Introduction

In human research, ensuring participant comprehension of informed consent documents (ICDs) remains a significant challenge, largely due to their excessive length and complex language [Reference Bazzano, Durant and Brantley1]. Substantial changes are required to improve the process for responsible and equitable participant comprehension and consent. Recognizing this, the 2018 Common Rule revisions mandated the inclusion of a “Key Information” (KI) section at the outset of ICDs, aimed at distilling essential details into a reader-friendly format [2]. In March 2024, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services released “draft guidance” to promote KI standardization [3].

Despite these advancements, the current guidelines are still limited, broadly outlining focus on (1) voluntary consent, (2) research objectives, duration, and procedures, (3) transparent risk communication, (4) benefit disclosure, and (5) alternative treatment options [Reference Gelinas, Morrell, Tse, Glazier, Zarin and Bierer4]. While the absence of specific instructions offers flexibility to author individualized KIs for research studies [2], the lack of a strong template creates potential inconsistencies in style, length and content of KI sections within and between institutions. This could potentially lead to complexities in ICD reviews by different institutional review boards (IRBs) and a failure to enhance participant comprehension. Accordingly, this study examined whether a large language model (LLM)-assisted, template-guided approach could standardize the style, content emphasis, and (by design) overall conciseness of KI sections, thereby reducing the variability that burdens PIs and IRBs.

To bridge this gap, our multi-phased study explored the innovative application of LLMs, like GPT-4o, in crafting tailored KI sections for ICDs. LLMs stand out for their ability to digest vast textual datasets and generate clear, concise text through well-crafted instructions, or prompts [Reference Ouyang, Wu and Jiang5]. To first validate the efficacy of this novel tool, IRB subject matter experts (SMEs) compared and scored AI-generated KI sections against those authored by principal investigators (PIs) for the same consent documents. The evaluation criteria encompassed (1) factual accuracy, (2) standard of care vs. research procedure differentiation, (3) information weighting, and (4) style and structure. Collectively these four scored domains provided qualitative indicators of cross-document consistency in content emphasis and presentation. After iterative training of the tool, our multi-phased evaluation process involving PIs and IRB reviewers found that AI-generated KI sections can streamline the creation process and simplify content, while effectively accommodating the unique demands of various research studies. This initiative contributes to the evolving dialogue on refining the consent process in human subjects’ research, spotlighting the potential of AI-driven solutions to help alleviate hurdles in study review and participant comprehension.

Methods

Development of prototype AI tool for key information sections

ICD template language dissection

In the pursuit of generating KI sections by AI, we adopted a multi-layered approach. First, we evaluated existing IRB template language for ICDs at the University of Michigan Medical School (UMMS). The ICD template comprises nine primary content sections, with seven being dynamic, adapting to the specifics of the research such as child enrollment, primary study objectives, randomization involvement, potential risks, anticipated benefits, study participation duration, and alternative treatment options. The remaining two sections are consistent across all human subjects’ research.

We subsequently broke down each section’s primary objective into a series of questions, or queries, to guide AI to relevant ICD information. For example, the inquiry “Are children eligible to participate?” was reformulated into specific questions, including “Who can take part in this study?”, “What are the eligibility criteria?”, “Can children participate?”, and “Are specific roles designed for underage participants?”. This “deconstruction” served two purposes: (1) directing the AI to pertinent ICD information and (2) prompting it with questions to distill crucial details. Thus, the AI tool can now determine child inclusion in research by identifying implied roles for underage participants within the ICD, even if it was not explicitly stated.

Meta-language development

To retain essential ICD template language and infuse appropriate details from the approved ICD, we formulated a meta-language. Double angle brackets (<<>>) containing options were separated by double slashes (//), instructing the model to choose among them. Double curly brackets ({{ }}) enclosed instructions for the model to replace with an output based on those instructions. For example: “This research is <<studying//collecting>> <<a//a new//>>{{state the general category of the object of the study, e.g., ‘drug’, ‘device’, ‘procedure’, ‘information’, ‘biospecimens’, ‘behavioral change’, ‘diagnostic tool’, etc. Indicate FDA approval status}} in <<people//large numbers of people//small numbers of people//children//large numbers of children//small numbers of children>>. The purpose is to {{briefly describe the purpose of the study}}. This study will {{briefly describe goals or objectives}}. Your health-related information will be collected during this research. {{If biospecimen collection will be performed, indicate here; otherwise, omit}}.”

The tool was also programed to assume the role of a bioethicist, specializing in patient advocacy and human subjects’ research. This permitted it to interpret ICDs with an emphasis on clarity, authority, and accuracy, without any self-reference as AI.

Semantic sectioning approach

In developing our AI tool, we encountered the text processing limitations inherent in current LLMs, such as GPT −3.5 [Reference Alawida, Mejri, Mehmood, Chikhaoui and Isaac6]. Text bodies, termed “context” for language generators, prioritize processing at the beginning and end of a “context window.” Consequently, larger text bodies are more susceptible to the “lost in the middle phenomenon [Reference Sallam7].” We then implemented a strategy of dividing the text into smaller sections, enabling the tool to retrieve only the most relevant information for each query. However, overly small sections risk omitting crucial “context,” while excessively large sections may introduce non-relevant information.

To overcome this challenge, we adopted a semantic sectioning approach [Reference Salloum, Khan, Shaalan, Hassanien, Azar, Gaber, Oliva and Tolba8]. This retrieval process happens for every query within each section of the ICD template. Retrieved answers are added to a list, which acts as “context” for creating KI section text from the meta-language instructions. Finally, the AI tool acts as an editor, checking for formatting consistency and grammatical accuracy, while removing unnecessary elements like quotation marks, triple backticks, citations, and double brackets (See Supplemental Material 1 for complete GitHub code of the AI tool). Through this process, we successfully generated AI-based KI content for rigorous evaluation.

Multi-phased evaluation of the prototype AI tool

Phases 1: Evaluations by IRB SMEs

Our sample included 27 ICDs authored by PIs (human-authored) and approved by the UMMS IRB. It is important to note that the AI tool never had access to the human-authored KI sections. These documents encompassed a range of study modalities, including clinical trials for drugs and medical devices, data registries, cancer and other health studies, and pediatric research. Using these documents as a reference, IRB SMEs evaluated whether the AI tool could deliver KI content associated with the ICD that was: (1) factually accurate, (2) capable of distinguishing between standard medical procedures (standard of care) and research-related activities, (3) adept at identifying pertinent information for inclusion (information weighting), and (4) consistent in style and structure (Figures 1 and 2).

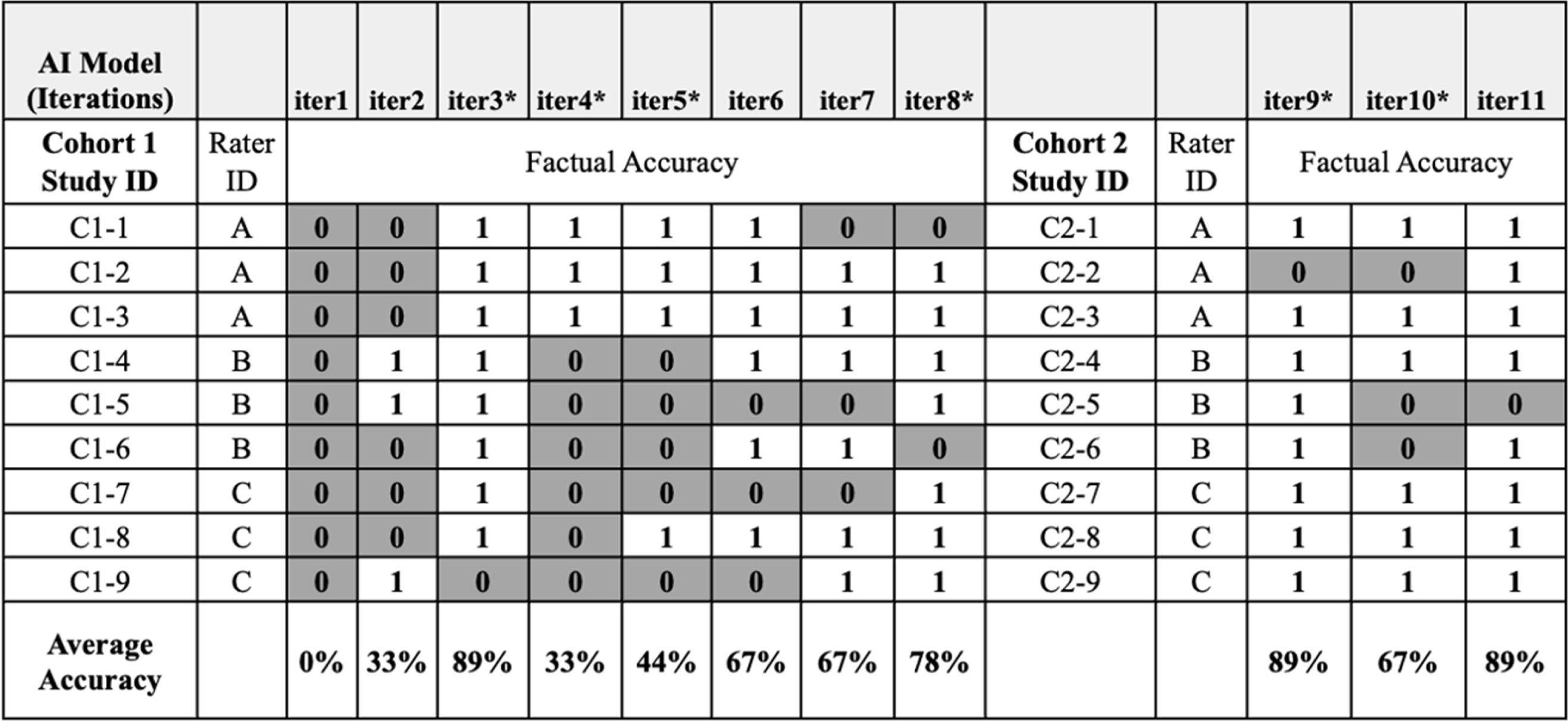

Figure 1. Institutional review board (IRB) subject matter experts (SMEs) factual accuracy assessment of artificial intelligence (AI)-generated key information (KI) sections. Cohort 1: IRB SMEs evaluated assigned KI sections produced from eight (8) iterations of the AI tool; each new KI output was assessed for factual accuracy against the original IRB-approved, human-authored KI section. Individual raters were assigned 3 different consents but assessed each of the consents for all 8 iterations (iter1–8). Cohort 2: IRB SMEs evaluated a new series of designated informed consents across 3 AI iterations (iter9–11) to ensure the AI tool’s adaptability to varied content it had not seen previously. DARK GRAY – Not factually correct, WHITE – Factually correct, C1: Cohort 1 (Initial set of studies), C2: Cohort 2 (Subsequent set of studies), iter1–11: refers to consecutive iterations of AI model.

*Major updates to the content or delivery of prompts.

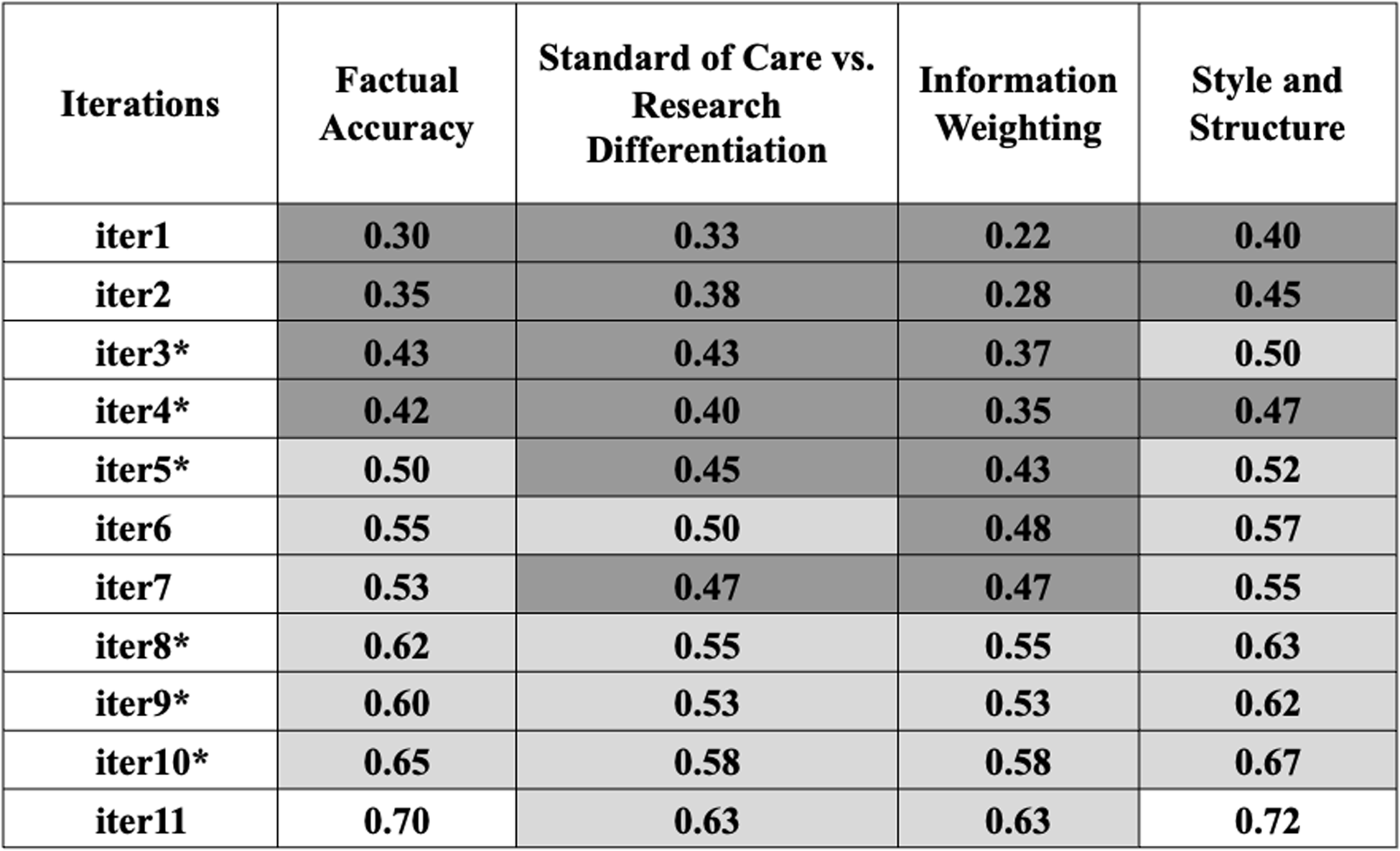

Figure 2. Additional institutional review board (IRB) subject matter experts (SMEs) assessment of artificial intelligence (AI)-generated key information (KI) sections. Comments were evaluated using ChatGPT-4o in four categories: (1) factual accuracy, (2) standard of care vs. research differentiation, (3) information weighting, and (4) style and structure. Scores range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating better performance (See Supplemental Material 4 for detailed prompt instructions on the IRB SME’s comment analysis conducted by ChatGPT-4o). The color-coded table uses darker gray for lower scores and lighter gray for higher scores, illustrating the changes in accuracy, clarity, and relevance from iteration 1 to 11 (iter1–11).

*Major updates to the content or delivery of prompts. Low accuracy ![]() High accuracy; iter1-11: refers to consecutive iterations of AI model.

High accuracy; iter1-11: refers to consecutive iterations of AI model.

IRB SMEs assessed AI-generated KI sections across two cohorts of documents. In Cohort 1, they compared a single human-authored KI section against eight successive versions of AI-generated KI sections, each enhanced through iterative training of the tool. For Cohort 2, IRB SMEs utilized a new series of human-authored KIs to evaluate the AI tool’s adaptability to varied content it had not previously encountered. IRB SMEs scored each AI iteration on four preset criteria – factual accuracy, differentiation of standard care vs research, information weighting (content emphasis), and style & structure (formatting coherence) – providing qualitative indicators of cross-document consistency (Figure 2).

Phase 2: Evaluations by PIs

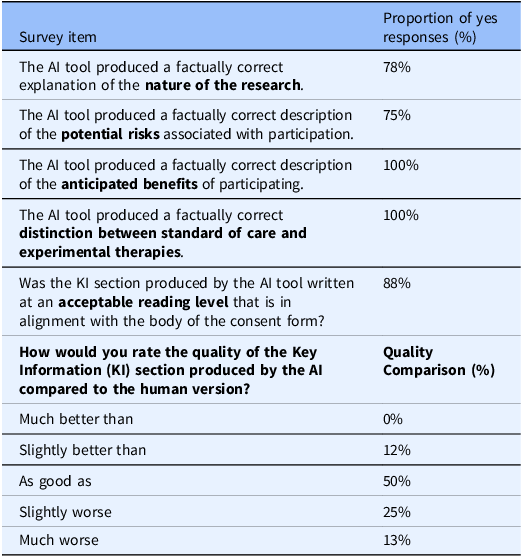

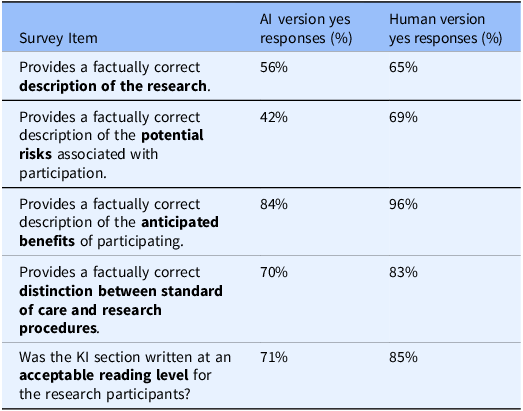

After the IRB SMEs validated the tool, selected PIs were invited to participate. They compared and rated the AI-generated KI sections against their own human-authored ICDs and KI sections, evaluating factual accuracy in relation to the nature of the research, potential risks, anticipated benefits of study participation, and the distinction between standard of care and research (Table 1). The PIs also evaluated whether the AI-generated KI sections were written at an appropriate reading level to facilitate participant understanding. For this phase, we created a survey to systematically collect PI feedback (Supplemental Material 2 for detailed PI survey questions). This integration of medical expertise enriched our analysis, providing comprehensive perspectives on biomedical human research.

Table 1. Principal Investigators’ evaluation of artificial intelligence (AI)-generated key information (KI) sections

PI survey responses evaluating the AI tool’s performance in generating KI sections. The survey assessed factual accuracy regarding the nature of research, potential risks, anticipated benefits, distinction between standard of care vs. research, alignment with acceptable reading level against the ICD, and the quality of AI-generated KI section compared to human-authored KI section.

Phase 3: Blinded evaluations by IRB reviewers

To evaluate the regulatory compliance of AI-generated KI sections, the final phase of the study consisted of blinded assessments involving IRB reviewers, including the IRB chair or vice-chair, the study’s primary reviewer, a non-scientist IRB member, and IRB staff. The IRB reviewers were presented with two versions of each KI section, labeled “A” and “B,” without any indication of whether a version was AI-generated or human-authored. They were tasked with assessing the compliance of each version with established federal and institutional regulatory standards.

The selection process for the studies under evaluation followed a structured approach. Studies, previously approved through an IRB review, had to fall within a six-month period from January 2023 to June 2023 to ensure they were at least a year old, minimizing recall bias among reviewers. Only new studies and studies undergoing amendments were selected.

To capture a wide array of research types and contexts, studies were also chosen to represent diversity in risk levels, benefit levels, research purposes, and sponsor types. Preference was given to studies that had significant discussion during IRB meetings (as documented by meeting minutes), particularly around informed consent, as this was central to the study’s objective of evaluating KI sections. Three studies were selected from each of the six IRBs, totaling 18 studies. To collect feedback, the phase 2 (PIs’ evaluation) survey was further refined with specific questions, as IRB reviewers were unaware of whether the KI sections were human-authored or AI-generated. (Supplemental Material 3 for detailed IRB reviewers survey questions).

Results

Content optimization and refinement over iterations by IRB SMEs

The first obstacle encountered by IRB SMEs in assessing early iterations of the AI tool was its tendency to ‘hallucinate’ information, such as generating incorrect or unrelated content. For example, in iteration 2 (iter2), the AI tool erroneously produced a KI section stating the study focused on Alzheimer’s disease, when it centered on prostate cancer (Figure 1). Additionally, the AI tool struggled to accurately abstract information when the ICD content was ambiguous or contained complex clinical terminology. However, the tool’s ability to produce factually accurate content improved over multiple iterations, with a positive upward trend in factual accuracy when comparing iteration 1 (iter1) to iteration 8 (iter8) (Figure 1). Modifications to the AI tool prior to iteration 4 (iter4) and 5 (iter5) resulted in higher factual error rates, likely due to significant changes in the linguistic instructions. After providing refined guidance for iteration 8 (iter8), factual accuracy resumed its upward trajectory, and iterations 9 to 11 (iters9–11) showed relative stability in factual accuracy, despite ongoing modifications (Figure 1).

IRB SMEs not only scrutinized factual accuracy but also evaluated the tool’s performance in three other critical areas: differentiating between standard of care and research, information weighting, and maintaining consistent style and structure. To begin thematic mapping, initial human rater assessment was conducted on the open-ended qualitative comments from IRB SMEs. To remove human subjectivity and provide a secondary method of validation, ChatGPT-4o was also employed to analyze IRB SMEs’ comments on each successive AI-generated KI section. It assessed the extent of focus on each category and assigned a score from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating better performance (See Supplemental Material 4 for detailed prompt instructions on the IRB SME’s comment analysis conducted by ChatGPT-4o). Early iterations of the tool did not meet acceptable standards across all categories (Figure 2). However, following the linguistic modifications introduced in iterations 4, 5, and 8 (iter4, iter5, and iter8), the tool showed significant improvements across all three categories (Figure 2). As iterations progressed, IRB SME scores for both “information weighting” and “style & structure” converged toward the upper end of the 0–1 scale, signaling increasing uniformity across KI drafts. Although we did not formally quantify word count, the meta-language template constrains the space allocated to each required KI element, which inherently keeps AI-generated KI sections to a similar, succinct length.

PIs’ evaluation of AI-generated KI sections

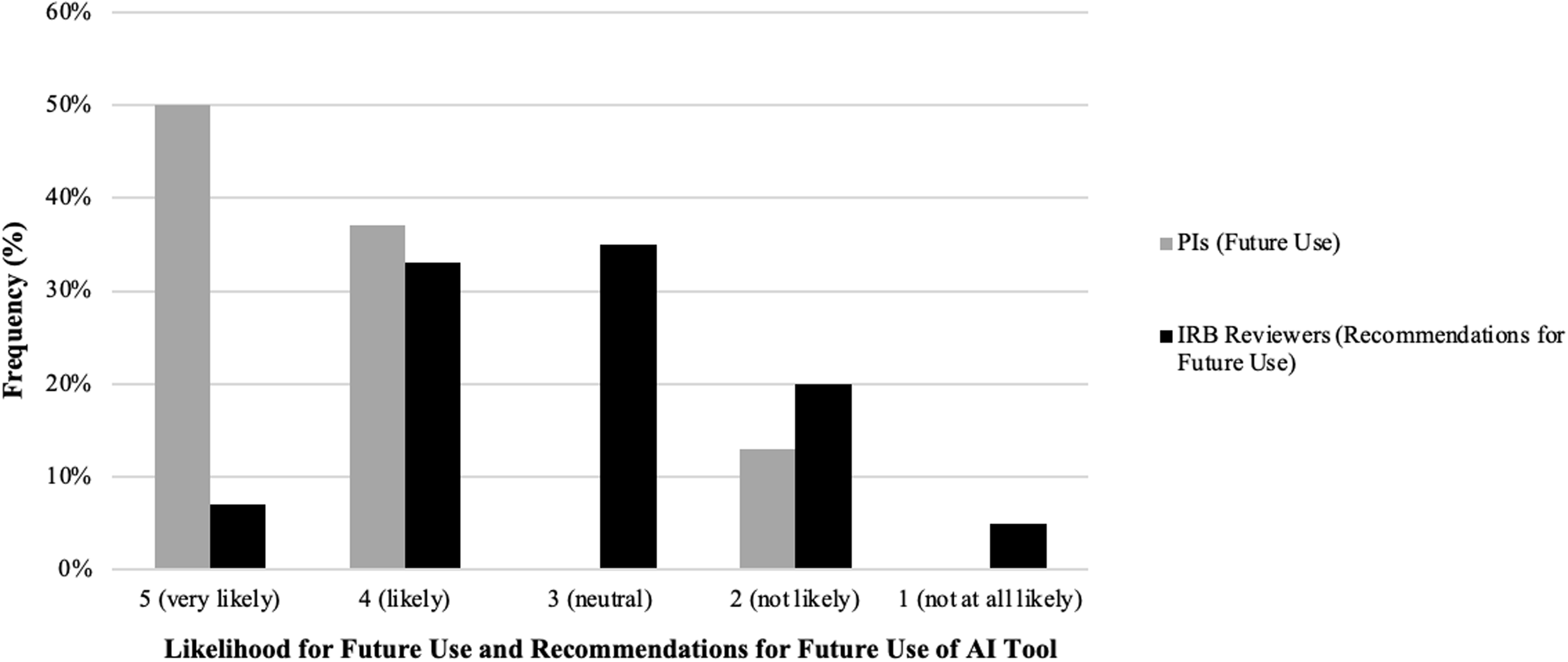

Following the IRB SME evaluation, PIs with diverse medical expertise assessed AI-generated KI content by comparing it to their own previously IRB approved, human-authored, KI sections. Overall, 78% of PIs rated the tool highly for factual accuracy regarding the nature of research. At least one PI reported a factual inaccuracy related to the risks associated with study participation, although the accuracy regarding benefits was high (100%) (Table 1). Additionally, 88% of PIs indicated that the AI-generated KI sections were written at an appropriate reading level and aligned well with the original human-authored ICD. PIs then rated the quality of the AI-generated KI sections in comparison to their own. More than half rated the AI version as “as good as” or “slightly better than” their original KI sections (50% and 12%, respectively) (Table 1). Impressively, when asked if they would utilize the AI tool for future KI drafting, 87% of PIs indicated they were “very likely” or “likely” (ratings of 4 or 5) to use the tool. None were neutral, and 13% reported they were “not likely” (ratings of 1 or 2) to use the AI tool in the future (Figure 3). Taken together, these results underscore the AI tool’s potential to aid PIs in drafting KI sections for ICDs while highlighting the need for further refinement to address concerns about factual accuracy, particularly regarding study risks.

Figure 3. Principal Investigator (PI) and Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewer perspectives on using an artificial intelligence (AI) tool to draft key information (KI) sections: comparison between future use and recommendations. Comparison of likelihood for future use and recommendation for future use of the AI tool between PIs and IRB reviewers. The side-by-side bar chart shows the frequency distribution of responses across five Likert scale categories: “5 (very likely),” “4 (likely),” “3 (neutral),” “2 (not likely),” and “1 (not at all likely)” (x-axis). Gray bars represent PI likelihood of future use, while black bars represent IRB reviewer likelihood to recommend for future use. The y-axis displays the percentage frequency of responses within each category.

IRB reviewers’ blinded evaluations of AI-generated KI sections

In the last phase of the study, IRB reviewers assessed two versions of KI sections for factual accuracy, readability, and potential usability in drafting KI sections (reviewers were not aware which KI version was human-authored vs. AI-generated). Based on survey results, 56% of IRB reviewers found the AI-generated KI sections provided a factually correct description of the research (Table 2). Ratings were lower for descriptions of potential risks, with only 42% of reviewers deeming the AI-generated content factually correct (Table 2). In contrast, 84% of reviewers agreed that the AI tool accurately described the anticipated benefits of participation (Table 2).

Table 2. IRB reviewers’ evaluation of artificial intelligence (AI) vs. human generated key information (KI) sections

IRB reviewers survey responses evaluating the AI tool’s performance in generating KI sections. The survey assessed factual accuracy regarding the nature of research, potential risks, anticipated benefits, distinction between standard of care vs. research, and alignment with acceptable reading level against the ICD.

Regarding readability, 71% of IRB reviewers indicated that the AI-generated KI sections were written at an acceptable reading level and aligned well with the body of the consent form (Table 2). IRB reviewers also used a 5-point Likert scale to evaluate the likelihood of recommending the tool to PIs in the future. Results revealed that 40% of IRB reviewers rated their likelihood of recommendation as “likely” or “very likely” (scores of 4 or 5) (Figure 3). In contrast, 25% indicated they were “unlikely” or “not at all likely” (scores of 1 or 2) to recommend the tool (Figure 3). Interestingly, 35% of reviewers gave a neutral rating of 3, indicating that the tool may require further refinements to improve user confidence and usability (Figure 3). Together, these findings highlight the AI tool’s strengths in describing study benefits and maintaining readability while underscoring the need for further improvements, particularly in ensuring accurate risk descriptions to enhance regulatory compliance and IRB reviewer confidence.

Discussion

As AI implementation gains traction within clinical and translational sciences, we recognized the importance of developing AI-driven tools that not only foster innovation but also align with federal guidelines to protect human subject rights and well-being. The creation of the prototype AI tool to draft KI sections of ICDs represents a significant step toward supporting PIs in this process. While this tool produces drafts of comparable quality to human-authored biomedical ICD versions, it does not replace the need for human oversight. The human editing process remains essential to ensure accuracy and context-specific adjustments. The primary value of this tool lies in its ability to enhance consistency and improve readability. By automating initial drafts, PIs can focus on refining rather than document drafting. Furthermore, additional evaluations and prompting modifications can provide a framework to deploy the tool for broader institutional adoption.

However, several considerations remain. First, optimizing content for KI sections is particularly challenging due to the absence of a gold standard to provide objective guidelines for accurate outputs. Limited guidelines may have introduced subjectivity in IRB SME raters’ (phase 1) assessments, further complicating this process. Thus, delivering accurate content from the AI tool requires a structured, multi-step prompting approach instead of single-shot instructions. A prompting event refers to one interaction where we ask the AI to extract, interpret, or summarize specific information. We guided the model through successive prompting events, first to identify relevant facts, then to evaluate context, and finally to format concise KI language. This mirrors human-like reasoning and in so doing seeks to improve contextual accuracy. Multi-step or chain-of-thought prompting has been shown to enhance both reasoning ability and factual correctness compared to one-shot methods [Reference Wei, Wang and Schuurmans9]. By deconstructing the task we reduce “hallucinations” and produce more reliable KI content than would be achievable with one-shot prompting alone.

Beyond content generation, the evaluation of AI-generated KI sections by IRB reviewers may also introduce variability in assessment outcomes. While the meta-language template allocates fixed space to each required KI element, which implicitly limits total length, we did not conduct a formal word-count comparison. Systematically measuring length variability represents an operationally useful avenue for future work. For example, we noted some IRB reviewers indicated factual inaccuracies in human-authored KI sections previously approved by the IRB, particularly regarding certain study-related risks. Given IRBs’ critical role in evaluating ICDs and their associated study protocols, prior research has noted this phenomenon and identified inconsistencies in IRB decisions, raising concerns about inter-rater reliability [Reference Resnik10]. A 2011 systematic review of 43 empirical studies that evaluated IRBs found that IRBs frequently vary in their interpretation of federal regulations, the time required for study reviews, and final determinations [Reference Abbott and Grady11]. These findings highlight the need for standardized KI guidelines along with objective evaluation criteria to improve consistency in both AI-generated KI content and IRB assessments, ultimately strengthening the reliability and ethical oversight of the informed consent process.

Secondly, when evaluators across the multiple phases of our study assessed the overall quality and organization of AI-generated KI sections compared to those authored by PIs, notable differences emerged in areas where AI outperformed or underperformed human efforts. For instance, in the IRB SME evaluations (phase 1), the AI tool’s ability to differentiate between standard-of-care and research procedures and to appropriately weight information improved gradually and required several iterations of prompt refinement (Figure 2). A particularly challenging aspect was accurately identifying and describing potential risks. Initially, the AI-generated KI sections tended toward exhaustive lists, including both minor inconveniences (e.g., difficulty finding parking) and severe risks (e.g., death, disfigurement). After prompting adjustments to highlight only the “most important risks that are introduced or enhanced because of participation in [the] research study,” we encountered a significant issue. It proved difficult for the AI model to consistently distinguish between standard-of-care risks (i.e., risks inherent in standard treatments independent of the study) and research-specific risks (i.e., those directly attributable to study participation). For example, bruising at an injection site would be clearly a research risk in a study testing IV-administered vitamin B12 for Seasonal Affective Disorder, since standard treatments (light therapy, psychotherapy, antidepressants) do not involve injections. Conversely, bruising from an IV in a chemotherapy study for pancreatic cancer would typically be classified as a standard-of-care risk rather than research-specific, as chemotherapy delivered via IV is a routine treatment. The observed discrepancy between accuracy in describing potential benefits and risks thus reflects this complexity in risk characterization rather than an inherent bias introduced by the model’s fine-tuning. Addressing this complexity will require ongoing iterative prompt refinement and the incorporation of specialist knowledge (e.g., guidelines articles) into the model’s responses via Retrieval Augmented Generation.

A third and critical consideration is the successful implementation, deployment, and ongoing maintenance of the prototype AI tool within a reliable and scalable infrastructure. Beyond system architecture, factors such as user accessibility, integration with existing IRB workflows, data security and compliance, ongoing technical support, and institutional governance strongly influence whether such a tool can be sustained and adopted. Scaling from research testing to full institutional adoption requires a comprehensive infrastructure strategy. This includes: (1) defining integration pathways with existing IT systems, (2) ensuring data security compliance, and (3) optimizing performance for real-world use cases. Overcoming this translational gap from prototype to production remains a significant challenge in academic settings. The Appendix includes more detail regarding the technology stack we used for this project and a link to the full code repository.

Our current challenge lies in the centralization of academic IT services. Though this has enabled institutions to enhance efficiency by externalizing technical requirements to third-party vendors and reducing procurement costs, this transition has also led to a shift in IT support [Reference Brown12]. Organizations are deprioritizing requirements in staff and resources to maintain internally developed enterprise solutions [Reference Brown12]. As a result, there is often an incentive to wait for vendor-supplied solutions rather than invest effort for in-house development. However, if the potential market for a tool is small and/or specialized expertise poses a barrier to uptake, as is the case of regulatory functions like the IRB, commercial solutions may never be developed. This creates a barrier where innovations, such as AI-assisted informed consent tools, struggle to gain institutional adoption despite demonstrated efficacy. To overcome this, strategic partnerships with research institutions, funding agencies, and regulatory bodies may be necessary to ensure sustained development and institutional support. Additionally, identifying a scalable deployment model, whether through direct institutional investment, collaboration with IT service providers, or open-source community engagement, will be key to ensuring the tool’s long-term viability.

A final consideration is the overall, perceived benefits of AI-driven tools among the different stakeholders. According to the PI survey, over 87% of respondents expressed a likelihood (scores of 4 or 5, indicating “likely” or “very likely”) of using the AI tool to draft their KI sections in the future (Figure 3). In contrast, the IRB reviewer survey revealed a more reserved and varied perspective. These differences underscore the need for building trust through ongoing education and demonstrations of the tool’s efficacy. More importantly, this may reflect each stakeholder’s distinct role in the creation and approval of the KI section. For PIs, using the AI tool to create an initial draft of a KI section may save time and, with a well-functioning tool, only require minor editing. However, for the IRB, reviewing an AI-generated KI section requires the same manual process to assess regulatory compliance and accuracy as reviewing a human-authored KI section. A time study could assess whether AI-generated KI sections expedite the review process between PIs and the IRB and determine if these tools have an impact on administrative burden such as decreasing the number of IRB imposed contingencies. Additionally, developing a companion AI tool to generate a checklist to support the IRB’s review may assist in systematically identifying key compliance issues while preserving their oversight role. By addressing these concerns and demonstrating how AI-generated KI sections can reduce both drafting and review time, this approach could facilitate the integration of more AI tools into specific aspects of informed consent development and review.

Conclusion

Further refinement of the AI tool is essential, particularly in accurately assessing study-related risks and distinguishing between standard of care and research procedures. Exposure to a broader range of IRB-approved ICDs can enhance the tool’s understanding of IRB-acceptable content, enabling it to generate draft KI sections that better align with regulatory expectations, ethical standards, while promoting greater acceptability. Parallel to in-depth training, intentional messaging is required to address concerns about AI implementation replacing human expertise. One reviewer’s feedback encapsulates this hesitation, stating, “Perhaps it is my distrust or skepticism with AI since it’s new and I’ve not used it in my regular work, but I would want to ensure that the regulatory document has all requirements in there and not blindly trust AI to generate.” These concerns bring to forefront the importance of positioning the tool as an aid that enhances human oversight. For PIs, this tool provides an immediate starting point for drafting KI sections in ICDs, significantly reducing the effort required for initial documentation while maintaining high-quality drafts. For IRB reviewers, the tool has the potential to improve consistency and clarity in KI sections, thus streamlining the review process. For participants, this tool can enhance study comprehension for better participant recruitment. Therefore, by positioning AI as an assistive technology that supports, rather than supplants human judgment, PIs and IRB professionals can confidently embrace its benefits while upholding the highest standards of accountability.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2025.10222.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research (MICHR). We thank Elias Samuels and the MICHR biostatistics team for their assistance with evaluation efforts. Special thanks go to Autumn Toney, Senior Data Research Analyst at Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology, for her invaluable contribution as a consultant in developing the Prototype AI Key Information Generator. We also appreciate the outstanding administrative support provided by Ellen Han and the entire team at the University of Michigan’s Office of the Vice President for Research.

Author contributions

Shahana Chumki: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing; Caleb Smith: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing-review & editing; Terri Ridenour: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing; Kristi Hottenstein: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing; Lana Gevorkyan: Investigation, Methodology, Writing-review & editing; Corey Zolondek: Investigation, Methodology, Writing-review & editing; Joshua Fedewa: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing-review & editing; Judith Birk: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing-review & editing.

Funding statement

MICHR Grant Number UM1TR004404.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standard

This study was deemed exempt by the University of Michigan Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board, January 24, 2024, HUM00236511.

Other disclosures

Generative AI was intrinsic to the development and implementation of the tool. We have documented its use where relevant (See Supplemental Material 1 for the GitHub link to the AI tool code). Analysis for Figure 2 utilized ChatGPT-4o (See Supplemental Material 4 for complete process and prompt).

Appendix

Implementation Details:

Backend: Python (FastAPI)

Front-end: Next.js (React framework)

Cloud Deployment: Vercel

Code Repository: https://github.com/jcalebsmith/michr-ki-summary.