1. Introduction

In recent years, the notion of scientific collaboration has raised much interest among scholars of different disciplines and backgrounds, coming from domains as diverse as social epistemology and sociology of science, computer science, science policy, cognitive science and philosophy of action, as well as history and philosophy of science. The existing literature offers a wide panorama; perspectives and approaches tend to get superimposed, and scientific collaboration studies have grown as a remarkably interdisciplinary research field.Footnote 1

One of the reasons for this flourishing development is the increasing importance of collaborative research in order to achieve substantial results in practically all domains of the natural sciences. Collaborative research seems to be ubiquitous, particularly in modern science, but the notion of collaboration is not obvious at all. Rather, it is a multifaceted phenomenon, requiring complicated taxonomies that may cover a variety of aspects.Footnote 2 Thus, it is not surprising that the very notion of collaboration is used in diverse contexts and has a broad field of application, being applied to small teams composed of a couple of colleagues as well as to groups of hundreds of researchers.

Particular attention has been paid to the fact that collaborations may look different over times and disciplines. Some scholars have emphasized that scientists from certain fields (e.g., physical and biological sciences, neurosciences, engineering) collaborate more than others, and in certain domains, such as the social sciences, the propensity of researchers to collaborate is more recent than elsewhere (Thagard Reference Thagard1997; Wray Reference Wray2002; Wuchty, Jones, and Uzzi Reference Wuchty, Jones and Uzzi2007). Presumably the need for collaboration is more evident in research projects that require the involvement of several different specialties.Footnote 3 However, there is no consensus about the reasons for the readiness to collaborate and its absence in specific fields, but, although starting from different points of view, many agree that an interplay of the costs and benefits of working together, thus sharing honors and burdens, is somehow involved (Kitcher Reference Kitcher1995; Wray Reference Wray2002; Thagard Reference Thagard2006; Fallis Reference Fallis2006; Wray Reference Wray2006; Muldoon Reference Muldoon, Boyer-Kassem, Mayo-Wilson and Weisberg2017; Zollman Reference Zollman, Boyer-Kassem, Mayo-Wilson and Weisberg2017).

In this paper I argue that, besides collaboration-by-division-of-labor and other motives that may endorse cooperative approaches, there can be intriguing cases where people do collaborate primarily because of strong epistemic requirements. In particular, I will argue that scientific collaboration can occasionally be necessitated and driven by the specific features of the objects of research and the methods of inquiry applied. Of course, I will not argue that these are the only driving forces that press scientists to collaborate, but I will contend that sometimes they are the prevailing factors. To this end, I introduce and discuss the notion of epistemic constraints, which I will employ as a shorthand of such epistemic requirements – and I will term the kind of collaboration where epistemic constraints prevail over other factors, “epistemically constrained collaboration.”

In the pages that follow I will not deal with distinctions between within-discipline and cross-disciplinary contexts, even though the actors at play in my case study may possess different backgrounds. Interdisciplinarity is currently a growing area of investigation that also casts light on collaborative research (see, e.g., Andersen and Wagenknecht Reference Andersen and Wagenknecht2013; Andersen Reference Andersen2016; MacLeod and Nersessian Reference MacLeod and Nersessian2016; Andersen Reference Andersen and Shan2022). However, the argument developed in the present paper is independent from interactions across disciplinary boundaries.

Now let me briefly clarify what it is meant here by “collaboration.” It has been noted that this is a loose concept. To put it like Katz and Martin, whenever we try to establish general criteria for defining what a collaboration really is, “it is all too easy to identify exceptions to virtually all … criteria in particular fields, institutions or countries” (Reference Katz and Martin1997, 8). Still, it can pragmatically be useful to start with a sort of rule of thumb, sufficiently broad (albeit provisional), that may help to circumscribe the subject under investigation. My working definition of collaborative research is inspired by Laudel (Reference Laudel2002, 5) and runs as follows: collaborative research means every approach that aims to achieve a result through operations performed by any number of individual contributors, symmetrically joined together, in a justifiable way.

Invoking a requirement of symmetry, I only intend to emphasize that all contributors should be treated as equally significant with respect to their effort of collaborating. Thus, this does not imply that collaborators must necessarily be equal or “peers” but that their role must contribute to stabilize the process of collaboration. In short, symmetry in this sense is satisfied by adhering to a reciprocity condition, such as: “In order for you to collaborate with me, I must collaborate with you in a justifiable manner.” As obvious as it seems, an important consequence of the symmetry condition as expressed here is that it excludes phenomena of cognitive interdependence and distributed cognition like those mentioned by Cronin (Reference Cronin2004), who seems to assume that (scientific) multi-actor-knowledge is per se (scientific) collaboration.Footnote 4

My assumption is rather that collaborative scientific knowledge and collective knowledge, although related, are not equivalent notions. The latter mostly relies on the public, intersubjective dimension of science on the one hand and on its temporal dimension on the other – something that has early been recognized in a straightforward manner by Ernst Mach: “Forming a general judgment … is not the affair of a moment nor takes place in a single individual alone. All contemporaries, all classes, indeed whole generations and peoples contribute to the consolidation or correction of such inductions” ([1905] Reference Mach1976, 229).Footnote 5 On the other hand, existing studies on collaborative scientific knowledge seem to agree that collaboration requires more stringent conditions, such as an active, reciprocal exchange of ideas toward more or less common goals, possibly shared beliefs and intentions, some kind of coordination among the actors involved, etc. This notwithstanding, as I will argue below, the requirement of symmetry might also be problematic, and there can be non-obvious cases of collaborative research in which the contributors can hardly be considered “symmetrically joined together” in the sense expressed above.

I do not aim to provide a full account of the (general) philosophy of collaboration, which would deserve a special and sufficiently broad study. I rather limit myself to emphasizing that better distinctions should be made if we seriously want to develop a much finer sense (to use Cronin’s phrase) of what collaboration is and how to differentiate it from cognate but not identical phenomena.

2. Collaborate or perish

On May 12, 2022, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) Collaboration, a consortium that comprises several institutions and thousands of scientists around the world, announced that it had “unveiled the first image of the supermassive black hole at the center of our own Milky Way galaxy.”Footnote 6 This breakthrough came after years of attempts at looking more in depth into the structure of Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*, as the center of Milky Way is called) – most of all, it came after the EHT Collaboration’s first-ever release, in April 2019, of a sufficiently resolved image of a supermassive black hole (see figure 1), that of the center of the much more distant Messier 87 (M87) galaxy in the Virgo cluster.

Figure 1. Final imaging results showing the shadow of the black hole at the core of the M87 galaxy for each of the four observation days in April 2019 (from EHT Collaboration et al. 2019d, 21, fig. 15.) The shadow cast by the event horizon of the black hole, approximately 2.5 times larger than the event horizon itself, is the dim central region of the ring-like structure imaged.

In more technical terms, the EHT images of M87* and Sgr A* show the shadows that the event horizons associated with each supermassive black hole cast on their immediate surroundings. The event horizon of a black hole can be thought of as the boundary within which no information can escape from the black hole itself. Falcke, Melia, and Agol (Reference Falcke, Melia and Agol2000) predicted that a distant observer, under appropriate conditions and using a technique called Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) associated with (sub)millimeter radio astronomy, could detect the “dark shadow” cast by the event horizon because of the strong gravitational bending and capture of photons predicted by the theory of general relativity.

For these reasons, the EHT Collaboration’s achievements have been welcomed as a strong confirmation of general relativity on the one hand and as a success of international cooperation in the face of a remarkable technological challenge on the other. The present paper, however, aims neither at analyzing the scientific-theoretical underpinnings of the EHT endeavor in themselves nor at describing its social-technological conditions per se. Rather, while referring to both the scientific-theoretical and the social-technological sides of the problem, it asks whether there is a relationship between them and, if this is the case, what kind of relationship it is. In other words, it tries to answer the following question: assuming that the EHT is a genuine case of scientific collaboration, was the collaborative behavior just the effect of social premises, or was it produced by different, possibly non-social, factors? And what was the relative weight of such factors?

2.1. Resolving the resolution concern

These questions require a close examination of the techniques adopted and an explanation of the particular kind of collaboration involved compared with other types. Let us first recall some essential features of radio astronomy, which are also fundamental to the Event Horizon Telescope. As is well known, modern astronomy does not employ only optical devices, functioning at visible light frequencies. Based on their design, modern telescopes operate across the entire electromagnetic spectrum, from high-frequency gamma rays and X-rays through ultraviolet, visible, and infrared radiation, to the long-wavelength microwave and radio domains. Their optics may also be quite different depending on the kind of radiation they are designed for, and their shape may have no resemblance at all to common kinds of optical telescopes. Moreover, the colorful pictures of the cosmos now so familiar to us result from advanced image processing algorithms.

There are two large families of optical telescopes: the refractors, similar to the device employed by Galilei, where the light collecting region is an objective lens, and the reflectors (like most of the optical telescopes now in use, including the Hubble Space Telescope), where light is gathered by a concave primary mirror, then conveyed to the eyepiece or ocular lens; reflectors, in addition, can be very different in design. The radiation collecting area of a radio telescope – the concept on which the EHT is based – is neither a mirror nor a lens but, typically, a parabolic “dish” antenna.

However, no matter what kind of radiation a telescope should capture, and independent of its design, some basic features remain crucial. Every telescope, optical or not, functions by collecting and magnifying electromagnetic radiation. Though magnification can be very easily recognized as a fundamental property and certainly played an essential role in the success and prompt diffusion of telescopes in early modern astronomy, magnifying power and better vision are not synonymous. A telescope that greatly enlarges objects also enlarges distortions due to turbulence in the atmosphere and the features of the instrument.Footnote 7 Even with the best atmospheric conditions, an optical telescope with a magnifying power of more than fifty times its aperture – i.e., the diameter of the light collecting region – gives only fuzzy and dim images. If you want to distinguish the fine-grained structure of distant objects, for example the components of a star system like Alpha Centauri, what you need is a telescope with better resolving power, not just higher magnification.

Now, note that (angular) resolving power, or resolution, defined as “the degree to which the fine details in an image are separated and detected or seen” (Lang Reference Lang2006, 282), is directly proportional to the aperture of a telescope and inversely proportional to the observed wavelength. The bigger the aperture and the shorter the observed wavelength, the smaller the angle under which two close objects are seen, hence the higher the resolving power of the device. In more formal terms, and abstracting from the diffraction factor,

where θ is the angular resolution expressed in radians, λ is the wavelength, and D is the aperture of the instrument, both expressed in meters.

In rough terms, it follows that what is needed to ensure clear vision is a large telescope – or more precisely, an instrument with large aperture. But wavelengths matter as well: the range of visible light, as expressed in meters, is approximately 4 × 10 −7 < λ < 7 × 10 −7; therefore, optical telescopes with a good resolution may have a relatively small aperture, to the extent that they can easily be portable.Footnote 8 However, radio waves are characterized by a much larger interval, ranging from approximately one millimeter to several hundred meters. Thus, they are 103 to 107 times longer than visible light waves, and this makes the resolution of two closely separated radio sources in the sky much more difficult than for visible light, requiring devices with enormous apertures. This has caused resolving power to be a major concern of radio astronomy since its emergence in the 1930s. As reported by Kellermann and Moran (Reference Kellermann and Moran2001, 457), many techniques have been developed since the early postwar years, leading to startling improvements. Still, the resolution that could be achieved by conventional filled-aperture radio telescopes (i.e., telescopes provided with a single dish antenna, in the same way as a common optical telescope is equipped with a single lens or primary mirror) remained poor for decades. Moreover, structural as well as architectural problems pose limits to the resolving power as well as to the aims for which filled-aperture radio telescopes are used (Christiansen Reference Christiansen1963; Kellermann and Moran Reference Kellermann and Moran2001).

A way to circumvent these shortcomings and make available instruments with larger effective aperture has emerged from a technique called interferometry, consisting in the combination of signals from the same object to two (or more) separate telescopes. Stellar optical interferometry can be traced back to Michelson and Pease’s (Reference Michelson and Gladheim Pease1921) successful attempt to measure the angular size of Betelgeuse (a red giant in the constellation of Orion, also called α Orionis) by means of mirrors 20 feet apart (approximately six meters). The two different beams of starlight were then directed to the primary mirror of the telescope, which focused and combined them into a resulting pattern of interference. Comparing the separation between the mirrors with the interference fringes and using the resolution formula, Michelson and Pease were able to calculate the diameter of Betelgeuse, the first measurement of the angular size of a star other than the Sun.

Leaving aside many technical details, one important feature of this approach is that the (nominal) angular resolution of an interferometer practically equals the maximum separation of its components, assuming that they are adjusted to the same wavelength. Plus, in principle it can be applied to every frequency of the electromagnetic spectrum. Analogous radio interferometers were built immediately after World War II. Since then, the baseline – the distance between the constituent dish antennas – has grown from a few hundred meters up to many kilometers, greatly improving the resolving power and exploiting different designs for joining the antennas. Meanwhile, the goals of radio astronomers have changed, from initially counting cosmological radio sources to measuring the position and size of individual sources by using arrays of multiple antennas (Kellermann and Moran Reference Kellermann and Moran2001, 464–468).

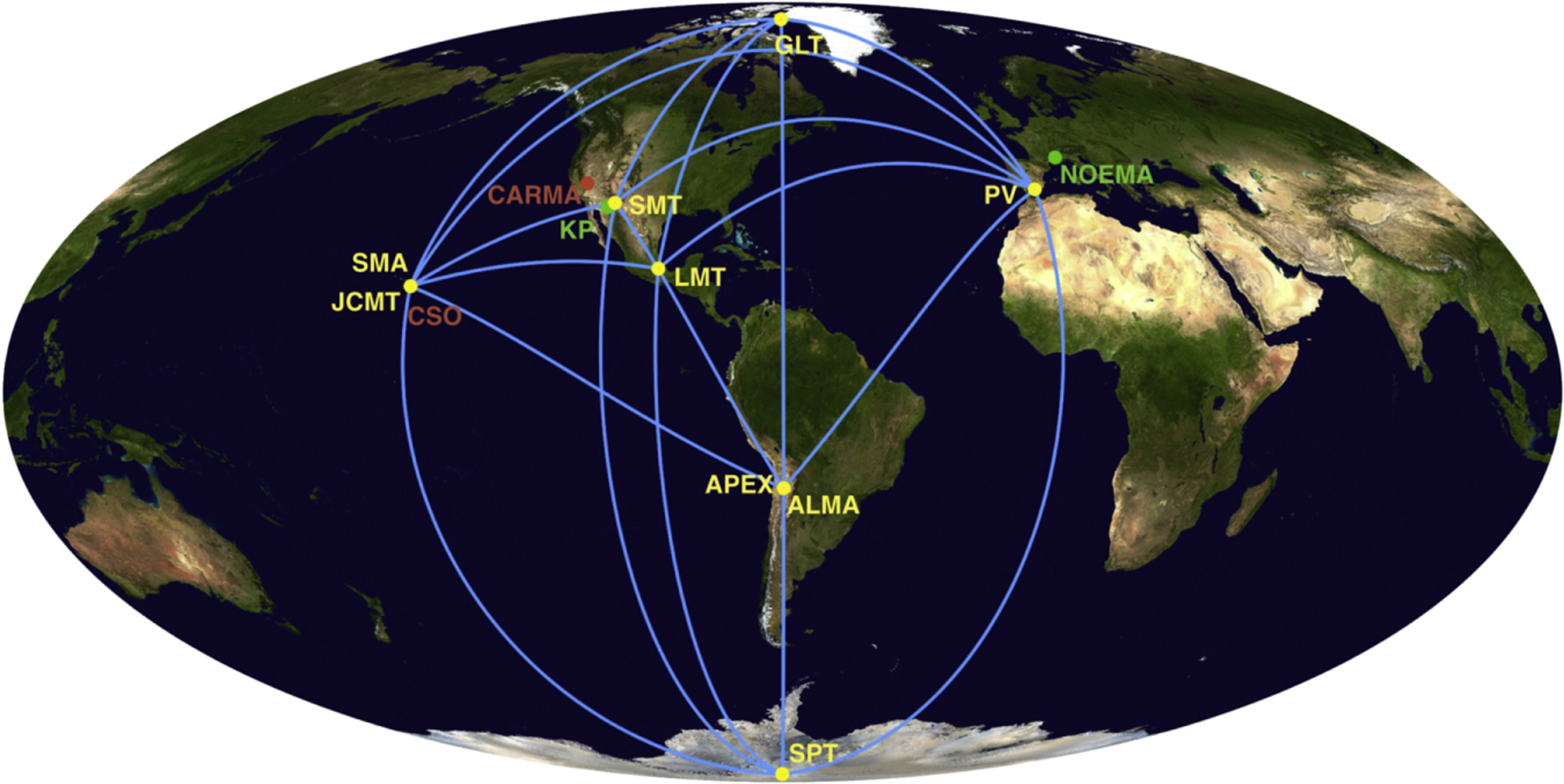

The technology employed by the Event Horizon Telescope to image a black hole shadow with appreciable resolution, both in the M87* and in the Sgr A* campaigns, is an application of interferometric techniques on a vast scale. It is called Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) and can be described as “the combination of radio signals recorded at widely separated radio telescopes observing the same cosmic object at the same time” (Lang Reference Lang2006, 339). Figure 2 shows the locations of EHT stations operating for the campaign that imaged M87*, to which the following analysis is mainly referred. This made of the EHT an Earth-sized interferometer, providing “a nominal angular resolution of

![]() $${\lambda \over D} \simeq 25$$

micro-arcseconds [i.e., 25 millionths of an arcsecond] in the 1.3 mm wavelength band” at which it operates (EHT Collaboration et al. 2019b, 5). Due to the enormous baseline lengths, data recording and storage have been crucial concerns, as well as the synchronization and calibration of antennas at intercontinental distances.Footnote

9

$${\lambda \over D} \simeq 25$$

micro-arcseconds [i.e., 25 millionths of an arcsecond] in the 1.3 mm wavelength band” at which it operates (EHT Collaboration et al. 2019b, 5). Due to the enormous baseline lengths, data recording and storage have been crucial concerns, as well as the synchronization and calibration of antennas at intercontinental distances.Footnote

9

Figure 2. Map of the EHT stations active in 2017 and 2018. Active sites are connected with lines. From EHT Collaboration et al. 2019b, 4.

The idea that it was feasible to image a real black hole rather than just simulate its appearance was a consequence of various achievements, both theoretical and observational. These include, in particular, the calculation of the photon orbit forming the bright ring around the event horizon and – following the seminal paper by Falcke, Melia, and Agol (Reference Falcke, Melia and Agol2000) – the expectation that “when surrounded by a transparent emission region, black holes … reveal a dark shadow caused by gravitational light bending and photon capture at the event horizon” (EHT Collaboration et al. 2019a, 1); the observation and growing understanding of the Active Galactic Nuclei and the general acceptance that they are powered by “supermassive black holes [SMBHs] accreting matter at very high rates through a geometrically thin, optically thick accretion disk” (ibid.); and observational evidence regarding SMBHs with the largest apparent event horizons, that is, the SMBH at Sgr A*, the center of our own galaxy, imaged in 2022, and the central SMBH of M87 in the Virgo Cluster.Footnote 10

The instrumentation itself relied on decades of intertwined scientific and technological advances. The label “Event Horizon Telescope” made its first appearance in the abstract of a 2002 conference paper, published the subsequent year (Miyoshi, Kameno, and Falcke Reference Miyoshi, Kameno and Falcke2003).Footnote 11 However, global VLBI was envisaged as early as in the 1970s (e.g., Penzias and Burrus Reference Penzias and Burrus1973, esp. 52–53) after a decade or so of VLBI observations (Kellermann and Moran Reference Kellermann and Moran2001, 476–481). The telescope was then developed as “a global ad hoc VLBI array operating at 1.3 mm wavelength” (EHT Collaboration et al. 2019d, 1). It was the result of previous technological successes (as reported in EHT Collaboration et al. 2019b, esp. 3–5), such as the extension of the VLBI technique to very short wavelengths and the treatment of noise under such conditions (EHT Collaboration et al. 2019b, 3–4), but had also to face new challenges in data processing, calibration, and imaging that required the development of specialized techniques (EHT Collaboration et al. 2019c). Substantial improvements are expected from the “next-generation Event Horizon Telescope” program (ngEHT), launched in September 2019 and “aimed at solving the formidable technical and algorithmic challenges required to significantly expand the capability of the EHT.”Footnote 12

The final imaging results of April 2019 shown in figure 1 were the effect of a complex of operations. The EHT-VLBI technique required that the individual stations displayed in figure 2 observed and recorded independently, and at exactly the same time, signals coming from the same source, in order that its brightness distribution could be reconstructed. A common time reference was initially provided by local atomic clocks paired with GPS. Data were then brought to a central location where they were combined (“cross-correlated”) and calibrated for residual clock and phase errors. Finally, further analysis was developed from the EHT so-called “calibrated visibilities” through simulations, modeling, and imaging algorithms.

2.2. If collaboration, why collaboration?

Every stage in this process required some form of collaboration for different reasons, and from its establishment the EHT project has comprised several working groups. Collaborative work took a variety of forms, ranging from the interdisciplinary division of labor because of the several specialties involved, to coordination tasks in order to render uniform procedures of data storage and sharing in the correlation and calibration phase, to the subdivision of a single working group into separate teams to cross-check results and avoid biases and errors in the imaging phase.Footnote 13

Leaving aside the question of how researchers collaborated within the working groups and teams, in most of these cases the collaborative approach can be viewed, following Kitcher’s (Reference Kitcher1995) model for cooperative behavior, as an optimal answer to a problem of resource optimization. For the sake of simplicity, let us first conceive the researchers as “pure epistemic agents,” i.e., agents whose primary aims are limited to the attainment of an “epistemically valuable state” – essentially, the growth of knowledge about some state of affairs – without taking into account other factors that may influence their propensity toward collaboration, such as, e.g., personal inclinations, economic interests, the search for prestige, and recognition by peers. Those researchers typically operate with a finite amount of resources – such as time, funding, and personal skills – in their pursuit of knowledge, whose attainment carries certain costs. In Kitcher’s economically fashioned framework, this condition can be represented as an inequality:

where E represents energy resources (time, funds, personal skills, etc.), k denotes an amount of knowledge (defined as “items of information”) that can be acquired either individually or in collaboration, each with different costs. C represents the cost of acquiring knowledge individually, while c represents the cost when done collaboratively. This abstract model can be further refined by differentiating between “pure” agents (driven primarily by a pursuit of truth) and epistemically “sullied” agents, who may be influenced by personal interests, such as the Mertonian ambition for priority and the related desire for prestige and career advancement (ibid., 310). Yet even in these more nuanced circumstances, collaborative research becomes favorable when individual resource demands exceed the collective resources required to achieve the same goals. As research becomes increasingly complex and specialized, it is more efficient for participants to rely on one another’s expertise, as well as on shared material and social resources, rather than to proceed independently.

The model is designed less to describe the specific mechanisms of collaboration than to explain why scientists might choose collaboration over solitary work. It suggests that scientists are primarily motivated by resource optimization, grounded on two assumptions. First, it assumes that, in principle, researchers rationally expect the same results might be achieved individually, depending on costs, given limited resources. Second, knowledge is treated quantitatively, whether as an aggregate of “items of information” or as a cognitive goal that is either achieved or not, while factors like research questions, field specificity, or methodology are not considered influential in promoting or hindering collaboration. However, there are cases in which these assumptions may not adequately capture the complexities of collaborative research – where the epistemic structure of a problem can significantly shape the social framework in which the problem is developed and its solution is pursued. One example, I argue, is the development of the Event Horizon Telescope.

As Falcke (Reference Falcke2017) explains, after the discovery of quasars and Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) – compact and very bright regions at the center of certain galaxies, whose luminosity is theorized to be powered by a central supermassive black hole – the astrophysical community began to search for reliable models for black hole appearances. Back in the 1970s, “because of their large distances, imaging a black hole on scales of the event horizon seemed out of reach” (ibid., 2). At a certain point, however, some hope seemed to come from observations of our Galactic Center, Sgr A*, which “was often compared to radio cores in AGN, and hence considered to mark the supermassive black hole in our Milky Way” (ibid., 3).Footnote 14

Lynden-Bell and Rees already predicted that a radio interferometer with a very long baseline – e.g., a continental radio interferometer – could “determine the size of any central black hole that there may be in our galaxy” (Reference Lynden-Bell and Rees1971, 474). Falcke, Melia, and Agol (Reference Falcke, Melia and Agol2000) made a crucial step further with respect to its potential imaging. As mentioned above, studying the pattern of emission of Sgr A*, they elaborated the concept of the shadow of the event horizon of a black hole. The diameter of the shadow of the supermassive black hole at the Galactic Center Sgr A* was calculated to be of the order of

63 million km for M• = 4.3×106M⊙, corresponding to 51 microarcseconds (μas) for a distance of 8.3 kpc [kiloparsec] to the Galactic Center. The resolution of a radio interferometer is given by the ratio of observing wavelength and telescope separation λ/D. For global interferometers D reaches typical values of 15,000 to 6,000 km, giving one a resolution between 18 to 50 μas at 230 GHz (i.e., λ1.3mm) – just large enough to start resolving the shadow. Moreover, the scattering effect decreases with λ2, also approaching 22 μas at λ = 1.3 mm. Hence, 230 GHz becomes a “magical” observing frequency, where interstellar scattering, optical depth in the source, global VLBI resolution, and atmospheric transmission make this experiment just possible. At higher frequencies the earth’s atmosphere becomes too hostile and at lower frequencies the source is scatter broadened and intransparent. Hence, we can thank God, that the earth is just large enough and at the right location in our Galaxy, to let us to not only see the light, but also the shadow of a black hole. (Falcke Reference Falcke2017, 4)

For many different reasons, and to the dismay of the researchers involved, Sgr A* proved to be a more challenging candidate than expected, and a substitute was found in the by far more distant, but much larger, M87*. But in both cases the models indicated that global VLBI at 230 GHz (or λ = 1.3 mm) was needed to produce images with reliable resolution – that is, an interferometric technique consisting in the creation of a single virtual (radio) telescope by connecting individual stations, whose baseline is comparable to the size of the Earth. This renders necessary a highly collaborative scheme, where every station needs to share information and be synchronized with other stations, located all over the Earth’s surface, in order that we can obtain an Earth-sized aperture sufficient to resolve it.

In other words, here collaboration is required because of the features of the object investigated and our mode of investigation. Because of the combination of several circumstances – the relative position of the Earth in the Universe, the distance and size of “observable” black holes due to the brightness of their surroundings, the employment of radio frequencies, the notion of angular resolution as given by λ/D and the notion that D of a radio interferometer equals the station separation, etc. – the imaging of (the shadow of) a black hole like that at Sgr A* or M87* is only possible via global VLBI. If our goal is imaging those large but remote objects, the limit to any individual strategy is not dictated by a somewhat socio-economic constraint as in the case of the division of labor and resource optimization. Rather, it results from some “epistemic constraint,” some kind of limitation to our knowledge capabilities which depends on how we intend to know what we intend to know. It is the epistemic problem of imaging a black hole that requires a collaborative structure in order that that problem can be solved; in turn, the collaborative structure of the EHT, and its VLBI-based design, is the response to this epistemic problem.

3. The case for epistemic constraints

From the previous section it emerges that individual approaches to the observation and imaging of a black hole have not been taken into consideration because astrophysicists were aware that they were not feasible for theoretical reasons. A collaborative approach was not demanded, in the first place, by a socio-economic constraint like the division of labor or resource optimization. Rather, it results from what I call an “epistemic constraint,” some kind of limitation to our knowledge capabilities, which is encapsulated in our theories – in the case at hand, in the equation controlling the angular resolution.

With phrases like “epistemic constraints” and “epistemically constrained” – an attribute that I use here with reference to collaborative research – I do not intend to highlight the role of cognitive resources (categories, concepts, etc.) in doing science, which would be trivial; rather, I mean to address any component of the world – no matter whether dependent on the external world or integral to our cognition – that prevents us from gaining some definite kind of knowledge in a specific manner and allows some other specific kind of knowledge in definite ways.

The language of constraints in the history and philosophy of science has been adopted and defended by Galison (Reference Galison1987, Reference Galison1988, Reference Galison and Jed1995) but famously challenged by Pickering (Reference Pickering and Jed1995).Footnote 15 Pickering contends that although Galison’s (Reference Galison1987, 257) definition of constraint as referring to “obstacles that while restrictive are not absolutely rigid” is poorly elaborated, it still fosters an incorrect perspective on “the nature of cultural practice” (Pickering Reference Pickering and Jed1995, 47). Since constraints are said to set some sort of limitations to practice, no matter how flexible, in his opinion this language “encourages us to inspect cultural elements for some property that limits practice; … it encourages us to think that this property is already and enduringly there in the elements in question” (ibid.).

Here I try to elaborate the notion of (epistemic) constraint further to answer these objections. I hope that the following remarks can help revitalize a concept which, I think, should find a place in the toolbox of both historians and philosophers of science. It can enhance our picture of how knowledge changes and help us to understand why, and under what circumstances, we adopt some practices or approaches or ideas instead of others.

The concept of epistemic constraint, as I am utilizing it, is modeled after the notion of constraint in physics. Usually, in mechanics a constraint is something that limits the motions a system can perform. Particles forming a rigid body are constrained to keep their mutual distances unchanged in every motion of the rigid body itself. Other popular examples of constraints from physics handbooks typically include the beads of an abacus, which are constrained by the supporting wires to one dimensional motion; a particle on the surface of a sphere, which is constrained to move in two dimensions only on that surface; gas molecules within a vessel, which are constrained by its walls to three-dimensional motion only inside the container, etc. These examples convey the idea that constraints pose restrictions on the freedom of motion of a particle or a system of particles. By doing this, they also leave room for possible motions. Thus, a constraint is also positively characterized by the motions it allows, not only by those it prevents.

Other, but in a certain sense similar, metaphors are possible. Galison (Reference Galison1987, 246) traces back the use of the concept of constraint in history to Braudel’s work on Mediterranean civilization. Writing on methodology, Braudel ([1958] Reference Braudel1980, 31) noted that, to a certain extent, the study of the longue durée is the study of the effects of long-lasting structures on the lives of certain groups. In turn, structures are states of affairs, such as “certain geographical frameworks, certain biological realities, certain limits of productivity, even particular spiritual constraints [contraintes],” that are difficult to dispense with. In particular, “some structures, because of their long life, become stable elements for an infinite number of generations … Others wear themselves out more quickly. But all of them provide both support and hindrance [soutiens et obstacles]. As hindrances they stand as limits (‘envelopes’ in the mathematical sense) beyond which man and his experiences cannot go.”

The mathematical notion of envelope may sound too complicated to be used as a metaphor in this context, but it seems to me that it embodies the double sense of hindrance and support, and most of all support-by-hindrance, that is expressed in my physical metaphor. In (planar) geometry, a family of curves “envelopes” a certain curve C if every member of the family is tangent to C (or, the envelope of a planar family of curves is a curve tangent to each member of the family). Let us think of a family of circles on a Cartesian plane described by certain common parameters, for example, having their centers along the same straight line defined by the equation y = x and all of the same size. Their envelope will be the two straight lines tangent to every one of such circles. In a certain sense, the envelope selects all curves with certain characteristics (circles with certain parameters, in this case) by excluding all other alternatives that do not possess those characteristics.

Like envelopes, Braudel’s “structures” draw spaces of possibilities while ruling out alternatives. So, for example:

For centuries, man has been a prisoner of climate, of vegetation, of the animal population, of a particular agriculture, of a whole slowly established balance from which he cannot escape without the risk of everything’s being upset. Look at the position held by the movement of flocks in the lives of mountain people, the permanence of certain sectors of maritime life, rooted in the favorable conditions wrought by particular coastal configurations, look at the way the sites of cities endure, the persistence of routes and trade, and all the amazing fixity of the geographical setting of civilizations. (ibid.)

Likewise, epistemic constraints draw a space of possible dispositions to do something (where doing also includes that peculiar form of action that is thinking) while forbidding other dispositions. An argument drawn from Ludwik Fleck’s seminal Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact can illustrate this concept (original German: Fleck [1935] Reference Fleck2012, esp. 130–132; English translation: Fleck Reference Fleck1979, 99–101). Here, he famously identifies several distinct and largely independent threads linked to specific “thought collectives,” whose interactions culminated in the modern understanding of syphilis. For Fleck, this exemplifies a broader process in the history of knowledge, not limited to scientific knowledge. He argues that “such ideational developments form multiple ties with one another and are always related to the entire fund of knowledge of the thought collective.” Such internal connections, Fleck suggests, are sometimes implicit and tightly bound. He refers to them as “passive linkages” and emphasizes their “compulsory” character in selecting the permissible relationships, even beyond the realm of science. In literature, “a web of fantasy spun for long enough always produces inevitable, ‘spontaneous’ [zwangsläufig ‘von selbst’ sich ergebenden] substantive and formal connections. In a romance about chivalry … one cannot simply write ‘horse’ instead of ‘steed’ although these words are logically synonyms.” In music, given certain conventions about notation and values of rhythm and notes, “there are compulsory linkages [zwangsweise Koppelungen] in musical imagination [Phantasie] too, which correspond to the example: ‘Assuming O = 16, then H = 1.008.’” In the visual arts, “an artistic painting also exhibits its own constraining style [Zwang eigenen styles]. This we can easily demonstrate by placing part of a second painting over a good painting executed in a definite style. The two parts would clash with each other, even if the two paintings were matched in content.” So, Fleck concludes: “Every product of intellectual creation contains relations ‘which cannot exist in any other way [die gar nicht anders sein können].’ They correspond to the compulsory, passive linkages [zwangweise, passive Koppelungen] in scientific principles.”

With this, Fleck underscores the social nature of knowledge development: “passive linkages” are tied to a particular style, which in turn is linked to a specific collective. Different collectives may have different styles, and crucially, “because it belongs to a community, the thought style of the collective undergoes a kind of social reinforcement that characterizes all social structures.” However, Fleck also accounts for structural features of (scientific) knowledge that may be relatively independent of the social relations in which they arise (see also Cohen and Schnelle Reference Cohen and Schnelle1986, xii–xiii and xxx). The somewhat opaque musical example quoted above is especially revealing in this regard. In the twelve-tone equal temperament, an octave (Oktave, denoted by “O” in the quoted passage) is subdivided into twelve semitones (Halbtonen, “H”), and so it follows that each semitone has an interval ratio of

![]() $$\root {12} \of 2 \approx 1.06$$

. Fleck imagines applying some Phantasie to divide the octave into sixteen semitones. In an equal temperament system, this would yield an interval ratio of

$$\root {12} \of 2 \approx 1.06$$

. Fleck imagines applying some Phantasie to divide the octave into sixteen semitones. In an equal temperament system, this would yield an interval ratio of

![]() $\sqrt[{16}]{2} \approx 1.04$

for each semitone. It is hard to guess why Fleck gives the value 1.008 – perhaps due to a manual calculation error, an intuitive approximation, a possible variation in temperament choice, or he just extrapolated the value from some textbook of musical theory.Footnote

16

Nonetheless, the logic behind his argument is clear: Adopting an unconventional musical structure, such as an octave with sixteen semitones, would inevitably impose its own constraints, influencing compositional techniques, for instance.

$\sqrt[{16}]{2} \approx 1.04$

for each semitone. It is hard to guess why Fleck gives the value 1.008 – perhaps due to a manual calculation error, an intuitive approximation, a possible variation in temperament choice, or he just extrapolated the value from some textbook of musical theory.Footnote

16

Nonetheless, the logic behind his argument is clear: Adopting an unconventional musical structure, such as an octave with sixteen semitones, would inevitably impose its own constraints, influencing compositional techniques, for instance.

A similar argument applies to the conditions mentioned by the end of section 2.2. The resolution equation, for example, may have been developed through socially constrained processes. We can even view it as one possible – though not necessarily the only – way to represent certain physical relations. Social, economic, and cultural factors may have shaped our efforts to observe the sky using telescopes at various wavelengths. However, when we apply the resolution equation to determine a telescope’s aperture, the resulting implications stem from the equation itself rather than from the social conditions under which it was formulated. As I have demonstrated, one such implication is that if we aim to capture an image of a peculiar object like a black hole, we have to proceed collaboratively. In Fleck’s terms, a “compulsory, passive linkage” emerges here, one that rules out individual inquiry and demands a collaborative approach, regardless of the social forces that initially shaped the equation’s development.

With this insistence on somewhat structural features of theories or, more in general, of the scientific practice, am I not reactivating the old distinction between factors internal to the scientific inquiry, obeying some “rational,” non-temporal criterion, and external factors, which matter to historians, sociologists, etc.? Quite the contrary, I think that the argument presented above has a non-reductionist import. While we can acknowledge, with Fleck, that cognition is socially situated, the internal constraints of scientific principles – like the resolution equation – operate independently of these social factors. In other words, once they have been established, these principles are not malleable or entirely reducible to social dynamics.

So, I am not disputing that constraints coming from the social, political, or economic domains, for example, play an important role in the complicated, multifaceted story of my case study – as in practically any other project involving international cooperation and requiring substantial funding. The Event Horizon Telescope enterprise would hardly have been possible had not several institutions from many countries agreed how to share responsibilities, funding, and possibly honors while taking part in the project. However, these efforts could only be initiated because of theoretical requirements independent of, and prior to, social, political, and economic constraints. Of course, we also need funds, instruments, scientists, training, etc., to perform any research in science. Still, these requirements are not special to collaboration: We would need them in some form, even if we could adopt an individual mode of investigation. However, no individual mode is possible if we want to image the shadow, say, of M87’s central black hole. In this sense, the collaborative approach characterizing the EHT is, to a large extent, a consequence of an epistemic constraint.

Finally, speaking of epistemic constraints, I am not intimating that they have a special essence. Rather, I want to emphasize their function. Epistemic constraints cannot be defined absolutely but only with respect to the role they play in the context in which they emerge. Different epistemic functions generally result in constraints of different kinds or for different purposes, and something can cease to be an epistemic constraint if the conditions are changed. In the case of the black hole imaging through the EHT, both its VLBI-based design and millimeter radio astronomy can equally be viewed as part of an epistemic constraint in order to obtain the image. Expressing the epistemic constraint in terms of impossibilities or, following Braudel and Galison, as “obstacles,” we should say that in the case of the black hole imaging, the epistemic constraint is given by the impossibility – due to our relative position with respect to M87* and Sgr A* – to get a sufficiently resolved image with a single-aperture telescope observing at a given wavelength. This impossibility draws a space of possible action – namely, VLBI. On the other hand, millimeter radio telescopes were required mainly because the environments of those giants are opaque to other frequencies. However, I argue, only the impossibility resulting in VLBI represents an epistemic constraint for collaborative research, whereas millimeter radio astronomy is neutral toward collaboration.

Here we come to a somewhat different aspect that is worth noticing, since it can give an answer to Pickering’s objection to the idea that constraints are already present and enduring in the elements in question. The case of the EHT itself indirectly suggests that epistemic constraints can cease to be such if the conditions that have elicited them are changed. This is reflected in Falcke’s assertion reported above that “we can thank God, that the earth is just large enough and at the right location in our Galaxy, to let us to not only see the light, but also the shadow of a black hole” (2017, 4). Let us reverse the argument: If we, the observers, were nearer to a black hole, then we would not need VLBI, and each individual could experience a fine-grained image of it, just as the astronauts in the movie Interstellar orbit around the very massive black hole Gargantua and see its event horizon (or its shadow) along with the amazingly bright accretion disk. Similarly, if we were able to build a single radio telescope with sufficient aperture to get an image with good resolution, again we would dispense with VLBI and, in principle, get rid of the need for collaboration. So, in a certain sense the constraints are “already there”: They are “passive linkages” that do not entirely depend on us. But we can manage with them in ways that cannot be anticipated because they depend on many contingent conditions. And whereas I think that “cultural elements” in Pickering’s sense set limits to – pose obstacles to, or constrain – practice, I am also convinced that no constraints necessarily last forever (under any possible condition).

4. Desire and necessity

Well before the EHT network was operating, Kellermann and Moran argued that global VLBI collaborations involving an international network of large research facilities “were accomplished without any formal government involvement … [They] were established because the science required them – in the form of longer baselines and multiple antennas – and not to save money, enhance national prestige, or promote political goals” (2001, 490). This judgment may appear exaggerated and hasty. It is a matter of empirical research to find out which constraints were at play in establishing the Event Horizon Telescope (or other enterprises of a similar kind) and how they interact with one another.

As I have mentioned, the EHT included several kinds of collaborative approaches at many stages of research. Money saving, enhancement of national prestige, and the promotion of political goals were not at the center of the present study; but this does not mean that they did not play a role. In fact, they did. Of course, there was practically no direct, formal involvement of governments in the financial support of the EHT. However, this commonly happens in many large scientific projects and may indicate that a mediation operates at some level. Usually, governments grant their support to central agencies which in turn assign funds to research teams, institutions, consortia, etc. Moreover, participant institutes, centers, or groups often allocate (or are asked for) extra funding for the projects in which they are involved.

In the end, the whole design of the Event Horizon Telescope was a result of many constraints of different kinds that were at play and became entangled with one another at some stage: theoretical breakthroughs in different domains, advances in engineering and computational methods, money-saving, and competition among teams and (national) communities. A network of preexisting international cooperation programs, complicated financial and administrative plans, and appropriate infrastructures were necessary to its development, and national prestige may also have played a role.Footnote 17 Nevertheless, I think that there is one sense in which Kellerman and Moran have a point in claiming that collaborations of this kind are mostly established “because the science required [them].” It is because we need global VLBI and eventually an Earth-sized aperture to image a black hole shadow that we can exploit preexisting cooperation agreements and infrastructures, put forward financial plans, formulate a project with its hierarchical organization, take advantage of available technologies or develop new ones, fine-tune strategies to gain international support, and improve collaborative schemes. Without such an epistemic necessity, encapsulated in pioneering theoretical papers on global VLBI such as those by Falcke, Melia, and Agol (Reference Falcke, Melia and Agol2000) and Miyoshi, Kameno, and Falcke (Reference Miyoshi, Kameno and Falcke2003), none of these preconditions would probably have started operating in the context of a collaborative effort. Therefore, such an epistemic necessity – our epistemic constraint – prevails over other possible constraints with regard to the collaborative nature of the EHT project.

In conclusion, the case study of the EHT, as I have developed it in the previous sections, provides sufficient evidence for epistemically constrained collaboration at least in the realm of astronomy and astrophysics. In that case, astronomers and astrophysicists collaborate, in the first place, because the science involved requires it, because an epistemic constraint is at work. Because otherwise they cannot reach their goal. Still, in astrophysics there are also kinds of research in which epistemic constraints with regard to collaboration do not prevail, and the propensity to cooperate might be mainly due to the division of labor. Let us consider the development of millimeter radio astronomy, a sub-discipline that emerged in the early 1960s, initially with the purpose of studying the atmosphere. The application of these techniques to more conventional astronomic purposes led to the development of reflector antennas capable of observing in the millimeter-wavelength regime and, of course, posed noticeable challenges to structural engineers and manufacturing contractors. In turn, significant achievements in millimeter-wavelength research – e.g., the observation of recombination lines of interstellar molecules and of processes associated with star formation as well as with the microwave background radiation – have encouraged astronomers and engineers to push the limit further, opening up the sub-millimeter wavelengths range in the 1980s (Baars and Kärcher Reference Baars and Jürgen Kärcher2017; Penzias and Burrus Reference Penzias and Burrus1973, 51–54). Of course, behind each telescope of whatever kind there are numerous teams of astronomers, and every team is made up of several researchers with many different sorts of expertise. Clearly, this circumstance is mostly due to the division of scientific labor and the optimal allocation of resources.

However, the context of millimeter and sub-millimeter astronomy does not include a feature that the context of VLBI and the EHT does. Such a feature can be labeled, paraphrasing Kellermann and Moran (Reference Kellermann and Moran2001), “When science requires it”, meaning “When knowledge contents or the specific features of the researched objects, and the methods of investigation applied in order to gain a certain piece of knowledge, require a collaborative approach, without which that goal cannot be accomplished at all.” This seems to me a general feature, which is not special to examples like VLBI or the EHT network. It might be integral to diverse fields and disciplines, and more common in some of them than in others, depending on specific requirements.

Daston has argued for the importance of what she calls “the science of the archive” — a kind of inquiry comprising several distinct fields, such as astronomy, geology, demography, meteorology, but also botany and zoology, in which investigations often crucially depend on the storage, preservation, and consultation of past observations (Daston Reference Daston2012). According to Daston, nearly every generation of savants in these fields recognized that their own successes – and those of future generations – depended on the preservation of archived observational records. This shared sense of contributing to a common endeavor makes these scientists “collaborators” in their own right, even if they had no direct interactions in space and time.Footnote 18 While I would, as mentioned, reserve this term for symmetrical relationships, I believe Daston (Reference Daston2012; see also Daston Reference Daston2023) touches on an essential point here. The social relationship that binds researchers, whether we call it a “collective” or a “collaborative” enterprise, is contingent upon certain epistemic requirements or constraints. Scientists may act collaboratively (collectively) because of how they conceive the goals, objects, and methods of their inquiry. Other motivations to collaborate (to act collectively) may also be present, but those goals can only be achieved if they collaborate (act collectively).

Therefore, epistemically constrained collaboration should not be regarded as unique to modern science. It might also have been widespread in the past depending on internal requirements of the field under consideration. Examples in which epistemic constraints could play a substantial role may include Daston’s “science of the archive” as well as the disciplines mostly practiced at the observatories, and thus belonging to the “observatory sciences” (Aubin, Bigg, and Sibum Reference Aubin, Bigg and Otto Sibum2010; see also Feldman Reference Feldman, Tore Frängsmyr and Rider1990), like astronomy, cartography, geodesy, geomagnetism, and meteorology.

The case of geomagnetism is particularly insightful in this regard. When presenting the findings of the Göttinger magnetischer Verein, Carl Friedrich Gauss noted that “the variations [of the geomagnetic force] happen with regularity, a rigorously organized cooperation [ein streng geordnetes Zusammenwirken] of the observers at different places, although … desirable, is fundamentally not necessary [nicht wesentlich notwendig], and each observer can provide useful contributions even independently of the others.” However, observations made since the late eighteenth century had given convincing evidence about the importance of the “irregularity in the expressions of geomagnetism”. To investigate further into this field and try to understand the causes of the variation in geomagnetic activity, Gauss continued, “many phenomena of this kind must simultaneously be followed with accuracy at many places and exactly measured according to time and size. But to this end determined preliminary agreements [Verabredungen] among these observers … are fundamentally necessary [wesentlich notwendig]” (Gauss Reference Gauss, Gauss and Weber1837, 3–5). As shown by Cawood (Reference Cawood1977, Reference Cawood1979) and Clark (Reference Clark2007), on the one hand the collaborative ethos in geomagnetic research was certainly supported by various material and social factors, including advancements in transportation and communication, scientific instruments, funding institutions, and coordination efforts. On the other hand, the will to collaborate was cemented by the sense of necessity embedded in Gauss’ words.Footnote 19

A common feature of these examples is that the collaborating stations or researchers are geographically dispersed – a characteristic shared by many modern astrophysical projects, including the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) and the twenty-first-century quest for gravitational waves, which also relies on an interferometric framework. However, spatial separation is only one aspect of a broader, essential principle: the collaborating stations or researchers must depend on others to access information otherwise beyond their reach. This captures the essence of my attempted paraphrase of Kellerman and Moran’s adagio, “When science requires it”. Spatial separation makes the necessity of relying on others more evident, yet epistemically constrained collaboration frequently involves not only physical distance but also the complementary use of distinct methodologies, assumptions, technologies, and scientific cultures.Footnote 20

5. The way ahead

I do not aim to explore other potential instances of epistemically constrained scientific collaboration here; each would require a detailed examination beyond the scope of this article. However, in concluding this study, I believe that the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) case, alongside the examples referenced in the previous section, underscores an important methodological point. In section 3, I highlighted Fleck’s view that “thought style” imposes structural constraints on conceptual developments that may function somewhat independently of social relations. While I agree with Fleck, I advocate for an even more radical perspective (sections 2.2 and 4): The EHT project and possibly other historical cases suggest that the epistemic structure of an inquiry can significantly shape the social framework within which it unfolds.

This perspective contrasts with some contemporary approaches in socially oriented studies in the history and philosophy of science, particularly those that, by adding the adjective “social” to a certain phenomenon, intend to “designate a stabilized state of affairs, a bundle of ties that, later, may be mobilized to account for some other phenomenon” (Latour Reference Latour2007, 1). Contrary to Latour, I question whether this project has even been productive in the past. Rather – though this cannot be fully addressed here – I suspect that, especially in connection with the social turn in the history and philosophy of science, it has reinforced precisely the static notion of the “social” that Latour seeks to deconstruct. Indeed, it has perpetuated “any superfluous assumption about the nature” of the social, as if it were endowed with an independent existence governed by “social forces”. As a result, social behaviors, like collaboration, are often solely attributed to forces such as economic pressures, political interests, or prestige-seeking, etc., while scientific factors are downplayed or excluded as explanatory elements.

This does not imply, of course, that social behaviors are not social constructions. In a sense, this should be self-evident; adding “social” to “construction” in such contexts is, as Hacking (Reference Hacking1999, 39–40) argued, redundant. But this is only part of the story. And here is where I do agree with Latour: in the need to move beyond a “sociology of the social”, and in the advocacy for a broader, bolder perspective, one that views social aggregates as “associations … made of ties which are themselves non-social” (Latour Reference Latour2007, 8). Consistent with this view, my argument on epistemically constrained collaboration demonstrates that there are cases where social behaviors are directed by epistemic requirements – where epistemic factors are part of the explanans, not merely explananda.

Considering this, one can legitimately speculate that our current conceptions about the social structures of science should be enriched with some novel points of view on epistemically driven structures of sociality.

Acknowledgments

Concepts explored in this paper were discussed in seminars organized by Vincenzo Fano and Pierluigi Graziani at the University of Urbino, as well as by Pietro Omodeo and the “Early Modern Cosmology” research team in Venice. I am sincerely thankful for these enriching opportunities. I am deeply grateful to my colleagues from the “Project Seed 2019 – Reassessing Scientific Collaboration” team at the University of Milan – Leonardo Gariboldi, Andrea Guardo, and Massimo Lazzaroni – for their valuable advice and the productive exchange of ideas. My thanks extend to Stefano Furlan, Rocco Gaudenzi, Marco Giammarchi, Niccolò Guicciardini, Roberto Lalli, Chiara Lisciandra, and Eugenio Petrovich, who read early drafts of this article and provided valuable feedback. I also owe a debt of gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their stimulating criticism, and to Anna Echterhölter and Moritz Epple for encouraging me to refine the notion of epistemic constraint by, respectively, reconsidering it in light of Ludwik Fleck’s insights and by engaging with the Galison–Pickering debate. This research was funded by the Department of Philosophy “Piero Martinetti” of the University of Milan under the Project “Departments of Excellence 2023–2027” awarded by the Ministry of University and Research (MUR). It has also been supported by “Project Seed 2019 – Reassessing Scientific Collaboration” of the University of Milan.

Declaration of interest statement

I certify that there is no actual or potential conflict of interest, nor are there competing interests, in relation to this article.

Luca Guzzardi is associate professor of Philosophy of Science in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Milan “La Statale.” His recent work explores the history and epistemology of collaborative practices in science.