Introduction

In Southern Europe, the years that followed the outbreak of the Eurozone crisis have seen substantial changes in economic conditions and the regulation of labour markets (Armingeon & Baccaro Reference Armingeon and Baccaro2012a, Reference Armingeon, Baccaro, Pontusson and Bermeob; Zartaloudis Reference Zartaloudis2014; Picot & Tassinari Reference Picot and Tassinari2017). In Spain, Italy, Portugal and Greece, the crisis resulted in a massive increase in unemployment and a quick deterioration of public budgets that triggered wide‐ranging measures of cost‐containment. In a system of fixed exchange rates, internal devaluation (the decrease in domestic prices and wages) was perceived as the only available adjustment strategy to regain competitiveness. As part of this strategy, structural reforms of labour market regulation have featured high on the agenda of all these countries. The rigidity of their labour markets was understood to be a major cause of their economic woes, and a severe hindrance to wage adjustment (ECB 2012).

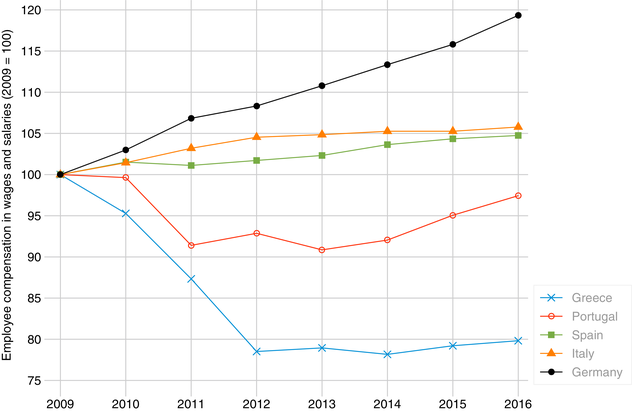

Looking at these reforms comparatively, the extent of labour market adjustments has been impressive, even if substantial differences persist. If we take employee compensation in wages and salaries as an indicator, between 2009 and 2013 these declined by 21 per cent in Greece and 9 per cent in Portugal. They increased by only 2 per cent in Spain, and by 5 per cent in Italy. The Eurozone as a whole saw a 7 per cent increase. Meanwhile, wages and salaries in Germany increased by 11 per cent (Figure 1). Between 2009 and 2014, the share of Greek workers covered by collective agreements spectacularly collapsed from 85 per cent to an estimated 10 per cent (ILO 2016: 70). In Portugal, the total number of workers covered by collective bargaining fell by 562,000 (about 20 per cent) between 2008 and 2013 (Addison et al. Reference Addison, Portugal and Vilares2016: 18), and all countries substantially reduced their level of employment protection. The extent of these changes is puzzling if one considers previous assessments of the Southern European labour markets as being sclerotic and difficult to reform, the previously limited impact of EU conditionality in the region (Blavoukos & Pagoulatos Reference Blavoukos and Pagoulatos2008) and the extensive role of the state in these economies (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2002). Extensive state intervention in European labour markets has often been seen as a source of rigidity, making wages unresponsive to economic pressures, and leading to adjustments in quantity (employment) rather than levels (wages) (Blau & Kahn Reference Blau and Kahn2002: 3–5).

Figure 1. Employee compensation in wages and salaries in Southern Europe and Germany (100 = 2009).

Source: Eurostat. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

This article focuses on the policy instruments used to achieve these outcomes. It shows that the extent of regulation by the state (as opposed to regulation by social partners) can be a facilitator, rather than a barrier, to internal wage devaluation. Indeed, extensive state regulation in the labour market (minimum wages, extension mechanisms of collective bargaining, employment protection) provides powerful levers for governments to achieve devaluation, while weak state regulation and a high degree of self‐governance by employers and trade unions limits their ability to achieve it. Drawing upon this idea, the article explains differences between countries by pre‐existing levels of state intervention in the labour market. It shows that devaluation has been the most far‐reaching in countries where social partners relied more on the state (Greece and Portugal, and Spain to a lesser extent). In contrast, in Italy, where employers and unions have a more autonomous function, and where the role of the state is more limited, the extent of adjustment was smaller. In a number of cases, devaluation was the result of more, rather than less, state intervention. In Italy, the government possessed fewer instruments to spur a decrease in the cost of labour.

The article contributes to the literatures on European integration and comparative political economy. On the one hand, recent contributions in the political economy of European integration, and on the Eurozone crisis in particular, have emphasised the new role of European institutions in the form of a new ‘policy intrusiveness’ in the countries of the European periphery (Theodoropoulou Reference Theodoropoulou2015; Armingeon & Baccaro Reference Armingeon and Baccaro2012a; Sacchi Reference Sacchi2015). While this literature has documented how the EU monetary regime has created asymmetric shocks and different adjustment pressures between Northern and Southern Europe (Johnston & Regan Reference Johnston and Regan2016), it has often viewed adjustment processes in the South as uniform and has rarely addressed how domestic factors within each group of countries may shape the extent of adjustment.

On the other hand, because of its focus on Northern Europe (Germany, Sweden) where social partners are usually well‐organised, the literature has tended to overlook the role of the state as a powerful actor in industrial relations systems and their liberalisation (see Hassel (Reference Hassel2006), Molina (Reference Molina2014) and Howell (Reference Howell2016) for notable exceptions). Here, I argue that a focus on the state and its instruments of regulation is necessary to understand liberalisation in countries where employers and unions have a weak governance capacity, as in Southern Europe. Building on Polanyi's (Reference Polanyi2001 [1944]: 147) classic insights, I show that wage adjustments need active state involvement to come about in European labour markets (Howell Reference Howell2016: 5).

Methodologically, the article combines comparative indicators with case studies supported by newspaper reports, official statistics, grey documents and nine expert interviews. In the following sections, I outline the literature on external constraints on Southern European countries within the Eurozone.

External constraints: The Eurozone crisis and internal devaluation

The Sovereign Debt Crisis in Southern Europe has revealed that the new architecture of the Eurozone has asymmetric distributional impacts across Northern and Southern member states (Armingeon & Baccaro Reference Armingeon, Baccaro, Pontusson and Bermeo2012b; Johnston & Regan Reference Johnston and Regan2016; Perez & Matsaganis Reference Perez and Matsaganis2018). It also changed the power balance between EU institutions and member states, giving rise to a new type of ‘policy intrusiveness’ by EU institutions in domestic socioeconomic models (Theodoropoulou Reference Theodoropoulou2015).

Höpner and Lutter (Reference Höpner and Lutter2017) show that while the coordinated wage regimes of Northern Europe (Germany, the Netherlands, Austria) display an institutional fit with the hard currency regime that characterises the Eurozone, the wage regimes of the Southern periphery do not because they lack capacity for wage restraint. While in the past Southern European countries could use nominal exchange rates (currency devaluations) to compensate for this, the removal of this instrument once in the euro caused a deterioration of their competitive position, as well as severe trade deficits. After revelations about the manipulation of public accounts data in Greece, interests on government bonds in Greece, Portugal and Ireland skyrocketed. This made it impossible for them to roll over their debt, causing a liquidity crisis and leading them to ask for rescue packages from international financial institutions such as the European Central Bank (ECB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the EU. Due to fears of contagion, bond yields on Spanish and Italian debt also increased (De Grauwe Reference De Grauwe2011). Because the ECB is now the only actor able to issue currency, countries in fiscal distress heavily depend on it to purchase government bonds (in the secondary market only because it is not allowed to buy bonds directly) and provide guarantees to buyers of Greek, Portuguese or Spanish debt that they would be able to resell it (Armingeon & Baccaro Reference Armingeon and Baccaro2012a).

As a result, the bargaining position of EU supranational institutions has become much stronger in the conditionality exchange with member states. The pivotal role of the ECB in maintaining borrowing costs at a sustainable level means that it can also credibly impose domestic reforms to the countries it bails out (such as Greece, Portugal and Ireland), or buys bonds from (such as Italy or Spain),Footnote 1 as long as they vow to remain in the monetary union. The bargaining power of EU institutions is arguably stronger in countries under an explicit adjustment programme (direct conditionality), whereby the payment of the different tranches of a bail‐out package are conditioned on a precise programme of reforms. However, it can also be effective in countries which need the ECB to purchase their debt on secondary markets through a form or ‘implicit conditionality’ (Sacchi Reference Sacchi2015).

Content‐wise, European institutions, and the ECB in particular, have had a clear agenda regarding labour market reforms. Early on, ECB officials envisaged that the common currency required a set of policies to ensure the quick adjustment of wages and prices to market conditions: lowering employment protection, reducing reservation wages and non‐wage labour costs (Duisenberg Reference Duisenberg2003). This agenda, however, had largely remained a dead letter prior to the crisis due to a lack of political clout and low borrowing costs (Fernandez‐Villaverde et al. Reference Fernandez‐Villaverde2013).

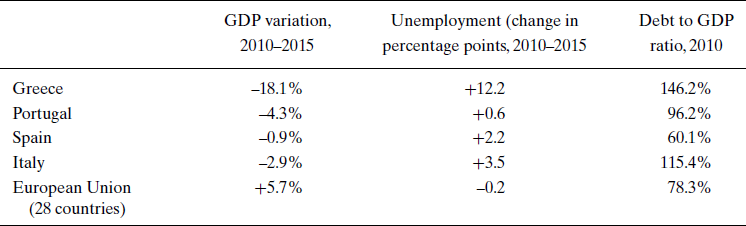

Domestic instruments: When more state intervention facilitates devaluation

So far, the existing literature has mostly focused on this new supranational architecture to explain the pressure faced by Southern European governments. It has also mostly perceived reform processes as uniform. For instance, Armingeon and Baccaro (Reference Armingeon, Baccaro, Pontusson and Bermeo2012b: 1) argue that within this asymmetric power relationship, ‘domestic politics, either party‐ or interest group‐based, does not matter: there is only one option and it is imposed from outside’. While I agree that individual countries did not have much leeway in the direction of change, I argue that domestic politics and institutions still matter to understand the capacity of governments to deliver internal devaluation. First, it is important to understand the instruments deployed by governments to achieve this goal: external pressure by itself, however strong it is, is not enough to yield domestic change in labour markets where most wages are primarily set by private firms. Second, there has been substantial variation in the extent of adjustment in the countries under scrutiny (Figure 1). We cannot totally explain this pattern of variation by changes in functional pressures for adjustment, such as gross domestic product (GDP) contraction, an increase in unemployment, or the level of government debt. While Italy has seen a greater decline of its GDP and a bigger absolute increase in unemployment than Spain (although from a much lower level) over a five‐year period, its degree of wage adjustment has been smaller. Similarly, Portugal has seen a bigger adjustment even if its unemployment level has been lower than Spain. It would also be inaccurate to say that the need for Italy to adjust was smaller: its unit labour costs increased on par with Spain prior to the crisis, and its debt‐to GDP ratio has been twice as large as Spain's and higher than Portugal's. Finally, it is also unsatisfactory to simply explain differences by the presence or absence of an adjustment programme by EU institutions, especially if one considers the similarities between Spain and Portugal in the type of measures put in place to achieve devaluation, and the difference between Spain and Italy.

Picot and Tassinari (Reference Picot and Tassinari2017) show, for instance, that reforms have been much more far‐reaching in Spain than in Italy, pointing to the diverging influence of the centre‐left as the main explanation for deregulation in the former and embedded flexibilisation in the latter. I follow these authors in assuming that we need to have a more differentiated approach to understand national patterns of adjustment. However, while Picot and Tassinari focus on party‐political factors in two countries that maintained a larger margin of manoeuvre in adjustment, I focus on pre‐existing levels of state intervention in labour markets in all Southern European countries faced with the crisis to explain capacity for internal devaluation. While it is of course important to look at the preferences of governments, we also need to look at the policy instruments they have at their disposal to allow for wages to adjust downwards. Here, I focus on minimum wages, collective bargaining regulations and employment protection as instruments that can enable wage adjustments.Footnote 2

Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece have tended to cluster together in existing typologies of capitalist models, as ‘Mediterranean’, ‘mixed‐market’ or ‘state‐led’ economies (Amable Reference Amable2003: 104–106; Ferrera Reference Ferrera1996; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2002). One overarching feature of this model, compared to North European coordinated market economies (Hall & Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001), is the weak coordination capacity of organised interests (employers and trade unions) due to low levels of organisation on the employer side and ideologically fragmented trade unions (Hancké & Rhodes Reference Hancké and Rhodes2005). In this context, the state assumed a pervasive role to ‘impose order from above’ by setting wages at the bottom of the labour market, extending the outcomes of collective bargaining to non‐bargaining parties via extension clauses, imposing the prevalence of certain bargaining levels over others and constraining the ability of employers to dismiss their employees. Because so much regulatory power was delegated to governments to organise the labour market, it also meant that governments could use this power to pursue their own agenda. In Northern Europe, trade unions often opposed this delegation, fearing that extensive state authority could potentially undermine them (see, e.g., Kahn‐Freund Reference Kahn‐Freund and Ginsburg1959: 244).

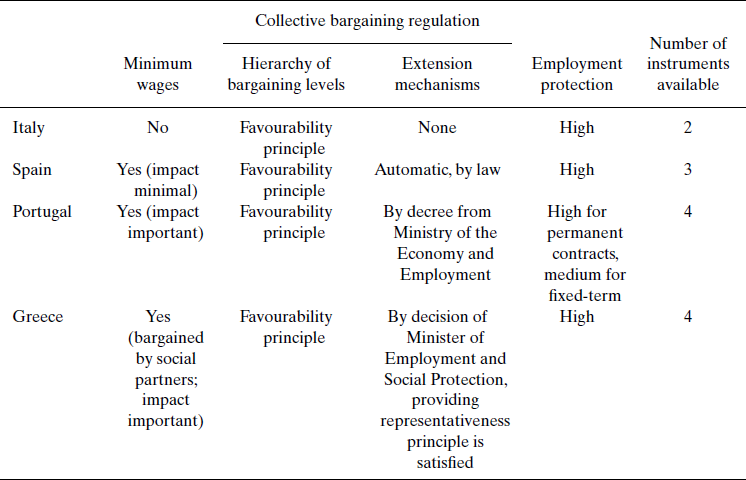

Yet, South European countries also displayed significant differences in the respective share of regulation in control of the state, on the one hand, and trade unions and employers, on the other. Hancké and Rhodes (Reference Hancké and Rhodes2005: 206) notably highlight the difference between Italy and Spain, Portugal and Greece. Italy is in some ways closer to the North European model, with a stronger coordination capacity by employers and trade unions, and a smaller role for the state in collective bargaining (see also Hassel Reference Hassel2006: 165). While these analyses covered the 1990s, this characterisation can still be observed using more recent data. For instance, according to the European Company Survey, the proportion of companies that were members of an employer organisation in 2013 was 25 per cent in Greece, 33 per cent in Portugal, 41 per cent in Spain and 50 per cent in Italy, signalling a greater coordination capacity in the latter (Table 1).Footnote 3 Here, I argue that this smaller role of the state and larger role for social partners in Italy also provided fewer instruments to achieve internal devaluation. A greater concentration of regulatory power within the hands of governments enabled greater levels of wage adjustment, while a greater governance capacity by social partners allowed for less adjustment. In the next section, I give an overview of these instruments before outlining how their use varied across countries.

Employment protection

A first central feature of South European labour market regimes has been the important role of the state in providing security by way of employment protection. In Southern Europe, the emphasis has been placed to a greater extent on protecting jobs (via strict employment protection and high dismissal costs) and less on protecting workers (through generous social benefits). A major consequence of this has been heavily segmented labour markets, with a great deal of differentiation between ‘insiders’ (mostly male, older workers in permanent employment) and ‘outsiders’ (young or female workers in fixed‐term employment).

In the perspective of internal devaluation, employment protection can play a role in downward wage adjustments via two channels. First, with high levels of employment protection, it is more difficult for ‘old’ higher paying jobs to be destroyed and ‘new’ lower paid jobs to be created when unemployment increases. Second, highly protected workers and their trade unions will be less likely to negotiate wage concessions: workers who are less protected will be more likely to accept salary cuts to keep their jobs.

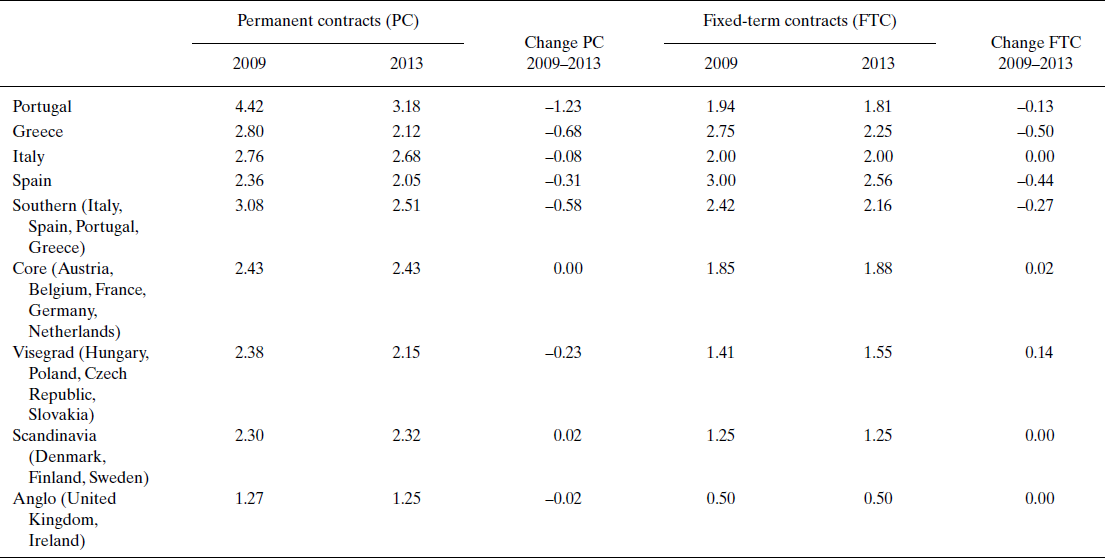

Table 2 shows the evolution of the OECD Employment Protection Index in the four countries under scrutiny between 2009 and 2013, as well as in other clusters of European countries. On average, Southern European countries indeed displayed higher levels of employment protection than core European countries for both permanent and fixed‐term contracts, even though the Southern average is pushed upwards by very high levels for permanent workers in Portugal.Footnote 4 Comparing values before and after the crisis shows that the extent of change has been much larger in the countries analysed here than in other groups of countries, and that the average index value is now very close to that of core countries.

Table 2. OECD Employment Protection Index, change 2009–2013

Source: OECD EPL Index, version 1. On the calculation of the indicator: www.oecd.org/employment/emp/oecdindicatorsofemploymentprotection-methodology.htm

Minimum wages

Another important policy instrument whereby governments in Southern Europe were able to steer labour markets was the use of minimum wages. The minimum wage not only acts as a floor for low wages, but also as a floor for wage developments in collective bargaining because trade unions and employers use it as a reference point. Here, we can observe significant variation between the countries analysed, with different levels of state intervention. At one end, Italy stands out as one of the few European countries without a national minimum wage, meaning that the state has no direct influence on wage levels at the bottom of the labour market (except for social benefits as reservation wages). Minimum wages are set at the sectoral level by social partners. Spain does have a minimum wage but it is set at such a low level that its influence on wage bargaining is negligible: low wage sectors typically have their own sectoral minimum wage above the national one (Banyuls et al. Reference Banyuls, Cano and Aguado2010). In 2010, only about 1 per cent of Spanish full‐time workers earned the minimum wage. In contrast, the incidence of the minimum wage is much more important in Portugal and Greece: in 2010, c.10 and 7 per cent, respectively, of full‐time workers in these countries earned the minimum wage.Footnote 5 In Greece, the minimum wage negotiated by social partners played an important orientation function for wage‐setting as a whole (Voskeritsian & Kornelakis Reference Voskeritsian and Kornelakis2011). What this concretely means is that the influence the government can exert on wages at the bottom end of the labour market is more powerful there.Footnote 6 Lowering (as in Greece) or freezing (in Portugal) the minimum wage can be a powerful instrument of devaluation. In contrast, this tool has less clout in Spain and is not available in Italy.

Collective bargaining regulations: Extensions and levels

Finally, the last (and perhaps most important) instrument of devaluation analysed here concerns the regulation of collective bargaining – namely the statutory extension of collective bargaining agreements to entire economic sectors, and the statutory determination of the level (firm, sector, regional, national) that prevails over others. The extension of collective bargaining agreements is the procedure whereby the conditions agreed in agreements between trade unions and employer organisations are made compulsory for all firms in a sector or region even if they have not negotiated the agreement themselves (Schulten et al. Reference Schulten, Eldring, Naumann and Schulten Van Guys2015). This practice is widespread across Europe, and it helps explain the wide discrepancy between low and declining levels of unionisation and persistently high levels of collective bargaining coverage. Traxler et al. (Reference Traxler, Blaschke and Kittel2001: 194) showed, for instance, that extension rules were the single most important factor to explain high collective bargaining coverage.

This practice was important in Southern Europe. It was a way to ensure a level playing field and establish minimum standards in countries with many small firms without employee representation, and low‐wage competition on price. Some countries also have provisions (e.g., the principle of ultraactividad in Spain) whereby the applicability of collective labour agreements persists even after their expiry if no new employment terms are agreed upon. These rules can be understood as brakes to internal devaluation because they prevent firms from offering lower wages than those set in collective agreements even if unemployment increases. The principle of ultra‐activity makes it possible for trade unions to refuse to sign new collective agreements if their terms are less favourable. Because firms rely on the state to extend collective bargaining agreements and impose order in the labour market, this confers significant power to the state if it decides to withdraw its supporting function. Because of the low level of organisation of both employers and unions, firms in Southern Europe (and most specifically Portugal, Spain and Greece) cannot impose this order on their own.

However, there was again a significant level of variation across the countries under scrutiny prior to the crisis. Extensions were an administrative decision by the Ministry of Labour in Portugal and Greece. In Spain, collective agreements are automatically extended with force of law without the need for a decision. Italy, by contrast, is one of the few countries in Europe with no extension mechanisms. There is however a functional equivalent: Article 36 of the constitution guarantees citizens a ‘fair remuneration’. In case of dispute, labour courts have taken the wages in the relevant collective agreement as the benchmark for ‘fair remuneration’ (Tomassetti Reference Tomassetti2014: 126; Traxler Reference Traxler2001). However, this latter mechanism is beyond the control of the government. It cannot decide to stop it to achieve devaluation. Another difference in state intervention is that the validity of agreements is set by law in Spain and Portugal, while it is left to the social partners in Italy (Addison et al. Reference Addison, Portugal and Vilares2016: 555).

The second important area is the hierarchy of bargaining levels. Southern European countries commonly operated a two‐tier bargaining system, where sectoral agreements have legal precedence over firm‐level bargaining, drawing on the favourability principle (as in most Continental countries). Hence, sectoral agreements acted as a wage floor and firm‐level agreements could only be used to improve workers’ conditions. The sector level was the dominant level, and there was little firm‐level bargaining taking place, mostly in large firms.

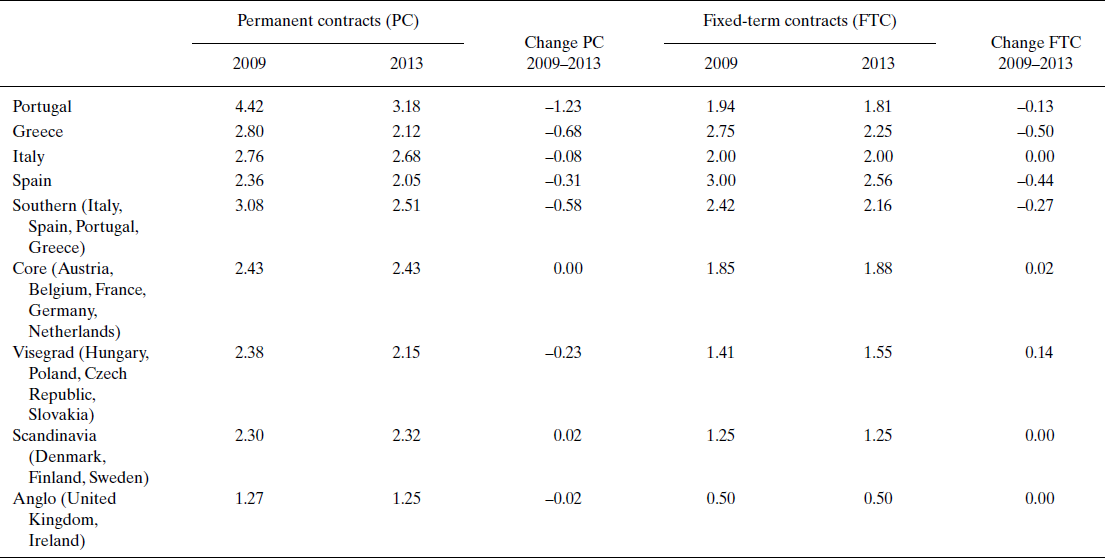

Summing up, we can establish a continuum in our four countries in the number of tools available to governments to achieve internal devaluation on the eve of the crisis (Table 3). Greece, and then Portugal, appeared as the countries where state control was the most far‐reaching, with minimum wages affecting a larger share of the workforce, high employment protection, significant discretion of the government in extending collective bargaining agreements and a hierarchy of bargaining levels set by law. Spain could not really use the minimum wage to adjust wages downwards because only a small part of the workforce was affected by it. Finally, Italy was the country with the fewest available instruments, with no minimum wages and no extension mechanisms.

Table 3. Summary of policy tools

Data and methods

I will now use case studies to trace empirically the connection between the instruments of regulation outlined in the previous section (independent variables) and the degree of wage adjustment (dependent variable) in Spain, Portugal, Italy and Greece. Rather than measuring the respective importance of each policy instrument in internal devaluation, I seek to uncover the mechanisms whereby they can yield downward wage adjustment. Hence, the approach used here is more focused on ‘how’ rather than ‘to what extent’. Obviously, many factors can influence wage adjustments, and a different approach would be required to assess the main drivers of wage adjustments. However, a case study format can provide valuable insights into the mechanisms that connect policy reforms and labour market outcomes (Punton & Welle Reference Punton and Welle2015).

The empirical analysis draws on a variety of sources: a compilation of quantitative indicators of labour market regulation and performance; primary and secondary sources in Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and English (government and EU reports; newspaper articles); and nine background interviews with experts involved in policy making or policy evaluation (the list of interview respondents can be found in the Appendix). In each country, I give a synthesis of reforms and effects in each of the domains analysed.

National trajectories of labour market reform

Greece

The Greek system of labour market regulation before the crisis displayed a rigid hierarchy of bargaining levels where firm‐level agreements were marginal and subordinate to the sectoral level (‘favourability principle’), extensive coverage of collective agreements and high dismissal costs. It is important to mention that unlike the other countries analysed here, Greece has never seen the emergence of social pacts or other structures of interest intermediation in the 1990s (Lavdas Reference Lavdas2005), and it scored low on indexes of neo‐corporatism (Siaroff Reference Siaroff1999: 185), meaning that the state was the primary actor of regulation. In fact, it was more effective for trade unions and employers to lobby the parties in power than to reach agreements among themselves on issues of public policy (Lavdas Reference Lavdas2005).

During the adjustment programme imposed by European institutions, this system has essentially been dismantled. Because of the high level of state intervention in wage‐setting, there were many policy tools available to liberalise the labour market and achieve an astounding level of downward wage adjustment (Voskeritsian & Kornelakis Reference Voskeritsian and Kornelakis2011). In the next section, I outline the reforms put in place and how they facilitated wage adjustments.

Minimum wages

The minimum wage in Greece was an important steering mechanism for wage developments as a whole because it set the floor above which sectoral wage agreements had to be negotiated; company agreements had to be set above sectoral agreements. Hence, the minimum wage had to go down for other wage‐setting mechanisms to adjust downwards. This was achieved through more, not less, government control. Indeed, while the national minimum wage was hitherto set in an economy‐wide agreement (the national general collective agreement) between trade unions and employers, in 2012 the government took over its determination, confining social partners to an advisory role (Law 4046/2012 and Act of Cabinet 6/2012). While trade unions and employers had already agreed on a freeze in 2010, in 2012 it was reduced by 22 per cent for employees above 25, and by 32 per cent for workers younger than 25. For the first time, the 2013 general collective agreement did not include a minimum wage, to the dismay of both trade union and employer associations (Voskeritsian et al. Reference Voskeritsian, Veliziotis, Kapotas and Kornelakis2016). Figures indicated that the minimum wage now concerns about 35 per cent of the workforce in 2017, which is a dramatic increase compared to the period prior to the crisis. Concretely, this means that the wages of more than a third of the workforce is set by the state.Footnote 7

Collective bargaining regulation

Reforms were enacted through legislative changes (Law 3899/2010 and then Law 4024/2011) which reverted to the existing hierarchy of bargaining levels, and suspended extension mechanisms. First, the favourability principle was abolished, allowing firms to negotiate wages below those agreed in sector agreements. Agreements negotiated within companies – where workers are less well organised – were to prevail. Most importantly, the monopoly of bargaining of trade unions was abolished and firms were now allowed to negotiate company‐level agreements with other groups – so‐called ‘associations of persons’ (AoP) – provided they were supported by 60 per cent of the workforce (Voskeritsian et al. Reference Voskeritsian, Veliziotis, Kapotas and Kornelakis2016). These groups were typically more likely to engage in concession bargaining than trade unions. After 2011, the number of agreements concluded with AoPs far outpaced those negotiated with trade unions. This new framework has had a dramatic impact on wage developments. Between 2011 and 2013, 88.6 per cent of agreements concluded with non‐union groups involved wage cuts, against 41 per cent of those signed by trade unions (Daouli et al. Reference Daouli2013: 470).

Second, extension procedures were suspended indefinitely, so that agreements between unions and negotiating firms could no longer be extended to non‐negotiating parties. Measures were also taken to shorten the duration of agreements to create incentives for negotiating parties to update agreements quickly following changing economic conditions (Daouli et al. Reference Daouli2013: 9; Voskeritsian & Kornelakis Reference Voskeritsian and Kornelakis2011). As a result, the total number of collective agreements fell from 661 in 2008 to 212 in 2015, leaving more workers uncovered (Schulten Reference Schulten2015: 3). Without extensions, there were no incentives anymore for employers to negotiate sectoral agreements knowing they would not bind their competitors. As collective agreements expired and were not replaced, coverage collapsed, leaving workers to negotiate their wages individually in a context of soaring unemployment and the economy in freefall. Even if collective bargaining coverage for Greece has been difficult to estimate, a study by the ILO (2016: 70) points to a drop from 83 per cent in 2009 to 10 per cent in 2014. As a whole, this transformation has led to an astounding level of downward wage adjustment, with a 20 per cent decline in real wages (Schulten Reference Schulten2015: 4). As the state withdrew its supportive functions, the bargaining power of labour dramatically has shrunk.

Employment protection

Turning to employment protection, the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) outlined measures to

extend the probationary period for new jobs, to reduce the overall level of severance payments and ensure that the same severance payment conditions apply to blue‐ and white‐collar workers, to raise the minimum threshold for activation of rules on collective dismissals especially for larger companies, and to facilitate greater use of temporary contracts and part‐time work. (European Commission 2010: 68)

Accordingly, the notice period for terminating white‐collar permanent contracts was reduced, severance payments were cut by 50 per cent for this category of workers, and thresholds for dismissals were lowered. More precisely, the threshold (in terms of the number of employees) for what is considered a collective dismissal (which needs to be justified) was increased, making it easier to dismiss employees without justification. Some measures were aimed at fixed‐term contracts, making it more difficult to line up fixed‐term contracts without a justification (Karantinos Reference Karantinos2014: 21).

Portugal

Similar to Greece, the bulk of the labour market measures adopted in Portugal during the crisis derived from the MoU drafted with the European Commission, the IMF and ECB (European Commission 2011a: 21–24; b: 24–26). While reforms were less drastic, they used the same pool of instruments, the most important of which being collective bargaining regulations.

Minimum wages

In contrast to Greece, the national minimum wage in Portugal was not a collective agreement but was already set by the government prior to the crisis. The main measure taken by the government was to freeze it at €485 a month from 2012 onwards, putting a sudden stop to nominal increases above 5 per cent in 2008, 2009 and 2010, and a 2.1 per cent increase in 2011. In 2010, 10.5 per cent of dependent workers were on the minimum wage; in 2014 this proportion had nearly doubled to 19.6 per cent, and it rose to 26.6 per cent in 2016.Footnote 8 Moreover, 36 per cent of new contracts in 2016 were set at the minimum wage.Footnote 9

Collective bargaining regulations

The most significant area of reform has been the collective bargaining framework and, in particular, the practice of statutory extension. While reforms concerning the expiration of collective agreements were adopted in 2009, the most important changes were implemented in the direct aftermath of the MoU, mostly in the revision of the Labour Code in 2012 (European Commission 2011b: 25, 52). Up to then, the Labour Ministry would routinely extend collective bargaining agreements without representativeness criteria, and extensions would often act retroactively. Arguing that extension procedures imposed unsustainable wage conditions to outside firms with resulting employment losses, the conservative government of Pedro Passos Coelho adopted more restrictive conditions for erga omnes extensions. From now on, only agreements signed by firms representing more than 50 per cent of employees in a given sector could be extended.Footnote 10 Both employers and unions resisted these changes.Footnote 11 Employers in particular argued that the new criteria for extensions would allow some companies to offer worse conditions and generate unfair competition (Interview CCP). In fact, the more restrictive extension mechanisms led collective bargaining to a blockade: employers did not want to negotiate agreements that would not bind their competitors, and employer associations feared that firms would leave employer bodies to avoid complying with the terms of collective labour agreements (CLAs), for instance, to be able to offer lower wages.Footnote 12

Even if the principle of statutory extension was not suspended altogether, as in Greece, this higher threshold led to a considerable slowdown in new collective agreements: in 2008, 1,894,000 workers were covered by new collective bargaining agreements; in 2014, this number had fallen to 246,000 (UGT 2015: 6). Because of the new criteria, the number of administrative extensions declined from 199 in 2008 to 46 in 2013. The total number of new CLAs fell from 296 in 2008 to 85 in 2012, before picking up again after the government partly backtracked in 2014 by easing the criteria of representativeness. These changes in extension rules were accompanied by changes in the provisions regulating the expiry of agreements (their duration was brought down from five to three years, and their validity after expiry from 18 to 12 months), leading to a greater number of collective agreements expiring without being renewed (Addison et al. Reference Addison, Portugal and Vilares2016).

Alongside new extension rules, there was also a movement of decentralisation to the firm level, where labour unions are weak.Footnote 13 While in 2008 58.7 per cent of new collective agreements were negotiated at the sector level, this share had fallen to 28.7 per cent in 2013, with company agreements representing more than half of all new agreements (up from a third in 2008) (UGT 2015: 5). This was, however, in a context of the collapse in the number of new sector agreements. The movement of decentralisation was sanctioned by a tripartite agreement in 2011 allowing for sectoral agreements to delegate certain issues to the firm level. This reform has had little effect, however. In contrast to Greece, it must be noted that the request made by the Troika to allow for firm‐level representation without a trade union mandate – the request that allowed Greek trade unions to be side‐lined by AoPs in firms – was not implemented. The Portuguese constitution gives an exclusive mandate to trade unions in wage bargaining.

Employment protection

Portugal was an outlier in the OECD for its high level of protection of permanent contracts, while the ease of hiring temporary workers was in line with the OECD average. The thrust of the reforms implemented was to bring protection for permanent contracts in line with the OECD average. A major revision of the labour code (Law 23/2012) was adopted in 2012, providing for a decrease by 50 per cent in compensation for extra hours, a reduction in severance payments, a broader understanding of ‘fair dismissal’, fewer holidays and the introduction of an ‘hour bank’ extending by two hours the maximum duration of the normal working day.Footnote 14 Severance payments were a particularly important element of reform in this domain. They were reduced from 30 days per year of seniority to ten, thereby reducing the cost of dismissal of older – and more expensive – workers.

Spain

Both the diagnosis and the solutions proposed for the Spanish labour market were fairly similar to those presented in Portugal. Downward wage flexibility was the main objective of labour market reforms in the face of what was perceived as an over‐centralised system of collective bargaining that prevented wages from adjusting swiftly to the crisis. The setup of the Spanish labour market was somewhat idiosyncratic, however. Reforms conducted in the 1980s led to a tremendous increase in fixed‐term employment (for about a third of the workforce), which also led to a great level of job destruction when the housing bubble that underpinned Spanish growth burst. Unlike in Greece and Portugal, however, reforms of minimum wages and extension procedures were either not undertaken, or were of limited effect.

Minimum wages

As mentioned above, the minimum wage in Spain was not such an important policy instrument as in Greece or Portugal. It was already set at such low levels that it did not act as a steering tool for collective bargaining. Indeed, in 2009, the Spanish minimum wage was set at 39 per cent of median wages, against 48 per cent in Greece and 50 per cent in Portugal.Footnote 15 Accordingly, it did not feature prominently in the reform process, even if its level was frozen as in Portugal. In 2013, proposals by the Banco de Espana mentioned the possibility of not applying the minimum wage to some categories of workers, such as the young, but they did not materialise.Footnote 16

Employment protection

Dismissal protection was a much more important issue. In early 2010, the socialist government of José Luis Zapatero first sought to reach an agreement between trade unions and employers on a reform of the labour code to ease collective dismissals.Footnote 17 Eventually, many of these negotiations stalled, and the PSOE government adopted a reform unilaterally in June 2010, when bond yields were reaching their highest point since the beginning of economic and monetary union.Footnote 18 The major aspects of the reform were a limitation in the duration of so‐called ‘project contracts’ (contratos de obra y servicio) to two years; a change in fixed‐term contracts to increase severance payments progressively with tenure; and an extension in the motives for justified dismissals, reducing severance pay for companies facing economic difficulties.Footnote 19 In the summer of 2011, ECB President Jean‐Claude Trichet wrote a (then secret) letter to José Luis Zapatero in which he suggested a number of concrete reforms that could strengthen the credibility of Spanish government bonds and facilitate their purchase by the ECB. The measures included a wage bargaining reform aimed at the decentralisation to the firm level and preventing sector‐level agreements, ‘bold and exceptional steps’ towards the abolition of inflation‐adjustment clauses, the encouragement of wage moderation, the introduction of a new labour contract with ‘only very low severance payments’ and removing limitations on the rollover of fixed‐term contracts (Trichet Reference Trichet2011).

The new PP government led by Mariano Rajoy was determined to implement a more radical reform of the labour code, to take effect in 2012, which would strengthen internal flexibility within companies (Partido Popular Reference Popular2011: 18). The main points of the reform passed in February 2012 were a generalisation in contracts with severance payments equivalent to 33 days per year with a maximum of 24 months’ severance pay (versus 45 days so far), a facilitation of dismissals for economic causes with a severance payment of a mere 20 days per year. As a whole, average severance payments were cut by two‐thirds. Data tends to support the idea that this facilitated downward wage adjustment. First, after the labour reform came into force, real wages decreased for the first time since the beginning of the crisis. Second, there was a significant difference between those that kept their job during the crisis, and those that changed jobs and took up ‘new’ ones. Between 2008 and 2012, while the former saw a 2 per cent wage increase in real terms, those that changed saw a 4.8 per cent wage decrease (Perez & Jansen Reference Perez and Jansen2015: 8).

Collective bargaining regulation

Regarding collective bargaining, the core of the reforms undertaken in 2012 concerned internal flexibility – namely the possibility for firms to withdraw from the terms of sectoral agreements. This is an important difference from Greece and Portugal in the sense that the focus of reforms has not been to shrink the coverage of collective bargaining but to allow firms to derogate to some of the provision of sector agreements. In line with this, collective bargaining coverage in Spain has remained relatively high (77.6 per cent in 2013).

One central aspect of the reforms was the establishment of the primacy of company agreements over agreements established at higher levels, paving the way for a substantial movement of decentralisation of collective bargaining.Footnote 20 The reform carried out in 2012 made it easier for firms to opt out from collective agreements altogether and allow employers to change conditions unilaterally. It also shortened the period of validity and ‘survival’ of agreements.Footnote 21 Sectoral agreements could also regulate the delegation of competences to the firm level.

However, the attempt to decentralise bargaining has had a very limited direct impact. Indeed, very few firms have effectively used this possibility to transfer regulatory powers to the firm level. For small firms in particular, negotiating agreements themselves rather than delegating wage negotiations to employer associations at the sectoral level may not appear an attractive option (Perez & Jansen Reference Perez and Jansen2015: 26). However, the threat of doing it has undoubtedly strengthened employers over trade unions, who may have been more willing to engage in wage concessions faced with the threat of employers deserting sector‐level bargaining (Interview, country expert, Spain). There is evidence that the reform has had an impact on wage adjustment. In 2010 and 2011, bargained wage increases amounted to 1.5 and 2 per cent per year even if unemployment increased by nearly 4 percentage points between 2009 and 2011. In contrast, after the reform, bargained wage increases were only 0.53 per cent, while unemployment decreased (Malo Reference Malo2015: 30). This can be considered as evidence that the economic crisis did not yield devaluation on its own, and that policy reforms in the regulatory framework were necessary for wages to adjust.

Italy

Italy stands apart from the other cases analysed here because of the absence of internal devaluation achieved during the crisis. While the differences in political preferences play a non‐negligible role (Picot & Tassinari Reference Picot and Tassinari2017), the instruments available to the government to influence wage‐setting were limited, even if the level of external pressure was fairly comparable to Spain.Footnote 22

In August 2011, as yields on Italian government bonds were increasing, Mario Draghi and Jean‐Claude Trichet sent a (private) letter (subsequently leaked to Italian newspapers) to Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi which was similar in content to the one the ECB sent at the very same time to José Luis Zapatero. He emphasised that the credibility of the Italian sovereign debt needed to be enhanced, and suggested a number of measures to signal to investors and the ECB that Italy was committed to structural reform. Trichet advocated, again, for a decentralisation of collective bargaining to allow for more downward flexibility at the firm level. Additionally, he advocated reforms of employment protection that would enable the transfer of workers towards higher productivity sectors and the creation of a proper system of unemployment insurance, concluding somewhat peremptorily that ‘he trusted that the government would take the appropriate measures’.Footnote 23

Minimum wages

As mentioned above, there is no uniform state‐mandated minimum wage in Italy, but instead a series of minimum wages set by sector through collective bargaining. In this context, the fixation of minimum wages is outside of the remit of public authorities, and they could not use it to adjust wages. Instead, it is set exclusively by social partners in the respective sector. Interestingly, the Jobs Act elaborated by the Renzi Government contained provisions for the introduction of a national minimum wage, but it was eventually not included in the implementation decrees.Footnote 24

Collective bargaining regulation

In Italy, there are no extension mechanisms where the state can decide to bind non‐signing parties. Generally, the approach to state regulation in industrial relations adopted in Italy has been to empower the actors of collective bargaining – by assigning de facto representation monopolies – rather than regulating them from outside (Senatori Reference Senatori2013: 3). Hence, the coverage of collective bargaining is mainly shaped by a higher level of adhesion to employer organisations, as well as the informal use of collective agreements as benchmarks by labour courts, and not by direct state regulation such as erga omnes extensions. Hence, even if it wanted to, it was difficult for the government to have much influence on wage‐setting mechanisms. In fact, many of the reforms undertaken during the crisis were the result of autonomous agreements by employers and unions, and less by legislative changes as in the other countries. At the political level, the only real policy tool that could be acted on was the hierarchy of bargaining levels, with an attempt at decentralisation.

First, the 22 January 2009 cross‐industry framework agreement provided for sectoral agreements to allow for some decentralisation to the firm level, even if this decentralisation needed to be agreed at the sectoral level. Some leeway for opt‐out closures was also granted. Under the Berlusconi Government, a somewhat greater degree of state regulation was introduced. Law 148/2011 (Article 8) enabled company agreements to derogate from agreements at higher levels (contrattazione di prossimità) under a number of conditions, and these could be given an erga omnes effect to cover workers that are not members of the signatory union (Garilli Reference Garilli2012; Senatori Reference Senatori2013). However, as in Spain, employers have made little use of such a possibility. Generally, changes to the collective bargaining structure in Italy have preserved the sectoral level as the primary locus of wage‐setting, which contrasts sharply with the policy focus on the primacy of company agreements in Spain, the limits on extensions decided in Portugal, or the total suspension of extension and the side‐lining of trade unions through AoPs in Greece. The timid steps taken by Italian employers to decentralise the bargaining system have not gone far enough for some actors. One of the most significant examples of this has been the withdrawal of the FIAT company from the main employer body Confindustria in 2011. Confindustria, the most important employer body, said that it would not use this margin of flexibility to delegate decision making to the firm level in the agreement that FIAT was bound by.Footnote 25 Because Italy has no extension rules, it was possible for FIAT to leave Confindustria and no longer be bound by the agreement. However, the objections of FIAT had more to do with constraints on its production processes than with a desire to offer lower wages.

Employment protection

The reform pattern observed in the Italian labour market sought to respond to similar problems as those faced in other countries – namely a low level of wage flexibility and an enhanced pattern of segmentation, notably between young and older workers, and high dismissal costs (Picot & Tassinari Reference Picot and Tassinari2017). A politically important symbol of employment protection in Italy was the so‐called ‘Article 18’ of the workers’ statute, which enabled workers dismissed unfairly to be reinstated in their previous job. Even if this procedure was rarely used, it was perceived as a disincentive for firms to adjust their labour force. As elsewhere, high levels of protection were thought to create strong patterns of segmentation.

First, the technocratic government of Mario Monti, which replaced Silvio Berlusconi in November 2011, introduced a number of reforms. The so‐called ‘Legge Fornero’ (92/2012), named after the new Labour Minister, an academic economist, sought to get rid of the famous Article 18.Footnote 26 However, after substantial protests, the government eventually backtracked, as unions were able to forge an alliance with the left‐of‐centre Partito Democratico, and watered down some of the measures, especially permanent contracts (Fornero Reference Fornero2013: 11).

Matteo Renzi's centre‐left government of 2014–2016 engaged in a similar attempt to reform employment protection, presenting it more as a way to overcome the strong dualism of the Italian labour market (Picot Reference Picot2014). Here again, a reform of Article 18 was on the table, triggering a general strike organised by the biggest trade union confederation, CGIL, in December 2014.Footnote 27 In spite of the resistance from the unions and within his own party, Renzi managed to pass the reform through parliament in a vote of confidence in December 2014. The final version of this reform included: the creation of a single contract with increasing tenure; the suppression of contributions of the so‐called ‘compensation fund’ (cassa integrazione) in case the company goes bankrupt; and the suppression of the obligation of reintegration of the worker in case of unfair dismissal.

Discussion and conclusion

I have argued in this article that the extent of state regulation in wage‐setting prior to the crisis helps explain differences in wage adjustment in Southern Europe during the crisis. The more policy instruments governments had at their disposal to influence wage‐setting, the greater their capacity to enable downward wage adjustment. We can therefore see an ordering with Greece at one end, followed by Portugal, Spain and Italy. In line with early arguments by Polanyi (Reference Polanyi2001 [1944]) and Gamble (Reference Gamble1988), the case studies provided evidence that ‘market responsiveness’ actually requires high levels of state intervention, and that market actors (employers) were often more reluctant than state actors to liberalise and spur a fall in wages, notably because they have to deal with militant labour unions and a potentially damageable fall in domestic demand. For instance, the leadership role of the state could be seen in the reluctance of Portuguese employers to abandon extension procedures, or of Spanish or Italian employers to make full use of the possibility to decentralise bargaining to the firm level. Along similar lines, the radical adjustment of the Greek minimum wage was accompanied with an increase in state intervention, with the government taking over its determination, much to the dissatisfaction of employers.

My argument is compatible with existing analyses seeking to explain responses to the Eurozone crisis. While Picot and Tassinari (Reference Picot and Tassinari2017) or Cioffi and Dubin (Reference Cioffi and Dubin2016) emphasise partisan preferences, I emphasise the policy instruments available to governments to achieve these preferences. It is true that the Italian government was certainly less willing to engage in the same deregulation course as the Spanish because of ideological factors, but the timidity of reforms conducted under the Berlusconi and Monti governments seems to show that the domestic toolbox of any Italian government was limited to achieve wage adjustment. The argument is also compatible with a path‐dependence argument, denoting longstanding dynamics whereby state power was deployed to achieve macroeconomic goals in the past. The social pacts struck in Spain, Italy or Portugal in the 1990s were, for instance, analysed as state‐sponsored responses to achieve wage moderation in the absence of coordination structures (Hassel Reference Hassel2006; Molina Reference Molina2014). Here, I have shown that state intervention was an instrument of choice, but while it was used as an instrument of coordination in the past, it has more recently been used as an instrument of liberalisation. The argument presented here focused on mechanisms, mostly for the purpose of theory development. It should be complemented with large‐N evidence over a wider set of countries to test the impact of the different instruments outlined here to achieve wage adjustments beyond Southern Europe. Micro‐level data as used by Perez and Matsaganis (Reference Perez and Matsaganis2018) should also be used to probe the impact of each policy instrument on wages, but also on outcomes such as inequality.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Ken Dubin, Jonathan Hopkin, Fabio Bulfone, Catherine Moury, Angie Gago, Ian Greer, Elisa Pannini, Andreas Kornelakis, Adam Standring, Rui Branco, Daniel Cardoso, Stefano Sacchi, as well as three anonymous reviewers for useful comments and suggestions. Research assistance by Bruna Consiglio and Daniel Cardoso, as well as funding by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (PTDC/IVC‐CPO/2247/2014, project led by Catherine Moury) and the Institute of Public Administration at Leiden University, are gratefully acknowledged.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix: Interviews and oral sources

Spain: Industrial relations expert and country referent for Spain for the European Foundation for the Improvement of Working Conditions, by phone from Barcelona, 12 December 2017.

Portugal: President, Confederation of Portuguese Services, 24 October 2017.

Portugal: President, Confederation of Portuguese Farmers CAP, Lisbon, 20 October 2017.

Portugal: President, Confederation of Portuguese Entrepreneurs CIP, 18 October 2017.

Portugal: Legal advisor, Confederation of Portuguese Farmers CAP, Lisbon, 3 November 2017.

Portugal: Former Portuguese State Secretary for Employment, 2011–2013, London, 23 May 2015.

Portugal: Economic analyst, Portuguese labour market, European Commission, by phone, 10 May 2016.

Italy: Former Italian Minister of Labour, Social Policies and Gender Equality, 2011–2013, Moncalieri (Turin), 13 May 2016.

Greece: Informal discussion with Dr Andreas Kornelakis, Geneva, 3 July 2017.