When did the famed German nation of poets and thinkers fall from grace? – What makes a fanatical Nazi tick? – Why did Hitler come into power? – How can we make Hans listen? – Is Germany incurable? In the early 1940s, these were no strange questions. They were not only reasonable, they were vital, a matter literally of life and death. In fact, these were the critical problems that, many were convinced, would determine the very fate of human existence and community and that required a new, just, and global kind of action, a war on National Socialism.

Yes, the harrowing battles between Allies and Axis during World War II were first and foremost fought with all available military powers, ending for Europe with Nazi Germany’s unconditional surrender. Nonetheless, after the uncomfortable yet increasingly inevitable reckoning with the catastrophic failure to accomplish a lasting peace in Europe after World War I, it became clear that a new kind of war also needed to be fought with the support of a novel, paper-based arsenal. Somebody, anybody needed to find a solution, to grasp and address the fundamental problems that could not be shot at or bombed away. What exactly made the German nation the prime aggressor to sink the world into chaos yet again? Germany, the rogue state, urgently had to be stopped, once and for all. But how? The United States as the last defender of democracy needed to come up with answers, now.

Journalists, intellectuals, academics, government officials, and military officers, they all cranked out texts about Germany at an unprecedented scale, with rare intensity and at times with surprising intellectual depth. In fact, some of the most brilliant women and men of the time put their individual research projects on hold, along with several of their usual intellectual disagreements and their often-bitter ideological differences. Instead, they banded together and pragmatically employed their intellectual capacities in the common war effort against the Nazi enemy. They did so with a paper-based arsenal, with texts, analyses, letters, reviews, fiction writing, studies, statements, memoires, intelligence reports, and memoranda. One should note that printing sheets were short in supply and there was little time for thorough editing and elaborate rewrites. For the American analysis of Nazi Germany, print publications indeed were only the tip of the iceberg, as their engaged writing mostly circulated in cheap, inconspicuous, and volatile formats such as carbon copies, handwritten notes, and mimeographs. The astonishing extent and variety of these formal and informal writings leads me to speak of a Nazi German enemy literature, a briefly flourishing genre that created some of the most important literary innovations of the times.

As one immerses oneself in the various types of writings, correspondences, applied studies, reports, and memoranda, one slowly rediscovers this US-American wartime literature on the Nazi German enemy as a captivating corpus of writing that has largely sunk into oblivion. This study therefore attempts to excavate an entire forgotten literary culture that rapidly grew in a matter of years, peaked during World War II and largely collapsed within few months following Nazi Germany’s unconditional surrender. For a fleeting moment in history, significant parts of the intellectual world in the United States converged to employ their resources for a cool-headed analysis of the Nazi threat, the clear identification of the enemy, and starting in 1944, for the elaborate planning for a postwar reeducation of the fascist, imperialist, militaristic, racist, antisemitic, xenophobic, chauvinist National Socialist German nation into a democratic ally.

In the following, I want to present this highly productive moment in the history of the United States, when Americans and European émigrés, several of which held the precarious legal status “friendly enemy alien,” worked together in the collaborative study of Nazi Germany. These collaborations first of all addressed the epochal crisis of the twentieth century, but they also created the mostly unacknowledged grounds for the intellectual revolutions of the mid-century and the rendering of modern American culture as a “model” for the rest of the world in the cultural politics of the Cold War. Nazi German Studies served as the murky, locally entangled test case and launch pad for US-American theories and practices of universalism during the Cold War such as Cold War modernism, identity politics, or the theory of social systems.

For a topic of such thrust, significance, and renewed present-day urgency, our knowledge of this historical moment is extremely fragmented.1 While several of the historical actors, that is, individuals, but also media technologies, institutions, and schools of thought, have received significant attention within their respective disciplines and fields, there is still a demand for synthetic studies of the wartime analyses of Nazi Germany that both leave room for the historical complexities of those collaborative projects situated in the 1940s US-America and yet also strive to draw these various stories together into a coherent narrative.

The American contemporary study of Nazi Germany had four distinct phases: It was first motivated by a growing, yet diffuse sense of danger starting in 1930 and then between 1933 and 1938, until the Nazi pogrom on November 9, a highly publicized media event in the United States, alarmed the American public to the violence of the Nazi regime. The period between the events of late 1938, the German attack on Polish territory on September 1, 1939, the attack on Britain after the fall of France in the summer of 1940 and the attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941 up until December 7, 1941, and the German declaration of war against the United States four days later was defined by intellectual attempts to reinforce the American public against National Socialist propaganda latching on domestic fascist tendencies, balanced on the razor-thin edge in the political struggle to keep the United States out of the war, ultimately leading to the recognition of Nazi Germany as the enemy. Between December 1941 and the summer of 1943, the analysis of Nazi Germany in the United States reached its peak with a spring tide of texts concerned with German problems. In its final phase, spanning from 1943 to early 1945, when it became clear that the Allies would win the war against the Nazi enemy, texts on the planning of a German reeducation rose to fleeting prominence, before the epoch-making genre of Nazi German literature collapsed in a matter of months.2

Two unexpected protagonists, who rose to the challenge of the moment during World War II were Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish and cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead. MacLeish, who was a promising lawyer turned modernist poet, playwright, and journalist, took on the physical task to organize the intellectual struggle against Nazi Germany. How so? MacLeish reorganized the Library of Congress from an allegedly dysfunctional institution into a national research library, that is, as a legislative tool preparing to fight Nazi Germany in the approaching war. He also made sure that intellectuals could gain access to the most recent German materials in newspapers, journals, and books. He helped to create the newly emerging Office of Strategic Services (OSS), arguably the predecessor of the CIA, in the complex world of federal departments and agencies with their own stakes in the analysis of Nazi Germany and he was instrumental in coordinating the intellectual life of Washington’s power elite, for example, by hiring the Nobel Prize–winning German author in exile Thomas Mann as an advisor to the Library of Congress. MacLeish, both thanks to his artistic reputation and his strong ties to the highest ranks of the establishment, went on to function as a magnetic pole. This magnetic pole, the power pole, organized the American study of Nazi Germany especially with regard to two aspects: politics and art. The opposite – yet closely coupled – pole, the pole of knowledge, produced the invisible but tangible magnetic field that helped orient large parts of the intellectual scene. Close to the imagined center of these various informal and institutional networks stood Margaret Mead. Mead, who had first risen to public prominence at a young age as the author of the provocative study Coming of Age in Samoa (1928), was one – if not the – major intellectual force in the collaborative study of Nazi Germany. She commuted regularly between New York and Washington, DC, where she started working in 1942 in a an inconspicuous but extremely well-connected position as executive secretary for the National Research Council’s Committee on Food Habits. She wrote, solicited, and edited reports, letters, and memoranda; she organized committees, group discussions, film screenings, interdisciplinary academic conferences, exhibitions; and she conducted interviews, linked her contacts, met with émigrés, pressed for political action, held lectures, and traveled throughout the United States and to England. Mead connected the various worlds of private institutions, New York’s philanthropic circles, foundations such as the Rockefeller Foundation, the Carnegie Foundation, the Guggenheim Foundation, East Coast and West Coast Universities, and medical and psychological institutions and played a key role in the early consolidation of the idea of a German reeducation. Mead’s was the pole of knowledge that attracted scholarship, as well as credit, as in appreciation and acknowledgment or in the form of stipends and fellowships. To think of MacLeish and Mead as the two poles organizing the study of Nazi Germany during World War II helps to structure an unruly field full of rank growth, opportunism, failed projects, vested interests, institutional constraints, and unexpected consequences. It should, however, not give the false impression that a higher rationality guided them. While I find it useful to personalize these two intellectual poles, I want to put strong emphasis on the fact that they both had powerful institutions, intellectual infrastructures, and energetic networks working for them, which served as the volatile and improvised base of the collaborations between European émigrés and American intellectuals. Indeed, what follows is not a hagiographic account of these two (truly exceptional) individuals. Instead, I will focus on the magnificent group effort of the 1940s and for this reason, I draw on their collective literature – and media production – as object of inquiry.

In order to understand the far-ranging effects of this great convergence, I trace in a history of entanglement the very nature of the intellectual collaboration between European émigrés and American scholars who worked together in government institutions, universities, philanthropic circles, but also informally in circles of friends and families. The common ground of their undertaking, however, was neither personal nor intellectual. Instead, they shared a common practice of communication. They enthusiastically embraced bureaucratic genres and ultimately formed a specific sociality, in which their writings circulated. I will call this the American “memorandum culture” of the 1940s which is at the center of a literary phenomenon that despite its undisputed significance so far has not been considered, the rise of “gray literature.”

The memorandum culture started to blossom in the era of the New Deal, when the enlistment of intellectuals and scientists as government experts gained a new quality, the fruits of which came to full bloom during World War II. The fragile alliances between European and American lawyers, political theorists, geographers, librarians, physicians, cultural anthropologists, artists, film historians, journalists, military officers, sociologists, philosophers, psychoanalysts, government officials, fiction writers, and historians formed in this memorandum culture served as a ferment for a particularly productive moment in the history of the humanities and social sciences, and had a transformative effect on the postwar US-American academic culture, initiating some of the great intellectual projects in American history.

Approaching the intellectual history of this unruly, yet transformational encounter, each of my book’s chapters aims in various ways at a classic publication defining the postwar era and situates the story of its making in collaborative project environments and vis-à-vis other prominent but also lesser known wartime publications as well as unpublished materials. I focus on American publications by both American intellectuals and European émigrés for this study of the memorandum culture, and I try to do justice to its breadth as well as depth, but also its idiosyncratic nature. The selected publications include David Riesman’s Lonely Crowd (1950), Franz Neumann’s Behemoth (1944), Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus (1947), Siegfried Kracauer’s From Caligari to Hitler (1947), Talcott Parsons’ Social System (1951), and Erik H. Erikson’s Childhood and Society (1950), all classics in their respective fields in sociology, political science, legal and economic history, modernist fiction, film studies, systems theory, and developmental psychology.

The book’s basic plot is nothing more, but also nothing less than to trace – in various ways – the heterogenous entanglements of such canonic works in the temporarily forged intellectual networks of the wartime memorandum culture. Chapters 2 and 3 will ground the intellectual history of the American memorandum culture and lay out the social theoretical as well as the material basis of collaboration and communication in the study of Nazi Germany. Chapter 4 then turns to the problem of representing German culture, which is followed by Chapters 5–7 with groundbreaking analyses of German media, society, and psychology. The book thus tells the story of how Nazi Germany captured and transformed the imagination of intellectuals in the United States.

1.1 Entering the Memorandum Culture

On January 17, 1943, Gregory Bateson sent a friendly letter with an urgent request for a memorandum addressed to the Institute of Child Guidance at Berkeley, California:

Dear Erik: In connection with our studies of German character structure, the problem of what data could be obtained from the study of German prisoners, now in the hands of the United Nations, inevitably suggests itself. It occurs to me that it might be well for us to have in our hands a confidential memorandum on the possibilities for such a study, which could be submitted from time to time to such government authorities as may be interested. I know that you have given this matter some thought, and this is a formal request to prepare such a memorandum for the Council’s use. Sincerely yours, Gregory Bateson3

Bateson, a prewar social anthropologist and postwar communication theorist, started in 1939/40 to work in response to the Nazi threat, not as a professor, journalist, freelance writer, political activist, civil servant, or functionary. Rather, he joined various action groups such as the Council on Intercultural Relations, the Committee for National Morale – as a “secretary.” A portion of the most important wartime analyses of foreign nations first passed through “Bateson’s busy mimeograph machine,”4 and entered the surging mail circulation among New York action committees, Washington, DC, government agencies, and East Coast universities thanks to the Manhattan secretary and his tedious crank-handle Xerox. Bateson’s brief request for a confidential memorandum on the methods of study of German war prisoners for the Council on Intercultural Relations’ use, sent to psychoanalyst Erik Homburger Erikson, therefore lays out paradigmatically the operational character of the quickly growing amount of applied research memoranda employed in the intellectual fight against the Axis powers. Wartime memoranda were not primarily written for the consumption by a general public but rather to produce special interest. Under the label of “to whom it may concern,” they addressed authorities and institutions and created various exclusive but overlapping readerships that partook in the circulation of those texts.

The brisk pace and intensity of the emergence of US-American analyses of Nazi Germany cannot be fully accounted for unless one comes to terms with the unprecedented enthusiasm of scholars and intellectuals for writing in bureaucratic genres, adopted from their use in establishment communication: to prepare forms, create protocols, record minutes, keep attendance sheets, file notes, compile dossiers, reference index cards, revise documents, transcribe recordings, generate reports, bring forward joint motions, phrase official letters, submit applications, request funds, acquire expertise, draw organizational charts, enhance procedures, refer to style sheets and follow guidelines – all of which flourished in what I call a memorandum culture.

By the early 1940s, the booming production of literature on Nazi Germany had reached such a level of volume and interconnectedness that people started considering it a topic worthy of its own review journal. Between 1941 and 1944, the “American Friends of German Freedom” grouped around the theologian and “high priest of Protestantism’s young intellectuals”5 Reinhold Niebuhr published a monthly journal that collected and reviewed exclusively writings on Nazi Germany, a journal called In RE: Germany.6 The programmatic title of the journal, the subject line of a memorandum on Germany, indicates that the historical actors studying Nazi Germany perceived themselves as part of a culture producing and consuming gray literature. The journal reviewed an impressive range of published texts, but also of pamphlets and memoranda available beyond the traditional publishing channels, providing a major opening into the study of Nazi Germany – that serves today as an invaluable source for the study of wartime literature on the topic. The journal also came with a heavy intellectual bias, and despite its enormous range, with serious limitations due to the restricted availability of texts. After all, significant parts of the gray literature circulated in small institutions, some of them semiprivate, some of them semipublic, and some of them secret – and never reached the reviewers of In RE: Germany who had to rely on the publication networks they were able to access. Nevertheless, the texts that were reviewed, but also those that should have or could have been reviewed in this journal, are the topic of this book.

Arguably, the studies of the history of World War II literature conducted in intellectual history, cultural history, media studies, the history of the social sciences, and not least German Studies – they all exhibit a certain tendency to feel naturally attracted by published works. Indeed, refocusing the attention on the proliferation of gray literature challenges several well-established concepts and practices of reading. Gray literature, one of the most inconspicuous, operative, and menial literary formats, often produced within and between institutions, leads to several problems regarding physical access and basic understandings of authorship, publishing practices, and readership. My main methodological intervention here lies in the attempt to introduce a mode of reading works of “Nazi” gray literature not only individually and “as if published,” but also in their interrelationship, following their movements and transformations on institutional infrastructures. For this purpose, it has proven highly productive to shift the focus from the study of individual authors to collaborations, under the social historical conditions of warfare, migration and the contact between European émigrés and American intellectuals. The American-European encounter, part of a larger pattern of intellectual migration – “Hitler’s gift”7 to the world – has in fact already spurred a wealth of studies with an emphasis on (auto-)biography, influence, and the development of academic disciplines, initially conducted by wartime intellectuals and their students.8 This was followed by a second generation of scholarship that reflected on the work and experiences resulting from this encounter with a focus on issues such as power, ethnicity, gender, diplomacy, epistemology, and the “alchemy of exile.”9 While there has been in the last decades a strong emphasis on the latter, dismissing as methodically naïve the first, the enormous amount of work of the two generations needs to be equally appreciated for their indispensable insights and, in fact, this book could not have been written without both of them.10

Following the ideal of an “anthropological gaze,” I attempt to defamiliarize the reader’s view of gray literature, which, after its great success in the twentieth century, most people are now accustomed to encountering on a daily basis, but which hardly anyone attempts to understand beyond its immediate purpose. The term “gray literature,” after all, was coined by information scientists who registered, with a certain delay, a new development in print culture.11 Libraries and special libraries were managing an increasing amount of paper that did not arrive from commercial publishers and did not fit into the established categories of books, journals, and newspapers, and accordingly, into the filing systems of library stacks and shelves. Common to all attempts to define the elusive category of gray literature is the recognition that it is produced and distributed outside of the channels of commercial publishing. The rise of gray literature is in fact often dated around World War II and is related to the new types of “classified” texts produced in Allied communications, such as intelligence reports.12 In many cases, however, the exclusivity of gray literature does not come with the full force of the American legal system, which is reserved, for example, for the protection of nuclear secrets, but can also be found in the daily routines of institutional communication “From:” – “To:” – “In Re:” and so on. The library sciences are right to point out that gray literature is largely written out of the public eye, but it must be added that the texts certainly show an awareness of it, and in some cases may even be composed to negotiate the precarious boundary between private, institutional, and public communication. Some may also avoid using established publishing channels because of their contested status, as did mail-order brochures or pamphlets and broadcasts using new media such as radio and cinema, to deliver propaganda messages to some of those citizens, who were not part of the general reading public, and to influence their morale.

The anthropological gaze in fact needs to ignore these categorizations to some extent and focus its attention on the various types of agency and interests involved. “Following the actors” – another guiding anthropological ideal of this work – thus leads directly into the memorandum culture and its social practices of collaboration, cooperative meaning making, negotiation of conflicts, clarification of misunderstandings, as well as the work of maintenance and repair, all of which are often rendered in surprisingly creative ways in the case of the gray literature produced during World War II. Gray literature hence becomes a privileged object of study for the wartime work of intellectuals, as a central means of their imagination, a social medium that coordinates the material flow of communication, a socio-technical mediator between old and new media infrastructures, a tool that guides the movement and transformation of concepts and practices.

The history of science and science and technology studies, in their highly innovative phase toward the end of the twentieth century, have developed several methodological and conceptual innovations that help observing the intricate forms of human and nonhuman agency exhibited in the interaction between various actors and cultural artifacts using institutional or other types of infrastructures. At first sight, in the fast-moving academic world of theory and discursive fashions, these innovations may seem a bit aged by now. Quite to the contrary, I would like to contend, however, that most fields of research, including intellectual history, have been slow to come to terms with these innovations, and therefore have not even really started to draw the far-reaching consequences that also might help to reorient the study of the literature originating from the American-European encounter during the 1940s.

Following Édouard Glissant’s prominent use of “creolization” to approach American cultural history from a “Caribbean” point of view,13 but also Peter Galison in his study of microphysics, I understand the various places of encounter and cultural exchange such as the OSS, action committees, research projects, roundtable discussions, as well as the intense informal or semiformal meetings of intellectual circles in apartments as “trading zones” in which an unforeseen creolization of knowledge happened.14 Neither the American intellectuals nor the European émigrés fully understood what they were in for, and neither side could fully agree on the basic terms and motivations for their intellectual exchange, and, in consequence, neither side could have created individually the conceptual innovations and penetrating analyses found in the gray literature on Nazi Germany. The concept of creolization therefore helps moving beyond monodirectional concepts of influence, of individual or group-assimilation, of cultural appropriation, taking the unequally distributed agency of both sides into account. I follow here, again, an anthropological ideal of reconstructing symmetrically a “reciprocity of perspectives.” Thinking of creolization hardly allows for a rational, guided development, but rather emphasizes the haphazard, unclear, highly local, minute details of exchange and the processes of their mediation in the nitty-gritty questions of translation, corrections of first drafts, note taking and copying quotes, use of preliminary outlines, diagrams, and visual aids, team meetings, transcription of interviews, conception of questionnaires, common authorities and side readings, support by spouses and children, trips and visits, project pitches, sharing of notes, materials, and access, day jobs, hands of invisible technicians, during which some of the most fundamental theoretical questions were collaboratively answered, “from tools to theories.”15 It is therefore always necessary to highlight the contradictory impulses and vested interests resulting in a high degree of improbability predicating all collaborations that produced or failed to produce gray literature.

The interplay of coincidence, unclear situation and momentous decisions can be seen, for example, in the disappointing letter arriving at the Institute of Social Research, at the time located in New York. The historian Eugene N. Anderson at the American University in Washington, DC, responds on December 19, 1940, to an offer to collaborate on a new project within the memorandum culture as follows:

Dear Dr. Horkheimer – I learned a few days ago that the Rockefeller Foundation has assumed charge of the furtherance of studies in this country of Nazi Germany. It is now deciding on the next steps to be taken. I feel very grateful to you for offering the position of collaborator on your project of study of Nazi Germany [sic]. But I still think that you would be much more advised to find someone in New York, and I really do not see my way clear to attempting the work. I must finish a book […].16

Anderson, briefly after, changed his mind and offered his collaboration, but the Institute’s project proposal to the Rockefeller Foundation failed. Instead, Anderson went on to work for the OSS as section chief of the “Central European Section,” mainly responsible for Nazi Germany. Anderson, like many other actors in the memorandum culture navigated within and in-between institutions, crossing the distinction between scholarship and activism, between private and public, and secret.

Sponsored by universities, by philanthropies, but also with government money, the collaboration between European émigrés and American intellectuals heterogeneously applied concepts available to the various contributors from their previous work – often formed and solidified over several decades. They generated texts that created – in a joint effort – shimmering projections of the enemy nation. The wartime collaborations in the memorandum culture worked less, however, toward a shared image of the enemy. Instead, the various collaborators rather shared a practice of “imagination,”17 absorbed in the German enemy. They all did take fascists very seriously – which means in turn for a work on the study of National Socialism that they all should be taken equally seriously as well. Accordingly, the central method to examine the intellectual – sociological, political, fictional, etc. – imagination of Germany in this study is to systematically ignore the failure and success of individual projects as the only measure of historical significance, and, using the same modes of explanation for both, to reconstruct the specific sociality emerging in the collaboration between the various actors, as a history of projects and projectors.18 In order to grasp these projects, special attention is, again “following the actors,” directed toward professional careers as point of access to the collaborative, project-based writing practices.

Rendering the research into gray literature operational, the two main points of departure for my reconstruction of wartime collaboration are, as stated earlier, concepts and practices. I draw accordingly on the history of concepts19 on the one hand, and the theory of practice20 on the other – both, however, from the point of view of literature, reading examples of Nazi gray literature both esoterically, as well as exoterically.

1.2 Émigré Collaborators

The dictum to “follow the actors” poses special methodical problems and leads to unexpected places, when studying wartime collaborations due to the high mobility of some of the intellectuals undergoing voluntary and forced migration. This is obviously true for the European Hitler refugees and exiles of the late 1930s and early 1940s, but it is also true for the distinct group of German language émigrés of the 1920s and early 1930s, who often took on prominent roles within the memorandum culture. Despite the Immigration Act of 1924 following the first major restrictions in 1917, as well as violent anti-German sentiments in parts of the US-American population during and after World War I, which put an end to the long history of free-flowing economically, politically, and religiously motivated migration from Germany, they still encountered much more beneficial conditions to launch their American careers than those fleeing Nazi German aggression after 1938. Often in collaboration with Germanophile American academics, who had fond memories of European tours and who in some cases even held German PhDs, they were able to resettle and establish their professional career in the United States under vastly different circumstances. Especially these earlier arrivals from Europe played key roles in the formation phase of the memorandum culture studying Nazi Germany. Among them were highly influential reformers of administrative techniques and practices such as the German legal scholar Arnold Brecht.21 Brecht arrived in New York in 1933 as one of the transatlantic Nazi refugees to take up one of the few sought-after positions at the newly founded “University in Exile” at the New School for Social Research, initially funded by a Rockefeller Foundation Grant. This position enabled him to publish The Art and Technique of Administration in German Ministries (1940), coauthored with his student Comstock Glaser, as well as his pioneering study on the collapse of the Weimar Republic Prelude to Silence: The End of the German Republic (1944), and to work in the memorandum culture, for example, for the Council for Democracy, as advisor to the War Department, the Office of War Information, as chairperson of a special committee for comparative international administration created by the Social Science Research Council,22 and as teacher at the School of Overseas Administration at Harvard University.23 The Jewish-Austrian Paul F. Lazarsfeld, one of the founders of empirical social research and the academic study of propaganda in the United States in the Princeton Radio Research Project, arrived with the help of a similar grant in the same year.24 One of the most prominent members of the memorandum culture, Hans Kohn, the nestor of the American study of nationalism is a particularly interesting case in point, as his career in the decades before his arrival in 1934 both represents the irreducible complexities American intellectuals faced when collaborating with émigrés, as well as the intellectual potential of their encounter.

When Kohn, professor for Modern European and Asiatic History at Smith College in Northampton, MA, published his study The Idea of Nationalism in 1944, in which he historicizes the idea of nationalism, he acknowledges in his preface in sufficiently clear terms – for anybody who cares to know – his membership in the memorandum culture. He states that “[d]uring the years of collecting and organizing the material the author has been generously helped at various times by grants-in-aid from the Social Science Research Council and the Bureau of International Research of Harvard University and by a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, to all of which he feels greatly indebted.”25 Both the Social Science Research Council and the Bureau of International Research of Harvard University were financed by funds dispersed through the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Fund, closely connected to the Rockefeller Foundation, one of the largest philanthropic sponsors of group projects and individual collaborators in the memorandum culture, acting besides the Guggenheim Foundation, mentioned in the above quote, the Carnegie Foundation and others.

To get a better grasp of how, in the case of Kohn, nationalism and memorandum culture come together, a detailed look at Kohn’s career seems warranted, before proceeding with the brief outline of his argument on the concept of nationalism as a historical practice of imagination. Furthermore, Kohn’s work provides rich materials for the literary historical interest of this study. His distinct life story also offers some clues regarding the unavoidable misunderstandings and the general imponderability of the political and intellectual background of the individual European émigrés entering the memorandum culture. Several of the émigrés, which were loosely identified as German or European, in fact originated from a highly mobile class of academics that makes it necessary, to put on, as David Blackbourn has shown in his history of Germany in the World, a lense of global history to understand the trajectories of German emigration during the 1930s.26 The esoteric and exoteric readings of gray literature therefore not only zoom in on minute details, but they also zoom out to grasp the various actors’ interconnectedness in world-spanning chains of operation.

Kohn27 was born in Prague in 1891 to a secular Jewish upper middle-class family and attended school at the same institution as did authors Franz Kafka and Hugo Bergmann about ten years earlier. Even before reaching the age to attend university, he joined the Zionist student club Bar Kochba, intensely discussing a Jewish nationalism. He then began, still in Prague, at the time part of the multiethnic and multilingual Austro-Hungarian Empire ruled by the Habsburg Monarchy, to study law, while also engaging in Zionist publication projects like editing the anthology Vom Judentum.28 In 1914, at the onset of World War I, Kohn’s initial enthusiasm led him to join an Officer Candidate School in Salzburg. He eagerly volunteered for a mission in the Carpathian Mountains in February 1915. After less than two months in action, the Imperial Russian army captured Kohn, and brought him as prisoner of war (POW) to the “Oriental Russian Colony” Samarkand. Thus began a five-year-long involuntary yet formative journey. After attempting to escape toward Afghanistan, Kohn was deported further eastward to Gultscha in the Pamir Mountains of Turkestan. Toward the end of 1916, he underwent a 32-day transfer, first to Samara on the Volga, then again eastward to a prisoner camp for officers in Khabarovsk. After the Bolshevik revolution in March 1917, Kohn was relocated even farther east to Novosibirsk and the Krasnoyarsk camp. It was during this period that he dedicated himself to self-education, immersing himself in a wide range of subjects. In addition, he assumed the role of chairman in the Siberian POWs’ largest Zionist organization, engaging in both political and cultural pursuits that involved delivering biweekly public speeches. When Kohn was eventually released from the POW camp in 1919, he decided to remain in Siberia, likely influenced by his political involvement with the local Jewish population.29 He moved to Irkutsk where he assumed the role of secretary at the Zionist central office of Siberia. Simultaneously, he applied for Czechoslovakian citizenship to serve as a cultural administrator for the newly established Czechoslovak Republic. In the winter of early 1920, he started his long way back home, traveling through Khabarovsk, Yokohama, Tokyo, the Indian Ocean, and the Suez Canal to Marseille. Passing through Switzerland and southern Germany, he eventually arrived in Prague, where he wasted no time in publishing various manuscripts he had written during his time as a POW. Notably, he translated Joseph Klausner’s history of “Neo-Hebrew” literature into German30 and produced an affirmative book on nationalism.31 These publications marked the resurgence of his lifelong dedication to writing and publishing. Soon after his arrival, he left Prague for Paris – and for good. In Paris, he took up a short-term position with the Comité des Délégations Juives before relocating to London in 1921. In London, he became an active participant in the World Zionist Organisation and assumed membership in the socialist Fabian Society. Additionally, he devoted himself to propagating the cause of Keren Hajessod, a Zionist organization dedicated to financing settlements in Palestine. In this function, he moved in the mid-1920s to Palestine. Furthermore, in 1925, Kohn played a pivotal role as one of the founding members of Brit(h) Shalom. This organization advocated for the establishment of a binational state in which Jewish and Arab citizens would enjoy equal rights. However, after a conflict emerged in 1928 over the Wailing Wall of Jerusalem, resulting in violent clashes, Kohn’s faith in the Zionist cause began to wane. He decided to publicly recognize the legitimacy of claims of an Arabic nationalism, which led – after 20 years of Zionist engagement – to his incremental resignation from his several functions in 1929/30. Before stepping down, though, he obtained Palestinian citizenship in 1929. In 1931, faced with perpetual financial instability, Kohn embarked on a venture, with assistance from the Institute of International Education, to deliver paid lectures in both Europe and the United States. Following a successful series of lectures at the New School for Social Research in New York, Kohn secured a position at Smith College in the autumn of 1934. At the age of 42, he obtained a stable academic position for the first time. Consequently, he relocated from Palestine to Northampton, MA, to assume his role as a highly popular teacher at Smith College. In the new position, Kohn indeed not only thrived as a prolifically publishing professor, but also emerged as a prominent public intellectual, who toured the lecture circuit throughout the United States. He quickly built an impressive network of contacts on the East Coast, continuing his highly mobile existence with weekly trips to New York, and after starting to teach at Harvard Summer School in 1936, to Cambridge, MA. He maintained at his home together with his wife a busy social life. Beyond the circles at Smith College associated with William A. Neilson, the college’s president, and contacts to the colleagues at nearby colleges and universities in Massachusetts, such as to Carl J. Friedrich at Harvard University, he gravitated around New York institutions, especially the aforementioned Institute of International Education, the New School for Social Research, but also the Asia Institute and the American Association for Adult Education. He could rely on close contacts to the émigré circles around the Mann family, the scholarly community of the East coast, especially including experts on Asia, as well as Black intellectuals such as Alain Locke and W. E. B. Du Bois interested in his ideas on Jewish nationalism reverberating with discussions about Black nationalism. Not least thanks to his head start and his early involvement in American institutions already during the New Deal era, he became one of the most influential émigrés in American intellectual life during World War II. In this capacity, he participated in various groups and committees, for example, in 1939/40 together with, among others, Thomas Mann, Lewis Mumford, Giuseppe Borgese, and Hermann Broch on the publication of a conservative, humanist, and anti-isolationist manifesto City of Man. A “First memorandum” was attached to this publication, presenting the argument of my work in historical plain text: “The collaboration of what is best in American culture with what is best in European intellectual immigration might be the source of incalculable benefits for the active intelligence of tomorrow.”32

To sum up: When the “German émigré” Kohn became naturalized as US-American citizen in 1940, he was or had been fluent in six languages from four language families and held his fourth citizenship. Over the course of his lifetime, the young Zionist went on to experience several political reorientations, transitioning from a monarchist Zionist to a socialist Zionist, then evolving into an anti-Zionist liberal pacifist and humanist. Eventually, he emerged as a vocal anti-fascist, before identifying as a conservative anti-communist. His numerous ideological shifts were so profound and diverse that it is entirely appropriate to describe his journey as driven by “multiple metamorphoses.”33

Kohn’s exceptional experiences granted him a singular authority to speak about a multitude of phenomena, particularly nationalism. His shifting perspectives throughout his career contributed to his nuanced understanding, while his dedicated study of both “Western” and “Eastern” nationalisms continued over several decades. His firsthand observations of the utopian rise of nationalism among Czech Jews circa 1900, coupled with his active involvement in the early twentieth-century Zionist endeavor in Palestine, provided him with invaluable insights into the complex political realities associated with nation-building. He had also learned from an early age to exercise his practice of imagination in the context of his collaborative work in clubs, committees, and institutions in multilingual and multiethnic alliances. Like many of his contemporaries in Europe who had lived through the tumultuous events of the early twentieth century, Kohn was well versed in a crucial “biographical” technique that was integral to the figure of the collaborator – conversion.34 The practice of conversion involves renouncing one’s outdated beliefs, undergoing a radical change of perspective, and embracing the new creed. This is quickly followed by the unwavering adoption of a disciplined state of mind – and body. This state, as I will argue in the following chapters, is strongly associated during the 1940s with the concept of “objectivity.” Especially for the European émigrés, but also for American intellectuals, conversion was a crucial skill to adapt to the new political scene of the memorandum culture, and to use their existing intellectual resources in a new, sometimes contradictory environment, to find common ground with other European and American intellectuals of various backgrounds, to please sponsors, while at the same time pursuing their long-developed projects and reasserting their agency.

1.3 National Literature: German Problems

After outlining Kohn’s biography and the complex political practices of imagination of European émigrés entangled in patterns of global migration, the crucial conceptual question may be tackled. What is, after all, in 1944, nationalism – and correspondingly national literature – according to Kohn?

– Nationalism is a historical phenomenon: “Nationalism as we understand it is not older than the second half of the eighteenth century.”35

– Nationalism is bound to the rise of the bourgeoisie: “Nationalism is inconceivable without the ideas of popular sovereignty.”36

– Nationalism is not bound to the state: “Among these peoples, at the beginning it was not so much the nation-state as the Volksgeist and its manifestations in literature and folklore, in the mother tongue, and in history, which became the center of the attention of nationalism.”37

– Nationalism is a feeling: “For its composite texture, nationalism used in its growth some of the oldest and most primitive feelings of man, found throughout history as important factors in the formation of social groups.”38

– Nationalism is anonymous and deterritorialized: “Nationalism – our identification with the life and aspirations of uncounted millions whom we shall never know, with a territory which we shall never visit in its entirety […].”39

– Nationalism is a practice of imagination: “Nationalism is first and foremost a state of mind, an act of consciousness, which since the French Revolution has become more and more common to mankind.”40

– Nationalism is international and symmetrical: “[The] very growth of nationalism all over the earth, with its awakening of the masses to participation in political and cultural life, prepared the way for the closer cultural contacts of all the civilization of mankind (now for the first time brought into a common denomination), at the same time separating and uniting them.”41

– Nationalism is arbitrary: “Although some of these objective factors are of great importance for the formation of nationalities, the most essential element is a living and active corporate will. Nationality is formed by the decision to form a nationality.”42

– Nationalism is traditional: “Nationalities are created out of ethnographic and political elements when nationalism breathes life into the form built by preceding centuries.”43

– The ultimate limit of nationalism is fascism:

Nationality, which is nothing but a fragment of humanity, tends to set itself up as the whole. Generally this ultimate conclusion is not drawn […]. Only fascism, the uncompromising enemy of Western civilization, has pushed nationalism to its very limit, to a totalitarian nationalism, in which humanity and the individual disappear and nothing remains but the nationality, which has become one and the whole.44

The last point deserves special attention. “Fascism” becomes in an otherwise largely historicist display of humanist erudition the contemporary extreme and breaking point of Kohn’s argument. The relativism between absolute parts coexisting in a whole disappears in the moment that one part takes on the role of the whole for all other parts which it does not recognize as such. In other words, Kohn’s well-balanced theory and historical narrative becomes subject to what may be called Nazi Germany’s “hostile takeover” of nationalism. This appropriation of the analysis by one object of Kohn’s work in particular – and of significant parts of US-American imagination in general – needs further explanation. At some point in the 1930s, Nazi Germany in all its shapes, forms, and conceptualizations as “Nazism,” “Fascism,” “National Socialism,” “totalitarianism,” and “Hitlerism” started to take on a topical role as extreme point, hyperbole, negative example, litmus test, Rorschach test, as the place of chaos, terror, evil, darkness, anomie, pathology, irrationality, perversion, or as the figure of the mentally ill, villain, criminal, gangster, perpetrator, barbarian, liar, charlatan, terrorist, false prophet, demon, Antichrist, devil – and to invade sociological, anthropological, psychological, linguistic, political, legal, economic, philosophical, pedagogical, and aesthetic theories.

For the idea of nationalism, the hostile takeover during World War II – in the case of Kohn long prepared by four preceding books (as well as several articles, speeches, and lectures) published between 1936 and 194245 – has been irreversible. All further books on the topic are haunted or respectively remotely controlled by the undeniable nationalism of National Socialism, even after the reassessment of nationalism in the global light of the extra-European and postcolonial foundation of nations.46

Looking back at Kohn’s life work, it appears as if one might just add to his later historicization of nationalism Kohn’s early Zionist engagement, his publication of Vom Judentum, his participation in the revival of Hebrew as a national language, as well as his translation of a history of Hebrew national literature, Geschichte der Neuhebräischen Literatur, to arrive at a novel concept of national literature in 1944, not in theory, but in practice. The memorandum culture formed by American intellectuals and European émigrés studying German problems apparently produced a short-lived imagined community that participated intellectually, passionately, and largely anonymously in the production, distribution, and consumption of national literature, in both fact and fiction, as well as several genres in between, imagining the distant German nation. Dealing with the pathologies of nationalism, Nazi German “enemy literature” was, following Kohn’s reflections and literary practice, the truest of national literatures, and it also served the purpose of concrete nation building as it fundamentally shaped the imagination of what a new German nation without National Socialism might look like. In this sense, this book on the memorandum culture of World War II and its collaboratively produced gray literature is in its broadest definition a study of German national literature.

In the manner of an umbrella study of American Nazi literature as national literature, I follow several of the murky roads traveled by the various actors. Indeed, these often lead to rather unexpected places, discursive formations, and specialized literatures, which might come as a surprise to some readers, such as business history, the development of microphotography, the edition of Early Modern prints, Balinese dance, Calvinism, and the Pine Ridge Reservation of the Oglala Sioux. I introduce relevant aspects of these and several other contexts not primarily because they are curious, but more importantly since this is where some of the most striking and historically important features of the American imagination of Germany were shaped. As such, they are crucial to foster a better understanding of German national literature during World War II. Accordingly, the chapters of this book may be read individually by those with a special interest in specific topics such as “intelligence” (Chapter 3), “exile literature” (Chapter 4), “propaganda” (Chapter 5), or “reeducation” (Chapter 7). Taken together, however, the reader will find in the succession of these chapters on the study of Germany the outline of a hidden intellectual history of the 1940s.

Enemy Literature starts with a meditation on David Riesman’s concept of “other-direction,” laid out in his classic study The Lonely Crowd as a theoretical baseline for my book (Chapter 2), moving from other-direction to émigré-direction to enemy-direction. I consider various paradigmatic experiences of transatlantic migration and their consequences for American sociality, with a special focus on conceptions theorized by Black intellectuals, such as Zora Neale Hurston and Alain Locke, and their consequences for a symmetrical approach to the intellectual history of American–European collaborations in World War II. The chapter provides a theoretical outline for understanding the sources and aspirations of the cool-headedness observed in these collaborations.

The first historical case study of the encounter between American lawyers and German-Jewish Marxists focuses on collaborative writing practices (Chapter 3). It traces the invention of the intelligence report during World War II and describes this genre’s characteristics as paradigmatic for the bureaucratic style of the memorandum culture. Franz Neumann (the intellectual head of the OSS’s Research and Analysis branch) and his grand analysis of Nazi Germany in Behemoth is thus considered in close relationship to his work as intelligence analyst collaborating with his European and American colleagues. In this chapter, I describe the medial infrastructures that were used to analyze the distant enemy, and I ask in a reading of the intelligence report “German Morale after Tunisia” what it meant to “understand” the Nazi enemy in 1943.

The next chapter (Chapter 4) plays mainly between Washington, DC, and Pacific Palisades, CA. I present the writer Thomas Mann as part of the memorandum culture fighting against Nazi Germany and I demonstrate, what a literary-critical analysis of his work looks like, if one takes his job situation in the early 1940s into account: Consultant to the Library of Congress, appointed by MacLeish. For this purpose, I highlight the central role of Mann’s collaborations – on various scales and levels of intensity – with folklorist Gustave O. Arlt and scholar Joseph Campbell, critical theorist Theodor W. Adorno and journalist Agnes E. Meyer in the making of Doctor Faustus.

Chapter 5 moves from Washington, DC, to New York and details the brief collaboration between Siegfried Kracauer and Gregory Bateson, the husband of Margaret Mead, in the Film Library of the Museum of Modern Art as an intriguing encounter in American intellectual history, the history of film and media studies, and the history of German Studies. I look at the Frankfurt School as part of the 1940s memorandum culture and thereby reconsider the historiography of critical theory during this formative period within a broader intellectual landscape, that is, in dialogue and institutional competition with further projects to study the Nazi German enemy, in this case, the Culture and Personality School. My argument takes Bateson’s and Kracauer’s analyses of a song in the Nazi movie Hitlerjunge Quex as a case in point and develops some of Kracauer’s and Bateson’s most important methodical innovations and insights into Nazi German propaganda that underlie Kracauer’s famous film historical study From Caligari to Hitler.

The Harvard sociologist Talcott Parsons is one of the prime intellectual actors of World War II producing applied studies of Nazi Germany and providing training to members of the military government entering the occupied areas in Germany. Chapter 6 revisits his collaboration with Carl J. Friedrich, especially on a pamphlet on Nazi Poison, his momentous meeting with social philosopher Alfred Schuetz and political theorist Eric Voegelin. I argue that the insights that he gained into the supposed “anomie,” that is, the chaotic nature of Nazi Germany starting in 1938 and throughout World War II, significantly shaped – by means of inversion and contrast – his positive design of a functioning social system in his postwar study The Social System, at first for the United States, but then also globally, as a scheme for the organization of modern society as such.

Erik H. Erikson’s book Childhood and Society, started, as I show in Chapter 7, with his “remote” psychoanalysis of Adolf Hitler. I present the transatlantic history of the concepts “identity” and “reeducation,” which may serve as a prime example for the impact of the study of Nazi Germany’s alterity on postwar intellectual discourse. Chapter 7 traces the use of the two concepts in a microhistorical account in order to arrive at macrohistorical revisions. I show how the conception of reeducation migrated from Native American reservations to the wartime pathologization of the Nazi German enemy. Only then – in collaboration with Margaret Mead – it became the name of the policy according to which the United States planned and initially attempted to subject, as Occupation power, the postwar German society in order to reintegrate the outcast nation back into the family of man.

The individual chapters do not intend to serve as critical commentary, as text genetic accounts, or as comprehensive interpretations of major postwar publications according to the respective author’s image of Nazi Germany, even though a reader attentive to these questions might find in this book several lines of argument, observations, and framings of interest. Rather, each chapter forges a distinct pathway of imagination, traces a chain of translations, draws an intellectual trajectory, sequences a creative process, and thereby shows how central aspects of the conception, production, or reception of these works moved in and out of the memorandum culture. In this way, exploring the rise of gray literature, I attempt to establish the principles of generation and administration of collaborative wartime literature, its concepts and practices that – often with little or no reference to the circumstances of their emergence – are synthesized in these famous postwar book publications.

1.4 Include Me Out

Since the phenomenon – a distinct memorandum culture producing gray literature for the study of Nazi Germany – has never been fully recognized in research, it is fair to ask, whether I am dealing with a hallucination rather than with a serious object of study, or, if real, rather with a marginal aspect, or, if central, rather with a fuzzy problem that fails to capture the imagination? Indeed, there are substantial problems in pinpointing the phenomenon – largely stemming from the high mobility and diversity of the actors – to be considered along the way. In the second part of this introduction, I would like therefore to create a more concrete picture of the American memorandum culture, necessarily including some serious flaws and distortions, and yet, answer most affirmatively that it was real, central, and certainly did capture the imagination during the 1940s.

There was at least one author, who, however, seriously suffered from hallucinations on several occasions during episodes of delirium tremens stemming from his alcoholic disease, who was an outsider to both the literary establishment and the bohemian avantgarde and who made it his literary project to situate fuzzy problems in the milieu of their making. Almost as forgotten as the culture that produced the gray literature on Nazi Germany is its most important immediate – albeit satirical – imaginative representation in a major work of fiction, Sinclair Lewis’ Gideon Planish (1943).47

Lewis, who won in 1930, one year after Thomas Mann, as the first US-American author the Nobel Prize in literature, had become famous for his satires, highly critical of American professional culture. His portrayals of frauds, misguided idealists, and middle-class conformism, as well as of surprisingly strong female characters, were partly based on his experiences of growing up in the semi-periphery of the mid-West in Sauk Centre, a small town in Minnesota, but they were also based on social scientific as well as journalistic practices of qualitative research. These included participant observation, expert interviews, oral history, as well as investigative journalism, digging for scandals, and a long series of road trips into the country. After collecting “dope,”48 that is, raw material for his novels, the highly prolific writer created in his fiction a world that gained a representative quality for contemporary developments in American culture and were read as a “social document of a higher order.”49 He thus straddled the line between fact and fiction in various genres, ranging, among others, from magazine serials, to poetry, plays, short stories, and major novels – a career sustained largely by New York’s growing world of publishing, hungry for authentic material to reach audiences beyond the city’s bubble.50

During World War I, along with several socialist intellectuals, he took a pacifist and “non-anti-German” position, as in his unpublished story “He Loved His Country,”51 before ultimately supporting American intervention. Lewis wrote his first bestselling novel Main Street (1920) on a wave of what his publisher Alfred Harcourt picked up as the “zeitgeist” of the postwar moment, a “questioning of standards,” which meant that “non-fiction on urgent topics would have bestseller potential, along with iconoclastic, realistic fiction,” such that his novel was published in the same spirit – and by the same editor – as British economist J. Maynard Keynes’ Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919), “a timely demolition of the Versailles Treaty.”52 The novel was followed by Babbitt (1922), satirically depicting George Babbitt, a businessman, who arguably represents the “prototype of the ‘other-directed’ personality later analyzed by David Riesman in The Lonely Crowd.”53 For Arrowsmith (1925), Lewis developed a technique of literary collaboration with Paul de Kruif, a trained microbiologist, to work with an expert as informant and (uncredited but paid) coauthor, to write a novel about a bacteriologist.54 Lewis shared with de Kruif an iconoclastic spirit of “debunking,” as well as a habit of excessive drinking under the conditions of the Prohibition era. They also both held a strong skepticism toward American philanthropies, evidently built in large parts on the money of “robber barons,” such as John D. Rockefeller, whom Lewis despised after the infamous Ludlow Massacre of 1914,55 carried out one year after the establishment of the Rockefeller Foundation. Before turning into a freelance writer, de Kruif had in fact been working for the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, but was fired after being identified as the anonymous author of a piece that “charged the institute with commercialism and flawed science,”56 an affront possibly aggravated by his apparent antisemitic sentiments toward Simon Flexner, director of the Institute and brother of the educational reformer Abraham Flexner.57 Arrowsmith directly – yet largely implicitly – targets these changes in what de Kruif and Lewis perceived as an increasingly impersonal and profit-driven American medical culture taught in standardized “scientific” programs at medical schools, resulting from the highly influential (Abraham-)Flexner Report, originally written for the Carnegie Foundation in 1910.

As Lewis suffered more and more from an alcoholic disease during the 1920s, which he spent mostly traveling between the United States and Europe, in close vicinity but ignored by the avantgarde circles in Paris, he repeated this model of collaboration with the Unitarian minister Leon M. Birkhead in Elmer Gantry (1927), a novel on religious hypocrisy, commercialization, and corruption in the evangelical movement. The publication created, even more than Main Street and Babbitt, a scandal, which successfully translated for the PR-savvy author into publicity that in turn boosted the sales. He failed, however, in these years, despite several research trips, concepts, and promises to his editor to realize his long-held plan of a mangnum opus, a novel about the American labor movement.58 While the Nobel Prize cemented his literary reputation, it was his relationship with activist journalist and author Dorothy Thompson starting in 1927, then chief European correspondent in Berlin for the Philadelphia Public Ledger and the New York Evening Post, which gave his flagging work during the 1930s a new direction. Thompson, who interviewed Adolf Hitler in 1931, quickly became one of the most vocal public critics of National Socialist Germany, and for Lewis a new collaborator with expert knowledge, literary skill and – unlike de Kruif – a public persona in her own right.59 Lewis’ novel It Can’t Happen Here (1935) is an early literary response to the debates on fascism, depicting the rise of an American dictator Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip, who is modeled after Huey Long, a populist Democratic governor and then senator from Louisiana, whom Thompson interviewed in early 1935 – before his assassination in September60 – as he considered mounting a third-party bid for the 1936 presidential election. As one of Lewis’ biographers lays out the disquieting political map of American fascism and national socialist tendencies in 1935 in front of Lewis:

The real threat came from a weird mélange of quasi populist movements, each founded by a charismatic leader: Huey Long’s “Share our Wealth” movement; Father Coughlin’s Union of Social Justice; Dr. Francis E. Townsend’s Old Age Revolving Pensions Plan; and Upton Sinclair’s more or less socialist End Poverty in California (EPIC) Party. If they could unite and attract disaffected Democrats like Al Smith and Jeffersonian Democrats, they could conceivably elect their man president. To the seething cauldron be added native fascist groups like the Silver Shirts, the German-American Bund, and the Black Legion, which preached a hate litany of anti-Semitism, anti-Catholicism, and anti-immigrantism and extolled Hitler and the Nazis.61

Thompson, while not directly involved in the writing process, provided Lewis with the necessary “impetus,” served as “one of his advisors on the subject of Nazism,”62 as well as his “researcher”63 on domestic politics, giving the novel much of its poignancy.64 Lewis’ genuine addition to the imagination of an American public facilitating a dictatorship is already present as a topic throughout his work of the 1920s and the early 1930s, albeit in different contexts – the social role of clubs, associations, councils, committees, unions, leagues, and societies in American middle-class culture.65 The subversive cell of American fascism in It Couldn’t Happen Here provides the setting for the book’s opening sentence: “The handsome dining room of the Hotel Wessex, with its gilded plaster shields and the mural depicting the Green Mountains, had been reserved for the Ladies’ Night Dinner of the Fort Beulah Rotary Club.”66 Lewis puts a philanthropic circle at the beginning of his novel, in which the retired Brigadier General Herbert Y. Edgeways and Mrs. Adelaide Tarr Gimmitch spread fascist propaganda.67 The setup leads journalist Doremus Jessup, the liberal counterpart to the dictator Windrip, later to the novel’s key statement: “This is revolution in terms of Rotary.”68 American fascism, according to Lewis’ pungent pun, is mediated in social clubs, spreading the upper class principle of philanthropy in middle-class settings.69

By the late 1930s, after Lewis’ and Thompson’s separation, he turned his attention to writing and producing plays. Apparently with some spite toward Thompson’s strong public positioning and advocacy for American aid to Britain after the start of World War II, Lewis again fell back on his early World War I isolationist attitudes and joined the emerging memorandum culture from the extreme right, through the short-lived, yet infamous America First Committee. As several other public figures and intellectuals, Lewis picked up on a popular noninterventionist sentiment and coalesced with people such as the world-famous aviator Charles Lindbergh, who spread his antisemitic views and publicly praised the achievements of Hitler and National Socialism, but also retired Brigadier General Robert E. Wood, chair of the retail chain Sears Roebuck. Lewis in effect joined “in terms of Rotary” the proto-fascist coalition between charismatic populist leaders and Republican extremist capitalists he had warned of only a few years earlier.70 However, briefly after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the end of American noninterventionism as well as after finalizing his divorce with Thompson in January 1942, he started pursuing the plan to return to a critical satire about the “Great Leaders who stand up on platforms and lead noble causes – any damned kind of causes.” In his view, they were constituting “a new crop of Saviours of Democracy”71 found in the world of philanthropy, the nucleus of Gideon Planish.

Gideon Planish is a reinstatement of Lewis’ literary innovations of the 1920s, but applied to his political development alongside Dorothy Thompson in the 1930s, followed by a recent move away from narrative prose toward dramatic and oral forms of expression. About fifteen years after Elmer Gantry, Lewis again contacted Birkhead, this time because of his role as president of the political organization Friends of Democracy, founded in Kansas City in 1937, and then moved to New York in 1939. He also hired James Hart, a former journalist, to investigate potential scandals in the world of charitable foundations as material for his novel. Another line of research came through his renewed experience of American university culture, more than thirty years after graduating from Yale University, on occasion of teaching a creative writing course at the University of Minnesota. Most importantly, however, he draws on his participant observations of Dorothy Thompson and her circle’s engagement in the emerging memorandum culture.

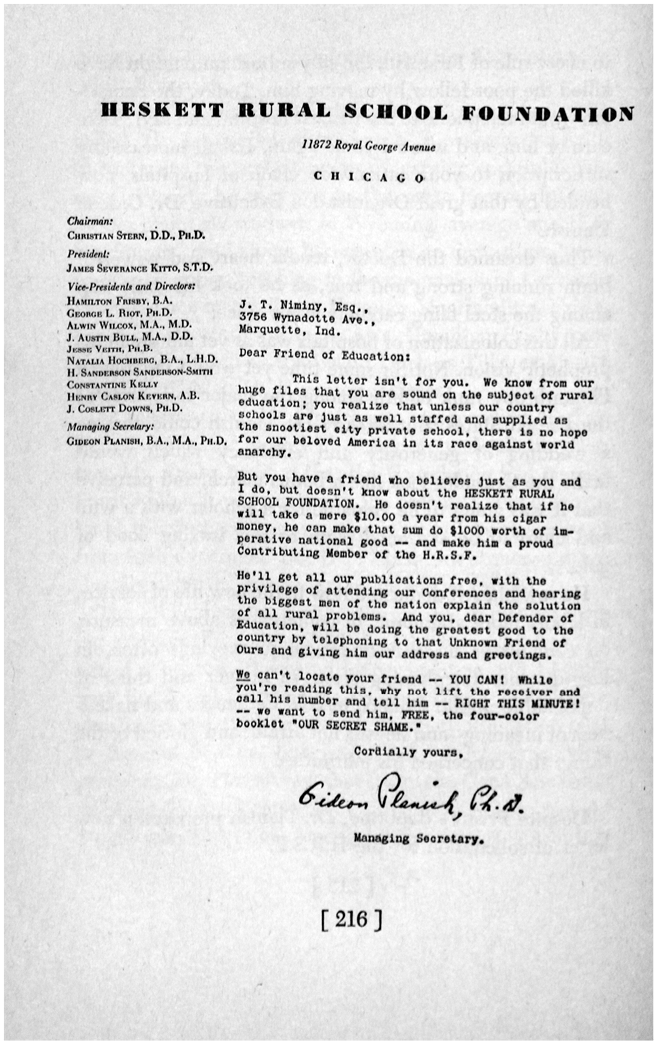

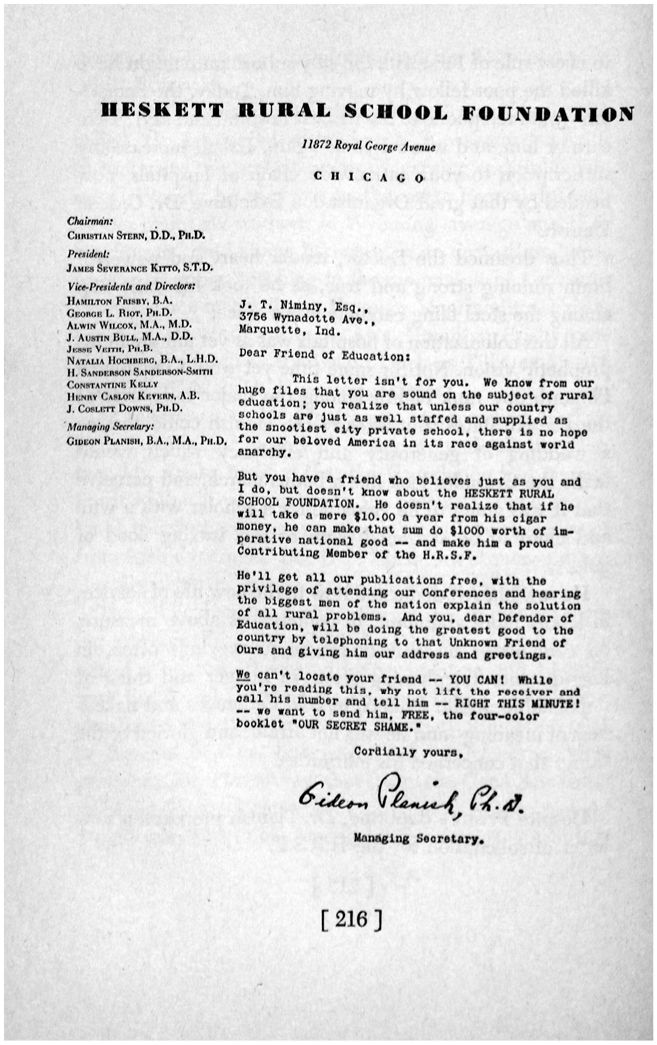

Lewis tells in his novel the story of the social climber Gideon Planish, starting with his childhood in the fictional mid-western state of Winnemac, his college education and participation in the “Adelbert College Socialist League,”72 where he starts training his debating skills, including the ability to influence people’s opinions, but also to drastically change his own political positions, before he is hired as a “Professor of Rhetoric and Speech in Kinnikinick College, Iowa”73 at age 29. As professor, he becomes infatuated with one of his first-year students: “He thought, this Peony Jackson is so fresh and jolly and cool.”74 They quickly marry and become an ever-indebted 1920s wannabe power-couple, dysfunctional but highly ambitious, pursuing half-baked ideas, as they enter the world of clubs, religious charities, and private philanthropies, among them, notably, the Kinnikinick Rotary Club.75 Lewis picks up the theme of philanthropy largely implicit in Arrowsmith and explicit in It Can’t Happen Here, and throws the married couple into the world of the memorandum culture, which takes them from Ohio and Iowa eastward to the suburbs of New York, Washington, DC, and finally New York City. Always more imposter than scholar, Planish quits his university position and becomes editor for Rural Adult Education, where he further develops his art of using commonplaces and learns his most important lesson in public speech, to respect “taboos and libel laws. He must invariably speak reverently of mothers, duck-hunting, the Y.M.C.A., the Salvation Army, the Catholic Church, Rabbi Wise, the American flag, cornbread, Robert E. Lee, carburetors and children up to the age of eleven.”76 As no job ever pays enough, the protagonist of Gideon Planish – a screwball comedy with institutional rather than romantic entanglements – moves through various odd jobs provided by his connections to “organizators”77 and wealthy donors such as ghostwriting an autobiography. “Planish had been honored by his first invitation to become a ‘national director’ of a great organization with its office in New York: The Sympathizers with the Pacifistic Purposes of the New Democratic Turkey.” The organizations acronym “S.P.P.N.D.T.”78 is the first in a series of increasingly absurd abbreviations, such as the “Heskett Rural School Foundation […] H.R.S.F.,”79 whose activities remain a mystery to the protagonist even after he joins the National Directorship of the foundation: “Before the annual conference of the Heskett Foundation, Dr. Planish had learned everything about it except why it existed at all.”80 In his new role, “managing secretary,” he is responsible for the publication of speeches by among others H. Sanderson Sanderson-Smith, in “flat little gray pamphlets.”81 He also sends out elaborate fundraising schemes to supporters of the foundation, possibly one of the first graphic depictions of a memorandum in literary fiction (Figure 1.1). Lewis turns on this occasion to the aforementioned “nucleus” of the novel, giving a detailed description of the circular logics underlying Gideon Planish’s bureaucratic work in philanthropy.

With the passion for exactitude and flapping charts which is part of the New Scientific Philanthropy, Dr. Planish calculated that it cost ten cents to send out a letter, including stationary, postage, mimeographing, filling in, the booklet, overhead, and purchasing lists of persons known to have been philanthropic – which were rather coarsely known as “sucker lists,” and which were sold commercially, like fly-paper. As the professional saviors put it, “If one per cent of the prospects on the sucker list kick through, the cost of the campaign is covered.”82

Figure 1.1 Sinclair Lewis, Gideon Planish (1943), page 216.

Figure 1.1Long description

The letter is not printed in the regular typography of the novel and shows small flaws in its alignment and generally a poorer quality of print, providing it with the outlook of a regular non-fictional memorandum.

The one-page message has a letterhead of the Heskett Rural School Foundation located in Chicago, which has the design of a pre-printed institutional form.

It lists the following names, their titles, and their positions:

Chairman: Christian Stern, D.D., Ph.D.

President: James Severance Kitto, S.T.D.

Vice-Presidents and Directors:

Hamilton Frisby, B.A.

George L. Riot, Ph.D.

Alwin Wilcox, M.A., M.D.

J. Austin Bull, M.A., D.D.

Jesse Veith, Ph.B.

Natalia Hochberg, B.A., L.H.D.

H. Sanderson Sanderson-Smith

Constantine Kelly

Henry Caslon Kevern, A.B.

J. Coslett Downs, Ph.D.

Managing Secretary

Gideon Planish, B.A., M.A., Ph.D.

The message of the memorandum itself is typed using a typewriter and gives the impression of a professional typist since it is written evenly with correct line spacing and without mistakes. The letter is as follows:

J. T. Niminy, Esq.,

3756 Wynadotte Ave.,

Marquette, Ind.

Dear Friend of Education:

This letter isn’t for you. We know from our huge files that you are sound on the subject of rural education; you realize that unless our country schools are just as well staffed and supplied as the snootiest city private school, there is no hope for our beloved America in its race against world anarchy.

But you have a friend who believes just as you and I do, but doesn’t know about the HESKETT RURAL SCHOOL FOUNDATION. He doesn’t realize that if he will take a mere $10.00 a year from his cigar money, he can make that sum do $1000 worth of imperative national good – and make him a proud Contributing Member of the H.R.S.F.

He’ll get all our publications free, with the privilege of attending our Conferences and hearing the biggest men of the nation explain the solution of all rural problems. And you, dear Defender of Education, will be doing the greatest good to the country by telephoning to that Unknown Friend of Ours and giving him our address and greetings.

We can’t locate your friend – YOU CAN! While you’re reading this, why not lift the receiver and call his number and tell him – RIGHT THIS MINUTE! – we want to send him, FREE, the four-color booklet “OUR SECRET SHAME.” Cordially yours,

Gideon Planish, Ph.D.

Managing Secretary.

The signature by Gideon Planish is handwritten.

On the bottom of the page the page number of the novel is indicated as 216.

Gideon Planish joins, with the help of H. Sanderson Sanderson-Smith, a declared opponent of democracy, who later in the novel gets jailed as a Nazi agent, the CCCCC (Citizens’ Conference on Constitutional Crises in the Commonwealth, also known as Cizkon), based in Washington, DC. He then becomes “Directive Secretary of the DDD – the Dynamos of Democratic Direction,”83 serving again in an administrative role as the largely invisible, yet most important agent behind each such group.84 In the meanwhile, Gideon Planish had also come to be considered – without the slightest insight – an “expert on Eskimos,”85 thanks to his work for the Association to Promote Eskimo Culture. A “quiet man” listening, toward the end of the novel, to one of Gideon Planish’s final speeches for the DDD again connects Lewis’ 1943-novel also explicitly to his earlier political critique of philanthropy: “[T]he one thing that might break down American Democracy was the hysterical efficiency with which these pressure groups crusaded to seize all the benefits of that Democracy for themselves.”86 The quiet man, in a climactic monologue, goes on to formulate a blistering assessment of the “private armies led by devout fanatics,” and ends his thoughts in a patriotic prayer:

God save poor America, this quiet man thought, from all the zealous and the professionally idealistic, from eloquent women and generous sponsors and administrative ex-preachers and natural-born Leaders and Napoleonic newspaper executives and all the people who like to make long telephone calls and write inspirational memoranda.87

The last, pivotal, and truly brilliant part of the novel plays mostly in New York, satirically depicting the standoff between Isolationists and Internationalists, non-Interventionists and Interventionists, in the days leading toward December 7, 1941 and the attack on Pearl Harbor, after which the DDD collapses and the story of Gideon Planish ends. The author himself, in 1943 apparently had radically changed course once more, jumping from a position of pacifist isolationism toward blunt interventionism. At least in his novel, Lewis shows clear sympathies for the character of Gideon Planish’s daughter Carrie and a character from the Midwest called Mr. Johnson, who are in favor of effective military action instead of wasting time with further memoranda.88 The head of the DDD Colonel Marduc, instead immediately starts plotting to produce even more gray literature, ordering Gideon Planish to work out “[t]he Marduc Plan, […] reduce ’em [Germany] to the small separate kingdoms and duchies that they were before 1870 – a lot of small weak states. […] Send ’em all [the powerhouses] a mimeographed bulletin tomorrow and remind ’em that we warned ’em about this Pearl Harbor danger months ago. Months!”89