Introduction

The advent of climate change has brought to the fore the impact of extreme weather on social, economic and political processes. Yet our understanding of how such events affect elections remains limited. This paper assesses the impact of flooding on electoral outcomes in Britain during a period, 2010–2019, when key aspects of UK politics remained institutionally stable, but there was variation across both space and time in the extent of flooding, as well as the attention accorded by the major political parties to environmental issues.

Using a difference-in-differences approach, I find that the partisan effect of flooding changed over time. These results support the theoretical expectation that the impact of flooding should be driven by the political context, and they call into question the adequacy of alternative potential explanations such as blind retrospection and rally-round-the-leader effects, which predict consistent anti-incumbent or pro-incumbent effects.

The United Kingdom is a good context in which to test the political effects of floods, which are expected to increase as the climate changes. Legislative accountability has long had a strong territorial component in the United Kingdom. With parliamentary constituencies approximately a tenth the size of US Congressional districts, UK Members of Parliament can find that extreme weather events affect large numbers of their constituents, and unlike in the proportional representation systems that dominate the world's democracies, responsiveness to territorially defined constituents is a core component of British understandings of representation. Moreover, the 2010–2019 period considered here was an unusual one where the same party led the government for three successive elections and constituency boundaries remained unchanged. This institutional stability facilitates the identification of links between flooding and election support.

The paper makes three main contributions. First, it helps refine our understanding of the impact of extreme weather on politics in general, and electoral outcomes in particular. Second, it calls into question the adequacy of two of the most prominent accounts of the electoral effects of natural disasters – the blind retrospection and rally-round the leader explanations – and suggests that additional theories are needed that take account of varying partisan effects over time. Third, it builds on studies that examine political and policy aspects of natural disaster effects (Baccini & Leemann, Reference Baccini and Leemann2021; Bechtel & Mannino, Reference Bechtel and Mannino2020, Reference Bechtel and Mannino2021; Blankenship et al., Reference Blankenship, Kennedy, Urpelainen and Yan2021; Fair et al., Reference Fair, Kuhn, Malhotra and Shapiro2017; Malhotra & Kuo, Reference Malhotra and Kuo2008) to develop a theoretical account of the impact of flooding on electoral outcomes based on political context, and it provides evidence that is consistent with that account.

Theoretical perspectives on flooding and electoral support

Although electoral outcomes in democracies tend to be driven by party placement on left-right issues (O'Grady & Abou-Chadi, Reference O'Grady and Abou-Chadi2019), recent evidence indicates that in some contexts climatic phenomena can modulate electoral results. Research on weather and elections has largely focused on the impact of ‘normal’ climatic variations such as rain, which has been found to exert transient effects on mood that have political consequences (e.g. Artés, Reference Artés2014; Gomez et al., Reference Gomez, Hansford and Krause2007; Horiuchi & Kang, Reference Horiuchi and Kang2018; Leslie & Arş, Reference Leslie and Arş2018). The effect of flooding can be expected to be of a different order, however, as it disrupts social and economic life in the areas affected far more profoundly than is the case with a passing rainstorm. Some studies have sought but failed to find any significant impact of flooding on electoral results (Bovan et al., Reference Bovan, Banai and Banai2018; Potluka & Slavíková, Reference Potluka and Slavíková2010). Yet a number of analyses have found effects, and previous research suggests two principal approaches to understanding how flooding might condition vote choice, one based on blind retrospection and a second based on rally-round-the-leader response. I also propose a third previously under-explored causal channel based on political context, and in particular party positions and voter perceptions of how 'strong' parties are on flooding.

Blind retrospection: Achen and Bartels (Reference Achen and Bartels2016) have provided evidence that many voters engage in ‘blind retrospection’, in the sense that they blame leaders for shark attacks, droughts, floods and other unwelcome phenomena that are clearly outside leaders' control. In other words, voters use their experience over the previous electoral term as a heuristic for assessing political performance, rather than undertaking more laborious attempts at attributing causal efficacy to public policy. The theory of blind retrospection has been deployed by a number of scholars to study the impact of natural disasters on voting behaviour (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Healy and Werker2012; Gasper & Reeves, Reference Gasper and Reeves2011; Heersink et al., Reference Heersink, Peterson and Jenkins2017). If this theory is valid in the UK context, we ought to observe an association between flooding and voting against the incumbent; given that the same party held power in the United Kingdom at each of the elections examined here, this translates into an expectation that flooding should be linked to a reduction in vote share for the Conservatives.

Rally-round-the-leader effects: An increase in incumbent support has often been observed when a country goes to war (e.g. Baker & Oneal, Reference Baker and Oneal2001; Boittin et al., Reference Boittin, Mo and Utych2020; Kam & Ramos, Reference Kam and Ramos2008). Like wars, natural disasters could make voters rally round the incumbent. There is some research that supports this theory in relation to natural disasters such as wildfires and earthquakes (Boittin et al., Reference Boittin, Mo and Utych2020; Lazarev et al., Reference Lazarev, Sobolev, Soboleva and Sokolov2014; Ramos & Sanz, Reference Ramos and Sanz2020). If floods generated a rally effect in the United Kingdom between 2010 and 2019, the Conservatives ought to have been the most likely recipients of the votes of those conditioned by this effect, which leads us to predict an increase in Conservative vote share.

Party positions: I offer here an additional plausible theoretical account of the impact of flooding on electoral support. This starts with the observation that most existing theories of the impact of extreme weather on electoral outcomes focus on the voter, rather than the party. Some scholars have found that instead of, or in addition to, the ‘blind retrospection’ effect, voters are also attentive to state preparation for (Arceneaux & Stein, Reference Arceneaux and Stein2006; Ashworth et al., Reference Ashworth, Bueno de Mesquita and Friedenburg2017) and response to (Bechtel & Hainmueller, Reference Bechtel and Hainmueller2011; Gasper & Reeves, Reference Gasper and Reeves2011; Fair et al., Reference Fair, Kuhn, Malhotra and Shapiro2017; Healy & Malhotra, Reference Healy and Malhotra2009, Reference Healy and Malhotra2010; Lazarev et al., Reference Lazarev, Sobolev, Soboleva and Sokolov2014) disasters. There is some evidence that voter attributions of blame may be skewed by partisan affiliation and susceptible to partisan cues (Malhotra & Kuo, Reference Malhotra and Kuo2008). The stress of a major flood may make voters reward the party in power for disaster relief, as has been found in several previous studies (Bechtel & Hainmueller, Reference Bechtel and Hainmueller2011; Cole et al., Reference Cole, Healy and Werker2012; Gasper & Reeves, Reference Gasper and Reeves2011; Healy & Malhotra, Reference Healy and Malhotra2009; Lazarev et al., Reference Lazarev, Sobolev, Soboleva and Sokolov2014). Sometimes this effect works to counter the effects of blind retrospection (Blankenship et al., Reference Blankenship, Kennedy, Urpelainen and Yan2021; Cole et al., Reference Cole, Healy and Werker2012; Gasper & Reeves, Reference Gasper and Reeves2011). There is evidence that these effects may be in part conditioned by voter assessments of policy response and perceptions of policy options (Baccini & Leemann, Reference Baccini and Leemann2021; Bechtel & Mannino, Reference Bechtel and Mannino2020, Reference Bechtel and Mannino2021), both of which can be shaped by elite behaviour and elite cues.

Storm-related damage would appear at first blush to be a consummate valence issue – no one wants a flood. However, parties frame flooding in different ways and prioritize flood prevention to different degrees. Specifically, flooding may be linked by some parties to climate change, which may prime voters to evaluate flooding through a different lens and react differently to it. Kam and Ramos note that rally-round-the-leader effects can over time give way to partisan interpretations of events and political reactions to those events which reinforce partisan loyalties and thus work to erode initial rally responses (Kam & Ramos, Reference Kam and Ramos2008). There may in some contexts be costs to pro-environmental policy stances (Gagliarducci et al., Reference Gagliarducci, Paserman and Patacchini2019), but generally-speaking, parties that are seen to be 'strong' on the environment ought in theory to benefit from increased vote share in the wake of flooding. The extent to which different parties are able to position themselves as being strong on the environment in general, and on flooding in particular, can thus be expected to be linked to the electoral impacts of flooding; electors who have experienced floods should, all else equal, be more likely to cast their votes for the party that they see as most capable in the area of environment and flooding. If flooding affects electoral outcomes, this effect ought therefore to be conditioned by party positions and voter perceptions of parties. The three perspectives discussed above suggest alternative hypotheses for how the experience of a flood might alter electoral support:

H1: Blind retrospection: The incumbent party's vote share will be depressed in flood-affected areas, to the benefit of that party's main challengers.

H2: Rally-round-the-leader: The incumbent party's vote share will be boosted in flood-affected areas, at the expense of that party's main challengers.

H3: Political context: At each election, parties that are perceived as strong on flooding and related issues perform better in flood-affected areas.

The research design and data presented in Sections 3– 5 describes how I arbitrate between these competing theories.

The British context

The environment has long played a role in UK electoral politics, and the main political parties – the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats – have all espoused measures to prevent environmental destruction, though with varying degrees of intensity and policy radicalism at different points in time.Footnote 1 The economic downturn of 2008 focused policy attention on the economy, and between 2015 and 2019, the United Kingdom was engulfed in a national debate about its future relationship with the European Union. However, concerns about environmental destruction in general, and flooding in particular, continued to grow as the scientific evidence mounted of the risk that climate change poses to the United Kingdom. Climate models predict an increase in strong storms, wet winters and sea-level rise (Met Office, 2019), all phenomena that are likely to lead to an elevated incidence of flooding, which is predicted to increase 20-fold by 2080 (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Sayers and Dawson2005). An estimated 2.8 million properties in the United Kingdom are at risk of flooding, and 690,000 are at severe risk (Beltrán et al., Reference Beltrán, Maddison and Elliott2019).

The impact of flooding on electoral outcomes has not, to my knowledge, been studied in the UK context. Existing research on the impact of floods indicates that the UK public does not typically blame the government for inundations, partly because the media tend to exhibit the rally effect (Wood, Reference Wood2016). Whitmarsh tests for and fail to find an effect of experience of flooding on climate change attitudes (Whitmarsh, Reference Whitmarsh2008), although there is evidence from the 2013-14 floods that this may be changing, and that flooding is increasingly linked in the minds of the British public to climate change (Demski et al., Reference Demski, Capstick, Pidgeon, Sposato and Spence2017). It also appears that the experience of flooding is associated with support for policies designed to mitigate climate change (Demski et al., Reference Demski, Capstick, Pidgeon, Sposato and Spence2017), and there is evidence of a recent shift in news journalism on floods from factual reporting to climate change blame attribution (Escobar-Tello & Demeritt, Reference Escobar-Tello and Demeritt2004; Saunders et al., Reference Saunders, Grasso and Hedges2018).

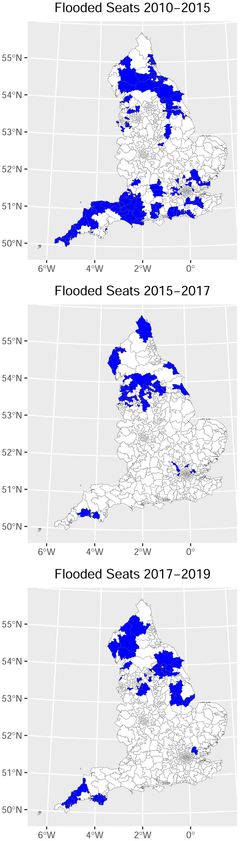

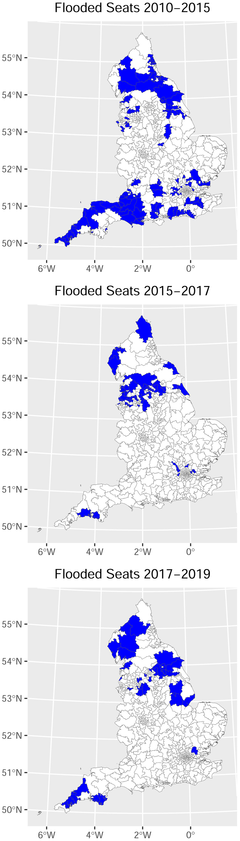

The north of England is particularly prone to flooding, and in all three periods considered here, relatively large numbers of northern constituencies experienced floods. Two of the elections held during this period followed unusually extensive flood events that affected large areas: the 2013–2014 floods that took place mainly in the south and the south-west of the country, and the floods that took place in the autumn of 2019 in the run-up to the December election of that year that affected mostly the north and the Midlands. The 2015–2017 period was one of more limited and less serious flooding overall. Figure 1 displays these trends, showing the distribution of parliamentary constituencies in each period that were affected by flooding.

Figure 1. Flooding by constituency, 2015, 2017 and 2019. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The United Kingdom relies mainly on private insurance to deliver flood relief, with the state generally only stepping in to support local communities in cases of very severe and widespread flooding (Escobar-Tello & Demeritt, Reference Escobar-Tello and Demeritt2004)Footnote 2; disaster performance assessments are thus less relevant in the UK context, as people rely so heavily on the private sector for disaster alleviation. At the same time, the national government is involved in flood defence measures and overall flood-related policy. The main policy engagement with flooding takes the form of proactive multi-year programmes of flood defence construction, rather than a reaction to specific food events. These flood defence programmes are implemented by the party or parties in government, and all major parties typically include flood defence commitments in their election manifestos. Even when retroactive government support is given where flooding is severe, the amount of money allocated in disaster relief pales in comparison to that spent on proactive flood defence measures, and flood relief funding is given to local authorities to disburse, rather than directly to individuals. It therefore makes sense to focus on national politics and the positions that political parties take on flooding and flood defence as an electoral issue. Previous studies have rarely been able to disentangle the effects of flooding and government intervention on flooding, as most such analyses have been carried out in contexts where flooding and flood relief occur virtually contemporaneously. The UK context, where government intervention mainly takes the form of preventative measures offers an opportunity to separate out flood effects per se and the effects of government action in this policy domain. A reasonable assumption is that voters will recall flooding, but if they recall also that the incumbent government is devoting resources to protecting their community from flooding, this may attenuate the extent to which the government is blamed for flooding; alternatively, the erection of defences may enhance the rally-round-the-leader effect. In both cases, flood defences are expected to moderate the impact of floods on electoral results in the United Kingdom.

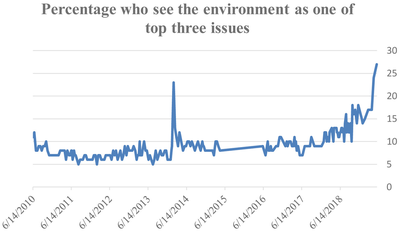

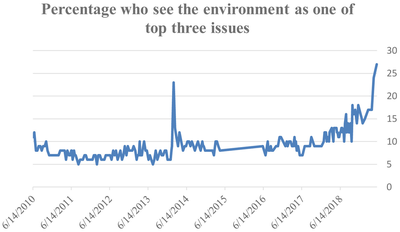

As an issue, flooding received limited coverage in the UK press during the decade prior to the start of this period (Gavin et al., Reference Gavin, Leonard-Milsom and Montgomery2011). There was then a noteworthy rise in overall concern about the environment between 2010 and 2019. YouGov tracker data show that at the beginning of the period, the proportion of people who told opinion pollsters that the environment was one of the top three issues facing the country was consistently in single digits, but by 2019 this had changed, with between a sixth and a quarter of Britons making this claim. There are also noteworthy spikes in environmental concern that coincide with major floods, providing further evidence of the link in the popular mind between flooding and environmental degradation (see Figure 2); these illustrative data are consistent with the findings of previous studies that have found flooding to increase environmental concern in the UK context (e.g. Demski et al., Reference Demski, Capstick, Pidgeon, Sposato and Spence2017; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Bland, Cookson, Kanaan and White2017; Ogunbode et al., Reference Ogunbode, Demski, Capstick and Sposato2019; Spence et al., Reference Spence, Poortinga, Butler and Pidgeon2011).

Figure 2. Percentage who see the environment as one of top three issues. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: YouGov.co.uk. The data in this graph are from the YouGov tracker asking people to identify three most important issues facing the country. The YouGov weekly tracker includes 1610–3326 adults per wave. The reported results are weighted to population demographic attributes (age, gender, social class, region and level of education) (YouGov, 2021).

By the 2019 election, 25 per cent of the electorate identified climate change as one of the three most important issues facing the country, despite the overwhelming dominance of Brexit as an issue at this time. Moreover, over two-thirds of the population at this point saw a link between the 2019–2020 floods and climate change (YouGov, 2020).

Of importance to the analysis undertaken here is the political parties' responses to these developments, as the party political context hypothesis focuses on the electoral returns to party positions. Over the course of the first two decades of the new century, environmental concerns, and in particular climate change, rose up the political agenda of all main UK parties. The first major party to pivot decisively towards green issues was the Conservatives. When he came to power in 2005, Conservative leader David Cameron sought to reposition the party as a defender of environmental causes. This move was part of his efforts to align the party with shifting public opinion (Carter, Reference Carter2009; O'Grady & Abou-Chadi, Reference O'Grady and Abou-Chadi2019). The Conservatives (colloquially known as ‘Tories') quite publicly made a move to capture the environment as an issue that had been relatively neglected by their main competitors and was therefore ‘unbranded’ (Carter, Reference Carter2009). Over the course of their subsequent three terms in office, the Tories de-prioritized environmental issues, reduced subsidies for renewable energy and zero-carbon home construction targets and abolished the Department for Energy and Climate Change. Yet the party nevertheless largely adhered to climate change targets that had been set by the previous Labour administration in the 2008 Climate Change Act. Outgoing prime minister Theresa May committed the government in June 2019 to a target of net-zero emissions by 2050, a pledge that was reaffirmed by her successor Boris Johnson.

The rise of a new leader was also instrumental in repositioning the Labour party on environmental issues a decade later. When Jeremy Corbyn assumed the leadership in 2015, Labour consciously sought to regain the support of voters who had defected to the Green party during Labour's centrist years (Quinn, Reference Quinn, Allen and Bartle2018), consistent with comparative evidence that parties are most likely to emphasize green issues when they represent vote-maximizing opportunities (Spoon et al., Reference Spoon, Hobolt and deVries2014). In the run-up to the 2017 General Election, Labour began a strategy of colonizing this terrain. This strategy paid off handsomely at the 2017 General Election, when an estimated 58 per cent of voters who had voted Green in 2015 opted for Labour (Bartle, Reference Bartle, Allen and Bartle2018), despite the fact that environmental issues did not feature prominently in the party's campaign (Carter & Farstad, Reference Carter and Farstad2017). By 2019, however, Labour had firmly cast itself as a proponent of radical policy measures designed to mitigate climate change (Carter & Pearson, Reference Carter and Pearson2020).

The Liberal Democrats have long been committed environmentalists, yet they have not always succeeded in conveying this component of their policy platform convincingly to the electorate (or implementing it when in government). The party also suffers from the fact that it is clearly not a viable electoral alternative in most places, and voters who are concerned with the environment have the option of voting for the even smaller Green party in most seats. The Liberal Democrats’ many pro-environmental pledges in 2017 did not appear to win them widespread recognition as the party that was strongest in this policy domain (Carter & Farstad, Reference Carter and Farstad2017), and by 2019 Labour had taken on green causes with gusto, leaving the Liberal Democrats to make their opposition to Brexit the main plank in their electoral platform.

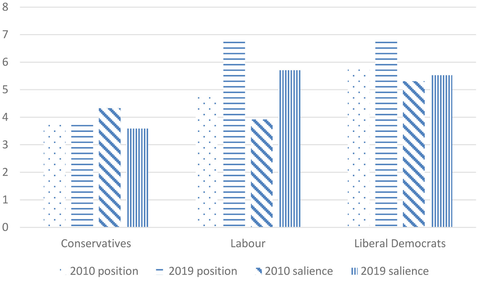

These shifts in position and salience are reflected in data from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey, which charted party stances on the environment in surveys carried out in 2010 and 2019 (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, de Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2020). Each expert survey measured both the position taken by parties and the emphasis the party accorded to environmental issues (Figure 3).Footnote 3

Figure 3. Party position and salience 2010–2019. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Data extracted from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File 1999–2019 (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, de Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2020). For the purpose of this graph, the party position scores have been inverted such that a higher score reflects a more pro-environmental stance.

These data confirm Labour's swerve to a more pro-environmental stance between the beginning and the end of the period under consideration here, as well as the reversal of salience of the environment as an issue between the two main parties; in 2010 it was the Conservatives who accorded green issues somewhat more importance than Labour, but by 2019 that had changed considerably, and Labour was viewed by the experts surveyed as placing far more emphasis on this issue than the Tories. The data also confirm that over the entire period, the Liberal Democrats were a strongly pro-environmental party, although by 2019 their environmental credentials had been somewhat eclipsed by Labour. A detailed review of political party manifestos included in Section 1 of the Supporting Information provides further fine-grained evidence to support these claims.

The analysis in this section has shown that over the course of the 2010–2019 period, environmental issues in general, and flooding in particular, rose up the political agenda and gained importance as issues of popular concern. The main political parties responded in different ways. The Conservatives maintained a commitment to spending on flood defences but were reluctant to make the link between flooding and climate change. Labour and the Liberal Democrats were eager to make this link, and if flooding and the environment were perennial concerns for the Liberal Democrats, they gained importance for Labour, especially in advance of the 2019 election. Coming back to the political competition hypothesis set out in the previous section, we would expect, in the UK context, that the Conservatives would benefit from flooding in the initial period and Labour subsequently. It is less clear what impact flooding should have on the vote share of the Liberal Democrats.

Data and approach

I note that my focus here is on aggregate electoral outcomes, not individual-level behaviour. Although individual-level data analysis would help in specifying causal mechanisms, surveys that include relevant questions have not been fielded in a sufficiently large number of constituencies for it to be possible to undertake individual-level investigation of this type at the current time. The analysis presented here emphasizes national-level attributes of parties – incumbency and policy emphasis – in keeping with the assumption that voting in the United Kingdom is driven largely by considerations of national-level party politics, and that the actions of individual candidates shape vote choice only to a very minor extent (Norton & Wood, Reference Norton and Wood1993). For this reason, the empirical models include constituencies in England only, given the distinct party systems of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and the analysis thus relies on aggregate-level data on flooding and major party vote share across English constituencies (though a robustness check based on voting for or against the local incumbent is described in the next section and presented in detail in the Supporting Information).

Between 2010 and 2019, the United Kingdom held four general elections, with early elections brought about in 2017 and 2019 due to the political convulsions surrounding the United Kingdom's decision in 2016 to leave the European Union. Over the course of a typical decade, the United Kingdom would normally undergo at least one overhaul of its parliamentary constituency boundaries by the independent Boundary Commission (Johnston, Reference Johnston2021). But following an attempt at boundary revision that was thwarted in 2012 by the Liberal Democrats as junior coalition partner, the parliamentary agenda was sufficiently congested that revised boundaries were not voted into law. This led to the highly unusual situation where four general elections were held under the same boundaries with the same party in power. This situation has the considerable advantage for the current analysis that it makes it possible to track flood events during three consecutive inter-electoral periods, and to compare electoral results across three points in time when the same party was in charge of policy-making at national level.

The approach adopted exploits this unusual period of continuity, employing a difference-in-differences (DID) identification strategy that captures the difference that flooding made to electoral results in those seats that were flooded, with separate analyses for each of the 2015, 2017 and 2019 General Elections. DID is implemented via the inclusion in panel models of unit and temporal fixed effects that control for unit-specific and time-specific unobservables (Angrist & Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2009; Imbens & Wooldridge, Reference Imbens and Wooldridge2009). Specifically, this approach estimates the difference between the mean party vote share in flooded constituencies and the observed counterfactual of what the mean vote share of that party would have been in those constituencies had no flooding occurred, in other words the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT), which is estimated by means of regressions that take the general form:

where Y

![]() $_{it}$ is the vote share for a given party in constituency i at time t,

$_{it}$ is the vote share for a given party in constituency i at time t,

![]() $\tau$ is the parameter of interest (the ATT), F

$\tau$ is the parameter of interest (the ATT), F

![]() $_{it}$ is an indicator of flooding in constituency i at time t,

$_{it}$ is an indicator of flooding in constituency i at time t,

![]() $\gamma$

$\gamma$

![]() $_i$ is a unit (constituency) fixed effect,

$_i$ is a unit (constituency) fixed effect,

![]() $\delta$

$\delta$

![]() $_t$ is an election year fixed effect, and X

$_t$ is an election year fixed effect, and X

![]() $_{it}$

$_{it}$

![]() $\beta$ is a vector of covariates that take account of potential differences in trends and

$\beta$ is a vector of covariates that take account of potential differences in trends and

![]() $\epsilon$

$\epsilon$

![]() $_{it}$ is an error term. Thus the approach controls for other potential factors specific to individual consistencies that might account for changes in electoral support, and also for inter-electoral variables that might result in common shifts in electoral support over time. Examining many flood events in different parts of the country at different points in the inter-electoral cycle is advantageous as it reduces the chances that idiosyncratic factors associated with a single event, or concomitant shocks resulting from the event, might drive the results, and it is therefore likely to yield more consistent estimates of average effects over time (Ramos & Sanz, Reference Ramos and Sanz2020).

$_{it}$ is an error term. Thus the approach controls for other potential factors specific to individual consistencies that might account for changes in electoral support, and also for inter-electoral variables that might result in common shifts in electoral support over time. Examining many flood events in different parts of the country at different points in the inter-electoral cycle is advantageous as it reduces the chances that idiosyncratic factors associated with a single event, or concomitant shocks resulting from the event, might drive the results, and it is therefore likely to yield more consistent estimates of average effects over time (Ramos & Sanz, Reference Ramos and Sanz2020).

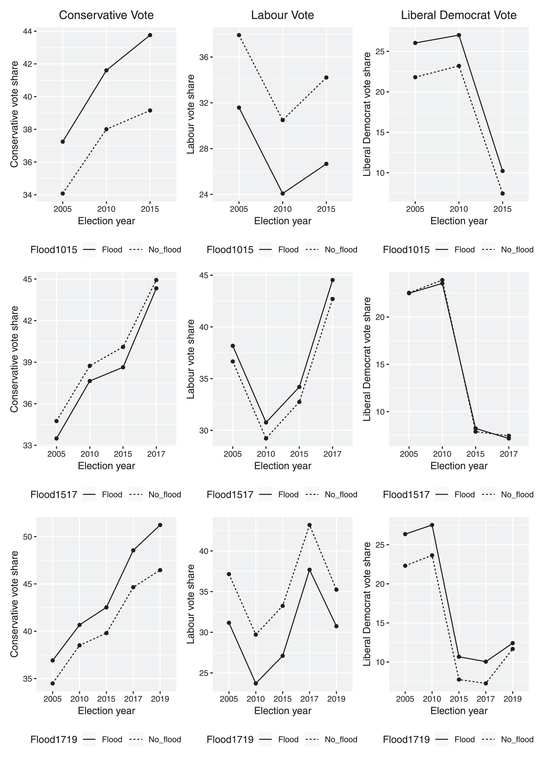

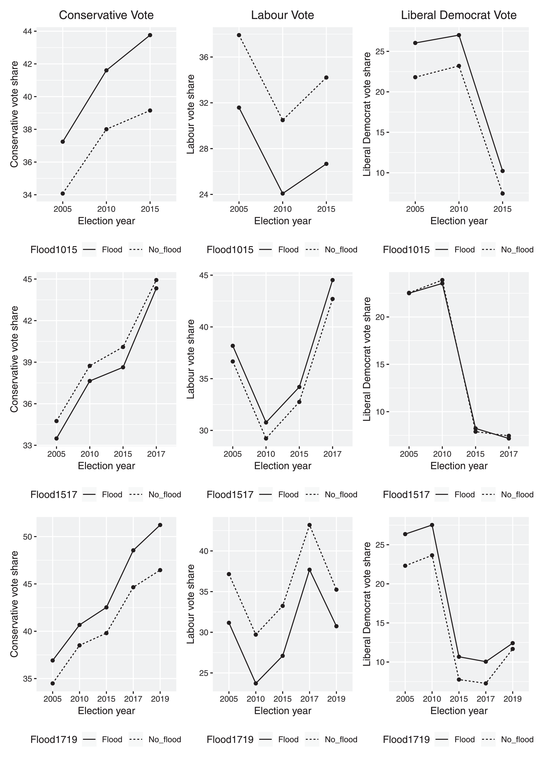

This approach relies on the parallel (common) trends identifying assumption: this is the assumption that changes in electoral support in areas flooded in any given inter-electoral period would not have differed systematically from changes in unflooded areas; in other words, we want to be sure that election results in flooded seats and unflooded seats had been varying in the same way from one election to the next, prior to the flood. Figure 4 plots the mean party vote share for each of the three inter-electoral periods plus previous periods (back to 2005) for flooded and non-flooded constituencies in the inter-electoral period in question. As can be seen from these graphs, the parallel trends assumption holds well in most of the nine cases (in the sense that seats that were flooded at any given point in time had previously been moving electorally in tandem with unflooded seats); the exceptions are the trends for the Conservative vote share in flooded and unflooded seats (the left-hand panels in Figure 4).

Figure 4. Analysis of the assumption of parallel trends in electoral results.

In each of these cases, there is a slight divergence in vote share in the period prior to flooding. Pretests (placebo tests) for each of the time periods examined here confirm that there was a marginally significant impact on Conservative voting in 2010 of flooding in the subsequent 2010–2015 period, suggesting a common factor linking areas prone to flooding and Conservative voting. Though this effect is only evident for the first period, the marginal significance of this effect warrants caution in assuming parallel trends (see Section 4 of the Supporting Information for full details of the pretests). For this reason, I present models that control for factors associated with regional differences. The pretest indicates that a summary variable for deprivation addresses the problem; this makes sense in as much as the northern areas where flooding most often occurs tend to be distinguished from the United Kingdom as a whole by higher levels of deprivation. These models are implemented in the analyses presented in the next section via Sant'Anna and Zhao's doubly-robust regression approach which provides a robust means of conditioning on covariates in DID models by combining inverse probability tilting (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Pinto and Egel2012) with a matching approach in a two-step modelling strategy that allows valid inferences to be drawn from regression outputs even in the face of some covariate misspecification (Sant'Anna & Zhao, Reference Sant'Anna and Zhao2020), thereby alleviating concerns about the inferential challenges posed by potentially heterogeneous treatment effects.

I dichotomize flooding to generate a binary indicator, a dummy variable where 1 corresponds to any recorded flood event having occurred in the relevant constituency during the inter-electoral period and 0 corresponds to the absence of any such event. I also present an alternative specification using an interval measure of flood intensity (the number of floods in an inter-electoral period).

Data on flood prevention measures are available for the 2015–2017 and 2017–2019 periods only. These data, which were supplied by the Environment Agency, take the form of annual counts of the number of homes protected by the Government's ‘Flood and Coastal Risk Management 6 Year Capital Programme 2015–2021’. Each March during the term of the programme, the Environment Agency compiles a count of homes protected during the preceding months by schemes underway or completed. The measure used is the sum of homes deemed to have been protected from flooding in each constituency over the inter-electoral period in question. For the 2015–2017 period, the March 2016 and March 2017 counts of homes protected were summed to provide a proxy for homes protected between the May 2015 and June 2017 General Elections. For the 2017–2019 period, the counts generated in March 2018, March 2019 and March 2020 were used for this purpose. These counts will admittedly provide only a rough proxy of flood protection activity in questions. However, for the purposes of the main analyses reported here, a binary version of this variable is employed, where a seat is coded 1 if any Flood and Coastal Risk management activity was undertaken during this period, and 0 if not. The intuition behind this approach is that voters are unlikely to be sensitive to the precise number of homes the Environment Agency deems to have been ‘protected’ during any given period; they are more likely to be attuned to whether or not the government is taking any measures to protect their constituency from flooding. The data are not granular enough to be able to determine whether a flood that occurred took place before or after completion of the flood defences. In any case, most of the flood defence projects are major infrastructure endeavours that take an extended period to complete and may therefore have been partially complete, and have afforded partial protection, at the time of specific floods. Details of data sources and variable construction are included in Section 2 of the Supporting Information; summary statistics for all variables can be found in Table A1 in the Supporting Information.

Results

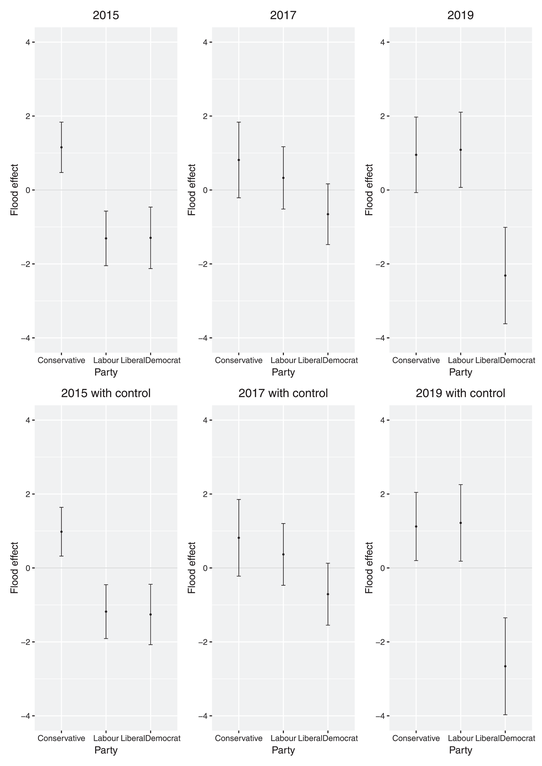

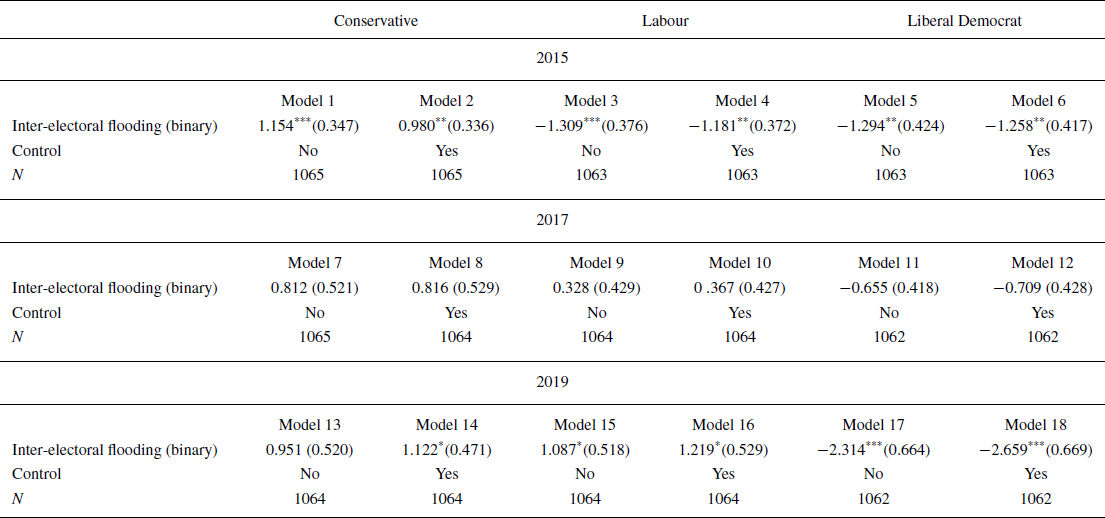

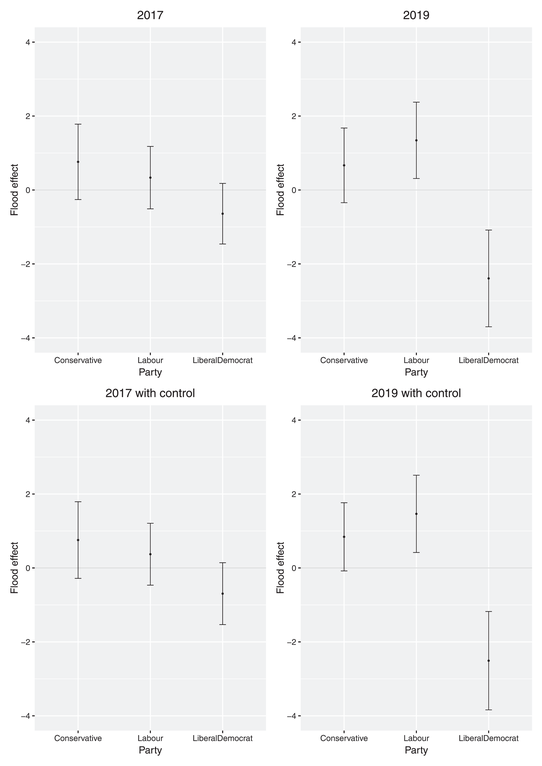

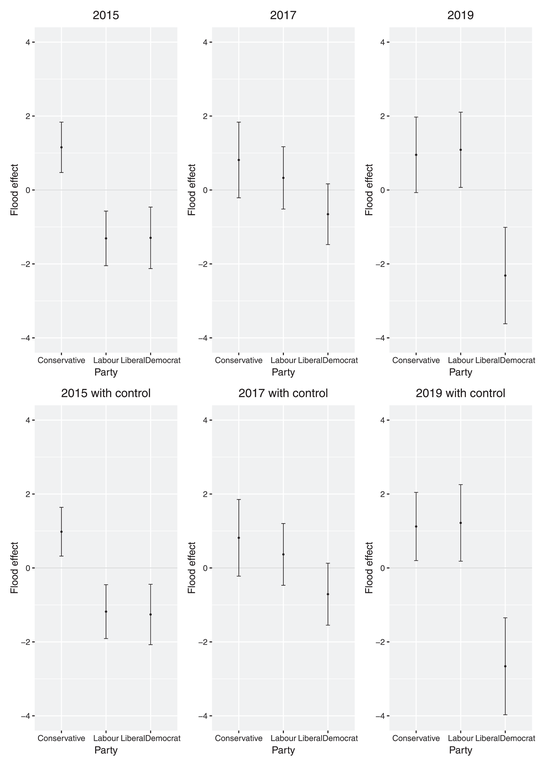

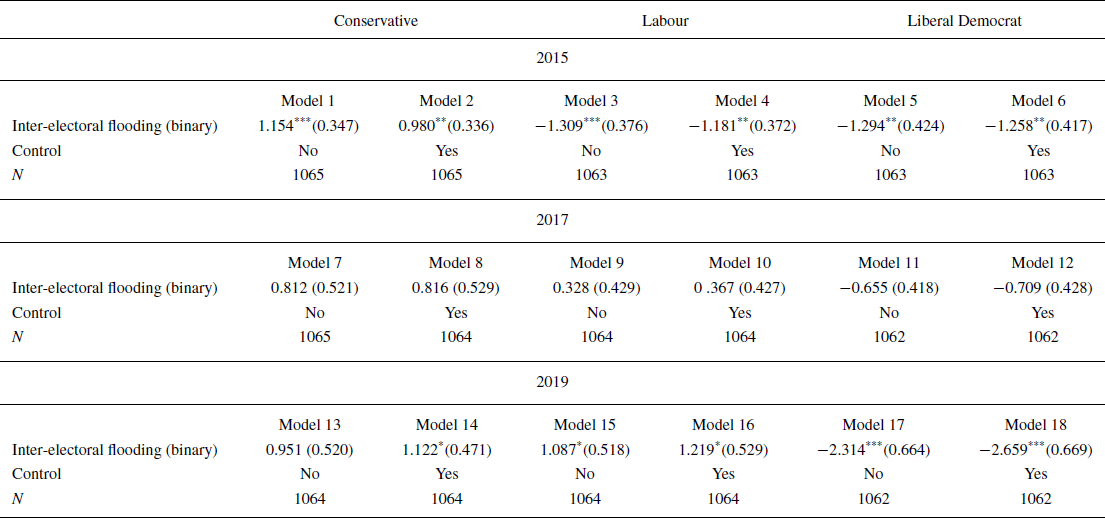

I start with analyses for each period for the main parties. The resulting regression models are presented in Table 1, and the estimated effects are plotted in Figure 5. These results indicate that in 2010–2015 following extensive flooding, the Conservatives (the dominant incumbent party) performed better in seats that had been flooded during the previous inter-electoral period (Model 1), whereas their main opponent, Labour, performed slightly worse in flooded constituencies (Model 3). Interestingly, the Liberal Democrats – the minority coalition party in the 2010–2015 period – also suffered electorally from flooding, all else equal (Model 5). These findings are consistent with both the rally-round-the-leader hypothesis, and the party position-taking hypothesis (given the Conservatives' recent efforts to ‘go green'), but not with the blind retrospection hypothesis. Models 2, 4 and 6 include a control for deprivation. The basic story remains the same: in 2015, floods appear to have helped the Conservative party electorally and hurt the other parties.

Figure 5. Models of the impact of flooding on election outcomes.

Table 1. Models of the impact of flooding on the general election results – binary floods variable

Note: These are doubly robust linear models (Sant'Anna & Zhao, Reference Sant'Anna and Zhao2020), with constituency and election fixed effects and with the outcome conditioned on a covariate for deprivation in the models indicated. Cell entries are coefficients (standard errors); *p

![]() $>$ 0.05; **p

$>$ 0.05; **p

![]() $>$ 0.01; ***p

$>$ 0.01; ***p

![]() $>$ 0.001.

$>$ 0.001.

In the 2015–2017 period, by contrast, flooding had no significant effect on the vote share of any party (with or without controlling for demographics). This stands to reason, given the paucity of major flood events during this period, and the relative lack of salience of flooding as an issue in this election.

In 2019, major flooding occurred during the election campaign, but unlike in 2015, both major parties won more votes in seats that had experienced flooding in the preceding period, all else equal, and the Liberal Democrats won fewer, as shown in Models 13–18 of Table 1. The effect on the Conservatives only reaches statistical significance with the inclusion of a demographic control, but the effect for the other two parties is evident in models with and without controls. These findings are again at odds with the blind retrospection hypothesis, but they lend some support to a combination of the rally-round-the-leader and the party position-taking hypotheses. The increased vote for Conservatives in flooded seats could be explained by a rally effect, but there must be something else going on as well to account for the increased Labour vote share in flooded seats. A pairwise test (Paternoster et al., Reference Paternoster, Brame, Mazerolle and Piquero1998) confirms that the difference between the flood coefficient in the 2015 Labour party model and that in the 2019 Labour party model is significant at the 0.001 level, whereas the relevant coefficients in the models for the other two parties are not significantly different. It is quite likely that as Labour shifted its electoral appeal in favour of green issues and the Conservatives devoted less attention to this issue, so Labour began to reap the electoral benefit of flooding.

A separate analysis considered how long these effects last; models of the impact of flooding that occurred between 2010 and 2015 on the 2017 and 2019 elections indicate that the ‘flood effect’ is relevant only at the election immediately following the flood event (see Table A3 in Section 5 of the Supporting Information). The only significant coefficient in these models is a weakly significant positive impact of 2010–2015 flooding on the Liberal Democrat vote in 2017, undoubtedly because this party's vote bounced back in previously flooded seats from the depressed vote it had experienced there in 2015.

Together these results suggest that the electoral impact of flooding was driven at least in part by factors specific to party politics, and in particular to the relative emphasis placed on different issues at different times by the main parties in British politics.

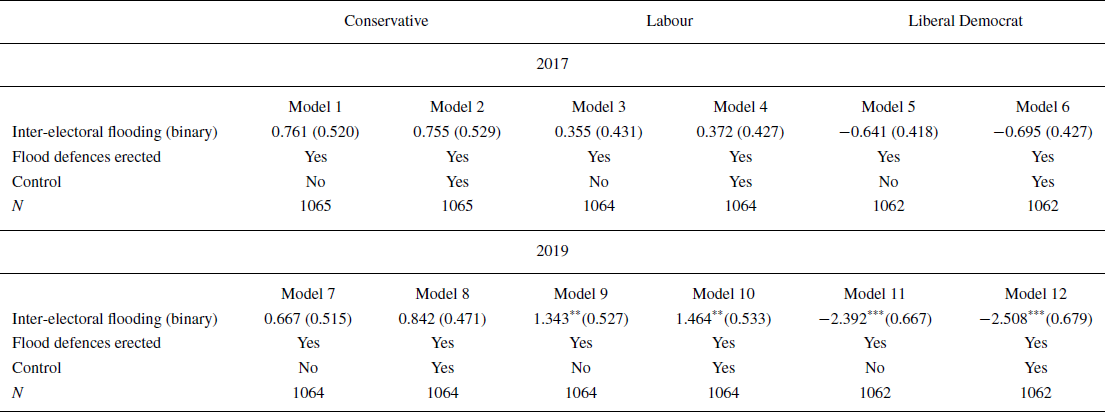

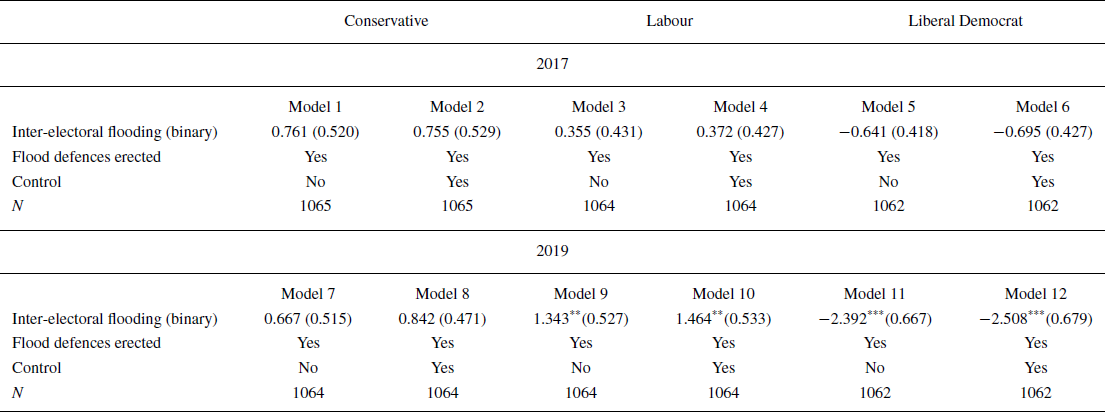

In a second stage of the analysis, I assess heterogeneous treatment effects by taking into consideration the construction of flood defences as a factor that might be expected to heighten or attenuate the impact of flooding on party support. The models in Table 2 include a binary variable indicating whether not any homes were designated by the Environment Agency as having been protected by the completion of flood defence works during the inter-election period in question.

Table 2. Models of the impact of flooding on the general election results with flood defences (homes protected)

Note: These are doubly robust linear models (Sant'Anna & Zhao, Reference Sant'Anna and Zhao2020), with constituency and election fixed effects and with the outcome conditioned on covariates for homes protected and, in the models indicated, deprivation. Cell entries are coefficients (standard errors); *p

![]() $>$ 0.05; **p

$>$ 0.05; **p

![]() $>$ 0.01; ***p

$>$ 0.01; ***p

![]() $>$ 0.001.

$>$ 0.001.

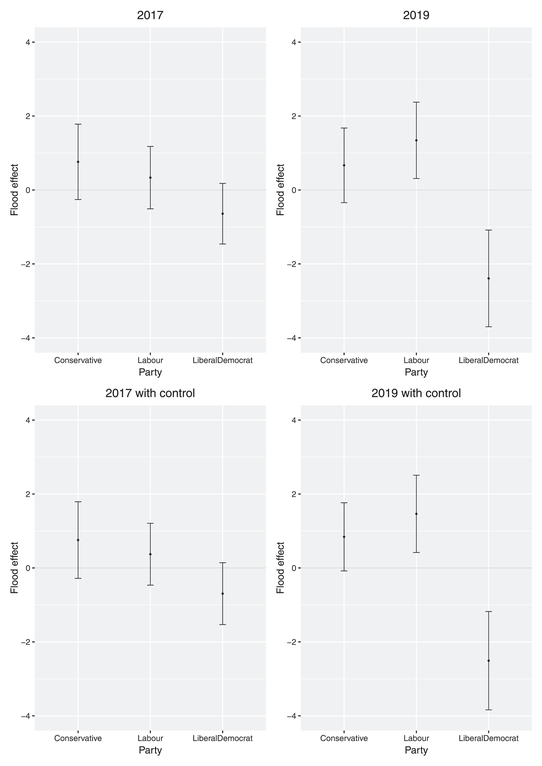

The data on homes protected from flooding are available only for the 2015–2017 and 2017–2019 periods, due to the temporal extent of the scheme that generated these data, but inclusion of homes protected as a covariate allows me to disentangle the electoral effects of flooding from those of flood defence spending at two elections. The results of this analysis are presented in as the models in Table 2 and the estimated effects plots in Figure 6. Again, none of the relevant coefficients in the 2017 models is significant. Once flood spending is taken into consideration, the Conservative boost from flooding in 2019 falls below conventional levels of statistical significance, yet Labour still wins significantly more votes in flooded areas in 2019, and the Liberal Democrats fewer votes. This indicates that the increased vote share for the Conservatives in flooded areas could in part be due to the fact that those areas are also those most likely to be the site of flood defence projects. This is consistent with previous accounts that have found flood spending to be linked to an advantage for incumbents (Bechtel & Hainmueller, Reference Bechtel and Hainmueller2011; Blankenship et al., Reference Blankenship, Kennedy, Urpelainen and Yan2021; Cole et al., Reference Cole, Healy and Werker2012; Gasper & Reeves, Reference Gasper and Reeves2011; Healy & Malhotra, Reference Healy and Malhotra2009; Lazarev et al., Reference Lazarev, Sobolev, Soboleva and Sokolov2014), and it somewhat weakens the rally-round-the-leader interpretation of the models in Table 1. By contrast, the effect of flooding on the Labour vote share is both larger in magnitude and stronger in significance in the 2019 models that control for flood defence spending.

Figure 6. Models with flood defences.

The models in Table 2 figure covariates as conditioning factors in the first stage of a two-stage estimation process (Sant'Anna & Zhao, Reference Sant'Anna and Zhao2020), thus no coefficient for flood defence projects appears in the final models reported here. In order to gain insight into the independent effects of flood defence efforts on vote share, we can turn to models with a similar specification run using a standard two-way fixed effects estimation strategy. These models do not include the demographic control (deprivation), as that is a time-invariant census indicator that is absorbed by the fixed constituency effects, so these models include only flooding during the preceding inter-electoral period and the protection of homes during the same period via the construction of flood defences. These models, which are presented in Table A4 of the Supporting Information, are substantively very similar to the models in Table 2, but they also show the erection of flood defences to have a positive impact on Conservative party vote share in both 2017 and 2019, giving the incumbents a boost of 1.8 percentage points in 2017 and 1.5 in 2019, which translates into an estimated £1886 ‘cost’ per vote in 2017 and a £3173 ‘cost’ in 2019 (see Section 9 of the Supporting Information for details of the calculations behind these figures). In the 2019 model, flood defences are also associated with a 1.2 percentage point depression in the Labour party vote share. Together, these effects are insufficient to make a major dent on the electoral benefit that Labour derived from flooding at the 2019 election. It seems the Conservatives were not entirely successful in using flood defence spending to undo the damage to their environmental credentials that had taken place between 2015 and 2019.

Interestingly, additional models designed to test for expected moderating effects of flood defence work on the treatment showed no significant interactions (see Table A5 in the Supporting Information); it seems that flooding and flood defence spending exert independent influences on voter behaviour. This is potentially because much flood defence work takes place in constituencies that are not flooded in any specific inter-electoral period, or because flooding and flood defence work are spatially and temporally distant enough when they both take place that they are not strongly associated in voters' minds.

A further relevant question is what substantive impact on government formation flooding might have had. The significant coefficients in the models in Tables 1 and 2 suggest shifts in vote share of a couple of percentage points or less. Analysis of the electoral majorities of the winners in each seat estimate that if there had been no floods in the 2010–2015 period, the Conservative majority would have been sufficiently depressed in flooded areas for it to have lost two marginal seats: City of Chester and Wirral West, both in the north of England. In absolute terms, the likely impact of flooding was slight, but given that the Conservatives held a very slim majority of 12 following the 2015 contest, these findings suggest that in the absence of flooding during the pre-electoral period, the party's ability to govern could have been weakened to a degree that would have been politically relevant. In 2019, the situation was different; in the absence of flooding, the results predict that Labour would have lost one seat – Dagenham and Rainham in east London – to the Conservatives, but this would have had no material impact on the overall outcome of the election, given that the Tories won this election by a solid majority.

Robustness checks, presented in detail in the Supporting Information, include the demographic covariate model specification in Table 2 implemented using standard two-way fixed effects instead of Sant'Anna and Zhao's doubly robust regression approach (Table A4 in the Supporting Information). As can be seen in this table, there are no substantive differences between the two sets of models. A second robustness check involves running models in which the dependent variable is support for the constituency incumbent, rather than for a specific party. It could, in theory, be that flooding generates local reactions for or against the sitting MP, rather than votes for or against a national-level party. The incumbency models, presented in Table A6 and Figure A2 in the Supporting Information, largely disprove this conjecture, as they show no consistent effect for incumbency. In 2015, flooding is associated with a depression in the vote share of the incumbent by about two percentage points, in 2017 there is no significant effect, and in 2019 flooding predicts an increase in incumbent vote share by approximately two-and-a-half percentage points. This varying pattern is more consistent with the party position-taking story discussed above than it is with any reaction specifically linked to local incumbents.

A final stage in the analysis considers flood intensity. The main models presented in this paper are based on binary indicators of flooding. The models in Table A7 in the Supporting Information use an alternative interval measure that reflects flood intensity, the logarithmFootnote 4 of the number of floods experienced in a constituency during the period in question. This measure is preferable to the geographic area flooded at any given time, which often corresponds poorly to the human impact of flooding. The doubly robust regression approach used in the main models above requires the treatment to be binary, so the models shown here use, instead, standard two-way fixed effects. As noted above, the two-way fixed effects models that rely on the binary flooding measure generate output that is substantively extremely similar to the doubly robust models, which suggests that little is lost here by relying on two-way fixed effects. Given that it is not possible to include time-invariant demographic controls in two-way fixed effect regression models, I use here job density and house prices as time-varying measures of deprivation. House prices are an indicator having the added advantage that it captures potential post-treatment effects, as house prices in the United Kingdom have been found to be depressed for several years following flooding (Beltrán et al., Reference Beltrán, Maddison and Elliott2019). The models in Table A7 are for the most part very similar to those based on the binary flood variable. The one noteworthy difference is the consistently positive effect that flooding seems to have on the Conservative vote share in the 2019 election, even controlling for flood defence erection. Though these models also suggest that Labour was the main beneficiary of flooding in 2019, it seems that there could also have been a rally effect, especially in areas especially hard hit by multiple inundations.

Conclusion

Most studies of the political impacts of natural and other disasters focus on individual events, and these findings of these analyses could in part reflect factors specific to the political context at the time the event occurred. The unique situation of institutional stability in the United Kingdom between 2010 and 2019 makes it possible to study the effect of flooding over multiple elections. In doing so, I have shown that the effect of flooding on electoral results is strongly suggestive of a relationship conditioned by party political factors, which varied over the period in question. There is patchy support for the rally-round-the-leader hypothesis that those who experienced flooding should be more willing to favour the status quo, but this is evident in two out of three elections only, and not in all model specifications. The blind retrospection hypothesis receives no support in this analysis; if voters punished the incumbents for floods, the Conservatives would have suffered consistently. Instead, the initial Conservative advantage in 2015 followed by a benefit particularly for Labour in 2019 is consistent with the hypothesis that the impact of flooding on electoral outcomes is shaped by political competition. Over time, Labour became stronger on the environment, whereas the Conservatives' brief flirtation with greenery had faded by 2019. Although the construction of flood defences benefited the incumbent Tories, this effect did not entirely negate the impact of the political competition effect. By the end of the period, the opposition Labour party still derived a net benefit from flooding.

The design of this research has made it possible to probe the electoral effects of flooding over both space and time, which enables the assessment of hypotheses such as party position-taking and party image that remain constant in given elections. These findings point to the relevance of political context and indicate that studies based on single extreme weather events and single elections may not be sufficient to tease out impacts. They also call for comparative assessment over longer time periods of the impact of floods and other natural disasters, which in many cases lend themselves well to such analysis, given that they often straddle national borders. With three sets of election results in one country, this paper is suggestive of longitudinal variation in flood effects that change with party positions, but further research is required to confirm this interpretation of the findings and to ascertain whether it can be generalized to other national settings.

The United Kingdom is also unusual in that flood-related spending is devoted mainly to proactive flood defences rather than to retroactive flood relief. Given the temporal and spatial disjuncture between flood defence erection and flooding, it is possible to disentangle the effects of incumbent action on flooding from flooding itself, which is far more difficult in contexts where governments spend heavily on flood relief measures that are closely linked temporally and spatially to flood events. The findings of this study, that flooding and flood action generate distinct responses from voters, invite research designs in other jurisdictions that are able to distinguish between these two effects. In addition, future research could usefully draw on individual-level data to probe the social-psychological drivers of reactions to flooding, which would make it possible to assess this topic in relation to recent literature on policy feedback effects (Jacobs & Mettler, Reference Jacobs and Mettler2018; Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Mettler and Zhu2021) and to explore whether flood policy initiatives engender further shifts in public opinion on this issue. We know that in the UK context voters chose parties at least in part based on policy positions (Fieldhouse et al., Reference Fieldhouse, Green, Evans, Mellon, Prosser, Schmitt and van der Eijk2020; Ford & Goodwin, Reference Ford and Goodwin2014; Milazzo et al., Reference Milazzo, Adams and Green2011), so it is reasonable to assume that patterns in aggregate vote share that track party policy shifts follow from conscious decisions by voters to take flood policy into account when voting, but further research could usefully assess this assumption in greater detail. The analysis of individual-level data would also make it possible to probe the causal channels behind the effects observed here; specifically, it would be of interest to ascertain whether voter reactions to floods were driven by egocentric or sociotropic concerns, and also to analyse variations in reaction within constituencies. As climate change increasingly causes extreme weather events, the political effects of such events are bound to grow in substantive and scholarly importance and much work remains to be done in this emerging field.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the research assistance of Frida Koslowski and Lucie Delobel, together with research support from King's College London. I am also thankful for useful comments on earlier drafts of this paper from Marco Giani, Christel Koop, Gabriel Leon, Rubén Ruiz-Rufino and Francesca Vantaggiato. The usual caveat applies.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Data S1

Data S2

Data S3