Introduction

There is no shortage of literature discussing the Eurozone crisis and the deficiencies of the EU's economic architecture in recent years (see, e.g., Dinan Reference Dinan2012; Pisani‐Ferry Reference Pisani‐Ferry2014). The role of ideas and discourse in the managing of the Eurozone crisis has also attracted scholarly attention, albeit with variable degrees of empirical depth (see Schmidt Reference Schmidt2014; Ntampoudi Reference Ntampoudi2014; Borriello & Crespy Reference Borriello and Crespy2015). The literature has produced some important insights into the role of the media in framing a polarised picture, with often conflicting results about the discourse(s) that emerged during the crisis. For instance, a number of studies highlighted a process of ‘othering’ and blaming, with often biblical references to the main protagonists of the crisis as ‘saints’ (creditors) and ‘sinners’ (bail‐out recipients) (Wodak & Angouri Reference Wodak and Angouri2014; Kutter Reference Kutter2014). Others point to ideological cleavages between neo‐Keynesianism and neo‐liberalism in understanding and framing the crisis (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2014). Moreover, the literature has produced mixed results on whether a common ‘European’ discourse has emerged. Some scholars have highlighted predominantly national discourses on the origins of the crisis (cf. Picard Reference Picard2015; Nienstedt et al. Reference Nienstedt, Kepplinger, Quiring and Picard2015), while others have suggested the existence of a more Europeanised narrative with common frames (not least between Spain and Germany) on ‘conditionality’ and ‘competitiveness’, among others (Kaiser & Kleinen‐von Königslöw Reference Kaiser and Kleinen‐von Königslöw2016, Reference Kaiser and Kleinen‐von Königslöw2017).

Yet, much of the existing literature has focused primarily on how the media (e.g., newspaper editorials and reporting) has depicted the crisis, rather than the actual statements made by key policy makers across EU institutions and member states. In addition, most available studies focus on relatively short time segments of the crisis. As a result, our knowledge of the discursive evolution of the EU's bail‐out crisis management over the past eight years remains rather fragmented. This gap manifests itself as both an empirical and methodological puzzle: the challenge is not simply to trace the content of elite discourse, but to identify credible measures that can substantiate claims over its continuity and change.

Driven by these challenges, this article focuses on the evolution of European discourses on the ‘rescue’ of Greece as a crucially important subset of the wider management of the Eurozone crisis. We focus our analysis on discourses by key senior officials involved in the design and implementation of Greece's bail‐out programmes rather than the wider public debate on the fate of Greece, which also included the media and other more specialised epistemic communities. The timeframe of our analysis stretches from the ‘pre‐history’ of the Greek crisis (the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 in the outset of the global financial crisis) to the arrival of the SYRIZA government in January 2015 on an openly hostile ticket to the euro bail‐outs, potentially marking a new phase in the country's relationship with its creditors. By reference to the literatures on Discursive Institutionalism (DI) and Historical Institutionalism (HI), and using an extensive dataset of quotes from Reuters newswires, we argue that elite narratives on the Greek crisis during that period have demonstrated significant volatility. We identify four distinct narrative frames: ‘neglect’, ‘suspicious cooperation’, ‘blame’ and ‘reluctant redemption’. We argue that these frames have been the result of three ‘critical moments’ (materialising into ‘discursive critical junctures’) in 2010, 2011 and 2012, during which intensive media attention on the Greek crisis produced ‘windows of opportunity’ for the (re‐)casting of its communicative discourse. We do not equate these narrative frames (either in terms of content or timing) to the actual EU strategy during the crisis. The latter was shaped by a wider set of parameters (not least by intergovernmental and inter‐institutional bargaining), not all of which fall under the scope of this article. The examination of elite discourses, however, provides crucial insights into how key policy makers responded to the Greek crisis, both in terms of the content of their legitimising narrative and its evolution through important junctures of the crisis.

The Greek crisis through a DI perspective

The role of ideas in political science has attracted a huge body of literature, encompassing many different theoretical perspectives and methodological traditions within the discipline (see, e.g., Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971; Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1990; Sabatier & Jenkins‐Smith Reference Sabatier and Jenkins‐Smith1993). More recently, the literature on DI (Campbell & Pedersen Reference Campbell and Pedersen2001; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008, Reference Schmidt2010, Reference Schmidt2014; Boswell & Hampshire Reference Boswell and Hampshire2016) has sought to recast our understanding of narrative frames and link them to existing scholarship on New Institutionalism (NI) (for a review, see Hall & Taylor Reference Hall and Taylor1996; March & Olsen Reference March and Olsen2005) in the form of a new variant. Schmidt (Reference Schmidt2008: 3) posits that ‘discourse’ allows for a broader understanding of the role of ideas by encompassing not only their content, but also the processes by which they are conveyed and exchanged.

Schmidt distinguishes between coordinative and communicative discourse. The former involves the interaction between epistemic communities (Haas Reference Haas1992) ‘at the centre of policy construction who are involved in the creation, elaboration and justification of policy and programmatic ideas’ (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008: 310). Communicative discourse, on the other hand, is primarily conducted in the realm of politics whereby political actors seek to legitimise policy preferences and ‘sell’ them to the public/electorate (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008: 310). The pattern of interaction between the two types of discourse varies according to circumstance: it can be sequential (with coordinative discourses preceding communicative ones), cyclical (involving a ‘feedback loop’ between the two) or, indeed, disjointed, whereby the two are not ‘in sync’ due to the highly technical or controversial nature of the policy involved. In all cases, the role of political leadership in interweaving coordinative and communicative discourses is paramount. It is this mediation that produces the ‘master discourse’ – the ‘vision of where the polity is, where it is going, and where it ought to go’ (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008: 311).

Critical to the way in which Schmidt has sought to position DI as a distinct variant of NI is her approach to institutional change and the role of ideas within this process. Unlike HI and Sociological Institutionalism, Schmidt's approach is agency‐driven (focusing on ‘sentient’ agents), whereas (unlike Rationalist Institutionalism and HI), ‘institutions’ are defined as ‘internal [to actors] ideational constructs and structures’ (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2010: 16). Hence, institutional change is explained by reference to political actors’ ‘foreground discursive abilities’ to communicate critically about their institutions and ultimately steer them towards change (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008, Reference Schmidt2010).

The interaction between discourse and institutions, however, can also be articulated ‘in the reverse’, focusing on how institutional affiliations can affect processes of discursive continuity and change over time (see, inter alia, Carstensen Reference Carstensen2011a,Reference Carstensenb; Stanley Reference Stanley2012). In order to interrogate the circumstances under which discursive shifts occur, we employ the literature on HI which has emphasised the importance of ‘critical junctures’ as moments where path dependencies or established equilibria are disrupted, giving rise to institutional reconfiguration or the recalibration of interests and social norms (Krasner Reference Krasner1988; Berins‐Collier & Collier Reference Berins‐Collier and Collier1991; Pierson Reference Pierson2000; Capoccia & Kelemen Reference Capoccia and Kelemen2007). Concepts such as ‘critical junctures’ and ‘paradigm shifts’ within the NI tradition are not without their critics, not least because of the difficulty in substantiating them empirically, but also clarifying the underlying causalities behind their emergence (see Thelen & Steinmo Reference Thelen, Steinmo, Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth1992; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2010).

To account for this critique, we define specific conditions for the identification of discursive critical moments and junctures. Critical moments are evidenced by significant peaks in the number of news articles dealing with Greece's financial crisis. The selection of such a quantitative criterion is not fool‐proof and still involves a degree of discretion on our behalf, particularly in deciding how many of these peaks are examined. Yet, this approach allows greater consistency in the identification of critical moments compared with other qualitative criteria (e.g., elections, key European Council meetings) or market data, whose wild fluctuations do, in any case, feature in the media coverage. Critical junctures, on the other hand, are defined by reference to significant fluctuations in the content of the creditors’ discourse as evidenced by the coding system we employ (see methodology below).

This article focuses on the communicative discourse of European elites towards the Greek crisis and does not delve into the coordinative discourse contained in (confidential or otherwise) communications between the protagonists in order to determine policy. Although we recognise the apparent inter‐connection between communicative discourse and chosen policy, we treat the two arenas as analytically distinct. Hence, we urge caution against equating discursive and policy junctures or assuming that the two take place simultaneously or that they are premised on the exact same foundations. Often, discursive shifts can occur either prior to or after major rethinks of policy and/or strategy. In the context of the Greek bail‐out, policy change also involved delicate inter‐institutional and intergovernmental negotiations which complicate the identification of causalities further.

Methodology and data collection

In order to substantiate theoretically informed claims on the continuity and change of the discursive handling of the Greek crisis, we use the English language electronic depository of Reuters newswires (the largest of its kind in the world) to trace the communicative discourse of elite European policy makers from the collapse of Lehman Brothers on 15 September 2008 up to the election of the SYRIZA government in Greece on 25 January 2015, which inaugurated a new phase in Greece's relationship with its creditors and whose discursive implications are still unfolding. We have identified a total of 26 posts (involving 63 individuals) directly involved in the Greek crisis (see Table 1). These include the Heads of Government and Finance Ministers of ten Eurozone members involving both ‘core’ (Germany, France, Netherlands, Finland, Austria)Footnote 1 and ‘periphery’ states (Cyprus, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Spain)Footnote 2 as well as the leaders of key institutions responsible for managing the crisis such as the Director of the IMF; the Presidents of the European Council, the European Central Bank (ECB), the European Commission and the Eurogroup; and the European Commissioner for Financial Affairs.

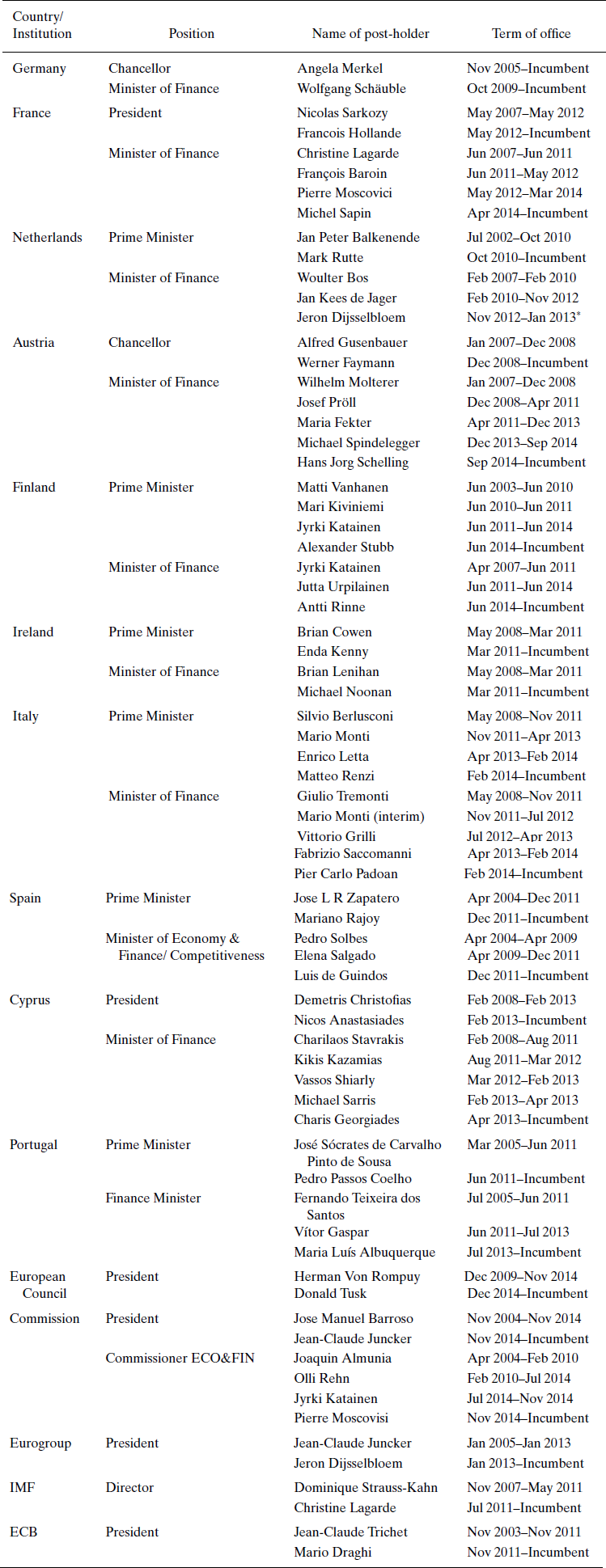

Table 1. List of post‐holders examined, as of 25 January 2015

Notes: *Appointed as Eurogroup President.

Source: Authors’ own calculations.

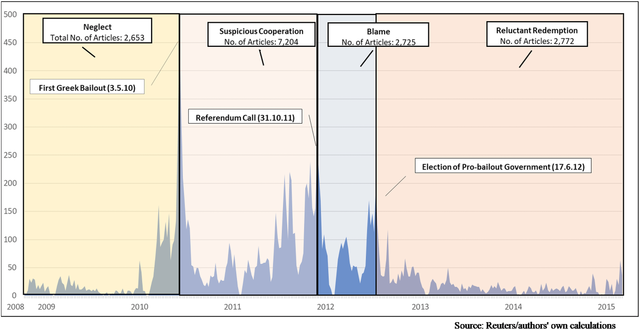

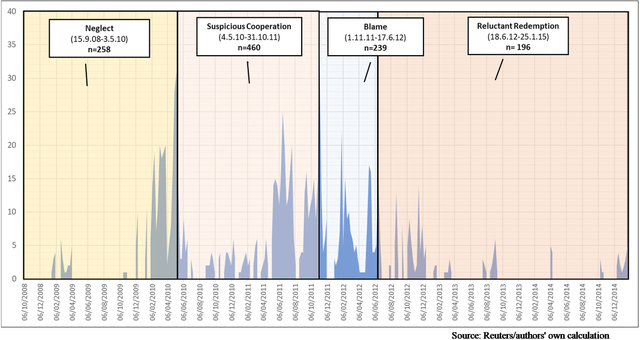

Using searches that contained the terms ‘Greece’, ‘crisis’ and ‘said’ we recovered a total of 15,354 articles from the Reuters archives, published in English (see Figure 1).Footnote 3 Using the names of the 63 individuals identified above we recovered 1,153 unique quotes that made reference to or was an evaluation of the Greek crisis and/or bail‐out(s) (see Figure 2).Footnote 4 Our search did not include the use of synonyms (e.g., ‘Greek’, ‘Hellenic’, ‘Chancellor’) or quotes that were not attributed to a named individual (e.g., ‘German official’).

Figure 1. Number of Reuters articles containing the terms ‘Greece’, ‘Financial’ and ‘Crisis’, per week (Total: 15,354). [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 2. Number of unique quotes on Greece per week (Total: 1,153). [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Instead of using random sampling or seeking to analyse inductively frames or keywords that policy makers use (cf. Kaiser & Kleinen‐von Königslöw Reference Kaiser and Kleinen‐von Königslöw2016, Reference Kaiser and Kleinen‐von Königslöw2017), we opted to code each quote using an ordinal scale between –2 and +2. The value –2 denominates a punitive stance towards Greece. Quotes falling under this classification may make references to Greece's ‘cheating’ and the necessary ‘punishment’ that the EU's response should entail, mainly Greece's exit from the Eurozone (‘Grexit’). References to Greece being a ‘bottomless pit’ or of Greece's Eurozone membership being a ‘mistake’ also denominates strongly negative attitudes. Typically for quotes falling under this category, Greece's financial problems are attributed solely to domestic factors – most notably corruption, clientelism (cf. Afonso et al. Reference Afonso, Zartaloudis and Papadopoulos2015) and the incompetence of the country's political elites which creates problems for the Eurozone and should be overcome by pushing Greece out.

The value –1 denominates support for ‘hard conditionality’ in exchange of financial support. The quotes under this category are underpinned by the ‘moral hazard’ premise (cf. De Grauwe Reference Grauwe2013: 17–19) and the need for a ‘robust’ programme for Greece under the surveillance of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Unlike the previous category, the threat of Grexit is never explicitly mentioned, but it is implied only if Greece neglects its commitments to the creditors. The assessment of the reform efforts of the government in Athens is typically negative and Greece's troubles are rarely placed in the context of wider Eurozone dysfunctionalities.

The value 0 denominates neutrality and/or neglect whereby no explicit promises or threats against Greece are made. In the early stages of the crisis, quotes under this category typically fail to acknowledge that Greece (or indeed the Eurozone) was facing a crisis. Subsequently, neutral statements may defer opinion to the future – for example, after a forthcoming assessment of the programme or a relevant EU meeting. Statements of neutrality may also be connected with forthcoming elections in Greece, with European elites choosing not to interfere with the domestic party‐political competition (‘fence sitting’).

The value +1 denominates a preference for ‘soft conditionality’ towards Greece. A typical quote in this category acknowledges Greece's irreversible membership of the Eurozone, but at the same time presses the government in Athens to stick to its side of the bargain. Under this category, statements tend to emphasise the dangers of contagion from a possible Grexit and point to the deficiencies of the Eurozone's economic governance. On the other hand, the assessment of domestic reform is typically portrayed as ‘positive’ or ‘encouraging’.

The value +2 assigns strong support for Greece's Eurozone membership. The potential of Grexit is seen as ‘inconceivable’ and much of the blame for Greece's predicament is placed on the design of the bail‐out programme itself, rather than its domestic implementation. The underpinning principle of ‘solidarity’ takes precedence over conditionality or the ‘moral hazard’ thesis. Quotes falling under this category also mobilise historical or purely political arguments – not least the protection of Greece's democracy and halting the rise of the neo‐Nazi Golden Dawn party.

Although we are confident that there is sufficient distinctiveness between the different values in our scale, we acknowledge that coding of each individual quote is not fool‐proof. Sometimes, the quotes mobilise a mix of rewards and threats that cut across the typology we devised. Hence, the selection of a single value contains an inevitable element of discretion on behalf of the coder. The coding was conducted by two of the three co‐authors of the article who assigned a single value to each quote independently of each other. To ensure the coding was reliable we used Cohen's Kappa, which is a measure of inter‐rater agreement for ordinal variables, with reliability coefficients ranging from 0.92 to 0.88 (Bryman Reference Bryman2015: 276).Footnote 5

We are also constrained by the fact that Reuters typically publishes only a small extract from longer speeches or statements made by the officials in question. This editorial decision in itself ‘contaminates’ our sample and can skew the message intended by the official who delivered it. In this respect, the context, timing and the target audience of each individual statement also form important contextual information that help nuance any given discourse analysis. Yet, given the size of our sample, access to full transcripts (and other contextual information) was not possible. We argue that what has been lost in terms of narrative richness in our data collection strategy is counterbalanced by the comprehensive coverage offered by the Reuters database.

Employing a inductive approach we identify three critical moments during which Greece's future within the Eurozone came under the most intense media scrutiny,Footnote 6 reflected in significant peaks in the number of Reuters newswires during the corresponding week (see Figure 1): (a) the signing of the first Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the Greek government and its creditors on 3 May 2010 (a total of 465 wires between 3 and 9 May 2010); (b) the calling of a referendum on the second bail‐out by the Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou, on 31 October 2011 (a total of 267 wires between 31 October and 6 November 2011); and (c) the formation of a pro‐bail‐out ‘grand coalition’ government in Greece, following the general election of 17 June 2012 under Prime Minister Antonis Samaras (a total of 196 wires between 11 and 17 June 2012).

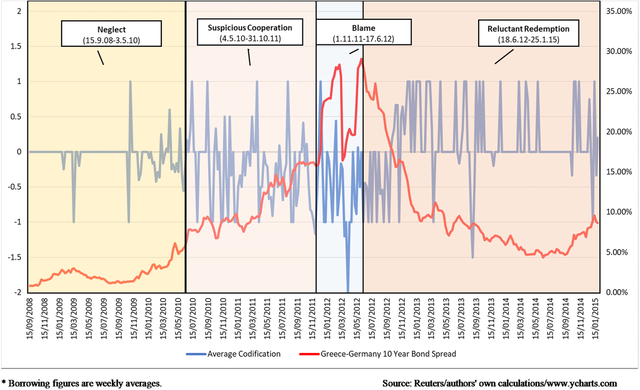

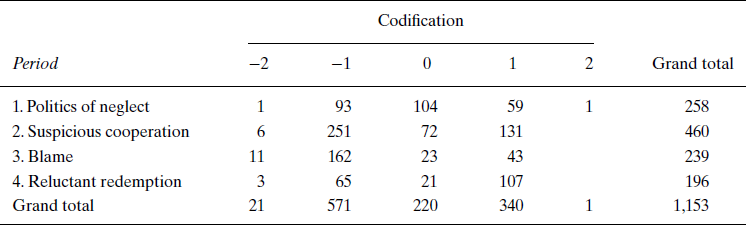

In line with Hay (Reference Hay2016) and Blyth (Reference Blyth2002), we argue that such pivotal events open up space for political competition, providing ‘windows of opportunity’ for European elites to (re‐)cast their communicative discourse towards Greece. Yet, these critical moments do not necessarily signify a major discursive departure by European elites. Hence, we hypothesise that discursive critical junctions materialise only when we can observe significant fluctuations in the average opinion scores by European elites (using our coding scale) during the intervening periods (see Figure 3). In order to account for discursive changes between periods we look into four sets of data: (1) the distribution of opinion scores of individual actors, clustered per institution, country or groups of countries (i.e., ‘core’ and ‘periphery’); (2) the share of individual countries or institutions in the total number of quotes; (3) the correlation coefficients between quotes by the main stakeholders, clustered around key cleavages (i.e., ‘core versus periphery’, ‘ideology’, ‘German leadership’, ‘Troika institutions’), tracing their relational evolution over time; and (4) the correlation coefficients between the average opinion scores on Greece and the evolution of the country's ten‐year bond yields. These are examined in more detail in the penultimate section of the article.

Figure 3. Average opinion scores on Greece and evolution of borrowing costs, per week. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

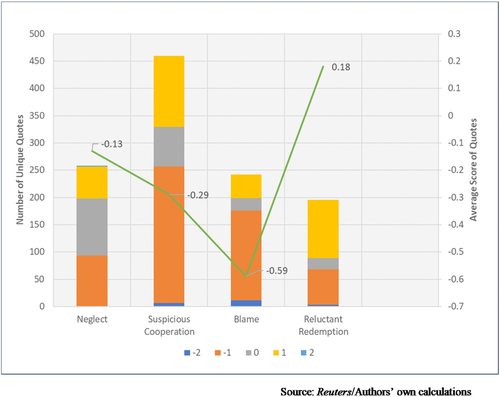

We acknowledge that in practice these discursive shifts can never be ‘cleanly’ separated as they form part of the constant process of (re‐)evaluating the complexities of the crisis (see Figure 4). Neither does the timing and content of policy change neatly map onto shifts in elite discourses. Yet, by examining the evolution of opinion scores of European elites before/after these critical moments, we maintain that it is possible to define discursively distinctive phases of the Greek crisis, thus allowing for a more nuanced analysis of the factors that shaped (anti‐)bail‐out strategies during the timeframe of our examination.

Figure 4. Distribution of opinion scores, per period. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Neglect: European discourses during the ‘pre‐history’ of the Greek crisis, September 2008–May 2010

This initial period of the Greek crisis stretches from the collapse of Lehman Brothers on 15 September 2008 to the signing of the first MoU between Greece and its creditors on 3 May 2010. During these 21 months the terms ‘Greece’, ‘financial’ and ‘crisis’ feature in 2,653 Reuters newswires, with 258 quotes on Greece made by the senior policy makers identified in our sample (see Figure 3). This is the period with the lowest density of quotes per week, with the vast majority of these concentrated after the electoral victory of George Papandreou in Greece in October 2009 (see Figure 2).

The relative neglect of Greece during this period should be understood in the context of a wider European discourse of denial about the intensity and reach of the gathering financial meltdown which was very much seen as ‘an American problem’ (Fuchs & Graaf Reference Fuchs and Graaf2010: 14). During that time, EU policy makers produced a cacophony of ideas over the nature of the unfolding crisis, its possible remedy and the best‐equipped institution to administer it. Voices urging the EU to adopt an American‐style fiscal stimulus package faced outright rejection by the German administration, forcing senior EU officials, including Jean‐Claude Juncker and Joaquin Almunia to urge that ‘fiscal policy should be maintained on a sustainable course’ and that the Eurozone did not need a ‘revival package’ (Reuters, 3 November 2008).

In the meantime, the growing concerns about Greece's deteriorating economic situation were brushed away by the centre right government in Athens as ‘malicious rumours’.Footnote 7 A similar complacency was also evident during the early days of the socialist government under George Papandreou, following PASOK's landslide victory in the November 2009 election on the promise of fiscal expansion (cf. Zartaloudis Reference Zartaloudis, Panizza and Phillip2013). The Pandora's Box was opened in the October 2009 ECOFIN Council when the Greek Finance Minister revealed that the country's deficit was around 12.5 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP),Footnote 8 rather than 6 per cent as previously reported (Reuters, 20 October 2009). Although the announcement threw the financial markets into turmoil and produced a media frenzy (see Figure 1), EU officials remained entrenched in their ‘no‐bail‐out’ discourse. In January 2010, Papandreou and senior EU officials dismissed claims that a bail‐out package was secretly being negotiated (Reuters, 29 January 2010). According to European Central Bank (ECB) President Trichet, ‘each country has its own problems. It [the Greek budgetary crisis] is a problem that has to be solved at home. It is your own responsibility’ (Elliott Reference Elliott2010).

In truth, however, the announcement of the revised budgetary figures for Greece and the country's effective cutting off from the financial markets in early 2010 made the elaboration of an EU‐sponsored rescue plan inevitable. In the months that followed, European leaders tread a very fine line: on the one hand, reassuring the markets that the Eurozone was ready ‘to take determined and coordinated action, if needed’ while at the same time maintaining that the bailing out of Greece was not on the cards (European Council 2010). This line was also reinforced by ECB President Trichet, who, in late March 2010, sought to reassure by saying that: ‘I am confident that the mechanism decided today [the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF)] will normally not need to be activated and that Greece will progressively regain the confidence of the market’ (Reuters, 25 March 2010). Although preparations for the rescue of Greece were gathering pace in the background, the discursive taboo of ‘no‐bail‐out’ was not yet broken.

Suspicious cooperation: The discourse of the first Greek bail‐out, May 2010–October 2011

During the period 4 May 2010–31 October 2011, media interest in the Greek crisis skyrocketed, with elite discourses demonstrating significant volatility. This is reflective of the early optimism that the Papandreou government would be able to deliver on ambitious targets for deficit reduction, before shifting towards negativity as the progress of domestic reform began to lose momentum (see Figure 4). Over the same period, the number of Reuters newswires matching our search criteria increased (yearly adjusted) threefold to 7,204 and the number of quotes in our sample reached 460 (see Figures 1 and 3). This is the second highest density of quotes/per week in our entire dataset (see Figure 2).

In communicative terms, the departure from the previous EU stance of ‘no bail‐out’ was seemingly justified on the premise of Greek exceptionalism. In this context, the ‘rescue’ of Greece was not seen as symptomatic of structural weakness in the design of the Eurozone, but rather the outcome of the country's chronic economic mismanagement by a corrupt and untrustworthy political elite. A big part of the Greek exceptionalist discourse was centred on the concealment of Greece's economic implosion under the ‘Greek statistics’ fiasco which resulted in a catastrophic collapse of credibility. Economically, Greece's exceptionalism manifested in its ‘triple deficit’ problem: the largest debt‐to‐GDP ratio in the Eurozone, compounded by huge budget and current account deficits.

In this context the ECB President argued that ‘the euro itself, is by the way, a very solid currency. It's clear that Greece is a very special case and the reason we are here’ (Reuters, 4 May 2010). Statements to that effect were made, among others, by the IMF Director, Dominique Strauss‐Kahn, who suggested that ‘this crisis is actually a Greek crisis’ (Reuters, 17 May 2010). The position of the newly elected Papandreou government within this narrative was precarious as Greece's creditors needed Papandreou on board, yet there was suspicion over his ability to deliver (Reuters, 3 May 2010; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2013).

This suspicion went part and parcel with the wider discussion on the ‘moral hazard’ associated with the EU's bail‐out policy. Narratives on conditionality and rule observance became dominant in this respect and were echoed by key policy makers managing the Eurozone crisis. For instance, German Chancellor Angela Merkel reassured that the Greek programme had ‘strict economic and legal preconditions’ attached to it (Reuters, 14 May 2010). Her Finance Minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, went a step further: ‘[W]e need a broader sanctions mechanism to get the moral hazard problem in the euro zone under control’ (Reuters, 23 September 2010). Calls for strict bail‐out conditionality and external verification of compliance (in the form of IMF involvement under the so‐called ‘Troika’ of European Commission, ECB and IMF) also reflected a significant erosion of trust in the ability of the Commission to oversee Greece's adjustment.

By mid‐2011, as the political stock of the Papandreou government evaporated and the crisis began to spread to other peripheral economies in the Eurozone, the sustainability of the Greek programme came under increasing scrutiny. So, too, did the entire stability of the Eurozone. Following months of acrimonious negotiations between Greece and its Eurozone partners, a deal was reached, in July 2011, for a second bail‐out worth €100 billion including the first restructuring of privately held sovereign debt of a Eurozone member (Reuters, 21 July 2011). Yet, despite some initial optimism, the July agreement was soon discredited for its complexity and for doing little to reassure the markets over the adequacy of the Eurozone's ‘firewall’ and the long‐term sustainability of the Greek debt.

Divided over what to do next, European leaders produced a cacophony of responses which further aggravated market fears over the euro. In August 2011, European Commission President Barroso criticised ‘the undisciplined communication of EU leaders’, while French President Nicolas Sarkozy pleaded with his opposite numbers ‘to move on from these national quarrels and get back to the sense of our common destiny. … It's everyone's duty to do everything needed to safeguard the stability of the euro’ (Reuters, 16 June 2011). In the run‐up to a new EU summit in October 2011 to review the situation in the Eurozone, European discourses on Greece grew increasingly hostile with some (including the Dutch Prime Minister and the leader of Germany's right‐wing junior governing coalition partner, the Free Democratic Party) openly calling for Greece's ejection from the Eurozone (Reuters, 7 September 2011). The German Finance Minister fell short of publicly endorsing these calls, but remained coy: ‘It would be a bad government if it didn't try to prepare for things you can't even imagine’ (Reuters, 12 September 2011). President Sarkozy called Greece's Eurozone membership ‘a mistake’ (Reuters, 27 October 2011). The discursive taboo of Grexit was now beginning to erode.

Blame: Enter ‘Grexit’, November 2011–June 2012

As Eurozone leaders struggled to contain the crisis, the pressure on the Papandreou government in Greece intensified. In a desperate attempt to regain legitimacy, Papandreou called for a referendum on the terms of the second Greek bail‐out (Reuters, 31 October 2011). The unexpected announcement caused mayhem in the financial markets and threatened to derail the entire package of EU measures agreed just weeks before. Outraged by what they regarded as Papandreou's unreliability and recklessness, EU leaders, spearheaded by President Sarkozy and Chancellor Merkel, brought Grexit to the forefront of their discourses in an attempt to force the Greek government to retract the referendum announcement (Reuters, 2 November 2011; 3 November 2011). Papandreou had overplayed his hand and his time was now up. By the end of that week his resignation paved the way for the appointment of an interim coalition government under the former ECB Vice‐President, Loucas Papademos.

The political drama in Athens attracted intense media interest. For the period 1 November 2011–17 June 2012, Reuters published a total of 2,725 newswires matching our search criteria, with 239 unique quotes on Greece by European elites (the largest concentration of quotes per week for the entire period of the study) (see Figures 1 and 2). The arrival of Papademos at the helm might have assured European leaders that the country now had a safe pair of hands who could see through the complexities of Greece's debt restructuring programme, which remained high on the media agenda during the first months of 2012, but widespread mistrust against the political elites in Athens remained (see Figure 4). Against this background, European discourses on Greece remained hostile throughout Papademos’ term. For instance, both the Dutch and Finnish Prime Ministers openly discussed the prospects of Greece's exit from the Eurozone (Reuters, 7 February 2012; 15 May 2012) and Schäuble described Greece as a ‘bottomless pit’ (Reuters, 21 February 2012).

In the run‐up to the Greek parliamentary election of May 2012, European policy makers put significant pressure on all political parties to commit to the continuation of the austerity measures – a position strongly advocated by many commentators in the German press (for a review, see Allen Reference Allen2012). Widespread public hostility against the bail‐out programme, however, strengthened anti‐systemic forces in Greece on both the left and the right of the political spectrum (cf. Zartaloudis Reference Zartaloudis, Panizza and Phillip2013). The inconclusive result of the May election and the subsequent impasse over the formation of a coalition government further aggravated European policy makers. In this context, the fresh electoral contest of June 2012 was widely articulated as an ‘in‐or‐out’ referendum on Greece's membership of the Eurozone – a message that also echoed by the newly elected French President after his first meeting with British Prime Minister David Cameron (Reuters, 18 May 2012).

In the aftermath of the election, a ‘grand’ coalition between ND and PASOK was formed, supporting Greece's continuing engagement with its creditors. The new Greek Prime Minister, Antonis Samaras, had travelled a long way since his days as a fierce critic of the bail‐out programme, to reinvent himself as the ‘guarantor’ of Greece's ‘European orientation’ (Samaras Reference Samaras2012). To their European counterparts, Samaras and Evangelos Venizelos (leader of PASOK and Deputy Prime Minister), epitomised much of what had gone wrong with Greece in the past. Yet, their unlikely coalition partnership offered the prospect of a stable government and a faint hope that the terms of the second bail‐out would be implemented. Redemption appeared to be on the cards, but Athens was called to do more.

Nowhere else to go: The politics of reluctant redemption, June 2012–January 2015

The arrival of the pro‐bail‐out government might have ended a summer of high political drama in Athens, but fears over financial ‘contagion’ across the Eurozone intensified as the economic health of Italy and Spain came under greater scrutiny (Reuters, 30 November 2011). This uncertainty was compounded by the election, in April 2012, of French Socialist President Hollande amid concerns of rising discord within the Franco‐German axis (Reuters, 7 May 2012). Against this background, European stakes in Greece's reform commitment increased further. Indeed, the European discourses during the first few months of Samaras’ premiership remained rather negative (see Figure 4). The German Chancellor's caution over the new government was reflective of this mood: ‘[W]e will not make premature judgments but will await reliable evidence’ (Reuters, 24 August 2012).

The turning point seems to have come in November 2012, when the coalition government in Athens pushed another major round of budgetary cuts through parliament (cf. Zartaloudis Reference Zartaloudis2014). Greece's creditors reciprocated by agreeing the release of €43 billion in assistance, alongside other measures for lowering the country's debt burden and a commitment to providing further debt relief in the future. In the aftermath of the deal, both President Hollande and the European Council President, Herman Van Rompuy, appeared confident that the worst of the Eurozone crisis was now over. Barroso was also in a buoyant mood: ‘[O]nce again we have shown that we have the capacity to act and we are able to do whatever is necessary for a firm and sustained irreversibility of the euro as a currency of the European Union’ (European Commission 2012).

In the months that followed, European discourses on Grexit began to mellow (see Figure 4) and media interest in Greece subsided considerably, particularly as Italy and Spain came to dominate the EU agenda. Between 18 June 2012 and 25 January 2015, we uncovered a total of 2,772 articles on the Greek crisis – a quarter of that of the preceding period, yearly adjusted (see Figure 1). The 196 unique quotes on Greece we identified during these 30 months also represent the least ‘vocal’ period in our entire dataset. The improvement of Greece's international profile was further boosted by the release, in early 2014, of economic figures showing the first tentative signs that the worst of the Greek crisis was coming to an end (European Commission 2014). The government in Athens was quick to claim that the country was now becoming the Eurozone's ‘success story’ (Reuters, 1 April 2014).

Such a bold claim was directed to both a domestic and an international audience. Domestically, Prime Minister Samaras hoped to halt the rising popularity of anti‐austerity SYRIZA, which by now was demanding the resignation of the government and the calling of fresh elections (Reuters, 3 November 2014). Internationally, the government sought to strike a better deal with Greece's creditors in the context of the fifth (and final) assessment of the country's bail‐out programme in the summer of 2014. A few months earlier, the German Chancellor had hinted at Greece's partial rehabilitation by paying a highly symbolic visit to Athens (the first time since the outbreak of the crisis), during which she praised the Greek government ‘for fulfilling its pledges’ (Reuters, 11 April 2014).

Merkel's visit to Athens might have boosted Samaras’ profile, but, by summer, the Greek Prime Minister's pleas for the relaxation of austerity met with stiff opposition by the German government. The language this time was diplomatic, but the message uncompromising: ‘Greece must resolutely continue to implement the agreed reforms. In its own interests. Being reliable creates confidence – also on the markets,’ argued the German Finance Minister (Reuters, 19 October 2014). As Greece's efforts to return to the financial markets in the summer of 2014 met with only limited success (Reuters, 17 October 2014), the fate of the coalition government in Athens was sealed. The inevitability of SYRIZA's victory in the forthcoming election weakened Samaras’ currency in Europe and halted his reformist momentum at home. His European ‘redemption’ was never to fully materialise. Greece's creditors had already started to prepare for ‘the day after’: the arrival of Alexis Tsipras at the helm.

Explaining discursive change during the Greek crisis

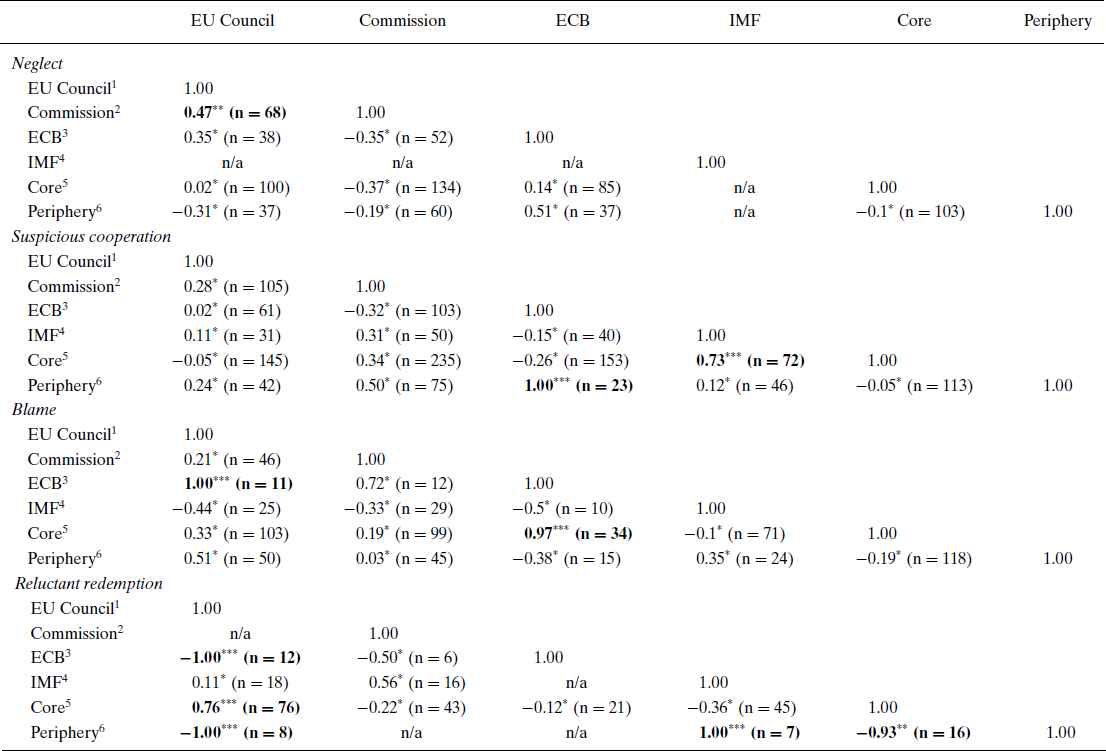

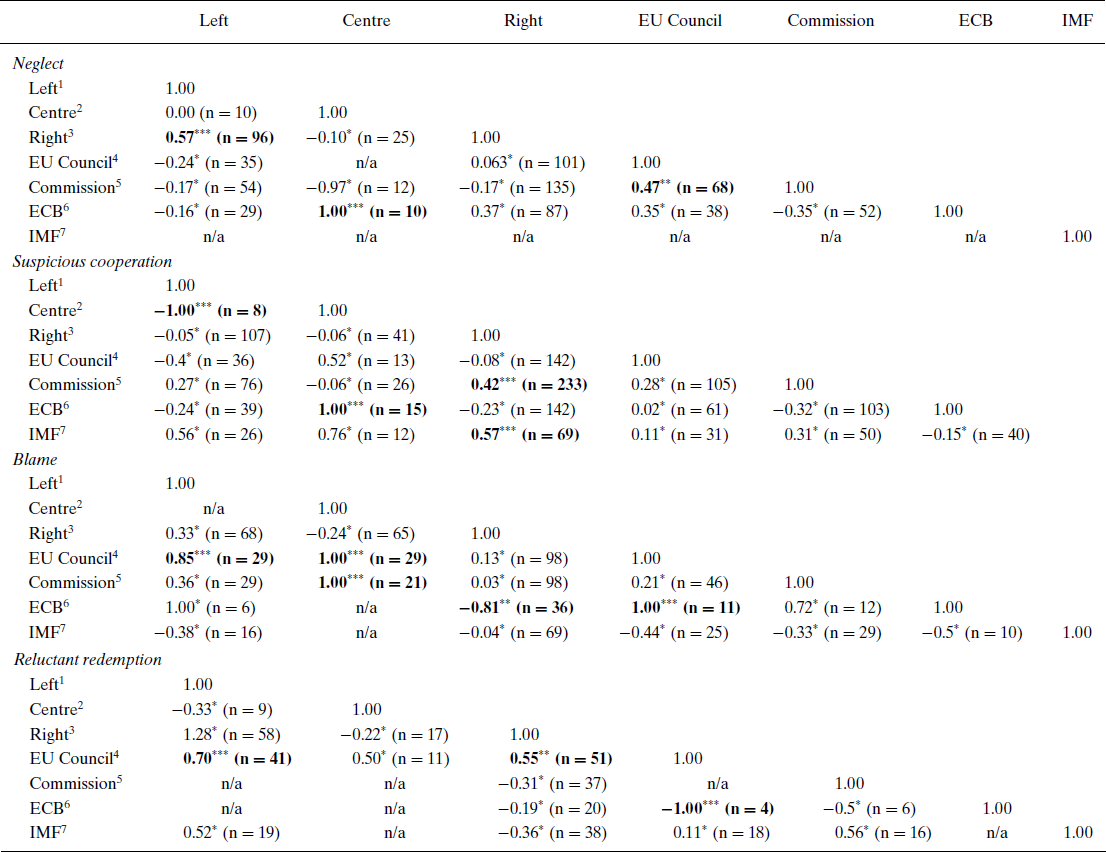

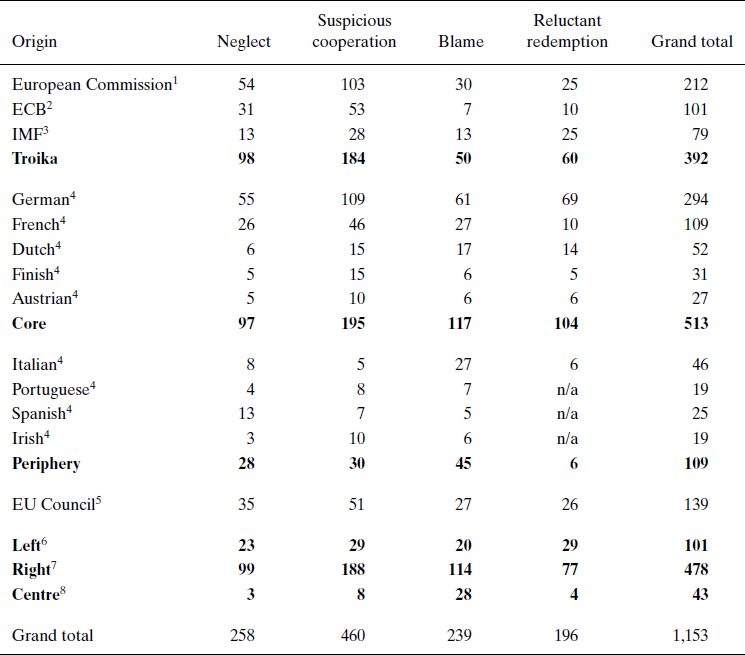

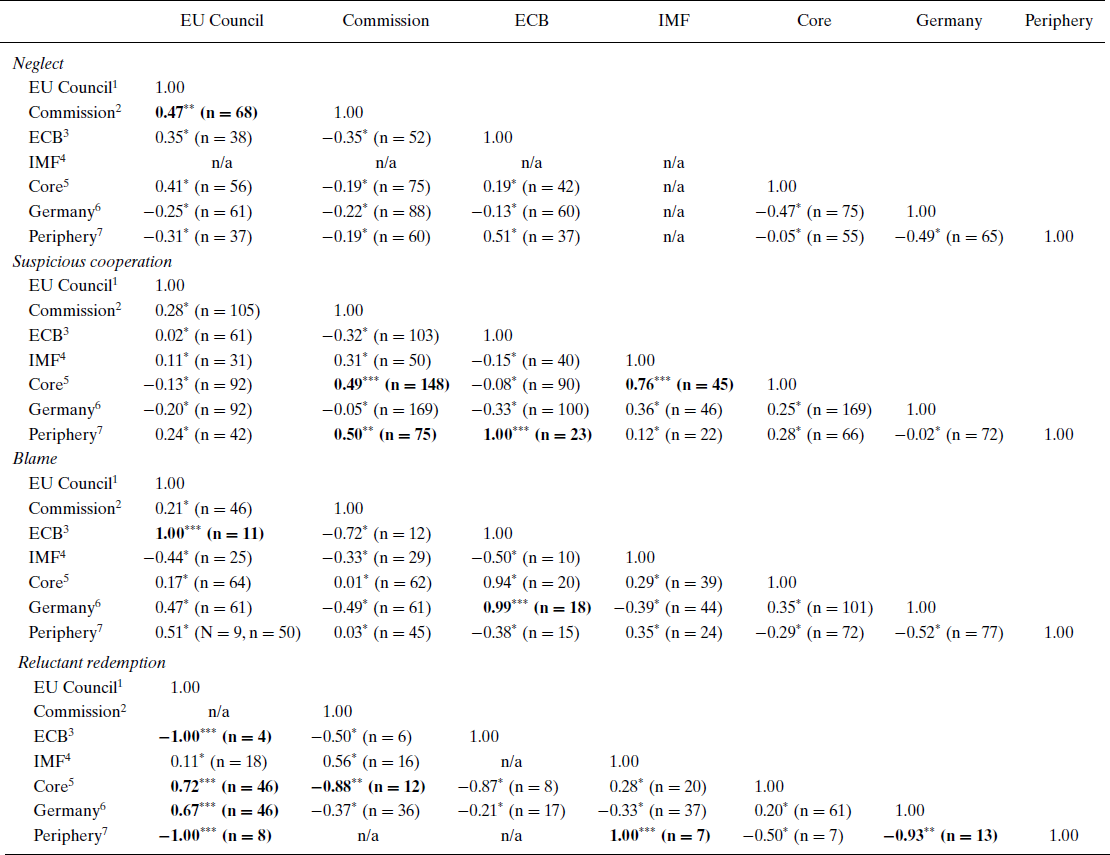

Viewed in its entirety, across the four periods we have identified, our dataset depicts a rather confusing pattern of elite discourses. First, we observe a lack of stable discursive coalitions that are sustained throughout the period of our investigation (cacophony). For example, there is no discernible ideological (along the left‐right axis) or geographical (i.e., ‘core’ versus ‘periphery’) cleavage shaping opinions on Greece, whereas significant discursive discord is also evident among the three institutions that make up the Troika (see Tables 2 and 3). These findings deviate from existing scholarship, which has pointed to ideological (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2014; Kaiser & Kleinen‐von Königslöw Reference Kaiser and Kleinen‐von Königslöw2016, Reference Kaiser and Kleinen‐von Königslöw2017) or geographical (Wodak & Angouri Reference Wodak and Angouri2014; Kutter Reference Kutter2014; Ntampoudi Reference Ntampoudi2014) factors shaping the discourse of the Eurozone crisis.

Table 2. Core/Periphery/Troika Correlation Matrix, weekly aggregated

Notes: 1Eurogroup and European Council Presidents, combined. 2Commission President and Commissioner for Financial Affairs, combined. 3ECB President. 4IMF Director. 5Heads of Government and Finance Ministers of France, Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and Finland, combined. 6Heads of Government and Finance Ministers of Italy, Spain, Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus, combined. *p ˃ 0.10; **p ≤ 0.10; ***p ≤ 0.05. n = number of quotes. n/a = cannot be computed because at least one of the variables are constant. Bold entries indicate statistical significance.

Table 3. Ideology Correlation Matrix, weekly aggregated

Notes: 1Heads of Government and Finance Ministers from left and centre left party families, combined. 2Heads of Government and Finance Ministers from centre and liberal party families, combined. 3Heads of Government and Finance Ministers from right and centre right party families, combined. 4Eurogroup and European Council Presidents, combined. 5Commission President and Commissioner for Financial Affairs, combined. 6ECB President. 7IMF Director. *p ˃ 0.10; **p ≤ 0.10; ***p ≤ 0.05. n = number of quotes. n/a = cannot be computed because at least one of the variables is constant. Bold entries indicate statistical significance.

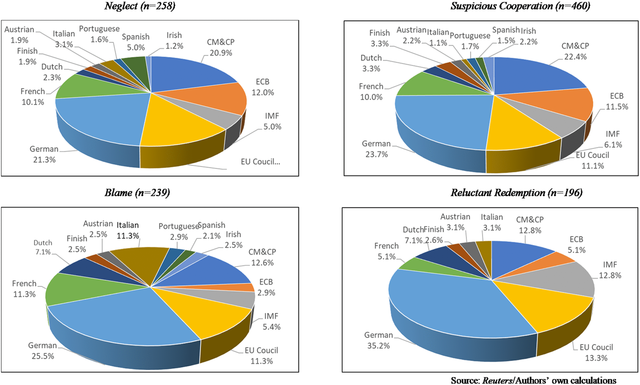

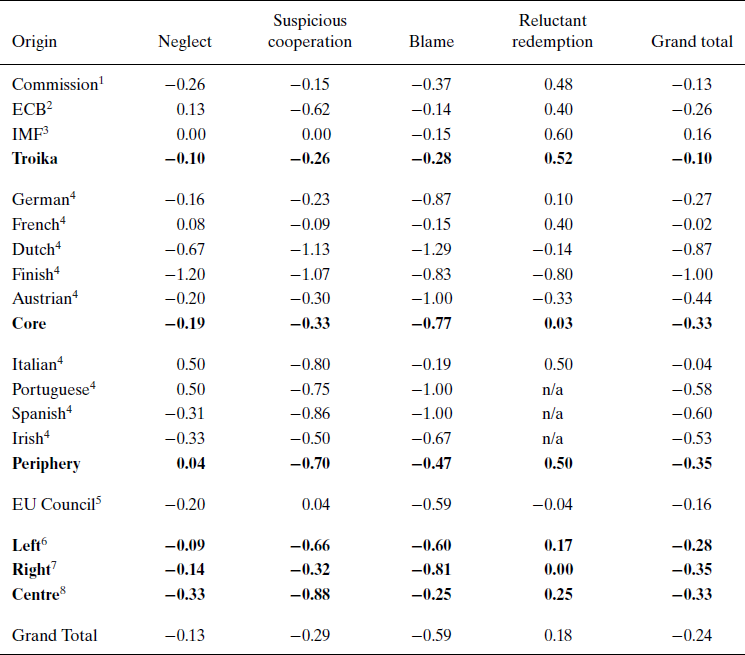

A second observation relates to the question of prominence, understood here as the share of certain individuals/countries/institutions in the overall volume of available quotes. The visibility of German leaders in this respect is staggering, as the German Chancellor and Finance Minister accounted (combined) for over a quarter of the total number of quotes in our dataset (see Figure 5). This finding is in line with the claims made by Picard (Reference Picard2015: 14, 83–102). More broadly, the narrative of the Greek crisis appears to have been overwhelmingly shaped by the centre right of ‘core’ EU member states, with the number of quotes originating from the centre left or the EU's ‘periphery’ lagging far behind in all four periods (see Table 4).

Figure 5. Quotes by country/institution of origin, per period. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 4. Number of opinion scores, per stakeholder, per period

Notes: 1Commission President and Commissioner for Financial Affairs, combined. 2ECB President. 3IMF Director. 4Head of Government and Finance Minister, combined. 5Eurogroup and European Council Presidents, combined. 6Heads of Government and Finance Ministers from left and centre left party families, combined. 7Heads of Government and Finance Ministers from right and centre right party families, combined. 8Heads of Government and Finance Ministers from centre and liberal party families, combined. Bold entries indicate aggregates.

Third, we observe an absence of discursive leadership on the Greek crisis. For example, for all of its prominence in terms of its share of the total number of quotes, there is no statistical evidence to suggest a consistent correlation between Germany's position and those of other major stakeholders of the crisis (see Table 5). A similarly weak discursive leadership can also be observed in the case of the Troika institutions (see Tables 2 and 3). Here, too, our findings do not corroborate a Europeanisation effect in the discourse of the crisis similar to that discussed by Kaiser and Kleinen‐von Königslöw (Reference Kaiser and Kleinen‐von Königslöw2016, Reference Kaiser and Kleinen‐von Königslöw2017).

Table 5. German Leadership Correlation Matrix, weekly aggregated

Notes: 1Eurogroup and European Council Presidents, combined. 2Commission President and Commissioner for Financial Affairs, combined. 3ECB President. 4IMF Director. 5Heads of Government and Finance Ministers of France, the Netherlands, Austria and Finland, combined; Germany excluded. 6Chancellor and Finance Minister, combined. 7Heads of Government and Finance Ministers of Italy, Spain, Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus, combined. *p ˃ 0.10; **p ≤ 0.10; ***p ≤ 0.05. n = number of quotes. n/a = cannot be computed because at least one of the variables is constant. Bold entries indicate statistical significance.

Fourth, the Pearson correlation coefficient between opinion scores on Greece (weekly aggregated) and the spread of the ten‐year Greek bond yield against the German Bund (weekly aggregated) appears rather inconclusive: Neglect: 0.01, p = 0.96; Suspicious cooperation: –0.7, p = 0.35; Blame: 0.3, p = 0.01; and Reluctant redemption: –0.30, p = 0.004 (see also Figure 4).Footnote 9 This highlights the need for further research in disaggregating possible correlations along national or institutional lines, but also in accounting for ‘external’ developments (e.g., the spreading of the crisis to other Eurozone members, announcement of key policy initiatives), before firmer conclusions can be reached.

In explaining the shifts from one discursive period to another, a number of observations can be made. During the period of neglect, the overall opinion score of –0.13 is primarily explained by the large share of ‘neutral’ (denominated by ‘0’ in our coding) opinions on Greece which accounted for 40 per cent of available quotes (see Figure 3). Over the same period, the ‘core’, although dominant in terms of its combined share of quotes (see Figure 5), does not register a statistically significant correlation pattern between Germany and the rest of its members (see Table 5). By contrast, the rhetorical postures of the centre left and the centre right are clearly aligned (see Table 3). The rhetoric of the ECB during this time is also revealing. During the early stages of the crisis the ECB remained ominously silent on Greece, with only five negative opinions out of a total of 31 during the entire period of neglect (see Table 4). This reflected the ECB's caution not to talk the euro down, but also Trichet's own scepticism over the bail‐out itself and the emerging Troika‐inspired solution for Greece.

During the period of suspicious cooperation the pattern of discursive coalitions changes, leading to the worsening of Greece's image among its international creditors (see Figure 4). The share of ‘neutral’ opinions decreases substantially down to 15.7 per cent, with a corresponding increase in the share of negative –1 and –2 scores up to 54.6 per cent of the total (see Figure 3). Also significant is the decline in the share of quotes from the Eurozone's ‘periphery’ from 11 to 6 per cent, which nevertheless appears to have been more negatively disposed towards Greece than ‘core’ Eurozone members (see Figure 5 and Table 6). In the context of financial ‘contagion’ and the spreading of the crisis to other parts of the Eurozone ‘periphery’, this reflected the growing concern among many southern European leaders not to associate their own political fortunes with the fate of Greece. This may also explain the strong correlation of opinion scores between the Eurozone's ‘periphery’ and those of the ECB (Table 2). The discursive posture of Germany during the same period also hardens (see Table 6) and there is a statistically significant rhetorical alignment between ‘core’ Eurozone members and the IMF (Table 2). A similar alignment is also observable in the positions of centre right politicians with those of the European Commission and the IMF (Table 3).

Table 6. Average opinion scores, per stakeholder, per period

Notes: 1Commission President and Commissioner for Financial Affairs, combined. 2ECB President. 3IMF Director. 4Head of Government and Finance Minister, combined. 5Eurogroup and European Council Presidents, combined. 6Heads of Government and Finance Ministers from left and centre left party families, combined. 7Heads of Government and Finance Ministers from right and centre right party families, combined. 8Heads of Government and Finance Ministers from centre and liberal party families, combined. n/a = not available. Bold entries indicate aggregates.

The share of negative opinions on Greece increases further to over 72 per cent during the period of blame, leading to a sharp decline of the overall opinion scores to –0.59 (the lowest in the timeframe of our examination) (see Figure 3). Although the share of ‘Grexit opinions’ (–2) remained rather small at 4.6 per cent of the total, their number nearly doubled in absolute terms (see Table 7). The arrival of Mario Monti in Italy and Mario Draghi at the ECB in November 2011 appears to have an important effect. Italy's share of quotes during this period rises to 11.3 per cent of the total (up from 1.1 per cent), whereas statistically significant (positive) correlations can be observed in the opinions of centrist politicians with those expressed by the Council of the EU and the European Commission, respectively (see Figure 5 and Table 3). By contrast, the frequency of interventions by the ECB President decreases substantially, although his opinion scores on Greece correlate strongly with those of the Eurozone's ‘core’ and centre right politicians (see Tables 2, 3 and 4).

Table 7. Distribution of opinion scores, per period

Sources: Reuters; authors’ own calculation.

During the period of reluctant redemption the significant improvement of Greece's international profile (aggregate opinion score = 0.18) is driven primarily by a substantial increase of positive opinion scores which, for the first time, account for more than 50 per cent of the total (see Figure 3). Somewhat surprising, the arrival of Francois Hollande in the French Presidency in May 2012 leads to a greater discursive alignment within the Franco‐German axis, evidenced by the distribution of their respective opinion scores (see Table 6). Similarly, there is a statistically significant (positive) correlation of opinion scores between the Council of the EU and those of the centre left and centre right, respectively (see Table 3). Over the same period the share of quotes originating from the Eurozone's ‘periphery’ decreases substantially, with only Italy barely registering an impact (see Figure 5). The discursive posture of the ‘periphery’, however, appears to be diverging from both the Eurozone's ‘core’ and the Council of the EU (converging, instead, with that of the IMF), although these trends should be treated with caution given the relatively low number of relevant observations (see Table 2).

Conclusion

This article scrutinised the evolving discourse(s) of senior EU and IMF figures on the Greek crisis. By reference to the conceptual literature on DI and HI, we have argued that the management of Greece's financial implosion produced four discursive frames (‘neglect’, ‘suspicious cooperation’, ‘blame’ and ‘reluctant redemption’), reflecting the unfolding economic and political drama in Athens, Brussels, Frankfurt and Washington. Viewed in its entirety, we argued that the period 2008–2015 is characterised by discursive cacophony (and volatility), underpinned by the lack of stable discursive coalitions and/or leadership. The connection between elite discourse and market pressures on Greece's borrowing costs also appears inconclusive.

There are several ways in which the article contributes to our understanding of the Greek and Eurozone crisis more broadly. Empirically, it is the first study to have examined systematically an extensive dataset (1,153 unique quotes drawn from a body of 15,354 newswires from Reuters) on the communicative discourse of 63 senior officials with high stakes in the Greek crisis. We have mapped out the evolution of this discourse by reference to the changing pattern of discursive coalitions over time. This was evidenced by the aggregation of our data along national and institutional lines, the identification of key cleavages affecting the narrative of the crisis as well as an analysis of the correlation coefficients of quotes originating from key (groups of) stakeholders. The relevance of this data stretches beyond the narrow confines of the Greek case, offering an important resource for scholars working on the management of the wider Eurozone crisis.

Conceptually, the article moves the literature on DI forward in two important respects. By incorporating insights from HI (particularly the concepts of ‘critical moments’ and ‘critical junctures’) into our analysis we have sought to explore more fully the dynamic nature and evolving character of discourse in public policy. Such cross‐fertilisation between different strands of the institutionalist tradition is valuable in mitigating the critique against DI as being rather static, but also in capturing the discursive volatility under conditions of crisis management.

In addition, we have articulated a distinct way of identifying moments of discursive change in longitudinal studies of public policy. Working inductively, we identified three peaks in the media coverage of the Greek crisis and we hypothesised whether these windows of opportunity (or critical moments) for the (re‐)casting of elite discourse on the crisis materialised into discursive critical junctures. Our results confirm that in the aftermath of all three critical moments the content of elite discourses on Greece changed significantly, thus producing distinct discursive frames in the management of the Greek crisis. Such an inductive approach to the study of the interface between discourse and policy over time has broader relevance in helping scholars to operationalise better some of the key insights of DI and provide a more fertile ground for robust empirical testing through the use of large datasets.

This study, however, has certain limitations which open up stimulating agendas for future research. First, our focus on quotes by officials at the highest echelons of power provides an important, but by no means exhaustive, account of the discourse that conditioned the handling of the Greek crisis. Public statements by Prime Ministers, Finance Ministers and central bankers tend to be heavily scripted and rather guarded – something that may explain the relative scarcity of quotes at the two extremes of our ordinal coding scale. Yet, the discourse on Greece (particularly with regards to explicit threats of Grexit) was also affected by statements made by less senior government ministers, parliamentary allies or opposition leaders and/or senior officials at national central banks whose opinions often featured heavily in the media. These were not captured by our analysis.

Second, our examination of the Reuters database has produced a sizable, but not exhaustive, dataset of quotes originating from the 63 identified stakeholders of the Greek crisis. Covering national (or other international) media outlets would have substantially increased the number of our observations, thus strengthening the statistical power of our analysis. Yet, such a research strategy would have to be mindful of issues of national/editorial biases, duplication of entries and translation nuances which have the potential to ‘contaminate’ the sample.

Third, although the article has sought to place the changing contours of elite discourse on the Greek crisis in the context of a constantly evolving situation on the ground, we did not explicitly interrogate the causal mechanisms between discourse and policy change. Such an undertaking would involve a closer examination of the coordinative discourse of key stakeholders as well as a closer look at the nature and the pursuit of their respective strategic interests. Similarly, more research is required in nuancing the connection between markets and elite rhetoric in the context of a multidimensional crisis conditioned by (the fear of) contagion. Shedding more light onto these fields is critical for advancing our understanding of the handling of the Eurozone crisis and the Greek case within it.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the support of Dimitris Kapros and Giannis Skianis for the statistical analysis in the article. We are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers and EJPR editors for their constructive comments.