Whenever the situation is really, really bad, you call in the woman.

– Christine Lagarde, Former Managing Director of the International Monetary FundFootnote 1

Introduction

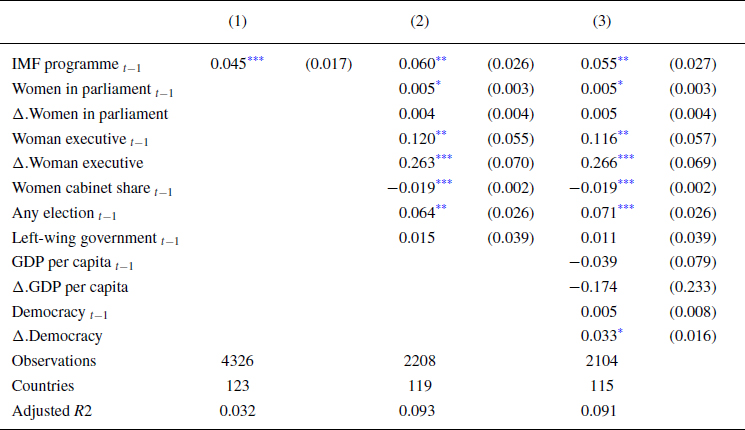

Our paper is motivated by a surprising puzzle: the number of women in ministerial jobs increases during International Monetary Fund (IMF) programmes. The recent case of Jordan is a case in point. Finding itself amid economic turmoil, the Jordanian government turned to the IMF in March 2020. Importantly, facing a steep uphill battle against soaring inflation alongside the outfalls from the pandemic and conflicts in its neighbourhood, the government continued its path of unpopular austerity and economic reforms. Confronted with substantial political opposition, Prime Minister Al‐Khasawneh increased the number of women in his government to three cabinet seats in October 2022. Cabinet compositions in Greece (2010) and Kenya (2018) under their respective IMF programmes imply that the Jordanian case is no exception. Indeed, Figure 1 reveals this striking pattern: In countries that begin a new IMF programme, the share of women in cabinet is significantly lower relative to men. At the same time, in countries under an ongoing IMF programme, the share of women in the cabinet is considerably higher than that of men. While these findings are merely suggestive and may be driven by omitted variables, they suggest a distinctive pattern in the gendered politics of IMF engagement.

Figure 1. IMF exposure and percentage of women cabinet ministers.

Note: The graph compares the average percentage of women ministers for country‐year observations without an IMF programme, the observations under the first year of an IMF programme and the observations under an ongoing IMF programme beyond its first year. All differences are statistically significant using t‐tests with unequal variance (p < 0.01).

The pattern we document is surprising for two reasons: First, IMF programmes have long been criticized for their adverse impact on gender equality. For example, Detraz and Peksen (Reference Detraz and Peksen2016) show that privatizations and spending cuts in IMF programmes harm women's economic and political rights by reducing the government's willingness and ability to protect fundamental human rights. Similarly, Kern et al. (Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Lee2024) show that the labour force participation gap between men and women widens under IMF programmes, and Mathers (Reference Mathers2020) argues that spending cuts and austerity measures under IMF programmes compound the unpaid care burden of women, forcing them to fill the gap left by the shrinking welfare state. Second, the IMF has only very recently started to try to foster more gender equality in recipient countries. The IMF published its first gender mainstreaming strategy in July 2022. The strategy identifies gender equality as one of the contributors to better economic growth prospects, resilience and economic stability. To this end, the strategy promises to review the Fund's core activities such as lending, surveillance and capacity development with a gender equality perspective, to collect and analyse gender‐disaggregated data and to strengthen the relationship with key external stakeholders and enforce peer learning in the field of gender equality.Footnote 2 Given the overall negative consequences of IMF programmes for gender equality and the lack of effort by the IMF to facilitate gender representation in recipient countries, the question remains: Why do women ministerial appointments increase under IMF programmes?

We argue that the ‘glass cliff’ effect drives the increase in women ministers in the cabinet under IMF programmes. The ‘glass cliff’ effect refers to the appointment of women to risky leadership positions, especially when organizations are undergoing a crisis (Haack, Reference Haack2017; Kulich et al., Reference Kulich, Ryan and Haslam2014; Ryan & Haslam, Reference Ryan and Haslam2007; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Haslam and Kulich2010; Weeks et al., Reference Weeks2023). Because women in those precarious leadership positions often face a higher risk of failure, they are an easy target for blame‐shifting attempts from established insiders (Bruckmüller & Branscombe, Reference Bruckmüller and Branscombe2010; Bruckmüller et al., Reference Bruckmüller, Ryan, Rink and Haslam2014; Haslam & Ryan, Reference Haslam and Ryan2008; Morgenroth et al., Reference Morgenroth, Kirby, Ryan and Sudkämper2020). As such, these gendered leadership appointments reflect not greater gender empowerment but a subtle mechanism to shift blame for failure, reflecting deep‐seated gender‐based discrimination and biases (Morgenroth et al., Reference Morgenroth, Kirby, Ryan and Sudkämper2020; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Haslam and Kulich2010, Reference Ryan, Haslam, Morgenroth, Rink, Stoker and Peters2016). While ample evidence supports the presence of a ‘glass cliff’ effect in various bureaucratic (Groeneveld et al., Reference Groeneveld, Bakker and Schmidt2020; Smith, Reference Smith2023), business (Ryan & Haslam, Reference Ryan and Haslam2005), legal (Ashby et al., Reference Ashby, Ryan and Haslam2006) and electoral competition contexts (Kulich et al., Reference Kulich, Ryan and Haslam2014; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Haslam and Kulich2010), little is known about gendered appointments to political leadership positions during times of domestic political and economic turmoil under international influence (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Barnes, Chiba and O'Brien2023; Smith, Reference Smith2022). Advancing this stream of research in international political economy, we study this mechanism in the context of IMF programmes. IMF programmes are politically costly for established insiders due to the sovereignty costs of accepting an external actor to determine policies (Kern et al., Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2023; Przeworski & Vreeland, Reference Przeworski and Vreeland2000). Moreover, the need for IMF intervention may reveal the inability of established insiders to manage the economy (Dreher & Gassebner, Reference Dreher and Gassebner2012). These political costs entice government insiders to enlist outsider groups to shift the blame onto them.

We test these arguments using data on all IMF programmes in 141 developing countries from 1980 to 2018. Our empirical analyses show that IMF programme participation predicts a significant increase in the percentage of cabinet positions held by women relative to men. In substantive terms, programme participation increases the likelihood of an increase in women's cabinet appointments by 5.5 per cent. We also find that this result is driven by ongoing programmes rather than programme onsets, suggesting that women advance to positions of influence once the unpopular adjustment measures under IMF programmes are scheduled for implementation. Further analysis shows that the likelihood of women's cabinet representation increases under IMF programmes especially for austerity‐bearing cabinet portfolios. Probing the scope conditions of this result further, we find stronger results in countries undergoing a more severe economic crisis, suffering from pervasive corruption and having greater gender inequality compared to cases of less severe crisis, less corruption and greater gender equality.

Our paper makes important contributions to debates on women's representation in countries worldwide. First, we add to the fast‐growing stream of literature that analyses the role of women's descriptive representation in international political economy (Elias & Rai, Reference Elias and Rai2019; Hutchinson et al., Reference Hutchinson, McGuire, Rosenbluth and Yamagishi2018; Iversen & Rosenbluth, Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2010; Iversen et al., Reference Iversen, Rosenbluth and Skorge2020). Our work is closely related to recent scholarship emphasizing the importance of women's leadership within the subfield of studying international financial markets (Prügl, Reference Prügl2012), monetary institutions (Bodea & Kerner, Reference Bodea and Kerner2022; Bodea et al., Reference Bodea, Ferrara, Kerner and Sattler2021; Capie & Wood, Reference Capie, Wood and Mayes2019) and structural adjustments (Detraz & Peksen, Reference Detraz and Peksen2016; Elson, Reference Elson and Elson1991; Reinsberg et al., Reference Reinsberg, Kern, Heinzel and Metinsoy2024). Whereas hitherto approaches study the impact of women's leadership on specific socio‐economic and political outcomes, we analyse when women are selected for these leadership positions. Insofar, our work is related to Armstrong et al. (Reference Armstrong, Barnes, Chiba and O'Brien2023), who studied the selection of women ministers of finance during financial crises. A key innovation of our approach is to examine gendered cabinet appointment as a new dimension of domestic politics as a response to global policy pressures. In doing so, our approach expands on the role of international organizations in promoting gender equality. Whereas existing research on gender mainstreaming in international organizations concentrates on the impact of prescribed policy measures to further gender empowerment across member countries, we show that IMF programmes may have ‘glass cliff’ effects – selecting women for precarious leadership positions during crises. In our case, incumbents appoint women not to advance gender empowerment but to shift blame and accountability for unpopular economic policy measures to women. Importantly, our results indicate that this effect is more pronounced in societies with less progressive gender norms, a more corrupt government and when the crisis is deeper, underscoring the presence of a glass cliff effect.

Second, our findings complement existing research on the descriptive representation of women in politics (Barnes & Burchard, Reference Barnes and Burchard2013; Reingold & Harrell, Reference Reingold and Harrell2010; Sanbonmatsu, Reference Sanbonmatsu2003) with particular reference to ministerial cabinets (Annesley et al., Reference Annesley, Beckwith, Franceschet, Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Barnes & O'Brien, Reference Barnes and O'Brien2018; Escobar‐Lemmon & Taylor‐Robinson, Reference Escobar‐Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson2005; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Scherpereel and Adams2014; Krook & O'Brien, Reference Krook and O'Brien2012). A key innovation of our approach is concentrating on gendered cabinet appointments during economic turmoil and potential governmental instability (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Barnes, Chiba and O'Brien2023; Dreher & Gassebner, Reference Dreher and Gassebner2012; Smith, Reference Smith2022). We expand on this literature in several ways. By studying IMF programmes, we capture a broader set of countries over a more extended period. A key advantage of studying the role of IMF programmes on gendered cabinet formation is that austerity measures impact different government portfolios to varying degrees. In line with existing research, our findings indicate that women are appointed to ministries that closely map onto preconceived gender stereotypes (Annesley et al., Reference Annesley, Beckwith, Franceschet, Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Escobar‐Lemmon & Taylor‐Robinson, Reference Escobar‐Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson2005; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Scherpereel and Adams2014; Smith, Reference Smith2022; Studlar & Moncrief, Reference Studlar and Moncrief1999). Interestingly, women are less likely to be assigned to lead finance ministries or national audit and oversight offices but more likely to take over labour, social affairs and health ministries. Most decision‐making on austerity and economic reform measures happens in the finance ministries and at the prime minister level as a core group that negotiates the programmes with the IMF at the start. More women are only assigned to cabinet positions during programme implementation when they must execute unpopular programmes such as public wage cuts and labour market reforms while having little to no say in the actual decision‐making. Our reading of this evidence is that women are selected for political leadership positions with comparably little political leverage, so they cannot disrupt existing men's insider networks but are asked to assume full accountability for implementing unpopular policy measures.

Third, we complement the existing research on gendered cabinet appointments (Annesley et al., Reference Annesley, Beckwith, Franceschet, Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Bauer & Okpotor, Reference Bauer and Okpotor2013; Escobar‐Lemmon & Taylor‐Robinson, Reference Escobar‐Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson2005). For instance, Annesley et al. (Reference Annesley, Beckwith, Franceschet, Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019) propose a ‘gendered institutionalist’ approach to cabinet appointments and argue that there are formal and informal rules that make members of the political class, including women, seen as more or less selectable as ministers by those who select them. We complement their study by discussing the international dimension of such appointments. In addition, we contribute to research on blame avoidance and political blame games, discussing the blame shifting between heads of governments and ministers (Hinterleitner & Sager, Reference Hinterleitner and Sager2017). We show how, under IMF programmes, ‘insiders’ can pick relative outsiders to shift blame onto them during the implementation stage of socially and politically costly IMF measures. Finally, scholars have long studied how IMF programmes can influence domestic political outcomes (Casper, Reference Casper2017; Hartzell et al., Reference Hartzell, Hoddie and Bauer2010; Kern et al., Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Rau‐Göhring2019; Milner, Reference Milner2005; Reinsberg et al., Reference Reinsberg, Stubbs, Kentikelenis and King2019; Vreeland, Reference Vreeland2003). We complement those studies by examining gendered cabinet appointments and blame‐shifting under IMF programmes.

Our findings have important policy implications. For one, we show that IMF programmes can work as a catalyst to increase women's descriptive representation. Although an increasing number of women in government represents a key pillar of gender empowerment,Footnote 3 the riskiness of assignments could undermine gender empowerment in the long term (Morgenroth et al., Reference Morgenroth, Kirby, Ryan and Sudkämper2020). A ‘glass cliff’ has the potential to damage women's political careers while reinforcing negative gender stereotypes in borrowing countries. Having to absorb the political heat from implementing unpopular austerity and reform measures with little say in the policy design can leave women leaders vulnerable, leading to a popular backlash against women and gender empowerment. Besides the increased risk of failure and its reputational consequences, withstanding enormous political pressure and fierce opposition during turmoil can be extremely taxing on a personal psychological level (Ryan & Haslam, Reference Ryan and Haslam2007). Even in progressive societies, where women's leadership is widely accepted and taken for granted, women face greater personal and professional scrutiny in leadership positions (Bisbee et al., Reference Bisbee, Fraccaroli and Kern2022) and are likely exposed to greater psychical, psychological, sexual, economic and semiotic violence than men (Daniele et al., Reference Daniele, Dipoppa and Pulejo2023; Håkansson, Reference Håkansson2021; Krook & Restrepo Sanín, Reference Krook and Restrepo Sanín2020). From a policy perspective, our study emphasizes the need to evaluate the performance of women ministers acknowledging the glass cliff effect while considering contextual variables, such as economic crises, corruption and gender biases, to achieve fairer assessments and greater gender equality.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section discusses the glass cliff effect in more detail. The third section explains the research design. The fourth section describes the findings. The final section summarizes the findings and offers several policy recommendations based on this study.

Women's leadership in government: The ‘glass cliff’ effect

The descriptive representation of women in political leadership positions represents a key pillar of gender empowerment and can lead – under certain conditions – to tangible social benefits for women (Alexander, Reference Alexander2012; Betz et al., Reference Betz, Fortunato and O'Brien2021; Keiser et al., Reference Keiser, Wilkins Vicky, Meier and Holland2002; Kirsch, Reference Kirsch2018; Mateos De Cabo et al., Reference Mateos De Cabo, Siri, Lorenzo and Ricardo2019; Profeta, Reference Profeta2020; Wilkins, Reference Wilkins2004). However, overcoming gender discrimination in political leadership is challenging. To reach the higher echelons of policymaking, women often have to overcome greater hurdles and are confronted with a more hostile environment once they successfully shatter the so‐called ‘glass ceiling’ and assume public office (Bisbee et al., Reference Bisbee, Fraccaroli and Kern2022; Groeneveld et al., Reference Groeneveld, Bakker and Schmidt2020; Håkansson, Reference Håkansson2021; Krook & Restrepo Sanín, Reference Krook and Restrepo Sanín2020; Morgenroth et al., Reference Morgenroth, Kirby, Ryan and Sudkämper2020). Despite these challenges, women's participation in economic and political life has increased in recent history (Annesley et al., Reference Annesley, Beckwith, Franceschet, Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Hughes & Tripp, Reference Hughes and Tripp2015). The proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments globally increased from 23.6 per cent in 2017 to 26.5 per cent in 2022. Similarly, the proportion of women in ministerial positions increased from 17.7 per cent in 2015 to 22 per cent in 2020 (World Bank, 2022).

Notwithstanding these advances in women's descriptive representation, there is abundant anecdotal evidence suggesting that women are often put in the driver's seat amid political and organizational turmoil (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Barnes, Chiba and O'Brien2023; Kulich et al., Reference Kulich, Ryan and Haslam2014; Ryan & Haslam, Reference Ryan and Haslam2005; Weeks et al., Reference Weeks2023). The recent appointment of Dr. Hafize Gaye Erkan as the first woman governor of the Central Bank of Türkiye in June 2023 is a case in point. With the Turkish Lira in free fall and the country on the verge of a full‐fledged balance of payments crisis,Footnote 4 Governor Erkan has been given the Herculean task of putting a stop‐gap on the government's decade‐long financial meddling while having to face substantial political resistance pushing for monetary tightening.Footnote 5 Regarding gendered cabinet appointments, Armstrong et al. (Reference Armstrong, Barnes, Chiba and O'Brien2023) find that women are more likely to be appointed finance ministers once a country faces financial turmoil. These examples illustrate a pattern long described by feminist scholars: the ‘glass cliff’ effect (Bruckmüller & Branscombe, Reference Bruckmüller and Branscombe2010; Bruckmüller et al., Reference Bruckmüller, Ryan, Rink and Haslam2014; Kulich et al., Reference Ryan and Haslam2007, Reference Kulich, Ryan and Haslam2014; Ryan & Haslam, Reference Ryan and Haslam2005; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Haslam and Kulich2010, Reference Ryan, Haslam, Hersby and Bongiorno2011).Footnote 6

We argue that a similar mechanism can be observed during IMF programmes. The IMF frequently demands that governments implement economic reforms and austerity measures in exchange for bailout funding. Historically, these measures were, more often than not, subject to significant political resistance. In some instances, fierce political resistance exerted substantial political pressure on incumbents and led to social unrest (Abouharb & Cingranelli, Reference Abouharb and Cingranelli2009; Metinsoy, Reference Metinsoy2022; Reinsberg et al., Reference Reinsberg, Stubbs and Bujnoch2023; Walton & Ragin, Reference Walton and Ragin1990). Furthermore, IMF programmes entail high sovereignty costs (Przeworski & Vreeland, Reference Przeworski and Vreeland2000) and can signal a government's incompetence in addressing the crisis (Dreher & Gassebner, Reference Dreher and Gassebner2012). In other words, IMF programme implementation may threaten a borrowing government's political survival (Kern et al., Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2023). We claim that the ‘glass cliff’ effect – the appointment of women into leadership positions amidst crises during which they face a higher risk of failure – increases women's representation in ministerial positions during IMF programmes. Several interrelated theoretical mechanisms reinforce these patterns of gendered appointments under IMF programmes.

First, women often enjoy greater political legitimacy as outsiders during political and economic turmoil (Hughes & Tripp, Reference Hughes and Tripp2015, p. 1518). They are often seen as political outsiders and, hence, are not held responsible for the misdeeds of the earlier administrations that brought the country into the crisis and consequently to borrowing from the IMF. Furthermore, ample evidence indicates that women's transformational leadership style, characterized by creativity, problem‐solving skills, interpersonal care, attentiveness and personal integrity makes women credible crisis managers (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Barnes, Chiba and O'Brien2023; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Haslam, Hersby and Bongiorno2011). Thus, appointing women to leadership positions in established ‘old‐boys’ networks can signal change to international and domestic audiences that they deviate from ‘business as usual’. For this reason, we argue that the ‘glass cliff’ effect is driven by governments’ desire to signal radical change to boost their policy credibility under an IMF programme (Calvo‐Gonzalez, Reference Calvo‐Gonzalez2007; Kulich et al., Reference Kulich, Lorenzi‐Cioldi, Iacoviello, Faniko and Ryan2015). In other words, under international austerity measures, women candidates might fit better into the selectors’ profile of potential cabinet members.Footnote 7 To illustrate this point, consider the case of South Korea during its IMF programme in 2002. Amidst political scandals involving the imprisonment of his two sons on corruption charges and facing political backlash due to implementing scaring structural reforms during the IMF programme, President Kim Dae‐Jung nominated Chang Sang to become the country's first woman prime minister with the hope that the ‘appointment of a highly respected woman would win votes in an election year marred by […] corruption scandals’.Footnote 8

Second, being less corruptible in public office and lacking the required networks and resources to uproot or challenge the existing political status quo, women represent viable scapegoats and allow ‘old boys’ clubs to deflect blame for unpopular government policies (Håkansson, Reference Håkansson2021; Hinterleitner & Sager, Reference Hinterleitner and Sager2017; Marx, Reference Marx2002; Morgenroth et al., Reference Morgenroth, Kirby, Ryan and Sudkämper2020). In this respect, women ministers might ‘unintentionally’ shield political insiders from political backlash during economic hardship. For instance, Marx (Reference Marx2002, p. 124) remarks that ‘…in Africa, women have often been used as scapegoats by political leaders, who attack women traders and those in modern dress to divert attention and conflict over more general economic failure’. At the same time, being outsiders to established political networks, women are disadvantaged in defending themselves in these precarious/vulnerable leadership positions.Footnote 9 To illustrate this point, consider the case of Tunisia, where women have systemically been discriminated against and were rarely allowed to actively participate in political life (Benstead, Reference Benstead, Franceschet, Lena Krook and Tan2019). To protect political insiders and to ensure that appointed ministers would not have sufficient political leverage to fend off blame‐shifting, President Ben Ali appointed two women ministers in a cabinet reshuffling in 2001 (Wikileaks Cable, n.d.). Against this background, we argue that appointing women to ministerial positions becomes a politically appealing option during IMF programmes when blame deflection is important to shield key constituents from the adverse political consequences of increasing economic pressures. Synthesizing these arguments yields the expectation that more women will be appointed to ministerial positions during ongoing IMF programmes.

-

Hypothesis 1. (Glass‐cliff hypothesis): Women's appointment to a country's cabinet increases if the country is under an IMF programme.

An implicit assumption underlying our theoretical insights is that women are willing to accept precarious leadership positions and potentially risk their future career paths. There are several reasons as to why this is the case. First, gender discrimination reduces the number of positions available for qualified women candidates. Hence, when opportunities arise, women will find them harder to turn down (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Haslam and Postmes2007). Second, Glass and Cook (Reference Glass and Cook2016) discovered that individuals belonging to marginalized groups, such as women and people of colour, in prestigious positions actively seek risky leadership roles to navigate the dual challenges of being overlooked and excessively scrutinized as outsiders. Third, the case of Valeria Gontareva, the former Governor of Ukraine's National Bank, illustrates that selected candidates are sometimes unaware of the ‘impossibility’ of their leadership mission (Gontareva & Stepaniuk, Reference Gontareva and Stepaniuk2020). Speaking about her appointment, she openly admitted to a Washington Post reporter that ‘[…] of course I knew there were problems, but I could not imagine what problems I would face. I was quite naïve’,Footnote 10 illustrating that selected candidates often do not fully understand that they are walking onto a ‘glass cliff’. Finally, heads of government often run out of options to appoint viable candidates for a ministerial position. Knowing about little chances to succeed during times of turmoil, members of the established political elite networks (who are often men) turn down cabinet positions to shield their career prospects, increasing the chances of women and other members of marginalized groups to be nominated (Alexiadou et al., Reference Alexiadou, Spaniel and Gunaydin2022; Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Barnes, O'Brien and Taylor‐Robinson2022).

Our theory has some additional observable implications. Building on previous work on IMF interventions and gendered cabinet reshufflings, we expect the appointment of women to ministerial leadership positions to be more likely in certain institutional settings and under certain economic conditions. We discuss three such conditions below.

First, we expect more women to be appointed to ministerial positions when societal gender equality norms are weak. In societies with less progressive gender norms, women are less represented in political leadership and thus can be regarded as outsiders to established political elite networks (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Barnes, Chiba and O'Brien2023; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Haslam and Kulich2010). Women's outsider position implies they are not as networked as their male colleagues, making it harder for them to oppose unpopular policy programmes and austerity measures. Furthermore, it diminishes their ability to fend off blame for implementing unpopular policy programmes and spending cuts. Brought to power as outsiders to the system, citizens might more readily believe that women ministers deserve blame and will ultimately fail as their ascribed competencies are not congruent with the exigencies of their role (Eagly & Karau, Reference Eagly and Karau2002).Footnote 11 At the same time, not being part of established political networks, women are less likely to be corrupt and thus provide a powerful signal to key stakeholders about the viability of intended reforms (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Barnes, O'Brien and Taylor‐Robinson2022).

Second, we expect the effect to be stronger in countries with pervasive corruption. Where old elite networks are deeply embedded in corrupt practices, appointing an outsider can divert attention from pervasive corruption and gain renewed legitimacy for the administration (for a review, see Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Barnes, O'Brien and Taylor‐Robinson2022). Moreover, old elite networks involved in corruption can rationally anticipate more onerous IMF conditionality due to their misdealing (Kern & Reinsberg, Reference Kern and Reinsberg2022). Insofar, appointing women as outsiders to ministerial cabinet positions can signal that the government is invested in cleaning up its house (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Barnes, O'Brien and Taylor‐Robinson2022).

Third, we expect the glass‐cliff mechanism to be more pronounced when the economic crisis necessitating the IMF programme is deeper. This expectation directly results from the anticipated higher adjustment burdens that generate more demand for both the signalling and scapegoating functions of women's appointments to political leadership positions. Taken together, we formulate our second hypothesis.

-

Hypothesis 2. (Glass cliff contexts): The ‘glass cliff’ effect is particularly pronounced under poor social gender norms, when the political system is corrupt, and when the economic crisis is severe.

Finally, we can exploit variations in the relevance of government ministries to implementing austerity. Austerity measures impact different government portfolios to varying degrees. In particular, we expect women ministers to be appointed to ministries with high responsibility but low leverage in implementing austerity measures, such as ministries for employment, labour and social policy. Importantly, these ‘austerity‐bearing ministries’ are not involved in the negotiation of the austerity measures that they must subsequently implement. We expect that women are offered to lead austerity‐bearing ministries so they cannot disrupt existing insider male networks but must assume full accountability for implementing unpopular policy measures during an economic crisis.Footnote 12 An example is Wafaa Bani Mustafa, appointed Minister of Social Development in the cabinet reshuffle of October 2022 in Jordan. With growing economic hardship and civil unrest,Footnote 13 Ms. Bani Mustafa was tasked to implement austerity packages under Jordan's IMF programme as a minister of social development and bear the political and social costs. These observations motivate our third hypothesis.

-

Hypothesis 3. (Glass cliff ministries): The ‘glass cliff’ effect is more strongly observed for austerity‐bearing ministries than those without political responsibility for implementing austerity measures.

An additional implication we address empirically pertains to the timing of the glass cliff effect. We argue that it is optimal for political elites to appoint women when IMF programmes are already ongoing rather than at the outset of these programmes. Appointing outsiders at the start would logically offer a stronger signal to international financial markets and domestic and international audiences regarding the government's intentions to break with old patterns (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Barnes, O'Brien and Taylor‐Robinson2022, Reference Armstrong, Barnes, Chiba and O'Brien2023). However, this overlooks the countervailing incentives for the old elite network that give rises to the ‘glass cliff’ effect and the bargaining protocol for impending IMF programmes. The old elite networks might use these negotiations to distribute the burden of austerity selectively and shield their constituencies from the negative impact of cuts (Reinsberg & Abouharb, Reference Reinsberg and Abouharb2023). Hence, these networks would be reluctant to admit outsider groups in the crucial moment of negotiations but enlist them to share the burden of austerity once programmes start and their hardships become more widely felt.Footnote 14 As IMF programme negotiations usually involve the prime minister, the finance ministry and the central bank, the old elite networks will block the entry of outsiders into these positions.Footnote 15

Data and methods

We test our theoretical expectations at two different levels of analysis. First, we employ cross‐country time‐series regressions to examine the relationship between IMF programme participation and the likelihood of an increase in the share of women in cabinet positions. Second, we conduct analyses at the country‐minister year level, which allows us to exploit the differential exposure of different cabinet portfolios to the political costs of austerity.

For the first analysis, our starting point is a panel data set of 141 developing countries from 1980 to 2018. To ensure that our comparisons are plausible, we restrict the analysis to countries that are not high‐income countries.Footnote 16 Our outcome of interest is the women's cabinet percentage, which denotes the percentage of cabinet positions held by women (Nyrup & Bramwell, Reference Nyrup and Bramwell2020). We dichotomize this variable to capture instances of net transitions – where more women than men are appointed for cabinet positions.Footnote 17 In robustness tests, we use the continuous change in women's cabinet appointments. Our key predictor is binary and captures whether a country participated in an IMF programme the previous year. The data come from the IMF Monitor Database (Kentikelenis et al., Reference Kentikelenis, Stubbs and King2016). In further analyses, we leverage information on the start dates of these programmes to distinguish between instances of IMF programme onset and ongoing IMF programmes. The former refers to years in which governments start a new programme, while the latter refers to years in which governments are under continued exposure to a programme that was initiated in an earlier year. Both sets of observations are not mutually exclusive, given that programmes may begin anytime during a given year. Importantly, our measures of IMF programme participation can be conceived as a proxy for hardships induced on broad segments of the population (Reinsberg & Abouharb, Reference Reinsberg and Abouharb2023).

For control variables, we draw on the respective debates on women cabinet appointments and IMF programmes, focusing on the most likely confounders. First, we control for the percentage of women in parliament (World Bank, 2022) and whether the country has a woman leader (Nyrup & Bramwell, Reference Nyrup and Bramwell2020). These variables capture the degree of political empowerment of women in general (Krook & O'Brien, Reference Krook and O'Brien2012). These variables may drive women's cabinet representation as well as IMF programme participation, and we include both their levels and their first differences. Similarly, we control for the lagged percentage of women ministers in government, arguing that new women's appointments become less likely as women are already well represented. We also hold governments’ political ideology constant since left‐wing governments may be more likely to put women forward for cabinet positions. Considering political opportunity structures, we control for elections. Elections provide a routine mechanism for changing political personnel. At the same time, we know that IMF programmes are more likely to occur after an election because (strategic) governments will hold out until after an election to announce an IMF programme that may not be popular with voters due to its short‐term adverse welfare implications (Dreher, Reference Dreher2003). Finally, we include macro‐structural variables, specifically the (logged) GDP per capita and an index of democracy. An increase in per‐capita income may advance post‐material values (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart2015), while more civil liberties and political rights may be conducive to appointing women to political offices (Barnes & Burchard, Reference Barnes and Burchard2013). We include both the level and the change of these variables. Variable definitions and descriptive statistics for all the variables are shown in the online appendix (Table A1).

We estimate our models using linear probability models with two‐way fixed effects. Country‐fixed effects control for unobserved time‐invariant confounders and imply that our estimates identify within‐country relationships. Year‐fixed effects can account for general trends, such as the overall empowerment of women in politics. Given the need for fixed effects, we opt for a linear model which retains all observations. We cluster standard errors on countries.

For the second analysis, we expand the sample to the country–minister–year level. The dependent variable in this analysis is binary, capturing whether a woman holds a cabinet position in a given year. The data are directly taken from the WhoGov database (Nyrup & Bramwell, Reference Nyrup and Bramwell2020). We employ two predictors. The first is the country‐level predictor of whether a country is under an IMF programme, available from the IMF Monitor (Kentikelenis et al., Reference Kentikelenis, Stubbs and King2016). The other varies across cabinet portfolios. Specifically, we measure whether a cabinet portfolio is austerity bearing in that much of the burden of adjustment would fall under its remit. For instance, the Ministry of Labour, Employment, and Social Services would be an austerity‐bearing portfolio because many IMF programmes include measures adversely affecting labour groups by removing individual labour protections, curbing collective labour rights and cutting unemployment benefits (Caraway, Reference Caraway2006; Caraway et al., Reference Caraway, Rickard and Anner2012; Gunaydin, Reference Gunaydin2018; Metinsoy, Reference Metinsoy2022; Reinsberg et al., Reference Reinsberg, Stubbs, Kentikelenis and King2019; Abouharb & Reinsberg, Reference Abouharb and Reinsberg2023). We present the complete list of austerity‐bearing ministries in the online appendix.Footnote 18 This variable cuts across existing classifications that seek to divide ministries based on prestige or masculinity (Krook & O'Brien, Reference Krook and O'Brien2012).

Given that we expect the glass cliff effect to be most relevant for austerity‐bearing ministries, we can run difference‐in‐differences models in which we can estimate the relationship between IMF programme participation and women minister appointments, exploiting the differential sensitivity to the effects of austerity across ministries. In this setting, the IMF programme becomes a macro‐level treatment at the level of government. Austerity‐bearing ministries are the treatment group, while other ministries serve as a natural control group. To facilitate interpretation, we would want our control group to be completely unaffected by IMF programmes, which is difficult to argue for most ministries. Hence, our preferred baseline control is the Ministry of Finance, for which anecdotal evidence suggests that leadership change is improbable during an IMF programme (Djiwandono, Reference Djiwandono2000). A key inferential assumption requires that outcomes in the treated group would have evolved like in the control group. While this assumption is ultimately untestable, we present some evidence of pre‐treatment trends by including dummies for the 4 years before the IMF programme in our regressions.Footnote 19

Results

The ‘glass cliff’ effect in the context of IMF programmes

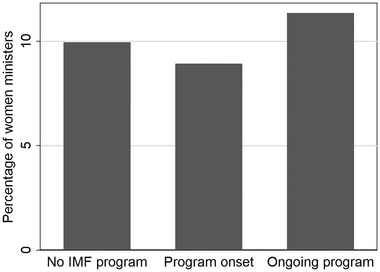

We conduct country‐year panel analysis using two‐way fixed effects. This analysis allows us to explicitly study the relationship between IMF programmes and women cabinet percentages while taking confounding factors into account. Table 1 shows the relationship between IMF programmes and the women's cabinet percentage. Across model specifications, we find a significantly positive relationship between IMF programme participation and increases in the women's cabinet share. In substantive terms, undergoing IMF programmes is associated with a 5.5 per cent increase (95% CI: 0.2−10.8 per cent) in the likelihood of women's cabinet minister appointments.

Table 1. IMF programmes and women's cabinet appointments

Note: Two‐way fixed effects estimations with country‐clustered standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable indicates an increase in women's cabinet percentage compared to the previous year.

Significance levels: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

We now disaggregate programme‐related observations, which allows us to probe an observable implication of the glass cliff mechanism. Suppose women are appointed to the cabinet to handle the fallout of ongoing IMF programmes. In that case, we should observe a stronger relationship between ongoing IMF programmes and more women cabinet minister appointments than IMF programme onsets. Table 2 confirms this expectation. We find no relationship between programme onsets and women's cabinet appointments but a statistically significant and positive association between ongoing IMF programmes and women's cabinet appointments. In substantive terms, if interpreted causally, continuing an IMF programme increases the likelihood of more women cabinet minister appointments by 7.8 per cent (95% CI: 1.7−13.8 per cent).

Table 2. IMF programmes and women cabinet percentages

Note: Two‐way fixed effect estimations with country‐clustered standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable indicates an increase in the women's cabinet percentage compared to the previous year. The models use different IMF variables. As indicated in the column header, the first three models use programme onsets, while the latter three models use ongoing programmes.

Significance levels: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

In the online appendix, we probe the robustness of these results. These robustness tests do not change our main conclusions, and we briefly report on them here. First, we (explicitly) control for instances where governments replace women ministers with men ministers. Accounting for these reversals in women's cabinet representation does not change our results (Table A4). Second, we test whether our results hold at the extensive margin. To that end, we replace the dummy with the logged change in the percentage of women cabinet members, restricted to cases of net increases. We obtain very similar results to our primary analyses (Table A5). Finally, we use the (unrestricted) logged change in the percentage of women ministers, whereby positive values indicate more women appointments and negative values indicate dismissals of women ministers. This outcome variable is not our preferred one because it would also (wrongly) support our argument when women ministers are dismissed outside an IMF programme. Despite this drawback, we use this variable for a robustness check, finding support for our ‘glass cliff’ hypothesis (Table A6).

‘Glass cliff’ ministries

In this section, we test our prediction that the ‘glass cliff’ effect during IMF programmes should concentrate on ministries responsible for implementing austerity measures. Inspired by pathbreaking work that classified cabinet portfolios according to their prestige as well as their gendered reputation (Krook & O'Brien, Reference Krook and O'Brien2012), we derive a list of cabinet positions that would be expected to confront the most public dissent about austerity measures. From the vast literature on the sociopolitical effects of IMF programmes (Haggard, Reference Haggard1985; Rickard & Caraway, Reference Rickard and Caraway2019; Walton & Ragin, Reference Walton and Ragin1990), we know that governments try to meet their debt‐service obligations by cutting public service provision and downsizing public employment, which will disproportionally affect women, children, families, public servants and students (Detraz & Peksen, Reference Detraz and Peksen2016; Elson, Reference Elson and Elson1991; Mathers, Reference Mathers2020). Hence, we expect the following ministries to be particularly exposed to anti‐austerity backlash: children and family; civil service; culture and heritage; education, training and skills; health and social welfare; housing; labour, employment and social security; science, technology and research; sports; women; and youth.

We create a data set at the country–minister–year level to test whether women ministers are appointed primarily in austerity‐bearing ministries. We then probe how IMF programme participation affects the likelihood of a women's ministerial appointment between austerity bearing and other ministries. Our baseline comparison is with the Ministry of Finance, which we assume does not change throughout the IMF programme because of its vital interlocutor role. Auxiliary analyses show, indeed, that IMF programme participation does not affect the likelihood of appointing a women finance minister, while, at the same time, the finance ministry is disproportionally often held by men (Table A7).

Before we present our estimation results, we explore the data descriptively. Figure 2 shows the average share of women in different cabinet portfolios. Grey circles show the women's share in a given ministry relative to the finance ministry when the country is not under an IMF programme. Black triangles indicate the women's share in the respective ministry relative to the finance ministry when the country is under an IMF programme. For example, among the observations in the sample that are not under an IMF programme, the share of women ministers of civil service is 2.8 percentage points higher than the women minister share in the finance ministry. However, when countries undergo IMF programmes, the share of women‐led civil service ministries is 11.3 percentage points higher than that of women‐led finance ministries. The difference is statistically significant because the confidence interval for the latter difference does not enclose the point estimate of the former difference. The figure overall confirms that women often hold portfolios with a more feminine reputation, while more prestigious cabinet positions are dominated by men (Krook & O'Brien, Reference Krook and O'Brien2012). The picture is less clear for the austerity‐bearing ministries. Those ministries tend to be more often held by women outside of IMF programmes. Austerity‐bearing ministries are more likely to be led by a woman during IMF programmes. This finding holds particularly for the ministries of civil service, education, training and skills, planning and development, tourism, women and, to some extent, children and family, culture and heritage, and science, research and technology. The visual patterns are broadly consistent with the glass cliff effect.Footnote 20

Figure 2. Share of women‐led ministries relative to the finance ministry under different contexts.

Note: Grey circles show women's share in the respective ministry relative to the finance ministry when the country is not under an IMF programme. Black triangles indicate women's share in the respective ministry relative to the finance ministry when the country is under an IMF programme.

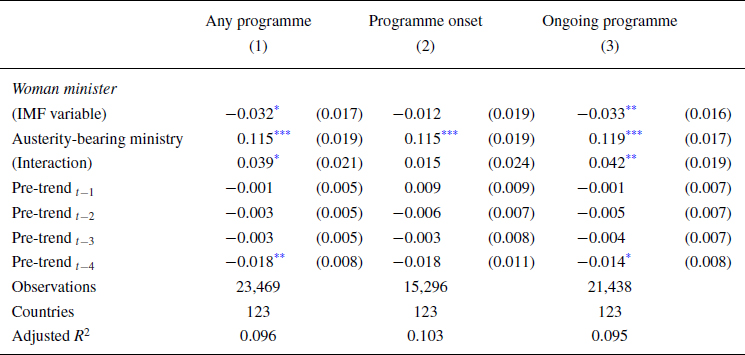

We now test our hypothesis on ‘glass cliff’ ministries using two‐way fixed effects regressions. The primary identifying assumption is common trends – austerity‐bearing ministries would have had the same likelihood to appoint women in the absence of an IMF programme. To understand pre‐treatment differences in women's appointments between ministries, our regressions include year dummies for up to four pre‐treatment years before the IMF programme. Table 3 shows that under IMF programmes, the likelihood of a woman appointee to an austerity‐bearing ministry is four percentage points higher compared to a man appointee. There is no significant gender difference when considering the onset of the programme. Finally, there is a significantly higher likelihood of a woman appointee to an austerity‐bearing ministry than a man appointee when the country is already under an IMF programme. Substantively, the additional effect is about 4.2 per cent (95% CI: 0.4−8.0 per cent), or about one additional woman being appointed. Most pre‐treatment dummies are not statistically significant, consistent with the common‐trends assumption. Only two of the 16 dummies are statistically significant 4 years before an IMF programme and are negative rather than positive. These findings further support our hypothesis about the ministries affected by the ‘glass cliff’ effect, indicating that women are more likely to be appointed to cabinet positions affected by the political costs of austerity.

Table 3. IMF programmes, austerity‐bearing ministries and women cabinet ministers

Note: Two‐way fixed effects estimations with country‐clustered standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable indicates a woman minister. Austerity‐bearing ministries include children and family, civil service, culture and heritage, education, training and skills, health and social welfare, housing, labour, employment and social security, science, technology and research, sports, women and youth.

Significance levels: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

‘Glass cliff’ contexts

In which contexts would we most likely observe the glass cliff effect? First, we expected the glass cliff effect to be stronger under adverse social gender norms because incumbent elites would find scapegoating women easier given these pre‐conceived norms and the more limited resources for women to withstand these scapegoating attacks in such contexts. Hence, we split the sample at the median of the VDem gender equality index and estimate the relationship between IMF programmes and women's cabinet representation conditional upon adverse societal gender norms. Second, where political elites are more corrupt, they have greater incentives to appoint women ministers to divert attention from corruption and gain renewed legitimacy for the administration. We rely on VDem's public‐sector corruption index to identify corrupt settings. Third, a more severe crisis increases the political benefits of appointing an outsider to an austerity‐bearing ministry who can be scapegoated for unpleasant adjustment measures. To construct a latent index of crisis intensity, we use confirmatory factor analysis on five crisis indicators: reserves in months of imports, economic growth, financial crisis incidence, external debt and inflation growth. After verifying that factor loadings conform to theoretical expectations, we retain the first principal component.Footnote 21

Figure 3 strongly supports these scope conditions, providing suggestive evidence of a ‘glass cliff’ effect.Footnote 22 If a country undergoes an IMF programme, the likelihood of women cabinet appointments to austerity‐bearing ministries increases only under adverse societal gender norms but not otherwise. We also find that with an IMF programme, the likelihood of women cabinet appointments to austerity‐bearing ministries tends to increase for corrupt countries but not for cleaner countries.Footnote 23 Finally, there is also a significantly positive relationship between IMF programmes and women cabinet appointments when the crisis is particularly severe, but not otherwise.

Figure 3. IMF programmes, austerity‐bearing ministries and women ministers in different contexts.

Note: The figure shows the estimates for the interaction effect between IMF programmes and austerity‐bearing ministries with respect to the likelihood of a woman minister, separately for above‐mean cases of the scope condition and below‐mean cases of the scope condition.

In the online appendix, we probe the robustness of the findings in several ways and briefly report on the results here. First, we use two alternative assignments of austerity‐bearing ministries that we believe are also theoretically defendable. Our results are unchanged (Table A9). Furthermore, we ran a placebo check comparing all other ministries for which we had no theoretical expectation of the finance ministry. We find the likelihood of women cabinet appointments in these ministries to be similar, whether the country is under an IMF programme or not (Table A10). We also conduct a placebo test by assigning the ministries randomly, for which we correctly find no evidence of a glass cliff effect (Table A11). Second, we use alternative fixed effects and error clustering. Our results are similar – if not more significant – when using cabinet‐fixed effects (Table A12). We also find our results to be similar when including compound country‐year fixed effects, which effectively control for any time‐varying omitted variable at the country level (Table A13). Overall, we find support for our predictions regarding the contexts in which the ‘glass cliff’ effect should be more pronounced.

Alternative explanations and further analyses

In this remaining section, we assess alternative explanations and conduct further analyses. As a first alternative explanation, we consider that the IMF might push for more women ministers through its conditionality. However, we find no evidence for this alternative explanation. Out of the 68,770 conditions in all IMF programmes in 1980–2018, only 12 conditions mention gender and none of these conditions ask for more women to be hired in cabinets (Figure A3). We can show that most of these conditions are, in fact, about improvements in public service delivery for women and children, while none refers to government affairs.Footnote 24

A key concern is that the same ‘glass cliff’ mechanism could apply to home‐grown austerity programmes. We test this possibility by collecting data on the primary budget balance from the IMF Public Finances in Modern History database (IMF, 2023). We find that sharp declines in the budget deficit tend to increase the likelihood of a woman minister being appointed, but this effect is not consistently statistically significant. Importantly, the IMF dummy remains consistently positive, except in the fully controlled model, which suffers from a large drop in observations (Table A14). A related concern is that our findings merely pick up the political response to a financial crisis. As countries may resolve financial crises without resorting to unpopular measures that inflict adjustment burdens on the population, we would expect no glass cliff effect in this case. Indeed, the incidence of a financial crisis does not affect the appointment of women ministers (Table A15).

In addition, we demonstrate that women's cabinet representation itself does not affect the likelihood of undergoing IMF programmes. To that end, we flip our country‐year analysis so that the dependent variable becomes IMF programme participation, and our key predictor is the once‐lagged women's cabinet share. We do not find any relationship between the women's cabinet share and IMF programmes. At the same time, other well‐known predictors of IMF programmes, such as financial crisis, appear to be significant (Table A16).

We also consider that crises may increase the likelihood of women taking over the prime minister's office and seeking an IMF programme while also appointing more women into their cabinet. To test this alternative explanation, we arrange our data in a country–leader–year format, combining information about political leaders from Archigos (Goemans et al., Reference Goemans, Gleditsch and Chiozza2009) and the gender of leaders from WhoGov (Nyrup & Bramwell, Reference Nyrup and Bramwell2020). We observe whether a country is under an IMF programme in a given year and further match each IMF programme to a leader, distinguishing between inherited and own programmes. We then test whether a financial crisis triggers an IMF programme in the subsequent year, considering the gender of the leader and controlling for pre‐crisis years to ensure the common‐trends assumption is met. We do not find any differences across leaders of different genders (Table A17). Hence, we dismiss the alternative explanation that women leaders undergo IMF programmes and include women ministers in their cabinets. These additional tests strongly imply that the most plausible remaining explanation for the empirical results is the glass cliff effect.

If women are put on the glass cliff to implement seemingly unpopular policy decisions, this would be more likely where pressures to implement unpopular measures are particularly high. In a final series of tests, we exploit variations in the design of IMF programmes to probe this idea. First, we split the conditions into those pertaining to austerity‐bearing ministries and structural ministries, expecting the ‘glass cliff’ effect to appear in the former conditions but not in the latter ones. This approach is imperfect because austerity measures may be embedded within policy departments even if they address structural issues. We also know that the number of conditions is only a rough proxy for austerity (Ray et al., Reference Ray, Gallagher and Kring2022). With these caveats in mind, we confirm that women minister appointments appear more likely when IMF programmes entail more austerity‐relevant conditions but significantly less likely when IMF programmes entail more conditions in structural areas (Table A18). In addition, we draw on a repeated cross‐sectional data set of 143 IMF programmes approved between 1999 and 2012 for which fiscal adjustment measures were collected (Guimaraes & Ladeira, Reference Guimaraes and Ladeira2021). We find that where governments face higher adjustment requirements, they are significantly more likely to appoint a woman minister (Table A19).

Conclusion

This paper is motivated by a peculiar pattern: despite a longstanding lack of engagement of the IMF in facilitating gender empowerment, IMF programmes appear to increase the number of women ministers appointed in recipient countries. Building on extant literature on the glass cliff effect in management and political science, we hypothesized that women leaders are selected after an incumbent government starts an IMF programme. Using data coverting all IMF programmes from 1980 to 2018, we demonstrated that women are more likely to be appointed to cabinet positions after a country has initiated an IMF programme. To further support the existence of a ‘glass cliff’ effect, we verified that this effect is more pronounced when a country displays worse societal gender norms, a higher level of corruption and a government facing a worsening economic crisis. Importantly, we verify that neither women's leadership nor a higher share of women in government predicts a balance of payments crisis triggering an IMF programme. In line with our expectations, we also showed that women ministers are more likely to be appointed to austerity‐bearing cabinet portfolios if the government participates in an IMF programme. These findings suggest that an incumbent elite seeks to shift political responsibility for painful adjustment to women leaders.

Before discussing the implications of our work, we note several limitations. Our analysis is correlational. Although we build on the robust experimental empirical evidence from the ‘glass cliff’ literature, it is impossible to hold experiments with politically extremely responsible positions such as ministerial appointments. Furthermore, IMF programmes are politically turbulent times. Our country‐year measures will inevitably miss some high‐profile events that might influence women's appointment to ministerial positions. Still, robust empirical evidence exists for a ‘glass cliff’ effect in international politics: domestic political elites seek to shift the responsibility of internationally imposed austerity measures onto women while signalling their commitment to deep‐seated economic policy reform. Future studies could disaggregate political appointments further, such as central bank governors (as we briefly discussed Türkiye's first woman central bank governor), and uncover ‘glass cliff’ effects for these positions. Importantly, our work concentrates on women in politics; in many developing and emerging market economies, it is ethnic minorities and other marginalized groups that might be put into precarious leadership positions, defeating the purpose of greater societal inclusion and diversity. As such, we envision our contribution to help open the avenue for scholarship analysing the descriptive representation of marginalized groups during economic turmoil and hardship. We believe that more qualitative studies would be needed to uncover the interactions between different ministers and shed light on women's and these groups’ experience in selected cabinet positions.

To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first study to discuss the ‘glass cliff’ effect under internationally mandated austerity measures. Furthermore, we discuss an additional dimension of women's cabinet appointments beyond macro‐structural factors and political ideology. Our study documents a case of misuse of ‘women's empowerment’. Men elites appear to instrumentalize gender empowerment to protect insiders and scapegoat women ministers. Our findings support the notion that by appointing women to austerity‐bearing ministries in contexts of extreme vulnerability and crisis environments, insiders might weaponize recent advances in gender equality against women. When the risk of failure is substantial, social unrest is expected, and governments are likely to fail (Kern et al., Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2023; Walton & Ragin, Reference Walton and Ragin1990), and women's appointment to such ministerial positions may adversely affect their careers and create the illusion that women ministers do not succeed in high responsibility positions. Conversely, and especially if they succeed, women ministers’ visibility in politically powerful positions might help shatter some negative stereotypes against women. It might foster further belief in women's ability to govern and create a virtuous cycle (Alexander, Reference Alexander2012; Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Barnes, Chiba and O'Brien2023). In other words, women are appointed to positions that can be seen as a glass cliff, but whether they would ‘fall’ from that cliff depends on how they do during the crisis. Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that women ministers might protect jobs for women in the civil service even under IMF programmes; the proportion of women in civil service jobs when there is a woman in the cabinet does not decline as much as in the case of all‐men cabinets (Reinsberg et al., Reference Reinsberg, Kern, Heinzel and Metinsoy2024).

Our study and findings underscore the urgency of evaluating woman ministers’ performance based on contextual variables such as the depth of the economic crisis, pervasive corruption and gendered prejudices and stereotypes. Greater acknowledgment of the ‘glass cliff’ effect in all fields, including international political economy, could contribute towards a less biased and thus fairer assessment of women minister's tenure and ultimately towards greater gender equality.

Acknowledgements

We thank the EJPR editors and five anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback and comments. We are grateful for comments and suggestions from Marc Busch, Jonas Bunte, Niccolo Bonifai, Ted Lasso, Rodney Ludemar, Ning Leng, Juan Luis Manfredi, Irfan Noorudin, Pauliina Patana, Thomas Pluemper, Dennis Quinn, Nita Rudra, Carole Sargent, George Shambaugh, Erik Voeten, James Vreeland, Christian Wagner, Brigitte Young and participants at the DVPW/IPE conference in Witten/Herdecke. We thank Yash Dhuldhoya, Markandeya Karthik, and Christian Siauwijaya for their excellent research support. All errors remain ours.

Data availability statement

Replication files for the findings in this article are freely available on Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/BCXBYZ).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Online Appendix