Introduction

New political parties pose significant challenges for established parties. Newcomers can shoot to prominence, raise new issues in electoral campaigns, and often verbally attack established parties. Losing voters to these parties is undoubtedly a concern among leaders of established parties. But how do supporters of established parties want their parties to respond to new parties? Do voters prefer that their party fight back against the new party or accommodate its policy positions? And what if the established party’s electorate is divided concerning its position towards the new party’s policy proposals? Could obfuscation, ignoring the newcomer, or even explicitly staking out multiple positions offer a viable approach for a party to accommodate the views of its divided electorate? While research examines how parties’ strategies impact voter perceptions (e.g., Plescia and Staniek Reference Plescia and Staniek2017; Fernandez-Vazquez Reference Fernandez-Vazquez2019; Hjorth and Larsen Reference Hjorth and Larsen2022; Nasr Reference Nasr2023), less is known about voter support for particular party responses to new parties. What party responses voters like is not merely of academic interest; many politicians would like to know how to best retain their voters.

Studies of party strategy and voter transitions have examined how parties react to losing votes to other parties after an election (Somer-Topcu Reference Somer-Topcu2009; Abou-Chadi and Stoetzer Reference Abou-Chadi and Stoetzer2020). In contrast, we explore what parties can do to preemptively prevent the loss of party supporters. We examine the responses that voters prefer their parties to take and which they dislike. If party leaders know what responses appeal to their voters, they can better fend off challenges before they lose the support of their base. The party competition literature makes assumptions about how voters respond to strategies that parties employ but does not directly test them (e.g., Meguid Reference Meguid2005). Existing evidence for how party supporters evaluate the various strategies that parties take when fending off newcomers is indirect (but see Hjorth and Larsen Reference Hjorth and Larsen2022).

We study how voters perceive existing parties’ responses to the rise of new parties – a necessary step towards understanding why voters switch their support from established parties to newcomers and, ultimately, why these new parties are successful. As new parties change the landscape of European politics (De Vries and Hobolt Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020; Haughton and Deegan-Krause Reference Haughton and Deegan-Krause2020), understanding how voters view party competition, in particular between new and existing parties, takes on greater normative importance. While we test two pre-registered hypotheses – one regarding support for unified versus divided party responses and another about support for party responses that are (in)congruent with voters’ policy preferences – our study is largely exploratory in nature. In an original survey with almost 20,000 respondents fielded in 14 European countries, we assess how voters react to the ways in which existing parties could respond to a new party. We also explore the effects of contextual factors, such as the issue on which the new party campaigns, whether the new party is populist, and the party family of the supporter’s party.

In our experimental design, we first elicit respondents’ most preferred party from an encompassing list of parties competing in national elections. We then show each respondent a series of vignettes in which a hypothetical new party presents a threat to the party supported by the respondent. The new party can seek voter support by making a policy proposal as well as through various forms of attacks on the established parties. The respondent’s preferred party can react in different ways as well, using responses designed to mirror strategies posited in the existing party competition literature (Meguid Reference Meguid2005, Reference Meguid2008; Adams and Somer-Topcu Reference Adams and Somer-Topcu2009; Somer-Topcu Reference Somer-Topcu2015). Importantly, we vary whether the respondent’s preferred party is united or divided in its response to the new party, as voters tend to prefer unified over divided parties (e.g., Müller Reference Müller2000; Ferrara and Weishaupt Reference Ferrara and Weishaupt2004; Kam Reference Kam2009; Greene and Haber Reference Greene and Haber2015; Lehrer, Stöckle and Juhl Reference Lehrer, Stöckle and Juhl2024). Thus, we can experimentally determine which responses work best, whether a unified public face is always desirable, and under what conditions different approaches are more successful.

Our findings show that voter support for a particular party response strongly depends on the voters’ own policy stances. Established parties may find themselves between Scylla and Charybdis if the newcomers campaign on an issue that divides their party base. Voters want their party to fight back against a newcomer when they disagree with the new party’s policy position. But they prefer accommodation if they agree with the new party. If both groups of voters are equally represented among supporters of one party, the leadership may find itself taking a divided approach, either intentionally through the strategic blurring of position or unintentionally because the party cannot agree on the best response.

Party competition in the face of new parties

Party competition research seeks to understand how established parties respond when faced with a growing threat from new parties encroaching on their support base (e.g., Meguid Reference Meguid2005, Reference Meguid2008; Adams and Somer-Topcu Reference Adams and Somer-Topcu2009; Abou-Chadi Reference Abou-Chadi2016). It also examines how smaller, niche parties differ from their mainstream counterparts (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006) and why new parties emerge, along with the reasons for their subsequent success or failure (e.g., Tavits Reference Tavits2006; Bolleyer Reference Bolleyer2013; Haughton and Deegan-Krause Reference Haughton and Deegan-Krause2020). Additionally, research has explored the impact of new political entrepreneurs on party competition across Europe (e.g., Hobolt and De Vries Reference Hobolt and De Vries2015; De Vries and Hobolt Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020). And issue yield theory examines how voters react to party strategies and what these reactions imply for parties when selecting issues to emphasize (De Sio and Weber Reference De Sio and Weber2014).

The existing research on party competition in the face of new or challenger parties focuses on observing what established parties do, uncovering their movements and strategies as they engage in electoral competition, and examining the impact of those actions on their subsequent electoral success (e.g., Adams and Somer-Topcu Reference Adams and Somer-Topcu2009; Abou-Chadi Reference Abou-Chadi2016; Abou-Chadi and Krause Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020). Issue yield research (e.g., De Sio and Weber Reference De Sio and Weber2014) emphasizes that parties must balance the preferences of their core supporters against the wishes of the wider electorate when selecting the mix of issues and policy positions to emphasize.

We take a slightly different approach: like issue yield research, we focus on what supporters of existing parties wish their parties to do, but like other party competition literature, we explicitly focus on the increasingly common scenario of facing a new party. While much recent research has examined the impact of party behavior on voter perceptions (e.g., Fernandez-Vazquez and Somer-Topcu Reference Fernandez-Vazquez and Somer-Topcu2019; Hjorth and Larsen Reference Hjorth and Larsen2022; Wagner and Meyer Reference Wagner and Meyer2023), little research looks explicitly at voter support for particular party behavior when faced with a new threat. We look at support for different party responses among party supporters, rather than examine how voters in general perceive the party or whether they would vote for it.

To uncover what supporters would like their party to do when facing competition from a new party, we must determine both the nature of the challenge that a party is likely to face and the nature of responses available to them to fight it. In designing an electoral attack, new parties look for new issues and policy positions that the existing constellation of political parties fails to cover, including wedge issues over which the existing parties are internally divided (Jeong et al. Reference Jeong, Miller, Schofield and Sened2011; Hillygus and Shields Reference Hillygus and Shields2014; van de Wardt, De Vries, and Hobolt Reference van de Wardt, De Vries and Hobolt2014). Established parties must come up with positions on issues that they have either not given much attention to, that they have purposefully suppressed to cover up internal divisions, or that they thought were considered socially taboo. In developing policy positions on these new issues, established parties may fight or accommodate the positions of the new party. They may also try to present a unified face to the public, or they may strategically engage in obfuscation of their position, perhaps through silence or by airing different viewpoints within the party to appeal to a wider audience (Han Reference Han2020). Or they may simply reveal internal divisions to the public because they are unable to keep them under wraps.

In her influential work, Meguid (Reference Meguid2005, Reference Meguid2008) has argued that the strategies established parties use to compete with upstarts can affect the electoral success of those upstarts because they impact voters’ behavior. She lays out several possible strategies that established parties can use when facing a new challenger. An established party can be dismissive of the new party, effectively ignoring it and the positions that it takes; accommodative, adopting the stance of the new party; or adversarial, confronting and combating its policy views. Ultimately, the interaction of the strategies of several established parties vis-à-vis the new party impacts its success.

Studies have examined specific aspects of Meguid’s theory, for instance, how social democratic parties react to the rise of the populist far-right (Bale et al. Reference Bale, Green-Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010), asking whether they can maintain support among traditionally socially conservative anti-immigrant working-class voters in the face of competition from these new parties. More recent studies have found that radical-right success leads both center-left and center-right established parties to take more culturally protectionist positions (Abou-Chadi and Krause Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020), but that such accommodation can have unintended consequences, leading to higher support for the radical right (Krause, Cohen, and Abou-Chadi Reference Krause, Cohen and Abou-Chadi2023) and benefiting only mainstream left parties, not the mainstream right (Spoon and Klüver Reference Spoon and Klüver2020; Hjorth and Larsen Reference Hjorth and Larsen2022).

Such accommodative strategies, in particular, imply that parties shift policy positions to retain or gain voters. However, supporters of some parties are likely more tolerant of party movement than those of other parties. Some parties may be better able to adopt new positions on some dimensions than others (Tavits Reference Tavits2007, Reference Tavits2008; Koedam Reference Koedam2022). And supporters of niche parties are often loath to see their party change position, sacrificing their policy ideals to compete with others (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006; Ezrow et al. Reference Ezrow, de Vries, Steenbergen and Edwards2010). Such results highlight that while there are some basic strategies that parties can pursue, the way that their voters react to their strategy is likely to depend on the type of party they are, the nature of their supporters, and the nature of the party that is challenging them. In other words, supporters’ endorsement of different strategies is likely contingent on circumstances.

Despite this contingency, a key result of much research on party strategy towards new parties is that unified parties are better at retaining support than divided ones (e.g., Müller Reference Müller2000; Ferrara and Weishaupt Reference Ferrara and Weishaupt2004; Kam Reference Kam2009; Greene and Haber Reference Greene and Haber2015; Lehrer, Stöckle, and Juhl Reference Lehrer, Stöckle and Juhl2024). Supporters should prefer parties that can, at the very least, agree on a position and a strategy. The literature on legislative organization and behavior suggests that voters are better able to ascertain what a unified party stands for, and parties develop a ‘brand’ that can serve as a shortcut for voters when deciding whom to vote for (Kiewiet and McCubbins Reference Kiewiet and McCubbins1991; Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005; Kam Reference Kam2009; Proksch and Slapin Reference Proksch and Slapin2015). As a consequence, parties try to prevent their internal divisions and fights from spilling out into public view (e.g., van de Wardt Reference van de Wardt, De Vries and Hobolt2014).

However, some research challenges the notion that parties always benefit from unity and instead provides evidence that, under some circumstances, voters may interpret differing or unclear party positions positively, even leading parties to strategically build more ambiguity into their positions (Rovny Reference Rovny2012, Reference Rovny2013; Somer-Topcu Reference Somer-Topcu2015; Lo, Proksch, and Slapin Reference Lo, Proksch and Slapin2016; Bräuninger and Giger Reference Bräuninger and Giger2018; Koedam Reference Koedam2021; Han Reference Han2022). Ambiguity in a party’s position implies that voters are unable to determine with certainty the policies that a party supports. Parties may generate ambiguity – either strategically or unintentionally – by stating multiple, perhaps conflicting, positions or through staying silent. Different actors within the party can take positions at odds with one another.

In the presence of multiple positions, voters may simply hear the position that they support and assume that it is the true position of the party. When a party remains silent, voters may project their own preference onto the party, believing it to support their stance. Thus, by creating ambiguity, a party might be able to cast a wide net for voters and garner support from different parts of the ideological spectrum (Somer-Topcu Reference Somer-Topcu2015). Of course, in other instances, voters may view the same contradictory position-taking and silence as indicative of party infighting, discord, and harmful disunity. If voters sense intraparty conflict, open division may be likely to harm the party, even if it means that the party represents a wider range of positions.Footnote 1

We still lack an understanding of when the valence-based advantages of unity that voters may associate with competence, reliability, or ideological purity are outweighed by the spatial advantages of blurring or ambiguity that diminish voters’ perceived ideological distance to the party by offering a wide range of positions. Taken together, existing research suggests that the approaches established parties take when competing against upstarts impact how voters behave and potentially how they view the parties they support. Exactly how voters, and in particular supporters, evaluate these approaches, though, has not been examined experimentally.Footnote 2

The existing observational literature on how mainstream parties react to new and challenger parties shows how parties using particular strategies fare with voters over time. But we do not know whether voters truly like how parties respond or whether they are reacting to something else that is difficult to control for. Voters may, for example, react to different types of new parties rather than the established party’s approach towards competing with them. Most social democratic parties do not explicitly accommodate when faced with a radical-right challenger, and most green parties are adversarial towards them, rendering it hard to identify the effect of strategy as it is collinear with the type of challenger. Parties may not use all available strategies, and, in addition, they may not use those strategies that would gain the most traction with voters, at least not in all situations. For example, they may fear employing a particular strategy if they believe it might jeopardize their chances to form a governing coalition with another party. Thus, while observational studies provide us with important insights, it is nonetheless difficult to learn about how supporters specifically evaluate parties’ actions towards newcomers without the aid of experimental studies.

We design a survey experiment in which parties randomly adopt responses (or reactions) to counter an electoral challenge from a new party. We measure whether supporters of that party like the chosen response. Our experimental approach allows us to control the way in which party supporters experience their party’s responses to new challenges, while simultaneously offering us the opportunity to explore the various contextual factors, such as a party’s governing status, the nature of the issue on which the challenge occurs, the type of rhetoric that a challenger uses, and the country and party system in which the challenge occurs. We test two basic, preregistered hypotheses, derived from assumptions in the literature, but then analyze a wide variety of contextual factors in a more exploratory manner (see the ‘Subgroup effects and experimental context’ section).Footnote 3

Our first hypothesis states:

Hypothesis 1 Respondents prefer unified party reactions over divided party responses.

If confirmed, this hypothesis suggests that parties are best off trying to keep quiet about disagreements in public rather than showing disunity. It also would suggest that ambiguity – or at least the kind created by contradictory statements – is not appreciated by party supporters.

Our second hypothesis states:

Hypothesis 2 Respondents prefer party reactions that reflect the ideological position they support.

Through this hypothesis we examine how supporters’ ideological congruence with the policy position of the new party impacts their support for a particular response by their preferred established party. We fully expect supporters to endorse their parties’ use of responses that affirm their own substantive positions. It would be odd if they did not. However, supporters’ preference for substantive congruence has interesting implications for the strategies of established parties to retain their base’s support, especially when a party’s support base is divided. When facing a divided base, engaging in mixed messages or ambiguity may be the optimal response.

Our design explicitly allows for the possibility that supporters’ desire for substantive policy representation on the issue raised by the new party leads to instances where supporters, in the aggregate, prefer a divided response from the established party over a unified response. We, therefore, examine support for different party responses, varying the ideological congruence between the respondent and the new party.Footnote 4

Research design

We fielded an online survey including a vignette experiment in 14 European countries (AT, DE, DK, ES, FR, GR, HU, IE, IT, NL, PL, PT, RO, SE) in July and August 2021 using the survey firm Dynata. The sample included 19,775 respondents (approximately 1,400 respondents per country) and was collected using crossed quotas for age and gender as well as simple quotas for education and region to mirror the adult citizenry in each country.Footnote 5 The English master questionnaire was translated by translators with a background in political science. To check whether our survey instrument was easy-to-understand and clear to respondents and to identify potential problems with translations, we recruited online convenience samples of 20 respondents per country using the Prolific platform.Footnote 6

We selected this diverse country sample to ensure that we identify average treatment effects (ATEs) across a variety of European contexts with minimal bias. First, respondents’ experience with real-world challenger parties may influence their responses. The selected countries vary in their experience with new and challenger parties and whether they tend to come from the left, right, or both sides of the political spectrum. Second, voters may perceive party responses differently depending on the institutional roles parties play. Our countries vary with respect to the role of the party family in government and parliament (e.g., the party family of coalition partners and the prime minister or president), yielding scenarios in which respondents support parties with different roles in the political system.Footnote 7 Third, countries also cover both Western and Central and Eastern Europe, which provides variation in the levels and stability of democracy across the sample and allows us to examine differences across European experiences of party competition. Fourth, electoral timing may influence how voters view party responses. The timing of fielding the survey vis-a-vis national elections gives us cases where national elections just happened prior in the same year (PT), happened shortly after (DE), were scheduled in the year prior (GR, IE, PL, RO), or were scheduled the year after (AT, DK, FR, IT, HU, PT, SE).

At the beginning of the survey, respondents were asked for the current party in their political system they would be most likely to support if an election were held tomorrow. Respondents could select from a long list of parties competing in national elections in their countries. We conceptualized these existing parties as established parties, irrespective of whether they were particularly successful in previous elections. We included parties with at least one percent of support in recent polls and parties that competed on regionalist platforms in national elections, such as Junts per Catalunya or Inuit Ataqatigiit in Greenland. More specifically, we asked respondents, ‘Please rank from top to bottom the three parties you support the most, with the party you support most on top’.Footnote 8

We next elicit respondents’ preferences on four different issues that the new party makes a policy proposal on: voting rights of immigrants, climate policy, multinational taxation, and health policy during a pandemic.Footnote 9 We use several issues instead of a single prominent one (e.g., one from the area of immigration only). This is again motivated by our interest in identifying ATEs across contexts. Our selection of issues was carefully guided by both theoretical and empirical considerations. Following the theoretical argument of De Vries and Hobolt (Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020), we sought policy areas in which a new political party might enter the political landscape advocating for an extreme position. In short, we aimed to find new wedge issues. Using issues that have already received significant attention in the political arena would run contrary to the notion that challenger parties seek to compete on new, potentially divisive issues. We, therefore, chose issues that are (largely) unrelated to the primary left-right economic dimension of party competition, that would be reasonably new across a large number of countries, and that have not received significant attention or already been politicized by challenger parties across Europe.

In addition to raising theoretical concerns, using issues that existing challenger parties have already successfully used would bring with it a number of empirical problems. We would run the risk of simply selecting ‘successful’ issues – from the point of view of the challengers – to which established parties have no good response, leading to downwardly biased estimates of supporters’ views of strategies. We also worry that using issues that existing challenger parties have successfully campaigned on will lead respondents to think of precisely these parties. So far as possible, we would like our hypothetical challenger parties to remain hypothetical in the eyes of the survey respondents. Otherwise, respondents’ views of strategies may partially reflect their ideas about which parties and politicians they think might be most likely to advocate for these policy proposals in their countries. These considerations explain, for example, why we chose immigrants’ voting rights and not other more common issues surrounding immigration, and why we do not ask about European integration. These are both some of the most salient and successful challenger party issues across Europe and would immediately prime respondents to think of certain parties and politicians, precisely what we would like to avoid.

Finally, in choosing our policies, we tried to achieve some variation in issue salience. Issues surrounding immigrants and immigration have been highly salient during our field period, as were health and freedom during the pandemic. Taxation of multinational tech companies is of much lower salience, while climate issues are somewhere in between, although probably closer to the high-salience issues.

On voting rights for immigrants, we ask whether respondents agree with the statement that foreigners living in the country should be allowed to vote in any election in that country or whether they agree with the alternative statement that foreigners should not be allowed to vote in any election. We refer to this issue as the immigrants’ voting rights issue. On climate policy, respondents choose between the statements that measures to combat climate change should be stopped immediately or that measures should be taken so that the country becomes climate neutral as early as 2025. With regard to tech companies, respondents are asked to choose between the statement that large internet companies should not have to pay any taxes in the EU and a statement that in order to be allowed to continue offering their services in the EU, large internet companies should have to pay an additional digital tax. Finally, on health and freedom during a pandemic, we present respondents with a choice between whether people’s fundamental rights should never be restricted in a pandemic, not even to protect people’s health, or whether people’s fundamental rights should always be restricted to protect people’s health. Because the survey was fielded in summer 2021, this was a new and salient issue that had not yet been taken up by new parties, making it the ideal issue for our survey. In fact, new parties, namely the MFG party in Austria, would become nationally known on the basis of this issue, but only after the conclusion of our fieldwork. In addition to choosing the first or second alternative, respondents could also indicate that they do not agree with either statement or ‘do not know’.

Respondents then participate in the vignette experiment, which we introduce as follows: ‘We would now like to show you four hypothetical situations in which a new party would like to run in the next election to the [National Parliament]. Even though the four situations may seem similar, we ask you to evaluate the situations independently of each other’.

Each vignette follows the same format. First, the respondent is told that the new party wishes to participate in the next national parliamentary election. Then the new party makes an attack statement. This statement is randomly chosen from a set of possible attacks, some of which specifically attack the established elites, who are said to act against the ‘people’s’ wishes – our populist attack treatment – and some of which are focused specifically on attacking the government. Thus, we account for the fact that some new parties are decidedly populist while others are not (i.e., only anti-government), and the idea that populist attacks may be more effective or suggest different responses by established parties (e.g., Bale et al. Reference Bale, Green-Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010; De Vries and Hobolt Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020). Again, including both types of attacks is thought to reduce bias in identifying ATEs across contexts.

After the attack, the vignette then states the policy demand of the new party using one of the statements on the four policy issues. In line with the issue entrepreneur literature (De Vries and Hobolt Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020), we assume that new parties primarily politicize a single issue, and thus, we do not characterize the party on multiple issues. We also abstain from assigning an ideological label to the new party because many emerging parties (initially) reject traditional left-right classifications to maintain broad appeal (e.g., the Italian Five Star Movement and German Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht). In fact, ideological labels are typically assigned later by observers based on the very policy positions the party advocates, making the separation artificial for new political entrants whose ideological identity is still in flux.

Finally, respondents are asked to consider a hypothetical response of their preferred party. We use the term ‘response’ instead of ‘strategy’ to describe the reaction of the existing party since our respondents cannot directly tell from our vignette whether the party’s behavior is purposefully planned and orchestrated or the result of unplanned, decentralized decisions. This mirrors voters’ true experiences with party responses. They may receive information on how a party reacts, but it is often unclear to them how much strategy underlies the response. The existing party’s response was drawn randomly from six possibilities: a unified accommodative stance, a unified adversarial stance, an ignoring response, and three divided responses where two parts of the party respond differently. These three divided reactions are accommodative-adversarial, accommodative-ignoring, and adversarial-ignoring.Footnote 10

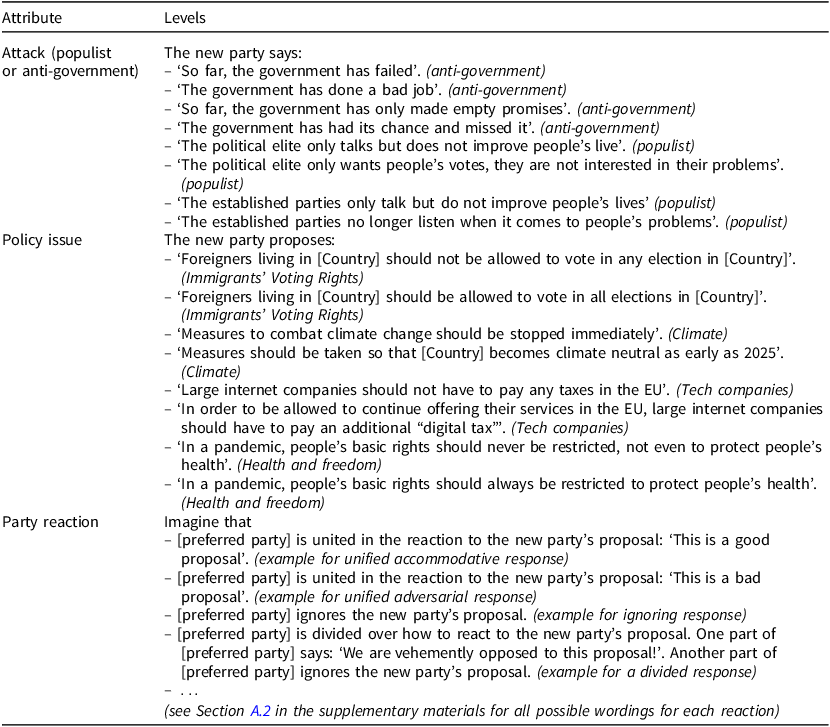

The screenshot in Figure 1 shows one example of a vignette from Ireland. The party ‘the Greens’ is mentioned because the respondent who saw this particular version of the vignette said that they supported the Greens. Table 1 shows all of the attributes and their attribute levels, as well as a selection of different statements for the levels. For each attribute level, we use a number of different statements that express the same treatment concept in different words. This approach guards against idiosyncratic language effects, especially considering our cross-national sample. We are therefore also confident that our results do not hinge on arbitrary choices regarding wording (see Blumenau and Lauderdale Reference Blumenau and Lauderdale2022; Fong and Grimmer Reference Fong and Grimmer2023).

Figure 1. Example of what an Irish supporter of the Greens could have seen when responding to the first out of four vignettes.

Table 1. Attribute levels of vignette experiment

The number of statements for several attribute levels (including populist vs anti-government and party reactions) varies slightly across countries whenever translators suggested that there were fewer or more options to express a treatment (e.g., how to talk about a united party). As these deviations were very minor overall, we draw the vignette realization for each attribute from a uniform distribution of all text implementations.Footnote 11 While the values for the attributes on populism and party reactions are completely randomized, each respondent sees four vignettes, one for each policy area (immigrants’ voting rights, climate change, multinational corporation taxes, and health policy during the pandemic). We randomize the order in which respondents see the policy areas and the direction of the extreme statement for each policy area.

We measure the respondents’ evaluation of their preferred party’s response below each vignette by asking how much the respondent personally likes the described response on a seven-point like-dislike scale. We identify the effect of the different party responses by estimating marginal means for each of the party responses while marginalizing over the levels of other attributes.Footnote 12 To do so, responses must remain stable across different vignettes (‘no carry-over effects’), and the levels of attributes must be fully randomized (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014).Footnote 13 We also ask respondents (half before, half after) how close they feel to their preferred party. In total, we collected 79,034 vignette-respondent observations from the 19,775 respondents.Footnote 14

Results

Policy divisions among party supporters

Before we present our main, experimental findings, we first show how party supporters view each policy proposal – pre-treatment and outside the experimental setting. These descriptive statistics help us to understand how party supporters’ policy preferences might affect their evaluations of their preferred party’s responses. To aid visualization, we group party supporters into supporters of different party families. Figure 2 shows that supporters of parties belonging to the same party family do not necessarily share one position towards the proposals. While division among supporters is large regarding the trade-off between freedom and people’s health and regarding immigrants’ voting rights, division is smaller regarding the issues of climate change measures and taxes for tech companies.

Figure 2. Respondents’ stated position by policy area and family of preferred party.

Immigrants’ voting rights prove to be the most contentious issue. Among supporters of left-wing parties, we find that 42% of Green Party supporters and 38% of Social Democratic Party supporters believe that immigrants should be allowed to vote in all elections in the respondents’ home country. But 27% of Green Party supporters and 23% of Social Democratic Party supporters chose neither of the extreme statements. An additional 20% of Green supporters as well as 29% of Social Democratic Party supporters believe that foreigners should not be allowed to vote in any national election. Among supporters of right-wing parties, 56% of the supporters of the far right believe that foreigners should not be allowed to vote in any national election. Surprisingly, 19% of far-right party supporters believe that foreigners should be allowed to vote in all national elections, and 16% chose neither of the extreme statements.Footnote 15

These numbers indicate that supporters of more left-wing parties tend to favor extending rights to foreigners, while supporters of more right-wing parties are against this. However, they also show that party supporters are far from homogeneous. Division among supporters of a party family is not driven by differences between the supporters of different parties in the same party family (e.g., social-democratic supporters in Sweden vs. Germany). Rather, we find substantial amounts of preference division even within individual parties,Footnote 16 which enables us to assess whether respondents’ desire for their party to respond to a new party in a particular way leads to difficult situations for party leaders in which it becomes impossible to please large segments of their party base.

Unified and divided party responses

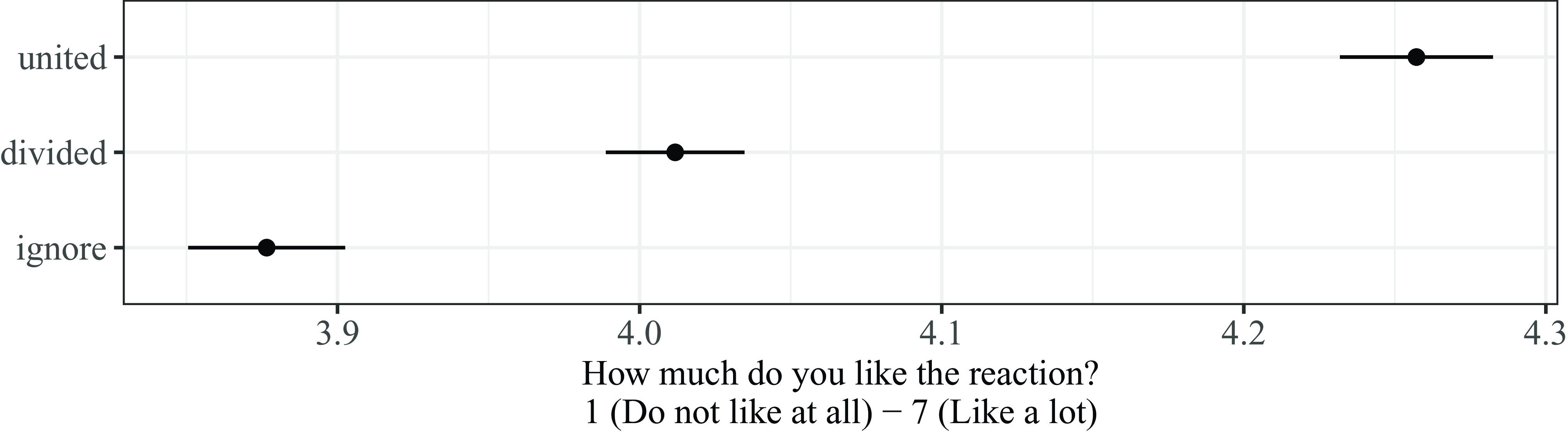

We now turn to our test of H1. Established parties’ responses to a newcomer can be united (accommodative or adversarial), divided (accommodative combined with ignore or adversarial combined with ignore, or, arguably the strongest division, adversarial combined with accommodative), or ignore, where the entire party ignores the new party. We evaluate the appeal of united vs divided responses, on average. We pool accommodative and adversarial responses under ‘united’, while we pool any form of intra-party division in the response under the label ‘divided’. Figure 3 presents marginal means for whether respondents like the reaction of their preferred party more if the party responded to the new party in a united manner, a divided manner, or simply ignored them.Footnote 17

Figure 3. Marginal means for how citizens want their most preferred party to respond to new parties.

The results offer strong support of the notion that, independent of the substantive policy position, voters on average clearly prefer a united reaction.Footnote 18 However, our results show that an openly divided party response finds higher support than a response in which the party ignores the new party’s proposal altogether. In some situations, when unity is not possible, it may actually be preferable for established parties to allow for intra-party dissent in the hope of retaining support of their electorate.

Supporters’ policy and response preferences

We now turn to our test of H2. We know whether respondents were confronted with new parties whose proposals they liked, disliked, or did not have a position towards, because we elicited each respondent’s policy preferences before the vignette experiment. Figure 4 visualizes party supporters’ preferences for specific party responses to the new party contingent on their policy preferences.Footnote 19 For each of the six possible responses, we display the marginal means for respondents who (a) share the same extreme position as the new party, (b) neither share the position nor have the opposite stance, (c) have the opposite extreme position as the new party, and (d) do not know.

Figure 4. Marginal means for how citizens want their most preferred party to respond to new parties depending on whether they agree with the proposal of the new party.

If respondents agree with the new party’s proposal, then respondents, unsurprisingly, strongly prefer a united accommodative response from their preferred party. This is followed by responses that at least partially accommodate the new party. Interestingly, respondents prefer that their party engage in two conflicting strategies, rather than simply ignoring the new party. The opposite pattern is visible for respondents who disagree with the new party’s demand. Respondents prefer that the party they support be unified in its adversarial response to the newcomer. Their second most preferred options are responses that are at least partially adversarial or ignore the upstart’s demand. Party reactions that contain any form of accommodation are least preferred. In situations where respondents do not share the extreme stance of the new party nor adopt the opposite extreme stance, the results point towards a preference for a united adversarial response over accommodation, ignoring, or combinations thereof. When a respondent does not care much about the issue (does not give a position on the issue), the respondents prefer an adversarial response over all other responses.Footnote 20 Overall, these results also re-confirm H1 that respondents prefer parties pursuing a unified response over a display of divided reactions.

Divided electorates and best responses

Clearly, issues arise for the party when party supporters are divided regarding their position towards the new party’s proposal. If party supporters are fiercely divided, one half will prefer an accommodative response, while the other half will prefer an adversarial response. Our survey design allows us to calculate an established party’s best response to a new party depending on the degree of division among its voters.

To do so, we first compute an issue-specific’ division score that describes disunity among a party’s electorate on a scale from 0 (fully united) to 1 (fully divided) as the relative share of respondents with a given policy preference. We define disunity within a party’s electorate as the ratio between the percentages of respondents supporting each of the two extreme positions, calculated separately for each issue area. For example, if 25 percent of respondents supported one of the extreme statements and 50 percent the other extreme statement, we divided 0.25 by 0.5, resulting in a division score of 0.5. If exactly half of the supporters of an established party hold each of the opposing policy positions (e.g., half of the supporters prefer no restrictions on immigration and half of them prefer restrictions), we end up with a division score of 1. If all supporters prefer one of the policy positions, the party supporters are united; we end up with a division score of 0.Footnote 21

We then distinguish between parties with electorates that are divided or united on a specific issue area. We use 0.5 as a threshold. For united party electorates, we also assess whether the electorate is in favor of the policy proposal put forward by the new party or whether the electorate is overwhelmingly against this proposal. Hence, we have three different types of party electorates in our data: divided ones, united ones that are in favor of the policy proposal discussed in the vignette, and united ones that are against the policy proposal. Within these three groups, we estimate the mean approval rate for each type of party response by linearly regressing the party response on the approval rate. We also run separate regressions for the different party families and for the different policy proposals.

The best response for an established party facing a specific new party should be the one with the highest marginal support among a party’s support base – assuming that it is the established party’s goal to keep this support base. We visualize the marginal support for the different responses among party supporters of Christian democratic, conservative, and social democratic parties in Figures 5 and 6. We focus on these party families because they are most common in the countries under study, and hence, we have a sufficient number of respondents in our sample supporting one of these parties. We subsume Christian democratic and conservative parties into one category because party systems tend to feature either a Christian democratic or a conservative party on the center-right. We focus on responses to new parties proposing policies regarding the voting rights of immigrants and potential restrictions of freedom during pandemics since these are the issues where voters of Christian democratic/conservative and social democratic parties are most divided (see Figure 2).Footnote 22

Figure 5. Support for the party reaction of Christian democratic and conservative parties when faced with new parties proposing measures concerning the voting rights of immigrants or basic rights in times of pandemics, averaging across new parties’ attacks. Notes: See Table A.8 in the supplementary materials for the number of cases in each cell. We are hesitant to discuss findings for respondents of united electorates against restrictions on freedom and for united electorates rejecting policies for restrictions on freedom in times of pandemics due to the low number of observations.

Figure 6. Support for the party reaction of social democratic parties when faced with new parties proposing measures concerning the voting rights of immigrants or basic rights in times of pandemics, averaging across new parties’ attacks. Notes: See Table A.8 in the supplementary materials for the number of cases in each cell. We are hesitant to discuss findings for respondents of united electorates against restrictions on freedom and for united electorates rejecting policies for restrictions on freedom in times of pandemics due to the low number of observations.

Best responses are clearly detectable when electorates are united on the issue in question (see the two upper rows in both Figures 5 and 6). This neatly fits the results described above: parties with united electorates can please their electorate by choosing an accommodative response when their electorate is unified in their support for the proposal of the new party or an adversarial response if it is unified in their rejection of the proposal.

However, such best responses are less clearly detectable when electorates are divided on the issue in question (see the lower row in Figures 5 and 6). For proposals on basic rights in pandemics, most responses receive equal average approval ratings among divided electorates. For conservative and Christian democratic parties with divided electorates, there is clearly no best response when facing new parties that want to restrict voting rights of immigrants, either. Likewise, there is no best response to new parties proposing expansions of voting rights for social democratic parties with divided electorates.

Nonetheless, even divided electorates sometimes seem to have a preference for one specific response over all others; on average, social democratic parties with divided electorates fare best if they fight new parties proposing the restriction of voting rights, and conservative and Christian democratic parties with divided electorates fare best when fighting new parties proposing expansions of voting rights for immigrants.Footnote 23

Subgroup and attack type effects

Subgroup effects

In addition to the main results, we test whether our results hold across different subgroups of respondents. We show the results for differences across countries and regions here and refer to the supplementary materials for other subgroups.Footnote 24 These include the family of the respondent’s preferred party, the governing status of this party, how united or divided respondents perceive their preferred parties to be before the experiment, the strength of respondents’ identification with their preferred party, whether the strength of party identification was elicited before or after the experiment, whether respondents take a position on the issue or not, the salience of issues in each country, respondents’ populist attitudes, and finally, the respondents’ gender. Our results hold for the overwhelming number of subgroups.

To test whether respondents from different countries react differently to our experimental stimuli, we first investigate preferences for united, divided, or ignoring strategies within each country under study. Respondents’ evaluations by country are shown in Figure 7.Footnote 25 The result that a unified response is preferred over a divided response, which is preferred over an ignoring response, holds across countries, albeit with some nuances. While a united response is most liked almost everywhere, French respondents do not value a united response more than a divided response. And in Austria, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, and Sweden, respondents appear indifferent between a divided response and simply ignoring the newcomer.Footnote 26 These findings show experimentally that a united party response as opposed to divided or ignored responses is liked most by the party’s supporters, at least on average across a broad set of different contexts. At the same time, they also show that the advantage of cohesiveness can sometimes be very small or disappear entirely.

Figure 7. Marginal means for how citizens want their most preferred party to respond to new parties in each of the countries under study.

Differences in the history of party system development, as well as variation in the prevalence of a norm favoring party unity among the public, make it important to look at observations from different subgroups of countries: central and eastern Europe, southern Europe, and western and northern Europe. Voters from central/eastern European countries show higher support for any reaction by their parties (higher marginal means) than citizens in other regions. The treatment effects we identified before, however, do not change. Voters prefer a unified reaction over speaking with a divided voice over ignoring the new party in all three regionsFootnote 27 with the nuances described above. Moreover, our main finding – support for an accommodative vs. adversarial response as a function of policy congruence – replicates in all three regions, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Marginal means for how citizens want their most preferred party to respond to new parties depending on whether they agree with the proposal of the new party for western/northern, southern (ES, GR, IT, PT), and central/eastern Europe (HU, PL, RO) separately.

Type of attack

Lastly, we evaluate differences in marginal means across party reactions by whether the new party makes a populist or anti-government attack.Footnote 28 We again confirm that when respondents are congruent with the new party’s policy position, the average support of an accommodative response is largest; when they oppose that party’s policy position, they support the adversarial response the most. For all experimental contexts, we find that the average support for a unified response is higher than the one towards a divided response, which is higher than the one towards ignoring the new party’s challenge; for both types of attacks, populist and anti-government, voters support an accommodative response when congruent with the policy proposal of the new party and an adversarial response otherwise. It is also not the case that respondents who hold more populist attitudes are more likely to support populist attacks. Such respondents are generally less supportive of any response by their party, independent of the type of attack and party response.

Conclusion

The ability of new parties to enter the political landscape and compete with established parties is a key feature of representative democracies. Many party systems have experienced drastic changes, with some established parties collapsing and new parties getting a foot in the parliamentary door. These upstart parties seek to compete by crafting positions on issues that divide established parties, appealing to segments of their support base. How can the challenged fight back? This is a central question of party politics. Do some approaches resonate more with the supporters of established parties than others? How does the evaluation of a response depend on the policy preferences of those supporters? And how does the ideological leaning of the established party matter?

We have developed a survey experiment fielded in 14 European countries to answer these fundamental questions. We find that while voters, on average, prefer it when the party they support engages in a united response, there is significant variation arising from policy preferences of respondents with respect to the issue that the new party raises. Depending on the distribution of policy preferences among established supporters, there may be no optimal strategy for a party to pursue. Our results highlight that while parties have dominant strategies when their supporters hold uniform views on the major issue that the newcomer politicizes, their choice of strategy becomes less consequential if their base is divided.

This finding contributes to our understanding of why some party families are quite varied in their reaction to new and challenger parties as well as why some members of a party family sometimes choose supposedly counter-intuitive, idiosyncratic responses (e.g., Danish social democrats to an anti-immigration challenger). On the one hand, parties’ responses on wedge issues may be more driven by other factors than concerns about entertaining their voter base (e.g., office-seeking or policy-seeking motives) – especially if a clear best strategy is missing. This may also render them more idiosyncratic. On the other hand, wedge issues are those that new parties will most likely politicize, precisely because there may be no ‘good’ responses for established parties. Challenges to which a good response exists may never be mounted.

Like all research, our study faces some important limitations. First, we focus on supporters of existing parties and the strategies that they like most. We cannot assess to what extent different strategies may be able to draw support from other parties or from real abstainers. While this may be a secondary concern for parties, as it might typically be easier to keep voters than to mobilize new ones, it may nevertheless affect the choice between strategies, especially if the effects of two strategies on a party’s base are similar (see also e.g., De Sio and Weber Reference De Sio and Weber2014). Future work could investigate how the different reactions of established parties are (dis)liked by voters of other parties or non-voters, whether they may make these groups consider changing their allegiance, how the responses of multiple different established parties potentially interact in their effect on voter preferences, and what effects arise long-term since voters observe several responses from their party over time. This would provide a fuller picture of how parties’ interactions with new parties influence citizens’ views of them.

Second, although we have fielded our survey experiment across a wide range of contexts, we are not able to vary all relevant contextual factors. We have tried to experimentally vary many key factors – e.g., the nature of the rhetorical attack, the nature of the issue, and established parties’ responses. However, our design does not characterize the new party by anything more than its stance on a single issue and an attack statement on the government. Likewise, it does not consider reactions of other parties than the respondent’s party. Moreover, some other contextual factors we account for observationally we cannot randomize in the experiment. We cannot vary which party an individual supports, the country or party system in which the competition takes place, or whether a supporter’s party participates in government, for example. These contextual factors may influence effects, and future work should try to incorporate even more of them (e.g., characterize the new party on more issues). At least, the remarkable stability of our core results across the wide range of countries and scenarios that our design covers provides confidence that our experimental findings may travel across various contexts.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676525100625.

Data availability statement

Replication files are available in the Harvard Dataverse (https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse).

Acknowledgements

The authors are listed in alphabetical order. We thank David Fortunato, Sara Hobolt, Indridi Indridason, Federica Izzo, Ann-Kristin Kölln, Christina Schneider, and participants at the Zurich IPZ publications seminar, the University of Gothenburg’s Party Research Seminar, the Mittagsforum research seminar at the University of Duisburg-Essen, and the 2023 Southern California Political Institutions and Political Economy Conference at UC Riverside for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this work.

Funding statement

This research was funded by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation as part of the project on ‘Rebels in Representative Democracy: The Appeal and Consequences of Political Defection in Europe’. Sven-Oliver Proksch also acknowledges support funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy – EXC 2126/1– 390838866.

Competing interests

Authors do not report on any conflict of interest arising from the research.