Introduction

Coalition formation is essential to the representational linkages in multiparty parliamentary systems: It fundamentally constrains what parties can and cannot do and their ability to fulfil their electoral pledges. How does coalition formation impact voters' perceptions of parties? Coalitions should be a crucial consideration for voters trying to hold parties accountable, yet we know surprisingly little about how voters perceive coalitions.

Political science scholars have only recently started exploring how voters respond to coalition formation. Fortunato and Stevenson (Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2013) argued that voters perceive parties that govern together as more ideologically similar than they should be based on manifesto positions alone. Fortunato and Adams (Reference Fortunato and Adams2015) showed that the divergence between perceived and advertised positions is highly asymmetrical: Voters map the prime minister's policy onto junior coalition members, but not vice versa. Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Ezrow and Wlezien2016) showed that the same mechanism applies to voters' perceptions of party positions concerning European integration.

These theories have deservedly attracted large scholarly attention, but no work has adequately tested the causal claims. Many other factors can potentially co-vary with changes in public perceptions, raising concerns about omitted variable problems and internal validity. Too much depends on the ability to control for explicit changes in platforms with the manifesto positions. To mitigate such threats to causal inference, I present two survey experiments designed to pinpoint how variation in coalition signals influences voters' perceptions. This is the first paper to provide such a direct test of the theory of coalition heuristics.

In the following section, I describe the current literature on coalition formation and voters' perceptions. I present the shortcomings of observational studies and arguments for an experimental test. Next, I describe the considerations behind the two research designs, before presenting the results. Overall, the experiments find support for the theory.

The signals contained in coalition formation

In multiparty parliamentary systems, parties are simultaneously collaborators and competitors. During the election campaign, parties try to communicate their differences and convince voters about the benefits of voting for them specifically, but between elections, parties must find common ground if they want policy influence. Those parties, which succeed in forming a coalition, will support the same bills in the legislature and defend the same initiatives in the media. How do voters make sense of this behaviour? How do they perceive the ideology of parties involved in coalitions?

Traditionally, researchers have assumed that voters are choosing between individual parties offering separate policy platforms, but research shows that voters are not particularly attentive to shifts in these platforms. Voters are at best changing their perceptions of parties' ideological placement marginally in response to shifts in the parties' policy platforms (Fernandez-Vazquez, Reference Fernandez-Vazquez2014). At worst, there is no significant relationship between the two (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Ezrow and Somer-Topcu2011). This could be because voters are paying attention to elite behaviour rather than policy platforms. A rational voter knows that an individual party will rarely be able to implement all of its policies single-handedly and that government policy represents a compromise between parties, rather than the entire platform of any single party. Thus, if the perceptions of parties' ideological positions should be helpful in guiding vote choice, voters should place more emphasis on parties' actions, collaborations and implemented policies, rather than pre-election promises. Here knowledge about coalition formation can offer a convenient shortcut.

Several recent studies argue that voters incorporate coalition information when estimating the ideological positions of parties and most have used the term ‘coalition heuristics’ to describe this cognitive process (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Ezrow and Wlezien2016; Fortunato & Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2013; Fortunato & Adams, Reference Fortunato and Adams2015; Falcó-Gimeno & Muñoz, Reference Falcó-Gimeno and Muñoz2017; Spoon & Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2017). In short, they argue that a party's status as either a coalition government or opposition member is a cheap and widely available piece of information about the party's ideological position.

There are potentially two complementary ways the coalition heuristic could work (Fortunato & Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2013, pp. 463–465). First, ideological proximity increases the probability of forming the government in the first place: It is easier for parties that are ideologically similar, and not just ideologically adjacent, to negotiate a coalition agreement (Martin & Stevenson, Reference Martin and Stevenson2001). Thus, the choice of a coalition partner reveals the true ideological position of a party net of any ambiguous talk about policy differences. When push comes to shove, who will the party align itself with? Second, once parties have committed themselves to cooperation, they have strong incentives to realize their policy compromise over time. Because coalitions stand and fall together, the coalition members are more motivated to make cooperation work and make compromises along the way, than parties participating in ad hoc cooperation (Ganghof & Bräuninger, Reference Ganghof and Bräuninger2006).

In short, the coalition partner is an important signal about a party's ideological preferences. Coalition formation signals to voters that the coalition members are more ideologically similar, meaning closer in ideological space to one another, than they would have been otherwise (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Ezrow and Wlezien2016; Fortunato & Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2013; Fortunato & Adams, Reference Fortunato and Adams2015). This is the central claim of the coalition heuristic literature and boils down to the following hypothesis: Voters perceive parties as ideologically closer to each other if they can form a coalition than if they cannot.

Identifying causal effects with an experimental test

Does coalition formation have a negative effect on the perceived distance between parties? We can observe what happens to perceptions before and after coalition formation (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Ezrow and Wlezien2016; Fortunato & Adams, Reference Fortunato and Adams2015), and we can compare perceptions of parties in government with parties outside (Fortunato & Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2013). However, we cannot know for certain whether differences in perception, over time or between parties, are caused by coalition formation.

Studies of coalition heuristics suffer from a problem with causal identification. Identifying the causal effect requires comparing a particular coalition formation with a different counter-factual government, holding all the other ways in which party positions are communicated constant. If the differences can be explained by some omitted variable, such as a rapprochement between party platforms and public policy stances, the hypothesized causal relationship between perceptions and coalition formation would be spurious. Defining the counter-factual through the use of control variables is a fiendishly difficult task, in part due to the limitations of existing data. Many of the observational studies rely on national election studies, where voters' perceptions are surveyed every few years. Because the time interval between measurements is so large, it is impossible to sufficiently control for all changes in policy and rhetoric between observations.

Previous studies have attempted to solve the omitted variable problem by using manifesto positions as a proxy for the advertised policy positions of parties. This use of manifesto data is standard in the literature, but it is problematic because manifesto data only represent the positions that parties are strategically choosing to communicate to voters. Manifestos are designed to frame the party in a positive light. and thus they are unlikely to convey any type of dissent or compromise (Marks et al., Reference Marks, Hooghe and Bakker2007, p. 27). The manifesto data do nothing to control the many external sources of parties' reputations. Additionally, they risk overestimating the ideological distance between governing parties that portray themselves as more extreme to pre-empt discounting their policy positions (Bawn & Somer-Topcu, Reference Bawn and Somer-Topcu2012).

Other complications stem from the problem that it can be difficult to assess exactly when coalition formation occurs, that is whether the treatment has been administered. Parties have established coalition reputations that are reinforced over time (Debus & Müller, Reference Debus and Müller2014), but they also announce their coalition preferences ahead of the election (Gschwend, Reference Gschwend2007) or even form pre-electoral coalitions (Golder, Reference Golder2006). Consequently, there are few, if any, naturally occurring coalitions that represent genuine external shocks. Thus, comparisons between parties are complicated by their various historical alliances.

Finally, the existing observational research is prone to a bias of scales. While the survey item capturing ideological placement is consistent, the specific way that respondents interpret the left/right dimension might vary considerably across time and place. Thus, it is difficult to know whether the variation in the dependent variable is caused by coalition formation or due to varying contexts.

Experimental research does away with the omitted variable problem by drawing on the power of random assignments of participants to variations of the independent variable. Because treatments are randomly assigned and contextual factors fixed, any systematic variation in perceptions can be attributed to the specific treatment. While experimental studies are praised for their internal validity, they sometimes lack external validity. However, the generalizability of experimental results can be established through the accumulation and convergence of several studies. Scholars should compare results and assess whether the findings are consistent across contexts, measures and treatments.

Previously, Falcó-Gimeno and Muñoz (Reference Falcó-Gimeno and Muñoz2017) have tested the effects of pre-electoral coalition signals experimentally in the context of the 2015 Spanish regional elections. The experiments in this paper were built into a survey conducted in Denmark in April and May 2018. Denmark is a ‘most likely’ case for studying the effects of coalition signals since voters have great experience thinking through various coalition scenarios. Coalition formation is always a key topic during Danish election campaigns, and party leaders make their coalition preferences known. Meanwhile, the number of parties is such that many different constellations are possible and the outcome fairly open.

Unlike Falcó-Gimeno and Muñoz (Reference Falcó-Gimeno and Muñoz2017), these two studies use direct treatments in which participants are explicitly asked to consider hypothetical scenarios. Thus, the survey prompts do not hide that participants are being exposed to new information. The two studies differ in terms of the parties involved: study 1 uses various real-life existing parties and averages across them, while study 2 uses a hypothetical new party. Since the emergence of new parties is a regular occurrence in Danish politics, especially in recent years, it should not strike participants as unfamiliar or unrealistic.

Experimental designs: Hypothetical coalition scenarios

The experimental designs assume that the important signal contained in coalition formation is whether two parties can cooperate or not. Participants were asked to make judgements about party positions based on different hypothetical coalition scenarios. A key feature of Danish politics is that coalition formation is structured around two clearly defined blocs which represent government alternatives. The prime minister is quite predictable because it is determined by the bloc of the median legislator. A social-democratic prime minister is usually replaced by a liberal minister and vice versa (Green-Pedersen & Thomsen, Reference Green-Pedersen and Thomsen2005). I take advantage of this pattern by making either the Social Democrats or the Liberals issue coalition signals to parties that would pull them either left or right. Additionally, the Danish political system is very fragmented with nine parties represented in parliament, which opens up a wide range of possible coalition constellations.

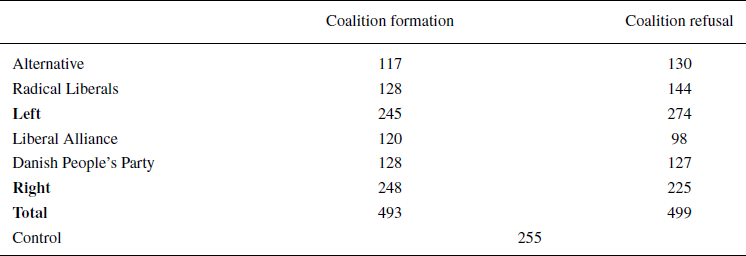

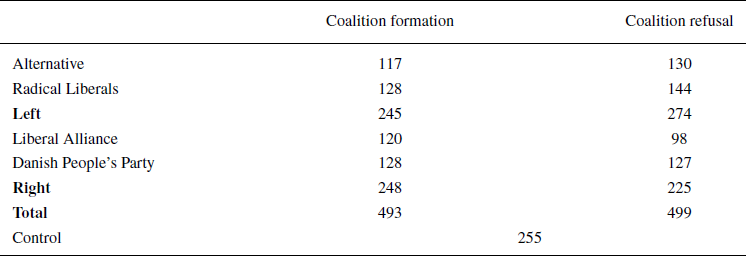

In study 1, participants were randomly divided into a ‘coalition formation’ condition (2/5), a ‘coalition refusal’ condition (2/5), or a control group (1/5). The breakdown of the sample is described in Table 1.Footnote 1 Participants in the control group were asked to place all parties currently represented in parliament on the left-right scale and immigration, economic, environmental and ‘law and order’ issues. The remaining participants were exposed to different hypothetical scenarios concerning existing parties. Participants received a positive signal (‘a coalition has formed') or a negative signal (‘a coalition cannot possibly form') issued by the Liberals.

Table 1. Study 1 sample size according to experimental treatments

Subsequently, participants were asked to place all parties in the party system on five scales as if the coalition scenario was real. The four issue scales were chosen in part because they reflect the conventional issue ownership of the potential coalition members,Footnote 2 and in part because they allow comparison with the Danish National Election Study. Aside from Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Ezrow and Wlezien2016) and Hjermitslev (Reference Hjermitslev2020), this study is the first to explore the effect of coalition signals on specific issue dimensions. To avoid survey fatigue associated with filling out batteries multiple times, the research design is a post-test between groups.

Hypothesis 1 Participants who receive a ‘coalition formation’ signal will perceive the Liberals and the party invited into government as ideologically closer to each other, compared to participants who receive a ‘coalition refusal’ signal.

Many voters will have sufficient experience with the coalition formation process to infer whether a particular constellation is realistic or not (Meffert et al., Reference Meffert, Huber, Gschwend and Pappi2011). On the one hand, this means that the experimental stimuli might be too realistic to elicit any response: Participants might not feel that they learn something new. On the other hand, if the experimental stimulus deviates too far from established notions, it might be discarded as confusing, nonsensical, or simply unrealistic and participants might not engage with it much. To alleviate this problem, the treatments varied in terms of the specific parties involved. As a consequence, some coalitions would be familiar and some completely novel.

The signal was directed towards one of four minor parties: two right-wing (Danish People's Party (DF) or the Liberal Alliance (LA)) and two centrist (Radical Liberals (RV) or the Alternative (AL)). Neither party would realistically obtain a majority together with the Liberals, so participants would have to imagine a minority coalition or a coalition involving a third party. The four minor parties were chosen primarily because the notion of them collaborating with the Liberals was not entirely unlikely (LA being the most realistic and AL the least), and, second, because they represent very different types of parties in terms of history, issue profiles, party organization and past relationship with the Liberals. Right-wing parties are inside, while left-wing parties are outside the Liberals’ bloc. By incorporating this variation into the treatment, I can generalize the results beyond any particular pair of parties and increase the external validity of the study. The treatment material is included in the Online Appendix.

During this period, Denmark was governed by a minority coalition consisting of the Liberals, the Conservatives and LA with the support of the larger DF. The liberal prime ministers have been relying on the parliamentary support of DF since 2001, and almost two decades later many felt that it was time that DF realized their coalition potential and claimed cabinet seats. External support parties are often associated with the policies of a minority government and vice versa (Hjermitslev, Reference Hjermitslev2020), but voters might still perceive formal coalition members to be ideological closer than informal support parties. We can explore that by comparing treatment effects of LA with those of DF.

Prior to 2001, the Liberal-Conservative governments had for a long time relied on centre parties. Between 1980 and 2000, only two governments were able to form without the support of the centre parties. Thus, voters with a good memory might consider a centrist coalition formation a realistic possibility. In 2018, the only original centre party still in parliament was the RV. However, in 2013 a former RV minister split from the party and formed AL. Although generally considered a left-wing party, AL claimed to do away with ‘politics as usual’ and ideological constraints, which left the party somewhat ambiguous in terms of coalition preferences.

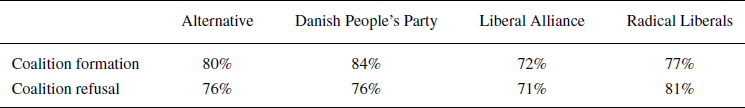

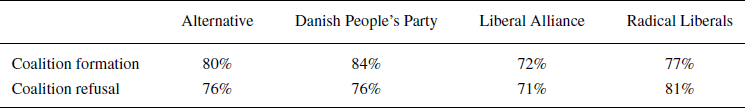

After participants placed all existing parties on multiple ideological scales, they were asked a simple attention check: Could they recall which two parties they had just read about? Luckily, as seen in Table 2, the vast majority could. While this is no guarantee that the participants found the assignment meaningful, it at least assures us that most did read the treatment material.

Table 2. Percent of participants in each treatment group who could recall the stimulus material

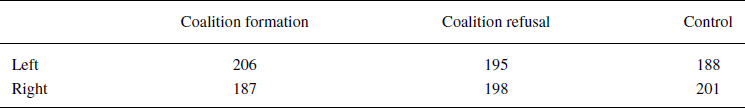

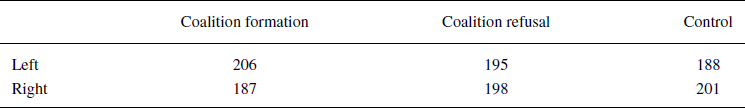

For study 2, all participants were asked to imagine a new party, the Reform Party, which would run in the next election. A new hypothetical party obviously comes with the great advantage that participants have no recollection and thus no lingering effects of the party's track record of coalition formation. Based on random assignment (see Table 3), participants were told that the party was in the range located either left or right of where the individual participant had previously placed the Social Democrats. In this study, the Social Democrats issue the signal. The perceptions of the Social Democrats might be affected by the previous treatment (less so than the Liberals), but this is unproblematic because treatments are randomized again.

Table 3. Study 2 sample size according to experimental treatments

Participants were randomly assigned to a new ‘coalition invitation’ condition (1/3), a ‘coalition refusal condition’ (1/3) or the control group (1/3). Study 2 thus included two independent factors: the direction and the coalition signal, combined to form a two-by-three design yielding six conditions in total. The control group received no information beyond the tailored ideological range. The two treatment groups receive either a positive or a negative coalition cue, which according to the theory of coalition signals should affect participants’ best guess about the ideological position of the hypothetical Reform Party. The treatment material is included in the Online Appendix.

Hypothesis 2 Participants who receive a ‘coalition invitation’ signal will shift their perceptions of the new hypothetical party closer to the Social Democrats, compared to participants who receive a ‘coalition refusal’ signal.

Tailoring the treatment using background information does not violate experimental control if the tailoring rule is applied systematically, but it has the downside that some participants will be very constrained in where they can place the hypothetical party. This does not harm my ability to causally identify the effect, since the problem affects the control and treatment groups equally. However, potential treatment effects could be suppressed for these outliers. An analysis of the two-thirds who placed the Social Democrats between 3 and 7, is included as a robustness check in the Online Appendix.

I am solely looking at between-subjects effects, that is comparing the average placement of groups that received different treatments and the control group. A total of 1247 computer-assisted web interviews of Danish citizens 18 years and older were completed in April and May 2018 by Lucid.Footnote 3

Study 1: Real parties in a hypothetical scenario

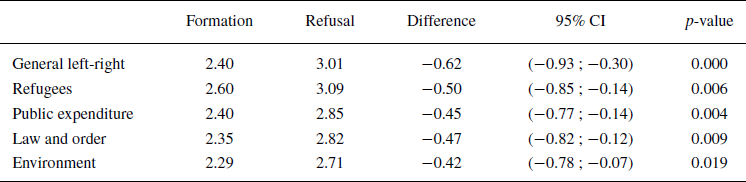

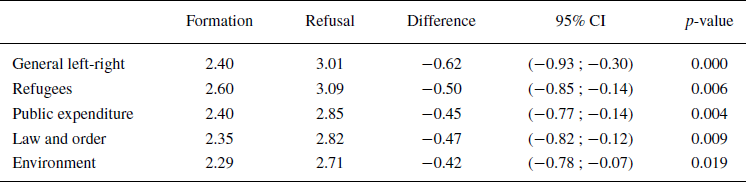

According to Hypothesis 1, the perceived ideological distance between the Liberals and the coalition partner should be significantly smaller if the parties form a coalition than if they cannot. Table 4 shows the average perceived ideological distance after the two experimental treatments and the results of a t-test of difference in means across groups. The four parties were selected because they all represent potential coalition partners. Thus, it is possible to look at the average effect of the two treatments.

Table 4. Difference in mean perceived distance between Liberals and coalition partner

On the general left-right dimension, the perceived ideological distance decreases by 0.6 units on an 11-point scale when parties form a coalition compared to when they cannot. This is approximately equal to the effect estimated in observational studies by Fortunato and Stevenson (Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2013). Study 1 also included party placement batteries on more specific issues: immigration, economy, crime and the environment. When conducting the same analysis along these four issue scales, I find similar, although slightly weaker, effects. On all issues, Liberals and the potential coalition member are perceived as more similar when they can cooperate. This finding offers strong support for Hypothesis 1.

It is possible to disaggregate the numbers and look at each of the potential coalition partners separately. A t-test of difference in means (refer to the Online Appendix) shows that as expected there is a negative effect of coalition formation on the perceived ideological distance between parties. However, the effect is only significant at the 0.05 alpha level for the Radical Liberals (RV) and at the 0.10 alpha-level for the Alternative (AL) and the Danish People's Party (DF). For the Liberal Alliance (LA), which was already a coalition member at the time of the survey, there is no significant effect.Footnote 4

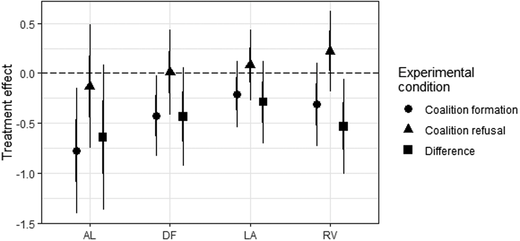

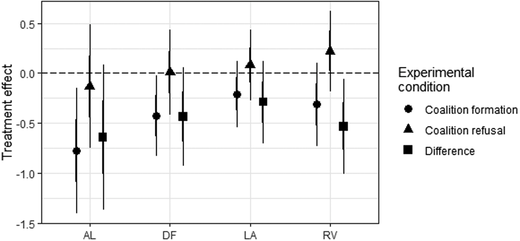

Figure 1 illustrates the effect of the ‘coalition formation’ and ‘coalition refusal’ treatment on the perceived distance between the Liberals and each of the four parties included in the treatment. Generally, the direction of the results supports the hypothesis. Participants perceive the parties as closer to the Liberals when they are considering a scenario where the parties have already joined a coalition government. For instance, participants in the ‘coalition formation’ condition on average placed RV and the Liberals 0.3 units further apart than participants in the control group, while participants in the ‘coalition refusal’ condition placed them 0.2 units further apart.

For DF, there is absolutely no effect of ‘coalition refusal’, which indicates that the control group, rightfully, believes that the Liberals refuse to formally coalesce with their external support party DF. Meanwhile, the strong significant effect of the ‘coalition invitation’ suggests that including them formally in the coalition would impact perceptions. The Online Appendix includes treatment effects on specific issues.

Figure 1. Treatment effects on the perceived left-right distance between Liberals and partners. Estimates ± 1 and 2 std. dev.

Finally, another way to analyse the same data is to consider treatment effects on perceived positions of individual parties. More specifically, one can examine the different effects on the perceived position of the Liberals. On the one hand, one would expect perceptions of the Liberals to move towards the right when their coalition partner is right-wing (DF or LA) and towards the left when their coalition partner is left-wing (RV or AL). On the other hand, previous research has shown that coalition formation mainly affects the perceptions of junior coalition partners (Fortunato & Adams, Reference Fortunato and Adams2015), which suggests that the prime minister's party, the Liberals, is largely unaffected.

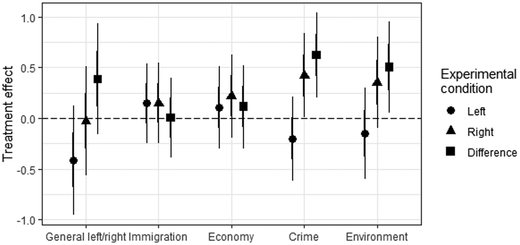

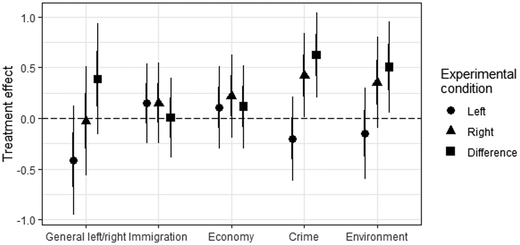

Figure 2 plots the difference between receiving a ‘coalition formation’ treatment that involves either a right-wing or a left-wing partner. Most of the treatment effects are statistically insignificant. The Liberals are approximately one-third of a unit further to the right when they cooperate with a right-wing rather than a left-wing coalition member, which is insignificant. There are even smaller effects on immigration and economy, but there are significant differences in crime and environmental issues. On ‘law and order’, there is a significant treatment effect such that the Liberals are perceived as harsher by respondents exposed to a right-wing coalition member compared to the control group. Most often the change in distances described in Table 4 is caused by movements of the potential coalition partner, not by the prime minister's party, but it depends on the issue.

Figure 2. Treatment effects on the perceived positions of liberals. Estimates ± 1 and 2 std. dev.

Study 2: Hypothetical party

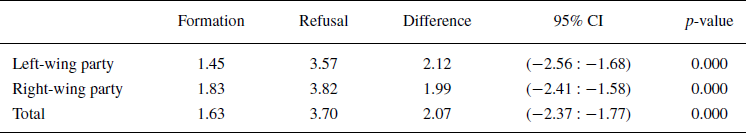

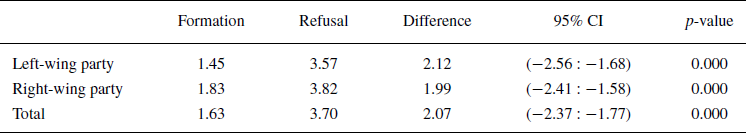

Table 5 shows a t-test for the difference in the mean perceived distance between the Social Democrats and the new hypothetical party. The results are shown for the left-wing and right-wing conditions separately and the total sample. In all instances, I find strong significant results in the expected direction. Being informed that the Social Democrats have a strong wish, rather than no wish, to form a coalition with the new party, motivates survey participants to place it approximately two full units closer on an 11-point scale.

Table 5. Difference in mean perceived distance between the hypothetical party and Social Democrats

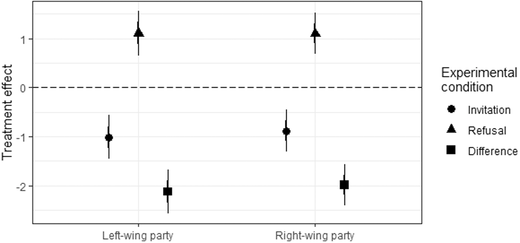

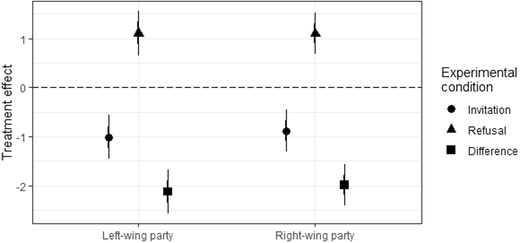

Figure 3 plots the effect of being the ‘coalition invitation’ and the ‘coalition refusal’ treatment compared to the control, as well as the difference between treatment effects. For both versions of the Reform Party, there is a negative effect of the ‘coalition invitation’ treatment and a positive effect of the ‘coalition refusal’ treatment and these two effects are significantly different. In line with the hypothesis, voters place a party closer to the Social Democrats when they can cooperate than when they cannot. Furthermore, participants in the treatment groups were more willing to engage with the question and place a hypothetical party, which clearly suggests that they found the extra information useful.

Figure 3. Treatment effects on the perceived distance between the hypothetical party and social democrats. Estimates ± 1 and 2 std. dev.

Conclusion

This paper examines whether coalition formation has a causal effect on the perceived ideological distance between coalition members. In short, it does. The two survey experiments both entail a direct treatment in which participants are explicitly asked to make judgements based on hypothetical scenarios. A large centrist party is issuing either a positive signal that a coalition can form or a negative signal denying the possibility of a coalition with a minor party. The effects of these treatments are in the hypothesized direction, and they are generally statistically significant.

In study 1, I find a significant negative effect of approximately half a unit of the ‘coalition formation’ treatment on the perceived distance between the Liberals and the potential coalition partner on the left-right dimension but also on various issue dimensions. This is a sizeable effect in an already crowded party system. In addition, the results suggest that the perceptual movement affects the smaller potential coalition members and not the prime minister's party.

In study 2, I also find support for the hypothesis that coalition signals impact voters' perceptions of party positions. There is a statistically significant difference between the ‘coalition invitation’ and ‘coalition refusal’ treatments for both left-wing and right-wing hypothetical parties. This means that participants place the new party closer to the Social Democrats if the two parties can form a coalition together, than if they cannot.

Taken together these experimental results provide convincing empirical support for the causal mechanisms suggested by the theory of coalition heuristics (see, e.g. Fortunato & Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2013) and show that voters' perceptions of parties are affected by cooperation with other parties. Furthermore, they offer refinements. The effects are generally stronger for potential junior coalition members than for large parties (Fortunato & Adams, Reference Fortunato and Adams2015) – even if the large party issues the signal, but this varies issue by issue. This allows for coalition building based on tangential preferences, where junior members are perceived as influential on particular issues.

The results show that not only the actual coalition formation event but also one-sided pre-election signals about future cooperation can move voter perceptions. Strategic parties might use coalition signals to position themselves advantageously but should know that these signals simultaneously impact how potential allies are perceived. Whether they are coalition members or support parties matters. More research is needed to establish how this phenomenon affects both voter behaviour, for example, voters' ideological self-placement or vote choices, and elite behaviour, for example, the government's policy agenda or parties' willingness to collaborate.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Herbert Kitschelt, Christopher D. Johnston, Georg Vanberg and Rasmus Skytte, as well as three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions. This research has been funded by Duke University with an Alona Evans research grant. Replication files are available at idahjermitslev.com

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1: Socio-demographic composition of the sample: gender, age, education, and vote choice at the 2015 parliamentary election.

Table D1: T-test for difference in mean perceived distance between Liberals (V) and each potential coalition partner on the general left-right dimension.

Figure E1: Treatment effects on perceived distance between Liberals (V) and other parties on specific policy issues.

Figure F1: Effects of the coalition formation treatment on perceived position on the general left right dimension.

Figure H1: Treatment effects on perceived left/right distance between Liberals and partners for different demographic groups.

Table I1: Average placement of hypothetical party.

Figure J1: Treatment effects on perceived distance between the hypothetical Reform Party and the Social Democrats (SD).