Throughout Western democracies, the desire for centralization and radicalization of political leadership threatens the stable functioning of societies. Echoing the inter-war era, this phenomenon of gradually integrating autocratic elements into democratic systems is grounded on a dynamic whereby politicians engage in unorthodox activities which gain increasing motivation, exposure and legitimization through public support (e.g. Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2018).

In this study, we examine the conditions for the emergence of more autocratic political leadership in the context of semi-presidential systems, which can be regarded as a particularly relevant context for such dynamics to occur. The most common regime type in Europe (Anckar Reference Anckar2022), semi-presidentialism shares executive powers between a popularly elected president and a government accountable to the parliament, creating the potential for intraexecutive competition and reduced decision-making capacity. In addition to constitutional rules, the intraexecutive power balance depends on informal practices, and presidents can leverage public opinion and popularity to advance their ambitions (Åberg and Sedelius Reference Åberg and Sedelius2020; Grimaldi Reference Grimaldi2023; Hloušek Reference Hloušek2013; Köker Reference Köker2017; Raunio and Sedelius Reference Raunio and Sedelius2020; Tavits Reference Tavits2009). To summarize this dynamic, which includes both formal and informal aspects of political power, we can utilize the popular concept of ‘presidentialization’. The two standard understandings of the concept (as differentiated by Elgie and Passarelli Reference Elgie and Passarelli2019) view ‘presidenzialization’ as a formal-constitutional change towards more presidential rule (Samuels and Shugart Reference Samuels and Shugart2010) and/or a gradual, practice-related and general centralization of executive powers (Poguntke and Webb Reference Poguntke and Webb2005). These two different conceptions capture both sides of the semi-presidential dynamic described above and will therefore be incorporated into our research design. We can also connect institutional presidentialization to public opinion through the work of Thomas Poguntke and Paul Webb (Reference Poguntke and Webb2005), who highlight the ‘electoral face’ – i.e. the personalization of public opinion and votes – as a central aspect of the presidentialization of politics.

Grounded on the inherent fluidity and malleability of the intraexecutive power balance, this study examines an overlooked factor that can shape power shifts in semi-presidential systems: public opinion. We argue that popular demand for stronger presidential leadership, especially when it occurs in tandem with growing dissatisfaction vis-à-vis more cooperative institutions and practices, can lead to the presidentialization of a semi-presidential regime. In systems where the formal balance of power leans towards the parliament and government, such transitions in public expectations can increase intraexecutive tensions and conflicts, while in more president-leaning systems, it may even lead to ‘over-presidentialization’, meaning that the presidency becomes so powerful that the system starts to operate like a pure presidential regime.

To illustrate this dynamic and its potential consequences in a more concrete and broader context, consider a hypothetical situation where the populist Rassemblement National wins the next presidential election in France. Instead of conforming to traditional interpretations of presidential powers and style, the new president could continue to operate in line with the politically divisive and openly confrontational style of their party if the party’s supporters continued to support such a style from the presidential office. This could change the functioning of the French semi-presidential system towards a more presidential practice without the need for any constitutional changes. In time, reflecting the model of delegative democracy where all significant representative capacities are vested in a popularly elected president who governs with complete sovereignty over the other democratic institutions (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell1994), the more presidential operating dynamic can become institutionalized into a standard practice and even formalized as such.

While we do not expect advanced semi-presidential democracies to turn into bona fide delegative democracies, gradual power shifts can occur and they are likely to increase intraexecutive conflicts that will then reduce national decision-making capacity. For example, in Serbia the polarizing discourse of President Aleksandar Vučić has had a negative impact on the already fragile and adversarial political climate (Milačić Reference Milačić2025). In the 2016 Austrian presidential elections, the Freedom Party’s Norbert Hofer challenged the conventionally ceremonial role of the president and campaigned on the premise that if elected he would make active use of the president’s constitutional prerogatives (which are traditionally dormant), and received substantial support for his position (Gavenda and Umit Reference Gavenda and Umit2016). For this reason, we argue that the role of public opinion should be recognized more clearly when considering the factors that may impact the intraexecutive power balance.

Regarding factors that can explain the public demand for ‘presidentialization’, we focus especially on the characteristics of ‘populist voters’, given that a more authoritarian leadership style is a defining feature of populism. Ideal populist leadership is highly centralized and unified, and often refers to a single person rather than a collective such as a party or the government. A populist leader claims to represent voters directly with a confrontational style that undermines established processes and cooperation (e.g. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017). At the level of individual voters, populist attitudes reflect a stark contrast between the sovereign, homogenous, ‘good’ people and the ‘evil’, ‘corrupt’ elite (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014). Populist voting has also been connected to personal psychological features, such as low agreeableness and antiestablishment sentiment (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, Rooduijn and Schumacher2016), which connects to lower levels of political trust (e.g. Geurkink et al. Reference Geurkink, Zaslove, Sluiter and Jacobs2020). While these features do not directly reflect a desire for more authoritarian leadership, the ‘elite’ that populists criticize is typically conceived as a cooperative network of elected and non-elected professional officeholders, to which the highly personalized institution of the presidency offers a clear contrast.

To examine these connections, we present three research questions: (1) Does the Finnish electorate include individuals who support a distinctively powerful and assertive presidency? (2) If so, why do these voters hold such a view (i.e. which individual-level sociodemographic and attitudinal factors connect to this conception of the presidency)? (3) Do such voters also favour the weakening of parliamentary and cooperative political institutions? In addition to introducing and explicating the idea of ‘presidentializing’ a semi-presidential regime through public opinion, we seek to contribute to empirical and methodological aspects of presidency research. Most of the public opinion research on presidencies comes from presidential systems (e.g. the United States and Latin America) and focuses on presidential approval. While presidential approval has also been measured in certain European semi-presidential democracies (mostly France), very few studies have examined citizens’ preferences regarding the powers and leadership style of presidents.

To address this gap, we designed survey questions where citizens were asked about their preferences regarding the president’s powers and operative style in Finland. The nationally representative survey was fielded in February and March 2024, right after the presidential elections. To acknowledge the fact that confrontational behaviour manifests differently in different political cultures, and to maximize the internal validity of our largely explorative effort, we customized our measures in relation to the commonly understood operating principles of the Finnish dual executive. We detail the rationale and construction of our measures below.

The next section presents our theoretical approach that is based on two strands of the literature: one focusing on the president’s leadership role in semi-presidential systems, and the other on voter characteristics that could condition preferences for a more authoritarian form of presidential leadership. The following section introduces our country case and caveats that are important for the overall interpretation of the results. Instead of aiming at empirical generalization, our more modest ambition is to establish the connection between individual-level characteristics and a desire for stronger and more confrontational presidential leadership in a semi-presidential democracy. Finland provides a good context for such an exploration because of its affluent and stable societal conditions and its strongly consolidated parliament-leaning semi-presidential constitution. In the subsequent section, we introduce our data and variables, which we then analyse in the section that follows using various descriptive and multivariate methods. Our results reveal that voters with populist attitudes are more likely to favour a stronger and more confrontational presidency, and that this tendency is related to a willingness to weaken the more parliament-leaning and cooperative political institutions. We conclude by discussing the ramifications of our results for the theoretical, methodological and empirical avenues of future research.

Presidential leadership in semi-presidential systems: alternative roles and support for a stronger presidency

Defining the scope of presidential leadership

In this study, ‘presidentialization’ refers to an increase in presidential capacities vis-à-vis the government with which the president shares executive powers in a semi-presidential regime. Our understanding of the popular term thus generally reflects the conception of David Samuels and Matthew Shugart (Reference Samuels and Shugart2010), which focuses on the constitutionally defined powers of the executive offices and the presidency. From Thomas Poguntke and Paul Webb’s (Reference Poguntke and Webb2005) influential and somewhat different conception of ‘presidentialization’ that also considers the strengthening of prime ministers in parliamentary systems, we add to our understanding of the term the explicit recognition of and emphasis on informal political practices; these may matter even more for the actual functioning of semi-presidential regimes than their constitutional configurations (see Elgie and Passarelli Reference Elgie and Passarelli2019 for a differentiation of the models). In other words, we recognize both formal and informal aspects of power when conceptualizing and measuring ‘presidentialization’. We also borrow from Poguntke and Webb (Reference Poguntke and Webb2005) the idea that the system-level centralization of political power should also be reflected in public perceptions via the personalization of political publicity, campaigning and elections. In this study, we analyse voters’ perceptions on the ideal distribution of power between collective (government) and personalized (president) political institutions, allowing us to draw a fairly direct line between public preferences and institutional dynamics.

While formal constitutional powers set the baseline for a president’s leadership, the president’s overall capacities relate to a broader set of qualities and activities. In his seminal article that introduced the regime type, Maurice Duverger (Reference Duverger1980) classified countries according to the president’s constitutional and de facto powers, but his ambiguous criterion concerning the president’s ‘quite considerable powers’ was soon contested, because its empirical ambiguity led to a variety of ad hoc classifications. Robert Elgie’s (Reference Elgie1999) simpler definition identifies a semi-presidential regime as one that contains a popularly elected fixed-term president existing alongside a prime minister and cabinet responsible to the parliament. This definition reflects that of Matthew Shugart and John Carey (Reference Shugart and Carey1992), who had already defined and classified semi-presidential regimes with less ambiguity, focusing mainly on the distribution of formal executive powers. Subsequent research has predominantly focused on ranking presidents’ formal prerogatives (see Doyle and Elgie Reference Doyle and Elgie2016). Although most scholars recognize that practice may diverge from the formal rules, many have continued to examine how formal constitutional powers affect system-level outcomes such as intraexecutive conflict and regime survival (Åberg and Sedelius Reference Åberg and Sedelius2020). While other factors also condition presidential capacities, constitutional prerogatives form the basis for the overall strength of the presidency (Passarelli Reference Passarelli2015; Samuels and Shugart Reference Samuels and Shugart2010).

However, it is equally important to recognize that a formally powerful president can be weak in practice, depending on their personal style and operative role within the political system (e.g. Anckar and Sedelius Reference Anckar and Sedelius2024; Grimaldi Reference Grimaldi2023). A prominent strand of semi-presidentialism research has recently connected constitutional powers to presidents’ behaviour, asking how formal powers are actually used in practice (Köker Reference Köker2017). As noted by Margit Tavits (Reference Tavits2009: 30), ‘Most commonly, it [presidential activism] is understood as intense use of presidential discretionary powers’; hence, formal powers typically set the foundation for presidential activism. Such activity can refer to the president’s involvement in legislation (especially vetoing bills), government formation (impacting on coalition composition or the nomination of individual ministers), and negotiations with foreign leaders (Amorim Neto and Strøm Reference Amorim Neto and Strøm2006; Köker Reference Köker2017; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2010; Tavits Reference Tavits2009), and presidents can also exert influence behind the scenes in policy processes (Raunio and Sedelius Reference Raunio and Sedelius2025). Within the confines of their formal powers, the president can take a passive or active approach. Employing an illustrative metaphor that Dag Anckar (2000, cited in Paloheimo Reference Paloheimo, Poguntke and Webb2005: 249–250) used to describe the ‘eating habits’ of Finnish presidents at the ‘buffet table’ of constitutional prerogatives, ‘a gourmand’ enjoys the whole variety of offerings with great gusto. As legal norms are open to interpretation, presidents can try to creatively expand their influence, particularly if the government is weak and unpopular (e.g. Hloušek Reference Hloušek2013).

Publicity is a central feature of presidential leadership. Through the partly ceremonial nature of the office that embodies the representation of an entire nation within a single person, presidents enjoy broad media coverage. This publicity enables the president to expand their activities beyond the office’s formal limits (e.g. Grimaldi Reference Grimaldi2023; Kujanen et al. Reference Kujanen, Koskimaa and Raunio2025; Raunio and Sedelius Reference Raunio and Sedelius2025). Presidents perform various formal and informal public activities, such as speeches and interviews and posting on social media, through which they can try to influence the political agenda and exert pressure on government while claiming to act as neutral mediators operating above party politics. Through frequent polling, presidents can learn about citizens’ preferences. Presidents are typically more popular than prime ministers (Kujanen Reference Kujanen2024), and positive feedback can build legitimacy to make more active use of such practices, even non-conventional ones.

To combine the various forms of presidential activity into definable alternative leadership styles whose support we can measure in the empirical analysis, we need to shift the viewpoint from specific presidential behaviour to more general stylistic orientations. Reflecting the above-mentioned notion of the ‘gourmand’, a president’s stylistic orientation is related to the intensity with which they deploy their various powers. Providing a ground-level generalization on which to base our empirical measures, Maarika Kujanen et al. (Reference Kujanen, Koskimaa and Raunio2025) recently differentiated between ‘statespersonlike’ and confrontational presidential styles. The former conceives the president as a mediator who primarily seeks to maintain national unity by enhancing cooperation across parties and political institutions. In terms of public behaviour, the statespersonlike style rests on active moderation, incentivizing the president to refrain from using divisive language and to opt for unifying public messages that emphasize shared attributes and objectives. The confrontational style, on the other hand, sees the president as an independent and active political actor who challenges other political actors and institutions with assertive positioning, divisive language and other openly confrontational tactics. Under semi-presidentialism, this style is often connected to the efforts of the president to compensate for their weaker constitutional position via public activities that seek to undermine the parliament-leaning government. With significant constitutional powers, a president who employs a confrontational style and enjoys public support could, in time, ‘overpresidentialize’ the system.

By combining formal powers and operational style, we can describe a spectrum of leadership roles for presidents in semi-presidential regimes ranging from a formally weak president with a mediating and ceremonial statespersonlike style at one end to a formally strong president with an independent and confrontational style at the other. Naturally, these are the two most extreme categories, which do not represent the whole spectrum of existing cases. A president could, for example, be formally powerful but operationally weak, or vice versa. In this study, we exclusively focus on explaining the popularity of the ‘stronger and more confrontational’ ideal type, as it most clearly reflects a ‘presidentialized’ semi-presidential system, especially when occurring in conjunction with low support for more parliament-based democratic institutions.

Discerning who is more likely to favour stronger and more confrontational presidential leadership

In general, as noted by Selena Grimaldi (Reference Grimaldi2023), presidents are both constrained and enabled by citizens’ expectations. If we also accept that citizens’ expectations regarding political institutions can change in the same way as other public attitudes, then such citizen expectations can induce change in the functioning of political systems. In more concrete terms and reflecting the main argument of this study: if citizens want stronger and more confrontational presidential leadership, such an attitudinal climate can assist the president in maximizing the use of, and in time even extending, their formal prerogatives. For this reason, knowing what citizens want from their representative political institutions – and why – should be considered a question of the utmost practical and theoretical importance.

Studies of public opinion about presidents have mostly focused on the president’s popularity, sometimes also referring to factors which could explain support for certain types of presidential leadership. Most of this research deals with presidential regimes that operate in the United States and Latin American countries, where preferences for a stronger presidency have been connected to higher presidential approval ratings (Reeves and Rogowski Reference Reeves and Rogowski2023; Sievert and Williamson Reference Sievert and Williamson2018) and support for the incumbent’s party (Christenson and Kriner Reference Christenson and Kriner2017), suggesting a political motivation. In other studies, however, attitudes concerning the level and use of presidential powers have been associated with more general values, such as citizens’ opinions about democracy and the rule of law (Reeves and Rogowski Reference Reeves and Rogowski2023), suggesting a more general motivation. In the context of the semi-presidential regimes in France (e.g. Conley Reference Conley2006; Grossman and Guinaudeau Reference Grossman, Guinaudeau, Hellwig and Singer2023) and Portugal (e.g. Aguiar-Conraria et al. Reference Aguiar-Conraria, Fernanded, Magalhães, Hellwig and Singer2023), the president’s popularity has been connected to economic and political conditions (e.g. Hellwig and Singer Reference Hellwig and Singer2023). In a rare effort that explicitly touched on presidential powers, Maarika Kujanen (Reference Kujanen2024) established that presidents who are formally subordinate to the government tend to enjoy higher popularity ratings than constitutionally more powerful presidents. Informed by these studies, in our empirical analysis we control for the impact of political, economic, normative and constitutional factors.

Our main focus is on those factors that can explain an individual’s preference for a formally stronger and more confrontational presidency. As a more one-sided and assertive leadership style is a central feature of populism (e.g. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017), we draw strongly from this broad literature which has identified attitudinal and sociodemographic individual-level characteristics that feed into support for populist parties and a particular democratic style. In general, ‘populist attitudes’ relate to an individual’s critical assessment of, and personal standing towards, traditional democratic practice, which is generally understood as cooperative, civil and stable rule by established political institutions.

A central underlying perception of populist attitudes is the stark contrast between the ‘corrupt’ elite of ‘insiders’ (established political actors) and the ‘good’ or ‘decent’ sovereign people, the ‘outsiders’ (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014). This critical approach to established democratic politics has been associated with more detailed attitudes, such as antielitism fuelled by the deeply held conviction that political elites no longer produce policies that serve the interests of the people (e.g. Geurkink et al. Reference Geurkink, Zaslove, Sluiter and Jacobs2020), or more general antiestablishment sentiment coupled with low levels of trust towards traditional political institutions (e.g. Geurkink et al. Reference Geurkink, Zaslove, Sluiter and Jacobs2020; Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2018), or even more general dissatisfaction vis-à-vis the functioning of democracy (e.g. Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld, Kokkonen, Linde and Dahlberg2021; Zaslove and Meijers Reference Zaslove and Meijers2023). No distinct sociodemographic profile characterizes the voters of populist parties (Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2018), but older and low-educated males residing in non-metropolitan areas tend to display such populist attitudes more often (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Zaslove and Spruyt2017; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017).

Another question is: what do such voters want in terms of political leadership? Although populism is generally conceived to reflect a more authoritarian idea of political leadership, not least due to the personalized and unipolar organization of populist parties (e.g. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017), populist voters have also shown clear support for more direct forms of democracy (e.g. Font et al. Reference Font, Wojcieszak and Navarro2015). As direct democracy has been contrasted with party-based representation, these attitudes may partially reflect a general critique of established (i.e. party-based) practices. However, a genuinely inclusionary variant of populism also exists in Latin America and Southern Europe, which considers political and economic exclusion as a central peril of modern democracy and seeks institutional solutions enabling more inclusive democracy (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2013). Importantly, in the vein of ‘delegative democracy’, we should note that in addition to new political parties and referendums, more inclusive politics could also materialize through centralized leadership by a president who represents the entire nation directly without consulting intermediate actors (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell1994). In European semi-presidential regimes populist attitudes could therefore find expression through the presidency, perhaps exactly because European governments tend to operate on the basis of multi-party coalitions and compromises. Especially in countries with a relatively strong presidency, such as Romania and Lithuania (Doyle and Elgie Reference Doyle and Elgie2016), the strengthening of such attitudes could advance ‘presidentialization’ and intraexecutive tensions.

To summarize, we put forward the first general hypothesis to guide our empirical efforts:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Voters with populist attitudes are more likely to favour a stronger and more confrontational presidency even in the context of a parliament-leaning semi-presidential system.

Based on the aversion of these voters towards established democratic practices, and to provide a stronger test for the first hypothesis, we formulate our second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): ‘Populist voters’ also favour the weakening of more parliament-leaning and cooperative political institutions.

We measure preferences for the presidential leadership role along two scales, one focusing on the president’s formal powers and the other on the president’s operational style, while populist attitudes are gauged using general measures of political distrust and democratic dissatisfaction. To address potential intervening factors, we control our models with sociodemographic variables including gender, age, level of education and left-right orientation. As a novel contribution, we also include a sum measure based on factual knowledge about the president’s constitutional powers to control for informational bias. To account for political bias, we consider the impact of voting for a populist party and the level of support for the incumbent president. We detail our data sources, measures and methods below, after briefly describing the sociopolitical context of our study.

The country context

Until the 1980s, the Finnish president was elected by an electoral college of 300 members, but since 1994 the president has been elected via direct popular vote, where a second round is organized between the two top candidates if none of the candidates receives a majority of the votes in the first round. Each president’s tenure is limited to two consecutive six-year terms.

Regarding the president’s formal powers, the constitution of 1919 left room for interpretation, which President Urho Kekkonen in particular used to his advantage during his quarter-century reign from 1956 to 1981. Leveraging his dominant position in foreign affairs, Kekkonen strongly influenced domestic politics, not least by forming and terminating short-lived coalition governments. Duverger (Reference Duverger1980) ranks Finland first among West European semi-presidential systems in terms of the formal prerogatives of the president, and second only to France in the actual exercise of presidential powers. The balance of authority between the government and the president in Finland was therefore very much in favour of the president until the constitutional reforms of the late twentieth century, which were in part a response to the experiences of the Kekkonen era.

The new constitution entered into force in 2000, but political practice had already been changing in connection with Finland joining the European Union (EU) in 1995 during the presidency of Martti Ahtisaari (1994–2000). Constitutional amendments in 2012 further consolidated the government-leaning model. These constitutional reforms were based on broad elite consensus, with essentially all parties represented in the Eduskunta, the unicameral national legislature, supporting the changes. After Kekkonen’s term the political and administrative elites recognized the need to reduce the president’s involvement in domestic policy, while also ensuring that EU and foreign policies were subject to parliamentary accountability (e.g. Karvonen et al. Reference Karvonen, Paloheimo and Raunio2016; Nousiainen Reference Nousiainen2001; Paloheimo Reference Paloheimo2003; Raunio and Sedelius Reference Raunio and Sedelius2020).

More recent comparative studies rank Finland among countries where the president has only weak formal powers (Doyle and Elgie Reference Doyle and Elgie2016; Elgie Reference Elgie2018). Under the new constitution, the president’s formal competences are limited to co-directing foreign policy with the government and serving as the commander-in-chief of the defence forces. In addition, the president retains some powers of appointment relating, for example, to ambassadors. The government is in charge of domestic and EU policies, and, reflecting the consensual nature of the constitutional reform process, the early twenty-first century saw a clear recognition of the respective jurisdictions of the two executive arms (Raunio and Sedelius Reference Raunio and Sedelius2020).

Three months after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Finland applied for NATO membership and joined the defence alliance in April 2023. President Sauli Niinistö, previously the chair of the conservative National Coalition and elected to his second term in 2018, played a central role in that process (Koskimaa and Raunio Reference Koskimaa and Raunio2025). The incumbent president Alexander Stubb (also from the National Coalition) was elected in early 2024 and his leadership style has been more open and proactive. Media coverage of the president has also increased in the more turbulent security environment.

Despite the constitutional changes affecting the presidency, there has been little systematic research on how Finns perceive the institution. David Arter and Anders Widfeldt (Reference Arter and Widfeldt2010) found that most citizens were happy with the existing constitutional strength of the presidency and that they emphasized the foreign policy dimension of presidential leadership. Only a small share preferred a return to the era of a strong presidency that preceded the constitutional reforms. Regular surveys conducted by The Finnish Business Policy Forum (EVA), which Arter and Widfeldt also utilized, indicate that the proportion of people who want to either retain or increase presidential powers increased somewhat between 1984 and 2022, and that the president has systematically enjoyed higher levels of trust than other political institutions (Metelinen Reference Metelinen2022).

Compared with directly elected presidents in presidential and semi-presidential regimes, recent Finnish presidents stand out with their unusually high popularity ratings (Kujanen Reference Kujanen2024). While in the US context such popularity has sometimes raised desires for a stronger president (Reeves and Rogowski Reference Reeves and Rogowski2023; Sievert and Williamson Reference Sievert and Williamson2018), in Finland these factors do not seem to go hand in hand. The majority of Finns seem to distinguish between the prerogatives of the president and those of the government and confine the former’s role to the special remit of foreign policy. These observations suggest that it should be quite unlikely to find significant support for a stronger and more confrontational presidency in Finland.

On the other hand, there seems to be a significant share of voters with populist-leaning attitudes, as reflected in the rise of the right-wing populist Finns Party. A minor party from its formation in 1995 until the ‘big bang’ parliamentary election of 2011, the Finns Party has consolidated its position among the largest parties and was included in the governing coalition following the 2015 elections. In 2023, it entered the current government led by the National Coalition. In the first round of the 2024 presidential elections the party’s candidate Jussi Halla-aho – the former leader of the Finns Party who for over a decade has been well-known for his strongly divisive views on immigration – came third with 19% of the votes. Although we can only speculate how Halla-aho might have performed in office (as in the similar case of Rassemblement National’s leader potentially occupying the French presidential office), a substantial share of voters indicated their preference for a candidate with an unmistakably populist political platform and a highly confrontational and divisive style. Based on what is known about Halla-aho, it seems quite likely that his selection would have challenged at least to some extent the conventional practices of the Finnish dual executive system, where the president has typically focused on ‘unifying’ themes and stayed out of party-political disputes.

Data and methods

To examine Finnish voters’ conceptions of the presidency, we utilize a specially designed post-election survey carried out in February and March 2024 after the second round of the presidential elections. The respondents (a total of 1,521) originated from a representative sample of 6,000 Finnish citizens eligible to vote and living in mainland Finland. They were approached by letter, and the responses were gathered through paper and online survey forms. The data are weighted to make them more representative of the target population, covering age, gender, education, mother tongue and electoral district distributions in the population, as well as the actual vote shares in the elections. The survey focused both on voting behaviour in the presidential elections and on attitudes towards presidential leadership in Finland (Kujanen and Raunio Reference Kujanen and Raunio2025).

We are interested in explaining support for a distinct type of presidential leadership captured with two specific dimensions of the presidency: formal powers and style of leadership. As we argue, the combination of strong formal powers and a confrontational leadership style is associated with the idea of a populist president who, in the semi-presidential context, may threaten parliamentary processes and the division of power between the two executives. We measure these two dimensions with targeted variables: the first focuses on citizens’ satisfaction with the general level of presidential powers, and the second measures support for a leadership style that stands out from the conventional practice in Finland, where the president does not publicly intervene in government affairs.

In terms of the preferred level of presidential powers, we utilize the following question: ‘Do you think that the president has too much, too little or just the right amount of power?’.Footnote 1 Out of the available response options, ‘too little power’ is interpreted as willingness to increase presidential powers, ‘too much power’ as willingness to decrease it, and ‘just the right amount of power’ as willingness to retain the president’s current powers. To measure the second main aspect of the president’s leadership role, we use the statement: ‘The president should express her/his own political views in public even if they are divisive’ as a proxy for the general leadership style that addresses the dimension between statespersonlike and confrontational leadership modes. In the Finnish context such confrontational behaviour would be unusual, although presidents have occasionally made public statements that have divided opinion. We interpret agreement with this statement as indicating that the respondent supports a more confrontational style, because it emphasizes the president’s public and potentially divisive portrayal of their own political agenda, including the assumption that the president is possibly thereby challenging the government. Conversely, not agreeing with this statement is considered as support for statespersonlike behaviour, with the president building unity by avoiding divisive behaviour.

We combine these two dimensions into a single measurement to produce our dependent variable. It is a dichotomous measure where a value of 1 is assigned if both conditions are met, i.e. the respondent agrees with the confrontational leadership style statement and thinks the president needs more powers (see Tables A1 and A2 in the Supplementary Material online for the coding scheme and descriptive statistics of the dependent and independent variables).

Turning to the independent variables, in light of our theoretical discussion we connect preferences for confrontational presidential leadership to the individual-level factors behind populist attitudes, which generally refer to anti-elitism and the feeling that a corrupt elite manages policy against the interests of the great majority of voters. From this broad-ranging literature we use two relatively common measures as proxies for such sentiments: political distrust and dissatisfaction with the functioning of democracy. We expect both to be associated with general populist attitudes and thereby to increase support for a strong and confrontational presidency.

The first variable is a sum variable, which includes distrust in parliament, government, the prime minister and political parties, with the following question formulation: ‘To what extent do you trust or mistrust the following? Please give your opinion on a scale of 0 to 10 where 0 means “do not trust at all” and 10 means “trust completely”’. These institutions represent the parliament-leaning dimension of the current regime, which outside of foreign policy operates largely as a parliamentary system. The second variable measures the level of satisfaction/dissatisfaction with the functioning of democracy, using the question: ‘How satisfied are you with the way democracy works in Finland?’

In general, the respondents express more trust than distrust in each institution, as the average level of distrust is below 0.5, except for political parties (see Table A2 in the online Appendix). In contrast, only a small proportion of the respondents express distrust in the president, as the average level of distrust is 0.24 (not reported in the table). The reliability of the sum variable was tested with Cronbach’s alpha (= 0.90), indicating high internal consistency. Roughly a quarter of the respondents are either strongly or somewhat dissatisfied with the functioning of democracy in Finland.

We also include several control variables in our analysis. First, gender, age, level of education and left-right orientation as self-placement are included as standard sociodemographic and ideological measures. Second, the level of knowledge of the president’s constitutional powers is included to account for the possibility that views about the presidency could be influenced by the amount of information respondents already have about the president’s role. It is a sum variable, consisting of eight different sources of power. This set of political knowledge questions is novel and, to our knowledge, has not been examined before at this level in the semi-presidential context. In the relatively complex environment of semi-presidential power sharing, it provides a very useful control measure for assessing citizens’ conceptions and preferences regarding the intraexecutive power balance.

Third, voting for the Finns Party enters the regression to test whether including this right-wing populist party in the equation influences the impact of the other factors associated with populist attitudes. As noted above, at the time of the survey the Finns Party was in the government which had been formed in June 2023, while the president represented the other main coalition partner, the conservative National Coalition. Finally, approval of the incumbent president is included in the models to account for the possibility that support for a stronger presidency is dependent on the popularity of the outgoing president, as has been observed in studies of the US presidency (Reeves and Rogowski Reference Reeves and Rogowski2023; Sievert and Williamson Reference Sievert and Williamson2018). There are good reasons to expect this to be reflected in our analysis too, as Niinistö enjoyed very high and stable popularity ratings throughout his 12-year period in office.

In the following section, we begin by exploring the two dimensions of our dependent variable using descriptive methods. After that we test the combined measurement statistically in a binary logistic regression, with a specific focus on factors associated with populist attitudes. This analysis addresses our first hypothesis (H1). The choice of logistic regression instead of linear regression with a continuous dependent variable is based on the notion that the association between support for strong powers and a confrontational leadership style is not expected (or observed)Footnote 2 to be linear. There are many kinds of preferences regarding presidential leadership role, and the strong and confrontational type is one specific scenario that may be described as an ‘extreme’ case, and one in which we are particularly interested as it connects to populist tendencies.

Based on our results and reflecting previous findings regarding Finns’ conceptions of the presidency, it seems possible that one can accept a formally strong president without wishing the president to act in a confrontational manner. This would violate the idea of linearity of the combined measures. Therefore, we estimate the probability of preferring a strong and a confrontational president – instead of other options – while considering factors that may affect this outcome. For validity, we also test the two dimensions (presidential powers and leadership style) in separate logistic regression models to investigate potential differences in their interaction with the explanatory factors. Finally, addressing our second hypothesis (H2), we examine with a simple statistical test if the respondents favouring a stronger and more confrontational presidency would also prefer to allocate less power to the more parliament-leaning institutions.

Results

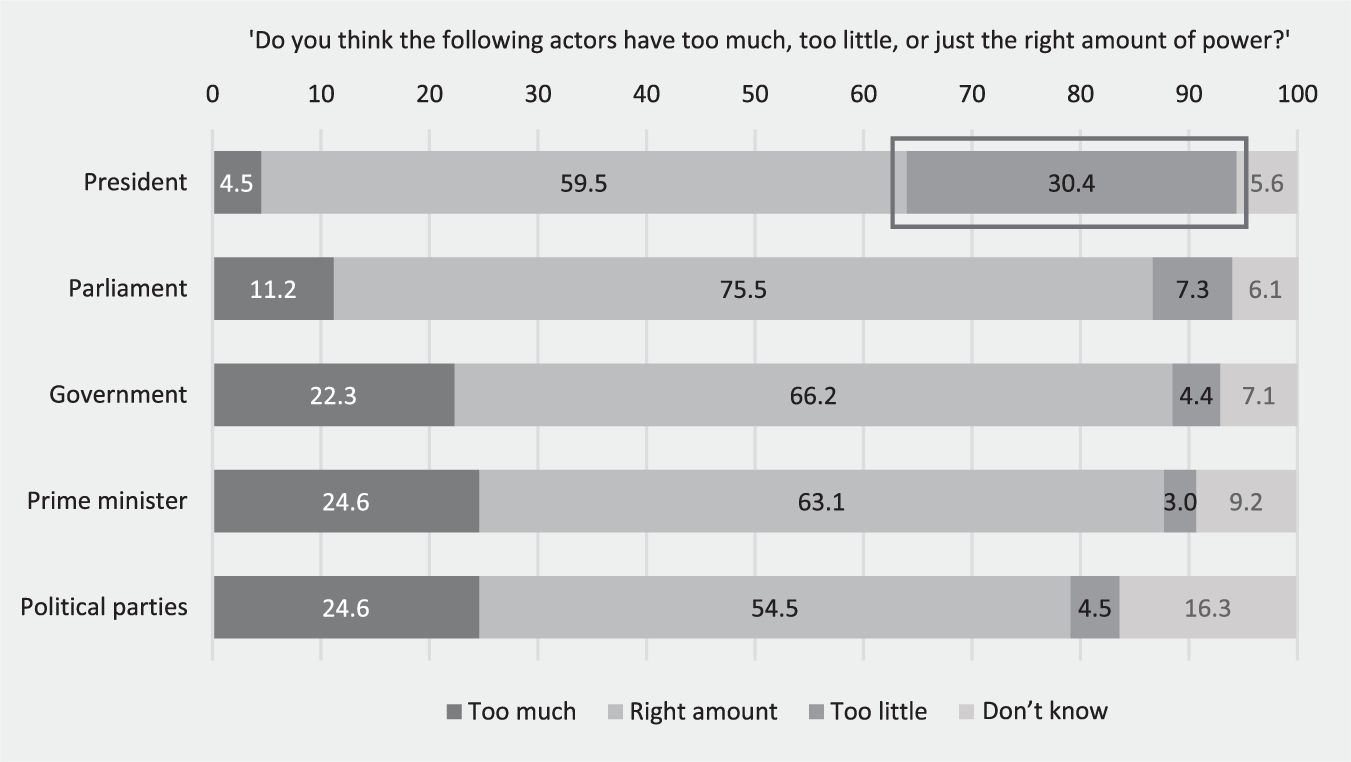

We start with an overview of the two key dimensions of presidential leadership in our data. In comparison with other political institutions – i.e. parliament, government, prime minister and political parties – the president stands out in terms of how citizens view the question of power: almost a third (30.4%) would like to increase the president’s powers, whereas relatively few respondents (between 3.0% and 7.3%) think the same about other institutions (see Figure 1). Still, a clear majority of the respondents are satisfied with the general strength of each institution.

Figure 1. Satisfaction with the Level of Power for Different Political Institutions (%)

Table 1 connects these views with the question of presidential leadership style. First, 38.9% of the respondents agree (11.6% totally agree and 27.3% somewhat agree) with the confrontational leadership style statement (see Table 1). This is a substantial proportion considering that it contradicts the traditional pattern of a ‘statespersonlike’ president, which would be the opposite side of the statement (to unite rather than divide). On the other hand, 51.4% of respondents disagree with the statement (23.9% totally disagree while 27.5% somewhat disagree), which is an even larger proportion. Overall, as in the case of citizens’ views about presidential power, there is a clear variation among the respondents regarding the president’s leadership style.

Table 1. Proportion of Respondents Who (Dis)agree with the Confrontational Leadership Style Statement and Their Distribution Concerning the Question of Presidential Power (%)

Notes: Confrontational leadership style statement: ‘The president should express her/his own political views in public even if they are divisive. Question about presidential power: ‘Do you think that the president has too much, too little or just the right amount of power?’. Pearson Chi-Square test between those who agree and those who disagree: χ2 = 28.36, p < 0.001 (‘don’t know’ responses are excluded from this specific comparison).

Second, on average, among those who prefer the confrontational leadership style, roughly 40% (45.3% among those who totally agree and 36.8% among those who somewhat agree) think that the president should also be more powerful. This is a larger share than among those who disagree with the confrontational leadership style statement, as one would expect. In this latter group, fewer than 30% would increase the president’s power (27.1% among those who totally disagree and 26.8% among those who somewhat disagree). The results of the Chi-Square test (χ2 = 28.36, p < 0.001) reveal that the distribution of the responses in terms of the power variable is statistically significant between those who agree with the leadership style statement and those who do not agree with it. However, a larger share of those who prefer a president making divisive political statements in public still think that the president’s powers should not necessarily be increased, adding some complexity to our story. In other words, the association between these attitudes is not that straightforward. Instead, there is also significant support for a confrontational leadership style that does not require strong formal powers. Here, however, we are specifically interested in voters who desire both stronger powers and a more confrontational presidential leadership role, as that reflects a more populist ideal of the presidency.

Next, we examine the results of the binary logistic regression in Table 2. The analysis consists of three models: (1) a base model with the two key variables that potentially explain support for a strong and confrontational presidential leadership style as the only predictors; (2) a base model with standard sociodemographic and ideological control variables included; and (3) a model with these and the context-specific control variables included. The interpretation of the models is based on odds ratios (OR) indicating the probability that an event (in this case, supporting strong and confrontational presidential leadership) will occur based on the explanatory variables. Any OR greater than 1 means that the event is more likely to occur when the values of the predictor variable increases. For example, OR 3 would indicate that the event is three times more likely with a one unit change in the independent variable.

Table 2. Support for a Strong and Confrontational Presidential Leadership Style. Results of the Logistic Regression Analysis with Odds Ratios and Standard Errors

* Notes: p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The results show that political distrust, and to a somewhat lesser extent dissatisfaction with the functioning of democracy, increase the probability of preferring a stronger and more confrontational presidency. In particular, lower levels of trust in parliament-leaning political institutions – i.e. the parliament, the government, the prime minister and political parties – are strongly associated with support for a more powerful and confrontational president. This suggests that citizens who are generally dissatisfied with the political elite may place their hopes in the president as representing a more independent and hence perhaps more effective political authority. The effect persists and even strengthens when the sociodemographic, ideological and context-specific variables are controlled for in models 2 and 3.

Dissatisfaction with the functioning of democracy is also associated with the dependent variable, yet its effect is statistically weaker and more inconsistent across the models.Footnote 3 In our interpretation, this only emphasizes the complexity of attitudes at the individual level. While some may indeed perceive a strong presidency as providing a solution to problems within the current political system, others may not want to cure the deficiencies of the current regime with a stronger individual leader (i.e. the president). In fact, citizens with higher populist attitudes may not disagree with democratic ideals and, as suggested by the long-standing research programme on democratic preferences, such individuals may support ‘even more democratic’ institutions compared to the current party-based representative model. In other words, populist voters might be dissatisfied with how democracy works, but still express support for democracy (Zaslove and Meijers Reference Zaslove and Meijers2023). In this case, the president may be viewed as one of those conventional democratic institutions, which makes the link between dissatisfaction with the general functioning of democracy and support for a presidency that challenges democratic processes less straightforward.

Some interesting findings emerge with regards to the control variables as well. First, while sociodemographic factors such as age and education did not affect the outcome of the models, broadly reflecting what Matthijs Rooduijn (Reference Rooduijn2018) has found concerning those who vote for populist parties, male gender appeared as a significant predictor. This finding is in line with studies on democratic process preferences which emphasize the differences between female and male voters’ political values and attitudes (e.g. Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Zaslove and Spruyt2017). Second, voting for the Finns Party and leaning towards the political right resonated positively in the model, as one might perhaps expect.

Although this study focuses on a distinct combination of the two aspects of presidential leadership (power and style), we can also assess whether these dimensions differ significantly in terms of their association with the explanatory factors to see whether they both contribute to the overall picture. To do this, we ran separate logistic regression models explaining support for stronger presidential powers and a more confrontational leadership style, which are presented in Tables A4 and A5 in the online Supplementary Material. The results show that the models explaining support for strengthening the presidency (Table A4) perform better than those focusing on the leadership style (Table A5), as all our key variables turn out to be positive and statistically significant in the first model setting but not in the other one. Dissatisfaction with the functioning of democracy only affects the power dimension (see also the differences in terms of the control variables: political knowledge, presidential approval and age).Footnote 4

However, many of the same variables – especially distrust in parliamentary political institutions but also male gender and voting for the Finns Party (factors that perhaps most clearly connect to populist citizens) – resonate with the confrontational leadership style preference, giving it special weight. Therefore, while this test reveals that both the power and the leadership style dimensions are related to the same phenomenon in a similar manner, the model differences confirm that citizens’ attitudes towards these two dimensions are to some extent distinct. This emphasizes the relevance of separating the group of populist-leaning respondents holding strong and norm-challenging expectations towards the presidential office from those with more moderate views about strengthening the presidency.

Finally, to address the possibility that the desire for a stronger presidency is accompanied by support for all political institutions, and to assess whether the observed wish of some respondents for a stronger and more confrontational presidency can be regarded as genuine, we conducted a simple comparison between those who support a strong and confrontational presidency and other respondents regarding their willingness to decrease the powers of the system's more parliament-leaning institutions: namely, the parliament, government, prime minister and political parties. This additional robustness test should demonstrate to what extent support for stronger and more confrontational presidential leadership reflects systematic negative attitudes towards more pluralistic and cooperative parliamentary institutions (see Table 3).

Table 3. Support for a Strong and Confrontational Presidential Leadership Style and Willingness to Decrease the Power of Other Institutions(%)

*** Notes: p < 0.001. Other responses include those who are satisfied with the power of each institution, those who would like to increase the powers, and those who chose the option ‘don’t know’.

Although most respondents are satisfied with the strength of each institution (see also Figure 1), the results in Table 3 clearly indicate that a substantially larger proportion of those who support a stronger and more confrontational presidency are critical about the power of other, more pluralistic and cooperative political institutions, compared to those respondents who prefer a weaker and more statespersonlike presidency. The difference between these two groups is statistically significant for all institutions except political parties – which in cases where a respondent supports one of the existing parties also includes the respondent’s own party, of course. This suggests that our results are not predominantly driven by party-political motivations. Regarding the powers of the parliament and the government, the difference between the groups is about 10 percentage points, and in terms of the prime minister the difference rises to over 20 percentage points. The results of the Pearson Chi-Square tests clearly confirm that these differences are real and statistically robust.

These findings offer further support for the argument that sympathies towards a stronger and more confrontational presidential leadership style might indeed be associated with a general wish to strengthen the presidency – a more one-sided political institution – at the expense of other, more pluralistic and cooperative political institutions. This finding confirms our second hypothesis stating that populist voters also favour the weakening of more parliament-leaning and cooperative political institutions.

Conclusions and discussion

Presidents interested in reshaping the distribution of power in their favour should benefit from public attitudes that support a stronger presidency. This is why we wanted to study public preferences concerning the presidency in the context of semi-presidentialism where support for a more assertive presidential leadership role, especially if it coincides with relatively significant formal presidential powers and scepticism concerning more cooperative political practices, can have serious political consequences.

Our findings show that a substantial proportion of Finnish citizens desire the president to have a stronger and more confrontational leadership style. This can be regarded as somewhat surprising considering the stable and clearly parliament-leaning political system of Finland, where the right-wing populist Finns Party has also twice joined coalition governments during the past decade. This includes the government that was in office when the survey was fielded, reducing the need for populists to signal their discontent via ‘alternative’ institutions.

As demonstrated by the statistically significant tendency of respondents who wish for a stronger and more confrontational presidency to simultaneously favour weaker parliament-leaning institutions, and the fact that our results are not statistically connected to a lack of political knowledge, the desire for a stronger presidency seems to be driven by a genuine wish to alter the dynamics of the political regime. We acknowledge that our findings could be partially influenced by contextual factors. Increased concerns about security following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have elevated the status of the president in Finland, with first Niinistö and then Stubb displaying active foreign policy leadership and receiving extensive and almost exclusively friendly media coverage. In such a turbulent environment citizens may appreciate an individual leader who safeguards the security of the country, irrespective of whether they remember the era of president-led Finland. Nonetheless, our findings are by and large in line with longer-term trends in public opinion (Arter and Widfeldt Reference Arter and Widfeldt2010; Metelinen Reference Metelinen2022), indicating that support among Finns for a stronger president is not dependent on the specific security policy environment.

The regression analysis showed that populist attitudes, especially distrust in political institutions, boost preferences for a stronger and more confrontational president. As we expected, certain sociodemographic and political factors also connect with the desire for such a president (albeit less significantly). Quite intuitively, for example, being male and supporting the Finns Party – and, to a lesser extent, leaning towards the political right – increased support for a stronger and more confrontational presidency.

These findings can be viewed as highlighting a potential threat to democratic stability, since a more ‘populistic presidency’ would alter the operating dynamics of semi-presidential systems. Especially in the case of less institutionalized semi-presidential systems that are less resilient against internal turbulence and perhaps also more prone to situational political opportunism, such attitudes could cause significant harm. While preferences for a stronger and more confrontational presidency do not automatically signal a wish for a bona fide authoritarian regime or suggest that one is around the corner, the populist repertoire from divisive language to the abuse of political power can be dangerous both in the short term and due to its long-term consequences (e.g. Benasaglio Berlucchi and Kellam Reference Benasaglio Berlucchi and Kellam2023; Tsai Reference Tsai2019).

We therefore strongly believe that future research should continue this line of inquiry, and not just in presidential or semi-presidential regimes. In fact, parliamentary democracy, especially in countries with majoritarian electoral systems, can be even more vulnerable to populist leadership tendencies. Scholars could therefore examine preferences for alternative leadership styles in a variety of contexts, focusing on both presidents and prime ministers. It is important that we do not just ask respondents about the preferred level of powers for each institution, but go deeper into conceptions about leadership and modes of behaviour, which clearly seem to be very important for voters and for the functioning of democratic systems.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2025.10030.

Data availability

The survey data used in this study are not currently publicly available, but will be published later in the Finnish Social Science Data Archive.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the workshop ‘Out of Touch? How Political Elites and Citizens Perceive Each Other’ that was held at the 2024 Congress of the Nordic Political Science Association in Bergen, Norway for their valuable comments.

Financial support

The work was funded by the Research Council of Finland, grant numbers: 333013 and 356446.

Disclosure statement

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.