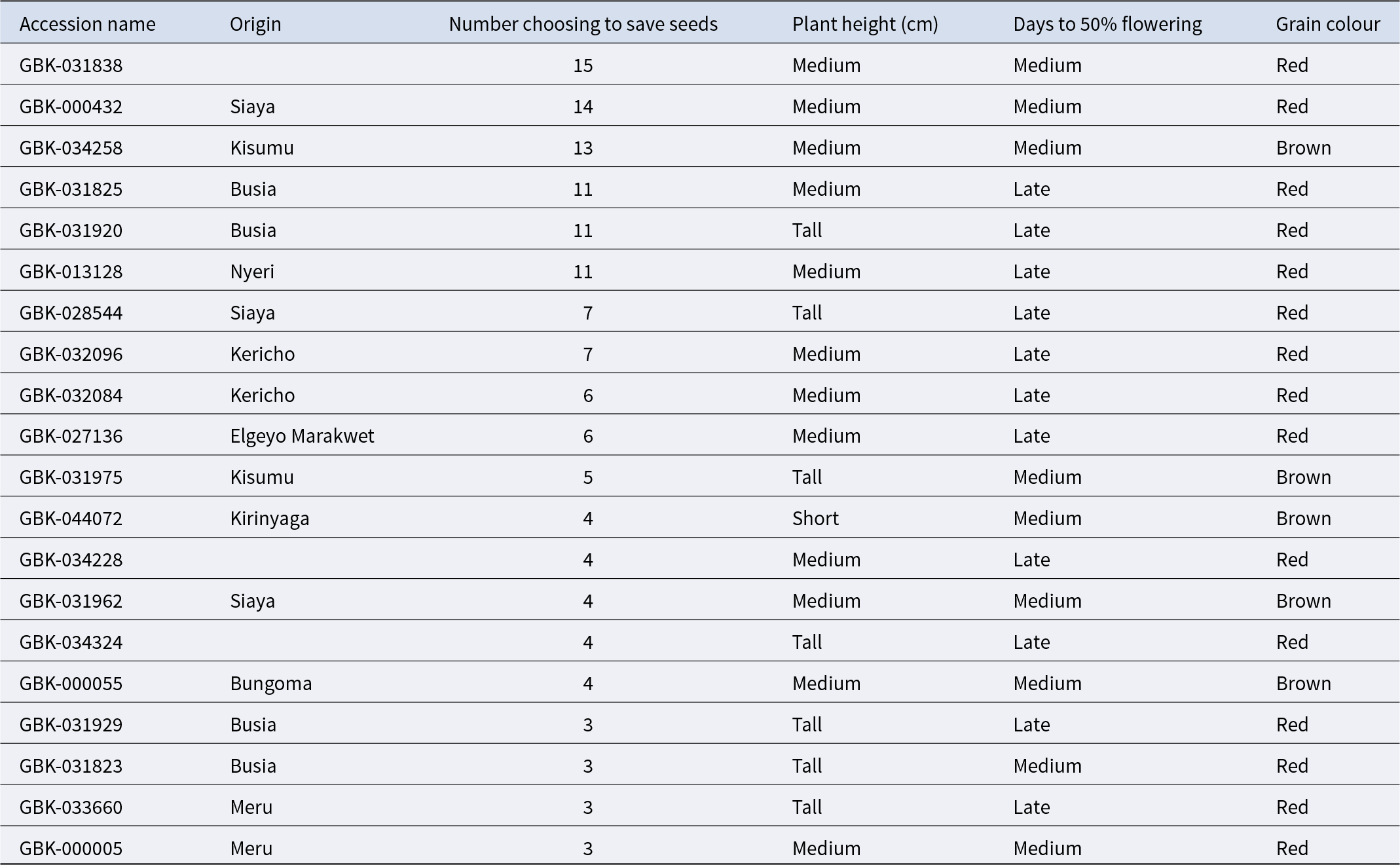

Farmers preferred red sorghum varieties principally because they are not attacked by birds and provide better cooking quality particularly when sorghum flour is mixed with cassava and maize flour. Although most of the accessions evaluated by the farmers in different locations were different, there were also some common entries. Some of the common accessions such as GBK 000055 were selected across the different locations indicating their superior performance in different agro-ecological zones (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Most popular accessions selected by farmers in 3 locations namely Kibos (n = 30), Samanga (n = 47) and Kakamega (n = 49).

Tools used in assembling germplasm subsets

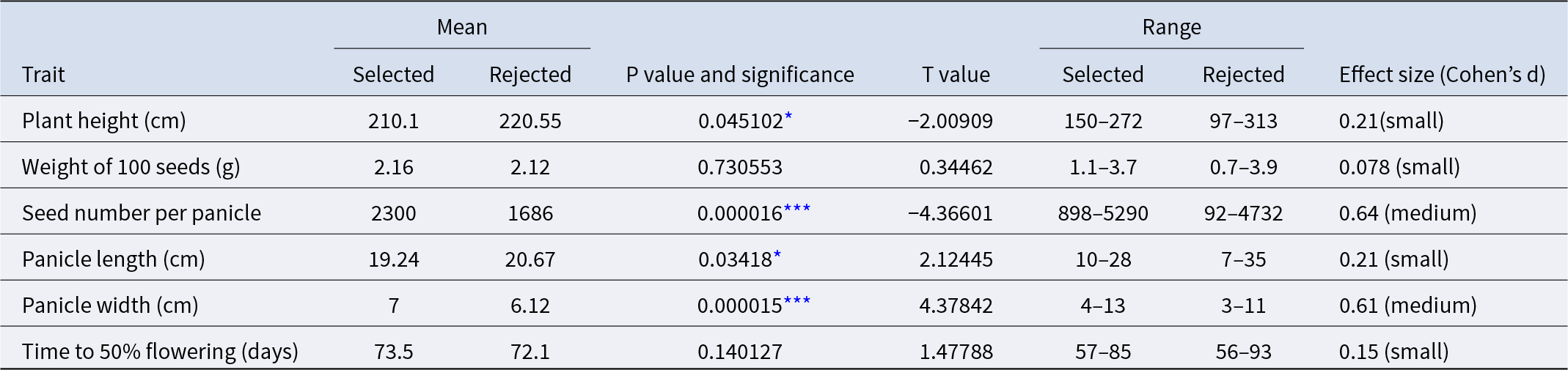

We analyzed various tools used in assembling subsets of accessions for further evaluation by GUGs. First, we sought to understand the value and usefulness of agro-morphological data in identifying germplasm subsets that are likely to include promising accessions possessing farmer-preferred traits. We have used agro-morphological characterization data collected using IPGRI descriptors to analyze differences between the accessions selected by farmers and those that were not selected during PVS. We analyzed the selected and rejected accessions based on the means of the various traits to understand whether there were any significant differences between the two categories of accessions. MANOVA revealed a significant multivariate effect of selection status (Wilks’ λ = 0.863, F (6,175) = 4.65, p < 0.001), indicating that selected and non-selected accessions differ significantly in their combined trait profiles.

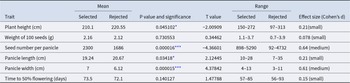

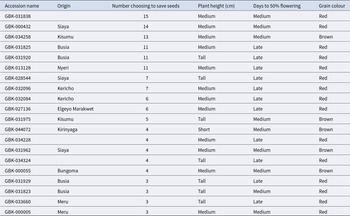

Results of univariate analysis revealed significant differences between the selected and non-selected accessions for plant height, seed numbers per panicle and panicle length and width (Table 2 and Fig. 5). Selection favoured sorghum accessions that were shorter in plant height, had shorter and wider panicles and with more seeds per panicle, while differences in seed weight and flowering time were small and not significant (Fig. 5). Apart from panicle width, the selected accessions had a narrow range for all the other studied traits compared to the non-selected ones (Table 2). The largest differences between the selected and rejected accessions as assessed using the Cohen’s d test were observed for seed number per panicle (d = 0.64, medium) and panicle width (d = 0.61, medium), while the other traits showed small effects (d ≤ 0.21) (Fig. 5). In addition to the use of agro-morphological characterization data, passport data was also used in assembling germplasm subsets. During PVS, farmers selected accessions from 13 different Counties within Kenya, indicating wide eco-geographical representation. However, the origin of 23 accessions was not known (Table 3).

Table 2. Agronomic trait means, range and significance of differences for accessions selected and rejected by farmers during PVS

*,**,*** Significance levels: 0.05*, 0.01** and 0.001***.

Figure 5. Comparison of traits between selected and rejected accessions. Left panel shows mean values of traits in selected vs. rejected accessions. Mean values are shown in log scale for visibility; Significance levels p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***), ns = not significant. Right panel shows Cohen’s d values (±95% CI) indicating the magnitude of differences (small ≈ 0.2, medium ≈ 0.5, large ≥ 0.8).

Table 3. Accessions that farmers most frequently selected in farmer-managed trials in Busia and Siaya

Accessions selected in farmer-managed evaluations/testing

The test kits of the sorghum accessions that were selected during PVS were provided to 514 households belonging to 26 farmer groups and community-based organizations. The kits were allocated randomly to the participating farmers, with 71% of the beneficiaries being women. Out of the 51 accessions evaluated by farmers, 46 of them were selected by at least one farmer for seed saving. While farmers mainly selected accessions from Busia and the neighbouring regions, they also selected materials from other distant regions such as Moyale, Meru and Kirinyaga some of which are more than 1000 km away (Table 3). About 62 % of the accessions selected were short or of medium height, with the large majority being medium statured. A total of 58% of the accessions selected by farmers belonged to either the early or medium maturity classes, with the majority being mid maturing. A total of 74% of the accessions were red sorghum accessions while the rest had brown panicles (Table 3).

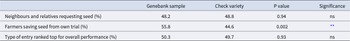

Farmers reported that the tricot approach used in farmer-managed evaluation was an exciting model that stimulated interaction and engagement between the farmers and resulted in greater sharing of crop diversity. Since farmers were provided with different sets of accessions, they were excited to visit each other and discuss how the different accessions were performing thereby encouraging farmer-to-farmer seed exchange. On the performance of the accessions tested, it was interesting to note that the majority of the farmers reported that at least one of the genotypes they had received had met their preferences and varietal needs, and they therefore saved seeds from at least one of them for planting during the next planting season. One of the traits that was found in some of the evaluated accessions was tolerance to Striga. About 56% of the farmers reported that they would save seeds of a genebank sample compared to 45% who preferred to save seeds of the check variety. The overall performance between the genebank samples as assessed by farmers was comparable to that of the check variety, with both averaging about 50% (Table 4). Overall performance in this context refers to the farmer’s holistic judgement of how a variety performs, based on an integrated evaluation of different aspects such as yield potential, resilience, maturity, grain quality and other characteristics important to local production and household use.

Table 4. Indications of farmers’ interest in genebank samples in comparison to the check variety in on-farm evaluation trials

** ns = not significant; ** = p < 0.01.

A total of 8 feedback meetings involving 12 GUGs were held. During these farmer feedback meetings, farmers reported that the decentralized and highly participatory approach used in enhancing their varietal diversity was useful as it enabled them access to new crop diversity that is suitably adapted and possesses key farmer-preferred traits. The GUGs made various suggestions on the strategies they intended to use to ensure that the seeds accessed from the genebank could be maintained within the group and also to reach a greater number of farmers. These mainly included sharing seeds with new members within and outside the GUGs, and plans to establish demonstration plots of farmer-preferred accessions. The demonstration plots would help to promote the genetic materials obtained from the national genebank and also to assist in sharing with other farmers in the community. About 83% of the farmers reported that neighbouring farmers and relatives had visited their farms during the season and requested seeds from the genetic materials they were evaluating. About 48% of these farmers actually requested seeds of the genebank samples (Table 4). Four groups reported that they had already convened meetings to facilitate seed exchange in which beneficiaries of the sorghum seed kits had been asked to invite their neighbours who had requested for seeds from them. For example, in SEHA GUG in which 25 members had benefited from the seed kits, a meeting was convened where 13 new beneficiaries were given their preferred genotypes. This indicates that nearly 50% of the farmers in this GUG shared seeds with their neighbours and relatives, demonstrating the multiplier effect of farmer-to-farmer seed exchange in rapidly spreading varieties beyond the initial recipients. Farmers reported that some of the varieties were bitter and therefore had low palatability, thereby underscoring the need for cooking and palatability tests to complement agronomic evaluations. Such feedback was important as it provided useful information to guide genebank staff in selecting suitable germplasm subsets for further evaluation by GUGs. During these feedback meetings, farmers also requested seeds of other crops, particularly finger millet, which is an important crop in the area preferred for its climate resilience.

Discussion

Linkage between genebank and germplasm users

Due to the large species and ecotypic diversity available in many national genebanks, their collections hold great potential for supporting farmers in their crop and varietal diversification efforts for sustainable agri-food systems. Kenya’s national genebank exemplifies this potential, with an exceptionally rich collection of more than 51,000 accessions representing close to 2,000 plant species. However, due to the limited engagement between national genebanks and farmers (Engels and Ebert Reference Engels and Ebert2021), this potential has largely been unexplored and unexploited. This limited engagement between national genebanks and farmers can be attributed to a variety of factors, key among them being (1) the limited information about potential genetic value of genebank collections and specifically about specific accessions that may be of value or interest to farmers; (2) challenges in enabling farmers’ access to a wide range of germplasm to respond to their diverse interests, in terms of varietal needs, preferences and production contexts and (3) limited seed quantities per accession that genebanks typically conserve and that make it impractical to share sufficient amounts for farmers to sow even small plots to evaluate. Traditionally, national genebanks have mainly provided germplasm to plant breeders. However, the lack of breeding programmes for some crops particularly the neglected and underutilized crops, which are poorly served by the formal seed sector (Ndlovu et al. Reference Ndlovu, Scheelbeek, Ngidi and Mabhaudhi2024), have hampered utilization of conserved germplasm. Additionally, where such breeding programmes exist, they focus in some cases on particular agro-ecologies and variety types. The net effect of this is that we have national genebanks holding rich crop diversity but with minimal use in addressing the diverse varietal needs of farmers. For example, out of the 6,418 sorghum accessions conserved at GeRRI, only 791 have been distributed to various users over the past decade (GeRRI 2025).

With the increased questioning of the rationale of continued funding of germplasm repositories that demonstrate little or no use of conserved germplasm, there is a need for forging more strategic and structured linkages with farmers and other users, in particular plant breeders, to spur germplasm utilization (Stoilova et al. Reference Stoilova, van Zonneveld, Roothaert and Schreinemachers2019). Consequently, in this project, one of the key activities was the development of linkages between the Kenyan national genebank with organized farmer groups and other stakeholders through GUGs (Table S1). Since the sorghum value chain is relatively poorly developed, farmers were reluctant to engage in sorghum production unless they were assured of a market for their produce. This informed the engagement with various sorghum value chain actors such as marketers and aggregators (Fig. 2). This engagement helped strengthen collaboration between the genebank and private sector organizations which traditionally has been poor (Goritschnig et al. Reference Goritschnig, Pagan, Mallor, Thabuis, Chevalier, Hägnefelt, Bertolin, Salgon, Groenewegen, Ingremeau, Santillan Martinez, Lehnert, Keilwagen, Burges, Budahn, Nothnagel, Lopes, Allender, Huet and Geoffriau2023). Through the GUGs, the national genebank was able to link the farmers with East African Breweries and other markets thereby assuring them of a ready market. Value chain actors play an important role in trait prioritization in crop and varietal diversification, and breeding programmes (Yila et al. Reference Yila, Sylla, Traore and Sawadogo-Compaoré2024). One of the key lessons learnt was that in order to be successful, efforts aimed at varietal and crop diversification should be followed by relevant interventions in value chain development. This enhanced engagement with users has potential for transforming national genebanks from largely quiet and dormant centres (McCouch et al. Reference McCouch, McNally, Wang and Sackville Hamilton2012) that they have traditionally been, to vibrant conservation, research and information hubs playing diverse roles (Wambugu et al. Reference Wambugu, Nyamongo and Kirwa2023). Under the GUG model, Kenya’s national genebank has assumed the role of facilitating germplasm use rather than just being a passive provider of genetic resources (van Etten et al. Reference van Etten, de Sousa, Cairns, Dell’Acqua, Fadda, Guereña, Heerwaarden, Assefa, Manners, Müller, Enrico, Polar, Ramirez-Villegas, Øivind Solberg, Teeken and Tufan2023). This strengthened user engagement offers genebanks a path towards achieving greater impact through enhanced agricultural production, environmental sustainability and livelihood options. The identification and sharing of promising genebank accessions possessing key farmer-preferred and climate-adaptive traits originating in different agroecosystems can improve the resilience and adaptation of agricultural production systems facing new challenges due to climate change. The identification of Striga tolerance in some of the genotypes significantly enhanced the capacity of farmers to fight Striga which remains a major challenge in sorghum production in western Kenya. One of the outputs of this study is the development of a participatory pathway that enables farmers to directly access and benefit from genebank diversity (Fig. 1).

Approaches used in assembling diversity subsets

Identifying specific genotypes to address the diverse and changing needs of farmers remains one of the greatest challenges facing genebanks globally (Haupt and Schmid Reference Haupt and Schmid2020). This study used both characterization and passport data in assembling the diversity sets for PVS. Results of MANOVA demonstrate that farmer selection was non-random, as it resulted in accessions with significantly different trait profiles. The significant differences between selected and non-selected accessions for certain farmer-preferred traits indicate how characterization data can provide a useful starting point for the identification of germplasm subsets for further evaluation by farmers (Table 2 and Fig. 5). The narrow trait range in maturity, plant height, panicle length, seed number and weight of 100 seeds between selected and non-selected accessions indicates that these traits are an important selection criteria and farmers were very specific in their selection. However, the lack of significant differences between selected and non-selected accessions for time to 50% flowering (Table 2 and Fig. 5) suggests that farmers’ selection of preferred genotypes involves complex decision making. This shows that farmers selected particular varieties that did not exhibit the best performance for the top-ranked selection criteria but rather for a combination of lower-ranked criteria and other considerations. Similar findings were made by Ishikawa et al. (Reference Ishikawa, Drabo, Batieno, Muranaka, Fatokun and Boukar2019). The failure by farmers to select the earliest maturing accessions in favour of the mid maturing ones further supports this observation (Fig. 3). Similarly, our finding of insignificant differences between selected and rejected accessions for 100 seed weight (Table 2 and Fig. 5), a key yield component, corresponds with reports of other crops where farmers gave less preference to yield and yield components in favour of other traits (Ishikawa et al. Reference Ishikawa, Drabo, Batieno, Muranaka, Fatokun and Boukar2019; Marenya et al. Reference Marenya, Wanyama, Alemu, Westengen and Jaleta2022). However, the significant differences based on seed numbers between selected and non-selected accessions, another yield component, seem to contradict this proposition. It can therefore be argued that farmers consider some yield components to be more important than others. This is consistent with farmers selection criteria indicated in Table 1 which shows that 63% of the farmers preferred large panicles compared to 23% who selected large grains, indicating that the majority of the farmers gave more priority to panicle size rather than grain size. This could also be attributed to the negative correlation between seed weight and seed number (Lázaro and Larrinaga Reference Lázaro and Larrinaga2018). These findings underscore the need for access to diverse germplasm from multiple genetic backgrounds during participatory selection and evaluation in order to broaden the potential trait range that farmers can evaluate.

While characterization data is an important resource for supporting targeted selection of promising accessions, it also presents major challenges. First, a large proportion of genebank collections lack comprehensive agro-morphological characterization data. Out of 6418 sorghum accessions, only 3864 have varying levels of characterization data. Secondly, where this data exists, it is often collected in a single season and location, thereby providing unreliable information about traits for which genotype by environment (GXE) interactions are important (McCouch et al. Reference McCouch, McNally, Wang and Sackville Hamilton2012; Anglin et al. Reference Anglin, Amri, Kehel and Ellis2018). Furthermore, whereas genebanks mostly collect data from a limited number of highly heritable traits, many traits of importance to farmers are quantitative in nature and thus highly influenced by the environment. It is therefore especially important for traits exhibiting important GXE interactions that farmers evaluate new accessions in their own fields under their own management. In many cases, the collection of characterization data across seasons and sites lacks consistency making it a difficult to objectively compare the data and efficiently select promising materials. Similarly, passport data is usually incomplete, and the majority of the older accessions usually lack accurate geo-reference data. Advances in genomics are providing powerful tools to address these challenges. Genetic diversity analysis, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) (Li et al. Reference Li, Gates, Buckler, Hufford, Janzen, Rellán-Álvarez, Rodríguez-Zapata, Romero Navarro, Sawers, Snodgrass, Sonder, Willcox, Hearne, Ross-Ibarra and Runcie2025), genomic prediction models and targeted gene mining can greatly accelerate assembly of subsets with useful traits for further evaluation by farmers. Unfortunately, many national genebanks, including the Kenyan national genebank lack capacity to undertake such molecular analysis. This requires collaboration with the germplasm user community. Climate matching and eco-geographical modelling tools present an important approach to complement the use of passport data in helping predict potential adaptability of accessions under current or future climates. The heterogeneity present in some genebank samples (Anglin et al. Reference Anglin, Amri, Kehel and Ellis2018), although possibly posing a challenge for farmer observation, could offer opportunities for farmers interested to select individual plants for further observation and use.

Sourcing genetic materials from diverse geographical origins can be important for climate adaptation based on suggestions that germplasm adapted to future climate changes may likely be one obtained from contrasting provenances, including geographical areas that are quite distant (Bellon et al. Reference Bellon, Hodson and Hellin2011; Sgrò et al. Reference Sgrò, Lowe and Hoffmann2011; Mokuwa et al. Reference Mokuwa, Nuijten, Okry, Teeken, Maat, Richards and Struik2013). For example, selecting accessions collected from dry areas has been shown to increase chances of identifying materials with drought tolerance (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Gong, Guo, Ren, Xu and Ling2011). Our results from both on-station and on-farm evaluations show that farmers selected accessions from very distant geographic origins (Table 3), sometimes more than 1000 km apart and which have markedly different climatic conditions. These results confirm that facilitating farmers’ access to genebank accessions sourced from wide eco-geographical ranges may be useful. Through Focused Identification of Germplasm Strategy (FIGS), passport data is finding great application in assessing the value of genebank accessions by linking it with agro-climatic data (Bari et al. Reference Bari, Street, Mackay, Endresen, De Pauw and Amri2012; Khazaei et al. Reference Khazaei, Street, Bari, Mackay and Stoddard2013; Stenberg and Ortiz Reference Stenberg and Ortiz2021). Passport data of accession origins can therefore be highly useful in assembling subsets that provide diversity for adaptive traits.

Key lessons learnt

This study has explored the joint learnings of the GUG approach where the genebank and farmers have acted as agents of change in varietal diversification efforts. During the GUG activities, farmers showed great interest and excitement in selecting and evaluating the great sorghum diversity that is conserved at the genebank. This indicates that genebanks are a valuable partner in farmers’ efforts to enhance their climate resilience capacity through access to new and adapted germplasm for improved food and nutritional security. In addition, this activity has clearly demonstrated that farmers possess great knowledge on their crops and their varieties and have a clear understanding of their seed and varietal needs and preferences. Farmers are able to clearly articulate their trait preferences. This information may be of great value in supporting targeted utilization of genebank seed collections. The study also shows that genebanks hold useful diversity for climate resilience, with some accessions performing well across different locations (Fig. 4) and others outperforming the check variety.

Placing farmers at the centre of the variety selection and evaluation process helps them to share their views, insights, concerns, perspectives and interests and creates a sense of ownership over the process. To achieve this, this activity has demonstrated that working with existing farmer groups with established leadership and governance structures provides an easy and quick entry point for genebanks to reach a large number of farmers. These groups foster continued learning, sustained interaction with genebanks and enable targeted access to new genetic diversity thus enhancing farmers’ capacity to respond to changing biotic and abiotic environment. This agrees with findings of other studies that farmers belonging to farmer groups have better chances of accessing and sharing introduced crop diversity (Otieno et al. Reference Otieno, Ogola, Recha, Mohammed and Fadda2022). Existing groups have demonstrated great commitment and cohesion among the members. Working with existing farmer groups reduced the costs and efforts associated with the establishment of GUGs thus enhancing cost effectiveness, sustainability and scalability. The major support provided to the GUGs was provision of seeds and training both of which lie within the mandates of national genebanks and their partners such as universities, making this approach highly feasible.

The GUG model has great potential for enhancing farmer-to-farmer seed exchange, which is an important strategy towards ensuring the germplasm remains within the GUGs and reach a large number of farmers (Table 4). A study conducted to assess the impact of this approach showed that on average, the farmers who benefited from the seed kits shared the seeds with 4 other farmers (Heaton et al. Reference Heaton, Jamora, Asamoah, Demie, Oladimeji, Mwansa and Recha2025). This is greatly aided by the crowdsourcing and citizen science approaches used in this study which enable the active participation of a great number of farmers (van Etten Reference van Etten2011). The tricot approach is becoming increasingly popular due to its scalability and ability to capture climatic variation. It has been used to collect data from close to 12,500 trial plots of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Nicaragua, durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) in Ethiopia and bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in India (van Etten et al. Reference van Etten, de Sousa, Aguilar, Barrios, Coto, Dell’Acqua, Fadda, Gebrehawaryat, van de Gevel, Gupta, Kiros, Madriz, Mathur, Mengistu, Mercado, Nurhisen Mohammed, Paliwal, Pè, Quirós, Rosas, Sharma, Singh, Solanki and Steinke2019). In order to support the maintenance of the diversity within groups and ensure sustainability of seed exchange, this study improved the capacity of farmers to maintain, select, save and exchange quality seeds through training on seed production and management. With such human and technical capacity building, small-scale farmers have been shown to have capacity in producing quality seeds and in the process enhancing their economic livelihoods (Kansiime et al. Reference Kansiime, Bundi, Nicodemus, Ochieng, Marandu, Njau, Kessy, Williams, Karanja, Tambo and Romney2021; Wanyama et al. Reference Wanyama, Mvungi, Luoga, Mmasi, Zablon, N’Danikou and Schreinemachers2023). The major strengths of the GUG approach used here is that it enhances the relevance and adoption of genetic resources by aligning them with farmer needs, promotes in situ conservation of agrobiodiversity, strengthens farmer-managed seed systems, captures diverse user preferences and supports inclusive, decentralized decision-making in crop and varietal diversification. Farmers were significantly more likely to save seed from genebank accessions compared to the check variety (Table 4). Farmers have reported that this approach greatly increased their understanding of the role of the genebank and assisted them to access useful crop diversity (Heaton et al. Reference Heaton, Jamora, Asamoah, Demie, Oladimeji, Mwansa and Recha2025). The request for seeds of other crops during the feedback meetings points to the effectiveness of this approach.

Conclusion and recommendation

This study has demonstrated that participatory selection and farmer-managed evaluations of genebank accessions provide a feasible and powerful pathway through which farmers can discover and access the otherwise ‘hidden’ diversity conserved in genebank seed collections. The great interest expressed by farmers on accessing and evaluating genebank materials indicates that genebank collections are useful resource for diversifying crop and varietal options, supporting farmers to modify and adapt their farming systems in response to evolving climate change and other biotic and abiotic challenges. In order to empower farmers and enable them to diversify and adapt their cropping systems through access to new diversity, there is need to ensure sustained engagement between farmers and genebanks than the current largely ad hoc collaboration. This sustained engagement could include scaling of the GUG activities to focus on facilitating access to new crop diversity by other farmer groups and regions as well as targeting other crops. This scaling could also include (1) strengthening genebank’s capacity and role in providing diversity sets for specific farmer groups, NGOs and breeders working with farmers who seek to diversify their crop and varietal options and (2) NGOs, research institutes and other partners taking on more responsibilities as intermediaries between GeRRI and other national genebanks in requesting germplasm access and other services. The national genebank could play a facilitative role in enhancing access to diversity by identifying useful germplasm subsets while the role of coordinating the evaluation can be conducted by CBOs, NGOs and development partners.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479262125100452.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the invaluable technical support of the Crop Trust team under the Seeds for Resilience Project. We thank the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) for providing institutional and logistical support, and our field staff for their assistance in data collection. The great contribution by the farmers, extension service and other partners who participated in our germplasm user group activities is gratefully acknowledged. Figure 2 was generated using ChatGPT Version 5.0.

Funding statement

This work was supported by KfW Development Bank through the Global Crop Diversity Trust under the Seeds for Resilience Project (SFR).

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.