‘We were taken, agianst our will to foreign territories, as Mauritius and the Seychelles were to Chagossians. We were uncermoniously dumped into abject poverty. We were made to live in what would be considered “garden sheds” in the U.K. There was no infrastructure, no utilities and no viable means of even simple subsistance. Treated as unwelcome outsiders and interlopers in these foreign territories, we miraculously persevered …

Yet, we never, never gave way to hate.

For half a century Chagossians maintained faith that, eventually,

we will be treated equally as human beings.

We believe that justice will prevail.

We believe that we will return home.

We have protested for 50 years in that belief.

We will never give up. Ever!’Footnote 1

Introduction

From 1968 to 1973, Britain forcibly displaced between 1500 and 2000 Chagossians from their homes on the Chagos Archipelago in order to build the US-UK Diego Garcia military base. At the time, and to the present, the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) claimed that the Chagossians were a mobile population of contract workers who were residing temporarily on the islands. This narrative effaces both the Chagossians’ multi-generational inhabitation of the islands, and the imperial histories of slavery and indenture which led to their presence on the archipelago. By portraying the islanders as mobile or ‘errant’ (commonly defined as ‘behaving wrongly in some way, especially by leaving home’,Footnote 2 ‘going outside the proper area’,Footnote 3 ‘straying outside the proper path or bounds’, or ‘moving about aimlessly or irregularly’Footnote 4) as a means to legitimise their displacement, this narrative undermines the rights and political belonging of contract workers, migrants, diasporas, and others perceived as mobile more broadly. The above account by Olivier Bancoult, Chair of the Chagos Refugees Group, complicates this narrative. The statement, which was given as written evidence to the UK Parliament Foreign Affairs Sub-Committee on the Overseas Territories in 2024, highlights the injustice of the displacement of the Chagossians, and the ongoing Chagossian resistance to their exile.

Located in the middle of the Indian Ocean, the Chagos Archipelago is now the site of the US-UK Diego Garcia military base. In a secret agreement made shortly before Mauritian independence in 1968, US and UK officials agreed to set up a military facility on Diego Garcia, the largest island on the archipelago, which FCO officials at the time stated, ‘you may say … will in no way constitute a base’.Footnote 5 To this end, in 1965, the UK excised the Chagos Archipelago from the British colony of Mauritius, and created the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT).Footnote 6 The agreement depended on the depopulation of the entire archipelago. As British diplomat Dennis Greenhill lamented: ‘along with the Birds go some few Tarzans or Men Fridays whose origins are obscure, and who are being hopefully wished on to Mauritius etc’.Footnote 7 The Americans wanted the islands ‘swept’ and ‘sanitised’,Footnote 8 and the Chagos Islanders posed a problem, which the FCO wanted to resolve as discreetly as possible. From the FCO’s perspective: ‘The object of the exercise was to get some rocks which will remain ours; there will be no indigenous population except seagulls’.Footnote 9 In an attempt to create this reality, the ‘sanitisation’ of the islands also meant killing the Chagossians’ pet dogs. The order to kill the dogs was issued by Sir Bruce Greatbatch, then Governor of the Seychelles,Footnote 10 and carried out by Marcel Moulinie, the copra company manager.Footnote 11 Accordingly, ‘they put all the dogs into a gas chamber until they died’.Footnote 12 Almost 1000 pet dogs were gassed in a sealed copra-drying shed by British actors and US troops, using exhaust from American military vehicles, and then burnt, in front of the remaining Chagossians who were awaiting deportation.Footnote 13 By 1973, the islanders had all been displaced. Almost 50 years later, 81-year-old Chagossian Rosemond Samynaden told reporters ‘[w]e’re like birds flying over the ocean, and we have nowhere to land. We must keep flying until we die’.Footnote 14 The islands were left with no indigenous population except the gulls, the dogs were killed, and the islanders, like birds, were flown away.Footnote 15

With attentiveness to the dynamics of imperial mobilities, errantry, and the displacement of the Chagos Islanders, the paper focuses on how the justification and contestation of the islanders’ displacement relate to claims about their status as ‘belongers’Footnote 16 on the island, linked to representations of the islanders as mobile or sedentary. Attempts by the FCO to legitimise the displacement hinge on the politicisation of mobility by representing the islanders as an itinerant population of contract workers from Mauritius and the Seychelles. This also implies the erasure of the ‘Ilois’ (or Chagossian) identity categories. In the words of Olivier Bancoult:

‘To circumvent any legal constraints, the British Government created and maintained the fiction that there was no population. Despite the evidence of multi-generational existance, Chagossians were deemed “contract workers” that had no right to be there. The disingenuous narrative told to the world is that our “labor contracts” were being terminated and they were all being “relocated.” “Relocation” ceratinly sounds better than “being forcibly exiled against their will”’. Footnote 17

The FCO strategy of representing the islanders as a mobile population of contract workers as a means to deny their political rights is consistent with broader hostility towards those perceived as ‘errant’, ‘mobile’ or ‘out of bounds’ within an international order. Outside of the specific case of the Chagossians, this logic has wide-reaching implications for other apparently mobile people, including migrants, contract workers, Roma and other travellers, nomads, diasporas, minorities, and descendants of enslaved people, indentured labourers, and other displaced people, rendering them ‘errant’ (or out of place) and therefore potentially displaceable.

In contrast to FCO representations of the islanders as a mobile population of contract labourers, some Chagossians (as well as human rights actors and academics) make a legal claim to Chagossian indigenous status based on long-held ties with the islands, and a discrete Chagossian identity.Footnote 18 For example, Chagossian Voices states that ‘Chagossian Voices have asserted the indigenous rights of Chagossians at the United Nations by registering as an indigenous group and by attending both the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) at the UN in New York and the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP) at the UN in Geneva – both in 2023’.Footnote 19 This is echoed by Human Rights Watch who state that ‘[t]he Chagossians are a distinct Indigenous people under UN and African standards, including those set out by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’.Footnote 20 The displacement of the Chagossians, many of whom are descendants of enslaved and indentured labourers whose presence on the archipelago is a result of enforced imperial mobilities, is being contested through a legal framework that emphasises sedentarism and bounded identity as the basis of political belonging. While this framework rightly affirms the Chagossian right to return to the Archipelago, and the specificity of Chagossian identity, it also points to the lack of legal or conceptual frameworks that can make political claims based on histories of mobility and fluidity. It also potentially stretches the concept of ‘indigeneity’ to disturb links between ‘indigeneity’ and autochthony (or originating in a place). This may have implications for other descendants of mobile or displaced people, although it is unclear how far this would transpose to other contexts.

The paper advances three related arguments. First, that attempts to both legitimise and contest the displacement of the Chagossians are articulated through representations of the Chagossians as a mobile or settled people, and as a discrete indigenous group, or a ‘floating population’ of contract labourers from Mauritius and the Seychelles. This binary emphasises nativity and sedentarism as the assumed norm of political belonging, effectively ‘sinking “peoples” and “cultures’’ into “national soils’,Footnote 21 with implications for access to land and resources. The terms of these debates limit recognition of forms of belonging based on mobility, fluidity, or displacement. Second, by focusing on the question of whether the Chagossians are ‘mobile’ or ‘sedentary’, these debates risk obscuring the mobilities of the settlers, soldiers, and contract workers involved in historically running the archipelagos’ copra plantations, and currently running the military base. This effaces the history of slavery which led to the inhabitation of the islands. Moreover, it obscures the fact that US and UK nation-states are not the result of timeless national belonging, but are also produced through mobilities.

This leads to the paper’s third claim, that scholars of global politics need additional conceptual frameworks that can make sense of political relations and forms of belonging that are either mobile in the present, or ‘rooted’ in histories of mobility. This includes an attentiveness to imperial mobilities and the political pitfalls of mobile political relations. However, it also proposes alternative conceptualisations of mobile forms of rootedness. Drawing on broader explorations of ‘roots’ and ‘routes’,Footnote 22 I suggest that Édouard Glissant’s concept of ‘errantry’ – understood as a mobile form of ‘rootedness’ which includes a recognition of RelationFootnote 23 – can act as an entry point into conceptualising these alternative conceptual frameworks. The necessity of multiplying conceptual frameworks and advancing concepts such as ‘errantry’ that articulate mobile forms of political belonging is evidenced by increasingly politicised contemporary debates over migration and diaspora.Footnote 24 These debates point to the constraints of articulating political belonging in relation to original homelands (as per anti-migrant politics, or ethnonationalist and Zionist articulations of diaspora), and the urgent need for additional political vocabularies that do not define legitimacy and belonging by sedentarism. At the same time, the paper recognises the multiplicity and contextual specificities of political ontologies, and the conclusion explores tensions and pitfalls of mobile political relations, as well as complementarities between errantry, geographical connectedness, and meaningful relations with land.

In the following sections, I first give an account of the histories of imperial mobilities that led to the inhabitation of the Chagos Archipelago, as well as the displacement of the Chagossians and its legal contestation. I then outline the papers’ approach to archival materials and the politics of knowledge, and its engagement with the concept of indigeneity. Locating the paper in postcolonial debates on ‘migrants’ and ‘natives’, I unpack the argument that the problematisation of the Chagossians as ‘mobile’ makes them appear ‘out of place’ within an international geographic imaginary that treats rootedness as the norm. I address the stakes of this for other descendants of enslaved people and indentured labourers. By proposing to think with Glissant’s concept of ‘errantry’ I explore articulations of additional forms of political ‘rootedness’ that unfold in movement which can challenge the binary distinction between ‘migrants’ and ‘natives’. Based on this framework, the article then analyses the centrality of FCO representations of the Chagossians as mobile to their displacement, as well as FCO attempts to erase the ‘Ilois’ identity category. Finally, I address the problematisation of the ‘permanence’ of the Chagossians and their status as a discrete indigenous population to the legal contestation of their displacement. In conclusion, I draw out the potential and tensions of errantry as an entry point into conceptualising mobile forms of political belonging, and geographic connectedness.

To conduct this analysis, I focus on British state archives, and draw on primary archival documents as well as secondary analysis of UK government documents, communications, and legal documents relating to the islands and the ongoing legal cases.Footnote 25 This analysis is focused on one FCO file (FCO 37/388) of approximately 150 pages which documents internal and some external communications from 1969, as well as an additional FCO map of the archipelago from 1981 (FCO 18/366), and analysis of current UK government communications and parliamentary reports. I chose to focus on FCO file 37/388 because it is composed of documents relating to the period when the displacement and relocation of the islanders was being carried out. It represents a moment where the official narrative was being constructed on an ad hoc and often somewhat candid basis in internal communications. I work with a critical approach to archives which treats ‘archives not as sites of knowledge retrieval but of knowledge production’, including through elisions and erasures.Footnote 26 Based on this, I read these materials with attentiveness to knowledge production, and the question of how categories are produced, contested, and erased in the archive.Footnote 27

Imperial mobilities and the displacement of the Chagossians

The history of the Chagos Archipelago is a microcosm of the constitutive role of mobilities in making apparently sedentarist international politics. These mobilities characterise imperial and anti-imperial circulation in the Indian Ocean World and more broadly, including the enforced mobilities of enslaved and indentured labourers, as well as settlers, soldiers, imperial intermediaries, missionaries, pilgrims, tourists, pirates, and merchants.Footnote 28 Indeed, as argued by Cooper, Stoler, and other scholars of empire, imperialism and anti-imperialism depend on the circulation of these and many other actors to build, maintain, and resist empires.Footnote 29 These mobile actors can be understood as ‘imperial diasporas’ that include colonised populations, labourers, merchants, and bureaucratic elites.Footnote 30 In the Indian Ocean World, histories of circulation long preceded European imperial expansion.Footnote 31 Nevertheless, by the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Chagos Archipelago was a site of competition between French and British Empires as both attempted to expand into already global and cosmopolitan Indian Ocean World networks. The islands were uninhabited until their settlement by French settlers and enslaved Africans to establish a copra plantation in 1785, producing oil from coconut shells,Footnote 32 leading the islands to be known as the ‘oil islands’.Footnote 33 In 1814, sovereignty over Mauritius and the Chagos Islands was ceded from France to Britain. In 1834, when slavery was abolished in the Indian Ocean, Mauritius (then part of the British Empire) acted as a test site for the transition from slavery to indenture.Footnote 34 On Chagos, the existing population of formerly enslaved labourers was supplemented through the circulation of indentured labourers from India, although in relatively lower numbers than in Mauritius, and (in the 1960s), by contract labourers from Mauritius and the Seychelles.Footnote 35

The Indian Ocean remains geopolitically central in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.Footnote 36 The establishment of the Diego Garcia military base reflects the perceived geopolitical centrality of the Indian Ocean to US and UK states. The geography of the archipelago, and specifically Diego Garcia, is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, while Figure 3 shows an 1981 FCO map locating the islands in relation to Mombasa, Aden, and other strategic points, reflecting the geopolitically strategic location of Diego Garcia. The Diego Garcia base played a key role in the 2001 US invasion of Afghanistan, and the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and has also attracted controversy due to its role in US renditions of terrorist suspects, and UK complicity in knowingly denying this.Footnote 37 Since 2022, Diego Garcia has also been the site of the illegal detention of Tamil refugees.Footnote 38 Both the detention of Tamil refugees and the role of the islands in the rendition of terrorist suspects are possible in part due to the legal grey areas afforded by the archipelago’s status as a British Overseas Territory. In addition, China has recently built a naval base in Djibouti, France has a military base on Reunion, and India is allegedly building a military base on Agalega, in partnership with Mauritius.Footnote 39

Figure 1. Map of the Chagos Archipelago/ British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT).

Figure 2. Map of Diego Garcia.

Figure 3. FCO Map of the Indian Ocean.

Since the displacement of the Chagossians, the islands have been the subject of ongoing legal debates in British, European, and international law.Footnote 40 These debates roughly span: i) the excision of the archipelago from Mauritius, and British and Mauritian claims to sovereignty over the islands; ii) the islanders’ right to return (or right to abode) on the islands, and iii) the legality of the establishment of a ‘Marine Protected Area’ (MPA) extending 250,000 square miles around the BIOT by the British in 2009 – arguably to further prevent resettlement.Footnote 41 In 2019, an International Court of Justice (ICJ) advisory opinion deemed the detachment of the Chagos Archipelago from the colony of Mauritius to be unlawful and stated that ‘the process of decolonization of Mauritius was not lawfully completed when that country acceded to independence’ and ‘the United Kingdom is under an obligation to bring to an end its administration of the Chagos Archipelago as rapidly as possible’.Footnote 42

In October 2024, the UK government agreed to cede sovereignty over the islands to the Mauritian state, and negotiations over the terms of this agreement are ongoing at the time of writing. The transfer of sovereignty to Mauritius does not resolve the question of Chagossian resettlement, or the presence of the US military facility on Diego Garcia. Controversially, the current agreement (which may or may not be accepted by the newly elected Mauritian government) includes a 99-year lease for the US-UK military base.Footnote 43 This will prevent the islanders from returning to Diego Garcia, although it remains unclear whether they will be able to resettle the outer islands,Footnote 44 and has been criticised by some Chagossians.Footnote 45 For example, in a 2024 letter to the UK Foreign Secretary, grass-roots organisation Chagossian Voices note that they ‘have never been properly consulted by the UK Government on any aspect of their future or the future of their homeland’ and were not included in or consulted in the negotiations.Footnote 46 Current statements build on long-standing critiques of the lack of commitment from Mauritian officials to resettle the islanders, which have led commentators to distinguish between Mauritian state and Chagossian interests, with the Mauritian state having an interest in maintaining the military base and claiming the displaced Chagossians as a Mauritian ‘minority’ population, which is at odds with the Chagossians’ interest in returning to the islands and their status as an ‘indigenous’ population.Footnote 47 The ongoing displacement of the Chagossians despite the formal ‘decolonisation’ of the islands points to the limitations of academic and ICJ calls to ‘decolonise’ the islands which involve retaining the US military base.Footnote 48

Legality, indigeneity, archives

The paper starts from the basis that the forced displacement of the Chagossians is illegal within international law.Footnote 49 In contrast to much existing academic work on the Chagossians, I do not focus on the legal justifiability of the displacement.Footnote 50 Instead, I focus on the political stakes of attempts to legitimise and contest the displacement, and the broader understandings of political belonging and access to land which they produce. These understandings of belonging are articulated in relation to international legal frameworks, but they are not defined by them. The limits of legality in accounting for the political possibility of displacing the Chagossians is illustrated by the fact that since 2000 the UK government has recognised the displacement to be unlawful, but this has not led to the practical resettlement of the islanders.Footnote 51 In 2019, the ICJ advised that the detachment of the archipelago from Mauritius was also unlawful. Following a vote in which UN representatives voted 116 in favour to six against ‘that the United Kingdom unconditionally withdraw its colonial administration from the area within six months’ the UK representative responded that: ‘While such opinions can carry weight in international law, they are not legally binding’,Footnote 52 pointing to the distance between legal technicality and political possibility. It is also important to note that FCO attempts to represent the islanders as a ‘floating population’ of ‘contract workers’ were found to be false, and were unsuccessful in avoiding political controversy. However, the question at stake is not only whether the islanders were ‘contract workers’, and whether or not they had inhabited the islands for multiple generations, but also the broader question of whether contract workers could make any claim to political belonging. In other words, if the islanders had been contract workers from Mauritius and the Seychelles, who had not been born on the islands, and who had moved every few years, would it have been politically possible to dispute their displacement? The FCO strategy suggests that whatever the legal technicalities, there was a belief that a ‘floating population’ of ‘contract workers’ would have no political traction to dispute their removal.

Instead of focusing on legal justifiability, I focus on the politics of knowledge production and categorisation in imperial archives. As Mahmood Mamdani argues, colonial categories did not historically ‘reflect’ identity positions, but ‘defined and ruled’, by classifying ‘natives’ into tribal and ethnic groups, linked to rights and homelands.Footnote 53 I primarily focus on official British state archives and formal legal representations, rather than other genres of knowledge production of Chagossian self-representation. This is partly because of the historical power relations which mean that the FCO archive is a primary source of written information about the displacement of the islanders in the 1960s and 1970s. However, it is also a research choice to focus on state knowledge production and legal systems of governance. Equally, it is important to note that Chagossians are actively involved in the ongoing legal cases and advocacy, led by Olivier Bancoult and the Chagos Refugees Group, meaning that there is no clear separation between legal representations and Chagossian self-representations.Footnote 54 Equally, while most scholarship on the Chagos Islands is not written by Chagossians, it is often written in conversation with Chagossian interviewees and collaborators, and Chagossian academics and filmmakers are publishing work on the Chagos Archipelago.Footnote 55 However, a valuable future area to expand this research will be to engage further with Chagossians’ understandings of belonging, mobility, and indigeneity through interview-based or ethnographic work, and engagement with alternative genres of knowledge production that exceed legalistic materials.

Because of the paper’s focus on the politics of categories, it is important to clarify the use of the terms ‘Ilois’, ‘Mauritian’, ‘Seychellois’, and ‘Chagossian’. In FCO official documents before the displacement of the islanders, the island’s inhabitants were categorised as ‘Ilois’, ‘Mauritian’, or ‘Seychelloise’.Footnote 56 The ‘Ilois’ category corresponded to people who were identified by the FCO primarily by their relation to the islands. This was related to, but not strictly defined by, being born on the islands. At displacement, the ‘Ilois’ category was erased from the FCO lexicon in an attempt to deny the existence of a Chagossian people with a relationship of belonging to the islands. During and following their displacement, the FCO represented the islanders as only ‘Mauritian’ or ‘Seychelloise’, effectively as belonging elsewhere and residing on the islands.Footnote 57 The ‘Ilois’ administrative category was a politicisation of identity which was then erased in an equally politicised manoeuvre. When I use the category of ‘Ilois’ this refers to how this category was used in FCO documents, which was intended by the FCO to contrast with the categories of ‘Mauritian’ and ‘Seychelloise’. In contrast, when I refer to ‘Chagossians’, ‘Chagos Islanders’, ‘islanders’, or ‘the islands’ inhabitants’ this is a looser framing that refers to all those who lived on the islands and their descendants, and/or identify themselves as ‘Chagossian’, including those identified at the time or now as ‘Mauritian’ or ‘Seychelloise’ in official documents.

The paper explores the politicisation of ‘indigeneity’ as a legal concept in the specific context of contemporary debates over the Chagos Islands, in relation to broader international legal frameworks. The concept of ‘indigeneity’ is a subject of ongoing academic debate, which has been critiqued by some academics for cultural essentialism, even if, with Spivak, it is considered a valuable form of ‘strategic essentialism’.Footnote 58 Drawing on existing scholarship in anthropology, I work from the basis that critiques of peoples’ self-identification as ‘indigenous’ are paternalistic.Footnote 59 As such, while I critically engage with the limitations of international legal framings of indigeneity, the paper does not critique the Chagos Islanders for their understanding of indigeneity either as a form of self-identification or as a legal strategy. Equally, the paper recognises the value and political stakes of work that draws on Indigenous thought and/or advances understandings of ‘Indigenous sovereignty’, above all in settler colonial contexts.Footnote 60 This research is often attentive to the risks of the essentialisation of ‘indigeneity’. The paper’s analysis of the Chagossians’ claim to indigeneity is therefore based on an understanding of the contingent meaning of ‘indigeneity’ across space and time, and focuses on the problematisation of indigeneity in international law. It recognises that debates over the Chagossians’ indigeneity are distinct from understandings of indigeneity in many other contexts, especially as Chagossian indigeneity is not based on first inhabitation. Indeed, the Chagossians’ claim to indigenous status stretches the concept of ‘indigeneity’ in ways that could rupture the links between ‘indigeneity’ and autochthony (or originating in a place), while continuing to define indigeneity by long-standing settlement, discrete cultural identity, and, crucially, by ongoing oppression/exclusion by dominant societal groups. While specific to the Chagossians, this potentially has implications for other people descended from enslaved and indentured labourers, although it is unclear how this understanding of indigeneity would transpose to other contexts, especially those with pre-colonial inhabitation.

Migrants, natives, errantry, and the international geographic imaginary

The problematisation of the Chagossians as a ‘mobile’ or ‘floating’ population of contract labourers makes them appear ‘out of place’ within an international geographic imaginary (or ‘taken-for granted spatial ordering of the world’Footnote 61) that treats rootedness as the norm, and is characterised by hostility towards those who are represented as mobile. International geographic imaginaries are characterised by an understanding of ‘states as “containers” of societies’,Footnote 62 the ‘discrete spatial partitionings of territory’ into national units, and a ‘sedentarist metaphysics’ which idealises the ‘rooting’ of peoples in place and pathologises ‘uprootedness’.Footnote 63 An international geographic imaginary is specific to international order, and linked to the ideal of national or ethnic homogeneity within a territory, in contrast to earlier imperial geographies within which multi-ethnicity was a norm.Footnote 64

Rather than marking the end of imperial order, the early twentieth century creation of international order rearranged imperial power relations in ways that are characterised both by continuity and radical discontinuity.Footnote 65 The division of empires into a sovereign state system, characterised by national sovereignty, but ‘subject to the regulatory regimes that operate within the system of states’,Footnote 66 was partially achieved through the global nationalisation of migration regulation. Indeed, the ‘nationalisation’ of border controls to regulate mobility in relation to national borders and national citizenship, was a primary mechanism by which the nation-state was constituted.Footnote 67 The nationalised regulation of migration codified race as a ‘national attribute’, and national immigration regimes discriminated on implicitly or explicitly racialised grounds,Footnote 68 for example, through anti-Asian immigration policies in the white settler colonies, and attempts to limit Jewish immigration within Europe.Footnote 69 These policies were not only restrictive, but also facilitated mobility and ‘encouraged entry, migration, naturalization, and settlement’, especially to produce the settler colonies as ‘white’.Footnote 70 As explored in existing literature, nationalised mobilities regulation continues to co-constitute shifting and contingent racialised identities and hierarchies in postcolonial international order.Footnote 71 While outside of the primary focus of this paper, the displacement of the Chagossians is coherent with these racialised hierarchies and regimes of deportability,Footnote 72 and is understood as such by some Chagossians. For example, Rosmon Saminaden states: ‘I’m going to explain to the judge that we were fine in Chagos, we lived well there, that’s we don’t know why – for what reason – they came and took us away to a country we didn’t know. But that this act of domination they subjected us to is because of our black skin’.Footnote 73

Debates over the Chagossians reflect the problematisation of subjects as ‘migrants’ and ‘natives’ which is key to the nationalised regulation of migration, but only loosely relates to actual mobility. As Nandita Sharma argues, a primary political distinction within international order is between the figures of ‘natives’ (or, ‘nationals’), as autochthons or ‘people of a place’, and ‘migrants’, as allochthons, or ‘people out of place’.Footnote 74 These figures are not defined by actual movement or the crossing of national borders, but by an imaginary of subjects as mobile or static. As Sharma emphasises: ‘Hostility to those who move – or who are imagined to have moved – is thus bred in the bone of the Postcolonial New World Order’.Footnote 75 The postcolonial hostility towards ‘migrants’ represents an inversion of imperial imaginaries which often operated through a negative understanding of ‘natives’ as both historically stuck in the past, and geographically fixed or ‘pinned’ to a homeland, or even understood as part of the land.Footnote 76 Understandings of ‘natives’ as static, was related to a series of policies to ‘conserve’ and ‘contain’ people, sometimes literally within reserves.Footnote 77 In opposition, ‘settlers’ were often associated with physical and existential movement, cosmopolitanism, progress, and historical agency.Footnote 78 Mamdani emphasises how, in indirect rule colonial Africa, the ‘native’ (indigenous) and ‘migrant’ (non-indigenous) figures were related to legal and political categories, rather than ontological realities. For example, ‘[s]ubject races were either nonindigenous immigrants, like the Indians of East, Central and Southern Africa, or they were constructed as nonindigenous by the colonial powers, such as, for example, the Tutsi of Rwanda and Burundi’.Footnote 79 Based on analysis of the ‘migrant’–‘native’ distinction, Mamdani argues the colonialism politicised indigeneity ‘first as settler libel against the native, and then as a native self-assertion’.Footnote 80

Crucially, both representations of people as ‘migrants’ and ‘natives’ are politicised, and form two sides of a binary between those perceived as mobile and those perceived as sedentary. This binary understanding is often deployed to either represent those perceived as mobile (migrants) as ‘errant’ or ‘out of place’, or to ‘fix’ and contain those deemed as rooted in the land (natives) in place. However, these categories do not neatly fit political realities. This is illustrated, for example, by current debates over whether descendants of enslaved and indentured labourers (including people in the US, as well as descendants of European and Indian indentured labourers in the Americas and Africa) should be understood as ‘migrants’, ‘natives’ or ‘settlers’.Footnote 81 Understandings of the Chagossians as an indigenous people potentially intervene in these debates by stretching the concept of ‘indigeneity’ away from an understanding of autochthony. However, this paper does attempt to answer the question of whether the Chagossians or other descendants of enslaved and indentured labourers should be understood as ‘migrants’, ‘settlers’, or ‘natives’. Instead, the paper explores how the Chagossians are problematised as ‘mobile’ (associated with the figure of the migrant), or ‘sedentary’ (associated with the figure of the native), and the political possibilities and geographic imaginaries which are produced through these representations.Footnote 82

Errantry and imperial mobilities

In contrast to the ‘sedentarist metaphysics’ of an international geographic imaginary which understands mobility as an exception to a norm of sedentarism and represents ‘errant’ as coterminous with ‘out of bounds’, this paper builds on work that addresses the role of movement and circulation in constituting global politics. This includes both a recognition of the imperial mobilities that constitute international order, and an exploration of alternative forms of ‘errant’ belonging that exist within and alongside this order. In making this argument, I start from a recovery of the imperial mobilities which were central to the colonial encounter. These mobilities were not epiphenomenal to the creation of apparently sedentary nation-states, or of the ‘West’ as a system of states, if the nation-state is understood first as an imperial-state,Footnote 83 and ‘the West’ is understood as an outcome of colonial encounter.Footnote 84 This points to the need to recognise mobility not as an alternative to national belonging or international order, but as constitutive of a globalised system of apparently sedentary societies. At the same time as recognising the centrality of imperial mobilities to apparently sedentary international order, I also propose the expansion of political vocabularies to recognise ‘errant’ or mobile forms of political relation which do not necessarily reproduce imperial or international politics, even if they exist within and alongside them.

I suggest that thinking with Édouard Glissant’s concept of errantry can advance these debates. Édouard Glissant is a Martiniquean poet and philosopher who is often read in relation to the work of Aime Cesaire, Frantz Fanon, and other francophone Caribbean anti-colonial theorists. While I focus on Glissant’s writing in Poetics of Relation, I read this in conversation with wider work that emphasises multiplicity, relationality, and movement, including work on ‘traveling cultures’,Footnote 85 exile and traveling theory,Footnote 86 rhizomatic thought,Footnote 87 oceans, diaspora and the Black Atlantic,Footnote 88 and Black geography and the archipelagic,Footnote 89 as well as broader work on Glissant in International Relations and Political Theory.Footnote 90 I focus on Glissant’s conceptualisations of ‘errantry’, but read this within a constellation of broader concepts including the archipelagic and creolisation.Footnote 91 By thinking with Glissant in the Indian Ocean, the paper works within broader Glissantian analysis of Indian Ocean Worlds and transoceanic relations,Footnote 92 and acknowledges the contextual specificities of these contexts as well as the imperial intimacies which span them.Footnote 93 Glissant’s thought unfolds through his analysis of the specific context of the Caribbean, and while it resonates in the Indian Ocean it does not transpose directly. As Shilliam notes, ‘Glissant grounds this inquiry within the uprooting forced upon various peoples through the European colonisation of the Caribbean, foremost of which are the genocide of the indigenous peoples and the shipments of enslaved Africans … [and] the way in which the meaningful pursuit of self-determination by uprooted Africans in Martinique has been consistently “overdetermined” by France’.Footnote 94

While geographically distant, the Chagos Islands and the French Caribbean are connected through imperial intimacies as francophone postcolonial archipelagos which were characterised by slavery and plantation economies. They share key elements of what Vergès identifies as ‘Creole worlds’: ‘deportation, forced exile, a world of men, a deeply unequal and violent society, institutionalized racial hierarchy’.Footnote 95 However, with Vergès, ‘no Creole society is exactly similar to another’.Footnote 96 Indeed, generalising and universalising conceptual frameworks from one context to another entails political risks. As Vergès notes in relation to creolisation (but with resonances for the concept of ‘errantry’) ‘as creolization tends to be connected with diasporic experience, dispersal, and the critique of “roots”, it can look suspicious to groups which fight for recognition of “identity”’.Footnote 97 Because of this, Vergès argues that creolisation in French Guyana, for example, ‘must coexist with the indigenous struggle for land rights and respect for their customs. Otherwise, creolization runs the risk of becoming bland and acceptable to the world of liberalism’.Footnote 98 On this basis, there is no general application of concepts such as ‘creolisation’ or ‘errantry’ outside of the specific contexts they are made sensical within, and the political possibilities they create are not predetermined. Therefore, I do not intend ‘errantry’ as a universalising concept, but one which should be interpreted in relation to specific social and political contexts.

On this basis, I suggest that thinking with Glissant’s concept of ‘errantry’ in the context of the Chagos Islands can advance a mobile understanding of ‘rootedness’, which maintains ‘the idea of rootedness but challenges that of a totalitarian root’ and understands ‘the root’ to exist in Relation.Footnote 99 This Glissantian understanding of identity means that ‘identity is no longer completely within the root but also in Relation’.Footnote 100 While both ‘errantry’ and ‘imperial mobility’ are mobile and relational, I follow Glissant’s understanding of errantry as a form of relationality which involves the recognition of the other (‘Relation’). In contrast to ‘bad’ imperial relations of domination, imposition, and disavowal of constitutive relationality, Glissant’s understanding of ‘Relation’ has a positive valence and ‘proposes a situation of equality with, and respect for, the other as different from oneself’.Footnote 101 As McKittrick argues, ‘imperial relationalities are the death of (Glissant’s) relation’.Footnote 102 Therefore, imperial mobilities are not ‘errant’ in a Glissantian sense, as they do not disturb the ideal of a singular root, but merely impose it elsewhere. As Glissant writes: ‘Conquerors are the moving, transient root of their people’.Footnote 103

While Glissant’s ‘errantry’, which is also translatable as ‘wandering’,Footnote 104 implies movement and fluidity, it does not directly translate to ‘mobility’. First, because errantry is distinct from other forms of mobility, such as colonial expansion. Second, because errantry is also a way of thinking. As Glissant writes: ‘errant thought, silently emerges from the destructuring of compact national entities that yesterday were still triumphant and, at the same time, from difficult, uncertain births of new forms of identity that call to us’.Footnote 105 Building on this, Glissant emphasises that ‘errant thought’ is available to people who are ‘immobile’. As Glissant notes: ‘At this point we seem to be far removed from the sufferings and preoccupations of those who must bear the world’s injustice. Their errantry is, in effect, immobile. They have never experienced the melancholy and extroverted luxury of uprooting. They do not travel’.Footnote 106 This implies the possibility to consider ‘rootedness’, identity, and relationality to be errant, even if individual subjects are not mobile. Therefore, in proposing an ‘errant’ conceptualisation of politics, I am not proposing a way of being in which everyone is mobile or moving all the time, but one possible way of thinking about ‘rootedness’ as relational, mobile, and fluid, rather than contained and deriving from a ‘single unique root’– even in contexts where little displacement is visible. This not only inverts sedentarist understandings of the ‘errant’ as ‘out of bounds’, and replaces them with mobile understandings of relationality, but also recognises that mobile relationality is not in and of itself politically desirable.

Movement metaphors in the displacement of the islanders

The FCO representations of Chagossians as mobile (or ‘errant’ in the sense of being out of place) reproduce an international geographic imaginary which understands political legitimacy as deriving from sedentarism, even when the islanders were displaced to make way for an equally mobile political entity: empire. Representations of the islanders as a mobile population were used to justify their displacement, both internally and externally. For example, one official anticipated that the displacement would not disturb the islanders, as ‘[t]he copra plantation workers are quite used to being moved about … [and are] unlikely to be disturbed by change of location providing that there is no deterioration in their living standards’, and hoped that the displacement would be carried out in a discreet way, so that ‘[t]he removal of the rest of the Chagos population … [would] attract the minimum outside interest’.Footnote 107 These representations were acknowledged at the time to be strategic and deliberately misleading. For example, in 1966, the Secretary of State for the Colonies wrote that ‘[t]he legal position of the inhabitants would be greatly simplified from our point of view – though not necessarily from theirs … if we decided to treat them as a floating population’.Footnote 108 Moreover, officials were well aware that many of the islanders had multi-generational attachments to the islands. Critical of this approach (but in line with the general belief that it is acceptable to move ‘transient’ people), another FCO official noted: ‘We then find, apart from the transients, up to 240 “ilois”* whom we propose either to resettle (with how much vigour of persuasion?) or to certify, more or less fraudulently, as belonging somewhere else’.Footnote 109

The representation of the islanders as mobile is linked to the use of immigration legislation in their displacement, essentially rendering the islanders ‘migrants’. While the islanders had been prevented from accessing the islands through a variety of means since 1968, a 1971 Immigration Ordinance ‘made it unlawful for a person to enter or remain in BIOT without a permit and allowed those remaining to be removed’.Footnote 110 This made it a criminal offence for any Chagossian to remain on the islands, or for anyone to be on the islands without a permit.Footnote 111 In 2004, the UK government used immigration legislation again, enacting constitutional and immigration orders which denied the islanders’ right of abode, which had been recognised in an earlier case.Footnote 112 This indicates that immigration legislation is not only used to filter people at the border, but also to displace people with existing ties to land. It emphasises how the figure of the ‘migrant’ is not necessarily defined in relation to cross-border mobility, but to understandings of belonging or being ‘out of place’ or ‘errant’.

Despite an internal acknowledgment that the strategy to represent the islanders as a ‘transient’ ‘floating population’ of ‘contract workers’ was deliberately misleading, FCO memos reflect the contradictory belief that an apparently mobile people would be easy to relocate and that their displacement would be unlikely to attract controversy. This logic is coherent with a sedentarist international geographic imaginary of political belonging being contained within nation-states. It denies the possibility that a historically mobile (or currently mobile) people could have grounds to dispute enforced displacement. This logic is at odds with an errant conceptualisation of politics, which could recognise both contemporary practices of mobility, and histories of mobility as legitimate sources of ‘rootedness’, and a basis from which to make political claims and dispute displacement.

Erasing the ‘Ilois’ identity category

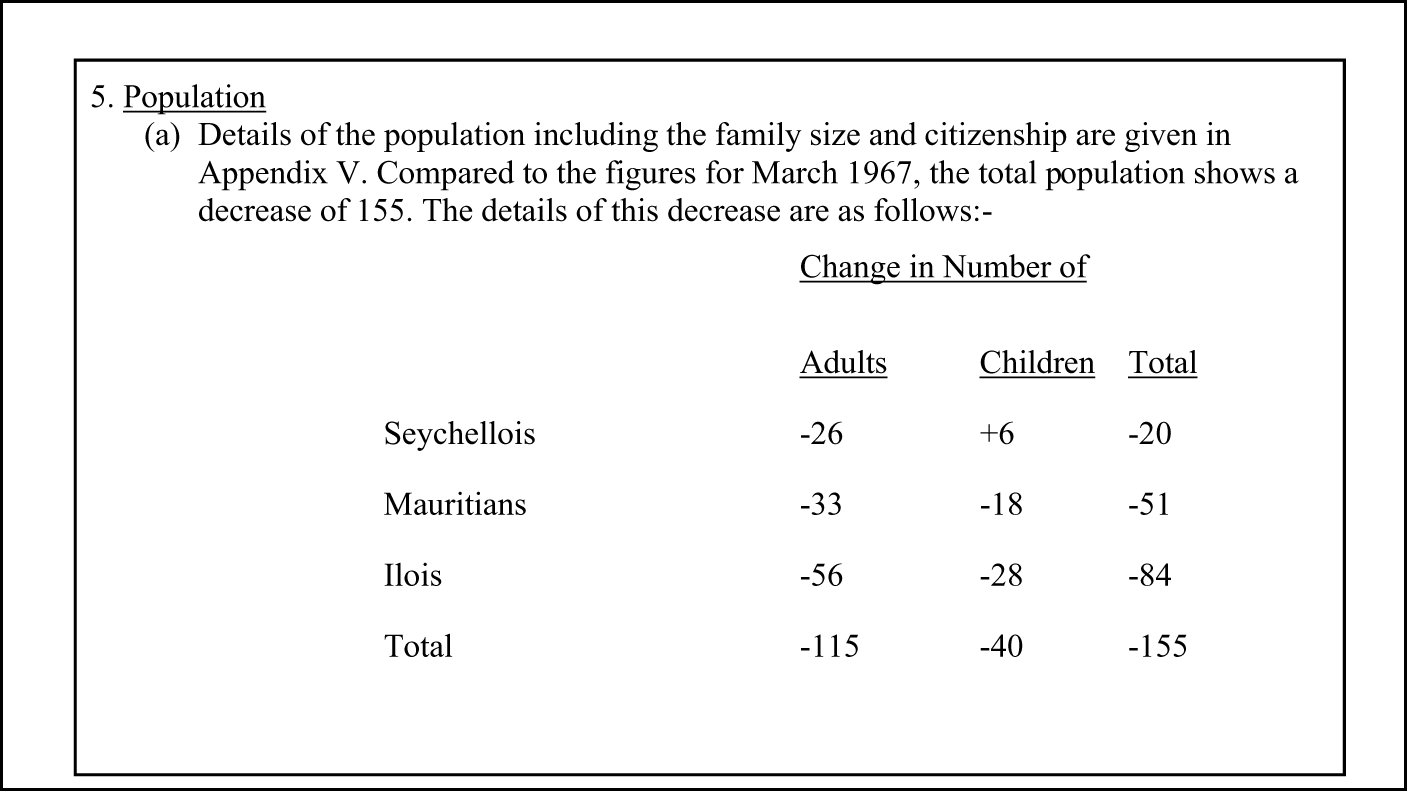

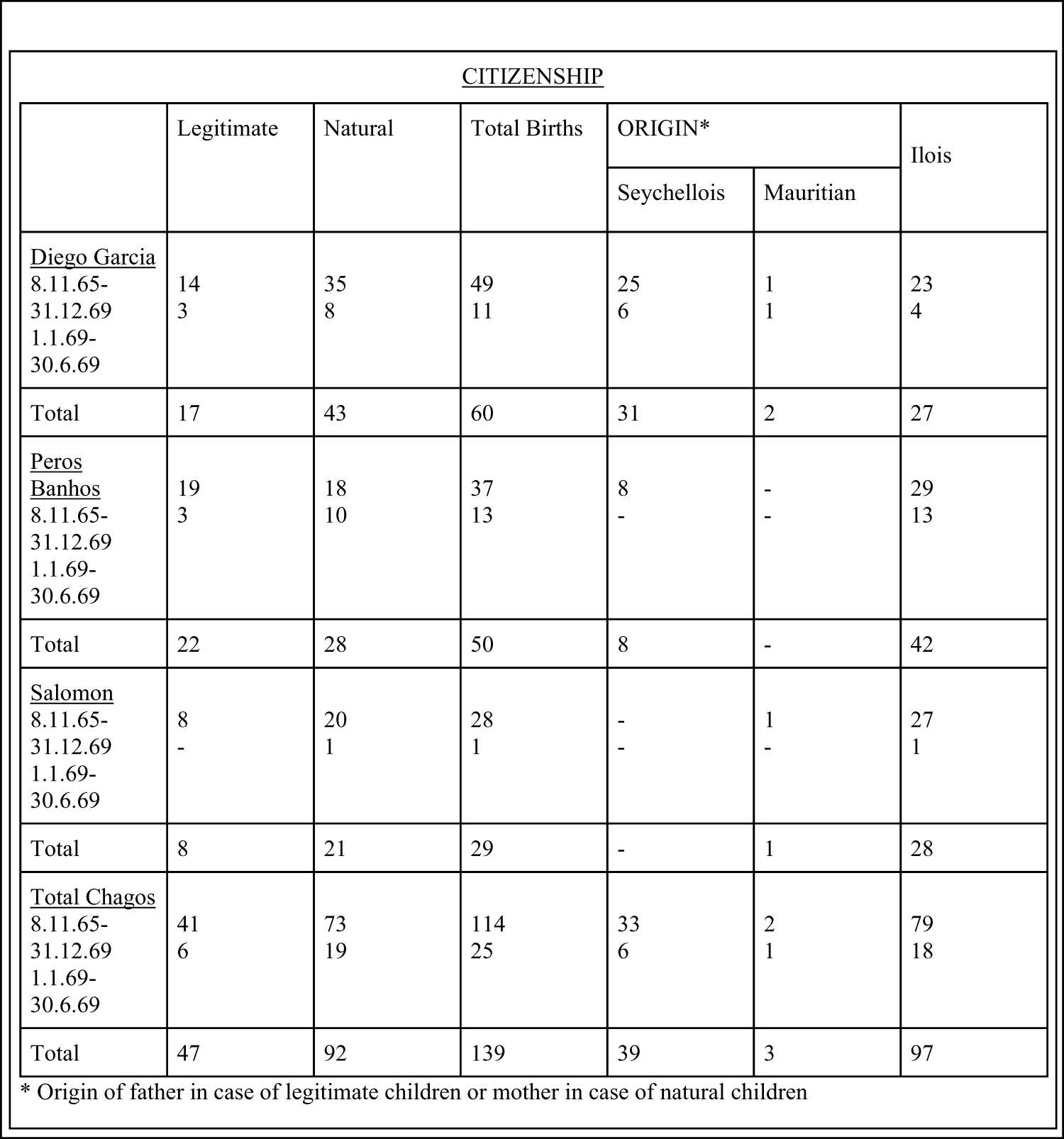

The representation of the islanders as mobile was linked to the erasure of the ‘Ilois’ identity category, which had previously been widely used by the FCO to differentiate the population of the archipelago as ‘Ilois’, ‘Seychellois’, and ‘Mauritian’ (see Figure 4).Footnote 113 In a telegram to Washington the FCO identified most of the islanders as ‘Ilois’, ‘some of whom have lived on the atolls for two or three generations’.Footnote 114 In addition, those categorised as ‘Mauritian’, or ‘Seychelloise’ may also have born on the Chagos islands and, officials noted, could also be considered ‘Ilois’ on this basis. For example, in a draft letter to J. R. Todd by K. R.Whithall, 4 August 1969, Whithall asks for clarification of ‘the division between Mauritians and Ilois’ amongst those who had ‘returned’ to Mauritius from Chagos in 1968, as she notes that their ‘birth place’ was recorded as ‘Chagos in every case’. Whithall suggests that ‘if this column refers in toto to all the persons listed … then all would appear to be Ilois.’Footnote 115 The fact that those categorised as ‘Mauritian’ or ‘Seychelloise’ may have been born on Chagos is supported by statistics on births (see Figure 6) which illustrates the categorisation of children born on Chagos as ‘Mauritian’ and ‘Seychelloise’ as well as ‘Ilois’.Footnote 116 At displacement, this was a reality the officials wanted to hide, noting that ‘some of the contract labourers of Mauritian origin have lived on the islands for one or two generations and (although this should not be admitted to the Mauritian Prime Minister) are dual citizens of Mauritius and the UK and colonies’.Footnote 117

Figure 4. Reproduction of TNA FCO 37/388 table showing categorisation of ‘Seychellois’, ‘Mauritians’, and ‘Ilois’.

In order to relocate all of the islanders to Mauritius and the Seychelles, UK FCO officials suggested that no references be made to a distinct ‘Ilois’ group in communications with Mauritian officials. This posed a challenge, as one proposed plan was to resettle the Ilois on the nearby island of Agalega to continue producing copra, but officials were not able to explicitly recruit ‘Ilois’ people for this or differentiate between ‘Mauritians’, ‘Seychelloise’, and ‘Ilois’. As one official stated: ‘[w]e would, of course, prefer Ilois to be recruited, but as we do not wish to make any distinction between Ilois and Mono Mauritians … we would not wish to place any emphasis on the group to be recruited’.Footnote 118 Three days later, Greatbatch wrote that the Chagos Agalega Company had succeeded in recruiting 14 families from Mauritius for Agalega, eight of whom ‘can definitely be identified as Ilois’, and the ‘remaining 6 have typical Ilois names’. He affirmed that ‘Moulinie’s standing instruction to Rogers is that Ilois should have preference in recruitment as they are used to Island Maritime Province and Copra washing’, however, alluding to the intent to simultaneously erase the Ilois’ category, he wrote: ‘Ilois in this case may be widely interpreted as those with experience on islands but can’t do better without attracting undesirable attention’.Footnote 119

The FCO attempt to erase the ‘Ilois’ identity category reflects a preemptive defense against an identity-based claim to land or territory. As articulated at the time: ‘The existence of the Ilois, and their possible claim to belong to BIOT, could cause us considerable problems, particularly in the United Nations’.Footnote 120 This reproduces an international imaginary of identity-based claims to territory which resonates with Glissant’s framing of ‘root identity’, which ‘rooted the thought of self and of territory’, and ‘is ratified by a claim to legitimacy that allows a community to proclaim its entitlement to the possession of a land, which thus becomes a territory’.Footnote 121 In contrast, Glissant proposes ‘relation identity’ as a form of identity that ‘does not think of land as territory’, but does still allow for meaningful relationships with land.Footnote 122 By disavowing the ‘Ilois’ identity category, and claiming the islands as the ‘British Indian Ocean Territory’, the FCO affirm a legal order that understands ‘root identity’ as a legitimate source from which to make and contest territorial claims. This highlights the political stakes and strategic potential of reconstituting a Chagossian indigenous identity, but both strategies affirm the underlying logic that an identity-based claim to belonging on the islands strengthens the Chagossians’ grounds to contest their displacement. However, limited analysis suggests that even if the islanders make identity-based claims to land, they do not necessarily mobilise the same understanding of territory as the FCO. For example, in 2024 written evidence to the UK Foreign Affairs Sub-Committee on the Overseas Territories, Olivier Bancoult refers multiple times to the islands as ‘home’, and only once as ‘the territory’.Footnote 123 This contrasts with FCO framings of land as territory (implying possession), and emphasises differences as well as overlaps in FCO and Chagossian framings, even if both are made through legal frameworks which emphasise bounded-identity based claims to land.

Present-day narratives and the centrality of ‘the contract’

Despite the now public knowledge of the FCO’s awareness of multi-generational inhabitation of the islands, current government communications continue to represent the islanders as a transient population of contract workers who belonged elsewhere. In 2024, the ‘History’ section of the official BIOT gov.uk website stated:

‘As for the population of the islands, after emancipation some slaves became contract employees; the population changing over time by import of contract labour from Mauritius and, in the 1950s, from Seychelles, so that by the late 1960s, those living on the islands were contract employees of the copra plantations. Neither they, nor those permitted by the plantation owners to remain, owned land or houses. They had licences to reside there at the discretion of the owners and moved from island to island as work required.

The people affected by these closures were the Mauritian and Seychellois contract workers and their families, who were then given the choice of returning to Mauritius or Seychelles. The majority chose Mauritius where they had close ties and were moved between 1968 and 1973’. Footnote 124

This quote acknowledges that some formerly enslaved people remained on the islands after abolition, but emphasises that the population changed over time with the import of contract labour, moving from island to island. It also claims that the ‘contract workers’ returned to Mauritius and the Seychelles. There is no account of what happened to the descendants of the enslaved labourers, other than noting ‘the population changing over time by import of contract labour’, a sleight of language that implies the disappearance of the original enslaved people.Footnote 125 This is not only inaccurate, but also reaffirms a logic that transient people are displaceable, and political belonging derives from sedentarism.

The statement also links the category of ‘contract worker’ to ‘mobility’, opening up questions about the role of the contract in understandings of belonging. This tracks with the strategy in the 1960s. In 1969, the British Foreign Secretary suggested that Prime Minister Harold Wilson presented the displacement of the islanders to the UN, as ‘a change of employment for contract workers – rather than as a population resettlement’.Footnote 126 This representation of ‘contract workers’ as having no claim to belonging other than a contractual agreement, has implications for contemporary understandings of ‘economic migration’. It also resonates with debates over the role of the contract in the transition from slavery to indenture, in making ‘freedom’ a technical and legal, rather than moral and political question.Footnote 127 The FCO representation of the islanders as ‘contract workers’ attempts to legitimise their displacement by presenting their relationship to the island as being defined by a contract. At the core of these debates are not only the questions of whether or not the islanders were ‘contract workers’, and whether or not they had inhabited the islands for multiple generations, but also the implicit question of whether or not ‘contract workers’ could make any claim to political belonging.

Overall, the use of movement metaphors was (and continues to be) central to the attempted legitimisation of the displacement of the islanders. Movement terminology such as ‘transient’, ‘floating population’, and the reference to the islanders as people who were ‘quite used to being moved about’, and ‘moved from island to island as work required’ were coupled with descriptors of the islanders as ‘temporary residents’, ‘contract workers’, ‘contract employees’, and people who belonged ‘somewhere else’. These ideas all resonate with contemporary understandings of ‘migrants’ as people who are out of place, associated with mobility, and ‘errant’ in the sense of ‘leaving home’ or ‘being out of bounds’. Indeed, the introduction of the 1971 immigration ordinance that prevented the Chagossians from returning to their home, and 2004 legislation to further enforce this, rendered attempts to return to the islands as ‘migration’, and the islanders as potential ‘migrants’. ‘Migrancy’ in this case does not reflect the islanders’ pre-existing mobility but acts as a discourse that enabled their enforced exile.

Understandings of indigeneity and the legal contestation of the islanders’ displacement

At the same time, the legal contestation of the islanders’ displacement hinges on parallel claims to permanent inhabitation, and the argument that the Chagossians constitute a discrete ‘indigenous’ people. Within international law, indigenous status gives the Chagossians access to legal arguments to which they would not otherwise have recourse.Footnote 128 This framework lends itself to representations of the Chagossians as relatively sedentary, and emphasises their multi-generational attachment to place, in order to make a claim for their right to resettle the islands. This reproduces some of the logics of an international geographic imaginary that privileges sedentarism and identity-based claims to land. On one hand, this highlights the challenge of recognising an ‘errant’ politics that emphasises the present-day and historical significance of mobility as a ‘root’ of identity and a basis for political claims. On the other hand, it emphasises the multiplicity of identity-based claims to land, and the fact that they may create political possibilities which do not necessarily reproduce imperial expansion or national intolerance.

Legal understandings of indigenous status are open to interpretation, but often invoke: i) attachment to place; ii) pre-colonial belonging; and iii) the existence of a distinct ethnic or cultural group. Drawing on multiple definitions of indigenous status, Allen argues that the Chagossians constitute an ‘indigenous people’, in part because of their ‘self-identification as an indigenous people’, as well as their ‘communal attachments to “place”; experience of severe disruption, dislocation and exploitation; ongoing oppression/exclusion by dominant societal groups; and distinct ethnic/cultural groups’.Footnote 129 However, he notes that the Chagossians do not fit the common understanding of indigenous status deriving from having a link with pre-colonial societies. For example, the commonly taken Martinez-Cobo definition of indigenous status involves ‘having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories’.Footnote 130 Based on this definition, the islanders would not fulfil the criteria of historical precedence, nor inhabitation of the islands before colonisation, as French settlers were the first to occupy the islands.Footnote 131 In contrast, the Mauritian government disputes the claim to indigenous status and argues that the Chagossians are a Mauritian national minority, rather than an indigenous people, because the Chagos Islands were uninhabited until the nineteenth century.Footnote 132 This shows that in some ways an understanding of the Chagossians as indigenous is at odds with a state-centric international imaginary of national majorities and minorities.Footnote 133 It also suggests that Chagossian indigenous status may be increasingly politically expedient or even necessary in the current context of negotiations over Mauritian sovereignty over the Chagos Islands. At the same time, an understanding of political belonging based on discrete ethnic identity, linked to claims to land or territory, in many ways parallels assumptions which underpin this international legal and geographic imaginaries, even if it opens up different political possibilities.

The legal significance of the islanders’ status as a permanent population is apparent in academic work on the displacement of the Chagossians. For example, Allen argues that the BIOT was ‘inhabited by a permanent population and was thus a non-self-governing territory under Chapter XI of the UN Charter’,Footnote 134 and critiques the exile of ‘the Chagossians from their ancestral homeland’.Footnote 135 The multi-generational inhabitation of the islands is often emphasised, for example, in Vine’s description of the islanders as people who ‘built their own houses, inhabited land passed down from generation to generation, and kept vegetable gardens and farm animals’.Footnote 136 This emphasis on multi-generational inhabitation, while emphasising the inaccuracy of FCO representations, also contrasts with an errant conceptual framing which could explore Chagossian multi-generational histories of movement as an equally meaningful source of ‘rootedness’, while recognising their geographic connectedness to the islands.

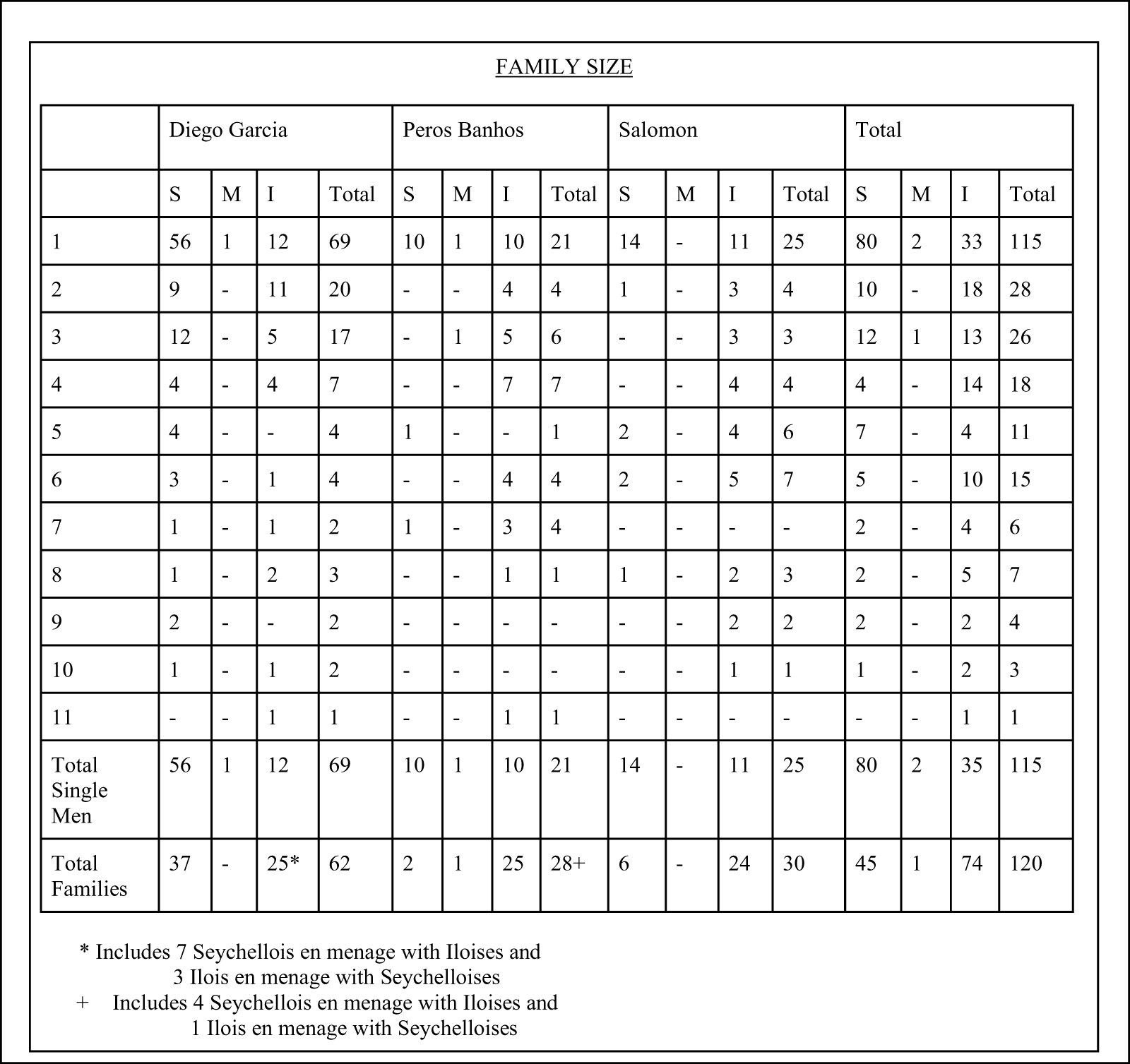

Moreover, at the time that the islanders were exiled, the administrative category of ‘Ilois’ was not stable or fixed. In this sense, the construction of ‘Chagossian’ as a discrete indigenous group was sharpened after and through the experience of displacement. An example of the fluidity of the FCO category of ‘Ilois’ is the role of marriage in determining ‘Ilois’ identity. The FCO documents refer to ‘Seychellois’, ‘Ilois’, and ‘Mauritian’ people being ‘en menage’, or married, with one another (see Figures 5 and 6).Footnote 137 A footnote on these documents notes that children’s citizenship, or ‘origin’, derived from the father in the case of ‘legitimate’ births (meaning within marriage), and the mother in the case of ‘natural’ births (meaning outside of marriage).Footnote 138 This means that a child whose father was ‘Ilois’ and mother was ‘Mauritian’ would be categorised as ‘Ilois’ if the parents were married, and ‘Mauritian’ if the parents were unmarried – pointing to the contingency of these categories. Equally, as some FCO officials noted, many of those categorised as ‘Mauritian’ were in fact born on the islands. This means that the identity categories of ‘Ilois’, ‘Mauritian’, or ‘Seychellois’ were contingent on circumstance and may have changed over time, either in one person’s lifetime, or generationally, sometimes as a result of arbitrary bureaucratic processes. Claiming a discrete indigenous identity linked to land as a means of contesting the displacement through international law may have the effect of fixing and bounding a Chagossian identity, as well as ‘rooting’ it in a homeland.

Figure 5. Reproduction of TNA FCO 37/388 showing marriages between Seychellois and Ilois.

Figure 6. Reproduction of TNA FCO 37/388 table showing children’s citizenship being contingent on marital status of parents.

This suggests that through the process of displacement, a discrete ‘Chagossian’ identity has taken on a meaning and cohesiveness that the ‘Ilois’ category did not have as a category of governance before displacement, and that this identity is linked with an ideal of a fixed homeland. When the islanders were displaced, inhabitants were understood as ‘Seychellois, ‘Mauritian’, and ‘Ilois’. This raises the question of whether only the ‘Ilois’ have a right to return, and whether ‘Chagossian’ would continue to be a discrete identity category, if it was no longer constituted by displacement. In contrast, an understanding of political identity and belonging emerging in movement resonates with Stuart Hall’s writing on Caribbean diaspora. Hall notes ‘the endless ways in which Caribbean people have been destined to “migrate”’,Footnote 139 and argues that the ‘New World’, ‘is the signifier of migration itself – of travelling, voyaging and return as fate, as destiny’. In opposition to understandings of identity grounded in territorial homeland, Hall gives an account of identity being continually made and remade in movement, and an understanding of identities which are ‘constantly producing and reproducing themselves anew, through transformation and difference’.Footnote 140 In relation to the Chagos Islands, it would not only be the Chagossians’ identity which is made and remade through travel and movement, but also British and US nationalisms which are produced through imperial expansion. As Engseng Ho has argued, ‘[t]he British became an imperial people – that is to say, they became a people as they became an empire’.Footnote 141 While pointing to the role of mobility in constituting identity, this also highlights the potential for the recognition of movement and relationality as a basis of political belonging to legitimise settler colonial and imperial claims to belonging, and the need to be attentive to this risk.

Conclusions: Errant politics and geographic connectedness

Despite decades of campaigning, and the recent agreement to cede sovereignty over the islands to Mauritius, it remains uncertain whether the Chagossians will ever be able to return to the archipelago they were displaced from, or at least to Diego Garcia. Debates over the Chagos Islanders are not only significant in relation to the islanders’ right to return, but articulate broader understandings of political belonging, identity, and relationships with land. The displaced Chagossians represent a people with histories of mobility and fluid identity, as well as long-standing relations with land and cultural specificity, but the legal framings of these debates emphasise only the long-standing relationships with land, and an ideal of bounded and discrete indigenous identity. On one hand, this counters the FCO attempts to falsely represent the islanders as mobile or errant as a means to deny them access to the islands. On the other hand, it reaffirms the logic that political belonging and access to land derive from sedentarism and discrete identity-based claims.

The paradox is that the US military base on Diego Garcia is now populated by an equally or more mobile population of soldiers and Filipino ‘contract workers’.Footnote 142 This represents not only another set of mobile people, but an illustration of the centrality of imperial mobilities (including those of in-between groups such as contractors) to maintain the US and UK as not only territorially bound sedentary nation-states, but mobile imperial polities that cut across national borders. By making the islanders appear ‘out of place’ due to their mobility, the FCO represent the Chagossians as belonging elsewhere. This reproduces an apparent norm of sedentarism and obscures the constitutive role of mobility (imperial and otherwise) as the basis of political order. In contrast, a recognition of these constitutive imperial mobile relations could lead to an understanding of mobile politics not as an alternative to international order, but as an already existing reality. Whether these relations are ‘errant’ in a Glissantian sense or ‘imperial’ has less to do with how ‘mobile’ or ‘static’ they are, and more to do with power asymmetries and modes of relation.

This analysis opens up room for further exploration of overlapping forms of mobile rootedness and geographic connectedness. Indeed, an emphasis on the islanders’ relationship with land is not at odds with an understanding of rooted errantry. For example, writing about ‘Maroons’, Glissant notes that their ‘resistance takes its strength [in part] from ... geographical connectedness (essential to survival in the jungle and absent in the descendants of slaves –alienated from the land that could never be theirs)’.Footnote 143 This points to an understanding of ‘geographic connectedness’ as a source of political resistance, which is opposed both to alienation from land, and to understandings of land as territory. Without the scope to fully explore the relations between ‘rooted errantry’ and land in this paper, this points to the possibility to make meaningful claims to land which are not defined by identity-based claims to land as territory, but by other forms of geographic connectedness that do not hinge on permanence or discrete identity.Footnote 144

Both the imperial mobilities that account for the presence of a military base on Diego Garcia and the histories of mobility that led to the inhabitation of the Chagos Archipelago point to ‘mobile roots’ as a source of political relationality and ‘rootedness’, if not belonging. By recognising the constitutive role of imperial mobilities, my aim is not to legitimise imperial or settler colonial politics as a basis from which to make political claims. Neither is it to invert the binary between movement and sedentarism, to privilege mobility over sedentarism. Instead, the paper aims to highlight the need for political frameworks that are able to recognise political claims based on histories and presents of movement, while remaining attentive to asymmetries of power. I propose that a Glissantian understanding of ‘errantry’ can provide an entry point into conceptualising forms of political belonging deriving from mobility and fluid identity, premised on a recognition of relationality and equality with the Other. This additional conceptual framework is necessary for politics which can recognise meaningful forms of geographic connectedness, as well as providing a vocabulary necessary for migrant and diasporic politics, which does not understand migrants, diasporas, travellers, or ‘minorities’ as being ‘out of place’, defined in relation to ethnic ‘homelands’, or pathologically placeless and geographically alienated.

Video Abstract

To view the online video abstract, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210525101034.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Sara Wong, Tarak Barkawi, Samson Okoth Opondo, Tarsis Brito, Nandini Dey, rémy-paulin twahirwa, Eva Leth Sørensen, Jaakko Heiskanen, Debbie Lisle, and Nivi Manchanda for their invaluable feedback and for conversations on various iterations of this article. I am grateful to BISA-CPD convenors Heba Youssef, Jenna Marshall, and Sharri Plonski for their generous support and for organising the Colonial, Postcolonial, and Decolonial Early-Career Researcher Paper Prize, as well as to Andrew Hom for feedback on the paper and all the RIS editors for their mentorship. I would also like to thank the organisers and participants of the IR502 research cluster at the LSE, the 2023 EISA Annual Conference, and the 2024 BISA Annual Conference, and my valued discussants at these events, respectively: Partha Moman, Renata Summa, and Quyn Pham. My gratitude also to three anonymous reviewers for their helpful and engaged comments.

Funding Statement

This article draws on research conducted as part of a PhD funded by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the Department of International Relations at the London School of Economics.