1. Introduction

Challenges in developing English speaking skills arise from various factors including fear of making mistakes, anxiety, lack of self-confidence, linguistic limitations, motivational issues, and classroom-related factors (Chand, Reference Chand2021). These constraints hinder opportunities for English as a foreign language (EFL) learners to engage in adequate speaking practice during class sessions. Consequently, these speaking challenges discourage learners from engaging in verbal communication, thereby hindering the enhancement of their speaking abilities (Fathi, Rahimi & Derakhshan, Reference Fathi, Rahimi and Derakhshan2024). Given these challenges, researchers have explored various pedagogical approaches to support students in developing their speaking skills.

Considerable research has investigated pedagogical approaches aimed at enhancing speaking skills, with studies indicating that collaborative learning (CL) has a beneficial effect on students’ proficiency in spoken English (Butarbutar, Reference Butarbutar2025; Ko & Lim, Reference Ko and Lim2022). CL operates on the premise that learning is inherently social, facilitated by learners engaging in dialogue among themselves, as it is through this interaction that learning takes place (Pattanpichet, Reference Pattanpichet2011).

Despite its benefits, CL encounters challenges, especially in fostering active engagement among members. These challenges are compounded when group members have limited English proficiency, resulting in misunderstandings when engagement is lacking. Furthermore, problems arise during pair work when one member becomes passive or reluctant to engage in interactive tasks, impacting the overall effectiveness of the activity (Govindasamy & Shah, Reference Govindasamy and Shah2020) since lack of interaction is a main factor for engagement. A learning type is considered “collaborative,” following a dyadic (or group) interaction pattern, where role relationships among members are characterized by moderate to high levels of equality and mutual involvement (Storch, Reference Storch2002).

Virtual assistants, such as artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots, can resolve learning interaction in CL. Intelligent chatbots offer various speaking activities, including practicing conversations, grammar exercises, and activities to enhance vocabulary (Hsu, Chen & Yu, Reference Hsu, Chen and Yu2023; Yang, Kim, Lee & Shin, Reference Yang, Kim, Lee and Shin2022). The AI virtual assistant enhances the authenticity and naturalness of interactions between EFL learners and chatbots (Pentina, Hancock & Xie, Reference Pentina, Hancock and Xie2023). In practice, EFL learners can effectively engage and interact with intelligent chatbots by completing writing tasks, verbally posing questions, and receiving feedback through the chatbots’ responses (Walker & White, Reference Walker and White2013).

While numerous scholars have recognized the beneficial impact of chatbots in enhancing engagement and speaking skills (Guo, Zhong, Li & Chu, Reference Guo, Zhong, Li and Chu2024; Jeon, Reference Jeon2023, Reference Jeon2024), there remains a scarcity of research investigating the effects of intelligent chatbot–supported CL on student engagement and the speaking proficiency of EFL learners. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the influence of CL supported by intelligent chatbots on student engagement and proficiency in English speaking. We investigated the effects of intelligent chatbot–supported CL in creating a simulated yet interactive English speaking environment, as well as the extent to which such activities enhanced student engagement and the speaking skills of EFL learners.

2. Literature review

2.1. Integrating intelligent chatbots in collaborative learning

CL begins with active interactions among learners with each other, leading to cognitive changes in the learner. CL is an instructional approach where small groups of learners work together toward a common goal, exploring particular topics or enhancing their skills. CL is based on the constructivist learning theory, which highlights that learning and constructing knowledge are affected by interaction and collaboration (Molinillo, Aguilar-Illescas, Anaya-Sánchez & Vallespín-Arán, Reference Molinillo, Aguilar-Illescas, Anaya-Sánchez and Vallespín-Arán2018). In the CL setting, learners face social and emotional challenges as they engage with diverse viewpoints, requiring them to articulate and defend their ideas. This process helps learners develop personalized conceptual frameworks, moving beyond sole reliance on expert or textual frameworks (Tan, Lee & Lee, Reference Tan, Lee and Lee2022).

CL requires group members to individually contribute information and resources, enhancing ideas through peer engagement and advancing collective knowledge at the group level. Within this framework, group discussions play a pivotal role as they provide opportunities for learners to interact, share perspectives, and co-construct knowledge. Knowledge formation progresses from individual understanding to peer interactions, ultimately culminating in group knowledge (Ouyang et al., Reference Ouyang, Wu, Zhang, Xu, Zheng and Cukurova2023). Effective CL involves co-constructing new knowledge that surpasses individual knowledge by integrating diverse viewpoints and ideas. Successful collaboration does not happen spontaneously (Deiglmayr & Schalk, Reference Deiglmayr and Schalk2015); it requires interdependence and connectedness among learners to foster interactive collaboration and achieve learning goals.

The theory of distributed cognition (Hutchins, Reference Hutchins1995) suggests that cognition involves interactions not only with people of diverse expertise but also with tools in the environment that provide additional cognitive resources. Intelligent chatbots, as external tools, help learners acquire new languages, such as English, through interactions (Fryer, Nakao & Thompson, Reference Fryer, Nakao and Thompson2019; Yang, Kim, Lee & Shin, Reference Yang, Kim, Lee and Shin2022). In CL environments where spoken English is used, anxious students with weaker English skills often express dissatisfaction with interruptions from impatient peers, impacting their self-confidence (Deiglmayr & Schalk, Reference Deiglmayr and Schalk2015; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Ramachandran, Singh, Tek, Yunus and Mulyadi2020). Hence, many educators in higher education institutions are exploring technologies like chatbots to provide students with personalized supports (Baskara, Reference Baskara2023) and facilitate CL among them (Al-Rahmi, Othman & Yusuf, Reference Al-Rahmi, Othman and Yusuf2015).

AI’s role in CL has emerged as a recent phenomenon, as highlighted in systematic reviews conducted by Ji, Han and Ko (Reference Ji, Han and Ko2023) and Tan et al. (Reference Tan, Lee and Lee2022). Among the technological advancements, chatbots designed to interact with human users demonstrate significant potential for enhancing English speaking skills (Du & Daniel, Reference Du and Daniel2024). This innovation contributes to the creation of an environment where students are increasingly engaged in using English (Belda-Medina & Calvo-Ferrer, Reference Belda-Medina and Calvo-Ferrer2022). Intelligent chatbots have the capability to offer information to every learner right from the start, offering the advantage that each learner can develop an initial understanding of the topic to be learned, which they can then expand upon through collaboration with peers, providing a foundation for communication among collaborators. In such circumstances, chatbots can offer personalized support for students, provide feedback on student work (Huang, Hew & Fryer, Reference Huang, Hew and Fryer2022), and facilitate group discussions and collaborations (Kim, Eun, Oh, Suh & Lee, Reference Kim, Eun, Oh, Suh and Lee2020, Kim, Eun, Seering & Lee, Reference Kim, Eun, Seering and Lee2021).

2.2. Chatbots and speaking skills

The primary objective of learning EFL speaking skills is to achieve effective communication in the target language. This involves the ability to both comprehend and convey information accurately (Ji, Reference Ji2023). Speaking English is a complex task that requires proficiency in key components such as pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary, fluency, and coherence. Core speaking skills involve developing both aural skills to comprehend spoken language in real time and oral skills to produce speech fluently. Fluency in spoken English is regarded as a key measure of language acquisition and serves as an essential indicator of EFL learners’ overall language proficiency (Du & Daniel, Reference Du and Daniel2024). Achieving such fluency involves not only accurate language use but also the ability to structure and organize the oral text while effectively managing the flow of speech (Burns, Reference Burns2019). EFL learners are often encouraged to produce coherent and logically connected speech, as fragmented ideas can be challenging for listeners to follow (Tsunemoto & Trofimovich, Reference Tsunemoto and Trofimovich2024). Meanwhile, EFL learners often have limited opportunities to engage in meaningful speaking practice within educational settings, and their exposure to the target language beyond the classroom is minimal (Ericsson, Sofkova Hashemi & Lundin, Reference Ericsson, Sofkova Hashemi and Lundin2023). Therefore, creating meaningful opportunities to practice spoken English, particularly through interactive dialogues or conversations, is essential for supporting their language development.

Teachers can use educational technology to foster EFL learners’ speaking skills autonomously. Recently, chatbots have emerged as a valuable tool for L2/FL learning, sparking renewed interest in EFL speaking instruction. Chatbots can create an authentic learning environment where EFL learners engage in communication and practice language production (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Hew and Fryer2022). The chatbot offered personalized instruction, providing real-time feedback and corrections based on learners’ input. In Fathi et al.’s (Reference Fathi, Rahimi and Derakhshan2024) study, EFL learners used AI-driven chatbots for interactive speaking activities, enhancing their speaking skills. These chatbots create dynamic learning environments that support conversation practice, grammar exercises, and vocabulary building, simulating real-life communication. Moreover, Du and Daniel (Reference Du and Daniel2024), in their systematic review, reported that the use of AI chatbots in EFL speaking instruction aims to accelerate the English learning process and support students in achieving course goals. Their study offers valuable insights into the role of AI chatbots in improving students’ EFL speaking performance.

2.3. Promoting student engagement

Researchers have widely explored the potential of engagement to promote learning. Engagement involves students actively advancing their learning by their actions, thoughts, emotions, and interactions (Fredricks, Blumenfeld & Paris, Reference Fredricks, Blumenfeld and Paris2004). Bond, Buntins, Bedenlier, Zawacki-Richter and Kerres (Reference Bond, Buntins, Bedenlier, Zawacki-Richter and Kerres2020) described engagement as the level of vigor and effort students invest in their learning environment across a period, influenced by behavior, cognition, and emotions. Meanwhile, some noted that student engagement refers to how actively students involve themselves in activities like classroom learning, participating in enrichment educational programs, seeking help from their teachers, or collaborating with peers (Oga-Baldwin, Reference Oga-Baldwin2019; Reeve & Tseng, Reference Reeve and Tseng2011).

Current research on engagement has predominantly focused on forecasting student achievement. In numerous research studies, engagement has been conceptualized as students’ active participation in classroom activities aimed at achieving learning objectives, such as increased academic achievement (Finn & Zimmer, Reference Finn, Zimmer, Christenson, Reschly and Wylie2012; Fredricks et al., Reference Fredricks, Blumenfeld and Paris2004). Contextual elements, environmental shifts, persistence, time management, and planning are perceived as adaptable indicators and factors of engagement (Fredricks et al., Reference Fredricks, Blumenfeld and Paris2004; Martin, Reference Martin2007). Some researchers view that engagement involves both behavior and emotion (Skinner, Reference Skinner, Wentzel and Miele2016), while others propose a three-dimensional model encompassing cognitive, behavioral, and emotional aspects (Bond et al., Reference Bond, Buntins, Bedenlier, Zawacki-Richter and Kerres2020; Fredricks et al., Reference Fredricks, Blumenfeld and Paris2004; Skinner, Reference Skinner, Wentzel and Miele2016).

Behavioral engagement involves the persistent performance of on-task or off-task actions by learners during their involvement in academic activities (Fredricks et al., Reference Fredricks, Blumenfeld and Paris2004). Behavior represents the most observable and identifiable indicators of engagement. Body language, eye contact, and responsiveness to instructions all convey the essential aspects of behavioral engagement (Oga-Baldwin, Reference Oga-Baldwin2019). Emotional engagement refers to students’ enthusiastic and positive responses to their learning experiences, which impact their willingness to accomplish tasks (Fredricks et al., Reference Fredricks, Blumenfeld and Paris2004). Cognitive engagement involves students utilizing subject-specific knowledge and disciplinary practices, and dedicating cognitive energy to understand concepts, acquire information, and develop the skills necessary to complete tasks (Gresalfi & Barab, Reference Gresalfi and Barab2011). Cognitive engagement is primarily evident in the quality of the produced work: Does it reflect active thought, employ the language taught in class, and exhibit an understanding of the language (Oga-Baldwin, Reference Oga-Baldwin2019)?

Engagement is the goal most teachers envision for an ideal classroom environment, especially in English classes. Teachers aim for students to listen and read attentively, retain vocabulary and grammar, compose well-structured sentences and paragraphs, and actively converse with peers (Oga-Baldwin, Reference Oga-Baldwin2019). In EFL speaking classes, assessing engagement is crucial as it helps learners initiate cognitive processes related to form–meaning connections, enhancing language absorption (Aubrey, King & Almukhaild, Reference Aubrey, King and Almukhaild2022). Hence, in measuring student engagement, it is essential to consider that high-quality engagement involves behavioral, emotional, and cognitive elements, which are interconnected and influence each other. It is challenging for students’ emotions and thoughts to progress positively without active participation in classroom tasks (Oga-Baldwin, Reference Oga-Baldwin2019).

Engaging students in an EFL speaking class can be challenging for many teachers. Often, students remain silent due to a lack of self-confidence in their English proficiency, minimal oral involvement, anxiety, and social inhibition (Bahar, Purwati & Setiawan, Reference Bahar and Setiawan2022; Maher & King, Reference Maher and King2022). Low student engagement is a major concern, with only a few, usually in the front rows, actively participating (Yang, Zhou & Hu, Reference Yang, Zhou and Hu2022). This issue is partly due to large class sizes and lecture-heavy instructional methods, which contrast with the belief that effective language instruction requires interactive methods that actively engage students in using the target language.

Prior research has demonstrated that chatbots play a significant role in increasing student engagement in English speaking activities. Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Zhong, Li and Chu2024) found that chatbots assist students in debate preparation by fostering engagement and increasing the benefits of the debate experience. Similarly, Jeon (Reference Jeon2024) highlighted how chatbots facilitate EFL students’ participation in speaking activities, promoting engagement. Additionally, Jeon (Reference Jeon2023) observed that EFL learners who interacted with chatbots engaged in more open-ended dialogues, allowing them to recognize and produce unfamiliar vocabulary.

2.4. Identifying research gaps

The literature review on intelligent chatbots as learning tools highlights their potential to boost student engagement in English speaking environments. Higher engagement levels are linked to better academic outcomes, such as improved achievement (Finn & Zimmer, Reference Finn, Zimmer, Christenson, Reschly and Wylie2012). Chatbots can serve as scaffolding tools, aiding in information organization and enhancing EFL speaking skills in CL activities. However, research on the benefits of chatbot-supported CL for student engagement and speaking skills is limited, particularly among EFL learners in Indonesia. This study aims to fill this gap by investigating the effect of intelligent chatbot–supported CL on student engagement and speaking skills, addressing three research questions:

-

1. Do students who engage in intelligent chatbot–supported CL show significant improvements in engagement and speaking skills from pretest to posttest compared to those engaged in conventional CL?

-

2. To what extent does the CL aspect influence student engagement (behavioral, emotional, and cognitive) in the proposed learning strategy with chatbot-supported CL?

-

3. To what extent does student engagement (behavioral, emotional, and cognitive) influence student speaking skills in the proposed learning strategy with chatbot-supported CL?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

The study employed a convenience sample comprising two groups of first-year undergraduate students (N = 75; 16% male, 84% female) enrolled in an EFL speaking course at a state university in Indonesia. Students were divided into the experimental group (n = 39), which engaged in CL supported by intelligent chatbots, and the control group (n = 36), which participated in conventional CL without chatbot assistance. Both groups were taught by the same teacher in a Casual Conversation course, using identical materials and evaluations.

Students’ self-reported English proficiency levels varied: 12% were beginners, 28% were at the elementary level, and 60% were at the intermediate-low level. Outside the classroom, 68% seldom used English in daily activities. Regarding online English learning, 51% participated less than three times a week, 40% more than three times a week, and only 9% engaged daily. These data were collected through a preliminary background questionnaire before distributing the engagement questionnaire. Analyses of the background information indicate that, while the students had a basic level of English proficiency sufficient for simple communication and some experience in technology-supported EFL learning, they remained relatively passive in practicing spoken English, whether in face-to-face settings or through digital platforms.

3.2. Experimental procedure

Before the experiment, the students were briefed on the procedure, signed a consent form, and completed pretests. The experiment consisted of weekly 100-minute sessions over four weeks. Conducted in the Casual Conversation course, the experiment aimed to help students structure information and engage in casual conversation to improve their speaking skills. Four topics were presented to the students in sequence each week. This study explored the effectiveness of intelligent chatbot–supported CL in achieving the goals in a speaking-focused classroom. Figure 1 illustrates the experimental procedure.

Figure 1. Experimental procedure.

The students in both the control and experimental groups were divided into teams of six for discussions. They explored the same learning topics, introduced by the teacher – whose role in this study was limited to course delivery – through scaffolding talks to stimulate ideas (see Figure 2). These topics covered real-life situations commonly faced by EFL learners in English speaking environments. Initially, all students completed an engagement questionnaire designed by Reeve and Tseng (Reference Reeve and Tseng2011) to gauge their engagement during the speaking class. In the following meeting, their initial speaking proficiency was assessed using the IELTS rubric. For the subsequent four weeks, the control group students used conventional CL to discuss the topics, while the experimental group engaged in a CL supported by intelligent chatbots.

Figure 2. Learning scenarios.

For this experiment, we used Replika, an AI chatbot that facilitates spoken conversations through a chatbot interface. Designed for personalized conversations, Replika acts as a virtual friendship companion, engaging users in casual dialogue. All students in the experimental group were instructed to download, install, and subscribe to this application on their mobile devices, tablets, or laptops through the Google Play Store or Replika’s online portal (https://my.replika.ai/). By subscribing, the students accessed voice-based conversations with their intelligent partners. Replika, available exclusively in English, serves as a resource for natural and authentic English, making it ideal for assisting EFL students in improving their speaking skills in the Casual Conversation course. Using Replika’s voice mode feature, the students could practice English communication at their convenience, enhancing their engagement in English conversation through self-directed learning and extensive practice.

Throughout the first to the fourth phases of the experiment, each student first reflected on the topic and scaffolding talks and engaged in a 5- to 7-minute written conversation with the help of the chatbot. Students then wrote their responses on paper as a brainstorming guide for their spoken interactions. Next, students had a 5- to 7-minute spoken conversation with the chatbot to improve their spontaneous EFL speaking skills (see Figure 4). Afterward, they discussed their ideas with a peer partner for another 5 to 7 minutes, allowing for further practice and immediate feedback. Finally, students shared their discussed ideas with the group or the entire class, promoting active articulation of thoughts. This structured process fostered students’ engagement, emotions, and behavior. Meanwhile, the control group students learned the topic without the assistance of intelligent chatbots as conversation partners. They reflected individually on the topic for 5 to 7 minutes without chatbot assistance for brainstorming. Subsequently, they participated in a 10- to 12-minute conversation with their peer, without involving themselves in oral practice with a chatbot to ready themselves for the upcoming sharing phase. At the end of the experiment, all students in both groups completed learning engagement questionnaires and speaking proficiency posttests, as well as the CL questionnaire for the experimental group only. Figures 2 and 3 depict an overview of learning scenarios and the intelligent chatbot–assisted CL situation, respectively.

Figure 3. Intelligent chatbot–assisted collaborative learning situation.

Figure 4. Examples of written and spoken conversations with chatbots.

3.3. Model and hypotheses

The present study utilizes two models of analysis: group comparison and individual difference analysis. Group comparison analysis aims to ascertain if the CL supported by intelligent chatbots significantly impacts student engagement and speaking skills (RQ1). Conversely, individual difference analysis examines if CL supported by intelligent chatbots affects student engagement (RQ2) and if student engagement influences speaking skills (RQ3).

3.3.1. Group comparison analysis

Within the group comparison analysis, the instructional strategy served as the independent variable, with conventional CL for the control group and intelligent chatbot–supported CL for the experimental group. Meanwhile, student engagement and speaking skills were the dependent variables. The following two hypotheses were posed:

-

• H1: The experimental group students improve significantly in terms of engagement as compared to those in the control group.

-

• H2: The experimental group students improve significantly in terms of speaking skills as compared to those in the control group.

3.3.2. Individual difference analysis

Successful group work requires members to function harmoniously. Simply assigning students to groups and instructing them to collaborate may not be enough to foster positive interdependence. Technology-enhanced group learning exemplifies such interdependencies. Using technology such as chatbots as learning aids in collaborative environments can facilitate knowledge sharing and promote discussion and interaction skills (da Silveira Colissi, Vieira, Mascardi & Bordini, Reference da Silveira Colissi, Vieira, Mascardi, Bordini, Stephanidis, Antona and Ntoa2021). Previous studies have examined the impact of technology on students’ engagement and performance (Agyei & Voogt, Reference Agyei and Voogt2011; Bouchrika, Harrati, Wanick & Wills, Reference Bouchrika, Harrati, Wanick and Wills2021) and the relationship between CL and student engagement in classroom learning experiences (Al-Rahmi et al., Reference Al-Rahmi, Othman and Yusuf2015; Qureshi, Khaskheli, Qureshi, Raza & Yousufi, Reference Qureshi, Khaskheli, Qureshi, Raza and Yousufi2023). A higher level of exchange and interaction with other students during CL leads to a greater degree of student engagement (Molinillo et al., Reference Molinillo, Aguilar-Illescas, Anaya-Sánchez and Vallespín-Arán2018). Therefore, we hypothesize that incorporating intelligent chatbots to support CL positively affects cognitive, emotional, and behavioral engagement:

-

• H3: CL as a result of incorporating chatbots positively affects behavioral engagement.

-

• H4: CL as a result of incorporating chatbots positively affects emotional engagement.

-

• H5: CL as a result of incorporating chatbots positively affects cognitive engagement.

Previous studies have explored how engagement impacts students’ speaking skills (Bagheri & Mohamadi Zenouzagh, Reference Bagheri and Mohamadi Zenouzagh2021; Huang, Reference Huang2021). Language learning occurs through interaction and collaborative construction of concepts among speakers of varying proficiency levels. Language immersion, involving cooperative practice with others, enhances learning. Improvement in speaking skills requires active engagement and deliberate practice in educational activities. Increased participation and involvement in educational tasks, known as engagement, is likely to enhance speaking skills, particularly benefiting those who engage in active discussions and express themselves confidently (Uztosun, Skinner & Cadorath, Reference Uztosun, Skinner and Cadorath2018). Teachers should therefore create instructional environments that support the development of students’ speaking skills:

-

• H6: Behavioral engagement as a result of incorporating chatbots positively affects speaking skills.

-

• H7: Emotional engagement as a result of incorporating chatbots positively affects speaking skills.

-

• H8: Cognitive engagement as a result of incorporating chatbots positively affects speaking skills.

The individual difference analysis focused solely on the experimental group, aligning with one of the study’s objectives, which is to investigate the influence of intelligent chatbot–supported CL on students’ engagement and speaking skills.

3.4. Instrument

In this study, the survey questionnaire items of CL were adopted and adapted from Al-Rahmi and Othman’s (Reference Al-Rahmi and Othman2013), Sarwar, Zulfiqar, Aziz and Ejaz Chandia’s (Reference Sarwar, Zulfiqar, Aziz and Ejaz Chandia2019), and So and Brush’s (Reference So and Brush2008) studies. The questionnaire consisted of five items that were scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The CL questionnaire was solely administered to participants within the experimental group (see Appendix 1 in the supplementary material).

The measurement of student engagement encompassed three constructs, as per Reeve and Tseng (Reference Reeve and Tseng2011). Each construct was evaluated using varying numbers of adapting items: four for behavioral engagement (BE), three for emotional engagement (EE), and seven for cognitive engagement (CE). Those items were rated using a 5-point Likert scale, with values ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). BE reflected the level of student interest in and effort allocated to the task. EE was evaluated based on students’ emotional states. CE was measured by students’ level of involvement in the learning activity.

The reliability of the instrument was examined using a non-parametric approach appropriate for a small sample size. The chi-square goodness-of-fit test indicated that most items did not significantly differ from the expected distribution (p > .05), suggesting that participants’ responses were relatively balanced. Furthermore, the Mann–Whitney U test revealed significant differences between groups across all constructs (CL, BE, EE, CE; p < .05), indicating a systematic and non-random response pattern. These results collectively suggest that the instrument demonstrated stable and consistent responses, confirming its reliability (see Appendix 2 and 3 in the supplementary material).

To assess the students’ speaking proficiency, they underwent both pre- and post-speaking tests, featuring questions encompassing three topics – favorite food, scenic destinations, and traveling – aimed at measuring aspects of their speaking skills, such as “Are there any food you don’t like? Why?”; “How do you choose your holiday destination?”; “What do you usually do when you visit a new place?” The speaking test involved a single integrated task in which the students responded to questions that collectively covered the three topics. Each participant was allotted approximately 5 to 7 minutes for the test, during which it was advantageous for them to utilize the time effectively by speaking as much as possible. They were instructed to respond to each question according to the provided instructions. The examination process was recorded to ensure fairness in the speaking test. The scoring process was conducted by two experienced English teachers from the university’s English Department, both of whom possessed over a decade of teaching experience and were currently teaching speaking courses at the university. The students’ speaking proficiency was assessed using the standardized IELTS speaking band descriptors from 0 to 9, which include criteria of fluency and coherence, lexical resource, grammatical range and accuracy, and pronunciation. The interrater reliability for pre-speaking and post-speaking assessments, measured using Cohen’s kappa (0.65 and 0.68, respectively), confirmed the reliability of the scores. Meanwhile, only post-speaking test scores were used in the linear regression analysis to examine relationships between variables.

3.5. Data collection and analysis

Data on students’ engagement and speaking skills were collected both before and after the intervention. Additionally, data on the experimental group’s perception of CL activities were gathered post-treatment. Prior to data collection, all students were assured that their participation was solely for educational research purposes. They were also informed that their qualifications would not affect their grades.

The group comparison analysis began with a normality test to decide between a parametric or non-parametric test. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test yielded results indicating that all data followed a normal distribution. Thus, this study opted for a parametric test, specifically a repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA). In addition, the individual difference analysis was applied to the experimental group data, and it was examined using a linear regression analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Group comparison

4.1.1. Engagement

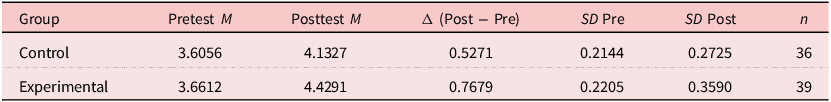

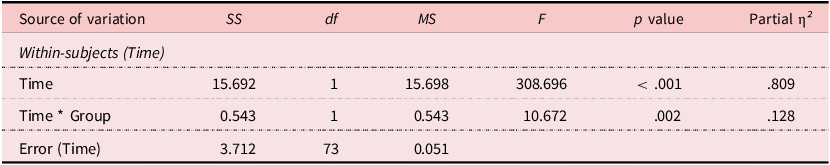

In this experiment, RM-ANOVA was employed to examine the difference in student engagement between the two groups. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the pretest and posttest engagement scores of both groups.

Table 1. Descriptive results of the two groups’ pretest and posttest scores for engagement

Following the implementation of CL utilizing the intelligent chatbots, RM-ANOVA was conducted to analyze the differences in engagement scores between the two groups across the pretest and posttest.

Table 2 shows that the results of the RM-ANOVA revealed a highly significant increase in engagement from the pretest to the posttest, F(1, 73) = 308.696, p < .001, η2 = .809. The interaction effect between time and group was also statistically significant, F(1, 73) = 10.672, p < .01, η² = .128, showing a large effect size, indicating that the change in engagement scores from pretest to posttest differed significantly between the groups. As presented in Table 1, descriptive statistics showed that the experimental group’s engagement scores increased from 3.66 to 4.43 (a gain of 0.77), whereas the control group’s scores rose from 3.61 to 4.13 (a gain of 0.53). These results demonstrate that the experimental group experienced significantly greater engagement levels after participating in the CL supported by chatbots, in comparison to the control group. Therefore, H1 was supported.

Table 2. The RM-ANOVA results for student engagement

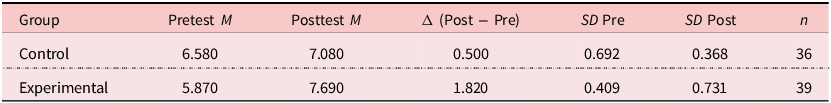

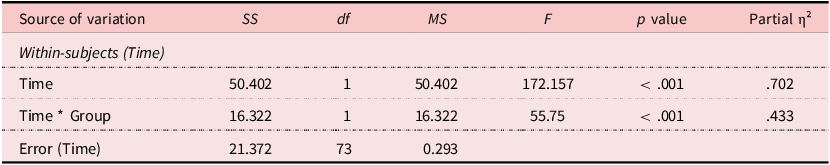

4.1.2. Speaking skills

The results of the RM-ANOVA in Table 4 revealed a significant difference in speaking skill scores between the pretest and posttest, F(1, 73) = 172.157, p < .001, η² = .702. Furthermore, there was a significant interaction between time and group, F(1, 73) = 55.750, p < .001, η² = .433, showing a large effect size, indicating that the improvement in speaking scores was significantly greater in the treatment group compared to the control group. As shown in Table 3, descriptive analysis showed an increase in speaking skill scores from pretest to posttest in both groups. The experimental group improved from M = 5.87, SD = 0.41, to M = 7.69, SD = 0.73, while the control group improved from M = 6.58, SD = 0.69, to M = 7.08, SD = 0.37. Although both groups demonstrated gains in speaking performance, the experimental group exhibited a more substantial improvement, which is further supported by the significant time × group interaction observed in the RM-ANOVA results, thus supporting H2.

Table 3. Descriptive results of the two groups’ pretest and posttest scores for speaking skills

Table 4. The RM-ANOVA results for speaking skills

4.2. Individual difference analysis

4.2.1. Linear regression analysis

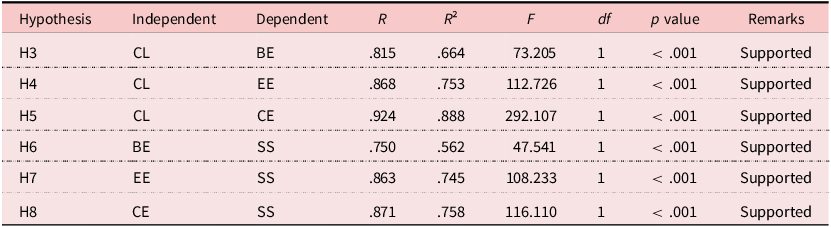

To examine the effects of CL facilitated by chatbot integration on BE, EE, and CE, as well as the influence of BE, EE, and CE on speaking skills, linear regression analysis was conducted.

The linear regression model was analyzed for testing the proposed hypotheses by calculating the statistical significance of each hypothesis, the R, and R² values to measure the strength of the relationships between independent and dependent variables. Table 5 indicates that CL has a significant relationship with all components of engagement, and all components of engagement also have a significant relationship with speaking skills. Hence, H3, H4, H5, H6, H7, and H8 were accepted.

Table 5. Results of the linear regression model hypotheses

Note. CL = collaborative learning; BE = behavioral engagement; EE = emotional engagement; CE = cognitive engagement; SS = speaking skills.

As presented in Table 5, the regression analysis revealed that CL exhibited a significant relationship with all three types of student engagement. Specifically, CL was significantly associated with BE (R = .815, p < .001), accounting for 66.4% of its variance (R² = .664). A stronger relationship was demonstrated on EE (R = .868, p < .001), with CL explaining 75.3% of its variance (R² = .753). The most substantial relationship, however, was found on CE (R = .924, p < .001), where 88.8% of the variance was explained (R² = .888), indicating that CL was particularly effective in enhancing students’ cognitive involvement in learning. Furthermore, Figure 5 shows that in addition to these three significant relationships, the strongest relationship in terms of the coefficient of determination is between CL and CE (R 2 = .888), suggesting that CL most effectively enhances students’ CE.

Figure 5. Linear relationships of collaborative learning–engagement and engagement–speaking skills.

Additionally, there were significant relationships between all three types of engagement and speaking skills. BE showed a significant relationship with SS (R = .750, p < .001), explaining 56.2% of the variance (R² = .562). EE demonstrated a stronger relationship (R = .863, p < .001), accounting for 74.5% of the variance (R² = .745). Notably, CE exerted the strongest relationship with SS (R = .871, p < .001), explaining 75.8% of the variance (R² = .758). These findings underscore the critical role of student engagement, particularly CE, as a mediating mechanism through which CL enhances students’ speaking performance. Consistent with the regression results, Figure 5 further confirms that the strongest relationship, in terms of the coefficient of determination, was observed between CE and SS (R² = .758), suggesting that CE served as the most powerful determinant of students’ speaking proficiency.

5. Discussion

5.1. The effects of chatbot-supported CL on engagement and speaking skills

The aim of the first research question is to examine the effect of intelligent chatbot–supported CL on students’ engagement and speaking skills. The results shown in Tables 2 and 4 indicate chatbot-supported CL positively impacts students’ engagement and EFL speaking skills. The students in the experimental group outperformed the students in the control group on engagement (H1) and speaking skills (H2).

Incorporating chatbots into CL as a preparation tool for student discussions can effectively supplement student-to-student English speaking practice. We found that combining chatbots with human learning companions significantly enhanced student engagement in discussions and improved their English speaking more effectively in the experimental group compared to the control group (Tables 1 and 3). These findings align with those of Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Zhong, Li and Chu2024) and Hsu et al. (Reference Hsu, Chen and Yu2023), which indicate that the use of chatbots in English learning can enhance students’ engagement and speaking skills. Students often require scaffolding to engage in and advance through active and effective CL (Näykki, Isohätälä & Järvelä, Reference Näykki, Isohätälä and Järvelä2021). Therefore, chatbots as a learning aid to brainstorm ideas were integrated to assist students in engaging in CL activities, providing them with opportunities to enhance their learning through detailed elaboration of each other’s understanding to reach a common goal. In CL activities, the students organized their thoughts on the assigned topics by conversing with chatbots and then discussing their responses with their peers. This process simulated natural spoken communication, resulting in increased peer accountability and greater engagement with the language materials. As a resource for learning natural and authentic English, Replika exposes learners to real-life English conversations, enabling them to practice English that is naturally spoken and contextually authentic (Belda-Medina & Calvo-Ferrer, Reference Belda-Medina and Calvo-Ferrer2022). The chatbots can offer feedback to enhance engagement and interaction patterns (Tan et al., Reference Tan, Lee and Lee2022), leading to more effective CL.

Additionally, chatbot-supported CL enhances students’ speaking skills (see Table 4). In this approach, the students engaged in natural and authentic speaking exercises with the chatbots before interacting with peers and presenting their responses to the class. While conversing with the chatbots, the students could prepare and monitor their language use (Walker & White, Reference Walker and White2013). Throughout the conversation, the students interacted with their chatbots related to the discussion topics, thereby developing a more comprehensive understanding of the topics. These conversation activities with the chatbots effectively equipped the students for subsequent speaking tasks and contributed to their improved English speaking (Du & Daniel, Reference Du and Daniel2024). Chatbots can assist students in enhancing their EFL speaking skills by offering structured linguistic input. Through their fluent speech, accurate grammar, and contextually relevant expressions, chatbots act as models for students to observe and refine their own utterances, resulting in tangible improvements in their speaking proficiency. Meanwhile, the interaction challenges associated with using chatbots primarily arise from technical issues, such as delayed responses due to internet connectivity problems.

5.2. Influence of chatbot-supported CL on engagement

The second research question focused on how chatbot-supported CL influences engagement. Table 5 illustrates that chatbot-supported CL influences behavioral (H3), emotional (H4), and cognitive engagement (H5). CL necessitates active student engagement and is characterized by the integration of behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement (Sinha, Rogat, Adams-Wiggins & Hmelo-Silver, Reference Sinha, Rogat, Adams-Wiggins and Hmelo-Silver2015). Additionally, integrating chatbots into the learning environment can provide students with both emotional and academic support, ultimately enhancing their learning engagement (Huang, Reference Huang2021). Behaviorally, students participating in chatbot-supported CL engaged with chatbots during brainstorming and practice stages, using both written and oral conversations. Engaging with the chatbots allowed the students to generate ideas and receive guidance, preparing them for later pair and group activities. With the chatbots’ assistance, the students were able to actively dedicate their time and effort while having paired and group discussions. This finding aligns with Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Zhong, Li and Chu2024), who emphasized that chatbots can promote students’ engagement in discussions and improve their interactions. Previous research has shown that behavioral engagement encompasses actively participating and being involved in learning activities (Schindler, Burkholder, Morad & Marsh, Reference Schindler, Burkholder, Morad and Marsh2017).

In the area of emotional engagement, chatbot-supported CL led to students’ increased participation and enjoyment in CL activities. The chatbots’ involvement in CL made learning more enjoyable and motivated the students to engage more actively, both in learning and speaking. Additionally, it fostered a relaxed atmosphere, with the students appreciating the innovative way of using the chatbots for learning. When students are emotionally engaged, they are more likely to participate actively in their learning (Molinillo et al., Reference Molinillo, Aguilar-Illescas, Anaya-Sánchez and Vallespín-Arán2018).

Cognitively, chatbot-supported CL helped students generate ideas. The chatbot provided information from the start, allowing each student to develop an initial understanding of the topic, which served as a foundation for collaboration and effective communication. They incorporated the chatbot-suggested ideas as a supplement to their own, then compared and shared these ideas with their peers, enriching their pair and group discussions. These findings align with those of Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Zhong, Li and Chu2024). In addition to stimulating cognitive skills like thinking and reasoning, the chatbots’ conversations helped the students process information thoroughly to achieve their learning goals. These interactions contributed to the improvements in their EFL speaking proficiency and fluency during CL.

5.3. Influence of engagement on speaking skills

Regarding the third research question on the influence of behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement on speaking skills, the significant results indicate that all three types of engagement positively influence students’ speaking abilities (see Table 5). The activity involving the intelligent chatbot–assisted CL learning situation (see Figure 3) required students’ behavioral engagement to support the students’ collaboration and discussions, a result that aligns with Tan et al.’s (Reference Tan, Lee and Lee2022) systematic review. The students who become increasingly engaged with their chatbots, peers, and learning materials transition from a passive to an active, then to a constructive, and finally an interactive mode. This progression leads to an increase in their speaking activities, which subsequently influences their speaking skills.

Additionally, as shown in Table 5, emotional engagement positively influenced students’ speaking skills. For the students, conversing in English with an intelligent chatbot was a new experience. They enjoyed and focused on engaging in dialogues with their chatbots throughout the CL activities. Practicing and interacting with the chatbot in a non-threatening environment could positively impact emotional engagement, particularly benefiting shy or introverted students. These students found it easier to participate in their speaking class and had more time to formulate their ideas with the chatbot’s assistance (Du & Daniel, Reference Du and Daniel2024).

Furthermore, Table 5 demonstrates that cognitive engagement positively influenced students’ speaking skills. By using intelligent chatbots in CL, the students combined their own ideas with chatbot-suggested ones in preparation for discussions with their peers and groups. This chatbot-mediated learning environment fostered greater interaction among students and their group members (Huang, Reference Huang2021). With the chatbot’s assistance as supplementary cognitive resources, the students became active learners, constructing knowledge through interactions with each other. Working together in teams, they contributed to achieving the learning goal and completing the assigned speaking tasks. The results indicated that the students who engaged and interacted with a voice chatbot showed increased communication and participation during CL, ultimately improving their speaking skills.

6. Conclusion

This study explored the impact of intelligent chatbot–supported CL in a speaking-focused Casual Conversation course, investigating students’ engagement and speaking skills within this learning approach. The findings support the integration of chatbots in CL, which helps students engage in speaking English. Face-to-face CL using English can be challenging for students due to communication barriers, lack of cohesion, and misaligned expectations. The factor influencing students’ ability to engage is their English proficiency. One way to support authentic English learning is by providing technology such as chatbots, which enable students to engage in English conversations. Using chatbots as a conversation partner helped students improve their speaking skills. When students receive high-quality input, produce regular output, practice consistently, and receive instruction on language form, they are likely to engage behaviorally, emotionally, and cognitively in learning (Oga-Baldwin, Reference Oga-Baldwin2019). Therefore, students must actively engage in EFL speaking courses for improving their speaking skills, and chatbots can serve as effective and efficient tools to facilitate this engagement in CL. Incorporating chatbot interactions in language classrooms is an effective way to boost EFL students’ engagement and speaking skills. EFL teachers can also integrate chatbots into their speaking courses, as a supplement to conventional interactive speaking activities, to provide students with additional opportunities to practice their speaking skills.

7. Study limitations

This study has limitations. First, the sample, drawn from one specific subject area at a single university, may limit the generalizability of the findings to a broader college student population. The sample consisted of 75 first-year university students. CL is effective due to its flexibility across various class sizes and its ability to foster active involvement among students. In smaller classes, it might be assumed that all students have equal opportunities to participate due to the smaller group size. Meanwhile, participation dynamics can vary significantly between small and large classes. Second, the study duration was relatively short. Future research should consider long-term interventions to examine how student engagement evolves over time.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344025100451

Data availability statement

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

Authorship contribution statement

Ting-Ting Wu: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing; Intan Permata Hapsari: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft; Yueh-Min Huang: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding disclosure statement

This research is partially supported by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, ROC, under Grant No. MOST 110-2511-H-224-003-MY3, MOST 111-2628-H-224-001-MY3, and NSTC 113-2410-H-224-036-MY3.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the National Cheng Kung University Human Research Ethics Committee with No. NCKU HREC-E-110-667-2.

GenAI use disclosure statement

The authors declare no use of Generative AI.

About the authors

Ting-Ting Wu is a distinguished professor in information science and educational technology at the Graduate School of Technological and Vocational Education, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Taiwan. Her fields of expertise include web applications, learning environments, learning educational technology, e-learning, and information and communication technology.

Intan Permata Hapsari is a lecturer in the English Department at Universitas Negeri Semarang, Indonesia. Her current interests are focused on e-learning and intelligent computer-assisted language learning and investigating to what extent they can benefit EFL students in Indonesia.

Yueh-Min Huang is a chair professor in the Department of Engineering Science at the National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan. His research interests include e-learning, multimedia communications, and artificial intelligence.