Introduction

The Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA) is a research initiative established in 2014 and funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) and partners (Chertkow et al., Reference Chertkow, Borrie, Whitehead, Black, Feldman, Gauthier, Hogan, Masellis, McGilton, Rockwood, Tierney, Andrew, Hsiung, Camicioli, Smith, Fogarty, Lindsay, Best, Evans and Rylett2019). It is aimed at understanding the mechanisms of neurodegenerative illness, advancing methods for prevention and treatment, and improving the quality of life of those living with dementia. Established in 2014, the consortium consists of investigators whose research focuses on issues ranging from fundamental neuropathological processes to issues of quality of life. It is now in its third five-year phase (2024–2029) and will be a resource for Canadian researchers and beyond.

A major platform of the CCNA is the Comprehensive Assessment of Neurodegeneration and Dementia (COMPASS-ND) study, which is an observational study currently consisting of more than 1100 participants at risk of developing a neurodegenerative disease or who are living with a neurodegenerative disease. Recruitment is ongoing. The COMPASS-ND participant cohort includes older adults who are cognitively unimpaired (CU), or who have subjective cognitive decline (SCD), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), vascular MCI, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), mixed dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and those in the Parkinson’s disease/Lewy body spectrum. This is a unique pan-Canadian cohort of participants who are well ascertained with respect to demographic, psychosocial, premorbid history, clinical status, clinical physical examination, cognition, sensory and motor function, neuroimaging, biomarkers and biological indices (including blood, urine, saliva, buccal cells, and fecal material), and genetic profile (Chertkow et al., Reference Chertkow, Borrie, Whitehead, Black, Feldman, Gauthier, Hogan, Masellis, McGilton, Rockwood, Tierney, Andrew, Hsiung, Camicioli, Smith, Fogarty, Lindsay, Best, Evans and Rylett2019). The primary goal was to establish research cohorts of deeply phenotyped participants with, or at risk of, dementia to provide open-access data for CCNA research teams (Phase I and II) and dementia researchers in Canada and internationally (Phase III). By design, inclusion criteria are broad, and exclusion criteria are minimized in order to create an ecologically valid cohort of participants who typically present at clinic. The general methods of COMPASS-ND are described by Chertkow and colleagues (Chertkow et al., Reference Chertkow, Borrie, Whitehead, Black, Feldman, Gauthier, Hogan, Masellis, McGilton, Rockwood, Tierney, Andrew, Hsiung, Camicioli, Smith, Fogarty, Lindsay, Best, Evans and Rylett2019; Chertkow et al., Reference Chertkow, Phillips, Rockwood, Anderson, Andrew, Bartha, Beaudoin, Bélanger, Bellec, Belleville, Bergman, Best, Bethell, Bherer, Black, Borrie, Camicioli, Carrier, Cashman and Wittich2024).

Neuropsychological assessment is a crucial component in the diagnosis of dementia and the specification of its various aetiological subtypes (Weintraub et al., Reference Weintraub, Carrillo, Tomaszewski, Goldberg, Hendrix, Jaeger, Knopman, Langbaum, Park, Ropacki, Sikkes, Welsh-bohmer, Bain, Brashear, Budur, Graf, Martenyi, Segardahl and Randolph2018). The assessment of cognitive function consists of two phases in COMPASS-ND. First, participants complete a cognitive screening test battery at an initial visit to determine study eligibility. Measures of general cognitive function, memory, cognitive complaints, and activities of daily living are used to determine inclusion/exclusion as well as the initial clinical research diagnoses of participants. Second, participants are administered a more comprehensive neuropsychological research battery consisting of both clinical and experimental cognitive measures assessing a broad range of cognitive functions, namely verbal and non-verbal learning and memory, executive function, attention/concentration, language, processing speed, and perceptual abilities. This is referred to as the neuropsychological research battery, and importantly, it is independent from the cognitive screening described earlier, which assigns study group diagnoses. Data from all cognitive measures plus the background clinical and physical measurements will be used to clinically characterize the groups in more detail (e.g., to identify dementia subtypes and other clinical phenotypes) and to provide research data.

In advance of the release of the full COMPASS-ND baseline data set, the purpose of this research note is to provide a standard reference for the neurocognitive research battery to the research community who will use the data in the future. This research note describes the rationale for and the goals of the battery, the process of its development (including parallel versions in both English and French), the procedure for the test selections, the current content of the battery, a description of the tests, and the derived test scores. The procedures for research staff training, data monitoring, and data quality control using the Longitudinal Online Research and Imaging System (LORIS; Mohaddes et al., Reference Mohaddes, Das, Abou-Haidar, Safi-Harab, Blader, Callegaro, Henri-Bellemare, Tunteng, Evans, Campbell, Lo, Morin, Whitehead, Chertkow and Evans2018) are also described. The alignment of COMPASS-ND with other neurodegeneration research initiatives in Canada and internationally is briefly described. A full report of the neuropsychological data on the entire cohort will be forthcoming.

Methods

Participants

This study received local approval from the participating centre(s)’ Research Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board. COMPASS-ND participants were enrolled from 32 centres (i.e., memory clinics affiliated with the Consortium of Canadian Centres for Clinical Cognitive Research (C5R)), select Canadian stroke, movement disorders, or behavioural neurology clinics, as well as academic and private research groups.

General inclusion and exclusion criteria are reported in Chertkow et al. (Reference Chertkow, Borrie, Whitehead, Black, Feldman, Gauthier, Hogan, Masellis, McGilton, Rockwood, Tierney, Andrew, Hsiung, Camicioli, Smith, Fogarty, Lindsay, Best, Evans and Rylett2019). Briefly, participants meet the following criteria to be eligible for enrolment into the study:

-

• Age between 50 and 90 years;

-

• Sufficient proficiency in English or French to undergo assessment. This is operationally defined as good proficiency on the Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q; Marian et al., Reference Marian, Blumenfeld and Kaushanskaya2007), a self-assessment measure of linguistic ability for both speaking and understanding of English or French;

-

• Geographic accessibility to the study site; and

-

• Having a study partner who interacts regularly with the participant, knows them well enough to answer questions about their abilities and functioning, and who can participate as required in the protocol.

General exclusion criteria are:

-

• The presence of another significant known chronic brain condition (e.g., multiple sclerosis, malignant brain tumour, etc.) or current unstable psychiatric illness or untreated depression/mania;

-

• Ongoing alcohol or drug abuse, which might interfere with the participant’s ability to comply with the study procedures;

-

• History of a symptomatic stroke within the previous year;

-

• A Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score < 13; and

-

• Inability to undergo a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

Screening battery and criteria

Participants are given an initial working research diagnosis based on the Cognitive Screening Test Battery and enrolled into participant groups according to criteria described in a previous study (Chertkow et al., Reference Chertkow, Borrie, Whitehead, Black, Feldman, Gauthier, Hogan, Masellis, McGilton, Rockwood, Tierney, Andrew, Hsiung, Camicioli, Smith, Fogarty, Lindsay, Best, Evans and Rylett2019). This research note highlights the criteria specifically for those classified as being in the CU, SCD, MCI, or AD groups, according to whether they met each of the following four core clinical criteria, which are summarized and operationalized in Table 1 and described in the following text.

Table 1. Core diagnostic criteria for COMPASS-ND participant groups reported in this paper

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; CU, cognitively unimpaired; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; SCD, subjective cognitive decline.

a Impaired memory is defined as <9 for 16+ years of education.; <5 for 8–15 years of education; <3 for 0–7 years of education; from the Wechsler Memory Scale – Revised.

b The total MoCA score was used to determine the diagnostic criterion. For purposes of determining whether there was specific evidence of memory impairment, this was defined as recalling fewer than two out of five words on the MoCA delayed recall.

Cognitive Complaints. This consists of an expressed concern regarding a change in cognition from either the participant and/or the study partner. Subjective cognitive impairment is a self-experienced persistent decline in cognitive capacity in comparison with a previously normal status and unrelated to an acute event. This is operationalized as answering ‘yes’ to both of the following questions: ‘Do you feel like your memory or thinking is becoming worse?’ and ‘Does this concern you?’ (see Jessen et al., Reference Jessen, Amariglio, Van Boxtel, Breteler, Ceccaldi, Chételat, Dubois, Dufouil, Ellis, Van Der Flier, Glodzik, Van Harten, De Leon, McHugh, Mielke, Molinuevo, Mosconi, Osorio, Perrotin and Wagner2014).

Impaired Cognition. Participants who demonstrate impairment in one or more cognitive domains on the screening battery are deemed to have impaired cognition. This is operationalized according to the criteria in Table 1 and includes performance on the Delayed Recall of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (WMS-R) Logical Memory Story A (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1987), the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Word List Recall (Welsh et al., Reference Welsh, Butters, Mohs, Beekly, Edland, Fillenbaum and Heyman1994), the MoCA (Nasreddine et al., Reference Nasreddine, Phillips, Bedirian, Charbonneau, Whitehead, Collin, Cummings and Chertkow2005), and the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR; Morris, Reference Morris1993).

Loss of independence in functional abilities is operationally defined as a participant scoring less than 14 out of 23 on the Lawton–Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scale (Lawton & Brody, Reference Lawton and Brody1969).

Dementia is defined clinically as a having a Global CDR score > 0.5.

As operationalized in Table 1, CU participants meet none of the criteria indicating impaired cognition or cognitive complaints; participants with SCD only meet the criterion for cognitive complaints but otherwise had normal cognition on screening; MCI participants have cognitive complaints, impaired cognition on screening, but intact IADL and CDR ratings ≤0.5; and participants with AD had cognitive complaints, impaired cognition on screening, and impaired IADL and were clinically judged to have dementia (see Chertkow et al. (Reference Chertkow, Borrie, Whitehead, Black, Feldman, Gauthier, Hogan, Masellis, McGilton, Rockwood, Tierney, Andrew, Hsiung, Camicioli, Smith, Fogarty, Lindsay, Best, Evans and Rylett2019) for full details). Given the screening battery, we anticipate that the majority of the MCI participants will have amnestic MCI, defined as having an impaired score on at least one of the memory tests administered during screening. Although researchers will be free to decide, we anticipate that most will base their variable for group definitions on the final physician diagnostic evaluation of the participant after information from the clinical and MRI visits is available for review.

Development and design of the neuropsychological research battery

Development of the battery took place from June 2014 to mid-2015 by the CCNA Neuropsychology Working Group, through a series of monthly and ad hoc teleconferences in coordination with the CCNA Clinical Platform Working Group. These working groups consisted of research and clinical neuropsychologists, neurologists, geriatricians, and CCNA staff across Canada, including those who practise in both official languages.

The Neuropsychology Research Battery was designed to:

-

1) Have parallel versions in English and French;

-

2) Have adequate range, sensitivity, and normative values to assess cognitive abilities in older adult participants who differ widely in the level and nature of their cognitive difficulties;

-

3) Have some harmonization with ongoing Canadian research initiatives (the Canadian Longitudinal Study of Aging (CLSA; Raina et al., Reference Raina, Wolfson, Kirkland, Griffith, Oremus, Patterson, Tuokko, Penning, Balion, Hogan, Wister, Payette, Shannon and Brazil2009); the Quebec Consortium pour l’Identification précoce de la Maladie d’Alzheimer (CIMA-Q; Belleville et al., Reference Belleville, LeBlanc, Kergoat, Calon, Gaudreau, Hébert, Hudon, Leclerc, Mechawar, Duchesne, Gauthier, Bellec, Belleville, Bocti, Calon, Chertkow, Collins, Cunnane and Villalpando2019); the Ontario Neurodegenerative Disease Research Initiative (ONDRI; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sunderland, Beaton, Binns, Kwan, Levine, Orange, Peltsch, Roberts, Strother and Troyer2021); and non-Canadian research initiatives, including the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) and the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC)).

-

4) Be comprehensive yet minimize burden on participants and testing staff.

With the exception of three computerized tasks, the neuropsychological research battery was designed to be relatively low-tech and similar to the kind of evaluation that might be carried out in a typical memory clinic or clinical practice. The battery assessed cognitive function in the following seven domains: premorbid IQ, processing speed, attention and working memory, complex attention and executive function, learning and memory, visuoperceptual processing, and speech and language processing. All domains are assessed with two or more tests (with the exception of premorbid intelligence, which was assessed through the WAIS-III Vocabulary test plus interpretation of demographic indicators, including education level and vocational status). The inclusion of two or more tests allows for a robust assessment of each cognitive domain, permits the computation of composite scores, and reduces the likelihood that group differences in a cognitive domain are merely due to the idiosyncrasies of any one test. Given the number of data collection sites (32) at the time of study initiation, the large number of participants, and associated costs, we considered tests that were either in the public domain or for which affordable research agreements could be negotiated.

French adaptations of the tests

English and French are Canada’s two official languages, and most participants were tested in their preferred language. Certain neuropsychological measures were translated or adapted into French for the purposes of our study through collaboration with the CIMA-Q, an allied research consortium on early dementia in Quèbec. In some cases, the choice of a test was motivated by the fact that a long-standing adaptation existed in Quèbeçois French (i.e., Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Third Edition (WAIS-III) Vocabulary Subtest Wechsler (Reference Wechsler1997a); Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) Schmidt (Reference Schmidt1996)). In cases where the stimuli were either non-verbal in nature (i.e., the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised (BVMT-R Benedict et al. (Reference Benedict, Schretlen, Groninger, Dobraski and Shpritz1996)); WAIS-III Digit Symbol Coding Wechsler (Reference Wechsler1997a); CCNA Simple and Choice Reaction Time (RT) Measure; CCNA n-Back Task; Trail Making Tombaugh (Reference Tombaugh2004); Birmingham Object Recognition Battery (BORB) Object Decision Task Riddoch & Humphreys (Reference Riddoch and Humphreys1993); Judgment of Line Orientation Benton et al., (Reference Benton, Sivan, Hamsher, Varney and Spreen1994)) or linguistically simple (i.e., WAIS-III Digit Span (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1997a), Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (DKEFS) Letter and Category Fluency Tests; Delis et al., Reference Delis, Kaplan and Kramer2001), test instructions were translated into French or available standardized translations were used. In instances where test materials were newly adapted (NACC language tests; National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, nd), this was undertaken by fluent speakers of French and English, who were typically native speakers of French. Materials were then back-translated into English to ensure accuracy. Further details are provided in the Supplemental Materials.

Test descriptions

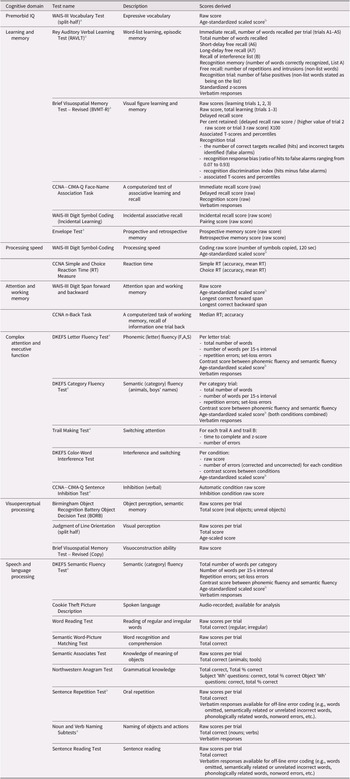

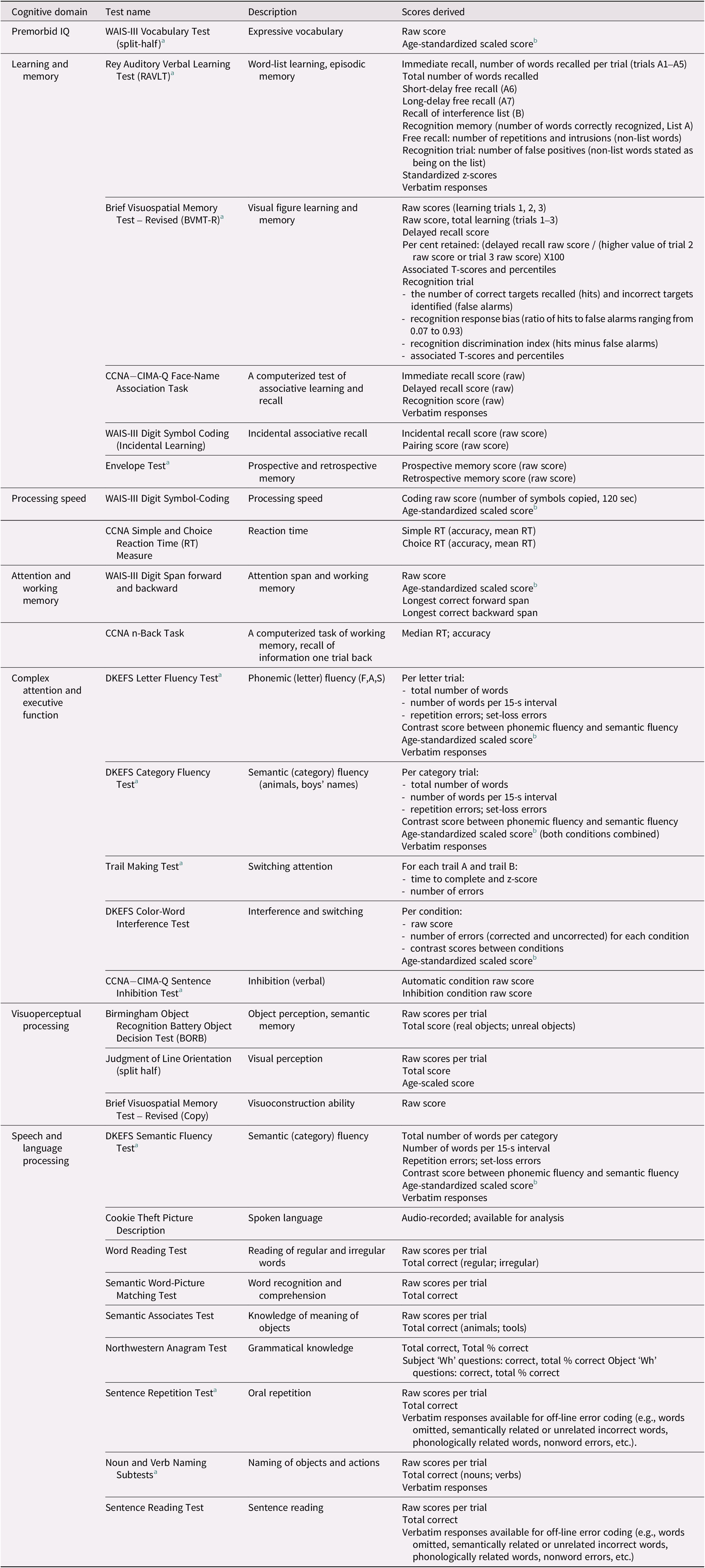

Table 2 provides an overview of the tests, the general cognitive domain implicated, and the test scores available on LORIS. Detailed descriptions of the standard published neuropsychological tests are provided in the Supplemental Materials. The experimental tasks are described below.

Table 2. Neuropsychological tests in the COMPASS-ND battery

a Indicates a test that was monitored for quality control 100% of the time.

b Mean = 10, SD = 3.

CIMA-Q face name matching

This is an experimental face–name associative memory test, adapted from the CIMA-Q (Belleville et al., Reference Belleville, LeBlanc, Kergoat, Calon, Gaudreau, Hébert, Hudon, Leclerc, Mechawar, Duchesne, Gauthier, Bellec, Belleville, Bocti, Calon, Chertkow, Collins, Cunnane and Villalpando2019). In this task, a participant is shown a series of individual black-and-white photographs of nine faces (five women and four men), with a written first name appearing under each photograph. Each face–name pair appears on the screen for 8 seconds. The examiner simultaneously reads the name out loud (e.g., ‘This is Charles’) and asks the participant to remember the face and the name. Immediately after this learning block, the participant is shown the same nine pictures one at a time and in a different order, without the associated names, and is asked to name each one. The participant has 10 seconds to respond to each face (immediate recall). After a 20-minute delay, during which other non-interfering tasks are administered, each face is shown again, and the participant is asked to recall the associated name (delayed recall, maximum score = 9). Finally, during the recognition test phase, the participant is shown each of the nine faces with a name, and they are asked to determine whether the name is: (1) the correct name corresponding to that face, (2) a name that was previously seen but which was associated with a different face, or (3) a new name that was not seen before (three trials each; associative recognition, maximum score = 9). Raw scores are recorded for this task.

CCNA Reaction Time (RT) task

This computerized task is adapted from the one developed by Bielak et al. (Reference Bielak, Hultsch, Strauss, MacDonald and Hunter2010) and consists of both simple and choice RT conditions. In the simple RT task, the trial sequence consists of the presentation of a cue (three black vertical lines with a random duration of 500, 1000, 1500, 2000, or 2500 ms; hex colour #000000) followed by a green cross (hex colour #048E00, 400 pixels, Arial font, centre position). The participant is asked to press a button as fast as possible in response to the target, which remains visible until a response is made. The inter-trial interval is 1025 ms. The task consists of five practice trials, followed by 50 test trials.

In the four-choice RT task, the trial sequence consists of a cue (a row of four grey squares approximately 72 pixels apart) followed by the target 1000 ms later, in which one of the squares randomly changes into a coloured ‘X’. Each grey box is a ballot box html symbol (#9744) with a font size of 164 pixels and hex colour #555555. The coloured X’s are red (#DD0000), yellow (#EFE41F), blue (#2C43DB), and orange (#FFA500), sized 164 pixels in Arial font. The participant is asked to press one of four buttons on the keypad corresponding to the location and colour of the ‘X’ as fast as possible. The target remains visible until a response is made. The inter-trial interval is 1025 ms. There are 10 practice trials, followed by 60 test trials.

For both RT tasks, per-trial and average RT (ms) and accuracy (number of correct responses) were recorded.

CCNA n-back task

This is an n-back test of working memory in which the participant is asked to respond according to information seen on the previous trial. The trial sequence and timing are identical to those of the four-choice RT task except that when the stimulus X appears, the participant is asked to press one of the four buttons to indicate the location of the stimulus seen on the previous trial (i.e., 1 trial back), not the current one. There are 10 practice trials and 61 test trials, with accuracy measured for test trials 2–61.

Sentence completion task

This computerized task is a modification of the task used by Belleville et al. (Reference Belleville, Rouleau and Van der Linden2006), which was itself adapted from the original Burgess and Shallice (Reference Burgess and Shallice1996) Hayling task. The task measures the suppression of an overlearned verbal response in the context of a strong sentence cue. Participants hear a male voice speaking a series of 20 pre-recorded sentences through the study laptop. For each sentence, the last word is missing. Participants are asked to respond by saying a word that either fits the end of the sentence (automatic condition) or is unrelated to the sentence (inhibition condition). Each trial begins with a black centre fixation cross (1500 ms duration) that remains during the auditory presentation of the sentence. Fifty milliseconds after the offset of the sentence, a green circle or a red stop sign appears to indicate whether the sentence should be completed with a related (automatic) or unrelated (inhibition) word, respectively. An example sentence from the automatic condition is: ‘He bought them in the candy…’, with the appropriate high-frequency response being ‘shop’. An example sentence from the inhibition condition is: ‘They went as far as they…’. Here, the participant must inhibit the dominant response of ‘could’ and produce a semantically unrelated word. The participants’ oral response is recorded by the computer and written by the examiner. The examiner then presses a button to proceed to the next trial.

There are four practice trials (two per condition) and 20 test trials (10 per condition, randomly intermixed). Automatic condition trials are given a score of 3 or 0 for correct (related) or incorrect (unrelated) responses, respectively. Inhibition condition trials are scored as 3, 1, or 0. A score of 3 is given for completely contextually and semantically unrelated words. A score of 1 is given for antonyms and words that are related but partially out of context for the sentence. A score of 0 is given for expected words. Thus, for both conditions, a higher score indicates better performance. These data are not reported here as they were not available for analysis at the time of this report.

Equipment

Computerized tasks were administered on a Dell XPS 9343 laptop running Ubuntu 16.04 LTS operating system with a 13-inch display. Responses were entered using a Targus numeric keypad (SKU: AKP10CA) with coloured buttons. Examiners were provided with a Philips DVT6000 Voice Tracer Digital Recorder with which to audio-record test sessions and participant responses. A Pocketalker® Ultra was provided to amplify sound for participants who failed the hearing test in the initial screening visit.

Procedure

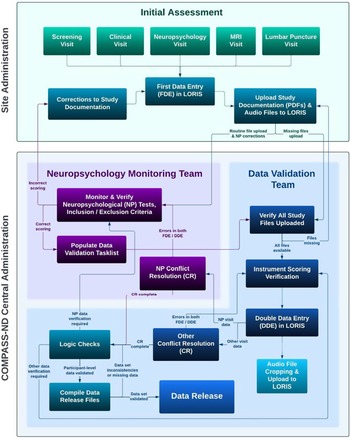

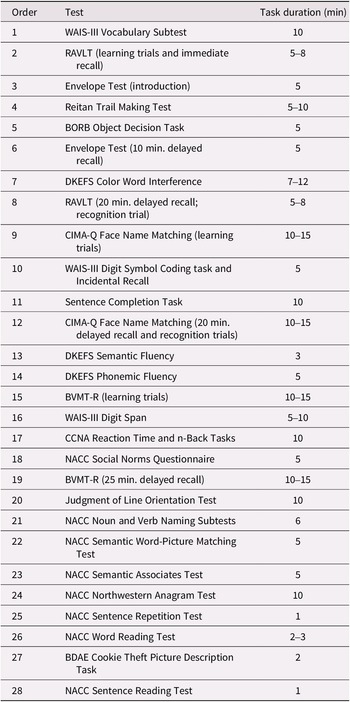

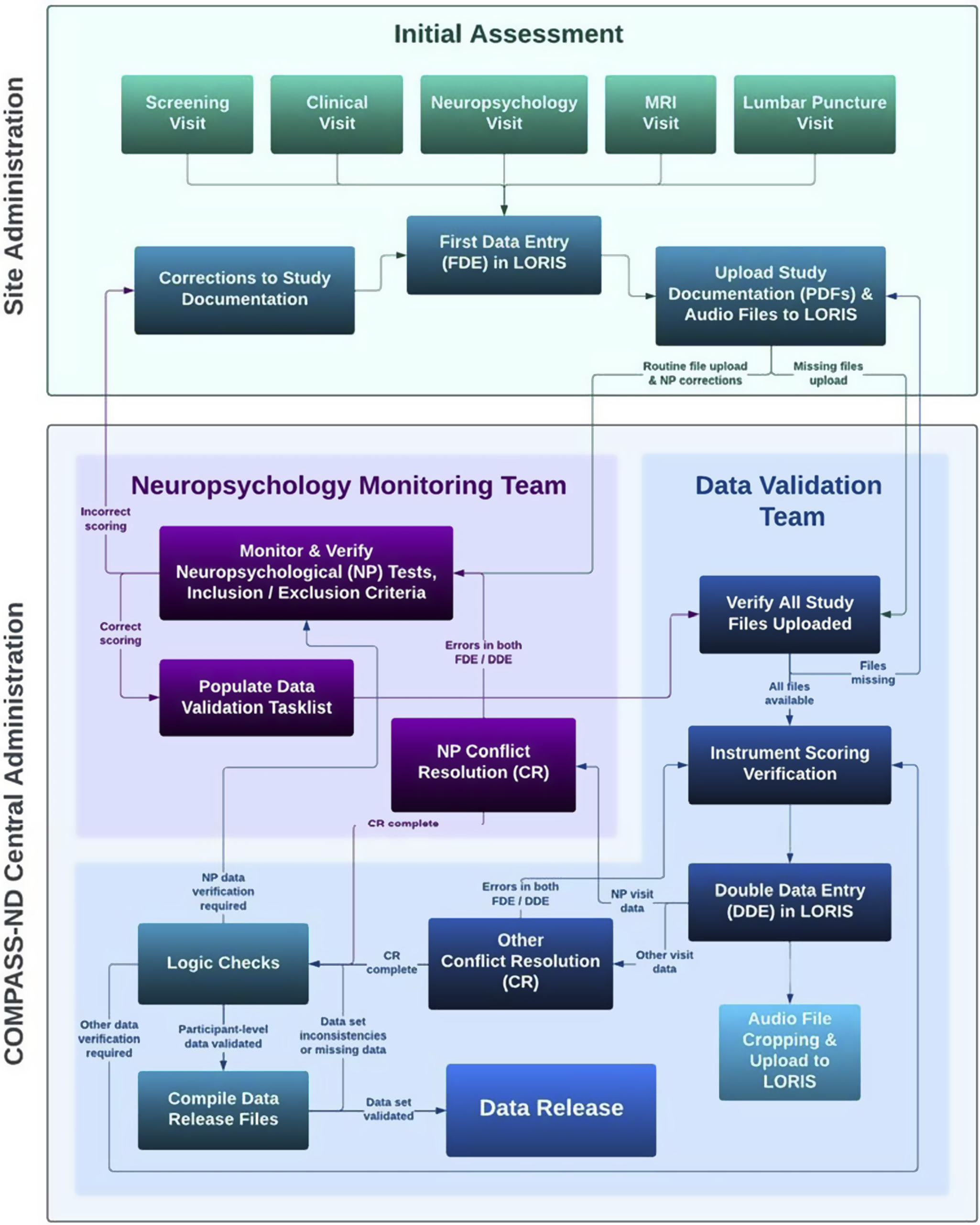

Figure 1 and the supplemental materials provide details on the rigorous process of staff training, data collection, and data verification. The neuropsychological research battery is administered in a separate visit, approximately 3 hours in length, following the screening and clinical visits. Participants are tested individually in a quiet, well-lit examination room, with the majority tested during the morning. The approximate order of testing (to ensure compliance with delayed test timings) is shown in Table 3.

Figure 1. Data collection in COMPASS-ND consists of the remote training of site staff by CCNA Central Administration staff. Data are collected by site staff and are uploaded to LORIS. The central neuropsychology data monitoring team monitor the uploaded data against the paper and audio records and resolve any discrepancies with the data collection staff.

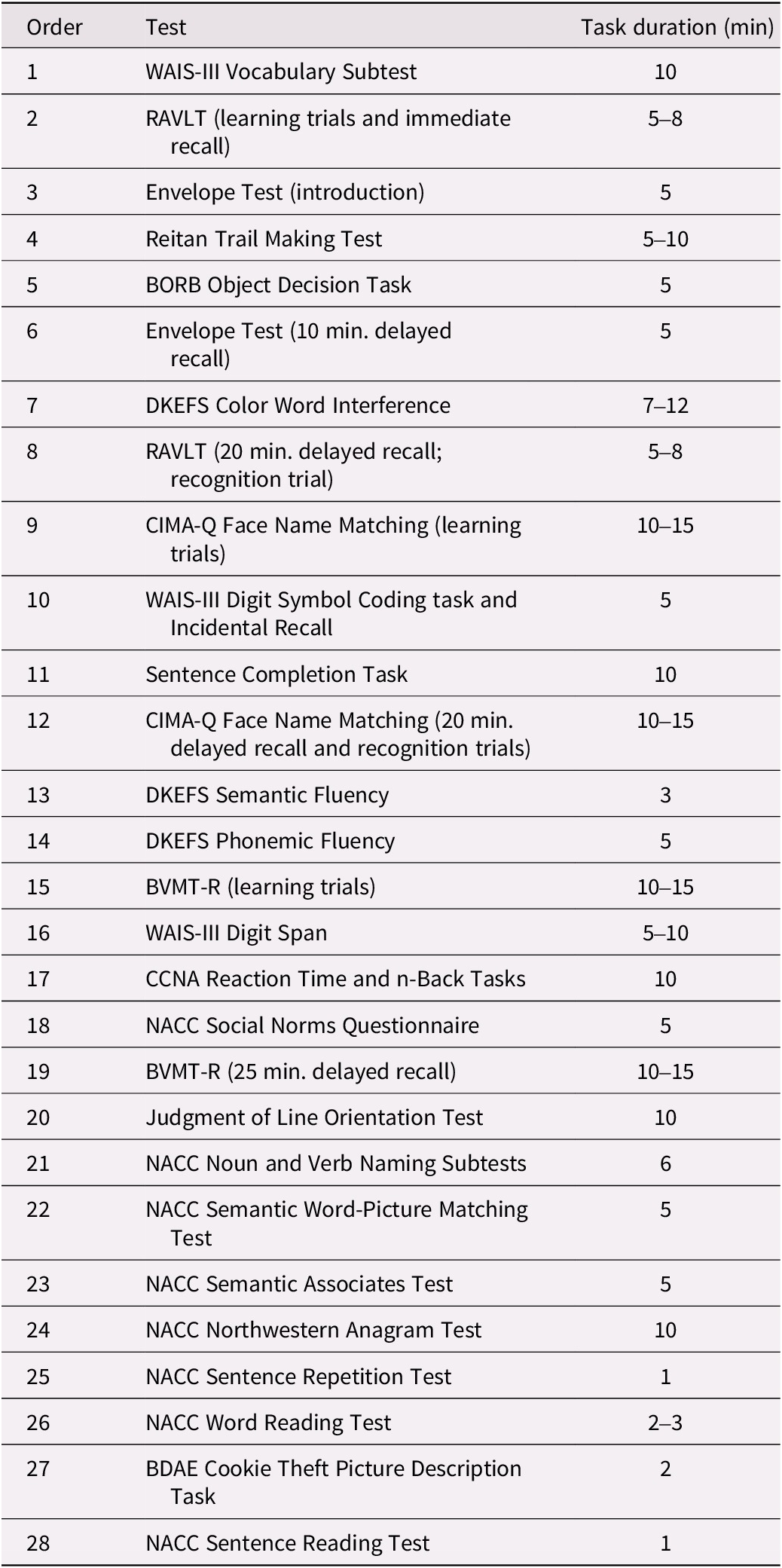

Table 3. Approximate order of administration and time duration of neuropsychological tests

Note: Total testing time took between 3 and 3.5 hours, with appropriate breaks.

Abbreviations: BDAE, Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination; BORB, Birmingham Object Recognition Battery; BVMT-R, Brief Visuospatial Memory Test – Revised; CCNA, Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging; CIMA-Q, Quebec Consortium pour l’Identification précoce de la Maladie d’Alzheimer; DKEFS, Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System; NACC, National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center; RAVLT, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; WAIS-III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Third Edition.

Discussion

This research note provides a foundational reference for the development and description of the COMPASS-ND cognitive test battery and available scores to support researchers who will be using the forthcoming data.

The COMPASS-ND neuropsychological research battery is designed to be sensitive to early symptoms of cognitive impairment in participants at risk of developing AD, namely those with MCI. Preliminary data suggest that this goal was met (Phillips & Fogarty, Reference Phillips and Fogarty2023). At the group level, MCI participants performed more poorly than CU participants on virtually all tests of neuropsychological function, indicating that the majority of the MCI participants were amnestic and also had deficits in multiple domains of cognition. It is not surprising that the MCI group have significant memory deficits since this is one of the screening criteria for inclusion (i.e., the MCI participants had to fail at least one of four screening measures, three of which involved memory testing). Notably, COMPASS-ND participants with MCI also have impairments in other cognitive domains, which indicates that many of them are best characterized (at least as a group) as multidomain MCI (i.e., md-MCI; Jak et al., Reference Jak, Bangen, Wierenga, Delano-Wood, Corey-bloom and Bondi2009). This pattern appears typical for participants recruited from memory clinics and underscores the commonality of these extra-memory deficits despite inclusion criteria heavily weighted towards memory. Future analyses will follow the MCI cohort longitudinally as a recent meta-analysis has shown that those with an amnestic presentation are more likely to progress to dementia than those with a non-amnestic presentation (Oltra-Cucarella et al., Reference Oltra-Cucarella, Sánchez-SanSegundo, Lipnicki, Crawford, Lipton, Katz, Zammit, Scarmeas, Dardiotis, Kosmidis, Guaita, Vaccaro, Kim, Han, Kochan, Brodaty, Pérez-Vicente, Cabello-Rodríguez, Sachdev and Ferrer-Cascales2019; see also Glynn et al., Reference Glynn, O’Callaghan, Hannigan, Bruce, Gibb, Coen, Green, Lawlor and Robinson2021). There is also some evidence that individuals with amnestic-only MCI have more pronounced memory deficits than those with md-MCI (Lopez et al., Reference Lopez, Becker, Jagust, Fitzpatrick, Carlson, DeKosky, Breitner, Lyketsos, Jones, Kawas and Kuller2006), although other studies have observed the opposite pattern (e.g., Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Arnold, Dawson, Nestor and Hodges2009).

Subsequent work using the test battery will identify whether there are distinct neuropsychological patterns demonstrated by sub-groups of participants and whether these subtypes are associated with different neuroanatomical and neurofunctional patterns, and different genetic, biological, and/or cardiovascular risk factors. MCI is a heterogeneous category, with commonly observed cognitive subtypes including profiles described as amnestic, dysexecutive, dysnomic, and visuospatial subtypes (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Delano-wood, Libon, Mcdonald, Nation, Bangen, Jak, Au, Salmon and Bondi2013; Machulda et al., Reference Machulda, Lundt, Albertson, Kremers, Mielke, Knopman, Bondi and Petersen2019). With larger sample sizes in subsequent data releases, researchers will be able to identify cognitive sub-groups at baseline and follow participants longitudinally to determine whether any of these neuropsychological profiles are associated with a greater risk of conversion to dementia.

There has been recent discussion about the differences in methods for diagnosing MCI, contrasting results from the use of the traditional approach (i.e., ≤1.5 SD below normal on a single test with a cognitive domain) versus more comprehensive criteria (≤ 1 SD below normal on at least two tests within a domain) (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Delano-wood, Libon, Mcdonald, Nation, Bangen, Jak, Au, Salmon and Bondi2013). The former has the potential to be overly sensitive and prone to error, misdiagnosing individuals as having MCI when, in reality, they are cognitively normal on the majority of tests. One strength of the COMPASS-ND research battery is that it contains several tests within a given cognitive domain, allowing researchers to classify impairment based on more than one test, leading to more reliable diagnoses (Edmonds et al., Reference Edmonds, McDonald, Marshall, Thomas, Eppig, Weigand, Delano-Wood, Galasko, Salmon and Bondi2019) and identification of potential MCI cognitive subtypes.

Analysis of the future COMPASS-ND data will determine whether any of the univariate neuropsychological test scores can distinguish participants with SCD from CU participants. This can be challenging since, by definition, SCD individuals have cognitive complaints but normal test performance (Jessen et al., Reference Jessen, Amariglio, Van Boxtel, Breteler, Ceccaldi, Chételat, Dubois, Dufouil, Ellis, Van Der Flier, Glodzik, Van Harten, De Leon, McHugh, Mielke, Molinuevo, Mosconi, Osorio, Perrotin and Wagner2014) and the COMPASS-ND inclusion criteria for this group require normal test scores on all of our screening measures (MoCA, Logical Memory II, CERAD, and CDR; see Table 1). However, future analyses will explore the possibility that subtle deficits in cognition may be identified in SCD participants, either by calculating novel scores on traditional tests (e.g., the primacy position in recall on the RAVLT; Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Guerreiro, De Mendona, Oliveira and Santana2012; Bruno et al., Reference Bruno, Grothe, Nierenberg, Zetterberg, Blennow, Teipel and Pomara2015), by determining whether there are subtle alterations in the interrelationship of cognitive domains using network analyses, or by connected speech analyses (Filiou et al., Reference Filiou, Bier, Slegers, Houzé, Belchior and Brambati2020). Recent work indicates that COMPASS-ND SCD participants show altered cognitive networks that exhibit an organization with characteristics that are intermediate between the networks of CU and MCI participants (Grunden & Phillips, Reference Grunden and Phillips2024).

Strengths and limitations

The COMPASS-ND research battery has several advantages. It consists of well-known and widely available tests that are currently used in many Canadian memory clinics and are used in many clinic and community-based studies of dementia, allowing for cross-comparison with a number of national (e.g., CIMA-Q, CLSA) and international studies (e.g., NACC, ADNI, Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI)). Many of the tests are non-proprietary (e.g., the RAVLT) and have been adapted for use in Canadian French. Although not used to form the initial clinical study diagnoses, the neuropsychology research battery allows for the application of the National Institute on Aging – Alzheimer’s Association diagnostic guidelines for MCI due to AD (Albert et al., Reference Albert, DeKosky, Dickson, Dubois, Feldman, Fox, Gamst, Holtzman, Jagust, Petersen, Snyder, Carrillo, Theis and Phelps2011) and dementia due to AD (McKhann et al., Reference McKhann, Knopman, Chertkow, Hyman, Jack, Kawas, Klunk, Koroshetz, Manly, Mayeux, Mohs, Morris, Rossor, Scheltens, Carrillo, Thies, Weintraub and Phelps2011).

Nevertheless, several limitations should be noted. Current recruitment (Borrie et al., Reference Borrie, Pilon, Phillips, Fogarty, Best, Fouquet, Beuk, Gnassi, Aydoğan, Beaudoin, Henri-Bellemare, Gajraj, Tucker, Das, Truemner, Sands, Celotto, Cole and Chertkow2025) indicates that the groups are not balanced on sex. Women are over-represented in the CU and SCD groups, and men are over-represented in the AD group. The former issue is likely due to the common volunteer bias towards older women in CU groups. The latter issue may be due to the requirement that participants have a study partner participate in the study and that female caregivers might be more inclined to participate with their partner with dementia compared to male caregivers (Stites et al., Reference Stites, Largent, Gill, Gurian, Harkins and Karlawish2022). CCNA researchers are currently engaged in targeted recruitment to achieve more equitable representation of men and women in our samples, which will allow disaggregation of the data to examine potential differences due to sex and gender. This is critical because understanding the role of sex and gender is a key mandate of the CCNA through its Women, Sex, Gender and Dementia platform (Chertkow et al., Reference Chertkow, Phillips, Rockwood, Anderson, Andrew, Bartha, Beaudoin, Bélanger, Bellec, Belleville, Bergman, Best, Bethell, Bherer, Black, Borrie, Camicioli, Carrier, Cashman and Wittich2024). There are known sex and gender differences in cognition, dementia risk, and trajectories (e.g., Au et al., Reference Au, Dale-McGrath and Tierney2017; Mielke et al., Reference Mielke, Aggarwal, Vila-Castelar, Agarwal, Arenaza-Urquijo, Brett, Brugulat-Serrat, DuBose, Eikelboom, Flatt, Foldi, Franzen, Gilsanz, Li, McManus, van Lent, Milani, Shaaban, Stites and Babulal2022; Sohn et al., Reference Sohn, Shpanskaya, Lucas, Petrella, Saykin, Tanzi, Samatova and Doraiswamy2018; Sundermann et al., Reference Sundermann, Biegon, Rubin, Lipton, Mowrey, Landau and Maki2016; Sundermann et al., Reference Sundermann, Maki, Biegon, Lipton, Mielke, Machulda and Bondi2019). For instance, there is initial evidence that hearing loss is more closely coupled with cognitive performance in women than in men among COMPASS-ND MCI participants (Al-Yawer et al., Reference Al-Yawer, Pichora-Fuller, Wittich, Mick, Giroud, Rehan and Phillips2022).

Monitoring of recruitment indicates that the current COMPASS-ND sample is highly educated (Borrie et al., Reference Borrie, Pilon, Phillips, Fogarty, Best, Fouquet, Beuk, Gnassi, Aydoğan, Beaudoin, Henri-Bellemare, Gajraj, Tucker, Das, Truemner, Sands, Celotto, Cole and Chertkow2025). Through outreach to community groups and targeted recruitment in memory clinics, efforts are now underway to recruit more individuals with lower levels of education (i.e., those with up to 12 years of education, plus life experience) to more closely resemble the typical educational attainment for this age group. When the final data set is available on participants with a wider range of education, researchers will be able to examine the potential relationship with cognitive reserve (for which education is an important proxy; Stern et al., Reference Stern, Arenaza‐Urquijo, Bartrés‐Faz, Belleville, Cantilon and Chetelat2020) on progression to dementia.

COMPASS-ND contains a large array of neuropsychological data, and researchers will be able to access the full set of available scores (summarized in Table 2). Although the neuropsychology research battery does not form the basis of the clinical research diagnosis and thus could be considered independent, the diagnostic clinical screening battery relies heavily on cognitive testing of memory. When the COMPASS-ND biomarker data become available, researchers will be able to determine the agreement between clinical and cognitive diagnostic indicators and disease biomarkers. Lastly, any information about the evolution of the cognitive status of participants must wait until the longitudinal data are collected and released. Future work will use the longitudinal follow-up of CU participants to compute and improve the sensitivity of the test battery to the detection of cognitive impairment (Kaser et al., Reference Kaser, Kaplan, Goette and Kiselica2023).

Conclusions

This paper describes the development and content of the COMPASS-ND neuropsychological research battery to serve as a protocol reference. Future research will develop normative values from the CU group in the final data set to facilitate cross-test comparisons and robust norms and the computation of cognitive profiles of the patient participant groups. These baseline cognitive data will set the groundwork for future analysis of the biometric, sensory, clinical, neuroimaging, and genetic data that will be available on more than 1500 COMPASS-ND participants.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980825100330.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by an infrastructure and operating grant to the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) with funding from several partners [Grant numbers CNA-137794, CNA-163902, and BDO-148341]. NAP was supported by a Concordia University Research Chair in Sensory-Cognitive Health in Aging and Dementia.

We are indebted to the COMPASS-ND research participants, their study partners, and site staff for their time.

We are grateful to Dr. Sandra Weintraub for her sharing of materials from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center.