Introduction

While considered to be in the emerging phases for most of the philanthropic sector, participatory grantmaking (PGM)—or the practice of ceding grantmaking power to affected community members and constituencies—is becoming more recognised globally. Growing demands for ‘shifting the power’ have been echoed in various arenas to cede grantmaking power and decentralise decision-making to affected communities (Harden et al., Reference Harden, Bain and Heim2021). Participation seeks to shift the way organisations work with communities and ensures that “nothing is done for them, without them” (Bourns, Reference Bourns2010, p. 1) by enabling communities not only to be part of the change they seek, but also to sustain those changes as well.

The philanthropic sector historically holds power and privilege, with the relationship between grant-maker and grantee being predominantly 'vertical'—the giver possesses greater resources and influence (Fowler & Mati, Reference Fowler and Mati2019; Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson2017). In many cases, funders, despite their distant connection to communities, still dictate funding allocation, even from outside the continent. This has spurred urgent interest in participatory philanthropy and PGM, not least within the emerging realm of 'African Philanthropy'. Here, principles like solidarity, mutuality, horizontal gifting, and 'ubuntu'—which are ingrained in daily life—tend to be more integrated into African giving compared to more traditional forms of Western philanthropy (Fowler & Mati, Reference Fowler and Mati2019; Moyo & Ramsamy, Reference Moyo and Ramsamy2014). While scholars on this do not claim that African gifting or philanthropy has any traits or form of moral superiority that cannot also be found in other geographic settings, and that there still is a proportionate amount of ‘vertical’ institutional giving in the African context, the values seem to parallel many of the values found within PGM. African philanthropy demands an endogenous approach sensitive to the continent's dynamics (Fowler, Reference Fowler2012).

While PGM in the Global North is becoming more studied within the academic space, there is very little focus on how PGM looks in the Global South (Brown, Reference Brown2019). This article aimed primarily to bridge this gap, with the objective of specifically looking at the emergence of PGM within sub-Saharan Africa.

Research Questions, Structure and Scope

As one of the first of its kind, this article aimed to analytically explore the state of PGM in sub-Saharan Africa through the following research questions:

1. What are the key strategies and mechanisms (methods, processes, and structures) of PGM in sub-Saharan African contexts?

2. What are some of the specific contextual challenges and barriers to implementing PGM in the sub-Saharan African region?

3. In what ways do funders working within PGM in sub-Saharan Africa see that power is being moved (or not moved)?

The article aimed to deepen knowledge in these fields by examining the current state of PGM in sub-Saharan Africa through the theoretical lens of power classifications (visible, hidden, and invisible) and relational power perspectives. It caters to both practitioners and academia, providing evidence-based recommendations cognizant of existing forms of power in these grantmaking practices.

Structurally, the article begins by reviewing research on participatory philanthropy and power dynamics in grantmaking. It then presents the methodology and key empirical findings from research interviews with African grantmakers testing various PGM models. The article concludes by discussing the implications for both scholars and practitioners in understanding PGM in sub-Saharan Africa within wider development agendas.

Literature Review

This article primarily contributes to academic research on philanthropy, grantmaking, and international development. The literature review synthesises current knowledge in these areas, highlighting key findings and research gaps related to participation and power in philanthropy. It begins with an overview of the concept of participation, leading to a critical analysis of power and philanthropy. The section concludes with the theoretical and conceptual framework for the study.

Participation in Philanthropy

Participation is hardly a new phenomenon. Participatory development literature began in the 1970s. Paulo Freire (Reference Freire1970), a Brazilian activist, defined the participatory philosophy that shapes numerous disciplines. In the late 2000s, Reason and Bradbury (Reference Reason, Bradbury, Reason and Bradbury2008) laid the foundation for superior analysis using participatory action research. The widespread literature on participation is often cross-disciplinary, with several frameworks developed in health, education, and psychology sectors, among others (Gibson, Reference Gibson2017).

Participation in the philanthropic sector is crucial, given its historical power and privilege (Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson2017). This issue is particularly poignant in the African context, where participation is a core element of African philanthropy. Often described as African gifting, philanthropy in this region embodies principles of ‘sharing’ and mutual support (Fowler & Mati, Reference Fowler and Mati2019). In African communities, giving and assisting one another are integral practices. In this way, philanthropy in this region closely intersects with development, with many philanthropic funders actively intersecting with development initiatives across Africa (Moyo, Reference Moyo2011).

Recently, philanthropic actors have begun employing participatory methods that redistribute decision-making power to external stakeholders, including grantees, community-based organisations, programme beneficiaries, and the public. Some funders are increasingly adopting participatory approaches, especially for marginalised communities such as those living with disabilities, youth, and stigmatised groups like people living with HIV/AIDS and sex workers. Participatory philanthropy encompasses various approaches, all focused on involving these stakeholders. This may include consultation, active participation in decision-making, or direct delegation of decision-making authority (Evans, Reference Evans2015). The overarching goal of participatory philanthropy is to dismantle power dynamics that perpetuate inequitable systems and marginalisation.

Participatory Grantmaking (PGM)

A concrete mechanism to achieve participatory philanthropy is through PGM, which focuses on placing philanthropic resources directly in the hands of individuals who directly face the challenges that the foundation seeks to address (Evans, Reference Evans2015; Gibson, Reference Gibson2017). PGM now goes by many names including collaborative grantmaking, community led grantmaking, community governance, peer review grantmaking, multi-stakeholder grantmaking, grassroots philanthropy, radical philanthropy, and bottom-up grantmaking (Gibson, Reference Gibson2017; Herro & Obeng-Odoom, Reference Herro and Obeng-Odoom2019; Kilmurray, Reference Kilmurray2015; McGinnis, Reference McGinnis2013; Ruesga & Knight, Reference Ruesga and Knight2013). Major philanthropic organisations such as the Ford Foundation have echoed the need to increase participation and activate the voices and leadership of communities. They believe that community participation and self-organising are central to disrupting inequality (Fowler, Reference Fowler2012; Gibson, Reference Gibson2017). The concept of participation infused into philanthropy on the basis that decision-making would become better because of the knowledge and information provided by communities (Hauger, Reference Hauger2022).

Building on the work of Gibson (Reference Gibson2017), Fung (Reference Fung2015), and others, a framework for understanding participation and PGM within institutional philanthropy was developed by Husted, Finchum-Mason and Suárez (2021). The authors synthesise key participation literature and apply it to the context of institutional philanthropy. The framework proposes three key dimensions of participation in philanthropy:

1. Who participates?

2. In what processes do participants participate?

3. To what degree do participants influence decision-making?

Research on PGM is expanding and gaining recognition across various fields. Numerous case studies have delved into PGM from different geographic perspectives (Kilmurray, Reference Kilmurray2015; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Goering, Hopkins, Hyde, Mattocks and Denlinger2021). Large-scale research studies, such as that by Husted et al. (Reference Husted, Finchum-Mason and Suarez2021), have begun to outline the landscape of participatory practices in foundations. Additionally, there are detailed narrative accounts on the history and practice of participatory funding by Wrobel and Massey (Reference Wrobel and Massey2021).

Kilmurray (Reference Kilmurray2015), for instance, conducted a qualitative study of two PGM processes in locations with high degree of political contestation: (a) Northern Ireland and (b) Palestine. She noted several technical aspects of PGM that posed challenges for administration, management, and sustainability. These are relevant to take note of for this study. From observations and interviews of participants in the two regions, Kilmurray (Reference Kilmurray2015) identified several additional requirements for successful PGM. First, community members emphasised that involvement must include not just participation from the most active members of society, but also those that are marginalised and often silent. Second, participatory funding enabled programme officers to understand the lived experiences of community members, which changed initial priorities and assumptions made in top-down approaches.

Researchers and practitioners alike generally agree that there is no one single model for how PGM is structured or organised. Authors such as Evans (Reference Evans2015), however, developed one of the first typologies for participatory philanthropy, which details several ‘models in practice’ that are already institutionalised by grantmakers globally. This includes, among others, representative participation, sometimes referred to as community boards (practitioners, sector experts, or individuals with lived experience making the decisions); rolling collectives (grant recipients becoming grantmakers through a rotating process); closed collectives (funds allocated within a particular geographic location or within a specific group); or open collectives (voting schemes when all interested parties can participate). Research suggests that there are additional models of innovative practice that are quickly developing, including hybrid models of this typology (Hauger, Reference Hauger2022).

Power and Philanthropy

There is increasing focus on power dynamics within grantmaking and philanthropy, and emerging focus on these questions specifically in the African context (Mahomed & Moyo, Reference Mahomed and Moyo2013). As established, philanthropy holds significant power and perceived advantage due to the masses of wealth and resources possessed by grantmakers. This movement of wealth has been useful in addressing development needs in health, education and inequality with notable actions from philanthropic organisations in Africa (Moyo, Reference Moyo2011). Yet, the issue of power is complex, and it is often left unresolved in African contexts even when philanthropy on the continent is more heavily premised on mutuality and interdependence (Moyo & Ramsamy, Reference Moyo and Ramsamy2014).

In Africa, philanthropy still involves power dynamics between funders and local leaders on the ground. Efforts to balance power between the Global North and Global South take place through partnerships, and local actors are increasingly being pulled into decisions on project cycles, from design and implementation to evaluation and learning (Worku, Reference Worku2019) and infusion of African values and identity. This is evident in the post-colonial era (from 1960 to 2000s) described by Fowler and Mati (Reference Fowler and Mati2019), where the inherited legacies of colonial rule affected the mechanisms of decision-making. However, despite these developments in African philanthropy, there is still a power imbalance between those with the funds and those asking for the funds.

To address these power dynamics, philanthropists are adopting a community philanthropy approach as a deliberate strategy to shift power away from themselves and focus instead on dynamics, relationships, and resources at community level. Actors in philanthropy are attempting to localise aid or shift power from within the restrictions of their existing organisational and programme structures (EAPN, 2023).

Conceptual Framework

When looking at the question of power and how it relates to PGM, there are at least two conceptual frameworks that we see as useful: VeneKlasen and Miller’s (Reference VeneKlasen, Miller, VeneKlasen, Miller, Budlender and Clark2002) categorization of forms of power, as well as input related to the relational power perspective.

A frequently employed classification system for examining power in political decision-making and democratic engagement is often referred to as the ‘powercube’ framework, first developed by Lukes (Reference Lukes1974), and further developed by VeneKlasen and Miller (Reference VeneKlasen, Miller, VeneKlasen, Miller, Budlender and Clark2002) and Gaventa (Reference Gaventa1980). It recognises, among other things, three forms of power:

1. Visible power: This encompasses discernible and definable expressions of power within collaboration, such as formal agreements, structures, and authorities.

2. Hidden power: This is wielded by those in positions of authority, who determine key decision-makers and set the agenda. It is otherwise known as relational power, wherein the donor–grantee relationship grants power to the donor over decision-making.

3. Invisible power: The third form is characterised by the psychological and ideological boundaries that define the scope of power.

One critique of this analysis is that it might not fully capture the relational dynamics of power. In this sense, drawing on the relational power perspective highlights the power dynamics in relationships. This perspective shifts the focus from defining power itself to emphasising its practical manifestation (Pantazidou, Reference Pantazidou2012). Power exists within relationships and is shaped by the context in which they occur. It is not just about who has more resources or authority, but how individuals and groups interact, influence each other, and negotiate within specific social, cultural, and political environments. It asserts that power is a dynamic force within relationships, capable of distribution. As a result, power is perceived as a complex and varied phenomenon unfolding in every moment and interaction.

In essence, by examining the various approaches to PGM and the theoretical underpinnings of power in philanthropy, the literature review has offered guidelines and identified knowledge gaps to steer the article. The research objectives related to key strategies of PGM and African challenges of implementation paved the way for the article to explore how funders perceived the shifting of power through PGM mechanisms. Empirical evidence was collected to achieve these objectives.

Methodology

The aim of this study was to understand the concept of PGM within the sub-Saharan African context, and an exploratory design approach was suitably employed. This approach allowed data collection to be in depth, coupling literature review findings with qualitative interviews. The qualitative methodology helped to serve theoretical, methodological, and practical purposes, which allowed an understanding of products of enquiry and the process itself, thereby strengthening the validity of the findings (Bryman et al., Reference Bryman, Becker and Sempik2008).

Respondents

Nineteen semi-structured interviews were held both in person and online from January to early November 2023. To recruit interviewees, respondents were identified primarily through a triad of methodologies: an initial literature review to identify funders working with PGM with African partners, a crowd-sourced list through a PGM community of practice, and purposive snowball sampling. All respondents gave informed consent, and ethical clearances were obtained.

Selection criteria for inclusion in this study were: (a) funds were directed specifically towards groups in sub-Saharan Africa, (b) decisions and strategy about the grants were made fully or partially by Africans themselves, (c) respondents were African or African-based (regardless of where the grantmaker’s registered office was). The rationale was to account for African perspectives on the topic, which represents a research gap. For the sake of scope, the study stayed within the third-sector (and/or philanthropic) space and did not include government-run programmes or those specifically from emergency assistance organisations.

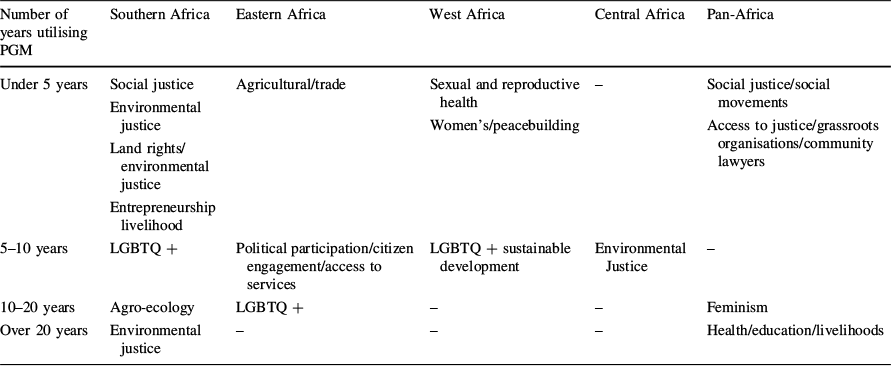

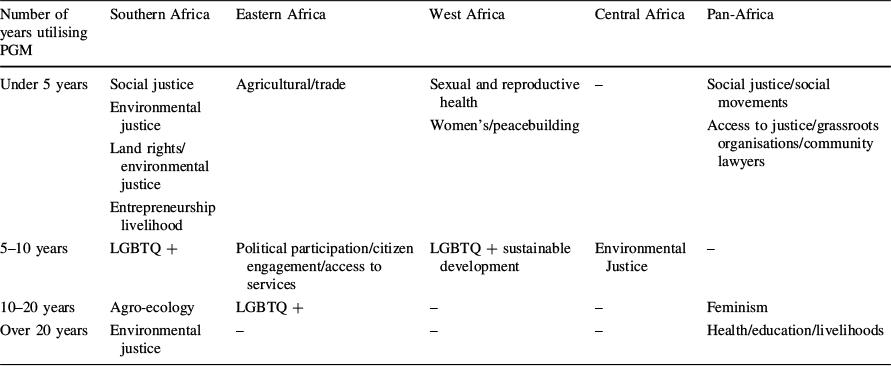

Respondents were primarily staff members in grantmaking entities, many of whom possessed extensive experience in both PGM and conventional grantmaking practices. Among this group, some were actively involved in decisions regarding grant allocation, while others served in a facilitating capacity. The respondents worked within a wide spectrum, including sex workers, environmental justice, social justice, workers’ rights, abortion rights, health, education, livelihood, access to justice, movement building, peacebuilding, agro-ecology, and women’s and girls’ rights. Geographically, the respondents represented diverse regions, with concentrations of PGM-delivered funding directed towards Southern Africa (7), Eastern Africa (3), West Africa (4), Central Africa (1), and Pan-Africa (4). Nearly half were affiliated with PGM processes of grantmaking organisations registered in the Global North, while the rest were affiliated with organisations registered in Africa. A potential limit to the data is that it is not controlled by the size of the grantmaker, but care was taken to ensure a breadth of thematic and geographic examples. Table 1 shows the PGM themes according to region and number of years working with PGM.

Table 1 PGM themes according to region and number of years working with PGM (November 2023)

Number of years utilising PGM |

Southern Africa |

Eastern Africa |

West Africa |

Central Africa |

Pan-Africa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Under 5 years |

Social justice Environmental justice Land rights/environmental justice Entrepreneurship livelihood |

Agricultural/trade |

Sexual and reproductive health Women’s/peacebuilding |

– |

Social justice/social movements Access to justice/grassroots organisations/community lawyers |

5–10 years |

LGBTQ + |

Political participation/citizen engagement/access to services |

LGBTQ + sustainable development |

Environmental Justice |

– |

10–20 years |

Agro-ecology |

LGBTQ + |

– |

– |

Feminism |

Over 20 years |

Environmental justice |

– |

– |

– |

Health/education/livelihoods |

The coding of the research took an inductive approach, where the interview transcript data were initially coded structurally (who, what, where, and how), followed by a values lens (attitudes and beliefs of the participants). Finally, we utilised selective in vivo coding to capture particularly impactful or representative phrases from participants, which contextualise the broader themes of the inductive coding.

Results and Discussion

PGM in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Present and Emerging Practice

The findings of the research show that PGM in sub-Saharan Africa is not necessarily new, with several examples of funders in the region who have based their work in participatory methodology for 10 + years. What appears to be new, however, is the wave of organisations that have begun instigating pilots or initial steps into PGM in the past five years. Around half of the grantmakers included in this study, for example, have been working in PGM for five years or less, with a particular wave of PGM programmes beginning around 2020. Prior to this, respondents inferred that decisions around grants were done either by (a) grantmaking bodies based in the Global North, or (b) more traditional mechanisms that do not directly involve grantees in the decision-making processes. In this sense, many of the respondents acknowledged openly that their responses come from initial reflections on a journey into the new.

A considerable number of participants found it challenging to label their own efforts as PGM specifically. This difficulty arose due to either the novelty of the term, the complexities of its conceptual dimensions, or utilisation of other modes of description. Several respondents chose, rather, to describe grantmaking as solidarity-driven, decentralised, trust-based, or community/activist led/owned funding. Some articulated a reservation to grantmaking in general. Several respondents spoke of their origins as being embedded in marginalised communities—the grantmaking developed secondarily:

We didn't want to do grantmaking, because we wanted to focus on the relationships of solidarity that are not polluted by the dynamics that come with funding. But the reality is, for people to do social justice work effectively at the local level they need money, so you can't run away from the fact that money is affected. So, we did become a funder of sorts. (R1, Staff, Southern Africa, working with social justice)

Drivers for PGM in Sub-Saharan Africa

The drivers to use participatory methodology were often organic and internal—a natural evolution or even the origin of their work. Others, however, felt their PGM efforts were a direct response to external challenges within the current system. First, there were few safe mechanisms to get funding to marginalised and criminalised groups (e.g. sex workers, environmental activists, unregistered groups); second, funds from traditional donors kept going to the same groups or NGOs (e.g. ‘the usual suspects’ found in urban areas and/or non-grassroots organisations). Third, there was a need for a concrete set of eyes to see nuances and needs in a geographical context (e.g. peacebuilding, land issues, victims’ rights); and fourth, it was a direct alternative to traditional North/South funding practice:

But you know, we really feel if you want to be responsive to the field, and to resource the movements, then we can't be making the decisions in the Global North or in urban areas; those who don’t have a lot of interaction with grassroots groups. (R7, Staff, Pan-African, working on access to justice issues)

Format and Structure of Grantmaking Bodies

As noted in the literature review, research on PGM globally shows there is no single model for its structure or organisation. The same applies to PGM in the sub-Saharan African context. The variety of formats and structures appears to reflect contextual and organisational needs, similar to trends in other parts of the world (Gibson, Reference Gibson2017). General trends in the mechanisms and forms of PGM in sub-Saharan Africa are as follows:

Use of Grantmaking Panels or “Community Boards”

The most common grantmaking format was the convening of some form of “community board” (McGinnis, Reference McGinnis2012, p. 8), referred to in this study as an activist panel, core group, grants selection committee, peer grant committee, advisory group, or support group. These decision-making bodies were often composed of community members from the constituencies the grants aimed to reach (e.g. activists in environmental movements, young feminists, sex workers). When the grantmaker was based in the Global North, final approval or due diligence procedures were sometimes carried out there for legal reasons. However, in most cases, the community boards had full decision-making power over the grants.

Use of “Closed Collective” Model

The next most common model was what many researchers and practitioners describe as a “closed collective” model (Hauger, Reference Hauger2022, p. 7), where a specific group has access to a fund and decide among themselves how the funding would be used. The major rationale for those using this model was often related to an effort to build collective agency within a group (e.g. small-scale farmers) to decide on their own futures. Another rationale related to the extreme sensitivities or safety of specific marginalised or penalised groups (e.g. human rights defenders, environmental defenders, sex workers). There were often very concrete criteria and routines established of how one becomes part of this closed group.

Use of Hybrid Models

In some settings, notably among grantmakers experienced with PGM, hybrid models involved staff, decision-making groups, local communities, and even previous grantees. For instance, one grantmaker invited top applicants to score and discuss applications from their peers before making a final decision. Another used a rotating system of peer reviewers from affected communities for each funding cycle.

A commonality in nearly all cases was the role of affected communities in decision-making from beginning to end. Funders emphasised the importance of integrating community members’ experiences and feedback into grant programmes' structures or calls (e.g. landscape studies, movement forums, consultation processes, co-creation workshops). With few exceptions, respondents noted ongoing changes and learning driven by community feedback.

Distinguishing factors between grantmaking groups included: the role of the back-donor (e.g. active voting versus passive observation); and the extent of staff involvement (e.g. active voting versus secretarial or convening roles). Strategic and political choices about funding (e.g. open application calls versus targeted processes, activity-based versus unrestricted funding, large versus small grants) and transparency about decision-makers (e.g. open versus anonymous for safety reasons) also varied.

PGM as an Integrated Part of the Larger Development Funding Sector

One of the clearest features of PGM in sub-Saharan Africa is that most of the respondents saw their efforts in the context of a broad development space, rather than solely within the silo of philanthropy or grantmaking. Their efforts were seen within the ecosystem of larger international development funding. This was consistent with findings of other researchers who have seen similar trends within the African philanthropic space (Moyo, Reference Moyo2011; Moyo & Ramsamy, Reference Moyo and Ramsamy2014).

Concretely, this was expressed in several ways: dynamics between large international NGOs in Africa versus community-based solutions, references to bilateral government agreements, and the changing ‘localization’ agenda of traditional INGOs. Additionally, references to the ‘development space’, emergency response funding, or humanitarian funding, and repeated critiques of traditional development practices (particularly where funding is channelled from North donors to African intermediary grantmakers).

PGM and Shifting Power

Visible Power: Observable Decision-Making

When discussing issues of power in PGM, respondents most frequently expressed the impact of their work as affecting what scholars like VeneKlasen and Miller (Reference VeneKlasen, Miller, VeneKlasen, Miller, Budlender and Clark2002) categorised as changes to visible power (formal rules, structures, authorities, institutions, and decision-making procedures). This involved changes to who and how decisions around grants are made (the process itself); specifically, moving decisions in sub-Saharan Africa closer to those with lived reality who want a say in their future, rather than being made in a boardroom by those unfamiliar with local contexts.

Changes in visible power also emerged in respondents’ views that PGM has shifted the types of groups or initiatives receiving funding. Most described how their PGM efforts allowed them to reach groups that usually do not receive funding. This could be understood as concrete identity-based groups (e.g. trans groups, indigenous widows, pygmy groups, victims of specific conflicts or political situations) or a wider categorical perspective (e.g. unregistered groups, informal groups, social movements, young people). For many, this was the key success factor of their efforts, as illustrated by one respondent.

You are allowing money to go to where money would normally not go. And you have to define your systems of bureaucracies and governance in new ways to recognize that it is not all boardroom and corporate. It has to operate differently. That's been really important, and it has been phenomenal to be able to grant where other grantmaking organisations won’t grant. (R12, Advisor/Staff, Southern Africa, working on environmental issues)

Changes to visible power could also be seen in the broader context of traditional North–South funding. As noted above, most respondents described their work in the context of the international development system—where the Global North generally made decisions around funding priorities. Respondents saw the shift of decision-making around funds to the South as a form of power moving away from a North-dominated funding system.

A few respondents spoke specifically about success as part of changing a larger grantmaking sector. Namely, that their efforts with PGM might serve as a catalyst for macro changes in power dynamics within the sector:

We unexpectedly experienced opportunities for advocacy [toward other grantmakers] quite early on. It's something we imagined doing in five- or ten-years’ time. This has been a pleasant surprise, in terms of playing an advocacy role [on changing grantmaking processes] for others. There seems to be quite a lot of appetite for that right now. (R3, Staff, Southern Africa, working on environmental issues)

Less frequently, respondents raised the issue of how the impact of their work related to changes in policy in the countries where the groups operated. However, given the temporal element of social change and the scope of the research, only a few respondents spoke of specific changes at the recipient level.

There were also challenging aspects of moving visible power noted by respondents. Some highlighted that new power dynamics emerged when those involved in PGM became and were perceived as decision-making authorities within their own communities.

Hidden Power: Setting the Political Agenda

Another form of power is often described as hidden power, or an influence over which agendas are on the table, including barriers to participation. This can manifest in various aspects of the power cube framework, including exclusion through context, strategy, and action; monitoring and evaluation; and facilitation and learning (Pantazidou, Reference Pantazidou2012).

Respondents mostly alluded to moving hidden power, suggesting that PGM contributed to breaking down barriers in influencing one’s own future, especially when no grantmaking mechanisms of its kind existed previously. It was also seen as a way of viewing things not previously seen by traditional grantmaking practices. In this sense, the topic of agency was often discussed by respondents—a feeling of control over their futures—as illustrated here:

I think we’ve been able to see communities become empowered because empowerment on how much money you receive is how much you’ve been trusted to create your own change and define it for yourselves. (R13, Staff, East Africa, working with sexual minorities)

Conversely, hidden power remained part of the dynamic when examining the process itself. Some respondents discussed the challenge of devaluing the concerns and representation of less powerful groups during the grantmaking process. For example, several grantmakers spoke of moving funding away from well-educated, urban groups. Another mentioned the challenge of elites within society, or those with more visible power, remaining part of the PGM process, even if decisions were made more locally than before.

Other cited hidden power dynamics included unequal power between educated and non-traditionally educated people in groups, and between group leaders and grassroots constituencies. Additionally, practical challenges included not being heard above bolder individuals and language barriers.

Most found various practical and normative mechanisms to alleviate or balance these hidden powers, but power dynamics persisted.

Invisible Power, Shaping Meaning and What is Acceptable

Respondents regularly alluded to invisible power—the internalisation of language, values, or norms shaping people’s awareness and understanding of policies and rights. Several groups noted that it took a large amount of effort for grant decision-making groups to accept they were in a decision-making role, especially when accustomed to more traditional grantmaking power dynamics:

In the first year it has been quite hard, because this was so new for many of the panel members—and people didn’t believe that they actually had the power to make decisions. This was not something they had experienced before. Can this be real? The committee now understands this is real, and it is different from the traditional way of doing things. (R5, Staff, Western Africa, working on LGBTQI+ rights)

Invisible power can also be inferred in discussions on decolonizing the grantmaking space, particularly in broader debates about what funding should look like and the norms, prejudices, or ideologies that remain dominant:

I think if you look at any fund supporting groups in the Global South, if you don’t have the community doing the work of supporting their own movements, then yeah, it becomes an agenda-led issue. It becomes an issue not led by the people facing the problem or facing the contextual shocks that movements are facing. When the groups become front-runners around their specific issues that they are facing, it becomes less interfered by Western notions or ideas of what funding should look like. It is decolonising our own work. (R11B, Staff, Eastern Africa, working with citizen engagement and political participation)

This aligns with Pantazidou’s (Reference Pantazidou2012) discussions, highlighting that this subtle form of invisible power is often linked to “a sense of fear or a perceived lack of control in responding to or influencing it” (p. 12).

PGM and Relational power

Another important theoretical perspective observed in the data related to relational or hidden power is that power is complex and cannot be reduced to something that some people possess, while others do not (Pantazidou, Reference Pantazidou2012). There was often a sentiment that these connections represented new values contributing to larger movement building across silos. Emphasis was also placed on shared learning and the ability of groups to find new solutions to difficult problems beyond their own contexts. In this sense, the process was successful and added social value.

The willingness to work together is an important indicator. We can all be very egoistic creatures. When a group of people decide to work together for a common interest, beyond personal interests, and we manage to support that collaboration and that shared responsibility to share the success and failures of the shared innovation within a movement—this is a huge success. (R14, Staff, Southern Africa, working on land issues)

This became even more apparent with funders working outside a single geographical setting (e.g. regionally or in a Pan-African context). One of the process's biggest successes was building greater solidarity and movements among those involved in the PGM process, which is seen parallel to other research on African philanthropy (Moyo & Ramsamy, Reference Moyo and Ramsamy2014):

You see how community members who are part of the decision-making have now started supporting each other, and you see their desire to work with others outside of their own region. This to me is a very positive sign of why it’s important for them to make decisions themselves about funding. (R4, Staff, Western Africa, working on issues of sexual and reproductive health)

In this sense, groups spoke of a new form of informal power that was being built as a result and by-product of the PGM process itself.

North/South Power Dynamics Still Present

While all respondents viewed PGM as a step toward shifting power, many noted that it was not a quick fix, particularly in the context of broader North/South funding and development practices.

Concerns were raised about the power dynamics involved in setting the funding agenda in Africa when the funds originate from the Global North. These concerns were sometimes framed in terms of visible and invisible power, especially when formal decisions are made in the Global North (e.g. legal structures, funding priorities, political views). One respondent gave this example:

There are financial aspects of power relations, and there are political aspects as well. Like who defines the themes or the topics (or interventions) that should be funded. Often you notice that a fund is created (by actors in the North), the theme has been selected, the specific activities have already been selected, and organisation and target groups from the South are solely receptors for decisions that have already been taken. So, I think balanced power relations should also involve opening space for participatory intervention in the definition of what are the issues, the themes, the priorities, and the places that should be funded. (R14, Staff, Southern Africa, working on land issues)

Another form of invisible power was the perception that back-donors still do not fully understand or acknowledge the benefits of their contributions. Several respondents expressed concern that attempting to implement approaches different from or unexpected by Northern back-donors could jeopardise their ability to secure funding. Additionally, some discussed the challenge of adapting or changing their funding mechanisms (even with PGM) to align with back-donor priorities, indicating a vulnerability in relying on external resources—and the remaining power of who ultimately steers the resources.

Some also highlighted a more subtle form of invisible power in the context of North grantmakers hosting PGM processes and the need to be aware of it. Simply transitioning to PGM does not automatically resolve imbalanced power relations. For example, one respondent illustrated this point:

So you see, the power thing is, it’s still there. The funder is still hosting the process. It may not be loud, but the truth is that power is still there. We need to be conscious of that and alert to that, as the power dynamics still follow. I guess it’s about how you take steps back from that. (R18, Staff, Eastern Africa, working on agricultural issues)

Finally, a few respondents still sensed that grantmakers in the Global North might not fully trust their Southern counterparts due to social constructs or worldviews. It was difficult to interpret, however, whether this was related to broader, traditional development practices, or if it was more applicable to grantmakers that were supporting or initiating PGM processes in particular.

PGM as Just One Part of the Bigger Picture

While all respondents were positive about their work contributing to social change, there was consensus that PGM alone cannot fix everything—it is one of many strategies needed for social change. In grantmaking practices, PGM sometimes constituted only a component of broader funding initiatives. Additional mechanisms were often in place to address various programmes or specific challenges, such as inter-movement conflicts, sensitive political issues, quick response funding, or long-term funding.

Points that arose in the research included funding scarcity (the lack of funds despite growing needs); external political and structural challenges (e.g. the need for legal support or the shrinking space for civil society); the need for political advocacy (e.g. public support for causes or policy); and the isolation of grantees and the need to connect them. For grantmakers working with vulnerable communities, psychosocial support was necessary due to the traumas being addressed. Capacity building (e.g. digital skills, training in organizing, political education, technical support) was frequently mentioned, especially by those supporting grassroots groups or small CBOs. Some of this could also be understood as necessary capacity building for the grantmaking process itself, but it also implied broader needs beyond funding mechanisms.

Conclusion

The article sought to analytically explore PGM in sub-Saharan Africa. To do this, it looked at three specific questions: (1) What are the key strategies and mechanisms of PGM in the region? (2) What are some of the specific contextual challenges and barriers to implementing PGM in the region? (3) In what ways do funders working within PGM in the region see that power is being moved (or not moved)?

The main deductions are herein outlined, implications for both researchers and practitioners alike discussed, limitations summarised, and suggestions made for future research.

Summary of Findings

In terms of form, PGM in sub-Saharan Africa was most often structured as representative participation or community boards (made up of members from the communities the grants are intended to support, such as activists, young feminists, and marginalised groups like sex workers) that made decisions about grants with an effort to move decision-making power closer to the communities that receive grants. While the data did not present any immediate correlations between the form of PGM and what forms of power were moved (a point for potential future research), in every case there was a focus on meeting contextual needs and a more inclusive decision-making process to better serve the communities the grants intended to reach.

A key aim of this research was to explore PGM’s contribution to shifting power. Three main conclusions from the data are worth noting: First, the most common change in power related to PGM in sub-Saharan Africa involves shifts in visible aspects of power, such as formal rules, structures, authorities, institutions, and decision-making procedures. This included visible changes in who makes decisions and the types of groups or initiatives that receive funding. This still faced limitations, particularly regarding less traditionally visible power (e.g. education level, language diversity, rural or urban background) that may not be moving as quickly. This finding aligns with previous research on PGM in highly contested societies, which suggested involvement should extend beyond the most active members of society to also include those not traditionally included in participation. Second, PGM appeared to have contributed in influencing which agendas are prioritised by donors (hidden power). It also appeared to have contributed to shifting internalised beliefs (invisible power) of what can be possible in terms of decision-making agency. However, PGM continued to struggle with resource scarcity, which often contributed to reliance on external funding constrained by the priorities of back-donors (often from the Global North).

Third, the data found power will always be present in some form, especially when understood as a dynamic force within relationships, capable of distribution. Respondents highlighted new power dynamics (internally and externally) that emerged when those involved in PGM became and were perceived as decision-making authorities within their communities. For most respondents, efforts were actively being made to mitigate these challenges.

While our research indicates that PGM has contributed to shifting power in grantmaking, the data also show that PGM in sub-Saharan Africa is not a quick fix. It is one of several strategies grantmakers can use to address social issues, alongside political advocacy, capacity building, tackling funding scarcity, and meeting the psychosocial needs of vulnerable communities. PGM is an important component, but not a standalone solution, in the broader pursuit of social justice and development. This is corroborated by another key finding: PGM in the region interacts closely with the larger international development funding ecosystems rather than existing solely within the philanthropy sector. Similarly, PGM maintains many values of ‘African philanthropy’—such as mutuality and solidarity. Yet, the study found these anchors of solidarity have limits. Continued efforts must be made within PGM to enable the participation of all society members and not exclude any community from development.

A note of caution for the conclusion: While the research does indicate shifts in power, the sample of this project mostly covered participants who had some degree of relative power (e.g. staff in PGM processes with access to decision-making around funds). The study did not look specifically at the end-user of the grantmaking process, who could experience power dynamics through a different lens. Additionally, the research did not adopt a temporal approach, limiting its ability to observe changes in power dynamics over time. Lastly, with closely related fields (e.g. trust-based or community-based philanthropy), this study contributes to the evolving discourse on PGM rather than offering a definitive or exhaustive response.

Implications for Researchers and Practitioners

For practitioners and researchers, a key implication is that PGM in sub-Saharan Africa cannot be limited to the realm of philanthropy. The lessons from PGM, particularly regarding shifting power in a traditionally North-dominated development space, should be incorporated into broader development aid discussions. This argument is supported by findings that show such integration is already part of the lived experience of funders working with PGM in sub-Saharan Africa. While philanthropy and development aid are not the same, efforts must be made to share and apply PGM insights beyond a single sector, particularly to challenge traditional top-down decision-making processes. Formal and informal connections between these two areas could be established in various ways: Channelling of traditional aid funding through already existing participatory grantmaking mechanisms, PGM pilot programmes within the decision-making structures traditional developmental aid grants, sharing of research and best-practice between the two fields, rethinking about “effect” (MEL) of long-term developmental aid to also include analysis on shifting power in the process, and more. The research showed that Global North parties often still have some sort of legal or financial power to decide the acceptable models of PGM in Africa (politically, thematically, legally, where funding is directed)—and this form of hidden power in both the developmental aid and philanthropic space cannot be ignored.

Finally, and as mentioned in the discussion above, power will always be a present dynamic in a grantmaking process. Even in PGM processes based on trust, solidarity, and mutuality, continuous efforts were needed to confront visible, hidden, and invisible hidden power as it emerged in new forms. PGM in Sub-Saharan Africa is not immune to power dynamics (both internally and externally). Practitioners and researchers who are working with PGM must continually and repeatedly build and re-analyse solutions, in order to not reproduce some of the uneven power dynamics of grantmaking that it aimed to democratise.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank and acknowledge the University of the Witwatersrand Female Academic Leaders Fellowship (FALF) for the research grant that assisted with some of the research expenses under Grant Number 001.410.4321101MOGO023

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of the Witwatersrand. This study was funded by Wits University Female Academic Leaders Fellowship (FALF) (Grant Number: 001.410.4321101MOGO023).

Conflict of interest

KSM has received a research grant from the University of the Witwatersrand to assist with some of the research expenses. TDH is employed by Karibu Foundation, a grantmaking organisation which partook in some of the interviews. Interviews with Karibu were thus held by KSM. One of the authors of this article is a full-time employee of one of the respondins mitigated by the co-author having responsibility for the intervg organisations in the research. This potential conflict of interest, as well as potential bias in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, waiew and processing of the data for this responding organisation.