The concept of “democracy” (or démocratie, demokratie, democrazia, democracia, etc.), has always been associated with ambiguity and pluralism in its meanings, practices and underlying cosmologies (heretofore “democracies”). Famously, Reference GallieW.B. Gallie (1956: 184) saw democracy as an essentially contested concept: “the concept of democracy is extremely vague, but not, I think, hopelessly so. Its vagueness reflects its actual inchoate condition of growth; and if we want to understand its condition, and control its practical and logical vagaries, the first step, I believe, is to recognize its essentially contested character.”

We consider this dynamic of many democracies to have developed early and—crucially—independently from ancient Greece across time and space, culture and language (see, for example, the development of the hui in traditional Māori culture as explained by Smith et al. in this issue; but also Reference StasavageStasavage, 2020). Ancient or “early” democracies have been recorded in polities across the wider Mediterranean and Africa (e.g., Phoenicia, Mossi, Songhai, Mali, Kongo, city-states along the “Swahili Coast,” ancient Egypt,Footnote 1 Kush), West Asia (e.g. Assyria, Babylon, Sumer) and India (e.g., Indus Valley & Vedic cultures). They are credited by today's democracy historians (e.g., Reference Isakhan and StephenIsakhan and Stockwell 2011, Reference Isakhan and Stephen2012; Reference KeaneKeane 2009; Reference Muhlberger and PhilMuhlberger and Paine 1993; Reference SchemeilSchemeil 2000; Reference StasavageStasavage 2020) as having had various practices—such as village-level meetings—that many people today would label democratic to varying degrees. Further, democracies’ meanings and practices exist today under names different than the signifier “democracy”—such as the Māori manapori, the Telugu ప్రజాస్వామ్యం (Prajāsvāmyaṁ), the Confucian concept of 议 (Yi, Footnote 2 or the Chinese concept of 民主 (mínzhŭ, see Reference ShiShi 2021).

Should Plato's followers, advocates for the one ideal meaning of democracy to rule them all, take umbrage with the foregoing paragraph, we encourage them to quarrel with Reference JacobsenThorkild Jacobsen (1943), Reference NaessArne Naess (1956), Reference ChristophersenJens Christophersen (1966), Reference BernalMartin Bernal (1987), Steven Muhlberger and Phil Paine (1993), Reference MarkoffJohn Markoff (1999), Reference PerryGlenn Perry (2000), Reference SchemeilYves Schemeil (2000), Reference KeaneJohn Keane (2009), Benjamin Isakhan and Stephen Stockwell (2011, 2012), Reference FukuyamaFrancis Fukuyama (2011), Reference RobinsonEric Robinson (2011), Mark Chou and Emily Beausoleil (2015), Reference Kurunmäki, Jeppe and Henk teJussi Kurunmäki et al. (2018), Reference Borlenghi, Clément, Virginie, Liliane and Jean-CharlesAldo Borlenghi et al. (2019), Reference StasavageDavid Stasavage (2020), Boaventura de Sousa Santos and José Manuel Mendes (2020), Reference Posada-CarbóEduardo Posada-Carbó (2020), and the list goes on. Here it suffices to say that Aristotle is credited by Reference NaessNaess (1956) with giving seven different definitions of democracy in his Politics and the number of definitions of what democracy means and how it is practiced have only continued to grow since then.

What follows in this introductory article to a special issue on the marginalized meanings of democracy is, firstly, a brief explanation of the lexical method for finding democracies. Secondly, we describe an imbalance in the study and usage of the democracies to show that certain ones, such as direct democracy or deliberative democracy, have lately been given the lion's share of attention by scholars and lay practitioners alike. This imbalance, we argue, is to the detriment of other, equally deserving, concepts of democracy, which remain overshadowed by their more famous and currently fashionable cousins. This lack of attention reflects the persistence of Western-centered understandings of democracy (Reference MinMin 2014), which, as Eva Cherniavksy (2021) warns, could lead Western polities into Thucydides’ democide trap. This brings us, thirdly and lastly, to the argument that by paying attention to these marginalized conceptions of democracy we contribute to the contemporary struggle against the “march of authoritarianism[s]” (Reference BerberogluBerberoglu 2020).

The study of democracy's marginalized meanings contributes to this struggle in three important ways: (1) it offers a greater number of alternative democratic practices and democratic innovations (an expanded democratization toolkit in short); (2) it provides a global democracy conservation project that is designed to both rescue the democracies from obscurity and share them with as many people as possible (new possibilities for diffusion); and (3) it makes a contribution to the decolonization and decentering processes of Western-centric democratic theory (new opportunities for inclusion). Put together, these three efforts can empirically and conceptually demonstrate that the concepts and practices of democracies now under the radar of Western-dominated democratic theory have more to offer than a set of majoritarian electoral institutions—which seem to be faltering in this opening of the twenty-first century—or notions of direct democracy, as pushed of late by illiberal populists (Reference UrbinatiUrbinati 2014).

The Lexical Method for Understanding Democracy

Traditionally, democracy has been understood in two guises: normative and analytical (Reference SetäläSetälä 2021). The normative method, whose champions include Robert Dahl, Jurgen Habermas, John Rawls, Nadia Urbinati, Bonnie Honig, Donnatella della Porta, Mark Warren, and John Dryzek, among many others, requires an a priori theory of what democracy is and, therefore, both where it should be going and how it gets there. The analytical method, whose champions include Giovanni Sartori, Leonardo Morlino, David Collier and Stephen Levitsky, Daniel Ziblatt, John Keane, Anna Luhrmann, Wolfgang Merkel, and Pippa Norris, among others, requires an observation of how democracy is manifested “in real terms”—both presently and historically. For the analysts, the focus, in prime at least, is not on what democracy should be (such is the concern of the normativists) but rather what it is, and has been, which is ascertained through empirical study. Reference Schmitter and Terry LynnSchmitter and Karl (1991), for example, focused on what democracy is, and is not, and what makes it possible.

Of course, there has been and there remains a tremendous degree of overlap between the normative and analytical traditions as each can inform and lead to the other (for an opposing view focusing on the gap between normative and analytical conceptions of democracy, see Reference Dufek and JanDufek and Holzer 2013). Indeed, some mentioned here may even identify differently to how we have categorized them.

The lexical method (e.g., Reference GagnonGagnon 2021a, Reference Gagnon2021b) to understanding democracy depends on both the normative and analytical approaches as it is through these contexts that words and concepts of democracies are generated. And the lexical method can, also, eventually lead to bridging the divide between normative and/or analytical guises. But its starting point is different to the normative and the analytical. Rather than beginning with either a theory or an empirical instance of democracy, it starts instead with words and concepts. “Representative democracy” is one of them but so, too, is “maroon democracy,” “flatpack democracy,” or “Vedic democracy.” Some of these words, like “representative democracy,” are established, used often, and therefore result in a corpus of publications tens if not hundreds of thousands of discrete units deep. Other words, like “Vedic democracy,” are newer to the Anglo-Western attention, are consequently not often used, and resultingly appear in far fewer publications—around a dozen in this case as can be found in conventional searches using the English language.

We have taken the lexical method as a point of departure for framing this special issue for two reasons. First, it captures a greater diversity of democracies than normative or analytical approaches can. This is despite the fact that the normative and analytical approaches create this diversity—they simply do not keep track of their creations.Footnote 3 Lexicologists of the democracies are, in this regard, something akin to Walter Benjamin's ragpicker roaming Paris or other luminary cities (Reference SalzaniSalzani 2009: Chapter 5), the Lepidopterist roaming pastures, estuaries, and woods in search of butterflies, or even the youngest of the Brothers Grimm who gathers stories to build a living archive (see Reference GoenagaGoenaga, 2021). They are each in search of unique specimens for collection and cataloging, study and configuration, exposition and narration. The lexical method uncovers a richer field of democracies to work with and, crucially, the opportunity to at least initially wager that all democracies are created equal and are, therefore, deserving of equal time under both intellectual and pragmatic suns.

Such an equality among the democracies is certainly not the habit of the normative tradition. It is equally odd to find among the analytical tradition. There is usually some value at play that puts one, or a set, of democracies above the others, at least those others that are known of which, as will be suggested, is a small portion of the number collected to date.

Second, the lexical method is suitably positioned in its epistemology to use the empirical methods more commonly deployed in the field of digital, big data humanities (Gagnon and Fleuß 2020: 7–9). This is a land of immense corpuses, coding, software, virtual computing, reliance on algorithms, and such, which can reveal or at least suggest—as these are early days in this approach—the prominence or neglect of the democracies relative to each other. And it is these very methods, we argue, that begin to demonstrate an imbalance between the understanding of democracies—so there is a rescue, conservation, and advocacy dynamic at play in what is to come.

Democracies are Imbalanced in the Literature

The exact number of democracies is not known but it is ever increasing. Reference NaessNaess (1956), for example, collected 338 definitions of democracy, Reference Collier and StevenCollier and Levitsky (1997) claim to have recorded 550 sub-types of democracy, and Jean-Paul Reference GagnonGagnon (2020) lists over 3,500 “linguistic artefacts” of democracy in the English language (the current count is now over 4,000). However, despite the growing number, some democracies are better known, and more widely practiced, or entertained as possible future practices (e.g., Reference Asenbaum and FredericAsenbaum and Hanusch 2021; Reference SawardSaward 2021), than the others.

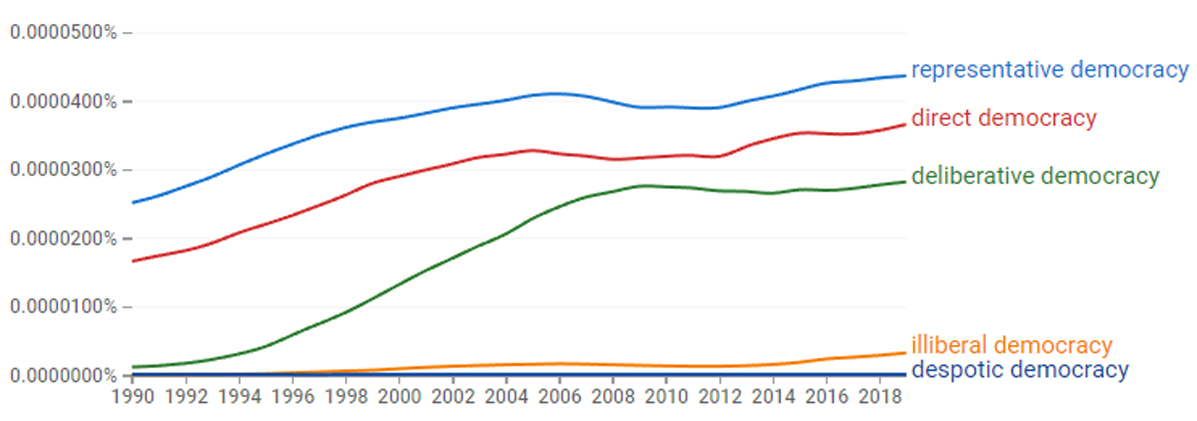

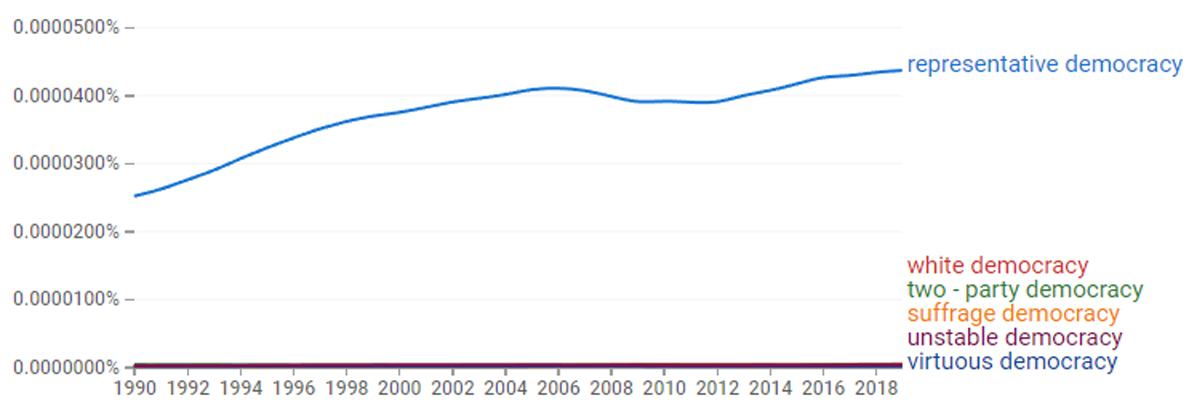

Consider the Google Books Ngram Viewer which can be used to show, at least among searchable books inside the Google Books storehouse, the use-frequency of democracy's concepts (here limited to the English language) over the period of, for example, 1990–2019 (or any other time period of your choosing—although it should be noted that the older the search field, the less reliable the result will be as there are simply fewer books in digital availability the further back in time we go). Figure 1 shows that “representative”, “direct” and “deliberative” concepts of democracy are prominent. “Illiberal democracy” has slowly been growing in use while “despotic democracy”—a concept we should be fiercely examining today (see, e.g., Keane's The New Despotisms [2020] or Applebaum's Twilight of Democracy [2020])—is yet to emerge from obscurity. Imagine inputting the several thousand democracies into this Ngram function: the gross majority will likely not share anywhere near the use-frequency of “representative”, “direct” or “deliberative democracy”(see Figure 2 for a comparison against “representative democracy”).

Figure 1: Google Ngram search results for “direct democracy,” “deliberative democracy,” “illiberal democracy,” “representative democracy,” and “despotic democracy,” 1990–2019.

Figure 2: Google Ngram search results for “representative democracy,” “white democracy,” “two-party democracy,” “suffrage democracy,” virtuous democracy” and “unstable democracy,” 1990–2019.

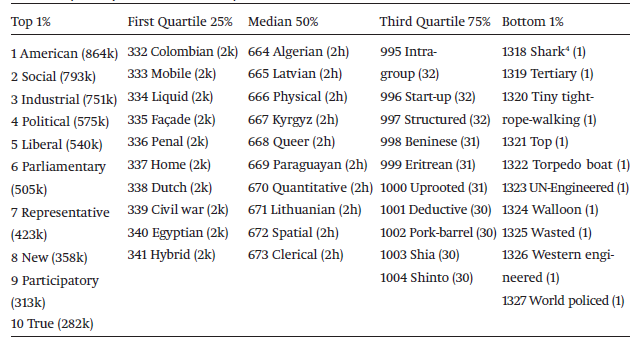

One pilot study, reported for the first time in this article, involved a partnership between the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and The Foundation for the Philosophy of Democracy (the Foundation) based at the University of Canberra. The purpose of the study was to find democracies through the lexical method. In 2017, the OED sent its entire list of 263,408 adjectives from the English language to the Foundation. These adjectives were then paired by the research team (Jean-Paul Gagnon, Reejay Alingcastre, and Daniel Stevenson) with the word “democracy” in pre- and post-nominal positions (e.g., “deliberative democracy” and “democracy deliberative”). Employing an exhaustive “scraper methodology” known as the “Alingcastre Battery,” the pilot study instructed a computer program to search 472,000 such pairings in the Google Books catalog. While the study revealed several difficulties as regards to working with Google Books, such as returning an enormous false positive rate, it did result in discovering more democracies. But it also led to a potentially provocative finding once a sample of 1,327 true positives (word pairings that demonstrated an intelligible definition or intention behind their production) were gleaned from the overall result. As can be seen in Table 1, the 10 most prominent conceptions of democracy in the 2017 Google Books corpus severely outweigh, in the frequency of their usage, the gross majority of other conceptions captured at that moment in time.

Table 1: A cross-section of the pilot study results with most prominent in use-frequency at 1 and least prominent at 1,327

Table 1 demonstrates where focus has been paid to various democracies in the Google Books catalog, which contains more than 10 million books and claims to be “the world's most comprehensive index of full-text books.” While the catalog is large, and arguably the world's best store for this type of publication, it should still be noted that it is limited in its focus on books and not, for example, essays or other types of publications—so it is indicative of a result that warrants further study. It does not take long, after moving from the top 10 performers, to notice a steep drop off from democracies who have been mentioned hundreds of thousands of times to the low thousands. There is, to say it with Occupy Wall Street activists, a valid “we are the 99 percent” complaint among the democracies on record.

We find this imbalance concerning as there is a great deal on offer, conceptually and pragmatically, from the forgotten, Othered, neglected, marginalized, democracies. Consider Phillip Becher et al.'s focus on “ordoliberal white democracy” (this issue). The authors explain that “white democracies” are far from being dealt with and that “liberal democratic polities remain,” today, “ridden with racist tendencies.” Together with Reference OlsonJoel Olson (2004: XV), they highlight how “white privilege is a ‘constitutive’ element, rather than an anti-democratic aberration, within the tradition of,” for example, “US-American liberalism.” It is especially through the concept of “white democracy” that critical race theory meets democratic theory to call out racism in contemporary liberal structures. There is significance in this as it challenges racial power and pushes for the further emancipation of peoples of color in liberal democracies.

There is, too, the contribution of Manuel Kautz (this issue) who argues for the analytical and normative utility of Reference GreenJeffrey Green's (2010) “ocular democracy” in politics today. Analytically, ocular democracy frames citizens and residents as spectators of politics—people who listen to the voices of, and watch the movements of, political leaders. They do this as they are looking for authenticity, or candor, and use this gauge to determine if leaders are, for example, relatable and therefore trustworthy. Normatively, ocular democracy argues that leaders should not be in control of their publicity, as this diminishes candor and can lead to a further distancing between leader and led or representative and represented. This, of course, is a gap that has been yawning for the last century in countries like the United States and one that neither liberal democracy nor representative democracy have been able to respond to. Enter ocular democracy and the possibilities for addressing that gap emerge.

Specimen examples such as these could keep being given, likely extending into the hundreds, if not thousands, of pages.

An Objection to the Imbalance

The reader, however, could take issue with the reliability of the research into the Google Ngram function or the Google Books catalog, preliminary as it is (Reference WhiteheadWhitehead 2021). So, we tack, instead, into a different epistemic paradigm in support of our point: that of the storehouse of lived knowledge held in, for example, your mind (Reference NishiyamaNishiyama 2021). One test is to attempt the task in Figure 3 (below).

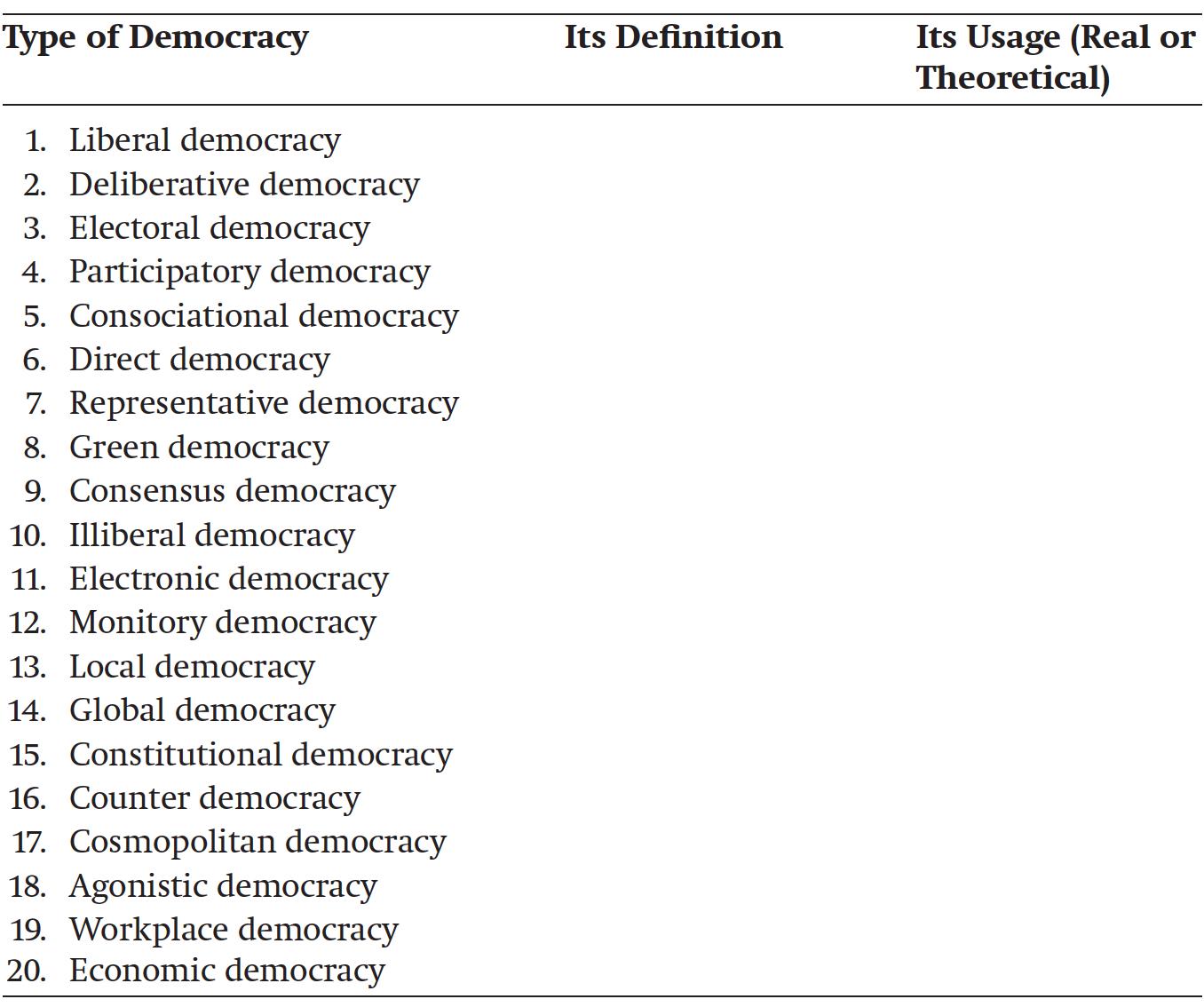

Figure 3: Provide a definition for each of the twenty types of democracy listed below and explain their usage.

To the professional student of democracy, such a task is likely going to be easier than a weekend crossword puzzle. But consider the difficulty of completing this task by those who are not in the profession or habit of studying the democracies (i.e., the “lay community”): How many from that category of persons could even answer half of the questions “correctly” and demonstrate the acuity to know that there are multiple, contested definitions and uses for each of the types of democracy listed?

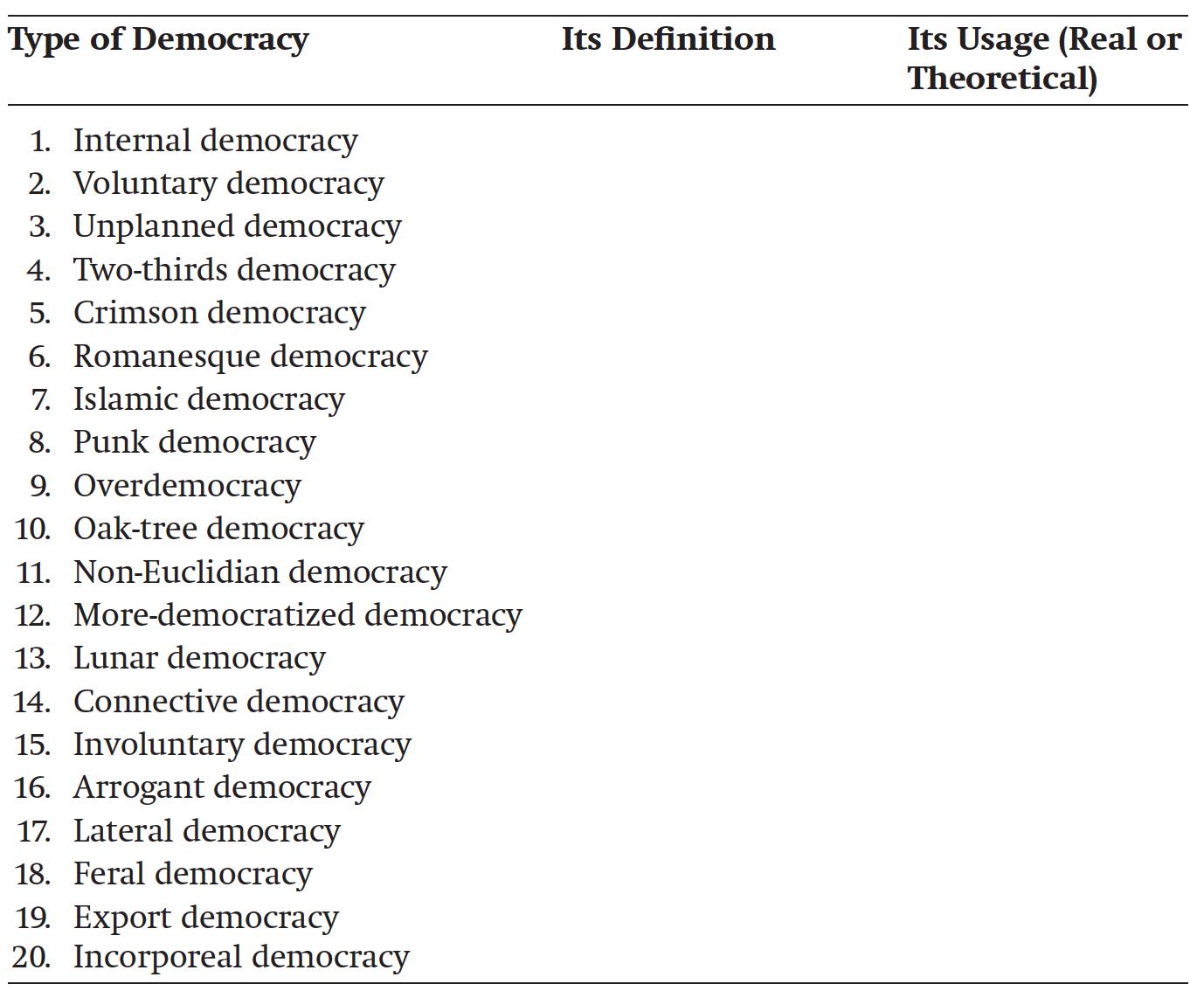

But here is the rub: those types of democracy listed in Figure 3 may be considered “well-known.” Try, for the sake of comparison, completing the same task given in Figure 4 (below). Uncertain as to how to handle most? Stumped by half? Are you miserably clasping to “export democracy” or “more-democratized democracy” with the thought that, at least here, are more epistemically definitive or ontologically certain grounds?

Figure 4: Provide a definition for each of the twenty types of democracy listed below and explain their usage.

To some, such as Christopher Hobson (in this special issue), this game may pose an unnecessary distraction. The critic's thinking goes as follows: those types of democracy in Figure 4 do not matter as much as those listed in Figure 3 as it is history, power, and circumstance (present need as driven by problems) that dictate which concepts sink and which concepts swim. Certain values such as liberalism, as Hobson argues, matter greatly in our current political moment, and there is risk to our political future if it is not protected and advanced more than other tenets central to different democracies.

The risk, as Hobson details, in focusing on the marginalized democracies is that we may take our eye off the presently imperiled liberal ball and lose the game of democracy altogether. This is possible, as Reference PauschMarkus Pausch (2021) has recently argued, because democracy requires democratic conditions to survive. Maybe this means liberally-oriented conditions, such as rebelliousness—a core concern for both Pausch and his muse Albert Camus—which is not tolerated in illiberal settings. Perhaps keeping this danger in mind is what will be needed as the lexical method unfurls into the future of democracy research. Or, instead, we could embrace the need to understand these marginalized democracies and view such an approach as our best hope against growing illiberal trends. Perhaps it is not democracy that is failing but simply its liberal or representative types (and the political economy underpinning them).

Against the “March of Authoritarianism[s]”

An impressive number of fields in the humanities and social sciences, but also the political branches of various natural science associations, have claimed that “democracy” is presently on the ropes. It faces what Berch Berberoglu terms the recent “march of authoritarianism[s]” in at least three guises. The first is a successful manipulation of Schumpeteresque electoral democracies by new despots (e.g., Reference KeaneKeane 2020). Many have, for example, been witness to this dynamic in Hungary (e.g., Reference BogaardsBogaards 2018), Poland (e.g., Reference Guasti and ZdenkaGuasti and Mansfeldová 2018), and Belarus (e.g. Kazharski and Makarychev 2021). The second is a perceived strengthening of full or semi-authoritarian polities, the “classic” non-democracies, such as Singapore, China (DPRC), and Russia (e.g., Reference Heldt and HenningHeldt & Schmidtke 2019) in the face of a United States that is awakening to its own illiberal credentials (e.g. McCann and Kahraman 2021). The third, and last, is the strange success—especially online—of right-wing political leaders and of minor or fringe communities who demonstrate dangerous and retrograde ambitions for neo-Nazism, anti-feminism, bigotry against members of the LGBTQIA+ community, petro-masculinity (Reference DaggettDaggett 2018), racism against non-whites or non-(insert their “correct” sort of religion here), and an affinity for violent political action such as rushing the US national Capitol/Rome's Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro (https://www.cgil.it) or waging viral violence against their communities in the forms of unmasked anti-vaxxer protests.

It is our hope that this focus on the marginalized democracies will help to ignite a direction of democratic action, research, and advocacy to address the pressing issues of our times and tilt the balance in favor of democracy and not autocracy or authoritarianism. We are, therefore, of the opinion that studying marginalized democracies through the lexical method can yield at least three benefits.

The first benefit is that it generates a higher number of alternative democratic practices (political, economic, and social) and democratic innovations for people in the world to adopt and thereby can offer a toolkit for democratic renewal and reform. Take “maroon democracy” for example. This concept is inspired by the story of eighteenth-century and early nineteenth-century enslaved peoples held captive on islands like Mauritius, then a French plantation colony and now a French tourism neocolony. A “maroon,” or marron in French (or nèg mawon in Creole), holds three meanings: (1) it designates a person stranded in a difficult place without hope for escape (so, to be marooned); (2) it means a person of purple-brown, or chestnut, skin color; and (3) it means “black people” who have escaped slavery, including their descendants. The democracy of the maroons is characterized by a multiethnic, multilinguistic people that have escaped slavery to establish a self-sustaining and autonomous community. Its first, of two, distinctions is political: the democracy of the maroons is a tenuous place that defies slavery; it is a symbol of rebellion against forceful authoritarianism; it is a defensive position to protect those who have freed themselves, and it holds the promise that those persons who make up that community can both self and collectively determine their futures. The second distinction is that maroon democracy can be transitory. For example, some of the freed in Mauritius built their maroon democracy on a mountain called Le Morne Brabant. Some of its members relied on their mountain stronghold for safe harbor before finding passage by sea to more favorable locations. Today, maroon democracy can be used to explain peoples’ desire to escape from “bad” and “bullshit” work, or neoliberal authoritarianism more generally. It can also concretize directions for how to make routes of escape and safe spaces (again: social, economic, and political) for other escapees to join them in. This is a strikingly different outcome to the analytic perceptions and normative directions that emerge from, say, liberal democracy as maroon democracy—in its contemporary register—rebels against the political economy and social mores that sustain liberal democracy.

The second benefit of the lexical method is that it can counter authoritarianism through an innovative means for rescuing, conserving, and sharing the democracies in an open and peer-reviewed, wiki-style, “encyclopedia of the democracies” (Reference GuastiGuasti 2021). This would be similar to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy in its peer-review and editorial robustness and Participedia in its case coverage and inclusion of communities. Such an encyclopedia of the democracies can serve as a means to rescue marginalized conceptions of democracy from obscurity by publicly recording them, sharing their meaning(s) via social media and other outlets, organizing and making available the publications that used them (so, an online library), analyzing these publications for academic and political purposes, and so forth.

It can also provide a conservational service in that, after rescue, the encyclopedia makes it difficult for the democracies to be effaced—they are there for public engagement and can be made more useful to democrats throughout the world by means of translation and so forth. Authoritarian governments would, for example, need to block their residents’ access to the website (which is the forthcoming demthings.org) or to all of the key words and phrases the conservationist community of democrats uses in its own media-rich, multiplatform, communications. This dynamic of conserving democracies could make good trouble of its own in demonstrating the bounty of ideas and practices that do exist in the world of the democracies. Clever despots are, indeed, managing to turn electoral democracy, even constitutional democracy, to their purposes of disguising authoritarianism as illiberal democracy (Reference Bustikova and PetraBustikova and Guasti 2017) but best of luck to them in working their “dark arts” upon the thousands of democracies now rescued and those potentially many thousands more awaiting discovery.

The third benefit to using the lexical method is that it reveals how few of the democracies are “owned” or are “claimable” by American and other European or Western empires. They come, instead, from a far wider world (as Wade Davis highlights in his interview within this special issue). The Othered democracies express a dynamic that is usually the hallmark of subaltern peoples—their existence is problematic for those who do not know of them, who ignore them, who disrespect them, and who can wage war on them. To know of the Othered, especially to see them, is to remind the powerful that there are other possibilities, histories, cosmologies—they render palpable the criminal sentiment of the status quo for those who benefit from the present arrangement. If democratic theorists and practicing democrats can know about the democracies, the many in number and how they are marginalized, it is perhaps inevitable that they will come to question the reasons as to why they know so few of them and to ask what can be done about this situation. From our gaze to blame is, especially, colonialism and Western-centric imperialism: particularly in how our field of democratic theory has grown within Western universities, particularly due to the prominence of the English language in academia, particularly because of the sheer number of white heteronormative males as researchers, authors, and teachers, whose words are still taken, by too many, to mean “democracy itself.” Paying attention to the marginalized democracies can, in short, participate in ongoing efforts at decolonizing the intellectual and practical pursuits of democracy but also decenter the West from the cannon of democratic theory.

In Place of Conclusions: The New Beginning

It is in this spirit of hope and strategy that this special issue unfolds. It begins with the recognition that there are, empirically speaking, many meanings, pracAtices, and cosmologies involved in the democracies. This is a position derived from the lexical method to understanding democracy as this method can capture the words of democracy left behind by the more traditional methods of understanding democracy: the normative and the analytical. From there we come to terms with an existing imbalance in focus between the democracies: some are clearly more popular than others, at least insofar as can be gleaned from the Google Ngram instrument and the Alingcastre Battery of the Google Books catalog.

Outside of how this focus on marginalized democracies may assist democrats in the struggle against the march or rise of authoritarians and authoritarianisms—which we explained earlier—are more scholarly considerations that we hope may be taken up in future research. These considerations include: (1) the question over missing democracies, (2) intersectionality among the democracies, and (3) the lack of a stable digital corpus containing publications that use one or more of the democracies in their pages. Each is explained in brief as follows:

1. Examining the list of democracies led to categorizing them: here are, for example, ethnically related ones; there are ones tied to specific cities or regions, and so forth. There are many ethnicities and cities, however, which do not appear in any digital catalog that we have searched through. But chances are, one or more of the democracies will be used by members of those ethnic groups or cities once put to observation. So just as there are many democracies already found by using the lexical method, they point to many gaps within their categories. Filling these gaps could prove to be a productive space for democracy's ethnographers to be working in.

2. Also recognized in the examination of the democracies is that the authors who invoke these many conceptions in their publications tend to be male, tend to come from European ancestry, tend to be white, tend to work in English, and so forth. A great deal, we think, can be learned from the bibliographic nature of at least this lexical understanding of democracy by applying critical feminist, queer, Black, and Indigenous methodologies to them as Reference AsenbaumHans Asenbaum (2020) advises we should be doing more generally in the study of democracy.

3. The third and final consideration for future research is a methodological concern. Digital studies into the lexicon of democracy are hindered by algorithmic filtering and recommendation. In short, findings will depend on the available lexicon that is shaped by the politics of relevance enacted by algorithms, copyrighters or authors deciding to take down their content from the internet. This was noted in relation to “shark democracy,” which is now missing in the Google Books corpus and by the rules of the game can be said to now no longer exist. It would be inestimably more helpful if researchers had access to a stable, secure, digital, library of publications, in which democracy's conceptions appear. Researchers can also think about a duty to archive digital sources for future researchers in case these sources are taken down or the hosting websites or platforms cease to exist. Shifting sands could transform into stable ground with such a move and lead, we believe, to more dependable results, especially from studies that deploy big data analytics driven by computational means.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Emily Beausoleil, Afsoun Afsahi, and Sophia Schubert for their supportive comments on earlier versions of this article.