Introduction

Language disturbances are increasingly understood as complex phenomena that cut across traditional diagnostic boundaries, affecting both affective disorders (e.g., major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar disorder (BD)) and psychotic disorders (e.g., schizophrenia (SZ), schizoaffective disorder (SZA) – collectively referred to as schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSD)). Beyond clinical symptoms, language impairments are associated with social withdrawal, reduced life satisfaction, and poorer functional outcomes [Reference Nettekoven, Diederen, Giles, Duncan, Stenson and Olah1]. Formal thought disorder (FTD), referring to impairments in thought and language, has been shown to negatively impact psychosocial quality of life, highlighting the need to address cognitive–linguistic deficits [Reference Tan, Thomas and Rossell2]. Similarly, even when clinically stable, patients report social functioning impairment, underscoring the importance of identifying barriers to full psychosocial recovery [Reference Høegh, Melle, Aminoff, Olsen, Lunding and Ueland3]. FTD includes positive (e.g., disorganization) and negative (e.g., poverty of speech) dimensions. It is noteworthy that the prevalence of FTD is often overlooked in MDD, albeit with prevalence rates up to 53%. In SZ and BD, rates reach up to 81%, while in SZA up to 60%. Moreover, FTD likely exists on a continuum with normal speech, as evidence of it has been observed in 6% of healthy controls (HC) [Reference Roche, Creed, MacMahon, Brennan and Clarke4].

FTD has been the most studied in SSD, typically manifesting as derailment, incoherence, or neologisms but also as reduced speech production with increased response latencies and blocking [Reference Roche, Creed, MacMahon, Brennan and Clarke4–Reference Sumner, Bell and Rossell7]. In MDD, findings point out to increased response latencies, diminished verbal output, and a tendency toward negatively valenced language [Reference Kircher, Bröhl, Meier and Engelen5, Reference Stein, Buckenmayer, Brosch, Meller, Schmitt and Ringwald8]. Across disorders, FTD severity has been linked to relapse, (re-)hospitalization, and impaired psychosocial functioning [Reference Roche, Creed, MacMahon, Brennan and Clarke4, Reference Wilcox, Winokur and Tsuang9]. Recent studies emphasize the transdiagnostic nature of FTD. Stein et al. [Reference Stein, Buckenmayer, Brosch, Meller, Schmitt and Ringwald8] have identified a three-factor model (disorganization, emptiness, and incoherence) across affective and psychotic disorders, replicated by Tang et al. [Reference Buciuman, Oeztuerk, Popovic, Enrico, Ruef and Bieler10], who used different FTD rating scales and patients. A further study applying different clustering algorithms in recent onset psychosis (both affective and psychotic) showed two FTD subtypes, i.e., high FTD versus low FTD [Reference Buciuman, Oeztuerk, Popovic, Enrico, Ruef and Bieler10]. Most recently, this approach was expanded to a large sample of affective and psychotic disorders across different illness stages. Using a model-based cluster analytic approach, four subtypes ranging from minimal to severe FTD were identified with clinical diagnoses to be distributed across all of them [Reference Stein, Gudjons, Brosch, Keunecke, Pfarr and Teutenberg11].

Given the prevalence of FTD across diagnoses and the growing evidence of its transdiagnostic nature, it becomes clear that studying FTD and speech disturbances beyond traditional diagnostic categories is essential for a deeper understanding of their association with cognition, communication, and daily functioning. By focusing on shared mechanisms rather than on disorder-specific symptoms, a transdiagnostic perspective facilitates the identification of universal and overlapping language-related alterations. This approach is particularly advantageous in addressing comorbidity, which is a prevalent challenge in psychiatry. Traditional diagnostic boundaries, such as those defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; [Reference Stein and Kircher13]) or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD; [Reference McTeague, Goodkind and Etkin14]), often fail to capture the shared mechanisms underlying different disorders [Reference Fusar-Poli, Solmi, Brondino, Davies, Chae and Politi12, Reference Stein and Kircher13]. For example, dysregulated cognitive and emotional processes, including rumination, impaired executive function, and semantic network disturbances, are common across disorders like SSD, MDD, and BD [Reference Stein, Buckenmayer, Brosch, Meller, Schmitt and Ringwald8, Reference Fusar-Poli, Solmi, Brondino, Davies, Chae and Politi12, Reference McTeague, Goodkind and Etkin14–Reference Stein, Schmitt, Brosch, Meller, Pfarr and Ringwald19].

Traditional FTD assessments, such as the Scale for the Assessment of Thought, Language, and Communication (TLC; [Reference Andreasen20]), the Scale for the Assessment of Objective and Subjective Formal Thought and Language Disorder (TALD; [Reference Kircher, Krug, Stratmann, Ghazi, Schales and Frauenheim21]), and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS; [Reference Corcoran, Mittal, Bearden, Gur, Hitczenko and Bilgrami25]), are clinically useful but limited by scalability and subjectivity [Reference Palaniyappan, Wang and Meister22]. Therefore, natural language processing (NLP) provides an advanced and highly sensitive methodology for detecting and analyzing language impairments across multiple linguistic domains. By facilitating an objective, scalable, and systematic assessment of linguistic features, including syntax, semantics, and morphology, NLP offers a powerful tool for uncovering subtle language abnormalities [Reference Bedi, Carrillo, Cecchi, Slezak, Sigman and Mota23–Reference He, Palominos, Zhang, Alonso-Sánchez, Palaniyappan and Hinzen28]. Applying NLP-based methods to spoken language, studies have predominantly focused on SSD patients [Reference Corcoran, Mittal, Bearden, Gur, Hitczenko and Bilgrami25], with only some examining MDD [Reference Koops, Brederoo, de Boer, Nadema, Voppel and Sommer29]. In addition, only a few have investigated NLP metrics across multiple psychiatric disorders at the same time [Reference Schneider, Leinweber, Jamalabadi, Teutenberg, Brosch and Pfarr30, Reference Schneider, Alexander, Jansen, Nenadić, Straube and Teutenberg31]. In SSD, syntax-focused measures, such as reduced clause complexity and diminished syntactic diversity, have been linked to working memory deficits and impaired executive functioning [Reference Corona Hernández, Corcoran, Achim, De Boer, Boerma and Brederoo26, Reference Fraser, King, Thomas and Kendell32–Reference Kuperberg36]. In MDD, computational methods have revealed increased usage of first-person pronouns and negative affective language, reflecting heightened self-focus and cognitive distortions [Reference Tackman, Sbarra, Carey, Donnellan, Horn and Holtzman37–Reference Brockmeyer, Zimmermann, Kulessa, Hautzinger, Bents and Friederich40].

Nevertheless, the interrelationship between different NLP-derived metrices and other domains, including cognition and psychopathology, remains poorly understood [Reference Palaniyappan, Wang and Meister22]. In this context, network analysis offers a powerful framework to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the complex architecture of both distinct and shared underlying mechanisms. Unlike traditional linear models, network approaches enable both the visualization and quantification of complex, multidimensional interactions [Reference Peralta, Gil-Berrozpe, Librero, Sánchez-Torres and Cuesta41]. In the context of NLP, network analysis serves as a powerful complementary tool, particularly for modeling the intricate dependencies between linguistic patterns, psychopathological features, and cognitive dysfunctions. This synergy enables the identification of meaningful associations that might otherwise remain undetected when using standard linguistic feature extraction or classification methods alone. In psychosis research, network methods have been used to analyze semantic and syntactic disruptions and their links to symptoms [Reference Nettekoven, Diederen, Giles, Duncan, Stenson and Olah1, Reference Ciampelli, de Boer, Voppel, Corona Hernandez, Brederoo and van Dellen34]. By analyzing spontaneous speech from SSD, MDD, and HC using syntactic measures and network analyses, Schneider et al. [Reference Schneider, Leinweber, Jamalabadi, Teutenberg, Brosch and Pfarr30] found that SSD patients exhibit significantly reduced syntactic complexity and diversity. Lower complexity was associated with more severe symptoms and cognitive deficits, while network analyses highlighted distinct roles for complexity and diversity in language processing [Reference Schneider, Leinweber, Jamalabadi, Teutenberg, Brosch and Pfarr30]; however, this study extracted syntactic features manually instead of using NLP. Prior research has also linked semantic network alterations to the severity of thought disorder symptoms in psychosis. Nettekoven et al. constructed semantic speech networks from transcribed language, showing that their structure correlates with disorganized thinking [Reference Nettekoven, Diederen, Giles, Duncan, Stenson and Olah1].

Previous studies often applied either NLP or network analysis in isolation. Notably, Chavez-Baldini et al. used a transdiagnostic network approach to examine symptom interactions over time, identifying central roles for self-perception and suicidal ideation [Reference Chavez-Baldini, Verweij, de Beurs, Bockting, Lok and Sutterland17, Reference Chavez-Baldini, Nieman, Keestra, Lok, Mocking and De Koning42]. Combining the methods of NLP and network analysis in a transdiagnostic perspective is rare [Reference Arribas, Barnby, Patel, McCutcheon, Kornblum and Shetty43]. More recently, Arribas et al. combined NLP and temporal network analysis to study prodromal symptoms across disorders, showing highly interconnected networks with minor differences between diagnoses [Reference Arribas, Barnby, Patel, McCutcheon, Kornblum and Shetty43].

Despite these advances, the field remains limited by small samples, manual linguistic annotation (e.g., [Reference Schneider, Leinweber, Jamalabadi, Teutenberg, Brosch and Pfarr30]), and diagnosis-specific designs. To address these gaps, this study integrates NLP and network analysis in a transdiagnostic framework and investigates latent linguistic variables in spoken language across individuals with SSD, MDD, BD, and HC within a German-speaking sample. Specifically, we aim to (1) extract linguistic features on various linguistic levels in spontaneous speech, (2) compare spontaneous speech performance across diagnostic and HC groups, (3) explore the relationship between language, language-related cognition, and psychopathology, and (4) identify domain-specific and cross-domain connections in a transdiagnostic network analysis approach. To explore interplay patterns, analyses included 28 linguistic variables (covering numerous linguistic levels), 10 psychopathological variables, and 6 cognitive function variables. Examining their associations is crucial, as these domains are intricately interconnected, with language serving as both an expression and diagnostic tool for cognitive and psychological processes, while cognitive functions influence linguistic abilities and psychopathological states [Reference Rude, Gortner and Pennebaker44–Reference Trifu, Nemeș, Bodea-Hațegan and Cozman46].

Methods

Participants

We included N = 372 German-speaking participants (n = 119 MDD, n = 27 BD, n = 48 SSD, and n = 178 HC) (cf. Table 1) from the FOR2107 cohort (see [Reference Kircher, Bröhl, Meier and Engelen5], www.for2107.de). Participants were aged between 18 and 67 years and fluent in German. Patients were recruited from the university hospital in Marburg and healthy controls via public advertisement. During a semi-structured clinical interview, diagnoses were acquired according to DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders (SCID-I; [Reference Wittchen47]). Trained staff assessed multiple psychopathological rating scales. The patient sample covered a broad range of illness phases, from acute to chronic to remitted states. Exclusion criteria for all participants included neurological or serious medical conditions, verbal IQ <80, and current substance abuse or dependence, or benzodiazepine intake. All participants provided written informed consent, and procedures were approved by the local ethics committees in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

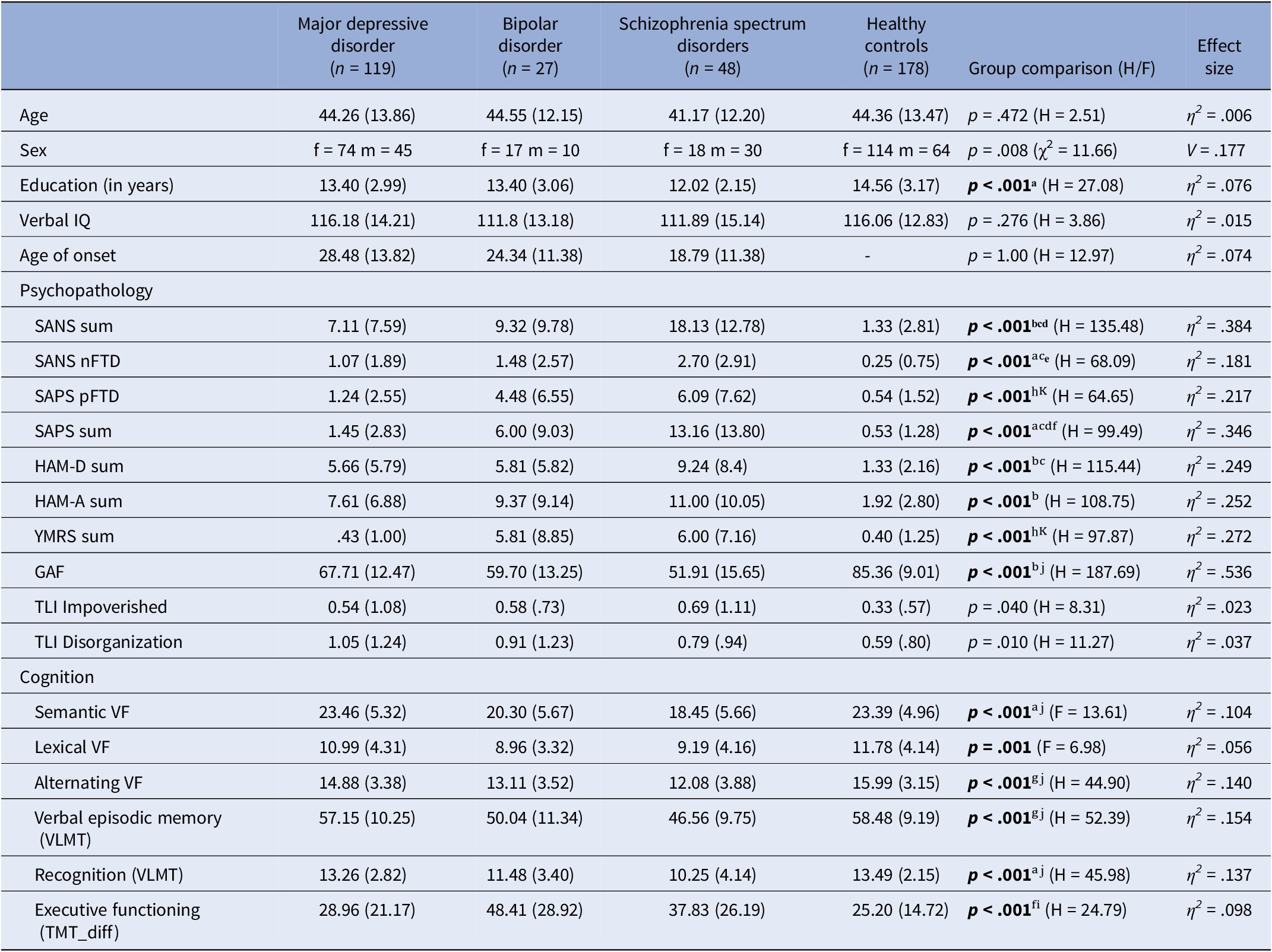

Table 1. Sample characteristics, N = 372; n = 178 healthy controls and n = 194 patients

Note: Means (standard deviation); SANS scale for the assessment of negative symptoms [Reference Andreasen51], SAPS scale for the assessment of positive symptoms [Reference Andreasen52], HAM-D Hamilton rating scale for depression [Reference Hamilton48], HAMA Hamilton anxiety rating scale [Reference Hamilton49], YMRS Young mania rating scale [Reference Young, Biggs, Ziegler and Meyer50], GAF global assessment of functioning [Reference Wittchen47], TLI Thought and Language Index [Reference Liddle, Ngan, Caissie, Anderson, Bates and Quested58], VF verbal fluency (RWT; [Reference Aschenbrenner, Tucha and Lange56]), VLMT Verbal Learning and Memory Test [Reference Helmstaedter and Durwen54], TMT Trail Making Test [Reference Reitan55]. F = F-statistic from one-way ANOVAs; H = H-statistic from Kruskal–Wallis tests (used when ANOVA assumptions were not met); η2 = Eta-squared, an effect size measure for ANOVA, indicating the proportion of variance explained by group differences; V = Cramér’s V, an effect size measure for chi-squared tests, reflecting the strength of association between categorical variables.Post hoc correction for multiple testing (Bonferroni) with significant results in bold font.

ᵃ = HC > SSD. ᵇ = HC > MDD, BD, SSD. ᶜ = MDD < SSD. ᵈ = BD < SSD. ᵉ = HC > MDD. ᶠ = HC < BD. ᵍ = HC > BD, SSD. ʰ = MDD < BD, SSD. ⁱ = MDD < BD. ʲ = MDD > SSD. ᴷ = HC < BD, SSD.

Psychopathology and cognition assessment

Following the diagnostic assessment described above, symptom severity was assessed using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D; [Reference Hamilton48]), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A; [Reference Hamilton49]), Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS; [Reference Young, Biggs, Ziegler and Meyer50]), and the Scales for the Assessment of Negative and Positive Symptoms (SANS; [Reference Andreasen51], SAPS; [Reference Andreasen52]), including FTD subscales (i.e., positive FTD and alogia). Overall functioning was assessed via the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF; [Reference Wittchen47]). All interviewers were trained and had expertise in administering and scoring the rating scales. Interrater reliability was evaluated using the interclass correlation coefficient, yielding good average reliability of r > .86 across all scales. Cognitive testing focused on language-related measures [Reference Nagels, Fährmann, Stratmann, Ghazi, Schales and Frauenheim53], including verbal episodic memory (VLMT; retrieval and recognition [Reference Helmstaedter and Durwen54]). Executive functioning was assessed using the Trail Making Test (TMT; [Reference Reitan55]), and verbal fluency using the Regensburger verbal fluency test (RWT; [Reference Aschenbrenner, Tucha and Lange56]) across three conditions: semantic (category ‘animals’), lexical (initial letter ‘p’), and alternating verbal fluency (alternating categories ‘fruits’ and ‘sports’).

Speech data assessment

Spontaneous speech was elicited using four Thematic Apperception Test pictures [Reference Murray57], with three-minute storytelling per picture (~12 min speech). Participants were encouraged to elaborate using nondirective prompts. Speech was transcribed verbatim and preprocessed (e.g., removal of interviewer speech, timestamps, and special characters). Additionally, trained raters who were blind to diagnosis evaluated speech using the Thought and Language Index (TLI; [Reference Liddle, Ngan, Caissie, Anderson, Bates and Quested58]). For each picture and minute, eight items were rated: (i) poverty of speech; (ii) weakening of goal; (iii) looseness; (iv) peculiar word; (v) peculiar sentence; (vi) peculiar logic; (vii) perservation; and (viii) distractibility [Reference Liddle, Ngan, Caissie, Anderson, Bates and Quested58]. These items were summarized into the domains Impoverished and Disorganization, according to Liddle et al. [Reference Liddle, Ngan, Caissie, Anderson, Bates and Quested58].

Feature extraction using natural language processing

Linguistic variables were extracted from transcripts using Python (version 3.11) and spaCy, which is an advanced library particularly well suited for the German language (https://github.com/explosion/spaCy; https://spacy.io/models). We employed the German transformer pipeline (de_dep_news_trf-3.7.2), a transformer-based model that can more effectively capture and process contextual information (https://spacy.io/models). This model was utilized to extract predefined linguistic features across various linguistic levels [Reference Tang, Hänsel, Cong, Nikzad, Mehta and Cho59]. See Supplementary Material 1 and Supplementary eTable 1 for details on the extracted features.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.3.1). To investigate group differences between MDD, BD, SSD and HC, we used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by a post-hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. The Kruskal–Wallis test was employed when the assumption for parametric testing was not satisfied [Reference Kruskal and Wallis60] (cf. Table 1). The same procedure was conducted for the extracted linguistic features (cf. Table 2).

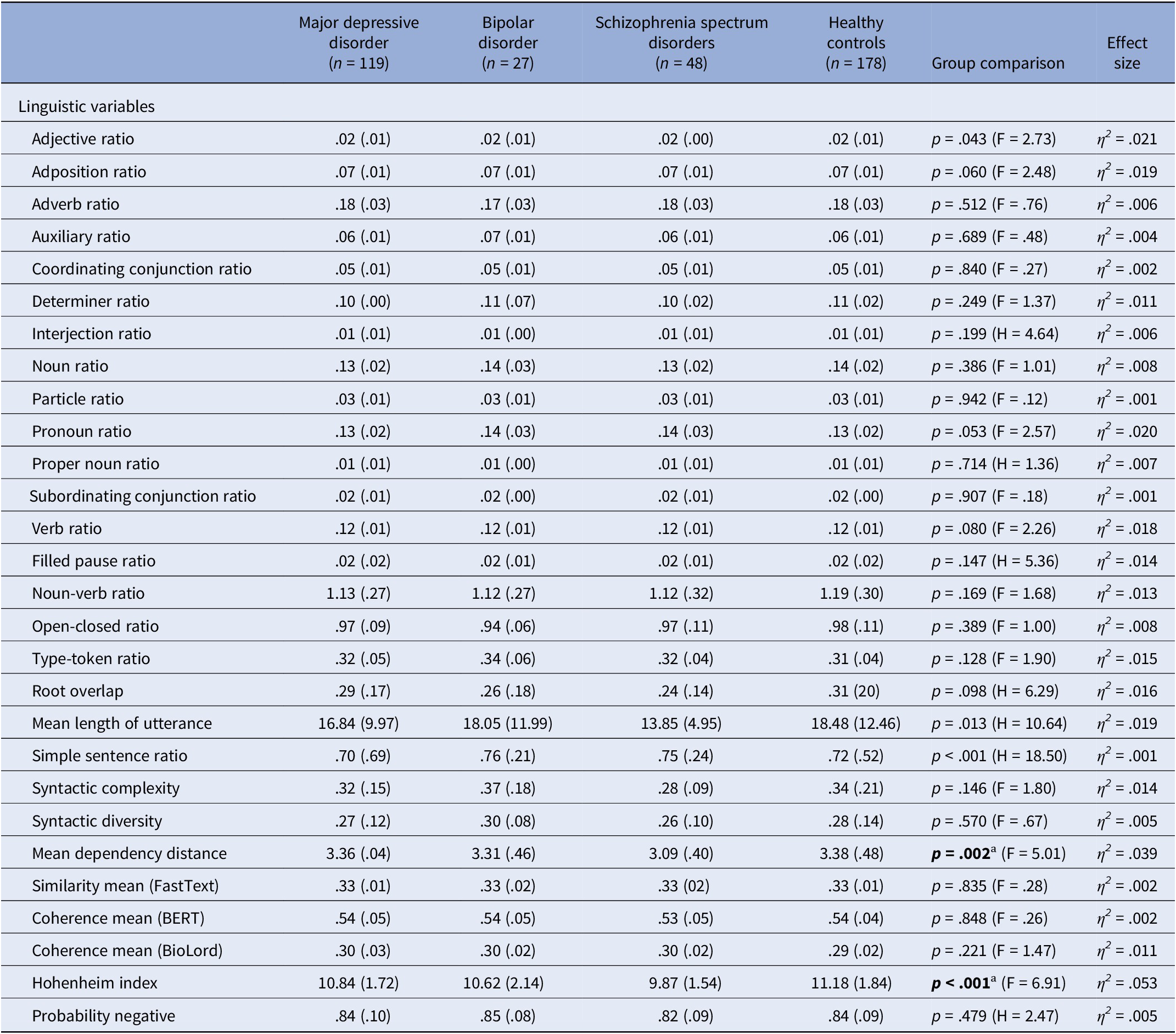

Table 2. Group comparison of extracted linguistic variables

Note: Means (standard deviation), F = F-statistic from one-way ANOVAs; H = H-statistic from Kruskal–Wallis tests (used when ANOVA assumptions were not met); η2 = Eta-squared, an effect size measure for ANOVA, indicating the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by group differences. Post hoc correction for multiple testing (Bonferroni) with significant results in bold font.

ᵃ = HC > SSD.

Next, we employed network analyses using R to investigate the structural and relational properties, aiming to elucidate patterns of interplay across linguistics, psychopathology, and cognition. Analyses included 28 linguistic variables (cf. Supplementary eTable 1), 10 psychopathological variables, and 6 cognitive variables (cf. Table 1). All variables were z-standardized. Networks were estimated using the Extended Bayesian Information Criterion Graphical Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (EBICglasso) method [Reference Tibshirani61, Reference Chen and Chen62], with a tuning parameter (γ) set at 0.5. This tuning parameter controls the balance between sparsity and sensitivity in edge selection, emphasizing the most robust associations, while reducing the inclusion of spurious edges, based on prior recommendations for psychological and behavioral data [Reference Foygel, Drton, Lafferty, Williams, Shawe-Taylor, Zemel and Culotta63, Reference Burger, Isvoranu, Lunansky, Haslbeck, Epskamp and Hoekstra64]. To assess the stability and robustness of the network structure, we conducted nonparametric bootstrapping with 1,000 permutations, generating confidence intervals for edge weights and evaluating network stability across resampled data. Insignificant edges were pruned to enhance network sparsity, retaining only stable and meaningful connections. Edges were classified as domain-specific (within linguistic, cognitive, or psychopathological domains) or cross-domain. Separate networks were estimated for (i) total sample (transdiagnostic), (ii) patients only, (iii) healthy controls only, (iv) each diagnostic group individually, and (v) the total sample excluding psychopathological variables as a supplementary analysis (Supplementary Material 3, Supplementary eTable 7–8).

To compare network structures, we employed the Network Comparison Test (NCT) from the NCT R package (version 2.2.2.). The NCT investigates network invariance by evaluating differences in overall network structures as well as global strength [Reference Epskamp and Fried65]. Test statistics and corresponding p-values were computed to determine whether the compared networks differed significantly. In addition to comparing healthy controls with the pooled patient groups, we conducted three pairwise NCTs to assess potential differences across diagnostic subgroups: MDD vs. BD, MDD vs. SSD, and BD vs. SSD. To account for multiple testing across edges, Bonferroni correction was applied to all p-values from the edge-specific comparisons. Additionally, Frobenius distances between group-level networks were calculated to quantify overall structural similarity [Reference Golub and Van Loan66].

Results

Sample characteristics

Demographic data are presented in Table 1. Group comparisons of the linguistic variables (Table 2) revealed several significant differences. SSD patients produced the simplest syntactic structures, BD patients showed the highest simple sentence ratio, and HC the most complex sentences. Adjective use differed significantly between groups, while pronoun use showed a trend. No significant group differences were found for the remaining linguistic variables (see Table 2).

Network analyses

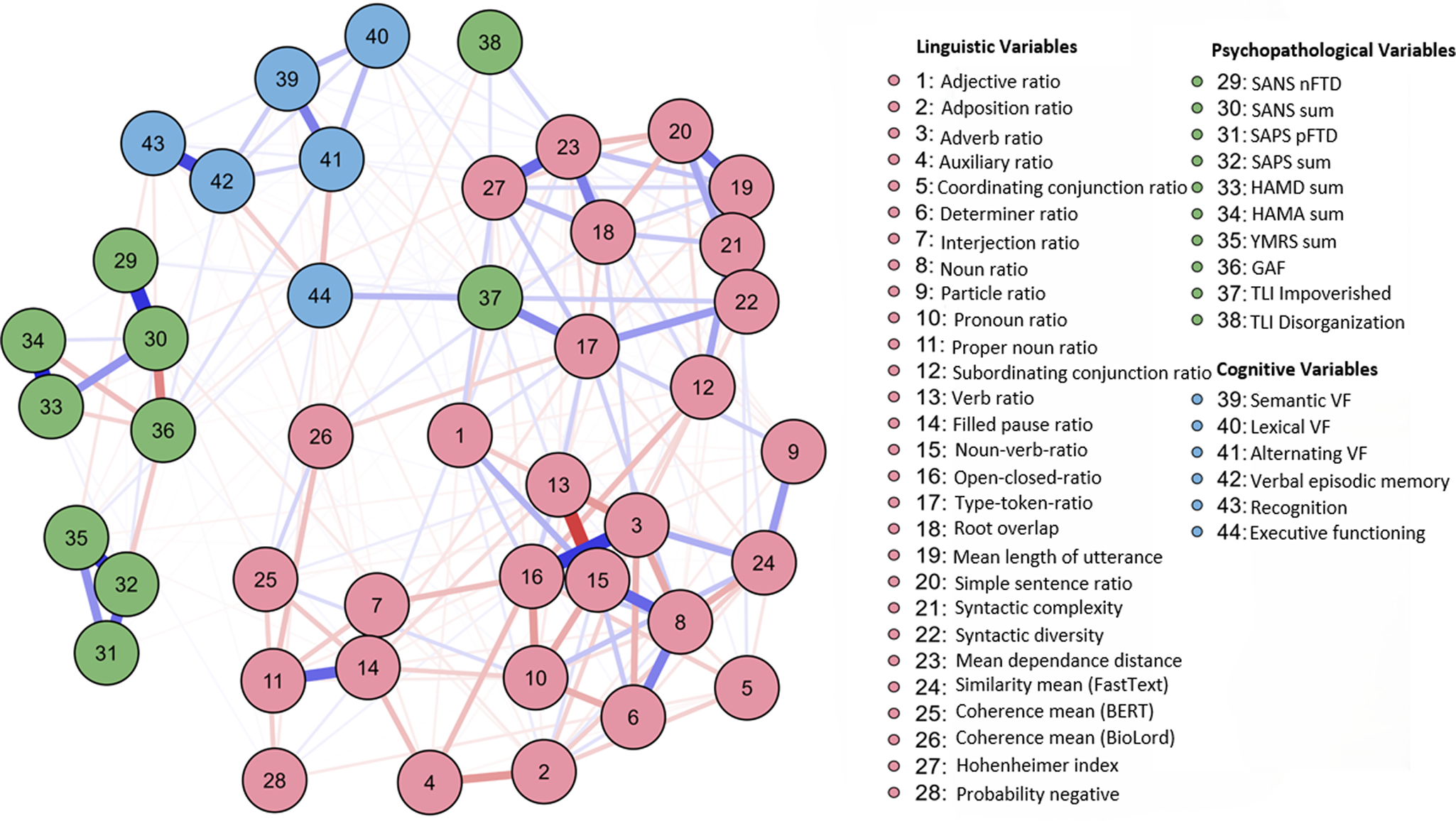

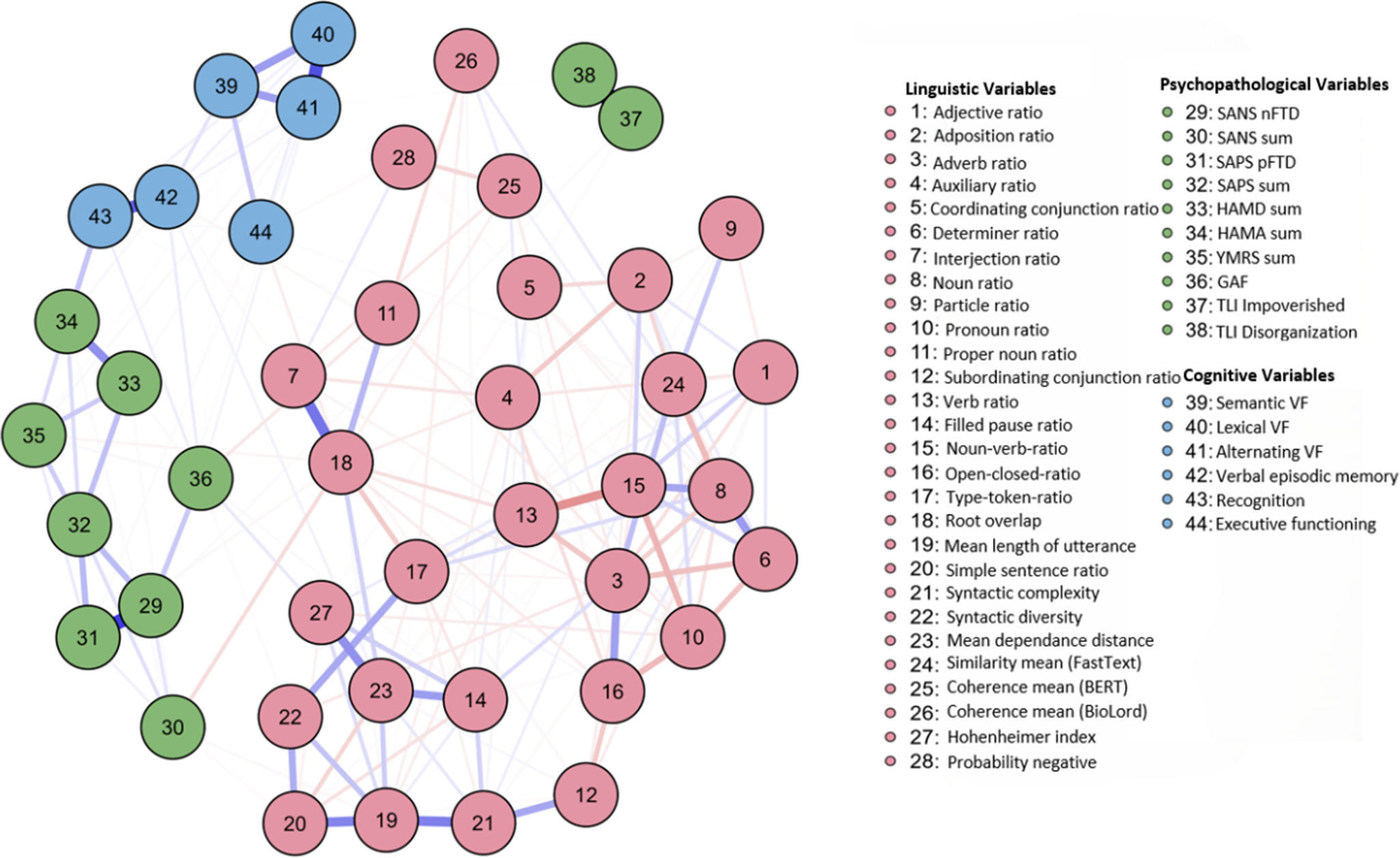

Network analyses were used to examine interaction patterns across linguistic, psychopathological, and cognitive domains. The full sample network included 44 nodes (28 linguistic, 10 psychopathological, and 6 cognitive) and was estimated via EBICglasso (γ = .5). In total, 282 of the 946 possible edges were non-zero (sparsity = .7019), indicating a relatively dense network (Figure 1). Maximum edge weight (EW) was .63.

Figure 1. Network plot over all participants (total sample). Note: Node color represents domain (green = psychopathological variables, blue = cognitive variables, red = linguistic variables). Edge color represents correlation (blue = positive; red = negative association). Edge thickness indicates strength of association. The maximum strength of the edges was .63.

Network clustering

The linguistic domain (red nodes) formed the most cohesive cluster, with high interconnections between variables reflecting lexical diversity, syntactic complexity, semantic coherence, and speech disfluencies. Notably, noun–verb ratio (NVR, no. 15) appeared as a central hub within this cluster. The psychopathological domain (green nodes) comprised a cohesive subgroup with limited cross-domain ties. Both TLI variables – TLI Impoverished (no. 37) and TLI Disorganization (no. 38) – diverged from this pattern: TLI Impoverished bridged the domains, while TLI Disorganization remained largely isolated. The cognition domain (blue nodes) showed strong domain-specific connections, especially among both VLMT variables (verbal episodic memory, no. 42; recognition, no. 43).

Edge strength and key connections

The strongest positive edge was observed between filled pause ratio (no. 14) and interjection ratio (no. 7; EW = .63), which is expectable for a verbalized thinking process. Additional prominent positive connections included verbal episodic memory and recognition (no. 42 and no. 43; EW = .56), HAM-D and HAM-A (no. 33 and no. 34; EW = .56), and adverb ratio with open–closed ratio (no. 3 and no. 16; EW = .52). The strongest negative edge emerged between verb ratio (no. 13) and NVR (no. 15; EW = -.50), underscoring their inverse relationship. Bridging variables across domains included executive functioning (no. 44), coherence mean (BioLord, no. 26), and TLI Impoverished (no. 37).

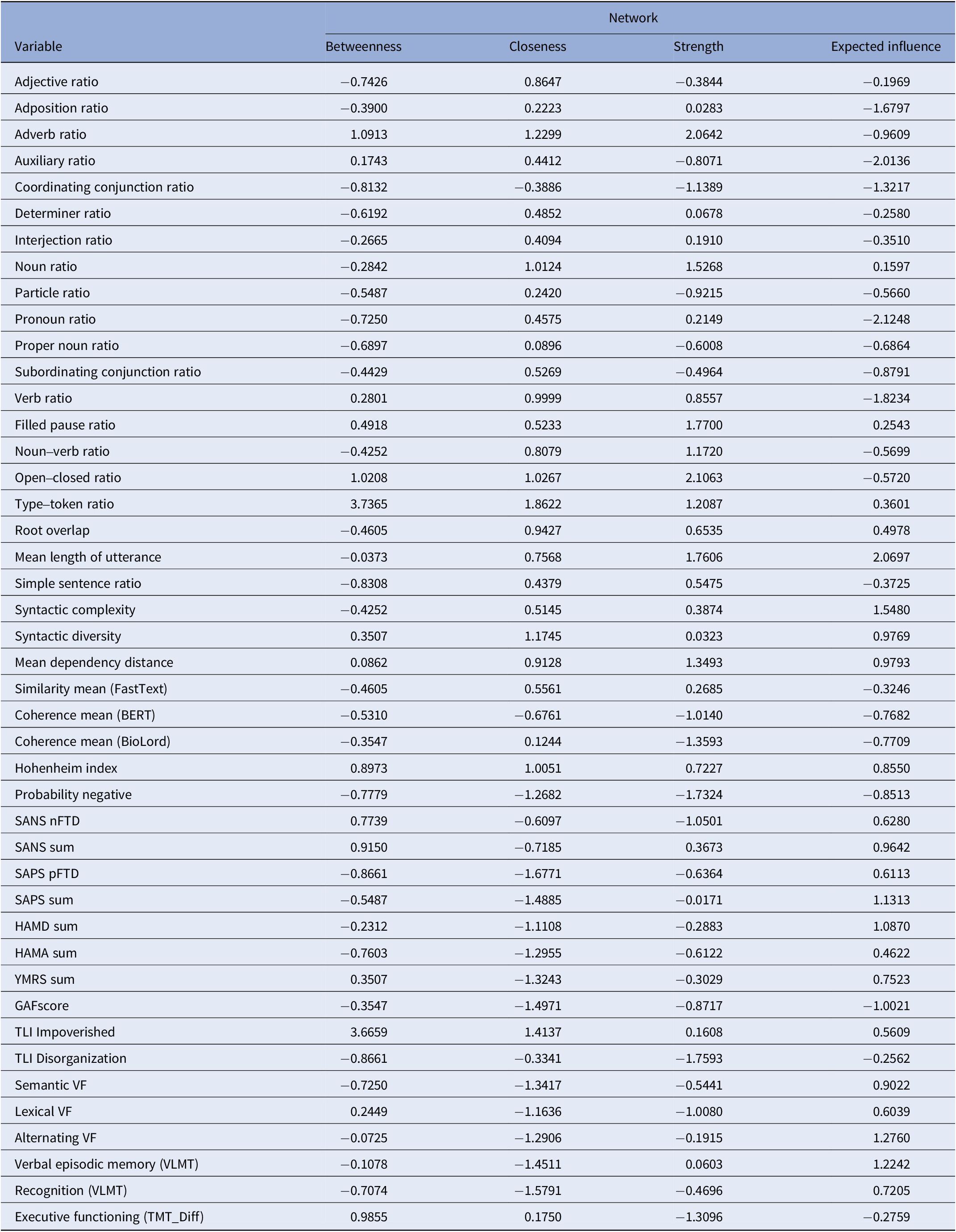

Centrality measures

The analysis of centrality measures revealed the pivotal roles of various variables. TLI Impoverished and type–token ratio (TTR) exhibited the highest betweenness, indicating strong integrative roles. Mean length of utterance (MLU), open-closed ratio, adverb ratio, and syntactic complexity showed the highest strength and expected influence, underlining their centrality in the network. SAPS (sum) and SANS (sum) revealed moderate expected influence, whereas HAM-D, HAM-A, and GAF were peripheral. Negative expected influence values were observed for several linguistic features (e.g., pronoun and auxiliary ratios), suggesting potential inhibitory associations. See Table 3 for detailed results.

Table 3. Centrality measures per variable (total sample)

Note: Betweenness = measures the extent to which a node lies on the shortest paths between others; closeness = reflects how quickly information spreads from a given node to others; strength = indicates the overall level of connectivity/influence a node has in the network; expected influence = combines edge weights and network structure to estimate a node’s potential impact on the network.

Network comparison

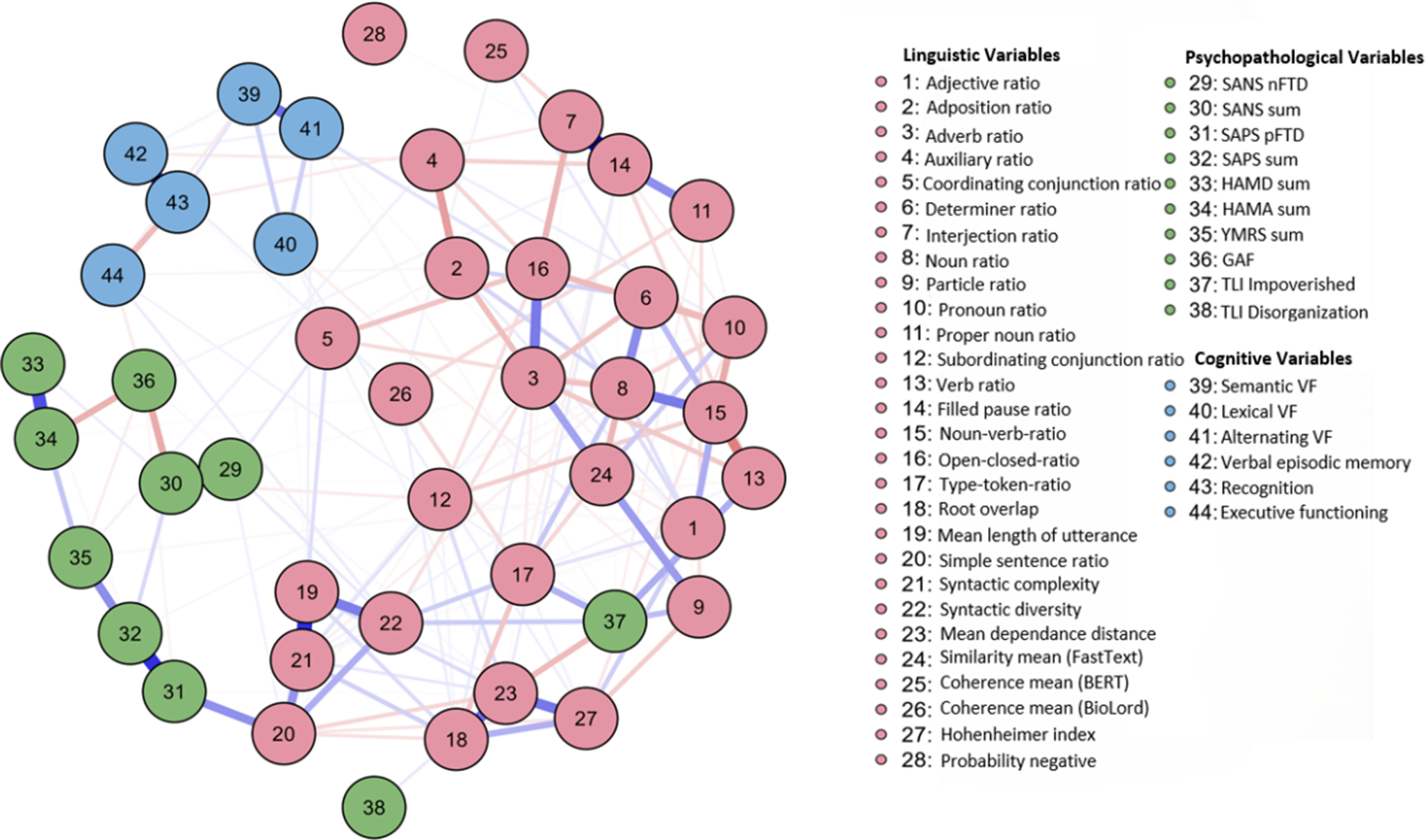

Figure 2 (network plot over all patients) and Figure 3 (network plot over all healthy controls) show network properties across healthy controls and patients separately. By employing the NCT from the NCT R package (version 2.2.2.), the networks’ structures of HC and patients were statistically compared. No significant differences were found in structure (M = 0.307, p = .335) or global strength (S = 1.329, p = .599), indicating structural invariance.

Figure 2. Network plot over all patients. Note: Node color represents domain (green = psychopathological variables, blue = cognitive variables, red = linguistic variables). Edge color represents correlation (blue = positive; red = negative association). Edge thickness indicates strength of association. The maximum strength of the edges was .51.

Figure 3. Network plot over all healthy controls. Note: Node color represents domain (green = psychopathological variables, blue = cognitive variables, red = linguistic variables). Edge color represents correlation (blue = positive; red = negative association). Edge thickness indicates strength of association. The maximum strength of the edges was .62.

Further NCTs comparing diagnostic subgroups revealed a significant structural difference between MDD and SSD networks (M = 0.63, p = .033) but not between MDD and BD (M = 0.63, p = .499) nor between BD and SSD (M = 0.00, p = 1.00). After Bonferroni correction, no difference remained significant. Global strength did not differ significantly across any pairwise comparisons (all p > .65). Complementary Frobenius distance analyses supported these results, showing generally low numerical dissimilarity between networks. Full results for the separate networks of HC and patients, measurements of the NCT analyses, and centrality measures presented separately for patients and HC are provided in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Material 2, Supplementary eTables 2–5; Frobenius results: Supplementary eTable 6).

Discussion

This study investigated the interplay between language, cognition, and psychopathology within a transdiagnostic sample of patients with affective (MDD, BD) and psychotic (SSD) disorders and HC, using network analysis. Findings revealed linguistic variables, particularly measures of diversity and complexity, such as noun-verb ratio, type-token ratio, and mean length of utterance, emerged as central nodes linking linguistic, cognitive, and psychopathological domains. Cognitive performance showed strong associations with language impairments, while coherence measures derived from NLP served as key mediators between linguistic and psychopathological variables. These results suggest that, despite significant group differences in symptom load, the fundamental relationships among language, cognition, and psychopathology remain stable across groups. This underscores the potential of language-based assessments for better understanding of psychopathology across disorders and its dimensionality.

Based on this study, several new insights emerge. First, group comparisons revealed subtle yet significant linguistic differences between diagnostic groups. Notably, SSD patients exhibited reduced syntactic complexity, dependency distance, and mean length of utterance, aligning with prior research [Reference Schneider, Leinweber, Jamalabadi, Teutenberg, Brosch and Pfarr30, Reference Çokal, Sevilla, Jones, Zimmerer, Deamer and Douglas67]. Conversely, BD and SSD groups demonstrated higher simple sentence ratios, possibly reflecting compensatory mechanisms or reduced cognitive load [Reference Voleti, Liss and Berisha68]. Given that other linguistic measures exhibited less pronounced group differences, the findings suggest shared cognitive mechanisms underlying these patterns. The observed linguistic disruptions align with existing evidence linking language impairments to cognitive deficits and psychopathology. For instance, reduced syntactic diversity and coherence in SSD reflect impaired executive function and semantic network disturbances [Reference Kircher, Bröhl, Meier and Engelen5, Reference Schneider, Alexander, Jansen, Nenadić, Straube and Teutenberg31, Reference Corcoran and Cecchi69]. Similarly, the association between linguistic markers and mood symptoms in MDD and BD supports prior research on self-referential and emotionally valenced language in these disorders [Reference Tackman, Sbarra, Carey, Donnellan, Horn and Holtzman37, Reference Brockmeyer, Zimmermann, Kulessa, Hautzinger, Bents and Friederich40].

Second, the findings of the network comparison suggest that the overall structure and global connectivity among linguistic, cognitive, and psychopathological variables did not significantly differ between patients and HC, nor across diagnostic groups, indicating that fundamental cross-domain relationships remain stable despite significant group differences in symptom load. This aligns with a dimensional perspective, suggesting that the structure of relationships among cognitive, psychopathological, and linguistic variables remains stable irrespective of categorical disease boundaries [Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff and Bagby70]. However, the more fragmented psychopathological domain in patients may indicate that psychiatric symptoms operate as more loosely connected constructs, aligning with research suggesting that psychopathology emerges from disruptions in broader cognitive networks rather than isolated deficits [Reference McTeague, Goodkind and Etkin14]. The presence of key linguistic bridging variables indicates potential compensatory mechanisms or structural differences in language organization. These results suggest that while linguistic patterns remain consistent, subtle differences in network connectivity may still contribute to individual variability in psychopathological expression. The network invariance across groups supports the notion that linguistic features play a central, dimensional role independent of a diagnosis and symptom load. The strong connections between linguistic variables in both groups underscore the stability of linguistic network architecture even in the presence of mental illness, without evidence for diagnosis-specific structural changes. Complementing these findings, additional within-patient analyses showed that despite subtle structural differences involving the MDD network, no robust, diagnosis-specific edges differentiate MDD, BD, and SSD, nor were any significant differences found in global strength. This pattern provides further support for a transdiagnostic, dimensional perspective, suggesting that the core architecture of symptom networks is largely shared across these major disorders. Diagnostic distinctions may therefore lie more in nuanced, higher-order network configurations than in specific symptom-to-symptom pathways. These findings align with dimensional and transdiagnostic models that conceptualize cognitive and linguistic impairments as shared mechanisms across various psychopathologies [Reference Kircher, Bröhl, Meier and Engelen5, Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff and Bagby70, Reference Hinzen and Palaniyappan71].

Third, network analyses provided insights into how language, cognition, and psychopathology interplay across diagnoses. Linguistic variables formed the most densely connected cluster across all groups, with measures, such as noun-verb ratio, type-token ratio, and mean length of utterance, acting as key nodes. This reinforces the centrality of linguistic features in understanding psychiatric disorders. Additionally, bridging variables like semantic coherence, executive functioning, and TLI Impoverished linked linguistic, cognitive, and psychopathological domains, highlighting their transdiagnostic relevance, which aligns with dimensional models of psychopathology that emphasize overlapping features across traditional diagnostic boundaries [Reference Chavez-Baldini, Verweij, de Beurs, Bockting, Lok and Sutterland17, Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff and Bagby70, Reference Huang, Liu, Zhang, Li, Wang and Hu72]. Semantic coherence, often reduced in psychotic disorders, reflects underlying thought disorganization [Reference Nettekoven, Diederen, Giles, Duncan, Stenson and Olah1, Reference Holshausen, Harvey, Elvevåg, Foltz and Bowie73]. Similarly, lexical complexity measures, such as mean length of utterance and type-token ratio, are central in characterizing language disruptions associated with affective and psychotic disorders [Reference Tang, Hänsel, Cong, Nikzad, Mehta and Cho59]. Linguistic patterns have been linked to neurocognitive mechanisms and may serve as early indicators of cognitive decline or psychiatric progression [Reference Hinzen and Palaniyappan71]. Importantly, impairments in semantics and syntax often precede full-blown clinical symptoms in SZ and MDD [Reference Bedi, Carrillo, Cecchi, Slezak, Sigman and Mota23, Reference Corcoran, Mittal, Bearden, Gur, Hitczenko and Bilgrami25, Reference Schneider, Alexander, Jansen, Nenadić, Straube and Teutenberg31, Reference Perlini, Marini, Garzitto, Isola, Cerruti and Marinelli74, Reference Silva, Limongi, MacKinley, Ford, Alonso-Sánchez and Palaniyappan75]. Cognitive deficits, particularly in executive functioning, strongly interact with psychopathology [Reference McTeague, Goodkind and Etkin14, Reference Cohen, McGovern, Dinzeo and Covington76, Reference Millan, Agid, Brüne, Bullmore, Carter and Clayton77]. Executive dysfunction, affecting planning, flexibility, and inhibition, is a key transdiagnostic feature across psychiatric disorders and emerged as a central link between cognitive, psychopathological, and linguistic variables [Reference McTeague, Goodkind and Etkin14]. Its association with TLI Impoverished suggests that language-related deficits may exacerbate broader cognitive impairments, aligning with dimensional models of psychopathology such as HiTOP [Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff and Bagby70]. Furthermore, cognitive impairments contribute to the persistence of negative symptoms in SZ and the recurrence of mood episodes in BD [Reference Cohen, McGovern, Dinzeo and Covington76, Reference Millan, Agid, Brüne, Bullmore, Carter and Clayton77]. The high centrality of linguistic variables highlights their relevance in psychiatric symptom networks. Decreased type-token ratio has been associated with cognitive and social dysfunction in SZ, while increased syntactic complexity may reflect compensatory mechanisms in affective disorders [Reference Schneider, Alexander, Jansen, Nenadić, Straube and Teutenberg31, Reference Tang, Cong, Nikzad, Mehta, Cho and Hänsel78]. These findings suggest that aspects of linguistic diversity and structure may serve as transdiagnostic markers of cognitive and functional impairments. Moreover, they could hold prognostic value concerning symptom severity and disease progression across psychiatric disorders, aligning with dimensional models of psychopathology [Reference Chavez-Baldini, Verweij, de Beurs, Bockting, Lok and Sutterland17].

In summary, the results indicate that linguistic networks remain stable across HC and psychiatric diagnoses, while psychopathological symptoms exhibit some structural variability. This underscores the importance of a dimensional and transdiagnostic approach that considers linguistic and cognitive mechanisms as common factors in mental disorders.

Limitations

Despite the notable sample size, several limitations should be acknowledged. As this study employed a cross-sectional design, conclusions regarding the longitudinal stability or causal direction of the observed associations cannot be drawn. The patient sample covered a broad range of illness phases from acute to remitted states, but highly acute patients could not be included due to practical constraints of participation during severe acute states. Future studies should employ longitudinal designs capturing different illness phases and symptom fluctuations to examine whether the identified linguistic, cognitive, and psychopathological associations remain stable over time or vary with changes in clinical states. Such approaches would also allow testing the predictive validity and temporal robustness of the present network structures.

The diagnostic distribution was unbalanced, with fewer participants with bipolar and psychotic disorders than with depression, which may limit generalizability. However, NCTs revealed no significant group differences, suggesting that core linguistic–cognitive–psychopathological patterns are shared across diagnoses.

Finally, speech data were derived from a single task (TAT, [Reference Murray57]), which restricted variability but ensured standardization. Additionally, psychopathological scales may not be equally sensitive or meaningful in HCs as they are primarily designed to capture clinical symptomatology in patients. To address this potential limitation, an additional network excluding psychopathological variables showed no differences from the original network (Supplementary Material 3, eTable 7–8).

Conclusion

This study highlights the intricate interplay of linguistic, cognitive, and psychopathological features, emphasizing their roles within a transdiagnostic framework. Results underscore the importance of integrating linguistic assessments into psychiatric evaluations and call for further exploration of the causal mechanisms underlying these associations.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2026.10151.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study can be accessed by contacting the corresponding author. All codes used for linguistic feature extraction and network analyses are available at https://github.com/NeuroSTA/NeuroSTA.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to all study participants and the research staff for their invaluable contributions. A comprehensive list of acknowledgments is available at www.for2107.de/acknowledgements. The study protocols were approved by the local Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty at the University of Marburg (AZ 07/14) and adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation and received financial compensation for their involvement.

Author contribution

R.R.M.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing – Original draft preparation.

S.S.: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – review & editing.

T.K.: Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

U.D.: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

F.S.: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Other authors: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

All authors contributed to the development of the article and approved the final submitted version.

Financial support

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) through grant STE3301/1–1 (project number 527712970) and by the Von Behring-Röntgen Society (project number 72_0013), both awarded to Frederike Stein.

Further support was provided by the DFG-funded research unit FOR 2107 (project number 240413749), with funding allocated to Udo Dannlowski (grants DA1151/5–1, DA1151/5–2, DA1151/9–1, DA1151/10–1, and DA1151/11–1) and Tilo Kircher (grants KI588/14–1, KI588/14–2, KI588/20–1, and KI588/22–1). This study also received support from the DFG Collaborative Research Centre/Transregio 393 (CRC/TRR 393, project number 521379614), with contributions to Igor Nenadić, Udo Dannlowski, Nina Alexander, Benjamin Straube, Hamidreza Jamalabadi, Tilo Kircher, and Frederike Stein.

Additional support was provided by the DYNAMIC Center, supported by the LOEWE program of the Hessian Ministry of Science and the Arts (grant number LOEWE1/16/519/03/09.001(0009)/98).

Udo Dannlowski also received funding from the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research (IZKF) of the Medical Faculty of Münster (grant Dan3/022/22).

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5) to assist with improving the clarity, readability, and language of the text. After using this tool, the authors carefully reviewed, revised, and edited the content to ensure accuracy and appropriateness, and they take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

Tilo Kircher has received unrestricted educational grants from Servier, Janssen, Recordati, Aristo, Otsuka, and Neuraxpharm. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest and report no financial relationships with biomedical entities.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.