In the face of adaptation failures, can national governments retain public trust through strong performance in the shorter term, such as in natural disaster response? This article tests Carlin et al.’s (Reference Carlin, Love and Zechmeister2014) notion that extreme weather events (EWEs) like earthquakes create “Hobbesian-like moments in which social bonds give way to mistrust and insecurity,” specifically by assessing how a government with low levels of public trust can improve their image with citizens through their disaster-response performance. Even more specifically, we seek to understand whether different types of natural disasters (floods and droughts) generate different levels of satisfaction with governments, especially where citizen trust in government is low to begin with. To answer these questions, we conducted a 2023 national survey in Guatemala, a nation meeting three important conditions for this study: 1) it is the “lowest trust” nation in Latin America (see Latinobarómetro 2023) and one of the lowest in the world, 2) one of the most susceptible to EWEs, and 3) one which suffers regularly and simultaneously from flooding in the Caribbean and especially the Pacific coasts, and drought in the central mountain foothills, which form part of Central America’s “Dry Corridor.”

Throughout the early decades of the debate over climate change, “adaptation” was largely synonymous with disaster response. This reactive conceptualization was reflected in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s foundational structure—one of the three working groups in the first IPCC report (Working Group III) was tasked with conceiving response strategies in 1992 (Tegart and Sheldon Reference Tegart and Sheldon1992). Later IPCC definitions reinforced this reactive framing, defining adaptation as strategies “in response to actual or expected climatic stimuli or their effects” (Parry et al. Reference Parry, Canziani, Palutikof, van der Linden and Hanson2007, 9).

This disaster-response framework—encompassing strategies such as emergency shelter, displacement services, and disaster management—persisted well into the period after initial United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) negotiations, when adaptation policy remained fundamentally oriented toward emergency relief. This emphasis may possess a political logic as research shows that voters consistently reward visible, immediate government action during crises. For example, as Carlin et al.’s (Reference Carlin, Love and Zechmeister2014) analysis of Chile’s earthquake response reveals, natural disasters quickly become “deeply and inherently political occasions” where the state’s capacity to protect citizens and respond to their needs becomes crucial for maintaining social cohesion and trust. When states fail to respond adequately, disasters can generate “Hobbesian-like moments in which social bonds give way to mistrust and insecurity,” making immediate, visible government intervention not just politically advantageous but essential for social stability (Carlin et al. Reference Carlin, Love and Zechmeister2014).

Indeed, greater emphasis has been placed on the need for government trust in the aftermath of extreme weather events (EWEs) as a primary way to minimize lasting damage and maximize national resilience in climate-vulnerable nations, most of which are in the Global South. Recent years have brought a reorientation in thinking, as, starting in 2007, the IPCC explicitly started to define adaptation in terms of long-term planning and the implementation of policies explicitly centered on increasing climate resilience. In 2007, the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report defined adaptation as “adjustment in natural or human systems in response to actual or expected climatic stimuli or their effects, which moderates harm or exploits beneficial opportunities” (Parry et al. Reference Parry, Canziani, Palutikof, van der Linden and Hanson2007, 9).

Still, international donors have been slow in opening the adaptation assistance spigots (Malik and Ford Reference Malik and Ford2024; Weiler, Klöck, and Dornan Reference Weiler, Klöck and Dornan2018), and it may be argued, as EWEs related to climate change grow more and more frequent (Germanwatch 2021), that disaster relief may continue to be the core of how most nations and international organizations view adaptation. Critics claimed two decades ago (Yamin, Rahman, and Huq Reference Yamin, Rahman and Huq2005) that fragmented institutions, weak mandates, and political incentives prioritized reactive relief over structural resilience. And critics today make similar arguments. The long-time horizons required for climate policies to yield measurable results, and their lack of electoral salience, has made climate policies and investments less attractive than short-term responses that visibly signal state capacity and prevent the social instability that accompanies perceived government failure during climate-related crises (Eisenstadt and Bao Reference Eisenstadt and Bao2024; Finnegan Reference Finnegan2022).

Since the Paris Agreement, officials have been stymied over “how national governments translate these global templates (the Nationally Determined Contributions they submit on behalf of their nations) for subnational policy action, a critical issue for adaptation studies because adaptation is supposed to be a primarily local effort” (Dolšak and Prakash Reference Dolšak and Prakash2018, 332). At a time when concern about the adequacy of international cooperation in climate change policy has been rising, authorities are turning to subnational actors to address climate change (Andonova, Hale, and Roger Reference Andonova, Hale and Roger2017). In relegating the study of adaptation to subnational case studies, the scholarly community has abdicated responsibility for finding common patterns with which to systematically incorporate climate adaptation into theories of comparative political development and comparative politics more broadly. More precise specification of adaptation failures is need, including, as we argue in this article, better specification of policy solutions according to the type of extreme weather event being mitigated.

Viewed as expensive, complex, and politically risky, long-term resilience policies can be unpopular even in affluent nations. Mees et al. (Reference Mees, Uittenbroek, Hegger and Driessen2019, 198) claim that national governments, even in advanced developed nations like the Netherlands, are not prepared to undertake a shift in roles “from a regulating and steering government towards a more collaborative and responsive government that enables and facilitates community initiatives.” If developed “climate-forcing” nations (Colgan et al. Reference Colgan, Green and Hale2021) are unable to make this shift smoothly, then how might under-resourced nations suffering the brunt of the climate adaptation burden—developing nations like Guatemala—make this transition? The conventional wisdom emerging on adaptation is that, while it is a local problem, “polycentrism,” where multiple public and private organizations at multiple scales jointly affect collective benefits and costs, may provide partial answers (Ostrom Reference Ostrom2014). Whatever the case, many pose the central problem of building resilience as one of local governments fitting policies to their unique circumstances. A wide range of policies at multiple scales (from the international to the most local and perhaps led by government but also involving NGOs and the private sector) are needed to help implement resilience policies that scale from the local to the national. Polycentric cooperation can be particularly hard to institutionalize when citizens are not aware of which government entities are responsible for addressing their needs, and when overall trust in the government, which must spearhead any coalition of polycentric entities to solve any problems, is particularly low.

In Latin America and elsewhere in the Global South, governments have faced contradictory incentives that ultimately reinforce short time horizons in resilience strategies. They can satisfy international donors by including references to long-term resilience in official planning documents (see Amini and Eisenstadt Reference Amini and Eisenstadt2025) but while delivering patronage through particularistic resilience efforts—such as emergency payments, shelters, and infrastructure repairs—often tied more closely to immediate political interests than to the long-term construction of resilience. And funds for disaster relief and adaptation have fallen short as the demand has increased. The UNFCCC acknowledged, finally, in late 2023, the necessity of “loss and damage” relief for developing nations, which “deep pocket” member nations—including the European Union and United States—had kept out of international negotiations for over a decade as they feared being held accountable for tsunamis and hurricanes in poor nations halfway around the world (Kolmaš Reference Kolmaš2024).

In the absence of international resources, how can nations better prepare to respond to EWEs as these grow more and more frequent? While this article focuses most directly on EWE relief, which has been difficult to undertake successfully in nations with low levels of public trust and prone to corruption and inefficiency, like Guatemala, we try to disaggregate disaster response and implications for adaptation policy. We argue that while policies governing short-term and reactive disaster relief (and long-term and proactive adaptation) are necessarily localized, patterned characteristics might be identifiable which could allow policymakers to better react to and plan for natural disasters. More specifically, we show, through our survey, that while floods—and government reactions to them—adversely impacted “already low” public trust in government, droughts did not.

Recent survey research has shown that vulnerable citizens sometimes do not readily differentiate between levels of government in the provision of resilience goods, including disaster relief, the construction of embankments and other infrastructure, and broader adaptation planning efforts such as introducing applied technology like weather-resistant crop seeds (Eisenstadt et al. Reference Eisenstadt, Haque, Toman and Wright2024). We build on that research by adding that the form that extreme weather takes—floods versus droughts—conditions citizen attitudes toward government responses, perhaps as much as the effectiveness of the government policy itself. We also build on an emerging line of inquiry, arguing, in relation to general environmental policies, that citizens may not react as strongly to “slow harms” (like drought) as they do to immediate, hard-hitting disasters like flooding (Herrera Reference Herrera2024; Nixon Reference Nixon2011). In fact, we argue that slow harms may create a double-bind as they are the ones most in need of long-term resilient responses.

In this article we demonstrate, using survey evidence, that among those directly suffering climate harms, the type of climate harm they experience significantly impacts their perceptions of government performance. Firsthand experience with flooding only marginally affects respondent views in the full national sample, but the effect was much stronger among those who received government disaster relief after their firsthand experiences with climate-related extreme weather events. Specifically, being a flood victim who received disaster assistance had a strong negative effect on respondent attitudes regarding government performance, whereas being a drought victim did not have a notable effect on respondent perceptions of government performance. In short, this article conditions the Carlin et al. (Reference Carlin, Love and Zechmeister2014) conclusion that EWEs might diminish social trust.

We find that in some climate events (mainly floods), victims who have received government relief tend to actually lower their trust in the government’s performance. The broader conclusion for theorizing climate adaptation is that we must better specify scope conditions for adaptation processes because different climate EWEs have different impacts on levels of citizen trust of government. Such trust is vital for the implementation of many policies, and how EWEs impact levels of trust merits extensive further consideration. After further showing that the scant social science literature on resilience (disaster relief and long-term adaptation planning) still focuses mainly on finding unique policies to solve idiosyncratic local problems, we argue that such claims against generalizability hinder efforts to strategize more broadly about how to build resilience.

Literature Review: A Lack of Systematic Resilience Studies and Resources

Practitioners and scholars are increasingly concerned about how the ongoing and inevitable impacts of climate change will exacerbate existing socio-political problems in vulnerable societies (Thomas and Warner Reference Thomas and Warner2019; Kehler & Jeff Birchall, Reference Kehler and Jeff Birchall2021). Lack of comprehensive adaptation measures in many vulnerable countries has forestalled international progress in international adaptation (Otto and Fabian Reference Otto and Fabian2024; Malik and Ford Reference Malik and Ford2024) and fostered widespread food and water scarcity along with mass displacements (Adger, De Campos, and Mortreux Reference Adger, Campos and Mortreux2018; Rasul and Sharma Reference Rasul and Sharma2016). Despite the vital importance of robust resilience policies and measures for climate-vulnerable and developing countries, only a few states have invested in building resilient institutions. Little social science work considers climate institutions across nations (Eskander and Fankhauser (Reference Eskander and Fankhauser2020) and Dubash (Reference Dubash2021) are exceptions), let alone whether and how these institutions help communities and nations cope.

Indeed, national and subnational governance under duress, such as in climate-induced natural disasters, is a core challenge in debates over how to build resilience. Politicians and analysts are challenged by being called on to assist the most climate-vulnerable countries, but are also aware that some of these countries, like Guatemala, are known for their weak state capacity, meaning that funds can be wasted on corruption and inefficient spending (Petherick Reference Petherick2012). These conditions could easily result in a sort of “maladaptationFootnote 1 trap,” where victim nations require great sums of capital and yet cannot deploy this capital to help their most vulnerable citizens build resilience. Indeed, often in Guatemala this “maladaptation” leads to migration, or at least serious consideration of migration (Maboudi et al. Reference Maboudi, Eisenstadt, Arce, Feoli and Antonio Giron Palacios2025), among flood and drought victims alike. However, we argue in this article that the role of government in building resilience is central. Indeed, the capacity of governments, at least in the delivery of flood relief, needs to be strengthened to protect vulnerable populations and improve citizen well-being. As we demonstrate, trust in government decreased, rather than increased, in survey areas where it administered flood relief, for reasons we discuss below.

The literature is replete with arguments validating the centrality of government trust to natural disaster relief, especially in countries with low state capacity, like Guatemala. Carlin et al. (Reference Carlin, Love and Zechmeister2014, 432) summarized the problem aptly, arguing, with regard to disaster relief, that:

In the case of state strength, interpersonal trust, a core element of social capital, remains intact. In the context of state weakness, it breaks down and potentially starts a downward spiral whereby mistrust drives down social capital, in turn … hampers short-run recovery.

Consistent with Carlin et al.’s study of earthquakes in Chile in 2010, El Salvador in 2001, and Haiti in 2010, other researchers have also reported notable impacts on trust in government in Bangladesh (Eisenstadt et al. Reference Eisenstadt, Haque, Toman and Wright2024), China (You et al. Reference You, Huang and Zhuang2019), and Mexico (Frost et al. Reference Frost, Kim, Scartascini, Zamora and Zechmeister2025), but not Western Europe (Albrecht Reference Albrecht2017). Frost et al. (Reference Frost, Kim, Scartascini, Zamora and Zechmeister2025) report a fairly strong decline in trust in government, but that this decline can be mitigated by disaster assistance. Eisenstadt et al. (Reference Eisenstadt, Haque, Toman and Wright2024) and You et al. (Reference You, Huang and Zhuang2019) show that in cases of uneven and/or low levels development (Bangladesh and China), local governments can gain public trust from EWEs, if they distribute disaster relief effectively whereas higher level government officials gain less, if at all. Cooperman (Reference Cooperman2022, 1158) adds an additional twist, showing that mayors in Northeast Brazil (the region of greatest inequality) who declare droughts cause voters to “reward competent mayors” and “mayors trade relief” for votes.

In the most recent Latinobarómetro survey, Guatemala ranked last among the 18 Latin American countries in both support for democracy and satisfaction with democratic performance. Only 29 percent of Guatemalans expressed support for democracy, while 41 percent were indifferent, and 23 percent preferred authoritarianism—the least democratic responses in the region (Latinobarómetro 2023). Likewise, only 23 percent of Guatemalans reported satisfaction with how democracy works, placing the country among the lowest in Latin America (Latinobarómetro 2023). These indicators reflect widespread and persistent distrust in political institutions. Indeed, this erosion of trust is not new: as early as 2007, due to “decline in trust of the government,” the UN-backed International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) was established in response to growing concerns about corruption and impunity within the state, highlighting the longstanding crisis of legitimacy in Guatemala’s governance (Saks Reference Saks2024).Footnote 2 Consistently, in the 2023 World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators, Guatemala ranked in the 18th percentile globally for government effectiveness, signaling extremely low perceived state capacity (World Bank 2023).

After gathering and assessing public opinion of citizens in climate-vulnerable areas by conducting a 2023 national survey in Guatemala, we share the “polycentric” view that enormous resource burdens borne across levels of government (and non-governmental groups) will be needed to give opportunities to the most vulnerable to overcome climate impacts. However, unlike the few existing earlier characterizations of adaptation policy, which concluded that vulnerable citizens judged government adaptation policies based mostly on the efficacy of their implementation (see Eisenstadt et al. Reference Eisenstadt, Haque, Toman and Wright2022), we argue, with strong evidence, that the type of climate events in a given area (flooding versus droughts) may matter as much as how local (and other) officials react to these. Both types of extreme weather events are impacting increasing numbers of people, with total climate refugees expected to rise from some 32 million in 2022 to over 200 million annually by 2050 (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees 2023).

More broadly, we conclude that a prominent difference between flood and droughts may be that flood damage is immediate and dramatic, needing no further explanation. Drought damage, contrarily, absent Brazil-style “natural disaster declarations” bringing relief and publicity, brings no such attention or resources. This leaves residents to fend for themselves, which they seem to do quietly, considering their options as individuals without considering attribution of blame of their government or its shortcomings.

Early work on polycentrism (Ostrom Reference Ostrom2017) emerged to argue that different levels of government (and other interest groups) could, and should, work collaboratively to achieve accountability. To Sovacool and Brown (Reference Brown and Sovacool2011), polycentrism allows for multiple actors at multiple scales (from local to global) to compete, producing innovation, collaboration, and citizen inclusion. For these analysts, policies need to include both homogenizing and coordinating elements from international and national levels of governance, and local and heterogeneous components from decentralized governance reflecting local circumstances.

Arguing against this idealized vision of cooperative polycentrism, Morrison et al. (Reference Morrison, Neil Adger, Brown, Lemos, Huitema and Hughes2017) assert that polycentric climate mitigation and adaptation models fail to fully address power dynamics among different levels of governance. To Morrison et al. (Reference Morrison, Neil Adger, Brown, Lemos, Huitema and Hughes2017, 11), “while dominant conceptualizations of polycentric governance provide useful insights into the potential for climate mitigation and adaptation, present models downplay the powerful roles of higher levels including those of the nation state, as well as the more diffuse exercise of power at lower levels of governance.”

Both sets of “polycentrism” authors do point out what should be evident, that national governments have the resources and authority, while local authorities may only have citizen trust and support. But Eisenstadt et al. (Reference Eisenstadt, Haque, Toman and Wright2022) and You et al. (Reference You, Huang and Zhuang2019) show that local authorities did not always win trust and support, even when they performed well in the wake of natural disasters, as citizens in vulnerable communities often did not have the information to differentiate levels of government or the adaptation goods they received. The lesson seems to be that polycentric efforts may be able to tap a broader range of resources and perspectives, but that central governments must be strong enough and effective enough to lead these efforts.

But what happens when central governments are weak and ineffective and citizens do not trust them to begin with? Carlin et al. (Reference Carlin, Love and Zechmeister2014) show that nations with low state capacity to begin with often fail to gain trust after EWEs. Others, like Gardiner (Reference Gardiner2011) and Jamieson (Reference Jamieson2014) have argued that the international community may be the only actor with sufficient scope and resources (if the powerful “climate-forcing” nations cooperate) to implement a comprehensive solution to any climate-related problems (Gardiner Reference Gardiner2011; Jamieson Reference Jamieson2014). Yet, funding flows from developed nations to developing ones remain scant (Weikmans and Roberts Reference Weikmans and Timmons Roberts2019), and 3 percent of 1,700 adaptation initiatives surveyed to date had reported reducing climate risks (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change 2021), and climate adaptation efforts suffer the most basic problems in that “there is no metric to measure successful adaptation” (2021, 65) leaving any progress on adaptation “vague” (2021, 65). Despite 2023 movement at the UNFCCC meeting in the direction of mainstreaming adaptation into development assistance and “loss and damage” considerations, that promise has not been realized.

Similarly, few studies exist testing citizen attribution of damages from extreme weather events to government action on climate adaptation. How do governments handle climate disasters and how do such disasters affect citizen trust in government or perceptions of government efficacy? A “conventional wisdom” in the literature, that all adaptation is “local” (as opposed to being implemented by national-level or even international policies), has been partially disconfirmed, as national governments condition adaptation policies, even if local governments must implement these. Indeed, Eisenstadt et al. (Reference Eisenstadt, Haque, Toman and Wright2022) find that “general support for the need to have more government response to climate change does not readily translate into findings about which level of government should take a lead role.” Moreover, questions continue to pervade studies of adaptation and natural disaster relief about the relationship between these separate but parallel areas of study (Boulter et al. Reference Boulter, Palutikof, John Karoly, Boulter, Palutikof, Karoly and Guitart2013).

The failures of multiscalar governance to build resilience and help citizens “adapt in place” (with a minimum of migration) points to responsibility by national governments to lead efforts towards resilience. While our national sample did not report strong distinctions between citizen trust in flood-ravaged areas, drought-impacted areas, and areas of minimal EWE effects, when we reduced the sample to the most adversely affected victims, those who had been sufficiently impacted that they received disaster relief, there was a significant attitudinal difference between flood and drought victims. On average, the flood victims did have lower levels of trust in government, the drought victims did not. In the section that follows we situate the survey in Guatemala, where trust in government is low to begin with, even for those not victim of EWEs.

The Guatemala Case as an Ideal One for Assessing both Flood and Drought Events

As in the Bangladesh study (Eisenstadt et al. Reference Eisenstadt, Haque, Toman and Wright2024), Guatemala climate victims did not always distinguish between levels of government in ways that would make multifaceted “polycentrism” approaches a priority for people on the ground. Firsthand experience with climate disasters conditioned Guatemalan citizen attitudes about government performance more than their political preferences. But in Guatemala, we also compared how respondents experienced different forms of climate disasters differently. By selecting one of the only small nations with both extreme flooding and extreme drought, the researchers were able to distinguish the attitudinal differences between flood- and drought-zone respondents, as many variables were controlled by testing both flood and drought samples within the same country. As pointed out by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), 8.6 percent of Guatemalans were at risk for flood damage (a number close to our findings), and some 7.9 percent were at risk of “two hazards”Footnote 3 (UNDRR 2025, 31) which adds further urgency to the need to trust in government. In the following section we establish the ineffectiveness of governance in Guatemala, describe the nation’s distinctive zones of flooding and drought, and discuss our variables and hypotheses.

Guatemala has been a troubled state beset by corruption and government inefficiency, for decades (see for example Tarcena Arriola Reference Taracena Arriola2002). In 2006, the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala, a United Nations-Government of Guatemala collaboration, was formed to “outsource” anti-corruption efforts in Guatemala’s “weak and failed state” (Krylova Reference Krylova2017). Recent literature has considered Guatemala more of a predatory state (Schwartz Reference Schwartz2023) than a failed state, but either way, the government is not known as efficient or effective. The Climate Risk Index (Germanwatch 2021, 44) lists Guatemala among the world’s 20 most climate risk-prone nations from 2009 to 2019 with respect to lives lost and cost of physical damage due to climate-related extreme weather events.

Guatemala’s vulnerability to hurricanes and floods is widely evident. Some 235 deaths were attributed to Tropical Storm Alex alone, which left almost 210,000 homeless when it hit the country in 2010 (The World Bank 2011). A dozen hurricanes and tropical storms have ripped through the country over the last several decades, including Hurricane Mitch (1998), Tropical Storm Stan (2005), and Tropical Storm Agatha (2010). Government data shows EWEs have more than quintupled between 1980 and 2019 (Universidad del Valle 2019). Extreme droughts have also impacted millions in Guatemala. The 2014 drought affected 70 to 80 percent of Guatemala’s basic food crops and some 1.1 million people (over 6 percent of the national population), prompting the government to declare a national emergency (Schmidtke and Ober Reference Schmidtke and Ober2023). Even with a vastly increased rate of migration in recent years due to both drought in the country’s “Dry Corridor” (Madsen and Cifuentes Reference Madsen and Cifuentes2018) and flooding on the Pacific coast, the 2023 presidential election campaign scarcely mentioned these issues.

According to scientists, the variability in El Niño and La Niña, as they impact ocean currents, are at least partially attributable to human causes (Pörtner et al. Reference Pörtner, Roberts, Adams, Adler, Aldunce, Ali, Begum, Betts, Kerr and Biesbroek2022). These have helped induce some of Guatemala’s recent droughts and other climate-related and vulnerability-creating weather patterns.

The human impacts of Guatemala’s precarious climate may be exacerbated by its predatory government and lack of public resources. Recent scholarship views Guatemala as an uneven democracy with “reserve domains” of extreme discretion in areas like the judiciary and tax collection (Schwartz Reference Schwartz2023). The government is widely viewed as one of the region’s more corrupt and our sample confirmed this, with 84 percent of the combined sample believing that corruption is generalized to the point of impeding government action. Indeed, in our survey, respondents ranked trust in government institutions at the bottom of the scale, with trust in churches and armed forces at the top.

The government of Guatemala has at least partly failed to stem the harmful impacts of climate disasters, leading bold climate victims (and others) to migrate. Indeed, 44 percent of our survey sample knew people who had migrated. The then US Vice President Kamala Harris used her first 2020 international trip to implore Guatemalans to stay in Guatemala, noting that migration from Central America, and increasingly from Guatemala, was creating a crisis for US policy.

Hypotheses

Building on the literature discussed above, the empirical characteristics of Guatemala as a case for studying “maladaptation” as well as the results of our focus groups and survey, we raise the following hypotheses:

Vulnerability: Peoples’ perceptions of immediate flood threats, and their responses when these occur, differ from perceptions of the much less urgent and less imminent “slow harms” from droughts. Furthermore, in the Guatemala context, our descriptive analysis of the survey and focus groups study indicates that “maladaptation” is an increasing cause of migration in Guatemala. In our survey, 14 percent of respondents in the national sample said they had considered migrating due to climate-related causes. In the flood oversample area 37 percent stated they had considered migration due to climate change-related events, whereas in the “Dry Corridor” drought area the number was lower, 20 percent, but still slightly higher than the national average.

In flood areas, respondents conveyed frustration that people’s homes and livestock are in jeopardy and that the government is unable to protect them. Hence, we expect that people who have experienced flooding should put more direct blame on the government.

In the “Dry Corridor,” climate extremes trigger a series of events over months and years. For example, multiple focus group participants conveyed that the chain of events leading to their dissatisfaction with the government’s handling of climate adaptation was a “spiral of debt” (Maboudi et al. Reference Maboudi, Eisenstadt, Arce, Feoli and Antonio Giron Palacios2025). As demonstrated in our survey and others (see for example Rodriguez-Solorzano Reference Rodríguez-Solorzano2014), crop yields drop as a result of increasing heat and lack of water. Additionally, bacteria and fungus affect crops like coffee and tomatoes, causing farmers to buy additional pesticides and fertilizer to make up crop losses. Within a year or two, several small farmers said they owe so much debt that they must consider selling their land and relocating. They said that subsistence farmers accrue debt and then migrate. Thus, we expect that people exposed to drought (as a slow-onset event) face a lag between the start of the drought and their economic hardship, prompting them to put less direct blame on the government’s adaptation performance.

H1: The more respondents are exposed to flood as opposed to drought, the less likely they are satisfied with the government adaptation performance.

Physical Harm: We also hypothesize that people who have directly experienced monetary or physical harm due to climate change events (whether from flood or drought) are more likely to blame the government for those harms and hence be less satisfied with the government performance. This hypothesis is similar to our vulnerability hypothesis, but it emphasizes firsthand experience of harms and loss and damages (van de Linden et al. Reference van der Linden2015), rather than a general exposure to floods and drought. Evidence does exist from some of the aforementioned surveys of other vulnerable nations that direct experience of climate-related disasters has a significant impact on victim satisfaction with their government (particularly local governments). The “slow harms” logic applies here as well; flood victims directly connect these tragedies to failed government policies and “maladaptation,” whereas drought victims do not make these connections as directly, as the temporal distance between the commencement of drought and their economic displacement is greater and the causes more diffuse.

H2: The more respondents experience physical harm due to natural disasters, the less likely they are satisfied with the government adaptation performance.

Government Satisfaction: Finally, we hypothesize a positive relationship between general satisfaction with different government institutions and satisfaction with the government’s adaptation performance. Building on institutional trust theories (Sztompka Reference Sztompka1999; Kulin and Sevä Reference Kulin and Johansson Sevä2021), we predict that people with generally positive attitudes toward the government should also have a more positive attitude regarding its adaptation performance. That is, citizens who think the government is doing a good job in providing public goods in general should also think that it is competently providing more selective goods to those who are exposed to climate change extreme weather events and need adaptation provision. By contrast, those who do not trust the government and its performance in general, should also be less satisfied with its adaptation performance. Thus,

H3: The more respondents are satisfied with government institutions, the more likely they are satisfied with government performance as it relates to adaptation.

Data and Methods

To test our hypotheses, we use an original survey study conducted in Guatemala between May and June 2023, along with six focus groups and ten cognitive interviews (see Supplementary Material). The survey was fielded by Borge & Asociados (Borgeya), a well-known regional public opinion and market research company based in Costa Rica. The survey was conducted face-to-face and included a national sample of 950 adult respondents.Footnote 4 To ensure enough respondents from drought- and flood-prone regions, we also included an oversample of 400 adult respondents from climate change vulnerable areas (201 individuals from the drought-prone municipality of San Agustín Acasaguastlán in the department of Progreso in central Guatemala, and 199 individuals from the flood-prone municipality of Nueva Concepción in the department of Escuintla, on the Pacific coast).

The national sample was randomly selected from the adult citizen population according to a multistage, regionally stratified design. The proportion of urban to rural population was consistent with the Guatemalan 2018 Census data. After stratifying by urban/rural administrative units, a Population Proportional to Size (PPS) method was used to randomly select blocks within administrative units. A random route household selection within each sampling point was used to identify blocks in rural and urban areas.Footnote 5 Next, survey managers randomly selected one individual per household using the last/next birthday method. Last, post-stratification weights were computed using gender, education, and age (see Supplementary Material for more on the survey and focus groups).

Measuring Government Adaptation Performance

Our main outcome is public perception of the government’s adaptation performance. We estimate this outcome with a few questions. First, we asked respondents: “Have you received help to cope with natural disasters [shelter, food, post-disaster payment] in recent years?”Footnote 6 If they responded affirmatively, we followed with two more questions: “Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the quality of help received in the case of a natural disaster?” and “Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with how natural disaster relief is delivered?” The response to these two questions occupied a five-point scale, ranging from “very satisfied” to “not satisfied at all.” Next, we asked the respondents, “Were infrastructure works [embankments, levees, hurricane shelters] built in your area?” And if they responded affirmatively, we followed-up with “Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the construction of those works?” Similarly, the response to this question ranged from “very satisfied” to “not satisfied at all.”

These two questions specifically focused on respondents who received adaptation goods from the government, whether in the form of direct payments, food, temporary shelters, or embankment construction near flood areas, and fertilizers, pesticides, and water provision in drought areas. Only 11 percent of our survey respondents reported that they had received help from the government to cope with natural disasters in recent years. Meanwhile, 15 percent reported that there were climate-related infrastructure works built in their area. As Figure 1 shows, most respondents who received adaptation goods were satisfied with the government performance.

Figure 1 Satisfaction with Adaptation Goods Received.

While these government adaptation performance measures (satisfaction with quality of help, satisfaction with natural disaster relief, and satisfaction with adaptation infrastructure) were particularly important for capturing the attitudes of vulnerable citizens who received government adaptation assistance, they failed to consider the attitudes of many other vulnerable citizens that did not benefit from government action. To assess the attitudes of all citizens regarding the government’s adaptation performance (regardless of whether they received adaptation goods or not), we asked four binary questions.Footnote 7

Each of these questions estimates public satisfaction with levels of government services related to adaptation performance. As Figure 2 shows, while respondents were divided over COCODE’sFootnote 8 performance (with 50.3% assessing COCODE performance positively), the majority did not consider their mayors, local governments, or national government to be doing a good job regarding policies that relate to climate change. Almost 70 percent of respondents had negative opinions about their mayor’s performance, 71.5 percent had negative opinions about their local governments, and 76.4 percent about the national government.

Figure 2 Attitudes towards Government Adaptation Performance.

We also created an additive “Performance” index, combining the scores for these four variables. Our Performance Index, thus, ranges from 0 (for respondents who believed the government at all levels had performed poorly) to 4 (for those who believed the government at all levels had performed well). The mean of our Performance Index is 1.4 (with a 1.4 standard deviation), indicating that on average most respondents believed that the government at the national and local level had not performed satisfactorily regarding climate change.

Measuring the Explanatory Variables

Corresponding to our three hypotheses, our main explanatory variables included perceived vulnerability to extreme weather exposure, experiencing physical harm due to climate change, and general government satisfaction. To operationalize the first hypothesis, extreme weather exposure, we asked two questions: 1) “Where you live, has the level of floods in the past five years been much lower, lower, the same, higher, or much higher?” 2) “Where you live, has the level of drought in the past five years been much lower, lower, the same, higher, or much higher?” For our Flood Perception variable, while only 22 percent of respondents in the national sample and 18 percent in the drought sample reported increases in flooding, fully 59 percent of the flood sample respondents reported an increased frequency of flooding. Similarly, for the Drought Perception variable, only 33 percent of respondents in the national sample (and 52 percent in the flood sample) reported more drought over the past five years, while 56 percent of respondents in the drought sample reported more exposure to drought during the same period.

To operationalize physical harm due to natural disasters, we used four binary questions. First, we asked respondents if their house had suffered damage due to natural disasters (Home Damage variable). Next, we asked if anyone in their household had suffered physical harm due to natural disasters (Physical Harm variable). We also asked if they had been forced to leave their house temporarily due to natural disasters (Temporary Relocation variable). Lastly, we asked if respondents knew anyone who had experienced economic loss due to climate-related natural disasters (rise in level of ocean/river/lake, drought, hurricanes, floods and/or landslides due to rains, and extreme heat) in the last five years.Footnote 9 We created an index (Economic Loss variable) ranging from 0 (where respondents did not know anyone who lost anything due to any of those natural disasters) to 5 (where they knew at least one person who experienced economic loss due to each of these disasters).

To operationalize overall government trust, we utilized several questions from our survey. First, we asked respondents to rate on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 7 (a lot) how much they trusted the judicial system, the congress, political parties, the president, and the municipalities. We then aggregated these five ordered categorical variables and scaled them to 100 to create our Government Trust Index. We sought to gather an abstract index of an individual’s level of trust, with no relation to climate-based functions. We also sought respondent opinions on the following statement: “Corruption in Guatemala is so pervasive that it impedes government action.” The Perception of Corruption variable ranges from 1 (not true at all) to 4 (very true). Next, we asked two more specific questions regarding government effectiveness. We asked respondents “How do you rate the effectiveness of the government in providing basic services [like education and public health]?” Our Government Effectiveness (public goods) variable ranged from 1 (very bad) to 5 (very good). Finally, we asked the survey respondents: “Talking about environmental protection in the country, do you trust or not trust that the government will protect Guatemala’s natural environment?” Our Government Environmental Protection is a binary variable, where 1 indicates confidence in the government.

Control Variables

We also controlled for climate change perception. Normatively, we expected that citizens not believing in the climate threat would be less worried about government performance in adapting to it, and by extension, less critical of its performance in providing adaptation goods. We asked the survey respondents: “If nothing is done to reduce climate change in the future, how serious do you think the problem will be for Guatemala?” The response to our Climate Change Urgency variable ranges from 1, for “not serious at all,” to 4, for “very serious.”Footnote 10

Finally, in our estimated models we controlled for demographic variables including respondent genders (binary variable coded 1 for female) and their level of income (ordered categories on a scale of 1 to 7), as well as a binary variable for access to basic public goods (whether their home accessed drinking water and/or is connected to the power grid). Our general prediction here was that women and citizens with higher incomes and better access to public goods might be more likely to have positive attitudes towards government performance. Much analysis indicates that women in developing countries are more likely to experience firsthand climate vulnerabilities and other economic shocks (Yavinsky Reference Yavinsky2012 and Momtaz and Asaduzzaman Reference Momtaz and Asaduzzaman2019). We also expected that citizens who were doing better economically might be less critical of government performance.

Results and Discussion

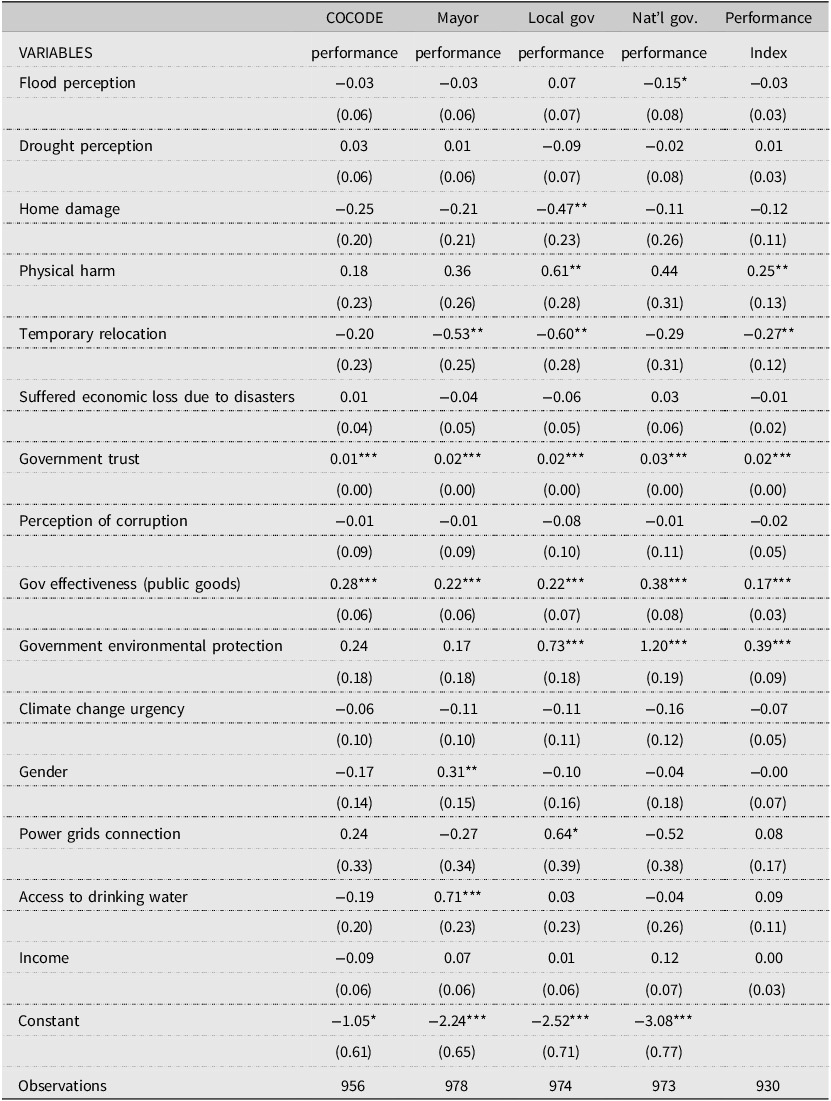

Table 1 shows the results for the relationship between our main independent variables and satisfaction with different levels of government performance regarding environmental issues in general. To assess attitudes regarding the government’s climate change performance, we estimated logit models using four binary outcome variables measuring satisfaction with government performance regarding climate-related natural disasters. We also estimated an ordered probit model using our Performance Index which is an ordered categorical variable.

Table 1. Satisfaction with Government Adaptation Performance

Standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

We find that flood perception has a negative and statistically significant (at marginal levels) correlation with national government performance satisfaction (i.e., those who think floods have gotten worse in the past five years are generally less satisfied with national government adaptation performance). The results, however, are only marginally significant for this variable and not statistically significant for all other variables. Hence, we cannot empirically support our H1 using this broader sample of respondents. Our hypothesis differentiating the attitudes of flood-impacted and drought-impacted respondents also does not find overwhelming validation.

Results from Table 1 also show that having experienced home damage due to climate events corresponds with a negative and statistically significant impact on perceived local government performance. Meanwhile, being forced to relocate due to natural disasters also has a negative and statistically significant correlation with respondents’ assessments of their mayors’ and local government’s’ performance as well as the overall Performance Index. In other words, those who were forced to temporarily relocate due to climate-related disasters have a more negative attitude towards the government’s adaptation performance. However, respondents experiencing physical harm due to climate events have a more positive attitude toward local government performance and the overall Performance Index. This finding is counterintuitive, but we suspect that those who have experienced physical harm might have received more or better compensation from the government, compared to those who were forced to relocate or lost their homes. Regardless, our results here are mixed, and at best, we find only some limited empirical evidence supporting our physical harm hypothesis (H2).

Finally, our results in Table 1 provide strong evidence in support of the government satisfaction hypothesis (H3). The results show positive and statistically significant correlations between trust in government and all the outcome variables. Similarly, positive attitudes toward government effectiveness in providing public goods have positive and statistically significant correlations with all dependent variables. Also, positive attitudes toward government environmental protection correlates positively and significantly with respondents’ evaluation of their local and national government adaptation performance and with the overall government Performance Index. Overall, these results lend strong empirical support to our government satisfaction hypothesis.

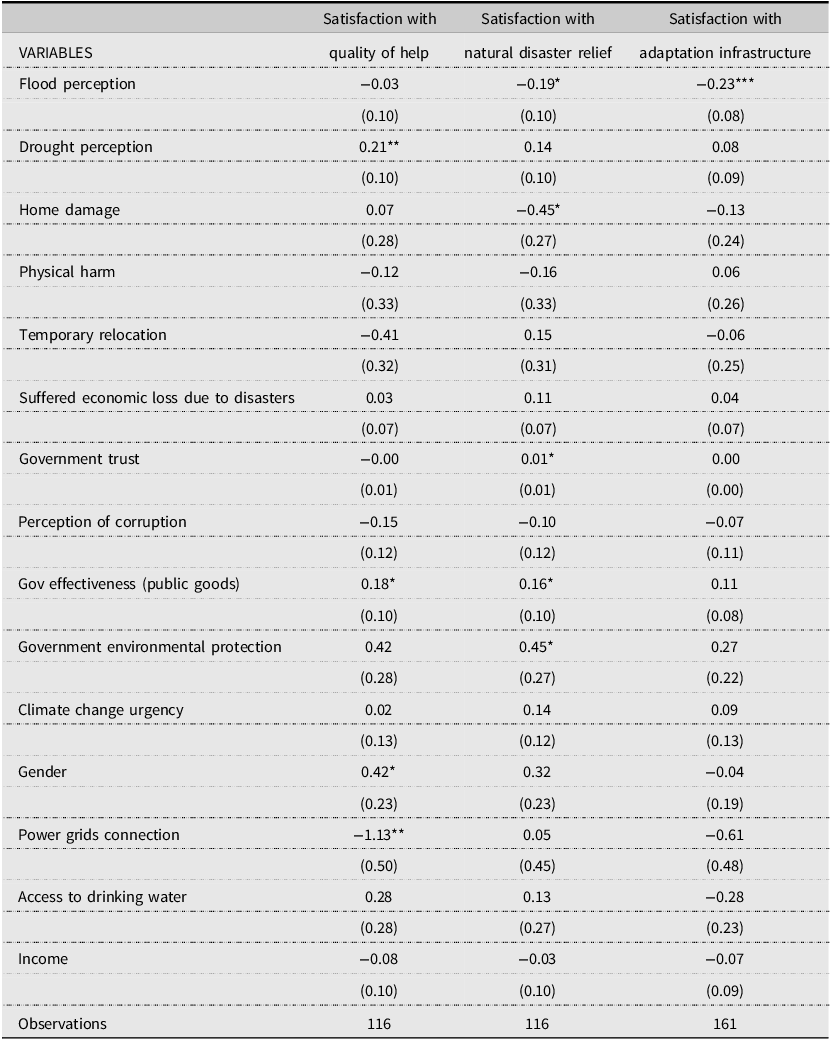

While statistically significant across many variables, the results from Table 1 do not strongly differentiate the attitudes of those who perceive increases of flooding versus those who perceive increases in drought among the entire sample. But the uniformity of the results of the full sample does mask distinctive findings among the subset of respondents (11 percent), who had themselves received adaptation “goods” in the form of particularistic disaster relief or more collective embankments and vulnerability-reducing infrastructure. Table 2 analyses this subsample of respondents. These results are more robust and consistent with our premise that flood victims and drought victims may have different attitudes towards the government.

Table 2. Satisfaction with Adaptation Goods Provision

Standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Considering that our set of outcomes here (i.e., satisfaction with adaptation goods) is ordered categorical variables, we estimated ordered probit models to test our hypotheses. Table 2 shows the impact of different explanatory variables on satisfaction with the quality of “adaptation goods” received. First, the results show that while perceived vulnerability to flood (flood perception) has a negative correlation with satisfaction with the quality of adaptation goods, perceived vulnerability to drought has a positive correlation. That is, those who think floods have gotten worse in the past five years are generally less satisfied with government adaptation performance while those who think droughts have gotten worse are more satisfied, lending empirical support to our first hypothesis (H1).

We could not, however, find strong empirical evidence in support of H2. The only supportive evidence is that there is a negative and statistically significant correlation (albeit only marginally) between suffering home damage due to climate change and satisfaction with natural disasters relief received. That is, those who suffered home damage due to climate change are less satisfied with disaster relief they received from the government. The relationships for all other explanatory variables for H2 are insignificant.

Finally, we do find support for our government satisfaction hypothesis (H3). We find a positive and statistically significant (at a marginal level) relationship between trust in government and satisfaction with relief received after climate-related disasters. Similarly, positive attitudes towards government environmental protection correlate positively with the same outcome. Lastly, we find that positive attitudes towards overall government effectiveness in providing public goods positively correlate with satisfactions with the first two outcomes in Table 2 (satisfaction with the quality of help and natural disaster relief). Taken together, these results provide some empirical support, beyond that given on Table 1, for our government satisfaction hypothesis (H3).Footnote 11

As we discussed above, while the outcomes in Table 2 (satisfaction with quality of help, satisfaction with natural disaster relief, and satisfaction with adaptation infrastructure) are particularly important for capturing the attitudes of those who have received government adaptation assistance, they fail to consider the attitudes of those who have not been the beneficiaries of government action regarding adaptation. However, Table 2 shows that for respondents with firsthand experience receiving government adaptation goods, perception of higher levels of flood seem to make respondents more critical of government adaptation policy, whereas drought perception does not seem to affect respondents’ satisfaction with the government. We offer validation to the claim that vulnerable citizens’ attitudes are strongly impacted by floods, which are dramatic, immediate, and disruptive, but not by drought, which is incremental and gradual.

Comparing our results from Tables 1 and 2 allows us to draw a few conclusions. First, our results are not conclusive regarding the physical harm hypothesis (H2). As Table 2 shows, our various physical harm variables were not determinants of “satisfaction with adaptation goods” outcomes. And the results were mixed in Table 1 with two explanatory variables (temporary relocation and home damage) acting in the predicted direction with “satisfaction with government climate change performance” outcomes and one variable (physical damage) acting in the opposite direction. Second, we found supportive evidence for our vulnerability hypothesis, the novel hypothesis presented here, only in Table 2. That is, while vulnerability to flooding is a significant predictor of “satisfaction with adaptation goods,” it could not predict our “satisfaction with government climate change performance” outcomes. In other words, respondents exposed to flood—rather than drought—are less likely to be satisfied with adaptation goods they have received. Exposure to flood, however, does not necessarily lead to satisfaction (or lack of it) with government’s overall climate change performance.

We found evidence for our government satisfaction hypothesis in Table 1. That is, while various levels of satisfaction with government variables were not significant predictors of “satisfaction with adaptation goods” outcomes, they seem to predict our various “satisfaction with government climate change performance” outcomes. This makes normative sense to us, as citizens who have generally positive attitudes toward the government and its performance are also expected to have more positive attitudes toward its climate change performance. Stated differently, the more respondents are satisfied with government institutions, the more likely they are satisfied with the government adaptation performance, but not necessarily with the quality of adaptation aid if they have received any.

Differentiating Forms of Maladaptation: Divergent Attitudes, Droughts and Floods

Field research affirmed the great difference between those impacted by climate-related drought and those affected by climate-related floods, as highlighted mostly in Table 2. Flood zone victims were much more likely to recognize they had experienced economic losses that were climate related, were much more likely to consider migrating to the United States or other nations and had much greater direct impacts related to heat. Moreover, while government officials acknowledged that flooding is widely attributed to climate change, many, but not all, government programs address climatic causes of drought in Guatemala’s central “Dry Corridor” (Saul Reference Saul2022). Indeed, while respondents in the flood area oversample reported that the intensity of rain was the biggest problem they faced (48 percent), whereas those in the drought area oversample said that their biggest problem was the proliferation of “plagues” on their crops (43 percent).

Focus groups were held in areas targeted for the flood oversample, where the Coyolate River had flooded severely in 2011, to such an extent that some 11 years later, communities on the northern bank of the river had still not recovered. The river has been dammed by an embankment protecting sugar cane-producing lands on the east bank, but those on the west bank claimed embankments worsened flooding on their side. “The river used to be a beauty,” said one resident, “but now it is a disaster.” The citizens of Nueva Concepción (the east bank of the Coyolate) argued that the sugar cane companies only worried about their resources and workers (on the west bank), and that the government had appropriated resources which were supposed to be designated for them.

Most of the focus group participants in Nueva Concepción said that their vulnerability to flooding (which still occurred routinely) had diminished the production of their lands dramatically and kept them from overcoming a subsistence lifestyle, and a government official agreed that the connection between poverty and climate impacts was strong and required further specification (Vasquez Reference Vasquez2022). Connections drawn by vulnerable residents between climate change and flooding, and between government ineffectiveness and flooding, were uniformly strong, just as the survey implied.

In the drought area, focus groups yielded more ambiguous results, which were also highlighted in the survey. A cycle of subsistence and poverty was also identified by focus group participants in the community of La Bolsa, for example, but respondents did not tie it directly to climate change. Small farmers said that an increase in fungus on crops and diminished crop yields were forcing small farmers to use more pesticides and fertilizers, which in turn caused them to go into debt to buy these inputs. The need to purchase inputs to fight plagues like fungus and insects were named in the survey by 43 percent of the drought area sample as the greatest cause of economic problems (compared to 25 percent of the national sample and 37 percent of the flood sample). One drought victim (interview) conveyed what seemed like a common story; he had gone into debt, migrated to the United States, where he still had family, but was deported and is trying again to farm in Guatemala’s “Dry Corridor,” but also picking coffee and other crops on a seasonal basis.

Conclusions: The Urgent Need to Subsume Disaster Relief into Adaptation Planning

As anticipated by the “slow harms” literature, the most climate vulnerable, even those affected directly by heat and drought, often do not directly associate drought with climate change. The flood-affected vulnerable are much quicker to associate their experience with climate change, and to blame government. As we demonstrated, experience with flood damage is a significant cause of negative views of government performance, whereas drought is not.

Drought is more complex, requiring a longer and more diffuse chain of causal events leading from the diminishment of crop yields due to plagues and crop failure associated with drought. Drought is also more difficult to identify, as observation of drought requires data gathered over months or even years, while tsunamis and ocean-born tidal waves can rip communities apart in seconds and riverine floods can wreak havoc within minutes. Small wonder that the those impacted by droughts did not register the same level of frustration with government attention related to the climate disaster. Guatemalan government officials interviewed stated the nation’s interest in making citizens aware of climate impacts in the “Dry Corridor” as well as on coastal lands and riverbanks. Still, analysts can imagine instances where local officials may not want to tie drought-related harms to climate change, as this would make these harms more preventable or at least predictable, meaning that policies and resources could be marshalled before dry spells turn to droughts.

Drought is a grave concern, and much less transparent than flooding. In Guatemala, the “Dry Corridor” peasant farmers may have less recourse than flood victims, as the land is uniformly less fertile, causing migration. Data is scarce, but drought may be more closely tied to destitution. Drought is also less transparent, and government seems to have less accountability in reacting to drought. The UN International Office on Migration associates drought and flood with Guatemalan (and broader Central American) climate migration but argues that drought may be a more profound cause given the dependence of over 30 percent of Guatemalan agriculture on rainfall (Escribano Reference Escribano2023). Further research is needed to pinpoint the impact of drought on civil wars and migration, but regardless of the “threat multiplier” impact of this condition, an international drought warning system with data collection in each country might serve to help keep the vulnerable informed and enable quicker action and accountability.

Returning to “polycentrism,” the analysis shows the crucial role government plays in adaptation assistance. Even when government capacity across the Global South remains uneven, national and local governments become first respondents and vulnerable populations are able to assign blame or credit for their actions. Further research is needed to assess whether better coordination between government and civil society actors may partially compensate for shortcomings in state capacity. Adaptation solutions are often considered localized and idiosyncratic. But the type of EWE and the scope of assistance after disasters matters. Our findings imply that assistance-receiving respondents in flood areas were ill served by government assistance, but the difference between those in flood areas and in drought areas, may just be that droughts are less immediately and directly tied to policy performance. But either way, the form of EWE and, by implication, how relief efforts are undertaken by government authorities, need to be considered broadly by national governments and international donors, who can identify flood, drought, and other EWE patterns and “best practice” responses, as well as by local officials bearing local knowledge and contexts. And patterning policy responses to a range of the most frequent EWEs is the purview of adaptation planners, rather than just “disaster responders,” whose spontaneous, rather than deliberated, actions have passed as national adaptation policies in the past.

More broadly, the findings are a call for a more direct integration of short-term disaster relief and more permanent climate adaptation policies. Over a decade ago, Boulter et al. (Reference Boulter, Palutikof, John Karoly, Boulter, Palutikof, Karoly and Guitart2013, 248) warned that adaptation policies needed to be separated from disaster relief, so that EWEs could stop being treated as “part of a relatively stable pattern of natural variability” and instead considered as the “new normal,” allowing resources to be channeled into adaptation planning rather than just post-disaster clean up. Our findings add urgency to the need to consciously merge these two parallel sets of policies, especially in drought areas, so that victims can be made more aware of patterns adverse to their families’ well-being so they can make singular and well-considered choices, rather than taking a series of improvised and incremental decisions, which often ultimately lead to migration. Even if low-capacity states like Guatemala do not have resources to distribute resources, they can help vulnerable area residents make more informed choices at little cost by conveying that these are normalizing weather patterns requiring greater attention.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2025.10040

Data availability statement

Data files can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/IL5X54

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Aracely Martínez and Edwin Castellanos of the Universidad del Valle in Guatemala and recognize funding for the survey from American University, Loyola University Chicago, and Tulane University.

Competing interests

the authors declare none.