The study of households has long been part of anthropological archaeology. Archaeologists consider the household the smallest unit of economic and social production and acknowledge that household activities have bottom-up effects on society (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1977:89; Hodder and Cessford Reference Hodder and Cessford2004; Netting et al. Reference Netting, Wilk and Arnould1984; Wilk and Ashmore Reference Wilk and Ashmore1988). However, households do not have as high a profile as “lost” cities and royal tombs. Household archaeology is often associated with women, due in part to the equivalency drawn between women and the domestic sphere (see Gero Reference Gero1985; Hartsock Reference Hartsock, Harding and Hintikka1983). Archaeologies of gender and childhood have been confined mainly to household, rather than public, contexts. At the same time, engaging in feminist and gender-focused archaeology was how many women archaeologists began to be taken seriously in the realm of archaeological theory (Conkey Reference Conkey2007).

In a 2003 article, Margaret Conkey asked, “Has Feminism Changed Archaeology?” Her answer was yes. Feminist archaeologists had successfully shown that androcentrism and other biases affect interpretations of the archaeological record, leading archaeologists to question existing assumptions about the past (e.g., Claassen Reference Claassen1994; Conkey and Spector Reference Conkey, Spector and Schiffer1984; Gero and Conkey Reference Gero and Conkey1991). However, Conkey (Reference Conkey2003:875–877) pointed out that the important advances made in feminist and gender archaeology over the preceding decades could pass unnoticed by much of the field. Feminist-inspired and gender-focused archaeology were still marginalized, missing from major archaeology journals, and done mostly by women (see also Conkey Reference Conkey2007; Conkey and Gero Reference Conkey and Gero1997). Studies of gender and sexuality were often undertheorized and “unreflexively Western, normative, and heterosexual” (Conkey Reference Conkey2003:876). Explicitly feminist archaeology was rare and had not made much of an impact on broader feminist research.

In 2019, Marianne Moen returned to Conkey’s line of questioning in her article titled “Gender and Archaeology: Where Are We Now?” She found many of the same problems continued, including the marginalization of gender-focused archaeology and presentist biases in the interpretation of gender roles. Both Conkey and Moen advocate for a more intersectional approach to the archaeology of gender and for gender to be integrated into mainstream archaeological narratives.

Here, I address the apparent lack of progress made in the years between Conkey’s and Moen’s analyses, focusing on how considerations of gender have or have not permeated household archaeology. As early feminists argued, archaeologists should not ignore gender, because gender shapes human societies, identities, and daily life. Of course, not all gender-focused archaeology is feminist archaeology, aligned with the political goal of gender equality. Following Conkey, I am also interested in the presence or absence of explicitly feminist theory and practice in household archaeology.

My focus on household archaeology is informed by personal experience. When Samantha Fladd and Sarah Kurnick invited me to the Society for American Archaeology (SAA) symposium that led to this themed issue (see Kurnick and Fladd Reference Kurnick and Fladd2026), I thought about my positionality as a cisgender, able-bodied, White woman and the associated privileges. I also reflected on the decisions I made during graduate school and how those shaped my career as a US archaeologist working in Mesoamerica. Thinking about gender and representation, I wondered why I was drawn to household archaeology. Was it because I admired the women archaeologists making major contributions to the field by researching domestic contexts? Or did a subconscious bias make me associate my gender with the domestic (see Gero Reference Gero1985)? At the same time, I wondered why I did not incorporate feminist theory or a focus on gender into my dissertation. As I prepared to publish my research and enter the job market, did I want to appear more “objective” or avoid being pigeonholed as a woman interested in “women’s issues?” With these questions in mind, I decided to examine trends in participation and citation within household archaeology.

In this resulting article, I analyze both content and equity issues. In a 1997 essay, Alison Wylie divides early feminist archaeological works into two groups: “content critiques” and “equity critiques” (Wylie Reference Wylie1997). Content critiques concern the erasure of women and other marginalized actors from history, androcentrism, and the projection of gender norms and biases onto the past. Equity critiques are sociopolitical studies of our profession, including demography, employment patterns, and institutional structures. Wylie advocates for “integrative” critiques that combine content and equity studies to address how the sociopolitics of archaeology as a discipline affects the production of archaeological knowledge. As an example, she cites a study in which Joan Gero (Reference Gero, Cros and Smith1993) argues that the marginalization of women in Paleoindian archaeology led to interpretations of Paleoindian subsistence that were overly focused on the hunting of large mammals.

Here, I attribute the failure to fully integrate gender into mainstream archaeology to structural issues in the field. First, I analyze household archaeology content, reception, and author gender in several major archaeology journals. I contrast the results with those for a journal of historical archaeology, and the differences lead me to consider multiple factors that likely discourage archaeologists from pursuing gender-focused and feminist-inspired research. These include the underrepresentation of women in major journals, trends in archaeological epistemology, the academic job market, and political strategies. Based on this research, I make some suggestions for moving forward.

Analysis of Major Archaeology Journals

Following the examples of Mary Beaudry, Scott Hutson, and others (Bardolph Reference Bardolph2014; Bardolph and Vanderwarker Reference Bardolph and Vanderwarker2016; Beaudry and White Reference Beaudry, White and Claassen1994; Fulkerson Reference Fulkerson2017; Fulkerson and Tushingham Reference Fulkerson and Tushingham2019; Handly Reference Handly1995; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2020; Horowitz and Brouwer Burg Reference Horowitz and Burg2024; Hutson Reference Hutson2002, Reference Hutson2006; Rautman Reference Rautman2012; Tushingham et al. Reference Tushingham, Fulkerson and Hill2017; Victor and Beaudry Reference Victor, Beaudry and Claassen1992), I reviewed major archaeology journals to see how participation in and citation of household archaeology changed between 1990 and 2019. I focused on journals not only because they are easy to search online but also because peer-reviewed articles play a major role in academic hiring, promotions, and tenure. I used qualitative research software to identify articles within my sample that addressed gender, women, feminist theory, and childhood. My expectation was that participation in gender-focused household archaeology would increase only modestly over three decades. I also expected that gender-focused household archaeology would remain less prestigious, as measured by citation counts, than other areas of archaeology. I confined my study to household archaeology because I assumed, based on familiarity with the literature, that one would find more gender-related archaeology within the household topic than elsewhere.

I used Web of Science—an online platform for exploring academic databases, owned by Clarivate—to obtain my sample of household archaeology publications in eight major, nonregional archaeology journals that were in publication from 1990 through 2019: the SAA’s American Antiquity and Latin American Antiquity, Antiquity, Journal of Field Archaeology, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, Cambridge Archaeological Journal, Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, and Journal of Archaeological Science. These journals are popular among US academic archaeologists, but they are not all based in the United States, and they publish work by international scholars. After some experimentation, I searched for the term household* within the field of Topic, capturing the titles, abstracts, and keywords of journal articles. The search yielded 267 journal articles (MacLellan Reference MacLellan2025). Web of Science provided a citation count for each.

I classified the gender of the first authors based on typically gendered first names, pronouns used in online bios or interviews, or personal knowledge. I expected to have a few nonbinary authors and authors of unknown gender in the sample, but in the end, all were categorized as either men or women. This does not reflect the complex, dynamic identities of these scholars (see Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2025), but rather how readers, editors, and citers would most likely interpret their genders.

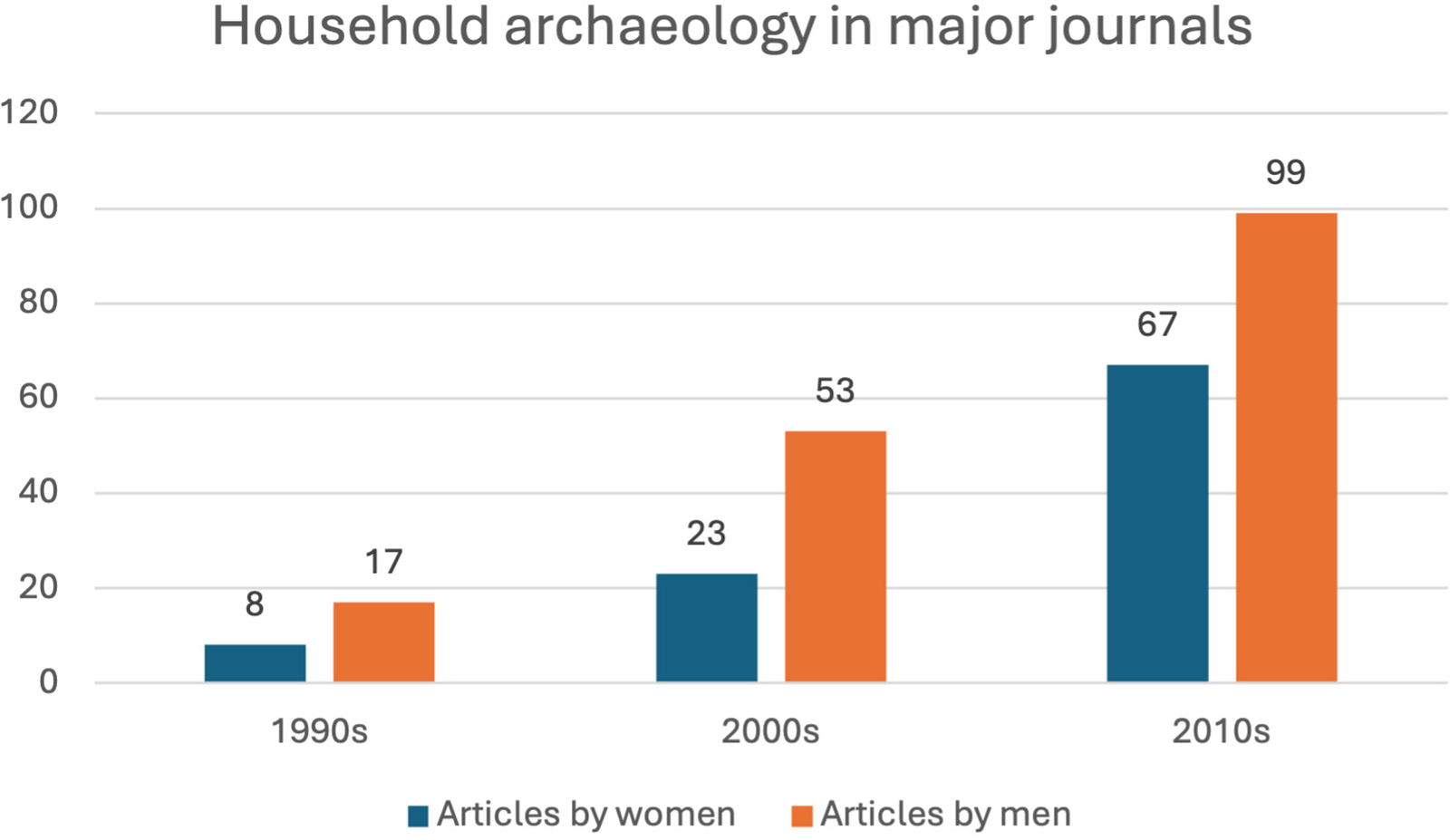

Figure 1 shows that the number of household archaeology articles increased dramatically each decade. This trend may be partly explained by increasing numbers of academic archaeologists, plus the pressure to publish or perish, rather than solely by a growing interest in households.

Figure 1. Number of household archaeology articles by women versus men first authors in eight major journals, by decade.

During the first two decades, about one-third of the articles had women as first authors, while this rose to 40% in the 2010s. This increase in women’s authorship in the 2010s could partly be explained by increasing numbers of women in archaeology. However, researchers have found that although women now make up about half of archaeologists in the United States, their publication rate lags substantially. For example, Dana Bardolph (Reference Bardolph2014) found that for 1990 through 2013, only 24% of articles in American Antiquity and 29% of articles in a sample of national/international and regional journals had women lead authors. More recently, Shannon Tushingham and colleagues (Reference Tushingham, Fulkerson and Hill2017) and Laura Heath-Stout (Reference Heath-Stout2020) found that prestigious, peer-reviewed archaeology journals continue to be dominated by men authors. For example, Heath-Stout reports that for 2007 through 2016, 68% of American Antiquity authors identified as men. Therefore, women’s 40% representation for 2010 through 2019 may actually indicate an increased interest in household archaeology by women versus men.

In all three decades, men published more household archaeology. However, they were not more likely to be cited. Table 1 shows that median citation counts were slightly higher for women’s articles. A Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test indicates that the citation counts for the articles by women do not differ significantly (![]() $\alpha $ = 0.05) from those for the articles by men (W = 8431.5, p = 0.81). Similarly, in an analysis of gendered citation practices in US archaeological journals, Hutson (Reference Hutson2002:336–339) found that household archaeology is one of few topics for which women are relatively highly cited, within a discipline in which women are undercited relative to their publication output. This may draw some women, like me, to household archaeology.

$\alpha $ = 0.05) from those for the articles by men (W = 8431.5, p = 0.81). Similarly, in an analysis of gendered citation practices in US archaeological journals, Hutson (Reference Hutson2002:336–339) found that household archaeology is one of few topics for which women are relatively highly cited, within a discipline in which women are undercited relative to their publication output. This may draw some women, like me, to household archaeology.

Table 1. Median Citation Counts for Household Archaeology Articles in Eight Major Journals.

Using the qualitative analysis software MAXQDA, I searched within the sample of household archaeology publications for articles dealing with feminism, gender, women, and childhood. I used the lexical search and auto-coding functions to identify articles that include the search terms gender*, wom*n* and mujer*, children* and childhood*, and feminis*. I included mujer because I thought it might be useful in searching Spanish-language quotations and articles, but its inclusion did not meaningfully affect the results. I chose not to include “men” to avoid the androcentric use of that word in place of “people” and because any study focused on masculinity should be caught by “gender.” I did not include “sex,” because I wanted to avoid tables of burials and because any study of sexuality would be caught by the included terms. I removed the articles that referenced the search terms only in their bibliographies or acknowledgments, resulting in a total of 132 manuscripts out of the original 267 (MacLellan Reference MacLellan2025).

Figure 2 shows the percentages of articles that include each of the gender-related search terms, separated by decade. The pattern suggests that interest in gender increased within household archaeology around the year 2000 and has held steady ever since. Meanwhile, explicit discussion of feminist theory has never become common in household archaeology articles within major archaeology journals.

Figure 2. Percentages of household archaeology articles that include each gender-related term, in the eight major journals, by decade.

A closer look at the underlying data (Table 1) reveals that women authors addressed gender at higher rates. For the 2000s, 70% of women’s articles included the terms compared to 45% of men’s. For the 2010s, 61% of women’s articles included the terms versus 42% of men’s. A chi-squared test of the combined data from all three decades indicates that this difference is statistically significant (![]() ${{\chi }^2}$ = 8.60, df = 1, p = 0.0036).

${{\chi }^2}$ = 8.60, df = 1, p = 0.0036).

Are authors who addressed gender punished by having a lower citation count? This could explain why gender and feminist perspectives have not been integrated more enthusiastically into archaeological research. I broke down the data by decade and did not find strong evidence of citation prejudice (Table 1). For each decade, the citation counts of the articles that include gender terms do not significantly differ from those of other articles (1990s: W = 89.0, p = 0.35; 2000s: W = 577.5, p = 0.14; 2010s: W = 3495.5, p = 0.87). Gender-focused household archaeology does not seem to be less prestigious.

Next, I asked if either men or women might be particularly dissuaded from focusing on gender due to citation biases. I grouped the publications into four categories based on the gender of the first author and whether the article included the gender terms (Table 1). For the gender-focused articles, I found that the median citation counts were similar for women and men authors in all three decades. In addition, the four articles that mentioned feminist theory were relatively well cited. The category of articles-by-women-that-do-not-include-gender was the most skewed by high-citation outliers, especially during the first two decades. A Kruskal-Wallis test comparing the four categories for each decade showed no significant differences (1990s: ![]() ${{\chi }^2}$ = 2.33, df = 3, p = 0.51; 2000s:

${{\chi }^2}$ = 2.33, df = 3, p = 0.51; 2000s: ![]() ${{\chi }^2}$ = 2.37, df = 3, p = 0.50; 2010s:

${{\chi }^2}$ = 2.37, df = 3, p = 0.50; 2010s: ![]() ${{\chi }^2}$ = 1.26, df = 3, p = 0.74). Contrary to my original hypothesis, I did not find that focusing on gender incurred a citation punishment for women or men authors. Nevertheless, gender has still not permeated the majority of archaeological analyses.

${{\chi }^2}$ = 1.26, df = 3, p = 0.74). Contrary to my original hypothesis, I did not find that focusing on gender incurred a citation punishment for women or men authors. Nevertheless, gender has still not permeated the majority of archaeological analyses.

Analysis of Historical Archaeology

My analyses of these eight major archaeology journals support Moen’s (Reference Moen2019) argument that gender-focused archaeology remains marginalized. However, there is one subfield in which gender is more integrated into mainstream research: historical archaeology (see Wilkie and Hayes Reference Wilkie and Hayes2006). Historical archaeologists often use material culture to fill in gaps or to contest information in written documents, giving “voice” to marginalized groups (see Little Reference Little2007). This work may lend itself to feminist practices. For example, Maria Franklin (Reference Franklin2001) and Whitney Battle-Baptiste (Reference Battle-Baptiste2011) advocate for Black feminist theory in historical archaeology of the African American diaspora.

Historical archaeology’s embrace of gender research—and of women researchers—is not new. In 1991, Historical Archaeology, the journal of the Society for Historical Archaeology, published a special issue on gender in historical archaeology (Vol. 25, No. 4). In the early 1990s, Katherine Victor and Beaudry (Reference Victor, Beaudry and Claassen1992) compared American Antiquity and Historical Archaeology and found women were slightly better represented in the latter. Beaudry and Jacquelyn White (Reference Beaudry, White and Claassen1994) found that historical archaeology provided a “less chilly” climate for women than other subfields. More recently, Bardolph (Reference Bardolph2014:531) found that Historical Archaeology is one of the archaeology journals closest to achieving gender parity, with women leading 35% of the articles published between 1990 and 2013. Of course, 35% is far from actual equity.

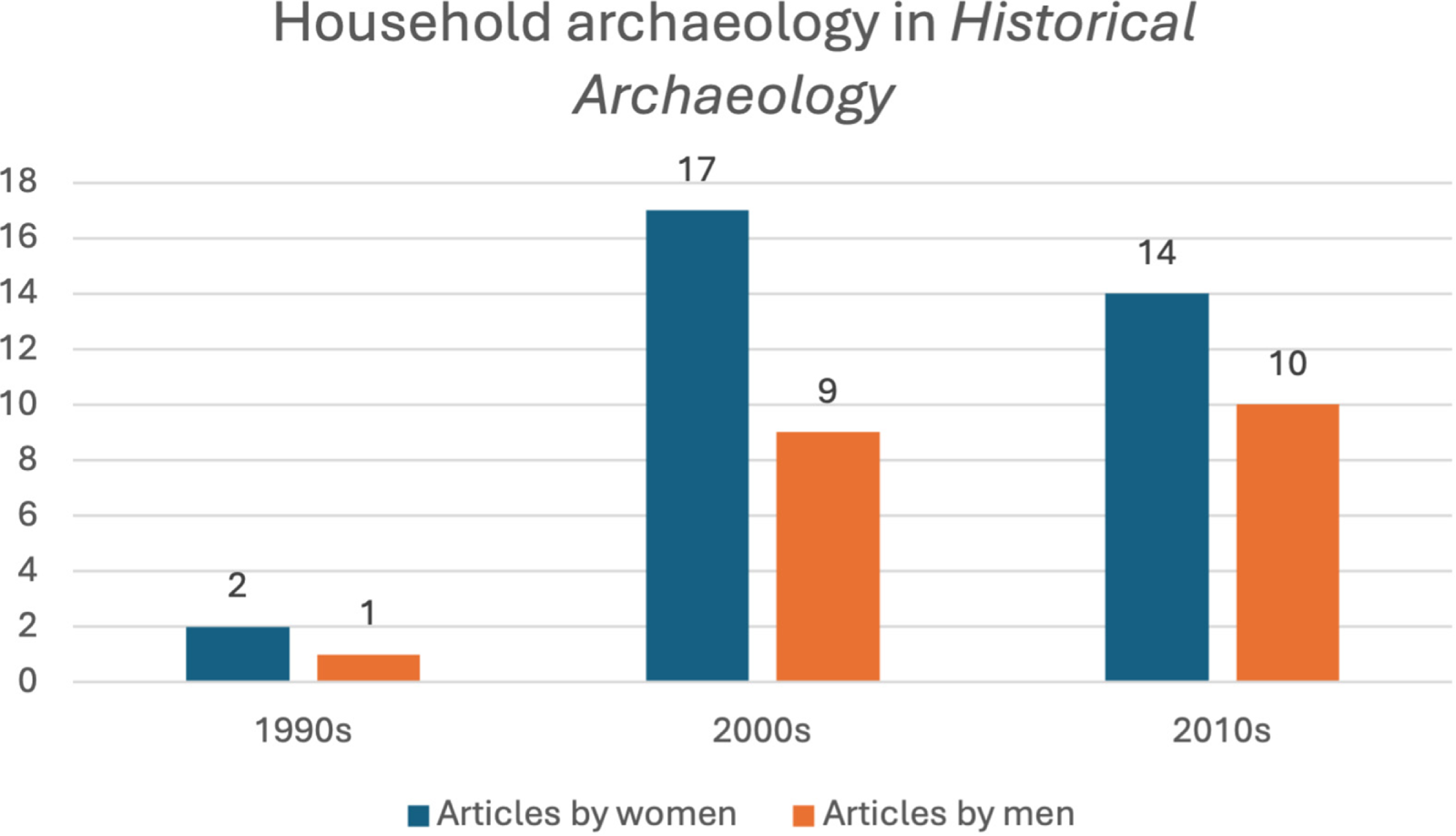

I ran the same analyses on Historical Archaeology as I did for the eight major journals. The sample for 1990 through 2019 comprised 53 household-related articles (MacLellan Reference MacLellan2025). The results indicate that gender has long been more integrated into historical archaeology, although explicitly feminist research has never been common (Figure 3). The contrast with the eight major journals is even more impressive because those journals also publish research in historical archaeology, meaning a significant portion of the gender-related articles in my first sample may also be written by historical archaeologists. It is also notable that women published more household research in Historical Archaeology than did men for all three decades (Figure 4), whereas the opposite was true for the eight major journals. This higher participation by women is correlated with more mentions of gender by both women authors and men authors.

Figure 3. Percentages of household archaeology articles in Historical Archaeology that include each gender-related term, by decade. Compare to Figure 2.

Figure 4. Number of household archaeology articles by women versus men first authors, by decade, in Historical Archaeology. Compare to Figure 1.

Inferences and Uncertainties

The relatively high prevalence of gender mentions in the Historical Archaeology sample could be partly explained by the political goals of the subfield of historical archaeology, which frequently seeks to understand colonialism and represent marginalized peoples. However, many of the mentions of “women” and “children” in the sample are quoted from historical documents describing population demographics without further engagement. The prevalence, then, is partly due to the use of primary source documents, rather than political motivation.

The availability of texts could make historical archaeologists more likely to explore gender than other archaeologists, due to a long-standing and widespread attitude that ideologically coded topics like gender and religion are more difficult to interpret based on the material record than are more tangible, quantifiable topics like subsistence, technology, and biological sex. This idea is exemplified by Christopher Hawkes’s (Reference Hawkes1954) “ladder of inference.” Hawkes argues that archaeologists generally must combine historical/ethnological evidence with material data to make any interesting interpretations about past cultures, even in “prehistoric” contexts. In the absence of written texts, it is easiest to come to conclusions about technology (bottom step of the ladder) and subsistence (second step), more difficult to understand social and political dynamics (third step), and most difficult to understand religion and spirituality (top step). Gender relations fall within Hawke’s third step. He gives as an example: “if the more richly furnished graves are women’s, does that mean female social predominance, or male predominance using the adornment of its subjected womenfolk for its own advertisement?” (Hawkes Reference Hawkes1954:162). Contrary to some interpretations, Hawkes does not advise archaeologists to give up studying the political and the spiritual, which he calls the “more human” aspects of society, but rather argues that historical and ethnographic evidence (humanities) are necessary to do interesting archaeology (Evans Reference Evans1998).

Hawkes’s ladder of inference has a common-sense appeal. My students tend to agree with Hawkes that it is impossible to see “religion” in the absence of written records. However, our field has experienced many theoretical and methodological shifts since Hawkes published his model, including the propagation of processual, postprocessual, cognitive, feminist, Indigenous, and queer archaeologies (see Fogelin Reference Fogelin2019; Thomas Reference Thomas2001; Trigger Reference Trigger2006). The positivist processual wave may have emphasized the pessimistic parts of Hawkes’s argument while overlooking his call to integrate history and science, and the ladder of inference became a target of criticism by later waves. Some archaeologists have directly challenged Hawkes’s contention that the “more human” aspects of society are harder to see archaeologically. For example, Lars Fogelin (Reference Fogelin, Whitley and Hays-Gilpn2008) argues that the archaeology of religion should be no more difficult than the archaeology of subsistence, since both include human actions and leave material traces. Nevertheless, the idea that written records are necessary to understand power dynamics in the past may contribute to the failure to integrate gender into mainstream archaeology.

Today, mainstream archaeology is again in a positivist swing of the theory pendulum, and we tend to err on the side of scientism and quantification at the expense of our discipline’s more humanistic and reflexive sides. For example, some archaeologists assume that relative sizes of ancient dwellings represent inequality, cross-culturally and throughout history, to use the convenient Gini coefficient (Peterson and Drennan Reference Peterson, Drennan, Smith and Kohler2018; Wengrow Reference Wengrow2024). Others see counts of radiocarbon dates as a proxy for ancient population sizes, rather than as a reflection of how archaeologists spend grant money (Attenbrow and Hiscock Reference Attenbrow and Hiscock2015; Hiscock and Attenbrow Reference Hiscock and Attenbrow2016). Ancient DNA evidence is often given precedence over more nuanced anthropological data to serve as the basis for sweeping claims (Callaway Reference Callaway2018; Lewis-Kraus Reference Lewis-Kraus2019; Sawchuk and Prendergast Reference Sawchuk and Prendergast2019). I do not dismiss highly quantitative and big data studies, but I notice a tendency to view them as more rigorous, conclusive, and objective than they probably are, considering the fragmented and sometimes biased nature of the archaeological record.

Donna Haraway (Reference Haraway1988) argues that feminist knowledges are always situated and partial, whereas “masculinist” knowledge is totalizing and employs a view from nowhere (see also Hartsock Reference Hartsock, Harding and Hintikka1983; Wylie Reference Wylie1997). Highly quantitative projects fall on the totalizing side of that continuum. Meanwhile, feminist, decolonial, and queer theorists encourage us to critically reflect on knowledge and appreciate the inherent uncertainty of the archaeological record (Rizvi Reference Rizvi2019; Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Marila and Beck2024). Returning to Hawkes’s gender example, it would be unusually informative if all adult skeletons sexed as female in a cemetery had received distinct mortuary offerings. Hawkes would have evidence that this society enacted a strict gender binary, which cannot be taken for granted.

This imagined cemetery reminded me of the Lady of Cao, a Moche individual buried in the masculine regalia of an elite priest and sexed as biologically female. Mary Weismantel (Reference Weismantel, Stryker and Aizura2013) and Gabby Omoni Hartemann (Reference Omoni Hartemann2021) point to the Lady of Cao when advocating for a transgender archaeology. Their point is not that we should interpret the Lady of Cao as transgender, but rather that we should be open to alternative interpretations. Hawkes may have despaired at never knowing why female-identified people were buried with elite objects, but it is more productive to reflect on various possibilities and how our own assumptions draw us to some explanations over others.

All interpretations of the past involve speculation and biases, whether we are studying stone tool production or the socialization of children (Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Marila and Beck2024). Whether positivist or postmodern, we all create narratives, inferring the best explanations (Fogelin Reference Fogelin2007), constrained by the material record (Wylie Reference Wylie1992), influenced by our own positionalities (Fryer Reference Fryer2020; Meskell Reference Meskell2002; Wylie Reference Wylie, Figueroa and Harding2003), and never reaching a complete or objective image of the past. Queer theorists encourage us to look beyond norms and imagine the diversity that must have existed in past societies. For example, Thomas Dowson (Reference Dowson, Geller and Stockett2006) points out that a homosexual interpretation of past behavior is heavily scrutinized—even when supported by evidence, and even by feminist archaeologists—whereas a heterosexual interpretation is accepted as a given (see also Geller Reference Geller2009a, Reference Geller2009b; Voss Reference Voss2000). It would be beneficial to archaeology to include more studies that acknowledge bias, uncertainty, and speculation in our major journals. For this to happen, the field must support scholars, including students and junior colleagues, who push us to question our assumptions, particularly in relation to gender.

Job Market Strategies

One way to more fully integrate the study of gender into archaeology would be to hire more specialists in gender, childhood, sexuality, feminist theory, and queer theory into tenure-track positions at universities. Those positions provide job security, the opportunity and motivation to apply for major grants, and a platform to teach and advise future generations of archaeologists. Pamela Geller (Reference Geller, Amoretti and Vassallo2016:9) reports that for 2012–2013 and 2013–2014, only two tenure-track archaeology job advertisements for each academic year mentioned gender. I was surprised the number was even that high, so I went to the “Academic Jobs Wiki” (https://academicjobs.fandom.com/wiki/Archaeology_2024-2025) to learn more. Based on my count, over the last 15 academic years (2010–2024), the number of assistant professor (or open rank) job ads in archaeology at US universities that mentioned research on gender or collaboration with women’s/gender/sexuality studies departments fluctuated between zero and three, with a mean of 1.27 ads (or 4%) per year (Table 2). Of the 19 total ads, six (about one-third) were aimed at historical archaeologists. Importantly, gender was listed as only one possible focus in these ads, and it would be difficult to investigate how many resulted in hiring professors who study and teach archaeologies of gender.

Table 2. Assistant Professor Job Ads That Mention Gender, Archaeology Academic Jobs Wiki.

For the 2024–2025 academic year, I found only one tenure-track job ad (out of 30) mentioning gender, and it was for a bioarchaeologist. I searched the Academic Jobs Wiki pages for “Anthropology” and “Cultural Anthropology” for the same year and found four tenure-track cultural anthropology assistant professor job ads (including one in medical and one in linguistic anthropology). Gender is much more prominent on the 2024–2025 Academic Jobs Wiki pages for “History,” which are divided by geographic region. There, I found 23 ads meeting the criteria, spread across all regions. History is a larger field than anthropological archaeology, but regardless of the relative proportions, the recruitment of many more permanent, tenure-eligible professors who research and teach on gender must contribute to a different intergenerational culture. This may influence historical archaeology, since the two disciplines overlap in methods and interests.

The academic job market is extremely competitive, and it does not seem like a promising strategy to sell oneself as an archaeologist of gender, with an exception for historical archaeologists. This may help explain why more archaeologists are not publishing gender-focused research. Unfortunately, the current political climate in the United States does not seem conducive to hiring more feminist archaeology professors. It does not seem conducive to hiring more anthropologists or more tenure-track professors in general, but recent executive orders on “gender ideology,” diversity initiatives, and federal grant funding especially endanger gender as a research topic. To foster progress in this important area of study, academic departments with the opportunity to hire should strongly consider how their university and their field could benefit from colleagues who counts gender among their interests.

Safe Spaces and Playing It Safe

I suspect the proximate reason why more gender-focused archaeology is not published in mainstream journals is not that it is rejected, but rather that it is not submitted. Women in archaeology submit fewer journal articles and fewer grant applications, even though their submissions are on average as successful as men’s (Beaudry and White Reference Beaudry, White and Claassen1994; Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Mills, Herr, Burkholder, Aiello and Thornton2018; Rautman Reference Rautman2012; Yellen Reference Yellen, Walde and Willows1991). If women (or nonbinary/transgender) archaeologists are more likely to consider gender, as my analysis of household archaeology publications suggests, then women’s lower submission rate could partly account for the dearth of gender analyses. To address this problem, journals could actively solicit submissions by women and other underrepresented groups (see Fladd et al. Reference Fladd, Kurnick, Laura E., Nala, Sarah, Sasha and Katelyn J.2026), although this would not remove structural barriers. As Hutson and colleagues (Reference Hutson, Castro and Teruel2025) discuss, women archaeologists are disproportionately employed in teaching-focused academic positions, which means they have less time and fewer incentives to write grants and publications. The urge to play it safe, anticipating critiques and rejections, likely also reduces the gender-focused submissions to journals (see the discussion of “hysteresis of habitus” in Kurnick and Fladd Reference Kurnick and Fladd2026). It might feel less risky to place challenging work in an edited volume, but that does not contribute as much to the mainstreaming of gender archaeology (see Conkey Reference Conkey2003).

In my experience, the culture of US academic archaeology is slow to change, despite the outwardly progressive politics of many practitioners. US archaeologists have been particularly reluctant to make the archaeology of gender overtly political. In 1997, Conkey and Gero described US archaeologists’ resistance to engaging with gender theory, feminist critiques of science, and feminist practices, despite the potential of these resources to enrich and expand our field (see also Engelstad Reference Engelstad1991; Geller Reference Geller2009b:66; Hanen and Kelley Reference Hanen, Kelley and Embree1992; Tomášková Reference Tomášková2007:270–271). Nevertheless, Marie Louise Stig Sørensen (Reference Sørensen2000:4–5), a Danish archaeologist then based in the United Kingdom, blamed feminist politics for gender archaeology’s marginalization. Ericka Engelstad (Reference Engelstad2007:223–228) later documented how multiple British archaeologists rejected feminist politics in an attempt to make the archaeology of gender more mainstream and to preserve the perceived objectivity of the research. In the same journal issue, Wylie (Reference Wylie2007) argued that Anglo-American archaeologists had failed to recognize the role of feminist theorizing (in other disciplines, nations, and languages) in making an archaeology of gender possible. If the goal of avoiding feminist scholarship and activism was to integrate gender into mainstream archaeology, then this seems to have backfired, as Conkey (Reference Conkey2003) and Moen (Reference Moen2019) observe.

In contrast, archaeologists in Norway created a “safe space” for feminist archaeology in the journal KAN (Dommasnes and Montón-Subías Reference Dommasnes and Montón-Subías2012; Engelstad Reference Engelstad2007; Skogstrand Reference Skogstrand and Varela2023). Lisbeth Skogstrand (Reference Skogstrand and Varela2023:328–329) describes how in the 1970s, Norwegian feminist scholars advocated for a “double strategy” of publishing in both mainstream journals and dedicated women’s studies journals. For archaeology, this resulted in the founding of KAN in 1985. For a decade, KAN published a mix of archaeological research, theoretical debates, project descriptions, reports on gender in the workplace, and early and experimental drafts, mainly by Scandinavian women and in Scandinavian languages. This explicitly political endeavor seems to have fostered creativity. Conversations in KAN contributed to the development of an archaeology of gender, influenced by larger trends in the social sciences and humanities (including postprocessual archaeology) but often preempting shifts in Anglophone archaeology. Engelstad (Reference Engelstad2007:221–222) argues that KAN had an important impact on Norwegian and Swedish archaeology. The journal gradually dissolved after 1996, when, in an attempt to reach a larger audience, the language was changed to English and the format became more traditional (Engelstad Reference Engelstad2007:221). Skogstrand (Reference Skogstrand and Varela2023:355) speculates that these moves may have sacrificed the publication’s “safe space” quality.

In the United States and broader English-speaking world, the fields of geography (Tomášková Reference Tomášková2007:265) and history have also created potential safe spaces in the form of academic journals. Geography has Gender, Place, and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography. History has multiple journals: Gender and History, Journal of Women’s History, Journal of the History of Sexuality, and Women’s History Review. Rather than marginalizing, these forums contribute to the mainstreaming of gender research in history, as seen in the makeup of academic departments and in the job advertisements described above. In cultural anthropology, feminist ethnography is a long recognized genre (Tomášková Reference Tomášková2007:267–268). However, the journal Feminist Anthropology was founded recently, in 2020, and only two articles on archaeology had been published there as of May 2025.

Although the SAA has interest groups and committees related to women and gender, archaeologists in the United States do not have a dedicated venue to publish new or challenging ideas on these topics. Outside of historical archaeology journals, the UK-based Journal of Social Archaeology and the newer Feminist Anthropology are promising places to submit provocative gender-related research. In addition, the international Archaeologies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress currently has a collection on “Gender Archaeologies” open for submissions. The first issue of Archaeologies, published in 2005, featured a discussion by Conkey on the intersections of feminist and Indigenous archaeologies, and Moen’s (Reference Moen2019) article also comes from Archaeologies. It is possible that publishing in these journals, rather than the mainstream archaeological journals analyzed above, is more productive for advancing the archaeology of gender. However, to realize the “double strategy,” research developed in the safer spaces must then be integrated into journals like American Antiquity and Latin American Antiquity. As a community of anthropological archaeologists, we could make this push from the bottom up by changing our submission practices.

Conclusions

My analysis of publication and citation trends has been brief and exploratory. Future analyses could go deeper into the content of the journal articles, journal impact factors, citation networks, and punishments/rewards other than citations. For now, I summarize the main findings here:

• As others in this themed issue discuss, women archaeologists still do not publish on par with men in major journals, even within household archaeology. This situation has improved somewhat since 2010.

• When women do publish on household archaeology, their work is as highly cited as men’s.

• Since the year 2000, interest in gender-focused household archaeology has held steady, with about half the articles mentioning gender, women, children, or (very rarely) feminism. Women authors address gender at a higher rate. Gender has been more successfully incorporated into the subfield of historical archaeology.

• In terms of citation counts, neither men nor women are rewarded or punished for focusing on gender within household archaeology.

So why was so little progress made between the 2003 article by Conkey and the 2019 article by Moen? Why has gender not been more fully integrated into archaeology? I hope that these preliminary results encourage more researchers to write and submit articles that focus on gender, women, children, and feminist theory to mainstream archaeology journals. After reflecting on the scholarship discussed above, I offer some recommendations:

• Archaeology is political, and our interpretations are colored by our biases, assumptions, and perspectives. Therefore, we should not be afraid to employ feminist theories and practices. We should be explicit about our positions and theoretical frameworks, rather than pretending objectivity. This does not mean saying whatever we want or abandoning the constraints of the material record.

• We should embrace the uncertainty and incompleteness of the archaeological record, because it is all we have. All archaeological interpretation involves speculation. Even as scientific methods advance, we should complement quantitative data with humanistic resources, such as historical records, ethnography, and iconography. We should not ignore or marginalize cases that contradict the norms of our study areas.

• US archaeologists could attempt the Norwegian “double strategy” described here, simultaneously submitting gender-focused work to more innovative “safe space” journals and mainstream journals.

• Anthropology departments should seek to hire archaeologists with research and teaching interests in the areas of gender, childhood, sexuality, feminist theory, and queer theory.

• Academic journals should encourage submissions by women and other underrepresented groups, and universities should address inequities that affect submission rates (see Fladd et al., this Reference Fladd, Kurnick, Laura E., Nala, Sarah, Sasha and Katelyn J.2026).

In this article, following many cited feminist scholars, I have attempted to make my own standpoint and positionality clear. It feels risky to abandon the seemingly objective “view from nowhere,” but I hope that the result is more self-reflexive and ultimately truer (see Haraway Reference Haraway1988). Returning to my self-interrogation, I am sure my own biases about gender influenced my trajectory through graduate school and my dissertation project. My sense that women archaeologists could achieve the same level of prestige as men archaeologists within household archaeology is supported by the citation data. However, my reluctance to engage with gender and feminist theory is not justified by those data. Finally, considering the relationship between archaeological content and sociopolitics has, for me, generated new insights and ideas about gender in archaeology.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Samantha Fladd and Sarah Kurnick for insightful feedback on this article and for organizing this issue and the preceding SAA symposium. I greatly appreciated the ideas of the other participants. Nisrine Rahal, Nicole Mathwich, and François Lanoë also provided helpful suggestions in informal conversations. Heather Barnes of the Z. Smith Reynolds Library at Wake Forest University taught me how to use MAXQDA. This article was completed in part thanks to a Junior Research Leave from the same university. Three anonymous peer reviewers gave valuable comments that improved this piece.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant funding from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Data Availability Statement

See the open-access online dataset (MacLellan Reference MacLellan2025) for spreadsheets of coded publications and citation counts. Readers should be able to reproduce the searches and statistical tests described in the article.

Competing Interests

The author acknowledges none.