Introduction: The Topos of the Drink-bearing Woman

The Franks Casket is a small (nine-inch-long) box made from the bone of a whale in the early eighth century, probably in Northumbria. It is carved on all four sides and the lid with images and runic inscriptions and labels that comment upon them (Fig. 1).Footnote 1 The right-hand side panel of the casket shows three scenes marked off by figures with their backs turned. In the central scene, the realistic image of a horse with triple-looped triquetae between its legs faces a human figure with a goblet; this assemblage is the subject of our essay (see Fig. 2). The casket’s distinctive double image of a triquetra-marked horse facing a drink-bearer is found again on two of the memorial picture stones on the Swedish island of Gotland in the Baltic – and nowhere else. The similarity of these iconographies has been mentioned in passing since 1930,Footnote 2 with no attention to how interesting their uniqueness is. We offer a more comprehensive study providing a context for these similar but geographically distant two-figure images, with particular attention to the meaning of the triquetra-marked horse. The use of horses in archaeologically attested mortuary rituals is brought to a discussion of the Franks Casket scene for the first time.

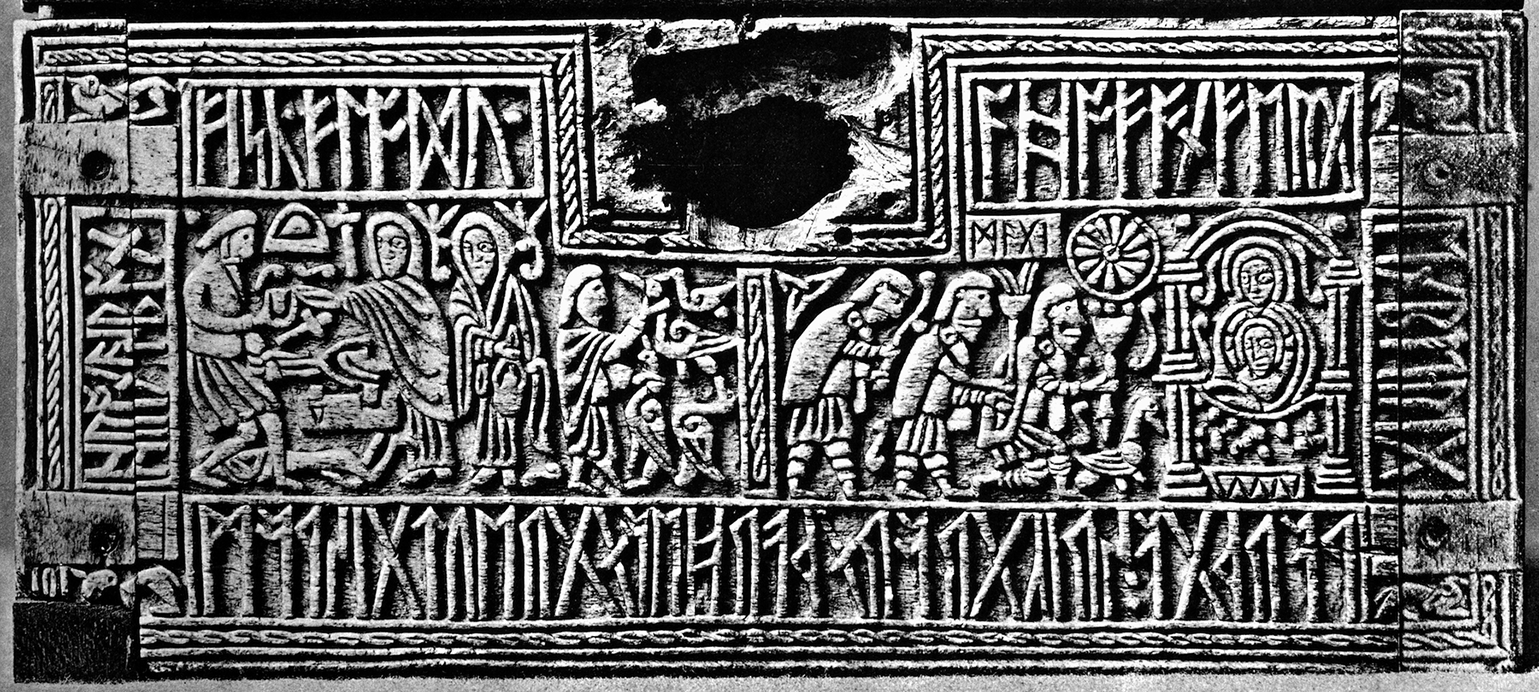

Figure 1. The front panel of the Franks Casket illustrating two stories and framed by a poem in runes. The hole is where the lock was situated. Photo from W. Viëtor, The Anglo-Saxon Runic Casket (the Franks Casket): Five Phototyped Plates with Explanatory Text (Marburg in Hessen, 1901). (Permission: in the Public Domain). The British Museum offers images of the casket that may be manipulated for a close-up view, freely available at this museum link: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1867-0120-1.

Martin Foys’ digital edition of the Franks Casket, containing a wealth of linguistic and interpretive information in addition to photographs of each panel, may be accessed at https://uw.digitalmappa.org/

Figure 2. The Right-Hand Side Panel of the Franks Casket. The original panel is in the Bargello Museum in Florence; the panel on the casket in the British Museum is a replica, though the museum possesses the broken off right end. Photo: W. Viëtor, The Anglo -Saxon Runic Casket. (Permission: in the Public Domain).

The gender of the casket’s drink-bearing figure is crucial to identifying the Northumbrian and Gotlandic scenes as illustrating variants on a widely practiced mortuary ritual, or the idea behind such a ritual variably practised. This figure may be associated with the familiar woman bearing a drinking horn found on Scandinavian stone carvings and as innumerable metal figurines meant to be worn,Footnote 3 in Old English poetry including Beowulf, where the lady bears a mead cup, and in later Old Norse poetry (see addendum). Whether standing alone or in the double figure of drink-bearer and horse, the Scandinavian horn-bearer, often referred to as a ‘valkyrie’ (valkyria) in Old Norse scholarship, is so consistently portrayed as female that we feel justified in assigning that gender to the casket’s ambiguously clothed figure that stands in the same relation to a horse as the horn-bearer in the Scandinavian double-figure scenes. The grave mound between the drink-bearer and the horse on the Franks Casket marks that scene as mortuary. (More about that grave below.)

The figure of a drink-bearer on the tenth-century stone cross in Gosforth in northern England illustrates how highly adaptable this female figure is. The Gosforth Cross is unusual in many ways. It is on a slim fifteen-foot shaft and bears a relationship to the Irish high crosses (such as that at Muiredach), except that those crosses are carved with Christian scenes, whereas the four sides of the Gosforth shaft contain scenes from Norse myth. These have been interpreted as Thor’s fishing trip, Loki bound with Sigyn giving him aid, Heimdal holding his horn, and Thor’s son Vidar tearing apart the jaws of the wolf Fenrir (Fig. 3). At the bottom of the Vidar side are two small panels, one above the other, containing the only Christian images on this Viking Age cross. Appropriately, they represent the stylized scene of a crucifixion, which is what the Christian cross stands for. On certain Irish high crosses (like that at Muiredach), the image of crucified Christ is flanked by Longinus stabbing Christ with his spear and Stephaton offering Christ a drink with a sponge on a spear, as is traditional (see Matthew 27: 48; Mark 15: 36; cp. John 19: 29). While abiding by these themes, the scene on the Gosforth cross takes a peculiar turn. The top panel contains a man with arms outstretched like crucified Christ but without the cross, similar to the scenes on Irish high crosses. In the bottom panel Longinus stands on the left, as usual, with his spear reaching up between panels toward Christ, but on the right, holding out a drinking horn, is the Scandinavian figure of a woman with her iconic twisted hair and trailing dress, like the small metal figurines found mainly in Sweden. The figurine in Fig. 4 is the most frequently reproduced of these metal horn-bearer images, looking very similar to the Gosforth Cross figure. The main point to be emphasized is that even when standing in place of the Roman soldier on a Viking Age cross in northern England, the traditional Scandinavian horn-bearer retains her female gender.Footnote 4 If she also retains her ritual role in mortuary performance, while offering Christ the drink recorded in the Gospels, she may be easing his transition to another realm.

Figure 3. The Gosforth Cross, illustrated by W. G. Collingwood, Northumbrian Crosses of the Pre-Norman Age (London, 1927), p. 156. In the public domain. Available at https://wellcomecollection.org/works/f45r7vf7/items?canvas=168&query=gosforth. The line-drawing of the crucifixion scene is by Melissa X. Stevens. (Used by permission from Melissa X. Stevens.)

Figure 4. Silver-Gilt Figurine from Klinta, Köping Parish, Öland, Sweden. Photo by Gabriel Hildebrand at the Swedish History Museum, 108864_HST, 2011. (Permissions: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License CC BY 4.0.)

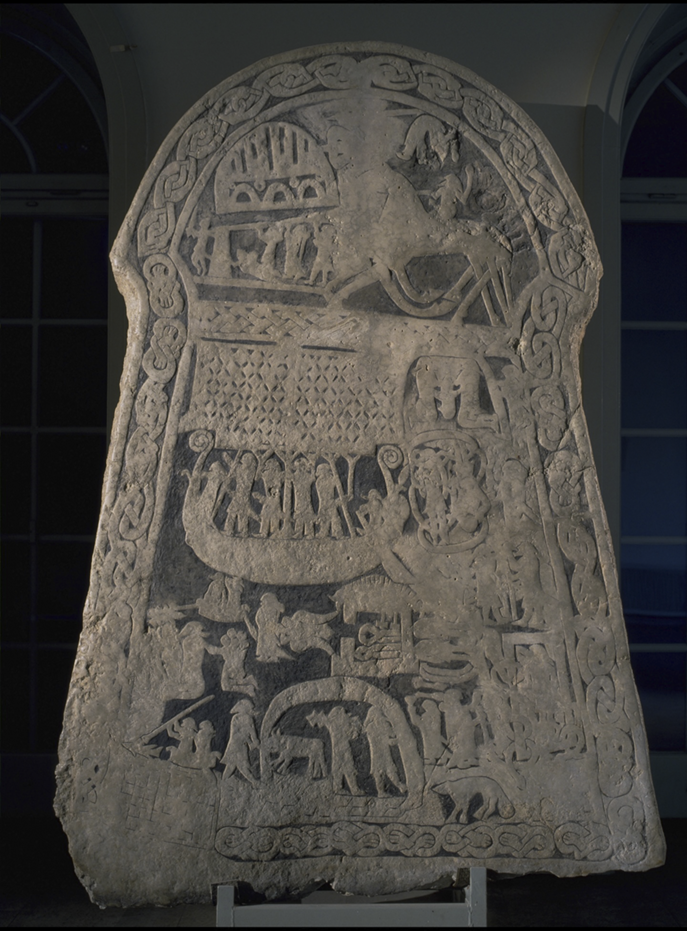

The horn-bearing woman facing a horse in the Gotlandic double-figure scenes such as that on the Tjängvide stone (see Fig. 5) is commonly understood to be welcoming a rider as he enters the other world on a horse associated with Odin – on ‘Sleipnir, the horse sliding between the realms’, says Neil Price, etymologizing the name.Footnote 5 The horse in Fig. 5 has been identified as Odin’s horse Sleipnir on the basis of its eight legs. While the scene on the Franks Casket encourages comparison due to the similar arrangement of the horse and drink-bearer, differences include the casket’s horse without a rider (a potential rider waits inside a mound), the drink-bearer’s genderless garment, and the representation of the drink by a goblet that seems to float in midair (it is at raised hand height with perhaps a hand on the goblet’s stem). The single indisputable detail that links this early eighth-century Northumbrian scene to Gotland is the device of triple knots (triquetra) between the horse’s legs. This triquetra feature is immensely intriguing because it is found in connection with a horse facing a drink-bearer only on the Franks Casket and two Gotlandic picture stones, that designated Lärbro Tängelgårda and the slightly later Alskog Tjängvide stone of Fig. 5; this type of narrative picture-stone is considered unique to Gotland.Footnote 6 The occurrence of those oddly placed triquetrae within a double-figure scene only at these two locations demands that we look across the distance to consider what the attested mortuary contexts of the Gotland stones might bring to a reading of the scene on the Northumbrian box.Footnote 7

Figure 5. Woman Horn-bearer and Eight-Legged Horse with Triquetrae, Detail from the Tjängvide I Picture Stone, Gotland, Sweden. Photo by Christer Åhlin at the Swedish History Museum, 108203_HST, 1999. (Permissions: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License CC BY 4.0.)

Before proceeding to that broader context, however, the reader needs to know more about the context of the drink-bearer scene as it appears on the Franks Casket. The densely carved casket is a highly literate artifact with inscriptions in runes (some coded) and allusions to Latin texts as well as to stories from the Germanic world. It is unlike any other small box found anywhere.

Interlocking Themes and Mirroring Stories on the Franks CasketFootnote 8

The double-figure scene of horse and drink-bearer occurs on the casket as part of a programme of narrative images with interlocking themes that cross between pictures. The inscriptions accompanying these images are mostly in runes, in a Northumbrian dialect of Old English that suggests a date in the first half of the eighth century, the ‘Age of Bede’.Footnote 9 The images illustrate six stories, four of which are clearly recognizable. The Vengeance of Weland and the Adoration of the Magi are framed together on the front (see Fig. 1), the She-wolf nurturing Romulus and Remus appears on the left side, and Titus retaking Jerusalem is shown on the back. Of the remaining two panels, the illustration on the lid lacks sufficient information to be securely identified, and the coded runes in the inscription surrounding the three scenes on the horse-dominated right side indicate intentional obscurity, a riddle to be solved by the casket’s reader. The decorative frame made by the runic inscription indicates that these three scenes are to be understood together. What the runes in the frame say will be examined later.

Leslie Webster argues convincingly that the pictures on the casket’s five panels are ‘meant to be read in pairs, something hinted at by the twinned scenes facing each other on the front panel’,Footnote 10 and she explains how those two scenes on the front, although clearly opposed in narrative content, may be read across the boundary line that separates them as thematically linked. Enough of each story is shown to evoke the rest of the story in the viewer’s memory. (Illustrations typically serve as a trigger, a sort of lieu de mémoire, to evoke or reinforce a fuller narrative.)Footnote 11 The mirroring of stories on this front panel is especially elaborate with allusions to what is not seen. In the Weland story, King Nidhad (not shown) has captured, mutilated and imprisoned the smith on an island and ordered him to make treasures for the royal coffers. Weland maliciously responds to the king’s demand with the grim ‘treasures’ that he makes. The illustration shows the hamstrung Weland at his forge, under which lies the beheaded naked body of the king’s son. The smith has made a cup or ‘treasure’ from the boy’s skull, and he holds out this cup toward the king’s virgin daughter (named Beaduhild in the Old English poem Deor, Bǫðvildr in Old Norse); she is unaware of the body. The cup contains a drink that will render the princess helpless so that Weland can rape and impregnate her. Then he will manufacture a magical flying machine, presumably from the wings of the geese being captured within a smaller frame, and escape by flight from King Nidhad’s anticipated rage.Footnote 12 Juxtaposed to the magical smith’s vengeance on the left side of the panel, the scene on the right side shows the familiar ‘Adoration of the Magi’, with the wise men advancing toward the Christ Child and Virgin with gifts of gold, incense and myrrh. Above the bearer of the myrrh, a plant that symbolizes death,Footnote 13 is a triquetra like that between the horse’s legs on the right-side panel.Footnote 14 Leading the procession is a confident goose. James Lang suggests that the bird, perhaps having escaped Weland’s murderous goose-strangling, serves as a leitmotif ‘leading the eye onwards’ to ‘imply a connection between adjacent scenes’.Footnote 15 These thematic connections, crossing between the panels in a move that Webster calls contrapuntal,Footnote 16 can be expected to emerge in the mind of the anticipated viewer who knows these culturally shared stories. When the Magi do not return to tell King Herod the location of the future King of the Jews whom they have prophesied, he furiously orders the ‘Massacre of the Innocents’ (Matthew 2: 16–18). As Sigmund Oehrl has demonstrated in detail, on the Franks Casket this act echoes Weland’s murder of King Nidhad’s sons.Footnote 17 The Christ Child escapes angry Herod’s murder because an angel has warned the holy family to flee, and their escape, though on foot (Matthew 2: 13), echoes Weland’s escape on wings from Nidhad’s wrath.

Counterpoint themes similarly cross between the casket’s other four panels, although with less complexity than those on the front. In contrast to the urban scenes of cities besieged on the lid and conquered on the back,Footnote 18 the scenes on the two sides show ‘wild and dangerous natural places in which animals figure prominently’.Footnote 19 On the left side of the casket a wolf lies in her thicket-den, and on the right side a horse comes through a wood. The pairing of these scenes on the two side panels is especially pertinent to what follows.

The ‘wolf’ scene on the casket’s left side illustrates the discovery of the abandoned twins Romulus and Remus safe in the She-wolf’s leafy den, with a second wolf lingering nearby in the foliage; each wolf licks one of the twins. The direct source of this scene has been identified as Virgil’s description of the (imagined) picture of the Romulus and Remus story on the shield of Aeneas in the Aeneid, where the She-wolf of Rome, in her ‘green cave’ (viridi antro, Aeneid 8: 630), ‘shapes’ the two boys by licking each in turn (Aeneid 8: 634). The casket designer has introduced the second wolf in order to have both boys licked within the single scene.Footnote 20 The runic inscription framing this scene, transliterated here, is a straightforward titulus: ‘Romwalus and Reumwalus twœgen gibroþær: afœddæ hiæ wylif in Romæ cæstri, oþlæ unneg’ (‘Romulus and Remus, two brothers: a She-wolf nurtured them in Rome City, far from their native land’; author’s translation). This scene, making visible Virgil’s imaginary ekphrasis, was composed for a reader assumed to be familiar with the Aeneid.

In contrast to the clarity of this scene and its inscription, the picture panel on the casket’s right side is rife with intentional ambiguities and clever but challenging devices of various kinds, demanding a kind of attention different from that given to the plainly presented She-wolf story.Footnote 21 None of the many meanings proposed for this side has been universally accepted,Footnote 22 nor is it this essay’s purpose to solve the panel’s riddle. The goal here is to call attention to the similarity of the double-figure scenes on the Franks Casket and the Swedish picture stones and to set in motion what that means and how it can inform our understanding of these objects. To that end a description of this panel more detailed than that above now follows. At the left side of this panel, a hybrid horse-human figure, seated on a mound and holding crossed boughs with human hands, faces a standing warrior. The hybrid figure, muzzled by a snake that may be speaking, has been identified by George Henderson as a seer.Footnote 23 Margaret Clunies Ross focuses on the crossed boughs to identify this figure as a judge in the ‘Osiris pose’, a pose associated with judgment elsewhere in medieval insular art.Footnote 24 The muzzling serpent suggests that the source of judgment may be otherworldly, chthonic. In the panel’s centre scene, a striking horse accompanied by a bird, probably a raven, appears to be emerging from a grove labelled risci-wudu; this word may be a unique compound created for the occasion like the words fergenberig on the front panel and harmberga in the inscription on this right-hand side. Whatever might be the exact meaning of the word risci, the location of that label above the horse and the label wudu below it suggests that the animal is penetrating this forest barrier, a limen or threshold between worlds. The triquetrae between the horse’s legs seem specifically to signal liminality, a ‘betwixt and between’ state associated with death or dying when the same symbol appears both with the horse and above the myrrh-bearing Magus on the front panel, and perhaps indicating a paranormal aspect of the figure inside the building (a shrine?) on the lid.Footnote 25 Above the staff and goblet held by the figure facing the horse is the label bita, arguably referring to the mordant or biting quality of both objects.Footnote 26 The staff may indicate the bearer’s office as a ritual specialist,Footnote 27 with the cup signifying a ritual involving a specific kind of drink. The horse is looking down at a mound directly beneath the goblet, so this is a mortuary ritual. That barren mound, containing a figure perhaps wrapped in a shroud, is thematically in contrast to the ‘green den’ of the life-giving She-wolf on the opposite side of the casket, and it is called a sarden, a ‘painful den’, in the inscription. The casket designer leaves no doubt about the nature of the mound because he labels it with an ‘embedded’ caption hidden in the inscription, declaring ‘here the earth-island [mound] is a grave,’ and locating the two x-shaped g runes in the section eg is græf (‘island is [a] grave’) directly under the two sides of the mound in the picture, identifying it.Footnote 28 These two x-shaped letters are easy to see at the bottom of the panel in Fig. 2.

In the separate scene at the far right, two cloaked figures appear to clutch a third between them. Observing how these figures are positioned in terms of counterpoint themes that lead the viewer from one panel to the next may help to identify the meaning of this trio. In the bottom corners of the Titus scenes on the back of the casket are runic labels contained in small boxes, dom (judgment) at bottom left and gisl (hostage) at bottom right. These labels refer respectively to the scenes of Titus in judgement at left, and the Jewish leaders of the rebellion being led into captivity, as the result of his judgement, at right. In the same left and right order on the right-side panel, the hybrid creature sitting on a mound at left with crossed boughs seems to represent dom (judgement), and the figure being clutched in the scene at right may be a gisl (hostage or captive), or a constrained participant in the mortuary ritual. The horse and drink-bearer scene stands between them, and a cryptic three-line poem in coded runes frames the three scenes together.

The Poem Surrounding the Three Scenes on the Right-side Panel

The inscription in runes surrounding these three scenes runs continuously without spacing between words (see Fig. 2), but meter and alliteration invite separation of the words to reveal a poem. In the text below, Elliott van Kirk Dobbie transcribes and arranges the runes into verse lines.Footnote 29 The translation that follows is based on that by runologist R. I. Page, with his punctuation slightly altered for clarity.Footnote 30 Page repeats Arthur S. Napier’s interpretation of the nouns ‘Hos’ and ‘Ertae’ as personal names, hence the capitalization of those two words.Footnote 31 Note that the ae of Ertae is composed of two separate letters, whereas elsewhere a single letter serves for that ae, the digraph <æ>. There is a reason for this discrepancy that will be shown below.

Who are these people and what are they doing, or having done to them? As indicated in the translation, in Old English the preposition on can mean either ‘on’ or ‘in’. That flexibility is one of the elements that can enable the fluid meanings proposed in what follows.Footnote 32 The casket designer revels in devices producing additional meanings.

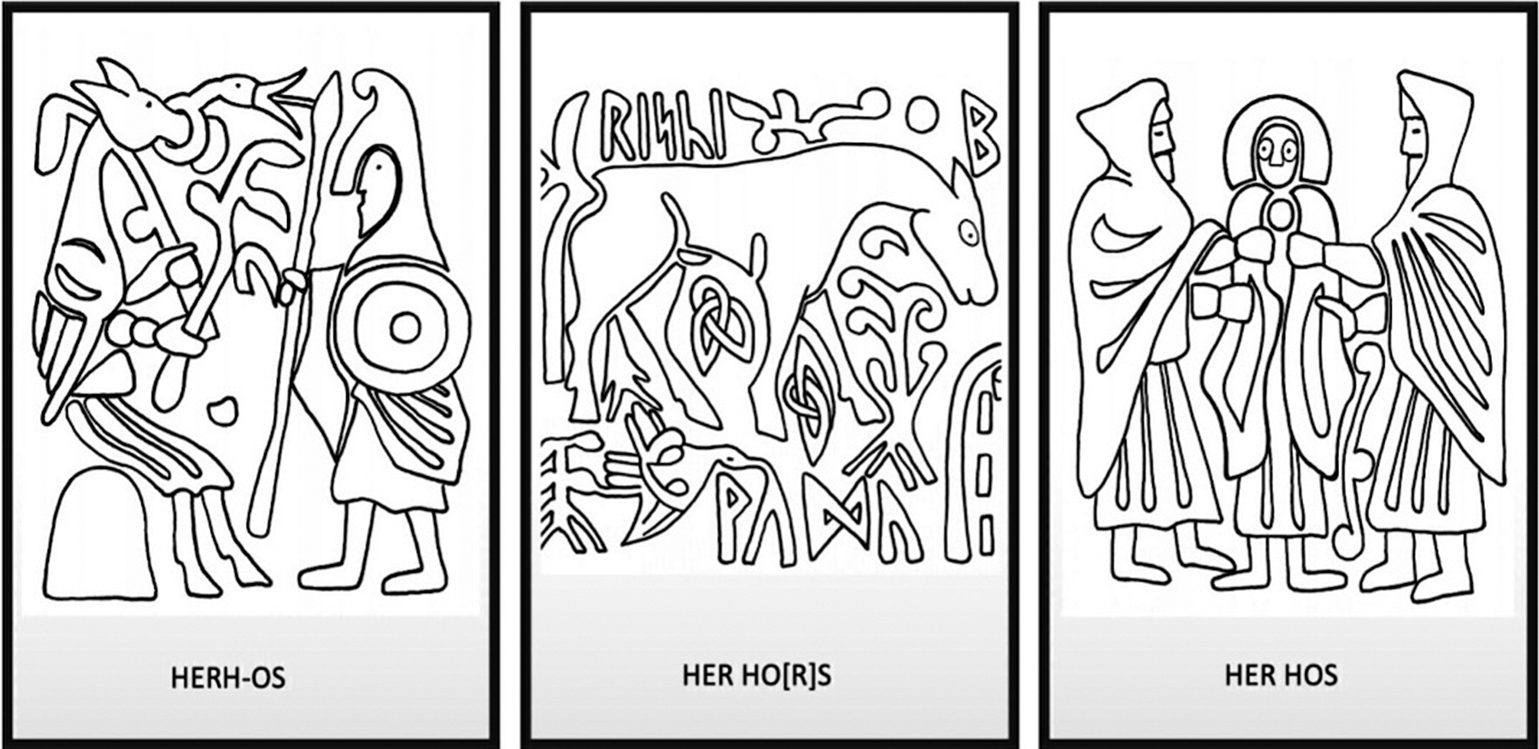

The first six runes of the inscription are transliterated H-E-R-H-O-S, and three different ways of reading these six runes have been proposed. Following a suggestion by Hertha Marquart, Hilda Ellis Davidson proposed reading these runes as a single word, the compound herh-os that she translated ‘temple-deity’ in reference to the hybrid being sitting on the mound at far left.Footnote 33 Many have proposed adding an r to read the phrase her ho[r]s (‘here, a horse’), referring to the horse dominating the central picture; some of those who prefer this reading interpret the horse as the hero Sigurd the Volsung’s Grani mourning his dead master in his grave mound.Footnote 34 A third group, observing that the word hos at line 924 of Beowulf refers to Wealhtheow’s attendants, argue that the phrase her hos (‘here, attendants’) refers to the two hooded figures holding a third between them in the picture at far right. The question is whether the letters H E R H O S refer to a single scene or should be understood in three ways to label each scene separately, as indicated by Melissa X. Stevens’ labelled drawing (Fig. 6.)

Figure 6. The three scenes on the Franks Casket’s right side interpreted by different arrangements of the six runes HERHOS. (Line-drawing by Melissa X. Stevens. Used by permission from Melissa X. Stevens.)

Such a sequence on the right-side panel might refer to a narrative like the other panels that represent recognizable scenes from stories, but lacking such a context, this discussion can only refer to the ritual that it apparently depicts, and this may in fact be all that the designer intended. Remembering that Old English does not insist that a pronoun should refer to the preceding noun as in modern English usage, it makes good sense to read the feminine pronoun hiri as referring to the person pent up in the mound. Thus ‘she’ is the female that Ertae has assigned to a sarden sorga, a ‘wretched den of sorrows’ (the grave mound viewed as a den from inside).Footnote 35 To carry this speculation further, ‘Ertae’ condemning someone to a grave suggests that this name must refer either to the supernatural (or costumed) horse-human sitting on a mound or to the unseen supernatural entity behind that muted figure. If that horse-headed hybrid is the spokesperson of a supernatural entity targeting the figure within the grave through the apparently speaking snake, what is the function of the bearer of goblet and staff?Footnote 36

This reading offers an implicit sequence of events that might go like this. (Others might read these scenes quite differently.) An edict or doom (dom ‘judgment’) is given to a warrior through the herh-os, an intermediary agent of the otherworld. As a result of this edict, a person is slain – or are they already dead? – and placed in a mound, perhaps after being given the ‘mordant’ drink, a cup of death.Footnote 37 There they await their further journey. In the picture on the right a person is restrained by a hos (attendants) and possibly being ritually reclothed.Footnote 38 That individual, now identified by the pronoun hiri as a woman, may not be considered thoroughly dead until her lingering spirit has been helped to escape the body. According to the final line of the surrounding poem, the person in the grave perceives this mound from the inside as a painful ‘den’ that she finds agonizing both mentally and physically as she waits for what comes next. What comes next in the sequence of events is a riderless horse that penetrates the wood between the worlds, coming to carry that beleaguered soul away.

The Stories on the Casket and on Gotland Picture Stone Ardre VIII

As noted above, three of the five stories illustrated on the panels around the sides of the casket are based directly on passages in Latin texts, demonstrating that the designer was highly literate and expected the viewer of the casket to be familiar enough with these texts to interpret the images that allude to them. The source of the Magi story on the front is the Gospel of Matthew (2: 2–12); the source of the mother wolf nursing the abandoned twins on the right side is the eighth book of the Aeneid; and the source of Titus recovering Jerusalem from the insurgent Jews on the back is The Jewish Wars by Josephus.Footnote 39 No written sources available in the early Middle Ages have been identified for the remaining three illustrations: the attack scene on the lid, Weland on the front panel,Footnote 40 and the horse with drink-bearer on the right-side panel. Scenes corresponding to the Weland and drink-bearer scenes are, however, found together outside of the high-status Latin culture of the monastery. They appear as two separate scenes on a single Gotland picture stone designated Ardre VIII (see Figure 7). Instead of having a triquetra between its legs, this horse has eight legs to indicate its liminal status. Although the eight legs are usually taken to identify it as the Norse god Odin’s horse Sleipnir,Footnote 41 this multi-leg feature is also found far outside the range of Odin and his horse.Footnote 42 According to Milićević Bradač, the eight-legged animal in its various forms (not always a horse) most often suggests that it is an animal that can cross the boundary between worlds in both death and shamanism.Footnote 43 It is thus possible that the eight-legged horses on the Swedish stones may bear only a generic relationship to Odin’s Sleipnir. In contrast, the Weland scene found farther down on the Ardre VIII stone (see Figure 8) has been identified indisputably as referring to that legendary smith – by the thatched smithy with its tools, the two dead boys’ beheaded corpses, and Weland flying away in bird form. In this image, he carries overhead a figure with trailing skirt that has been identified as Beaduhild (Bǫðvildr in ON).Footnote 44 A winged man carrying a woman overhead is found on a Viking-age cross shaft in Leeds Parish Church, Yorkshire. James Lang has identified this scene as ‘Weland’s Escape’ with reference to the similar scene on Ardre VIII.Footnote 45

Figure 7. The eight-legged horse and Weland scenes in context on the Ardre VIII Stone. The horse is at the top of the stone and the Weland scene near the bottom just under the ship. Photo by Bengt A. Lundberg, The Swedish History Museum, SHM 108199 HST, 1999. (Permissions: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License CC BY 4.0.)

Figure 8. Ardre VIII, detail. Weland (Vǫlundr in ON) flying away from his smithy. On this picture stone, the magical smith appears to be carrying a woman with her hair bound up in the traditional knot and wearing a trailing skirt. The bodies of the two beheaded boys extend outside the smithy at right. Photo by Employee at The Swedish History Museum, 108199_HST, 2016. (Permissions: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License CC BY 4.0.)

If there was a horn-bearer confronting that eight-legged horse with rider on Ardre VIII, that figure has evidently been obscured. Another picture stone, Tängelgårda I (not shown), depicts a figure that seems to be raising a horn to greet the rider on a horse marked with sharply triangular triquetrae (more precisely, valknuts), but this time the drink-bearer of this double-image welcome scene may be a man with a beard. This does not, however, appear to be a mortuary scene.Footnote 46 As with most traditions, the meaning of the horse and drink-bearer image probably varied according to circumstances.

The Limen-Crossing Horse and Roman Adventus Iconography

When interpreted within a mortuary context, the eight-legged horse on Ardre VIII and the horse with the triquetrae on the Tängelgårda I stone may be understood as variants upon the basic idea of a steed able to cross the boundary between worlds. If the scene on the Franks Casket has a meaning similar to that commonly accepted for the Gotland picture-stone scenes, in which a hero on horseback is welcomed to Valhalla,Footnote 47 the casket’s riderless horse may be interpreted as the designer’s version of a ritual taking place at the grave, at the beginning of the journey after death. In this case, the drink-bearer is easing that departure rather than hailing an arrival. Two scholars have separately identified the celebratory version in which the rider on horseback arrives as deriving from Roman adventus iconography. Sigmund Oehrl describes it as a welcome motif and relates it, in passing, to a scene found on Roman coins. In ‘Appropriating Victoria: Intercultural Transformations of a Visual Motif’,Footnote 48 Carol Neuman de Vegvar studies in depth the image of ‘a walking woman holding a drinking horn’ as it appears in texts in several languages with the woman serving drink in different ways and to different purposes. Neuman de Vegvar posits that this figure derives from the image of the goddess ‘Victory’ on portable Roman objects, including coins. Tellingly for our purpose, she points to ‘a stream of solidi’ (Roman coins) that brought the image of the ‘walking Victoria’ north to the islands of Gotland and Bornholm in late antiquity.Footnote 49 In short, the drink-bearer on the Gotlandic stones plausibly has roots in the Roman scene of a ceremony celebrating a victory, although, as Neuman de Vegvar emphasizes, the Gotland figure varies in its deployment. On the picture stones, as on the Franks Casket, this Roman scene of a welcoming home-coming celebration appears to have been reimagined in a mortuary context, with scenes of both departure and arrival featuring the psychopomp steed that has the ability to ‘bear its rider to the land of the dead’.Footnote 50

Buried Horses

The figure of a psychopompos in the form of a horse that can bear its rider to another world is surprisingly widespread in terms both of geography and time, and the soul-bearer concept appears to be at least one explanation for the ritual burial of horses found across Europe and beyond. Archaeology suggests that funeral rituals involving a spirit horse have existed for as long as humans have been friendly with horses. Horses are discovered buried with their riders in the late bronze age mounds called kurgans on the steppes of Ciscaucasia (made famous by Marija Gimbutas in The Language of the Goddess, originally published in 1989), in the early seventh-century mound 17 at Sutton Hoo in East Anglia, and as late as 925 on the banks of the Volga, according to the witness Ibn Fadlan (more about him below). A mid-fifth-century grave excavated in 1997 at the Lakenheath Air Force Base in Suffolk may serve as an example of this kind of equine-human interment. Apparently once covered by a mound, the grave contains a tall young warrior with his horse buried beside him, still adorned with its elaborate gilded harness.Footnote 51 In many cases, probably in most, a horse buried with its owner primarily signifies its master’s elite status, but companion animals were also buried with their owners, like the little non-working dogs buried with women in some sixth-to seventh-century Scandinavian graves.Footnote 52 In other cases the horse may be seen as forming part of a livestock sacrifice along with other animals; many were probably intended for the funeral feast.Footnote 53 When the animal is buried whole, however, it seems to be a significant part of the associated human’s life story and identity as perceived by those arranging the mortuary ritual. It would be difficult to interpret this horse buried face-to-face with the Lakenheath warrior in Fig. 9 as being merely a livestock sacrifice.Footnote 54

Figure 9. Mid-fifth-century grave with warrior and horse at Lakenheath Air Force Base, Suffolk. Photo by Suffolk County Council. (Used with permission from Suffolk County Council).

Even understood as a companion animal, the buried horse may memorialize more than the deceased’s attachment to a beloved steed, an identifying feature known to the mourners that could have been made part of the commemorative ritual. In interpreting ‘The Lay of the Last Survivor’ in Beowulf as one of four funerals strategically marking off sections of that poem, Gale R. Owen-Crocker proposes that the hawk and horse in lines 2262–5 are mourned as absent because the survivor has buried them with his lord: ‘The hawk and the horse feature in this elegy because they are dead, sacrificed and placed in the tomb of their owner’.Footnote 55 Supporting this interpretation with archaeological evidence mainly from Scandinavia, she points out that horse burials occur throughout the regions with Germanic settlement.Footnote 56 Chris Fern argues further that ‘Anglo-Saxon horse beliefs, whilst demonstrating notable insular traits, need also to be viewed as part of a wider pan-Germanic cosmological belief system’.Footnote 57 If the riderless horse on the Franks Casket represents the psychopomp arriving from the other world to transport its rider (unlike the horse and rider thought to be arriving in the other world on the picture stones), it is possible that the scene on the casket might illustrate the idea behind what was still a currently practiced religious rite in parts of Britain, including the burial or cremation of horses.Footnote 58 In whatever form the Northumbrian designer might have encountered the double-figure scene, it is used on the right-hand side of the Franks Casket to balance the Roman scene on the opposite side in which the abandoned boys are saved and fostered by a wolf. On one side an animal assists with life and on the other with the passage into death, with ‘drink’ thematic on both sides. The counterpoint intention is clear.

Considering the possible routes of transmission of similar mortuary practices between the cultures of Scandinavia and northern Britain, especially on the east coast of England in the Humber–Wash area, Chris Fern suggests that ‘the correlation between genealogy and ostentatious funerary theatre is demonstrated in the Anglo-Saxon text Beowulf. It may have been via the creation and dissemination of such oral genealogies and poetry connected with ruling groups that elite burial fashions, such as horse and boat burial, were transmitted across Europe.’Footnote 59 The archaeologist Howard Williams suggests a ceremonial occasion behind horse burial much like the one we propose. After discussing early English horse cremation as symbolic of the dead person’s elite status, he refers to analogous funerals from other countries that suggest such sacrifices might have served as both social and religious statements by mourners, referring simultaneously to the status of the deceased and to their belief in an existence after death. Williams emphasizes that the killing of the horse might have been understood as releasing its life force that could then enable it to convey its dead owner into a new, transformed state of being.Footnote 60

Human-equine burials are becoming more widely known and nuanced.Footnote 61 This is the first appearance of ‘buried horses’ in connection with the Franks Casket, which was created at a time when horse-burial or cremation may have been within the designer’s living memory as a now discouraged pagan practice, but where the idea of the buried horse as a spirit horse was too powerful a concept to be completely abandoned.

A Ceremony on the Volga and the Presiding Ritual Specialist

Such practices were continuing elsewhere. Some two centuries later than the carving of the Franks Casket, a ceremony with similar ritual elements was witnessed by the Arabic emissary Ibn Fadlan when he attended the obsequies for a Rus chieftain with a probable Norse background in the year 922. The ceremony that he describes is a ‘Viking’ cremation by the Volga river that included the ritual passing of a cup to a slave girl about to be sacrificed, as well as the sacrifice of horses. When Ibn Fadlan reports that the woman presiding over this ceremony was called the ‘Angel of Death’,Footnote 62 he uses an Arabic word that refers to a winged figure, so it may have been the best equivalent he could think of to translate the Germanic word valkyrja, if that term for the presiding woman was explained to him. On this occasion, the representative liminal barrier to the other world took the form of a doorway or gate that had been constructed in front of the ship in which the dead chieftain had been placed. As the slave girl in the ceremony was lifted to peer over the gate, she called out that she saw beyond it people who had died. The features of the historical funeral observed by Ibn Fadlan and only partially understood by him (as he says) can thus be assumed to echo those preserved on stone and whale bone in lands to the west. (See also below on some Old Norse textual parallels.)

Returning to our drink-bearer, the robed and hooded person on the Franks Casket may seem far removed iconographically from the Swedish horn-bearing women with their hair carefully twisted into a knot, but the shared associated imagery of the horse, the proffering of a drink, and the dead person (a rider on the picture stones and a corpse-like figure in the sorrow-den on the Franks Casket), and above all the appearance of the triquetrae between the horses’ legs, suggest cultural affinity. The apparent barrier of distance may be disregarded when the sea is viewed as a road where images can travel in portable objects and stories can travel orally to be received differently in other cultural contexts. One might think of Weland in the various stories about him, going north to gain magic and swan maidens and south to be admired for his craftsmanship. A Swedish presence in an early English context is archaeologically displayed by stylistic affinities of the masked helmet and other objects found at Sutton Hoo,Footnote 63 and again displayed most significantly of all by the curious fact that the monster-slaying hero of the most famous literary work in Old English is from what is now Sweden, and no English locality is ever mentioned in his story.

In whatever way the designer may have obtained inspiration for the images carved on the right-hand side of the Franks Casket, they seem meant to portray a ceremony with ritual stages rather than a narrative. Identifying the figure with the staff and goblet as a woman directing the ritual allows us to venture a final scenario for the scene where she stands facing a horse. This drink-bearer in the role of a ritual specialist is partnered with the horse in a graveside mortuary performance, after which it is expected that the horse, or its spirit, will carry the unhappy soul, here constrained in a ‘den of sorrows,’ away into another, perhaps better, world.Footnote 64

Addendum: The Woman With a Cup in the Context of Old Nordic Literature

Terry Gunnell

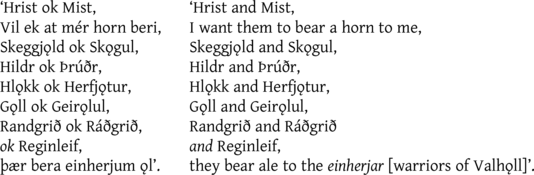

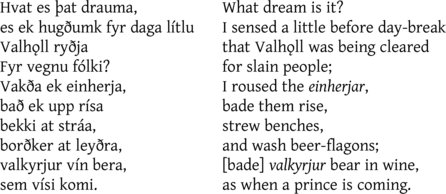

As pointed out above, in the centre of the enigmatic right end panel of the Franks Casket stands a figure facing the central grave mound (which seems to contain a body) carrying a staff, with a cup or goblet at hand height. Behind this figure is another figure (in a separate scene) who seems to be in the process of being dressed by two hooded figures. In regard to the figure in the central scene, there is little question about the popularity in the Old Norse world of the image of the lady with the cup, which has been found on numerous items of jewellery worn by women and as illustrations on a number of objects, ranging from one of the Gallehus horns from the early fifth century,Footnote 65 to the Gotland stones of 700–1100 CE (see above). Interpretations of the Norse figure have varied, many scholars simply choosing to identify these figures as valkyrjur on the basis of the statements in Grímnismál st. 36,Footnote 66 when Óðinn, who is being tortured between two fires, calls on valkyrjur to bring him something to drink:

A similar image appears in the skaldic poem Eiríksmál, in which Óðinn orders the valkýrjur to prepare for the arrival of those who had newly died on the battlefield:

In these poems, the valkyrjur have been relegated to being little more than barmaids, although at least in Eiríksmál they have retained some connection with the world of the dead.

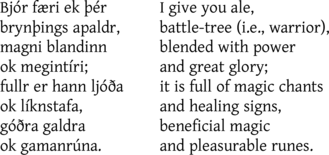

To my mind, much more interesting are three other strophes from the Eddic poems, the first of which shows a valkyrja in a very different light.Footnote 67 In Sigrdrífumál, st. 6, the hero Sigurðr has awakened a valkyrja who has been surrounded by a ring of fire on top of a mountain, and as dawn comes, she offers him a goblet full of beer before proceeding to teach him runic magic, in a sense initiating him:Footnote 68

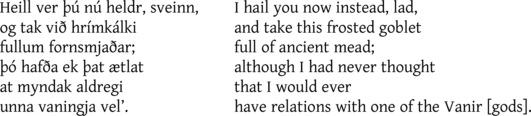

A similar ritual seems to occur at the end of the Eddic poem Skírnismál, when the jǫtunn (giant) maiden finally bows to Skírnir’s threats and agrees to sleep with the god Freyr. Beginning with words very similar to those that precede Sigrdrífa’s offer of ale (st. 4: ‘Heill’), Gerðr says:

Elsewhere in st. 17 of Vǫluspá, we have the image of the three nornir who sit beneath the world tree and ‘lǫg lǫgðu | líf kuru | alda bǫrnum | ørlǫg at segja’ (set laws, decide on lives of the children of men, proclaim fate). While the women, who are said to have risen from the waters below the tree, are not described as bearing horns, their situation at the Urðarbrunnr (well of Urðr/Wyrd) suggests that they too issue fate in the form of liquid. In each case here, we seem to be dealing with some form of rite of passage.Footnote 69

Bearing the above in mind, we can now proceed to the Gotland stones discussed above.Footnote 70 Several of them contain a scene at the top in which a male rider (sometimes identified as Óðinn) is being received by a woman with a drinking horn, perhaps a welcoming valkyrja. The significant figure in the image might not be the person arriving on the horse, but the person receiving him, in other words, the woman. As Amanda Green and others have shown, the idea of the male-ruled world of death (including Óðinn and Valhǫll) seems to be a relatively recent concept that was limited to certain parts of Scandinavia in later times. More common and widespread seems to have been the idea that the next life was ruled by women, such as the figures Hel, Freyja, Rán, Skaði and/or the valkyrjur. The term valkyrjur itself means ‘choosers of the dead,’ which enforces the idea that they rather than Óðinn were the ones who decided the fates of warriors. Once again, as suggested in this article, we seem to be dealing with a figure that serves as an initiator.

As mentioned above, the idea that the figure of the lady with the cup could also be seen as an initiator into the world of death receives some support from the figure of the ‘Angel of Death’, who leads the funeral proceedings among the Rus traders on the Volga in the account by Ibn Fadlan.Footnote 71 This makes sense if we return to the sequence of pictures on the right-hand side of the Franks Casket, reading them from left to right as in the illustration of Weland/Vǫlundr’s story on the front of the box. Following the decree of doom from the figure on the mound, and death represented first by the horse without a rider and the grave, comes the woman with the cup and the staff, and then an image, perhaps, of a figure receiving new clothes, suggesting a new identity or new status. If reclothing is happening here, either this is the deceased being ritually reclad, as often occurred in the funeral rites of the period (including the one reported by Ibn Fadlan), or it is the drink-bearer herself receiving the robes of her profession. If the latter, the fact that she bears both a cup and a staff could suggest that she has two functions. If we are dealing with Germanic traditions, it is possible that this scene is an early reference to a vǫlva like Þorbjǫrg lítilvölva, who is described in great detail in Eiríks saga rauða (Eric the Red’s Saga), ch. 4.Footnote 72 As the saga emphasizes, these female figures were in a sense living versions of the mythical nornir, because like the nornir they could see between worlds and had access to knowledge of the future, an ability that seems to have been naturally accessible only to the Nordic goddesses, but their human representatives could achieve it by training. The element of the staff, also mentioned in connection with a vǫlva in Laxdæla saga, ch. 76, is interesting in this context, not least in view of the number of female graves in which such staffs have been found,Footnote 73 because it seems to have been a form of insignia. As Jan Aksel Harder Klitgaard has suggested, this staff of office might even represent the world tree that the nornir sat beside when they decided fate.Footnote 74 Indeed, a possible parallel might be seen on a small gold foil found in Hauge, Rogaland, which shows a woman holding a plant of some kind.Footnote 75

If the figure facing the horse on the Franks Casket, understood as a woman like so many others in similar contexts, is seen as an initiator into the world of death, what then is happening in the picture to the left of the horse? Here it may be that we have one of the relatively few extant images from the early medieval period in which a character is shown wearing a mask. Interestingly, this figure seems to be wearing an animal mask on top of their head, rather than replacing their head, as in the case of most masks.Footnote 76 With human hands, this figure also bears plants, here crossed boughs which may perhaps be an emblem of office (see above). Wrapped around the muzzle of the mask is a snake with open jaws through which the figure seems to be speaking to a male warrior. One wonders whether this snake is meant to represent some form of higher power associated with the idea of horses dispensing fate, perhaps a reference to the god Freyr, often associated with both Sweden and horses,Footnote 77 or an Anglian equivalent of such a god.Footnote 78 Of particular interest here, however, is the fact that this figure seems to depict a human wearing a mask,Footnote 79 rather than being an attempt to show a supernatural figure viewed as half human and half horse. Interpreting the figure as an animal-masked human significantly changes the meaning of this series of images. With this image of a masked human that is ‘mound-sitting’ on the left and the possibly initiatory image on the right, the implication is that the picture at the centre of this panel also reflects human activities associated with prophesy, transformation and the boundary between life and death. Thus the three scenes may be understood as functioning together, perhaps as a series of performances.

Conclusion

Marijane Osborn and Terry Gunnell

In conclusion, we propose that, instead of referring to a known narrative like the images on the other three sides of the Franks Casket (Weland, the Magi, the She-wolf and Titus), the three scenes on the right-side panel of the casket show the designer attempting something different while still contributing to the ‘counterpoint’ programme established on the front panel. Mirroring the life-saving She-wolf recumbent in her leafy green den and giving drink to the boys that were meant to die (Aeneid 8: 630) – who will now live to change the world – is the female drink-bearer with her cup of death, the person dying or already dead in the barren sarden, and the horse alert and ready to leave this world with its rider. When viewing the right-hand side of the Franks Casket, one is meant to imagine being witness to a ritual, with the horse in this case waiting to transport the spirit of the deceased rather than having already done so as on the Tjangvide and Tängelgårde picture-stones. Unlike the She-wolf scene that opens up into history, this panel shows a very conclusive series of events: the costumed figure on the mound at left signifying judgment, on the right a figure being reclad(?) for the final act of leaving; and at the centre that final act on the brink of occurring. And yet to our sight the horse remains standing there waiting, with the mesmerizing triquetrae between its legs that echo somehow the Viking Age picture-stones of Gotland.

Exploring that Scandinavian link has expanded our understanding of the woman bearing a drinking-vessel in the context of events shown on the casket, and those carefully placed triquetrae widely broaden that context. Of the Franks Casket with its evocative narrative scenes, Ian Wood says, ‘Perhaps more than any other single object, it gives a hint of the range of ideas transmitted in the early middle ages, and of the determined attempt made by some to synthesize the wealth of traditions to which they were the heirs.’Footnote 80 While leaving unanswered many questions about cultural interaction and borrowing across space and time, this essay has attempted to demonstrate a strong affinity between singular scenes carved in northern England and Swedish Gotland. This similarity of design may suggest a particular agenda (among others) for the scenes on the right-hand side of the casket. In addition to drawing on themes from the Mediterranean Latin culture of the period, plus the widely-known Germanic Weland, the casket designer extends this inclusive programme beyond the familiar geography of the Mediterranean and its neighbouring parts of Europe by adding a culturally more proximate vernacular theme unique to Northwest Europe – the ritual of the drink-bearer and triquetra-marked horse.

Acknowledgements (Marijane Osborn)

I wish to express my gratitude to two people in particular: to Melissa X. Stevens -- for her artwork, but also for constant encouragement, help in tracking down articles, and expert aid in computer crises; and to Terry Gunnell, first for his interest in this project upon our meeting in Reykjavik, and then for participating in it. Diane J. Reilly encouraged me to think further about the image of the ‘drink-bearer’ herself. I am grateful, too, to the peer reviewers who offered thoughtful and engaged reports that helped me to refocus my argument in ways that greatly improved it.