Introduction

Political parties and voters form important relationships in a democracy because parties connect voters’ preferences with public policy. Voters’ attitudes towards political parties legitimize them as the main agents of representation and can spur engagement in party politics (Hooghe & Marien, Reference Hooghe and Marien2013; Ignazi, Reference Ignazi2017). However, voters across modern democracies have highly ambivalent attitudes towards parties. Based on much empirical evidence, scholars conclude that voters might well consider parties ‘necessary for the good functioning of politics and the state’, but they neither like nor trust them (e.g., Mair, Reference Mair2013, p. 73; see also Dalton, Reference Dalton2013; Dommett, Reference Dommett2020; Hay, Reference Hay2007; Linz, Reference Linz, Gunther, Montero and Linz2002; Rosenbluth & Shapiro, Reference Rosenbluth and Shapiro2018; van Biezen, Reference Van Biezen2008; Webb, Reference Webb2005; for a similar but philosophical view, see Bonotti, Reference Bonotti2017; Rosenblum, Reference Rosenblum2010; White &, Ypi, Reference White and Ypi2010).

Most existing theories to explain voters’ ambivalent attitudes towards parties are heavily grounded in the party politics literature. They propose that the erosion of party–voter linkages and the simultaneous tightening of party–state relationships can account for voters’ ambivalent attitudes (e.g., Katz & Mair, Reference Katz and Mair1995, Reference Katz and Mair2009, Reference Katz and Mair2018; Webb, Reference Webb2005). However, these existing explanations only pay little, if any, attention to research in public opinion on how voters form attitudes towards political actors, even though this is a central aspect of the paradox and plausibly key to political participation (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2020). In this paper, we therefore propose a different argument that takes public opinion research explicitly into account.

Specifically, we develop a new analytical model that integrates contemporary party politics and public opinion research in novel ways and that draws on qualitative methods to formulate and validate data-based theoretical concepts (see Deterding & Waters, Reference Deterding and Waters2021). Our point of departure is public opinion research showing that voters’ expectations are important for their attitudes (see, e.g., De Vries, Reference De Vries2017; Jacobs & Matthews, Reference Jacobs and Matthews2012; Leshem & Halperin, Reference Lefkofridi and Nezi2023; Noelle-Neumann, Reference Noelle‐Neumann1974; Oliver, Reference Oliver1980, Reference Oliver1997). We subsequently integrate existing literature on voters’ expectations in party politics and on public opinion to sketch the contours of a different argument. While the party politics literature highlights the role of voters’ expectations towards the functional output parties deliver in representative democracies or what democratic outputs parties deliver, the public opinion literature points at voters’ preferences for non-policy related characteristics of parties, such as debating civility or competence or how parties deliver their democratic outputs. The literature thus provides hints that voters hold multi-dimensional expectations of parties, which may account for voters’ ambivalent attitudes towards parties.

In order to refine this suspicion and develop a coherent and operational analytical model, we use empirical insights from different kinds of qualitative material (open-ended survey answers and focus group data) in Denmark. Deductive and inductive analyses of the empirical material inform our model on voters’ attitudes towards political parties in three important ways. First, we identify two dimensions of expectations: Voters expect parties to deliver functional and – what we term – virtuous democratic linkage, that is, agents of good democratic practice. Second, we specify the content of the virtuous linkage, showing that voters expect parties to be reliable agents who keep their promises, respect the law and are policy-motivated, competent agents that know about and handle societal problems on behalf of the nation; and educational agents that enact and explain democratic principles. Third, we reveal that spontaneous expressions of dissatisfaction mainly occur in connection to parties’ virtuous linkages, not their functional linkages. These cumulative results lead us to propose a new model of party–voter linkage including two dimensions of voter expectations towards political parties, which offers a coherent explanation of why voters find political parties necessary but untrustworthy.

The virtuous party linkage model has important implications for any research interested in party–voter relationships in democracies. By combining and extending diverse literature in a new way, it synthesizes the notions that voters hold expectations and form perceptions based on parties’ democratic functions as well as on their democratic virtues. Such an extension of party linkage theory acknowledges and emphasizes parties’ dual role as democratic institutions transmitting democratic goods and as political actors qualified by motives and conduct. Proposing a new model, we also contribute to the literature methodologically. We illustrate the development of data-based theories that specify testable concepts and relationships because they stay close to the empirical phenomenon.

Expectations as an analytical key for explaining voters’ attitudes towards political parties

Voters’ attitudes towards political parties paint an ambivalent picture (Aldrich, Reference Aldrich2009; Linz, Reference Linz, Gunther, Montero and Linz2002; Webb, Reference Webb2005). On the one hand, surveys from across the democratic world repeatedly document low levels of trust in parties (for the latest overview, see Norris, Reference Norris2022). On the other hand, other survey-based work also demonstrates how much voters value the basic idea of political parties. For example, data from the Comparative Survey of Electoral Systems shows that ‘three-quarters of the public in these 13 democracies‘ (Dalton & Weldon, Reference Dalton and Weldon2005, p. 933) think parties are necessary for democracy (for similar results from Latin America only, see also Moisés & Carneiro, Reference Moisés and Carneiro2016). This illustrates that voters seemingly grasp the value of political parties but are highly critical of them, nonetheless.Footnote 1

We propose that voters’ expectations of parties are key to understanding their attitudes and thus also the current ambivalence. Much public opinion research demonstrates that voters’ political attitudes correlate with their expectations, defined as a strong belief that some quality should be delivered (see, e.g., De Vries, Reference De Vries2017; Jacobs & Matthews, Reference Jacobs and Matthews2012; Leshem & Halperin, Reference Lefkofridi and Nezi2023; Noelle-Neumann, Reference Noelle‐Neumann1974; Oliver, Reference Oliver1980, Reference Oliver1997). Causality could flow in both directions. A sociological perspective on public opinion formation would stress that expectations are exogenous. Parents or the school environment may shape individuals’ expectations, which in turn affect attitudes (e.g., Oliver, Reference Oliver1980, Reference Oliver1997). However, expectations could also be endogenous through a possible process of post hoc rationalization. Irrespective of which perspective one adopts, at a given point in time expectations correlate with attitudes and they will consequently matter.

Applied to parties, it means that positive attitudes towards parties may be partly a function of a match between parties’ behaviour and prior expectations, and negative attitudes might occur when expectations and behaviour are unaligned (Seyd, Reference Seyd2015). According to this rationale, the ambivalence in voters’ attitudes towards parties could be the result of parties not delivering on (parts of) the expectations citizens have. Understanding voters’ expectations towards parties is therefore crucial for understanding their ambivalent attitudes.

Expectations about offering functional linkages

The literature on political representation is rich in concepts and theories, but it generally remains agnostic towards political parties or voters’ expectations of them (see, e.g., Dovi, Reference Dovi2006; Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge2003, Reference Mansbridge2009; Rehfeld, Reference Rehfeld2006, Reference Rehfeld2009; but see Wolkenstein & Wratil, Reference Wolkenstein and Wratil2021). By implication, it provides little theory to account for voters’ attitudes towards parties. The party politics literature, in contrast, provides a concrete explanation accounting for voters’ attitudes towards them.

A large body of this literature suggests that voters’ attitudes towards political parties are grounded in disappointed expectations about how parties perform their functional linkages. According to this view, voters’ negative attitudes might be attributed to the erosion of party–voter relationships and the simultaneous strengthening of party–state ties through, for example, increasing state party funding (e.g., Katz & Mair, Reference Katz and Mair1995, Reference Katz and Mair2009, Reference Katz and Mair2018; Poguntke & Scarrow, Reference Poguntke and Scarrow1996; Webb, Reference Webb2005). The underlying cartel party thesis by Katz and Mair holds that mainstream parties have formed a cartel because they have a shared interest in protecting their political standing in today's democracies. In trying to guard their political capital against newcomers, mainstream parties strengthen their ties to the state while at the same time neglecting their relationship with voters, leaving it ‘with no essential function’ (Katz & Mair, Reference Katz and Mair2018, p. 61). Also work beyond the cartel party thesis supports the view that parties’ ties to voters have weakened during the last decades (De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020; Nanou & Dorussen, Reference Nanou and Dorussen2013; Ward et al., Reference Ward, Kim, Graham and Tavits2015). Following this line of reasoning, parties have strengthened their functional linkages to the state and have abandoned those to citizens with distinct implications for public opinion of parties. It is this dual development that is at the heart of the prevailing logic of voters’ attitudes towards parties (Ignazi, Reference Ignazi2017; see also Poguntke, Reference Poguntke1996; Webb, Reference Webb2005).

This logic is strongly based on party linkage theory. Belonging to structural-functionalist accounts of political parties, the theory specifies distinct functions, tasks or roles for parties (e.g., Aldrich, Reference Aldrich1995; Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Farrell and McAllister2011; Key, Reference Key1964; Sartori, Reference Sartori1976). It conceptualizes parties as multi-dimensional institutions in which the different parts or faces jointly work towards connecting voters with policy output. In one influential application, Dalton et al. (Reference Dalton, Farrell and McAllister2011, p. 6f) specified five party linkages that jointly form a chain between voters and policy: campaign linkage, by which parties recruit candidates and organize elections; participation linkage, by which parties activate voters to engage in elections; ideological linkage, by which parties offer alternative policy choices; representative linkage, by which parties represent voters’ policy preferences in parliament and government; and policy linkage, by which parties deliver policies advocated for in the election.Footnote 2 Applied to explain voters’ attitudes, this conceptualization suggests that negative attitudes towards parties are partly fuelled by their disappointed expectations on the functional linkages that parties should provide. In other words, the prevailing logic is one of functional linkage failures.

However, it is striking that this prevailing logic to explain voters’ ambivalent attitudes towards parties is entirely grounded in party politics literature. Research based on public opinion theories that can explain the formation and development of voters’ political attitudes and evaluations of political actors features little in this literature. In fact, none of this work uses survey measures to gauge voters’ evaluations of party performances.Footnote 3 Still, the implied assumption is that voters’ attitudes towards parties can be entirely explained by what parties do (or rather do not do). Such a view can possibly be squared with top-down theories of public opinion formation, but certainly not with bottom-up theories (see, e.g., Achen & Bartels, Reference Achen and Bartels2017; Kertzer & Zeitzoff, Reference Kertzer and Zeitzoff2017; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). Additionally, some empirical evidence on the representative performance of political parties also challenges the prevailing logic because it demonstrates that parties are regularly delivering the democratic outcomes assumed by party linkage theory (see Adams, Reference Adams2012; Blais et al., Reference Blais, Guntermann, Arel‐Bundock, Dassonneville, Laslier and Péloquin‐Skulski2022; Dalton, Reference Dalton2021; Pedrazzani & Segatti, Reference Pedrazzani and Segatti2022; Rohrschneider & Whitefield, Reference Rohrschneider and Whitefield2012; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017) even though national parties face international and institutional constraints responding to voter demands (Alonso & Ruiz-Rufino, Reference Alonso and Ruiz‐Rufino2020; Lefkofridi & Nezi, Reference Lefkofridi and Nezi2020). We, therefore, propose a new argument that is sensitive to and systematically integrates public opinion research to explain voters’ complex attitudes towards parties.

Towards a virtuous party linkage model

In this section, we propose and sketch the contours of a new party–voter linkage model, which considers citizens’ expectations. To do so, we draw on a substantial but much less cohesive literature on the public opinion of parties. While this literature tends to neglect the multiple functions of political parties and most often focuses on voters’ party choice, several strands indicate that voters’ evaluations of parties go beyond the delivery of programmes and policies. They thus suggest that voters’ expectations might do so too.

For example, according to individual-level valence theory (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley2004; Stokes, Reference Stokes1963), voters evaluate political parties not only on the positions they take on political issues but also on ‘nonideological actions’ (Butler & Powell, Reference Butler and Powell2014, p. 492). Valence issues can be policy issues, such as the economy (e.g., Lewis-Beck & Paldam, Reference Lewis‐Beck and Paldam2000; Lewis-Beck & Stegmaier, Reference Lewis‐Beck and Stegmaier2000), but they can also be character- or trait-based factors, such as honesty, competence or authenticity (e.g., Green & Jennings, Reference Green, Jennings, Arzheimer, Lewis‐Beck and Evans2017; Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Larner and Lewis‐Beck2021; Stiers et al., Reference Stiers, Larner, Kenny, Breitenstein, Vallee‐Dubois and Lewis‐Beck2021). Valence theory thus holds that voters expect parties to not only provide issue positions that match their preferences but also desirable conduct profiles.

Another research area also indicates the relevance of non-policy-based expectations for how voters evaluate parties, namely political norms. Much of this work shows that negative or uncivil behaviour by parties or politicians often has negative effects on voters’ evaluations of and attitudes towards parties or candidates (e.g., Brooks & Geer, Reference Brooks and Geer2007; Frimer & Skitka, Reference Frimer and Skitka2018; Skytte, Reference Skytte2021; Van't Riet & Van Stekelenburg, Reference Van't Riet and Van Stekelenburg2022). Relatedly, research on party legitimacy perception shows that voters’ evaluations of parties as respecting the rules of democracy or abiding by the prevailing social norms are systematically related to party support (see Bos & van der Brug, Reference Bos and Van der Brug2010; Jacobs & van Spanje, Reference Jacobs and van Spanje2021; Kölln, Reference Kölln2024; van Spanje & Azrout, Reference Van Spanje and Azrout2021), though other studies show that voters care more about policy outcomes than democratic norms (Krishnarajan, Reference Krishnarajan2023; Frederiksen, Reference Frederiksen2024; Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020).

Yet other signs of the importance of non-policy-based evaluations can be found in the growing research on anti-elitist and populist attitudes. According to this literature, (political) elites are seen as ‘corrupt, betraying, and deceiving’ (Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Müller, Schemer, Wirz, Wettstein and Wirth2018, p. 317; see also Mudde, Reference Mudde2004), thus exposing motivations of self-interest rather than motivations to propose or enact good policies. Recent analyses also demonstrate that such attitudes are systematically connected to trust in political institutions, including parties (Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020).

These are but three examples from the literature. They indicate, alongside similar research, that voters expect a certain kind of behaviour from parties and evaluate them accordingly. Research related to these themes commonly portrays parties as political actors, as opposed to institutions or organizations, with certain motives or character traits that may be more or less desirable in voters’ eyes.

Dommett's (Reference Dommett2020) study from Britain comes closest to making this point concretely. Through a combination of deliberative workshops and large-scale surveys, she explores ‘people's desires for parties and how current practices live up to these ideals’ (Dommett, Reference Dommett2020, p. 3). Her analyses demonstrate that voters’ ‘ideal political party’ is one that is ‘transparent, communicative, reliable, principled, inclusive, accessible and that act[s] with integrity’ (Dommett, Reference Dommett2020, pp. 151, 169). Although formulated as a wish list for a perfect political party that may never exist in reality, Dommett's findings are instructive. They echo the individual studies above and suggest that voters’ expectations of parties as political actors revolve around the display of what could be termed as democratic virtues.

Such expectations are not only clearly separate from deliveries on functional linkages but also suggest an alternative logic of voters’ attitudes towards parties. This logic, we propose, can be tentatively summarized as based on virtuous linkage failures in which voters’ negative attitudes towards parties are fuelled by their disappointed expectations on the democratic virtues that parties should provide.

More concretely, we suggest that expectations of functional and virtuous linkages belong to a larger framework conceptualizing party–voter relationships, which we refer to as the virtuous party linkage model. We propose that to account for the full range of voters’ expectations and attitudes towards political parties more generally, we need to combine the well-known functional linkages, related to parties’ delivery of candidates, programmes and policy, and the newly suggested linkages related to parties’ displays of demanded virtues. Both are interlinked and concern the democratic relationship between voters and political parties, with the important difference that one focuses on functional performance and the other on virtuous performance. The functional linkages generate expectations among voters for parties to deliver on linking citizen preferences and public policy. In this sense, voters, just like political scientists, may think of functional linkages as normatively important roles parties should take on to make party democracy work. Through the virtuous linkages, on the other hand, voters develop expectations for parties to link democratic virtues to party governance. These expectations relate more to societal norms of conduct and can assist in understanding voters’ attitudes towards parties, even when they are performing their functions well. Despite the linkages’ distinct roles or purposes, they could at times also be related because one may be describing how the other should come about.

Refining the virtuous party linkage model: Methodology and research material

So far, our theory is based on the integration of existing literature but remains suggestive and vague. This is typically where theory development stops. Our ambition is different, and we thus respond to recent calls for methodological innovation in theory building (see Deterding & Waters, Reference Deterding and Waters2021). To provide detail and nuance to our model and to develop a model that stays close to the empirical phenomenon, we step out of the literature and into data analysis. Based on an exploratory methodology applied to new empirical material, we can further develop, specify and nuance the theoretical idea sketched above to arrive at a data-based model that stays close to the phenomenon it seeks to explain.

One central challenge to this is that expectations are inherently difficult to study. They can be differently interpreted, namely as either descriptive expectations (something will happen) or as normative expectations (something should happen) (e.g., James, Reference James2011; Seyd, Reference Seyd2015). While it is in principle easy to distinguish between them, recent work shows that single expressions of expectations may be more ambiguous (Hjortskov, Reference Hjortskov2020).

Our solution to this problem is to collect data through focus group discussions and open-ended survey questions. Their individual and combined characteristics are ideal for our research purpose. When analysed highly inductively, open-ended survey answers and focus group discussions serve theory-building particularly well because they give us the opportunity to learn about views and perspectives we did not anticipate (Brancati, Reference Brancati2018; Cyr, Reference Cyr2016; Morgan, Reference Morgan1996), once in isolation (survey) and once with context and elaborations (focus group). The two data collection methods also complement each other by compensating for one another's individual flaws. Focus group data are richer and more precise, allowing us to explore how terms were interpreted because they are used in a conversational context; survey data cover more voters, allowing us to probe a larger set of views. Focus groups allow us to interrogate the different logics of voters’ attitudes towards parties because they provide information on how voters reason, which surveys do not. In contrast, online survey questions reduce social desirability bias compared to focus group discussions. Dominant voices, group social desirability biases or the potential influence of the moderator are known risks for focus groups (Morgan, Reference Morgan1996; Smithson, Reference Smithson2000). For these reasons, the pair is ideal for our purposes. Moreover, their differences, not least in terms of resource intensity, also make for a valuable exploratory comparison of their relative merits for developing data-based theory.

Context and data collection

We attended to the internal and external generalizability of our study by selecting our case and participants according to theoretically relevant parameters (Maxwell & Chmiel, Reference Maxwell, Chmiel and Flick2014). Our goal was to obtain a comprehensive picture of voters’ expectations of parties to offer as much detail and nuance as possible in our model. The best way to accomplish that is by selecting an ‘extreme case’ (Gerring, Reference Gerring2006, p. 101). The extreme-case method follows the idea that ‘concepts are often defined by their extremes’ and that this will ‘maximize variance on the dimension of interest’ (Gerring, Reference Gerring2006, pp. 101, 104). The extreme-case method is thus by no means representative, but that is not its purpose anyhow. According to Gerring (Reference Gerring2006, p. 105), it is ‘purely exploratory – a way of probing […] possible effects of X 1, in an open-ended fashion’. By using the extreme-case method, we thus increase our chances of painting the most comprehensive picture of voters’ expectations of parties and why they may occur.

Denmark may be considered an extreme case when it comes to party–voter relationships because it has relatively well-performing parties according to the party linkage theory: Parties can communicate their positions to voters (Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Farrell and McAllister2011, p. 112), provide a comparatively wide range of positions for voters to choose from (Jensen & Vestergaard, Reference Jensen and Vestergaard2022); party governments are comparatively responsive to public opinion (Hobolt & Klemmensen, Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2005) and, recently, comparatively less constrained by substantial EU regulation doing so (Alonso & Ruiz-Rufino, Reference Alonso and Ruiz‐Rufino2020). Moreover, Denmark is the world's least corrupt country (Transparency International, 2021), and Danish voters generally exhibit high levels of trust in political institutions compared to other European countries.Footnote 4 These features make Denmark an extreme case and thus ideal for our purpose of identifying voters’ expectations of parties as possible explanations for their attitudes.

The survey data were collected online in the summer of 2020 with the help of YouGov. A total of 107 respondents, representing broadly different groups of the Danish adult population, answered the open-ended survey question ‘What do you generally expect political parties to do in a democracy?’ The question appeared at the beginning of a small survey aiming to explore voters’ views of parties. The focus groups took place in Fall 2021 in the run-up to local elections (16 November 2021).Footnote 5 The pre-election period helped us aim at a comprehensive understanding of expectations as research shows that election campaigns increase voters’ political awareness, political knowledge and internal and external efficacy (Claassen, Reference Claassen2011; Hansen & Pedersen, Reference Hansen and Pedersen2014). With these features, our context and data collection provide good opportunities to explore nuanced voter expectations of political parties, crucial for developing a comprehensive model for understanding multiple ways in which voters evaluate and form perceptions of political parties.

Focus group composition

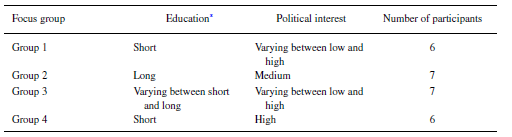

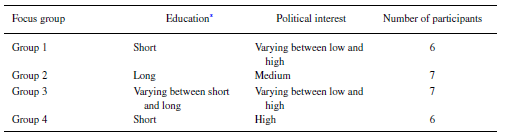

We conducted four focus group discussionsFootnote 6 with a total of 26 participants, recruited by the research company Norstat. In selecting our participants, we aimed at obtaining diversity in views and focused on two background factors (Stewart & Shamdasani, Reference Stewart and Shamdasani2015): education and political interest. Formal education is shown to relate to peoples’ perceptions of politics, including the standards they use to evaluate political actors and behaviour (Nie et al., Reference Nie, Junn and Stehlik‐Barry1996; Stubager et al., Reference Stubager, Seeberg and So2018). Similarly, research shows that political interest is associated with political participation and political trust (e.g., Catterberg & Moreno, Reference Catterberg and Moreno2006; Denny & Doyle, Reference Denny and Doyle2008). Variations in political interest and education may therefore also relate to different expectations towards political parties and possibly influence the dynamic of discussing political parties. Table 1 shows the composition of our four groups (more details in the online online Appendix A). All groups were heterogeneous as to gender, age and ideological leaning, with the aim of securing different political, generational and gender-based views in the group.

Table 1. Composition of focus groups

* Note: “Short” denotes primary, secondary or 1–2 years of post-secondary education. ‘Long’ denotes three or more years of post-secondary education.

Conducting the focus group discussions

The focus groups took place in a meeting room (picture in online Appendix A) on a university campus close to the city centre of a large Danish city.Footnote 7 The focus group discussions were guided by a moderator, some stimulus material and a few prepared prompts (see Table A2 in online Appendix A for the moderator guide). The moderator was experienced in conducting focus groups and only gave limited input to either direct the discussion towards the research theme or to ask participants for clarifications when necessary.

Upon arrival, all participants answered a pre-discussion survey including a question about what they expect of political parties. This served as a primer for the discussion but, similar to our survey material, also as an opportunity for individual expressions minimally influenced by the moderator and/or group dynamics (see online Appendix B). The group discussion opened with a brief introduction and presentation of participants before moving to the first group exercise. The moderator presented a poster with the logos of all major Danish political parties (see Figure A2 in online Appendix A) and asked participants to write down individually three things that came to mind. The groups then discussed their thoughts. If it had not already naturally emerged as a point of discussion, the moderator prompted participants to reflect on their expectations of parties by asking: ‘What would you like from parties? What are your expectations for what parties should deliver?’ This first part of the discussion constitutes our focus group material for this study's analysis.

Our highly inductive start to the discussions, asking participants to only reflect on a poster with party logos, sent some of the discussions in less relevant directions about styles of logos. However, the individual task of writing down three reflections made every participant active from the very start and reduced the influence of dominant voices or social desirability bias. The prompt redirected discussions whenever necessary and resulted in rich, varied and informative data on expectations. The atmosphere was informal and friendly. Some participants were more outspoken than others, but the moderator made efforts to include everyone, and participants respected each other's right to participate. There were thus few interruptions and few long monologues or statements.

A student assistant attended the focus group discussions, subsequently transcribed the discussions staying as close to the authentic dialogue as possible and finally merged the transcription with observations of physical expressions. All transcriptions were fully anonymized.

Coding and analysing the empirical material

Since our empirical analysis aims to capture the range of meanings and content of voters’ expectations of parties, our coding of the material needed to reflect the fact that we had at least some theoretically grounded ideas but not a full picture. That is, the party linkage model provides distinct categories of the range and content of voters’ possible expectations towards parties’ functions. At the same time, the public opinion literature only offers first cues that voters’ expectations might go beyond that. Our solution to do justice to both is inspired by grounded theory because we combined deductive and inductive coding approaches (Azungah, Reference Alonso and Ruiz‐Rufino2018; Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006).

The deductive approach allows us to explore to what extent voters hold expectations in line with the party linkage model (see Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Farrell and McAllister2011). The inductive approach stays close to the empirical material and allows us to uncover expectations that deviate from this theoretical account. It means that the inductive codes are part of our results because they indicate that the theoretical account of the party linkage model does not exhaust the material, and they specify the content of voters’ additional expectations.

We coded our material by hand in NVivo to stay sensitive to the meaning and context of expressions of expectations in our material. Context was very important to regularly distinguish between different coding categories. First, we coded everything deductively. We used Dalton et al.’s (Reference Dalton, Farrell and McAllister2011, p. 7) conceptualization of each of the functional linkages and translated them into a provisional coding scheme (Miles et al., Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2014; Table B1 in online Appendix B). Using these deductive codes did not exhaust the material, neither in the survey data nor in the focus group data. Many important viewpoints could not be meaningfully captured by the functional linkage model alone.

In a second coding, we stayed close to the data to find expectations that our deductive approach had previously missed. We coded all expressions of wants or expectations (descriptive or normative) only in the focus group material because we were able to interpret the expressions with higher precision, given their contextuality. In our codes, we stayed as close to the exact wording as possible (Miles et al., Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2014), which resulted in 11 additional inductive codes: expertise, promise-keeping, policy-motivated, lawful, democratic vehicles, honest, unity, responsibility, administrating democracy, explaining democratic practice and solve problems (see Table B2 in online Appendix B for details). To be clear, these voter expectations were not defined by us ex ante but emerged when coding the material inductively, staying as close as possible to participants’ phrases.

To develop the final coding scheme, we used axial coding to group inductive codes based on the same theme (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006). Table B3 in online Appendix B and the accompanying text details the connections we made and why. This step resulted in a final coding scheme, involving eight main codes and four sub-codes. In this coding scheme, we maintained all codes developed from the party linkage model to show which functions voters expect (or maybe do not expect). The code definitions are adapted to fit the empirical material and hereby increase the reliability of the coding.

We carefully explored the validity and reliability of our final codes in multiple ways after both authors had coded the richer and more extensive focus group material, again using the final coding scheme. Our comparisons show that we reached high levels of coding agreement (72−100 per cent), identified expectations similarly across groups and participants and ranked expectations according to prevalence in the material in the same way (see Tables B4–B8 in online Appendix B). The high agreement in coding supports the notion of reliable and meaningful codes that are understood and applied in similar ways by different coders.

The content, structure and relevance of the virtuous party linkage model

Our discussion of the empirical material allows us to step out of a vague theoretical proposition and develop a concrete and coherent model explaining voters’ ambivalent attitudes towards parties. First, we specify the content of voters’ virtuous expectations, entailing expectations of parties to be reliable, competent and educational agents. Second, we explore the dimensionality of the virtuous party linkage model, finding that voters’ expectations of parties’ functional linkages and virtuous linkages co-exist and are at times interrelated. Third, we use the model to provide an initial interrogation of the different logics of attitudes towards parties, suggesting the prevalence of a logic of virtue failures rather than function failures.

The content of voters’ expectations of parties

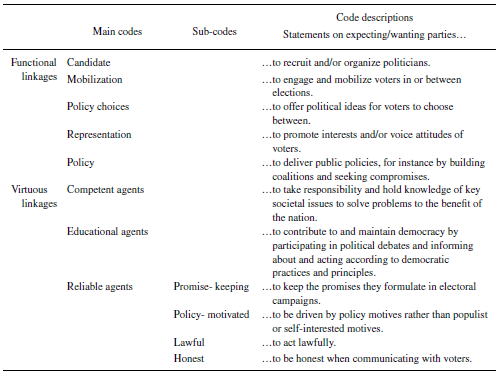

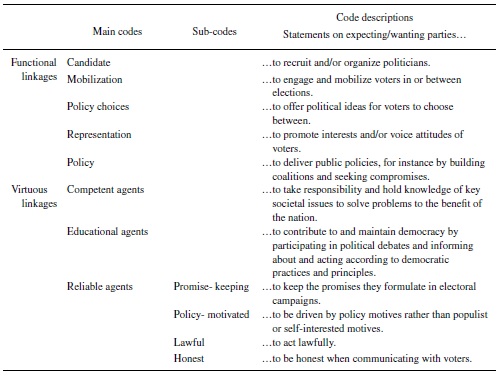

Table 2 shows the result of our axial coding and, by implication, displays the content of voters’ expectations of parties as identified by deductive and inductive coding processes. We arrived at three main codes that specify the content and meaning of the virtuous linkages because they all relate to non-policy-based traits. They are all about political parties as actors – not as organizations or institutions – and how voters want parties to display virtuous behaviour by being competent, educational and reliable.

Table 2. Coding list for party expectations

First, research subjects expressed expectations that political parties behave as competent agents. Expectations captured by this code related to parties’ knowledge about societal issues and ability to solve them to the benefit of the nation, even if this entails making unpopular decisions. Being a competent agent is about making responsible rather than responsive decisions and, as such, parties are expected to be competent and knowledgeable. While reminiscent of some conceptions of valence, this expectation is more specific by incorporating a possible trade-off between responsive and responsible decisions. Second, research subjects also expressed expectations that parties behave as educational agents, which emphasizes parties’ role as guardians of democracy. The expectation is that parties educate voters about democracy and lead by example through their own behaviour. Finally, they expressed expectations that parties act as reliable agents. This main code is divided into four sub-codes as the content of this expectation is more heterogeneous. As reliable agents, parties are expected to keep their promises, respect the law, be honest and be motivated by policy rather than office or votes.

These three main codes identify for the first time the specific democratic attitudes, motivations and traits that voters expect of individual parties. They strongly connect to a view of parties as democratic actors with distinct traits because they are chiefly about the purity of motives (policy rather than votes, office or self-interest), high competence (knowledge and ability to solve problems) and trustworthiness (honesty, promise-keeping and lawfulness). They are not about what parties deliver as institutions or organizations, but about how they individually deliver outputs as virtuous actors.

The structure and relevance of voters’ expectations of parties

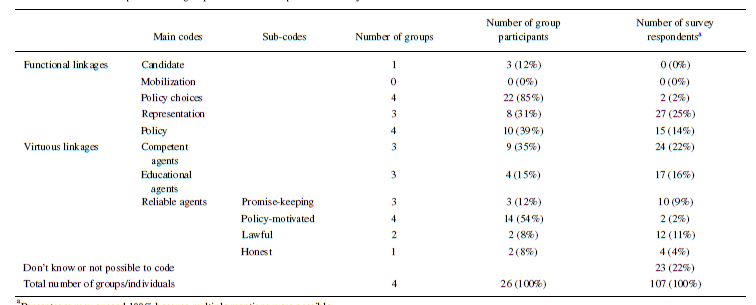

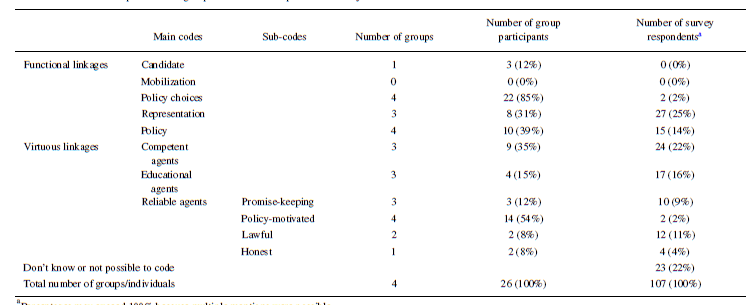

Based on our argument that voters hold expectations about parties’ functional linkages, we anticipated our coding to reveal expectations that parties will deliver on the functions specified in the party linkage model. Indeed, this is what we found. Table 3 summarizes the prevalence of the expectation codes in our focus group material on the individual and the group level and in our survey data. It shows how many groups discussed and how many participants or respondents mentioned the different expectations, and it hereby delivers a basic indication of the range, types and prevalence of voters’ expectations in our data. But it also indicates the differences in results across data collection methods. Overall, it shows that the majority of participants and respondents focus on policy-related aspects of parties, belonging to functional linkages. At the same time, the results also show the relevance of virtuous linkages.

Table 3. Prevalence of expectations in group discussions and open-ended survey data

a Percentages may exceed 100% because multiple mentions were possible.

According to Table 3 and beginning with the functional linkages, our focus group material revealed that expectations of parties to offer political ideas for voters to choose between (policy choices) was a dominant theme in discussions, but only little among survey respondents. One participant formulated this widely held expectation about parties as follows: “Also make it broad so that there is something for everyone [Participant A: “Yes.”]. That is why we would like to have many of them”Footnote 8 (Focus Group 2, Participant C). In this context, participants even engaged in discussions of how such choices should be established and, in this way, connected parties’ virtuous qualities as reliable agents that offer consistency with their functional linkages:

When you say that [parties] should follow the wishes of their voters, it is a two-way process because they should also offer a stable set of views to their voters. This is how I see it, or how I hope it is, so you can find a party that reflects your preferences. (Focus Group 3, Participant C)

Beyond talking about expectations of policy choice provision, the quote also exemplifies some participants’ awareness of ambivalent or even conflicting expectations: parties should follow but also remain stable. In other instances, participants reflected upon how parties should stick by their electoral pledges but also make compromises and enter coalitions. Such ‘within-person’ ambivalences were expressed by six participants and across all four groups (for full quotes, see Table B9 in the Online Appendix), and they illustrate how participants expect parties to balance multiple – and sometimes possibly conflicting – expectations, which in turn challenges parties’ chances to fully live up to voter expectations.

Another regular theme in discussions as well as in the survey material concerned expectations that parties deliver public policies, for instance, by building coalitions and seeking compromises (policy). Survey respondents mentioned, for example, that they expected parties to ‘find common solutions’ or ‘seek cooperation and work for the broad majority’. Similar views were expressed in our group discussions, as exemplified by Participant E in Focus Group 2: ‘But also just meeting in the middle is a good step, compromises to take responsibility’. By referencing responsibility as a virtue, this participant also connects policy and competent agent and thus the functional and virtuous linkages, respectively.

Additionally, participants entered here again rather sophisticated discussions on how parties need to balance different ends and elaborated on how they understood the workings of the Danish political system – for instance, ‘[Parties] should reach a balance between visions and compromises. Visions to inspire people. Compromises to make it work in practice’ (Focus Group 3, Participant E). These and similar expressions of expectations on the delivery of public policies occurred frequently in our empirical material.

However, participants also often said they expected parties to deliver even at the early stages of the policy-making process. They expected representation, that is, that parties promote the interests and/or voice the attitudes of voters. Indeed, this was the most prevalent theme in the survey data. Many respondents answered by writing, for example, ‘listening’, ‘listening to the people’ or ‘that they speak to and for the people’. Participants in the focus groups expressed their expectations similarly. Representative of many such expressions, Participant A in Focus Group 2 said, ‘Well, I think their task is that they should present, or represent the Danes’ attitudes’, or as stated by Participant G in Focus Group 3, ‘They should primarily present the views that their voters want’. Expectations on representation, strongly related to the party linkage model, were thus clearly expressed during most of our discussions.

Still, some functional linkages were present only very sparsely or not at all in our empirical material (see Table 3). For example, no one expressed the expectation that parties mobilize voters to engage in elections (mobilization). Similarly, none of the survey respondents and only a few participants in Focus Group 4 expressed expectations regarding the organization of candidates (candidates), such as, for example, Participant B: ‘What I wrote down was that it makes it easier to have to choose than to have to take a stand for 189 different people’. This quote also illustrates that participants see the functional benefits of parties as teams of politicians and can compare them to relevant alternatives. In sum, our analysis shows that research subjects formulated expectations corresponding to most, but not all, of the functional linkages specified in the literature.

A striking part of our analysis is the prevalence of other virtue-based expectations (see Table 3). While participants in a couple of instances mentioned virtuous linkages in connection with or as a means to fulfill functional linkages, as referenced above, participants most often expressed independent expectations about parties’ display of virtuous behaviour. One common expectation in the group discussions, but less so among survey respondents, concerned the presumed motivation underlying political parties’ actions (policy-motivated). For instance, as Participant E in Focus Group 1 described: ‘Too many sit there because it is a job, not because they are fighting for something’. The same idea was also clearly reflected in more nuanced ways in a dialogue within Focus Group 2:

Participant E: I have a question. Because I think there is something [political parties] are really good at but I do not find it desirable. I think they are good at feathering their own nest. And this is not desirable, that they want to hold on to power at any cost. But it is a question, what do you think about it?

Participant D: Yes certainly. Power for the sake of power is not good, but I wonder if getting power has a self-reinforcing effect, so it runs in circles. I think it happens sometimes. Then it runs off track in terms of representing the people or making the right decisions because it is about holding on to power to get more power.

Participant C: Yes, and they start changing their position to get more votes rather than holding on to their program.

Participant D: Exactly!

The dialogue illustrates significant distrust in the motives behind the behaviour of political parties, which was also evident in Focus Group 4: ‘Well it is about what you are aiming for. They are out to win power, right’ (Participant G), ‘Or to follow their voters’ (Participant B). The notion that political parties are vote- and office-seekers rather than policy-seekers created a sense of cynicism when participants interpreted and discussed party behaviour. They expect parties to be motivated by policy, but any policy declaration is interpreted as being ‘truly’ motivated by maximizing votes or power. Although this expectation is chiefly about how parties behave, it does suggest that there is a default understanding of parties as institutions with specific functions as well and that expectations about parties’ functions and virtuous behaviour form a complex interplay.

The dialogue cited above is also an example of how our research subjects expressed expectations indirectly, criticizing parties for something undesirable they are perceived to be doing – descriptive expectations – rather than expressing positively what they would want them to do – normative expectations.

Another example of such indirectly expressed expectations occurred in relation to the recurring theme of Promise-keeping: ‘That they are not always good at keeping their election promises is something completely different’ (Participant B, Focus Group 1). In the survey, respondents expressed their expectations around promise-keeping more positively by simply noting, for example, ‘Keep what they say’ or ‘Live up to what they have promised!’ While the expectation of promise-keeping also features in Dalton et al.’s (Reference Dalton, Farrell and McAllister2011) party linkage model as part of ‘policy’, in our group discussions it was discussed as a value in its own right and a trait of parties. Parties were thought of as unable or unwilling to keep their promises and therefore not trustworthy. Relatedly, survey respondents in particularly mentioned expectations that parties be law abiding through answers like ‘Follow the constitution’ or ‘Comply with the law’. Together with less prevalent expectations that parties be honest, these expressions reflect a larger set of expectations that parties are reliable agents motivated by policy, keeping their promises, respecting the law and being honest (see Table 3).

Beyond reliable agents, our analysis also uncovered the prevalent expectation that parties be virtuous by being competent agents. Voters expressed the desire and expectation that parties be informed to solve the ‘right’ problems with the ‘right’ decisions. A dominant category in our survey material, typical answers were ‘They take care of the Danish population as best as possible’, ‘Take care of the population and make the right decisions’ or simply ‘Take responsibility’. This expectation also emerged in the focus group discussions, for instance in Focus Group 3:

Participant A: I think that one of their main tasks is to discuss issues of most importance to society because that opens for new perspectives and positions for those of us who do not sit and discuss these matters. They should discuss on behalf of us.

Participant B: I wrote that parties should respect and administer the law. Which you see a lot of examples of them not being capable of. But I think this is the most basic and important thing that parliament and political parties do.

Participant A: Yes, but I also came to think about – I fully agree with you – but I also think that one of their major tasks is to develop our society because they are the ones who propose new bills and sort of keep up with the times and are aware of what is important for our society, at the moment. Because it changes all the time.

Participant G: Surely, they should promote the views of their voters. That has to be their goal.

Participant D: But I also think parties should – because they run for election – be curious and hold knowledge about what they are doing. Sometimes it is like ‘Here is an example of something being bad, let's make some legislation,’ but you have to be curious and look more broadly at the problem.

Participant A: Yes, and it might also be here that political parties have other opportunities to investigate a problem that we as ordinary individual[s] do not have.

In this case, the dialogue is less focused and consensual. This is partly driven by the format as they are in the process of sharing their written notes. Nonetheless, the disagreement reflects a classic discussion in the political representation literature: whether representatives should mainly act as delegates – promote the views of their voters – or as trustees – discussing and investigating on behalf of voters (see, e.g., Rehfeld, Reference Rehfeld2009). The theme of competent agents more closely reflects the trustee notion as parties are expected to hold or collect knowledge to make informed decisions on behalf of voters for the benefit of society. This may even go against the immediate wishes of the voters, as Participant D in Focus Group 2 acknowledged: ‘But this is what we are discussing, whether the popular attitude of the population is necessarily the “right attitude”, because did we not agree just before that politicians sometimes have to make the unpleasant decisions that go against what the population says?’ It means that participants recognized the difficulties political parties sometimes find themselves in, and many expect them to act as responsible agents in such situations.

A final expectation, related to virtuous linkages, concerned the contribution of parties to democracy by being educational agents (see Table 3). This was expressed, for example, in Focus Group 2 when discussions revolved around how parties should guard the democracy they have inherited. For instance, Participant F in Focus Group 2 explained that s/he wants parties to make people understand democracy:

Yes, but that means that we actually understand democracy when it works. It is like when the young people say so much noise is created, there are many individual issues, there are very different directions. But this is not democracy as we understand it.

Survey respondents indicated similar expectations even more frequently (see Table 3), for example, by noting, ‘I expect them to act with respect for the democratic tradition and good governance’, ‘Behave democratically’ or ‘Behave properly, that is, both listen and argue matter-of-factly. And that the majority has respect for the minority’. In essence, this theme reflected expectations that parties participate in political debates and inform the public about and act according to democratic practices and principles.

In sum, our analysis exploring the dimensionality of the virtuous party linkage model yields both substantive and methodological findings. Substantively, it shows that voters’ expectations of parties’ functional linkages and virtuous linkages co-exist and are at times interrelated. Specifically, it demonstrates that voters have expectations that parties deliver on many of the well-known functional linkages (e.g., policy-related functions), but that they also have expectations regarding parties’ displays of virtuous behaviour in the form of being reliable, competent and educational agents when delivering on the functional linkages. It, therefore, suggests that voters expect democratic outputs from parties but also that these outputs are delivered virtuously (e.g., reliable agents delivering policy choices or policy; competent agents delivering policy).

Beyond that, the foregoing analysis also yields methodological findings. While the substantive finding does not differ between the two vastly different data collection methods, the relative prevalence of each of the expectations differs. One possible explanation could be that focus group participants could choose from a larger repertoire to express their expectations, compared to survey respondents. Our analysis shows that group participants also used the group conversation to express their preferences in indirect ways, for example, through sarcasm or by referencing more descriptive rather than normative expectations. Survey respondents only responded to the precise question with whatever came to their mind first. Responses were thus much briefer (on average 46 characters) and also less precise. For example, some survey answers required substantial interpretation due to their brevity (e.g., ‘Collaborate’, ‘Help us’, etc.). What is more, Table 3 also shows that a total of 23 (22 per cent) survey respondents did not express any expectations at all, whereas all group participants expressed at least one.

Based on that, it seems doubtful that we would have reached the substantive finding with the same precision and nuance using the survey material alone. This suggests that – compared to open-ended survey answers – focus group data provide richer and more nuanced information from a variety of voters, crucial for exploratory work in general and data-based theory development specifically.

Exploring logics of attitudes towards parties

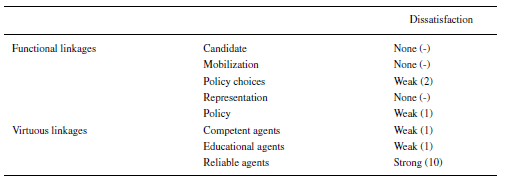

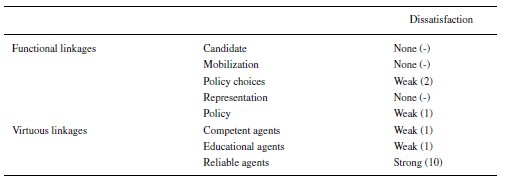

In this final section of results, we draw on the insights gathered thus far to provide an initial interrogation of logics of attitudes towards parties. This is only possible with the help of our focus group material. To do so, we exploited our highly open and inductive research design further and made use of the fact that the moderator did not ask about levels of satisfaction. It means that all expressions of (dis)satisfaction in this part of the focus group discussion occurred spontaneously as participants reflected upon their expectations. They reflect voters’ instinctive perceptions and concerns. We conducted an additional coding of the material, identifying spontaneous expressions of dissatisfaction with parties in connection with any of the expectations. Dissatisfaction is coded when participants explicitly expressed disappointment with parties’ performance or critically evaluated the way they perceived parties to be performing.

According to the prevailing logic of parties’ linkage failures, participants’ dissatisfactions should appear in conjunction with expressions of functional expectations. On the other hand, according to our proposed logic of parties’ virtue failures, dissatisfaction should surface in connection with expectations of parties’ democratic virtues.

Table 4 shows that expressions of dissatisfaction are strong regarding parties as reliable agents. Participants most often questioned the motives of political parties. The discussions also included expressions of dissatisfaction with parties’ abilities to deliver policy choices and policy and be competent or educational agents, but such expressions were much less prevalent (see Table 4).

Table 4. Prevalence of spontaneous expressions of dissatisfaction with political parties

Note: Numbers in parentheses reflect the number of identified statements on dissatisfaction with party performance or behaviour.

Our material also revealed that evaluations of parties performing against expectations were not always shared. Expressions of dissatisfaction were sometimes countered with expressions of satisfaction by other participants. For instance, Participant F in Focus Group 4 reflected on Danish people's views of parties and how harsh they are on them on social media but still concluded that in the end ‘[…] we trust that they are actually doing well’. However, Participant G responds directly to this by objecting ‘I suspect that political parties – all of them – sometimes do not do what is best for Denmark but what is best for themselves’. It illustrates that while there may be widespread agreement on what to expect of political parties, assessments of the extent to which they live up to these expectations differ.

In sum, our analysis reveals that spontaneous expressions of dissatisfaction were more often spurred when participants reflected upon virtuous linkages (or parties as actors) rather than functional linkages (or parties as institutions). This demonstrates the value of the virtuous party linkage model in understanding voters’ ambivalent attitudes towards parties: Voters hold functional as well as virtuous expectations of political parties, so even when voters do not express dissatisfaction with parties’ functional linkages, they still want more. They want parties to be virtuous actors, and they find that these expectations are not met. As a result, voters’ ambivalent attitudes may be explained by the two-dimensionality of their expectations: Voters consider parties necessary because they see them as fulfilling democratic functions, but they dislike them because they are seen as behaving in non-virtuous ways when fulfilling their functions.

Conclusion

Our study began with an empirical puzzle: Why do voters find political parties necessary but strongly dislike them? Based on public opinion research, we argued that this puzzle can only be solved if we develop analytical models to systematically study what voters expect of parties, as expectations and attitudes correlate. Combining different and hitherto disconnected literature on attitudes towards parties, we first sketched the contours of a new explanation for voters’ ambivalent attitudes towards parties. To refine our idea, we used an exploratory methodology applied to rich empirical material that allowed us to identify, formulate and validate our theoretical constructs.

Combining deductive and inductive coding procedures applied to different sets of public opinion data from Denmark, we first specify and conceptualize the content of virtuous linkages, which entails expectations that political parties be competent, reliable and educational actors. Hereby, we provide an empirically informed structure to hitherto separate yet important literature on voter non-policy-related evaluations of political parties. Second, we explore the dimensionality of voters’ expectations and find that functional and virtuous linkages co-exist. The virtuous linkages move beyond functional linkages as voters not only expect parties to promote their voters’ policy preferences but also to do so in a competent, educational and reliable manner. The two kinds of linkages can at times be connected as the virtuous part describes how parties are expected to deliver on the functional linkages.

With the resulting virtuous party linkage model, we propose a reconceptualization of party linkages as encompassing interrelated dimensions, one connected to parties’ democratic outcomes and one connected to their display of democratic virtues. This comports well with various strands of existing literature in party politics and public opinion research. As a result, we theorized a novel explanation for voters’ ambivalent attitudes towards parties: Voters in modern democracies consider parties necessary because they see them as fulfilling democratic functions, but they dislike them because they see them as behaving in non-virtuous ways when fulfilling their functions.

This is a substantively important theoretical heuristic that moves significantly beyond the current literature because it acknowledges the dual nature of parties as institutions and actors in the democratic game. The existing literature has largely evolved in parallel, but we show that their integration is not only possible but can also answer long-standing research puzzles. Additionally, our findings have implications for how we think about common survey questions to evaluate political parties. Typically, political parties are lumped together with other institutions as part of a battery of questions on trust, confidence or satisfaction. Our findings suggest that evaluations of parties could be different from other political institutions because they go beyond a purely institutional perspective. Another possible lesson is that we need to supplement existing surveys with questions related to both dimensions of party linkages. It could allow for a more generalizable understanding of why (some) voters trust parties or not as well as which and when voters use the different dimensions relatively more. We also contribute methodologically to the literature by illustrating the development of data-based theories in public opinion research, using vastly different data collection methods.

Our substantive findings give rise to several new considerations. For example, our model was developed in the context of an extreme case of relatively high-performing political parties. The generalizability of the empirical prevalence of the different linkages is thus limited by time and space. The importance of linkage dimensions (functions and virtues) may differ in contexts of lower performing political parties where voters may express stronger expectations for functional deliveries or maybe emphasize the sub-dimension of law-abiding conduct more relative to the motivational aspect so strongly expressed by the Danish participants. Our empirical material does not allow for an investigation of such variation, but the virtuous party linkage model provides an analytical framework to explore such variation in a systematic and comparative manner.

In addition, we identified a lack of expectation regarding key party functions: organizing candidates and mobilizing voters. Since this is factually a function of parties, it does not mean that the theory is wrong. It may simply mean that (our) voters do not appreciate or acknowledge key deliveries from political parties to democracy. The two neglected functions both relate to political parties as organizations, organizing candidates, members and voters, rather than as unitary actors, delivering policy choices and decisions. This is a surprising finding from a context in which political parties maintain relatively strong ties to voters (Allern et al., Reference Allern, Aylott and Christiansen2007; Bille, Reference Bille2001; Green-Pedersen & Kosiara-Pedersen, Reference Green‐Pedersen, Kosiara‐Pedersen, Christiansen, Elklit and Nadergaard2020). It suggests the possibility of a kind of visibility bias amongst voters in this particular context (but possibly not others) as the result of taking parties’ organizational functions for granted. Voters’ dissatisfaction may thus also be the consequence of them losing sight of political parties as political organizations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editors and reviewers for their careful comments and suggestions during the review process. We also thank participants at the Party Politics section at Aarhus University, at the workshop on Representation and Citizens’ Beliefs and Behaviours at Basel University, at the workshop on (Intra-)Party Politics at the University of Gothenburg, at the Democracy and Election and Cathie Marsh Institute Workshop at the University of Manchester and the research seminar on political parties at the Nottingham Trent University. Moreover, we are grateful for helpful comments from Susan Scarrow, Kate Dommett, Peter Esaiasson, Kristina Bakkær Simonsen, Rune Slothuus, Morgan Le Corre Juratic and Mathilde Cecchini on research design and early versions of the paper. The research is supported by the Aarhus University Research Fund (AUFF), project number: AUFF-E2017-7-13/

Conflict of interest statement

There is no conflict of interest to declare.

Data availability statement

Data for this study is available on Harvard's Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/0P86ZR.

[Correction added on 11 June 2024, after first online publication: Data Availability Statement section has been updated in this version.]

Ethical approval statement

Ethical considerations are discussed in detail in the online appendix (online Appendix C). The study is conducted with participants’ informed consent and no deception is involved.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: