Introduction

The last few decades have witnessed many examples of male politicians actively engaging in gender equality politics. For example, Mikael Gustafsson became Chairmen of the European Parliament's Committee on Women's Rights and Gender Equality in 2011, Barack Obama was among the many male supporters of the United Nation's HeForShe 1 campaign and the Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau appointed a parity cabinet including at least 50% female ministers and proposed measures for equal pay and longer parental leave. However, despite these positive examples, the role of male politicians in the substantive representation of women has, so far, largely been ignored.

Based on the assumption that political interests are attached to the identity of individual people or specific groups, previous studies have focused on the relationship between identity and parliamentary behaviour and identified female members of parliament (MPs) as the central actors in the substantive representation of women's interests because they share gender‐specific experiences with women in the population (Phillips Reference Phillips1995; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Childs Reference Childs2002).2 Contrary to the well‐known assumption that there is a direct link between descriptive and substantive representation (Phillips Reference Phillips1995), this paper seeks to contribute to a broader understanding of the potential actors in the substantive representation of women and to analyze whether and under what conditions, male MPs become critical actors (Childs & Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009) in the representation of women's interests and preferences.

This question is explored from a rational choice perspective, analyzing whether male MPs’ electoral situation affects their decision to act on behalf of women. On a theoretical level, we draw on different literatures from the field of women and politics and feminist institutionalism. In particular, the concept of a gendered leeway (Bergqvist et al. Reference Bergqvist, Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2018) is applied to explain why and under which conditions, male MPs can gain electoral benefits from engaging in women's substantive representation. The expectation is that in contrast to their female colleagues, male MPs are not expected to be active on women's issues and will not be held accountable if they do not actively promote these issues in parliament. However, if they do act in women's interests, they can gain additional credit because it is not generally perceived as a duty that male politicians should fulfil. In other words, ‘[f]emale politicians are blamed if they do not pursue “women's issues” while male politicians get credit if they do’ (Bergqvist et al. Reference Bergqvist, Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2018: 581). By conceptualizing male MPs as rational, vote‐seeking actors, we therefore hypothesize that men are more likely to speak on behalf of women if their electoral security is low and they are forced to fight for additional votes to be re‐elected. In situations of high electoral uncertainty, engaging in women's substantive representation presents a promising strategy for male MPs, because catering to additional female voters might bring them the votes needed for re‐election to parliament.

The empirical part of the paper analyzes the substantive representation of women by male MPs in the British House of Commons. Given that the British parliament and its electoral system are characterized by high levels of party influence, we rely on an analysis of Early Day Motions (EDMs) to measure the extent to which individual male MPs try to cater to female voters. EDMs are short, non‐binding parliamentary motions that can be introduced by individual MPs without being strongly influenced by the party leadership. Other MPs can sign tabled EDMs to indicate their support for a motion (Kellermann Reference Kellermann2013). Even though EDMs are rarely debated on the floor, they allow MPs to publicize their political statements and to draw attention to specific issues. All the EDMs that were tabled in the parliamentary sessions prior to the General Elections in 2001, 2005, 2010 and 2015 were collected and all the motions which referred to a topic affecting women disproportionally more than men, or that addressed a social condition in which women are disadvantaged in comparison to men, were identified. Based on this coding, an original data set was created containing information on the number of women‐specific EDMs that were either proposed or signed by individual male MPs.

The results of a hurdle regression model corroborate the expectation that male MPs have a gendered leeway regarding women's substantive representation. We find a significant positive effect of electoral vulnerability on male MPs’ general decision to represent women's interests, meaning that male MPs are more likely to either sign or propose a women‐specific EDM, if their re‐election is at risk.

This analysis of male MPs’ role in women's representation, makes two important contributions: Given that very little is known about the role of male MPs in the substantive representation of women, this is one of the first empirical studies to explicitly broaden the understanding of the potential actors and the multiple possibilities for representing women in parliament. Secondly, the finding that men's parliamentary behaviour is affected by their electoral situations, provides an important step in analyzing the conditions influencing male MPs’ willingness to represent women's interests in parliament.

Male MPs and the representation of women's interests

Since previous research has rightly focused on the presence and behaviour of female MPs, relatively little is known about the role of male MPs in women's representation. Relying on Pitkins’ (Reference Pitkin1967) taxonomy of representation and Phillips’ (Reference Phillips1995) politics of presence, earlier studies were mainly interested in the link between the descriptive and substantive representation of women and whether and under which conditions, female MPs represent women's concerns in parliament due to them sharing gender‐specific experiences with women in the population (Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2009).

Nevertheless, there are some pioneering studies concerning the descriptive representation of men and women in parliament, which explicitly focus on men's overrepresentation in parliament (Bjarnegård & Murray Reference Bjarnegård and Murray2018; Murray Reference Murray2014). In the same vein, several scholars have called for a reframing of women's substantive representation and argued for a broader understanding of the potential actors that might act as representatives for women's interests. Based on mixed empirical findings for the question of whether women make a difference when elected to parliament (Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2009), Childs and Krook (Reference Childs and Krook2008; Reference Childs and Krook2009) recommend abandoning the exclusive focus on female MPs’ behaviour and suggest shifting the ‘analytical focus from the macro to the micro level, replacing attempts to discern “what women do” to study “what specific actors do”’ (Childs & Krook Reference Childs and Krook2008: 734) and to identifying potential critical actors who ‘act individually or collectively to bring about women‐friendly policy change’ (Childs & Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009: 127).

Although not explicitly mentioned by Childs and Krook, this revived an idea that had already been suggested by Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967) in her classical conceptualization of representation. Aside from Pitkins’ common conception that political interests are attached to specific group identities (e.g., women's interests), she points out that representatives can also act in favour of interests that are unattached to their own identity (Staehr Harder Reference Staehr Harder2020; Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967, 168–189). This idea of unattached interests, as well as Childs and Krook's (Reference Childs and Krook2009) notion of critical actors, both deviate from the assumption that female legislators are the only actors in the substantive representation of women and underline the need to examine whether and under what institutional and political conditions, men speak on behalf of women in parliament (Palmieri Reference Palmieri2013; Celis & Erzeel Reference Celis and Erzeel2015).

Apart from these theoretical calls for a more inclusive study of the actors in women's substantive representation, there are few empirical studies that explicitly analyze male MPs’ role in the representation of women's interests. On a descriptive level, Celis and Erzeel (Reference Celis and Erzeel2015) analyzed PartiRep survey data from European countries and found that an almost equal number of male and female legislators indicated that they promoted women's interests in parliamentary party group (PPG) meetings. In a consideration of British MPs’ voting behaviour and debate participation, Evans (Reference Evans2012) showed that a small group of male MPs did represent women's concerns in their debate contributions. However, they were in the minority and spoke less if women's interests had already been represented by female MPs. Drawing on assumptions from sociological and feminist institutionalism, a few studies were able to show that male MPs’ legislative behaviour is affected by the presence of an increasing number of women in parliament. Kokkonen and Wängnerud (Reference Kokkonen and Wängnerud2017) conducted a survey of politicians in Swedish municipalities and found that the presence of women has a negative effect on male MPs’ willingness to act for women in the council. Similar results have been found by Höhmann (Reference Höhmann2020b), who shows that while male MPs in the German Bundestag are generally willing to act on behalf of women, they will leave this field to female MPs if the proportion of women in their respective PPG increases. Olofsdotter Stensota (Reference Olofsdotter Stensota2020) shows that male MPs’ personal backgrounds also affect their legislative priorities and their inclination to represent women‐specific issues. In a study of Swedish MPs, she found that men became more likely to express an interest in social policy if they had been on parental leave during their time in office.

However, apart from these initial analyses, little is known about male MPs’ role in the substantive representation of women. Previous studies predominantly used assumptions from sociological and feminist institutionalism to explain male MPs’ behaviour in terms of gendered perceptions about appropriate roles and behaviour. To date, however, no study has analyzed male MPs’ willingness to represent women's issues from a rational‐choice perspective. This is surprising, given that research on women's suffrage and on the adoption of quota laws, has already shown that male elites tend to behave as strategic and rational actors regarding the extension of women's rights (Catalano Weeks Reference Catalano Weeks2018; Teele Reference Teele2018; Valdini Reference Valdini2019).

The present paper considers the behaviour of individual legislators and explicitly studies whether male MPs can be described as re‐election oriented actors, who act on behalf of women if they are electorally vulnerable and obliged to win additional votes from women in their constituencies.

When should men represent women's interests?: A gendered leeway for male MPs

To analyze the role of men in the substantive representation of women, MPs are perceived as rational actors who are mainly incentivized by vote‐seeking, in order to continue their political careers (Müller & Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999). It is therefore expected that MPs adapt their parliamentary activity to their electoral prospects, and that they engage in women's substantive representation to increase their chances of being re‐elected. In order to hypothesize about the conditions under which it is electorally beneficial for male MPs to represent women's issues, we build on a synthesis of previous contributions from the literature on feminist institutionalism and women's substantive representation, and to a great extent draw on the concept of a gendered leeway which was recently introduced by Bergqvist et al. (Reference Bergqvist, Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2018).

In a nutshell, this leeway entails that whereas female MPs are typically expected to act on behalf of women, men are free to choose whether or not they want to represent women's issues in parliament. Previous research on feminist institutionalism (e.g., Krook & Mackay Reference Krook and Mackay2011) has shown that the informal rules and expectations contained in the parliamentary process create a gendered logic of appropriateness that encourages and/or constrains certain types of behaviours by male and female MPs. Since female MPs share gender‐specific experiences with women in the population, it is expected that they will address women‐specific issues more strongly than their male colleagues and that they will push for a gender‐equality agenda in parliament. Due to their linked fate with other women, it is expected that female MPs will have a specific mandate to represent women's interests through their legislative activities (Bergqvist et al. Reference Bergqvist, Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2018).

In contrast, since male MPs are not directly affected by gender‐inequalities, they perceive no comparable mandate to substantively represent women. In accordance with the assumptions of a gendered logic of appropriateness, the representation of women's interests is not generally perceived to be an obligation which male MPs must fulfil. Men enjoy the gendered leeway which gives them ‘the privilege of a larger manoeuvring room that enables them to speak within the gender‐equality discourse without being delegitimized when they prioritize other issues’ (Bergqvist et al. Reference Bergqvist, Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2018: 581).

The crucial point for this paper's theoretical argument is that the gendered leeway leads to a perceived double standard in terms of the perception of duty and praise: ‘Female politicians are blamed if they do not pursue “women's issues” while male politicians get credit if they do’. (Bergqvist et al. Reference Bergqvist, Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2018: 581). In other words, male MPs receive special praise for engaging on women's issues because it is not a duty automatically expected of male politicians. However, female MPs who substantively represent women, are fulfilling a generally accepted expectation and as a result, do not receive particular praise. On the contrary, a female MP's lack of activity on women's issues might even be criticized and the MP blamed by the media, feminist activists or women's organizations. Consequently, men are able to get credit for even fairly minimal levels of engagement on women's issues which are considered normal for women MPs.

Given that men are not criticized by the voters for not representing women's interests, it follows that there is no need for male MPs who are electorally secure to become active in women's substantive representation. They can leave this area to their female colleagues and focus on other issues instead. However, since they can gain additional credit if they support women's issues, it is expected that male MPs will be more likely to speak on behalf of women if their electoral security is low and they are therefore forced to fight for additional votes in order to be re‐elected. If their re‐election to parliament is hanging in the balance and they are faced with a competitive race in the district, male MPs perceive women as an additional source of votes which might ensure their re‐election.

Of course, the gendered leeway does not imply that male MPs are entirely strategic and rational actors, devoid of any intrinsic concerns for women's issues. However, the gendered leeway means that men are in a position that allows them to let strategic concerns play into their decisions about when to engage in women's substantive representation.

Regarding the British case, acting in women's interests might be particularly promising given that women's issues have usually featured prominently in the election campaigns and all major parties have made attempts to target women voters (Campbell & Childs Reference Campbell and Childs2010, Reference Campbell and Childs2015). For example, the 2010 election is often referred to as the Mumsnet election because the parties and media consistently stressed the importance of the women vote.3 This is exemplified by Douglas Alexander, Labour's campaign coordinator, who stated that ‘Labour needs to win back middle‐income female voters with children in marginal seats’ (see, Campbell & Childs Reference Campbell and Childs2010: 761). Thus, we posit the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis: The higher their electoral vulnerability, the more strongly will male MPs represent women's interests in parliament.

If male MPs are indeed incentivized by vote‐seeking and if they represent women's issues to enhance their electoral prospects, it is further expected that men will mainly engage in low‐cost activities that are not very time‐ and labour‐intensive. This enables them to present themselves as acting in the interests of women, while still being able to spend most of their time on issues that are higher on their personal agendas. It is therefore assumed that male MPs are more likely to sign women‐specific EDMs, than to write and introduce their own motions related to a women's issue. Accordingly, electoral vulnerability should primarily affect male MPs’ signing behaviour, making them more likely to support women‐specific EDMs proposed by their colleagues. The effect on the introduction of their own motions, should be less pronounced.

Methods and data

The empirical analysis examines the representation of women's interests in the British House of Commons prior to the 2001, 2005, 2010 and 2015 General Elections.

Due to their central role in the British parliament, political parties constrain the legislative influence of individual MPs. Political parties and their programmatic orientations primarily determine the legislative agenda as well as the enacted policy outputs. Moreover, given that the House of Commons is characterized by strong party discipline, most parliamentary activities (e.g., bill introduction, voting) are controlled by the party leadership, and the opportunities for individual MPs to bring new topics or policies to the parliamentary floor are severely limited. Therefore, in order to reduce the impact of party cohesion, the introduction and signing of EDMs is used to measure how strongly male MPs represented women's interests in parliament.

Using Early Day Motions to measure women's substantive representation

EDMs are formal notices of motions submitted by individual MPs for debate in the House of Commons for which no date has been fixed (House of Commons Information Office 2010). They can be tabled by any MP on any topic and must consist of a single sentence of no more than 250 words. Although, in practice, these motions are rarely debated, other MPs can express their support by signing individual EDMs. EDMs, together with their sponsor and the names of the signing MPs, appear in the printed vote bundle of bills before parliament every day (Kellermann Reference Kellermann2013). The number of EDMs has increased significantly in recent decades, with there regularly being more than 1,000 motions and over 20,000 signatures per session.4

The usefulness of EDMs as a measure of parliamentary behaviour has been questioned. Since they have no formal policy implications and are not actually debated or voted upon on the floor of the House, some MPs refuse to introduce or sign EDMs due to their ineffectiveness and in protest at the administrative costs.

However, there are also several arguments supporting that the importance of EDMs should not be underestimated and that they have several characteristics that make them a suitable indicator for our study.

First, there are many examples showing that the submission of EDMs is much more than simple cheap talk and that these short motions can initiate debates in parliament that can ultimately lead to substantial policy changes. One famous example is MP Christine McCafferty who tabled three widely supported EDMs in 1997 asking the government to classify women's sanitary products as essential to the family budget and to reduce the associated Value Added Tax (VAT) to zero. In response to these motions, the Labour Government reduced the VAT for sanitary products from 15 to 5 per cent in their 2000 budget (Childs & Withey Reference Childs and Withey2006).

Relatedly, Childs (Reference Childs2002) and Childs and Withey (Reference Childs and Withey2004) have shown that EDMs are a viable way for MPs to substantially represent the interests of women. By interviewing several female Labour MPs, Childs (Reference Childs2002) found that EDMs were frequently mentioned as an important tool for raising issues important to women.

Second, EDMs are indicators of individual MPs’ actual behaviour and their efforts to enhance their own electoral prospects. Although they may be used for a variety of different reasons (e.g., send signals to interest groups), they represent one of the few opportunities for MPs to generate publicity in their constituencies, to raise issues that are important to them and to differentiate themselves from the official party agenda. In this way, EDMs serve as a signalling device which individual MPs can use to demonstrate their responsiveness to their constituencies and to cultivate personal reputations in their districts. EDMs go on official record, allowing MPs to say that they have ‘tabled a motion in Parliament’, thus demonstrating that they care about their local constituencies’ needs. Moreover, the parties’ and whips’ influence on the introduction and signing of EDMs is less than for many other parliamentary activities (e.g., voting). According to Kellermann (Reference Kellermann2013: 263), EDMs are excellent ‘indicators of member preferences’ since they ‘are not whipped by the parties’. Of course, the tabling and signing of EDMs is monitored by the party leadership, but party whips usually do not try to influence the behaviour of their MPs in this regard (Kellermann Reference Kellermann2012). Members of the Labour Party are merely required to inform the Chief Whip before tabling an EDM. The other parties do not have any formal restrictions regarding the submission or the signing of EDMs (House of Commons Information Office 2010). Therefore, previous studies have used EDMs to measure MPs’ individual preferences and attitudes (Childs & Withey Reference Childs and Withey2004), to calculate MPs’ positions on an ideological left‐right dimension (Kellermann Reference Kellermann2012), or to measure cohesion within political parties (Bailey & Nason Reference Bailey and Nason2008).

Third, and crucially for the theoretical argument of this paper, previous research has demonstrated that voters are aware of their respective MP's EDM activities and that these activities are also rewarded electorally. Kellermann (Reference Kellermann2013) found that EDMs attract a considerable amount of media attention from national and local newspapers and that the number of EDMs tabled has a positive effect on the media coverage received by individual MPs. Moreover, it is quite common for MPs to publicize sponsored or signed EDMs on their personal webpages and social media channels to highlight their parliamentary efforts.5 Kellermann (Reference Kellermann2013) demonstrated that MPs from competitive constituencies therefore introduced more EDMs than those from less competitive districts, and that higher rates of EDM introduction are associated with larger winning margins in subsequent elections. EDMs’ effectiveness as a political tool for building an electoral connection with local voters has been corroborated in a recent study by David Parker (Reference Parker2019). Using data from the 2015 British Election study, he found that the number of constituency‐related EDMs positively affected the likelihood that the respondent would perceive the MP to be a constituency servant who brings the district's issues to parliament.

Finally, submitting and signing EDMs is a useful indicator for the individual priorities of MPs because it requires the allocation of scarce resources and is by no means a costless activity in terms of time and opportunity costs. MPs must identify the issues they want to promote or support with their motion, write it, and format and submit it appropriately. Additionally, EDMs can incur political costs if MPs support motions on politically or socially controversial issues. For example, Peter Bottomley was the only MP from the Conservative Party who signed an EDM put forth by Labour MP Diane Abbott to better protect abortion services in the United Kingdom and to enforce buffer zones around abortion clinics to prevent violent demonstrations by anti‐abortion activists.6

Given their limited policy implications, EDMs are, of course, only one of many components in a larger electoral campaign (Parker Reference Parker2019). Nevertheless, they provide a useful tool for MPs to gain potential voters’ attention and are a way of influencing their individual election outcomes. In this article, we therefore use the introduction and signing of EDMs as a proxy for the male MPs’ overall electoral strategy and their willingness to address women's issues to cater to additional female voters.

We collected all EDMs proposed during the last parliamentary sessions immediately before the 2001, 2005, 2010 and 2015 General Elections.7 Given that women in Britain are consistently overrepresented in the group of undecided voters who make their voting choice relatively close to the election (Campbell & Childs Reference Campbell and Childs2015: 219), marginal male MPs’ attempts to cater to female voters should become particularly pronounced in the immediate run up to an election. Each EDM was then hand‐coded by the authors to identify whether or not it dealt with a woman specific topic.8 To be as inclusive as possible and to acknowledge that women are a diverse group with heterogeneous life experiences and preferences, all EDMs were coded as women‐specific if they explicitly had women, or some subset of women, ‘as their primary subject matter’ (Reingold Reference Reingold2000: 166–167). This includes all issues ‘where policy consequences are likely to have a more immediate and direct impact on significantly larger numbers of women than of men’ (Carroll Reference Carroll1994: 15). Furthermore, topics are considered as women‐specific if they propose provisions to mitigate or completely eliminate inequalities between men and women. Thus, EDMs that primarily focus on men or masculinities, but with the aim to improve gender equality, are also coded as women‐specific (e.g., regulations regarding paternal leave).

Accordingly, EDMs were categorized as women‐specific, if they referred to a topic that for either biological or social reasons, affects women disproportionally more than men, or if it addresses a social situation in which women are disadvantaged compared to men (Celis Reference Celis2008). Topics that have traditionally been described as female, such as youth policies, or education, were only coded as women‐specific if they explicitly referred to discrimination against women (Höhmann Reference Höhmann2020a). Accordingly, the women‐specific EDMs addressed a wide range of different topics, including domestic and sexual violence against women, discrimination at work (e.g., gender pay gaps), legal protection for working mothers, medical care for women with breast cancer, and legal provisions concerning abortions and prenatal examinations. In addition, concerns about professions that are more frequently pursued by women than men (e.g., midwifery) are defined as women‐specific. This definition of women's interests is very broad, not limited to a specific context and includes feminist as well as more traditional conceptions of women's role in society. On the one hand, women's substantive representation therefore includes advocacy for the expansion of women's opportunities. On the other hand, it also includes the actions of MPs who stress traditional gender roles or asked the government to restrict equal rights for women.9

Below is an example of an EDM that was submitted by a male MP and that we classified as women‐specific:

EDM 756, 2014–15, Means Testing For Female Victims Of Domestic Violence: That this House believes all women suffering domestic violence should have the right to safe accommodation when at risk of harm; notes that employed women are means tested at the point they attempt to access accommodation resulting in some women having to self‐fund their time in refuges; further notes that domestic violence often includes financial abuse that prevents some women from having access to money; believes women's immediate safety should be prioritised above their ability to access private funds at a time of personal crisis and serious risk of physical harm; further believes that the Government's call to end violence against women and girls: strategic vision should recognise the risks posed by means testing employed women; and calls for the means testing for eligibility of public funding to include an assessment of the economic impact of abusive and controlling relationships. (Andrew McDonald, Labour)

Based on this classification, the final dataset includes information on the number of women‐specific EDMs introduced by each individual MP, as well as the number of women‐specific EDMs that an MP has signed. Three different dependent variables were then created for the statistical analysis. For the first dependent variable, the number of women‐specific EDMs that each individual either proposed or signed was counted and this amount was then divided by the total number of EDMs proposed or signed by the MP during a single legislative session. We use the share of women's EDMs because the likelihood of submitting or signing a women‐specific motion also depends on the total number of EDMs that a MP submits or signs. If a legislator is highly active and sponsors a large amount of EDMs, it is also quite likely that one of these motions might refer to a women‐specific topic. Using the share of women's EDMs accounts for these different activity levels.10 To give a more nuanced picture, the second dependent variable only looks at male MPs’ signing behaviour and is expressed as the ratio of the number of women's EDMs signed to the total number of EDMs that the MP signed. The third dependent variable is constructed in the same way for the number of women's EDMs that the MP proposed.

Independent and control variables

For the main explanatory variable of the analysis, a measure of the individual legislators’ electoral vulnerability was needed to indicate whether or not an MP faces a competitive race in the next election. Following previous research, we use the vote margin of victory in the prior election to operationalize electoral vulnerability. Such margins measure the distance between the first two candidates in a district and are calculated as the percentage of the winning candidate's votes minus the closest competitor's percentage of the votes (Blais & Lago Reference Blais and Lago2009). The smaller the distance between the winner and the second‐best candidate, the more uncertain the outcome of the next election and the higher the incentives for the incumbent MP to fight for additional votes to guarantee re‐election. To calculate our measure of electoral vulnerability, the winning vote margin was subtracted from 100, so that high values express high electoral vulnerability. The information on election results and vote margins, is taken from Reference Geese, Janssen, Sanhueza Petrarca, Schacht, Morales, Saalfeld and SobolewskaGeese et al. (forthcoming).

Several control variables are included in the analysis. The first group of variables includes structural characteristics of the electoral districts that might affect the MPs’ electoral prospects, as well as their representational behaviour. In general, it is assumed that districts with more progressive populations offer higher incentives for male MPs to represent women's issues, in order to win additional votes. At the same time, competitive districts might not be randomly distributed among MPs. Parties may strategically assign more gender‐friendly male MPs to marginal districts that are more liberal and progressive. Two different proxies were used to measure the districts’ progressiveness. First, we include the population density (number of inhabitants per hectare) to distinguish between rural and urban districts. Education is used as a second proxy, by adding the proportion of the population with higher education (Level 4 or above, according to the Regulated Qualifications Framework).11 Information on district characteristics was taken from the 2001 and 2011 Census data. Moreover, presenting themselves as being responsive to female voters, might be more important to incumbent male MPs who are running against a female challenger in their electoral district (Murray Reference Murray2008).12 Therefore, we include a control variable indicating whether the major electoral contender in the district (i.e., candidate with the second‐most votes) was a woman. The data on electoral candidates stem from Pippa Norris’ British Parliamentary Constituency Database and the British General Election Constituency Results dataset.13

The second group of control variables includes the MPs’ personal characteristics. A dummy variable was included for government ministers and for the speaker and the deputy speakers of the House, because, according to parliamentary conventions, they are not expected to table or sign EDMs (Childs & Withey Reference Childs and Withey2004). At the same time, these highly visible legislators could have better re‐election chances than backbench MPs. For similar reasons, an additional dummy variable was used to indicate frontbench MPs with a leadership role in their parliamentary party group (parliamentary party leader, whip, spokespersons). The MPs’ age in years was added because older legislators tend to have more conservative attitudes towards gender equality (Kokkonen & Wängnerud Reference Kokkonen and Wängnerud2017). Moreover, we control for potential career effects since the MPs’ parliamentary behaviour could change over time (Bailer et al. Reference Bailer, Breunig, Giger and Wüst2021). Thus, a dummy variable was added for newcomer MPs, who are serving their first term in the House, as well as a dummy variable for MPs in their last term, who are not running again in the next election. Additionally, we control for a membership in the Children, Schools and Families Committee since these MPs should be more likely to represent women's issues, irrespective of their electoral vulnerability.

Besides these personal characteristics, potential party‐related biases were also controlled for. First, all models include the MPs’ party affiliation, to account for ideological differences in the MPs’ affinity to gender equality, as well as for general differences in the different parties’ electoral prospects and that of their candidates. Second, prior research has shown that the increased presence of women in parliament might negatively affect male MPs’ likelihood of representing women's interests (Höhmann Reference Höhmann2020b). The analysis therefore controls for the share of female MPs in the respective male MP's party. Data for the above‐mentioned variables stem from the PATHWAYS project (Reference Morales, Saalfeld and SobolewskaMorales et al. forthcoming).

Although the electoral vulnerability of individual MPs is mainly determined by the previous vote margin in the respective district, MPs might also consider the current political situation on the national level when they assess their personal electoral prospects. In order to take these general political trends into account, we include the national poll results regarding the voting intention for the main parties six month prior to the election in the model.14 Lastly, the postulated effect of electoral vulnerability on male MPs’ parliamentary behaviour could be biased by potential time trends. If feminist values and positive attitudes towards gender equality become more prevalent in the population over time, this could make male MPs more attentive to gender‐specific interests. Therefore, we include a linear time trend via the year of the parliamentary session. Supporting Information Appendix A1 contains descriptive statistics for the variables used in the analysis. Supporting Information Appendix A2 shows the distribution of electoral vulnerability for male MPs in the United Kingdom.

Statistical model: Hurdle regression model

The unit of analysis for the empirical analysis is an individual MP in a single parliamentary session. The overwhelming majority of the MPs did not table any women‐specific EDMs and received a score of 0 on the dependent variable.15 To model this extremely right‐skewed distribution that is bounded on the [0;1] interval, we estimate a hurdle regression model, consisting of two different equations which are estimated as separate processes (Kellermann Reference Kellermann2013).

In the first step, the hurdle‐component models a male MPs’ general decision whether or not to become active in the substantive representation of women. If this hurdle is overcome, the explanatory variable's effect on the strength or intensity of the dependent variable, is estimated in the second step. More specifically, the dependent variable in the first equation is expressed as a dummy variable which receives a value of 1 if an MP tables at least one women‐specific EDM. A logistic regression model is then fitted to determine the effect of electoral vulnerability on a male MP's general decision whether to or not to represent women's issues in parliament. In the second step, a beta regression model estimates the independent variable's influence on the dependent variable's strength or intensity. This equation uses only those observations which have submitted at least one women‐specific EDM and estimates the effect of electoral vulnerability on the proportion of women‐specific EDMs submitted by an individual male MP during the parliamentary session. The beta regression model assumes that the data are distributed according to a beta distribution which is bounded between 0 and 1. It is very flexible and therefore, well suited to describing unimodal as well as bimodal, distributions (Smithson & Verkuilen Reference Smithson and Verkuilen2006).

In addition to the skewed distribution, the statistical model must also take the fact that the dataset contains multiple observations for the same MP (in different parliamentary sessions), which are not independent from each other, into account. Therefore, all models are calculated with robust standard errors that are clustered at the level of individual MPs.

Results

During the parliamentary sessions prior to the 2001, 2005, 2010 and 2015 General Elections, we identified 103 EDMs with a women‐specific concern which, in total, received 5,055 signatures from the MPs in the House of Commons. While female MPs proposed slightly more women's EDMs (52), men were more likely to sign women EDMs than their female counterparts (3,982 signatures came from male MPs).16

The effect of electoral vulnerability on male MPs’ likelihood to engage in women's substantive representation

Three different model‐specifications were calculated to test the hypothesis about how male MPs’ electoral vulnerability affects their likelihood of proposing and signing women's EDMs. As explained above, the main model uses the combined number of women's EDMs proposed and signed, as its dependent variable. The results of the main analysis are reported in Table 1. The second and third models re‐estimate the same model specification for signing and proposing women's EDMs separately (results are reported in Supporting Information Appendix A5). Since this paper is mainly interested in men's behaviour and their decision to represent women in parliament, all three models only include data on male MPs’ behaviour.

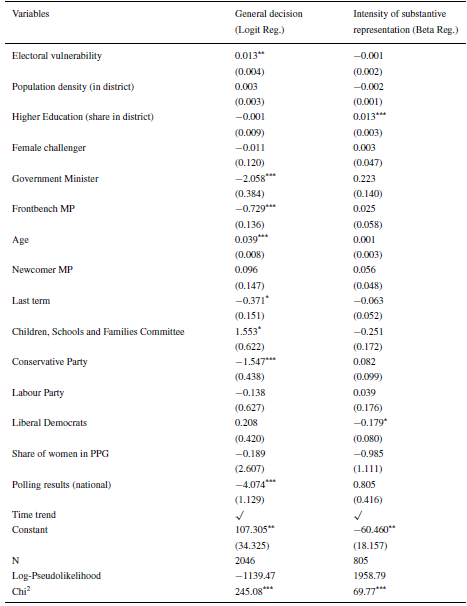

Table 1. The effect of electoral vulnerability on the substantive representation of women by male MPs. Proposing or signing women's EDMs

Notes: Hurdle Regression Model. DV Logit Reg.: Dummy variable coded 1 if share of proposed or signed women's EDMs > 0. DV Beta Reg.: Share of signed or proposed women's EDMs. Coefficients: Log‐Odds. Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered by MP. Reference category for parties: Other. Significance Levels:

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

In Table 1, estimates of the logit regression (effect on the decision whether or not to act on behalf of women) are shown on the left side of the table, and the results from the beta regression (effect on the intensity of substantive representation) are presented on the right. All coefficients are presented as log odds, with robust standard errors clustered at the individual MP level. The beta regression standard errors are conditional on the results of the logit regression to account for the fact that although the two models are estimated in two separate steps, they are dependent on each other. The central explanatory variable is male MPs’ electoral vulnerability (higher values indicate higher competition in the district).17

The results for the logit regression show that electoral vulnerability has a significant positive effect on male MPs’ general decisions to represent women's interests in parliament. These results corroborate the theoretical expectations of a gendered leeway, meaning that male MPs are more likely to be active in women's substantive representation if their re‐election is at risk. Since a substantial interpretation of the log‐odds is not very intuitive, we estimated marginal effects and predicted probabilities to assess the actual effect size of electoral vulnerability on men's parliamentary behaviour.18

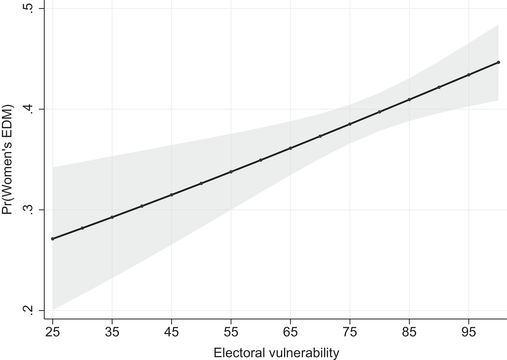

The predictions in Figure 1 show that the predicted probability of male MPs tabling or signing at least one women‐specific EDM is 28.3 per cent at the lowest level of electoral insecurity observed in the dataset. However, if the electoral vulnerability increases, the probability that male MPs will represent women's issues increases steadily. For competitive districts with vote margins of less than 20 percentage points, the predicted probability that male MPs will try to cater to female voters rises to above 40 per cent and continues to increase to roughly 44 per cent for the maximum value of electoral vulnerability. The marginal effects (not shown) indicate that the positive effect is significantly different from zero for all levels of electoral vulnerability.

Figure 1. The effect of electoral vulnerability on the substantive representation of women by male MPs. Predicted probability of proposing or signing women's EDMs (with 95 per cent CIs).

Note: Logit Regression. All other variables enter the model with their empirically observed values.

The results of the beta regression will now be considered. This model only includes those male MPs who have tabled or signed at least one women‐specific EDM, that is, those who have made a general decision to represent women's issues in the parliamentary arena.

The calculation then estimates the effect of electoral vulnerability on the intensity with which male legislators promote the substantial representation of women.

In contrast to the model's first step, the results in Table 1 indicate that the electoral situation's effect on the proportion of women‐specific EDMs is insignificant and therefore indistinguishable from zero. Thus, the parliamentary behaviour of those male MPs who already represent women's interests, is not affected by their electoral situation and they do not intensify their efforts to act in women's interests if their re‐election is in jeopardy.

To sum up, the results of the hurdle regression support the hypothesis of a gendered leeway. If male MPs’ re‐election is almost certain, they are less likely to act in women's interests since they need not fear any negative consequences. However, if their re‐election is uncertain, male MPs perceive women as an additional group of voters to which they could cater in order to enhance their prospects on Election Day.

In order to further assess whether male MPs are primarily extrinsically motivated and only represent women's interests to win additional votes, we separately analyzed the number of signed and proposed EDMs. According to the theoretical assumptions, it was expected that men would mainly engage in low‐cost representational activities; that is, those that are not very time‐ and labour‐intensive. The results (see Supporting Information Appendix A5) confirm this expectation and indicate that the electoral vulnerability effect is mainly driven by male MPs signing women's EDMs. We find no significant effect on either the general decision to propose a women's EDM or on the proportion of women's EDMs tabled. This corroborates our interpretation that male MPs mainly engage in women's representation in order to enhance their electoral prospects. If men decide to represent women in parliament, they engage primarily in low‐cost activities, such as signing a women's EDM. This gives them the opportunity to present themselves as active advocates of their female voters’ interests, however, they are not willing to make a more credible commitment and to invest a significant amount of time and effort in proposing their own women's EDMs.

Further analysis: The effect of electoral vulnerability on female MPs

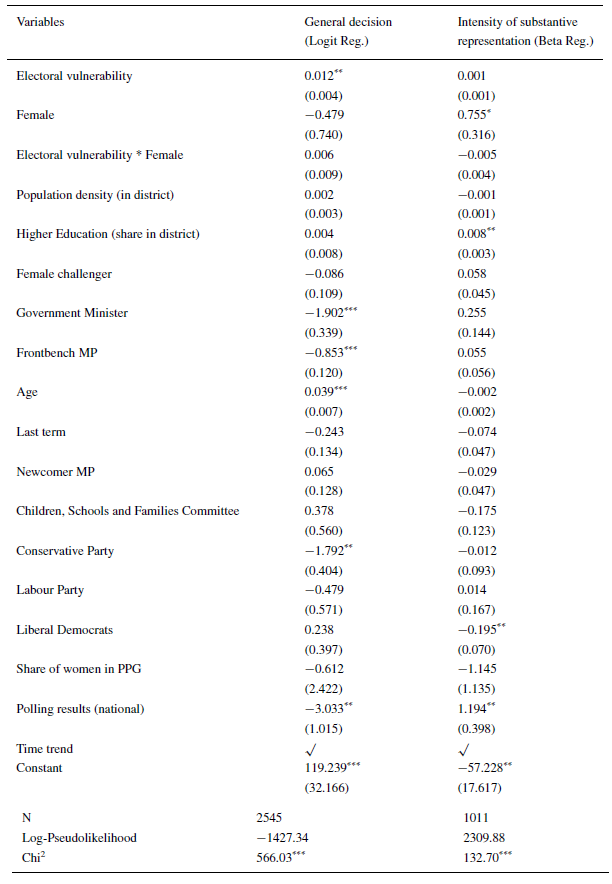

To further examine the evidence for a gendered leeway, we analyze to what extent electoral vulnerability also has an effect on female MPs’ behaviour and whether this differs from that on male MPs. To test for a diverging effect of the electoral situation, the model in Table 2 includes the full sample of male and female MPs and includes an interaction effect of electoral vulnerability and MP's sex (female; coded 1 for female MPs).

Table 2. The effect of electoral vulnerability on the substantive representation of women by male and female MPs. Proposing or signing women's EDMs

Notes: Hurdle Regression Model. DV Logit Reg.: Dummy variable coded 1 if share of proposed or signed women's EDMs > 0. DV Beta Reg.: Share of signed or proposed women's EDMs. Coefficients: Log‐Odds. Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered by MP. Reference category for parties: Other. Significance Levels:

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The results show that the main effect of electoral vulnerability on the general decision to represent women's interests remains positive and significant for male MPs. In line with the expectations of a gendered leeway, the positive effect of female in the beta regression demonstrates that women represent women's interests more vigorously than their male colleagues in situations of low electoral vulnerability. This supports the hypothesis that men are free to choose whether or not they want to represent women's interests and that they use this leeway strategically, to enhance their electoral prospects. Female MPs, on the other hand, engage more strongly in women's substantive representation irrespective of their electoral vulnerability. The interaction effect, however, is statistically insignificant, showing that the influence of electoral vulnerability is not significantly stronger for male MPs.19 This indicates that – besides women's generally higher level of advocacy for women's interests – the behaviour of both male and female MPs is affected by electoral vulnerability. However, it is plausible to assume that men and women might adapt their parliamentary behaviour for different reasons: Whereas men decide to represent women's interests to win additional votes, women rather speak more on behalf of women since they fear to lose votes. As explained above, the theory of a gendered leeway (Bergqvist et al. Reference Bergqvist, Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2018) assumes that female MPs might be blamed by the media and the voters if they do not engage in women's substantive representation. Thus, if female MPs are faced with an uncertain re‐election, they vigorously represent women's interests to avoid this potential criticism which could cost them additional votes on election day.

To further validate the different effect of electoral vulnerability on men and women we also re‐calculated the main models for the sample of female MPs. Contrary to the findings for male MPs, the results in Supporting Information Appendix A6 indicate that electoral vulnerability has a significant effect on the intensity with which female MPs table their own women's EDMs. The effect on signing women‐specific EDMs is insignificant. Together with the findings from the interaction model in Table 2, this corroborates the assumption of the gendered leeway that men are able to get credit for even fairly minimal levels of engagement on women's issues which are considered normal for women MPs. Whereas it is enough for male MPs to decide to generally become active in women's substantive representation and to merely sign at least one women's EDM, female MPs have to heighten their own effort and have to increase the number of self‐submitted women's EDMs to react to increasing levels of electoral vulnerability.20

Conclusion

When do male MPs represent women's issues in parliament? This article tries to develop an understanding for male MPs’ role in the substantive representation of women and presents the first empirical test of the extent to which electoral vulnerability affects the likelihood of male MPs articulating women's interests. The analysis of male MPs’ behaviour in terms of the signing and proposing of women‐specific EDMs in the House of Commons supports the hypothesis of a gendered leeway and shows that men are more likely to engage in women's substantive representation if their re‐election security is low. More generally, this study provides evidence that male MPs do represent women's interests in parliament. However, one of the key drivers of this behaviour is a rational calculation of how they can enhance their Election Day prospects, rather than an intrinsic motivation to stand up for women's rights and gender equality. Moreover, we observed qualitative differences in the representation of women's interests by male and female MPs. Whereas women in the House of Commons are more likely to introduce their own EDMs on a women's issue, men engage instead in low‐cost activities and merely sign women's EDMs, rather than writing their own motions.

To what extent are these results generalizable to other countries and, in particular, different electoral systems? In general, candidate‐centred electoral systems with their inherent necessity to cultivate personal votes should provide strong incentives for male MPs to cater to female voters in order to improve their individual electoral prospects. Thus, similar results should occur under open‐list proportional electoral systems, where intra‐party competition forces MPs to set them apart from other candidates and to create an electoral connection to their voters (Carey & Shugart Reference Carey and Shugart1995). However, the results from the United Kingdom suggest that the effect of electoral vulnerability on the behaviour of male MPs is – to a certain extent – also generalizable to more party‐centred electoral systems (e.g., closed‐list proportional systems). As a Westminster parliamentary system, the House of Commons is usually characterized by high levels of party cohesion and pronounced party leadership control over candidate selection. Carey and Shugart (Reference Carey and Shugart1995) argue that of the single member district systems, the British electoral system offers the least incentive to cultivate a personal vote because voters vote primarily for a party and not for an individual candidate. Nevertheless, male MPs adapt their behaviour to different levels of electoral vulnerability. Thus, comparable effects on male MPs’ proclivity to represent women's interests could also appear under closed‐list proportional systems. Although male MPs have only little influence on their individual electoral outcomes under these party‐centred electoral rules, catering to female voters as a broad social group could boost the vote share of the party as a whole, thereby securing the election of male MPs on marginal list positions (Höhmann Reference Höhmann2020a).

By broadening the understanding of potential actors and their incentives for participating in the representation of women's interests, these findings not only contribute to the literature on women's representation, but also add to a more general discussion about the interactions between descriptive and substantive representation, and how a specific group's identity shapes the role that non‐group members can play in its substantive representation.

The current results are rather pessimistic regarding a potential representation of women's interests by men. The findings show that male MPs are to a large extent extrinsically motivated and mainly speak on behalf of women in order to win elections. In connection to the general debate about non‐group members’ role in substantive representation, future research should analyze whether vulnerable male MPs only attempt to win women's votes, or whether they also try to cater to other underrepresented social groups. For example, non‐minority MPs could start to articulate issues relevant to ethnic minorities, in order to enhance their share of votes from minority constituents.

Analyzing the effect of electoral vulnerability from an intra‐party perspective, with a focus on the candidate selection process, would also be a fruitful avenue for future research. In the light of the more widespread use of measures to promote the recruitment of female candidates in British parties (Campbell & Childs Reference Campbell and Childs2010), male MPs might represent women's issues not only to increase their re‐election chances, but also to send signals to the party selection committee to secure their re‐selection for the upcoming election (Meserve et al. Reference Meserve, Pemstein and Bernhard2020). Male incumbents might be more likely to diversify their issue agenda, including the representation of women, if they are confronted with a promising female contender from within their own party.

An all‐encompassing analysis of the conditions and incentives that make male MPs more likely to represent women's interests, would therefore be an important step toward a better understanding of the multiple ways in which women can be represented in parliament.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the 2019 MPSA conference, the 2019 ECPR General Conference, the 2019 European Conference of Politics and Gender and workshops at the Universities of Konstanz, Cologne, Bamberg, Berlin and Basel. We are grateful for comments and suggestions by all audiences, in particular by Stefanie Bailer, Rosie Campbell, Diana O'Brien, Susan Franceschet, Lucas Geese, Lukas Hohendorf, Kristin Kanthak, Mona Krook, Kelly Dittmar, Ulrich Sieberer, Thomas Saalfeld, Frank Thames and Thomas Zittel.

Open Access Funding provided by Universitat Basel.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interests to disclose.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1. Descriptive Statistics.

Table A4. Percentage of male and female MPs proposing or signing women's EDMs.

Table A5a. The effect of electoral vulnerability on the substantive representation of women by male MPs. Signing women's EDMs, 2001–2015.

Table A5b. The effect of electoral vulnerability on the substantive representation of women by male MPs. Proposing women's EDMs, 2001–2015.

Table A6b. The effect of electoral vulnerability on the substantive representation of women by female MPs. Proposing or signing women's EDMs.

Table A6c. The effect of electoral vulnerability on the substantive representation of women by female MPs. Signing women's EDMs, 2001–2015.

Table A6d. The effect of electoral vulnerability on the substantive representation of women by female MPs. Proposing women's EDMs, 2001–2015.

Table A7a. The effect of electoral vulnerability and a female challenger on the substantive representation of women by male MPs. Proposing or signing women's EDMs, 2001–2015.

Table A7b. The effect of electoral vulnerability and population density (in district) on the substantive representation of women by male MPs. Proposing or signing women's EDMs, 2001–2015.

Table A7c. The effect of electoral vulnerability and education level (in district) on the substantive representation of women by male MPs. Proposing or signing women's EDMs, 2001–2015.

Table A9. The effect of electoral vulnerability on the substantive representation of women by male MPs. Dependent Variable: Absolute number of proposed or signed women's EDMs.

Figure A2. Histogram of Electoral Vulnerability of male MPs, N = 2146.

Figure A3. Histogram of women‐specific EDMs (proposed or signed) of male MPs, N = 2146.

Figure A6a. The interaction effect of electoral vulnerability and MP's sex on the substantive representation of women by male MPs.

Figure A8a. The interaction effect of electoral vulnerability and political parties on the substantive representation of women by male MPs.

Figure A8b. The interaction effect of electoral vulnerability and political parties on the substantive representation of women by male MPs.

Supporting Information