Granite is geographically restricted to three plutons in the Maya Mountains of Belize (Figure 1) and new evidence of granite ground stone tool (GST) extraction and production proximate to these sources has been identified near the Mountain Pine Ridge (MPR) source (see Spenard et al.; King and Powis, both this section). Granite as a tool stone appears to have been in demand for utilitarian GST and, as such, presents a useful candidate for exploring long-distance exchange (sensu Drennan Reference Drennan1984; Graham Reference Graham1987; Shipley Reference Shipley1976, Reference Shipley1978). However, the mechanisms by which this movement and (re)distribution took place are not well understood. Did metateros (stone workers) or merchants distribute these goods through centralized marketplaces? Were they exchanged through more decentralized means, such as “down-the-line” trade or “direct exchange” between family members? What other forms of socioeconomic mechanisms might explain the movement of such material and how can we identify these various forms of exchange? Elizabeth Graham (Reference Graham1987) posed similar questions over 30 years ago for a variety of resources using geological studies (see Graham, this section); yet only in obsidian and ceramic analyses has such research flourished in Maya archaeology (see e.g., Braswell Reference Braswell, Masson and Freidel2002, Reference Braswell, Garraty and Stark2010; Braswell et al. Reference Braswell, Clark, Aoyama, McKillop and Glascock2000; Cap Reference Cap, Feinman and Riebe2022; Foias and Bishop Reference Foias and Bishop1997; West Reference West, Mason and Freidel2002).

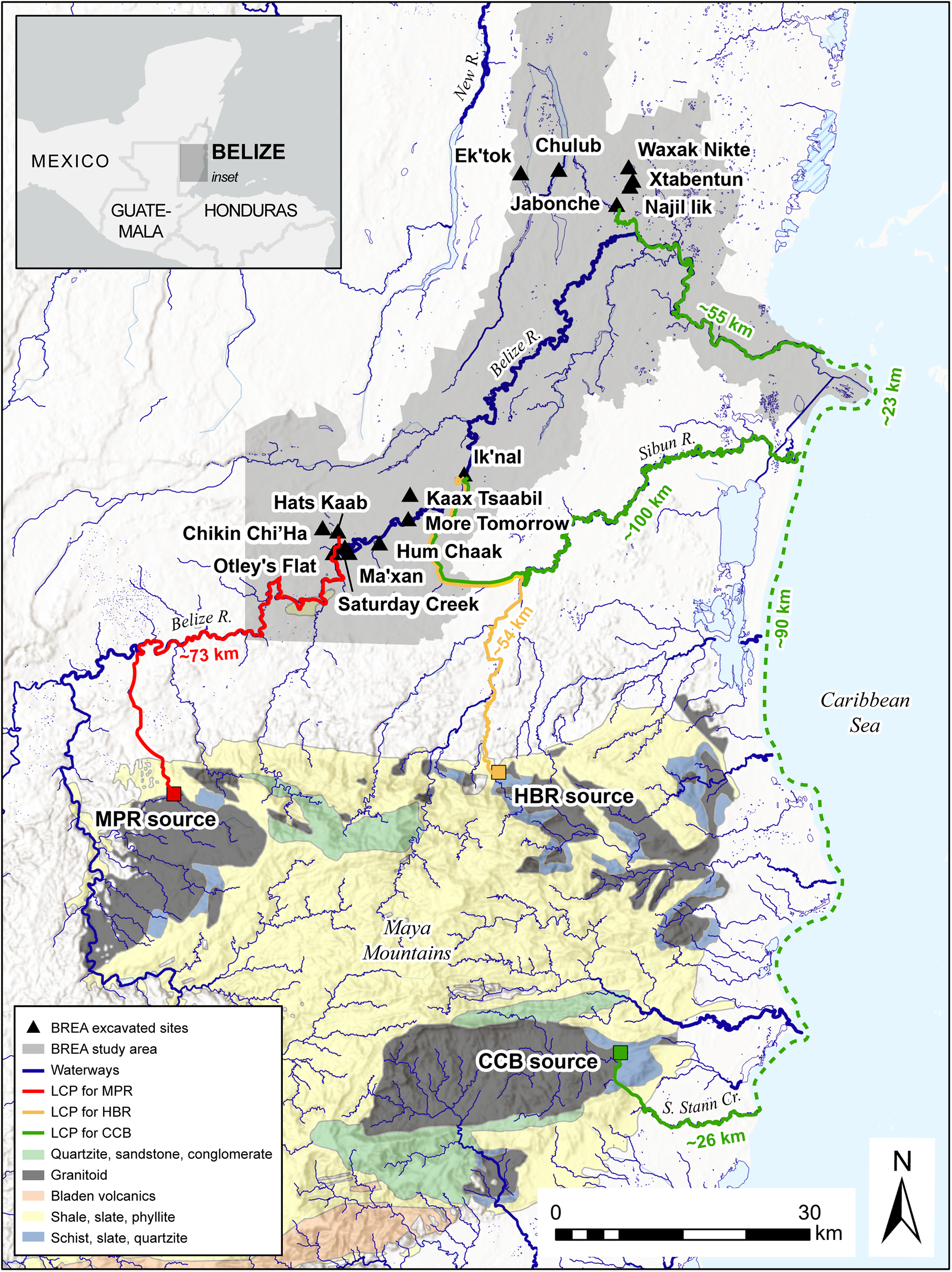

Figure 1. Belize River East Archaeology (BREA) study area and sites discussed in text. Note location of granite plutons (MPR = Mountain Pine Ridge; HBR = Hummingbird Ridge; CCB = Cockscomb Basin). Red, gold, and green routes represent least-cost paths (LCPs).

Recent work by Tibbits (Reference Tibbits2016) provides a method for sourcing GST using portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF), which can geochemically distinguish between the three granite plutons in Belize (Figure 1 [for specifics, see the introduction to this Compact Section]). Analyses applying this sourcing technique reveal important information about the procurement and distribution of granite GST across the Maya Lowlands (Brouwer Burg et al. Reference Brouwer Burg, Tibbits and Harrison-Buck2021; de Chantal Reference de Chantal2019; Halperin et al. Reference Halperin, Lopez, Salas and LeMoine2020; Tibbits Reference Tibbits, Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti2020; Tibbits et al. Reference Tibbits, Peuramaki-Brown, Burg, Tibbits and Harrison-Buck2022). Here, we present a study of 210 GST recovered by the Belize River East Archaeology (BREA) Project, including granite specimens from nine sites in the middle reaches and six from the lower reaches of the Belize River Watershed (Figure 1).

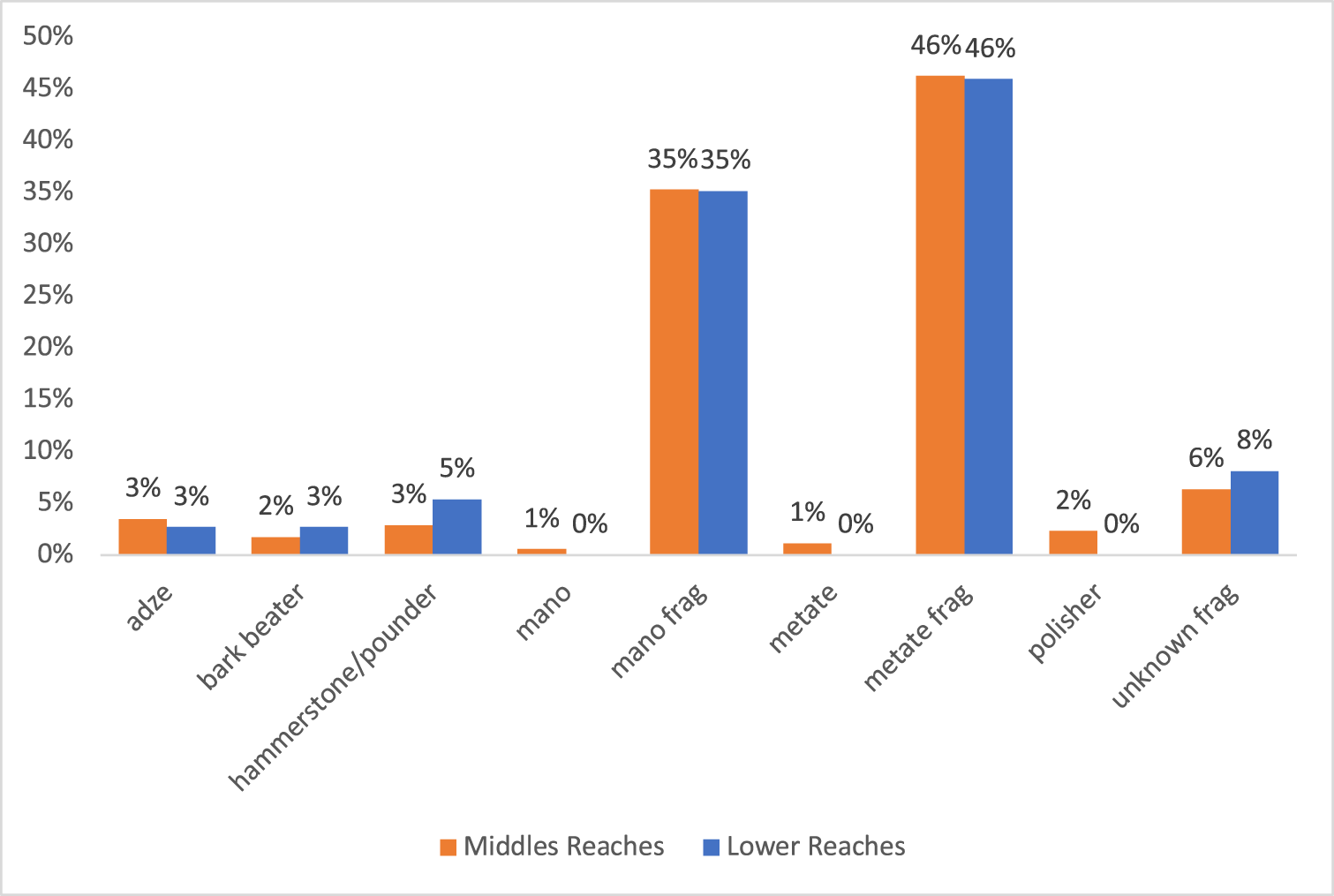

The GST assemblage consists primarily of manos and metates (Figures 2–3 [for a description of GST typology, see the introductory article in this section]). Three-quarters of the granite assemblage derive from excavation and one-quarter from surface collection. Our ability to provide solid temporal ranges for the assemblage is restricted at this point as ceramic analysis is ongoing. However, the overwhelming majority of associated ceramics (13 out of 15 contexts) date to the Terminal Classic period (ca. a.d. 780–930/1000; Harrison-Buck Reference Harrison-Buck2024), with traces of Postclassic occupation. One exception is Hats Kaab in the middle reaches where investigations revealed a large Preclassic E-Group (Brouwer Burg et al. Reference Burg, Marieka and Runggaldier2014; Runggaldier et al. Reference Runggaldier, Burg and Harrison-Buck2013); another E-Group was identified in the lower reaches at the site of Xtabentun (Kaeding et al. Reference Kaeding, Murata, Willis, Burg and Harrison-Buck2024; Figure 1). Doyle (Reference Doyle2012) interprets E-Groups as important nodes in the Preclassic political and economic landscape, suggesting that these large plaza groups functioned as ceremonial spaces and also as possible marketplaces. Hats Kaab and Xtabentun lie ∼54 km apart, more than twice the daily average of non-stop portage (∼23 km) historically documented for traveling merchant-producers in highland Guatemala (Feldman Reference Feldman1971:64). Notably, geochemical results from the GST data suggest that sites in the middle and lower reaches had unequal access to granite tools.

Figure 2. Selection of manos/mano fragments from the middle Belize Valley (top); and selection of metate fragments from the middle Belize Valley (bottom).

Figure 3. Percentage of tool types by region. Note the similarities in overall distributions.

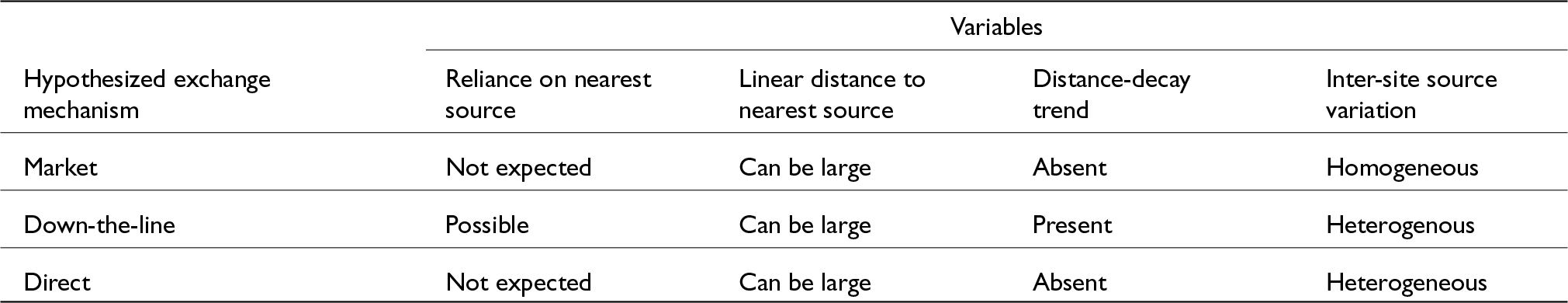

Below, we describe the differential distribution of GST between sites from the middle and lower reaches. Three possible exchange mechanisms—and concomitant material expectations for the archaeological record—are investigated: (1) market, (2) down-the-line, and (3) direct exchange. We underscore that these three mechanisms are just a few of the many exchange dynamics that were likely in operation in the past. For instance, one mechanism not considered here is direct workshop procurement (Fertelmes Reference Fertelmes2014:280; Hirth Reference Hirth1998), because the sites in question are more than a day’s walk (>10 km) to GST workshops.

Modeling mechanisms of movement and exchange

To better understand the distribution of the GST assemblage, we reference two studies positing different exchange mechanisms: (1) a model of obsidian procurement and craft provisioning from Epiclassic Central Mexico (Hirth Reference Hirth1998, Reference Hirth2008, Reference Hirth2013), and (2) a model of vesicular basalt exchange during the Hohokam occupation in the American Southwest (Fertelmes Reference Fertelmes2014). We recognize the pitfalls of applying models developed on different spatiotemporal contexts but reference them as a starting point for further theory development. While neither of these models are an exact fit, together they provide three mechanisms of movement useful for exploring the contours of exchange dynamics: market, down-the-line, and direct exchange.

Market exchange involves balanced exchange between vendors and buyers, often at a marketplace (Fertelmes Reference Fertelmes2014:66; Hirth Reference Hirth1998:454; see also King Reference King2015; Masson and Freidel Reference Masson and Freidel2002; Masson et al. Reference Masson, Freidel and Demarest2020). Market exchange provides equal and regular access to staple goods for many households. Masson (Reference Masson, Masson and Freidel2002:4) notes that “large open plazas” facilitated the exchange of utilitarian goods, often concurrent with political and ritual events. Hirth (Reference Hirth1998:455) writes that “social rank did not affect the basic structure or balance of marketplace exchange” and that all households would have equal access to materials traded in the local marketplace. McBryde (Reference McBryde1947) observed daily consumption rates of 15 metates and 48 manos at the marketplace of Quetzaltenango in highland Guatemala, a number that suggests consistent demand for GST was met in part through market exchange (cf. Fertelmes Reference Fertelmes2014:70).

Granite—a hard, non-local tool stone—may have been in greater demand than local materials but increased in cost with distance from the source (see Feldman Reference Feldman1971:63–64; Masson Reference Masson, Masson and Freidel2002). While water routes are uncommon in colonial accounts, Feldman (Reference Feldman1971:45) notes that overland portage using tumplines was common in early Guatemala. According to Fuentes y Guzmán (2022 [1932]:1:341), “They carry /great weight/ … for a distance of two or three leagues, hanging from the head.” Tumplines likely facilitated the movement of heavy materials like GST which could be transported as much as 10–15 km per day overland. Groups of metatero-merchants may have collectively hauled large quantities of their goods on foot and/or via waterways to marketplaces. However, when distances become prohibitive, access is limited to down-the-line exchange. This entails more informal, decentralized exchanges involving unidirectional movement of goods from production location through multiple intermediate consumers (Fertelmes Reference Fertelmes2014:63). At each exchange, some of the overall supply is “consumed,” meaning items should exhibit a “trickle down” effect where reduction in frequency or volume is commensurate with distance from the source (Clark Reference Clark1979:4; Renfrew Reference Renfrew, Earle and Ericson1977).

Direct exchange is another decentralized form of trade between individuals or households, without any intermediary merchant-vendor (Hirth Reference Hirth1998:455; Johnstone and Shaw Reference Johnstone and Shaw2015:50; Sahlins Reference Sahlins1972). Hirth (Reference Hirth1998:455) notes that such reciprocal exchanges “[result] in a low volume of commodity movement and unequal distribution of resources throughout the society.” Gift-giving is an example of direct exchange among close kin or trading partners that solidifies sociopolitical alliances and provides access to a set of non-local resources (Fertelmes Reference Fertelmes2014:62; see also Mauss 1990 [Reference Mauss1925]; Sahlins Reference Sahlins1972:193). Since gifted goods are not typically exchanged in large quantities, there is potential for them to move farther distances (Johnstone and Shaw Reference Johnstone and Shaw2015:50). Among ancient Maya society, alliance networks often were based upon reciprocal gifting (Harrison-Buck Reference Harrison-Buck2021). In contemporary Maya society, studies show that women play a role in the acquisition and movement of GST via the gifting of these items from an older relative to a bride upon her wedding (Cook Reference Cook1982:254; Searcy Reference Searcy2011:138).

We note that economic interactions—such as those described above—were neither mutually exclusive nor static or isolated engagements (Masson and Freidel Reference Masson and Freidel2012:458), but always in flux and bound up with social relations. We stress that economic and social relations are always mutually constituted and not neatly parsed, even in the context of commercial transactions like market exchange (see Graeber Reference Graeber2002; Harrison-Buck Reference Harrison-Buck2021:569; Sahlins Reference Sahlins1972).

Test variables and expectations

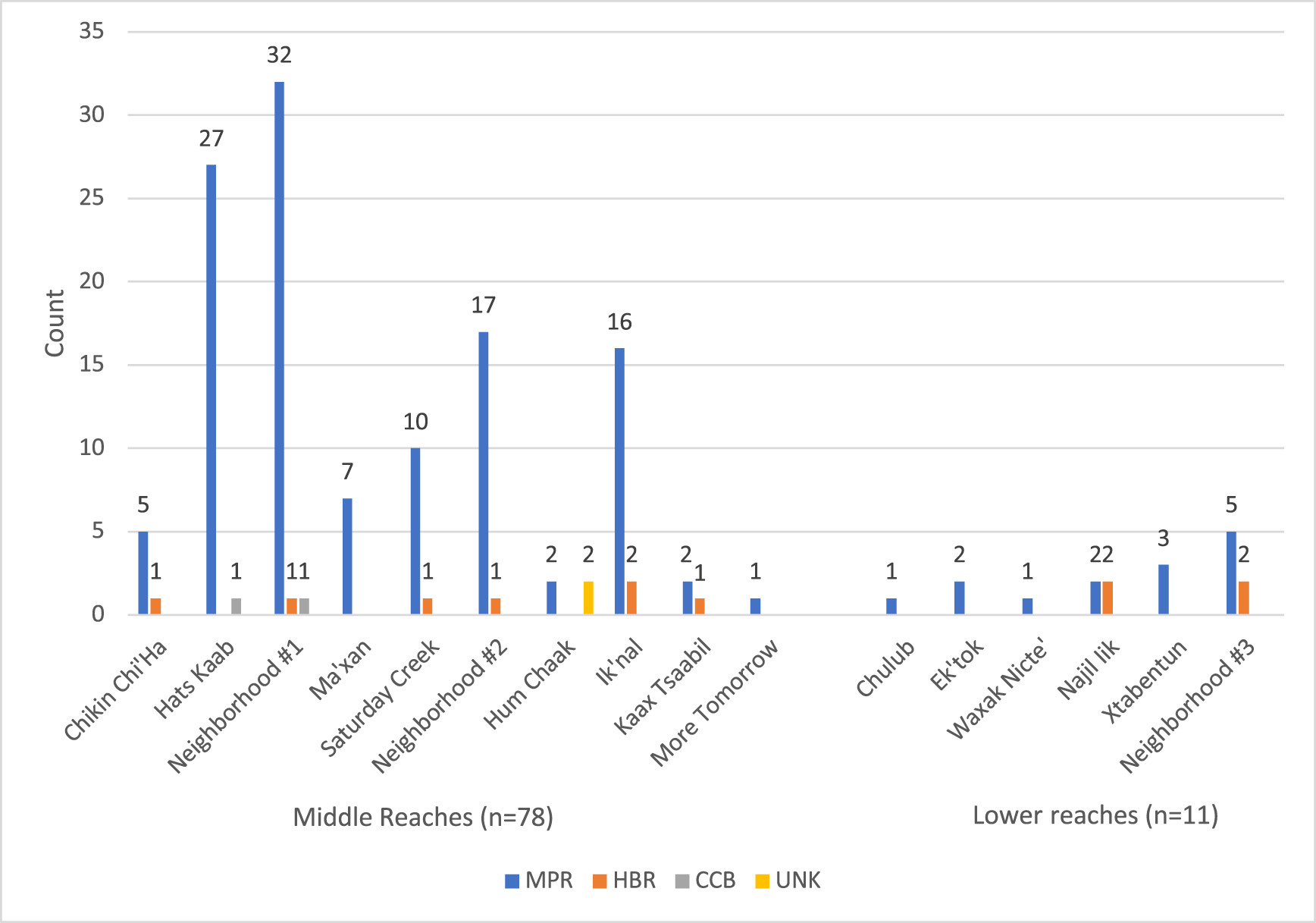

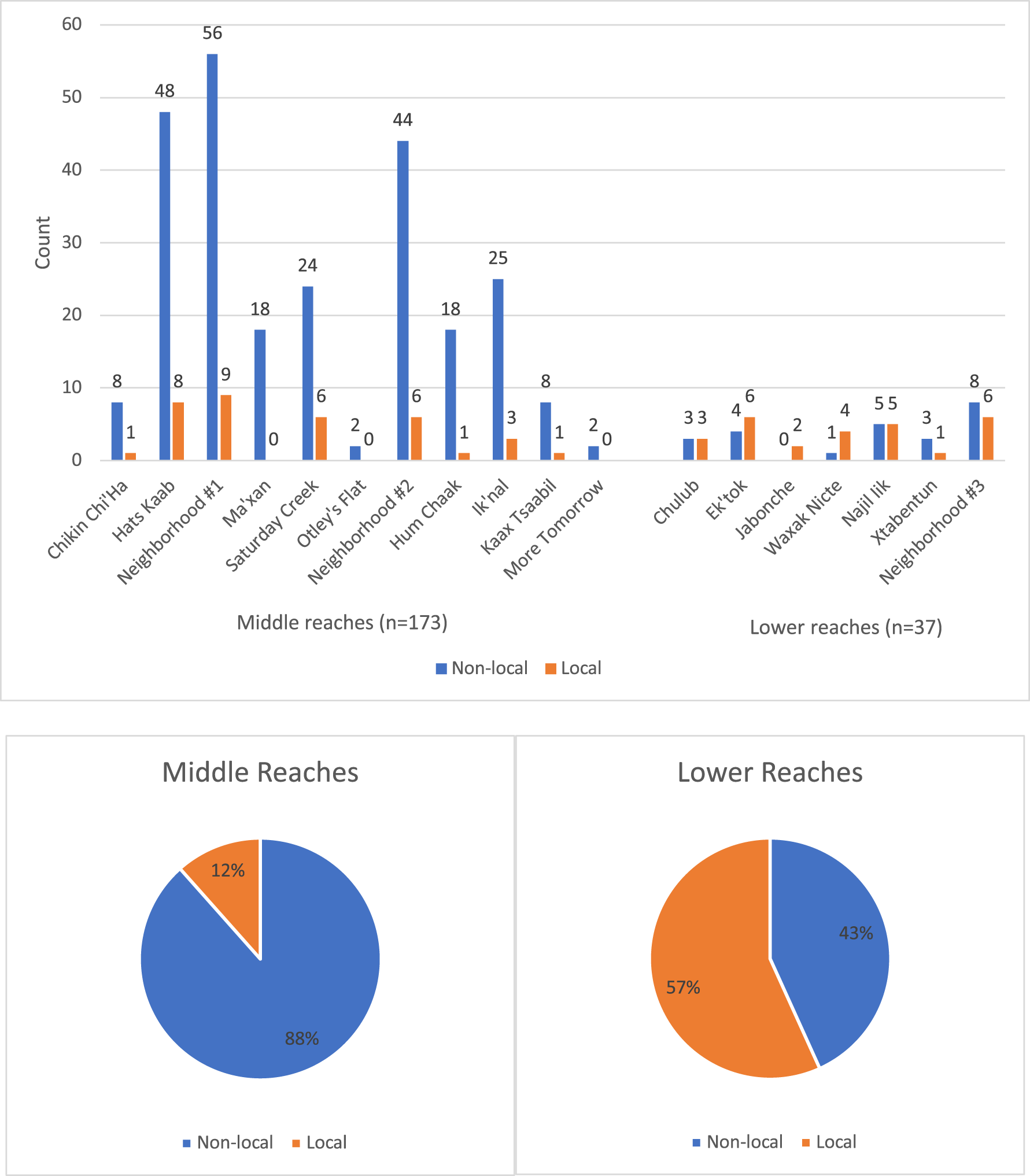

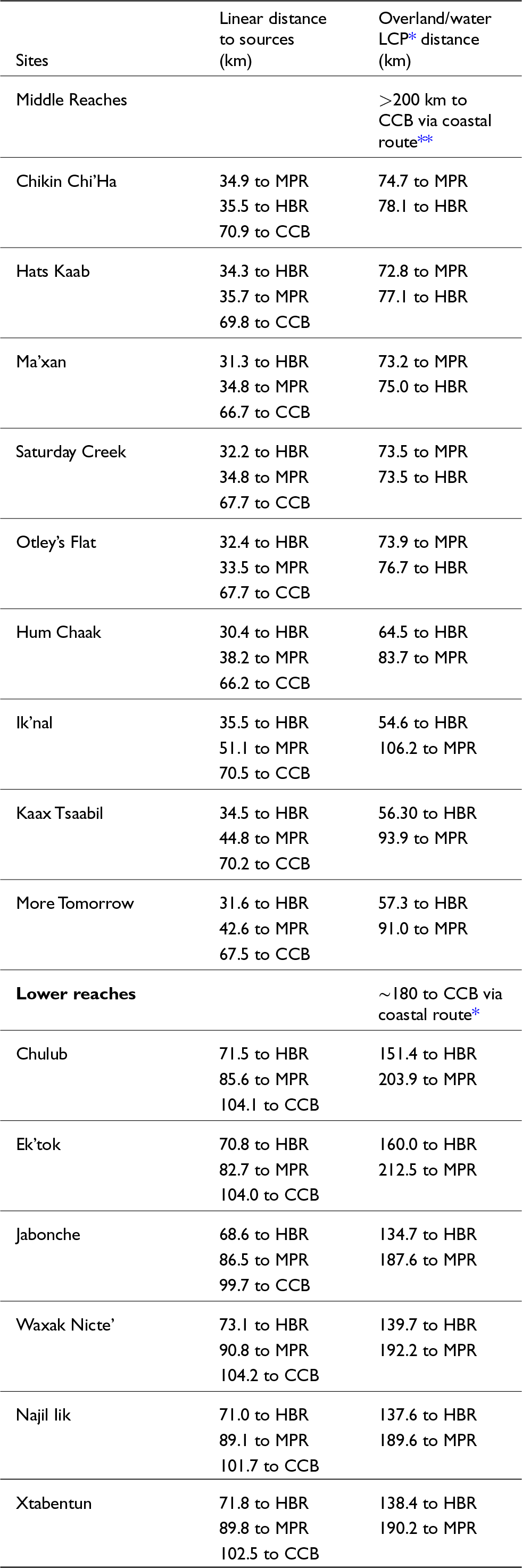

We outline our expectations for the archaeological record based on the three aforementioned exchange mechanisms (Table 1). The variables considered here are: (1) reliance on the nearest granite source, a compound factor that considers granite type (Figure 4); (2) geographic distance overland and via waterways as possible routes connecting sites and source locations (Table 2); (3) presence of a distance-decay trend; and (4) degree of inter-site source variation. For the latter items, we considered the amount of local versus non-local stone in the assemblage (Figure 5) and the variety of granite types within each assemblage (Figure 4). A homogenous sample is defined by 80 percent or more specimens from the same source (following Fertelmes Reference Fertelmes2014:82).

Figure 4. Distribution of ground stone tools by granite pluton from the middle and lower reaches of the Belize Valley. MPR = Mountain Pine Ridge; HBR = Hummingbird Ridge; CCB = Cockscomb Basin; UNK = unknown. UNK refers to granite that falls within a gray area between MPR and HBR plutons. Further research is needed to clarify where the geochemical boundaries between these plutons lies.

Figure 5. Distribution of non-local versus local sources of ground stone tools from the middle and lower reaches of the Belize Valley.

Table 1. Test variables and expectations of hypothesized mechanisms of exchange

Table 2. Sites considered in this study by distance to sources

Note:* LCP = least cost path; CCB = Cockscomb Basin; MPR = Mountain Pine Ridge; HBR = Hummingbird Ridge..

* Distances to CCB assume coastal route would have been taken. Because these open water distances are approximate, we provide only a general estimate for CCB to move from the source to the middle and lower reaches.

We assume that market exchange among the ancient Maya was relatively open and unrestricted (sensu Freidel Reference Freidel and Ashmore1981:377; Hirth Reference Hirth1998:455; Masson Reference Masson, Masson and Freidel2002:4; Table 1). Market exchange is expected to “increase the volume, diversity, efficiency, and distance of goods moved through the distribution system” (Hirth Reference Hirth1998:455). Reliance on the nearest source is not expected and we assume goods could derive from various sources. However, we expect internal consistency (homogeneity) within and among assemblages from neighboring sites participating in the same marketplace, “as all households will have access to the same sources of supply” (Hirth Reference Hirth1998:461). We should not see a distance-decay trend.

In contrast, if a down-the-line pattern was present, we would expect to see a clear distance-decay trend, in which the amount of granite GST declines in direct correlation with the distance from the source (Table 1; Clark Reference Clark1979:1). With both down-the-line and direct exchanges, we expect to see heterogeneous assemblages reflective of different exchange relationships between individuals/groups (Table 1). For direct exchange, reliance on nearest source is possible but not expected. Due to the lower volume of regular exchanges, the assemblage would be small and inconsistent across neighboring settlements.

Results and discussion

Given the expectations of the models, we evaluated the above variables by site and neighborhood (i.e., when two or more sites are less than 1 km apart). To test the above exchange hypotheses, we explored the range of granite types within assemblages (Figure 4), the distances between granite sources (Mountain Pine Ridge = MPR, Hummingbird Ridge = HBR, and Cockscomb Basin = CCB) and archaeological sites/neighborhoods (Table 2), the proportion of local to non-local stone (Figure 5), and the presence/absence of a distance-decay trend.

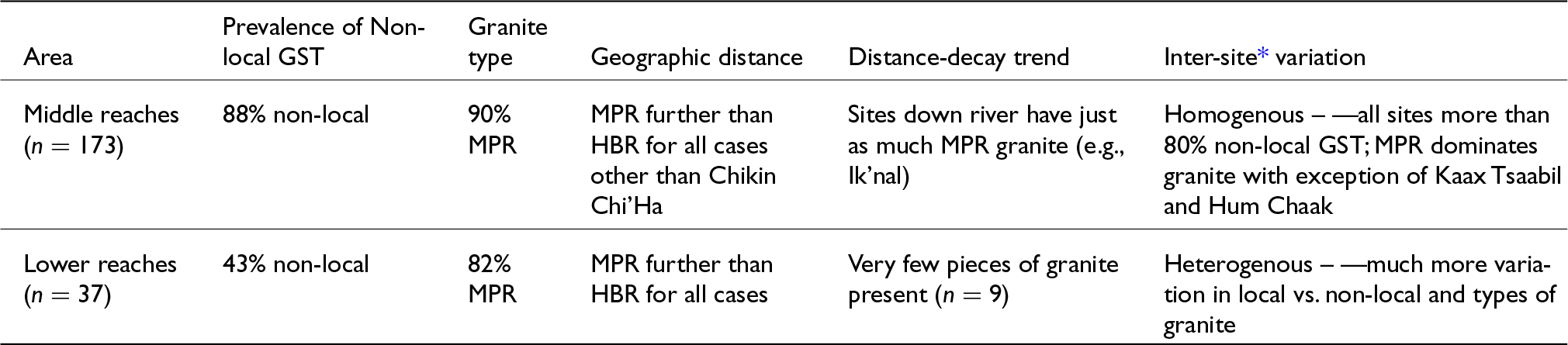

Of the 210 specimens, 173 (82 percent) derive from middle-reaches sites and 37 (18 percent) from lower-reaches sites (Figure 5). Non-local stone comprises 80 percent of the assemblage (i.e., granite, basalt, quartzite, pumice), and 20 percent is local (i.e., chert, limestone, sandstone). These percentages vary distinctly by region: 88 percent of the middle-reaches assemblage is non-local, while in the lower reaches 43 percent is non-local (Figure 5; Table 3). We underscore that similar amounts of time, energy, and funds were expended in excavating sites in both areas, so unequal research bias should be ruled out as a primary contributor to differences in the data.

Table 3. Outcomes of study expectations

Note: GST = ground stone tools; MPR = Mountain Pine Ridge; HBR = Hummingbird Ridge.

* Intra-site variation cannot be ascertained as the BREA project has not had the opportunity to investigate multiple households at a single site.

pXRF analysis of the granite specimens (n = 89) revealed that the majority derive from MPR (89 percent), 8 percent derive from HBR, 1 percent from CCB, and 2 percent are unknown (Figure 4; Tibbits et al. Reference Tibbits, Peuramaki-Brown, Burg, Tibbits and Harrison-Buck2022). MPR granite is the most common stone used for GST in the middle reaches (90 percent) and lower reaches (82 percent). The preponderance of MPR granite at sites in both areas is notable when linear distance to source is considered. While the HBR pluton is closest to both areas in linear distance (mean of 33.1 km to middle reaches [vs. 38.9 km to MPR] and 71.1 km to lower reaches [vs. 87.4 km to MPR]), only 8 percent of the assemblage derives from this source. The demand for MPR granite seems to have overridden the greater transport distances (Table 2). In the lower reaches, MPR is 1.25 times farther in linear distance than HBR, but is four times more common.

A least cost path (LCP) model for moving GST over optimal land/water routes indicates that granite had to be conveyed at least 70 km from the MPR source to the Saturday Creek–Hats Kaab neighborhood (Figure 1; Table 2). To get to sites in the lower reaches, this distance increased to over 180 km. This distance is partially related to the sinuous nature of the Belize River which, while providing perhaps an objectively easier way to raft or ferry quantities of heavy goods like granite downstream, would still have required a time-consuming trip. Overland, the distance is shorter (∼36 km to Hats Kaab and ∼90 km to Xtabentun) but still exceeds the distance of a daily non-stop portage (Feldman Reference Feldman1971:64). To supply a market would have required numerous porters hauling the heavy materials via tumpline, as documented in the Guatemalan highlands (see also Searcy Reference Searcy2011).

Sites in the middle reaches lack any sign of a distance-decay trend for MPR granite, where the majority (75 percent) of GST comes from this non-local source (Table 3; Figure 4). Furthermore, sites downriver (e.g., Ik’nal) have just as much MPR granite proportionately as sites like Hats Kaab and Saturday Creek. However, the data do reveal a marked decline in the overall amount of non-local GST at sites in the lower reaches (43 percent non-local vs. 57 percent local; Figure 5). We can observe from a valley-wide perspective that sites in the middle reaches are very homogeneous in their proportions of non-local/local GST composition, and in the dominance of MPR granite (Figure 4). This contrasts with the lower reaches, where a much more heterogeneous pattern of GST consumption emerges.

While we have not systematically studied intra-site household variation at the community level, we can cross-examine Hirth’s (Reference Hirth1998:456) distributional model in a regional context. From this perspective, we might interpret the homogeneous distribution of the GST assemblages from sites in the middle reaches as indicative of distribution via a centralized marketplace (Table 3). The high quantities of this non-local granite strongly suggest that finished MPR tools were being regularly transported, at least a day and a half’s journey via tumpline or downstream via canoe on the Belize River, to sites in the middle reaches with large open plazas (e.g., Hats Kaab). A centralized marketplace supplying MPR GST would explain the homogenous, high-density distribution where such GST were readily available to all sites located within this “market district” (following Feldman Reference Feldman1971). We assume that the people of the middle reaches primarily exchanged agricultural goods for GST, as vast tracts of ditched and drained wetland fields around Hats Kaab offered more agricultural potential than the local population level required (see Harrison-Buck et al. Reference Harrison-Buck, Willis, Walker, Murata, Burg, Houk, Arroyos and Powis2020).

Returning to Figure 5, the data seem to indicate that down-the-line trade was partially responsible for the slower trickle of non-local GST in the lower reaches. It is perhaps not surprising that the majority (57 percent) of GST in this assemblage was fashioned of local stone, given the distance of non-local sources and how heavy and difficult stone is to transport. Yet, a substantial amount of non-local stone (43 percent) still made its way there. While marketplaces likely existed at sites like Xtabentun, the heterogenous assemblage of GST at sites in the lower reaches suggests non-local GST was not widely available. The limited supplies may have been acquired in more direct reciprocal exchanges between specific trade or gifting partners, rather than at a market open to all. It should be added that such forms of exchange likely also occurred in the middle reaches but may be more difficult to discern with MPR; however, this mechanism of exchange might explain the unequal distribution and lower volumes of other non-local GST like HBR and CCB seen in both the middle and lower reaches.

While we cannot say much about temporal trends in the data considered here (as ceramic analyses are ongoing), we highlight the consistent overall importance of MPR granite through time. The earliest specimen derives from a Late Preclassic context at Hats Kaab and the latest comes from a Postclassic context at Chikin Chi’Ha, both in the middle reaches (Figure 1). Regardless of political upheavals and shifts in economic exchange patterns over this >1,000-year period, the utility and demand for MPR granite appears to have remained constant. The provenience studies of granite GST explored here reveal an enduring relationship between the upper and middle Belize Valley that transcends the economics of efficiency when one considers that other sources like HBR were equally close at hand.

The data also suggest that HBR granite may not have been introduced to the mid-to-lower reaches until the so-called Maya “collapse” period. Of the seven pieces of HBR granite found in the GST assemblages, all came from contexts that appear to date to the Terminal Classic, possibly extending into the Postclassic. The introduction of HBR granite may reflect the arrival of new people and/or new trade routes and relationships that developed during this period of social and political upheaval. Furthermore, the one CCB specimen from Hats Kaab surface collection (topsoil) may also be connected to new trade relations, perhaps reliant on coastal routes as indicated in Figure 1.

Conclusions

Building on important work begun by Elizabeth Graham (Reference Graham1987), this study presents models of lowland Maya trade and exchange of GST. Here, we have applied a set of possible exchange frameworks to geochemically sourced archaeological assemblages from the mid-to-lower Belize River Watershed. Based on the distributional study presented here, we conclude that market exchange was largely responsible for the homogenous distribution of non-local MPR granite in the middle reaches. In the lower reaches, however, market exchange seems not to have been a key distributor of non-local granite. Rather, the heterogenous distribution suggests down-the-line or direct exchange may have been the primary means for procuring such non-local utilitarian goods. In the end, we cannot rule out any one exchange mechanism and recognize that all three types—in addition to many others—likely coexisted in different regions or at different scales of exchange.

This study is a first step in exploring some of the many ways in which GST may have moved across the landscape—from manufacturer to consumer. It lays the groundwork to further theorize the movement of GST and the inherent social complexity of these exchange mechanisms—what scholars describe elsewhere as an object’s “itinerary” (Joyce and Gillespie Reference Joyce and Gillespie2015) or “biography” (Gosden and Marshall Reference Gosden and Marshall1999) and the changing relationships of an object’s “social life” (Appadurai Reference Appadurai1988) through the course of its circulation. By further engaging with the mobility of GST and their range of domestic and ritual contexts, we can begin to understand how these tools mediated mutually constituted and entangled economic and social relations in the past.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.