Introduction

Public administrations are designed to deliver essential services and uphold societal functions, yet the processes governing these interactions often impose significant burdens on citizens. The administrative burden framework provides a lens for examining the obstacles citizens face when engaging with public services, emphasizing the real-world consequences of administrative rules and processes (Campbell, Pandey and Arnesen, Reference Campbell, Pandey and Arnesen2023). These burdens are not mere inconveniences but can shape how individuals perceive and interact with the state and can reinforce systemic inequalities. Vulnerable populations, particularly those with limited human or social capital, are disproportionately affected, as they often lack the resources needed to navigate complex bureaucratic systems (Moynihan et al., Reference Moynihan, Herd and Harvey2015; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen2020).

Refugees, including asylum seekers, typically face numerous challenges both before and throughout the settlement process (Pierobon, Reference Pierobon2024; Moynihan et al., Reference Moynihan, Gerzina and Herd2022). Prior to and during migration, they may endure severe and sometimes life-threatening circumstances such as violence and war (Pierobon, Reference Pierobon2024). Upon arrival in the receiving country, they often encounter uncertainty regarding their legal status and face difficulties in learning a new language, entering the labor market, and accessing social services, including healthcare, financial aid, and integration programmes (Pierobon, Reference Pierobon2024). These challenges are further compounded by heightened administrative burdens stemming from their unfamiliarity with local legal frameworks and bureaucratic systems, leading to increased stress, confusion, and obstacles in obtaining essential services (Moynihan, Gerzina and Herd, Reference Moynihan, Gerzina and Herd2022; Chudzicka-Czupała et al., Reference Chudzicka-Czupała2023).

Such issues are particularly salient in the context of the recent Ukrainian refugee crisis – one of the largest displacement events in modern European history. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, approximately 6.8 million Ukrainian asylum seekers have been registered across Europe (UNHCR, 2022). Switzerland responded by activating the protection status S, a temporary protection measure designed to simplify asylum procedures. This policy allowed Ukrainian asylum seekers to secure temporary protection rapidly, bypassing the invasive and time-intensive evaluations typical of asylum processes. While the policy eased immediate administrative challenges, understanding how asylum seekers experienced the process remains crucial.

To explore these experiences, our study combines quantitative survey data with open-ended qualitative responses. Specifically, we focus on two critical resources that can mitigate administrative burdens: bureaucratic self-efficacy and social capital. Bureaucratic self-efficacy reflects an individual’s perceived ability to navigate and influence bureaucratic systems effectively (Bisgaard, Reference Bisgaard2023). Complementing this, social capital encompasses the network-based support individuals receive from family, friends, third-sector organisations, and social media, which can act as a buffer against administrative challenges (Masood and Azfar Nisar, Reference Masood and Azfar Nisar2021; Döring and Madsen, Reference Döring and Madsen2022). Using a survey distributed via a Zurich-based NGO’s Telegram channel, we assessed asylum seekers’ experiences of administrative burden and collected qualitative comments to contextualise and deepen our quantitative findings. This dual approach allows for a comprehensive understanding of how both individual and social resources shape interactions with the asylum system.

This study contributes to several ongoing debates within public administration and migration research. First, it advances the administrative burden literature by applying it to the high-stakes policy area of refugee protection, where the consequences of burden are particularly acute and time-sensitive. Second, it sheds light on the role of individual-level resources, especially bureaucratic self-efficacy and social capital, in shaping experiences with public services, while also unpacking the complexity of social capital by distinguishing between bonding, bridging, and particularly linking social capital, which remains underexplored in this field. Third, by studying administrative burden in the context of Switzerland’s streamlined asylum policy (status S), the study expands current research beyond traditional, highly complex bureaucratic processes. Finally, the study contributes to bridging the often-siloed fields of public administration and migration studies, offering an interdisciplinary lens on how vulnerable populations interact with the state. Taken together, these contributions offer both conceptual and practical insights into how institutional and social environments shape the accessibility of public services.

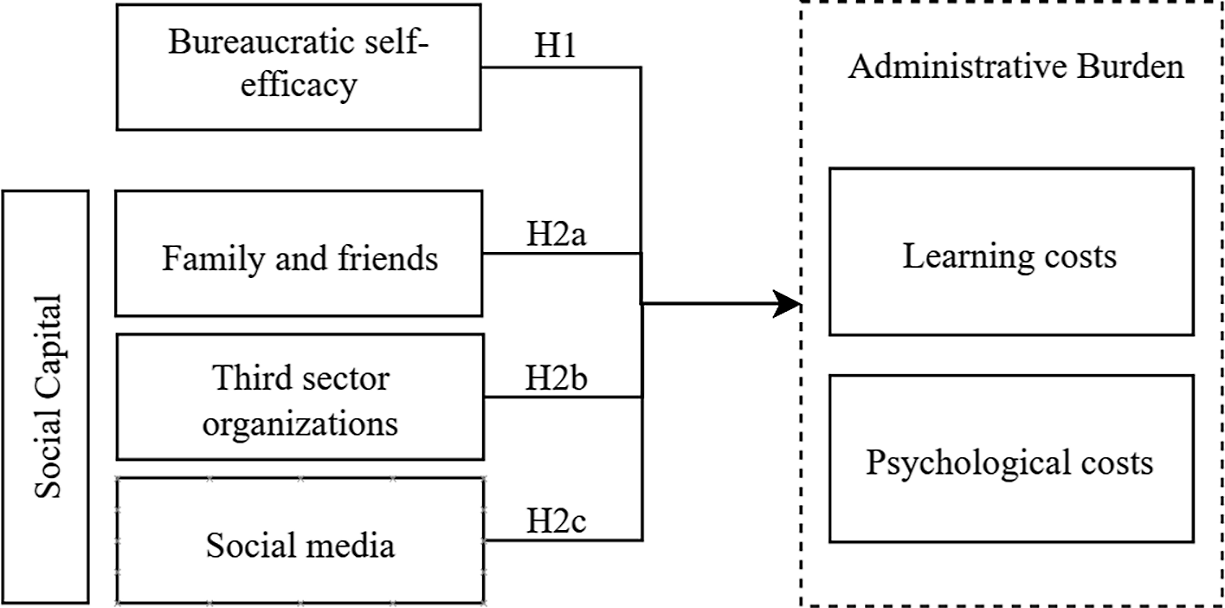

Figure 1. Research model.

Theoretical background and literature review

Understanding the distributive effects of administrative burden

The administrative burden framework offers a citizen-centred perspective on the origins and consequences of burdensome administrative rules (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Pandey and Arnesen2023). While primarily focused on the citizen experience, the framework recognises that such rules may serve legitimate purposes, such as preventing fraud in social welfare programmes (Moynihan et al., Reference Moynihan, Herd and Harvey2015). A key tenet of this framework is the distinction between state actions and citizens’ experiences, emphasising that state-imposed rules and procedures significantly shape these experiences and influence citizens’ ability to access public services (Halling and Baekgaard, Reference Halling and Baekgaard2024).

Moynihan et al. (Reference Moynihan, Herd and Harvey2015) identify three types of costs that citizens encounter when dealing with administrative burdens. Learning costs arise from the time and effort needed to understand programme eligibility, benefits, and access requirements (Herd and Moynihan, Reference Herd and Moynihan2019). Compliance costs involve the resources – time, effort, and finances – required to meet administrative obligations. Psychological costs stem from stress associated with navigating bureaucratic systems or stigma related to less favourable programmes that may undermine personal autonomy.

Crucially, these costs are not borne equally. Distributive consequences often fall disproportionately on individuals with limited human or social capital, further entrenching inequality (Nisar, Reference Nisar2018; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen2020; Chudnovsky and Peeters, Reference Chudnovsky and Peeters2021; Döring, Reference Döring2021; Masood and Azfar Nisar, Reference Masood and Azfar Nisar2021; Döring and Madsen, Reference Döring and Madsen2022; Bisgaard, Reference Bisgaard2023). Human capital, encompassing traits like education, cognitive functioning, personality, and health, plays a pivotal role in mitigating administrative burdens (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen2020). Social capital, on the other hand, reflects the strength of an individual’s networks and community support (Masood and Azfar Nisar, Reference Masood and Azfar Nisar2021; Döring and Madsen, Reference Döring and Madsen2022; Pierobon, Reference Pierobon2024).

Vulnerable populations, such as refugees, face heightened barriers. Paradoxically, while they are often the most in need of support, these groups are also more likely to experience negative interactions with the state, withdraw from services, or renounce benefits altogether (Moynihan et al., Reference Moynihan, Gerzina and Herd2022). Refugees are increasingly subject to administrative burdens that make legal and social processes more confusing, demanding, and stressful (Moynihan et al., Reference Moynihan, Gerzina and Herd2022; Chudzicka-Czupała et al., Reference Chudzicka-Czupała2023; Safarov, Reference Safarov2023; Pierobon, Reference Pierobon2024). These challenges underscore the importance of resources like bureaucratic self-efficacy, which is a person’s confidence in their ability to navigate complex bureaucratic systems, and social capital, which provides external support through networks and community ties. This study examines these two key resources to better understand how individuals cope with administrative burden, particularly within vulnerable populations.

Bureaucratic self-efficacy

Citizen-state interactions are often complex and highly technical due to legal regulations underlying public services, the higher social status of state institutions, and citizen’s dependence on state decisions (Döring, Reference Döring2021). A key challenge for asylum seekers is to navigate complex and fragmented information landscapes in the host country, which often hinders their access to relevant information and limits their full participation in the new community (Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd2013; Tazzioli, Reference Tazzioli2022; Sprenkamp et al., Reference Sprenkamp2025). Within this context, possessing knowledge of bureaucratic rules and procedures empowers individuals to engage more effectively with public organizations (Masood and Azfar Nisar, Reference Masood and Azfar Nisar2021). Academic literature conceptualises this type of knowledge in various ways. For instance, Döring (Reference Döring2021) applies the framework of health literacy to develop the concept of administrative literacy. He defines aadministrative literacy as the ability to ‘obtain, process and understand basic information and services from public administrations needed to make appropriate decisions’ (Döring, Reference Döring2021 :1). Research shows that individuals with low administrative literacy experience elevated stress levels when navigating administrative procedures, whereas those with higher literacy feel more autonomous and self-efficacious in handling complex or stressful situations (Döring and Madsen, Reference Döring and Madsen2022).

In this study, we build on the concept of bureaucratic self-efficacy, introduced by Bisgaard (Reference Bisgaard2023) who emphasises the importance of citizens’ subjective perceptions of their ability to navigate and influence bureaucratic decisions. He defines bureaucratic self-efficacy as ‘citizens’ assessment of their own capabilities to cope and navigate with public encounters in order to influence decision-making’ (Bisgaard, Reference Bisgaard2023 :46). This concept combines two essential components: bureaucratic competence and self-efficacy. Bandura’s (1977) foundational work on self-efficacy underscores that individuals’ expectations about their capabilities determine the extent to which they persist in overcoming obstacles or aversive experiences. Accordingly, individuals with lower self-efficacy – such as older adults, less educated individuals, or those experiencing poverty – are less likely to engage in administratively demanding situations (Linos et al., Reference Linos2022) or experience greater psychological costs (Thomsen et al., Reference Thomsen, Baekgaard and Jensen2020).

Bureaucratic self-efficacy encompasses not only knowledge of bureaucratic processes, rules, and regulations but also the communicative skills required to navigate these processes effectively (Bisgaard, Reference Bisgaard2023). Citizens acting as service recipients must understand the administrative system while being able to clearly articulate their needs and concerns to public authorities. Without these combined capabilities, navigating administrative procedures becomes increasingly burdensome. However, despite the theoretical appeal of bureaucratic self-efficacy, the concept remains relatively new, and few studies have explored its influence on perceptions of administrative burden. Given these insights, we hypothesise:

H1 Individuals with higher levels of bureaucratic self-efficacy will experience lower administrative burden.

Social capital

Whereas bureaucratic self-efficacy refers to individual-level competence in navigating state processes, social capital captures the external, relational resources that individuals can draw upon to manage bureaucratic challenges. It reflects the extent and quality of social connections – from family and peers to civic organisations and institutions – which can provide access to information, assistance, and emotional support. Scholars commonly distinguish between three forms of social capital: bonding capital (close-knit relationships with similar others), bridging capital (connections across different social or cultural groups), and linking capital (ties to institutions or individuals in positions of authority) (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000; Woolcock, Reference Woolcock2001; Pierobon, Reference Pierobon2024). Each form facilitates access to different types of support and may play a distinct role in reducing administrative burden. Studies show that individuals embedded in rich social networks can access help with completing forms, understanding processes, or managing stress, thereby mitigating their burden (Masood and Azfar Nisar, Reference Masood and Azfar Nisar2021; Peeters and Campos, Reference Peeters and Campos2021; Döring and Madsen, Reference Döring and Madsen2022; Safarov, Reference Safarov2023; Yang and Wang, Reference Yang and Wang2024).

Bonding capital: support from family and friends

Close ties within one’s ethnic or social community (bonding capital) can be vital in the early stages of asylum and integration. Friends and relatives often help interpret bureaucratic language, complete paperwork, and offer reassurance throughout the process (Masood and Azfar Nisar, Reference Masood and Azfar Nisar2021). Refugees commonly rely on both official and community-based sources of information, with messaging apps like Telegram playing an important role in peer-based exchange (Oduntan and Ruthven, Reference Oduntan and Ruthven2019). However, such support may be limited when individuals within the same network are equally unfamiliar with the host country’s administrative landscape or face similar challenges.

Bridging and linking capital: the role of third-sector organisations

While bonding capital offers emotional and practical support, bridging and especially linking social capital play a critical role in connecting marginalised individuals with institutional knowledge and resources. Third-sector organisations – including NGOs, charities, religious associations, and volunteer groups – represent a key conduit of linking social capital. These actors provide access to individuals or institutions in positions of authority and help users engage with formal systems more effectively (Pierobon, Reference Pierobon2024; van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Steinhilper and Sommer2025).

Third-sector organisations are particularly vital in migration contexts, where asylum seekers often encounter fragmented, opaque, or inaccessible bureaucratic systems (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, López and Dalceggio2024; Sprenkamp et al., Reference Sprenkamp2025). Empirical research from the UK, Germany, Turkey, and Hungary shows that NGOs often fill institutional gaps by offering translation services, administrative guidance, or advocacy during interactions with welfare, health, or legal authorities (Zihnioğlu and Dalkıran, 2022; Feischmidt et al., Reference Feischmidt2025; Pierobon, Reference Pierobon2024). Tomlinson et al. (Reference Tomlinson2024) highlight that such organisations help refugees understand how host country systems function and support them in accessing critical services like healthcare or benefits. In many cases, volunteers act as intermediaries who ease psychological costs and reduce barriers to formal participation.

Importantly, third-sector actors not only assist individuals but also challenge or complement state efforts, engaging in what has been described as co-production or collaborative governance (Brandsen and Pestoff, Reference Brandsen and Pestoff2006; Milward and Provan, Reference Milward and Provan2000). Tiggelaar and George (Reference Tiggelaar and George2023) emphasise that non-state actors increasingly participate in the delivery of public services and can advocate for burden reduction in policy design. Halling and Baekgaard (Reference Halling and Baekgaard2024) similarly argue that these actors play a structural role in redistributing administrative burden, especially when governments fall short. Tomlinson et al. (Reference Tomlinson2024) further emphasise that administrative burden should be understood as something that can be shared – either informally among citizens or formally between citizens and support organisations.

However, the broader contribution of these actors in rebalancing the citizen-state relationship remains underexplored (Tiggelaar and George, Reference Tiggelaar and George2023; Halling and Baekgaard, Reference Halling and Baekgaard2024; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson2024). Without recognising the distributed nature of burden and the hybrid governance structures supporting asylum seekers, our understanding of administrative burden risks being overly narrow.

Ambiguous capital: the role of social media

Social media, too, can act as a component of social capital by enabling both bonding and bridging connections. While often overlooked in public administration research, social media platforms have become crucial for the exchange of both emotional support and practical information (de Zúñiga et al., Reference de Zúñiga, Barnidge and Scherman2017; Masood and Azfar Nisar, Reference Masood and Azfar Nisar2021). Dekker and Engbersen (Reference Dekker and Engbersen2014) and Dekker et al. (Reference Dekker2018) show that migrants use social media not only to maintain existing ties, but also to build new connections and gain insider knowledge. For instance, Syrian asylum seekers have been found to rely on trusted digital networks – such as Telegram groups – to access firsthand advice based on shared experience (Dekker et al., Reference Dekker2018).

These examples illustrate that social media occupies an ambiguous position within the social capital framework. It blurs traditional boundaries between bonding, bridging, and potentially even linking capital, as it may connect users to both peer networks and institutional actors. Such hybrid spaces can help users navigate information environments that are otherwise difficult to access or interpret (Oduntan and Ruthven, Reference Oduntan and Ruthven2019). Lloyd et al. (Reference Lloyd2013) argue that refugees achieve social inclusion when information is mediated through trusted individuals or visual and social channels. However, the effectiveness of social media depends on the credibility and cultural embedding of the sources involved. Without trusted intermediaries or connection to formal institutions, such information can also mislead or overwhelm.

In sum, support from family, NGOs, and social media contributes to the redistribution of administrative burdens. These networks assist individuals either by taking on parts of bureaucratic processes or by equipping them to do so more effectively (Benish et al., Reference Benish2023). However, the existing literature suggests that the interplay between different types of social capital can be complex and difficult to disentangle. Based on these theoretical considerations, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2 Individuals with greater social capital will experience lower administrative burden. Specifically:

H2a Individuals with strong support from family and friends will experience lower administrative burden.

H2b Individuals who receive assistance from third-sector organisations will experience lower administrative burden.

H2c Individuals who frequently exchange information and seek support through social media will experience lower administrative burden.

Our two hypotheses can be summarised according to the following model.

Data and method

Case setting: the Swiss asylum policy for Ukrainian asylum seekers

To test our hypotheses, we draw on the case of the Swiss asylum policy facing the Ukrainian refugee crisis. According to official data, since the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, around 6.8 million asylum seekers from Ukraine have been registered across Europe (UNHCR, 2022). By the end of 2022, Switzerland granted more than 72,000 permits for temporary protection, following an adaptation of its refugee policy that simplified the procedure for Ukrainian citizens at the beginning of 2022 (State Secretariat for Migration, 2023a). The high number of people seeking protection justified the activation of the protection status S, which allowed Ukrainian asylum seekers to obtain temporary protection rapidly and without the in-depth individual examination needed for the normal asylum procedures. The adoption of the protection status S follows the temporary protection awarded to Ukrainian asylum seekers under the European Union’s Temporary Protection Directive (European Commission, 2022) which is not directly applicable to Switzerland.

Once Ukrainian asylum seekers had entered the country, they needed to go to a federal asylum centre where their application for the status S was registered. An appointment could be made through an online platform (RegisterMe) through which a train ticket to the asylum centre could also be obtained. Once the application for protection was registered, the person concerned was allocated to an accommodation in a canton, if he or she did not already have a private one. In this case, the asylum seeker was assigned to the given canton. The canton was then in charge of providing accommodation, health insurance, financial assistance, as well as the formal permit recognising the status S (State Secretariat for Migration, 2023b).

Ukrainian asylum seekers are considered a highly skilled population (Züricher and Paone, Reference Züricher and Paone2022) and could be expected to have stronger capabilities when it comes to navigating the administrative system. While many Ukrainian asylum seekers joined family members, friends, or acquaintances already living in Switzerland, civil society’s engagement towards Ukrainian asylum seekers was also particularly strong (Brotschi, Reference Brotschi2022). NGOs have provided help with basic needs (housing, healthcare, and administrative assistance) (Meyer-Vacherand, Reference Meyer-Vacherand2022). Nonetheless, recent research points to persistent structural challenges in the Swiss administrative landscape. Ukrainian refugees frequently reported fragmented and unclear information, with no single comprehensive source covering essential topics such as childcare, housing, travel, medical care, or work permits (Sprenkamp et al., Reference Sprenkamp2025). As a result, many relied on community-based sources – especially open Telegram channels – which, while accessible, occasionally spread misinformation. A further barrier was the limited engagement between refugees and local authorities, often due to a lack of personnel, which left many asylum seekers without adequate in-person or digital follow-up after registration.

Sample

In July 2023, we disseminated our questionnaire through a Zurich-based NGO aimed at helping Ukrainians established in Switzerland. The NGO shared our research project on its Telegram page. Telegram stands out as the preferred communication platform among Ukrainians (Sweney, Reference Sweney2022), serving not only as a vital source for war-related news but also to maintain connections with relatives (Alazab and Macfarlane, Reference Alazab and Macfarlane2022; Sprenkamp et al., Reference Sprenkamp2025). Within this group of around 7000 subscribers, 151 people responded to our survey, which corresponds to a response rate of 2.16 per cent. We excluded fourteen responses due to missing data. Since we collected sensitive data, we submitted a request to the ethics commission of our faculty at the University of Lausanne which accepted our project on the condition that the data is stored securely.

Ukrainian asylum seekers cannot choose between the twenty-six cantons in Switzerland but are instead assigned, thereby mitigating the influence of other potential factors on residents’ selection. Zurich, being the primary destination for asylum seekers in Switzerland – with 15,000 arrivals recorded at the end of July 2023 (State Secretariat for Migration, 2023c) – hosts a significant number of Telegram channels catering to the Ukrainian community.

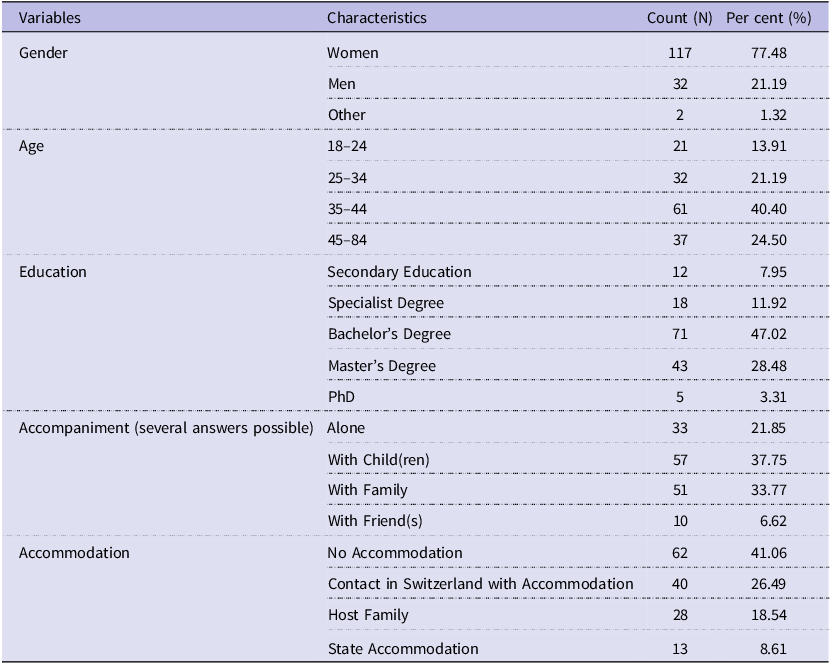

Table 1 shows the sample characteristics and descriptive statistics of participants. Women are overrepresented in our sample since many men are obliged to stay in Ukraine to fight in the war, a pattern that is also reflected in other studies on Ukrainian refugees (e.g., Pierobon, Reference Pierobon2024). The majority is between thirty-five and forty-four years old, arrived in Switzerland accompanied by either children or other family members, and had no accommodation when they arrived. Our data indicates that, on average, Ukrainians experienced a two-month wait period (administrative delay) until they were granted status S protection after their initial registration. Moreover, we captured information on participants’ language proficiency upon arrival to ascertain any potential correlation between language skills and the perceived administrative burden (Safarov, Reference Safarov2023). We considered proficiency in English, Ukrainian, and Russian, alongside the official languages of Switzerland – German, French, and Italian. Given that the canton of Zurich is German-speaking, proficiency in this language was of particular interest. However, among our questionnaire participants, 68 per cent reported no proficiency in German. The highest reported proficiency level was B1-B2, observed in just two participants.

Table 1. Sample characteristics and descriptive statistics of participants

Our sample appears to reflect the demographic profile of Ukrainian asylum seekers in Switzerland, as corroborated by a study examining their integration into the Swiss job market. This research found that 76 per cent of participants were women, predominantly aged twenty-five to forty-four, with 75 per cent holding a university degree (Hänggi, Reference Hänggi2022).

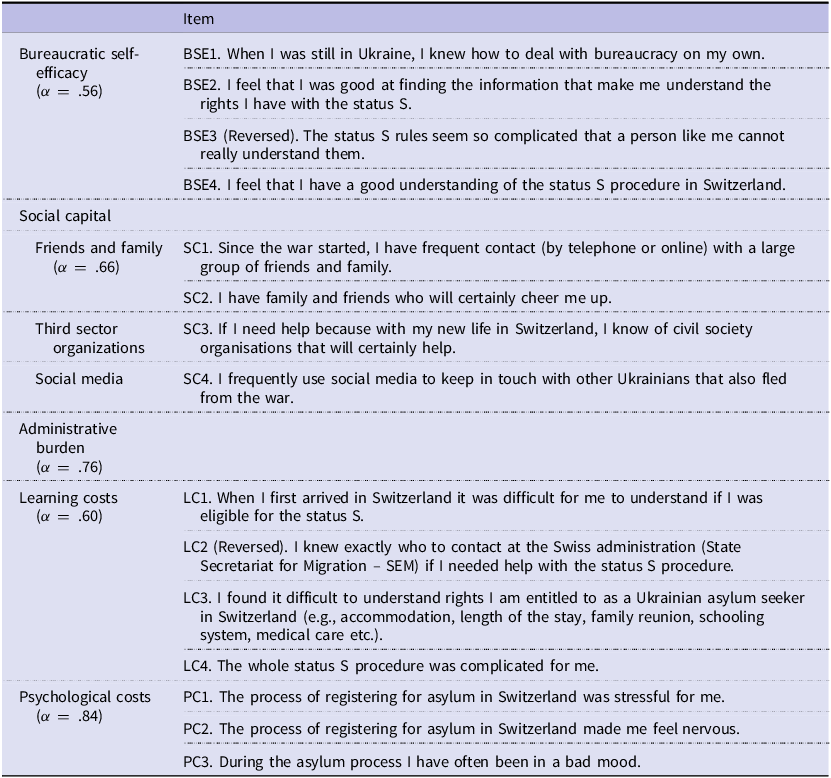

Research design and measures

The questionnaire contained seventeen questions, taking participants around ten minutes to complete. Bureaucratic self-efficacy was measured using items from Bisgaard (Reference Bisgaard2023). Social capital was operationalised using four items adapted from Döring and Madsen (Reference Döring and Madsen2022), who in turn built on Chen et al. (Reference Chen2008), as well as de Zúñiga et al. (Reference de Zúñiga, Barnidge and Scherman2017) to capture social media-related forms of support relevant to the Ukrainian refugee context. The social media item primarily reflects bonding capital through peer contact within the Ukrainian community. However, as highlighted in recent research, social media often blurs the boundaries between bonding, bridging, and even linking forms of social capital, particularly when it serves both emotional and informational functions. This conceptual overlap is addressed in the discussion section when interpreting the findings.

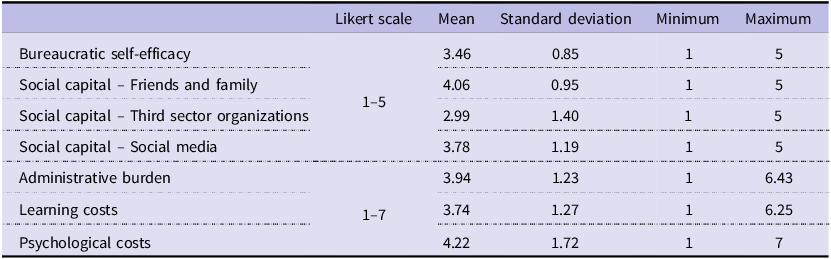

Administrative burden was assessed through psychological and learning costs. Psychological costs were measured using items adapted from Döring and Madsen (Reference Döring and Madsen2022), tailored to the specific context of asylum-seeking. While it is reasonable to assume that individuals fleeing a war would experience significant psychological distress, we carefully adapted these items to specifically capture the psychological costs associated with the asylum process itself. This approach aims to isolate the impact of administrative procedures from the broader psychological effects of displacement. Learning costs were measured using items from Madsen and Mikkelsen (Reference Madsen and Mikkelsen2022), also adjusted for the asylum-seeking context (Table 2). We chose not to measure compliance costs, as our focus was on the initial administrative procedure in Switzerland, where asylum seekers did not face many compliance requirements due to the relatively straightforward granting of status S for Ukrainian asylum seekers. To contextualise participants’ experiences and assess the extent of administrative burden and related variables, Table 3 presents descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum) for the key variables.

Table 2. Measurement of variables

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for key variables

The questionnaire was made available in Ukrainian, Russian, and English. A Ukrainian colleague conducted the translations following comprehensive briefings and in-depth discussions to ensure accuracy and clarity in the wording. Prior to distribution, the questionnaire was pre-tested with seven participants referred by our Ukrainian colleague, leading to minor survey adjustments.

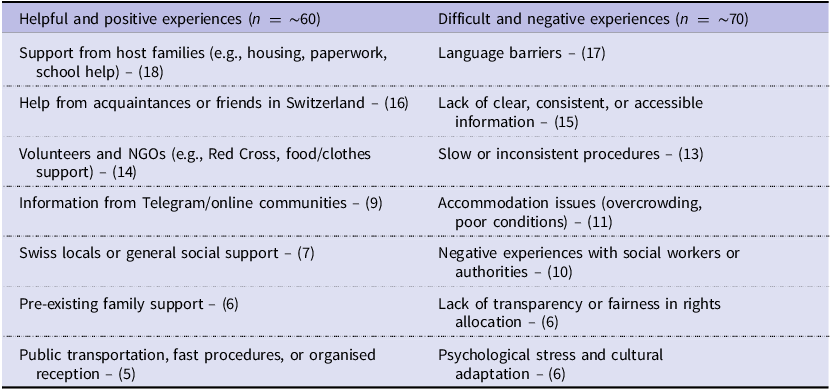

As part of the survey, two open-ended questions were included to collect qualitative data on the participants’ experiences: (1) ‘Please briefly describe what you felt was helpful to organise your arrival and first weeks in Switzerland’; and (2) ‘Please briefly describe what you felt was difficult when organising your arrival and first weeks in Switzerland.’ We conducted a basic thematic categorisation of these responses to identify recurring topics and illustrate how participants perceived both support and burden during the early phase of their stay (Table 4).

Table 4. Qualitative responses

Analysis

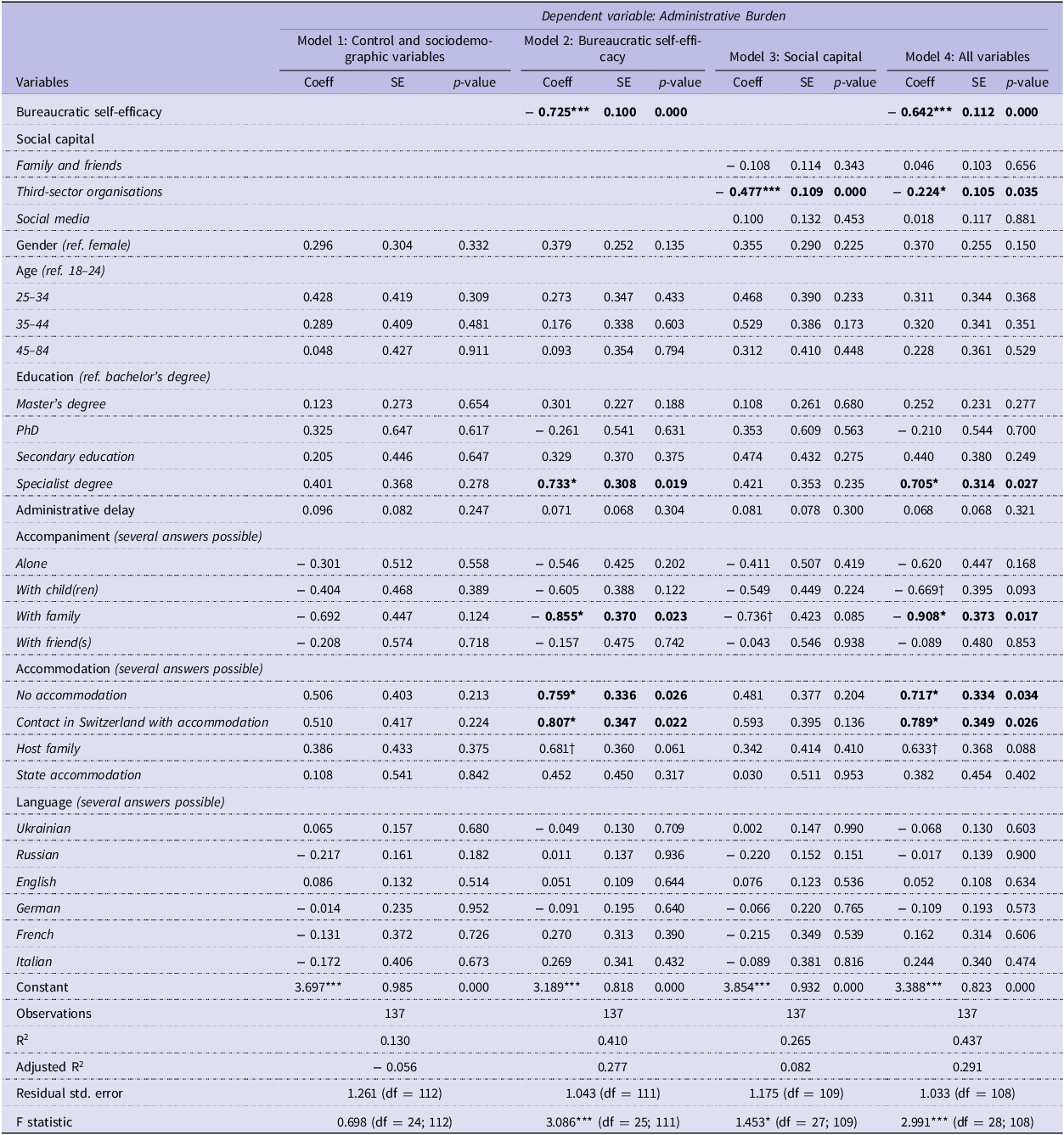

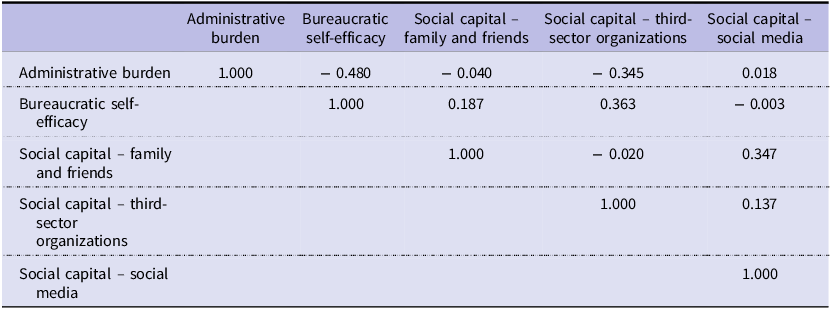

We conducted multiple linear regression and estimated four distinct models (Table 6). In the first model, we examined the effect of control and sociodemographic variables. The second model tested H1, where we included bureaucratic self-efficacy as the independent variable. In the third model, we accounted for social capital, operationalised through support from family and friends, third-sector organisations, and social media. Finally, in the fourth model, we included all variables together to assess their combined effects. To provide a preliminary assessment of the relationships between the variables, we also computed a correlation matrix, which is presented in Table 5. All models were estimated in the R environment for statistical computing. To check for multicollinearity between predictor variables, we computed variance inflation factors for all regression models (VIF). The generalised variance inflation factors ranged between 1.17 and 2.17. We therefore assumed that multicollinearity was not an issue as all VIF were below the common thresholds of five or ten (James et al., Reference James2021 :102).

Table 6. Results from multiple linear regression

p < .001 = ‘***’.

p < .01 = ‘**’.

p < .05 = ‘*’.

p < .10 = ‘†’.

Table 5. Correlation matrix

Results

Regarding hypothesis one, we find support for the hypothesis that individuals with higher levels of bureaucratic self-efficacy experience lower administrative burden (Model 2: b = − 0.725, SE = 0.100, p = 0.000). For hypothesis two, we find partial support for the hypothesis that individuals with greater social capital experience lower administrative burden. Specifically, we find support for H2b, which posits that individuals who receive assistance from third-sector organisations will experience lower administrative burden (Model 3: b = − 0.477, SE = 0.109, p = 0.000). However, we find no support for H2a or H2c. Notably, descriptive statistics (Table 3) show that perceived access to third-sector support was lower than for both family-based support and social media. This suggests that although support from third-sector organisations is statistically associated with reduced burden, such support may not be widely available or accessible to all respondents.

Bureaucratic self-efficacy (H1) and social capital through third-sector organisations (H2b) remain significant even when included together in one model (Model 4). While both variables are significant, bureaucratic self-efficacy is a stronger predictor of experiencing lower administrative burden than receiving assistance from third-sector organisations. The adjusted R2 is highest in Model 4, suggesting that this model, which incorporates all variables, provides the best fit for the data.

Several control variables were assessed, but most showed no significant effect on reducing experiences of administrative burden. The length of time asylum seekers waited for their status S (administrative delay) did not appear to have an impact. Similarly, whether individuals arrived alone, with children, with family, or with friends did not influence their experiences of administrative burden. Age also had no discernible effect, nor did the ability to speak one of the Swiss languages.

The qualitative responses (Table 4) provided additional insights into participants lived experiences. Positive experiences most frequently mentioned support from host families, friends, NGOs, and volunteers, highlighting the importance of both bonding and linking forms of social capital. Difficulties, on the other hand, often related to language barriers, lack of accessible information, and procedural confusion. These patterns align with the quantitative findings that emphasize the role of third-sector organisations and bureaucratic self-efficacy in shaping administrative burden. However, the absence of a significant relationship between bonding social capital and administrative burden is mirrored in the qualitative data, where friends and family were less frequently described as sources of concrete support for navigating bureaucratic processes.

Discussion

This study offers new insights into the experiences of administrative burden among Ukrainian asylum seekers in Switzerland by examining the interplay between individual and social resources. Building on both public administration and migration studies, we find that higher levels of bureaucratic self-efficacy are associated with significantly lower perceived administrative burden, highlighting the importance of individual competence in navigating bureaucratic systems. In addition, support from third-sector organizations – representing a form of linking social capital – emerges as a particularly important external resource, more impactful than support from family, friends, or social media. This suggests that institutionalised support networks play a critical role in mitigating administrative barriers, especially in contexts of forced migration. While bonding and bridging forms of social capital may offer emotional and informational support, their effect appears less consistent. These findings are reinforced by open-ended responses, which illustrate the practical and emotional value of organisational support. Taken together, the results underscore the need for a more nuanced and context-sensitive understanding of social capital in administrative burden research and provide actionable insights for improving service delivery for asylum seekers.

Individual competence: the role of bureaucratic self-efficacy

The strong effect of bureaucratic self-efficacy highlights the important role of individuals’ confidence in their ability to navigate bureaucratic systems. This aligns with prior research showing that self-efficacy empowers individuals to approach administrative tasks more proactively, perceive them as less intimidating, and overcome challenges more effectively (cp. Gilad and Assouline, Reference Gilad and Assouline2022; Bisgaard, Reference Bisgaard2023). In the context of asylum seekers, where systems may be unfamiliar and daunting, cultivating bureaucratic self-efficacy is particularly crucial. Policymakers could enhance administrative outcomes by implementing programmes that boost asylum seekers’ bureaucratic self-efficacy, such as orientation sessions, training, and tailored guidance during the asylum procedure.

The comments left by participants in the open-ended sections confirm this tendency (Table 4). People who had some form of previous knowledge or administrative literacy felt they were more empowered and able to take on the administrative procedure on their own. Comparatively, limited knowledge about both the language and the Swiss administrative system leads to a feeling of uncertainty, misunderstandings, or disorientation (cp. Sprenkamp et al., Reference Sprenkamp2025). For instance, a respondent mentions that their ‘lack of language skills, lack of knowledge of local laws, rules, and procedures’ negatively impacted their ability to understand the status S procedure. Another person recalls problems mainly linked to language proficiency which posed significant problems when trying to understand the overall situation:

…without knowing the language, we didn’t immediately realise that the confirmation letter of status approval was already the status itself. During the first month, we thought that the status is when they give us a card. […] In fact, we didn’t know anything, and the social service didn’t explain anything to us during the initial period about what would happen to us.

Institutional support and intermediaries: the importance of third-sector organisations

The significant role of third-sector organisations suggests that institutionalised support networks, such as non-profits and civic organisations, serve as critical intermediaries between asylum seekers and bureaucratic processes (cp. Zihnioğlu and Dalkıran, 2022; Safarov, Reference Safarov2023; Tiggelaar & George, Reference Tiggelaar and George2023; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, López and Dalceggio2024; Feischmidt et al., Reference Feischmidt2025). Such structured interventions are likely more reliable and systematic compared to informal support networks. This finding contributes to the growing literature on linking social capital – ties with individuals or institutions in positions of authority – which facilitates access to public services and has only recently gained traction in migration research (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000; Woolcock, Reference Woolcock2001; Pierobon, Reference Pierobon2024; van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Steinhilper and Sommer2025).

Moreover, the significance of third-sector organisations points to the growing role of intermediaries in public service delivery aligning with the broader literature on collaborative governance and co-production of public services, where state and non-state actors work together to fill gaps (Milward and Provan, Reference Milward and Provan2000; Brandsen and Pestoff, Reference Brandsen and Pestoff2006; Tiggelaar and George, Reference Tiggelaar and George2023). The finding underscores the need to adequately fund and support these organisations to sustain their ability to assist vulnerable populations effectively.

At the same time, descriptive statistics reveal that perceived access to third-sector support was the lowest among the three measured forms of social capital – lower than support from family and social media (Table 3). This contrast between demonstrated effectiveness and limited availability is particularly relevant from a policy perspective. It suggests that although NGOs and civil society actors play a key role in reducing administrative burden, their reach may be constrained by factors such as geography, limited awareness among refugees, or resource constraints on the part of the organisations themselves. Bridging this gap is essential to ensure that effective support mechanisms reach those who need them most.

The qualitative comments reinforce this finding, with respondents frequently mentioning organisations like the Red Cross, Caritas, and local volunteers in Switzerland as key sources of support in navigating administrative processes. While our quantitative measure captured perceived access rather than actual utilisation, the qualitative responses suggest that for many participants, this support was not only available in theory but actively used in practice.

The limits of bonding capital and the ambiguous role of social media

Contrary to expectations, social capital derived from family and friends, thus bonding capital, did not significantly reduce administrative burden in this context. One possible explanation is that, due to the sudden displacement caused by the war, many family members or friends were themselves navigating similar bureaucratic challenges in Switzerland or abroad, limiting their ability to provide effective support. In addition, bonding ties may often be geographically dispersed or not sufficiently embedded in the local context to offer hands-on assistance. While such networks can provide emotional reassurance, they may lack the specialised or instrumental knowledge needed to address complex administrative tasks. This may lead some refugees to rely more on formal support structures, such as NGOs or official institutions, which they perceive as more trustworthy and better equipped to handle bureaucratic matters.

The non-significant role of social media is a notable finding, especially given its widespread use as an information-sharing platform among refugee populations. While often viewed as a tool for exchanging practical advice, its effectiveness in reducing administrative burden may be limited for several reasons. First, bureaucratic processes are highly context-specific and often require detailed, localised knowledge that is not easily transmitted through social media. Second, the emotional and instrumental support typically needed to navigate administrative systems may depend on face-to-face or direct interaction – something digital platforms cannot readily provide. Third, privacy concerns may discourage asylum seekers from sharing sensitive information online.

At the same time, this finding contrasts with previous research suggesting that social media – especially when used via trusted intermediaries – can support access to essential services and foster social inclusion (Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd2013; Oduntan and Ruthven, Reference Oduntan and Ruthven2019). These studies emphasise that combining official and peer-based information sources, especially when mediated by culturally embedded actors, may facilitate access to administrative knowledge and enhance social inclusion.

A possible explanation lies in our measurement: the survey item focused specifically on staying in touch with other Ukrainians, primarily capturing bonding capital and emotional connection. However, as discussed in the literature, social media does not fit neatly into a single category of social capital. Depending on how it is used, it may enable bonding, bridging, or even linking connections. Our operationalisation of social media focused on intra-group contact and thus may not have captured more instrumental or cross-cutting forms of support.

Still, several open-ended comments indicate that participants received support through Telegram channels run by volunteers or civil society actors. This suggests that social media may operate as a hybrid space – blurring traditional boundaries between informal networks and formal support structures – and that its role in facilitating access to administrative help is highly context-dependent. Future research should therefore distinguish more precisely between different types of social media use, as important interactions may exist between digital peer networks and institutional actors.

More broadly, the results also highlight the conceptual complexity of social capital, which encompasses diverse and context-dependent social ties, ranging from close personal contacts to institutional actors. The interplay between different types of social capital – bonding, bridging, and linking – is often complex and difficult to disentangle. The qualitative comments (Table 4) reflect this complexity: while not representative, they illustrate how informal support, digital tools, and institutional actors often interact in messy but meaningful ways to shape the lived experience of bureaucracy. Disentangling which types of relationships ultimately reduce administrative burden remains challenging. Future studies should differentiate more explicitly between types of actors within civil society, such as formal NGOs versus informal grassroots initiatives, and explore their interactions with digital platforms. A more granular approach would help clarify under which conditions social capital reduces administrative burden, and when it does not.

Situating the Ukrainian case: differences and commonalities in refugee experiences

Finally, while this study focuses specifically on Ukrainian asylum seekers in Switzerland, it is important to situate their experiences within the broader context of refugee and migration studies. One key difference lies in the reception climate and legal framework. Ukrainians benefited from a highly exceptional policy response marked by openness and solidarity, as reflected in the activation of status S, which offered a simplified and expedited asylum process – a perception that was also echoed in several open-ended comments. This stands in sharp contrast to other recent cases, such as Afghan refugees in the UK, who faced a ‘hostile environment to migration’ even in the aftermath of the 2021 Kabul evacuation (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, López and Dalceggio2024).

Another notable distinction is the socio-demographic profile of the Ukrainian refugee population, which is predominantly female whereas earlier refugee movements, such as in 2015, were largely composed of men (Milewski et al., Reference Milewski2023; Pierobon, Reference Pierobon2024). Despite these differences, several challenges are shared across refugee groups. Fragmented and opaque bureaucratic systems, as well as limited institutional engagement, often leave refugees reliant on community-based information and the support of NGOs to navigate essential services (Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd2013; Oduntan and Ruthven, Reference Oduntan and Ruthven2019; Zihnioğlu and Dalkıran, 2022). In this sense, the Ukrainian experience reflects a broader pattern in which civil society actors step in to bridge the gap between refugees and state institutions.

Implications for policy and future research

Taken together, our findings suggest that administrative burden is not merely a function of system complexity, but also a reflection of unequal access to individual capabilities and institutional support. While support from third-sector organisations appears particularly effective in reducing perceived burden, our descriptive results show that access to such support remains limited, indicating a crucial gap between potential and actual support structures. This underscores the need for targeted investments in intermediaries that can reliably bridge the gap between vulnerable populations and the state.

Moreover, the mixed effects of different forms of social capital – particularly the limited influence of bonding ties and the ambiguous role of social media – highlight the importance of disaggregating social resources. Future research should further differentiate between bonding, bridging, and linking forms of social capital, and examine how they interact in specific institutional contexts. This includes refining how we measure digital engagement and distinguishing between social media use for emotional connection, peer advice, and access to formal support.

Recognising the multiple and overlapping roles of individual agency, civil society actors, and digital infrastructures is essential for designing more equitable and responsive public services – especially for asylum seekers navigating new and often opaque bureaucratic systems.

Limitations

This study has several key limitations. First, the findings are based on the specific group of Ukrainian asylum seekers and a unique policy context (status S), which includes simplified procedures and a generally supportive reception climate. While these factors limit direct generalisability to other refugee groups or more complex asylum systems, the study also identifies several dynamics, such as the role of third-sector organisations and the challenges of fragmented information systems, that appear across diverse refugee experiences and therefore offer broader relevance.

Second, our measurement of bureaucratic self-efficacy has several limitations. First, we focused on procedural knowledge related to administrative rules and processes but did not include communicative dimensions of efficacy, such as the ability to interact with bureaucrats, which have been identified as important in other studies (Bisgaard, Reference Bisgaard2023). This choice was informed by the specific design of the Swiss status S procedure, which did not initially require direct interactions with officials. Second, we did not consider digital literacy, which is a prerequisite for accessing online platforms like RegisterMe. As Safarov (Reference Safarov2023) notes, digital competencies underpin higher-order capacities such as bureaucratic literacy and may be an important antecedent of self-efficacy in digitalised administrative contexts. Third, our items were tied specifically to the status S procedure, which, while capturing respondents’ real-time administrative experiences, may limit the generalisability of the construct beyond this specific policy setting. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the survey means causal claims are limited. For example, it’s unclear whether higher self-efficacy reduces burden or if navigating the system successfully increases self-efficacy.

Third, the non-significant effects of bonding social capital (family and friends) and social media use on administrative burden should be interpreted with caution. While these findings may indicate a limited role of informal networks in this context, they may also reflect measurement limitations. In particular, both constructs were measured using only one item, which may not have fully captured the range and nuance of their potential influence. Future studies should differentiate more precisely between types of digital use and their connection to bonding, bridging, or linking forms of social capital.

Fourth, this study captures the experiences of Ukrainian asylum seekers at a single point in time, specifically during the early phase of the streamlined status S procedure. While this stage is characterised by relatively low administrative complexity, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to assess how administrative burdens evolve as asylum seekers progress through later stages of integration. Future challenges may include accessing language courses, cultural orientation programmes, or navigating complex legal and bureaucratic requirements related to employment, status renewal, or transitioning to permanent residency. Moreover, the temporary nature of status S – closely tied to the geopolitical situation in Ukraine – creates uncertainty that may exacerbate psychological stress and administrative vulnerability over time. For those separated from family members, delayed reunification and related bureaucratic hurdles may also contribute to future burdens. These evolving pressures, combined with the lasting psychological effects of war and displacement (Chudzicka-Czupała et al., Reference Chudzicka-Czupała2023), suggest that administrative burden is not static but may intensify or shift over the course of asylum seekers’ integration journeys.

Fifth, our study focuses on psychological and learning costs but excludes compliance costs, which may provide an incomplete picture of administrative burden during those later stages of integration. Future research could benefit from incorporating a temporal dimension, accounting for the dynamic nature of these burdens.

Sixth, since we recruited participants through an NGO Telegram channel, they may differ from other asylum seekers in terms of resource access, digital literacy, or motivation, potentially skewing the results.

Lastly, our sample is skewed toward females, which reflects the specific demographic pattern of the Ukrainian refugee population, where the vast majority of adult asylum seekers are women due to martial law prohibiting most men from leaving the country. This gender profile is consistent with findings from other studies on the Ukrainian case (Milewski et al., Reference Milewski2023; Safarov, Reference Safarov2023; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson2024), but should not be interpreted as a general trend across all refugee contexts, where gender dynamics may differ depending on the nature of the conflict and displacement pathways.

Conclusion

This study contributes to public administration research by underscoring the critical role of both individual and social resources in shaping how vulnerable populations, particularly refugees, experience administrative burdens. Using the case of Ukrainian asylum seekers in Switzerland, we demonstrate that bureaucratic self-efficacy and social capital can serve as buffers against the challenges posed by complex bureaucratic systems. Importantly, our findings reveal that administrative burden is not experienced uniformly but reflects deeper structural inequities linked to disparities in knowledge, access, and support.

These findings carry broader implications for both theory and practice. First, they call for a more nuanced understanding of how individual capacities and external support networks interact with institutional arrangements. These interactions shape not only access to services but also broader perceptions of the state and its legitimacy. Second, our results emphasise the need for administrative systems that are not only simplified, as seen in the case of Switzerland’s protection status S, but also supported by inclusive, well-communicated, and responsive assistance mechanisms. Even streamlined systems can remain exclusionary without adequate support.

Finally, this study opens important avenues for future research on how administrative burdens intersect with key themes in public administration, such as equity, crisis governance, and the role of intermediary actors. Bridging insights from public administration and migration studies, future work can help develop more inclusive policies that account for the lived realities of diverse populations navigating state systems.

Acknowledgements

We thank our colleague Bohdan Trembovelskyi for his support in translating the survey and comments, assisting with data collection, and liaising with the NGO.

Author Contributions: CRediT Taxonomy

Pascale-Catherine Kirklies: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Iris Sudan: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing - original draft.

Ethical considerations

The ethics commission of our faculty at the University of Lausanne accepted our project on the condition that the data is stored securely.