Palmyra, an Oasis City in the Sea of the Syrian Desert

Palmyra, ancient Tadmor, situated in the Syrian Steppe Desert midway between the Mediterranean to the west and the River Euphrates to the east, has for centuries been a subject of study – both scholarly and more broadly speaking – due to its monumental, almost exclusively Roman-period ruins as well as its rich corpus of art and inscriptions – most of which also date to the first three centuries AD. However, over the last decade the city has received renewed attention in scholarship, both as a result of the war in Syria and the destruction which Palmyra, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1980, has suffered during the conflict, and also because the city’s archaeology and history have been the focus of several research projects within which Palmyrene material and written culture of all kinds has been collected, analysed, re-evaluated and discussed over the last decade.Footnote 1

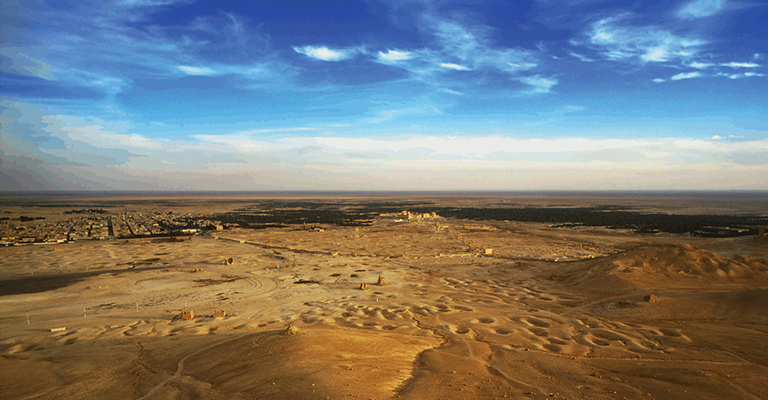

Palmyra, located in an oasis with the Efqa Spring as its main, but not only, source of water, became a central node in the global trade networks rapidly developing during the first three centuries AD. It is also from these centuries that most of the archaeological evidence from the site stems. There is no other site in the region which has yielded as rich a material and written record as Palmyra has, a heritage which give us a detailed insight into the complex society of Palmyra in the Roman period (Figure 1.1). Human activity at and around Palmyra, however, reaches far back into the prehistoric periods.Footnote 2 But not much is known about the extent of the human settlement in these early periods, and even the Hellenistic period remains quite elusive in the archaeological record, despite the fact that research in recent decades has brought more evidence to light, which underlines that the settlement might have been more substantial than hitherto known.Footnote 3

Figure 1.1 View of Palmyra with the oasis in the background.

Palmyra was known empire-wide in antiquity as well; for example, Pliny the Elder writes about it in his Natural History, although he never visited the city himself but based his description on other ancient authors:

Palmyra is a city famous for its situation, for the richness of its soil, and for its agreeable springs; its fields are surrounded on every side by a vast circuit of sand, and it is as it were isolated by nature from the world, having a destiny of its own between the two mighty empires of Rome and Parthia, and at the first moment of a quarrel between them always attracting the attention of both sides.Footnote 4

This very famous quotation about the splendid oasis city succinctly describes its situation. A situation that is reflected in the archaeology and written sources from the city – which, although overwhelmingly in Palmyrene Aramaic, also contain a rich corpus of Greek and bilingual inscriptions – as well as in its art, which shows a strong awareness of contemporary trends in both Roman and Parthian art.Footnote 5

Palmyra is rich in material evidence and inscriptions from the Roman period, despite the fact that the city was sacked twice by Roman troops, in AD 272 and 273, as well as being inhabited in the post-Roman periods, with much material being reused and the local limestone burned for slaked lime for new building projects.Footnote 6 However, the rich surviving material record is so abundant – with more than 3,000 inscriptions and 4,000 portraits as well as several hundred funerary monuments, tower tombs and underground tombs dotting the landscape around the urban core, in addition to monumental building complexes in the city itself – that until recently it had not been synthesized in any comprehensive way.Footnote 7

According to new calculations, Palmyra covered about 140 hectares at its greatest extent; however, only a small part has been investigated in any archaeological detail.Footnote 8 Most attention has been given to the exploration of either the monumental funerary monuments, the so-called tower tombs and the underground graves (hypogea), or the urban monuments, the sanctuaries and the public spaces.Footnote 9 So while we have a fairly good overview of the overall development of the site, in particular in the first three centuries AD,Footnote 10 we in fact do not know much about, for example, the domestic architecture of the city or the post-Roman periods in general.Footnote 11 Only in the last few years has there been a greater focus on private houses and the late antique and later periods overall, leaving us with a skewed image of the city and its development.Footnote 12

Systematic archaeological research at the site has been undertaken since the early twentieth century, but as early as the seventeenth century visitors brought objects from the site back with them to their home countries.Footnote 13 This ‘culture’ tourism intensified in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and under the Ottoman Empire numerous Western travellers visited Palmyra. From the middle of the nineteenth century onwards, interest in the architecture and art of Palmyra intensified, and the first European collections of Palmyrene antiquities came into being, some of which – the collections in Istanbul, Paris and Copenhagen – remain the largest to this day.Footnote 14

The first large-scale systematic excavations at the site commenced shortly after the institution of the French Mandate in 1923. Already in 1924, a French mission had begun extensive archaeological work in Palmyra, and their concession was also extended and new ones given to researchers from other European nations to work at the site together with the French.Footnote 15 From 1924, these included the Danish archaeologist Harald Ingholt, who in 1928 published what was, until recently, the most comprehensive monograph on the Roman-period funerary portraits from Palmyra – in Danish, however.Footnote 16

The archaeological work of the 1920s and 1930s focused mostly on large-scale projects, such as the one in which the modern village in Palmyra, located within the temenos walls of the Sanctuary of Bel, was entirely demolished and cleared and the local population moved to new houses outside the core of the ancient site, in order to restore the sanctuary to its Roman-period state.Footnote 17 While the excavations were published, they did not document in any detail the demolition of the village, for example, nor the numerous post-antique phases and the use of the ancient monuments through the millennia.Footnote 18 Ingholt worked for several seasons in the necropoleis around the city and documented more than eighty graves, of which he only published a few.Footnote 19 The history of the archaeology of the site as such still remains to be written in a holistic way and will be a difficult task, since archival material is spread across the world and, in many cases, may have been lost, and the documentation in Syria may not be accessible or exist anymore. However, over recent years, first attempts to tackle the complex excavation histories have been undertaken either on the basis of what is already known or by delving into newly available archival material.Footnote 20

The Second World War brought a halt to archaeological work, and archaeological research at the site was only continued years later, by both Syrian and foreign missions.Footnote 21 The site became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980, and in 2013 it was put on the UNESCO list of endangered World Heritage Sites.Footnote 22

Past Approaches

The city has been much discussed in scholarship within the framework of the Near East or as a case study of a location framed by two even greater powers, Rome and Parthia, and most scholarship has focused on the centuries that we have mentioned, the Roman imperial period.Footnote 23 The research cited in the previous section and other publications, among which the 2021 monograph by Michal GawlikowskiFootnote 24 needs to be singled out, have given entirely new insights into the city’s complex societal structures and its society’s ability to position itself and certain groups within the rapidly developing and highly volatile world around them, with the city playing a pivotal role in the way in which global trade was managed and developed for centuries. Current approaches to the study of Palmyra now include ongoing projects on digital reconstruction and archival work, as well as the application of computational methodologies to the large datasets from the city, which in turn can give overviews of the development as seen through the dating of the buildings and the art as well as the many thousands of inscriptions.Footnote 25

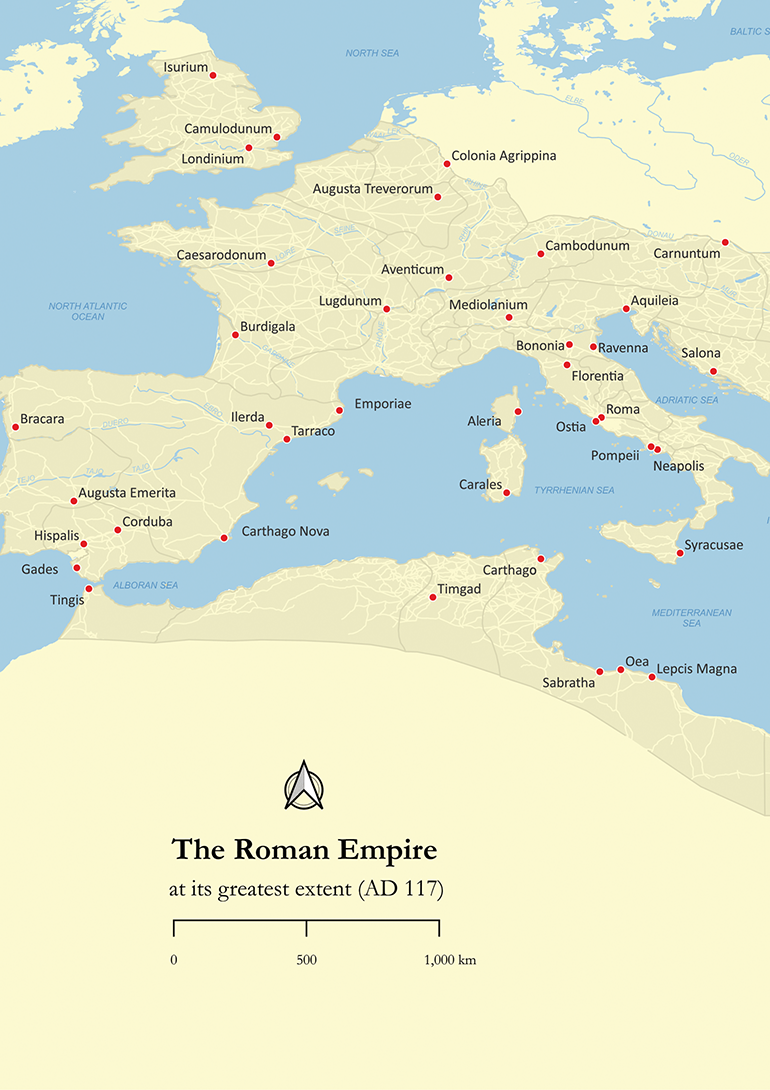

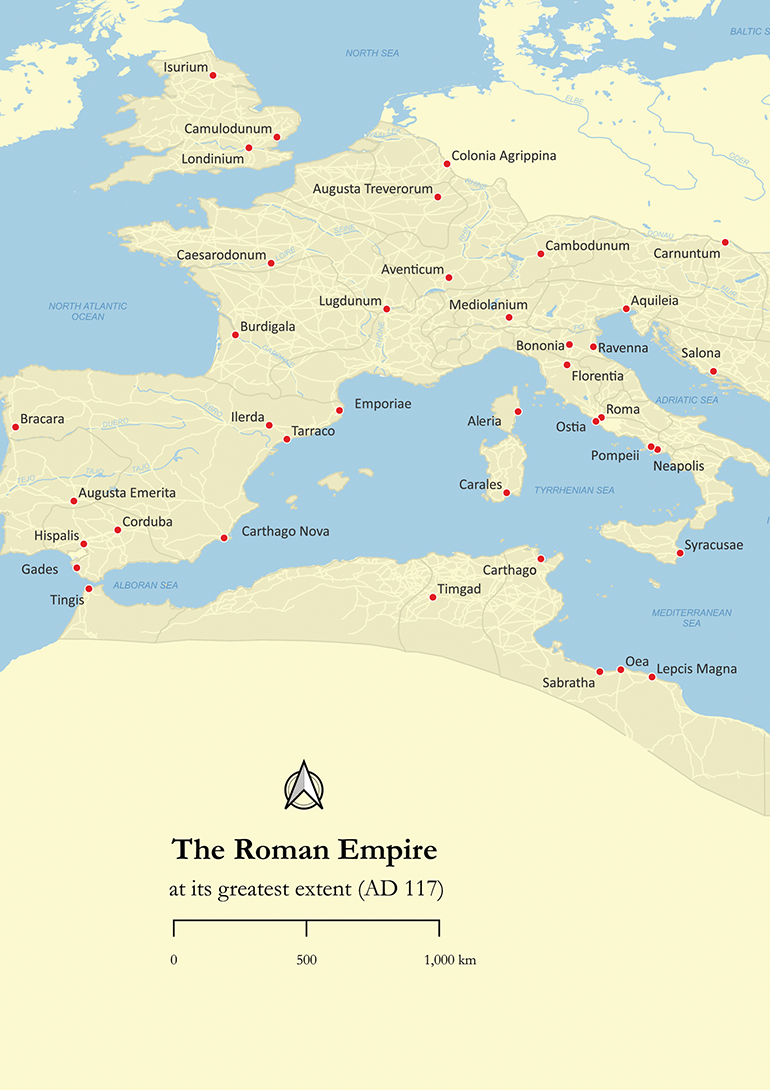

Today, we have an entirely new view on Palmyra and entirely new data and ways in which we can reassess the city’s relationship with the world around it, including the world to the west of Palmyra, namely the Mediterranean world (Map 1.1). Some attention has already been given to the relationship between Palmyra and the eastern regions, relations with Parthia both in terms of trade and cultural exchange, such as that reflected in the artistic traditions in Palmyra.Footnote 26 Furthermore, political relations with the Roman Empire have also been a topic of much research.Footnote 27 Nonetheless, the extent to which the Mediterranean connections has been explored leaves much to be desired in light of the corpora of evidence from the city now available in various forms.Footnote 28

Map 1.1.01Long description

The map emphasises the geographic diversity of the empire, showcasing its reach across Europe, North Africa, and parts of Asia with a clear visual scale of 0 to 1000 kilometres and labelled bodies of water including the Mediterranean Sea, Alboran Sea, North Atlantic Ocean, North Sea, Baltic Sea, Adriatic Sea and the Tyrrhenian Sea. The marked cities include Isurium, Camulodunum, Londinium, Colonia Agrippina, Augusta Treverorum, Caesarodonum, Aventicum, Cambodunum, Carnuntum, Burdigala, Lugdunum, Mediolanium, Aquileia, Bononia, Revenna, Salona, Florentia, Roma, Ostia, Pompeii, Neapolis, Syracusae, Aleria, Carales, Emporiae, Ilerda, Tarraco, Bracara, Augusta Emerita, Corduba, Hispalis, Gades, Tingis, Carthago Nova, Carthago, Timgad, Sabratha, Oea and Lepcis Magna.

Map 1.1.02Long description

The continuation of the map emphasises the regions under the Roman Empire to the east of the Mediterranean Sea and near the Aegean Sea, the Sea of Crete and the Black Sea. The plotted cities include Napoca, Singidunum, Abritus, Nicopolis, Philippopolis, Dyrrachium, Thessalonica, Athenae, Sparta, Byzantium, Pergamum, Smyrna, Ephesos, Nicomedia, Nicaea, Ancyra, Knossos, Gortyn, Pityous, Samosata, Antiochia, Edessa, Palmyra, Dura-Europos, Babylon, Nippur, Uruk, Tripolis, Berytus, Heliopolis, Gerasa, Philadelphia, Caesarea Maritima, Jerusalem, Alexandria, Memphis and Cyrene.

Map 1.1 Palmyra in the Roman Empire.

How Far from Palmyra Was the Mare Nostrum (‘Our Sea’) of the Roman Empire?

Studies taking their point of departure in the geographic region of the Mediterranean have long flourished, going as far back as the monumental work by Braudel.Footnote 29 Large parts of this book were written while he was a prisoner of war in Germany during the Second World War, and ironically, considering the circumstances, it was an attempt to write a universal history of the Mediterranean showing the ways in which regions and their inhabitants were interconnected, despite rivalry, competition and being at war with each other.Footnote 30 Already at that time, others were writing histories of various Mediterranean themes as well, taking their point of departure in the Mediterranean region in one way or another.Footnote 31

In particular in the last three decades, a string of books and articles centring on the archaeology and history of the Mediterranean region, diachronically, regionally and topically, have been published.Footnote 32 Within classical studies, the discourse really took off with the monumental work The Corrupting Sea by Horden and Purcell, which was published in 2000 and still resonates with literature within the broader field. Despite being criticized by some for putting too much emphasis on the concept of micro-regions, we cannot ignore that The Corrupting Sea forced us to think about the ancient world in quite a different geographical manner, pushing the boundaries of how to conceptualize and describe interaction, networks, exchange and connectivity of all sorts through the lens of punctual-event history (histoire événementielle) or from a longue durée perspective – or potentially in a mix thereof. Today, the concept of micro-regions, which was one of main lenses through which Horden and Purcell described the Mediterranean and explained the ways in which it developed, might seem somewhat outdated, but the concept was and still is useful for some regions or ways of studying the past. However, since then new theoretical frameworks have emerged – for example, network studies. Despite not being without flaws, network studies have allowed us to view micro-regions in different ways by examining both weak and strong ties in a variety of networks, which could be fragile but continuous, or strong but broken by singular events such as natural catastrophes or wars.Footnote 33

In the wake of Horden and Purcell’s book, an immense revival of Mediterranean studies and of the Mediterranean as a conceptual study region took off, and we saw a surge in monumental works writing and rewriting various aspects of the archaeology and history of the Mediterranean, which has continued until today.Footnote 34 The Mediterranean realm as a geographic region has become a case study, a lens, a stable factor in research, which seems to be here to stay.Footnote 35 Exactly because such a research lens might persist, we are obliged to keep the discourses and discussions alive and feed these dialogues with evidence that can also push borders. Furthermore, we need to be able to enter critical dialogues about the ways in which we define and discuss the Mediterranean. Since the publication of Horden and Purcell’s monumental work, which was followed up recently by a volume containing some of their most important contributions since the 2000 publication, much has happened to change our modern understanding of the Mediterranean, which makes the study of the Mediterranean even more relevant than it was twenty years ago. The intention with this edited volume is precisely to focus on ‘old’ or already-known evidence as well as on new evidence in a new framework of discussion through the lens or concept of the Mediterranean, the Romans’ Mare Nostrum. In whatever way known evidence can and should be used to set agendas, we need to utilize the deep knowledge that classical studies bring to the world regarding past events from which we can still draw a lot of new knowledge.

Flipping the Map: Resituating Palmyra in the Mediterranean World

However, in order to resituate Palmyra within a broader regional and global framework, it might in fact also be necessary to revisit the site in the light of its numerous relations with the Mediterranean world.Footnote 36 This entails fresh looks at evidence that we, for the most part, already know, but which has not been studied to such ends. Palmyra offers a wealth of material evidence, both archaeological and epigraphic. Much has been written about the site and its various monuments, its sculptural habit, its involvement in trade, its famous Tax Tariff and its religious life.Footnote 37 However, only recently have studies begun to pull together material evidence in new ways in order to use it not as backdrops to narratives but to understand broader historical developments in a new light.Footnote 38 While globalization has been widely discussed in terms of whether it is a useful or less useful term when studying the ancient world, the ways in which a site like Palmyra was indeed directly connected with the Mediterranean world, if at all, has not been discussed at length, nor the ways in which interlinks and entanglements are expressed in the archaeological and historical evidence.Footnote 39 But how do we actually begin to disentangle what evidence, and in what form, needs to be presented in order for us to push forward with detailed studies about the relationship between places and societies seemingly far away from the Mediterranean shores but still a very integral part of the Mediterranean world? This is what the nine contributions in this volume attempt to tackle from very different perspectives and through varying evidence.

The volume opens with the contribution by Eivind Heldaas Seland on ‘The Western Networks of Palmyra’ (Chapter 2). Through a study of the organization of power networks, peer-polity interaction and what he terms shared mental models, Seland draws on the work of the sociologist Michael Mann and uses concepts both from archaeology and New Institutional Economics to explain in what ways Palmyra and the Palmyrenes were able to tap into existing power networks and could even be part of developing them. Jean-Baptiste Yon’s chapter ‘You Can’t Get There from Here: Itineraries of the Palmyrenes in the Mediterranean’ (Chapter 3) focuses on the evidence of Palmyrenes outside of Palmyra and what he terms the discrete evidence, which does not always allow us to reconstruct the actual underlying networks, but which certainly underlines that they were in place and that Palmyrene society was an integrated part – at least to some extent – of the Mediterranean world. He importantly points to what can also be termed weak ties, but ties that were in place potentially only at certain moments or periods of time. Through a set of case studies, Yon gives an overview of what we know of the itineraries of the Palmyrenes towards the West and the Mediterranean, and he shows us byways and shortcuts that are pivotal to our view of the integration of Palmyra into the Mediterranean world. Rubina Raja turns to one of the most enigmatic groups of evidence from Palmyra, namely the so-called banqueting tesserae. These tiny objects hold the widest range of information about the diversity of the religious life of the city, but they also hold an unleashed potential for understanding iconographic trends and fashions in Palmyra – including those imported from other places further west, since they hold a wide range of signet seal imprints. These imprints have never been studied systematically, and in the contribution ‘Palmyrene Iconographic Traditions and Their Mediterranean Connections: A Note on Some Signet Seal Impressions on the Palmyrene Tesserae’ (Chapter 4), the imprints showing female deities in Graeco-Roman style (Tyche, Athena and Nike) are addressed for the first time. In his chapter ‘Palmyra and Emesa or “Palmyre sans Émèse”: Some Considerations on Palmyrene Trade Networks and the Mediterranean’ (Chapter 5), Leonardo Gregoratti reminds us of the puzzling lacunae in written and archaeological evidence from Palmyra and beyond about the routes taken by the caravans carrying imports from the East after leaving Palmyra and until they reached the Mediterranean harbours and other Roman markets. As he rightly states, ‘there is no clue in Palmyrene inscriptions about the itinerary for the oriental goods after Palmyra, and there is no explicit mention of other political subjects involved in the last tract of the so-called Silk Road, the one crossing the Roman provincial territories’ (Chapter 6). Indeed, knowing just how central Palmyra was in the trade networks of the first three centuries AD, it is surprising that we do not have firm evidence that allows us to disentangle the networks in this region that connected Palmyra with the shores of the Mediterranean. Gregoratti’s contribution revisits earlier hypotheses and gives its own take on how we might imagine that such networks worked and which evidence we might be able to draw on from the wider region in order to get closer to an understanding of the Palmyrene situation. Staying with the trade networks and the Palmyrene economy, Katia Schörle addresses Palmyra’s involvement in Mediterranean markets, focusing on economic patterns and the networks behind them both spatially and socially speaking in her contribution ‘Organizing Networks to Supply Mediterranean Markets’. She uses the evidence for economic activities in a broader sense to push for theories about the Palmyrene entanglement in wider Mediterranean market structures of very different kinds. The Tax Tariff from Palmyra is undeniably one of the most globally famous written documents from the ancient world. John F. Healey in his contribution ‘Language, Law and Religion: The Palmyrene Tariff in Its Roman Context’ revisits the Tariff in order to study it for the broader contexts which can be teased out from the Greek and Palmyrene Aramaic phrasing in the extensive document, despite the fact that it does not concern the international caravan trade as such but reflects taxation of the caravan trade, as Healey argues. This unique document, inscribed on large limestone slabs, today in the Hermitage in St Petersburg, is an important reminder that such documents were made for local use, but beneath the surface this usage would also inherently reflect broader patterns in place outside the city. These are the patterns that Healey looks for and explains to us, reminding us that revisiting well-known evidence indeed pays off. Maura K. Heyn turns to the Palmyrene portraits. Produced in the local limestone, these numerous representations usually of deceased Palmyrenes and their family members remain the largest corpus of portraits in the Roman world stemming from one place outside of Rome. In her contribution ‘Channels of Communication and Connections of Style: Palmyrene Portraiture in Its Wider Context’ she takes us on a comprehensive tour of portraiture from across the Roman Empire and draws out similarities and differences in portraiture from other outlier regions in the empire. While acknowledging that no one-fits-all interpretations can be applied to studies of portraiture from the Roman world, Heyn details the ways in which societies either did or did not tap into a broader visual koine that drew on traditions that also had roots in pre-Roman times for some regions. Most importantly, she reminds us of the pitfalls inherent in studying portraiture from regions remote from Rome through an exclusively provincial approach. Eleonora Cussini turns to the Jewish community in and of Palmyra in her contribution ‘Identity and Mobility of Palmyrene Jews’. Through studying the available evidence of Jews in and from Palmyra, she unpacks as far as possible the networks of this group of inhabitants – who also seem to have had broad-ranging networks, although not very visible in the evidence – across regions in the Mediterranean area. She begins from the few, but secure, attestations of Palmyrene Jewish families and addresses issues of the identity of the Palmyrene Jews through these sources and investigates the mobility of this group as well as their ties with their city. While such evidence mostly comes from the prosopography available through inscriptions, and not from material cultural evidence, apart from a few examples, it underlines exactly how difficult presence and absence of certain groups – religious or ethnic or both – can be to ascertain in the evidence available to us. We all know that absence of evidence does not equal actual absence, but we often still have difficulties dealing with this reality. Cussini shows us potential ways of tackling such issues. In the contribution ‘Palmyrene Military Expatriation and Its Religious Transfer at Roman Dura-Europos, Dacia and Numidia’, Nathanael Andrade revisits evidence for Palmyrenes outside of Palmyra who had travelled with the Roman army in various capacities and did not return to Palmyra as far as we know after they ended their military careers. Through comparing evidence from different regions and sites, including that of Dura-Europos further east, Andrade shows in which ways we might begin to understand the integration of Palmyrene ex-army members in a different light also in parts of the empire west of Palmyra.

Together these nine contributions give new, refreshing and solid insights into the possibilities of studying the relations between Palmyra and the Mediterranean on the basis of already-available evidence. Even though this evidence does not always give a lot away at face value, it has a tremendous potential when contextualized within the wider framework of evidence from a variety of other comparable sites or comparable situations as well as evidence which does not seem comparable, but which pushes us to revisit the Palmyrene evidence in a new light. With this volume, it is the intention and hope that new discussions may arise about Palmyrene society’s role in the broader Mediterranean world.