Introduction

Dog relinquishment issues in Taiwan

Dog relinquishment has been an ongoing concern in Taiwan — an affluent, densely populated island with a population of 23 million people (ROC National Statistics 2024). Taiwanese cultural and religious beliefs, such as compassion for animals and views on reincarnation, have contributed to the practice of releasing unwanted dogs into streets or parks, believing that the animals will find their way to a better fate. Combined with a low sterilisation rate of dogs at the time (20%), the stray dog population grew to 1.3 million in the 1990s (Hsu et al. Reference Hsu, Liu Severinghaus and Serpell2003). The huge stray dog population negatively impacts not only the dogs’ welfare but also other animals and human society (Yan & Teng Reference Yan and Teng2023).

The Animal Protection Law, passed in 1998, attempted to address this problem by enforcing the registration of dogs, levying fines for dog abandonment, and regulating animal breeders and shelters (Wu Reference Wu2022). While regulations increased the adoption rate from animal shelters, the number of relinquished animals also increased, with stray animal populations remaining high compared to countries with similar populations (Peng et al. Reference Peng, Lee and Fei2012). This is driven partly by low trust in the animal shelters, scarred by numerous scandals involving shelter mismanagement (Weng et al. 2006b). Since animal shelters would euthanase animals not quickly adopted or reclaimed, many dog owners believed freeing their dogs would be more humane than surrendering them to shelters (Hsu et al. Reference Hsu, Liu Severinghaus and Serpell2003).

Taiwan’s strong cultural opposition to animal euthanasia culminated in its ban in 2017 (ROC Law 2021). Today, owners can relinquish dogs in animal shelters for a fee, allowing them to give up their animals without violating abandonment laws (Taipei City Animal Protection Office 2024). While this reduced the abandonment of dogs on the streets, the relative ease of dog relinquishment shifted the burden to animal shelters, which receive more animals than can be managed. Dogs in shelters often live in severely overcrowded and noisy conditions, with constant exposure to unfamiliar animals, leading to elevated stress and an increased risk of illness (Barnard et al. Reference Barnard, Pedernera, Candeloro, Ferri, Velarde and Dalla Villa2016; Yan & Teng Reference Yan and Teng2023). With animal shelters underfunded, shelter workers in Taiwan are tasked with managing far more animals than the shelters’ designed capacity, leading to burn-out and mental health challenges (BBC News 2017).

Policies and efforts addressing dog relinquishment in Taiwan have focused largely on managing dogs after owners have decided to relinquish them — such as incentivising owners to relinquish dogs to animal shelters instead of on the street, and funding and regulating animal shelters. However, the effectiveness of these measures has been questioned (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Lai, Fei and Jong2015). Increasing attention has been called on the commercialisation of companion animals, such as sales-oriented pet shops promoting impulsive purchases, profit-oriented supply chains involving unethical breeders, and inadequate pet-keeping practices of unprepared owners, which end in unsuccessful ownership. Therefore, this study investigates the deeper causes of dog relinquishment in Taiwan by examining owners’ motivations for dog ownership, their channel of acquisition, and their dog-keeping practices, which may better explain the pathway of dog relinquishment. This will be helpful for developing targeted interventions that address the root causes of dog relinquishment, reduce the strain on animal shelters, and improve animal welfare in Taiwan.

Contributing factors to dog relinquishment in Taiwan

Several factors may have contributed to the high rates of dog relinquishment in Taiwan. Its ageing population and very low birth rates, with a shrinking human population since 2020, coincide with the rapid rise in the demand for companion pets (ROC National Statistics 2024). Between 2018 and 2022, the number of pet shops increased by 28.5%, from 6,486 to 8,335. Sales in the pet industry (pet sales, pet care, and pet products) also increased by 45.7%, from 26.6 to 38.7 billion NT$ (New Taiwanese Dollars) (Yang Reference Yang2023). Studies indicate that illicit puppy breeding and trade are driven by substantial financial incentives (Maher et al. Reference Maher, Pierpoint and Beirne2017). Animal welfare groups believe that the surge in demand led to purchases by unprepared owners, fuelling unethical breeding practices in the underregulated pet-sales industry (Environmental & Animal Society of Taiwan 2022).

Dogs from pet shops are suspected to have more health and behavioural problems, increasing their risk of relinquishment. The primary channels of dog purchases in Taiwan are kennels and pet shops. Kennels, commonly called quanshe in Taiwan, are venues that breed and sell dogs on-site, whereas pet shops are retailers of dogs bred elsewhere. While the law mandates licensing for breeding and selling dogs (ROC Law 2007), enforcement has been challenging due to limited resources and a lack of oversight. In Taiwan, investigative reports have exposed how unlicenced breeders operate under inhumane conditions, forcing mother dogs into relentless reproduction and keeping puppies in poor environments with early weaning and maternal separation. To obscure their origins, these puppies are legitimatised through licenced but complicit kennels before being sold in pet shops to unsuspecting buyers (Liberty Times 2014; Taiwan Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals 2022).

Moreover, commercial pet shops are blamed for encouraging impulse purchases, such as by showcasing puppies in window displays (Environmental & Animal Society of Taiwan 2022). This encourages spontaneous sales to those unprepared for the responsibilities of dog-keeping. The resulting lack of preparedness often leads to owners being unable to meet their pets’ long-term needs. Consequently, owners also share the blame for the high rates of dog relinquishment. Studies have found household abandonment to be the primary driver of Taiwan’s stray dog problem (Peng et al. Reference Peng, Lee and Fei2012). The top reasons for dog relinquishment in Taiwan were ‘too much trouble to look after’ for the dog owner (36.1%) and problem behaviours of the dogs (29.5%) — behaviours such as chewing and barking that owners find to be problematic (Hsu et al. Reference Hsu, Liu Severinghaus and Serpell2003).

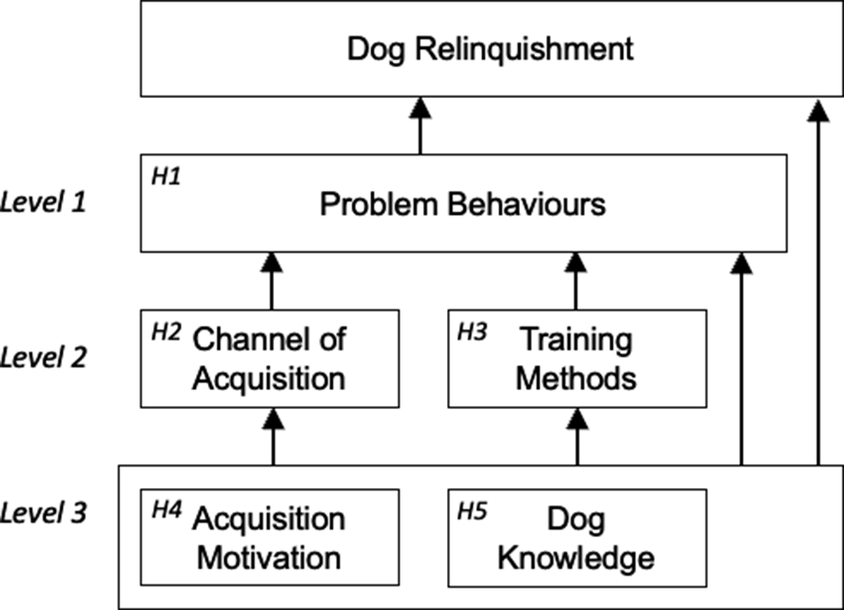

This study examines the relevance of these factors in Taiwan and identifies the factors that best explain owners’ relinquishment. To achieve this, we leverage the concepts and measurements identified in previous research to examine the relationship between problem behaviours, the acquisition channel, training methods, acquisition motivation, dog knowledge, and dog relinquishment. This traces the pathway to relinquishment, which is visualised in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The proposed pathways in which owners’ acquisition motivation, dog knowledge, the channel of acquisition, training method, and problem behaviours ultimately link to dog relinquishment

Level 1 predictors

H1. Perceived problem behaviours in dogs are associated with higher rates of dog relinquishment

A common cause of dog relinquishment is dogs’ problem behaviours and owners’ responsibility constraints. A 2005 study in the UK found that the most common reason for dog relinquishment was problematic behaviour, followed by the dog requiring more attention than the owner could provide (Diesel et al. Reference Diesel, Brodbelt and Pfeiffer2010). Problem behaviours are behaviours found to be troublesome for the owner, which may not necessarily be abnormal for the animal (Pirrone et al. Reference Pirrone, Pierantoni, Mazzola, Vigo and Albertini2015).

Level 2 predictors

H2. Dogs acquired from kennels are associated with lower problem behaviours

Studies have traced the causes of problem behaviours in dogs. One of which is the dog’s channel of acquisition. Research in Italy has found that dogs purchased from pet stores typically display more aggression and problem behaviours (Pirrone et al. Reference Pirrone, Pierantoni, Pastorino and Albertini2016). A review encompassing North America, Europe, and Australia has shown that dogs from commercial breeding establishments sold to consumers through pet stores are more likely to have behavioural or emotional problems (McMillan Reference McMillan2017). Dogs from pet stores exhibit more problem behaviours because they are more likely to be outlets of ‘puppy mills’. With inadequate regulatory oversight and thus low welfare standards, those unlicenced breeders treat dogs as commodities (Croney Reference Croney2019). They are prone to breeding irresponsibly, leading to more genetic defects and inherited diseases (Arman Reference Arman2007). Stressful early life experiences, such as early weaning and maternal separation by unethical breeders, increase the risk of animal anxiety and mood disorders (McMillan Reference McMillan2017). Inadequate or inappropriate early-life stimuli, social exposure, transport, and pet-store environments contribute to problems, such as social fearfulness (Harvey et al. Reference Harvey, Craigon, Blythe, England and Asher2016; Rooney et al. Reference Rooney, Clark and Casey2016; Puurunen et al. Reference Puurunen, Hakanen, Salonen, Mikkola, Sulkama, Araujo and Lohi2020). Animal welfare groups in Taiwan also encourage purchasing directly from kennels where breeding conditions are more transparent (Environmental & Animal Society of Taiwan 2022).

H3. Higher use of punishment training methods is associated with more problem behaviours

A potential contributor to problem behaviours is the owners’ training methods (Blackwell et al. Reference Blackwell, Twells, Seawright and Casey2008). Training methods can be classified as either punishment or rewards, with the former compromising welfare without benefiting obedience (Hiby et al. Reference Hiby, Rooney and Bradshaw2004; Deldalle & Gaunet Reference Deldalle and Gaunet2014). The use of punishment is culturally more common in Taiwan, not only as a response to dogs’ unpleasant behaviours (Shih et al. Reference Shih, Chang, Descovich, Liang, Chou and Lin2023), but even to children in schools and at home (Lin Reference Lin2020). Frequent use of punishment leads to anxiety and fear in smaller dogs, and increased aggression and excitability in all dogs (Arhant et al. Reference Arhant, Bubna-Littitz, Bartels, Futschik and Troxler2010). Rewards, on the other hand, result in dogs that perform better in novel training tasks and in their ability to learn (Rooney & Cowan Reference Rooney and Cowan2011). Studies have suggested that improved training methods may help reduce problem behaviours, which may ultimately lower the risk of dog relinquishment (Protopopova & Gunter Reference Protopopova and Gunter2017).

Level 3 predictors

This study further examines two additional factors relating to the owner which may be linked to dog relinquishment: the owner’s dog acquisition motivation and their knowledge of dogs.

H4. Impulse and functional-purpose acquisition motivations are associated with higher rates of dog relinquishment, while positive dog affection and companionship motivations are associated with lower rates

Holland and coauthors (Reference Holland, Mead, Casey, Upjohn and Christley2022) have suggested three overarching motivations for why people want dogs — self-related, social-based, and dog-related positive affect-based motivation, but the study did not explore their linkage to relinquishment. This study builds upon that classification to examine how the following motivations link to relinquishment: positive dog affection; companionship; functional purposes; and impulse acquisition.

‘Positive dog affection’ relates to the love of dogs (Holland et al. Reference Holland, Mead, Casey, Upjohn and Christley2022). Research suggests that owners with this motivation appreciate pets for their intrinsic traits and their innate intelligence — seeing the relationship as a two-way interaction between two intelligent entities and taking responsibility for a dog’s needs (Beverland et al. Reference Beverland, Farrelly and Lim2008). Therefore, we hypothesise that owners who acquired dogs with this motivation are associated with lower rates of relinquishment.

‘Companionship’ means acquiring dogs as companions, which is the most popular reason for dog acquisition in many countries (Endenburg et al. Reference Endenburg, Hart and Bouw1994; Packer et al. Reference Packer, Brand, Belshaw, Pegram, Stevens and O’Neill2021; Holland et al. Reference Holland, Mead, Casey, Upjohn and Christley2022). This includes the friendship and love of companionship and the benefits to health and well-being in the ‘self-related’ motivations identified by Holland et al. (Reference Holland, Mead, Casey, Upjohn and Christley2022). Companionship is not only for the pet owner but also for family and friends or for other animals. Since companionship is an intrinsic motivation that fosters a more mutual relationship between humans and dogs (Beverland et al. Reference Beverland, Farrelly and Lim2008), we hypothesise that owners acquiring dogs with companionship motivation are associated with lower rates of relinquishment.

‘Functional purposes’ mean acquiring the dog for a working role, such as security, herding, assistance, or breeding (Packer et al. Reference Packer, Brand, Belshaw, Pegram, Stevens and O’Neill2021). While Holland et al. (Reference Holland, Mead, Casey, Upjohn and Christley2022) group companionship and functional purposes together as a single motivation, emotive and rational motivations are suggested to have different implications for the human-animal bond in Taiwan (Chen Reference Chen2001). Therefore, they are analysed separately in this study. We hypothesise that those who acquire dogs for functional purposes have a higher risk of relinquishment.

Some owners’ dog acquisition may be less deliberated but committed on impulse, without fully understanding the necessary time, energy, and financial obligations. Such owners are more likely to have acquired their dog in their only store visit, buying for the first time, an impulse purchase driven by a ‘cute response’ (Holland Reference Holland2019). Worse, impulse purchases result in ‘new pet owner ignorance’ (Matthew Reference Matthew2018). A study in Taiwan finds that “…many Taiwanese dog owners harbor unrealistic expectations of the time, effort, and space required to keep dogs and that they lack basic knowledge of dog behavior” (Hsu et al. Reference Hsu, Liu Severinghaus and Serpell2003; p 18). Since such owners often lack or have little research prior to dog acquisition, this suggests that impulse-motivated acquirers are likely to be less knowledgeable about dogs and less prepared for the commitment required for pet-keeping.

H5. Owners with lower dog knowledge are associated with higher rates of dog relinquishment

This study also examines the relationship between owners’ knowledge of dogs and relinquishment. Dog-keeping requires knowledge and skills (Jagoe & Serpell Reference Jagoe and Serpell1996). Insufficient knowledge of animal needs may lead to poor animal keeping and welfare (Matthew Reference Matthew2018). For example, dog aggression toward children may be due to misinterpreting canine body language or disregarding fear signals due to insufficient knowledge of dog behaviour and risks (Reisner & Shofer Reference Reisner and Shofer2008). Unknowledgeable dog owners may also be unaware of the behaviour training and therapy that can help address behavioural problems (Wells & Hepper Reference Wells and Hepper2000). Consumers with a higher level of knowledge may be more informed of their responsibilities and better able to deal with dogs’ problem behaviours and, therefore, be less likely to relinquish dogs; conversely, consumers with a lower level of knowledge may reflect unpreparedness and have a harder time dealing with problem behaviours, thereby increasing the likelihood of relinquishment.

In summary, this study explores the root causes of dog relinquishment in Taiwan by proposing a model that traces the pathways leading to relinquishment. Regression models will be used to examine which of those factors explain dog relinquishment in isolation, as well as in the presence of other explanatory factors.

Materials and methods

Survey and ethical considerations

Responses were collected from dog owners using an online survey. Respondents were informed that the study aimed to examine their dog ownership, that the survey was for the purposes of academic research, their data would remain confidential and anonymous, they could withdraw from the study at any time, and they could ask questions via the provided email address. Since this survey is anonymous, involves no human interaction or intrusion, and does not target vulnerable or sensitive groups, an ethical review is not required under local regulations (NTU 2025).

Participants

The survey was collected online by distributing its link with the data amounting to a convenience sample with 461 collected responses, of which 444 valid samples were used in the analysis. Invalid samples include responses involving cats or mixing pets. Two hundred and eighty-six samples were collected by the authors from pet shops, kennels, and pet-owner groups, with no incentive offered to participants. The link was distributed to pet-owner groups via Facebook, Dcard (a popular forum in Taiwan), and LINE (a popular chatting app). Pet shops and kennels were invited to distribute the survey to their customers. However, pet shops have been less co-operative than kennels, possibly due to concerns that the research could cast them in an unfavourable light, since pet shops have been linked to sourcing problematic dogs and encouraging impulse purchases (Pirrone et al. Reference Pirrone, Pierantoni, Pastorino and Albertini2016). A survey agency specialising in conducting online panel surveys was hired to boost the study data with 175 samples from dog owners, who are incentivised with points that can be converted into commercial vouchers. These responses are analysed together and not treated differently.

Questionnaire design and analysis

The questionnaire was developed by the co-authors. The survey includes a mix of single- and multiple-choice questions, adapted from previous studies that have operationalised the concepts proposed. All the questions ask about the owners’ most recently relinquished dog, or for those who have not relinquished any dog, their most recently acquired dog.

The questions on dog relinquishment are from Weng (Reference Weng and Kass2006a). The questionnaire asks whether the dog owner has relinquished or abandoned a dog for any reason in the past five years, explained as giving their dog away, whether to animal shelters, friends, family, or relatives. Respondents who have relinquished any dog were asked to provide the reasons for relinquishing their most recently relinquished dog, selecting from the following multiple-choice options: lack of time; moving; dog problem behaviours; or illness of the owner or owner’s family. They also had the option of providing an open-ended response. Five respondents did so, but all their responses could be categorised into one or more of the listed reasons.

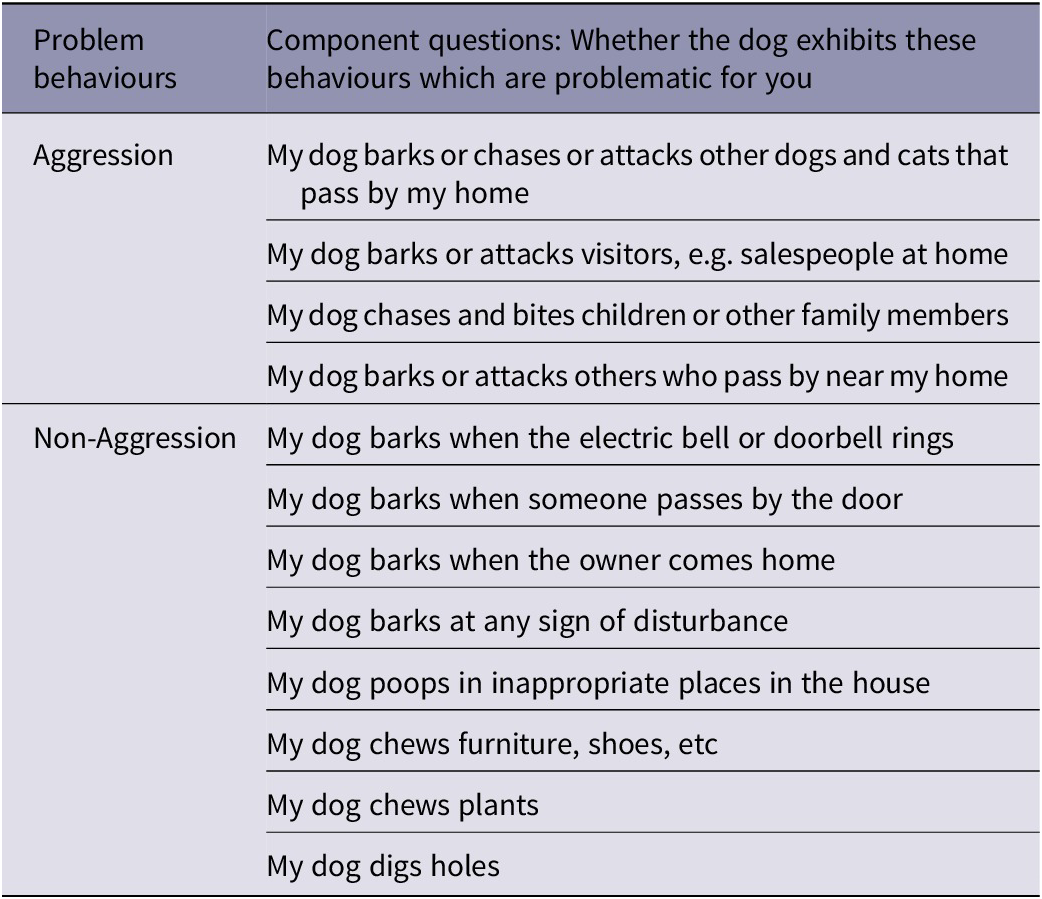

The questions on problem behaviours (See Table 1) are from Chen’s study in Taiwan (Reference Chen2001), capturing problem behaviours often reported in the local context. It is formulated as ‘whether the dog exhibits these behaviours which are problematic for you’. Each component problem is scored as one if it exists and zero if it does not and summed up across the questions. A score for problem behaviour is calculated, along with sub-scores for behaviours involving aggression and those that do not, since aggression is considered more problematic for owners (Herwijnen et al. Reference Herwijnen, Van Der Borg, Naguib and Beerda2018) and is more likely to lead to relinquishment (Casey et al. Reference Casey, Loftus, Bolster, Richards and Blackwell2014). Aggression involves more hostile actions, such as attacking, biting, or confrontational barking, compared to non-aggressive behaviours, such as inappropriate defaecation, chewing, or barking. These follow Chen’s (Reference Chen2001) classification, though specific reliability measures were not provided in that particular study.

Table 1. Questions used to assess aggressive and non-aggressive problem behaviours observed by dog owners (n = 444) taking part in a survey on dog ownership and relinquishment in Taiwan

The question on the channel of acquisition is based on the most typical channels in Taiwan (Taiwan Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals 2022). It asks how the person acquired that dog: from a kennel; a pet shop; from friends or family; or adopted (single choice).

The measurement of the training method uses the scale from Arhant et al. (Reference Arhant, Bubna-Littitz, Bartels, Futschik and Troxler2010), who constructed it through Principal Component Analysis (PCA), to measure the propensity for: (1) punishing unwanted behaviour; (2) rewards; (3) other responses to unwanted behaviour. Punishment includes leash jerk, scolding the dog verbally, grasping around the muzzle, slapping with a hand/implement, scruff-shaking/alpha roll, and startling with noise. Rewards include praising verbally, caressing and petting, and rewarding with food and play. Other responses include comfort with petting/speaking, distraction with food/play, or ignoring/time-out. Respondents can answer: never, rarely, sometimes, often, or very often, which is converted to a Likert scale between 0 and 4 and averaged to attain individual scores.

The questions on dog acquisition motivation are adapted from several studies (Holland Reference Holland2019; Packer et al. Reference Packer, Brand, Belshaw, Pegram, Stevens and O’Neill2021; Holland et al. Reference Holland, Mead, Casey, Upjohn and Christley2022). Respondent can select their motivations for acquiring dogs, with multiple choices allowed: (1) for companionship; (2) for exercising together: (3) love for dogs: (4) to protect the family; (5) to secure the home; (6) made the decision to acquire the dog while passing by; or (7) others. The first two choices are companionship motivations, the third is positive dog affection, the next two are functional purchases, and the last one is impulse purchases. They could provide additional explanations for ‘other’ motivations, but no substantive information emerged from these responses.

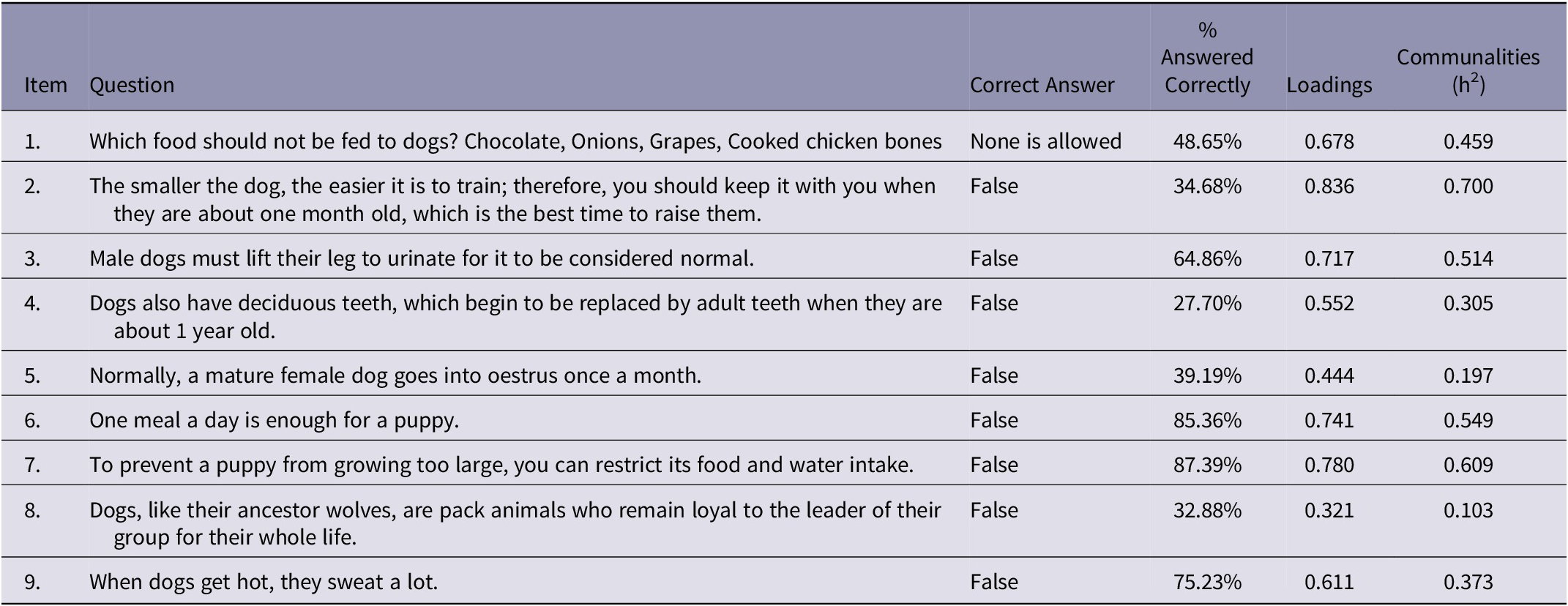

To ensure that the locally promoted and relevant knowledge of dogs is assessed, this questionnaire uses the test bank from Chen’s (Reference Chen2001) study in Taiwan, with two questions (questions 1 and 2 in Table 3) added by us for a total of nine questions. Item Response Theory (IRT), a latent method from psychometrics, is used to calculate the knowledge score and the reliability measure of how well those questions measure knowledge (Baker & Kim Reference Baker and S-H2017).

Analysis

All analyses were performed using R software version 4.4.2, using the R Studio IDE. IRT modelling is carried out using the MIRT package in R (Chalmers Reference Chalmers2012). To examine the cause of relinquishment, the binary variable on relinquishment is used as the dependent variable in logistic regression modelling. Dog owner demographics — age, gender, and educational attainment — are added as controls in the model, as in other studies on relinquishment, because demographics in the sample may potentially influence the results (Pirrone et al. Reference Pirrone, Pierantoni, Mazzola, Vigo and Albertini2015). Dog attributes — whether the dog is raised indoors or outdoors, neutered, sex, and size (Ly & Protopopova Reference Ly and Protopopova2023) — may also be confounded by the risks of relinquishment and thus are also added as controls in the full models. Alpha levels of 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 are reported in the data, with 0.05 considered the threshold for significance.

Results

Respondent profile

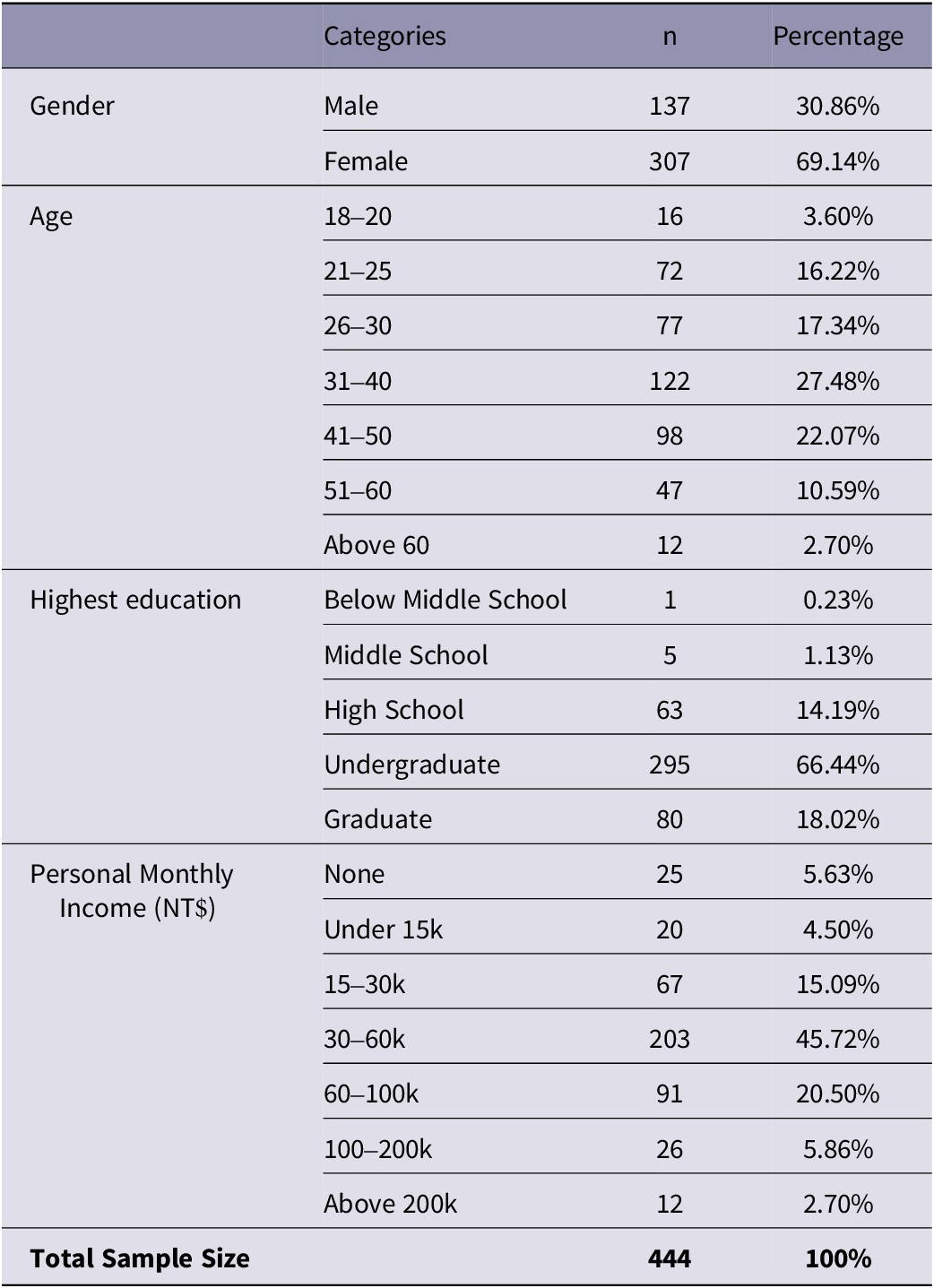

Table 2 provides the profile of the respondents. The sample contains 137 (30.86%) males and 307 (69.14%) females. The sample age ranges from 18 to over 60, with the largest being in the middle-aged 30–50 age group. The most prevalent education level is a college education, and a monthly income of NT$30,000–60,000.

Table 2. Profile of respondents (n = 444) taking part in a survey on dog ownership and relinquishment in Taiwan, including their gender, age group, and level of education and income

Descriptive statistics

The 444 valid samples contain 74 cases of dog relinquishment. The most common reasons given for relinquishment are lack of time (43.4%) and moving (26.3%), followed by problem behaviours (23.7%) and the owner’s illness (17.1%).

The reported channels of acquisition are adoption (34.91%), kennel (24.77%), pet shop (19.14%), and from friends or family (21.17%). Adoption is the most frequently reported channel of acquisition possibly because those who care more about dogs are more inclined to participate in the survey (see Shih et al. Reference Shih, Chang, Descovich, Liang, Chou and Lin2023). Since this study hopes to compare the channels, the goal is to gather sufficient responses from each channel to allow meaningful comparisons, which these data satisfy.

The reported motivations for acquiring dogs are positive dog affection (73.42%), companionship (51.23%), functional (9.68%), and impulse (8.33%).

Assessing knowledge score using IRT

Table 3 shows the correct answers and the percentage of respondents who answered correctly for each component question of dog knowledge. The questions with the lowest correct responses are regarding dogs’ deciduous teeth (27.7% correct) and their loyalty (32.88%). The questions with the highest correct responses are to do with restricting intake to limit the dog’s size (87.39%) and the number of meals a puppy needs to eat per day (85.36%).

Table 3. The questions used to assess owners’ (n = 444) knowledge of dogs in the survey of dog ownership and relinquishment in Taiwan, including their correct answers, the percentage of owners who answered correctly, and the loading and communalities in the IRT model

The nine questions are used to calculate a knowledge score using Item Response Theory (IRT). Loadings reflect each item’s correlation with the latent knowledge factor, while communalities (h2) indicate the variance explained by each question.

The loading and commonalities provide statistics on the calculation of the knowledge score using IRT. The loadings indicate how strongly each item correlates with the underlying knowledge latent factor, while the communalities (h2) show the proportion of variance in each item explained by that question; both metrics validate the knowledge score derived from IRT, which models the relationship between individual responses and latent traits. Three questions from Chen’s (Reference Chen2001) study had a low communality (≤ 0.02), so they were not used to calculate the knowledge score. IRT fit statistics suggest that these questions (from Chen Reference Chen2001) be eliminated from calculation of the knowledge score: (1) when a dog is about 8 months old to 1 year old, its physiological condition reaches complete sexual maturity (True); (2) the normal body temperature of dogs is higher than that of humans, about 39°C (True); (3) the psychological maturity age of a puppy is 2–3 years old (True).

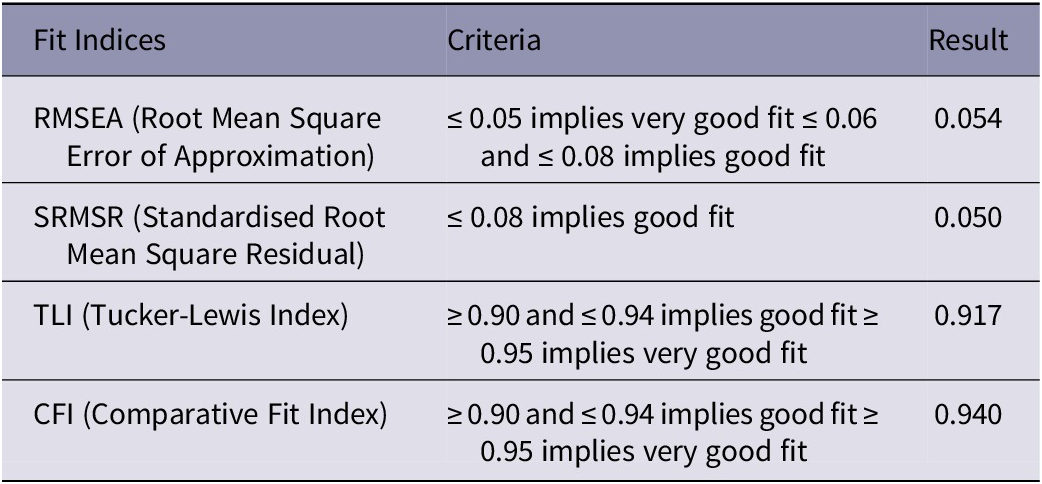

IRT produces a normalised variable on the respondent’s knowledge score. While scholars acknowledge there is no universal cut-off for IRT model fit, the fit indices of the knowledge score in Table 4 demonstrates an overall good fit (Gana & Broc Reference Gana and Broc2019; Kline Reference Kline2023).

Table 4. Model fit of the calculation of the dog knowledge score of the dog owners (n = 444) taking part in a survey on dog ownership and relinquishment in Taiwan

Tracing the causes of relinquishment

Level 1. Factors predicting relinquishment

Firstly, we examine whether problem behaviours explain dog relinquishment (H1). Multiple regression models with varying sets of independent variables are used to assess the effects of each variable both individually and in combination with others. This approach helps determine: (1) whether an independent variable significantly influences the dependent variable on its own; and (2) whether this effect remains after controlling for other variables that may better explain the outcome.

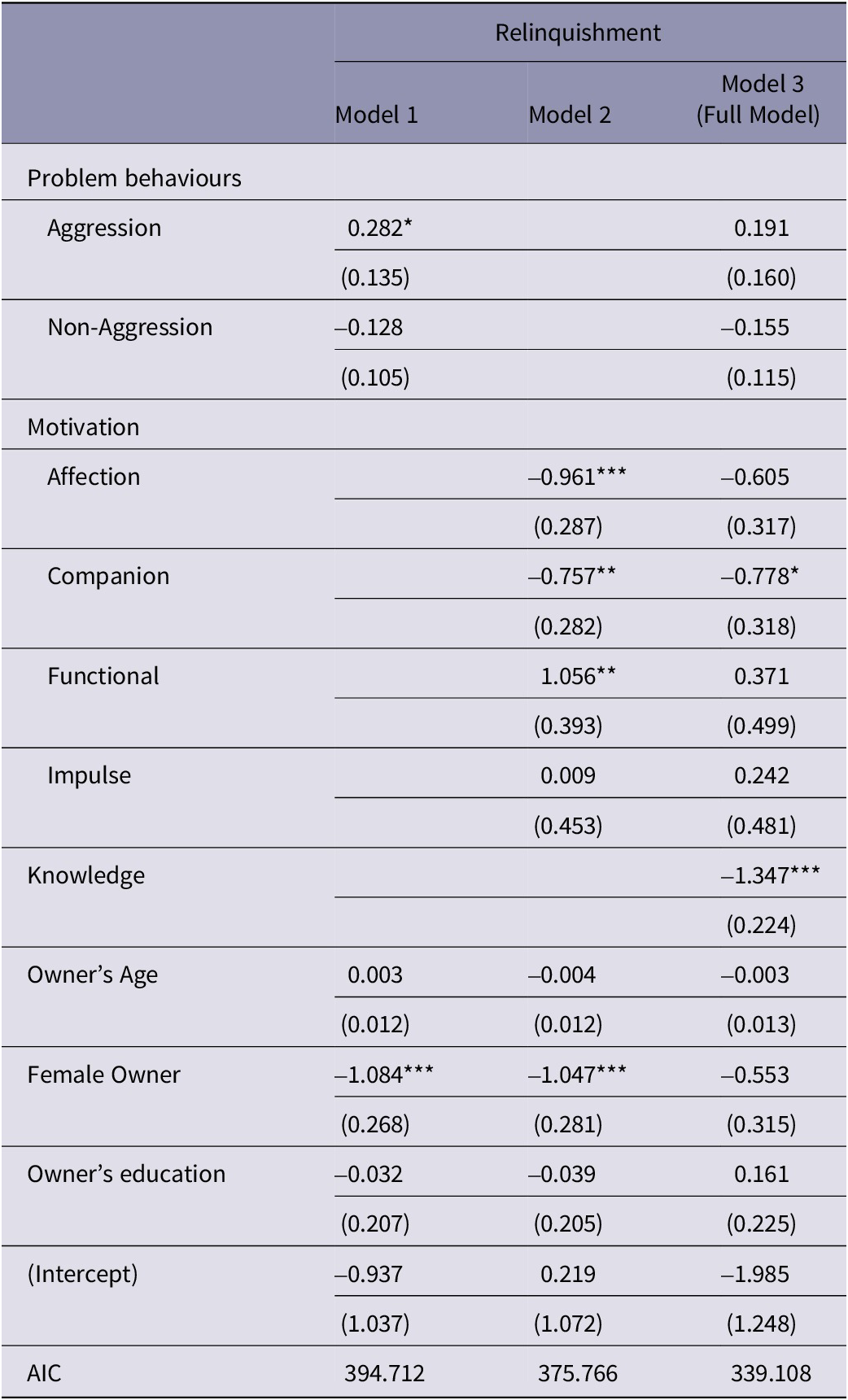

Table 5 shows the three models with different sets of independent variables to analyse their association with the dependent variable — dog relinquishment, along with the estimated coefficient, standard error (in parentheses), P-values (the asterisks). Model fit is provided using AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) since this is a logistic regression model. Model 1 examines whether problem behaviours in isolation relate to relinquishment, with age, gender, and educational attainment controlled. The results show that aggression problem behaviours are significantly associated with relinquishment (P < 0.05), while non-aggression behaviours are not.

Table 5. Estimated coefficients (standard error) from regression models examining factors associated with regression models examining the factors associated with dog relinquishment in a survey of dog owners in Taiwan (n = 444)

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

Model 3 also controls for dog attributes including indoor, neutered, sex, and breed size (S, M, L), which are not shown as none is significant.

Next, we examine whether motivation in isolation explains dog relinquishment through model 2. The result shows that pet owners’ motivations strongly influence relinquishment. Those who acquired dogs with affection (P < 0.001) and companionship motivations (P < 0.01) are less likely to relinquish them, while those acquiring dogs for functional purposes are significantly more likely to do so (P < 0.01). These support our hypotheses on the relationship between motivation and relinquishment (H4). However, those who acquired on impulse show no significantly higher risk of relinquishment, relative to other motivations.

Model 3 is the full model with all the dependent variables present — problem behaviours, pet-owners’ motivation, and knowledge — to examine which variables provide the greatest explanatory power, while controlling for owner demographics and dog attributes. Since none of the variables on dog attributes are significant, their regression coefficients are not shown in the reported table for brevity. The results show that higher knowledge (P < 0.001) and higher companionship motivation (P < 0.05) are associated with lower rates of relinquishment after accounting for all the variables.

Together, these three models allow us to better understand the underlying factors that influence relinquishment. Model 1 shows that dogs’ problem behaviours are associated with higher rates of relinquishment, which is consistent with previous studies (Herwijnen et al. Reference Herwijnen, Van Der Borg, Naguib and Beerda2018). However, this relationship is severely weakened in the presence of knowledge and motivation. Model 2 shows that dog owners’ motivations also show a strong association with relinquishment which is in accordance with previous studies (Holland Reference Holland2019; Packer et al. Reference Packer, Brand, Belshaw, Pegram, Stevens and O’Neill2021; Holland et al. Reference Holland, Mead, Casey, Upjohn and Christley2022), but only companionship remains significant in the full model (model 3). Since knowledge remains highly significant even in the presence of other variables in the full model, there is no need to run a standalone model to examine in isolation the influence of knowledge on relinquishment. While the known explanation that problem behaviours are associated with a higher rate of dog relinquishment is supported (H1), companionship motivation (H5) and owners’ knowledge (H4) have a more powerful influence. Therefore, this study highlights that dog knowledge and companionship motivation provide a stronger explanation for dog relinquishment than problem behaviours in Taiwan.

Level 2. Factors predicting problem behaviours

Studies suggest that dog problem behaviours are, in turn, influenced by the channel and training methods. Knowledge and motivation may potentially also have an influence on the channel of acquisition and training used. To understand this pathway, we will go one level deeper to examine the underlying factors associated with dogs’ problem behaviours.

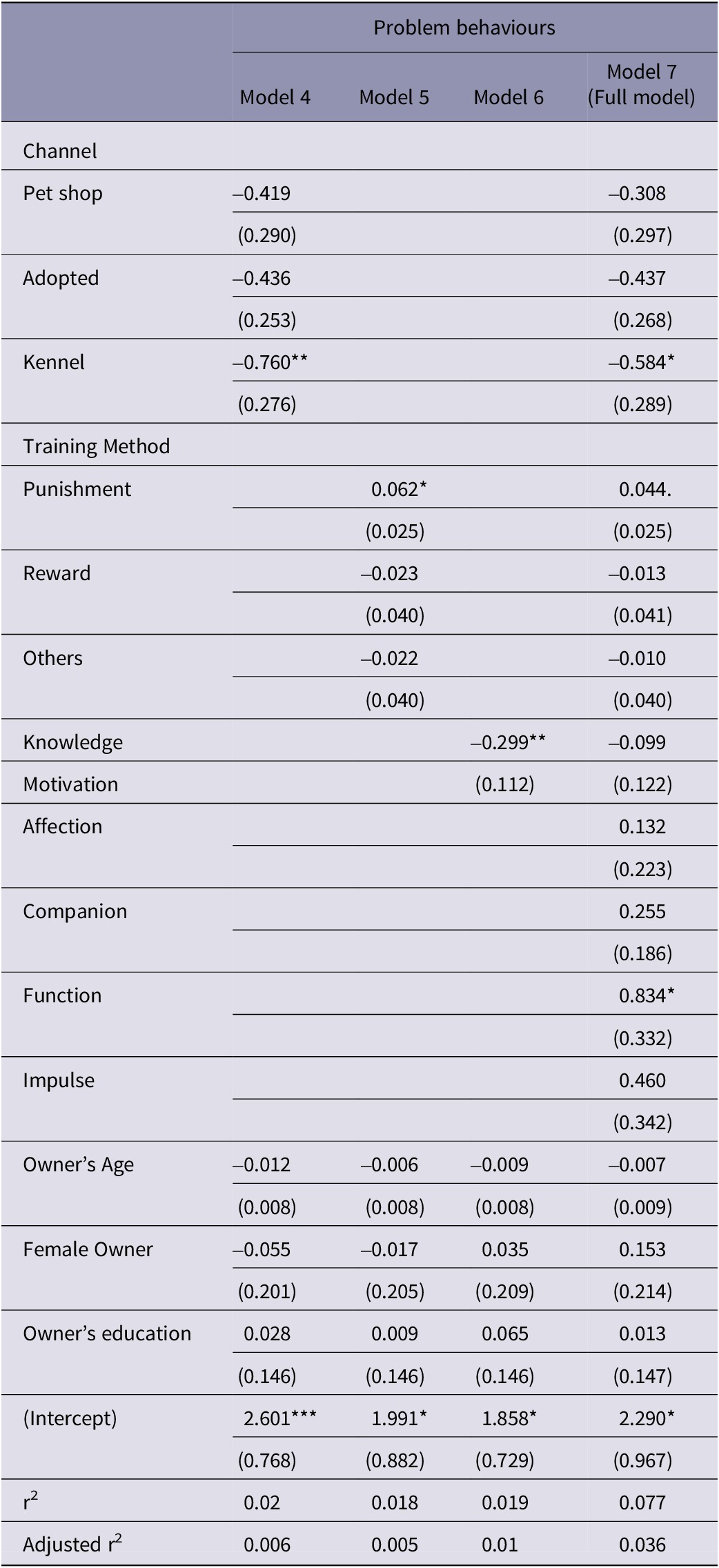

To examine whether dogs from certain channels exhibit more problem behaviours (H2), we regress problem behaviours on the channel of acquisition. In Table 6, model 4 reveals that dogs acquired from kennels are least likely to exhibit problem behaviours (P < 0.01), compared to adopted dogs, pet shops, and the reference category of dogs from friends or family members.

Table 6. Estimated coefficients (standard error) from regression models examining factors associated with regression models examining the factors associated with the perception of dog problem behaviours in a survey of dog owners in Taiwan (n = 444)

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

Model 7 has controlled for dog attributes, including indoor, neutered, sex, and breed size (S, M, L), which are not shown as none are significant.

To address whether training methods relate to problem behaviours (H3), model 5 regresses problem behaviours on training methods, controlling for owner characteristics. Training through punishment is indeed associated with increased problem behaviours (P < 0.05). Other methods slightly reduce problem behaviours but are not statistically significant.

The relationship between owners’ knowledge and dogs’ problem behaviours is examined in model 6. Higher dog knowledge is significantly associated with lower problem behaviours (P < 0.01). All else being equal, more knowledgeable dog owners are less likely to perceive that their dogs have problem behaviours. Therefore, problem behaviours remain linked to the owner — as they are behaviours perceived as problematic by the owner (Pirrone et al. Reference Pirrone, Pierantoni, Mazzola, Vigo and Albertini2015).

To examine which of these factors offer the most explanatory power, we run model 7 (the full model) with problem behaviours as the dependent variable, with the channel of acquisition, training methods, knowledge, and motivation as independent variables, controlling for owner demographics and dog attributes. Kennels (P < 0.05) and functional motivation (P < 0.05) are the two variables that remain significant. Dogs acquired from kennels remain significantly less likely to exhibit problem behaviours. Owners with functional motivations are also linked to an increased perception of problem behaviours, suggesting that owners acquiring dogs for work have different expectations of dogs’ behaviour (Chen Reference Chen2001).

These models provide a nuanced answer to our research questions. In support of recommendations from animal welfare groups, dogs from kennels are indeed the more trusted source of dogs, suggesting that they do provide more responsible breeding and early care (Environmental & Animal Society of Taiwan 2022). This is demonstrated by their lower reported problem behaviours even in the full model (H2). Punishment-based training method indeed backfires, supporting existing research that it leads to subsequent behavioural issues (Arhant et al. Reference Arhant, Bubna-Littitz, Bartels, Futschik and Troxler2010), but punishment becomes insignificant in the full model, suggesting there are other, stronger explanations, such as functional motivation (H4).

Curiously, knowledge in isolation reduces the perception of problem behaviours in model 6 but is no longer significant in the full model. We will turn to this in the next section.

Level 3. Factors predicting the channel of acquisition and training methods

Up to this point, the standalone models have reaffirmed existing explanations, yet the full models demonstrate that, in many cases, the outcome variables are better explained by motivation and knowledge. Hence, we continue to trace down the path to examine whether channel and training methods may also be linked to motivation and knowledge. The previous analysis has shown that problem behaviours are associated with punishment-based training and least associated with acquisition from kennels. Hence, we regress those two factors on motivation, knowledge, dog attributes, as well as owner demographics.

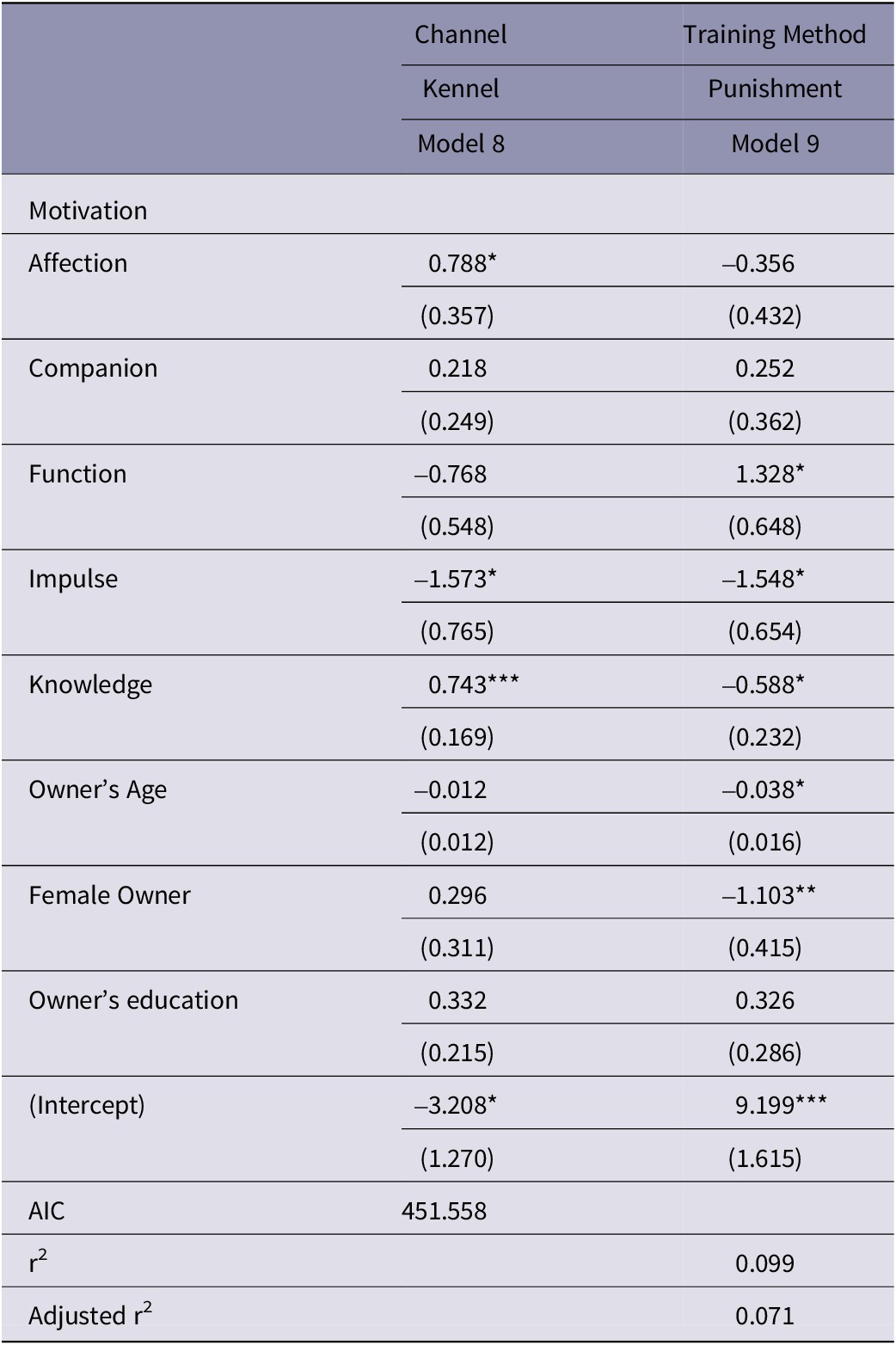

In Table 7, model 8 shows the regression with kennel as the dependent variable. Since whether the dog is acquired from a kennel is a binary variable, logistic regression is used. The results show that higher knowledge (P < 0.001), affection motivations (P < 0.05), and lower impulse purchases (P < 0.05) are associated with acquisition from kennels. This is consistent with previous studies, which suggest that brachycephalic owners (i.e. owners of flat-faced breeds often prone to health and behavioural issues) are more likely to use puppy-selling websites to find their dog, less likely to see either parent of their puppy, and less likely to request health records (Packer et al. Reference Packer, Murphy and Farnworth2017). This study contributes by tracing those factors to knowledge and motivation — more knowledgeable owners with proper motivations are more likely to purchase from more reliable channels and perceive fewer problem behaviours.

Table 7. Estimated coefficients (standard error) from regression models examining factors associated with regression models examining the factors associated with acquiring dogs from kennels and the use of punishment as a training method in a survey of dog owners in Taiwan (n = 444)

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

Both models controlled for dog attributes including indoor, neutered, sex, and breed size (S, M, L), which are not shown as none is significant.

Model 9 regresses punishment-based training using linear regression. Punishment is less likely to be used by owners with higher knowledge (P < 0.05) and impulse acquisitions (P < 0.05), but more likely to be used by owners motivated by functional purposes for dog-keeping (P < 0.05). This demonstrates that the training method used is also ultimately associated with owners’ knowledge and motivation.

Discussion

Firstly, dogs purchased from kennels and kept by owners with better training methods exhibit fewer problem behaviours; results that are consistent with other studies (Blackwell et al. Reference Blackwell, Twells, Seawright and Casey2008; McMillan Reference McMillan2017). In light of recurring scandals surrounding pet shops sourcing from unlicenced breeders (Taiwan Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals 2022), other countries have seen greater success in regulating such practices (Arman Reference Arman2007). For example, buyers in the UK are encouraged to purchase puppies directly from licenced kennels after observing the mother (Hesmondhalgh Reference Hesmondhalgh2013), ensuring greater transparency and better welfare standards (Harvey et al. Reference Harvey, Craigon, Blythe, England and Asher2016; Mai et al. Reference Mai, Howell, Benton and Bennett2021). A notable example is Lucy’s Law, passed in England in 2019, which mandates that pet sales occur only through licenced breeders or adoption centres where prospective owners can see the mother and the living conditions of the puppies (Environmental & Animal Society of Taiwan 2022). Advocates have recommended adopting a similar law in Taiwan to disrupt the supply chains of unethical dealers, prevent the sale of puppies from puppy mills or illegal imports, and make it more difficult for unlicenced breeders to access retail outlets. Dogs from reputable breeders generally experience better conditions, underscoring the need for comprehensive legislative reforms. Strengthening Taiwan’s breeding and sales regulations can promote responsible acquisition, improve animal welfare, and reduce the prevalence of unethical breeding practices.

Secondly, while previous research has identified factors contributing to relinquishments, such as problem behaviours (Wells & Hepper Reference Wells and Hepper2000), problematic acquisition channels (McMillan Reference McMillan2017), and training methods (Protopopova & Gunter Reference Protopopova and Gunter2017), this study finds that the owners’ knowledge and motivation mitigate those problems and better explain relinquishment.

While problem behaviours are associated with relinquishment (in support of H1), this factor becomes insignificant in the full model (Model 3), as relinquishment is better explained by owners’ motivation (H4) and knowledge (H5). Although problem behaviours also relate to the channel of acquisition (H2), those who choose kennels in Taiwan are more likely to have the highest dog knowledge and the motivation of affection rather than impulse. Hence, owners with the proper knowledge and motivation are more likely to buy from kennels, where dogs have lower problem behaviours. Likewise, while problem behaviours also relate to punishment training (H3), punishment is associated with owners with lower knowledge, higher functional motivations, and lower impulse purchases. While respondents who have not relinquished their dog may still relinquish them in the future — a limitation of this research design — the identified risk factors associated with those who have relinquished their dog are still informative for identifying the factors are associated with increased risks of relinquishment.

The underlying factor that best predicts dog relinquishment is owners’ knowledge and motivation, demonstrating how these accumulated skills and internalised values shape acquisition and ownership behaviours (Li Reference Li2025). These findings highlight the importance of addressing dog relinquishment at its root — through improved owner education.

In Taiwan, public awareness of animal welfare remains limited. Many have limited knowledge of existing regulations (Weng et al. Reference Weng and Kass2006b), and even veterinarians report insufficient training in animal welfare (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Lai, Fei and Jong2015). In 2017, only 62% of dogs and cats in Taiwan were registered, and the neutering rate stood at just 50% (Chen Reference Chen2018), underscoring gaps in public engagement and responsibility. To address this, animal welfare advocates and policy-makers have proposed incentives, such as free vaccinations and healthcare support, to promote microchipping and neutering (National Development Council 2021), which have been shown to reduce stray animals (Dias Costa et al. Reference Dias Costa, Martins, Cunha, Catapan, Ferreira, Oliveira, Garcia and Biondo2017). Strengthening public education is crucial not only in improving pet-keeping practices but also in helping foster long-term commitment to animal welfare (Weng et al. Reference Weng and Kass2006a; Shih et al. Reference Shih, Chang, Descovich, Liang, Chou and Lin2023). Initiatives such as puppy classes may help owners build essential knowledge and develop learning habits, promoting responsible ownership and healthy dog socialisation.

Animal welfare implications

This study addresses the deeper causes of unsuccessful pet ownership, highlighting the critical animal welfare implications of dog relinquishment in Taiwan. While many risk factors are interrelated, the findings emphasise the need for earlier interventions upstream, as current efforts focus primarily on managing dogs after relinquishment. Strengthening regulations on breeding and sales is essential to curb unethical breeding practices, while enhancing public education on responsible dog ownership and welfare can reduce the prevalence of problem behaviours. Together, these measures can prevent relinquishment at its source and improve long-term animal welfare outcomes.

Conclusion

This study suggests that, beyond supporting animal shelters and managing post-relinquishment issues, there is a broader need for cultural change in dog ownership practices. We have found that the factors contributing to dog relinquishment are ultimately traced back to the owner, whose actions can play a pivotal role in the pathway. Owners’ knowledge and motivation can mitigate key contributory factors, reducing the likelihood of problem behaviours, improper training methods, and poor acquisition choices. Consequently, enhancing public education is crucial to lowering relinquishment rates and improving animal welfare.

Secondly, this study suggests that stricter channel regulation could be helpful in Taiwan. Although Taiwan was among the earlier countries in Asia to implement animal welfare legislation and laws against animal cruelty, the rise of unethical breeders, fuelled by commercial demand and weak regulatory enforcement, continues to supply pet shops with dogs that often face health and behavioural issues. This study finds that dogs acquired from kennels are less likely to exhibit problem behaviours and are more likely to be purchased by knowledgeable owners. Implementing stricter regulations on pet breeding and sales, along with improved public education, could improve animal welfare in Taiwan.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted without any external funding.

Competing interests

None.