When we think historically about the mortgage business in North America, what usually comes to mind are banks, insurance companies, and Savings and Loans. These are key elements in what may be understood as “deposit-based systems,” one of the three modern types of mortgage finance that have evolved in the western world.Footnote 1 Then, perhaps, we might think of the brokers and agents who handled mortgages for others. What historians acknowledge last, if at all, are the millions of private individuals who comprised the type that the others transcended.

This “direct finance,” or “personal sector,” arrangement has a low profile in historical records. Most individuals had no office beyond a desk in a corner of the living room and did not think of themselves as businessmen—or -women. With limited capital, most held only one loan at a time.Footnote 2 Yet, collectively, they mattered a lot. On one measure, in the US, and probably in Canada, individuals’ share of the residential mortgage market in 1901 was about half. By 1961, shaped by federal programs, it had declined markedly, to a 3rd in Canada and a 10th in the US.Footnote 3

Who were these people, and what loans did they make? Contemporaries offered general and varied answers, and no overall assessment. We know fragments about the types and terms of the loans they offered, less about the properties they financed, and almost nothing about who they helped. Worse, contemporaries made contradictory statements about who these investors were. In the 1940s and 1950s, the National Bureau of Economic Research published studies of the major lending institutions in the US but no one, then or later, has attempted anything similar for the personal lender. Elsewhere, I have outlined the decline of this sector in North America, including the role played by the federal governments.Footnote 4 The purpose of the present paper is to explore in depth the nature of the personal lending business: to gather and assess what we know about who those lenders were, the types of loans they made, and on what terms, from the 1890s through the late 1950s. To that end, it draws on occasional national surveys, contemporary commentary, and available case studies, while presenting new evidence for Toronto, and especially, Hamilton, Ontario.

This evidence makes it possible to reconstruct, in turn, the types of loans that individuals provided, how they connected with borrowers and, finally, who those borrowers and lenders were. Most of the loans were “straight”—unamortized—and short term; an increasing share were junior and therefore riskier; some were for construction. Lenders and borrowers might find one another through family, work, or ethnic networks and, if not, then via professional brokers. In many cases they encountered each other as buyer and seller, with the latter providing the primary or second loan. Initially, both borrowers and lenders included many women, as well as men, in a wide range of occupations, but over time the range narrowed. By the 1950s, borrowers were more likely to be minorities, to have modest incomes, and to take out relatively small loans, while lenders were stereotypically professionals, especially in real estate. Over time, loans and agents in the “personal sector” were marginalized. Instead, assisted by federal policies in both countries, mortgage lending became more professional and institutional, supporting the emergence of secondary markets that connected mortgage investing with larger capital markets.

To reveal important parts of that story, Hamilton serves as well or better than most places.Footnote 5 As the fifth-largest city in Canada, growing from 53,000 in 1901 to 274,000 in 1961, it offered wide opportunities to private investors. Individual lenders were more numerous in Canadian than American cities but, even there, Hamilton stood out. In the early 1900s, they provided 80–90% of the mortgages on residential property.Footnote 6 On single-family homes, the proportion hardly varied between owner-occupied and rental properties, which were about equal in number.Footnote 7 From then onward, Hamilton acquired small and mid-sized apartment buildings. Altogether, it supports a detailed exploration of the types of loans with which private individuals were involved.Footnote 8

That said, no claim can be made that Hamilton was typical. At most, and when compared with available evidence for other North American cities, it narrows the range of probabilities. Many gaps in knowledge remain, the more prominent being discussed in a brief conclusion.

Individual Loans on Residential Property

Certain features of the loans offered by individuals persisted throughout the period of decline: the nature of demand for home purchase and construction; the reasons for individuals to lend; and the nature of the risks they faced. Each is considered in turn.

Those hoping to buy or build usually needed to borrow money. Homes cost a lot, and apartment buildings much more—many times most peoples’ incomes or, usually, their savings. Most lenders want substantial loans to be registered against title, but not always. The major loan is usually a first mortgage, with priority in foreclosure. Until the 1930s, no lenders in either country offered high-ratio loans: Except for American Building and Loans, anything more than 60% was rare. Without inherited wealth, you might have to save for decades before buying in your forties or fifties. The alternative was a second mortgage, which, with lower priority and greater risk, commanded a higher interest rate. Cautious, or unscrupulous, lenders provided land or sales contracts, retaining the title until the borrower had paid off much of the loan.Footnote 9 However, trusting mortgagees (lenders), perhaps friends or family, might accept a written but unregistered contract. Loans on existing properties, then, took various forms.

Then, there was financing for construction. Before World War II, subdividers offered land contracts, and buyers often had to repay the full amount before receiving the title.Footnote 10 For actual construction, diverse arrangements were made. Suppliers offered unsecured credit, often with a 30-day term. Contract builders asked clients for a series of lump-sum payments, and customers looked for help. Here again, then, were demands for various short- and long-term funds. All attracted personal lenders. No one has documented the full range of options or tracked trends. At best, we can sketch magnitudes and trajectories.

What was the appeal of residential investment? Some lenders obliged a friend or family member, but all supposed their investments made sense. Why? In 1912, in a YMCA handbook, G. Richard Davis offered three reasons. Already a builder in New York, Davis knew the business. He judged that first mortgages offered good security, stable income, and relatively high interest. In his Treatise on Mortgage Investments (1892), Edward Darrow had already emphasized Davis’s third reason, adding that lenders liked local investments because they were “subjected to his personal examination.”Footnote 11

For late nineteenth-century Boston, Sam Bass Warner offered additional reasoning. He endorsed local knowledge: “small investors could easily acquire a fairly expert knowledge of the part of the metropolitan area in which they lived.” Then, noting the “wide range of options” available, he emphasized the ability to place funds in the “moderate quantities” that most investors possessed. Noting that second mortgages were riskier, he suggested that “by this device of two mortgages the market divided itself into two groups: the speculative investor and the conservative.”Footnote 12 True, but simplified. In fact, risk varied depending on the borrower’s income and reliability, the character and location of the property, and the size and ratio of the loan. Loans on real estate offered a long risk menu.

Risk also varied with the market. During the late 1920s, optimism reigned, but the Depression sobered everyone. Contrary to common belief, the foreclosure rate on individuals’ loans was lower than institutions’, perhaps because some were with family, but it still crippled many.Footnote 13 Repossessions were often unsaleable. Even in Canada, where foreclosures had less effect on the financial system than in the US, by 1940, H.R. Jackman, the past president of Empire Life, offered only cautious optimism. Noting the long-standing assumption that “… the small first mortgage on improved real estate” was “the bed rock on investment values,” he suggested that “it is likely … that [it] will again assume its popularity.”Footnote 14 To market-watchers, his silence about junior mortgages was telling. More specific guidance was offered in 1947 by Canadian journalist Lillian Millar in her column on “women and money.” She noted the cautions highlighted by recent experience: municipalities’ tax claims had priority over mortgages; moratoria hobbled foreclosure; and careful appraisals were vital.Footnote 15 Here, Millar’s comments echo the one caution Davis had offered in 1912: the perennial challenge was to obtain an accurate appraisal.

During the early postwar boom, Depression memories faded, and many resumed lending on residential property. Others, however, preferred new investments. Bonds, some based on real estate, appealed because they were available in small denominations, while risks were spread. By the early 1960s, a Canadian survey found that, while 5.8% of people held mortgages, 29.1% owned bonds.Footnote 16 Mortgages were losing their appeal.

Types of Loans

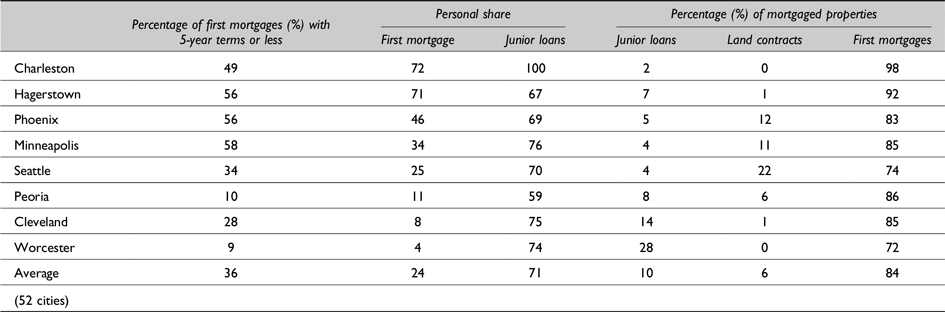

As Jackman suggested, the “bed rock” loan was the first mortgage. It was the safest type and the largest, individually and collectively. It is only in 1934 that we can weigh them against their junior cousins. The Financial Survey of 52 cities across the US found that 84% of the debt held by individuals on owner-occupied homes was for first mortgages, while the balance was for junior mortgages. Given that they were smaller, in number, the junior loans might have accounted for at least a fifth of the total.Footnote 17

The average hid variations (Table 1). Housing markets were hyper-local, in employment, housing demand, sources of funds, and dynamics.Footnote 18 Across those 52 cities, individuals’ share of first loans averaged 24% but ranged from 72% in Hagerstown, Maryland, to 4% in Worcester, Massachusetts.Footnote 19 The balance also varied. In Cleveland, for example, the largest city in the Survey, individuals held only 8% of first mortgages, and junior loans were unusually common (14%), and in Worcester, Massachusetts, they were rampant (28%). Generally, where institutions dominated first loans, individuals looked to junior finance. This helps to explain trends. As the personal sector declined, it was relegated to smaller and riskier loans.

Table 1 The Source and Character of Mortgages on Owner-Occupied Homes, Selected Cities, US, 1934

Source: Calculated from estimates reported in David L. Wickens, Residential, Tables D15, D17, and D24

Increasingly, the terms that individuals offered were criticized, notably by federal agencies such as the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which promoted long-term, amortized, high-ratio loans. In contrast, individuals—along with several lending institutions, notably commercial banks—favored short-term, “balloon” arrangements. In Peoria, Illinois, in 1934, institutional loans dominated, and so only 10% had 5-year terms or less (Table 1). However, among those provided by individuals, the proportion reached a third, while two-fifths were “straight.”Footnote 20 Infrequent payments only covered interest, leaving the principal unaffected. A survey found that 28% of Buffalo’s borrowers believed they had “unlimited” terms, but local agents indicated these simply had nominal “automatic renewal.”Footnote 21 A recent study of Baltimore confirms that extensions were routine but not guaranteed. Individuals were cautious, rarely offering over half the appraisal. That is why the junior loans—damned by Frank Watson at the FHA as a “racket”—were common. None of this fit the progressive narrative about mortgage finance promoted at the time, and which historians, in Canada and the US, have endorsed.Footnote 22

The promotion was not just verbal. In the US, from 1934, the FHA offered loan insurance exclusively on longer-term, amortized loans on property that met its requirements. Standardized, these loans became marketable. From 1938, the Federal National Mortgage Association (aka Fannie Mae) created a secondary market, connecting mortgages with wider capital markets. Personal loans, secured on properties that ranged in quality and with terms that varied greatly, were left out, contributing to their decline. The FHA loans appealed to middle-class buyers who could afford FHA standards. From 1935, under the Dominion and then National Housing Acts, Canada moved slower. However, its government took a key step in 1954 when federal insurance was offered, and Bank Act revisions brought this institutional player into the market.Footnote 23 Federal policies pushed personal loans aside.

Junior mortgages

Experts redoubled criticism of the personal loans made for junior liens: the need for them and their effects on borrowers and the financial system. “Racket” implied exploitation. For the Temporary National Economic Committee in 1940, Peter Stone and Harold Denton suggested that during the 1920s providers of junior loans “sometimes” charged up to 10% interest, with a “substantial commission.”Footnote 24 Supposedly, such arrangements had contributed to the mortgage crisis of 1929.

Junior loans had only recently become integral to the market. Until the 1900s, debt was viewed skeptically, often as immoral. Looking back, in 1959, the president of Central (now Canada) Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), Canada’s housing agency since 1946, observed that “a mortgage was once shameful.”Footnote 25 Perhaps, but buyers had treated them as necessary. However, the early twentieth century saw a shift, with junior loans becoming more widespread. In the US, between 1890 and 1920, the proportion of homes with mortgages jumped from 28% to 38%. In the same period, a case study indicates that junior loans became common. In Columbus, Ohio, they accounted for only 1.7% of all mortgages in 1900 but reached 25% by 1926. The Depression reversed this trend. Their share dropped to 7.4% in 1934, somewhat lower than the national average (Table 1). It stayed low through 1940.Footnote 26 However, junior loans were a growing feature in the century’s first three decades.

Their critics, including Alexander Bing, President of New York’s City Housing Corporation, noted that extra loans meant extra costs.Footnote 27 Their risk to lenders was widely acknowledged, and real. In Middletown, Connecticut, annual Depression-era default rates on second mortgages (5.6%) were much higher than on first mortgages (1.3%).Footnote 28 Indeed, it is surprising that providers did not charge more. The Financial Survey reported that their average contract rate in 1934 (6.44%) was barely higher than for first mortgages (6.18%).Footnote 29 Most lenders did not exploit; they were simply part of a system of which many disapproved.

After 1945, critics became skeptics. For Los Angeles ca. 1950, Fred Case noted criticisms but found that interest rates were “not unusually high” and that repayments were “excellent”; in Middletown, Connecticut, defaults were rare.Footnote 30 In both cities, as in Columbus, junior loans had almost disappeared with the Depression but rebounded somewhat after 1945. That also happened in Canadian cities, including Hamilton.Footnote 31 The Depression’s legacy meant few borrowers had large downpayments, but rising incomes and low interest rates covered two loan payments, in effect a high-ratio mortgage. Similar to the insurance on high-ratio FHA-approved loans, junior loans still enabled once-marginal buyers to buy homes.Footnote 32

One charge leveled at the mortgage system until the 1930s was the weak secondary market. In 1929, a survey noted, “there is no open market or exchange for mortgages,” and that arrangements for junior liens were “disorganized.”Footnote 33 In 1939, Fannie Mae tried to rectify this. Canada was slower: Only in 1961 did CMHC try “to stimulate the development of a secondary mortgage market.”Footnote 34 Some local exchanges handled junior mortgages, rating them “A” through “D”; by 1957, one in British Columbia had enrolled 200 investors.Footnote 35 Unfortunately, dodgy practices persisted. Most brokers had long been competent, responsible, and professional. However, well-publicized cases of “unconscionable transactions” prompted Ontario to compel brokers to register and to keep complete records.Footnote 36 There was always scope for exploitation.

Inevitably, the use of junior mortgages varied greatly from place to place. In the 1930s, fully 57% of mortgagors in Buffalo had two or more mortgages; in Minnesota, only 7%, although another 37% had a first mortgage and a contract.Footnote 37 Again, the Financial Survey provides context: in 1934, across 52 cities, 9.7% of owner-occupiers with first mortgages also had a second; on rented properties, 6.7%. The level remained significant. The 1950 US census reported that 8.7% of mortgaged single-family homes had a junior lien.Footnote 38 However, the level was declining, at least in the US. In Middletown, Connecticut—admittedly, untypical—20–28% of mortgage money in the 1920s went to second mortgages, but by the early 1950s, only 1–5% did; third mortgages had disappeared.Footnote 39 In postwar Canada, juniors persisted, along with lower-ratio first mortgages. In the late 1950s, a correspondent claimed that their market share was surging “to the point that it equals that of conventional lending.” That is doubtful.Footnote 40 In time, as Lawrence Smith suggests, second mortgages had become largely “residual” by the 1970s.Footnote 41

Second mortgages could count for a lot. In Buffalo, in the early 1930s, homeowners with mortgages reported that, on average, junior loans covered 25% of the purchase price. Stone and Denton suggested that this had been typical. The Financial Survey’s evidence is not comparable, but it reports that the average size of original first mortgages had been US$3,316 and of junior loans US$1,854. Assuming first mortgage ratios of 40–50%, juniors covered 22–28% of the purchase price.Footnote 42 They enabled many renters to buy, while adding risk to buyer and lender alike.

They deserve our attention because they came mostly from individuals—in Peoria in 1934, 60% and, in Cleveland, 75%.Footnote 43 If anything, their dominance increased. Nationally, in 1950, individuals held 69% of all junior mortgages, 73% by value. In Middletown, Connecticut, in some postwar years, the proportion reached 100%.Footnote 44 Some institutional lenders, including savings banks and insurance companies, were forbidden from offering them.Footnote 45 Others, notably Building and Loans, did so only if they held the first mortgage. This was a type of mortgage strongly associated with the personal sector.

Construction mortgages

Loans were needed for building, as well as for buying. Those for construction were a mess. In the 1930s, one survey suggested that the “system of finance” was “outworn.” In fact, there was no system. As Leo Grebler, a leading real estate economist, observed in 1950, “there is no distinct production financing in the construction of housing.” Recently, one of Senator Langer’s constituents in North Dakota had pleaded, “I would like to know just what one has to do to get a loan to build a house, and who I would have to see …” Langer forwarded the letter to Raymond Foley, Administrator of the Housing and Home Finance Administration. There was no simple answer.Footnote 46

Producer and consumer credit were “intertwined,” while varying between contract and “operative” builders, those who built on speculation.Footnote 47 The situation was further confused because some builders operated either way, depending on the market.Footnote 48 Custom builders were small and more common. In 1949, the first year with good data, 42% of all builders erected 1 house a year and 90% 10 houses or less. In Canada, “small builders have been more prominent.”Footnote 49 Except during boom periods, they relied on subcontractors and had few assets.Footnote 50 Small ones owned a truck and some tools, while their wife kept accounts. Larger ones had a small office, perhaps employing someone for marketing and finance.

Both relied on finance but in different ways. Custom builders’ arrangements varied. The prospective homeowner might acquire a lot from a subdivider or an investor: lots changed hands several times before being built upon. Across five suburban subdivisions around Toronto, 1900–1940, subdividers provided 10% of the loans for land sales, while individuals picked up 70%, more for the cheapest lots.Footnote 51 If financed, the vendor often used a land contract, retaining title until most, often all, of the loan was repaid.Footnote 52 In Hamilton, Ontario, “easy payments” were common by the 1900s.Footnote 53 It is unclear how common land contracts were, or sales contracts for completed homes. Most went unregistered. The Financial Survey found that 6% of owner-occupied homes with debts in 1934 had such contracts but, again, the incidence varied enormously by city and region.Footnote 54 By then, they were rare on the East Coast, unusual in the Midwest, and common in western and southwestern cities such as Phoenix and Seattle (Table 1). Overall, about half were provided by individuals: in Cleveland the proportion was 43% and in Peoria 59%.Footnote 55

To build, clients paid builders retainers and then lump-sum payments as construction proceeded. He (rarely she) might obtain an initial consumer mortgage from a lender, or else borrow for each payment. Sometimes builders took out the full loan. Meanwhile, they routinely obtained open-ended 30- or 60-day finance from suppliers, some of whom offered mortgages.Footnote 56 The homeowner might borrow from family or friends, offering written but unregistered agreements in return. These were only the more common possibilities.

Larger, speculative builder-developers needed more finance, obtained in various ways, rarely from individuals. Some formed syndicates and others used lending institutions or sold deeds to a broker who resold to clients.Footnote 57 Arrangements changed when the FHA offered preapproved mortgages, as shown by studies of San Francisco and Jacksonville, Florida, soon after 1945.Footnote 58 Sherman Maisel’s work on San Francisco is the richest study. There, “merchant” builders used six banks, a savings and loan company, two insurance companies, and three mortgage companies, but “a different picture is found when we consider … houses built by owners, contractors, or the smaller operative [speculative] builders”; here, a “third were financed by the owners entirely with their own funds.”Footnote 59

It is the case study of Jacksonville, however, that gives the best picture of early postwar individual lenders. It found that 11.2% of all individual loans went for construction, constituting 8.6% of the value of such loans.Footnote 60 While the modal price range from other sources was US$4,000–4,999, individuals concentrated on properties under US$3,000. This pattern was probably typical, but the overall role of individuals in housebuilding was greater than that. Many of their loans went unrecorded, especially as contracts. Then again, in that period, Jacksonville was exceptional in its reliance on FHA-backed institutional sources, now playing a larger role than ever. A study of Omaha, Nebraska, 1880–1920, found that those lot owners who wished to build relied on individuals for funding.Footnote 61 For individual investors, construction finance was less important than consumer loans, but it was still a significant option.

Connecting Sellers, Buyers, and Investors

In any business, bringing buyers and sellers together is essential, and in the housing market, lenders are usually also involved. Sales involved a triangle of agents, in two stages: owners searched for buyers, and then buyers sought lenders. Both stages could involve informal arrangements instead of professionals, especially where individual lenders were involved.

Vendors found buyers in various ways. Contacts with family members, neighbors, friends and acquaintances, co-religionists, and coworkers could yield a possibility, perhaps through social networks such as extended family or friends of friends. Commonly, they advertised, posting “for sale” notices or newspaper classifieds. Increasingly, however, vendors used real estate agents. These become respectable in the 1880s and then important in the twentieth century. From the 1910s, in both countries, self-styled “realtors”—from 1915 a brand-name—adopted a professional code of conduct, while local associations ran multiple listing services.Footnote 62 Increasingly, realtors directed buyers to institutional lenders; those that were diversified offered loans. However, at first, and for people or properties that institutions avoided, they pointed buyers to people with capital, or who were keen to sell.

Even without an agent, most buyers could find an institutional lender. These had local offices and visibility. But how to find someone with spare capital? Buyers’ social networks were often important. In 1923, in a homeowner manual, an instructor at Columbia University’s School of Architecture suggested that “some [borrowers] will have very close friends from whom they can secure a large first or second mortgage.”Footnote 63 Three decades later, in San Francisco “lending [was] probably confined to the general area in which the lender resides and in many cases to his immediate circle of relatives, friends, and acquaintances”; in Jacksonville, a quarter of conventional mortgages came from “a relative, friend, or business connection.”Footnote 64 The same held true in Canada. In 1950, the boss of CMHC’s Mortgage Division mentioned a mother who had loaned her son Cdn.$1,000 and a bank worker whose employer provided funds on a personal note.Footnote 65 A reporter in Hamilton, Ontario, suggested “three possible sources” of mortgage loans. The first was “a relative or private individual.”Footnote 66 Moreover, as in San Francisco, private lenders were local. The Hamilton sample shows that, in the forties and fifties, more than 9 out of 10 lived in the city or its suburbs.Footnote 67

Racial or ethnic networks were useful. Around 1900, Baltimore immigrants loaned each other money, directly or via associations. As late as 1970s Toronto, Italian and Portuguese immigrants appreciated the “convenience and comfort” of using co-nationals. In Ayars Place, a Black enclave in Evanston, Illinois, individuals provided two-thirds of mortgages in the 1920s. Some came from the Black community, while white employers made loans to servants.Footnote 68 In general, African Americans relied more on individual loans than white individuals. Nationally, in 1940, among owners of single-family non-farm homes, the proportions were 31% and 25%, respectively.Footnote 69

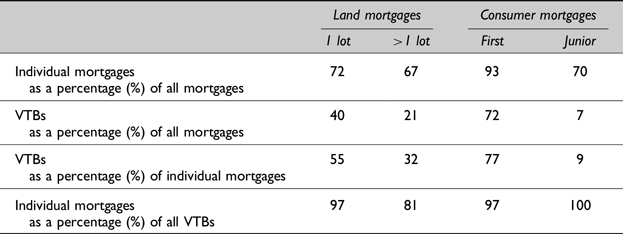

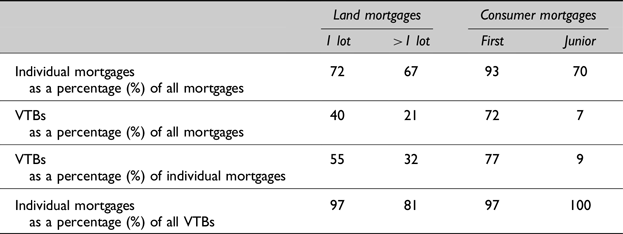

One person who had capital was the vendor. “Purchase money,” or “vendor take-back” (VTB) mortgages, were common through the 1950s and, in some places, beyond. They were usually registered, but there are no national data on their prevalence. Local studies are consistent. In nineteenth-century Hamilton, 54% of mortgages came from the vendor; late in that century, VTBs were prominent in Baltimore, too.Footnote 70 They remained common, comprising 35% of registered mortgages in Hagerstown, Maryland, in 1927.Footnote 71 Detailed evidence is available for Toronto (1900–1940). There, in five suburban subdivisions, VTBs comprised 77% of the consumer loans made by individuals and, given the prominence of individuals, 77% of all first mortgages (Table 2). Not surprisingly, individuals were, overwhelmingly, their main source, both for first (97%) and for junior (100%) mortgages.

Table 2 Vendor Take-Back (VTB) Mortgages in Five Toronto Subdivisions, 1900–1940

Source: Compiled and calculated from Ross Paterson, “Creating Suburbia,” (Unpubl. Ph.D. diss, York University, 1988), Tables 37, 38, 43, and 44

Vendors remained a major source of first and junior loans beyond 1945. In San Francisco, 1949–1950, their share was 45%.Footnote 72 Then, 4 years later, a similar share was apparent for first mortgages across four Canadian provinces.Footnote 73 VTBs were common among junior loans, too. In Los Angeles, these were “typically” vendor-provided; a Canadian newspaper suggested the same.Footnote 74 Indeed, their role in Toronto’s central city was striking. Even in the late 1970s, 32% of first, and 68% of second, mortgages were VTBs.Footnote 75

Vendors also offered credit for land sales. This had a long history. In antebellum Boston, once land had become “a general commodity freely bought and sold … mortgages were often granted by sellers, but rarely by banks, wealthy urban investors, or corporations.”Footnote 76 Through the 1920s, vacant lots were bought and sold several times. Speculators offered land contracts or mortgages. In Toronto, across those five subdivisions, whether on single or multiple parcels, individuals provided more than two-thirds of the loans (Table 2).

Why did vendors lend to buyers? Sometimes they were helping someone they knew. Generally, they wanted to seal the deal. Perhaps the market was slow, or their property was a fixer-upper. They offered favorable terms. In Canada in 1954, they were charging 6.0% interest, below the prevailing rate of 6.4%, while offering an average term of 5.7 as opposed to 4.6 years and a loan ratio (47%) higher than other individual loans (41%).Footnote 77 Perhaps they were ill-informed about market conditions, contract details, and risk, a common charge against individual lenders. In Hagerstown, “many … were only vaguely familiar with the mortgage terms.”Footnote 78 After all, the vendor was often a first-time mortgagee. However, as any seller would, maybe they reckoned easy terms were a way of getting a good price with minimum delay.

In such deals, trust was essential. The lender wanted assurance that the borrower would maintain payments. That came in part from the character of the borrower, which the vendor would have observed as the two negotiated the sale of the house. What also helped was their embeddedness within larger social networks, so that a default would face social sanctions.Footnote 79

But how to judge a stranger, someone you might never meet? In 1931, individuals held 79% of all mortgages in Hamilton, Ontario, and one homeowner’s daughter recalled that in the 1920s “most lenders were strangers.”Footnote 80 Here, “your real estate man,” a professional broker, was crucial.Footnote 81 In early postwar Jacksonville, almost half of those who did not use a social network relied on a broker. They followed his advice about the type of loan as well as the lender.Footnote 82 Traditionally, brokers were lawyers, mostly male, many reliant on the real estate business and with “keen knowledge of the market.”Footnote 83 Informed observers would have agreed with a New York builder that “a borrower can rarely serve his own interests as well … as by employing a professional mortgage broker,” who has contacts and knows deal-making (for a half percent commission).Footnote 84 The crucial contacts were investors, who brokers located through business networks, newspaper ads, and personal letters, followed up with in-person interviews, in the office or the client’s home.Footnote 85

As Kenneth Snowden has observed, brokers needed “credibility” with both vendor and borrower; “to be familiar with local real estate conditions” they needed to live locally.Footnote 86 Commonly, they collected payments. The owner of a Cleveland agency commented that “… a small office … can maintain a personal touch with the borrower,” encouraging “a more humane treatment” regarding arrears.Footnote 87 To reassure lenders, in Hagerstown, “all … borrowers were chosen on the basis of personal acquaintance or a very high recommendation.” There, typically, some brokers would “invest personal or family savings, or recommend friends interested in making real estate loans.”Footnote 88 Larger real estate companies, such as Hamilton’s Moore and Davis, coordinated various activities, thereby “reinforcing notions about trustworthy behaviour or desirable shelter.”Footnote 89

In the US, mortgage banks disturbed these cozy arrangements. Larger brokers compiled and distributed lists of mortgages available for purchase while showing investors how to evaluate their options.Footnote 90 Slowly, by the 1920s they had evolved into what Frederick Babcock, who designed the FHA’s appraisal system, referred to as “modern mortgage companies.”Footnote 91 In the 1950s, when Babcock was writing, another transformation made “a new type” of mortgage company dominant, one servicing lending institutions.Footnote 92 Nothing similar to it happened in Canada, where, from 1954, nationally-chartered banks originated their own loans. In both countries, local brokerages persisted but slowly declined as the institutions’ share of the mortgage market grew.

The Borrowers: People and Properties

If, helped by agents and brokers, individuals made various types of loans, who benefitted, and on what sorts of properties? Two considerations nudged lenders in particular directions. First, because most had limited funds, their significance for multi-family buildings was limited: In Hamilton in 1931, their share of financing for apartment buildings was 20 percentage points lower than for single-family dwellings.Footnote 93 A second nudge was that institutions avoided certain types of loans, properties, locations, and people. Individuals did not have to fill those gaps, but without competition they had an incentive. These are general expectations. Little is known about the borrowers. Here, the case study of Hamilton has most to contribute. The methodology has been described elsewhere, along with some relevant results.Footnote 94 These have been, and will be, cited here where appropriate.

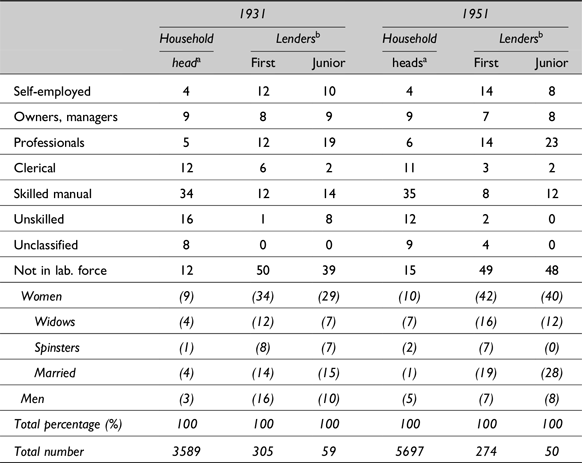

Hamilton illustrates the potential variety of people to whom individuals made loans. In 1931, these included women, as property owners and heads of households. In Britain and North America, by 1900, many women owned residential property.Footnote 95 The Canadian evidence is striking. In 1901, the census showed that 17% of the houses in Canada were owned by women, while in Hamilton, 6.5% of women owned property, and in Victoria, British Columbia, 12.3%.Footnote 96 Changes in dower laws had been crucial, allowing women’s share of property ownership in Guelph, Ontario, to rise from 7% in 1851 to 19% in 1901.Footnote 97 Many women, then, needed to borrow, and the number increased. In Hamilton, by 1931, 42% of the women who headed households owned their own home, and collectively, they owned 10% of owner-occupied single-family dwellings.Footnote 98 Almost two-fifths had mortgages, many being provided by individuals. Meanwhile, individuals were lending to men in all sorts of occupations. The occupational distribution of their mortgagors was almost identical to that of institutional lenders. The only exception was a slight underrepresentation of the self-employed (9% versus 11%) as well as managers and professionals (16% versus 20%).Footnote 99

However, even by Canadian standards, Hamilton had a large personal sector. When and where that share was smaller, its role was more particular. In Hamilton, by 1951, that sector’s share had fallen to 61%, and individuals were much less likely to be lending to managers and professionals (11% versus 28%) and much more likely to fund unskilled workers (17% versus 6%).Footnote 100 Such bias was surely typical at other places and times. Certainly, the available evidence indicates that individual loans were important for two low-income groups: immigrants and African Americans. In nineteenth-century Baltimore, as in 1970s Toronto, and surely scores of other communities in between, immigrants helped each other out.Footnote 101 The same held true for African Americans, but their incomes were still lower and, although some built their own homes, fewer were in a position to acquire property.Footnote 102

Until the 1950s, and beyond, lending institutions made few loans to African Americans. Historians debate how much this reflected racial discrimination, as opposed to lower incomes or an avoidance of the poorer neighborhoods where most African Americans lived. For San Francisco, from 1949 to 1950, Paul Wendt and Daniel Rathbun were well-placed to judge, concluding that “the fact that the majority of Negroes live in blighted areas” was the primary cause.Footnote 103 This is consistent with what Helen Monchow found in the prewar era. Regardless, when African Americans took out mortgages, they relied on private lenders. Most lenders were probably well intentioned, but as Beryl Satter has shown for Chicago, after 1945, speculators used contracts to exploit Black home buyers. These were common and egregious enough that Ta-Nehisi Coates, a prominent author and journalist, has recently used an example to build his case for reparations.Footnote 104

A lower-income bias fits the properties and places where personal loans were prominent. Such loans were smaller because so many were junior mortgages, but even first mortgages were relatively modest. Until the Depression, the difference was slight. In the mid-thirties, the original debt on mortgages from individuals (US$2,985) averaged only slightly lower than that on those provided by Building and Loans (US$3,086). It was the insurers’ upmarket bias (US$4,891) that brought the institutional average to US$3,318.Footnote 105 As a New York researcher commented, bias “has enabled them to avoid the competition which is so keen among individuals and small institutions for mortgages in the more moderate brackets.”Footnote 106 The Depression triggered the split. In 1940, 21% of personal sector loans were for single-family properties worth less than US$1,500. The proportion for all other lenders was only 9.2%.Footnote 107 Competition at the lower end of the market was waning.

The shrinkage of individual loans gained momentum after 1945. In Hamilton in 1931, their average value was 96% of the city-wide average. This slipped to 94% in 1941 and 88% by 1951.Footnote 108 Everywhere, personal lenders were being shouldered out of the middle and upper segments of the market for new homes. In booming Jacksonville, only 57% of the first loans provided by individuals were for more than US$2,000, but the proportions for insurance companies (79%) and now Savings and Loans (94%) were much higher. Individuals provided 13% of all mortgages but only 7% by value; Hagerstown showed a similar pattern, as did Ontario in the late 1960s.Footnote 109 Individuals were being pushed to the margins.

“Margin” had geographical expressions. Especially in the US, this meant “inner city.” In New York, banks avoided older homes, or new ones in older neighborhoods.Footnote 110 In Middletown, Connecticut, it was older homes that required junior mortgages from the personal sector.Footnote 111 In the 1930s, when the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation and the FHA rated neighborhoods from “A” to “D,” most “Ds” were centrally located. By the 1960s, a similar geography was apparent in Canada.Footnote 112

From the 1930s, federal policy in both countries favored institutional lending on new homes.Footnote 113 FHA and Canadian Dominion Housing Act (DHA)/National Housing Act (NHA) mortgages were only offered to institutions; inevitably, David Mansur, the chief inspector of mortgages for Sun Life, Canada’s largest lender, was appointed as CMHC’s first president. That is when personal loans went into rapid, permanent, decline. On one measure, in the US, their role in financing one to four family homes fell from 29% in 1945 to just over 8% in 1960. The Canadian decline was gentler, from 44% to 34%, and from a higher start.Footnote 114

In general, fewer suburban properties carried personal loans, but for a time there were significant exceptions. One, which was short-lived, was second mortgages on conventional loans, as in Los Angeles.Footnote 115 Another reflected the way federal agencies and lending institutions were wary of some outer districts. There had long been settlements in unserviced fringe areas. Much involved owner-construction, requiring little finance.Footnote 116 Hamilton’s Union Park, developed from the 1900s, was one example.Footnote 117 Institutions avoided such places. In Hamilton in 1931, the two settlement rings with the lowest proportion of institutional loans were those adjacent to the downtown core and at the suburban fringe. By 1951, institutions favored a few suburbs, leaving the working-class eastern fringe to the individual lender.Footnote 118 In Canada, however, it was Alberta that offered prime territory for postwar unplanned development, as Calgary and Edmonton boomed; in the US, no place saw more of it—and was better documented—than Flint, Michigan.Footnote 119

For a decade, unplanned development was common, eroding when services and building regulations were extended outward. In various ways, then, individuals were left with investments that institutions avoided: junior loans and land contracts, mortgages for families with modest incomes, and cheaper properties in risky inner city or unserviced suburban districts. So, who were the people willing to take such risks?

The Lenders

By definition, lenders had capital to invest, and those best equipped to hold mortgages had work that paid well. It turned out, however, that that was not the only qualification.

Many contemporaries agreed with A.D. Theobold, soon-to-be staff vice president of the US Savings and Loan League. In a survey of American subdivision development in the 1920s, he wrote that “the successful business or professional men” were the “usual sources of capital.” Canadian Charles Fell, President of Empire Life, agreed: “of course the individual we are concerned with is not the ‘average individual.’” Similar reports persisted after 1945. In Hagerstown, apart from vendor take-backs, the main individual lenders were professionals, especially real estate lawyers.Footnote 120 More generally, in the early 1960s, a Canadian survey found that lawyers, notaries (in Quebec), and construction contractors were prominent; the proportion of people with mortgage investments was higher among clerical workers (18.4%) and professionals (15.6%) than in the population as a whole (6.5%).Footnote 121 No surprises here.

However, age also played a part. Thrifty, steadily employed workers saved for retirement. Then, they looked for steady returns. In 1933, during a moratorium in Ontario that inhibited foreclosures, a letter writer defended those who had invested “hard-earned savings,” including “widows and children” along with “old men who through a life of thrift and self-denial have saved provision for old age.”Footnote 122 The postwar Canadian survey found that those over 65 years of age were more likely than average to hold a mortgage (10.6% versus 6.5%).Footnote 123 Many would have been women, including widows. In Victoria and Hamilton around the turn of the century, widows were more likely than married women to hold mortgages; indeed, in Hamilton, along with estates, they provided most of the money handled by the Moore and Davis agency. Half a century later, women were providing more than two-fifths of first as well as junior loans.Footnote 124

Age and income were not the end of the story. Apparently well-informed observers implied other influences and patterns. Generalizing over centuries, real estate historian William Baer has suggested that “all economic classes and sexes joined in financing and investing in housing,” partly because many were “shut out from grander investments reserved for the ‘better sort.’” Certainly, Herbert Dyos, the father of urban history in Britain, claimed that in nineteenth-century London, mortgages came from the sorts of middle-class people who were buying homes.Footnote 125 Speaking about the 1920s, others agreed. In 1929, Alexander Bing suggested that the rich had lost interest in mortgages so that remaining lenders had lower incomes. A decade later W.W. Beal, a broker who founded the Iowa Securities Company, agreed. Challenging a stereotype of the “wealthy but heartless miser,” he suggested that the rich invested in the capital stock enterprises or bought real estate on credit. This left “ordinary folks—clerks who wanted a safe place for their earnings, farmers who had laid aside their small surplus year by year, teachers and laborers who looked forward to the time when they could no longer work, and many elderly men and women who … had accumulated some savings for old age.” This fits with what CMHC reported in Canada in 1955, that most private mortgages were provided by “persons of low or medium income.”Footnote 126 “Medium” is vague, but the emphasis in these commentaries is hardly consistent with those that speak of a bias toward the affluent.

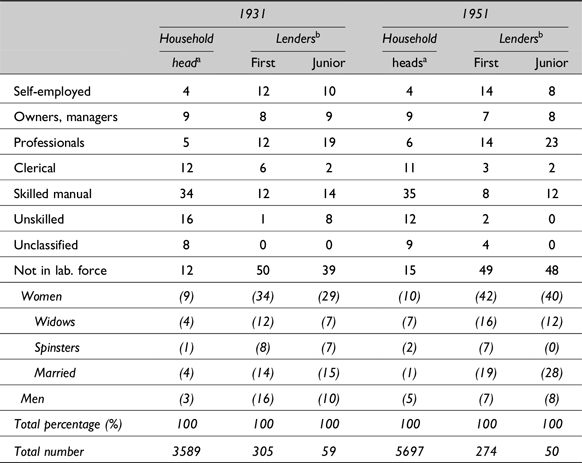

In most places and times, the reality was probably complex. In the advice he offered to fellow Miami brokers in 1925, Marcus Parker suggested that typical clients were diverse: “doctors, school teachers and trades people (bricklayers, carpenters, mechanics, etc).”Footnote 127 With qualifications, the same was apparent in Hamilton in 1931 (Table 3). Skilled workers provided as many first loans (12%) as the self-employed and professionals. True, compared with their numbers in the city (34%), they were underrepresented. However, at least there was some diversity, and for junior mortgages too (Table 3). What is most striking was the major role played by those not in the labor force—half of all first mortgage and two-fifths of juniors fit that category—above all, women. Over the next 20 years, the bias toward professionals, the self-employed, and women increased markedly (Table 3). Many of the clerical and manual workers who made loans would only have done so as holders of VTB mortgages. It was businessmen and professionals, notably lawyers, along with women, who accounted for the great majority of other loans. If there is any surprise here, it is the large number of loans held by women, whether “spinsters” (that thankfully obsolete term), married, or widows. Their role in the market has still not been fully acknowledged.

Table 3 Characteristics of Household Heads and Individual Leaders, Hamilton, 1931 and 1951

Sources: aLongitudinal sample (5%) from Hamilton land registry and property assessment records, 1931 and 1951. bSubsample (25%) of private lenders, Hamilton land registry and property assessment records, 1931 and 1951

Notes: Lab, labor

Concluding Discussion

While Canada and the US were becoming urban nations, individual lenders played a vital role in the building and buying of homes. They sold land contracts to prospective owners on easy terms and then offered construction loans of various sorts. On finished homes, they provided first, second, and sometimes even third mortgages. And when the time came for owners to move on, many eased sales with vendor take-backs.

At first, these loans helped all types of borrowers but, eventually, some more than others and in particular ways. At root, this was because they were free to take whatever risks they chose; they followed “no standard practice”; they could be flexible in ways that institutions could or would not.Footnote 128 They helped family members and friends. Whether or not guided by a broker, they could offer “humane” treatments to borrowers in arrears. Unconstrained by red tape, they could respond more quickly.Footnote 129 They were able, and often willing, to pick up the slack left by “statutory controls, government regulations, racial and other discrimination by [institutional] lenders against classes of borrowers …”Footnote 130

After all, there was much slack—gaps in terms of types of loans, properties, places, and/or persons. Many institutions were wary of making loans on vacant lots or for the construction process. A consistent gap was the junior mortgage, which institutions avoided even when allowed to offer. Others were the—potentially or actually—sketchier properties: those that were owner-built, were cheaper, or, in later decades, did not qualify for FHA insurance.Footnote 131 Owners of perfectly good homes in particular locations often had difficulty getting finance. In Canada, for decades, institutions did not “function” in some regions while, especially but not only in the US, some districts, as in New York, were effectively redlined even before federal agencies formalized the practice.Footnote 132 And, most controversially then and now, certain borrowers were targeted, notably African Americans. In such ways, individuals helped people who otherwise would not have been able to acquire property. They were also willing to offer loans at times when institutions drew back, becoming a counter-cyclical influence, whether locally, as in postwar San Francisco, or nationally.Footnote 133 In the process, as William Baer has put it, they provided “this ‘lumpy,’ high cost product with some liquidity which then redounded to all—builder, owner-occupant, investor, landlord and tenant—allowing the market better to function.”Footnote 134

However, it would be wrong to leave things there. Whether acting independently, or receiving poor guidance from brokers, some individuals had inadequate information and made poor decisions. They inadvertently encouraged borrowers to bite off more than they could chew, getting both borrower and lender into trouble. Others knew very well what they were doing, exploiting vulnerable and ignorant clients, notably with land contracts. Their saving grace was that, unlike institutions, the scale of their scams had narrower limits.

It was in the 1950s, when Canada and the US really became suburban nations that, with federal assistance, institutions took charge. They made the mortgage business more professional, and more centralized. With FHA guidance, they made predictable loans on regulated homes in standardized subdivisions. These suited new secondary markets that connected real estate with wider capital markets. In the process, they displaced lending practices that had helped millions to acquire, or build, homes. A century ago, all sorts of people were involved in making loans. Many relied on their broker’s advice, but the decision about what loans to make and to whom was ultimately theirs. Others were poorly informed, and all relied somewhat on instinct. As lenders became less diverse and numerous, they became better informed and more focused on the real estate trade, while brokers turned to institutional clients. Institutions themselves became the default for most potential borrowers, who walked into the local offices of Savings and Loans or banks. Loan officers and corporate staff became the key players. The outcome was not invariably better, as later Savings and Loan and bank crises showed. Nevertheless, by the late 1950s the die had been firmly cast.

We should not sanctify the individual lenders, but neither should we condemn or ignore them. As much as any lending institution, they helped millions realize the American—or Canadian—dream, creating many of the older homes and neighborhoods we know today. Any history of home building, mortgage finance, housing, or neighborhood change should fully acknowledge their role.

Author Biography

Richard Harris, Professor Emeritus of Urban Geography at McMaster University, is a Guggenheim Fellow and Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. He has published widely on the twentieth-century history of housing, neighborhoods, and suburban development in North America. His most recent work is The Rise of the Neighbourhood in Canada, 1880s–2020s (Toronto, 2025).