Introduction

CHD encompass structural abnormalities in the heart present at birth, affecting structure, function, and blood flow. Critical CHD, severe conditions necessitating early intervention, comprise a significant subset. Reference Blue, Ip and Troup1 While genetic factors contribute, the aetiology of many CHDs remains unknown, with environmental factors playing a role. Reference Botto, Lin, Riehle-Colarusso, Malik and Correa2 Reproductive and parental factors, along with exposure to pollutants, are associated with increased CHD risk. Reference Chen, Zmirou-Navier, Padilla and Deguen3

While previous studies explored the link between environmental pollutants and CHDs, evidence supporting the association with more critical types of CHDs is less consistent. Studies by Buteau et al. and Stingone et al. found positive associations between fine particulate matter (<2.5 micrometers in diameter) exposure and certain critical CHDs, while Tanner et al. demonstrated elevated risks for critical CHDs with increased pollution exposure. Reference Buteau, Platt and Auger4–Reference Stingone, Luben and Daniels6 However, two systematic reviews yielded inconclusive evidence. Reference Chen, Zmirou-Navier, Padilla and Deguen3,Reference Hall and Robinson7 Nitrogen dioxide exposure, explored in three reviews, showed consistent association with coarctation of the aorta, but mixed findings for associations with other critical CHDs. Reference Stingone, Luben and Daniels6,Reference Vrijheid, Martinez and Manzanares8,Reference Dadvand, Rankin, Rushton and Pless-Mulloli9 Ozone exposure, particularly during the second and third trimesters, is linked to heightened risk of CHD overall and of specific cardiac anomalies. Reference Vrijheid, Martinez and Manzanares8–Reference Ritz, Yu, Fruin, Chapa, Shaw and Harris10 A case-control study on black smoke exposure reported a weak association with cardiac chamber malformations. Reference Dadvand, Rankin, Rushton and Pless-Mulloli11

These diverse outcomes underscore the complex nature of the potential relationship. Our study aimed to contribute nuanced, spatially informed insights to this ongoing discourse, particularly regarding the critical CHDs that hold significant clinical importance.

Materials and methods

Data collection and preparation

Data from the prospective Registry of the Complex Pediatric Therapies Follow-up Program included 1,484 patients diagnosed with critical CHD from September 1996 to November 2021 at the referral cardiac centre, Stollery Children’s Hospital, Edmonton, Canada. These patients underwent surgery in early infancy, with cardiopulmonary bypass performed within 6 weeks of birth, cardiac shunts placed up to 6 months of age, or repair of isomerism defects up to 1 year of age. The Registry recorded acute care details and long-term follow-up outcomes for all these children undergoing surgery or interventions for critical CHD at Stollery Children’s Hospital since the programme’s inception in 1996. Reference Robertson, Sauve and Joffe12

To ensure accurate classification of critical CHD cases, Botto et al.’s Level 3 classification system was used. The categories included: (1) Conotruncal, (2) Anomalous pulmonary venous return, (3) Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, (4) Right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, (5) Heterotaxy, and (6) Complex. In addition, a reference category (7) was created for this study to capture cases with known chromosomal abnormalities (excluded from Botto’s original classification). Reference Botto, Lin, Riehle-Colarusso, Malik and Correa2 By selecting this reference category to assess the relative impact of air pollutant exposures on critical CHD, we reasoned that the comparison groups were more homogeneous in terms of underlying known genetic predispositions. This approach allowed the study to more specifically explore the interaction between air pollutant exposure and genetic factors in influencing critical CHD risk. Cases of CHD excluded from Botto’s system included those with vascular anomalies, isolated valve dysplasias, arrhythmias, atrioventricular septal defects, and simple septal defects, as these were considered non-critical CHDs.

To characterise the population distribution within our cohort, we used postal codes as geographical identifiers. Given that fetal heart development begins approximately three weeks post-fertilisation and is largely complete by the end of the eighth week of pregnancy, Reference Tan and Lewandowski13 we specifically linked postal codes from the first and second months of pregnancy to exposure data on ambient and industrial air quality. Measurements of key air pollutants included ozone (2002–2015), 14–Reference Robichaud, Ménard, Zaïtseva and Anselmo16 ground-level fine particulate matter (<2.5 micrometers in diameter; 2000–2012), 14,Reference van Donkelaar, Martin, Li and Burnett17 nitrogen dioxide (1984–2016), 18,Reference Hystad, Setton and Cervantes19 and air quality from smoke (2010–2019). Reference Paul, Yao, McLean, Stieb and Henderson20 Air quality from smoke was a variable generated by the Canadian Optimized Statistical Smoke Exposure Model, which employs a machine learning approach to estimate daily exposure to wildfire-specific fine particulate matter on a national scale. Reference Paul, Yao, McLean, Stieb and Henderson20 The other pollutant data were obtained from land use regression models developed by the Canadian Urban Environmental Health Research Consortium. 21 These pollutants were selected as monthly exposure levels were available, whereas other pollutants were available only annually. These estimates relied on data from the National Air Pollution Surveillance Program and various satellite instruments. 22 Missing data for any variable were not imputed.

The dataset included demographic information, including sex, rural-urban status, and birth gestational age. Only sex was included as a confounding factor in the models. Rural-urban status was not included because it was indirectly captured through postal codes, and birth gestational age was not included because fetal heart formation is typically completed by the eighth week of pregnancy.

Statistics

To investigate the relationship between air pollution exposure and critical CHD categories, we initially employed multinomial logistic regression. Sex was included as an independent variable to address potential confounding, and the model is represented as:

To address spatial variations that may be overlooked by multinomial logistic regression, we extended our analysis using geographically weighted multinomial logistic regression. This spatial regression technique estimates location-specific coefficients, allowing the relationship between predictors and outcomes to vary geographically across the study areas. A Gaussian kernel function was applied to assign spatial weights, giving greater influence to observations closer to the kernel centre. The kernel bandwidth was determined using a rule-of-thumb approach, set to approximately one-third of the kernel width (6σ) to cover 99.7% of the data under a normal distribution. Based on a longitude standard deviation of 7.88357 degrees, this yielded a fixed bandwidth of approximately 1208 km at the study area’s mean latitude (52.35686 degrees). This approach balanced model complexity with spatial resolution.

To address collinearity among independent pollution variables, separate models were constructed for each air pollutant, stratified by sex. Data from the first and second months of pregnancy were combined, as pollutant levels during these periods were similar and yielded consistent results.

If we let Y represent the dependent variable representing critical CHD categories, and X 1, X 2,…,Xk represent the independent variables (including air pollution exposures and sex), the geographically weighted multinomial logistic regression model is mathematically represented as:

Here, i represents the category of critical CHD, K denotes the reference category (cases with known chromosomal abnormalities), s denotes the geographic location of each observation, and the coefficients β i0(s), β i1(s), β i2(s), …, βi k(s) are the location-specific coefficients for the intercept and independent variables. This model relates the logit of the probability of belonging to category i versus K to a spatially varying linear combination of independent variables. Local standard errors and odds ratios were calculated for each coefficient to evaluate the statistical significance of the predictors and to interpret their influence on the likelihood of different critical CHD categories.

Geographically weighted models estimate coefficients using information from neighbouring locations, meaning the results at each location are not independent tests. This spatially weighted nature of the model reduced the risk of false positive statistically significant findings that typically arise when conducting multiple independent statistical tests across many locations. We focused on regional clusters of neighbouring locations that demonstrated consistent and statistically significant associations with pollutant exposures and critical CHD categories, rather than isolated points.

Model fit evaluation

The model fit was evaluated using McFadden’s R-squared for multinomial logistic regression, while geographically weighted multinomial logistic regression required focusing on local pseudo-R-squared values to account for spatial variation. These values, calculated for specific geographic regions, highlighted areas where the model fit the data well. Mapping local pseudo-R-squared values revealed clusters of higher model fit, indicating regions where the relationship between air pollution and categories of critical CHD was better captured.

Spatial visualisation

To explore spatial patterns and variable relationships further, we created Geographic Information System-based two-dimensional maps showing odds ratios and p-values, with p-value ≤0.05 accepted as statistically significant. These visualisations, overlaid with the locations of study participants and pollution monitoring stations, provided a comprehensive view of both the spatial distribution of pollutant exposure and its relationship with critical CHD incidence, and highlighted regions of significant localised association.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval for The Registry and Follow-up of Complex Pediatric Therapies was obtained from the biomedical Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta, project number Pro00001030, legacy study #4513, with current renewal expiry date August 23, 2025.

Patient consent statement

All parents or guardians signed written informed consent for registration (which included consent for data collection and long-term follow-up). All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as most recently amended.

Results

Descriptive results

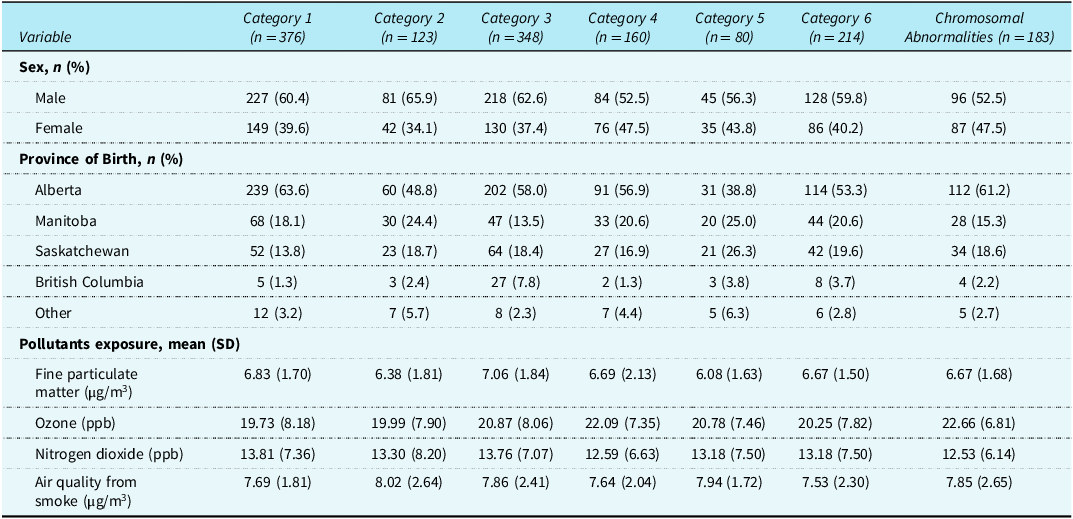

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the included 1484 patients diagnosed with critical CHD. Of these patients, 183 (12.3%) had known chromosomal abnormalities and were assigned to the reference category. The remaining 1301 patients were classified into one of the six Botto critical CHD categories. Reference Botto, Lin, Riehle-Colarusso, Malik and Correa2 The cohort had 60% male and 40% female patients, with most born at gestational age ≥37 weeks. Alberta was the most common province of early pregnancy exposure (57%), followed by Manitoba (18%) and Saskatchewan (18%). Table 1 also presents the mean and standard deviation of air pollutants, including nitrogen dioxide, ozone, fine particulate matter, and air quality from smoke, stratified by critical CHD Botto category and reference category (patients with known chromosomal abnormalities).

Table 1. Characteristics of patients diagnosed with critical CHD, by Botto classification category

PPB = parts per billion; SD = standard deviation.

Ground level fine particulate matter association with critical CHD categories

In the conventional multinomial logistic regression model, ground-level fine particulate matter exposure was not statistically significantly associated with critical CHD categories (compared to the known chromosomal abnormality reference category) (Likelihood Ratio chi-squared = 20.37, degrees of freedom = 12, p = 0.0604). The low pseudo-R-squared value (0.0444) indicated very limited influence on critical CHD outcomes.

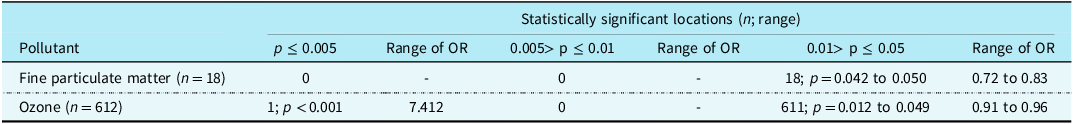

In geographically weighted multinomial logistic regression, only 0.34% (n = 18/5247) of locations showed statistically significant associations between fine particulate matter exposure and critical CHD categories, after adjusting for sex (Figure 1), and all of these locations were associated with odds ratios below 1 (Supplementary Figure S1). Among these, ten locations were associated with Botto category 1 (conotruncal CHD), primarily in Saskatchewan, while the remaining eight locations were associated with Botto category 4 (right ventricular outflow tract obstruction), mostly observed in Manitoba. The geographic extent of these significant areas was small—the cluster in Saskatchewan spanned approximately 166 km in longitude and 184 km in latitude, and the Manitoba cluster covered about 22.2 km by 23.8 km. The p-value ranges for the 18 statistically significant locations are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1. Exploring the impact of fine particulate matter exposure on the incidence of critical congenital heart disease categories 1 to 6 compared to the reference group with chromosomal abnormalities, accounting for spatial variability and adjusting for sex. Blue: statistically significant, Red: statistically non-significant. From top left to right: Botto categories 1, 2, and 3. From bottom left to right: Botto categories 4, 5, and 6.

Table 2. Statistically significant locations with an association with critical CHD categories

OR = odds ratio in geographically weighted multinomial logistic regression model, adjusted for sex.

Ozone association with critical CHD categories

Multinomial logistic regression found a statistically significant association between ozone and critical CHD categories compared to the chromosomal abnormality critical CHD reference category (Likelihood Ratio chi-squared statistic of 23.07, degrees of freedom 12, and p-value of <0.0271). The low pseudo-R-squared value (0.0080) indicated that the model explained only a small portion of the variability in outcome. Higher ozone exposure was significantly associated with lower odds of having Botto category 1 (conotruncal CHD, p = 0.003), category 2 (atrioventricular septal defects, p = 0.026), and category 6 (right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, p = 0.021), compared to the reference chromosomal abnormalities category.

In the geographically weighted multinomial logistic regression analysis, 15.1% of the examined locations (n = 612/4064 locations) had statistically significant p-values, indicating spatial variation in the relationship between ozone exposure and critical CHD category incidence (Figure 2). All but one of these locations with significant p-values had odds ratios below 1 (Supplementary Figure S2). The majority of these locations (86%) were in Alberta, while <10% were located in Saskatchewan. After spatial adjustment with geographically weighted multinomial logistic regression, in Alberta, most locations (65%) were associated with category 6, and the remaining 35% were associated with category 1 critical CHD. In Saskatchewan, significant locations were predominantly associated with category 1 (88%), and the remaining 12% associated with category 6 critical CHD. The p-value ranges for the 612 statistically significant locations are shown in Table 2.

Figure 2. Exploring the impact of ozone exposure on the incidence of critical CHD categories, compared to the reference group with chromosomal abnormalities, accounting for spatial variability and adjusting for sex. Blue: statistically significant, Red: statistically non-significant. From top left to right: Botto categories 1, 2, and 3. From bottom left to right: Botto categories 4, 5, and 6.

Nitrogen dioxide and air quality from smoke association with critical CHD categories

Multinomial logistic regression found a significant association between nitrogen dioxide exposure and critical CHD categories compared to the chromosomal abnormalities reference category (Likelihood Ratio chi-squared statistic of 31.29, degrees of freedom 12, and p = 0.0018). The pseudo-R-squared value (0.0081) indicated very low explanatory power of the model. The geographically weighted multinomial logistic regression did not identify any of 4856 locations with statistically significant associations between nitrogen dioxide exposure and critical CHD categories.

No statistically significant associations were found between air quality from smoke and critical CHD categories in either the multinomial (Likelihood ratio chi-squared 11.03, degrees of freedom 12, p = 0.5266; pseudo-R-squared value 0.0041) or geographically weighted multinomial logistic regression model of 4284 locations.

Discussion

This study applied geographically weighted multinomial logistic regression to explore the association between exposure to air pollutants (fine particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and air quality from smoke) and categories of critical CHDs. The findings revealed spatial variability, highlighting potential localised mechanisms driving these associations.

Statistically significant associations were found between fine particulate matter exposure and critical CHDs in 18 locations, and between ozone exposure and critical CHDs in 612 locations. The specific critical CHD categories associated with these air pollutants differed across locations, indicating spatial heterogeneity. Identification of significant clusters (rather than isolated points) of association for fine particulate matter in Saskatchewan and Manitoba may reflect regions characterised by industrial activities such as oil and gas exploration, coal mining, and manufacturing, i.e., may underscore the relevance of localised environmental influences. This clustering pattern suggested that certain geographic areas may have heightened vulnerability to the combined effects of pollution and other local demographic and environmental risk factors on critical CHD incidence. Similarly, the spatial patterns observed with ozone-related associations emphasised the complex, region-specific interactions between environmental exposures and critical CHD risk.

Interestingly, nearly all significant locations reported odds ratios below 1, which contrasts with findings from other studies. Reference Chen, Zmirou-Navier, Padilla and Deguen3–Reference Dadvand, Rankin, Rushton and Pless-Mulloli11 Although odds ratios below 1 are typically interpreted as protective effects, we believe this result was more likely due to methodological factors influencing interpretation of the results, rather than a true protective effect of pollution exposure. Specifically, the use of critical CHD cases with known chromosomal abnormalities as the reference category in our analysis likely strongly influenced interpretation of the results. Based on this, we propose that interpretation of our findings may be one of the following:

-

1. Pollution reduced the risk of critical CHD in several locations. We consider this interpretation unlikely given previous evidence and biological plausibility, and suggest one of the alternative explanations below as far more plausible.

-

2. Pollution acted as a “second hit” that, when combined with genetic predisposition, influenced biological pathways involved in fetal heart development and significantly increased the risk of critical CHD. This interaction between pollution exposure and genetic predisposition meant that the risk associated with pollution appeared lower in patients without genetic predisposition compared to those with genetic predisposition. We consider this the most plausible explanation. Future studies using live births without any critical CHD as the reference group, rather than those with known genetic abnormalities, would help clarify this interpretation.

-

3. The prior probability that pollution was associated with critical CHD risk was likely low, around 10%. In this case, the p-values observed in our exploratory study were not sufficiently low to confidently conclude a protective effect of pollution. For instance, with a p-value of 0.04 and a 10% prior probability, the false positive risk remained approximately 32%, making it inappropriate to interpret pollution as protective based on our results.

-

4. The finding that the associations were observed only in a minority of locations suggested the possible presence of an unmeasured confounding factor associated both with pollution levels and critical CHD risk. Therefore, the observed relationships may not be due to pollution itself, but rather driven by this unmeasured confounder.

Localised clusters with odds ratios below 1 suggested that air pollution may significantly influence the incidence of critical CHD through complex interactions involving both genetic susceptibility and environmental exposures. These interactions may vary spatially, leading to differences in observed associations across regions. This spatial variability emphasised the importance of considering local contexts when designing public health interventions and conducting further research.

This study had several strengths. First, the modest sample size and prospectively enrolled cohort. Second, the integration of air pollution data with individual-level critical CHD outcomes using high-resolution postal-code linkage. Third, the use of geographically weighted multinomial logistic regression methodology, which allowed us to examine how associations between pollutant exposure and specific categories of critical CHD vary across space, rather than assuming a uniform relationship across the study areas.

This study also had limitations. First, limitations of the geographically weighted multinomial logistic regression model. The relatively small sample size in some geographic regions may reduce the statistical reliability of findings in those areas. The model assumed spatial stationarity, but spatial relationships can be dynamic (e.g., environmental and social factors affecting health may shift over time). Individual pollutants were analysed separately to avoid multicollinearity, yet air pollutants commonly co-occur in the environment, and their combined or interacting effects may play an important role. Second, the dataset may be influenced by selection bias related to pregnancy loss, termination, or stillbirth, particularly with critical CHDs, leaving an unknown proportion of undetected cases. Third, this was an observational study and therefore cannot prove causality. There were likely important unmeasured confounding variables. This may be exacerbated by the modest sample size from a single centre, requiring repetition to ensure generalizability. Fourth, as discussed above, our reference category of critical CHD cases with known chromosomal abnormalities complicated the interpretation of results. Future research should include a reference group without any form of critical CHD.

Conclusion

This study contributed valuable insights into the complex relationship between air pollutant exposure and the incidence of critical CHDs, highlighting the importance of considering spatial variability. Despite observing significant associations between air pollutants and critical CHD categories in certain locations, the odds ratios below 1 warrant cautious interpretation and likely reflect the choice of the reference critical CHD group (those with known chromosomal abnormalities). We suggest the most reasonable interpretation of our results is that air pollution exposure acted as a second hit that, combined with genetic predisposition (affecting biological pathways involved in fetal heart development, including those influenced by air pollutants), markedly increased the risk for critical CHD. As a result, the spatially specific risk for critical CHD associated with air pollution exposure appeared lower in those patients without genetic predisposition than in those with genetic predisposition. Understanding how the relationship between air pollution and critical CHD varies spatially can help guide policymakers and healthcare practitioners in implementing strategies to reduce the burden of critical CHD in affected communities.

Future work should explore potential interactions between different pollutants and include a reference group without critical CHD to better clarify these associations. By prioritising spatially targeted approaches and addressing knowledge gaps, we can work towards mitigating the impact of environmental pollutants on critical CHD risk and improving the health outcomes for vulnerable populations.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951125111177.

Acknowledgements

We thank the children and their families for their attendance at the developmental follow-up clinic.

Financial support

The Complex Pediatric Therapies Follow-up Program, an interprovincial, multidisciplinary collaboration, has been supported by funding contributions from Alberta Health, Stollery Children’s Hospital, and Women and Children’s Health Research Institute, with ongoing funding by Glenrose Rehabilitation Hospital. These funding agencies had no role in design and conduct of the study; analysis or interpretation of data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standard

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation (Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS 2) in Canada) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and has been approved by the institutional committees (the biomedical Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta project number Pro00001030).