Introduction

With rising concern over social and political polarization in Western democracies, relationships between different societal groups grow ever more important. A fundamental aspect of human communication and identity is language, and it shapes how we perceive others and ourselves. In multilingual societies, where language is a salient identification marker, it can be a source of intergroup bias. Intergroup bias refers to the tendency to favor one’s own group over other groups (so-called outgroups; Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008), encompassing beliefs about the characteristics and traits of groups or individuals based on their group membership.

Intergroup bias can have severe consequences, such as negative stereotyping (overgeneralized beliefs), which can lead to social categorization in the form of an “us versus them” mentality, thus classifying people into social groups based on attributes such as gender, ethnicity, nationality, or language (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and William1986). It can lead to prejudice (biased attitudes) and discrimination (unfair treatment) against individuals who speak different languages or belong to different language groups and hence may lead to differential treatment and access to resources based on language proficiency (Dovidio and Gaertner Reference Dovidio, Gaertner, Susan, Daniel and Lindzey2010). Moreover, intergroup bias can lead to distrust of other groups, erosion of trust in political institutions (Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilly Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021), and animosity, and hostility towards outgroup individuals (Wakefield and Wakefield Reference Wakefield and Wakefield2023), which impairs democratic dialogue and makes it more difficult for citizens to deliberate and engage with people from the other group (Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilly Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021).

This study focuses on intergroup bias between Swedish and Finnish speakers from a minority perspective in Finland. Finland is a bilingual country where Swedish speakers constitute 5.2% of the population (Saarela Reference Saarela2021). The Swedish-speaking ethnolinguistic minority in Finland is widely regarded as a strong, high-status minority due to its advantageous political, economic, and social position, and it enjoys the same statutory language rights as the Finnish-speaking majority (Bäck and Karv Reference Bäck, Karv, Himmelroos and Strandberg2020; Liebkind and Henning-Lindblom Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008). However, Swedish speakers may face difficulties using their language in interactions with public authorities and in everyday public settings (Lindell Reference Lindell2021). Despite these challenges, the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland constitutes one of the most peaceful and institutionally protected minority contexts in the world.

Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim (Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008) conducted a study on intergroup bias between language groups in Finland in 2000. Since then, Finland’s political landscape has changed markedly, particularly following the rise of the Finns Party in 2011, a party known for its critical stance toward the official status of the Swedish language. Thus, the societal climate surrounding language policy has become more contentious. This substantial change in the political climate may have increased perceived threat and thus resulted in increased intergroup bias among the Swedish-speaking minority. In recent years, Swedish speakers have increasingly reported difficulties using their language in everyday life (Lindell Reference Lindell2021), which may contribute to a heightened sense of conflict and social pressure to assimilate. Furthermore, these changes have occurred during a period characterized by increasing partisan affective polarization in most Western democracies. Although affective polarization is relatively low in Finland in an international comparison (Kawecki Reference Kawecki2022; Reiljan Reference Reiljan2020; Wagner Reference Wagner2021), the phenomenon may align with other social divisions, such as those between ethnic groups (Harteveld Reference Harteveld2021b; Mason Reference Mason2016; Mason and Wronski Reference Mason and Wronski2018).

In this study, we asked Swedish-speaking Finns to judge the applicability of positive and negative traits to their linguistic ingroup (Swedish-speaking Finns) and outgroup (Finnish-speaking Finns). Although intergroup bias is often defined as a preference for ingroup members over outgroup members (e.g., Grigoryan et al. Reference Grigoryan2022), it can manifest in different forms. These include ingroup favoritism (“we are better than them”), outgroup derogation (“they are worse than us”), outgroup favoritism (“they are better than us”), and ingroup derogation (“we are worse than them”) (Wu et al. Reference Wu2015). We acknowledge these four dynamics to emphasize that intergroup bias is not always pro-ingroup; it can also favor the outgroup or devalue the ingroup. For simplicity, and following Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim (Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008, 643), we collapse these mechanisms into two overarching categories: ingroup favoritism (which may include ingroup elevation and/or outgroup derogation) and outgroup favoritism (which may include outgroup elevation and/or ingroup derogation) (see Jost Reference Jost and Moskowitz2001, 92). This study focuses on ingroup favoritism (without distinguishing between ingroup elevation and outgroup derogation) and analyzes the specific mechanisms underlying this type of intergroup bias.

The analysis examines intergroup bias at both the aggregate and individual levels and focuses on two key explanatory factors: the strength of ethnolinguistic identity and perceived intergroup threat. Intergroup threat exists when the actions, beliefs, or characteristics of one group challenge the well-being or goal attainment of another group (Riek, Mania, and Gaertner Reference Riek, Mania and Gaertner2006). According to intergroup threat theory, perceived threats to the ingroup can strengthen one’s social identification with the ingroup and thereby increase intergroup differentiation (Riek, Mania, and Gaertner Reference Riek, Mania and Gaertner2006). Additionally, we incorporate opportunity for intergroup contact as a control variable, as it has been considered one of the most effective strategies for reducing bias and conflict between groups (see Dovidio et al. Reference Dovidio2017). The purpose of the study is to determine which variables affect intergroup bias at the individual level, thereby better understanding its causes in a minority setting. Against this backdrop, the present study seeks to answer two central research questions:

-

What is the level of intergroup bias, regarding language groups, among members of the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland? (RQ1)

-

What factors affect intergroup bias, regarding language groups, among members of the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland? (RQ2)

Despite the work by Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim (Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008), contemporary empirical research on language-based intergroup bias in Finland remains limited, particularly considering recent political developments and rising polarization. Moreover, existing studies have largely concentrated on majority group attitudes, leaving a limited understanding of how minority group members, especially those in relatively high-status positions, perceive and express bias toward the majority. Although ethnolinguistic identity and perceived threat are known to influence bias, their impact in a bilingual, high-status minority context is underexplored. The Swedish-speaking minority in Finland presents a unique case for examining this dynamic and helps fill this research gap. It is essential to explore the dynamics of intergroup bias within contexts that are socially stable yet politically contentious.

Intergroup Bias and Trait Evaluations

In this chapter, we will discuss the theoretical foundations of intergroup bias and trait evaluations with the goal of formulating several hypotheses for our first research question.

Intergroup bias can be based on numerous factors, including race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, political affiliation, or any other group identity. When such group identities constitute the basis for intergroup bias, we expect to see people stereotyping their ingroup and outgroup and expressing prejudices and animosity towards the outgroup (Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilly Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021). Intergroup bias does not only relate to beliefs about outgroups, but it is also a comparative concept involving how one views one’s ingroup relative to outgroups (Dovidio and Gaertner Reference Dovidio, Gaertner, Susan, Daniel and Lindzey2010). Social psychological research suggests that intergroup bias predominantly takes a mild form of ingroup favoritism rather than outgroup derogation (Dovidio and Gaertner Reference Dovidio, Gaertner, Susan, Daniel and Lindzey2010; Halevy, Weisel, and Bornstein Reference Halevy, Weisel and Bornstein2012; Hewstone, Rubin, and Willis Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002). Minority group members tend to express more bias in the form of ingroup favoritism than those in a numerical majority (Hewstone, Rubin, and Willis Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002; Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008; Mullen, Brown, and Smith Reference Mullen, Brown and Smith1992). Ingroup identification unconsciously raises positivity biases, leading to positive evaluations of the ingroup rather than negative evaluations of the outgroup. Subtle racism, for example, is distinguished by the absence of positive evaluations, not the presence of strong negative evaluations, of an outgroup (Hewstone, Rubin, and Willis Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002; Otten and Wentura Reference Otten and Wentura1999; Pettigrew and Meertens Reference Pettigrew and Meertens1995).

Although individuals from high-status groups are generally found to exhibit stronger intergroup bias than those from lower-status groups (Hewstone, Rubin, and Willis Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002), evidence on this relationship remains mixed, as several studies have shown that members of low-status groups may display greater ingroup favoritism (Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008; Mummendey et al. Reference Mummendey1992; Otten, Mummendey, and Blanz Reference Otten, Mummendey and Blanz1996). Several studies in social psychology emphasize the importance of perceived group salience for intergroup bias. Otten, Mummendey, and Blanz (Reference Otten, Mummendey and Blanz1996) found an increase in ingroup favoritism under conditions that threatened participants’ positive social identity. Emotions experienced in encounters with groups can be important causes of the overall reactions that individuals have to groups, and especially feeling threatened can trigger strong emotions towards a particular group (Hewstone, Rubin, and Willis Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002).

In addition to threat, Hewstone, Rubin, and Willis (Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002) mention several other key factors for intergroup bias. Firstly, ingroup identification and bias seem to be positively related. Secondly, group size, status, and power appear to matter. Studies show that groups in numerical minority express more bias than those in numerical majority (see Hewstone, Rubin, and Willis Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002, Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008). However, when ingroup identification is included, both majority and minority groups show bias (Hewstone, Rubin, and Willis Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002). Thirdly, personality and individual values, such as right-wing authoritarianism and strong religious beliefs, have been found to be positively correlated with bias and prejudice (Hewstone, Rubin, and Willis Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002).

Stereotypical representations of ingroups and outgroups are particularly relevant for our study, which will use trait ratings to measure intergroup bias. Finnish speakers and Swedish speakers in Finland have several hundred years of common history, which has resulted in cultural similarities, yet there is stereotyping of the other group on both sides (Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008). These stereotypes are akin to national stereotypes, which are “shared beliefs about the features of a typical representative of a particular nation” (Lönnqvist et al. Reference Lönnqvist2014, 272). For example, national stereotyping of Finns often describes them as quiet (Luostarinen Reference Luostarinen1997), a perception that Olbertz-Siitonen and Siitonen (Reference Olbertz-Siitonen and Siitonen2015) argue is an academic myth without empirical evidence. Stereotypes of Swedish-speaking Finns among Finnish speakers can be that they are wealthier, more culturally and intellectually oriented, and more arrogant and isolationist compared to Finnish-speaking Finns (Frackman Reference Frackman2019; Pitkänen and Westinen Reference Pitkänen and Westinen2017). Prejudices about Finnish speakers among Swedish speakers can relate to stereotypes such as them being uneducated and uncivilized (Creutz Reference Creutz2022). Earlier research has found that Swedish-speaking Finns tend to be seen as more polite, confident, and competitive than Finnish-speaking Finns, who, in turn, are viewed as more persistent (Henning-Lindblom 2012).

A peculiar aspect of linguistic stereotyping in Finland is that Finnish speakers tend to attribute more socially desirable traits to Swedish-speakers (Lönnqvist et al. Reference Lönnqvist2014) as well as harbor more negative perceptions about their own language group compared to Swedish speakers (Liebkind and Henning-Lindblom Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Tandefelt2015). Swedish speakers, on the other hand, portray their own language group more positively, which may stem from a heightened sense of being under threat due to their minority position (Liebkind and Henning-Lindblom Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Tandefelt2015; Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008). In other words, it seems more important for a minority group to elevate its own identity. Accordingly, we formulate our first hypothesis about how linguistic intergroup bias manifests among Swedish speakers (RQ1):

H1: Swedish speakers will display intergroup bias against Finnish speakers in the form of ingroup favoritism.

Moreover, prior studies suggest that intergroup bias is often asymmetric across positive and negative traits (called PNAE: Positive-Negative Asymmetry Effect) so that respondents tend to display less bias when rating groups on negative compared to positive evaluation scales (Liebkind and Henning-Lindblom Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Tandefelt2015; Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim 2006; Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008; Otten, Mummendey, and Blanz Reference Otten, Mummendey and Blanz1996). It seems less normatively accepted to attribute negative characteristics to outgroups, and societal norms of tolerance and equality encourage the differentiation through positive traits (Spears and Tausch Reference Spears, Tausch, Hewstone, Stroebe and Jonas2012). Previous research, however, shows that group size may moderate this asymmetry. Minorities tend to display intergroup bias on both kinds of traits when so-called aggravating conditions are present (Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008): if the intergroup context increases the need for positive distinctiveness, e.g., due to the minority group’s numerical inferiority or low status, this asymmetry in trait evaluations can be expected to become less salient (Hewstone, Rubin, and Willis Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002; Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim 2006; Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008; Otten and Mummendey Reference Otten, Mummendey, Capozza and Brown2000). Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim (2006; Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008) found that intergroup bias appeared not only in the positive one (ingroup favoritism in the attribution of positive traits) but also in the negative stimulus condition (outgroup derogation in the attribution of negative traits). Crisp and Hewstone (Reference Crisp and Hewstone2001) also found more intergroup bias in the negative than in the positive domain when the ingroup (English) was a numerical minority (in Wales).

Because the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland is arguably a high-status minority (Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2006, 266) existing in a context with less aggravating conditions, the typical asymmetrical intergroup bias in trait ratings can be expected. According to theoretical assumptions, ingroup identification unconsciously raises positivity biases, leading to positive evaluations of the ingroup rather than negative evaluations of the outgroup (Hewstone, Rubin, and Willis Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002; Otten and Wentura Reference Otten and Wentura1999; Pettigrew and Meertens Reference Pettigrew and Meertens1995). Hence, we expect people to assign more positive evaluations of the ingroup rather than negative evaluations of the outgroup. Building on this logic, our second hypothesis is:

H2: We expect that the degree of ingroup favoritism is contingent upon trait valence, such that bias will be stronger for positive traits than for negative traits.

In the following section, we turn to the mechanisms that we expect to have an impact on intergroup bias with the goal of formulating hypotheses pertaining to our second research question about factors associated with intergroup bias, specifically the role of ingroup identification and perceived threats from the outgroup.

Language as a Social Identity

Research on intergroup bias often starts with social identity theory (SIT) (see e.g., Grigoryan et al. Reference Grigoryan2022; Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and William1986). In contemporary social science research, identity is a highly prevalent concept that is utilized in diverse ways to gain insight into how individuals perceive themselves and are characterized by others. Tajfel and Turner (Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and William1986) identified three mental processes for shaping a social identity: 1) social categorization (distinguishing between “us” and “them”), 2) social identification (identifying with the group we belong to), and 3) social comparison (seeing our own group more favorably than others).

People can identify with several different groups, ranging from their gender, ethnicity, and religion to their professional group or even their favorite football team (Grigoryan et al. Reference Grigoryan2022). The SIT stipulates that people have a need for positive social identity, thus wanting to contrast their ingroups favorably with any outgroups, as people seek to establish a sense of self-worth and self-esteem through the social groups to which they belong (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and William1986). There is vast evidence that simply randomly categorizing people into two subgroups prompts people to favor those in their own group above those in the other group; thus, intergroup bias may emerge because of any perceived group division (Messick and Mackie Reference Messick and Mackie1989). Here, we are interested in group division based on language.

Language is a fundamental aspect of human connection and identity; therefore, the shared social identity for many language groups is built around language. Language is a clear marker to distinguish “us” from “them” (social categorization), but it can also be a source of social identification, as is the case for Swedish speakers in Finland. Empirical research shows that the Swedish language is a central part of the identity of Swedish-speaking Finns (Sundback Reference Sundback, Sundback and Nyqvist2010). For minorities, ethnic identity can become more salient due to their position in society, leading to greater awareness and expression of their ethnic background. Whereas a linguistic minority is generally defined by language use alone, an ethnolinguistic minority is characterized by a shared sense of cultural, historical, and often territorial identity that is closely intertwined with language but extends beyond it (Giles and Johnson Reference Giles and Johnson1987; Liebkind and Henning-Lindblom Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Tandefelt2015). An ethnic identity encompasses multiple aspects, including self-identification, a sense of belonging and commitment to the group, shared values, and attitudes towards one’s own ethnic group. Members of an ethnic group believe they share a common ancestry and distinctive cultural traits or practices (Liebkind Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2006).

An ethnolinguistic identity is distinct from other social identities, including language identity, in that ethnicity relates to people’s subjective perceptions of their origins (Liebkind and Henning-Lindblom Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Tandefelt2015). These subjective perceptions of a shared ancestry make ethnic identities highly enduring and result in a deep sense of solidarity (Liebkind and Henning-Lindblom Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Tandefelt2015). According to ethnolinguistic identity theory, when language is a salient component of identification, individuals may strive for a positive psychological distinctiveness along ethnolinguistic dimensions and use strategies to promote linguistic differentiation (Vincze and Henning-Lindblom Reference Vincze and Henning-Lindblom2016). As ethnolinguistic identity theory is an offspring of social identity theory (Vincze and Henning-Lindblom Reference Vincze and Henning-Lindblom2016), the strive for a positive distinctiveness is a broader psychological process as originally proposed by social identity theory. This general drive for a positive group identity is, in the context of ethnolinguistic identity theory, channelled through linguistic dimensions when language is a salient component of group identification (Giles and Johnson 1987).

Previous research on intergroup bias towards Finnish speakers among Swedish-speaking Finns has shown that the latter show both ingroup favoritism and outgroup derogation, and that the level of intergroup bias is higher for individuals with a strong ingroup identity (Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2006). However, although these studies examined the impact of ingroup identification (e.g., “I consider myself to be a member of the ingroup”) on intergroup bias, they do not explicitly measure the relationship between ethnolinguistic identity and intergroup bias. Against this backdrop, because language constitutes a central marker for group identity and, in turn, for intergroup bias, our third hypothesis is:

H3: Individuals with a stronger ethnolinguistic identity will exhibit higher levels of intergroup bias than individuals with a weaker ethnolinguistic identity.

Intergroup Threat Theory

Riek, Mania, and Gaertner (Reference Riek, Mania and Gaertner2006, 336) write that “[…] intergroup threat occurs when one group’s actions, beliefs, or characteristics challenge the goal attainment or well-being of another group.” Intergroup threat theory (a revised version of integrated threat theory; see Rios, Sosa, and Osborn Reference Rios, Sosa and Osborn2018; Stephan and Stephan Reference Stephan and Stephan1996) may partly explain the level of intergroup bias (Riek, Mania, and Gaertner Reference Riek, Mania and Gaertner2006). Even a sense of intergroup threat can be linked to greater intergroup bias (Liebkind and Henning-Lindblom Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Tandefelt2015; Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008). The theory refers to perceived or anticipated threats that individuals or groups sense from members of other social groups. Threats can manifest in various forms, such as economic, political, or cultural threats. When an individual or a group feels threatened by an outgroup, they may develop negative attitudes and prejudices towards that group. Whereas the focus of social identity theory is primarily on the ingroup and how identification with it creates positive emotions (Rios, Sosa, and Osborn Reference Rios, Sosa and Osborn2018; Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and William1986), intergroup threat theory focuses on the nature of threats from the outgroup (Rios, Sosa, and Osborn Reference Rios, Sosa and Osborn2018). Members of a group perceive intergroup threats when another group can cause them harm (Stephan, Ybarra, and Morrison Reference Stephan, Ybarra, Morrison and Todd2015). Threats can be realistic (e.g., concerns of physical harm, loss of resources) or symbolic (e.g., concerns about the validity of the ingroup meaning system) (Esses, Jackson, and Armstrong Reference Esses, Jackson and Armstrong1998; Stephan, Ybarra, and Morrison Reference Stephan, Ybarra, Morrison and Todd2015). Intergroup threat theory emphasizes that the mere perception of threats (i.e., the realistic and symbolic threats need not be real) is enough to affect intergroup bias (Rios, Sosa, and Osborn Reference Rios, Sosa and Osborn2018).

Because the language climate in Finland has deteriorated in the last ten years, particularly in media and national politics, and the Swedish-speaking minority has faced discrimination and prejudices from the Finnish-speaking majority many times (Lindell Reference Lindell2021; Lindell et al. Reference Lindell2023), we expect that Swedish-speaking minority members may feel threatened or have perceptions of negative intent by the majority group. A slowly decreasing size of the Swedish-speaking minority group in Finland might be causing a less favorable language climate in the group and might cause the minority members to face pressure to assimilate and hence affect the level of intergroup bias (Lindell et al. Reference Lindell2023). On an individual level, threatening experiences from contact with the outgroup can cause intergroup bias (Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2006). Accordingly, our fourth hypothesis is:

H4: Individuals who perceive a higher level of intergroup threat will exhibit higher levels of intergroup bias than individuals with a lower level of perceived intergroup threat.

Swedish-Speaking Finns as a Case

This study analyzes intergroup bias between Swedish speakers and Finnish speakers from a minority perspective. Finland is home to two primary linguistic communities: the Finns, who speak Finnish, and the Swedish-speaking Finns, who primarily speak Swedish. Although both Finnish and Swedish hold national language status in Finland, only a numerical minority of Finnish citizens, approximately 290,000 individuals, or 5.2% of the population, speak Swedish (Saarela Reference Saarela2021). The share of the population in Finland with another mother tongue than Finnish or Swedish was 10.8% in 2024, with the largest other language groups being Russian (1.8%), Estonian (0.9%), and Arabic (0.8%) (Statistics Finland 2025).

We conceptualize Swedish-speaking Finns as an ethnolinguistic minority because the Swedish language is a fundamental, defining component of a broader collective identity linked to history and culture (Liebkind and Henning-Lindblom Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Tandefelt2015). Beyond legal recognition as one of Finland’s national language groups, Swedish speakers maintain a culturally distinct community supported by a dense network of institutional structures (e.g., Swedish-language schools, media, churches, and civil society organizations), that may reinforce this shared identity. Consistent with this view, research has shown that many Swedish-speaking Finns identify as belonging to a distinct ethnocultural community rather than merely as Finnish citizens who speak a different language (Allardt and Starck Reference Allardt and Starck1981).

Previous research shows that Swedish-speaking Finns exhibit high levels of social capital and trust, not only in international comparisons but also when compared to the majority-language speakers (Sundback Reference Sundback, Sundback and Nyqvist2010). Swedish-speaking Finns are a small group with close networks, a strong ethnolinguistic identity, and biases towards their own language group (Liebkind and Henning-Lindbolm Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Tandefelt2015), as well as a consensus-oriented political culture and typically low partisan hostility (Kawecki Reference Kawecki2022). In Finland, efforts have been made to secure the position of the Swedish-speaking minority through cultural and institutional arrangements, which support the minority culture and the linguistic and social cohesion. Because of this, despite their small numbers, the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland is often portrayed as a “high-status,” “positive,” or “strong” minority (Bäck and Karv Reference Bäck, Karv, Himmelroos and Strandberg2020; Liebkind and Henning-Lindblom Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008). Overall, the intergroup relationship between Finnish speakers and Swedish speakers is generally characterized as harmonious and amicable, especially when compared to many other minority–majority contexts (Vincze and Henning-Lindblom Reference Vincze and Henning-Lindblom2016).

Yet, the last decade has seen a deteriorated language climate, poor access to services in Swedish, and a harder tone of social and political debate (Lindell Reference Lindell2021; Suominen Reference Suominen2017). These challenges have prompted an examination of the potential language-based intergroup bias. In comparison with affective polarization between political groups, we expect to find that language-based intergroup bias between ethnolinguistic groups is smaller, because previous research has shown that people tend to express more hostility towards political outgroups (i.e., groups based on political opinions) than with non-political outgroups (i.e., groups based on, for example, urbanity, education, ethnicity) (Harteveld Reference Harteveld2021a; Westwood et al. Reference Westwood2018). Swedish-speaking Finns can thus be seen as an interesting case for analyzing intergroup bias from a minority perspective.

Method

Sample

We use data from a 2022 online survey administered through the Barometern panel, which is recruited using probability-based sampling. The panel’s population consists of Swedish-speaking Finns aged 18 years and above from the entire country (including the Åland Islands). This panel is part of the Finnish Research Infrastructure for Public Opinion (FIRIPO). All respondents in the Barometer online panel are officially registered as Swedish speakers by the authorities.

For the analyses of intergroup bias, we included only respondents who completed the full set of trait evaluations for both language groups. This yielded a sample of 1,096 individuals for the descriptive analyses. However, due to listwise deletion resulting from missing data on key independent variables, the sample size for the regression models is smaller (n = = 698). For the descriptive analyses, post-stratification weights adjusted for gender, age, region, and education level are applied to be representative of the Swedish-speaking population in Finland. However, for regression analyses, weights are discarded to avoid inflating standard errors and introducing bias from weights not designed for causal inference (see Winship and Radbill, Reference Winship and Radbill1994). Descriptive statistics for the sample, along with weighted and unweighted comparisons to the Swedish-speaking population in Finland to assess representativeness, are provided in Appendix Table A1.

Furthermore, we integrated data and variables from earlier waves spanning 2019–2022 to examine the predictors of this intergroup bias. To categorize Swedish-speaking Finns into the ingroup, we relied on their self-identification as either Swedish or bilingual (Swedish/Finnish). Self-identification was valid here, given the significant role language plays as a social identity for both Swedish-speaking Finns and bilingual individuals. Although a large part (53%) of the respondents identify as bilinguals, a large majority considered their language important or very important for their identity: 92% of Swedish speakers and 85% of bilingual respondents. Although our data does not allow us to control for Finnish identity markers, the survey panel consists exclusively of Swedish-speaking Finns (with Swedish as their registered mother tongue), and the strong attachment to Swedish among bilinguals suggests that these groups can be meaningfully analyzed together. However, we acknowledge that bilingual individuals may hold multiple ethnolinguistic identities and could potentially differ from unilingual Swedish speakers in meaningful ways. This kind of double or multiple identity, which embraces a national identity as an “umbrella” identity, seems to be representative of Swedish speakers in Finland (see Henning-Lindblom and Liebkind Reference Henning-Lindblom and Liebkind2007; Liebkind and Henning-Lindblom Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Tandefelt2015; Lojander-Visapää Reference Lojander-Visapää2008). Bilinguals might also be well-connected to the Finnish-speaking community. To account for this possibility, we include language identity (unilingual vs. bilingual) as a control variable in our regression models. However, excluding bilinguals from the analysis would make the sample less representative for Swedish-speaking Finns.

The analysis is limited to intergroup bias among Swedish-speaking Finns, as comparable data from Finnish-speaking Finns were not available. Importantly, respondents did not evaluate themselves as individuals but were asked to assess both their own linguistic ingroup (Swedish-speaking Finns) and linguistic outgroup (Finnish-speaking Finns). Therefore, our measurement captured prejudices (perceived traits) about both groups; intergroup bias involves stereotyping members of the ingroup as well as those of the outgroup (Renström, Bäck, and Carroll Reference Renström, Bäck and Carroll2023).

Measures

Trait Ratings

Despite the absence of a universally accepted “gold standard” for measuring intergroup relations, as Renström, Bäck, and Carroll (Reference Renström, Bäck and Carroll2023, 17) note, there are various methods available for assessing intergroup bias. Feeling thermometers and like-dislike scales are common approaches to measuring attitudes towards a group, as social distancing measures can assess how comfortable individuals are with having interpersonal relations with members of outgroups (Renström, Bäck, and Carroll Reference Renström, Bäck and Carroll2022). However, Renström, Bäck, and Carroll (Reference Renström, Bäck and Carroll2022) argue that trait measures are more precise than feeling thermometers and social distance measures. Trait ratings can be used to measure intergroup bias by assessing the degree to which individuals associate positive or negative traits with members of their own group versus members of the opposing outgroup (Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008). Trait ratings have less variability and capture general attitudes better than social distance measures do (Renström, Bäck, and Carroll Reference Renström, Bäck and Carroll2023) and have been deemed as optimal for understanding citizens’ prejudicial feelings and self-images (Druckman and Levendusky Reference Druckman and Levendusky2019). We therefore assess the level of intergroup bias among Swedish-speaking Finns by examining trait ratings using measures similar to those used in previous research (e.g., Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008; Renström, Bäck, and Carroll Reference Renström, Bäck and Carroll2021).

Traits and Valence

To measure intergroup bias, Swedish-speaking respondents rated how well 15 traits described (a) their linguistic outgroup, Finnish-speaking Finns, and (b) their linguistic ingroup, Swedish-speaking Finns. The wording for the ingroup evaluation was: “How well do you feel the following traits describe persons who are Swedish speaking? Please indicate your answer on a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 = does not describe at all, 7 = describes very well.” The evaluation of the outgroup consequently asked, “How well do you feel the following traits describe persons who are Finnish speaking? Please indicate your answer on a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 = does not describe at all, 7 = describes very well.” After completing these evaluations, they assessed the valence of each trait, whether it was perceived as positive or negative, on a 7-point scale (1 = completely negative, 7 = completely positive). This order of rating was chosen to avoid priming respondents to think of the traits as positive or negative when evaluating ingroup and outgroup members.

The list of traits was adapted from Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim (Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008), with the number of traits reduced from 21 to 15 to streamline the survey. Following the approach of Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim (Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008) and Henning-Lindblom (Reference Henning-Lindblom2013), the traits were selected to capture perceptions of competence and warmth. Competence-related traits include confident, diligent, well-read, intelligent, straightforward, restricted, prejudiced, and assertive. Warmth-related traits include calm, open, thoughtful, reliable, aggressive, selfish, and talkative (see also Abele et al. Reference Abele2008).

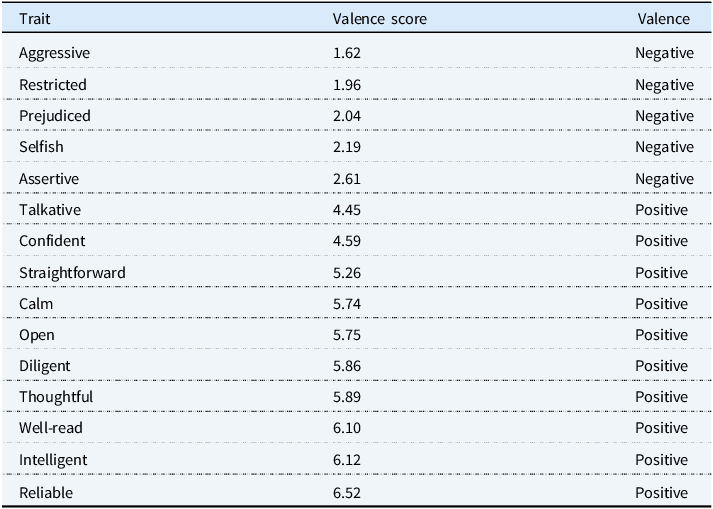

Trait valence was classified using a neutral midpoint of 4, with mean scores below 4 indicating negative traits and scores above 4 indicating positive traits. This classification yielded ten positive and five negative traits, all significantly different from the neutral value (p < .001). The positive traits were talkative (4.45), confident (4.59), straightforward (5.26), calm (5.74), open (5.75), diligent (5.86), thoughtful (5.89), well-read (6.10), intelligent (6.12), and reliable (6.52). The negative traits were aggressive (1.62), restricted (1.96), prejudiced (2.04), selfish (2.19), and assertive (2.61). The traits and their valence are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Trait valence

Note. Trait valence was evaluated across the full sample (N = 2,129).

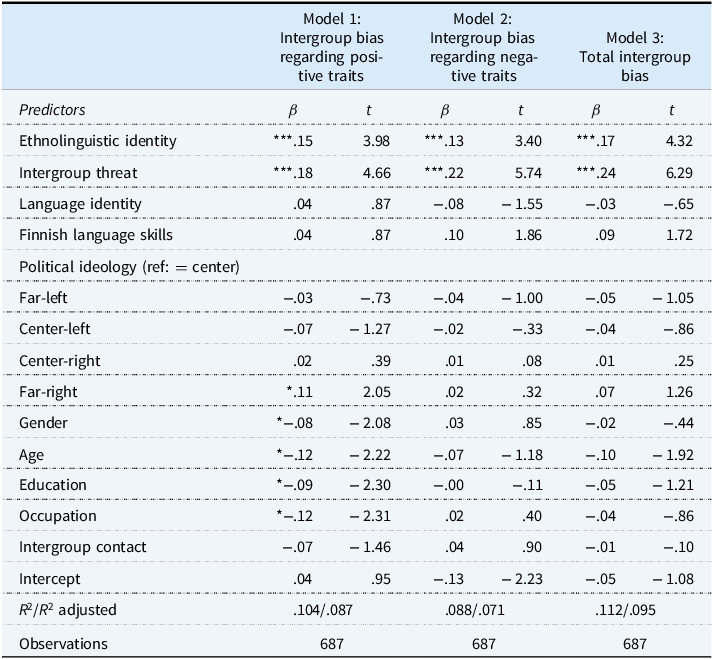

Table 2. Linear regression models predicting intergroup bias

Note. ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05. The number of observations is smaller than in the previous analyses due to missing data on some of the independent variables collected in earlier survey waves. A post hoc power analysis for multiple regression (conducted with G * Power 3.1.9.7) indicated a statistical power of .99 for N = 687 and 13 predictors, assuming α = .05 and a small-to-medium effect size of f 2 = 0.05. In a test for multicollinearity, the models had variance inflation factors (VIF) in an acceptable range of 1.11–2.31.

Dependent Variables

The measurement of intergroup bias proceeded in two analytical steps. First, we analyze the aggregate level of intergroup bias (RQ1), i.e., trait-level differences across all 15 traits, to assess whether Swedish-speaking respondents, on average, evaluated their in-group (Swedish speakers) and the out-group (Finnish speakers) differently. To identify which traits reflected significant intergroup bias, we then compared the mean ratings for each trait between the in-group and the out-group and calculated mean differences for each comparison.

Secondly, these individual trait biases were combined into indices, which serve as the dependent variables for the individual-level analysis (RQ2). This was achieved by calculating the differences between ratings for the ingroup and outgroup for each trait. As a result, the measurement of intergroup bias at the individual level is based on three dependent variablesFootnote 1 : (1) intergroup bias regarding positive traits, (2) intergroup bias regarding negative traits, and (3) total intergroup bias (combination of negative and positive traits).

The final individual-level index ranges from −6 to 6. A value of 0 indicates that the respondent had no bias and assigned traits with the same intensity to both the ingroup and outgroup. An index larger than 0 indicates that the respondent exhibited bias in favor of their ingroup, suggesting a tendency to associate positive traits more with their ingroup or negative traits more with their outgroup. Conversely, an index less than 0 indicates that the respondent demonstrated outgroup favoritism and was inclined to perceive positive traits as more characteristic of the outgroup or negative traits as less characteristic of their outgroup than their ingroup.

Independent Variables

For a detailed description of these variables, including measurements, corresponding questions, and response scales, refer to the Appendix (Table A3).

Strength of ethnolinguistic identity was measured with the following questions: “How important is your language to your identity?” The response scale was a 5-point Likert scale with 0 indicating “not at all important” and 5 indicating “very important.”

Perceived intergroup threat was measured with three items on a four-point scale (see Appendix, Table A4, for descriptive statistics and Cronbach’s alpha): “I think that Finnish speakers want to keep to themselves, and they show no interest in the Swedish-speaking population,” “I think that the attitudes among Finnish speakers towards Swedish speakers in Finland have deteriorated in the last two years,” and “If I use Swedish, I am seen as a second-class citizen.” Our measures of intergroup threat focus on the level of hostility that the respondent perceives from the outgroup. Within the framework of intergroup threat theory, hostility might serve as a first signal of threatening behavior and give rise to similar emotional and behavioral responses. We therefore treat perceived outgroup hostility as a symbolic threat. The scale demonstrated acceptable, though moderately low, internal consistency (α = .64).

Language identity was measured with the following statement: “Do you feel that you are Swedish speaking/Bilingual?”

Control Variables

Additionally, our analysis incorporated several control variables, including gender, age, education, and occupation (Han Reference Han2022; Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim 2006; Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008; Renström, Bäck, and Carroll Reference Renström, Bäck and Carroll2021).

Previous research has examined several factors to explore individual-level intergroup bias. These factors include political ideology (Vaes Reference Vaes2023), outgroup language proficiency (Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2006), and intergroup contact (Allport Reference Allport1954). Intergroup bias between language groups can decrease outgroup derogation when second-language confidence increases (Shulman and Clement Reference Shulman and Clément2008). Earlier studies have found that outgroup language proficiency affects intergroup bias between language groups (Harwood, Giles, and Bourhis Reference Harwood, Giles and Bourhis1994; Landry and Bourhis Reference Landry and Bourhis1997). However, in a setting like ours, Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim (Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2006) found that outgroup language proficiency did not affect intergroup bias among Swedish-speaking Finns. However, studies on the attitudes towards Swedish speakers among the majority group of Finnish speakers in Finland have found that language proficiency is of importance, and better language skills are associated with more positive attitudes towards the minority (Karv Reference Karv, Karv and Backström2022; Himmelroos and Strandberg Reference Himmelroos, Strandberg, Himmelroos and Strandberg2020).

A robust finding in the literature (see Pettigrew and Tropp Reference Pettigrew, Tropp and Oskamp2000) is that positive interactions with the outgroup improve intergroup relations, a phenomenon known as the contact hypothesis (Allport Reference Allport1954). Having personal contact with members of the outgroup reduces intergroup bias and creates positive feelings towards the outgroup (see Dovidio et al. Reference Dovidio2017). The contact hypothesis has gained support from research on attitudes between language groups in Finland (Himmelroos Reference Himmelroos, Himmelroos and Strandberg2020; Karv Reference Karv, Karv and Backström2022; Lindell et al. Reference Lindell2023; Mäkinen and Nortio Reference Mäkinen and Nortio2020). The share of Finnish speakers in a municipality is used as a proxy for the opportunity for intergroup contact, as a high share of Finnish speakers may force intergroup contact with the outgroup.

Research on affective polarization, a specific form of intergroup bias, shows that political ideology (here measured on the self-assessed left-right dimension) shapes polarization at the individual level, with individuals holding more extreme political attitudes tending to be more polarized (Berg et al. Reference Berg2025; Harteveld Reference Harteveld2021a; Reiljan, and Ryan Reference Reiljan and Ryan2021; Renström, Bäck, and Carroll Reference Renström, Bäck and Carroll2021). It is possible that political ideology is related to threat perception and thus affects intergroup bias (Renström, Bäck, and Carroll Reference Renström, Bäck and Carroll2023).

Results

Intergroup Bias on the Aggregate Level

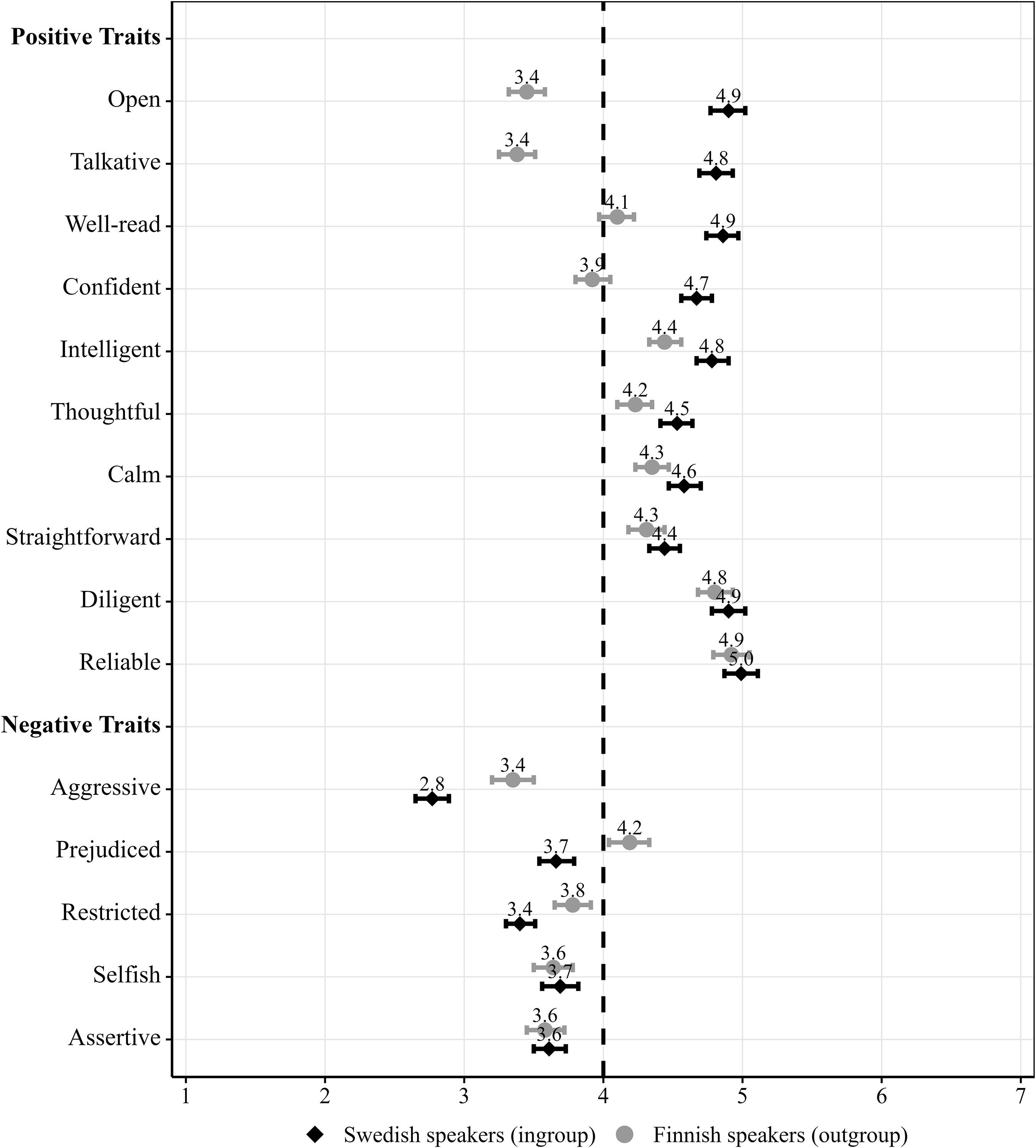

In this section, we present the findings regarding intergroup bias on the aggregate level. We do this by illustrating how Swedish-speaking Finns attribute the 10 positive traits and 5 negative traits to both the ingroup (Swedish speakers) and the outgroup (Finnish speakers). We first compare the mean ratings for each trait between the two groups and then assess whether these differences are statistically significant using paired-sample tests. The aggregate-level results are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Aggregate-level intergroup bias for positive and negative traits.

Note. Weighted data (N = 1087). The points in the figure represent the mean scores for each trait. Swedish speakers (ingroup) are shown as diamonds and Finnish speakers (outgroup) as circles. Horizontal lines denote 95% confidence intervals. The vertical dashed line marks the neutral midpoint (4).

The results show that Swedish speakers evaluate their own group more positively than Finnish speakers on most traits, indicating a general tendency toward ingroup favoritism. For positive traits, significant mean differences emerge for Calm (MD = .23, p = .001), Thoughtful (.30, p < .001), Intelligent (.34, p < .001), Confident (.75, p < .001), Well-read (.76, p < .001), Talkative (1.43, p < .001), and Open (1.45, p < .001). However, no statistically significant differences are found for the positive traits Reliable, Diligent, and Straightforward. For negative traits, the direction of the bias is reversed, as lower mean scores indicate a more positive evaluation. Swedish speakers rate their own group as less Restricted (.38, p < .001), Prejudiced (.53, p < .001), and Aggressive (.58, p < .001) than Finnish speakers. Differences for Assertive and Selfish are small and not statistically significant.

Thus, Swedish speakers consistently attribute more favorable positive traits to their own group and less favorable negative traits to Finnish speakers, although the strength of this pattern varies across traits. Overall, these findings partly support Hypothesis 1: Swedish speakers display intergroup bias in the form of ingroup favoritism across several traits, with significant differences in 10 of 15 traits. However, although statistically significant, these differences are modest in degree, indicating that the overall level of bias remains relatively limited.

Intergroup Bias on the Individual Level

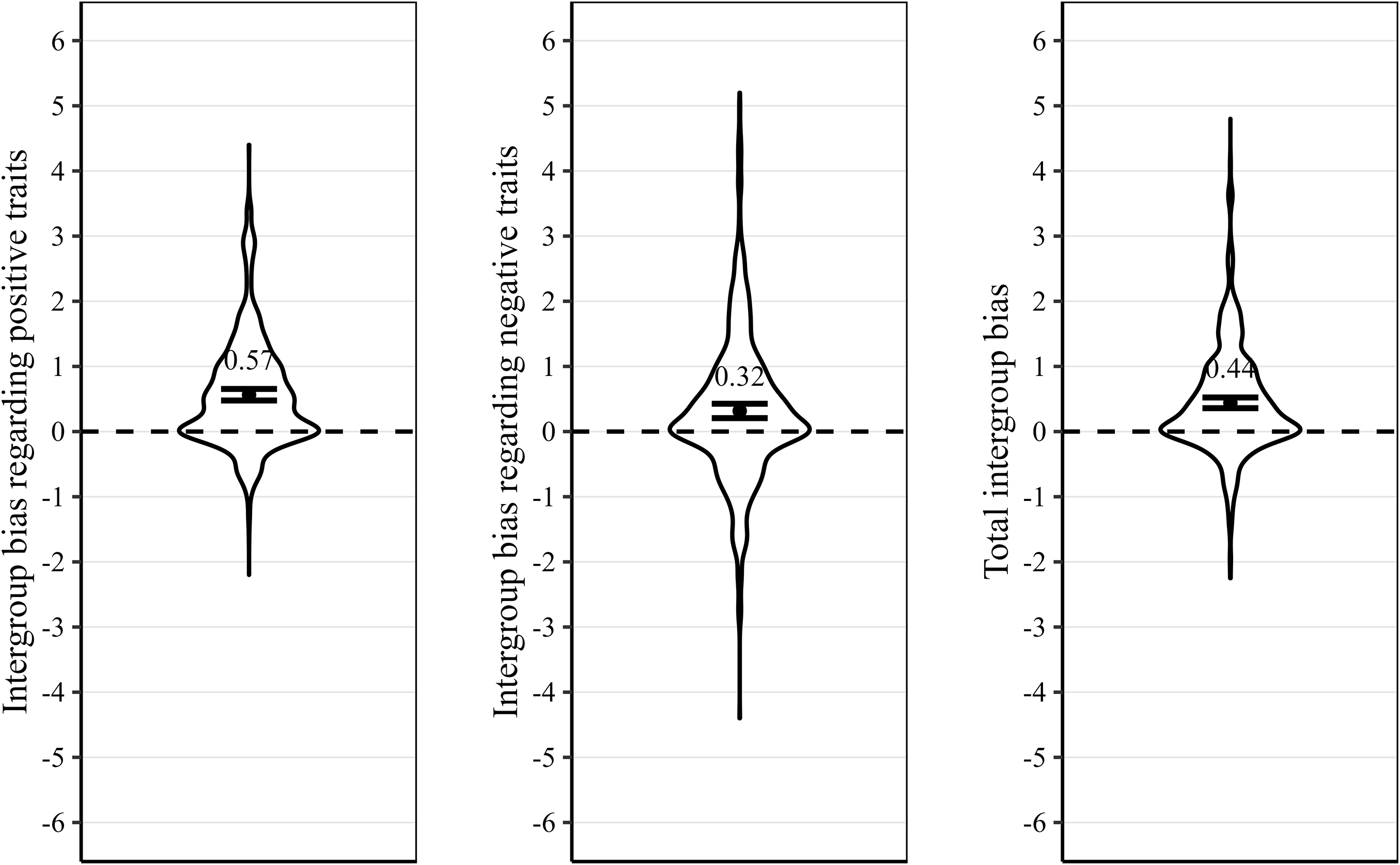

We now turn to examining the level of intergroup bias on an individual level. The individual-level index of intergroup bias spans from −6 to 6, where a score of 0 denotes the absence of bias, indicating an equal trait rating of both groups. Positive values for both positive and negative traits signify the presence of ingroup favoritism, whereas negative values indicate outgroup favoritism. Figure 2 displays the distribution of these indices for the ten positive traits, the five negative traits, and all traits combined.

Figure 2. Individual-level intergroup bias across indices.

Note. Weighted data (N = 958). Points represent weighted means and lines 95% confidence intervals. The horizontal dashed line indicates the neutral point (0).

The results show that the mean individual-level intergroup bias for positive traits is 0.57, for negative traits is 0.32, and the total intergroup bias is 0.44. These results reinforce the aggregate findings, indicating that ingroup favoritism is more pronounced for positive traits than for negative traits. In other words, respondents tend to assign more positive traits to their ingroup than to the outgroup while being less differentiated on undesirable traits. Nevertheless, the mode across all distributions is zero, suggesting that many respondents did not exhibit intergroup bias. Moreover, outgroup favoritism, that is, more favorable ratings of the outgroup, appears more common for negative traits. To formally assess whether the strength of intergroup bias in the form of ingroup favoritism varies by positive and negative traits (H2), we conducted a paired comparison between the positive and negative bias indices. The results indicate that ingroup favoritism is significantly stronger for positive traits (M(diff) = .25, 95% CI [.13, .36], t(991) = 4.25, p < .001). This finding supports Hypothesis 2, suggesting that the degree of favoritism is contingent upon trait valence, such that bias is stronger for positive traits than for negative traits.

Predictors of Intergroup Bias

Next, to explain the level of intergroup bias on an individual level, we used regression analysis to explore the predictors of individual-level intergroup bias to address the third and fourth hypotheses. In the regression model, we have three models: 1) intergroup bias regarding positive traits, 2) intergroup bias regarding negative traits, and 3) total intergroup bias. All independent variables were rescaled to range between 0 and 1, and standardized beta coefficients are reported.

As shown in all three of our models depicted in Table 2 above, across all three models, the strength of ethnolinguistic identity had a statistically significant effect on the individual level of intergroup bias (β = .13–.17, p < .001)Footnote 2 . The effect was somewhat stronger in the model predicting bias regarding positive traits than in the model for negative traits. Thus, the findings provide support for Hypothesis 3: respondents who viewed their language as an important part of their identity displayed significantly stronger ingroup favoritism. Likewise, perceived intergroup threat had a statistically significant effect on the individual level of intergroup bias across all three models (β = .18–.24, p < .001). The effect is stronger when explaining bias regarding negative traits. Consistent with expectations, individuals who experienced higher levels of perceived threat displayed stronger intergroup bias in the form of ingroup favoritism, thereby confirming Hypothesis 4.

Regarding language identity, we expected that bilingual respondents would be less prone to show intergroup bias than unilingual Swedish speakers due to more opportunity for intergroup contact. Yet, this was not the case; language identity did not have any effect on intergroup bias. Similarly, outgroup language proficiency (Finnish language skills) did not seem to matter either. However, our results corroborate the findings by Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim (Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2006), who did not detect any effect of outgroup language proficiency on intergroup bias.

Turning to political ideology (left-right dimension), most ideological positions did not differ significantly from the centrist reference group. Respondents identifying as far-right exhibited significantly greater bias regarding positive traits (β = .11, p < .05). However, this effect did not extend to bias regarding negative traits or total bias.

Among the control variables, several small but noteworthy patterns appeared. Women, younger respondents, and those with lower education and not employed tended to show slightly higher levels of ingroup favoritism in Model 1, though these effects were weak or nonsignificant in the other models. Intergroup contact, operationalized as the proportion of Finnish speakers in the respondent’s municipality, is not significantly associated with intergroup bias.

Altogether, the explanatory power of the models was modest but meaningful. Based on the adjusted R-squared values, our models explained 8.7%, 7.1%, and 9.5% of the variation in intergroup bias measured with trait ratings. The combined findings indicate that although ethnolinguistic identity and perceived threat are key predictors, a substantial share of the variation in intergroup bias remains unexplained.

Discussion

The purpose of this article was to examine the level of intergroup bias in personality trait evaluations and to identify factors that explain variation of the level of intergroup bias at the individual level. We examined intergroup bias between Swedish-speaking and Finnish-speaking Finns from the perspective of a high-status minority group within a bilingual national context. Building on previous research on ethnolinguistic identity and stereotyping (e.g., Henning-Lindblom Reference Henning-Lindblom2013; Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008; Renström, Bäck, and Carroll Reference Renström, Bäck and Carroll2021), we used personality trait ratings as a measure of stereotyping, distinguishing between bias in relation to positive and negative traits. In doing so, we aimed to advance understanding of the factors that drive intergroup bias in minority contexts.

At the aggregate level, Swedish-speaking Finns rated their ingroup more positively than the Finnish-speaking outgroup, indicating ingroup favoritism. Of the 15 traits we analyzed, we found intergroup bias in ten. The intergroup bias was more pronounced for positive traits (e.g., open) than for negative traits (e.g., aggressive), a finding only partly consistent with previous research (Liebkind and Henning-Lindblom Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Tandefelt2015; Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim 2006; Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008; Otten, Mummendey, and Blanz Reference Otten, Mummendey and Blanz1996). Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim (2006; Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008) and Liebkind and Henning-Lindblom (Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Tandefelt2015) found support for the so-called “aggravating hypothesis” regarding group size; among numerical minorities, intergroup bias was more pronounced for negative traits, and the PNAE (Positive-Negative Asymmetry Effect—less bias in negative than in positive domains) was not found. In contrast, we observed PNAE, with less bias toward negative than positive traits. This aligns with theoretical expectations suggesting that ingroup identification leads to positive evaluations of the ingroup rather than negative evaluations of the outgroup. The discrepancy in these results may stem from methodological differences. We did not compare the majority and minority groups or several minority groups with each other. Moreover, they included only the five most positive and the five most negative traits in their analysis, whereas our analyses included the full set of traits. We found the strongest bias for the characteristics “open” and “talkative,” which were not among the five most positive traits.

Swedish speakers seem to favor their ingroup on both competence and warmth. In a context where equality is a central societal value (like in the Nordic countries), there might be some reluctance to differentiate the groups on competence traits. However, in line with Henning-Lindblom (Reference Henning-Lindblom2013), we found that the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland (a high-status group in a minority position) favored the ingroup also on competence traits. High-status groups might show intergroup bias when facing the possibility of losing a positive social identity. For the Swedish-speaking Finns, a potential decline in demographic vitality, as well as the fear of losing their position in society (see also Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008), might be contextual factors that heighten sensitivity to identity threat, even in an egalitarian society such as Finland. The emergence of the Finns Party and their negative view towards the status of the Swedish language has affected the political and societal climate, as well as the public debate, potentially amplifying sensitivity to identity threat.

Consistent with findings by Lönnqvist et al. (Reference Lönnqvist2014), Swedish-speaking Finns’ aggregate-level ratings resembled stereotypical personality differences between the two groups (e.g., that Swedish speakers are more open and talkative and less aggressive). Swedish-speaking Finns’ stereotyping of Finnish speakers largely followed the expected path, as they viewed their ingroup as more intellectually oriented, more talkative, and more confident (Henning-Lindblom 2012; Pitkänen and Westinen Reference Pitkänen and Westinen2017). In general, the patterns were that Swedish speakers are evaluated as extroverted and Finnish speakers as more introverted, in line with previous studies (Lönnqvist et al. Reference Lönnqvist2014) and confirming the stereotype of the silent Finn (Olbertz-Siitonen and Siitonen Reference Olbertz-Siitonen and Siitonen2015). Nevertheless, many respondents showed no intergroup bias at all, and extreme bias was rare. Several traits (e.g., selfish, assertive, straightforward, diligent, reliable) displayed no bias at the aggregate level. At the individual level, two predictors of intergroup bias emerged consistently in our models: ethnolinguistic identity and perceived intergroup threat. Stronger identification as a Swedish-speaking Finn (using language as an identification for one’s social group) was associated with higher bias, confirming predictions from previous research (Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim 2006; Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2008) and social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and William1986). Perceived intergroup threat was also a consistent predictor, suggesting that threat perceptions, possibly linked to concerns over the language climate (Lindell et al. Reference Lindell2023), play a central role in intergroup bias. This corroborates previous findings that intergroup threat seems to strengthen social identification with the ingroup and therefore lead to higher intergroup bias (Renström, Bäck, and Carroll Reference Renström, Bäck and Carroll2021; Riek, Mania, and Gaertner Reference Riek, Mania and Gaertner2006).

We expected that the level of outgroup language proficiency would affect intergroup bias (Karv Reference Karv, Karv and Backström2022), partly because the contact hypothesis would predict that having greater language skills would correlate with more outgroup contact (Laundry and Bourhis Reference Landry and Bourhis1997) and, consequently, a lower level of intergroup bias. However, Finnish language skills did not have any effect on intergroup bias, a finding consistent with previous research on Swedish-speaking Finns (Liebkind and Henning-Lindbolm Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Tandefelt2015; Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom, and Solheim Reference Liebkind, Henning-Lindblom and Solheim2006). Moreover, respondents identifying as unilingual (Swedish-speaking) or bilingual (Swedish- and Finnish-speaking) did not differ in their level of intergroup bias. The null effect of the contact hypotheses may suggest that contact effects may be contingent on low perceived threat. The absence of effect for our measure for intergroup contact, the share of Finnish speakers in the respondent’s municipality, may reflect measurement limitations, as this measure underestimates individual exposure to the outgroup.

From a theoretical perspective, our results indicate that intergroup bias is not confined to low-status minorities but can persist in a high-status minority context and that threat perceptions may override the bias-reducing potential of contact. The stronger bias found for positive traits highlights the role of subtle forms of bias, which may reinforce ingroup cohesion without overt hostility. This suggests that measures of intergroup bias should not focus exclusively on negative traits or overt prejudice. The lack of effect from contact might suggest that contact’s effect is conditional on identity threat levels, also in societies that value equality but still face societal and intergroup divides. Thus, the absence of a contact effect points to the need for more precise measurement of contact, distinguishing between casual contact, close relationships, and institutional contact.

From a societal and policy perspective, our results stress the importance of addressing perceived threat when seeking to reduce intergroup bias in minority–majority relations. Efforts to strengthen intergroup relations, such as strategies reducing prejudices, promoting inclusive language policies, and maintaining the vitality of minority languages, might be more effective than only focusing on increasing contact or language skills. Finally, this study also points to avenues for future research. An interesting follow-up study would be to examine intergroup bias from the majority group’s perspective, which would provide a more complete picture of minority–majority dynamics. Future research could build on these findings and better assess the causal relationships between perceived threat, ethnolinguistic identity, and intergroup bias by using longitudinal or experimental designs. Comparative studies with other high-status minority groups would further clarify whether the dynamics observed here are context-specific or generalizable.

Despite its contributions, this study has certain limitations. The operationalization of intergroup contact as a proxy variable, based on the share of Finnish speakers in the respondent’s municipality, rather than a direct measure of personal contact, may not fully capture the quality or frequency of individual intergroup interactions. The same goes for the operationalization of intergroup threat, which may capture perceived hostility and negative intent more than threats as such. Future studies could more explicitly analyze symbolic and realistic threats to fully understand the impact of various threats on intergroup bias. Our analyses aggregated Swedish speakers with bilinguals, which may obscure some identity dynamics. The absence of Finnish identity markers in our analyses needs to be considered, as this could influence intergroup attitudes among bilingual individuals. Moreover, the lack of comparative data on the level of intergroup bias in other populations (e.g., Finnish-speaking Finns) makes interpreting our results more difficult. Addressing these limitations in future research would strengthen the evidence base for understanding intergroup bias in bilingual societies such as Finland.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2025.10053.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the trait assignment analyses by language group are publicly accessible via the Finnish Social Science Data Archive (https://doi.org/10.60686/t-fsd3848). However, certain variables used in the regression analyses are not included in the archived dataset, as they originate from an integrated dataset combining information from previous survey waves (2019–2022), which is not publicly available. This integrated dataset is available from the author(s) upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the three anonymous reviewers and the editor for their careful reading and helpful suggestions, which substantially improved this article.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Svenska Litteratursällskapet (SLS) under Grant number 6071; the Research Council of Finland under Grant number 350361; and the Research Council of Finland under Grant number 350947.

Competing interests

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

AI declaration

We used ChatGPT to check the language for parts of the manuscript and subsequently reviewed and edited the text as needed.