Inequality and Volunteering

Patterns of inequality in volunteering are evident in many different regions of the world, with certain categories of individuals being more prone to volunteering than others (Wilson, Reference Wilson2012) and more likely to occupy the most important positions within organisations (Wilson Reference Musick and Wilson2008). Such inequalities are related to many different individual traits like subjective dispositions, life-course phases, gender, race, and social context (Wilson, Reference Wilson2012). In general, high-status groups are more involved in volunteering than low-status groups, with educational status as the most consistent predictor of volunteering (Wilson, Reference Wilson2000, Reference Wilson2012). Although less consistent, income and occupational status are often found to correlate positively with volunteering (Pearce, Reference Pearce1993; Tang, Reference Tang2006; Wilson, Reference Wilson2012) as well as homeownership (Rotolo, et al. Reference Rotolo, Wilson and Hughers2010). Furthermore, patterns of inequality can also vary between different fields of volunteering, which also represent diverse functions of civil society (Meyer & Rameder Reference Meyer and Rameder2021).

Although the recruitment of resourceful volunteers can be beneficial for civil society organisations (CSOs) and recipients of services, inequality in volunteering is unfavourable in several respects. From a political and democratic perspective (Rokkan, Reference Rokkan1987; Rueschmeyer et al., Reference Rueschmeyer, Rueschmeyer and Wittock1998), systematic inequality among members and those active in CSOs may contribute to a democratic deficit where certain groups, voices, and interests are less represented and fought for by CSOs. From a social integration perspective, CSOs are considered central arenas for building community, trust, and social networks, facilitating integration in local communities (Putnam, Reference Putnam1993, Reference Putnam2000; Warren, Reference Warren2000). The absence of certain types of individuals and groups in CSOs could indicate a lack of social integration. From an individual-centred and instrumental perspective, participation in CSOs is often argued to provide access to several types of beneficial resources, knowledge, and competences that can be used in other social arenas and life situations. For instance, research has found that volunteering helps connect vulnerable groups to welfare services (Gilbert et al. Reference Gilbert, Holdsworth and Kyle2018; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Springett, Croot, Booth, Campbell and Thompson2015) and can contribute to the improvement of individuals’ physical and mental health (Salt et al., Reference Salt, Crofford and Segerstrom2017; Yeung et al., Reference Yeung, Zhang and Kim2017). Quist and Munk (Reference Qvist and Munk2018) have found that volunteering increases human and social capital among people in the early stages of their working lives, which in turn allows them to command a higher wage in their paid work. However, such observed benefits from volunteering can be caused by the self-selection of resource-rich individuals into volunteer work, as indicated by Petrovski et al. (Reference Petrovski, Dencker-Larsen and Holm2017) regarding employability benefits from volunteering, and Wilson et al. (Reference Wilson, Mantovan and Sauer2020) regarding higher wages among volunteers compared to non-volunteers.

Inequality in volunteering can also be argued to create new, or reinforce, existing inequalities. In line with the so-called Matthew effect (Merton, Reference Merton1968), voluntary engagement may widen the gap between high- and low-status groups, potentially infusing the already resourceful with more resources and benefits. Volunteering may, for instance, enhance individuals’ existing resources through reputational gains from formal positions in CSOs (Handy et al., Reference Handy, Cnaan, Hustinx, Kang, Brudney and Haski-Leventhal2010; Wilson & Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick1997, p. 709), while the less resourceful are blocked from such benefits (Ruiter & De Graaf, Reference Ruiter and De Graaf2009). Van Ingen (Reference van Ingen2009, p. 144) found that privileged citizens, who do not necessarily need the benefits from volunteering, are those most likely to volunteer and occupy the most important positions in CSOs. In other words, it seems like the individuals and groups who could benefit the most from volunteering are often the ones least likely to participate.

In this article, rather than perceiving such inequalities as the result of active individual choices to participate or not participate, I utilise Pierre Bourdieu's theoretical and methodological approach to direct attention towards how individuals’ social position, in accordance with their holdings of different types and amounts of capital, can restrict or promote access to volunteering arenas and the potential benefits from participation. Applying such a perspective to inequality in volunteering will supplement the dominant individualised approach found in volunteering research. Using the related MCA method of data analysis, this will also contribute to a new perspective on how the interplay of different forms of capital creates inequalities in volunteering fields and practices.

A Bourdieusian Approach to Inequality in Volunteering

A key insight from the work of Pierre Bourdieu is that individuals’ unequal access to different forms of resources, both in composition and total volume, determine their position in a social hierarchy, and hence their ability to influence their own life situation (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1993). As such, social inequality is at the core of Bourdieu’s theory of practice (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1977, Reference Bourdieu and John1983, Reference Bourdieu1984), with central and interlinked concepts such as capital; habitus; social space and fields; and rules/structures of the field.

Bourdieu distinguished between several forms of capital that are distributed unequally in most societies: economic, cultural, social (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu and Richardson1986) and symbolic capital (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu and Richardson1986, Reference Bourdieu1996). Economic capital concerns economic resources like income, ownership, and fortune—an individual's possession of, or access to, monetary resources. Cultural capital concerns resources in the forms of knowledge, competence, taste, preference, and practice. Cultural capital may be objectified as art or literature collections, institutionalised as educational degrees, or embodied as cultural taste, practice, interest, and preference. Different cultural preferences, forms of knowledge and taste are hierarchically structured and assigned different values and status. Social capital is related to an individual's social network, friendships, and acquaintances, and to what extent individuals may access resources, benefits, or advantages through these social relations.Footnote 1 In a Bourdieusian perspective, social capital denotes belonging to certain groups informally, but also institutionalised relations in the form of club or organisational memberships. Bourdieu also developed the concept of symbolic capital, understood as any type of trait, characteristic, or form of capital that when perceived and recognised by other actors as valuable, attains a symbolic effect, providing reputation, prestige, or status to the capital holder, for instance, honour (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1996, pp. 61–62, 89). Furthermore, the different forms of capital are convertible with each other under certain conditions (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu and Richardson1986).

In a Bourdieusian approach to volunteering, an actor’s capital volume and certain compositions of capital can increase access to CSOs and opportunities to attain certain positions in CSOs, which may further reinforce the actor’s competences, reputation, or prestige (Meyer & Rameder, Reference Meyer and Rameder2021; Handy et al., Reference Handy, Cnaan, Hustinx, Kang, Brudney and Haski-Leventhal2010; Wilson & Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick1997, p. 709). As such, capital possession can be self-reinforcing (Merton, Reference Merton1968). In being recruited as a volunteer by virtue of social networks and competences, social and cultural capital can be transformed into symbolic capital, strengthening volunteers’ opportunities within CSOs, between similar CSOs, and possibly also between different organisational and social fields. Volunteering can thus be an arena for the reinforcement and conversion of different forms of capital.

Recruitment of volunteers to CSOs is also found to follow the law of homophily (McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001) in which “rational prospectors” select people with characteristics that are already overrepresented among existing volunteers in an organisation (Brady et al. Reference Brady, Schlozman and Verba1999). This relates to another central concept from Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1977), namely habitus, which refers to internalised structures or “schemes of perception” common to members of the same group or class, similar in capital volume and composition. These schemes of perception are lasting, embodied, and subjective (but not individual) dispositions that regulate our way of conceiving, assessing, and acting in the social world (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1977, p. 86). The habitus concept has been introduced to volunteering research by Janoski et al. (Reference Janoski, Musick and Wilson1998), who viewed volunteering as a certain mode of conduct or set of routines and practices that become habituated (Janoski et al., Reference Janoski, Musick and Wilson1998). Jäger et al. (Reference Jäger, Höver, Schröer and Strauch2013) used the habitus concept to explore how motivations, career context, and individual biographies of non-profit executive directors influenced their careers in non-profit organisations. Also, Dean (Reference Dean2016) utilises the habitus concept to explore how volunteer recruiters, due to pressure to meet certain targets, recruit middle-class young people whose habitus is a better fit with the tasks in volunteering projects, unintentionally reinforcing a pattern of middle-class dominated volunteering in the United Kingdom.

The voluntary sector can itself be understood in a Bourdieusian perspective, as a social field in the larger social space where social action or—practice unfolds (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1998). Macmillan (Reference Macmillan2011) discussed how the voluntary sector, and the relations and practices in and around it, can be conceptualised as a contested field with its own codes, language, and understandings. In the volunteering field, individuals, groups, organisations, practices, and ideas are positioned in relation to each other, where some are in a better position than others (Macmillan, Reference Macmillan2013, p. 5; Emirbayer & Johnson Reference Emirbayer and Johnson2008). This sector can further be divided into specific fields with their own dynamics, rules, or structures (Meyer & Rameder, Reference Meyer and Rameder2021). Organisations in different fields may differ substantially regarding types of activities and purpose, degrees of professionalisation, size, and formalisation of organisation. Some organisations might resemble professional or business organisations while others are more like informal community groups. As a result, different types of organisations will have different requirements for the competence and skills of volunteers and will also provide different opportunities for capital conversion and spill-over effects to other social arenas (Meyer & Rameder, Reference Meyer and Rameder2021). Accordingly, different organisational fields will have their own field-specific logics of practice that determine which types or combinations of capital will provide benefits or symbolic capital. For example, Meyer and Rameder (Reference Meyer and Rameder2021) found that inequalities in occupational status are widely transferred to volunteering in the fields of sports and politics, while inequalities in educational status are more important within the fields of religion and social services. They also argue that the fields of sports and politics may convey symbolic capital more directly, providing leading volunteers with economic benefits (spill-over effect), while symbolic capital within religion and social services is more specific and less convertible into economic advantages.

Class-Based Volunteering in Norway?

Norway, along with the other Scandinavian countries, is generally seen as a more egalitarian society than many others. Norwegians themselves also conceive of Norway as a more egalitarian society than elsewhere, even compared to Sweden and Denmark (Hjellbrekke et al., Reference Hjellbrekke, Jarness, Korsnes, Coulangeon and Duval2015). Compared internationally, social inequalities in Norway are relatively low and social mobility is high. These traits are linked to the existence of an encompassing welfare state characterised by publicly funded and administered welfare programmes, comprehensive and universal coverage, egalitarian benefit structures, redistributive general taxes, programmatic emphases on work, and economic policies that stress full employment (Swank, Reference Swank, Geyer, Ingebritsen and Moses2000). Although social inequalities in Norway are small compared to many other countries, economic inequalities have risen over time (Geier & Grini, Reference Geier and Grini2018), driven more by wealth accumulation and inheritance in certain families (Hansen & Toft, Reference Hansen and Toft2021). The educational level of parents also seems to have a substantial influence on their children’s educational level (Salvanes, Reference Salvanes2017). Hence, economic, and educational inequalities are reproduced in younger generations.

Often placed within the social democratic model of civil society (Salamon & Anheier, Reference Salamon and Anheier1998), the Scandinavian countries are also characterised by a long history of egalitarian civic cultures with broad recruitment across class formations, including elites, lay groups, and ordinary citizens in civic engagement and organisations (Henriksen et al., Reference Henriksen, Strømsnes and Svedberg2019). Although the popular mass movements that laid grounds for the modern civil society in Scandinavia were mobilised along class lines, compared to other European countries, cross-class mobilisation was more extensive in Scandinavia. This has resulted in a civic culture in Scandinavia more egalitarian than elsewhere (Selle et al., Reference Selle, Strømsnes, Svedberg, Ibsen, Henriksen, Henriksen, Strømsnes and Svedberg2019). Furthermore, the Scandinavian countries, and Norway in particular, have been shown to exhibit unusually high and stable levels of civic engagement, memberships, and organising over the past 30 years. Between 50 and 60% of the Norwegian population volunteered for a CSO the preceding year, with sports, culture, and socialisation the dominant fields (Eimhjellen et al., Reference Eimhjellen, Steen-Johnsen, Folkestad, Ødegård, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018). Internationally, Norway is ranked on top with regard to share of population participating in volunteer work (Salamon et al., Reference Salamon and Sokolowski2004).

Despite these relatively egalitarian characteristics, volunteering in Scandinavia is also marked by social inequalities (Henriksen et al., Reference Henriksen, Strømsnes and Svedberg2019). In Norway, besides gender (more men), ethnicity (more Norwegian born), and age (more among the early middle-aged), there are higher levels of voluntary participation among the higher educated and those with higher incomes levels and larger social networks (Eimhjellen et al., Reference Eimhjellen, Steen-Johnsen, Folkestad, Ødegård, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018). However, the educational gap in volunteering seems to be shrinking, as people with primary education are becoming more likely to volunteer, and the effect of educational level on time spent volunteering seems to be decreasing (Qvist et al., Reference Qvist, Folkestad, Friberg, Lundåsen, Henriksen, Strømsnes and Svedberg2019). Still, volunteer recruitment is largely done through social networks and “weak ties” (Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1973), in which the law of homophily seems to apply, where men, the higher educated, and those with a sense of neighbourhood belonging are more likely to be asked to volunteer, sustaining patterns of inequality (Wollebæk et al., Reference Wollebæk, Sætrang and Fladmoe2015). As such, social positions by way of capital possession are likely to shape the patterns of volunteering in Norway, with a larger proportion of high-status groups doing volunteer work compared to low-status groups.

Regarding different organisational fields, we know that Norwegians with higher personal income are more likely to volunteer for sports organisations, and economic and housing organisations (Fladmoe et al., Reference Fladmoe, Sivesind and Arnesen2018). Norwegians with higher educational levels are also more likely to volunteer for social and welfare organisations, civic organisations, economic and housing organisations, and culture and leisure organisations (Fladmoe et al., Reference Fladmoe, Sivesind and Arnesen2018). This somewhat resonates with Meyer and Rameder’s (Reference Meyer and Rameder2021) findings on occupational status being more important for participation in sports (and politics) and educational status being more important for participation in social services (and religion). Hence, we may expect that volunteering for sports organisations and economic and housing organisations is situated in economically rich capital positions, while volunteers for social and welfare organisations, civic organisations, and culture and leisure organisations are situated in culturally rich capital positions.

Patterns of inequality may also be found concerning the types of tasks and activities in organisations. Although volunteer tasks may be structured less hierarchically, as argued for by Quinn and Tomczak (Reference Quinn and Tomczak2021), different tasks may demand different types of resources or skills, and facilitate different positions, levels of autonomy, and authority in organisations (Meyer & Rameder, Reference Meyer and Rameder2021; Musick & Wilson, Reference Musick and Wilson2008). Previous studies in Norway have not investigated this in detail, but an assumption could be made that administrative work and board memberships would demand certain competences related to higher education, while practical tasks such as community work or transport would be less dependent on such competences. The recruitment of volunteers to competence-dependent tasks may be particularly aimed at individuals with higher volumes of capital or specific types of capital compositions.

Data and Methods

The data used for the analyses come from on a web survey from 2019, administered by Kantar TNS (http://www.galluppanelet.no/) and distributed to a representative sample of Norwegians, with a response rate of 45%. From a base of 50,000 randomly recruited individuals,Footnote 2 a stratified sample of 11,469 individuals was drawn to represent the population in the composition of gender, age, education, and geography. A net sample of 5154 individuals responded to the survey. There is a minor gender skewness (51% women and 49% men) and geography skewness (fewer individuals from middle and northern Norway) in the sample compared to the population, and a larger skewness in age (fewer in the youngest age categories) and education (fewer in the lower education categories).

To measure volunteering practices, the respondents were asked if they had done volunteer work for organisations categorised by the UN International Classification of Non-profit Organizations—ICNPOFootnote 3 and what types of volunteer tasks they had performed. The other variables of interest are indicators for the three different forms of capital. To measure economic capital, I have a crude instrument that considers yearly household income before tax. Missing information on capital possession and fortune may provide a skewed representation of individuals’ economic capital, but income is still an indicator of individuals’ economic resources. Cultural capital is measured by several indicators: the level and area of personal education, the number of books in the household one was brought up in, and individuals’ positioning (agree/not agree) on several statements related to arts and culture: most of my friends are very interested in arts and culture; it is important that society applies resources to preserve classics within arts and culture; there is no good or bad art, only different tastes; the media should limit the coverage of sports and increase the coverage of art and culture. To measure social capital, the respondents were asked about the traits of their social network—how many friends they have—what types of resources they can get hold of through their social networks—help with money, help to get a job—and if they know someone in a high-status position.Footnote 4 These capital measurements will capture central, albeit not all, aspects of the concept.

Analysis Technique

Different from most research on volunteering, I utilise multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) with the aim of identifying groups of individuals with similar profiles based on their responses on capital indicators, and subsequently see how volunteering indicators are structured according to these groups. This technique is applicable to a relational understanding of the social world where the object of research is to identify and model differences and similarities between individuals and their characteristics—a relational mode of object construction. MCA is a nonlinear method for identifying the structure of data (Blasius et al., Reference Blasius, Lebaron, Le Roux and Schmitz2020). Rather than fitting data to a linear model to explain a dependent variable over a series of independent variables, as in an ordinary regression, with MCA one tries to identify the relational structure of data by using a geometric modelling of social spaces and fields. “It is a technique which ‘thinks’ in terms of relation, as I try to do precisely with the notion of field” (Bourdieu & Wacquant Reference Bourdieu and Wacquant1992, p. 96). From such a geometric point of view, survey data, values, and variables may be conceptualised as clouds of points within a social space. The underlying geometric model provides a numerical output that can be interpreted similarly to principal component analysis.Footnote 5 Such a formally constructed map of the social space allows us to interpret nonlinear relations between forms of capital and forms of volunteering, supplementing previous volunteering research with an alternative method of analysis and graphical illustration of how volunteering practices are positioned in the social space.

Traditionally in a Bourdieu-inspired MCA (but not by rule), the social space is constructed by a vertical axis, representing the total volume of capital, and by a horizontal axis, representing the composition of capital (economic, cultural, and social). Like other research using MCA, I will display and interpret the results by investigating the MCA output in the form of maps of the social space, and the positioning and distances between positions of categories in these maps. This is supported by statistics output from the MCA included in Appendix. The positions of interest in the social space will be the positioning of organisational fields that individuals volunteer within and the types of tasks they perform for organisations. The MCA is performed using the Coheris Analytics SPAD software. Categories are shown as markings in the social space with their corresponding category name.

Descriptive Statistics

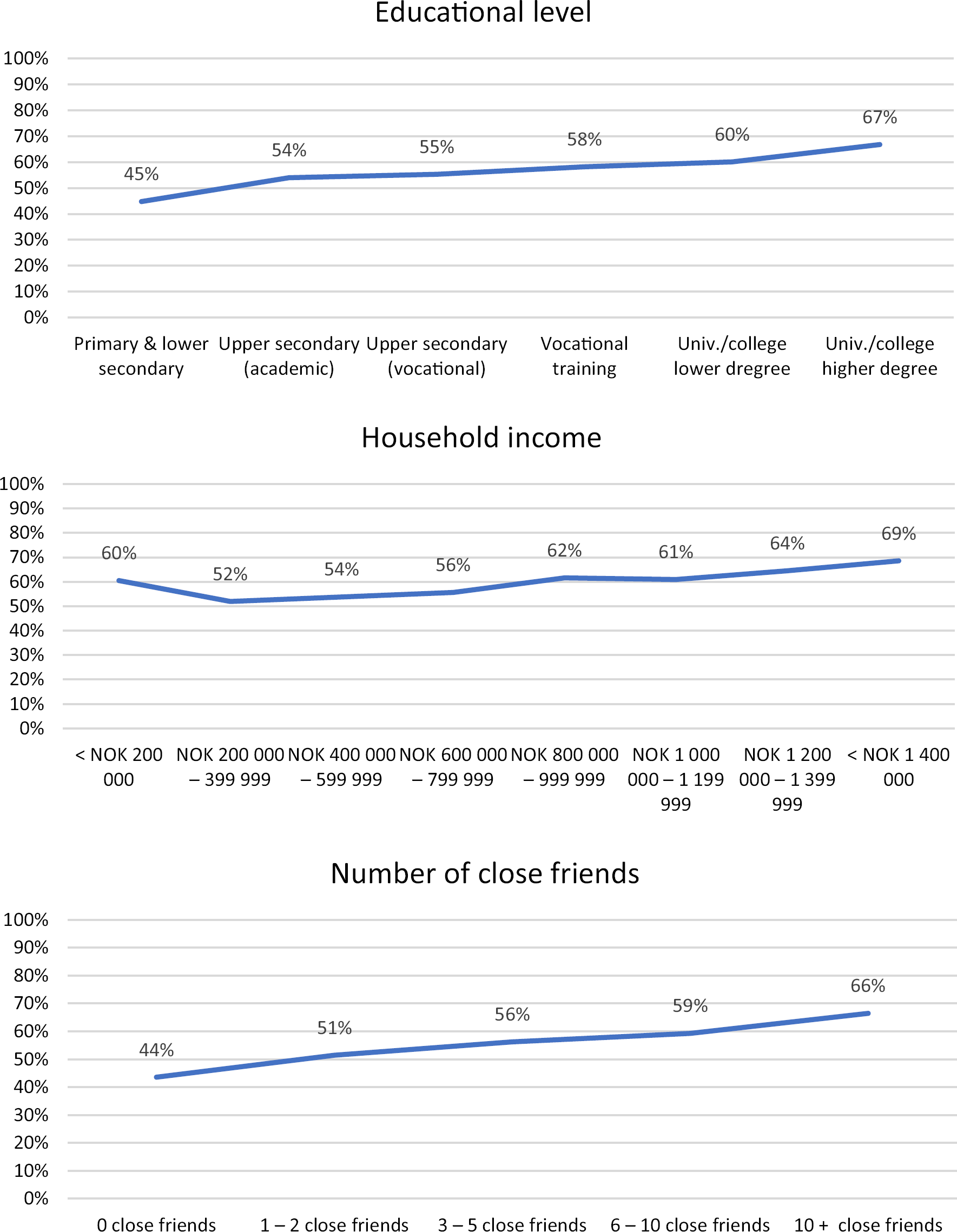

Before I start the construction of the social space, I will present descriptive statistics on the percentage share of volunteers by different values on key indicators of the three types of capital: educational level (cultural capital), yearly household income (economic capital), and number of friends (social capital). Supported by previous research, the Gallup data (Fig. 1) shows that the share of volunteers increases with higher levels of education: from 45% among respondents with primary or lower secondary education to 67% among those with a higher university or college degree. Similarly, the share of volunteers increases with higher income levels.Footnote 6 One exception to this pattern is the income category below NOK 200,000, with a share of 60% volunteers, which is a larger share than in the next income category. A further inspection of the income category below NOK 200,000 reveals that it is heavily populated by students, who are also prone to volunteer (Eimhjellen & Fladmoe, Reference Eimhjellen and Fladmoe2020). Regarding social capital, the share of volunteers is larger among respondents with more friends, rising from 44% among respondents with no close friends to 66% among respondents with more than 10 close friends. These descriptive statics are much in line with previous research on volunteering in Norway (Eimhjellen et al., Reference Eimhjellen, Steen-Johnsen, Folkestad, Ødegård, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018), supporting the claim that volunteering is more common among groups with higher levels of cultural, economic, and social capital. Still, in international comparison, the level of volunteering among the “capital poor” in Norway is higher than the general level of volunteering in many other countriesFootnote 7 [Fig. 1].

Fig. 1 Share of volunteers by educational level, household income, and number of friends, in the Gallup data

Constructing the Social Space

To construct the social space, I utilise the MCA technique in SPAD based on the set of capital indicators described in the methods and data section. All the capital indicators are included in the MCA as active variables in constructing the social space (12 variables/51 categories). The indicators for volunteering (n = 25) are subsequently projected as passive or supplementary variables into the constructed social space, allowing us to inspect how fields and practices of volunteering are structured and positioned by capital volume and composition in the Norwegian social space.

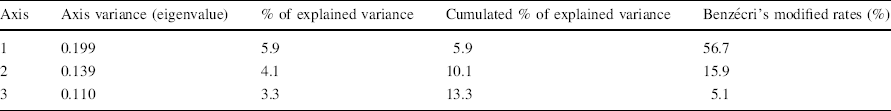

The MCA reveals several axes in the data. The first two axes contribute to a total of 72.6% of the variance in the data: axis 1 = 56.7% and axis 2 = 15.9% (Benzécri’s modified rate).Footnote 8 From axis 2 to axis 3 there is a marked reduction in variance contribution of 5.1%, which prompts me to concentrate the further analysis on the 1, 2 axes. This also resonates well with previous analyses of the main dimensions and structure of the Norwegian social space (Flemmen et al., Reference Flemmen, Jarness and Rosenlund2018; Jarness et al., Reference Jarness, Flemmen and Rosenlund2019).

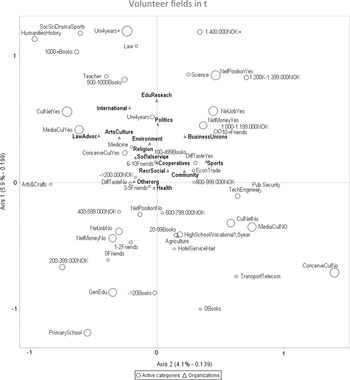

Axis 1 is interpreted as a total capital volume axis, contrasting high and low volumes of capital. Like Jarness et al. (Reference Jarness, Flemmen and Rosenlund2019), this analysis indicates that the volume of capital is much more important for explaining the structure of the Norwegian social space than capital composition. Each variable’s absolute contribution to axis 1 is illustrated by the size of the circle point in the social space. The variables contributing the most to the variance on axis 1 are educational level (20.9%), field of education (16.7%), and books in the household one grew up in (11.5%). In the social space (Fig. 2), we find indicators of low capital positioned in the area below the horizontal line: lower educational level; fewer books in the household one grew up in; negative attitudes towards highbrow culture; fewer friends; lower-income levels; and fields of education associated with shorter education and low-income levels. One exception is the lowest income category (< NOK 200,000) positioned in the top half of the social space. As previously mentioned, this category is populated by many students, a particular group with low income albeit larger volumes of cultural capital. Further up in the social space, indicators of large volumes of capital are positioned. From the top, we find indicators of higher-level education: many books in the household one grew up in; positive attitudes towards highbrow culture; more network resources; and higher levels of household income.

Fig. 2 The social space constructed by capital indicators. Multiple correspondence analysis. N = 5154

Axis 2, with a lower contribution to the total data variance, is interpreted as a capital composition axis, contrasting cultural capital (left side) with social and economic capital (right side). The variables contributing the most to the variance on axis 2 are attitude towards more arts and culture in the media (17.5%), having a network of friends interested in arts and culture (16.8%), and field of education (13.7%). On the top-left side of the social space, we find indicators of cultural capital: university education; many books in the household one grew up in; most friends interested in arts and culture; positive attitudes towards highbrow culture; and educational fields like humanities, social sciences and arts and crafts. On the top-right side of the social space, we find indicators of economic and social capital: high income categories; many friends; and access to resources through social networks. There are also diagonal oppositions in the social space from lower income levels, fewer friends, and no network resources in the bottom-left quadrant to higher income levels, more friends, and resource access through social networks in the top-right quadrant. Similarly, there is a diagonal opposition on attitudes towards arts and culture, with negative attitudes in the bottom-right quadrant and positive attitudes in the top-left quadrant (Fig. 2).

Volunteering Fields and Tasks in the Social Space

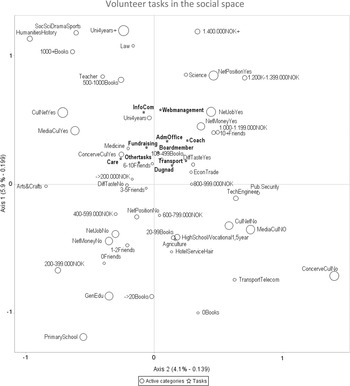

To inspect the positioning of different forms of volunteering, I first turn to the organisational fields that individuals have volunteered within, by projecting the fields into the social space. Test values for the organisational fields (see Appendix Table 1) indicate that their position is far enough from the barycentre to allow for a substantial interpretation of their position as influenced by the volume and composition of capital.Footnote 9 As we can see in Fig. 3, most organisational fields are positioned in the top half of the social space, indicating that volunteering in general is a phenomenon positioned from the middle and halfway up in Norwegian social space, in positions characterised by a medium volume of capital.

Fig. 3 Volunteer fields in the social space. Volunteering for types of organisations as supplemental categories. Multiple correspondence analysis. N = 5154

On the vertical dimension, volunteering for organisations within the field of education, training, and research is positioned highest up. Such types of organisations are concerned with issues related to all levels and types of education and training, from primary schools to universities, and may also have more formal and professional-like qualities. Recruitment of volunteers with higher education (cultural capital) may be particularly relevant for such organisations, following the law of homophily (McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001), with subsequent individual benefits and spill-over effects in the form of capital reinforcement and symbolic capital for the recruited volunteers. In the second and third highest position, we find volunteers in the field of international organisations like humanitarian aid organisations, peace organisations or international exchange, and political organisations. These fields that might also favour professional competence or higher-level education among volunteers, making it less attainable for individuals with less capital.

In the following positions, we find volunteers in the fields of law and advocacy, such as rights-based, support and substance abstention organisations; business organisations and unions; arts and culture; and environment and animal protection. We could perhaps have anticipated a higher position for business organisations and unions, as these are tightly related to paid work and business. However, its positioning could also be due to how this organisational category is constructed in the ICNPO scheme, lumping together labour and employers’ organisations, assuming two opposites regarding high and low volumes of (economic) capital. Separating these fields might have positioned them further apart, with unions being positioned below business organisations. The same argument can be made concerning the political field that encompasses all types of political organisations regardless of its position on the political spectrum. This may obfuscate differences regarding right- and left-wing politics and associated capital composition and volume.

Closer to the zero line on the vertical dimension, in the middle area of the social space, we find volunteers within the fields of religion; social services; cooperatives; and sports. Furthest down, we find volunteers in fields of recreation and social clubs; community; other organisations; and health. Among these fields are the biggest in Norway, representing the dominant leisure orientation: sports, community organisations, and recreation and social clubs. This indicates that the largest volunteering fields in Norway are less demanding on the capital possession of volunteers. Diverging somewhat from this picture is the positioning of the arts and culture field, a fourth representation of the leisure orientation in Norway, which seems more inclined to favour a certain volume of capital among its volunteers. Some fields, like health and community might also be fields where volunteering provides less benefits, reputation, and symbolic capital for the volunteers, as illustrated by Meyer and Rameder’s (Reference Meyer and Rameder2021) findings regarding social services in Austria.

Although contributing less to the data variance, capital composition also separates between organisational fields horizontally, with volunteers within law and advocacy, and arts and culture furthest to the left, favouring cultural capital over economic and social capital. Sports and business organisations and unions, however, are furthest to the right, favouring social and economic capital. It is interesting to note that the four leisure fields (arts and culture; recreation and social clubs; community organisations; sports) are positioned apart as regards typical capital compositions among their volunteers, which indicates a somewhat different capital requirement for the inclusion of volunteers in these fields in Norway (Fig. 3).

Moving on to the types of tasks performed in organisations (Fig. 4) we can see that some tasks particular for certain organisational fields, such as coaching within sports and care work within social services, are placed in similar positions compared to related organisations. Website management and communication are placed highest up, indicating demands for a certain level of competence and hence capital. Care tasks, community work (dugnad), and transport are placed closer to the zero line, indicating lower demands for capital. There is less horizontal dispersion of volunteer tasks regarding capital composition. Interestingly, having a position as a board member does not seem to require a particularly high volume of capital. This may be a result of the heterogeneity between CSOs and organisational fields, where organisations in certain fields, like business organisations, demand a high capital volume to enter a board, while others do not (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Volunteer tasks in the social space. Types of volunteer tasks as supplemental categories. Multiple correspondence analysis. N = 5154

Concluding Discussion

The analyses in this article have demonstrated a hierarchically structured social space in Norway according to total volume of capital (cultural capital and education in particular), in which fields and practices of volunteering are positioned from the centre to halfway up on the capital volume axis. Capital composition seems to provide less variance in volunteering practices. Although the social space reveals a large dispersion of capital positions, from high to low, no volunteering fields or practices are placed in positions characterised by very high or very low volumes of capital. In general, this indicates that the uptake of volunteers in Norwegian CSOs is relatively egalitarian with respect to capital possession, which resonates well with established notions of the Norwegian civil society model as social democratic and egalitarian.

There are, however, exceptions to this portrayal, with some volunteering fields (education and research; international; politics) having their own specific logics with a seemingly larger demand for capital, recruiting volunteers with a field-appropriate habitus and from a certain social position. Such field-specific logics and demands for competence may follow naturally from the type of activity and purpose of some organisations and may not pose a challenge for inequality in volunteering per se, providing such logics do not become the norm in larger volunteering fields or volunteering in general.

Furthermore, with the capital volume axis displaying a markedly hierarchical social structure in Norway, the analysis somewhat nuances the portrayal of Norwegian society as particularly egalitarian. Since this Bourdieusian approach provides structures of differences in Norway similar to that of Bourdieu’s original empirical context—France—with different societal features and a welfare model, it also supports Bourdieu’s contention that this analytical model reflects more general principles of differentiation across societies (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1991). As such, it would be of great interest to see if similar analyses performed in other countries with different welfare and civil society models would produce similar patterns of differentiation, and even more interestingly, demonstrate how volunteering fields and practices would be positioned in these social spaces.

A few limitations of this study need to be discussed. First, the measure of economic capital used in the analyses—household income—is an insufficient measure for economic capital, as it is not adjusted for household size, and it misses indicators of wealth like private property, fortune, and not least inheritance, which is the main driver of economic inequality in Norway (Hansen & Toft, Reference Hansen and Toft2021). Including such indicators could have changed the structure of the constructed social space and the positioning of volunteering fields and practices. Secondly, the ICNPO-classification scheme used in the survey often subsumes very different types of organisations under the same category, like business, professional organisations and unions, and political organisations. Such internal differences within categories can outweigh each other, misplacing the position of an organisational field. Another type of organisational classification would likely have changed the positions of volunteering fields in the social space. Similarly, the survey question on types of tasks performed in organisations, like board memberships, is not linked to the specific field or organisation respondents have volunteered for, obfuscating potential heterogeneity between organisational fields in organisations’ demands for a certain composition or volume of capital among volunteers regarding certain tasks.

To provide a new perspective and methodological approach to analyse social inequality in volunteering, I have used the MCA method on national survey data. MCA is a more inductive and descriptive statistical approach for analysing multivariate data, in contrast to standard multivariate regression modelling. Hence, MCA is less applicable for statistical hypothesis testing about population parameters based on data from samples of the population and for tracing the directionality in relations between variables. Still, what MCA provides is a new glance at volunteering survey data that uncovers patterns of inequality based on multiple characteristics and, not least, a numerically based graphical display of such patterns. I therefore argue that MCA provides a much-needed supplement to, but not a replacement of, standard statistical methods for investigating inequalities in volunteering.

Based on the theoretical discussion, empirical findings, and discussed limitations, and along with Hustinx et al. (Reference Hustinx, Grubb, Rameder and Shachar2022), I argue for a new volunteering research agenda that specifically investigates social differentiation in volunteering. Along with previous Bourdieu-inspired research investigating internal and field-specific logics of CSOs and their volunteers (Krause, Reference Krause2014, Reference Krause2018; Quinn, Reference Quinn2019), I specifically call for future volunteering research to apply a Bourdieusian perspective. Such an agenda would also imply the development of a more suitable system for classifying volunteering fields that better capture social inequalities and patterns of differentiation in volunteering (not specifically aimed at mapping the scope and volume as with the ICNPO scheme). A more suitable classification system for investigating inequality in volunteering should be better at capturing internal and field-specific logics of CSOs and their volunteers, modes of operation, tasks, and practices. Additionally, appropriate measures for economic as well as cultural and social capital should be included. Applying such a Bourdieusian perspective would provide a new vantage point for understanding and explaining social inequality and differentiation within volunteering in different societal contexts. Considering the growing social, cultural, and economic differences in many societies today, to further such a research agenda would be of great importance.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the reviewers and colleagues in NORCE Social Sciences and at the department of Media and Information Sciences at the University of Bergen, for valuable comments and input on earlier drafts of this article. I would like to thank Jan Fredrik Hovden at the department of Media and Information Sciences (UoB) for advice on the methods and analyses. I would also like to thank director Bernard Enjolras and The Centre for research on civil society and voluntary sector in Norway for facilitating this publication.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by NORCE Norwegian Research Centre AS.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendix

Table 1 Test values. Active and supplementary categories

Variables |

Label |

Weight |

Distance to origin |

Axis 1 |

Axis 2 |

Axis 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Active |

||||||

Houseincome |

− > 200.000NOK |

161.000 |

5.569 |

0.539 |

− 2.211 |

14.042 |

200–399.000NOK |

532.000 |

2.948 |

− 16.250 |

− 18.254 |

6.137 |

|

400–599.000NOK |

992.000 |

2.048 |

− 8.059 |

− 10.515 |

− 2.913 |

|

600–799.000NOK |

896.000 |

2.180 |

− 7.938 |

1.340 |

− 12.730 |

|

800–999.000NOK |

774.000 |

2.379 |

0.061 |

8.771 |

− 3.992 |

|

1.000–1.199.000NOK |

545.000 |

2.908 |

10.009 |

12.135 |

− 0.795 |

|

1.200 K–1.399.000NOK |

319.000 |

3.893 |

15.266 |

12.937 |

8.398 |

|

1.400.000 NOK + |

278.000 |

4.188 |

20.373 |

5.759 |

8.441 |

|

*Missing*(supplementary) |

657.000 |

2.616 |

− 1.033 |

− 5.119 |

− 1.791 |

|

Edu |

PrimarySchool |

429.000 |

3.319 |

− 25.621 |

− 11.939 |

19.715 |

HighSchool/Vocational1.5 year |

2712.000 |

0.949 |

− 30.885 |

13.530 |

− 28.443 |

|

Uni4years |

1165.000 |

1.850 |

20.048 |

− 1.511 |

− 5.473 |

|

Uni4years + |

848.000 |

2.253 |

38.065 |

− 7.622 |

29.790 |

|

EduField |

Agriculture |

101.000 |

7.073 |

− 4.350 |

1.639 |

− 6.352 |

Arts&Crafts |

132.000 |

6.168 |

− 0.170 |

− 9.802 |

− 5.237 |

|

EconTrade |

733.000 |

2.456 |

2.780 |

8.357 |

− 14.837 |

|

GenEdu |

1059.000 |

1.966 |

− 31.666 |

− 12.810 |

5.347 |

|

HotelServiceHair |

124.000 |

6.369 |

− 5.893 |

1.513 |

− 11.521 |

|

HumanitiesHistory |

215.000 |

4.793 |

16.944 |

− 14.481 |

19.294 |

|

Law |

86.000 |

7.677 |

10.065 |

− 1.542 |

9.606 |

|

Medicine |

605.000 |

2.742 |

7.320 |

− 5.317 |

− 9.940 |

|

Pub.Security |

110.000 |

6.772 |

− 0.714 |

8.561 |

− 5.469 |

|

Science |

238.000 |

4.545 |

13.468 |

3.881 |

22.802 |

|

SocSciDramaSports |

215.000 |

4.793 |

17.632 |

− 9.094 |

10.711 |

|

Teacher |

312.000 |

3.939 |

15.269 |

− 7.311 |

2.044 |

|

TechEngineer |

987.000 |

2.055 |

− 3.759 |

22.120 |

− 8.898 |

|

TransportTelecom |

138.000 |

6.029 |

− 8.804 |

7.428 |

7.148 |

|

*Missing*(supplementary) |

99.000 |

7.146 |

− 4.857 |

− 1.765 |

2.402 |

|

Books |

0Books |

29.000 |

13.294 |

− 5.387 |

1.834 |

6.355 |

− > 20 Books |

436.000 |

3.290 |

− 19.017 |

− 0.444 |

8.642 |

|

20–99 Books |

1582.000 |

1.503 |

− 19.759 |

7.074 |

− 10.827 |

|

100–499 Books |

1877.000 |

1.321 |

10.711 |

3.087 |

− 10.947 |

|

500–1000 Books |

700.000 |

2.522 |

23.134 |

− 7.352 |

13.684 |

|

1000 + Books |

236.000 |

4.565 |

16.215 |

− 9.992 |

11.771 |

|

*Missing*(supplementary) |

294.000 |

4.066 |

− 7.161 |

− 0.667 |

1.005 |

|

CulNnet |

CulNetNo |

2073.000 |

1.219 |

− 18.851 |

34.154 |

15.113 |

CulNetYes |

1483.000 |

1.573 |

25.484 |

− 32.465 |

− 14.393 |

|

*Missing*(supplementary) |

1598.000 |

1.492 |

− 4.959 |

− 4.432 |

− 1.935 |

|

ConcerveCul |

ConcerveCulNo |

441.000 |

3.269 |

− 15.576 |

30.726 |

20.375 |

ConcerveCulYes |

3512.000 |

0.684 |

24.458 |

− 26.762 |

− 14.908 |

|

*Missing*(supplementary) |

1201.000 |

1.814 |

− 16.650 |

9.165 |

2.949 |

|

ArtTaste |

DiffTasteNo |

2527.000 |

1.020 |

− 0.415 |

− 14.882 |

− 27.347 |

DiffTasteYes |

1540.000 |

1.532 |

7.262 |

14.133 |

26.083 |

|

*Missing*(supplementary) |

1087.000 |

1.934 |

− 7.639 |

2.379 |

4.246 |

|

MediaCul |

MediaCulNO |

1471.000 |

1.582 |

− 15.921 |

33.887 |

12.271 |

MediaCulYes |

1805.000 |

1.362 |

21.984 |

− 32.525 |

− 6.790 |

|

*Missing*(supplementary) |

1878.000 |

1.321 |

− 6.851 |

0.440 |

− 4.784 |

|

Friends |

0Friends |

118.000 |

6.533 |

− 6.718 |

− 4.273 |

6.541 |

1–2Friends |

688.000 |

2.548 |

− 13.308 |

− 5.918 |

20.532 |

|

3–5Friends |

2095.000 |

1.208 |

− 1.759 |

− 3.702 |

− 0.925 |

|

6–10Friends |

1351.000 |

1.678 |

6.870 |

− 0.657 |

− 8.487 |

|

10 + Friends |

756.000 |

2.412 |

11.970 |

13.724 |

− 11.514 |

|

*Missing*(supplementary) |

146.000 |

5.857 |

− 5.193 |

− 0.579 |

1.803 |

|

Netw_job |

NetJobNo |

3062.000 |

0.827 |

− 33.442 |

− 26.212 |

6.153 |

NetJobYes |

2092.000 |

1.210 |

33.442 |

26.212 |

− 6.153 |

|

Netw_money |

NetMoneyNo |

2613.000 |

0.986 |

− 31.965 |

− 25.674 |

9.961 |

NetMoneyYes |

2541.000 |

1.014 |

31.965 |

25.674 |

− 9.961 |

|

Netw_position |

NetPositionNo |

3973.000 |

0.545 |

− 33.149 |

− 17.988 |

8.999 |

NetPositionYes |

1181.000 |

1.834 |

33.149 |

17.988 |

− 8.999 |

|

Supplementary |

||||||

Organisations |

No |

4674.000 |

0.320 |

− 8.126 |

6.865 |

2.219 |

ArtsCulture |

480.000 |

3.120 |

8.126 |

− 6.865 |

− 2.219 |

|

No |

4243.000 |

0.463 |

− 5.522 |

− 12.841 |

− 1.673 |

|

Sports |

911.000 |

2.158 |

5.522 |

12.841 |

1.673 |

|

No |

4603.000 |

0.346 |

− 2.313 |

− 2.083 |

1.589 |

|

RecrSocial |

551.000 |

2.890 |

2.313 |

2.083 |

− 1.589 |

|

No |

4898.000 |

0.229 |

− 10.595 |

0.044 |

− 3.209 |

|

EduReseach |

256.000 |

4.374 |

10.595 |

− 0.044 |

3.209 |

|

No |

4977.000 |

0.189 |

0.570 |

0.329 |

1.058 |

|

Health |

177.000 |

5.303 |

− 0.570 |

− 0.329 |

− 1.058 |

|

No |

4847.000 |

0.252 |

− 3.508 |

3.116 |

1.453 |

|

Socialservice |

307.000 |

3.973 |

3.508 |

− 3.116 |

− 1.453 |

|

No |

5001.000 |

0.175 |

− 3.854 |

0.751 |

− 1.175 |

|

Environment |

153.000 |

5.717 |

3.854 |

− 0.751 |

1.175 |

|

No |

4669.000 |

0.322 |

− 2.001 |

− 4.930 |

5.277 |

|

Community |

485.000 |

3.103 |

2.001 |

4.930 |

− 5.277 |

|

No |

4656.000 |

0.327 |

− 3.656 |

0.025 |

0.335 |

|

Cooperatives |

498.000 |

3.058 |

3.656 |

− 0.025 |

− 0.335 |

|

No |

5061.000 |

0.136 |

− 3.587 |

4.486 |

− 1.682 |

|

LawAdvoc |

93.000 |

7.377 |

3.587 |

− 4.486 |

1.682 |

|

No |

4938.000 |

0.209 |

− 6.889 |

− 0.061 |

2.684 |

|

Politics |

216.000 |

4.781 |

6.889 |

0.061 |

− 2.684 |

|

No |

5054.000 |

0.141 |

− 5.933 |

2.189 |

− 1.568 |

|

International |

100.000 |

7.109 |

5.933 |

− 2.189 |

1.568 |

|

No |

4919.000 |

0.219 |

− 5.681 |

− 3.442 |

0.957 |

|

BusinessUnions |

235.000 |

4.575 |

5.681 |

3.442 |

− 0.957 |

|

No |

4845.000 |

0.253 |

− 4.037 |

1.670 |

2.183 |

|

Religion |

309.000 |

3.960 |

4.037 |

− 1.670 |

− 2.183 |

|

No |

5024.000 |

0.161 |

− 0.087 |

2.109 |

1.387 |

|

Otherorg |

130.000 |

6.217 |

0.087 |

− 2.109 |

− 1.387 |

|

Tasks |

No |

4024.000 |

0.530 |

− 9.377 |

− 1.194 |

2.200 |

Boardmember |

1130.000 |

1.887 |

9.377 |

1.194 |

− 2.200 |

|

No |

4237.000 |

0.465 |

− 11.254 |

− 3.306 |

2.359 |

|

AdmOffice |

917.000 |

2.150 |

11.254 |

3.306 |

− 2.359 |

|

No |

4789.000 |

0.276 |

− 3.645 |

− 4.875 |

1.993 |

|

Transport |

365.000 |

3.622 |

3.645 |

4.875 |

− 1.993 |

|

No |

4735.000 |

0.297 |

− 7.281 |

− 5.458 |

− 3.657 |

|

Coach |

419.000 |

3.362 |

7.281 |

5.458 |

3.657 |

|

No |

3602.000 |

0.656 |

− 6.977 |

− 6.495 |

3.026 |

|

Dugnad |

1552.000 |

1.523 |

6.977 |

6.495 |

− 3.026 |

|

No |

4756.000 |

0.289 |

− 5.996 |

1.273 |

1.873 |

|

Fundraising |

398.000 |

3.457 |

5.996 |

− 1.273 |

− 1.873 |

|

No |

4841.000 |

0.254 |

− 10.572 |

− 0.869 |

− 1.625 |

|

Webmanagement |

313.000 |

3.933 |

10.572 |

0.869 |

1.625 |

|

No |

4853.000 |

0.249 |

− 10.039 |

1.479 |

− 1.995 |

|

InfoCom |

301.000 |

4.015 |

10.039 |

− 1.479 |

1.995 |

|

No |

4756.000 |

0.289 |

− 4.150 |

5.405 |

2.101 |

|

Care |

398.000 |

3.457 |

4.150 |

− 5.405 |

− 2.101 |

|

No |

4698.000 |

0.312 |

− 3.817 |

2.667 |

0.390 |

|

Othertasks |

456.000 |

3.210 |

3.817 |

− 2.667 |

− 0.390 |

|

Table 2 Test parameters for the two first axes in the MCA. Cloud variance (matrix trace): 0.817

Axis |

Axis variance (eigenvalue) |

% of explained variance |

Cumulated % of explained variance |

Benzécri's modified rates (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

0.199 |

5.9 |

5.9 |

56.7 |

2 |

0.139 |

4.1 |

10.1 |

15.9 |

3 |

0.110 |

3.3 |

13.3 |

5.1 |