Introduction

Welwitschia mirabilis Hook.f. is a remarkable gymnosperm endemic to the Namib Desert, ranging from central Namibia to southern Angola. This “living fossil” (Jürgens et al. Reference Jürgens, Oncken, Oldeland, Gunter and Rudolph2021) is the only extant species in the Welwitschiaceae family, order Gnetales. Welwitschia is particularly notable for its unusual morphology (Figure 1A–C) and its two indeterminately growing foliage leaves, which are never shed and represent the longest-lived leaves of any plant (Henschel and Seely Reference Henschel and Seely2000). As it develops a caudex rather than a conventional trunk, and lacks true branches, Welwitschia has been referred to as an acephalous plant (Bornman Reference Bornman1977; van Jaarsveld and Pond Reference Jaarsveld and Pond2013).

Figure 1. Photographs of representative Welwitschia mirabilis individuals, bearing cones, representing three size classes. The plants are ordered from (A) small, to (B) medium, and to (C) very large.

In young plants, morphology is relatively simple, with two distinct lobes and a meristem at the center of each lobe (Figure 1A–B). The shoot apex is gradually overgrown by surrounding caudex tissue, and the apical meristem dies shortly after germination, creating a closed growth system (Bornman Reference Bornman1977). The basal meristem encircles the caudex and produces the two leaves and reproductive organs (cones) (Figure 1A). After the apical meristem dies, vertical growth ceases, and subsequent expansion occurs primarily through lateral widening of the lobes. Apparent vertical distortion arises from asymmetric lateral growth and differential tissue deposition, gradually producing the obconical shape of the caudex. Continued asymmetrical growth eventually forms a multi-lobed, amorphous structure (Figure 1C). This complex growth pattern complicates identification of the oldest tissues, estimation of maximum lifespan, and selection of appropriate samples for radiocarbon (14C) dating.

Welwitschia does not develop growth rings and therefore cannot be dated using dendrochronological methods. Its caudex contains a fibrous, corky interior with scattered vascular bundles of xylem and phloem encased in a sclerified cortex, which precludes coring for age determination. Similar to other fibrous-stemmed plants such as palm trees, cycads, and tree aloes, plant size is generally the only available proxy for age, although most of these species are relatively fast-growing, so precise age determination is rarely necessary. African baobabs (Adansonia spp.) also have fibrous cores, but 14C dating has recently revealed sequential pith deposition, resulting in well-defined growth rings typically corresponding to one year or rainy season, that allows approximate age determination through coring (Patrut et al. Reference Patrut, Woodborne, Patrut, Rakosy, Lowy, Hall and von Reden2018). In some large baobabs, the oldest tissue can be found beneath the surface within hollow or fused stem sections, sometimes several hundred years old, illustrating that outer tissue age may not reflect continuous growth (Patrut et al. Reference Patrut, Woodborne, Von Reden, Hall, Patrut, Rakosy, Danthu, Pock-Tsy, Lowy and Margineanu2017). Although such methods are established for baobabs, their anatomy and growth patterns differ from Welwitschia, so these approaches are unlikely to be directly applicable to this species.

Welwitschia is exceptionally slow-growing. In 1960, in one of the earliest uses of 14C dating in southern Africa, an attempt was made to determine an age for a Welwitschia plant (Herre Reference Herre1961). Based on an age of “about 500–600 years” for an unspecified sample, Herre (Herre Reference Herre1961) proposed that by extrapolation the largest individual on the Husab Plains in Namibia may be around 2000 years old. That figure has been quoted ever since as a likely age for the largest Welwitschia plants and, as is the case with many other assumptions about Welwitschia, has been popularized into a mythical fact. There have been few attempts since Herre’s initial report to develop a system for determining likely ages of Welwitschia individuals (Crane and Griffin Reference Crane and Griffin1970; Jürgens et al. Reference Jürgens, Burke, Seely, Jacobson, Cowling, Richardson and Pierce1997; Vogel and Visser Reference Vogel and Visser1981). The oldest date retrieved from Welwitschia was reported as 920 ± 20 14C years (Crane and Griffin Reference Crane and Griffin1970), but the sampling strategy for this specimen was not provided in any detail. All previous studies aiming to determine the ages of Welwitschia plants have been conducted on living individuals by dating single samples. Problematically, no sampling methods have been described, and thus it is unclear whether the oldest tissue was actually analyzed. Hence, to date, no methodical approach has been described for radiocarbon sampling from Welwitschia.

In this study, we present a systematic approach to 14C dating in Welwitschia to maximize the likelihood of sampling the oldest tissue from a living individual and to examine vertical growth patterns through multiple age measurements. By carefully selecting specific locations within the caudex, including the outer caudex tissue, cortex, and central vascular regions, we aim to reconstruct an approximate growth history of a moderately large, dead individual plant. Precise knowledge of lifespan and growth rate in Welwitschia will enhance understanding of Namib Desert ecology and inform conservation strategies for this unique plant.

Methods

Sampling location

Welwitschia Wash is a ravine that runs towards the ephemeral Kuiseb River, located in the Namib-Naukluft National Park, 14 km east of Gobabeb Namib Research Institute (23°38’S, 15°10’E). The site is approximately 66 kilometers from the coast in the hyperarid Namib Desert. The Welwitschia Wash site is home to the southernmost population of approximately 165 Welwitschia individuals of varying sizes and presumably ages, with an even distribution of both sexes of this dioecious plant.

Sample description

In April to May 2021, researchers at Gobabeb recorded the death of a moderate sized Welwitschia plant located in Welwitschia Wash (Figure 2A). This population has been monitored since 1988, where this particular male was visited on a monthly basis to record leaf growth and reproductive state. A flash flood in October 2017 exposed part of its root where it was growing over rocky formations (Figure 2A), while domestic horses that were introduced in the area during the last 15 years have been browsing leaves in this population when no grazing is available. It appeared as though the root was damaged and severed by horses stepping on it, which resulted in this individual’s death. The death of this moderately sized individual offered a good opportunity to excavate (Figure 2B) and dissect a Welwitschia specimen, and to investigate its growth pattern using 14C.

Figure 2. Naturally deceased Welwitschia mirabilis individual removed from the field in Welwitschia Wash, Namibia. (A) In-situ position of the plant remains prior to removal. (B) The plant remains post-excavation. (C) Overview of the plant morphology; (D) Vertical measurement of the deceased individual, spanning approximately 30 cm from the top of the caudex to the border of the taproot. The tape measure indicates the approximate location of the slice used to create Section A, from which samples for the present study were taken. Marks on the measuring tape indicate length in centimeters.

Excavation process

The individual plant remains were collected in October 2022 by Gobabeb staff and the root was excavated to determine if it represented a taproot or if it was an extension of a root mass. The tap root pierced schist layers along a fault and measured 468 cm in length (Figure 2B) from the plant to where it was severed. The rest of the taproot was not excavated. The circumference of the leaf base (meristem) was measured to be 226 cm, consisting of two lobes of 112.4 cm and 113.8 cm, with a diameter of 65.5 cm and height of 24 cm (Figure 2C–D). No leaf fragments or reproductive structures remained on this individual (Figure 2A–D) due to persistent herbivore browsing prior to its death.

Sample collection

Given that Welwitschia plants obviously grow much more rapidly in the horizontal plane (Figure 2C), and more slowly in the vertical plane (Figure 2D), we designed the study to sample vertically so as to identify the oldest tissue with the smallest number of samples. At the Gobabeb Namib Research Institute, two intersecting cuts were made using a reciprocal saw, producing two lobe cross-sections. Section A (the section used in this study) is along the lobe’s midpoint (Figure 2D). To limit contamination, all surfaces were gently brushed to remove any loose material prior to manipulation and subsampling. A cork borer was used to core from the outer layer we refer to as “outer caudex tissue,” to the innermost corky material. Sample D was taken from the outer caudex region in the central depression between the two lobes (illustrated in Figure 3). Material samples were individually sealed in clean aluminum foil packets within plastic collection bags for storage.

Figure 3. Diagram of AMS dating results from plant Section A. Circle colors indicate locations and median calendar ages of sampled tissues. White circles and markings were applied with paint during sampling to assist with measurements. Dash black line indicates the estimated axis separating the stem and root tissues. Important anatomical features are indicated with arrows. Marks on the measuring tape indicate length in centimeters.

Sample preparation

For each location along the lobe, a scalpel was used to remove a ∼1-cm3 sample from the outer surface of the wood as well as from the interior region adjacent to the inner cork. Samples of outer caudex tissue, as well as the cork material in the lobe’s central interior were taken at specific locations (Figure 3). The outermost layer of the caudex tissue was avoided as it was very degraded and likely to be contaminated by matter of different ages, except for samples 2.1, which was sampled from the outermost layer (Figure S1).

Accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) measurements and calibration

All samples underwent chemical pretreatment prior to radiocarbon dating. Specifically, an acid-alkali-acid (AAA) wash (Seiler et al. Reference Seiler, Grootes, Haarsaker, Lélu, Rzadeczka-Juga, Stene, Svarva, Thun, Værnes and Nadeau2019) was used to remove the soluble compounds from the sample while leaving the structural material of the plant. The pretreated fractions then underwent reduction and measurement at the National Laboratory for Age Determination in Trondheim, Norway (Nadeau et al. Reference Nadeau, Vaernes, Svarva, Larsen, Gulliksen, Klein and Mous2015; Seiler et al. Reference Seiler, Grootes, Haarsaker, Lélu, Rzadeczka-Juga, Stene, Svarva, Thun, Værnes and Nadeau2019).

The samples were measured against the Oxalic Acid II standard (NIST SRM-4990C), and the radiocarbon results were calibrated against the SHCal20 and Bomb 21 SH1-2 calibration curves using OxCal (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Heaton, Hua, Palmer, Turney, Southon and Bayliss2020; Hua et al. Reference Hua, Turnbull, Santos, Rakowski, Ancapichún, De Pol-Holz and Hammer2022). The OxCal code used for calculating the growth curve is provided in the Supplementary Material to ensure reproducibility.

Results and discussion

AMS results and calibrated ages

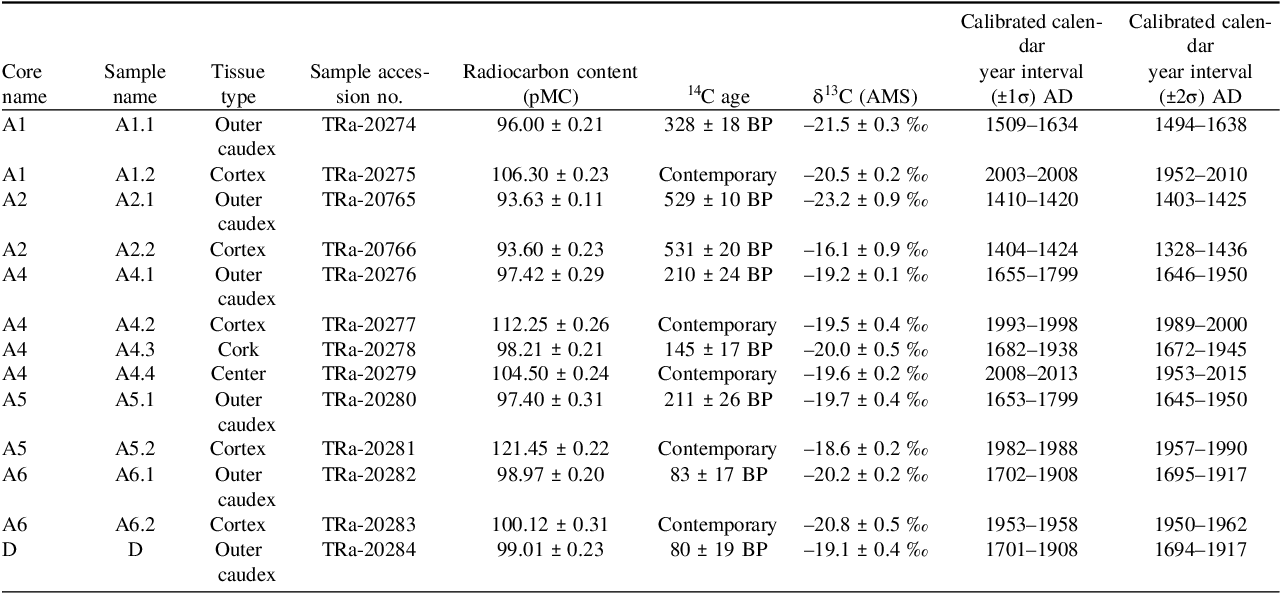

Calibrated date ranges, 14C ages for each sample are listed in Table 1. Probability distributions for sample calibrated dates are plotted in Figure 4A.

Table 1. AMS dating results, calibrated calendar ages, and tissue descriptions. The sample year is the calculated median of the calibration distribution calculated by OxCal

Figure 4. Growth patterns and estimated vertical growth rates. (A) Calibration plot of all radiocarbon measurements from the deceased Welwitschia plant. (B) Calibrated calendar age ranges for the outer bark calculated by an OxCal model for the plant growth using an age-depth model. The sample from the uppermost living part of the caudex/leaf base is assigned to the year 2021, the known year of the individual’s death. (C) Modeled growth of the plant based on the age model created by OxCal. The model indicates a growth rate that increased from 0.47 to 0.67 mm/year sometime in the first half of its lifespan.

Tissue-specific ages

While we primarily sampled along Section A, representing a segment of one of the lobes of the Welwitschia plant, we additionally collected a sample from the middle of the plant. This sample D, representing outer caudex tissue taken from the region in the central depression between the two lobes (i.e. the center of the plant, illustrated in Figure 3), yielded a relatively young date of 80 ± 19 14C years BP. This corresponds to an especially imprecise date in the 1680–1950 AD plateau. As such, the remaining dates were taken from samples taken from Section A of the lobe.

The outer caudex layer generally yielded the oldest dates, ranging from 83 ± 17 to 529 ± 10 14C years BP (Figure 3, Table 1). Sample A2.2, referred to as cortex tissue, was taken in close proximity to A2.1 (Figure 3), yielded an age of 531±20 BP, suggesting that both samples derive from the same outer caudex tissue material rather than independent tissues. Photographs of the sampled areas are provided to illustrate the layers and relative positions of A2.1 and A2.2 can be found in Figure S1. To clarify the distinction between these adjacent outer caudex tissue, sample A2.1 was collected entirely from the surface of the outer caudex tissue, while sample A2.2 was taken from beneath the cracked surface where the woody stem remained solid (Figure S1). The identical dates confirm the reproducibility of the radiocarbon results and support the interpretation that the outer caudex contains the oldest accessible tissue in this part of the lobe. That the outer caudex tissue provides the oldest dates is consistent with its role as protective tissue that dies and is deposited successively, similar to outer stem tissue in other perennial plants. In contrast, the cortex tissue appears to contain contemporary material, indicating that this layer remains living until the death of the individual (samples A1.2, A5.2, A6.2). Minor age variations among these samples likely reflect differences in sampling location, potentially living cells from the scattered vascular tissue, and the amount of material collected.

Sample A4.3, characterized by its corky texture, gave an age of 145 ± 17 BP. Although the core is fibrous, it consists of vascular bundles and sclerified tissue that is continuously deposited through meristematic activity at the apex. The cortex thickness is uneven (ranging from 1.25 cm to 3.97 cm in the stem), and deep fissures suggest irregular caudex growth, girth expansion, or possible microbial-induced or other damage. Hence, this cork tissue likely represents a mixture of older deposits and contemporary living tissue. The position of A4.3 between younger A4.2 and A4.4 complicates the possibility of resolving a simple radial growth model, as the sequence does not follow a consistent progressively younger outward pattern. With only one such radial transect available, we cannot test whether this pattern is consistent, and additional samples would be required to determine if A4.3 represents a true age inversion or simply local heterogeneity in cork deposition.

The center of the section, running from the roots to the leaf meristem are the vascular tissue (Figure 3), which yielded contemporary results as expected, due the the requirement that this tissue must be living while the plant remains alive. Overall, tissue ages progress from contemporary at the center to older at the outer caudex tissue. We conclude that meristematic tissue that dies in the stem center rapidly corkifies into a thin outer epidermis and a more substantial cortex, which is successively deposited as the girth expands.

It should be noted that our sampling strategy focused on identifying the oldest tissue accessible from living plants without harming them, rather than providing a comprehensive characterization of growth across all plant axes. For example, we did not sample the taproot, or other root structures, under the assumption that these structures represent living tissues. These limitations reflect the specific goals of this study and logistical and budgetary constraints. While a more comprehensive sampling strategy would yield a fuller understanding of Welwitschia growth patterns, our dataset provides a first approximation of tissue-specific ages and identifies the oldest accessible tissue in living plants.

Vertical growth pattern and rates

When considering the outer caudex tissue dates along the outer edge (left side in Figure 3) of Section A, there is a clear progression of age. A6.1 was found to be 83 ± 17 14C years BP, A4.1 was found to be 210 ± 24 BP and A2.2 was found to be the oldest tissue with an age of 531 ± 20 BP. A1.1, however, was found to have a date of almost 200 14C years less than A2.2, at 328 ± 18 BP. The age difference between the outer caudex tissue samples from A2.2 and A1.1 indicate that somewhere between these samples lies differing parts of the plants. A1.1 appears to derive from root tissue, which could have grown more recently than A2.2, indicating that the oldest part of the plant, in terms of vertical growth, lies somewhere between the root and stem tissue.

Moreover, based on the dates from samples A4.1 and A5.1, it is apparent that the adaxial (A5) and abaxial (A4) sides of each lobe grow symmetrically on either side of the basal meristem. Sample D, collected from the central depression between the two lobes, does not lie along the same adaxial–abaxial axis and therefore is not used to assess symmetry. Symmetry in tissue ages is thus only observed along the outer caudex tissue based on paired adaxial and abaxial samples in a single lobe.

Given the unique morphology of Welwitschia and its extremely slow growth as well as the uncertainty of the radiocarbon measurements, it is not possible to use standard tree growth rate formulas, e.g. (Stephenson et al. Reference Stephenson, Das, Condit, Russo, Baker, Beckman and Coomes2014). Moreover, Welwitschia’s overall size does not fluctuate noticeably between dry and rainy seasons. Instead, growth appears nearly continuous and stable over time, although further long-term climate data would be needed to verify this. Vertical growth from the soil line to the leaf base was estimated using the vertical distance between the measured samples. The distance and corresponding radiocarbon dates of the outer caudex tissue were used to calculate an age model for the measured samples using OxCal (Figure 4B). As sample A4.1 lies in the plateau between 1680 and 1950 AD that cannot be well resolved with radiocarbon dating, the age of this sample has a large uncertainty. This contributes to the uncertainty of the plant’s growth rate.

Based on the model, vertical growth appears to have slightly increased from about 0.47 mm/year to approximately 0.67 mm/year around 1780 AD (Figure 4C), followed by a potential slowdown around 1840 AD, which may be an artifact of the modeling due to limited sample size and large uncertainty of the radiocarbon dates in the period 1680–1950 AD. These small fluctuations could reflect environmental conditions, plant health, or local substrate, but given the limited data, they remain speculative and the resolution of short-term or subtle changes in vertical growth is limited. While the data are consistent with near-linear vertical growth from the soil line to the leaf base, minor fluctuations cannot be statistically confirmed. Therefore, the model provides a first approximation of the relationship between tissue age and plant size along the vertical axis, allowing identification of the oldest parts of the plant, rather than a fully resolved growth curve. The determined growth rate can likely not be generalized to other plant individuals as environmental conditions and other factors might affect the growth.

Conclusion

In this study, we present the first systematic attempt at radiocarbon dating of Welwitschia mirabilis, a species that is renowned for its longevity. We provide preliminary vertical growth rates for a moderately sized Welwitschia mirabilis individual with a meristematic circumference of only 226 cm, whereas in the same population there are many other considerably larger living individuals of both sexes. Surprisingly, the likely age of this relatively small plant was determined to be 531 ± 20 14C years, corresponding to the period 1420–1440 AD. Based on the current dates, the oldest tissue in Welwitschia appears to be the outer caudex tissue located at the lobe center, near the stem base just above the root at ground level. Moreover, the tissue becomes younger immediately below the outer caudex surface. The age of the plant progresses from the base of the stem with the contemporary tissue at the tip/leaf base. This finding, that the outer caudex tissue represents the oldest tissue, means that no coring or harmful sampling would be required to collect samples for radiocarbon dating from living individuals. However, given that the oldest tissue is external, it may be that there are only low chances of retrieving the true oldest material remaining on the largest (and oldest) individuals. Irregular caudex expansion, deformation and centuries or even millennia of exposure to their harsh desert environment would likely lead to sparse preservation and eventual erosion of the outermost outer caudex tissue.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2025.10185.

Acknowledgments

Sampling for this project was performed under research permits (RPIV009282022) granted by the National Commission on Research, Science and Technology in Namibia. The authors are grateful to Namibia’s Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism for allowing the research in the Namib Naukluft National Park and for granting access to samples. The research was supported by a 2023 award from the Peder Sather Foundation and award 1054 (“Establishing Welwitschia mirabilis as a model plant to explore longevity and biological aging”) from the Nansen Foundation. We thank Gobabeb staff Samuel Gowaseb, Richard Swartbooi and Ulrich Bezuidenhoudt for their work excavating the plant used in this study. We also thank Eirik Sollid, John Hårsaker, Mats Aspvik and Wendy Khumalo from the National Laboratory for Age Determination for help with sample preparation. Finally, we offer a special word of appreciation for the generations of researchers, technicians, and interns that continue to monitor and observe the Welwitschia populations near Gobabeb.