Introduction

In 2010, the Carter Center, an international nongovernmental organization (INGO) headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, established a mental health program in the low income, West African country of Liberia.Footnote 1 Founded in 1981 by former U.S. president Jimmy Carter and his wife Rosalynn, the Carter Center focuses on peace and health issues (Chambers, Reference Chambers1998). The Center’s Mental Health Program in Liberia challenged the typical pattern of INGOs working in stable environments on health problems with technical fixes (Brass, Reference Brass2011; Kenworthy et al., Reference Kenworthy, Thomann and Parker2018; Krause, Reference Krause2014, pp. 32–36). Liberia had experienced a brutal civil war from 1989 to 2003 that killed 250,000 people and displaced one million (Downie, Reference Downie2012). In 2022, Liberia’s annual GDP per capita was USD 754 (World Bank, 2023), 50% of its population lived below the poverty line, and 18% of GNI and 35% of health spending came from donors (Institute for Health Metrics & Evaluation, 2023; UNDP, 2021; World Bank, 2022). Similarly challenging, mental health, with its diversity of conditions and causes, lacks easy biomedical solutions (Kilbourne et al., Reference Kilbourne, Beck, Spaeth-Rublee, Ramanuj, O’Brian, Tomoyasu and Pincus2018) and receives little donor funding (Clark & Patterson, Reference Clark and Patterson2022). Severe stigma toward people suffering from mental health disorders as well as their health providers and families persists worldwide (Lancet, 2022). In Liberia, people with these conditions often face social rejection and abusive treatment (Dossen et al., Reference Dossen, Mulbah, Hargreaves, Kumar, Mothersill, Loughnane, Byrd, Nyakoon, Quoi and Ebuenyi2024; Gwaikolo et al., Reference Gwaikolo, Kohrt and Cooper2017; Ministry of Health, 2016; Ministry of Health & Social Welfare, 2009; WHO, 2017). Indeed, we met Liberians who had been socially ostracized and physically abused because of their conditions, and a number of mental health workers told us that colleagues and neighbors labeled them “crazy doctors” because of the patients they treated. These societal dynamics make any program to address mental health challenging and open to multiple meanings among stakeholders.

This article uses the case of the Carter Center’s investment in Liberia’s national mental health program to explore how three stakeholders (INGO personnel, government officials, and mental health clinicians) involved with this stigmatized health issue make meaning of their work and how their failure to align their meanings and goals then shaped program outcomes. Our interest in this topic emerged inductively, as we investigated Liberia’s mental health policy (Patterson & Clark, Reference Patterson and Clark2024). We find that INGO personnel emphasized personal connections to Liberia, the program’s virtue, their expertise, and financial costs to make sense of their work. Liberian government officials perceived the program in light of government ownership, competing priorities, and funding challenges, while the mental health practitioners understood it as an avenue to help others and advance professionally. This article contributes to understanding the “multiple realities” of development by illustrating that meaning-making cannot be divorced from actors’ various forms of power (Appe & Telch, Reference Appe and Telch2020). Power is the ability to directly coerce others’ actions or, more often, to indirectly shape others’ “subjective beliefs and interests (wants, desires, and preferences)” (Lukes, Reference Lukes2015, p. 270). Power may be exercised through force (compulsory power), monetary resources (economic power), expertise (epistemic power), connections to others (network power), normative position (moral power), and/or legal authority (institutional power) (Barnett & Duvall, Reference Barnett and Duvall2005; Moon, Reference Moon2019; Shiffman, Reference Shiffman2014). Power also may manifest through the “weapons of the weak” or actions such as noncompliance and exit that do not directly challenge those on whom the weak depend but that overtime can undermine their legitimacy (Scott, Reference Scott1987; see also Hirschman, Reference Hirschman1972). The Carter Center’s meaning-making was tied to its network, epistemic, moral, and economic powers, while the government’s meaning-making was linked to an institutional authority that had little capacity due to weak economic power. The mental health practitioners’ understanding entangled with their weak moral and epistemic powers and their powers of noncompliance and exit. This research matters for two reasons: First, meaning-making helps INGOs to foster legitimacy in the face of resource competition and criticisms over their accountability, responsiveness, and effectiveness (Brass, Reference Brass2016; Ebrahim, Reference Ebrahim2005; Kumi, Reference Kumi2017; Watkins & Swidler, Reference Watkins and Swidler2013). Second, stakeholders’ divergent meanings and the ways those meanings tie to various powers can shape development outcomes.

The article unfolds as follows. After situating the work in the literatures on social constructivism and power, we describe the Carter Center mental health program in Liberia and outline our methodology. We then share findings about how power and meaning-making intertwined as stakeholders sought to understand the program. The Discussion considers how the stakeholders’ inability to align around shared meanings and goals affected program outcomes, and how the case generates lessons about meaning-making in development. We conclude with questions for future research.

Ideas and Power in Development

Social constructivism asserts that subjective perceptions of reality (or “ideas”) influence interactions in the international realm in ways that material resources do not (Wendt, Reference Wendt2012). Actors interpret and evaluate their experiences to generate ideas that affect, for example, which global issues are prioritized or why conflict occurs (Pouliot, Reference Pouliot2007). Ideas help development actors understand social phenomena, including “the complex assortment of means, motives, and opportunities surrounding efforts by outsiders to ‘help’” (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Rodgers and Woolcock2008, p. 201). From this perspective, INGOs are motivated by much more than structural limitations and strategic calculations (Cooley & Ron, Reference Cooley, Ron, Prakash and Gujerty2011). By leaning on multiple but fluid understandings of their mission, development actors can justify their organization’s raison d’être, programs, and use of resources (Lewis & Kanji, Reference Lewis and Kanji2003; Wong, Reference Wong2012).

For social constructivists, ideas undergird how power is understood and exercised (Shiffman, Reference Shiffman2009), while power affects how individuals understand social phenomena. Power is relational, manifest at the micro- and macro-levels, and often operating in invisible ways (Lukes, Reference Lukes1974). The intersection of ideas and power is manifest when NGOs emphasize their goals of improving humanity, assisting marginalized populations, or tackling stigmatized issues (Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2005; Lashaw et al., Reference Lashaw, Vannier and Sampson2017), thereby enabling them to tap virtue as a power source (moral power) (Shiffman, Reference Shiffman2014). NGOs may understand their work in light of their relationships with communities and individuals in the global South (Appe, Reference Appe2022; Kinsbergen et al., Reference Kinsbergen, Schulpen and Ruben2017), meanings that intertwine with network power. Still other NGOs may view their activities in terms of their expertise (Krause, Reference Krause2014), thereby linking to epistemic power. NGOs also have resources that may enable them to marshal economic power in interactions with other stakeholders (Scherz, Reference Scherz2014).

Host-country governments and participants also make meaning of development initiatives. Particularly in low-income countries, they may view programs as buttressing the government’s weak economic power through needed resources (Watkins & Swidler, Reference Watkins and Swidler2013). Programs also may be understood as government endeavors, since internationally recognized state sovereignty gives governments the institutional power to make policy decisions such as approving NGO programs and claiming credit for their outcomes (Englebert, Reference Englebert2009). Local participants may share an NGO’s virtuous understanding, though they may focus on individual advancement, not system capacity building (Scherz, Reference Scherz2014). Such perceptions reflect participants’ limited economic power, particularly in contexts like Liberia with few options for socioeconomic advancement. Because various stakeholders have unique perspectives, interests, and experiences (Hilhorst, Reference Hilhorst2003, p. 33; Scherz, Reference Scherz2014), their subjective meanings and power differentials open the door for a lack of alignment around program goals which, in turn, may affect outcomes (Shiffman & Shawar, Reference Shiffman and Shawar2022).

The Carter Center Mental Health Program in Liberia

The Carter Center sponsors two types of programs under the banner of “Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Bringing Hope.” Its peace programs include conflict resolution, rule of law, human rights, and democracy promotion, while its health programs include mental health, maternal and child health, malaria control, and elimination and/or control of five neglected tropical diseases (trachoma, river blindness, Guinea worm, lymphatic filariasis, schistosomiasis). In 2022, it had 280 staff and the majority of its $122 million expenses went for health projects (Carter Center, 2023, p. 7).Footnote 2

The Carter Center’s Mental Health Program “started basically because Mrs. Carter wanted to continue her interest in mental health” (Interview 35), an issue she had focused on as the first lady of Georgia and then throughout her husband’s presidency. At the Carter Center, Mrs. Carter first developed a U.S.A-oriented mental health program with a substantial focus on anti-stigma work; the Center launched its first overseas mental health program, in Liberia, in 2010. By 2020, Carter Center health officials had begun to weave mental health programming into its other initiatives such as malaria and lymphatic filariasis projects in Haiti and the Dominican Republic (Interviews 49, 52).

Although the Carter Center worked on stigma reduction, policy development, and advocacy in Liberia (see Patterson & Clark, Reference Patterson and Clark2024), the program’s centerpiece—and this article’s focus—was a workforce development initiative to provide outpatient mental health services at the primary care level (Interview 51). At the program’s inception, Liberia had only one psychiatrist, no psychologists, and zero physician assistants, nurses, or social workers qualified to work with psychiatric patients (Ministry of Health & Social Welfare, 2009, pp. 17–18). The INGO wanted to extend mental health services widely and rapidly, and although the Carter Center supported the 2009 Mental Health Policy objective of increasing the number of psychiatrists working in Liberia, such a goal was a long-term project (Patterson & Clark, Reference Patterson and Clark2024).Footnote 3 For the INGO, the most expeditious way to provide care was to upskill nurses and a few physician assistants who were relatively numerous and already employed in government clinics. Such task shifting to lower-level health workers could facilitate quick provision of mental health services (Interviews 9, 35, 45), and this practice is common in low-income regions such as sub-Saharan Africa that face critical health workforce shortages (Yankam et al., Reference Yankam, Adeagbo, Amu, Dowou, Nyamen, Ubechu, Félix, Nkfusai, Badru and Bain2023, p. 2).

Designed and implemented in collaboration with the ministry of health, the Carter Center-supported training lasted six months. The INGO brought in a U.S. psychiatric nursing professor to collaborate with Liberian nursing faculty to develop a culturally appropriate curriculum, contracted with local venues and flew in expert instructors, and supported trainees’ room and board costs (Interviews 1, 46, 55). Clinicians were trained through both classroom instruction and clinical rotations to diagnose mental health conditions and epilepsy (often confused with mental disorders), treat them with a limited number of medications, and follow patients’ progress. The Carter Center also funded collaboration with the Liberian Board of Nursing and Midwifery and the Liberian National Physician Assistants Board to develop and administer certification examinations to license the mental health clinicians (Interviews 10, 35, 51). The Liberian government paid trainees’ salaries during the training period and ensured trainees could return to their health post jobs. Between 2010 and 2021, the program trained and licensed 308 mental health clinicians, with 168 specializing in adult mental health and 140 in child and adolescent psychiatry (Interviews 46, 47, 48). As of 2022, mental health clinicians served in all 15 Liberian counties, with each county having at least 18 clinicians (Interview 2). Unlike in high-income countries, these primary care mental health clinicians diagnose conditions and prescribe medications, even though they lack direct supervision by a psychiatrist, a point we address below. Given the fact that this program differs from most INGO health programs in its issue focus and devotion to capacity building, how did stakeholders make meaning of this 12-year effort?

Methodology

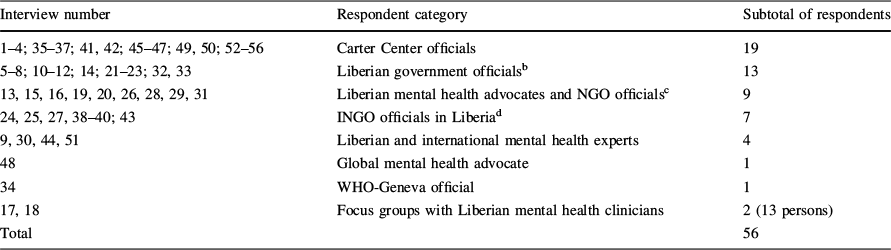

Our research used an inductive analysis of interviews, focus group discussions, and Carter Center mental health program documents. Between August 2020 and May 2022, we conducted 56 semi-structured interviews: 23 via Zoom and one by telephone in 2020 and 2021, 31 in person in May 2022 in Monrovia, Liberia, and one via Zoom that same year (see Table 1). Of the respondents, 19 were current or former Carter Center employees, and the rest were Liberian stakeholders and other INGO representatives. Among the Carter Center employees, we interviewed senior leadership as well as mental health program staff in Atlanta and Liberia. Liberian respondents included mental health clinicians trained in the Carter Center-sponsored program, government officials, academic experts, and representatives of advocacy organizations and Liberian NGOs. We identified key informants purposefully, based on their past or current involvement in Liberia’s mental health program. Because we conducted interviews with original program leaders and current implementers, we could ascertain nuances of program meanings.

Table 1 Interviews and focus groups

|

Interview number |

Respondent category |

Subtotal of respondents |

|---|---|---|

|

1–4; 35–37; 41, 42; 45–47; 49, 50; 52–56 |

Carter Center officials |

19 |

|

5–8; 10–12; 14; 21–23; 32, 33 |

Liberian government officialsb |

13 |

|

13, 15, 16, 19, 20, 26, 28, 29, 31 |

Liberian mental health advocates and NGO officialsc |

9 |

|

24, 25, 27, 38–40; 43 |

INGO officials in Liberiad |

7 |

|

9, 30, 44, 51 |

Liberian and international mental health experts |

4 |

|

48 |

Global mental health advocate |

1 |

|

34 |

WHO-Geneva official |

1 |

|

17, 18 |

Focus groups with Liberian mental health clinicians |

2 (13 persons) |

|

Total |

56 |

|

aInterviews 1–33, Monrovia, Liberia, May 2022; Interviews 34–55, Zoom, August 2020-January 2022; Interview 56, telephone, March 2020

bEight respondents from the Ministry of Health; others from the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection, Board for Nursing and Midwifery, Police Training Academy, and Bureau of Immigration, Monrovia, May 2022

cRespondents from Cultivation for User’s Hope, Liberian Association of Mental Health Practitioners, Liberian Mental Health Coalition, Liberian Association of Psychosocial Services, and the Liberian Center for Outcomes Research in Mental Health, Monrovia, May 2022

dRespondents from Médecins sans Frontières, Partners in Health, Last Mile Health, Monrovia, May 2022, and the International Rescue Committee, Zoom, December 2020

We conducted interviews until reaching saturation, or that point when the replication of themes throughout the data was apparent (Morse, Reference Morse1995, p. 148). We also conducted two focus group discussions in Liberia, one with six mental health clinicians and one with seven school-based clinicians, all Carter Center trainees. Participants were divided roughly equally between men and women. Both focus groups were held in Monrovia, though participants came from five counties (Bomi, Montserrado, Margibi, Nimba, and Sinoe). Inclusion of these counties ensured geographic distribution and population representation, because these counties are home to over one-half of Liberia’s population (Yates & Mehnpaine, Reference Yates and Mehnpaine2023). Interviews lasted from 30 to 90 min; focus groups ran approximately two hours. All were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, with authors then reading transcripts for accuracy.

To protect participants, all respondents were promised anonymity (the study collected no personal information) and confidentiality (the study would not reveal respondents’ identities, attach their names to quotations without permission, or identify their organization if doing so could potentially reveal their identity). All study participants signed a written informed consent. The study received ethics approval from the authors’ home universities (University of the South [1607 515-1], Tulane University [2020-895]) and the University of Liberia [22-04-313]. For simplicity, all interviews and focus groups are numbered consecutively in one list, though the focus groups are delineated in the text.

To analyze the data, we first hand-coded the transcripts using the same inductive approach for the interviews, focus groups, and Carter Center reports, based on a list of themes and associated codewords we generated from the interviews and the development literature. Themes included virtuous work, personal ties to the issue and/or place, expertise, sustainability, outcomes, and resources. To increase reliability, both scholars read and coded the transcripts in an iterated fashion until themes emerged and were agreed upon. We also examined documents from the Liberian government and multilateral institutions to establish basic facts about the Liberian health system and economy.

Findings: Meaning-Making and Forms of Power

This section reports how the three stakeholders made meaning of the program and how meanings and powers intertwined.

INGO Officials

Carter Center employees often began by discussing the program’s foundation in key actors’ personal connections, a view that echoed network power. They emphasized that President and Mrs. Carter had a long history with and a personal “fondness” for Liberia that dated back to President Carter’s first visit in 1978 (Interviews 41, 46, 50, 54). Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the Carters aided Liberia with conflict resolution and democracy promotion, and each visit deepened their commitment to Liberia’s future and its people (Interviews 41, 45, 46, 50, 53, 54). Exerting moral power, Mrs. Carter reportedly expressed concern about population mental health (Interview 54), telling staff, “We should see if we can adapt our mental health program to help Liberia” (Interview 45). This concern dove-tailed with the aspirations of Carter Center Mental Health Program Director Dr. Thomas Bornemann (Interview 35), whose work on refugee mental health and the World Health Organization’s 2001 World Health Report (that featured mental health) brought global connections and network power. Bornemann’s desire to build mental health systems in low- and middle-income countries, not solely provide short-term treatment to people affected by disasters (Interviews 41, 47, 55), aligned with the Carters’ interests in global mental health. Bornemann gained Carter Center Board funding to start the Liberia program, and leveraged the Carters’ backing when some INGO officials viewed the initiative to be “a stretch” because of Liberia’s weak healthcare infrastructure and because mental health had “always been a domestic program” (Interview 35).

Personal connections and the network power they generated also manifest in the first in-country program director. An expert in child behavioral health, Dr. Janice Cooper was from a well-connected Liberian family that fled to the U.S.A during the war (Interview 35; see also Cooper, Reference Cooper2017). Cooper understood INGOs, Liberian politics, the needs of the Liberian population, mental health issues, and Liberian gatekeepers. Network and epistemic powers enabled Cooper to collaborate with key Liberians to write the country’s first mental health policy in 2009, which included the above-described task-shifting plan (Patterson & Clark, Reference Patterson and Clark2024; Interviews 35, 47, 54). Several INGO respondents said that the program’s establishment only made sense because of Cooper’s involvement, as she marshaled network and epistemic powers to effectively broker agreements among internal and external players in the postwar policy vacuum (Interviews 9, 35, 45, 54).

Stressing a theme that augmented the INGO’s moral power, Carter Center officials understood the work in light of the organization’s virtuous mission of “bringing hope” to Liberia, a country that had experienced mental and physical distress during the civil war. Respondents recounted how combatants destroyed health infrastructure, including the country’s one psychiatric hospital (Interviews 1, 2, 49, 50, 56), and brutally targeted civilians based on ethnic, religious, and local identities (Interviews 37, 40; see Ellis, Reference Ellis1999). According to a WHO-sponsored 2005 study, between 61 and 77% of women experienced sexual violence (Omanyondo, Reference Omanyondo2005; see also Jones et al., Reference Jones, Cooper, Presler-Marshall and Walker2014; Ministry of Health & Social Welfare, 2009, p. 20), and thousands of young men were forced to serve as soldiers (Interview 38). This mass violence brought tremendous psychological trauma to the population (Interview 53), with many people “suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder” (Interview 45). Victims and perpetrators were socially ostracized, with those who had suffered sexual violence in particular “treated as pariahs” in their communities (Ministry of Health & Social Welfare, 2009, p. 36). The stigma and silence around sexual violence and mental illness, as well as the fact that some postwar government officials were warlords who had overseen this violence, meant that the government was unlikely to directly tackle this issue (Hensell & Gerdes, Reference Hensell and Gerdes2017). Additionally, because “discriminatory gender norms tend to reassert themselves quickly in post-conflict areas,” public mobilization to challenge “ingrained community attitudes and practices” and to push government to address the legacy of sexual violence was minimal (Jones, et al., 2014; see also Interview 45). The traumatic and stigmatizing nature of Liberia’s mental health issue facilitated the INGO’s virtuous perception of its work.

This virtuous meaning also revolved around the fact that the INGO addressed an issue that most development actors avoid. One Carter Center respondent explained,

We didn’t want to duplicate what others might be doing…. The Carter Center was trying to fill the gaps, look at what had not been addressed, look at what the least popular approach might be, but what could have the greatest gain for the population (Interview 45).

INGO respondents described how “filling a gap” led to virtuous outcomes that intertwined with the INGO’s moral power: Trained mental health practitioners alleviated suffering, supported families, combatted stigma, and addressed communities’ fear during the Ebola crisis (2013–2016) and the COVID-19 pandemic (Interviews 8, 15, 47, 52, 55).

Meanings related to personal connections and virtue were manifest when respondents tied mental health to the INGO’s other Liberia programs. Carter Center staff understood “bringing hope” in relation to the INGO’s objective of “waging peace” in a country where despite the war’s official end in 2003, high levels of distrust, anger, and war trauma continued to foment periodic outbreaks of violence (Carter Center, 2010). The Carter Center’s conflict resolution program reached out to Bornemann, with the idea that individual-level, psychological healing could promote national healing, foster reconciliation, and bring hope to local communities (Interviews 35, 41, 42, 45). Thus, as one INGO respondent remembered, “We didn’t separate it [mental health] out as a standalone project in Liberia” (Interview 45). In addition to deepening moral power, this approach also relied on network power, for it capitalized on relationships and trust generated by the INGO’s almost continuous presence in Liberia throughout the civil war (Interviews 47, 50). As one respondent explained, “The Carter Center had an infrastructure on the ground on the peace side which enabled us to facilitate the early visits of the mental health team, making it relatively easy to start up work in an extremely challenging environment” (Interview 50).

A third way INGO officials understood the program was in terms of their mental health expertise and experience with workforce development. Seeing the Carter Center as uniquely qualified for the Liberia work, INGO staff stressed the organization’s long-standing, anti-stigma programs and policy advocacy in the U.S.A., its professional, experienced staff in Liberia (Interviews 5, 43), and its design of community healthcare worker trainings in Ethiopia in the early 2000s. The Liberia program copied the Ethiopia train-the-trainer model, by first paying foreign instructors to teach community health workers and then, as local professionals learned the material, shifting training responsibilities to them (Interviews 41, 45, 47, 54). The INGO assumed that the Liberian training eventually would be handed over to nursing schools with updated psychiatric curriculum and would be government funded (Interview 51), a pattern of sustainability that had occurred in Ethiopia after the Carter Center program ended (Interviews 35, 45, 51). Liberia’s continuation of the program could demonstrate the Carter Center’s expertise in facilitating sustainable mental health work in other countries (Interviews 1, 37). Additionally, the trainings allowed the INGO to exhibit a virtuous commitment to share knowledge (Scherz, Reference Scherz2014). Leaning on its knowledge and experiences to address a stigmatized issue augmented the INGO’s epistemic and moral power.

Finally, senior INGO officials in Atlanta tended to understand the program in terms of financial resources and health outcomes, which some thought it had not demonstrated. In a point of contention, Liberia-based INGO officials pointed to the outcome of 308 clinicians who served throughout Liberia (Interviews 1, 4, 56). But Carter Center administrators questioned what this training actually meant for Liberians living with mental health disorders. One asked,

They [the trained clinicians] were going back into the communities, but what exactly were these people doing? …Were they going back into the communities and actually using the skills that they were taught and to what extent are they doing that? And what are they actually seeing out there? (Interview 37)

Arriving at a shared understanding of the program was problematic because neither the INGO nor the government collected data on mental health prevalence, the number of patients treated by trained clinicians, or the types of cases clinicians saw (Interview 4). Data collection took clinicians away from patient care and necessitated technology to store and transfer information. When the program started, stakeholders anticipated that the ministry of health would address these hurdles as more clinicians were trained and communication infrastructure improved. However, this took longer than anticipated and in the meantime, the lack of data made it hard to see the impact of training for improving health outcomes. This murkiness led some INGO administrators to perceive the program to be a one-off endeavor rooted in the Carters’ special relationship to Liberia, and thus, not an initiative that merited endless financial support or replication elsewhere (Interviews 35, 37). One respondent questioned how much longer the INGO would continue to fund the program (Interview 37), illustrating how the INGO’s leaders could use economic power to discipline the program. Although senior leadership reduced the program budget in years before our research (Interview 46), they did not cut it off completely. In response, INGO officials in Liberia were working in 2022 with the ministry of health to develop an online tool for quickly reporting data, something possible a decade after the program’s start due to improved internet access (Interview 7).

Liberian Government Officials

The Liberian government officials we interviewed also understood the program in terms of its virtue, the INGOs’ expertise, and personal relationships, with one saying, “[I have] been a long time with the Carter Center” (Interview 14, see also Gwaikolo et al., Reference Gwaikolo, Kohrt and Cooper2017; Interviews 6, 12, 22, 33). Yet, their meaning-making stressed the government’s role, national health priorities, and limited financial resources, meanings that aligned with an institutional authority that lacked capacity due to low economic power.

Officials understood the program to be a government program. Ministry of health officials had participated in its design, approval, and implementation (Patterson & Clark, Reference Patterson and Clark2024; Interviews 5, 33), and the INGO only began to collaborate with the government after the ministry named mental health as a priority issue in 2008 (Interviews 41, 45, 50, 54). The INGO then supported the country’s 2009 National Mental Health Policy, participated in its Technical Coordinating Committee for Mental Health to oversee policy implementation, and made a long-term commitment to workforce development (Interview 1). Ministry officials’ understanding that this was a government program was reflected in debates about the plan to have non-psychiatrists diagnose and prescribe medications. Several ministry officials had received medical or social work degrees abroad during the war years, and they doubted that anyone with only six months of training would be qualified for these tasks. One involved official reported that there was a lot of resistance, but ultimately the government approved the approach because it lacked alternatives (Interview 12). This governmental decision reflected the government’s institutional authority, which most Carter Center officials recognized when they asserted, “We don’t own this” in response to demands from Atlanta-based officials for more Liberian government commitment (Personal communication, Carter Center official, September 30, 2020).

The government’s institutional authority allowed it to decide health policy priorities, even if it lacked the capacity to ensure those priorities were funded. As elected officials, the government sought to prioritize issues widely perceived to affect the population (Interview 21), but prioritization also reflected the cultural context in which many Liberians view mental illness through a spiritual lens. Almost all respondents explained that, despite broad acknowledgment of war-related trauma and the presence of psychosocial programs to address it, many Liberians believe that the more serious and visible mental health disorders (i.e., psychosis) were contagious and caused by witchcraft or supernatural punishment for misdeeds (Interview 33). These statements mirror the findings of an in-depth study of Liberian culture and mental health (WHO, 2017, p. 25). This spiritual understanding leads people to seek care from traditional and faith healers before they look to government or NGO clinics. Distrust of government, the wide accessibility of traditional and faith healers, and care provided by spiritual community members also drive this pattern (WHO, 2017, p. 21). Thus, some government respondents doubted there was much public demand for the mental health clinicians’ services (Interview 22).

For this resource-poor government, perceived low service demand competed with the expectation that the government would address the major causes of death: tuberculosis, malaria, maternal conditions, and lower respiratory infections (WHO, 2023). Even though government officials understood mental health care to be under their institutional authority, the government’s dearth of economic power meant they could not prioritize it. One ministry of health official explained:

The total [government] budget of about $500 million …is not enough to take care of everything. For the ministry of health, the budget …is between [USD] 63 and 73 million [and] almost 70 percent goes toward personnel costs. So you don’t have much to do what you need to do …. When you talk to government officials, everyone is concerned [about mental health], but it’s that we don’t have enough resources to take care of all of the priorities … and also take care of mental health (Interview 21).

By juxtaposing “all of the priorities” with mental health, the individual illustrated that mental health was a distinct, lower prioritized issue. The response also hints at a larger challenge: despite its institutional authority to decide on mental health policy, the government’s weak economic power undermined the training program’s investment in personnel since frequent stock-outs of psychotropic medications in public clinics made it difficult for the mental health clinicians to help patients (Interviews 17/FDG, 24, 36, 37, 46). The government was not unaware of these problems, but as one exasperated official stated, “I want to be very frank with you… we have plans to [bring medications] but we don’t have that many resources” (Interview 6).

Mental Health Clinicians

The mental health clinicians made meaning of the program through the lenses of virtue, expertise, and economic advancement. They wanted to help people with mental health disorders (Interviews/FGDs 17, 18), many were “doing the work in the context of recovering from their [own] trauma” (Interview 47), and they were often stigmatized for their efforts (Interviews 3, 46, 52). Their task was made more difficult because many were assigned to a community that was not of their choosing and far from family, and many were not provided adequate accommodation (Interview 7). They also viewed themselves to be specialists with unique training for community-based mental health work. They were no longer just general nurses, but members of a profession that should receive supervision and continuing education (Interviews 5, 17/FGD, 28). Meanings around virtue and expertise had the potential to intertwine with the exercise of moral and epistemic powers. However, some supervisors did not recognize the clinicians’ expertise and assigned them to regular wards where they treated all patients, not just mental health cases (Interview 17/FGD). Partly, this was because some health centers had an insufficient number of mental health cases to warrant a designated mental health clinician (see above). In addition, because the government allocated few funds to mental health and because the INGO focused on trainings, clinicians received no supervision by psychiatrists and few refresher courses (Interview 5). When the program was established, the plan was that supervision would occur once a significant number of psychiatrists were trained. But in the meantime, some clinicians reported feeling unsupported, isolated, and disrespected (Interviews 5, 17/FGD, 22).

In addition, the clinicians made meaning of the program as a path toward economic advancement. They assumed that because trainees acquire specialized skills and credentials, they would gain career advancement and a higher classification on the ministry of health pay scale. Yet this did not occur. Advancement was difficult for public sector workers because a spending ceiling agreed to with the International Monetary Fund forced the government to make painful budget decisions (Interviews 5, 8; International Monetary Fund, 2019). Salaries remained extremely low, demoralizing the clinicians (Interview 19). The government’s institutional power to make budgetary choices, as well as its limited economic power to finance health, tainted this meaning for clinicians.

Discussion: Varying Meanings, Divergent Powers, Suboptimal Outcomes

The stakeholders’ different meanings and powers affected the program over time. The government’s limited economic power meant it depended on the INGO to pay for the trainings, which totaled nearly USD 100,000 per cohort (Interviews 5, 21, 22). Although government officials appreciated trainings, they really wanted the INGO to build workforce capacity beyond mental health. One official said, “What needs to be incorporated into Carter Center’s teaching models [is that] the mental health clinicians become more [in tune with] other disease conditions. Let them not see mental health as standalone” (Interview 22). Asserting that the INGO had adequate resources, this official said that a more beneficial long-term investment would build the capacity of a [health] department at a university (Interview 22).

The parties’ inability to align their program meanings and goals was apparent in 2022, when the ministry of health asked the Carter Center to fund an additional training cohort. The INGO tabled the request as it waited for the government to develop a plan for future trainings, thus providing the INGO a “clear-cut exit strategy.” The Carter Center had already declared that the 2020 cohort was “the last,” a decision reflecting program budget cuts made at the INGO headquarters (Interview 2). Thus, the 2022 request challenged the INGO’s understanding that it had built a government-supported sustainable program. But sustainability required the government to exercise its institutional power to decide to use limited resources for training. The INGO’s multiple meanings for the program added to the conundrum. Not supporting the government’s request could undermine its commitment to Liberia and its moral and network power, but funding the training could undermine the INGO’s epistemic power as an expert that had designed a sustainable program. And despite some government officials’ assumptions, the INGO did not have limitless resources (Interviews 2, 3, 45, 46).

Similarly, meaning and power contestation threatened to undermine gains in workforce development. The clinicians’ understanding that as experts doing difficult, virtuous work they should be adequately remunerated came up against the INGO’s understanding that the government had the institutional authority to make decisions on salaries and position descriptions. A few clinicians were frustrated that the INGO would not upgrade their material conditions (Interview/FGD 18), though most wanted the INGO to marshal its various powers to convince the government to improve their situation, an unlikely outcome given the government’s low economic power. Clinicians also hoped the Carter Center—perhaps alongside other INGOs—could facilitate a continuous supply of psychotropics, so they could better help patients (Interview 24).

Because the clinicians’ weak moral and epistemic power brought little influence, they tapped the “weapons of the weak” (Scott, Reference Scott1987). Some grumbled about program expectations, an action that seemed to undercut the INGO’s moral and network power (Interview/FGD 18). Others minimized their presence at their posts, as one government official explained: “A person wanting employment will agree to go to Maryland [County].Footnote 4 They’re employed there… and they’re beginning to get a salary. But they will just leave and come back to Monrovia without saying anything” (Interview 7). Still others left to take positions with one of the many donor health programs needing trained personnel (Interviews 5, 17/FGD, 18/FGD, 19, 37), although it was impossible to verify how widespread noncompliance and exit were, multiple respondents mentioned them. A paradoxical outcome emerged: A program intended to build public health capacity by giving workers knowledge on mental health undermined that capacity as disgruntled clinicians exited their posts.

These challenges led the government and INGO to look for alternatives. Recognizing that its dearth of economic power meant it could play a minimal institutional role in mental health, the government turned to the community, with one official concluding, “[Addressing mental health] takes community involvement because it doesn’t matter what you do in terms of rehabilitation, if affected people go back into the community and there is stigma …. definitely they are going to fall” (Interview 21). The INGO thought the government should demonstrate the commitment it had shown when the program began and, despite a tight budget, allocate more money to mental health since the country’s economy had grown since the war (Interviews 46, 52, 56). But INGO officials also knew that because they sought to support government priorities (Interview 52) and because government has institutional authority, they could not directly push budget allocations and policies to provide medications, trainings, and higher salaries, to reconstruct the psychiatric hospital (Interviews 1, 2, 5, 14, 23, 35, 37, 46, 52), or to combat the unemployment and widespread illegal drug access that contributed to poor mental health (Interviews 4, 12, 13, 18/FGD, 19, 28). Acknowledging that government priorities change and mental health was a low priority, the INGO supported the formation of a mental health service user advocacy group and provided it office space, internet access, and support for advocacy training. By 2022, the group had convinced the government to establish a mental health line in the budget and appropriate $50,000 (Interviews 15, 16). Although this was a first step, the funding was insufficient to adequately treat and care for all Liberians living with mental health disorders (Interviews 5, 9). The stakeholders’ divergent meanings and powers led to suboptimal outcomes.

The case generates broader lessons about how meaning-making by different stakeholders may affect development programs’ implementation and outcomes. First, it echoes Brown and Harman’s (Reference Brown and Harman2013) point that all development stakeholders have some agency to realize their objectives. Rather than being “acted on” by INGOs, governments and participants in low-income contexts are also “actors in” development; how they understand programs informs how they implement those programs. Second, the case shows that regardless of their various powers, INGOs depend on host-country governments to exercise institutional power to achieve their goals. Only governments have the legal right to approve government budgets, pass policies, or even allow an INGO to work in a country, and thus, how government officials understand programs matters. Third, meaning-making may involve wishful thinking, as stakeholders plan and implement programs based on their predictions about the future. INGO officials hoped that as Liberia continued its postwar rebuilding, the government would have more capacity and resources and that it would choose to spend those on mental health, including salaries, medications, and data collection (Interviews 3, 41). Making sense of the program’s sustainability depended on this expectation.

Conclusion

This article has described how three stakeholders—Carter Center officials, host-country government officials, and mental health practitioners—made meaning of the Liberian Mental Health Program and how those meanings intertwined with various forms of power. The INGO personnel understood the program in terms of personal ties to Liberia, the virtuous nature of the work in a postwar context, and the INGO’s expertise in mental health and workforce development, meanings linked to network, moral, and epistemic powers. Liberian government officials understood the program to be government directed, but also an expensive endeavor that competed with other health issues for precious state resources. While they had institutional authority over the program, they lacked the economic power to continue trainings, provide adequate compensation for personnel, or ensure sufficient psychotropic medication access. They relied on the INGO’s virtuous engagement and assumed economic resources, although the INGO also had insufficient economic power to meet all these expectations. The mental health clinicians understood the program not only as a way to express virtue, but also as an avenue for respect, expertise, and economic advancement. The government’s low economic power and the INGO’s lack of institutional power made aligning these various meanings problematic. Without sufficient epistemic or moral power to shape policies, some clinicians exercised the powers of noncompliance or exit. After 12 years, stakeholders’ inability to coalesce around shared meanings (each undergirded by various powers) was evident in a program that seemed unable to move from trainings to address the structural obstacles to providing mental health care for Liberians needing it.

This article raises questions for future research. First, we studied a program with a dozen-year history, but most development projects are more short term. Could stakeholders’ shared or divergent meanings be a function of time, particularly as INGO or government personnel change? Second, we examined a highly stigmatized and widely ignored issue. Would stakeholders be more likely to share meanings on programs that addressed a highly salient issue (e.g., food insecurity) or would saliency lead to greater divergence in meanings among actors and exacerbate power differences? Third, what factors are needed for stakeholders to share program meanings? Do the almost inevitable power differentials among program stakeholders necessarily lead to divergent meanings? Finally, given research illustrating how mental health is a significant cause of mortality (Walker et al., Reference Walker, McGee and Druss2015), what factors might lead governments to use that information to make new meanings around health priorities? Answering such questions could inform the stakeholder relationships needed to aid program beneficiaries, including people suffering mental illnesses in aid-dependent countries.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Carter Center for logistical support in Liberia. For thoughtful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript, we thank Catherine Worsnop and two anonymous reviewers.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the study conception, design, data collection, and analysis. Both authors drafted and revised the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Tulane University School of Liberal Arts Faculty Research Fund [to M.A.C.] and the University of the South Faculty Research Fund [to A.S.P.].

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Ethics Approval

This study received Institutional Review Board approval from the University of the South [1607 515-1], Tulane University [2020-895], and the University of Liberia [22-04-313].

Consent and Data

All respondents were promised anonymity and confidentiality. All signed a written informed consent. Because of ethical concerns and promises of anonymity and confidentiality, the data for this project cannot be shared publicly.