1. Introduction

People have an internal sense of how much they know about finances and how well they manage their money – their financial confidence. Financial confidence matters, as it is linked to financial behavior (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Maillet and Koffi2022; Robb & Woodyard Reference Robb and Woodyard2011). For example, financial confidence has been linked to better budgeting and saving (Grillo et al. Reference Grillo, Ward, Atlas, Porto, Xiao, Dunn, Fernbach, Jhang, Lynch, Sussman, Egan, Swift and Farming2018; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Maillet and Koffi2022), healthier credit behaviors (Atlas et al. Reference Atlas, Lu, Micu and Porto2019), greater likelihood of keeping up with bills, planning ahead financially (Palameta et al. Reference Palameta, Nguyen, Hui and Gyarmati2016), and positive financial behaviors such as having an emergency fund, paying off credit cards, having retirement savings, and insurance (Robb et al. Reference Robb and Woodyard2011). Financial confidence has also been linked to better emotional capacity to deal with financial anxiety (Jawahar et al. Reference Jawahar, Mohammed and Schreurs2022). The present research tests two interventions that aim to increase financial confidence among a group that tends to report particularly low financial confidence (women), with the goal of increasing confidence and engagement in positive financial management behaviors.

1.1. Financial confidence gender gap

Financial confidence is defined as people’s self-assessed financial competence and knowledge (Palameta et al. Reference Palameta, Nguyen, Hui and Gyarmati2016; Robb & Woodyard Reference Robb and Woodyard2011), independent of their actual financial actions and knowledge. Across the world and across the lifespan, women report feeling less financially confident (e.g., Bucher-Koenen et al. Reference Bucher-Koenen, Lusardi, Alessie and Rooijvan2017; Chen & Volpe Reference Chen and Volpe2002; Jha & Shayo Reference Jha and Shayo2022; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Maillet and Koffi2022; Palameta et al. Reference Palameta, Nguyen, Hui and Gyarmati2016; Preston & Wright Reference Preston and Wright2019; Wu Reference Wu2021). This gender gap in financial confidence remains unexplained by demographic variables such as income or education (Preston & Wright Reference Preston and Wright2019) and remains significant even after accounting for any gender gaps in objective financial knowledge (Angrisani & Casanova Reference Angrisani and Casanova2021; Chen & Volpe Reference Chen and Volpe2002; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Maillet and Koffi2022; Palameta et al. Reference Palameta, Nguyen, Hui and Gyarmati2016). For instance, a study with 1221 Canadian university students showed women reporting lower perceived confidence than men on four questions tapping a variety of self-assessed financial knowledge (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Maillet and Koffi2022). In a study of US adults, women were also disproportionately found to be underconfident – 69% of women versus 31% of men scored in the lowest quartile of self-perceived knowledge while also scoring above the median in actual objective financial literacy. This finding is echoed in Canadian adults who participated in the 2014 Canadian Financial Capability Survey (Palameta et al. Reference Palameta, Nguyen, Hui and Gyarmati2016), where just 19% of women with high actual knowledge (scoring in the highest quartile on financial literacy) also scored in the highest quartile on self-perceived knowledge compared to 29% of men with high actual and high perceived knowledge. In sum, women are particularly likely to have low financial confidence and increasing their financial confidence might be particularly important.

One reason for women’s lower confidence might be gaps in financial literacy between men and women (Bucher-Koenen et al. Reference Bucher-Koenen, Lusardi, Alessie and Rooijvan2017). Financial literacy is defined as “people’s knowledge of and ability to use fundamental financial concepts in their economic decision-making” (Lusardi & Mitchell Reference Lusardi and Mitchell2014; Reference Lusardi and Mitchell2023). It stands to reason that actual knowledge about investing, financial products, and financial management should be linked to confidence about financial decisions and knowledge. While studies assessing both financial confidence and financial literacy show these constructs to be independent predictors of financial behavior (Angrisani & Casanova Reference Angrisani and Casanova2021; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Maillet and Koffi2022; Palameta et al. Reference Palameta, Nguyen, Hui and Gyarmati2016; Robb & Woodyard Reference Robb and Woodyard2011), financial confidence (i.e., perceived knowledge) is moderately linked with financial literacy (i.e., actual knowledge) (Bucher-Koenen et al. Reference Bucher-Koenen, Lusardi, Alessie and Rooijvan2017; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Maillet and Koffi2022; Robb & Woodyard Reference Robb and Woodyard2011). For example, financial literacy, together with demographic variables, predicted up to 35% of the variance in financial confidence in a sample of Canadian undergraduates (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Maillet and Koffi2022).

Another reason for women’s lower financial confidence might be social beliefs. Specifically, beliefs about women being not as adept at mathematics as men (Nosek et al. Reference Nosek, Banaji and Greenwald2002; Smeding Reference Smeding2012) and being less financially capable than men (Driva et al. Reference Driva, Lührmann and Winter2016) persist as social beliefs (i.e., beliefs about what is “normal” or “typical” in the general population; Cialdini et al. Reference Cialdini, Reno and Kallgren1990). When salient, these stereotypical beliefs can negatively affect women’s decision-making (Coffman Reference Coffman2014; Carr & Steele Reference Carr and Steele2010) and impair comprehension of financial information, even when reading about topics related to finances that do not involve math (Tinghög et al. Reference Tinghög, Ahmed, Barrafrem, Lind, Skagerlund and Västfjäll2021). For example, the more women endorsed norms about women being less financially capable, the worse they scored on a financial literacy test (Driva et al. Reference Driva, Lührmann and Winter2016). In another study, the extent to which women believed that men tend to perform better on financial literacy questions than women was linked with experiencing more financial anxiety (Tinghög et al. Reference Tinghög, Ahmed, Barrafrem, Lind, Skagerlund and Västfjäll2021). Importantly, the reluctance of women to participate in stereotypically male fields is driven by detrimental self-assessments rather than fear of discrimination (Coffman, Reference Coffman2014; Bordalo et al. Reference Bordalo, Coffman, Gennaioli and Shleifer2019). In sum, social beliefs about financial ability and financial confidence in different social groups (including gender) might influence financial confidence.

1.2. Shifting financial confidence

Although there are many studies that have attempted to increase financial literacy (see Kaiser & Menckhoff Reference Kaiser and Menkhoff2017; Kaiser et al. Reference Kaiser, Lusardi, Menkhoff and Urban2022, for a review), far fewer interventions have attempted to increase financial confidence. To our knowledge, there have been only three experimental tests of interventions intended to increase aspects of financial confidence. First, an online study with 1035 Israeli men and women of working age showed that after trading stocks for several weeks, participants scored higher on a financial confidence measure and were also 32% less likely to answer “I don’t know” to financial literacy questions (Jha & Shayo Reference Jha and Shayo2022). No gender effects were reported. Second, university students who completed a 2.5-hour online course on financial education training focusing on investment knowledge reported higher financial confidence than a no-education control group after one week, after three months, and at a six-month follow-up (Grillo et al. Reference Grillo, Ward, Atlas, Porto, Xiao, Dunn, Fernbach, Jhang, Lynch, Sussman, Egan, Swift and Farming2018). A much briefer intervention was tested in a study examining confidence in one’s ability to recognize a good financial investment. This study (Grillo et al. Reference Grillo, Ward, Atlas, Porto, Xiao, Dunn, Fernbach, Jhang, Lynch, Sussman, Egan, Swift and Farming2018) recruited 521 crowdsourced Mechanical Turk participants, and showed that participants who engaged in a Google search task to find the answers to investment-related questions (e.g., “What is a Bear Market?”) reported increased confidence in their ability to recognize good financial investment compared to participants who received the answers to these questions without engaging in a search. Notably, all three previous interventions relate to some form of financial education component, and two of the interventions included an active, experiential learning component (practicing investment and stock trading, or actively searching for information about investment terminology). None of the studies examined financial behavior outcomes.

The present research aims to test ways to increase financial confidence in a group that tends to be underconfident: young women. Specifically, we tested two interventions against a control group in the extent to which they affect financial confidence directly after the intervention and one week and one month later. One of these interventions was grounded in knowledge acquisition (“find and explain” intervention), similar to previous financial education interventions (Jha & Shayo Reference Jha and Shayo2022; Grillo et al. Reference Grillo, Ward, Atlas, Porto, Xiao, Dunn, Fernbach, Jhang, Lynch, Sussman, Egan, Swift and Farming2018). Another intervention (“recall and share” intervention) took a different, novel approach and was broadly grounded in social norms principles (Reid & Carey Reference Reid and Carey2015). Stereotypical social beliefs can be influenced by providing counterexamples (i.e., changing the descriptive norms) or by shifting the social acceptability of a belief (i.e., changing the injunctive norms) (Rhodes et al. Reference Rhodes, Shulman and McClaran2020). For example, in young adult alcohol use research, changing descriptive social norms effectively reduces drinking and negative alcohol use consequences (Reid & Carey Reference Reid and Carey2015). Overall, this second intervention was based on the idea that calling to mind examples of women feeling confident about financial decisions (both oneself and others) will increase confidence. Both interventions were designed to be completed in a brief time frame, extending previous work by designing the intervention to be scalable to larger populations. In addition, the present study extends previous work by examining whether increased financial confidence has downstream effects on positive financial behaviors. Positive financial behaviors are defined here as behaviors that increase financial well-being, including beneficial savings and investment behaviors, adequate cash management such as paying bills on time and responsible credit management (Dew & Xiao Reference Dew and Xiao2011).

1.3. Present research

Given that financial confidence can be predictive of positive financial behaviors and well-being (e.g., Angrisani & Casanova Reference Angrisani and Casanova2021), the aim of this research was to examine two possible avenues to increase financial confidence among women – a typically underconfident group. To this end, we delivered a brief knowledge intervention and an equally brief social beliefs-based intervention. We examined whether each or both conditions measurably affected financial confidence in young women compared to a control condition. We assessed financial confidence prior to the intervention, directly after the intervention and at a one-week and one-month follow-up survey. In addition to financial confidence, we also examined participants’ financial management behaviors, including savings contributions, both of which have previously been linked to financial confidence (Angrisani & Casanova Reference Angrisani and Casanova2021; Jawahar et al. Reference Jawahar, Mohammed and Schreurs2022; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Maillet and Koffi2022; Palameta et al. Reference Palameta, Nguyen, Hui and Gyarmati2016; Robb & Woodyard Reference Robb and Woodyard2011). The study was reviewed and approved by the Carleton University Ethics Board and followed Tri-Council guidelines for research conduct. Full materials and data are available on OSF: https://osf.io/3pq69/.

2. Data and experimental design

2.1. Participants

Participants were recruited via different avenues, with rolling enrollment starting June 1st 2023 and ending December 20th 2023.Footnote 1 About half of the participants (n = 542) were recruited through the social media platform Instagram. Advertisements for the study were posted on Instagram and shared among Instagram users. The advertisement referred participants to an eligibility survey and those passing the eligibility requirements (female, 16–25 years old, living in Canada) were scheduled for a Zoom call with a research assistant, checking their age and ruling out bot fraud, based on showing a piece of government-issued identification document. To boost recruitment, we also posted the Instagram recruitment advertisement on the Student Research Participation system at Carleton University during the month of September 2023. Student participants (n = 100) were directed to the eligibility survey, and upon passing the eligibility requirements, they were directly emailed the link to the intake survey. Another part of the sample (n = 490) was recruited in parallel via the Prolific Academic crowdsourcing website, also starting June 1st 2023 and ending December 20th 2023. This website connects researchers to people who are willing to complete small tasks in return for pay and includes a rigorous screening process before enrolling participants, also including verification of age, gender, and Canadian residency. Prolific participants directly accessed the intake survey.

From the initially recruited sample, we flagged 13 participants as problematic (they were assigned to an intervention but could not access the website or complete it for some other reason) and these participants were excluded. The final intake sample included 1119 young women. The final sample had 99% power to detect even small effect size differences between four conditions. We overrecruited to account for potential attrition over the follow-up surveys. Of this sample, 1015 completed the weekly follow-up (91% retention rate) and 952 completed the monthly follow-up (85% retention rate). Table 1 portrays the sample statistics.

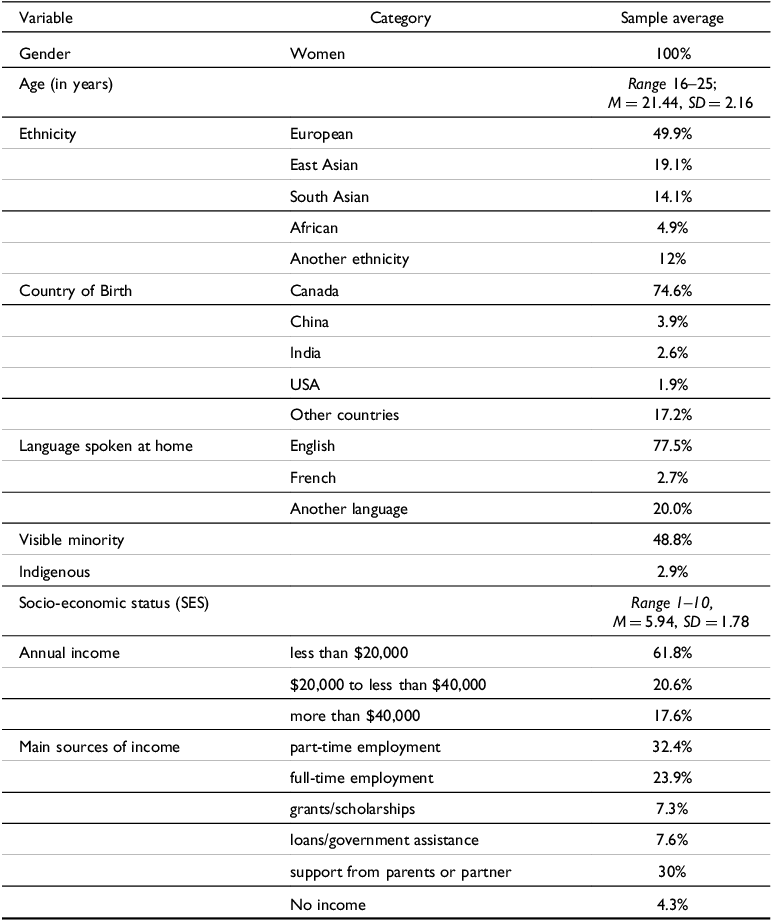

Table 1. Sample description

Note. Sample descriptions are based on the intake sample, not including missing data (less than 0.5% missing) (follow-up samples did not differ meaningfully on any of the descriptive variables). M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation. SES measured on a 10-point scale. Data collected in Canada in 2023 (Peetz & Howard Reference Peetz and Howard2024).

2.2. Procedure

After completing an online consent form where consent was indicated via a checkbox, participants completed an online intake survey assessing demographics, financial literacy and perceived literacy, an index of positive financial behaviors, saving contributions in the past month specifically, and reported baseline financial confidence before being randomly assigned to one of four conditions. Participants were randomly assigned to either the “find and explain” intervention condition, the “recall and share” intervention condition, a condition with both interventions, or to an empty control group. Assignment followed the principles of Block Randomization (using the software Qualtrics). Randomization tests are portrayed in Appendix A.

After the intervention, participants again reported financial confidence. At the one-week follow-up survey (completed on average M = 9.21 days, SD = 4.94 days after the intake survey), participants reported financial confidence and reported saving behavior in the past week. At the one-month follow-up survey (completed on average M = 33.95 days, SD = 6.95 days after the intake survey), participants reported financial confidence, an index of positive financial behaviors, and their saving contributions in the past month.

2.3. Interventions

In the “find and explain” intervention condition, participants were first asked to help with the building of a dictionary of terms that explain everyday financial concepts in plain language. They were first given suggestions of terms to explain (randomly selected from a larger list, e.g., “renters insurance,” “income tax,” “net pay.” A full list of terms and the exact instructions can be found in Appendix B) and asked to enter the term and a lay person definition on an online dictionary website (https://find-and-explain.netlify.app/). As it was added to throughout the study, this website included an increasing number of existing definitions over time, ranging from 50 definitions at the beginning of the experiment (pre-populated by experimenters) to over 400 definitions by the end of the experiment. Definitions were not edited or verified and participants could opt out of providing a definition (though judging by the number of unique entries on the website, less than 10% of participants did not complete this aspect of the intervention). Participants were then instructed to “Please browse the same website to read other definitions. We’d like you to find a financial term you feel you know understand better after reading about it.” They described the new financial term they learned about in a text box. All participants completed this part of the intervention and experimenters verified that the reflection described a term and the participants’ take on it.

In the “recall and share” intervention, participants were first asked to go to a website collecting financial confidence stories (https://recall-and-share.netlify.app/). This social beliefs-based intervention was two-pronged. First, participants first described a past instance in which they felt confident about a financial decision or behavior, which was then posted to the collection of personal stories on the site. Entries were anonymous but personalized with information such as a virtual avatar picture, age, and location (presented on a map). The stories were published immediately on the website. They described this experience in a text box. As it was added to throughout the study, this website included an increasing number of confidence stories over time, ranging from 120 stories at the beginning of the experiment (pre-populated by responses from pilot participants recruited from a university subject pool) to over 400 definitions by the end of the experiment.Footnote 2 Stories were checked by experimenters for compliance (confirming that all stories were positive and none contained rude comments/swearwords) but were not edited and participants could opt out of providing a story (though judging by the number of unique entries, less than 10% of participants did not complete this aspect of the intervention). Participants were then instructed to “Please browse the website to read other women’s stories of their financial confidence experiences. We’d like you to find an experience you find interesting or that resonates with you. Briefly recap or copy the experience below and state why this financial confidence story stands out for you.” All participants completed this part of the intervention and experimenters verified that the description described a confidence story and the participants’ connection to it. For a summary of the content of participants’ financial confidence stories and the stories they described as resonating with them, see Appendix C.

2.4. Measures

Unabbreviated materials are available in online supplements: https://osf.io/3pq69/. A list of main constructs can be found in Appendix D. Demographic variables assessed in the intake survey included age, ethnicity (whether they identify as visible minority, their ethnic or cultural background, and whether they are an Indigenous person), province of residence, country of birth, and language(s) spoken at home. Participants also reported on financial background: the sources of income, total personal annual income before taxes (in seven categories), and their subjective Socio-Economic Status on a 10-point ladder scale (McLaughlin et al. Reference McLaughlin, Costello, Leblanc, Sampson and Kessler2012). Participants also completed an 8-item Financial Literacy scale: They completed the “Big Three” items assessing financial literacy (Lusardi and Mitchell, Reference Lusardi and Mitchell2011) as well as five additional items assessing everyday financial calculations (e.g., “When grocery shopping, it is better to buy two of the 100g packages for $5 each or one of the 200g package for $12 each?”). We examined the score for the “Big Three” financial literacy scale (range: 0–3) and the score for the full eight-item financial literacy scale (range: 0–8). Participants were then asked to rate their perceived financial literacy score (“How many of the eight questions about finances you answered on the previous page do you think you got right?”) on a scale from 0 (none of them) to 8 (all of them).

Financial confidence was assessed with a 5-item measure (e.g., “How would you rate your level of financial knowledge about financial products and services?”, “How confident do you feel about managing your own money day-to-day?”) on 5-point scales, with higher numbers indicating greater financial confidence (α’s = .81–.84 across intake and follow-up surveys). This scale was created based on a variety of confidence assessments in the literature (Grillo et al. Reference Grillo, Ward, Atlas, Porto, Xiao, Dunn, Fernbach, Jhang, Lynch, Sussman, Egan, Swift and Farming2018; Philippot Reference Philippot2020; Robb & Woodyard Reference Robb and Woodyard2011).

At the intake survey and the one-month follow-up survey, positive financial behaviors were assessed with the 12-item Financial Management Behavior scale (Dew & Xiao Reference Dew and Xiao2011), where participants indicated how often they engaged in a variety of positive financial behaviors in the past month (e.g., “Paid all your bills on time,” “maintained emergency savings account,” “Maxed out the limit on one or more credit cards” (reverse coded)) on a scale from Never (1) to Always (5). Higher numbers indicate more positive financial behaviors (α’s = .73 and .74 in intake and one-month follow-up survey). In addition, we asked whether participants had contributed to a savings account in the last week (1 = yes, 0 = no). In addition, we asked whether participants had contributed to a savings account in the last week (1 = yes, 0 = no). At the one-week follow-up survey, participants were asked whether they contributed to a savings account in the last week, with a 4-point response scale (No, A little, A good amount, A lot). This variable was recoded into a dichotomous variable indicating whether they had contributed anything to savings or not (1 = yes, 0 = no). At the one-month follow-up survey, participants were asked whether they contributed to a savings account in the last month, with a 4-point response scale (No, A little, A good amount, A lot). This variable was recoded into a dichotomous variable indicating whether they had contributed anything to savings or not (1 = yes, 0 = no).

2.5. Data analysis

We performed a paired-samples t-test to verify our assumption that women underestimated their financial literacy at baseline, and tested correlations between financial confidence, three measures of financial literacy, and contributions to savings. To test whether women assigned to an intervention condition improved their financial confidence compared to women assigned to the control condition, we fit a factorial mixed effects linear model examining differences by study condition (Control, Find & Explain, Recall & Share, Both Interventions) and time (Pretest, Posttest, One-week, One-month) in financial confidence. A person-level random intercept accounted for the clustered structure of the repeated-measures data and the model was estimated by maximum likelihood. Post-hoc estimates of condition- and time-specific means and their pairwise differences were obtained by calculating predicted values from the model parameter estimates. Standard errors for predictions come from the model’s asymptotic covariance matrix (i.e., “delta method” standard errors; see Bauer & Curran, Reference Bauer and Curran2005). We used the same approach to fit a factorial mixed effects model predicting positive financial behaviors. For contributions to savings, we conducted chi-square tests and logistic regression analyses separately by time point to test for differences between conditions in the proportions of people contributing to a savings account in the past week. To check the robustness of intervention effects to demographic and study design confounds, mixed-effects and logistic regression models were repeated with covariates included (family income, age, and socioeconomic status).

3. Results

3.1. Initial checks

First, to examine the assumption that women would be underconfident, we compared participants’ actual scores on the financial literacy test with their perceived scores of how many items they believed were correct. A paired t-test showed that participants significantly underestimated their financial literacy score, t(1117) = 29.25, p < .001, d = 0.87, suggesting that they were, indeed, underconfident. Participants underestimated the number of correct answers they were able to provide by 21.5%. In other words, women knew more about financial concepts than they thought they did. Greater financial confidence at baseline (measured before the intervention) was linked to a higher financial literacy score across all 8 items, r = .15, p < .001, and across the “Big 3” items of the financial literacy test, r = .13, p < .001. Financial confidence also correlated with a higher perceived financial literacy score, r = .39, p < .001. Finally, participants with more financial confidence reported more positive financial behaviors, r = .42, p < .001. In sum, these preliminary analyses suggest that participants tended to be underconfident and that confidence was linked meaningfully to positive financial behaviors.

3.2. Intervention effect on financial confidence

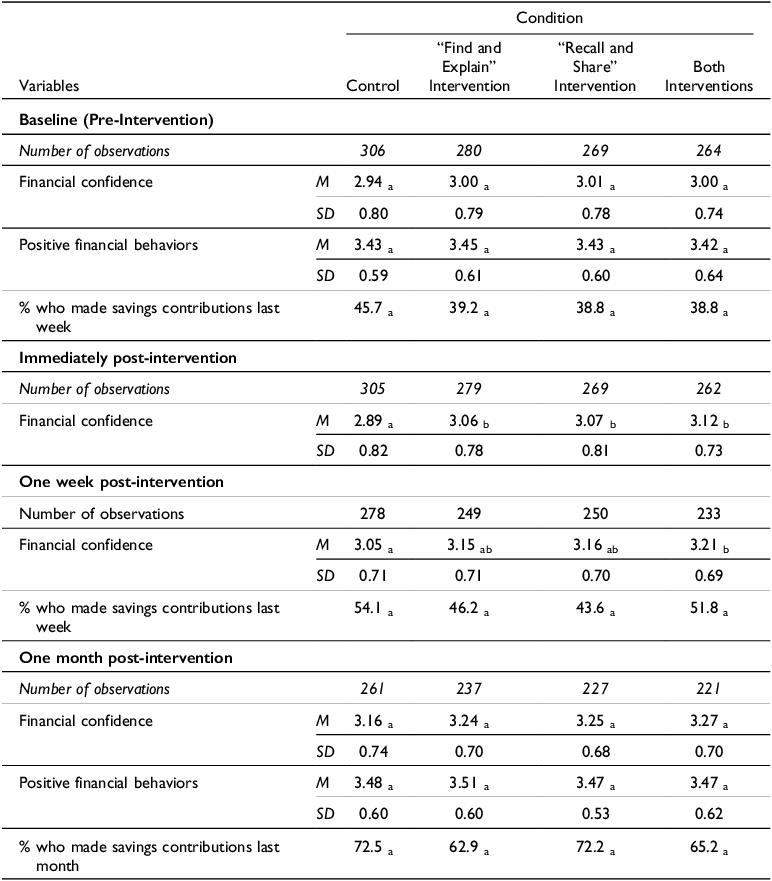

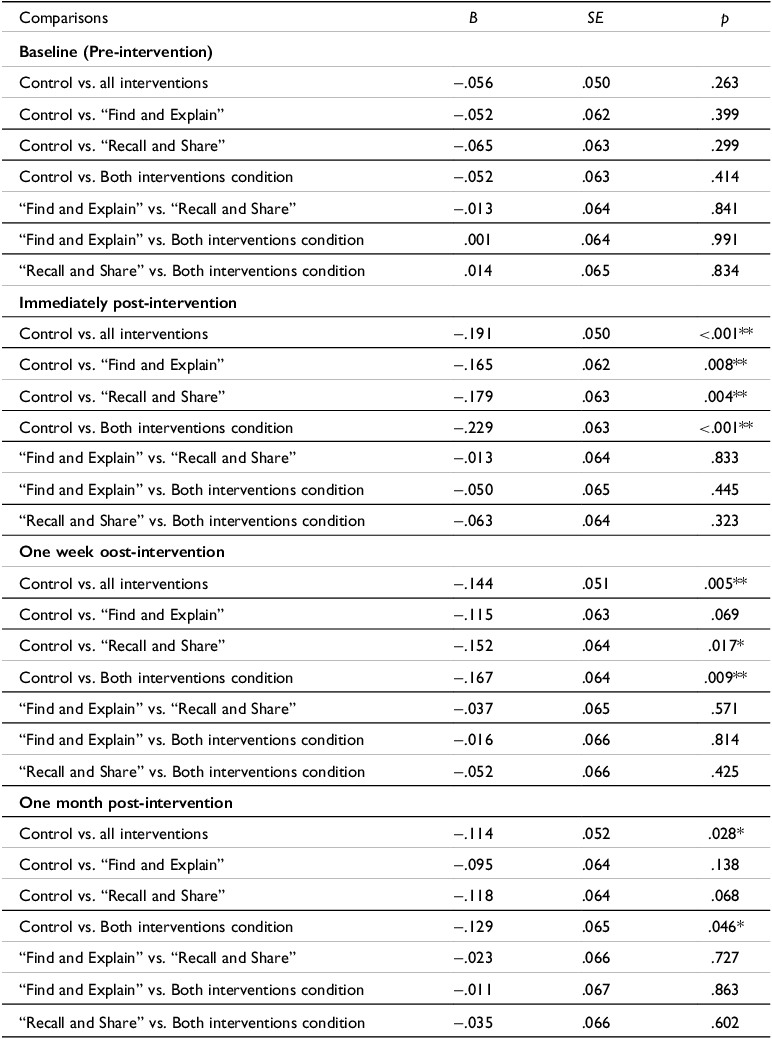

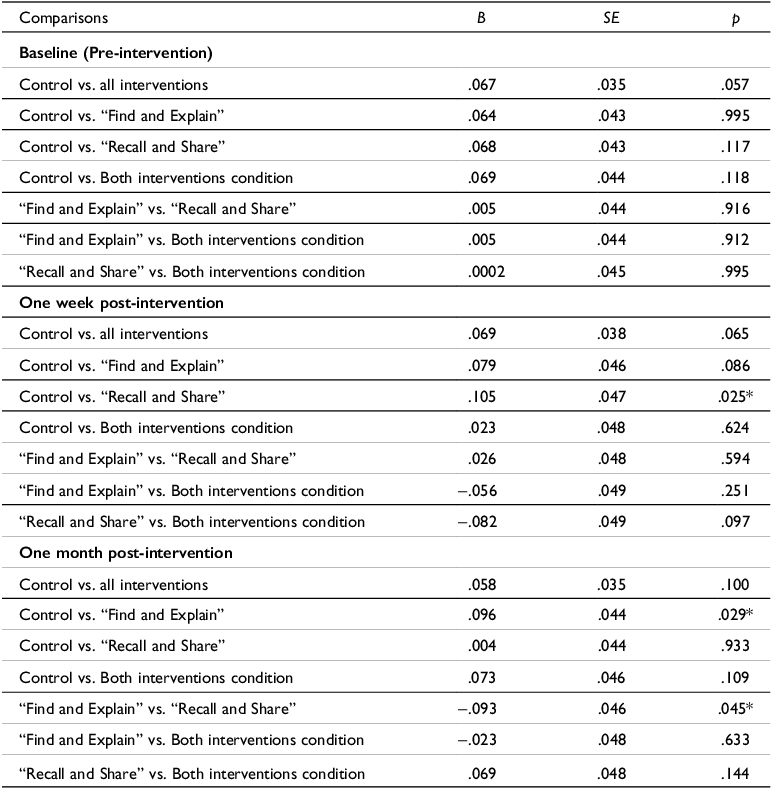

Means for all variables by condition and time of assessment are portrayed in Table 2. We conducted a mixed effects linear model testing for mean differences over time (pre-test, post-test, one-week, and one-month follow-ups) by study condition (4-category variable distinguishing assigned condition) on financial confidence. There was an effect of condition (F (3,1115) = 2.61, p = .050), an effect of time (F (3,3072) = 90.2, p < .0001) and a significant interaction (F (9,3072) = 2.24, p = .017). Table 3 portrays contrast estimates comparing financial confidence between the four conditions at each point of assessment.

Table 2. Average financial confidence and positive financial behaviors across conditions and times of assessment

Note. M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation. Financial confidence and positive financial behaviors were assessed on 5-point scales. Means or percentages with a different subscript within the same row are statistically significantly different from each other at p < .05 in a contrast test of those conditions in one-way ANOVAs. Data collected in Canada in 2023 (Peetz & Howard Reference Peetz and Howard2024).

Table 3. Pairwise comparisons of financial confidence between conditions at each time of assessment

Note. B = Unstandardized regression coefficient, SE = Standard Error, p = p-value. * p < .05, **p < .01 Data collected in Canada in 2023 (Peetz & Howard Reference Peetz and Howard2024).

First, we confirmed that participants randomly assigned to one of our intervention conditions or to the control condition were not different in their financial confidence prior to the intervention (largest B = −.07, SE = .06, p = .30). At our immediate post-intervention assessment, financial confidence ratings from participants assigned to any of the three intervention conditions were about 6.5% higher than ratings from young women in the control condition (largest B = −.23, SE = .06, p < .001). There was no difference between the recall and share intervention condition and the find and explain intervention condition (B = .01, SE = .06, p = .21), and the condition with both interventions did not differ from the recall and share intervention (B = −.05, SE = .06, p = .44) or the find and explain condition (B = −.06, SE = .06, p = .33). The increased financial confidence effect persisted to the one-week follow-up with a 4.7% difference between control and intervention conditions (largest B = −.17, SE = .06, p = .009), but at the one-month follow-up, two out of three differences were no longer statistically significant, and the size of the effect had dropped further (largest B = −.13, SE = .06, p = .046). After adjusting our analysis for potentially confounding effects of family income, age, and socioeconomic status, effects described above were unchanged.

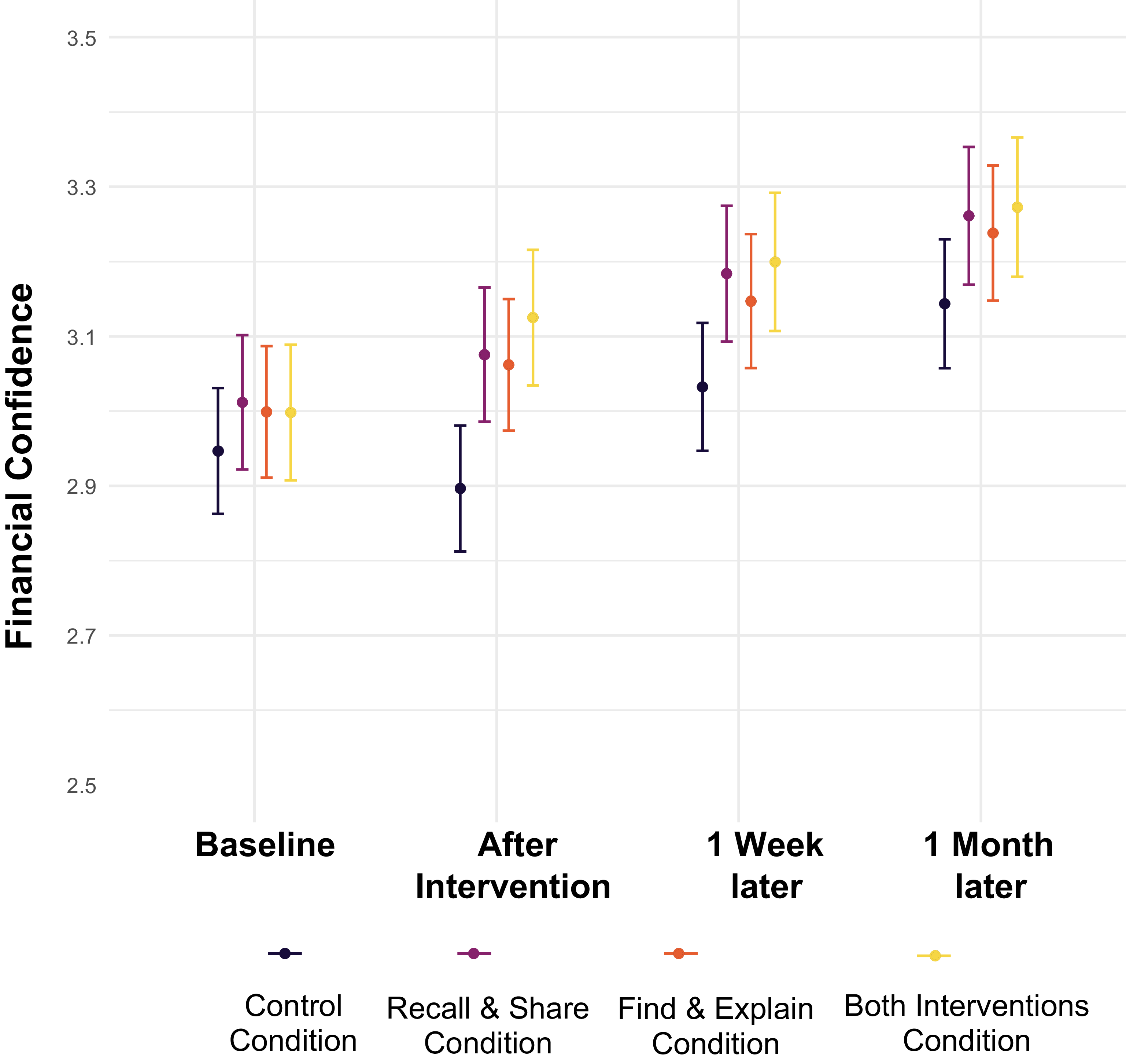

As shown in Figure 1, participants in all conditions reported higher financial confidence at later vs. earlier study weeks. For example, participants in the condition exposed to both interventions reported a 9% improvement in financial confidence between pre-intervention and the one-month follow-up. However, participants in the control condition also reported an improvement over the same period – of almost 7% – despite receiving no intervention.

Figure 1. Financial confidence ratings across conditions and follow-up assessments in an experiment conducted with Canadian young women in 2023 (Peetz & Howard Reference Peetz and Howard2024).

Note: Positive Financial Behaviors measured on a 5-point scale (Peetz & Howard Reference Peetz and Howard2024).Line ranges show 95% confidence intervals around each estimate.

3.3. Intervention effect on positive financial behaviors

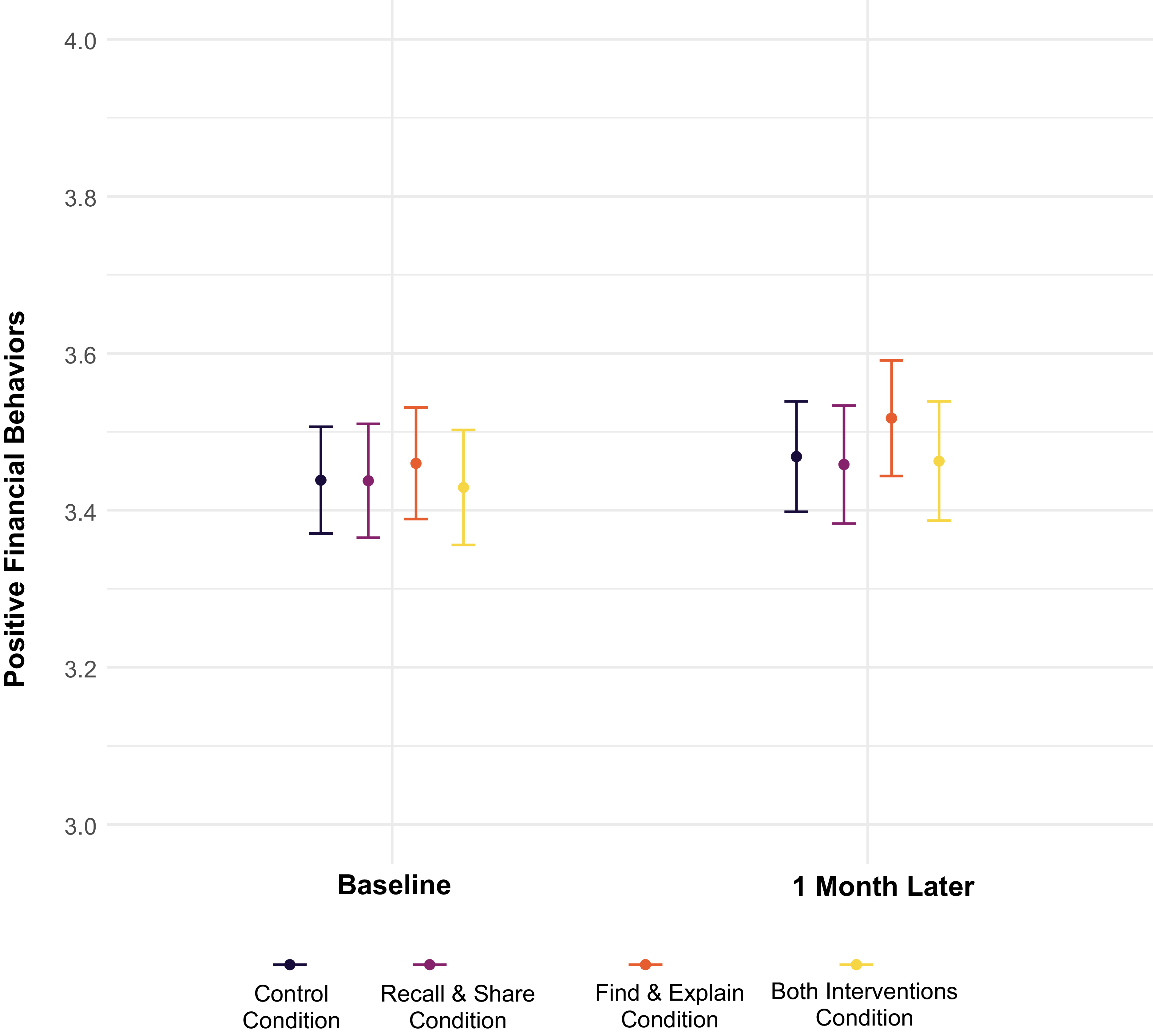

To examine financial behaviors, we first focused on the responses to the positive financial behaviors scale (Dew & Xiao Reference Dew and Xiao2011). A mixed effects linear model testing for mean differences over time (pre-intervention and one-month follow-up) by study condition detected no differences between conditions on young women’s self-reported financial management behaviors (F (3,1113) = 0.30, p = .83), and no significant interaction (F (3,971) = 0.37, p = .77), but detected an effect of time (F (1,971) = 7.63, p = .006). Specifically, participants reported very slightly better financial management at the one-month follow-up (M = 3.48, SD = 0.59) compared to the pre-intervention (M = 3.44, SD = 0.61) across conditions. Figure 2 portrays means by condition.

Figure 2. Positive financial behaviors across conditions at pre-test and one month post-intervention in an experiment conducted with Canadian young women in 2023 (Peetz & Howard Reference Peetz and Howard2024).

Note: Line ranges show 95% confidence intervals around each estimate. Positive financial behaviors measured on a 5-point scale (Dew & Xiao Reference Dew and Xiao2011).

Second, we examined the percentage of participants who reported contributing to savings in the past week pre-intervention vs at the one-week follow-up. A Chi-square test comparing percentages across times of assessment showed again a significant effect of time (X 2 [N = 997, df=2] = 140.9, p < .001): Pre-intervention, 41% of participants reported having contributed to their savings in the last week, at the one-week follow-up, 49% of participants across conditions reported having contributed to their savings in the last week, rising to 68% at the one-month follow-up. There was no significant difference by condition pre-intervention (X 2 [N = 997, df=3] = 3.70, p = .296), at the one-week survey (X 2 [N = 875, df=3] = 6.32, p = .097), or at the one-month survey follow-up (X 2 [N = 824, df=3] = 6.93, p = .074). In all analyses, presence of covariates (family income, age, and socioeconomic status) did not impact results. Table 4 portrays contrast estimates comparing percentage of participants who reported saving between the four conditions at each point of assessment.

Table 4. Pairwise comparisons of proportions of participants who contributed to savings in the past week between conditions at each time of assessment

Note: B = Unstandardized regression coefficient, SE = Standard Error, p = p-value. * p < .05 Data collected in Canada in 2023 (Peetz & Howard Reference Peetz and Howard2024).

4. Discussion

Being confident in one’s ability to manage day-to-day financial tasks can predict positive financial behaviors such as contributing to saving (Angrisani & Casanova Reference Angrisani and Casanova2021; Palameta et al. Reference Palameta, Nguyen, Hui and Gyarmati2016; Robb & Woodyard Reference Robb and Woodyard2011) and lower anxiety and stress about finances (Jawahar et al. Reference Jawahar, Mohammed and Schreurs2022). Women tend to feel less confident in their capability and financial knowledge than men, even regardless of actual knowledge (Angrisani & Casanova Reference Angrisani and Casanova2021; Chen & Volpe Reference Chen and Volpe2002; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Maillet and Koffi2022; Palameta et al. Reference Palameta, Nguyen, Hui and Gyarmati2016). The present study tested two avenues toward increasing financial confidence in a sample of young women. Building on previous research (Grillo et al. Reference Grillo, Ward, Atlas, Porto, Xiao, Dunn, Fernbach, Jhang, Lynch, Sussman, Egan, Swift and Farming2018; Jha & Shayo Reference Jha and Shayo2022), the present study found that a brief task intended to increase financial knowledge through defining financial terms increased financial confidence relative to a control group directly after the intervention and up to one week later. In addition, another novel intervention aimed at inducing positive social beliefs (recalling a positive financial experience and browsing other young women’s stories of positive financial experiences) also increased financial confidence relative to a control group directly after the intervention and up to one week later. The latter avenue of increasing financial confidence has not been studied to date, but results suggest that a social beliefs approach may be just as effective in increasing financial confidence as educational approaches. This suggests a novel avenue for fostering financial confidence among those who tend to be financially underconfident.

4.1. Theoretical contributions

While there are a number of interventions aimed at increasing actual financial knowledge, especially among women (e.g., Kaiser et al. Reference Kaiser, Lusardi, Menkhoff and Urban2022), the present research contributes to the emerging and much smaller set of studies focusing on confidence about financial decisions (Grillo et al. Reference Grillo, Ward, Atlas, Porto, Xiao, Dunn, Fernbach, Jhang, Lynch, Sussman, Egan, Swift and Farming2018; Jha & Shayo Reference Jha and Shayo2022). A second novel contribution of this research was the inclusion of more objective financial behaviors (e.g., savings contributions, financial management behaviors) in addition to the subjective financial attitudes, such as financial confidence.

A consistent finding in the present study was an overall improvement in financial confidence and more positive financial behaviors across all participants over time. This suggests that simply participating in a study that prompted women to think about and report on their financial habits and beliefs provided benefits to participants. Given their underconfidence, it is likely that young women do not talk about financial decisions and beliefs frequently in their daily life, and this can be exacerbated by a social norm related to seeing money talk as taboo (e.g., Alsemgeest Reference Alsemgeest2016). A reluctance to talk about money may, in turn, discourage women from seeking the financial help and advice they need to boost their financial knowledge and confidence – i.e., perpetuating a cycle of negative outcomes for women.

4.2. Limitations

We recruited a relatively specific sample of women between the ages of 16 and 25 years old. The rationale for this sample selection was that it is abundantly clear from the existing literature that women are the most underconfident subset of the population (Angrisani & Casanova Reference Angrisani and Casanova2021; Bucher-Koenen et al. Reference Bucher-Koenen, Lusardi, Alessie and Rooijvan2017; Chen & Volpe Reference Chen and Volpe2002; Driva et al. Reference Driva, Lührmann and Winter2016; Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, Fry and Risse2016; Jha & Shayo 2022; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Maillet and Koffi2022; Palameta et al. Reference Palameta, Nguyen, Hui and Gyarmati2016; Preston & Wright Reference Preston and Wright2019) and thus most in need of receiving a boost in confidence. However, the lack of a male participant control group is a limitation of the present study, as the present study cannot speak to whether the benefits of the interventions would extend to young men to the same or a different extent. Notably, financial literacy interventions sometimes run the risk of widening rather than closing gaps in pre-existing differences. For example, a financial education program in German high schools showed that the program increased financial literacy levels overall but did not reduce the pre-existing gender gap in self-assessed knowledge of financial matters (Lührmann et al. Reference Lührmann, Serra-Garcia and Winter2015). An American financial education program showed that the education widened rather than closed the gap between people starting from a lower knowledge point (Al-Bahrani et al. Reference Al-Bahrani, Weathers and Patel.2019). Thus, it is possible that the interventions might increase financial confidence for everyone regardless of gender, thus maintaining the gender gap.

The present study focused on a specific geographic region, namely women living in Canada. There are many cultural differences in how money is seen across cultures and countries (e.g., Shoham & Malul Reference Shoham and Malul2012; Stulz & Williamson Reference Stulz and Williamson2003) (though the gender gap in confidence presents universally (Bucher-Koenen et al. Reference Bucher-Koenen, Lusardi, Alessie and Rooijvan2017)). Thus, conclusions of this study are limited to cultures similar to the Canadian mindset about finances and money.

This study was limited in the time frame studied and the number of times participants were contacted. We followed up with participants directly after the intervention tasks, one week, and one month later. More frequent follow-ups might result in bolstered benefits for financial confidence and associated financial behaviors. Alternatively, there might be a limit to how much exposure to financial questions benefits a person and time effects might level off at some point. Future research could extend the time frame or vary the number of points of contact to examine the longevity of financial confidence boosts.

An important limitation of this study is the integration of researcher demand into the “recall and share” intervention. This intervention was based on the idea that exposing women to the idea that other women feel confident increases their self-report of confidence, utilizing the clearly stated expectation that they can and do feel confident as part of the instruction. This integration of researcher demand characteristics into a manipulation is reflected in the plethora of priming research that has shown meaningful (though short-lived) responses to pre-activation of concepts (e.g., Cohn & Maréchal Reference Cohn and Maréchal2016) or research on “self-talk” that suggests self-labeling can affect subsequent performance (e.g., Tod et al. Reference Tod, Hardy and Oliver2011). Note that only two of the five items of the financial confidence scale included the term “confident” to separate the scale from the instructions, and the persistence of the intervention effect beyond the immediate time to the following week suggests that confidence differences between groups cannot be entirely attributed to demand in the moment. However, more research is needed to disentangle participant compliance from meaningful change in financial confidence. One possibility might be to assess financial confidence indirectly rather than through self-report, for example, by noting participants’ choice to take on tasks that are costly but reward financial confidence.Footnote 3

5. Conclusions

This research suggests that simply talking more about financial decisions, opinions, and situations might increase financial confidence. In many Western societies, including Canada, the topic of money is socially taboo (Alsemgeest Reference Alsemgeest2016). People’s sense of how much they know about finances and how well they manage their money can be further biased by insecurities and stereotypes about the social groups they belong to, such as their gender. The present research shows three avenues toward fostering financial confidence in a group that has been shown to be underconfident (women): by a brief learning task, by sharing experiences of financial confidence, and by simply reporting on financial topics over time.

As the effectiveness of the social beliefs-inspired intervention showed, the role models and descriptive norms about similar others matter to financial confidence. Cultural portrayals of women as poor financial decision makers, such as the trend to portray irrational spending decisions as “girl math,” may be damaging to women’s confidence or even induce stereotype threat (Carr & Steele Reference Carr and Steele2010; Tomasetto et al. Reference Tomasetto, Alparone and Cadinu2011). Portraying women who are positive role models in the financial domain may help counter these negative stereotypes.

Discourse about finances should be fostered in people’s daily lives to boost financial confidence, especially for those who might have a lower sense of confidence, such as women. There are few social spaces, perhaps especially for women, where money talk is encouraged and socially valued. Creating more such safe spaces might reduce the gender gap in financial confidence. Through reducing the gender gap in confidence, women may be better set up for success to engage in positive financial behaviors and achieve financial wellbeing to the same extent as their male counterparts.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/flw.2026.10008

Data Availability Statement

Data and survey materials are available on OSF: https://osf.io/3pq69/

Acknowledgements

This work was developed, in whole or in part, from data of the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada. We thank Abby Bradley, Erika Doucette, and Zoe Meloff for their research assistance.

Competing interests

None of the authors has a conflict of interest to declare. Samantha Hollingshead and Monica Soliman are employees of the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada (FCAC). Any findings, views, or opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the FCAC or the Government of Canada.