Introduction

In the summer of 2024, Livingston County Circuit Judge Ryan Horsman exonerated Sandra Hemme, a 64-year-old woman from Missouri and a psychiatric patient who had spent over four decades in prison after being wrongfully convicted of the murder of a library worker in 1980. Notably, there was no evidence that connected the innocent woman to the victim or the crime scene. The sole basis for her conviction was an unreliable and false confession she provided to the police while undergoing psychiatric treatment. A subsequent review revealed that local police had overlooked evidence directly linking the murder to a police officer, who was later imprisoned for another crime. Sandra Hemme’s case is now considered one of the biggest judicial errors in U.S. history, demonstrating systemic flaws in the criminal justice system. Could this kind of weakness in judicial decision-making be attributed to factors such as the language judges use during trials, their cognitive abilities (e.g., working memory capacity), and their affective competencies (e.g., levels of emotional intelligence)?

Judicial decisions are influenced by a complex array of factors, including judges’ personalities and their personal and professional experiences (Posner, Reference Posner2010). Although it has been argued that judicial decision-making is primarily a cognitive and rational process, theoretical analyses of this process show that judges experience a range of emotions while delivering their verdicts. These emotions—including attitudes and sentiments toward the defendants and victims, as well as feelings of anger triggered by the events leading to the trial—can potentially impact the judges’ final decisions (Hastie, Reference Hastie2001; Nuñez et al., Reference Nuñez, Schweitzer, Chai and Myers2015). Moreover, recent studies have revealed that social and moral transgressions are perceived as more severe when they are assessed in the first language (L1) compared with a language acquired later in life (L2), and that higher levels of emotional intelligence are linked to stronger emotions and harsher judgments of offence seriousness (Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Mavrou, Kyriakou and Lorette2024).

The effect of language on moral decision-making, commonly referred to as the moral foreign language effect (MFLE) (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Foucart, Hayakawa, Aparici, Apesteguia, Heafner and Keysar2014), may arise from reduced sensitivity to deontological norms (i.e., the duty to act according to social and moral norms irrespective of the consequences) and decreased attention to consequences (i.e., the belief that breaking moral norms is acceptable if it prevents major harm) (Białek et al., Reference Białek, Paruzel-Czachura and Gawronski2019; Muda et al., Reference Muda, Niszczota, Białek and Conway2018) when individuals process information in their L2. However, an increasing body of research has questioned the robustness of the MFLE. This is unsurprising as the bilingual community is highly diverse (De Bruin, Reference De Bruin2019), and various language-related factors (e.g., the linguistic proximity between L1 and L2, the cultural influence of L2 in bilinguals’ L1 society; Dylman & Champoux-Larsson, Reference Dylman and Champoux-Larsson2020; Kyriakou & Mavrou, Reference Kyriakou and Mavrou2023b), as well as nonlinguistic or extralinguistic factors (e.g., emotional intelligence, empathy, moral identity; see Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Mavrou, Kyriakou and Lorette2024; Mavrou et al., Reference Mavrou, Mavrou and Kyriakou2025; Romero-Rivas et al., Reference Romero-Rivas, López-Benítez and Rodríguez-Cuadrado2020), appear to mitigate or even cancel out the effect. Moreover, (moral) decision-making requires people to be able to hold and process different options in their memory and judge them based on rational thinking processes that tap into working memory, as well as past experiences retrieved from episodic memory and declarative knowledge that guides problem solving (e.g., Bornstein & Norman, Reference Bornstein and Norman2017; Evans & Stanovich, Reference Evans and Stanovich2013; Nicholas & Mattar, Reference Nicholas, Mattar, Samuelson, Frank, Toneva, Mackey and Hazeltine2024), with all these processes being more cognitively demanding in an L2 compared with the L1. However, these factors have not been studied systematically, and thus more research is needed to fully clarify their role in moral decision-making. Additionally, it is important to note that the available evidence on the MFLE derives from studies that mainly focus on European citizens who live in Western countries (see Del Maschio et al., Reference Del Maschio, Crespi, Peressotti, Abutalebi and Sulpizio2022, for a review), whereas moral decision-making among Asian bilinguals, who grew up in their home country but moved later to Europe and were immersed in an L2 society and culture, remains an unexplored research context.

This study aimed to contribute to a deeper understanding of both language-related and nonlinguistic variables that may influence the MFLE. To this end, it focused on Chinese–English bilinguals who grew up in China but were immersed in an English-speaking country at the moment of data collection and were studying different degree programs using their L2. Our goal was to investigate the extent to which individual differences in their emotional intelligence and executive functions influenced their moral judgments and emotions in response to five moral dilemmas, which were presented to them either in their L1 or in their L2. As the language of presentation of the dilemmas represents only part of the language-related factors involved in moral decision-making, we also considered and assessed our participants’ L2 proficiency level, age of onset of L2 acquisition, and length of L2 immersion. In addition to the above factors, emotions have been viewed as an important mediating factor in the relationship between language and moral decision-making (Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Mavrou, Kyriakou and Lorette2024; Kyriakou et al., Reference Kyriakou, Foucart and Mavrou2023). Thus, we also considered the mediating role of emotions in the current study.

The Moral Foreign Language Effect

The MFLE is the phenomenon by which bilinguals’ moral behavior varies depending on the language they use (L1 vs. L2) to read and process moral dilemmas; for example, bilinguals often provide utilitarian responses (i.e., decisions that involve causing physical harm, although they are associated with the most positive outcome; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Morelli, Lowenberg, Nystrom and Cohen2008) when they judge moral dilemmas in their L2, as opposed to their L1. Importantly, the majority of studies on this topic (e.g., Corey et al., Reference Corey, Hayakawa, Foucart, Aparici, Botella, Costa and Keysar2017; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Foucart, Hayakawa, Aparici, Apesteguia, Heafner and Keysar2014; Geipel et al., Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015b; Hayakawa et al., Reference Hayakawa, Tannenbaum, Costa, Corey and Keysar2017) have presented bilinguals with two classic moral dilemmas: the personal footbridge dilemma (Thomson, Reference Thomson1985) and the impersonal switch dilemma (Foot, Reference Foot1967). In the footbridge dilemma, five people who are tied to a train track are about to be killed by an out-of-control train. The only way to stop the train and save the five people is to push a corpulent man onto the tracks, causing his death. This is a highly emotionally charged moral dilemma, as respondents would directly harm one person to save more lives. Similar to the footbridge dilemma, in the switch dilemma five people are trapped on the train tracks and are at risk of being killed by an out-of-control train. However, in this scenario, a switch can alter the train’s direction, so the train runs over one person instead of killing five. This impersonal version of the footbridge dilemma is considered less emotional, as respondents do not directly cause bodily harm to another individual.

Consistent evidence has indicated that, in the personal dilemma, bilinguals were more prone to push the corpulent man onto the tracks––thereby killing him––when they read this dilemma and made their decision in their L2; by contrast, they were more likely to adhere to deontological rules (i.e., no one has the right to kill a person regardless of the reasons behind the act of killing) when processing the same scenario in their L1 (see Del Maschio et al., Reference Del Maschio, Crespi, Peressotti, Abutalebi and Sulpizio2022, for a review). In the impersonal switch dilemma, bilinguals’ decisions did not differ significantly across language conditions (L1 vs. L2). In fact, they showed a greater preference for saving the five people by switching the train’s direction (an indirect and less emotional action), rather than causing the death of a person (a direct and emotionally charged action), regardless of the language they used.

In one of the first studies on the MFLE, Costa et al. (Reference Costa, Foucart, Hayakawa, Aparici, Apesteguia, Heafner and Keysar2014) explained this phenomenon based on the dual process theory (DPT) of moral judgment (Greene, Reference Greene, Gazzaniga, Strick, Graybiel, Mink and Shadmehr2009; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley and Cohen2001), which posits that moral judgments involve the integration of two independent and competing components: emotion and reasoning. Emotional processes are typically referred to as Type 1 and are fast and automatic, favoring deontological decisions that tend to be intuitive and affective (e.g., that it is immoral to harm another person). Rational thinking processes, which are known as Type 2, are slower, rely on working memory (Evans & Stanovich, Reference Evans and Stanovich2013), and encourage individuals to consider the consequences of their actions and prioritize overall well-being. According to the DPT, Type 2 processes are optional and will be involved only when a dilemmatic scenario requires more deliberative effort; that is, these processes may serve as an error-corrective mechanism when fast and intuitive responses diverge from those generally considered accurate based on standard logic (Bago & De Neys, Reference Bago and De Neys2017). The DPT has been further supported by evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and reaction time (RT) data. For example, fMRI and RT results in Greene et al.’s (Reference Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley and Cohen2001) study revealed that only personal dilemmas triggered increased activity in brain areas involved in emotion, such as the medial frontal gyrus, posterior cingulate gyrus, and angular gyrus, prompting individuals to make more deontological (emotional) decisions in their L1. By contrast, impersonal dilemmas evoked less emotional engagement, which led to more rational decision-making.

Although evidence about the mechanisms underlying the MFLE is still insufficient and rather unconvincing, the reduced emotionality (or “feeling less in the L2”) hypothesis and the cognitive enhancement (or “thinking more”) hypothesis align well with the DPT framework. The reduced emotionality hypothesis posits that bilinguals are more likely to make fewer deontological decisions in their L2 due to dampened emotional associations between L2 words and their emotional context (Opitz & Degner, Reference Opitz and Degner2012). In other words, L2 emotion words are believed to be less intensely felt than L1 emotion words due to their lower frequency of use, bilinguals’ lower proficiency in their L2, and decreased emotionality of the context in which L2 is acquired, among other factors; this emotional detachment allows bilinguals to process emotional information, including moral dilemmas, from a more rational perspective. Support for this hypothesis comes from studies suggesting that the MFLE is mediated by emotion (Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Mavrou, Kyriakou and Lorette2024; Kyriakou et al., Reference Kyriakou, Foucart and Mavrou2023), and that the emotionality of words included in questions about moral issues has an impact on bilinguals’ moral judgments (e.g., Kyriakou & Mavrou, Reference Kyriakou and Mavrou2025). However, other studies have revealed that individuals experience a similar range of emotions in response to emotionally charged moral dilemmas regardless of the language used (e.g., Kyriakou & Mavrou, Reference Kyriakou, Mavrou, Canales and Leralta2023a), or have failed to observe a significant interaction between language, emotion, and moral decision-making (Geipel et al., Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015a, Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015b).Footnote 1

The cognitive enhancement hypothesis states that using an L2 may be cognitively demanding, particularly when bilinguals lack a high L2 proficiency level (Plass et al., Reference Plass, Chun, Mayer and Leutner2003). Consequently, the increased cognitive load associated with processing moral scenarios in an L2 encourages individuals to reflect more deeply on their decisions, rather than responding intuitively, which may lead to a heightened inclination toward utilitarian responses (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Foucart, Hayakawa, Aparici, Apesteguia, Heafner and Keysar2014; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Morelli, Lowenberg, Nystrom and Cohen2008). However, several studies indicate that the quality of Type 2 reasoning does not differ significantly between L1 and L2 (Białek et al., Reference Białek, Muda, Stewart, Niszczota and Pieńkosz2020; Geipel et al., Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015a; Kirova & Camacho, Reference Kirova and Camacho2021; Milczarski et al., Reference Milczarski, Borkowska, Paruzel-Czachura and Białek2024; Muda et al., Reference Muda, Milczarski, Borkowska and Białek2025). Additionally, other language-related factors, such as an early age of L2 onset, L1–L2 linguistic proximity, prolonged exposure to L2 or immersion in an L2 society and culture, appear to reduce L2 cognitive load, thus mitigating the MFLE (see, e.g., Dylman & Champoux-Larsson, Reference Dylman and Champoux-Larsson2020; Kyriakou & Mavrou, Reference Kyriakou and Mavrou2023b; Wong & Chin Ng, Reference Wong and Ng2018).

The present study aimed to investigate the reduced emotionality hypothesis by asking participants to rate the emotional intensity they experienced after reading moral dilemmas in their L1 and L2 and testing the mediating role of emotion in the relationship between language and moral judgments by means of mediation analyses. In addition, we considered more language-related factors than the mere distinction between bilinguals’ L1 and L2 in order to explain variability (and potential cognitive disfluency) in bilinguals’ moral judgments; these factors were L2 proficiency level, age of onset of L2 acquisition, and length of immersion in the L2 environment. By assessing these factors, we also aimed to test the cognitive enhancement hypothesis. In the next section, we analyze the main findings of previous research on affective, cognitive, and language-related factors that seem to increase or diminish the occurrence of the MFLE.

Affective, cognitive, and language-related factors involved in (moral) decision-making

As mentioned previously, bilinguals tend to alter their moral choices depending on the language they use to respond to moral dilemmas. However, the results of previous studies do not always converge, and the presence or absence of the MFLE has been attributed to a range of affective, cognitive, and language-related factors, some of which are described below. Romero-Rivas et al. (Reference Romero-Rivas, López-Benítez and Rodríguez-Cuadrado2020) assessed the affective and cognitive empathy of Spanish–English bilinguals, who responded to the footbridge and the switch dilemmas in their L1 or L2. Their findings indicated that affective and cognitive empathy levels were significantly lower in the L2 condition. However, these empathy levels did not predict participants’ response type (deontological or utilitarian) to either dilemma. Different results were obtained by Dewaele et al. (Reference Dewaele, Mavrou, Kyriakou and Lorette2024) who assessed the emotional intelligence of British L1 speakers, Greek–English bilinguals, and Hungarian–English bilinguals. These participants watched four real-life videos depicting offences of varying moral severity (mild vs. extreme) and were asked to rate the seriousness of the offence and to report the emotional intensity they experienced while watching the videos. The results revealed that individuals with higher levels of emotional intelligence tended to make harsher judgments of the perpetrators of the offences and had more intense emotional reactions, regardless of the language used to watch the videos (L1/L2). Considering these mixed findings, we hypothesized that higher levels of emotional intelligence would lead to more deontological decisions and stronger emotional reactions in both L1 and L2.

Drawing on the cognitive enhancement hypothesis, Milczarski et al. (Reference Milczarski, Borkowska, Paruzel-Czachura and Białek2024) compared bilingual participants’ cognitive reflection while completing the Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT) (Frederick, Reference Frederick2005) and the Berlin Numeracy Test (BNT) (Cokely et al., Reference Cokely, Galesic, Schulz, Ghazal and Garcia-Retamero2012) in their L1 and L2. The CRT includes questions such as: “A baseball bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total, and the bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?”. Although the correct answer (5 cents) may seem counterintuitive, the initial response that typically comes to mind is 10 cents. The BNT focuses primarily on probability estimation, with questions such as: “Imagine we are throwing a five-sided die 50 times. On average, out of these 50 throws, how many times would this five-sided die show an odd number (1, 3, or 5)?”. Although the correct answer is 30, only a small percentage of individuals give this response. According to the authors, if bilinguals engage in more reflective thinking in their L2 than in their L1, they should provide a greater number of correct responses on both tests in the L2 condition. However, this did not happen; participants made a similar number of intuitive and computational errors across tests, regardless of the language they used. Similarly, Muda et al. (Reference Muda, Niszczota, Hamerski and Białek2025) asked Polish–English bilinguals to estimate the anticipated regret associated with taking a risky test that could detect fetal disorders but carried a higher risk of miscarriage, and to write down all their thoughts while processing the dilemma. The researchers failed to detect an effect of language on the number or content of their participants’ thoughts. These studies call into question the “thinking more” hypothesis (i.e., the supposed higher cognitive load bilinguals face when processing stimuli in their L2).

However, Privitera’s (Reference Privitera2024) study reached different conclusions. The researcher collected data from Mandarin–English bilinguals who had studied in an English-immersive environment (Singapore). These bilinguals read three different moral dilemmas––the footbridge dilemma, the burning building dilemma, and the organ transplant dilemma––in personal and impersonal versions and completed a Simon task that assessed cognitive control. According to the results, participants who scored higher on the Simon task tended to make more utilitarian decisions in their L2, but only in response to the footbridge dilemma, which raises questions about the generalizability of the findings. As Privitera (Reference Privitera2024) argued, this evidence for a modulatory role of cognitive control on the MFLE is limited since it only emerged in personal and impersonal versions of the footbridge dilemma. The researcher concluded that cognitive control may be involved in the disengagement of emotional Type 1 processes when processing emotionally charged moral dilemmas in a foreign language. Our study extends this scope by including a greater number of executive functioning tasks, as well as a measure of phonological short-term memory capacity, in order to disentangle the impact of working memory on moral judgments.

In addition to affective and cognitive factors, various researchers have emphasized the influential role of language-related factors in moral decision-making. Wong and Chin Ng (Reference Wong and Ng2018) were among the first to explore the MFLE among early bilinguals. In their study, a group of English–Chinese bilinguals, who started learning both languages before the age of three, were instructed to respond to a series of sacrificial moral dilemmas in their L1 or L2. The findings indicated that the presence of the MFLE is contingent upon the age of L2 acquisition: the earlier the age of L2 acquisition, the less pronounced the MFLE became.

Dylman and Champoux-Larsson (Reference Dylman and Champoux-Larsson2020) explored the boundaries of the MFLE by presenting the footbridge dilemma to Swedish participants who spoke English or French as an L2, in their L1 or L2 (Experiment 2). Their findings revealed that participants were more likely to push the corpulent man off the bridge to save five people when responding in their L2 French, whereas responses patterned similarly between L2 English and L1 Swedish. According to the authors, the similar proportion of deontological decisions in L1 Swedish and L2 English could be attributed to the influential role of the English language within Swedish culture. Similarly, Kyriakou and Mavrou (Reference Kyriakou and Mavrou2023b) argued that the absence of the MFLE among the Greek Cypriot–English bilinguals in their study was the result of the prevalent role of English in Cyprus, stemming from the island’s historical ties to the British Empire and the strong presence of English in education, commerce, and media.

Dylman and Champoux-Larsson (Reference Dylman and Champoux-Larsson2020) further investigated the role of linguistic similarity in the MFLE by analyzing moral decisions made by Swedish–Norwegian and Norwegian–Swedish bilinguals (Experiment 3). Swedish and Norwegian are linguistically intertwined and mutually comprehensible for speakers of each language. Their findings revealed that Swedish and Norwegian participants provided similar moral decisions in both languages, suggesting that the MFLE may diminish when L1 and L2 share significant linguistic and structural similarities (see also Circi et al., Reference Circi, Gatti, Russo and Vecchi2021, for a discussion of the role of linguistic similarity in the MFLE).

Another language factor that has gained increasing attention in studies on the MFLe is bilinguals’ L2 proficiency level. To date, existing evidence has continued to yield inconclusive findings. For example, Geipel et al. (Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015a) found that a lower L2 proficiency level led bilinguals to accept sacrificing one person in order to save five in the footbridge dilemma presented to them in the L2, while Mills and Nicoladis (Reference Mills and Nicoladis2023) failed to find an interaction between L2 proficiency and bilinguals’ moral decision-making. Kirova and Camacho’s (Reference Kirova and Camacho2021) study, on the other hand, revealed that bilinguals with high L2 proficiency were more likely to choose the utilitarian option compared to those with low L2 proficiency. This finding was unexpected, as increased L2 proficiency levels are thought to reduce the emotional detachment often associated with L2 (Pavlenko, Reference Pavlenko2012), leading to decisions that align more closely with those made in the L1 (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Foucart, Hayakawa, Aparici, Apesteguia, Heafner and Keysar2014; Geipel et al., Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015b). Consequently, further research is needed to unravel the relationship between L2 proficiency and moral decision-making.

Based on the above literature, this study addressed the following research questions and hypotheses:

RQ1: To what extent do language-related variables (L2 proficiency, age of L2 onset, length of L2 immersion) influence Chinese–English bilinguals’ moral judgments and emotions in response to moral dilemmas in their L1 and L2?

H1: We hypothesized that participants with higher L2 proficiency, an earlier age of L2 onset, and longer exposure to the L2 would make more deontological decisions and would report stronger emotions, similar to what would be expected if moral decision-making were taking place in the L1.

RQ2: To what extent do emotional intelligence and executive functions influence Chinese–English bilinguals’ moral judgments and emotions in response to moral dilemmas in their L1 and L2?

H2: We hypothesized that bilinguals with high emotional intelligence would make more emotional (i.e., deontological) decisions regardless of the language used (Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Mavrou, Kyriakou and Lorette2024). Furthermore, we anticipated that bilinguals who scored higher on executive functioning tasks would make more utilitarian decisions in their L1 and L2, at least in response to personal dilemmas (Privitera, Reference Privitera2024), and would efficiently manage the additional cognitive load resulting from using an L2.

RQ3: Does emotional intensity mediate the relationship between language (L1/L2) and moral judgments?

H3: We expected that Chinese–English bilinguals would feel stronger emotions in their L1, and that these emotions would mediate the link between language and moral decisions, confirming previous findings (Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Mavrou, Kyriakou and Lorette2024; Kyriakou et al., Reference Kyriakou, Foucart and Mavrou2023).

Method

Research design

This study is part of a larger project that investigated the relationship between language, emotion, and moral judgment. We collected data from 90 L1 Chinese–L2 English bilinguals who read and responded to a series of moral dilemmas and completed measures assessing their trait emotional intelligence, executive functioning skills (updating, inhibition, and shifting), and phonological short-term memory capacity. As measures of L2 proficiency, we administered the LexTALE (Lemhöfer & Broersma, Reference Lemhöfer and Broersma2012) and the Use of English section of the Oxford Placement Test (OPT; Allan, Reference Allan2004). We also collected information about their onset of English instruction and length of L2 immersion. The project received approval from the UCL IOE Research Ethics Committee (Ref. no. REC1863) and the current study was preregistered prior to data collection and analysis (https://osf.io/vfm3q/).

Participants

Among the 90 Chinese–English bilingual speakers, 76 were female and 14 were male, and the mean age was 25.84 (SD = 3.92). All participants were born in China, reported having Chinese as their L1, and had started learning English at a young age (M = 7.84, SD = 2.88), mainly in instructional settings. They had been living in the UK at the time of data collection for an average period of 12 months (M = 12.40, SD = 10.92, missing data = 12) and were studying for or had completed master’s or PhD degrees. Participants self-reported an average English proficiency of 7.44 (SD = 0.99) in reading, 5.93 (SD = 1.01) in writing, 6.08 (SD = 1.24) in speaking, and 7.13 (SD = 1.23) in listening (on a 0–10 scale). Their mean scores on the LexTALE (M = 71.07, SD = 10.29) and the OPT (M = 76.32, SD = 8.19) indicate an intermediate to advanced level of English proficiency. This classification is consistent with previous validation studies showing that LexTALE scores around 70 and above typically correspond to CEFR levels B1–C1 (Brysbaert, Reference Brysbaert2013; Izura et al., Reference Izura, Cuetos and Brysbaert2014; Lemhöfer & Broersma, Reference Lemhöfer and Broersma2012), and that OPT scores in the mid-70s are similarly associated with intermediate to upper-intermediate proficiency levels (Allan, Reference Allan2004; Purpura et al., Reference Purpura, Hill and Lee2021).

Materials

Moral dilemmas

We initially included six moral dilemmas.Footnote 2 However, data from one of them (the speedboat dilemma) primarily led to either a utilitarian or a selfish response, contrary to the other five dilemmas for which deontological responses were clearly identifiable. In order to avoid confounding results due to variability in the type of response, data from the speedboat dilemma were dropped from subsequent analyses. Therefore, in what follows, we describe the five dilemmas that were used in this study.

In the footbridge dilemma, participants had to decide whether they would be willing to push a corpulent man off a footbridge in order to stop a train from killing five workers who were tied to the train tracks. The moral question accompanying this dilemma was the following: “Would you kill the man to save five workers? Yes/No,” with Yes representing a utilitarian decision and No a deontological one. In the vaccine dilemma, they had to decide whether they would test a vaccine on two innocent people, risking one’s life, in order to save hundreds of people with it (“Would you kill one of these people to identify a vaccine that will save lives?” Yes [utilitarian]/No [deontological]). In the transplant dilemma, they had to decide whether they would perform an organ transplant using the organs of a healthy young man to save five patients (“Would you perform this transplant to save five of your patients? Yes [utilitarian]/No [deontological]). In the lost wallet dilemma, participants had to choose between keeping the money found in a lost wallet or returning it to the owner (“Would you steal the money included in the wallet? Yes [utilitarian]/No [deontological]). The aforementioned dilemmas were taken from Koenigs et al. (Reference Koenigs, Young, Adolphs, Tranel, Cushman, Hauser and Damasio2007). In the cheater’s dilemma, they were asked to choose between telling their partner that they had cheated on them or hiding the truth (“Would you tell your partner that you cheated on him/her?” Yes [deontological]/No [utilitarian], with reverse scoring applied to match the previous dilemmas); this dilemma was taken from Kyriakou and Mavrou (Reference Kyriakou, Mavrou, Canales and Leralta2023a). Except for the lost wallet dilemma, all of them were personal dilemmas, with the first three describing situations that involve provoking physical harm to someone (unrealistic dilemmas) and the remaining two referring to situations that are likely to occur in real life (realistic dilemmas).Footnote 3

All the dilemmas were originally written and administered in English, but for this study, they were also translated into Mandarin. Both forward (English to Chinese) and back translations were conducted by two Chinese–English bilinguals who had been immersed in the L2 environment for several years, studying applied linguistics at the doctoral level. One also held a master’s degree in psychology and TESOL, and the other had previously studied interpreting and translation. The discrepancies were discussed and resolved in a meeting, and the final versions of the dilemmas were created.Footnote 4 These discrepancies mainly concerned lexical choices (e.g., the word however was not used in the translation into Chinese but was added in the back translation to convey the meaning better; the text you have read vs. the text you read just now; want to visit vs. would like to visit), literal translations (e.g., your mission is to vs. your task is to; to save the lives of the five workers vs. to save the five workers), and grammatical issues (e.g., tense judgments based on context in Chinese).

The order of presentation of the dilemmas and the language in which the participants had to read them (L1 or L2) were counterbalanced using a Latin square design. After reading each dilemma, participants indicated the degree of emotional intensity they experienced while reading the dilemma using a 10-point Likert scale (1 = no emotion at all, 10 = very strong emotions) and responded to the question accompanying each moral dilemma using a dichotomous Yes/No scale.

Trait emotional intelligence questionnaire

Trait emotional intelligence is understood in this study as the constellation of mental abilities and specific personality traits that influence how people process affective information and positive and negative emotions (Petrides, Reference Petrides, Stough, Saklofske and Parker2009a; Petrides & Furnham, Reference Petrides and Furnham2001). Emotional intelligence was assessed with the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire–Short Form (TEIQue-SF; Petrides, Reference Petrides, Stough, Saklofske and Parker2009a, Reference Petrides2009b). The TEIQue-SF is a 30-item questionnaire that taps into four self-perception facets of emotional intelligence: well-being, self-control, emotionality, and sociability. Participants had to indicate their agreement with each statement using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Composite scores were created by averaging participants’ responses. Internal consistency for the TEIQue-SF based on the data of the current study was found to be satisfactory (Cronbach’s α = .894, 95% CI [.859, .922]).

Measures of Executive Functions

Executive functions refer to a set of mechanisms that regulate cognition and control the mental operations performed within the memory system. This study assessed three executive functions—namely, inhibition, updating, and shifting—using computerized versions of the Emotional Stroop Task, the Operation Span Task (OSPAN), and the Color Shape Shifting Task, respectively. These tasks were administered via the Inquisit Lab platform.

The Emotional Stroop Task (Smith & Waterman, Reference Smith and Waterman2003) has been previously employed to assess cognitive control (Cromheeke & Mueller, Reference Cromheeke and Mueller2014; Song et al., Reference Song, Zilverstand, Song, D’Oleire Uquillas, Wang, Xie, Cheng and Zou2017). In our study, this task was used to measure inhibition of cognitive interference. Cognitive interference refers to “thoughts that intrude on task-related activity and serve to reduce the quality and level of performance” (Sarason et al., Reference Sarason, Sarason, Pierce, Saklofske and Zeidner1995, p. 285). In this task, participants were presented with sets of affective and neutral words from five categories (aggression, neutral, positive, negative, and color words) in colored font (blue, red, yellow, and green), and they had to indicate, as quickly as possible, the color of each word, ignoring its meaning or emotional connotation. Mean latencies for the color-word category were used in subsequent analyses.

The OSPAN (Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Heitz, Schrock and Engle2005) assesses updating ability and general working memory functions related to updating (such as retrieving from long-term memory and maintaining information in working memory for a short period of time). The OSPAN is a widely used task in applied linguistics research, which increases the comparability of our results with previous research. Participants saw mathematical equations accompanied by a proposed solution and had to decide whether the solution was correct. The cut-off for accuracy in solving the mathematical problems was set at 85% (Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Heitz, Schrock and Engle2005). After solving each mathematical operation, sets of three to seven letters appeared, and the participants had to retain these letters in the exact order of presentation and pick them from a provided 4 × 3 letter matrix. We calculated two scores: (1) the sum of all perfectly recalled sets (OSPAN absolute), and (2) the total number of letters recalled in the exact order (OSPAN total number correct). The correlation between these two scores was very high (r = .913, p < .001), suggesting that they can be used interchangeably. We chose to use the first score (OSPAN absolute) in subsequent analyses due to the greater range (and thus variability) of values (Range = 15–75).

Shifting ability was measured with the Color Shape Shifting Task (Friedman et al., Reference Friedman, Miyake, Young, DeFries, Corley and Hewitt2008; Miyake et al., Reference Miyake, Emerson, Padilla and Ahn2004). In this task, participants were presented with red or green circles, and red or green triangles, and they had to sort the stimuli either by color or by shape as quickly as they could by pressing different response keys for each combination of color and shape. Specific cues indicating what participants had to focus on (color or shape) were given in advance. The switch cost was computed as the mean reaction-time difference between (correct) switch and (correct) repeat trials. Positive values indicate that it took participants, on average, longer to respond to switch trials (i.e., shifting from the color task to the shape task).

We also used a nonword repetition task, taken from Lee (Reference Lee2008) and used in Zhao (Reference Zhao2013), in order to assess participants’ phonological short-term memory capacity. The task included 48 single-syllable nonword Pinyin items, which were recorded and presented to the participants in sequences of two to nine nonwords and at a rate of one nonword per second. For each sequence length, the participants had three trials. If they failed all three trials, the test was terminated, and the previous sequence was counted as the participant’s nonword span as long as all trials were correct at that length level. If one of the trials at the previous sequence length was incorrect, the nonword span was calculated as the previous length minus 0.3, and if two trials were incorrect, the nonword span was the previous length minus 0.6.

Measures of language-related variables

We considered three language-related variables: L2 proficiency level, age of onset of L2 acquisition (AoA), and length of immersion in the L2 context. L2 proficiency was assessed based on participants’ self-reports of their L2 English skills in reading, writing, speaking, and listening via 10-point Likert scales. This is a common practice in studies on the MFLE to assess L2 proficiency. However, to address self-report bias, we also employed the Lexical Test for Advanced Learners of English (LexTALE; Lemhöfer & Broersma, Reference Lemhöfer and Broersma2012) and the Use of English section of the OPT (Allan, Reference Allan2004). The LexTALE is a lexical decision task in which participants have to indicate whether each of the 60 items in the test is an English word or a pseudoword. The final score represents the percentage of correct responses, corrected for the unequal proportion of words (40 in total) and nonwords (20 in total) in the test using the following formula: ((number of words correct / 40 × 100) + (number of nonwords correct / 20 × 100)) / 2.

The OPT assesses English language ability and consists of two sections: language use and listening. In this study, we employed the Use of English section, which comprises 100 multiple-choice items. The OPT has been calibrated against the level system provided by the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR; Council of Europe, 2001); therefore, it provides scores that show whether a learner is within a specific CEFR band, from A1 to C2.

Some studies on the MFLE have opted for the LexTALE due to its accessibility, speed, ease of use, and the availability of valid versions in different languages (English, French, Dutch, German). However, this test is based on the lexical decision task paradigm, which assesses word recognition skills; it does not capture L2 learners’ ability to recognize or apply grammatical rules. Therefore, we decided to administer the Use of English section of the OPT as a complementary tool to assess L2 proficiency. This test focuses on both grammar and vocabulary, as well as meaning beyond the sentence level, requiring participants to understand implied meanings and the role of both context and speaker intention.

Information about participants’ AoA and length of immersion in the L2 environment was obtained via a language background questionnaire.

Data collection procedure

The data collection took place in the UK between April and October 2024. As mentioned previously, the study was part of a larger project that included one-to-one experimental sessions that lasted approximately 4 hours. Participation was voluntary, and each participant received a voucher of £30 to acknowledge their time and effort in completing the different tasks of the study. First, the participants read the information sheet and the consent form, which contained relevant information about anonymity and data confidentiality, as well as their right to withdraw at any moment. The participants then read the moral dilemmas. After reading each dilemma, they indicated the emotional intensity they experienced, answered the moral question, and then explained their emotions and justified their moral decision in written form, in the same language in which they read the dilemma (but the writing data were not considered in this study). Then, participants completed the working memory tasks (Emotional Stroop Task, Operation Span Task, Color Shape Shifting Task, and nonword-repetition Task, in this order), the OPT, the LexTALE, the TEIQue-SF, and a language background questionnaire. Participants were offered breaks between tasks to mitigate fatigue effects.

Statistical analyses

Before conducting the study, we carried out a power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007) with the following input parameters: effect size f2 = .15, representing a medium effect size, α = .05, power = .80, and number of predictors = 5 (three executive functions, phonological short-term memory capacity, and emotional intelligence). The suggested sample size was 92. For four predictors (language-related variables), the suggested sample size was 85. We collected data from 90 participants, resulting in 540 data points. Although our final sample size was slightly lower than we had planned for, it was still sufficiently large to detect effects close to a medium size.

The significance level for this study was set at α = .05. We estimated the descriptive statistics (mean, SD, skewness, kurtosis) for the quantitative variables of the study: participants’ emotional intensity in response to the five moral dilemmas (this was one of the outcome variables, along with moral judgment which was a categorical variable), emotional intelligence, measures of working memory and executive functions (updating, inhibition, shifting, and phonological short-term memory capacity), and language-related variables (L2 proficiency level, age of onset of L2 acquisition, length of L2 immersion). Then, we computed the correlations between two groups of variables. Aligned with our RQs, the first group of correlations comprised the language-related variables and the second group included emotional intelligence and memory functions; emotional intensity, which was a numeric variable, was included in both correlation matrices. We conducted these correlations to verify that the variables captured related but distinct components of the broader constructs under investigation (i.e., language background, executive functions, emotional intelligence). This analysis also provided an overview of the correlation structure of the data before fitting mixed-effects models and contributed to transparency by facilitating potential future meta-analyses. Although multicollinearity was formally assessed using variance inflation factor (VIF) values (all < 3), the correlation matrix complements these checks by illustrating the theoretical coherence of the measures used. We considered correlations of .25, .40, and .60 as small, medium, and large, following Plonsky and Oswald (Reference Plonsky and Oswald2014).

In order to answer the first two research questions, mixed-effects logistic and linear regression models were fitted in RStudio 2023.03.1 (Posit team, Reference team2023) using the lmer and glmer functions in the lme4 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015), with the optimizing function control = glmerControl(optimizer = “bobyqa”) (Linck & Cunnings, Reference Linck and Cunnings2015), the performance package (Lüdecke et al., Reference Lüdecke, Ben-Shachar, Patil, Waggoner and Makowski2021), and the robust package (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zamar, Marazzi, Yohai, Salibian-Barrera, Maronna, Zivot, Rocke, Martin, Maechler and Konis2022). In the case of the linear regression models, we also fitted robust mixed-effects models using the rlmer function from the robustlmm package (Koller, Reference Koller2016). Robust models provide parameter estimates that are less sensitive to outliers and violations of normality or homoscedasticity in the residuals and random effects. These analyses were conducted as a complementary check to assess the stability of the results across estimation methods. The scale() function was used to standardize our data and avoid convergence failure. Moral judgment (yes/no responses) and emotional intensity were the outcome variables in the logistic and linear regression models, respectively. We used 1 to code the utilitarian choice and 0 for the deontological choice. Similarly, L1 was coded as 0 and L2 as 1. The two groups of variables mentioned above (language-related variables, on the one hand, and emotional intelligence and executive functions, on the other) were the fixed effects when addressing RQ1 and RQ2, respectively. Participant ID and dilemma served as random effects in all analyses. The reason why we treated language-related variables, memory, and emotional intelligence in separate models was motivated, besides our research questions, by the fact that forcing too many unrelated variables into the same statistical model can lead to singular fit and convergence failure. For RQ3, we conducted a moderated mediation analysis using SPSS Process Macro version 4.1 (Hayes, Reference Hayes2022). Language was the independent variable, moral judgment the dependent variable, emotional intensity the mediator, and dilemma the moderator variable.

Finally, in order to assess the robustness of the four mixed-effects models to different model specifications, a series of sensitivity analyses were conducted. For each of these four models, we compared alternative model specifications that varied in their fixed- and random-effects structure. Specifically, we compared (a) a full model including all main effects and two-way interactions; (b) a reduced model excluding interaction terms; (c) a model focusing on key predictor subsets; and (d) a model including a random slope for language by participant. All models were estimated using the lmerTest package in R, with model performance assessed via Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), likelihood ratio tests, marginal and conditional R2, and root mean square error (RMSE), as implemented in the performance package.Footnote 5

Results

Main analyses of emotional intensity and moral judgments

The distributions of deontological and utilitarian responses to the five dilemmas, as well as the average emotional intensity that our participants experienced, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Distribution of deontological vs. utilitarian responses and emotional intensity per dilemma

Descriptive statistics for the remaining quantitative variables of the study, as well as the average emotional intensity regardless of the dilemma and language used, are summarized in Table 2. These statistics were based on the entire sample (N = 90), except for phonological short-term memory capacity (PSTM), which was based on N = 89, as data from one participant were lost due to technical issues. Overall, most values for skewness and kurtosis were between -2 and +2 and between -7 and 7, respectively, suggesting a normal univariate distribution (Byrne, Reference Byrne2010; Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010). Length of L2 immersion showed deviations from the above cut-off points, mainly because most participants had spent around 8 to 10 months in total in the UK (Mode = 9, Median = 9).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for the quantitative variables of the study

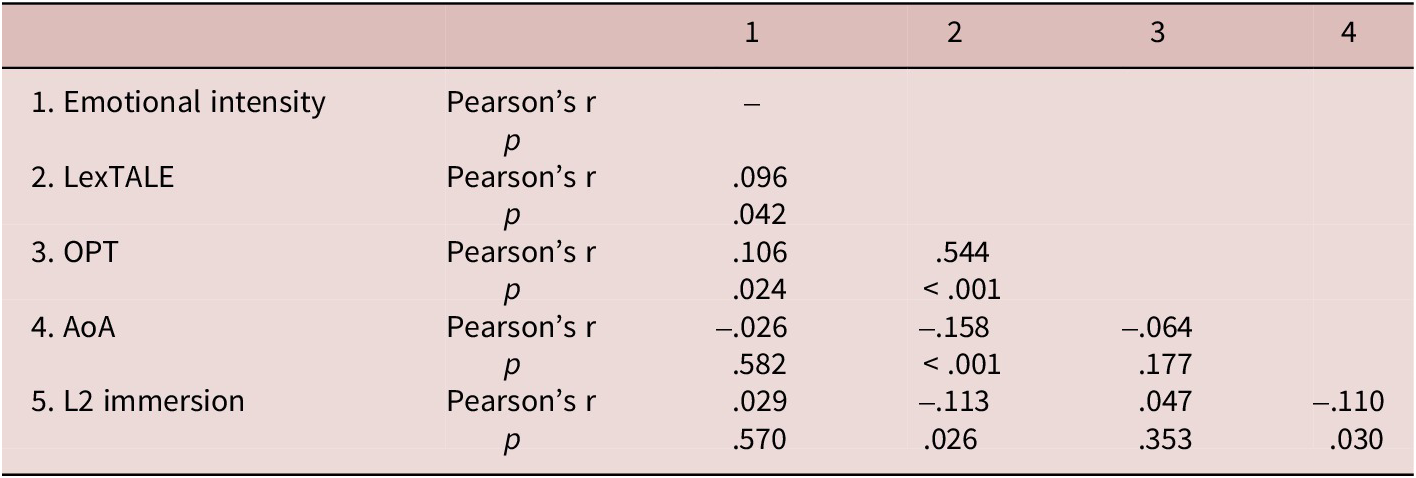

Correlations between emotional intensity, emotional intelligence, and executive functions are presented in Table 3, while Table 4 summarizes correlations between emotional intensity and the language-related variables, excluding self-reports, which were not used in subsequent statistical models. Participants’ scores on the different measures of executive functions and PSTM had significant positive correlations (except for two cases), but the magnitude of these correlations was below .35, suggesting that these tasks tapped into different components of working memory capacity. Emotional intelligence showed statistically significant positive correlations with updating and inhibitory control, but correlated negatively with PSTM. The average emotional intensity for the five moral dilemmas also correlated negatively with PSTM. Regarding the language-related variables, scores on the LexTALE had significant positive correlations with scores on the OPT, AoA, and L2 immersion. OPT scores were positively correlated with L2 immersion, but not with AoA. L2 proficiency level, as assessed with both the LexTALE and the OPT, also showed significant positive correlations with emotional intensity. The sizes of these correlations were all below what could be considered small, except for a medium-sized correlation between LexTALE and OPT (Plonsky & Oswald, Reference Plonsky and Oswald2014).

Table 3. Correlations between emotional intensity, emotional intelligence, and working memory capacity

Table 4. Correlations between emotional intensity and language-related variables

In order to answer the first research question, we ran two models with emotional intensity and moral judgments as the outcome variables, respectively. The L2 proficiency measures (LexTALE and OPT), age of L2 acquisition (AoA in years), L2 immersion (measured in months), the language of the dilemma (L1 vs. L2), as well as the interactions between the language of the dilemma and the remaining language-related variables, served as fixed effects, and participant ID and dilemma were included as random effects. In the second model, we also considered the interaction between emotional intensity and the language of the dilemma in order to address the potential moderating role of emotional intensity in moral judgments. Overall, the results did not show any statistically significant effect of the language-related variables on emotional intensity or moral judgments (see Tables 5 and 6, respectively). In the model examining the effect of language-related variables on emotional intensity, the interaction term Language × LexTALE showed a marginal effect (p = .063). The robust model yielded a t value above 1.96, suggesting that the effect may be statistically significant—that is, participants with higher LexTALE scores who responded to the dilemmas in their L1 reported greater emotional intensity. However, given this discrepancy between models, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Table 5. Effects of language-related variables on emotional intensity

Note: * p < .05. Statistically significant robust effects are marked in bold.

Table 6. Effects of language-related variables on moral judgments

Note: * p < .05.

In order to answer the second research question, we ran two additional models. In the first model, we investigated the emotional intensity that the participants experienced after reading the dilemmas as a function of their levels of emotional intelligence and executive functioning skills. The fixed effects in this model were scores on the emotional intelligence questionnaire, scores on the updating, inhibition, shifting, and PSTM tasks, language (L1 vs. L2), and the interactions between these individual-difference factors and language. The outcome variable was emotional intensity, and participant ID and dilemma were introduced as random effects (Table 7). None of the results reached statistical significance at the .05 level.

Table 7. Effects of emotional intelligence and executive functions on emotional intensity

Note: *** p < .001. Statistically significant robust effects are marked in bold.

The second model we ran to address RQ2 was identical, except for the outcome variable, which was moral judgment (see Table 8). The results revealed that participants with higher updating ability tended to make more deontological decisions, regardless of the language in which they read and responded to the dilemmas. Moreover, participants with better inhibitory control who responded to the dilemmas in their L1 also tended to make more deontological decisions (see Figure 1).

Table 8. Effects of emotional intelligence and executive functions on moral judgments

Figure 1. Interaction plot for the effects of inhibition and language on moral judgments.

Lastly, in order to address the third research question, we conducted a moderated mediation analysis to investigate whether emotional intensity had a mediating effect. However, as the influence of language was nonsignificant (see Tables 5–8), the indirect effects of the mediation model did not reach statistical significance either.

Robustness analyses of the mixed-effects models

As described above, four mixed-effects models were examined: Model 1 (emotional intensity predicted by language-related variables; Table 5), Model 2 (moral judgments predicted by language related variables; Table 6), Model 3 (emotional intensity predicted by executive functions, emotional intelligence, and language; Table 7), and Model 4 (moral judgments moral judgments predicted by the same cognitive-affective factors and language; Table 8).

For Model 1, the sensitivity analysis indicated that the additive model (without interaction terms) provided the best overall fit (AIC = 1721.4; BIC = 1757.1) and was statistically equivalent to the full interaction model (ΔAIC = 3.9, p = .40). Adding interaction terms or random slopes did not improve model performance (R2 conditional ≈ .54–.56), indicating that the effects of language-related variables on emotional intensity were primarily additive. Similarly, for Model 2, model comparison indicated that the additive model again offered the best fit (AIC = 359.9; BIC = 395.5; AIC weight = 0.987) and did not differ significantly from the full model (ΔAIC ≈ 9; χ2(5) = 0.98, p = .96). Conditional R2 values were comparable across specifications (≈ 0.50), suggesting that interaction terms and random slopes were unnecessary, and that the main model’s conclusions were robust.

For Model 3, the additive model also yielded the most adequate fit (AIC = 1941.0; BIC = 1982.0; AIC weight = 0.778), with no significant advantage for the full interaction model (χ2(5) = 7.14, p = .21). Conditional R2 values remained stable (≈.55–.57), indicating that executive functions and emotional intelligence influenced emotional intensity in an additive manner, and that the findings were consistent across specifications. In contrast, for Model 4, the full interaction model provided the best fit (AIC = 392.2; AIC weight = 0.69) and significantly outperformed the additive model (χ2(5) = 12.33, p = .03). Conditional R2 values were similar (≈ .52–.56), but the inclusion of interaction effects—particularly the Language × Inhibition interaction—improved model performance. This suggests that, for moral judgments, the influence of executive functions and emotional intelligence is partly interactive.

Overall, the sensitivity analyses confirmed that the main conclusions of the study were stable across reasonable variations in model specification. In three of the four models, additive structures were sufficient, whereas Model 4 benefited from interaction terms. These results strengthen confidence in the robustness and reliability of the findings.

Discussion

This study investigated the extent to which individual differences in emotional intelligence and working memory’s executive functions (updating, inhibition, and shifting), in addition to phonological short-term memory capacity, influenced Chinese–English bilinguals’ moral judgments and self-reported emotional intensity in response to five moral dilemmas that were presented to them either in their L1 or in their L2. The study also aimed to disentangle the role of three language-related variables, namely L2 proficiency level, age of onset of L2 acquisition, and length of L2 immersion, in an attempt to gain a more comprehensive insight into the role of language in bilinguals’ moral decision-making. According to the results, none of the language-related variables had an impact on our participants’ moral judgments or emotional intensity. However, we found an effect of executive functions. Specifically, participants with greater updating ability were more inclined toward the deontological option regardless of the language in which the dilemmas were presented. In addition, participants with better inhibitory control ability who responded to the dilemmas in their L1 also tended to make more deontological choices.

Regarding the role of language, and contrary to previous research (Bialek et al., 2019; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Foucart, Hayakawa, Aparici, Apesteguia, Heafner and Keysar2014; Kyriakou et al., Reference Kyriakou, Foucart and Mavrou2023; Kyriakou & Mavrou, Reference Kyriakou and Mavrou2025), the use of an L2 in our study did not increase utilitarian responses. This finding suggests that the MFLE may not be universally robust. Its absence in the current study could be attributed to our participants’ early age of L2 acquisition (< 10 years in most cases) and their daily exposure to L2 English across a variety of social and educational contexts, in addition to their relatively high L2 English proficiency (intermediate to advanced). Previous evidence indicates that bilinguals who start L2 acquisition before the age of 10 exhibit greater executive control compared with late bilinguals (Bialystok, Reference Bialystok2017; Luk et al., Reference Luk, De Sa and Bialystok2011) and tend to process the emotional content of words similarly across their different languages (Altarriba, Reference Altarriba2008; Pavlenko, Reference Pavlenko2012; Ponari et al., Reference Ponari, Rodríguez-Cuadrado, Vinson, Fox, Costa and Vigliocco2015). Therefore, early bilinguals––as was the case for our participants––may process moral dilemmas in a way that is not significantly moderated by the language in which a moral scenario is presented.

Moreover, our participants were immersed in an English-speaking environment. Notably, the MFLE has primarily been observed in late bilinguals who acquired the L2 in instructional settings. Additionally, several studies excluded data from participants who had lived in an L2-speaking country for more than 14 months (Corey et al., Reference Corey, Hayakawa, Foucart, Aparici, Botella, Costa and Keysar2017; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Foucart, Hayakawa, Aparici, Apesteguia, Heafner and Keysar2014; Hayakawa et al., Reference Hayakawa, Tannenbaum, Costa, Corey and Keysar2017), suggesting that long-term L2 immersion can impact executive functioning (see also De Bruin, Reference De Bruin2019) and, consequently, diminish or nullify the effect of language on moral decision-making (Del Maschio et al., Reference Del Maschio, Crespi, Peressotti, Abutalebi and Sulpizio2022). Interestingly, a longitudinal study on highly immersed bilinguals who used both their L1 and L2 on a daily basis found significant structural changes in certain brain areas, resulting in bilinguals’ brains processing information in a similar way to monolinguals’ brains (DeLuca et al., Reference DeLuca, Rothman and Pliatsikas2019). Specifically, DeLuca and colleagues found that after three years in an L2-immersive environment, gray matter density in the left caudate nucleus––a region involved in executive control––decreased, while it increased in the cerebellum, a region linked to cognitive control and processing (see also Pliatsikas et al., 2016, for similar results). Our participants reported having spent between 1 and 70 months in an English-speaking country, with the great majority reporting a length of L2 immersion between 8 and 10 months. We believe that this duration, together with the intensity of their exposure to English (as all participants were studying for or had completed university degrees in English), was sufficient for them to process moral dilemmas similarly in both languages. The combination of these factors, along with our participants’ intermediate to advanced L2 proficiency level, appears to reduce the plausibility of the cognitive enhancement hypothesis as an explanatory mechanism for our findings.

Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that emotional intensity did not have an effect on our participants’ moral judgments. A growing body of research suggests that emotional words and expressions tend to evoke stronger emotional reactions in L1 than in L2, as L1 is usually acquired in emotionally rich and authentic contexts (Dewaele, Reference Dewaele2013; Jończyk et al., Reference Jończyk, Boutonnet, Musiał, Hoemann and Thierry2016; Pavlenko, Reference Pavlenko2012). However, this blunted emotional responsiveness in L2 may diminish in bilinguals who are naturally immersed in an L2 environment (Degner et al., Reference Degner, Doycheva and Wentura2012), as was the case for our participants. Emotional experiences in an immersive L2 environment may approach those felt in the L1, particularly for individuals who are deeply engaged with the language and culture of the host country. In this light, the results of the current study in relation to the language-related variables, as well as the lack of a mediating role of emotion in the relationship between language and moral judgments, do not seem to support the reduced emotionality hypothesis either. At the same time, this should not be taken to imply that emotional processing was identical across languages; rather, it suggests that any potential differences were not detectable through subjective ratings alone.

However, the findings of this study revealed a significant effect of executive functions. Specifically, greater updating ability was associated with a higher likelihood of making deontological choices, regardless of the language in which the dilemmas were presented. Moreover, in their L1, those with greater inhibitory control ability also tended to opt for the deontological option more often. Updating refers to individuals’ ability to remove information from memory that is no longer necessary, thereby freeing up cognitive resources for encoding new, relevant information for the task at hand. In turn, inhibition refers to the ability to suppress impulsive, irrelevant, or automatic responses by controlling attention and applying reasoning. When facing a moral dilemma, people must maintain in memory information related to the situation—for example, the people involved, possible actions, the phrasing of information (e.g., emotionally charged words), and so forth. They also need to process the emotions arising from the dilemma, as well as the emotions they anticipate feeling in the future based on their decision, handle previous experiences triggered by the scenario, and reflect on the potential consequences of their decision for themselves and others. This requires identifying which information is important to focus on while discarding irrelevant details (updating) and suppressing unwanted or impulsive thoughts that may interfere with the task (inhibition)

According to the results of our study, bilinguals with high updating ability made more deontological decisions. This may be due to their ability to hold and update either more relevant information or the same information more efficiently than individuals with low updating ability. In this context, relevant information could refer to the specific details of the dilemma, the emotions arising from it, previous related experiences, moral or cultural values applicable to the situation, potential consequences of immoral actions, or reflections on one’s moral identity (e.g., “Who do I want to be?” and “How can I remain consistent with my moral values”). The amount of information that individuals with high updating ability were able to process and update in working memory might have promoted greater attention to emotions (both actual and anticipated) and to the consequences of making a deontological vs. utilitarian decision. This, in turn, could have also led to rumination, stronger emotional responses, and perhaps even to “emotional vulnerability” (see DeCaro et al., Reference DeCaro, Thomas and Beilock2008; Levy & Anderson, Reference Levy and Anderson2002; see also Mavrou, Reference Mavrou2021). This interpretation aligns with Barrett et al.’s (Reference Barrett, Tugade and Engle2004) observation, that “individuals low in WMC [working memory capacity] may fare better in situations that call for quick actions in negative situations, whereas those higher in WMC may engage in unnecessary deliberation” (p. 566). It also fits well with our finding that individuals with lower inhibitory control who responded to the dilemmas in their L2 tended to make more utilitarian decisions. In other words, a reduced ability to control both attention (i.e., a propensity for distraction) and behavior (e.g., impulsively doing the “wrong” thing such as killing, stealing, etc.) is more likely to lead to utilitarian choices––and this may be particularly true when individuals must use their “(slightly) less dominant” language, in this case the L2.

Limitations and future directions

The current study is not without limitations. First, five dilemmas are far from representative of the type or nature of the dilemmas one will encounter in their daily life. Second, our participants were immersed in the L2 context, which––we believe––has been one of the main reasons why we did not detect the MFLE. Comparing students with linguistically immersive and nonimmersive experiences may thus reveal different patterns of emotional reactions and moral judgments. Third, the multifaceted nature of the psychological constructs evaluated in the current study (executive functions, emotional intelligence) cannot be perfectly measured by means of just one task. For example, emotional intelligence can be conceptualized both as a trait and as an ability; encompassing these two approaches would require the use of both self-report questionnaires and ability tests to capture its many different facets. Similarly, working memory is responsible for a wide range of executive functions, but executive functioning tasks are rarely “pure tasks,” that is, they tap into a wider range of memory processes (Cowan et al., Reference Cowan, Elliott, Saults, Morey, Mattox, Hismjatullina and Conway2005; D’Esposito & Postle, Reference D’Esposito, Postle, Ιn and Schacter2002; Miyake & Friedman, Reference Miyake and Friedman2012; Oberauer et al., Reference Oberauer, Lange and Engle2004, among others). When it comes to decision-making, emotion, and judgment––regardless of whether it is rational or deontological––are more likely to co-exist. In other words, we cannot assume a linear process in which emotion occurs first and leads to a specific decision (or the other way around). To overcome this limitation, future studies could use composite measures of emotion and decision or rely on more qualitative data to obtain a holistic perspective of moral decision-making. A further limitation of the current study is that emotional intensity was assessed solely through self-reported ratings. Although self-reports are widely used in MFLE research, they rely on participants’ introspective access and may not fully capture the rapid, automatic, and implicit components of affective processing that occur during moral decision-making. It is thus possible that subtle emotional differences between L1 and L2 were present in our data but remained undetected because our measures focused on conscious emotional experience rather than physiological or behavioral indicators of processing difficulty, which are commonly provided by online measures such as eye tracking, pupillometry, or other physiological indices.

Furthermore, despite the overall robustness of the statistical models, certain methodological constraints and power limitations must be considered when evaluating the present results. While the sensitivity analyses demonstrated that the findings were robust to model specification, statistical power considerations warrant cautious interpretation of the null interaction effects. With N = 90, α = .05, and power = .80, the study was adequately powered to detect effects of approximately f2 ≥ 0.10. This indicates sufficient sensitivity for medium-sized main effects but limited power to detect the small interaction effects typically observed in moderation and moral judgment research (f2 = 0.01–0.03; Aguinis et al., Reference Aguinis, Beaty, Boik and Pierce2005). Although each participant completed five moral dilemmas—yielding multiple observations per individual and improving precision for within-subject estimates (e.g., language effects)—power for between-subject and cross-level interactions remains primarily constrained by the number of participants. Consequently, the absence of significant moral foreign language effects in the present data should be interpreted with caution. Future research with larger and more diverse samples will be necessary to determine whether these null effects represent a genuine absence of the phenomenon or reflect limited statistical sensitivity.

Another limitation was the imbalance between men and women. The majority of our participants were women. Previous research has shown gender-related differences in moral decision-making, with men opting for utilitarian choices more frequently than women (Friesdorf et al., Reference Friesdorf, Conway and Gawronski2015; Fumagalli et al., Reference Fumagalli, Ferrucci, Mameli, Marceglia, Mrakic-Sposta, Zago, Lucchiari, Consonni, Nordio, Pravettoni, Cappa and Priori2010). Nonetheless, gender was not the main focus of the current study. Moreover, some recent studies reported the presence of the MFLE both in samples with a predominance of women (Białek et al., Reference Białek, Paruzel-Czachura and Gawronski2019; Cipolletti et al., Reference Cipolletti, McFarlane and Weissglass2016) and those with a predominance of men (Kyriakou et al., Reference Kyriakou, Foucart and Mavrou2023; Kyriakou & Mavrou, Reference Kyriakou and Mavrou2023b). Therefore, we consider that the gender ratio in our sample does not compromise the validity of our findings.

Lastly, an important number of individual differences in personality, identity, and related domains have been left aside. Therefore, future work should examine more thoroughly the long list of other relevant variables, such as moral and cultural identity, empathy, critical thinking, and decisiveness, among others. In particular, moral and cultural identities deserve further attention. A recent study has shown that bilinguals with stronger moral identities tended to make more deontological choices regardless of the language they used (Mavrou et al., Reference Mavrou, Mavrou and Kyriakou2025). Moreover, the MFLE is diminished when bilinguals are immersed in L2 culture. This is the case for Swedish–English bilinguals living in Sweden––a country where English has a strong cultural influence (Dylman & Champoux-Larsson, Reference Dylman and Champoux-Larsson2020)–– and for Greek–English bilinguals living in Cyprus (Kyriakou & Mavrou, Reference Kyriakou and Mavrou2023b)––an island that was under British rule for 82 years and where English continues to play a dominant role. How the formation of L2 identities (moral, cultural, social, etc.) impacts moral judgments and emotions provides a promising avenue for future research.

Conclusion

This study investigated moral decision-making in Chinese–English bilinguals by focusing on the complex interplay between language, emotional intelligence, and executive functions. Updating and inhibition significantly influenced moral judgments, leading to more deontological decisions, particularly in L1. Nonetheless, we did not find evidence supporting the MFLE. These findings highlight the variety of factors that determine bilinguals’ moral choices. Overall, the MFLE is too complex to be considered a universal phenomenon applicable to all bilinguals. Bilinguals differ in their personality, cognitive abilities, and language-related experiences, and therefore moral decision-making cannot be explained solely by a single variable, such as language.

Data availability statement

The experiment in this article earned Open Data, Open Materials and Pre-Registered badges for transparent practices. The materials used in this study, together with the anonymized dataset and analysis code, are available on the Open Science Framework (OSF): https://osf.io/sr9j5/.