Introduction

Parents are typically their infants’ primary interactive partners, thereby providing a thoroughfare for infant learning across areas of development, including social interaction, emotion regulation, and communication (Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Prime, Graham, Rodrigues, Anderson, Khoury and Jenkins2019; Mesman et al., Reference Mesman, van Ijzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg2012; Vallotton et al., Reference Vallotton, Mastergeorge, Foster, Decker and Ayoub2017). Thus, caregiver behavior, especially sensitive responding to infant cues, is highly relevant in shaping the trajectory of child development. However, infants are far from passive recipients of parental caregiving (Fantasia et al., Reference Fantasia, Galbusera, Reck and Fasulo2019; Wu, Reference Wu2021). Infants actively participate in interactions and shape their caregiver’s behavior through affect, vocalizations, joint attention cues, and bids for attention (Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Hendricks, Haynes and Painter2007; Mills-Koonce et al., Reference Mills-Koonce, Gariépy, Propper, Sutton, Calkins, Moore and Cox2007; Murray et al., Reference Murray, De Pascalis, Bozicevic, Hawkins, Sclafani and Ferrari2016; Murray & Trevarthen, Reference Murray and Trevarthen2008). One understudied area of development that may help to explain the complex interplay between caregiver and infant behavior is sensory reactivity, which is the way infants respond to sensations produced by physical and social aspects of the environment. Infants who are over- or hyperreactive to sensations are often excessively fussy or difficult to soothe (McGeorge et al., Reference McGeorge, Milne, Cotton and Whelan2015), while infants who are under- or hyporeactive may seem to ignore or be unaware of caregivers’ attempts at interaction (Baranek et al., Reference Baranek, Watson, Boyd, Poe, David and McGuire2013). Thus, both hypo- and hyperreactive patterns could shape caregiver-infant interaction. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the degree to which infant sensory reactivity influences caregiver behavior across the first year of life and vice versa.

Sensory reactivity in infancy

Sensory reactivity can be characterized by two-dimensional constructs: over-responding (hyperreactivity) or under-responding (hyporeactivity) to sensory stimuli. While extreme levels of hypo- and hyperreactivity are commonly recognized as symptoms of autism and other neurodevelopmental conditions, up to 12% of children without other developmental problems exhibit patterns of sensory reactivity that interfere with their functioning (Bar-Shalita et al., Reference Bar-Shalita and Cermak2016; Ben-Sasson et al., Reference Ben-Sasson, Carter and Briggs-Gowan2009; Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Shepherd and Lane2008; Ringold et al., Reference Ringold, McGuire, Jayashankar, Kilroy, Butera, Harrison, Cermak and Aziz-Zadeh2022). Hypo- and hyperreactivity can impact important activities, such as feeding, bonding with parents, language acquisition, and sleep (Baranek et al., Reference Baranek, Watson, Boyd, Poe, David and McGuire2013; Farrow & Coulthard, Reference Farrow and Coulthard2012; Kerley et al., Reference Kerley, Meredith and Harnett2023; McGeorge et al., Reference McGeorge, Milne, Cotton and Whelan2015; Mubarak et al., Reference Mubarak, Cyr, St.-André, Paquette, Emond-Nakamura, Boisjoly, Palardy, Adin and Stikarovska2017; Tauman et al., Reference Tauman, Avni, Drori-Asayag, Nehama, Greenfield and Leitner2017; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Patten, Baranek, Poe, Boyd, Freuler and Lorenzi2011), and child hyperreactivity is associated with elevated stress and poor mental health outcomes among caregivers (Gee et al., Reference Gee, Aubuchon-Endsley and Prow2021; Gourley et al., Reference Gourley, Wind, Henninger and Chinitz2013). Signs of sensory hypo- and hyperreactivity become apparent as early as 4-6 months of age in infants with no other developmental concerns (Dunn & Daniels, Reference Dunn and Daniels2002; Eeles et al., Reference Eeles, Spittle, Anderson, Brown, Lee, Boyd and Doyle2012) and continue to develop throughout childhood (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Sideris, Watson, Crais and Baranek2022). Throughout development of sensory reactivity (e.g., lower levels of both hypo- and hyperreactivity), behavior related to hyperreactivity tends to decrease from infancy to middle childhood, while behavior related to hyporeactivity remains largely stable and low (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Sideris, Watson, Crais and Baranek2022). Children with more severe sensory reactivity presentations tend to remain elevated across the same time period (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Sideris, Watson, Crais and Baranek2022).

According to the Optimal Engagement Band Model (Baranek et al., Reference Baranek, Reinhartsen and Wannamaker2001; Campi et al., Reference Campi, Choi, Chen, Holland, Bristol, Sideris, Crais, Watson and Baranek2024), patterns of sensory hypo- and hyperreactivity are defined based on two thresholds: orientation and aversion. The orientation threshold is the intensity of input needed to elicit an orienting response, while the aversion threshold is the intensity of stimulus that elicits an aversive or defensive response. These thresholds vary widely, such that stable, between-person variations occur due to underlying physiological traits (McIntosh et al., Reference McIntosh, Miller, Shyu and Hagerman1999), and within-person fluctuations occur throughout the day due to physiological and emotional states (Fafrowicz et al., Reference Fafrowicz, Bohaterewicz, Ceglarek, Cichocka, Lewandowska, Sikora-Wachowicz, Oginska, Beres, Olszewska and Marek2019). Sensory hyporeactivity is characterized by a chronically elevated orientation threshold, such that individuals displaying higher levels of this phenotype require a greater intensity of sensation to elicit a response, such as looking toward a stimulus. In other words, an individual displaying greater hyporeactivity is less likely to notice stimuli in their environment than someone with more typical sensory reactivity. Behaviorally, this elevated orientation threshold manifests as unawareness, unresponsiveness, or tendency to ignore social and/or physical sensations in the environment. In contrast, hyperreactivity involves a low aversion threshold, where everyday sensations can be experienced as so intense that they yield a defensive or avoidant response. That is, a person displaying greater hyperreactivity is more likely to have a negative or stress response to stimuli than someone with more typical sensory reactivity. Hyperreactivity, therefore, presents as distress during common experiences, such as taking a bath or walking through a brightly lit store. Because hypo- and hyperreactivity are defined based on different thresholds (orientation versus aversion), they are distinct constructs, rather than two ends of the same spectrum, and can even co-occur (Ausderau et al., Reference Ausderau, Furlong, Sideris, Bulluck, Little, Watson, Boyd, Belger, Dickie and Baranek2014; Baranek et al., Reference Baranek, David, Poe, Stone and Watson2006; Campi et al., Reference Campi, Choi, Chen, Holland, Bristol, Sideris, Crais, Watson and Baranek2024).

Parental behavior and infant sensory reactivity

Studies of children adopted out of orphanage care, a system of extremely insensitive or absent caregiving, have established a link between neglectful early caregiving and sensory hyperreactivity later in childhood (Cermak & Daunhauer, Reference Cermak and Daunhauer1997; Leal et al., Reference Leal, Alba, Cummings, Jung, Waizman, Moreira, Saragosa-Harris, Ninova, Waterman, Langley, Tottenham, Silvers and Green2023; Silvers et al., Reference Silvers, Goff, Gabard-Durnam, Gee, Fareri, Caldera and Tottenham2017). However, it is not yet understood how variability within the spectrum of typical parental caregiving may shape the development of infant sensory reactivity nor vice versa. To date, associations between caregiver sensitivity and infant sensory reactivity have been studied primarily in infants at elevated likelihood of autism (Campi et al., Reference Campi, Choi, Chen, Holland, Bristol, Sideris, Crais, Watson and Baranek2024; Grzadzinski et al., Reference Grzadzinski, Nowell, Crais, Baranek, Turner‐Brown and Watson2021; Kinard et al., Reference Kinard, Sideris, Watson, Baranek, Crais, Wakeford and Turner-Brown2017). For example, co-occurring hypo- and hyperreactivity, which is most common in infants who go on to develop autism (Baranek et al., Reference Baranek, David, Poe, Stone and Watson2006), is cross-sectionally associated with more responsive parenting compared to hypo- or hyperreactivity in isolation (Campi et al., Reference Campi, Choi, Chen, Holland, Bristol, Sideris, Crais, Watson and Baranek2024). Infants demonstrating sensory hyporeactivity also have caregivers who concurrently use more play-based response strategies (Kinard et al., 2017). Importantly, caregiver verbal responsiveness across the second year of life attenuates the negative association between sensory hyporeactivity at 14 months and communication skills at 23 months (Grzadzinski et al., 2021). Taken together, these results suggest an association between caregiver responsiveness and infant sensory reactivity, especially hyporeactivity. However, the longitudinal directionality and reciprocity of these associations is yet unknown. Because of the prevalence of elevated sensory hypo- and hyperreactivity in the general population (Bar-Shalita et al., Reference Bar-Shalita and Cermak2016; Ben-Sasson et al., Reference Ben-Sasson, Carter and Briggs-Gowan2009; Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Shepherd and Lane2008; Ringold et al., Reference Ringold, McGuire, Jayashankar, Kilroy, Butera, Harrison, Cermak and Aziz-Zadeh2022) and lengthy developmental trajectories of sensory processing (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Sideris, Watson, Crais and Baranek2022), further research is needed to understand these associations (1) outside the context of early signs of autism and (2) longitudinally.

Current study

In the current proof-of-concept investigation, we tested the following research question: to what extent are maternal behavior and infant sensory reactivity reciprocally influential from infant age 6 months to 12 months? Infant sensory reactivity was defined dimensionally by two constructs: hypo- and hyperreactivity, characterized by a derived measurement tool to maximize the impact of extant data, and maternal sensitivity to nondistress and intrusiveness were measured observationally. We used cross-lagged panel modeling (CLPM), which evaluates both autoregressive and cross-lagged effects over multiple waves of data collection, thereby providing a closer approximation of causal links between variables than previous studies. This investigation did not include strong, direct a priori hypotheses, due to limited previous research on the directionality of these effects. It contributes to the literature in several ways: (1) by examining whether infant hypo- and hyperreactivity are related to the degree of responsiveness of maternal behavior and type of responsive behavior (i.e., sensitivity versus intrusiveness); (2) extending study of sensory reactivity and maternal behavior to a community sample; and (3) testing the reciprocal effects of infant and maternal behavior.

The first CLPM we constructed examined infant hyperreactivity and maternal sensitivity to nondistress. Infants experiencing sensory hyperreactivity tend to have fewer periods of nondistress with shorter duration than infants with typical sensory reactivity (McGeorge et al., Reference McGeorge, Milne, Cotton and Whelan2015). Because of the lower frequency of nondistress in infants displaying sensory hyperreactivity, mothers of these infants may have fewer opportunities to develop sensitivity to nondistress. Thus, their infants may receive less exposure to this critical developmental input.

The second model included infant hyperreactivity and maternal intrusiveness. It has been hypothesized that maternal intrusiveness increases infant and child threat perception and anxiety (Affrunti & Ginsburg, Reference Affrunti and Ginsburg2012; Rork & Morris, Reference Rork and Morris2009; Wu, Reference Wu2021), and children with hyperreactivity tend to experience a broader range of sensations as threatening, aversive, or anxiety-inducing. Therefore, it is possible that maternal intrusiveness may be perceived as more threatening for those prone to hyperreactivity, thereby increasing hyperreactivity over time. Caregivers’ stress responses to infant distress resulting from sensory hyperreactivity may then increase the degree of intrusive behavior they display (Chan & Neece, Reference Chan and Neece2018).

The third model included infant hyporeactivity and maternal sensitivity to nondistress, and the fourth tested longitudinal associations between infant hyporeactivity and maternal intrusiveness. Study of infant behaviors conceptually related to sensory hyporeactivity is lacking in the literature, so the models involving hyporeactivity were exploratory in nature.

Method

We examined cross-lagged and autoregressive effects of infant sensory hypo- and hyperreactivity on maternal sensitivity and intrusiveness to test the reciprocity of these constructs over time in a well-characterized community sample. Ethical approval for procedures in the parent studies was granted by the university’s Institutional Review Board, and parents provided written informed consent for themselves and their infants.

Participants

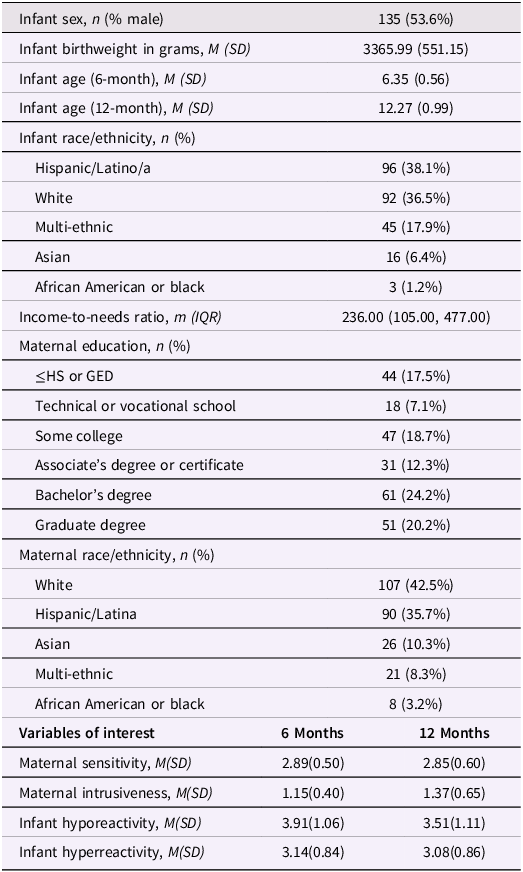

The sample comprised participants from two ongoing studies both with recruitment at the end of the first trimester or early second (N = 252; n = 166 from Cohort 1; n = 86 from Cohort 2). At the first assessment for this study, infants were M age = 6.35 months (SD = 0.56); at the second, infants were M age = 12.27 months (SD = 0.99). Inclusion criteria were maternal age ≥ 18 years, English-speaking, and singleton pregnancy. Exclusion criteria were uterine or cervical abnormalities and smoking, drug, or alcohol use. Demographic information and descriptive data regarding the variables of interest can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Participant demographics and descriptive data

Measures

Sensory reactivity

We used the Infant Behavior Questionnaire – Sensory Subscales (developed for the purposes of this study; see Supplement A) from a subset of Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised (IBQ-R; Gartstein & Rothbart, Reference Gartstein and Rothbart2003) items to maximize the utility of extant data to explore sensory reactivity in infancy in this well-characterized sample. The IBQ-R is a 191-item parent-report measure of infant temperament and behavior across domains that was administered at both 6 and 12 months of age. The IBQ-R response options range from 1 (never) to 7 (always) or “not applicable,” and parents rate their infant’s behavior within the two weeks prior to data collection. We focused on two sensory subscales, hypo- and hyperreactivity. Items on the hyporeactivity subscale (comprised of original Perceptual Sensitivity items, reverse scored) focus on the frequency with which the infant notices stimuli in the environment, such as a telephone ringing or a bird or squirrel in a tree. Items on the hyperreactivity subscale include difficulty falling asleep and fussing during grooming activities. Scores for hypo- and hyperreactivity were calculated as a mean for those who provided responses to ≥80% of the items (n = 204 for hyporeactivity; n = 252 for hyperreactivity); responses with <80% completion on a given subscale were considered missing data for that subscale. Items on which respondents marked “not applicable” were the primary reason for missing data.

Maternal sensitivity and intrusiveness

Maternal behavior was measured at 6 and 12 months of infant age using the NICHD SECCYD Mother–Child Interaction protocol (NICHD, 1999), which involves behavioral coding of 10–15 minutes of video-recorded free play with age-appropriate toys. Maternal sensitivity to nondistress and maternal intrusiveness were scored separately on scales ranging from 1 (not at all characteristic of a sensitive or intrusive mother, respectively) to 4 (highly characteristic of a sensitive or intrusive mother, respectively). Maternal sensitivity describes the degree to which the mother appropriately and contingently responds to the child’s social cues, and intrusiveness refers to behavior that imposes the parent’s will on the child when the child is signaling a different need or desire (NICHD, 1992). Raters included trained undergraduate psychology students and post-baccalaureate research coordinators. Inter-rater reliability was established at 90% agreement for sensitivity and 87% agreement for intrusiveness (Glynn et al., Reference Glynn, Davis, Sandman and Goldberg2016). Two-way, mixed effects, absolute agreement intra-class correlation coefficients were 0.74 and 0.83 at six and 12 months, respectively, for intrusiveness and 0.90 and 0.84 at six and 12 months for sensitivity. During rater training and inter-rater reliability analyses, absolute agreement was defined as primary and reliability scores within 0.5 of one another, a standard which has been shown to yield results that are adequately predictive of expected outcomes (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Stout, Molet, Vegetabile, Glynn, Sandman, Heins, Stern and Baram2017; Grande et al., Reference Grande, Swales, Sandman, Glynn and Davis2021).

Sociodemographic and biological characteristics

Maternal race, ethnicity, and education data were collected via maternal interview during gestation. Income-to-needs ratio was calculated from income data at infant age 12 months if available and substituted from infant age 6 months if 12-month data were unavailable (n = 1). Infant birthweight and sex were collected from medical chart review, and infant race and ethnicity were collected postnatally via maternal interview.

Data analyses

Cohorts from both parent studies were combined to maximize statistical power in all analyses. Descriptive information and bivariate correlations among variables of interest were calculated using IBM SPSS version 28.0. We conducted independent samples t-tests to determine the presence or absence of sex differences in maternal sensitivity/intrusiveness and infant sensory reactivity.

All other analyses were completed using the lavaan package in R (R Core Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012; Team, 2021) and followed procedures detailed in Mackinnon and colleagues (Reference Mackinnon, Curtis and OConnor2022). First, we completed invariance testing across time via increasingly restrictive (i.e., requiring fewer parameters to be estimated) confirmatory factor analyses for the infant hypo- and hyperreactivity subscales to select an appropriate factor model to ensure measurement invariance across waves of data collection. Invariance models tested included configural (factor loadings, item intercepts, and error vary over waves), metric (factor loadings constrained to equality across waves), scalar (factor loadings and intercepts constrained to equality across waves), and residual (variance, factor loadings, intercepts, and error constrained to equality across waves). Based on a χ2 test of difference between models, the metric model demonstrated the best balance of parsimony and model fit for both subscales. Invariance testing was not conducted for maternal sensitivity and intrusiveness, as latent variable models are not appropriate for single-item measurement tools.

To examine reciprocal influences of maternal and infant behavior over time, we next fit four cross-lagged panel models (CLPMs) with full information maximum likelihood estimation, which allow for understanding of the longitudinal associations between variables while controlling for cross-sectional associations and prior levels of the outcome variable. CLPMs are path models that combine regression analyses to predict multiple dependent variables by assessing the directional influence between variables at different timepoints (X[time 1] → Y[time 2] versus Y[time 1] → X[time 2]). Dependent variables are estimated based on autoregressive (e.g., infant hyporeactivity at 12 months predicted by infant hyporeactivity at 6 months) and cross-lagged (e.g., maternal sensitivity at 12 months predicted by infant hyporeactivity at 12 months) pathways. We were unable to fit Random Intercepts-CLPM, which are considered more robust than CLPM (Lucas, Reference Lucas2023), due to the requirement of three waves of data for such models. To explore the differing effects of each of these dimensions of infant and maternal behavior, separate CLPMs were examined for each combination of infant sensory hypo- and hyperreactivity, maternal sensitivity, and maternal intrusiveness. Model fit was assessed using Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; ≤0.06 indicates adequate fit); Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR; ≤0.08 indicates adequate fit); Comparative Fit Index (CFI; ≥0.9 indicates adequate fit); and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI; ≥0.9 indicates adequate fit). All models neared criteria for adequate fit across indices (see Supplement B), though none met traditional cutoffs for good fit. Standardized model estimates are reported.

Results

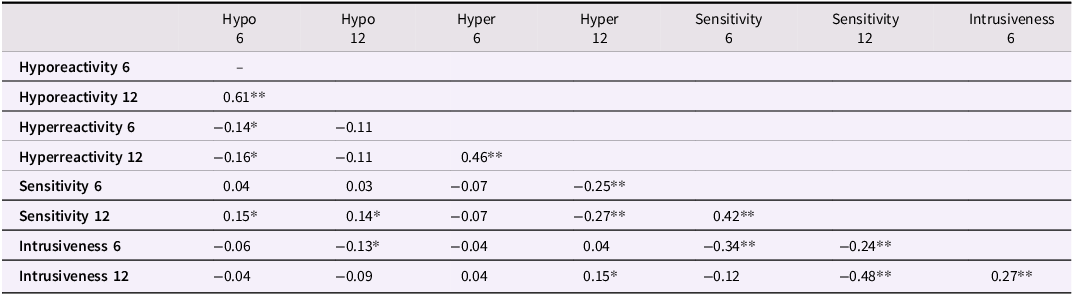

There were no statistically significant sex differences in infant sensory reactivity nor maternal sensitivity/intrusiveness with the exception of boys demonstrating higher sensory hyperreactivity than girls at 12 months (t = 2.05, p = .04). Refer to Supplement C for models tested separately by sex. The 6- and 12-month hypo- and hyperreactivity scores were moderately correlated (hyperreactivity r = .46; hyporeactivity r = .56). Additionally, concurrent and longitudinal measures of maternal sensitivity and intrusiveness were inversely related (r = −.24 to −.48). Associations between infant hyper- and hyporeactivity were near-zero concurrently and across time. Refer to Table 2 for the full correlation matrix. Demographic variables were largely unrelated to the variables of interest, with the exception of income-to-needs ratio (See supplemental table B.1).

Table 2. Bivariate correlations between aspects of infant sensory reactivity and maternal sensitivity

Hypo = hyporeactivity; Hyper = hyperreactivity.

*p < .05; **p < .001.

Reciprocal influences of maternal and infant behavior

Hyperreactivity

Broadly, these models indicated that maternal behavior shapes infant hyperreactivity over time. Specifically, maternal sensitivity at 6 months predicted lower infant hyperreactivity at 12 months (β = −.21; p = .002), while intrusiveness at 6 months predicted higher hyperreactivity at 12 months (β = .13; p = .08). Similarly, maternal sensitivity at 12 months was inversely associated with concurrent infant hyperreactivity (ψ = –.23; p = .002), and maternal intrusiveness at 12 months was positively associated with concurrent infant hyperreactivity (ψ = .20; p = .009). Infant hyperreactivity was not a predictor of maternal behavior, as indicated by near-zero cross-lagged effects between 6-month infant hyperreactivity and 12-month maternal sensitivity and intrusiveness. See Figure 1 for path modeling of autoregressive and cross-lagged effects.

Figure 1. Path models of autoregressive and cross-lagged associations between infant hyperreactivity and (a) maternal sensitivity and (b) maternal intrusiveness from infant age 6 to 12 months. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. Note. The full diagrams, including the metric factor model for infant hyperreactivity, can be found in Supplement B.

Hyporeactivity

The hyporeactivity analyses revealed that the direction of influence (mother to infant versus infant to mother) differed between maternal sensitivity and intrusiveness. Infant hyporeactivity at 6 months predicted higher sensitivity at 12 months (β = .09; p = .01). However, elevated maternal intrusiveness scores at 6 months predicted less infant sensory hyporeactivity at 12 months (β = –.32; p = .04). No concurrent associations between infant hyporeactivity and either aspect of maternal behavior were observed. Refer to Figure 2 for path modeling of autoregressive and cross-lagged associations between infant sensory hyporeactivity and maternal sensitivity and intrusiveness across infant ages 6 to 12 months.

Figure 2. Path models of autoregressive and cross-lagged associations between infant sensory hyporeactivity and (a) maternal sensitivity and (b) maternal intrusiveness from infant age 6 to 12 months. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. Note. The full diagrams, including the metric factor model for infant hyporeactivity, can be found in Supplement B.

Discussion

The present study provides initial proof-of-concept for the reciprocal, longitudinal effects of infant sensory reactivity and maternal behavior and suggests that sensory reactivity may be an important target for further exploration to support healthy development of maternal-infant relationships. Results demonstrate that mothers and children are shaping each other’s behavior in these domains, adding to the body of evidence that suggests similarly transactional interactions in other areas of development, such as social communication and attachment (Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Hendricks, Haynes and Painter2007; Mills-Koonce et al., Reference Mills-Koonce, Gariépy, Propper, Sutton, Calkins, Moore and Cox2007; Murray et al., Reference Murray, De Pascalis, Bozicevic, Hawkins, Sclafani and Ferrari2016; Murray & Trevarthen, Reference Murray and Trevarthen2008). Additionally, this study highlights the importance of understanding sensory reactivity and its impact, even in typically developing infants.

Sensory hyperreactivity and maternal behavior

Due to the proof-of-concept nature of this study and measurement limitations inherent in utilizing extant data for novel investigations, it is important to acknowledge that there are several potential alternative interpretations of the results. The analysis of hyperreactivity results must be foregrounded with the knowledge that fussiness and sleep problems were the primary constructs included in the hyperreactivity subscale, as many of the IBQ-R items therein are related to these behaviors. However, in a subset of the sample, parent-reported duration of crying and fussing as well as number of night wakings are only moderately correlated with the hyperreactivity subscale scores, suggesting that the subscale captures different information than simply crying and sleep behavior. It is important to consider the pattern of results in light of these possible alternative interpretations.

The results of this study illustrate the role of maternal sensitivity as a resilience factor and intrusiveness as a risk factor in the development of sensory hyperreactivity (and related constructs, such as sleep problems and fussiness). Because sensory hyperreactivity is characterized by a lower threshold for aversive or defensive responses (Baranek et al., Reference Baranek, Reinhartsen and Wannamaker2001; Campi et al., Reference Campi, Choi, Chen, Holland, Bristol, Sideris, Crais, Watson and Baranek2024), it is possible that the negative emotional valence involved in sensory hyperreactivity could explain our findings that mothers’ sensitivity to their infant’s cues supports a reduction in hyperreactivity over time. This may be because parents with high sensitivity are able to recognize their child’s early signs of aversion or defensiveness to sensory stimulation and respond by providing regulatory strategies or reducing the intensity of the aversive stimulus. In this way, infants with early signs of sensory hyperreactivity may have more opportunities to engage with aversive stimuli in manageable ways, leading to a wider repertoire of coping strategies and a higher aversion threshold over time. Additionally, high intrusiveness predicted elevated hyperreactivity over time. Because intrusiveness often involves increasing or unexpected sensory input, such as the parent physically taking control of the interaction or providing overwhelming stimuli (Ainsworth, Reference Ainsworth1979; Ispa et al., Reference Ispa, Fine, Halgunseth, Harper, Robinson, Boyce, Brooks-Gunn and Brady-Smith2004), young children with sensory hyperreactivity may be especially susceptible to its negative effects. Previous research suggests that low maternal sensitivity and high intrusiveness are concurrently and longitudinally associated with elevated infant fear responses and negative affect (Braungart-Rieker et al., Reference Braungart-Rieker, Hill-Soderlund and Karrass2010; Gartstein et al., Reference Gartstein, Prokasky, Bell, Calkins, Bridgett, Braungart-Rieker and Seamon2017; Grant et al., Reference Grant, McMahon, Reilly and Austin2010; Jonas et al., Reference Jonas, Atkinson, Steiner, Meaney, Wazana and Fleming2015; Pauli-Pott et al., Reference Pauli–Pott, Mertesacker and Beckmann2004; Tsotsi et al., Reference Tsotsi, Borelli, Abdulla, Tan, Sim, Sanmugam and Rifkin-Graboi2020; Wu & Gazelle, Reference Wu and Gazelle2021), which are among the behavioral manifestations of sensory hyperreactivity (DeGangi & Laurie, Reference DeGangi and Laurie1991; Narvekar et al., Reference Narvekar, Carter Leno, Pasco, Begum Ali, Johnson, Charman and Taylor2024), thereby lending support to our findings.

Sensory hyporeactivity and maternal behavior

Many of the IBQ-R items included on the hyporeactivity subscale ask parents to report how often their child notices stimuli in the environment. Because the term “notice” has several possible interpretations (e.g., notices by startling or crying, notices by turning to look, noticing even the most subtle stimuli that most people would ignore), parents may have been reporting on behaviors that would actually be consistent with hyperreactivity, such as aversive responses to mild stimuli, or other forms of atypical sensory reactivity. Furthermore, the hyporeactivity subscale was a reverse-scored version of the original IBQ-R Perceptual Sensitivity subscale, which was intended to measure a high degree of noticing subtle stimuli in the environment (Gartstein & Rothbart, Reference Gartstein and Rothbart2003). The reverse, that is, never noticing subtle stimuli in the environment, is consistent with our conceptualization of sensory hyporeactivity. If the Perceptual Sensitivity subscale had been analyzed as-is, that is, without reversal, results may have shown that elevated infant perceptual sensitivity would be associated with lower later maternal sensitivity and that higher maternal intrusiveness would have been associated with greater later infant perceptual sensitivity. Interpreting results this way would suggest that infants who notice more about their environment influence mothers to respond less sensitively over time, and that mothers who provide intrusive, unpleasant stimulation influence their infants to be more sensitive to environmental stimuli over time.

This study was a novel examination of sensory hyporeactivity and maternal behavior longitudinally in a community sample. In this cohort, infant hyporeactivity yielded higher maternal sensitivity over time. This may reflect that parents begin to recognize over time that their child requires a higher intensity of stimulus to engage due to an elevated orienting threshold. One explanation for this phenomenon could be that, while cues related to hyporeactivity (e.g., lack of orienting behavior) are quite subtle, over time, parents become especially attuned to their children to facilitate successful interaction. Additionally, previous research suggests that maternal sensitivity remains moderately stable across infancy and toddlerhood (Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Vaccaro, Kubinec, Moss, Avila-Rieger, Lowe and Tofighi2022; Holmberg et al., Reference Holmberg, Kataja, Davis, Pajulo, Nolvi, Hakanen, Karlsson, Karlsson and Korja2022; Joosen et al., Reference Joosen, Mesman, Bakermans-Kranenburg and van Ijzendoorn2012; Kemppinen et al., Reference Kemppinen, Kumpulainen, Raita-Hasu, Moilanen and Ebeling2006; Kopystynska et al., Reference Kopystynska, Spinrad, Seay and Eisenberg2016). The results of the present study offer one potential contribution of the infant to change that occurs in maternal behavior over time.

Interestingly, maternal intrusiveness, which is often characterized as a risk factor for maladaptive behavior and emotion dysregulation (e.g., Diemer et al., Reference Diemer, Treviño and Gerstein2021; Egeland et al., Reference Egeland, Pianta and O’brien1993), led to reduced severity of sensory hyporeactivity in the present study. According to the Optimal Engagement Band model (Baranek et al., Reference Baranek, Reinhartsen and Wannamaker2001; Campi et al., Reference Campi, Choi, Chen, Holland, Bristol, Sideris, Crais, Watson and Baranek2024), sensory hyporeactivity results from an elevated orienting threshold, such that an individual demonstrating this pattern requires higher-intensity stimuli to register and respond. Maternal intrusiveness may provide an overall higher intensity of sensory stimuli related to the social interaction, thereby allowing infants with hyporeactivity to engage with their parents, such that any registration of sensory input may support development more than a lack of registration. This potentially supportive role of intrusive behavior highlights the importance of matching interactive strategies to the infant’s needs and developmental status.

Strengths and limitations

The primary strengths of this study lie in its novelty, longitudinal nature, and contributions to our understanding of the development of both maternal sensitivity and infant sensory reactivity. Prior to the present study, associations between infant sensory reactivity and maternal sensitivity had not been examined in a community sample of infants not selected based on risk for a later diagnosis, despite the 11%–12% prevalence of sensory processing problems in otherwise typically developing children (Bar-Shalita et al., Reference Bar-Shalita and Cermak2016; Ben-Sasson et al., Reference Ben-Sasson, Carter and Briggs-Gowan2009; Ringold et al., Reference Ringold, McGuire, Jayashankar, Kilroy, Butera, Harrison, Cermak and Aziz-Zadeh2022; Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Shepherd and Lane2008). Thus, this study is a first step toward recognizing the early impact and development of sensory reactivity in terms of parent–infant interaction. The longitudinal nature of the present study allowed modeling of these reciprocal influences of maternal and infant behavior over time, thereby providing further evidence for the reciprocal nature of parent and infant development across domains (Bigelow et al., Reference Bigelow, Beebe, Power, Stafford, Ewing, Egleson and Kaminer2018; Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Hendricks, Haynes and Painter2007; Fantasia et al., Reference Fantasia, Galbusera, Reck and Fasulo2019; Feldman, Reference Feldman2007; Mills-Koonce et al., Reference Mills-Koonce, Gariépy, Propper, Sutton, Calkins, Moore and Cox2007; Murray et al., Reference Murray, De Pascalis, Bozicevic, Hawkins, Sclafani and Ferrari2016; Murray & Trevarthen, Reference Murray and Trevarthen2008; Wu, Reference Wu2021).

The extant nature of the data used for the present investigation yielded substantial measurement limitations that yielded several potential interpretations of the results, as discussed in the sensory hypo- and hyperreactivity sections above. The present study did not use gold-standard measurement of sensory reactivity, so future studies should use in-depth, multi-informant measures that include sensory seeking to more comprehensively capture infant sensory reactivity profiles. Additionally, the factor models underlying the derived measurement of sensory reactivity demonstrated suboptimal model fit, so results must be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, the prevalence of neurodevelopmental conditions related to sensory reactivity, such as autism and ADHD, was only known for part of the sample. The presence of the early signs of these conditions in infants may also contribute to variability in associations between maternal behavior and infant sensory reactivity. Future research should also examine associations between unpredictability of maternal sensory signals and development of sensory hypo- and hyperreactivity in infants.

Conclusion and implications

This study provides the first evidence of the reciprocal nature of maternal sensitivity and behavior related to infant sensory reactivity in infants unselected for neurodevelopmental conditions. These findings underscore the importance of attending to sensory reactivity early in life, even for otherwise typically developing infants, because of its role in shaping maternal behavior that underlies much of healthy infant development. Furthermore, these findings provide evidence for the utility of precision in determining parenting recommendations that best fit the specific infant’s needs and developmental profile.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579425101090.

Data availability statement

The data used for this research is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to each family who participated in the studies that comprised the sample for this work.

Funding statement

This research was funded by National Institutes of Health (CAS, LMG, EPD: P50 MH096889; CAS: NS28192) and the California Initiative to Advance Precision Medicine (LMG).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Pre-registration statement

This study was completed using extant data; therefore, it was not pre-registered.

AI statement

AI was not used in the preparation of any portion of this work.