For every stone building or monument, there is a hole somewhere—a void equivalent to its solid mass, a scar left on the landscape. Sometimes barely visible and often forgotten, these negative spaces are among the most common landscape features of the precolonial Maya Lowlands settlements. Limestone quarries, in particular, constitute a prominent landform and can be found in virtually all settlements that flourished in the karst environment of the Yucatan Peninsula during the Classic period (ca. 200‒950 c.e.). However, in their attempt to understand the history and nature of these settlements, archaeologists have focused more on the positive features and upstanding structures created with the stone removed from the surrounding environment than on the negative or “empty spaces” left behind. As a result, quarry sites have remained in the background as taken for granted, unremarkable components of the landscape—sometimes recorded on maps but rarely investigated.

In this Special Section, we move quarry sites to the foreground. The four papers included here present some of the latest research and interpretations on precolonial Maya stone quarrying and working practices. Although the contributors to this Special Section adopt different approaches and perspectives, all investigate the worlds of those who worked intimately with limestone, cut and carved it to produce various materials and commodities, and moved and lived within the cratered landscapes created by its extraction. Grounded in the material remains of these activities and associated archaeological evidence, our studies demonstrate that, more than mere dots on maps, quarries have the potential to tell us meaningful stories about the past. The quarry sites explored throughout these papers were important nodes within local economic, social, and political networks. They were once living places, not only where key material resources were acquired, but also where individuals with heterogeneous and multiple expertise, motivations, and socioeconomic backgrounds participated in joint projects and, as they interacted with each other and the material environment, framed and constructed their realities.

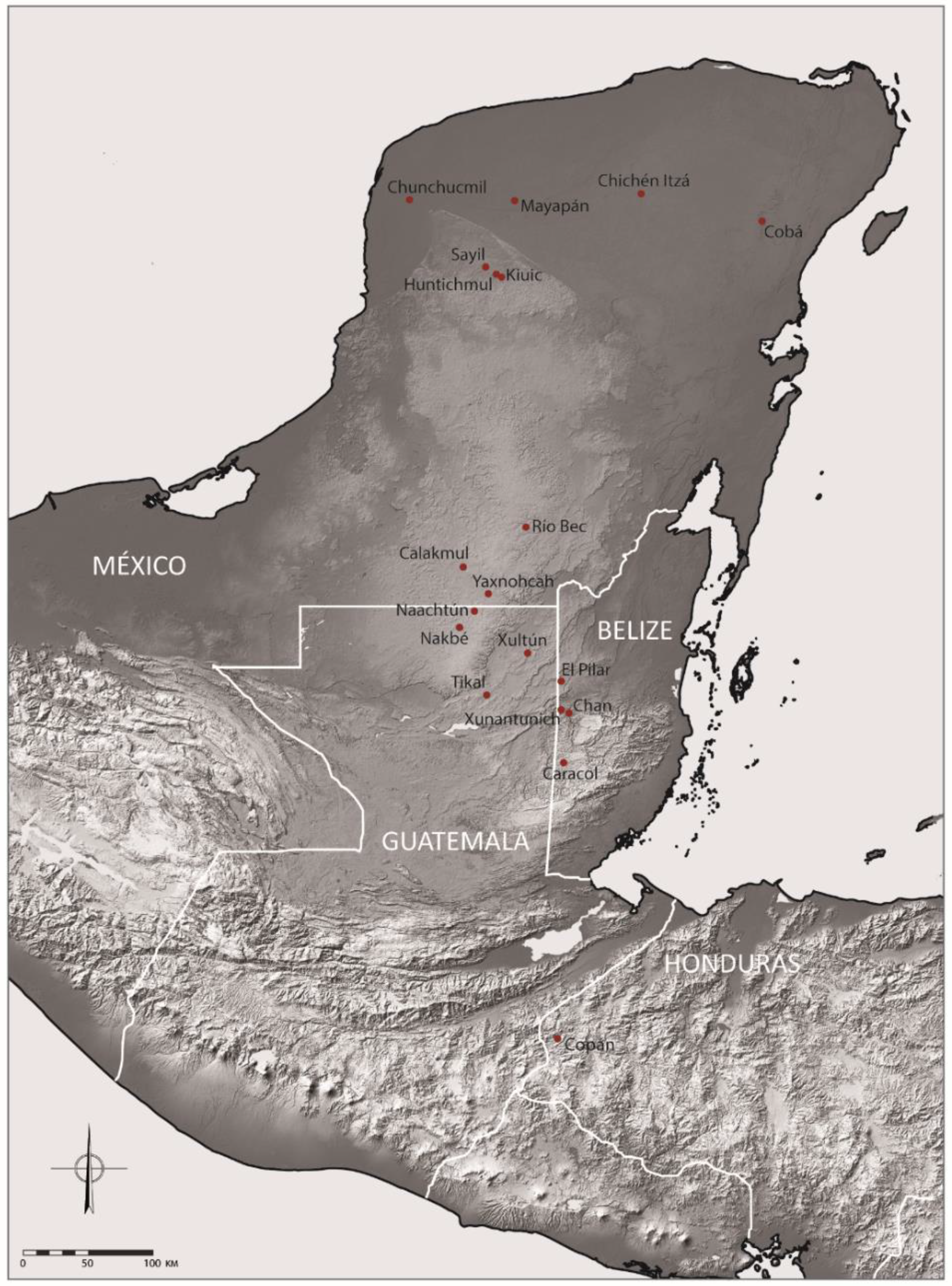

The quarries from which the contributors to this Special Section extract stories are limestone quarries. Although other stones played a significant role in precolonial Maya societies, limestone was the most common and widely used stone in the Maya Lowlands region, from the northern tip of the Yucatan Peninsula down to the base of the mountain ranges of Chiapas, Guatemala, and Belize (Figure 1). Local populations have been interacting with this ubiquitous and versatile material since at least 10,000 years ago, when they began to use natural caves as ritual spaces and explore their subterranean world (Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Meredith, Alsgaard, Dennehy and Kennett2017; Stinnesbeck et al. Reference Stinnesbeck, Stinnesbeck, Mata, Avilés Olguín, Sanvicente, Zell, Frey, Lindauer, Sandoval, Velázquez Morlet, Nuñez and González2018). The scant archaeological evidence from the earliest periods of occupation makes it difficult to determine exactly when limestone became a resource, and its exploitation began. However, recent research has revealed that, by the start of the Middle Preclassic period (ca. 1100/1000 b.c.e.), settled or semi-settled groups were already modifying and sculpting the natural bedrock into massive platforms (Brown and Bey Reference Brown and George2018; Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, Vázquez López, Fernandez-Diaz, Omori, Belén Méndez Bauer, García Hernández, Beach, Cagnato, Aoyama and Nasu2020).

Figure 1. Map of the Maya area showing the archaeological sites mentioned in the text (based upon NASA/JPL PIA03364, courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech).

Quarrying activities likely intensified over the following millennium, with the beginning of what may be called the “urban phenomenon” and the development of public/ceremonial complexes. Limestone came to play a more and more prominent role in a broad and diverse set of practices, from architecture and sculpture to tool manufacture and other domestic industries, such as vessel or figurine production. In the form of lime or lime-based products, it was also the glue that held buildings together, as well as a key ingredient for preparing a variety of other products, including food (e.g., nixtamalized corn), medicinal remedies, textiles, and bark paper. The calcareous bedrock underlying most of the Maya Lowlands provided a ready source of materials for these practices, including hard to soft limestone and unconsolidated, sandy materials. To extract these resources, people used two main strategies: opencast quarrying (i.e., extraction from the surface) and underground quarrying (i.e., subsurface tunneling or mining). Opencast quarries display a variety of shapes and sizes, from extensive leveled or terraced surfaces and shallow depressions to more intensively quarried areas, and cavities several meters deep (Figure 2a–b). Underground quarries are less frequent but not rare. They usually consist of subterranean chambers and horizontal galleries cut into soft, unconsolidated limestone deposits (Figure 2c–d).

Figure 2. Typical examples of (a) an opencast quarry and (b) its quarry face at Río Bec (images by Céline Gillot); and (c) a subterranean quarry and (d) its galleries near Kiuic (images by Kenneth Seligson).

Until recently, the individuals involved in creating these features, those who extracted, shaped, and processed limestone materials to turn them into useful forms, were largely invisible in archaeological interpretations of past Maya societies. This invisibility is beginning to change as archaeologists increasingly recognize the importance of looking beyond the built-up areas and incorporating quarry studies into their research agendas. In this paper, we provide an introduction to the history and development of archaeological approaches and narratives to ancient Maya quarries and quarry workers. This introductory paper also seeks to frame the Special Section and situate the case studies presented in the following articles. Through a discussion of the relevance of quarry data for understanding general and specific aspects of the precolonial Maya world, we emphasize the role that quarrying practices played in shaping not only the physical but also the social and ritual landscape in which people dwelled, acted, interacted, and defined themselves. We argue that by moving beyond top-down, elite-centric perspectives and paying closer attention to the socio-material dynamics at play in the quarries themselves, recent and future studies have the potential to shed more light on the complex realities of past stone production and producers. We conclude with a brief overview of current methodological trends and thoughts on how future investigations could enhance our knowledge of the ways in which quarries and quarrying practices fit into other aspects of past life.

History of research

In almost every corner of the Yucatan Peninsula, people have exposed and carved out the earth’s surface in search of lithic materials to enlist in the building of their houses and communities. Limestone has been extracted in large quantities and at many locations, preferably as close as possible to where it was needed. However, despite frequently leading to significant landscape alterations, quarrying activities have not always left identifiable traces in the archaeological record.

Given their relative shallowness and large extent, many Maya quarries can easily go undetected when covered by layers of sediments, fallen leaves, and vegetation. Alternatively, they may also have been buried under later constructions or converted into other uses, such as hydrological features (Akpinar Ferrand et al. Reference Akpinar Ferrand, Dunning, Lentz and Jones2012:98; Brewer and Carr Reference Brewer and Carr2022; Scarborough and Grazioso Sierra Reference Scarborough, Sierra, Lentz, Dunning and Scarborough2015:38; Weiss-Krejci and Sabbas Reference Weiss-Krejci and Sabbas2002:352) or agricultural terraces (Chase and Chase Reference Chase, Chase, Masson, Freidel and Demarest2020:145; Gillot Reference Gillot2018:131; Kestle Reference Kestle and Robin2012:216). Nevertheless, archaeologists have surveyed and mapped whole landscapes dotted with dozens of cavities where the well-indurated limestone caprock (laja) has been removed and the underlying, unconsolidated limestone deposits (sascab) dug out or tunneled into (Bullard Reference Bullard and William1960; Carr and Hazard Reference Carr and James E.1961; Horn and Ford Reference Horn and Ford2019; Hutson and Magnoni Reference Hutson, Magnoni and Hutson2017; Ringle et al. Reference Ringle, Gallareta Negrón, Ciau, Seligson, Fernandez-Diaz and Ortegón Zapata2021). Traditionally, these opencast quarries and underground mines have received only moderate attention, perhaps due to their unimpressive appearance or the shattered, nondiagnostic, and often undatable nature of the associated material remains. But recent decades have seen significant changes in approaches to investigating the ancient limestone industry amidst a growing recognition of the archaeological value of quarries.

In early scholarship, limestone procurement was often viewed as an economic activity primarily aimed at satisfying the needs of the elites, who were given credit for building the ancient cities. Because of its ubiquity and relative softness, the limestone of the Yucatan Peninsula was considered an inexpensive raw material, easy to obtain, cut, and shape—even with stone tools (Holmes Reference Holmes1895:23; Morley Reference Morley1946:359). Initially, the focus was on the amount of labor mobilized to extract, process, move, and assemble the countless stones used to build pyramids and other monumental constructions (Morris Reference Morris, Charlot and Morris1931:222–226). The first aim was to demonstrate that such works would not have been possible without a large workforce controlled through coercive means. Volumetric and energetic studies have since flourished and contributed to a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the stone building economy, showing that labor investment and recruitment varied according to place, time, and circumstances (Abrams Reference Abrams1994; Arnold and Ford Reference Arnold and Ford1980; Carmean Reference Carmean1991; Erasmus Reference Erasmus1965; Gonlin Reference Gonlin1993; Tourtellot et al. Reference Tourtellot, Sabloff, Carmean, Chase and Chase1992).

Advocates of these approaches have largely continued to regard limestone as a mere commodity, the use of which was intimately linked to the development of high-status architecture and, by extension, sociopolitical complexity (Abrams Reference Abrams1987; Abrams and Bolland Reference Abrams and Thomas1999; Carrelli Reference Carrelli, Bell, Canuto and Sharer2004; Fash and Sharer Reference Fash and Sharer1991; Hansen et al. Reference Hansen, Forsyth, Woods, Schreiner, Titmus, Brown and Bey III2018; Rosenswig and Masson Reference Rosenswig and Masson2002; Webster and Kirker Reference Webster and Kirker1995; Wingard Reference Wingard, Wingard and Hayes2013). Concomitantly, the individuals directly and physically involved in limestone extraction and production have been reduced to an anonymous and monolithic group of generalized, unskilled, and low-status laborers toiling under the direction of a handful of “specialists” (Abrams Reference Abrams1987:491, Reference Abrams1994:112). Although this oversimplified view still influences much of the writing about ancient Maya quarry and stone workers, it has been increasingly challenged by the advancement and expansion of quarry studies in Maya archaeology.

Thompson (ca. 1900; see Coggins Reference Coggins1992:11) appears to have been the first scholar to excavate quarry features in the Maya Lowlands. However, it was not until the late 1970s and early 1980s that researchers began to examine archaeological evidence for broader quarrying and stone-working practices. Early studies include those carried out at Coba (Folan Reference Folan1978, Reference Folan1982), Calakmul (Gallegos Gómora Reference Gómora and Miriam1985, Reference Gómora and Miriam1994), Tikal and Chinkultic (Ruiz Aguilar Reference Aguilar and Mária1985, Reference Aguilar, Mária, Laporte, Escobedo and de Brady1993), Nakbe (Titmus and Woods Reference Titmus, Woods, Laporte, Escobedo and Arroyo2002; Woods and Titmus Reference Woods, Titmus, Laporte and Escobedo1994), and Chichen Itza (Winemiller Reference Winemiller1997). Beekman (Reference Beekman1992) also explored a large quarry in the Pasión River region, but without finding conclusive evidence as to its date and, thus, antiquity.

These studies have generally centered on the technology of limestone quarrying and the overall quarrying process. Taken together, they demonstrate that, far from being a simple task, limestone quarrying entailed an intimate knowledge of and familiarity with the local geomorphology, the lithological characteristics of the bedrock, and the petrological variability of its strata (see also Arnold Reference Arnold2018:74–78; Brennan et al. Reference Brennan, King, Shaw, Walling and Valdez2013; Carmean et al. Reference Carmean, McAnany and Sabloff2011:147). Furthermore, as the ethnographic work of Ruiz Aguilar (Reference Aguilar and Mária1985) illustrates, making choices and decisions about which stone to extract and how, and about which tools to use and how much force to apply also required the ability to sensorily assess stone and its affordances or potentialities—just as contemporary skilled masons do when they collaborate with archaeologists to restore old buildings (Gillot Reference Gillot2018:153).

Research into limestone-quarrying technology has also revealed that, despite similar patterns in the techniques and tools used to extract blocks of stone and sascab (compare, e.g., Clarke Reference Clarke2020:165–181; Gallegos Gómora Reference Gómora and Miriam1994; Gillot Reference Gillot2018:133–140; Titmus and Woods Reference Titmus, Woods, Laporte, Escobedo and Arroyo2002:195), quarry sites varied in their form, scale, and distribution (Carr and Hazard Reference Carr and James E.1961:12; Horowitz et al. Reference Horowitz, Clarke and Seligson2021; Ringle et al. Reference Ringle, Gallareta Negrón, Bey III, Masson, Freidel and Demarest2020). While these variations have often been related to disparities in local topographies and geologies or in the nature of the stone quarried, it has become increasingly clear that material and practical considerations alone cannot fully explain them.

The last two decades have witnessed a significant step forward in understanding how and why the inhabitants of the Maya Lowlands engaged in quarrying and stone-working activities. By placing greater emphasis on the context in which these activities occurred, archaeologists have come to realize that the logic behind limestone extraction and processing was neither uniform nor simple but deeply embedded in broader social, political, and economic practices (Seligson et al. Reference Seligson, Negrón, Ciau and Bey III2017a). As Hutson and Davies (Reference Hutson, Davies, Overholtzer and Robin2015) point out, quarrying not only required specific know-how, but also access to suitable outcrops, appropriate tools, and skilled labor. Recent investigations show that once the ways people accessed these resources and made them available to others are understood, we can better discern and study the variability between the multiple, often overlapping strategies deployed to acquire limestone materials (Horowitz et al. Reference Horowitz, Clarke and Seligson2021). Importantly, they also challenge us to move beyond the oft-assumed dichotomy between state-run quarrying endeavors and kin- or neighborhood-based quarrying activities (Folan Reference Folan1982:150–152). Limestone resources played an important role in different social spheres and networks, and so did their extraction, processing, and distribution.

One of the most relevant contributions of these recent studies is a far more explicit recognition that limestone extraction and processing was not exclusively a state-sponsored or elite-managed industry. It was also an important component of Maya domestic economy. Evidence for this can be found in the wide distribution of extraction sites across residential areas, in the spatial association of these sites with specific residential compounds, and in the material remains recovered from residential contexts. At Chunchucmil (Dahlin et al. Reference Dahlin, Beach, Luzzadder-Beach, Hixson, Hutson, Magnoni, Mansell and Mazeau2005:235; Dahlin et al. Reference Dahlin, Bastamow, Beach, Hruby, Hutson, Mazeau, Hruby, Braswell and Mazariegos2011:81–83), Río Bec (Gillot Reference Gillot2018:121–123; Lemonnier and Vannière Reference Lemonnier and Vannière2013:406), Sayil (Carmean et al. Reference Carmean, McAnany and Sabloff2011), and Mayapan (Russell Reference Russell2008:537), for instance, researchers have found that most of the quarries located within residential areas were not only linked to, but also likely privately owned and managed by households in their immediate vicinity. In many cases, these quarries and the associated residential units are enclosed by stone walls or linear ridges (see also Folan Reference Folan1982:150). If some control over limestone resources existed in these settlements, it was likely in the hands of individual families or small household units (see also Kestle Reference Kestle and Robin2012:226). This does not mean, however, that every family or household engaged in quarrying activities to the same degree or had equal access to limestone sources and quarrying labor.

An uneven distribution of quarries (Dahlin et al. Reference Dahlin, Bastamow, Beach, Hruby, Hutson, Mazeau, Hruby, Braswell and Mazariegos2011:83), the presence of quarries whose production exceeded the labor capacity or the internal needs of the neighboring households (Gillot Reference Gillot2018:123), and the identification of specialized stone-working toolkits in domestic contexts (Andrews and Rovner Reference Andrews IV and Rovner1973; Eaton Reference Eaton, Hester and Shafer1991; Lewenstein Reference Lewenstein1995; Parker et al. Reference Parker, Bey III and Gallareta Negrón2019) suggest that some households extracted more limestone than they could consume. Within rural areas, and perhaps low-density urban zones, some of these households would have deliberately intensified their production and exchanged their labor to support kin-related or neighboring households and to meet social and/or reciprocal obligations. In some instances, these households could also have produced limestone materials for exchange beyond the domestic and neighborhood spheres. At Xultun (Clarke Reference Clarke2020; Horowitz et al. Reference Horowitz, Clarke and Seligson2021:9–12), Kiuic, and Huntichmul (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Bey III and Gallareta Negrón2019; Ringle et al. Reference Ringle, Gallareta Negrón, Bey III, Masson, Freidel and Demarest2020:103–105), archaeologists have indeed identified several household units or districts which specialized in limestone industry (see also Becker Reference Becker1973:402; Cobos and Winemiller Reference Cobos and Winemiller2001:288; Haviland Reference Haviland1974).

How limestone production contributed to households’ economic wealth and stability likely differed depending on whether their members worked as independent or attached stone workers, and whether they traded their products (or labor) within a marketplace economy or more institutional forms of exchange (like tribute obligations or patronage) (Clarke Reference Clarke2020). In addition, even where archaeological evidence points to a largely decentralized quarrying industry, like in the northwestern Puuc region, households’ abilities to benefit from limestone production activities may also have been partly influenced by the degree to which local elites or central authorities restricted access to and exerted control over high-quality stones (Carmean et al. Reference Carmean, McAnany and Sabloff2011) and skilled labor (Ringle et al. Reference Ringle, Gallareta Negrón, Bey III, Masson, Freidel and Demarest2020).

While much remains to be done to reconstruct the many stories that quarries can tell us about those who lived around, journeyed to, and exploited them, recent advances significantly challenge the picture of passive producers who simply responded to the expectations of a ruling class or centralized power. The numerous quarry sites scattered within and around monumental centers (Hiquet Reference Hiquet2019:1180) or along major features such as causeways (Cobos and Winemiller Reference Cobos and Winemiller2001:289) and defensive structures (Russell Reference Russell2008:538) attest to large-scale quarrying operations which undoubtedly monopolized large labor forces. However, in the light of recent findings, it seems very unlikely that the individuals who constituted this workforce were randomly selected from an anonymous mass of generalized and unskilled laborers.

Given the apparent importance of the limestone industry within the domestic economy, it is probable that the authorities or elites who sponsored and organized such monumental undertakings had access to a large pool of experienced and technically competent quarry and stone workers. The means through which these workers were mobilized and how they benefited from their participation in public building projects require further investigations. However, it is clear that their expertise and competencies did not just serve the upper social strata. For these individuals, “people with options, preferences, relationships, and motivations” (McCurdy Reference McCurdy, McCurdy and Abrams2019:231), quarries were likely more than simple holes in the ground. Instead, they were places where they actively engaged with their rocky landscape and with each other, gained and shared knowledge and skills, extracted and exchanged valuable economic resources, created and recreated social networks, materialized and negotiated power relationships, and in doing so, shaped their own realities and identities.

Connecting quarry studies with broader issues in Maya archaeology

Landscapes

The past decade has seen a growth in research and publications devoted to the “low-density, agrarian-based urbanism” or “high-density ruralism” of Classic Maya settlements (e.g., Fletcher Reference Fletcher2019; Hutson Reference Hutson2016; Isendahl and Smith Reference Isendahl and Michael E.2013). These discussions converge on the idea that most settlements were characterized by a mosaic of interrelated landscapes, with no clear divisions between the urban, the rural, and the natural, and with few strictly defined boundaries. Most of them can be broadly defined as territorial entities with areas dedicated to the exploitation of natural resources perfectly imbricated with residential areas (Fisher Reference Fisher2014; Lemonnier and Vannière Reference Lemonnier and Vannière2013). In other words, precolonial Maya settlements should not only be understood as those areas “built-up” with architectural features that have stood the test of time, but as more expansive and holistic sprawls, with residential units and relations keeping this whole together (Garrison et al. Reference Garrison, Houston and Firpi2019; Hutson and Welch Reference Hutson and Welch2021; Lucero et al. Reference Lucero, Roland and Robin2015).

Like agricultural terraces, house gardens, reservoirs, and causeways, quarries were key components of the landscape within which people acted and interacted. Extraction sites were integrated into and helped structure the shaped and sacred landscape, the residential fabric, and the space around individual house lots. They sometimes functioned as visual property boundaries and often served secondary functions such as reservoirs or gardens. The term “built environment” tends to conjure images of human-made “additions” to the environment such as edifices, roads, terraces, raised wetland fields, or built-up aguada (surface reservoir) berms. In most cases, the completion of these additions required the “subtraction” of stone, earth, and other features of the physical environment. Perhaps, therefore, a more appropriate framework for understanding the human-modified landscapes of the Classic Maya Lowlands would be the “shaped environment.”

As Seligson and Ringle discuss in the first article of this Special Section, quarry siting and excavation often required planning by multiple households, possibly in coordination with overarching political authorities. Households or entire neighborhoods sharing access to a common quarry required cooperation, constant communication, and agreements for long-term usage. In addition to the designated quarry areas, the landscapes of Maya settlement sprawls were pockmarked with small extraction locales that resulted from activities ranging from the leveling of terrain for plaza construction to the need for raw materials for expedient tool production, metates, hearths, slingstones, and crude foundation braces for small, perishable structures. Additionally, both small- and large-scale quarry excavation would have included the accumulation of non-stone raw materials like earth, wood fuel, kindling, and other vegetal resources.

Extracting portions of bedrock for construction purposes, for burnt lime production, or to level an area for a range of daily activities left clear scars on the landscape. As any visitor to an ancient Maya site can readily observe, especially when following paths that lead away from the most heavily visited areas, pits of various sizes and shapes riddle the wooded area immediately around the excavated and unexcavated mounds that are the remains of buildings. If we were somehow able to remove all vegetation and soil from the surfaces of ancient Maya settlement sprawls, we would undoubtedly find a crater-filled landscape with most of the land altered by extraction activities. This formerly hypothetical “moonscape” can now largely be revealed by the bare-earth digital terrain models (DTMs) generated from lidar airborne laser scanning data (Horn and Ford Reference Horn and Ford2019; Ringle et al. Reference Ringle, Gallareta Negrón, Ciau, Seligson, Fernandez-Diaz and Ortegón Zapata2021). It is important to recognize, however, that after stone was extracted from them, these quarries were not necessarily abandoned nor considered “emptied” of their utility. Recent research suggests that artificial depressions were often repurposed as reservoirs, agricultural or horticultural plots, and short- or long-term storage locales. These post-excavation uses must be kept in mind when viewing the now ubiquitous lidar DTMs, else they visually reinforce the notion of quarries as “emptied spaces.”

Water management studies have keyed in on the conversion of small household quarries into small household reservoirs through the application of a layer of water-resistant plaster or clay (Akpinar Ferrand et al. Reference Akpinar Ferrand, Dunning, Lentz and Jones2012; Brewer et al. Reference Brewer, Carr, Dunning, Walker, Hernández, Peuramaki-Brown and Reese-Taylor2017; Dunning et al. Reference Dunning, Beach and Luzzadder-Beach2012; Isendahl Reference Isendahl2011). However, not all quarries would have been converted into reservoirs: specific evidence such as the presence of watertight clay or plaster layers is necessary to deduce such functional shifts, as limestone itself is a porous material. Seligson and Ringle (this issue) discuss how the focus on the final forms of human-made subterranean chambers or chultuns often overlooks their initial role as sascab quarries. Opencast quarries could have also been filled with fertile soils to serve as artificial rejolladas, where agriculturalists and horticulturalists could cultivate a variety of valuable plants that required specific growing conditions (Dahlin et al. Reference Dahlin, Beach, Luzzadder-Beach, Hixson, Hutson, Magnoni, Mansell and Mazeau2005; Gillot Reference Gillot2018:142; Redfield and Villa Rojas Reference Redfield and Rojas1934:46). Other quarries appear to have been used to store lithic and ceramic waste products, likely until the material was needed as fill for construction projects, as crushed-mortar aggregate or ceramic temper, or perhaps as lithic mulch (Dahlin et al. Reference Dahlin, Bastamow, Beach, Hruby, Hutson, Mazeau, Hruby, Braswell and Mazariegos2011:84; Gillot Reference Gillot2018:143). Thus, quarries were not only integral to the foundation upon which the precolonial Maya world was built, but they remained integrated within many aspects of daily life and helped structure conceptions of home, place, and even cosmos.

The removal of bedrock would also have altered how physical environments were perceived (Horn and Ford Reference Horn and Ford2019). By choosing where to open their quarries, builders and quarry workers created artificial cosmograms, especially where the cavities formed through extraction were subsequently filled with water. When opened close to mountain-shaped constructions like platform mounds or pyramids, they played a role in the symbolic recreation of the sacred “water mountain” (Arnauld Reference Arnauld2016), thus serving as practical sources of raw materials during their initial excavation and as enduring features of the shaped environment afterward. Depressions located adjacent to civic complexes or masonry residences also made those constructions seem even taller and grander (Peuramaki-Brown and Morton Reference Peuramaki-Brown and Morton2019). In their discussion of the functions of artificial subterranean chambers, Brady and Layco (Reference Brady and Layco2018:52) argue that, in Maya thinking, “holes in Earth, even for mundane purposes such as extracting building material, will come to have supernatural connotations” and could have likewise been used for ceremonies that required an underworld setting. At the household level, quarries and mines were also socially and, perhaps, ritually important as permanent features connecting generations of family members to the landscape of “home.” While serving practical functions as property boundaries, they became palimpsests exhibiting the extraction activities where generations of ancestors had intentionally left their marks on the earth.

Relations

In the field of Maya archaeology, relational approaches have been productively used to underscore how various practices, identities, and memories emerged from and, in turn, created the conditions for a wide spectrum of relationships between people and disparate entities (Ardren and Miller Reference Ardren and Miller2020; Brown and Emery Reference Brown and Emery2008; Grauer Reference Grauer2020; Halperin Reference Halperin, Baltus and Baires2018; Harrison-Buck Reference Harrison-Buck2012; Lucero Reference Lucero2018; Woodfill Reference Woodfill2021). However, with a few notable exceptions (Hutson and Davies Reference Hutson, Davies, Overholtzer and Robin2015; Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Hendon and Lopiparo2014; Larmon Reference Larmon2020), less attention has been given to the many ways in which the substances and materials that constitute these elements participated in the configuration and reconfiguration of the material and social world. As several papers in this Special Section illustrate, quarry sites offer us a unique window from which to observe how limestone, as an “active partner in the shaping of worlds” (Cohen Reference Cohen2015:14), intervened in human affairs.

A quarried landscape is also a complex set of experiences and socio-material relationships mapped onto the land. Quarries, in this kind of relational cartography, operated as “nodes of convergence” (Smith Reference Smith and Smith2019), connecting people to the space they inhabited, to the things they lived with, and to each other. They were places where people’s paths and stones’ itineraries converged, overlapped, and intermeshed to create and nurture a diverse range of personal and collective experiences. Archaeological investigations at quarry sites, as the contribution by Clarke, Horowitz, and Paling reveals, may thus offer productive avenues for tracing individuals whose identities, statuses, and worldviews were intimately tied to, and were constituted through repeated engagement with stones. Alternatively, as shown by Gillot, Seligson, Ortiz Ruiz, Glumac, and Peraza Lope, quarries may also serve as a starting point from which to “follow” specific stones and look at what they “did” together with human actors and other things. In both cases, what comes to the fore is the connective role that a seemingly mundane material like limestone came to play in Maya societies.

Inherent to limestone’s materiality is its propensity to bring people together, foster collaboration, and forge, reinforce, and possibly even reorganize social relations—or what Hutson and Davies (Reference Hutson, Davies, Overholtzer and Robin2015:12) call the “sociality of stone.” Clarke and colleagues show, for instance, how the acts of quarrying and working limestone may have enmeshed individuals from potentially different socioeconomic classes into inter-household production relations. As they argue, variations in stone workers’ toolkits may point to segmented production sequences, with different households responsible for distinct but complementary tasks or sets of tasks. Gillot and colleagues’ exploration of the constellated web of practices that revolved around limestone also draws attention to its potential to act as a “boundary object” (Wenger Reference Wenger1998:105) or “connector” between individuals or groups of individuals making different kinds of things, giving them common ground upon which to share ideas, experiences, and practices.

Another important aspect is the knowledge and networks of knowledge that emerged from human–limestone interactions. Selecting the appropriate place to open a quarry, recognizing the properties of the stones, and becoming skilled enough to extract and subsequently shape and process them with the proper tools and techniques require not just some familiarity with the local topography and geology, but also specific know-how. As Gillot and colleagues underscore, traces of this practical knowledge can still be found in the chaîne opératoire of different practices. The technological choices made by quarry workers, lime producers, and tool makers may, in part, be linked to the specific affordances of limestone, but they also clearly indicate the existence of a shared repertoire of know-how, which in turn suggests socially interconnected learning and working environments. In other words, a common reliance on limestone alone cannot explain the development of similar know-how within these seemingly separate practices. While the agencies of material things might have facilitated knowledge circulation and transmission, social dynamics obviously played a critical role in shaping similar ways of doing and knowing within and across different limestone-working communities and broader networks.

Although minimal data exist on the social context in which Maya quarry and stone workers learned and shared their knowledge, recent practice theory provides various possible explanations for how knowledge may have circulated within and between stone-working communities of practice. These explanations include (1) the presence of “brokers” or individuals with the capacity to facilitate interconnections and knowledge flow (Wenger Reference Wenger1998:109); and (2) the concurrent practice of multiple crafts by the same (multicrafting) or different (multicraft production) groups in the same space or in a series of adjacent spaces (Hirth Reference Hirth2009:21; Shimada Reference Shimada2007:5). The first explanation is consistent with the model proposed by McCurdy and Hiquet (this issue) for the organization of large-scale quarrying and building projects, whereby managers would have overseen workgroups involved in different tasks and facilitated communication and coordination among them (see also McCurdy Reference McCurdy, McCurdy and Abrams2019). Multicrafting strategies and shared working spaces explanations better fit the archaeological evidence from domestic limestone and lime production settings, as documented by Clarke and colleagues and Seligson and Ringle (see also Seligson et al. Reference Seligson, Gallareta Negrón, Ciau and Bey2017b). The physical proximity in which the stone artisans worked and even lived would have indeed provided a fertile context for knowledge sharing through informal means, including face-to-face interactions, mutual observation and imitation, and collaboration between family members, kin, and neighbors.

Importantly, Clarke’s work (Reference Clarke2020) also reminds us that the quarry and stone workers’ skill set included more than practical knowledge. Based on ethnohistoric documents and epigraphic data from the Classic period, Clarke argues that success in quarrying, shaping, and assembling limestone blocks also demanded ritual protocols and performances. Although the archaeological record of the Maya Lowlands has not yet provided direct evidence for such symbolically charged quarrying, many accounts from various and unrelated cultural contexts refer to rituals and taboos associated with the acquisition and transformation of stone (e.g., Boivin and Owoc Reference Boivin and Owoc2004; Topping Reference Topping2021; Tripcevich and Vaughn Reference Tripcevich and Vaughn2013). In several of these accounts, stone quarrying is perceived as a dangerous pursuit requiring ritual intervention in the form of purification rites, offerings, consultations with the ancestors, and other rituals usually designated to ensure access to and appeasement of the forces or entities residing in the landscape. While these examples draw upon very different situations from, and are not directly transferrable to the precolonial Maya Lowlands (but see Hruby Reference Hruby, Hruby and Flad2007), they illustrate the cross-cultural nature of such practices and the embeddedness of stone technology in local perceptions and beliefs. Moreover, the ritual connotations of stone work likely extended beyond the physical acts of removing matter from the sacred earth and creating new openings to the underworld. Colonial-era and more recent documentations of lime production practices in the Maya area provide several examples of taboos and prescriptions associated with the manipulation, modification, and recombination of limestone (Russell and Dahlin Reference Russell and Dahlin2007; Schreiner Reference Schreiner2002; Seligson Reference Seligson2016; Seligson et al. Reference Seligson, Negrón, Ciau and Bey III2017a).

Interestingly, ethnographic evidence reveals that offerings made before, during, and after lime calcination do not necessarily require the intervention of a ritual specialist. They can be performed by an experienced lime producer or what Schreiner (Reference Schreiner2002:102) would call a “maestro.” This hints at the possibility that not all knowledge was meant to be publicly shared, and that the possession of esoteric knowledge could have provided some individuals a certain prestige and power, or the “opportunities to situate themselves as mitigating agents in critical transgressions against important, powerful, potentially terrifying supernatural entities” (Van Gijseghem et al. Reference Van Gijseghem, Vaughn, Whalen, Grados, Canales, Tripcevich and Vaughn2013:281; see also Kovacevich Reference Kovacevich, Mathews and Guderjan2017). Codified in prayers, songs, iconography, and myths, common sacred knowledge would also have facilitated the development of social bonds between stone workers, creating a sense of companionship, belonging, and collective identity, as discussed by McCurdy and Hiquet. Clarke’s analysis (Reference Clarke2020) of early colonial Yucatec Maya linguistic evidence also shows that, by the 16th century, the ability to engage ritually with stone, manipulate it, and alter its life course was still important enough to be expressed in the titles attributed to different categories of stone workers.

Identities

Like the word tun, “stone,” which gives a generic identity to the material worked by the artisans named in early colonial sources (Clark and Houston Reference Clark, Houston, Costin and Wright1998), the terms “quarry workers” and “stone producers” are no more than convenient labels to designate persons who devoted part of their time to quarrying and producing stone. There is no epigraphic evidence that such occupation-based titles existed before the Spanish invasion, although references to the acts of “pecking” and “carving” stone can be found in Classic period inscriptions (Grube et al. Reference Grube, Wagner, Prager, Botzet and Krempel2022; Houston Reference Houston and Costin2016). Furthermore, based on recent archaeological findings and a growing understanding of precolonial quarrying practices, we can confidently reject the idea that the individuals who quarried stone parceled themselves into a well-defined, bounded, and internally homogenous work-based class. Instead, the available evidence suggests that stone extraction and production activities were pursued by individuals whose occupations, skills, and identities were as diverse as the properties of the stones with which they worked.

Until quite recently, archaeologists, especially those working in the Maya area, did not show much interest in the identities of those responsible for extracting and shaping the countless stones with which the Maya made their world. Many scholars presumed that stone economies were organized in a strictly top-down manner, under elite oversight, rather than emerging from activities at the household level (Abrams Reference Abrams1994; Carmean et al. Reference Carmean, McAnany and Sabloff2011; Hansen et al. Reference Hansen, Forsyth, Woods, Schreiner, Titmus, Brown and Bey III2018; Ringle et al. Reference Ringle, Gallareta Negrón, Bey III, Masson, Freidel and Demarest2020). Although considerable efforts have been made to challenge the overly elite-centric approaches which have long dominated studies of precolonial Maya economy (Gonlin Reference Gonlin, Douglass and Gonlin2012; Hendon Reference Hendon, Meskell and Preucel2004; Kelly and Ardren Reference Kelly and Ardren2016; Lohse and Valdez Reference Lohse and Fred2004; Masson et al. Reference Masson, Freidel and Demarest2020; McAnany Reference McAnany2010), few scholars have attempted to move beyond the idea that access to stone resources and stone-working labor was the sole prerogative of elites, or to deconstruct stereotypical representations of quarry workers as alienated producers. Quarry workers are still largely excluded from discussions about stone economies or, at best, reduced to a group of undifferentiated and undifferentiable “laborers” recruited among a mass of (equally undifferentiated) “commoners.”

As this Special Section demonstrates, there is now sufficient evidence to provide a richer and more humanized account of the quarry workers’ stories and begin peopling these stories with more than faceless and passive subjects. Whether starting from the material remains recovered through archaeological investigations or energetic considerations, our studies show that—by bringing people back in our analyses, drawing attention to the meanings they ascribed to their own actions, and zooming on their individual lived experiences—we can provide a much more dynamic and complex picture of the many ways in which stone production activities unfolded, participated in the creation of social worlds, and played a critical role in the crafting of multifaceted identities.

Viewed from a top-down perspective, stone extraction is generally seen as an activity that required the ability to mobilize a significant labor force. When examined as a practice embedded in household economies, however, it appears as one of the many domestic activities that punctuated the rhythm of daily life, contributed to the economic and social positions of their practitioners, and helped to produce and reproduce horizontal and vertical relationships among themselves and with others. Moreover, while it may have occurred year-round, quarry work was probably performed on an intermittent basis, when the demand for stone resources increased (i.e., when climatic conditions were most favorable for most masonry works; see Gillot Reference Gillot2018:438; Parker et al. Reference Parker, Bey III and Gallareta Negrón2019:32) and when human resources were available (i.e., when agricultural tasks were limited; see Abrams Reference Abrams1987:490; McCurdy Reference McCurdy, McCurdy and Abrams2019:219; Wingard Reference Wingard, Wingard and Hayes2013:148). Such seasonal fluctuations in stone demand and labor availability may partly explain why even households for which stone production seems to have been a primary occupation engaged in other industries (Clarke Reference Clarke2020). One possibility is that such households diversified their activities as a risk-minimization strategy similar to that observed in other contexts (e.g., Alonso Olvera Reference Alonso Olvera2013; Horowitz Reference Horowitz2022; Inomata Reference Inomata and Shimada2007; Masson et al. Reference Masson, Freidel and Demarest2020; Robin et al. Reference Robin, Kosakowsky, Keller and Meierhoff2014; Widmer Reference Widmer and Hirth2009).

In many cases, the idea that quarry work may have been a full-time occupation simply does not fit the archaeological evidence. In numerous settlements, quarry sites are often spatially associated with rural or urban household compounds or “farmsteads” (Dunning Reference Dunning, Lohse and Valdez2004). Examples of such settlements can be found in different parts of the Maya Lowlands, including in the Belize River Valley (Horn and Ford Reference Horn and Ford2019), the Chenes/Río Bec region (Lemonnier and Vannière Reference Lemonnier and Vannière2013; Šprajc et al. Reference Šprajc, Marsetič, Štajdohar, Góngora, Ball, Olguín and Kokalj2022), or the Puuc area (Ringle et al. Reference Ringle, Gallareta Negrón, Ciau, Seligson, Fernandez-Diaz and Ortegón Zapata2021). In some of these settlements, quarry work would have been performed by individuals who were not only successful farmers, but also accomplished builders (Arnauld et al. Reference Arnauld, Michelet, Andrieu, Lacadena, Lemonnier, Nondédéo and Patrois2014; Gillot Reference Gillot2018; Michelet et al. Reference Michelet, Nondédéo, Patrois, Gillot and Gómez2013). Lithic evidence from Xultun and the Bolonchen District also attests to the presence of mason’s tools in the tool inventory of residences which seem to have prioritized stone production over other activities (Clarke Reference Clarke2020; Parker et al. Reference Parker, Bey III and Gallareta Negrón2019; Ringle et al. Reference Ringle, Gallareta Negrón, Bey III, Masson, Freidel and Demarest2020).

In addition to farming and building, quarry workers may also have engaged in a variety of contingent or complementary activities, including toolmaking (Clarke Reference Clarke2020; Dahlin et al. Reference Dahlin, Bastamow, Beach, Hruby, Hutson, Mazeau, Hruby, Braswell and Mazariegos2011) and, based on the large number of quarries converted into reservoirs, water management. Archaeologists have not yet found direct evidence for quarry workers who would have also been sculptors or carvers. However, lithic and use-wear analyses have shown that several tools typically included in stone workers’ toolkits were used not only for cutting and dressing stone blocks, but also for carving, drilling, and polishing a range of materials, including limestone, jade, bone, and shell (Aoyama Reference Aoyama2007; Lewenstein Reference Lewenstein1987; Stemp et al. Reference Stemp, Helmke and Awe2010; see also Clarke et al., this issue). Furthermore, textual and archaeological evidence confirms that the ability to chisel decorative elements was commonly credited to individuals proficient in more than one craft (Houston Reference Houston and Costin2016; Inomata Reference Inomata and Shimada2007; Montgomery Reference Montgomery1995). A lintel and a vessel signed with the same artist’s name (Grube Reference Grube and Kerr1990:328) suggest that such crafts may have been as distinct as stone sculpture and pottery manufacture.

By shifting the attention from the consumers to the producers, the contributors to this Special Section also reveal that limestone economies involved a much more heterogenous group of workers than previously assumed. Taken together, these studies open a window into the diversity that existed among precolonial Maya stone producers, not only in terms of their occupations, but also in their motivations, skills, and social relations. Households’ involvement in quarry work would have been motivated by concerns as diverse as acquiring materials for internal use, fulfilling obligations vis-a-vis kin and neighbors, producing commodities for exchange, and meeting elite demands. Clarke and colleagues’ (this issue) investigations in the Stone Production District of Xultun further illustrate how specialization in stone production could have contributed to the economic success of some households, while allowing them to shape locally meaningful relationships of interdependence and difference.

Likewise, multicrafting strategies may have simultaneously fostered cooperation and differentiation within and among neighboring households by reinforcing both their complementarity and their disparity in terms of knowledge, skills, and social capital (Hirth Reference Hirth2009; Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Hendon and Lopiparo2014; Shimada Reference Shimada2007). Interestingly, similar processes have been observed in the production of carved monuments (Houston Reference Houston and Costin2016; Montgomery Reference Montgomery1995; Van Stone Reference Stone and Mark2005). We do not know if experienced quarry workers bore the same “head, first” title that some Late Classic master sculptors did, but we can suppose that, like them, they used their expert skills and unique knowledge as a source of legitimacy and authority, within and beyond the quarries. Those with the highest and most diversified skills would also have been more likely to develop wider social networks and to play a key role in knowledge sharing and cross-craft interactions (Gillot et al., this issue; Gillot and Halperin Reference Gillot and Christina T.2019).

Just as thinking about quarry workers’ agencies has the potential to reveal the different motivations and consequences of their actions, exploring quarry workers’ identities has the potential to illuminate the diversity that existed among them and how this diversity was expressed in the quarries. The contributions to this Special Section suggest that stone production involved individuals from various economic and social statuses, whether they were rural or urban dwellers, and whether quarrying and shaping stone was their primary occupation or not. Energetic and osteological data from Naachtun also provide additional evidence that high-status people were not exempted from long, arduous physical tasks, including perhaps quarrying, shaping, and transporting stone (Hiquet Reference Hiquet2019; McCurdy and Hiquet, this issue). However, variations in the lithic assemblages found in the residential compounds of Xultun suggest that royal and elite involvement in stone production activities may have been limited to specific tasks (Clarke Reference Clarke2020).

Finally, an unexpected but welcome lesson quarry studies teach us is that we should not dismiss women and children from our reconstructions of past stone economies (McCurdy and Hiquet, this issue). Although quarry work may have been a male-gendered activity (Clark and Houston Reference Clark, Houston, Costin and Wright1998), and even a practice through which masculine identities may have been enacted and embodied (Leitch Reference Leitch1996), there are several reasons to think, first, that quarries were part of the daily landscape of men, women, and children alike; and second, that the knowledge and skills required to extract limestone were not exclusively held by men. These include the spatial association between quarry sites and residential structures, the apparent embeddedness of quarrying activities in domestic life, and the variety of practices that involved limestone resources and in which individuals of all genders and ages may have participated, including toolmaking, stone carving, and building (Aoyama Reference Aoyama2007; Ardren Reference Ardren2008; Gillot and Halperin Reference Gillot and Christina T.2019; Kelly and Ardren Reference Kelly and Ardren2016). Moreover, recent research on modern and contemporary quarrying activities demonstrates that women and children may have had the strength, ability, and their own motivations to engage in quarry work, not only as “helpers” in low-skilled tasks, but also as active participants in the extractive process (see, e.g., Lahiri-Dutt Reference Lahiri-Dutt2011; Talib Reference Talib2010).

Current trends and future directions

The four contributions presented here demonstrate the importance of limestone quarrying and working activities to precolonial Maya everyday life. By bringing them together, this Special Section aims to highlight the deep and enduring impacts of these activities on both the physical environment and the social fabric of its inhabitants. It also seeks to illustrate the variety of approaches that might be followed to identify the places, materials, tools, and people involved in these activities and interpret the wider context in which they were situated.

Seligson and Ringle combine lidar-based geospatial investigations with photogrammetry and horizontal excavations to examine the organization of limestone extraction and processing in the eastern Puuc region of the northern lowlands. By identifying different types of quarries, including shallow but extensive sheet quarries, using bare-earth DTMs, they demonstrate the viability of using lidar imagery to examine quarrying practices throughout the lowlands. Gillot and colleagues use geoarchaeological, archaeometric, and experimental data to explore the role of limestone as a key material in people’s engagement with their world. Moving through several case studies, from the extraction of building stones in the central lowlands to the production of lime and stone tools in the northwestern lowlands, they depict limestone industries not as separate autonomous spheres of activity but as enmeshed in a constellation of practices and broader networks of knowledge.

The following contribution, by Clarke and colleagues, draws on lithic use-wear and morphological analyses conducted at Xultun to reconstruct a comprehensive “quarrier toolkit” which will facilitate the identification of quarry and stone workers within the archaeological record. This will help develop narratives that give meaning to the quarry and stone workers’ lives and experiences and confer them some agency in determining their own fate, rather than reducing them to the broad outsiders’ category of “laborers.” McCurdy and Hiquet’s contribution points in the same direction, combining architectural energetics and storytelling approaches to explore how quarry and building sites at Early Classic Naachtun and Late Classic Xunantunich were not only places of stone extraction and use, but loci for social interactions among stone workers as well. By converting quantitative data into experiential narratives, they offer a concrete example of how archaeologists can achieve more effective public engagement and create stories that matter for both descendant and non-descendant communities. Importantly, their study also opens new avenues for considering the role of limestone in mediating relations of power in ways that go beyond top-down explanations and a rigid elite/commoner binary division, showing that quarrying and stone-working practices involved multiple groups of actors dispersed both spatially and socially within their community.

Quarry landscapes and practices result from complex material and social interactions. Significant gaps persist in our understanding due to the vast temporal span they encompass and regional disparities in archaeological knowledge. By weaving together diverse theoretical and methodological frameworks, future research will undoubtedly produce new data and bring some clarifications but will also likely generate new questions and new answers to older, enduring ones. Future remote sensing and photogrammetric surveys and analyses will continue to facilitate more detailed modeling and understanding of quarry landscapes, sites, and remains, revealing hundreds of additional quarry features, including subtle depressions invisible to the naked human eye or slight traces left on quarry fronts, blocks, and tools. Further archaeological excavations at quarry sites could provide a more precise chronological framework, allowing us to trace shifts in quarrying practices across time and space. Cross-regional comparisons also hold the potential to reveal more variations in the ways Maya people engaged with their geological environment and collaborated with it to shape their world and weave their narratives into history.

Spanish summary

Las canteras formaban parte integral del paisaje maya prehispánico. Si bien han sido consideradas tradicionalmente como sitios de producción, solo recientemente los arqueólogos han comenzado a considerarlas como lugares en los que personas con trayectorias, agencias e identidades propias dejaron su huella. Los cuatro artículos incluidos en esta Sección Especial presentan recientes estudios sobre el mundo de quienes trabajaban con la piedra caliza, habitaban los paisajes modelados por su explotación y construían sus realidades a través de las relaciones tejidas y mantenidas en las actividades de extracción, procesamiento y uso de esta roca. En este artículo introductorio, contextualizamos el tema a través de una revisión de las investigaciones previas y una descripción de los principales enfoques metodológicos y teóricos involucrados en la documentación, el análisis y la interpretación de las canteras mayas. Continuamos con una discusión sobre la relevancia de los estudios de canteras para la comprensión general de la sociedad maya precolonial, destacando cómo su explotación estuvo íntimamente relacionada con la configuración del paisaje físico y social, así como con la constitución de identidades colectivas e individuales. Como tantos otros aspectos de la vida maya precolonial, estuvo probablemente imbuida de consideraciones eminentemente prácticas, pero también rituales, sociales, económicas, y políticas. Concluimos con una breve descripción de las estrategias metodológicas actuales, una introducción a los temas abordados por los contribuidores de esta Sección Especial, y una mirada hacia el futuro y las formas en que tales estudios podrían llevarse adelante e integrarse en futuras líneas de investigación.