Introduction

The mental health of adolescents and young people globally has worsened, as evidenced by an increase in mental health symptoms and disorders (Newlove-Delgado et al. Reference Newlove-Delgado, Marcheselli, Williams, Mandalia, Davis, McManus, Savic, Treloar and Ford2022, CDC, 2021, Thorisdottir et al. Reference Thorisdottir, Agustsson, Oskarsdottir, Kristjansson, Asgeirsdottir, Sigfusdottir, Valdimarsdottir, Allegrante and Halldorsdottir2023, Wiens et al. Reference Wiens, Bhattarai, Pedram, Dores, Williams, Bulloch and Patten2020). This rise has led to a perception of a public health crisis, and created an imperative that we identify the underlying reasons for this rise in rates of mental disorders and novel areas for intervention (Campion et al. Reference Campion, Javed, Lund, Sartorius, Saxena, Marmot, Allan and Udomratn2022). One key factor to consider is that this rise in mental health issues is not happening evenly; many studies have found that low mood, depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts, have all increased in young women to a greater extent than in young men (CDC, 2021, Abel et al. Reference Abel and Newbigging2018). Evidence also shows that young women (16-19 years) are at a particular risk for manifestations of anxious, depressive and somatic problems, commonly called internalising symptoms (Newlove-Delgado et al. Reference Newlove-Delgado, Marcheselli, Williams, Mandalia, Davis, McManus, Savic, Treloar and Ford2022; Soto-Sanz et al. Reference Soto-Sanz, Castellví, Piqueras, Rodríguez-Marín, Rodríguez-Jiménez, Miranda-Mendizábal, Parés-Badell, Almenara, Alonso, Blasco, Cebrià, Gabilondo, Gili, Lagares, Roca and Alonso2019). There is also evidence for high rates of self-harm among young women globally and nationally (Dooley et al. Reference Dooley, O’Connor, Fitzgerald and O’Reilly2019, Doyle et al. Reference Doyle, Treacy and Sheridan2015, Meherali et al. Reference Meherali, Punjani, Louie-Poon, Abdul Rahim, Das, Salam and Lassi2021, Valencia-Agudo et al. Reference Valencia-Agudo, Burcher, Ezpeleta and Kramer2018). The peak age of self-harm for women in Ireland is 15-19 years of age, with rates being twice as high as for males in this age group (Rahman et al. Reference Rahman, Webb and Wittkowski2021). Similarly, the National Self-Harm Registry Ireland, identified that the highest self-harm rate which leads to hospital presentation, is in 15–19-year-old females, at rates 3 times that of males (Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Chakraborty, O’Sullivan, Hursztyn, Daly, McTernan, Nicholson, Arensman, Williamson and Corcoran2022). The sex difference in self-harm rates is also evident globally (Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Chakraborty, O’Sullivan, Hursztyn, Daly, McTernan, Nicholson, Arensman, Williamson and Corcoran2022, Kidger et al. Reference Kidger, Heron, Lewis, Evans and Gunnell2012, Mahinpey et al. Reference Mahinpey, Pollock, Liu, Contreras and Thompson2023, Gillies et al. Reference Gillies, Christou, Dixon, Featherston, Rapti, Garcia-Anguita, Villasis-Keever, Reebye, Christou, Al Kabir and Christou2018, Stallard et al. Reference Stallard, Spears, Montgomery, Phillips and Sayal2013).

One reason for this difference may be the differing effects of social behaviours in young people, between young men and women. Screentime, which covers both use of social media and gaming (Burén et al. Reference Burén, Nutley and Thorell2023), is now a frequent activity of the majority of young people (Boniel-Nissim et al. Reference Boniel-Nissim, Marino, Galeotti, Blinka, Ozoliņa, Craig, Lahti, Wong, Brown, Wilson, Inchley and van den Eijnden2024). Screen-time usage patterns differ by gender, with females more likely to engage in communication-based activities, rather than activities such as gaming (Dissing et al. Reference Dissing, Hulvej Rod, Gerds and Lund2021; Lopes et al. Reference Lopes, Valentini, Monteiro, Costacurta, Soares, Telfar-Barnard and Nunes2022). One theory to explain the adverse effect of social media use is that it encourages social comparisons to others (Samra et al. Reference Samra, Warburton and Collins2022).

Another important consideration is that screen-time usage may have changed since the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns. During the pandemic, social media use increased (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Boland, Bell, Nicholas, La Sala and Robinson2022; Josiah & Ncube, Reference Josiah and Ncube2023). These lockdowns appeared to have had a negative impact on young people’s mental health (Dooley et al. Reference Dooley, Power, Healy, Cotter and Cannon2024)and there is some evidence that these effects were intensified in females, with young females showing higher levels of depression and anxiety during the pandemic than males (Rahman et al. 2021) However there is also evidence that young people’s mental health was beginning to deteriorate before the pandemic (Slee et al. Reference Slee, Nazareth, Freemantle and Horsfall2021, Piao et al. Reference Piao, Huang, Han, Li, Xu, Liu and He2022, Mojtabai et al. Reference Mojtabai, Olfson and Han2016, Thorisdottir et al. Reference Thorisdottir, Asgeirsdottir, Sigurvinsdottir, Allegrante and Sigfusdottir2017).

Screen time

Overall evidence suggests that significant amounts of time spent on screens is associated with poorer mental wellbeing (Santos et al. Reference Santos, Mendes, Sen Bressani, de Alcantara Ventura, de Almeida Nogueira, de Miranda and Romano-Silva2023). This adverse effect has been shown to be more pronounced in females than males (Twenge & Martin, Reference Twenge and Martin2020). However, different types of screen time use are associated with poorer outcomes. High social media use has been linked to increased rates of depression and stress, which appears to have been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic (Rahman et al. 2021). There has been an increase in screen use among adolescents in recent years - in 2022 48% of adolescents spent 5+ hours on social media a day (Bozzola et al. Reference Bozzola, Spina, Agostiniani, Barni, Russo, Scarpato, Di Mauro, Di Stefano, Caruso, Corsello and Staiano2022). Comparatively, while a systematic review found that passive screen-time can elevate the risk for depression, this was only in samples which did not consider sex, when this was examined, males did not show an increased risk for depression (Li et al. Reference Li, Zhang, Zhu, Zeng, Huang, Zhuge, Kuang, Yang, Yang, Chen, Gan, Lu and Wu2022). Although excessive gaming is linked to poorer mental health in both genders (Park et al. Reference Park, Angelica and Trisnadi2025; Twenge & Martin, Reference Twenge and Martin2020), the negative impact appears to be less pronounced in males when both are considered. Two studies investigated gender and screen-time during the COVID-19 pandemic, mostly focused on social media and both observed poorer mental health outcomes in females (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Jacob, Trott, Yakkundi, Butler, Barnett, Armstrong, McDermott, Schuch, Meyer, López-Bueno, Sánchez, Bradley and Tully2020; Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Lipsitz, Nasri, Lui, Gill, Phan, Chen-Li, Iacobucci, Ho, Majeed and McIntyre2020).

Body dissatisfaction

Body dissatisfaction; negative thoughts and feelings about one’s body (Grogan, Reference Grogan2021), may also be a gender-specific risk factor, with evidence suggesting that body dissatisfaction is higher in women relative to men (Quittkat et al. Reference Quittkat, Hartmann, Düsing, Buhlmann and Vocks2019). Body dissatisfaction is also associated with eating disorder symptoms, elevated depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms in both sexes (Jiotsa et al. Reference Jiotsa, Naccache, Duval, Rocher and Grall-Bronnec2021; Barnes et al. Reference Barnes, Abhyankar, Dimova and Best2020; Stice & Shaw, Reference Stice and Shaw2002).

Studies have found links between increased screen time and ‘unhealthy diet changes’ (Trott et al. Reference Trott, Driscoll, Irlado and Pardhan2022). Image- and video-based platforms like Pinterest, Instagram, and TikTok feature abundant body-focused content. Their visual format encourages social comparison, with evidence showing that upward appearance comparisons and body surveillance mediate the link between social media use and body dissatisfaction (Bissonette Mink & Szymanski, Reference Bissonette Mink and Szymanski2022). Similarly, people exposed to “fitspiration” images (depicting attractive, athletic individuals linking their looks to exercise) report greater body dissatisfaction and lower appearance self-esteem (Fung et al. Reference Fung, Blankenship, Ahweyevu, Cooper, Duke, Carswell, Jackson, Jenkins, Duncan, Liang, Fu and Tse2020).

Sexting behaviours

A final area of modern social behaviours which should be considered is the convergence of technology and personal communication which has led to the rise of sexting, the sharing of sexually explicit messages, images, or videos via digital devices (Madigan et al. Reference Madigan, Ly, Rash, Van Ouytsel and Temple2018). This phenomenon, particularly among youths, has expanded with the emergence of smartphones. Sexting occurs across all social media platforms, from private messaging services (e.g. WhatsApp), to apps designed for dating (e.g. Hinge). A 2020 meta-analysis of 39 studies involving over 110,000 participants revealed an increase in youth sexting since 2005, with females receiving more “sexts” than males (Mori et al. Reference Mori, Park, Temple and Madigan2022). Gender differences are notable, with females more likely to be coerced into sexting. (Holfeld et al. Reference Holfeld, Mishna, Craig and Zuberi2024)and more likely to be victims of non-consensual sexting, dissemination of sexual images without the person’s consent (Gassó et al. Reference Gassó, Klettke, Agustina and Montiel2019). Non-consensual sexting has been linked to negative impacts like anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts (Lu et al. Reference Lu, Baumler and Temple2021, Ganson et al. Reference Ganson, O’Connor, Nagata, Testa, Jackson, Pang, Mishna and Wang2024, Gassó et al. Reference Gassó, Klettke, Agustina and Montiel2019, Nesi et al. Reference Nesi, Burke, Bettis, Kudinova, Thompson, MacPherson, Fox, Lawrence, Thomas, Wolff, Altemus, Soriano and Liu2021). Evidence for the association between consensual sexting behaviours and mental health has been inconclusive, although differences based on age have been considered as a risk factor for poor mental health outcomes (Gassó et al. Reference Gassó, Mueller-Johnson and Montiel2020).

In this study, we aim to investigate risk factors for psychopathology and self-harm in a sample of adolescents during COVID-19, looking at social behaviours and exploring three areas;

-

1. Screen-time usage and its association with mental health outcomes. We hypothesise females will spend more time on social media and that they will show poorer outcomes than males.

-

2. Body dissatisfaction and its association with mental health outcomes. We hypothesise that body dissatisfaction will be higher in young females, and associated with elevated issues. We hypothesise this effect will be more pronounced in those with moderate/high social media use.

-

3. Sexting behaviours and its association with mental health outcomes. We hypothesise that in a young sample, females will be more likely to engage in the activity, and experience adverse outcomes.

Method

Study design, participants and setting

The current survey is part of the Planet Youth project Ireland, which is based on the Icelandic Prevention Model. In brief, the Planet Youth model is designed to understand risk and protective factors for substance use and mental health problems among adolescents to help design interventions for these at the community level (Kristjansson et al. Reference Kristjansson, Sigfusdottir, Thorlindsson, Mann, Sigfusson and Allegrante2016, Sigfusdottir et al. Reference Sigfusdottir, Soriano, Mann and Kristjansson2020). Surveys are repeated every 2 years in these communities.

The current data was collected between October and December 2021 in one urban area (North Dublin) and two rural areas (Cavan and Monaghan). All schools and YouthReach centres (non-traditional secondary educational settings) in these areas were invited to participate in the survey by local partner organisations. The survey was mainly aimed at students in 4th (“Transition Year”) year at school, and comparable groups in YouthReach centres.

Survey completion took approximately 60 minutes and took place during school time. Teachers delivered standardised instructions on administering the survey. Project staff assisted teachers in delivering the survey. Prior to taking part in the survey young people watched a short instructional video on how to complete the survey. Young people did not have to answer questions they did not feel comfortable with and opt-out consent was applied.

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (RCPI) RECSAF 144V2.

Outcome measures

Psychopathology

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman, Reference Goodman1997) is a screening tool designed to assess emotional and behavioural problems in young people. The measure has 20 questions covering 4 categories of mental health issues: emotional problems, peer problems, conduct problems and inattention/hyperactivity problems, Response options to each item include “not true”, “somewhat true” and “certainly true”.

We focused on (1) the Total Problems Score, which combines information from all 20 items, and (2) the Internalising Score, which combines information from 10 items about emotional problems and peer problems. Response options to each item include “not true”, “somewhat true” and “certainly true”.

The self-report version of the SDQ is a well validated measure of mental health in adolescents aged 14 – 18, with increasing Total Problem Scores predicting increasing likelihood of mental disorder (Goodman et al. Reference Goodman, Meltzer and Bailey2003, Muris et al. Reference Muris, Meesters and van den Berg2003, Lundh et al. Reference Lundh, Wångby-Lundh and Bjärehed2008, Vugteveen et al. Reference Vugteveen, de Bildt, Theunissen, Reijneveld and Timmerman2021).

Total Problem Scores of 20 or more, and Internalising Scores of 12 or more, correspond to “Very High” scores with respect to risk for mental disorder and population norms (4-band categorisation for 4 – 17 year olds; https://www.sdqinfo.org/py/sdqinfo/c0.py). We used these cut-points for our categorical analyses.

Life time self-harm

Lifetime self-harm was captured by the question: “During your lifetime, how often have you harmed yourself on purpose (e.g. scratching, burning, cutting…)”. Response options included “Never”, “Once”, “Twice”, “3 – 4 times” and “5 times or more” which were dichotomised into “Never” and “At least once”.

Exposure measures (Risk factors)

Social media use and screen time

Participants reported the amount of time per day they spent (1) on social media; (2) watching shows, movies or videos (“passive watching” for short); and (3) playing video games. Responses were originally provided on an 8-point scale from “Almost no time” to “6 hours or more” We re-binned responses into a 3-point scale: “1 hour or less”, “2 – 3 hours” and “4 or more hours”.

Body dissatisfaction

Participants were asked how well the statement “I am happy with my body” applied to them. Responses included [applies] “very well”, “well”, “poorly” and “not at all”, which were dichotomised with the latter two responses indicating poor body image.

Sexting behaviours

Two types of sexting behaviours were examined in the questionnaire: participant sending a sexually explicit image (hereafter: sending SEI) (“[have you] sent a sexually explicit image of yourself to someone through social media, smartphone messaging service or dating app”) and others sharing images of the participant (hereafter: non-consensual SEI) (“[has] somebody shared a sexually explicit or nude image of you without your permission”).

Gender

Gender in this study was defined based on participant self-identification, with 4 available options (male, female, trans/non-binary, prefer not to say). For the current study, we opted to exclude those who identified as “trans/non-binary” and “prefer not to say”, as they represented a small subset of the whole sample (n = 174, ∼4%), and this sample size imbalance could lead to statistical power issues and risk of type-I and -II error due to high variance.

Covariates

Three potential confounds were controlled for in multivariate models: Age of the participant in years, Geographic location of participant’s school (Urban/Rural) and Relative familial income. The latter was captured by the question “How well off financially do you think your family is in comparison to other families” with responses dichotomised into Worse off (a little worse off/considerably worse off/much worse off) and the Same or better than others (a little better off/considerably better off/much better off/similar to others).

Statistical analysis

First, we provided descriptive statistics (means/point prevalence) on the risk factors and sex differences for each risk factor. Second, we performed a series of multilevel models to assess the effect of these risk factors on mental health outcomes. Multilevel modelling was chosen to account for variation on mental health outcomes across participating schools (1 random intercept). Linear multilevel models were used to predict continuous SDQ scores (Total and Internalising), while logistic multilevel models were used to predict 3 binary outcomes: Very High Total Problem Score; Very High Internalising Scores and Lifetime Self-harm. Post hoc analyses examining the interaction between social media and body image was conducted, accounting for the same risk factors and covariates.

We took a gender-stratified approach to analyses, such that all tests were performed in males and females separately. To assess whether gender differences in estimates were significant we also performed full-sample analyses with interaction terms between each risk factor and gender.

Sensitivity analyses investigated whether findings were explained by unequal numbers of males and females, or different age ranges in each sex.

Results

Of the invited schools, 75% in urban areas and 100% in rural areas participated (n = 43). Among invited students, 75% in urban areas and 86% in rural areas took part (n = 4404), with an overall youth participation rate of 79%. Most participants were aged 15 – 16 years (74.9%), and 60% lived in an urban setting (North Dublin). Males (53.6%) and females (46.4%) were similarly represented. About 1 in 10 participants (11.1%, n = 454) reported their family was financially worse off than others.

Gender differences in social behaviours

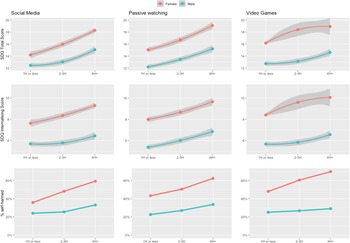

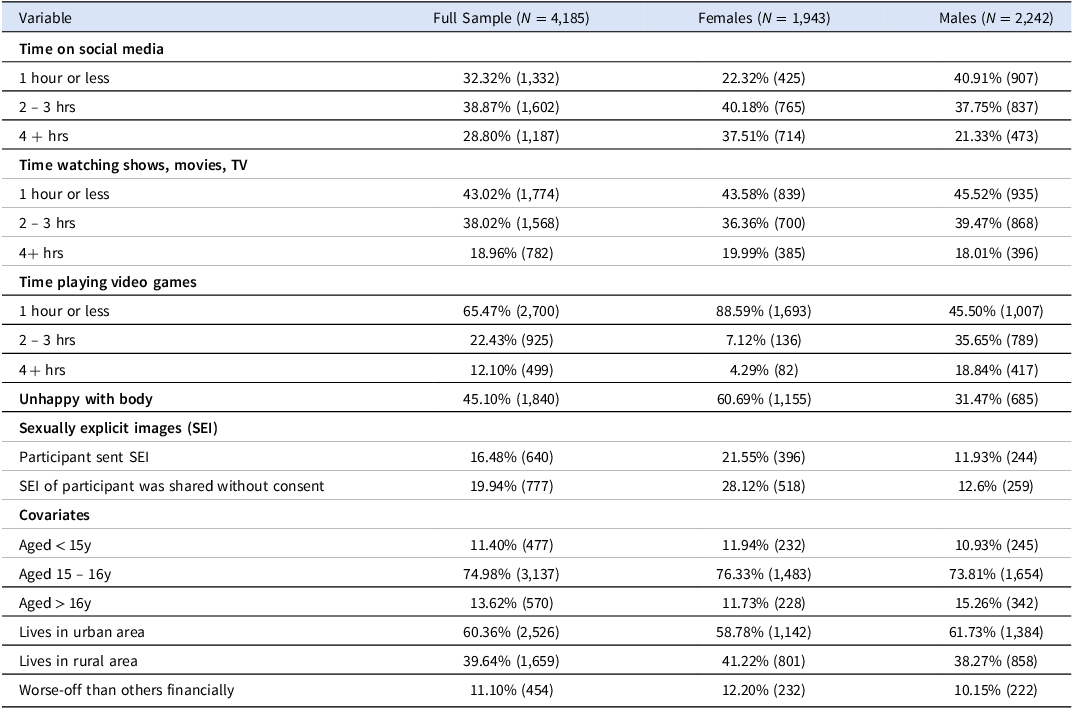

Females reported longer screen time (40.18% spent 2 – 3 hours; 37.51% spent 4+ hours) than males (37.75% and 21.33%, respectively). Males engaged more in moderate to high passive screen time and video games (Table 1; Figure 1). Body dissatisfaction was twice as common among females (60.69%) compared to males (31.47%) (Table 1; Figure 2). Sexting was also more common in females (sending SEI = 21.55%, non-consensual SEI = 28.12%) than males (sending SEI = 11.93%, non-consensual SEI = 12.6%) (Table 1 & Figure 2).

Figure 1. Prevalence of gender differences across exposures of interest: social media use (3 types - top row), sexting and body dissatisfaction.

Figure 2. Unadjusted levels of mental health problems for males and females with varying levels of screen use. Top row = mean SDQ total problems scores; middle row = mean SDQ internalising problems scores; bottom row = mean rates of self-harm. Error bar indicates standard error of the mean for continuous outcomes.

Table 1. Distribution of risk factors (Screen-time, body dissatisfaction and sexting) and covariate (age, family income, urban upbringing) among sample participants for the full sample and separately by sex

Mental health outcomes

The mean SDQ total problems score was 14.76 (SD = 6.26), with females scoring significantly higher than males (m = 3.2, t = 16.10, p < .001). This difference was driven by internalising symptoms (Figure S1). The mean SDQ internalising score was 7.16 (SD = 3.86), with females again reporting more symptoms (m = 8.6, t = 22.28, p < .001). Lifetime self-harm prevalence was 37.2%, with nearly twice as many females (50%) reporting self-harm compared to males (26%; χ2 = 230.6, p < .001).

Screen time and mental health outcomes

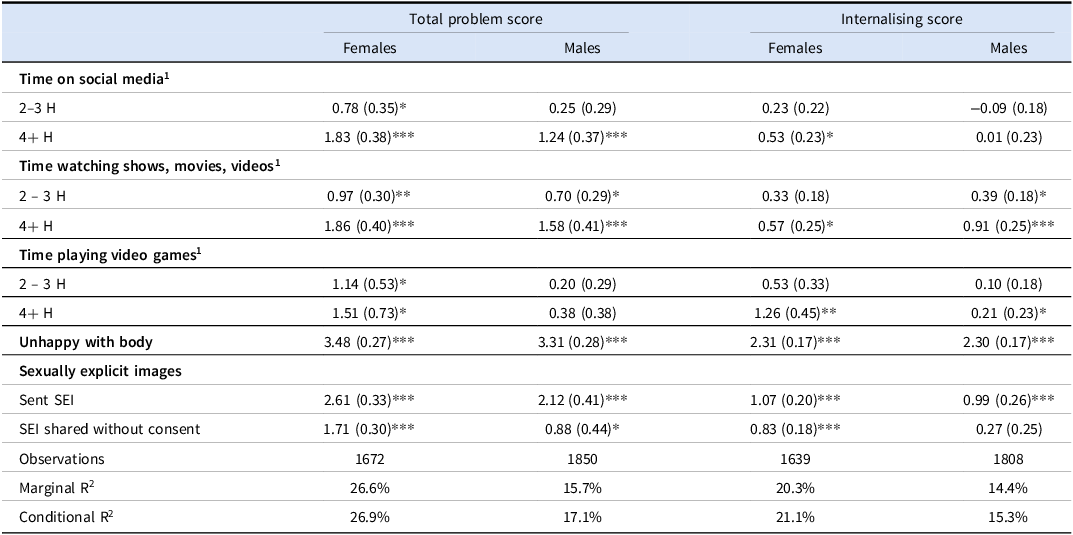

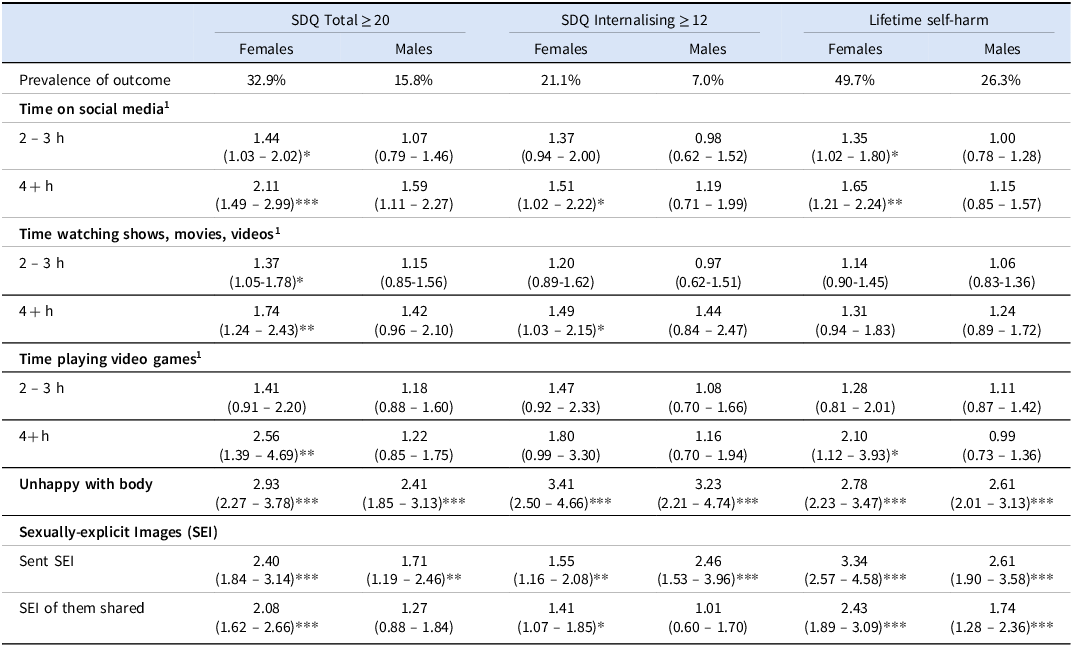

Moderate (2 – 3 hours) and high (4+ hours) screen time (passive, social media, video games) were associated with elevated SDQ scores for females (Table 2). For males, only moderate passive, and high social media and passive use were linked to mental health issues (Table 2). High (but not moderate) screen use increased internalising symptoms for females. For males, only passive screen time and high video gaming were associated with internalising symptoms.Females who spent 4+ or 2 – 3 hours daily on social media were 2.1 and 1.4 times more likely, respectively, to meet “very high” criteria for mental health symptoms (Table 4). Dose–response effects were also found for passive screen time and video games in females (Table 3). High social media and passive screen-time use increased odds of internalising symptoms in females, but not males (Table 3). Moderate/high social media use and 4+ hours of video games were linked to lifetime self-harm in females, but no screen-time measure was associated with self-harm in males (Table 3).

Table 2. The associations between social media use, sexting and body image dissatisfaction on continuous SDQ scales (total problems and internalising) adjusted for covariates. Estimates are beta coefficients (and standard errors), for males and females separately

1Reference level: 1 hour or less

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Table 3. Adjusted effects of each exposure (rows) on mental health scores (columns) as odds ratios (and 95% CIs), for males and females separately

1Reference level: 1 hour or less *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 2 shows a dose response relationship between levels of screen time and increasing mental health problem scores for both males and females, but stronger effects in females for all three categories of screen time, across all outcome measures.

Body dissatisfaction and mental health

Body dissatisfaction had significant associations with poor mental health for both males and females (Tables 2 & 3). Females unhappy with their body had higher Total Problem scores (β=3.48), higher Internalising scores (β=2.31), and increased odds of being in the very high total SDQ group (OR = 2.93, 95%CI[2.27,3.78]), Very High Internalising group (OR = 3.41, 95%CI[2.50,4.66]), and of lifetime self-harm (OR = 2.78, 95%CI[2.23,3.47]). Males unhappy with their body also had higher Total Problem scores (β=3.31), higher internalising scores (β=2.30), > 2-fold increased odds of Very High total SDQ (OR = 2.41, 95%CI[1.85,3.13]), 3-fold increased odds of Very High internalising (OR = 3.23, 95%CI[2.21,4.74]), and 2.6-fold increased odds of Lifetime Self-harm (OR = 2.61, 95%CI[2.01,3.13]).

Examining the interaction between body image and social media, moderate or high social media use alongside body dissatisfaction was not associated with Total SDQ score, Very High Total SDQ score, or Lifetime Self-harm for either sex (Table S1). Only internalising symptoms showed an association: females dissatisfied with their body who spent 2 – 3 hours daily on social media reported fewer internalising symptoms (β= −0.90). Similarly, females who spent 4+ hours were less likely to be in the “very high” internalising group (OR = 0.33, 95%CI[0.12,0.90]) (Table S1).

Sexting and mental health

Sending an SEI was associated with elevated mental health problems for both males and females (Tables 2 & 3). Females who had sent an SEI reported higher Total Problems (β=2.61, SE = 0.33), Internalising problems (β=1.07, SE = 0.20), and increased odds of being in the Very High total SDQ group (OR = 2.40, 95%CI[1.84,3.14]), very high internalising group (OR = 1.55, 95%CI[1.16,2.08]), and Lifetime Self-harm (OR = 3.34, 95%CI[2.57,4.58]). Males showed similar patterns with elevated Total Problems (β=2.12, SE = 0.41), Internalising problems (β=0.99, SE = 0.26), and higher odds of Very High Total SDQ (OR = 1.71, 95%CI[1.19,2.46]), Very High Internalising (OR = 2.46, 95%CI[1.53,3.96]), and Lifetime Self-harm (OR = 2.61, 95%CI[1.90,3.58]).

Non-consensual SEI was linked to poorer mental health across all measures for females. For males, it was only associated with elevated Total SDQ score (β=0.88, SE = 0.44) and higher odds of Lifetime Self-harm (OR = 1.74, 95%CI[1.28,2.36]).

Gender-by-exposure interactions

Interactions between gender and each exposure were tested to assess whether gender differences were significant (see “Sig. gender diff” in Tables 2–3). A significant interaction between gender and time spent playing video games was found for predicting SDQ internalising score (Table 2), Very High Total Problems, and Lifetime Self-harm (Table 3). However, caution is advised interpreting this, due to the small number of females reporting high video game use (n = 82). Unadjusted interactions between gender and types of screen use on mental health outcomes are shown in Fig. 2.

Discussion

Our study set out to examine specific risk factors which may contribute to the elevated rates of mental disorders in young women. We hypothesised that all risk factors (screen time, body dissatisfaction, sexting) would be engaged in more frequently by females, and that they would be associated with poorer mental health outcomes (poor mental health, internalising problems, self-harm). Our study found gender-based differences, showing strong associations between social media use, body dissatisfaction, and sexting with poor mental health and self-harm in females.

Our findings align with previous research showing the negative mental health impacts of excessive social media use in adolescents. Similar to Meherali et al. (Reference Meherali, Punjani, Louie-Poon, Abdul Rahim, Das, Salam and Lassi2021) and Samji et al. (Reference Samji, Wu, Ladak, Vossen, Stewart, Dove, Long and Snell2022), we observed a strong link between smartphone addiction and depressive symptoms. Twenge et al. (Reference Twenge, Joiner, Rogers and Martin2018) also found that adolescents using social media for more than two hours a day face higher risks of depression and self-harm, supporting our conclusion that increased usage correlates with poorer mental health. We found that that spending more than 4 hours on social media a day was linked with 2-fold increased odds of poor mental health in females, compared to a 1.5-fold increased odds in males

Gender-specific trends further reinforce our results. Blomfield neira & Barber, Reference Blomfield neira and Barber2014), reported that female social media users are more likely to experience lower self-esteem and depressive symptoms, consistent with our findings suggesting that girls may be especially vulnerable to emotional impacts. Similarly, Sohn et al. (Reference Sohn, Rees, Wildridge, Kalk and Carter2019) found that problematic smartphone use – more common among girls and characterised by addiction-like behaviours such as anxiety and neglect of other activities – was consistently linked to negative mental health outcomes.

We theorise that this heightened vulnerability among girls may be driven by both content and platform design. Girls are more likely to engage with image-focused platforms like Instagram and TikTok, where idealised portrayals of appearance and lifestyle foster social comparison, which is strongly linked to lower self-esteem and increased depressive symptoms (Samra et al. Reference Samra, Warburton and Collins2022).

We did not find an association between video game usage and poor mental health in males. This differs from a systematic review which found that higher video game and screen time usage was linked to anxiety, depression, and other psychological issues in both genders (Samji et al. Reference Samji, Wu, Ladak, Vossen, Stewart, Dove, Long and Snell2022). This discrepancy may be due to changing usage patterns in younger samples (e.g., more females gaming or fewer males) or differences in the types of games played, with females possibly engaging more in social or online games. To explore this further in a post-COVID context, longitudinal studies with more specific screen-time measures are needed.

For both males and females in our study, body dissatisfaction was strongly associated with poor mental health and self-harm. However, since 61% of females report body dissatisfaction compared to 36% of males, this risk factor is affecting more of the female population. We found strong associations between body dissatisfaction and poor mental health and self-harm risks. Our cross-sectional findings are supported by a longitudinal study following females’ body image over 8 years which found that body dissatisfaction is associated with elevated depressive symptoms (Ohring et al. Reference Ohring, Graber and Brooks-Gunn2002). Similarly, a systematic review found that greater body dissatisfaction is associated with higher risk of depression (Rounsefell et al. Reference Rounsefell, Gibson, McLean, Blair, Molenaar, Brennan, Truby and McCaffrey2020). Scully et al. (Reference Scully, Swords and Nixon2023) identified a strong link between body dissatisfaction and time spent on social comparison – especially through image-based social media. Interestingly, the interaction between social media and body dissatisfaction in our study was mostly non-significant, but females with body dissatisfaction and moderate/high social media use showed lower internalising symptoms. One explanation may be that this is a ceiling effect, given body dissatisfaction and heavy social media are strong independent risk factors, and most mental health symptoms were non-significant. However, some previous research has failed to find a direct association between social media and body dissatisfaction, particularly in adolescent females (Maes & Vandenbosch, Reference Maes and Vandenbosch2022). Further research examining this, with further details on the type of content looked at on social media and more detailed measures of body dissatisfaction, would help elucidate this result.

In our study, both sending sexually explicit images and experiencing non-consensual sharing of such images were linked to poor mental health and self-harm, particularly among females. These behaviours were significantly more common in girls – 1 in 5 reported sending explicit images, compared to 1 in 10 boys. Doyle et al. (Reference Doyle, Douglas and O’Reilly2021) found associations between non-consensual sexting and self-harm, but not with consensual sexting. Our study observed that both consenual and non-consenual sexting were associated with increased risk of self-harm in females. Gassó et al. (Reference Gassó, Mueller-Johnson and Montiel2020) found that girls are more likely to be pressured or coerced into sexting, which may help explain this gender difference in outcomes. There remains a clear gap in the literature, particularly in longitudinal studies, regarding the mental health impacts of adolescent sexting. Our findings highlight the need for further research into this issue among young people.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include its population-based data, high response rate (79%), and large sample size (4,404), which enhance representativeness and statistical power. The use of the internationally validated SDQ scale to measure mental health outcomes is another strength.

Limitations include the study’s cross-sectional design, which prevents establishing causality or temporality. Additionally, the study only surveyed Cavan, Monaghan, and North Dublin, which may not fully represent all of Ireland, as areas of deprivation were excluded such as inner city Dublin. Social media measures focused solely on duration, without examining types of use or how individuals engage with apps. The timing of the survey, during a partial nationwide lockdown, likely led to increased online time, which may have influenced the results. Repeating the study during a non-restricted period could provide further insights.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates significant relationships between social media use, body dissatisfaction and sexting behaviours with poor mental health and self-harm in young people, especially young women. Further research, particularly qualitative is needed to explore how males and females engage with social media and how these interactions may influence the differing mental health responses. Overall, our results show that not only do these three areas of teenage life have a correlation with poor mental health, but that these effects are intensified in females. This could partially explain mental health deterioration of young women.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2025.10122.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a Health Research Board summer student scholarship to DSC*, and a RCSI summer studentship to DSC*, SMC, KG and AG. We wish to thank all young people who participated in the Planet Youth survey, as well as the school staff and study administrators that facilitated it. Many thanks also to the Planet Youth Team for North Dublin, Cavan and Monaghan (https://planetyouthpartner.ie), including those from the Cavan and Monaghan Education and Training Board (Maureen McIntyre, Collette Deeney), the North Dublin Regional Drug and Alcohol Task Force (David Creed), the North Eastern Regional Drug & Alcohol Task Force (Andy Ogle), and TUSLA (Ste Corrigan). This research was supported by Applied Programme Grant (APRO-2023-23) by Health Research Board (VISTA- Vision to Action for mental health policy) award (LS, MC, LD, DRC). ND was supported by a DOROTHY fellowship (DTHY/2023/1705) which receives funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement (No 101034345). This publication has emanated from research conducted with the finacial support of Taighde Eireann- Research Ireland, under Grant number 21/RC/10294_P2 at FutureNeuro Research Ireland Centre for Translational Brain Science.