4.1 Introduction

When commenting on the consequences of a possible United Kingdom (UK) accession to the European Economic Community (EEC), the eminent British legal specialist Otto Kahn Freund pointed out the risk of a dual standard regarding migration. One of the founding figures of German labour law who fled to the UK after 1933, Kahn Freund (1900–1979) had become a professor at the London School of Economics and a prominent labour and social security law specialist – serving as president of the International Association for Labor Law and Social Security from 1960 to 1966. At a 1962 conference discussing the first negotiations of the UK accession to the EEC, Kahn Freund made it clear that from a legal perspective the British accession to the EEC might tarnish ‘Britain’s good name’ by establishing a racially based migratory regime between European and extra-European migration.Footnote 1 This was, to his eyes, ‘the most serious issue the European freedom of movement poses’. This issue was not only raised during the UK accession discussions. In the 1950s, most European countries were still empires or had only recently ceased to be empires.Footnote 2 At this nascent time of European integration, the freedom of movement of workers proclaimed by the Treaty of Rome 1957 and its consequences on the workers from the colonies had already been the cause of agitation among policymakers and legal specialists alike. It was as if two competing (imperial and European) communities were raising questions of principles on the best ways to define freedom of movement, one of the core tenants of any transnational community.

This conundrum was part of a debate that caused a great deal of tension during the negotiations leading up to the Treaty of Rome, and which saw several U-turns between the 1950s and the 1970s. These U-turns were not solely European, that is to say refracted in EEC and later EC law; the national policies of the former colonial powers, which progressively ceased to consider themselves global communities, played a key role in the transformation of the migratory regimes emerging from European integration.Footnote 3 These debates were carried over (and transfigured) into EEC/EC law, paving the way towards a double standard in personal mobility and to a racialized European border: a liberal migratory regime within Europe corresponded to a less liberal one between Europe and the postcolonial countries. This chapter aims to shed light on this dual migratory regime and on how it came about.

Part IV of the Treaty of Rome establishing the EEC stated that the freedom of movement of workers would – at some point – be granted to the colonies rebranded, to use the coded colonial prose of the EEC treaty, as ‘overseas countries and territories’.Footnote 4 Article 135 EEC states: ‘Subject to the provisions relating to public health, public safety and public order, the freedom of movement in Member States of workers from the countries and territories, and in the countries and territories of workers from Member States shall be governed by subsequent conventions which shall require unanimous agreement of Member States’.Footnote 5

From a contemporary perspective, the freedom of movement of workers incorporated more than the simple right to access EEC territory. Article 51 EEC of the Treaty of Rome stated a range of provisions granting worker access to welfare and social security rights. Without social security provisions, the freedom of movement would have been mere formulae. These provisions show that the geographical scope of the EEC was by no way restricted to the European ‘mainland’ countries. The Common Market was perceived to be a new means of continuing European colonial domination: in the words of the Ghanaian and Pan-Africanist leader Kwame Nkrumah, the concept of ‘Eurafrique [was] forged in the framework of the negotiations for the Common Market’.Footnote 6 The focus of most research on Eurafrica thus far has been its economic and commercial dimensions,Footnote 7 together with the developmental ideology that legitimized the continued entanglement of the two continents.Footnote 8 Less attention has been paid to its human dimension. As some recent pioneer research on the metamorphosis of the Algerian membership to the EEC have demonstrated, the human dimension cannot, however, be overlooked.Footnote 9 In looking at the ways the EEC framed labour migrations and anchored the European project to the Eurafrican imaginary, this chapter contributes to the ongoing questioning of ‘Euro-whiteness’ and the drawing of the European frontier, resulting in racialized populations being excluded from the free movement provisions.Footnote 10

The issue of migration goes beyond the formal right to immigrate to include social rights, rights that the EEC law has guaranteed to EEC migrant workers. Indeed, the EEC treaty provisions regarding the freedom of movement encompassed social security rights as well. Under these provisions workers are guaranteed social security rights (the right to pensions, to unemployment benefits, to health insurance etc.) when they leave their employment country; the right to cross borders would mean little if workers lost their social rights by doing so. As early as 1958, European regulations ensured that social benefits (for instance, family allowances) be paid ‘beyond borders’ and that the ‘equal treatment’ between nationals and foreigners be secured in this domain.Footnote 11 In the post-Second World War era, equality of treatment and the non-discrimination principle came to be core tenets of international law. European law had hence to confront the (post-)imperial reality of most of the EEC Member States and to forge a (defensible) coherence between rights granted to European migrant workers and those granted to (post-)imperial workers. Taking the example of the pension for retired workers, should German citizens having to flee Central European countries to Germany in 1945 be treated better than Italians in the same situation? Should a Belgian citizen be treated better than a French one when both had worked in the Belgian colonies? Should racialized workers from the French Community,Footnote 12 and later from the French and British (former) colonies, enjoy freedom of movement on the EEC territories as ‘European’ citizens? These issues are of major importance if one is to understand how EEC/EC law has contributed to global inequalities, welfare institutions being crucial in redistributing wealth and exacerbating inequalities between racialized and European workers.Footnote 13

In order to explore these issues, this chapter focusses on a community of ‘artisans of legal techniques’: officials in labour ministries of the EEC/EC countries who write the international standards regarding social security law.Footnote 14 Some of these ‘artisans of legal techniques’ had had colonial experience. From the 1950s to the 1970s, social security bureaucrats in European countries with a sense of activism wrote international rules for circulation and social security, be it in Europe or in the rest of the world. In the realm of the welfare state and international policymaking, they pushed through bilateral and multilateral agreements as well as corresponding regulations.Footnote 15 They constructed a ‘legal regime’ – that is to say, the patterns structuring the relations between separate legal authorities – regarding the social rights attached to the freedom of movement of workers or more generally of migrant workers and their families.Footnote 16 Several questions arise. How did this public policy network discuss the coexistence of these two forms of communities? How was the link between the new EEC and the postcolonial communities established? How was a racialized border, severing the human ties between Europe and Africa, established?

This chapter is divided into two parts. First, it shows that from the 1950s to the 1970s two legal regimes relating to migration and social rights coexisted on a (formally) equal footing, the European and the postcolonial. Second, this chapter shows how these two legal regimes were hierarchized in the 1970s, and contributed to racializing the European border.

4.2 Competing Communities (1950s–1970s)

The sets of regulations regarding labour mobility indicate that two systems of preference coexisted: a European (EEC) system, and a post-imperial one. The latter, devoted to maintaining the extractive colonial economy, structured a relatively liberal migratory regime between the European countries and their former colonies in order to maintain transnational polities. The 1960s saw the emergence of a new global order following the ‘fall of the European international law’,Footnote 17 in which new standards promoted by the UN institutions, such as the legal imperative of ‘non-discrimination’, rendered difficult the use of explicit racial reservations within European law and administrative practices.

4.2.1 Bargaining the Imperial Privilege.

At the time the Treaty of Rome and its implementation were being negotiated, the colonial powers were eager to share the burden of developmental aid, but much less eager to grant EEC workers access to their colonial territories.Footnote 18 The administrations of the colonial powers feared uncontrolled southward migration would jeopardize their domination and reallocate colonial benefits. They developed a system within which the influx of southward migration from Europe would not unsettle the precarious colonial authority.

In the European political imaginary until the end of the 1960s, sub-Saharan Africa was a place of settlement for Europeans. Europe was considered the overcrowded continent, not Africa – with the exception of North Africa. The role of this exception should not be overlooked: some EEC Member States were reluctant to allow Algerian immigration but overcame this reluctance when they agreed to incorporate Algeria in the framework of the 1961 EEC Regulation on the Freedom of Movement.Footnote 19 Nevertheless, Africa south of the Sahara was a marginal contributor to migration to Europe. Taking the example of France, in the mid 1960s, the decade when most ‘Black African’ immigrants arrived in the country, the actual numbers were, in fact, negligible: in 1964, 73,000 sub-Saharan Africans were living in France, 11,000 of whom were students.Footnote 20 In contrast, White immigration in Africa was important. Large numbers of British immigrants had settled in their old colonial domain: in the 1960s numbering 50,000 in Kenya and 230,000 in Rhodesia, today’s Zimbabwe (to say nothing of South Africa). While the French population in France’s former colonies in sub-Saharan Africa was far smaller, it was nevertheless considerable. In 1956, nearly 90,000 ‘Europeans’ (the French administrative word meaning ‘White’, most of them being from mainland France) were part of the colonial economy and administration in French West Africa.Footnote 21 Decolonization did not put an end to this White presence. General data on this topic is lacking: as Abou Bamba notes, scholars seem to have ignored (and misnamed as ‘expatriates’) White migrants in the Global South.Footnote 22 Abou Bamba deplores this shortcoming of the literature, underlining particularly the lack of data on aid workers (‘coopérants’ in French). In 1965, nearly 10,000 ‘coopérants’ were living in sub-Saharan Africa.Footnote 23 They were not, however, the only category of Europeans (mostly French) working and living in Africa. By the mid 1970s, the French population in Côte d’Ivoire alone amounted to 40,000 (compared to 11,000 in 1960). Other studies show similar trends. In 1963, 50,000 French citizens were estimated to have been living in Dakar, the largest town of Senegal (15 per cent of its population) – even if this number was perhaps exaggerated.Footnote 24 By 1967, 3,600 French citizens had settled in Gabon, a country rich in natural resources; 1,200 living in its major port, Port-Gentil, a town of 23,000 inhabitants.Footnote 25 In 1959, more than 115,000 Europeans (most of them Belgian nationals) were living in Congo-Leopoldville.Footnote 26

At the time of the negotiations on the Treaty of Rome, scientific institutions close to colonial administrations not surprisingly stressed the risk that European integration could lead to uncontrolled southward European migration. The French Academy for Colonial Science, a scientific institution attached to the Ministry for Overseas Territories, was vocal about the threat that European immigration would pose to the overseas territories, pointing out that this view was shared by the African representatives in the French institutions.Footnote 27 They feared further that the Eurafrican community would mainly consist of immigrants from ‘overpopulated nations’ such as Germany, the Netherlands and Italy.Footnote 28 Other colonial institutions shared this worry. In the mid 1950s, a report by the Belgian ‘Congrès colonial’ (colonial congress) clearly stated that European integration would mean a demographical risk of White migration to Congo and to Rwanda-Urundi:

Two observations are immediately obvious:

Italy as well as Germany and Holland would be particularly desirous of sending their emigrants overseas because of the constant demographic pressure that these countries are experiencing within their borders;

the perception of the dangers of immigration and massive European colonization by foreign elements are serious for the development and future of the indigenous populations, as well as for the safeguarding of their national sovereignty.Footnote 29

The French delegation’s position was that the ‘free movement of workers’ should be treated as a separate issue and postponed to later negotiations. Belgian Minister for Colonies (1947–1950) and for Foreign Affairs (1958–1961) Pierre Wigny (who took part in the EEC negotiations) also feared European immigration to Black Africa. He was hostile to any situation where Belgium could lose its control over European emigration to Africa. It was concerning, he had already written in a 1949 report on the European Political Community, that Italy, Germany and the Netherlands might try to ‘flood the Belgian Congo with their migrants’. A complete integration of the French and Belgian overseas territories within the Common Market would only be possible when these territories reached a level of development deemed sufficient – the ‘lack of development’ being an argument commonly used to justify a dual standard in international law.Footnote 30 Then, as the minister of the overseas Gaston Defferre wrote, ‘a Common Market including European countries and Overseas Territories would be established’. In short, the design of this ‘Eurafrican Common Market’ had to consider the specificities of the ‘underdeveloped’ world:

One of the principles of the Common Market is the free movement of persons. Given the overpopulation and the high underemployment rate in some European countries such as Italy, we may expect that this free movement would provoke rather important movements of population to the Overseas Territories. For reasons less economic than human, it is necessary to prevent an excessive flux which would certainly give rise to negative psychological reactions. This would harm the evolution of the indigenous institutions and cause riots opposing Europeans and Africans, as we have had many examples in North Africa. It is therefore impossible to establish free movement of men between Africa and Europe as a principle without any precaution. Besides, I think that our European partners will themselves question this with the desire to prevent an inflow of the Algerian populations to their territories.Footnote 31

Controlling which European populations would benefit from this extractive economy was another reason why Article 135 EEC of the Treaty of Rome postponed the Eurafrican freedom of movement to later discussions. To French and Belgian negotiators during the preparation of the EEC treaty, allowing European immigration to Africa would have unsettled the political and economic situations. A Eurafrican freedom of movement would have multiplied ‘low quality’ White immigration to the Black continent causing social problems and general dissatisfaction. It would have counterbalanced the efforts made by the colonial powers to ‘upgrade’ White immigration by privileging the highly skilled technicians and aid workers the African governments were competing to recruit.Footnote 32 On the other hand, the presence of Europeans in Africa and the participation of the continent in the Eurafrican community was necessary. When defining the position of the Ministry for Overseas Territories in the framework of the negotiations leading to the Treaty of Rome, Gaston Defferre stated that the overseas territories had to be part of the Common Market, which he rebranded the ‘Eurafrican Common Market’.Footnote 33 If not, he was afraid the economic ties of France and its colonies would be severed, and France would rapidly lose political ground in Africa. European integration should therefore be delayed in order to ensure that the French maintained the upper hand in the region, as the presence of Europeans in Africa was (and still is) essential to the colonial extractive economy. The imperial and postcolonial community, characterized by a relatively liberal circulatory regime, guaranteed the economic structure arising from colonization. As Megan Brown shows in her book on Algeria, it took political decisions by the Algerian leadership to loosen the grasp of French industrial players over the economy in this country and to open it up to industries from other EEC countries.Footnote 34

4.2.2 Preserving Postcolonial Communities Through Eec Law.

The relations between the mainland countries and their former colonies were not severed by decolonization: former colonies might be independent, but that did not mean that their European past was left behind. EEC law responded to this perpetuation of the relationship between colonizers and colonized by treating colonial migration as a legitimate exception to the migratory ‘European preference’ EEC law strove to establish.

Former imperial powers perpetuated the human interdependencies with their former colonies. Nadine El-Enany shows how the 1948 British Nationality Act was about ‘mysticism’: the theoretical rights of Commonwealth citizens, subsumed in the same ‘nationality’, to travel to Britain was ‘a magic trick of sorts, a legal sleight of hand that would conjure a British imperial polity anew’.Footnote 35 This ‘mystical’, all-encompassing Nationality Act did not prevent Britain from bureaucratically making it more difficult for racialized Commonwealth citizens to access its territory without shutting the door to White settlers. However, it did not formally erase the imperial polity. France chose another path to maintain its imperial polity. The discussions on the nationality code of the French Community (the name given to the colonial domain by the Constitution of the Fifth French Republic adopted in 1958) were indeed just at their beginning in 1960 when the French Community was dissolved.Footnote 36 Nevertheless, with the dissolution of the French Community in 1960, the newly independent countries concluded a range of agreements with France granting, on the basis of reciprocity, freedom of movement, equality of treatment and de-territorialized rights to social security. Until the middle of the 1970s, French diplomacy sought to maintain a transnational community between France and its former African colonies.Footnote 37 French diplomats considered the freedom of movement of persons of crucial importance. A memorandum issued in 1963 recalled the paramount importance of the free circulation of persons within the former French Community as a legal ‘principle’ affirmed in a multilateral agreement concluded on 22 June 1960 with six African states. It reads: ‘[E]ach national from a member state of the Community can freely enter the territory of another one, journey in it or settle down as resident in the place of his/her choice.’Footnote 38 Where such agreements were not reached, the old liberal imperial migratory regime stood tacitly in place. Some former colonies (Côte d’Ivoire, Mali and Mauritania) did not enjoy this legal protection, but were informally included in the same mechanism granting French nationals a privileged but non-formal access to their territories, the memorandum continued.Footnote 39

This perpetuation of the defunct imperial territoriality appears in the web of treaties that the colonial powers concluded with their former colonies in the domain of social security. The issues of free migration and access to social security were, however, posed with the same ‘legal techniques’ in the EEC and postcolonial communities. At a 1963 conference on ‘Labour law and the Common Market’, focussing on the possible consequences of a British accession to the EEC, the soon-to-be Oxford professor Otto Kahn Freund stressed that the ‘freedom of migration’ promoted by the EEC would be ‘illusory if not coupled with legal and factual equality’ (he called this a ‘positive equality’, distinct from the removal of barriers). He made social insurance the first item where equality mattered and concluded by describing the European social security coordination: ‘Nothing revolutionary in this country (Great Britain). We have a network of such conventions with Commonwealth and European countries.’Footnote 40 As a matter of fact, from 1947 to the end of the 1970s, Britain had developed a social security agreements network covering twenty of its former colonies, and the other colonial powers developed the same extensive network of agreements. When the country acceded to the EC in 1973, parts of this network were already in place, especially with the countries of the old Commonwealth and the Caribbean.

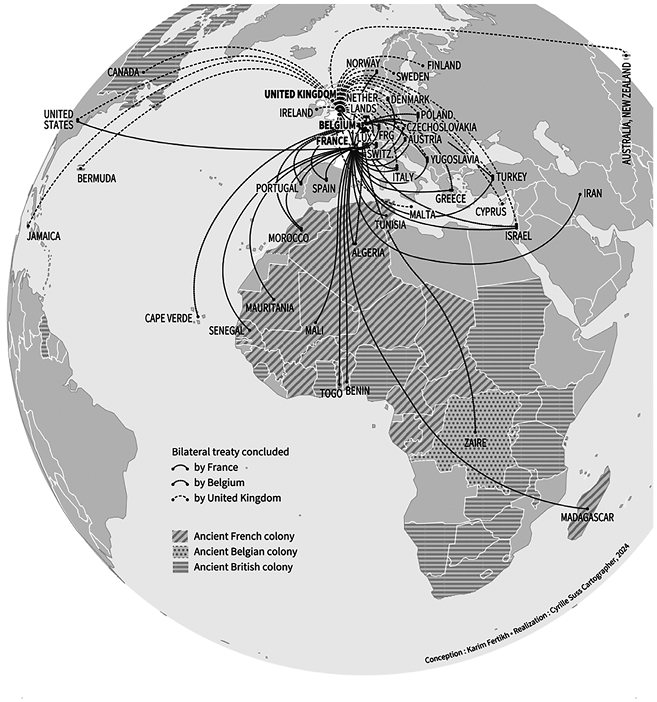

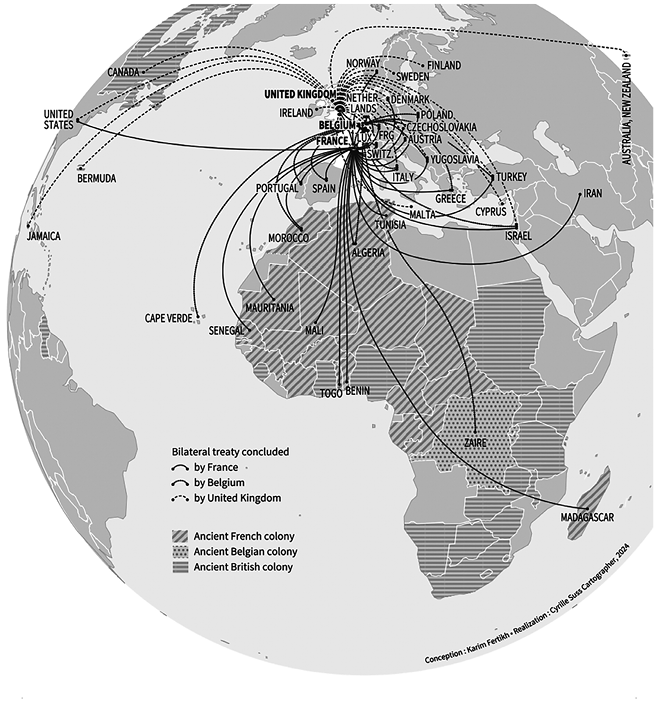

The networks of agreements on social security rights illuminate the maintenance of imperial polities (see Map 4.1). These treaties served the interests of European nationals at the same time as they created a burden for the social security of their former colonies. They could represent a non-negligible part of the formal sector (the informal sector being de facto excluded from social protection). By the mid 1960s, 20 per cent of the child allowances paid in Gabon, a former French colony, benefited foreigners, with half of those French nationals.Footnote 41 Similarly, in 1977, with an eye to maintaining imperial polities, UK officials pushed for an agreement with Iran, a country where Britain had had influence since the beginning of the twentieth century. The social security officials underlined that the 200 British companies in Iran employed 5,000 British people, compared to the 300 to 400 Iranians working in Britain. Nevertheless, as self-serving as these agreements may have been, they were written in a formally egalitarian language, and did not differ much from the EEC/EC agreements themselves.

Map 4.1 Network of social security regulations in 1974: postcolonial polities.

Map 4.1Long description

Global map illustrating the network of social security regulations in 1974, highlighting postcolonial polities. The map shows bilateral treaties concluded by France, Belgium, and the United Kingdom, with lines connecting various countries. Ancient French, Belgian, and British colonies are marked with distinct patterns. Key regions include Europe, Africa, and parts of Asia and the Americas.

These postcolonial polities were a given that EEC law had to deal with. EEC law sought to preserve the liberal migratory regime between former colonial powers and newly independent countries. Under the pressure of French civil servants, the EEC forged a system where the EEC freedom of movement (and the correlative ‘European preference’ in migration) did not jeopardize the defunct imperial communities. A pinnacle of the Common Market, the freedom of movement of workers provision, aimed at rationally administering labour mobilities, authorized mobilities of unemployed workers from EEC territories without the resources to employ them to territories lacking workforce. This system was called ‘international compensation’ as it sought the rational allocation of workforce on an international level.Footnote 42 In this system, the national bureaucracies agreed on a ‘European preference’. Migration from an EEC country should be privileged if nationals were unable to satisfy the existing job offers, meaning that vacant job offers had to be first proposed to EEC recruitment offices. At the ‘European Coordination Bureau for Labour Compensation’ (in the General Directorate ‘Social Affairs’ of the EEC Commission), the EEC officials seemed, however, to have never been truly satisfied with this ‘mechanism’ of ‘compensation’. The first annual report of the European Bureau of Coordination in 1963 lamented that European workers had not truly been given any such priority.Footnote 43

The EEC freedom of movement regulations did, in fact, include a reservation: migration from within Europe could not supersede migration from former colonies. In a 1960 memorandum, the Juridical Service of the EEC Commission issued a statement regarding the ‘non-European countries and territories having special relations with Belgium, France, Italy and the Netherlands’ and the consequences of their newly acquired independence.Footnote 44 This document pushed forward the notion of ‘special relations’: the Juridical Service identified ‘political dependence’ and ‘lack of self-determination’ as the basis for the continued ‘association’ of these territories with the EEC. Given the uncertain situation of the independent countries regarding the existing set of international treaties, the legal experts of the EEC used the ‘vague’ notion of ‘special relations’ to grant these former colonies special status under EEC law (whereas the 1961 regulation applied only to Algeria). The two regulations of 1961 and 1968 relating to freedom of movement took the notion of ‘special relations’ into consideration in Article 42(3) and Article 42(3) respectively: the European freedom of movement should, according to the regulations, not jeopardize the obligation of European countries towards countries with which they have or have had ‘special relations’.Footnote 45 Legally speaking, the regulations took into account ‘existing or previously existing institutional bonds’ and stated that nothing should endanger the obligations that these bonds had generated in regard to freedom of movement. This legal concept, ‘special relations’, expressed these relations between Member States and their former European colonies, and built a legal architecture combining both postcolonial and European communities.

4.2.3 Maintaining the Unity of International Law.

During the first decade of the EEC, EEC law limited the legal inequalities towards (former) colonies in its dispositions related to freedom of movement. It did so by the effect of the non-discrimination principle, used as an argument in negotiations. At the time, the contemporaries contemplated with difficulty a dual standard regarding freedom of movement and social security.

EEC law was put under pressure by the pervasive international concept of non-discrimination. In the case of Algeria (the only country where freedom of movement applied as an effect of the 1961 regulation), Megan Brown explained the sinuous positions taken by the French authorities in the negotiations for the Treaty of Rome.Footnote 46 One of the most detailed position papers preparing the 1961 regulation stressed the discriminatory character of excluding Algerian workers from the regulation. This paper by the secretary for economic affairs at the Algiers Governorate, Salah Bouakouir, sheds light on the prevailing conception. A student of the École Polytechnique, Bouakouir is representative of the indigenous elite educated in the French system and was a member of the Académie des sciences coloniales (Academy of Colonial Sciences), the most important scientific institution of colonial France. He was probably at the time feeding secret intelligence to the Front de libération nationale (National Liberation Front), which was fighting the war in Algeria. In 1961, Bouakouir drowned in the Mediterranean Sea. Some say that his death was the result of a targeted assassination by the French military. In his 1959 paper designed to prepare the negotiations on the first regulation on the free movement of workers, he stressed that the freedom of movement of Algerians could not be denied: Algerians, like the other inhabitants of the overseas Departments, were considered French, and there was no specific information on their documents that could be used to sort them. He insisted that any such denial could only be seen as ‘racial discrimination’. But, given that this claim could be reversed and could open Algeria to European migrants, the Algerian governor would not oppose a separate negotiation. The Algerian administration would especially welcome trained workers and technicians, that is: highly skilled workers.

The debates about the EEC social security coordination illuminate the single standard of social security international law, and the reluctance to establish an openly hierarchized legal standard which would make EEC workers better off than racialized postcolonial workers. One of the fiercest struggles undertaken by the French social security officials at the time was to prevent the EEC system from becoming explicitly more generous than the agreements existing with the other countries, and especially France’s former colonies. The French agreements (formally) granted the workers from France’s former colonies the same kind of social security guarantees enjoyed by the EEC workers – that is, benefits adjusted to the local standard of living. In 1966, France was paying family allowances to 221,892 children living in Algeria whose fathers were working in France. By 1973, 689,700 children were benefiting from French allowances abroad, most of them in the former colonies.Footnote 47 In most of these countries, allowances were paid at the rate of the country where the children resided or through a complex system of reimbursement; in other words, at a lower rate than children in France. This situation was inherited from the colonial era. When they negotiated the European Convention on the Social Security of Migrant Workers (which then became EEC Regulations 3 and 4),Footnote 48 the French negotiators imposed the same mechanism (payment at the rate of the country of residence). In a file dedicated to the international relations regarding family allowances, the French social security officials fiercely defended this uniform ‘doctrine’ (as they called it) of allowances for non-resident children being inferior to those for residents. This system was seen as ‘discriminatory by other EEC states and international organizations’, and the Commission demanded that not only the Member States should enjoy full equality but overseas territories as well.Footnote 49 For the French Ministry of Social Affairs, such an attack on its doctrine was unacceptable. Its officials therefore took a hard line in the EEC negotiations on social security. They argued that aligning the allowances paid abroad with the French rate would oblige them to revise every existing agreement, and especially the agreements with France’s former colonies. The ministry established that the 689,700 children receiving family allowances abroad cost a global sum of 297 million francs in 1973 (less than 10 per cent of this total went to EC families). This represented 431 francs per child per annum, far less than what a child in France would have received. In this matter, one of the main arguments of the French Department for Social Security of the ministry was the ‘formidable risk of a contagious effect’:Footnote 50 it saw all of these agreements as inspired by a single set of principles so that better treatment of European workers from EC countries would have a domino effect on a whole series of agreements.Footnote 51 The employees of the ministry argued that the different agreements, although diverse in their shaping, derived from a single philosophy adjusting the allowances to the local standard of living: ‘in spite of the apparent diversity, there is a unity of view in the positions taken by France in its multilateral and bilateral agreements’ in social security, stated an internal report to the minister of social affairs.

In the 1960s and 1970s during the accession negotiations, the British welfare elite recognized the potentially discriminatory effects of EC law on the citizens of the Commonwealth countries as well. They feared the choice for Europe could be a choice against the Commonwealth and its racialized immigrants. The British specialists from the Department for Health and Social Security (DHSS) contemplated anxiously the dual standard arising from the EC social security regulations. Britain had already concluded twenty social security agreements with Commonwealth countries offering a lower protection than the protection provided by the EC regulations. In a note to A. Patterson, the head of the DHSS who had led numerous international negotiations on social security since the 1940s, another civil servant cautioned him about the danger of the discriminatory consequences of the EC law on the Commonwealth citizens if the UK entered the EC. In a note of 23 June 1970, he underlined the costs of the regulations should the Irish Republic join the EC as well, and stated further:

The most delicate immediate repercussion might be the repercussion on our treatment of the immigrants from India, Pakistan and West Indies of our acceptance of the obligation to provide various measures of social support, including family allowances, for the dependants of nationals of members of the Community who have come here but left their families behind. It might seem odd to do this for Italians and Germans but not for coloured immigrants from the new Commonwealth countries … Pressure may be exerted on us by other Commonwealth countries concerned about the immigrant population here. If such pressure does arise, it is not hard to envisage the emotions which it would generate, or the difficulty of finding convincing arguments with which to fend it off. On the other hand, the cost of giving in to the pressure could well be relatively heavy and adverse to the balance of payments. While obviously the risk of having to face this dilemma is quite irrelevant to our negotiations with the Community, Ministers will recognize that potentially a decision to adhere to the Treaty of Rome could produce either some embarrassing situations or considerable extra costs in this indirect way.Footnote 52

The description of the problem pointed to a moral issue. The note picked out the two EC countries, Italy and Germany, against which the UK had waged the Second World War and underlined the discrimination (‘coloured immigrants’) at a time when South African Apartheid was the subject of general reprobation. The voices of the most renowned legal specialists joined those of the bureaucrats. Otto Kahn Freund, considered the founder of social law as an academic discipline in the UK, advocated the same coherence when negotiating Britain’s accession to the EC in the 1970s. For him, freedom of movement must not be allowed to drift into a double standard of White versus racialized migration:

To conclude, let me come to the most serious issue the European freedom of movement of workers poses. This issue may not exist for the other European countries to the same extent. At the moment, the situation is so: each member of the British Commonwealth can immigrate and can seek a job here without limitation. It does not matter if he comes from a still existing colony such as the West Indies islands or from an independent member of the Commonwealth such as India or Pakistan. A law proposal is currently being debated in Parliament which seeks to severely reduce this right. Is it then surprising that many protest against the growing complication of immigration from the overseas countries and the simultaneously growing facility of the immigration of Western workers? … If the door is now open for the Italian worker for instance, but closed for the coloured West-Indian worker from Jamaica or Barbados for whom it used to be open, this could be interpreted as the influence of a racial prejudice. And this is interpreted this way in the West Indian. What is at stake here is the good name of Great Britain on the issue of the struggle against racial prejudice. It would be terrifying should the British government give the impression that it has used the EEC accession as an opportunity to stop or limit the immigration of Black or dark-skinned British citizens. The Western EEC member states should keep in mind that the freedom of movement of workers in the Common Market has to cover the British citizens of colonial (for instance West-Indian) origins living in Great Britain if the country enters the EEC.Footnote 53

In the view of the postcolonial states, European and other international rules should follow similar paths so that the change in one set of rules did not affect the other one. In the 1970s, this situation changed drastically.

4.3 A Racialized European Border (1970s–1980s)

If racial discrimination was not considered an acceptable option any longer, how has the current racially differentiated migratory regime been established? Racialization has often taken side roads, avoiding the use of openly discriminatory legal techniques.Footnote 54 Nevertheless, in the 1970s, political pressures pushed the EC bureaucrats to endorse a dualization of the international standard. The debates surrounding the accession of the UK to the EC make it clear: the issue at hand was for the contemporaries to hierarchize the freedom of movement and the related social rights. This legal dualization racialized the EC border and elevated the European workers and citizens to privileged legal subjects. This hierarchy has prevented non-European people from accessing not only European territory but also the wealth accumulated on the continent by the exploitation of the colonies.

4.3.1 The Impossible Single Standard.

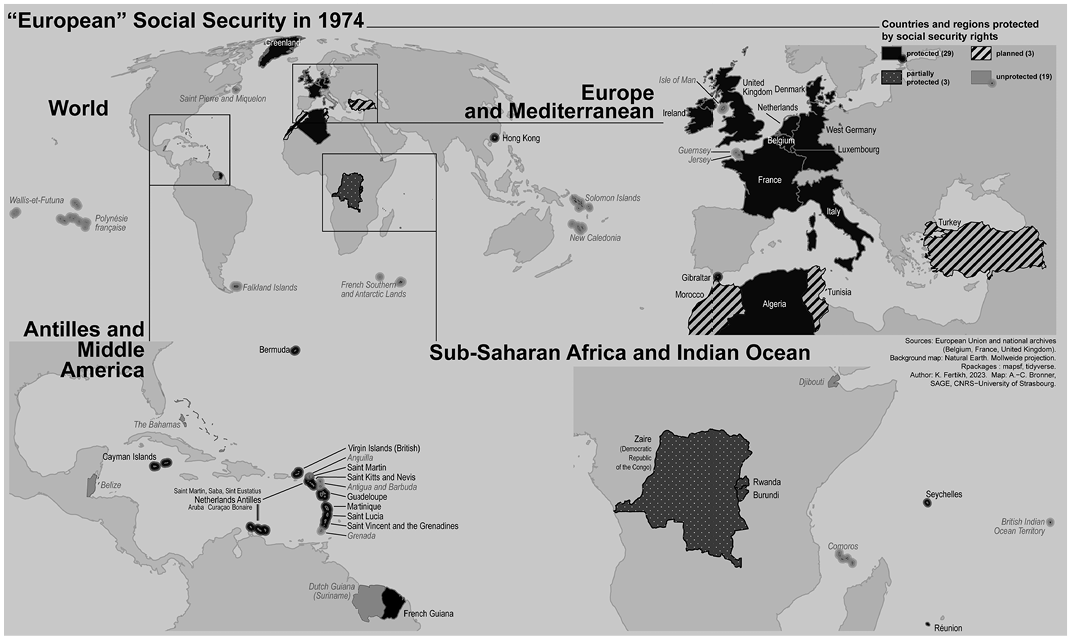

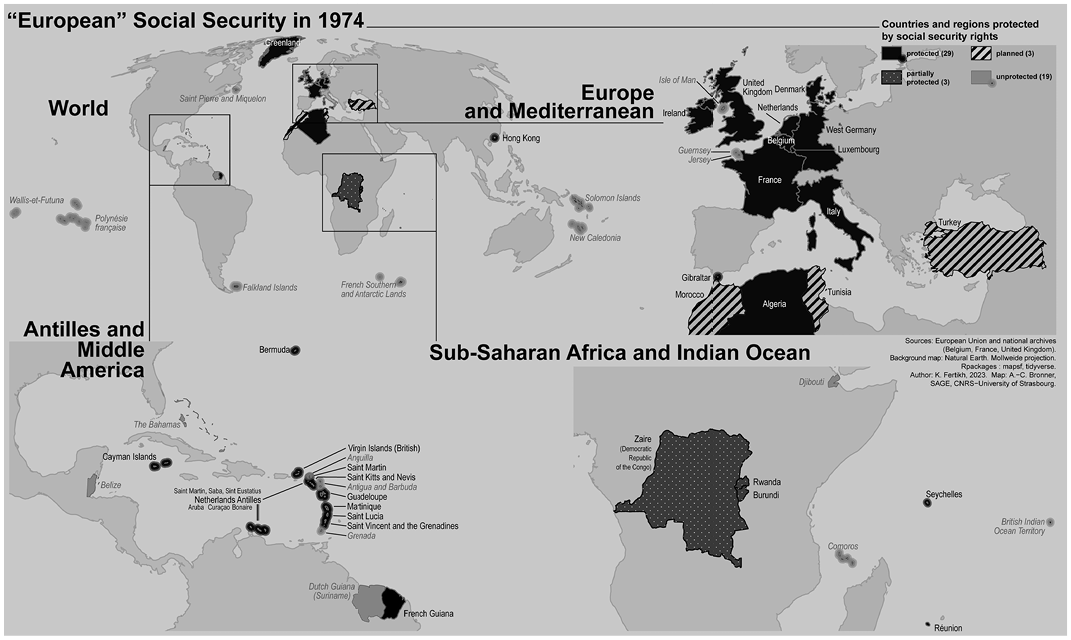

The idea of a single zone between Europe and its former colonies, guaranteeing the freedom of movement of workers, was not seen as utopian. In 1962, the EEC Commission proposed opening a general negotiation on the freedom of movement with the newly independent African countries.Footnote 55 By the mid 1970s, the EC regulations on social security had a global scope: they were European only in origin (Map 4.2).Footnote 56 Following Part IV of the Treaty of Rome, the French colonies of New Caledonia, Comoros, Djibouti, Saint Pierre et Miquelon and Polynesia were not (and still are not) included in the territory of the EC (now EU) law regarding the freedom of movement and social security. Nevertheless, under pressure from its partners, France extended the scope of the EC regulations to its ‘old colonies’ in the Caribbean and in the Indian Ocean as they were considered part of the French territory (as ‘départements’). By the mid 1970s, the social dimension of the EC with its social security regulations hence covered large parts of the world: from Algeria to Congo (for European workers), from Greenland to much of the Antilles Islands and to Hong Kong. It covered some of the dependent territories of the European countries and independent countries. Megan Brown has shown that Algeria has long ‘benefited’ from a status of quasi-Member State in regard to social security.Footnote 57

Map 4.2 ‘European’ social security in 1974.

Map 4.2Long description

Map illustrating the global distribution of ‘European’ social security rights in 1974. The map highlights regions in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia where EEC Social Security Regulations apply. Key areas include Western Europe with extensive coverage, parts of Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and specific regions in Africa and Asia. The map uses different shading and patterns to indicate the degree to which the EEC Social Security Regulations apply in each area.

The national authorities of the (former) colonial states were reluctant to expand the international European law to their former colonies with which they were linked by bilateral agreements. At the end of the 1960s, there was no clear notion of protecting the European border, and the revised Association Agreement with Turkey passed in 1970, for instance, entailed a freedom of movement for workers provision. When the EC came to negotiate Association Agreements with Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, the EC negotiators pushed the idea of extending to them the provisions regarding the freedom of movement and social security, noting that it would not change the current situation because of the network of agreements between them and most of the EC countries. For the EC countries, however, these Association Agreements posed a serious issue.

On the one hand, an EC memorandum discussed at length opposing the equality of treatment proposed for the workers from Turkey and the Maghreb, but eventually concluded that ‘it would be difficult to exclude the principle of the equality of treatment under national legislation. Equality of treatment is the first principle of the international instruments in social security.’Footnote 58 In the minutes on a meeting of the General Secretariat of the French government on this topic, it was noted: ‘All of these association agreements entailed nevertheless an equality of treatment clause, a formula that sunk into the grammar of international social law at the time. This provision will support some decisions of the European Court of Justice relating to social security or pension rights.’Footnote 59

On the other hand, these Association Agreements did not come to shape a Euro-Mediterranean space of free circulation. The clause on free mobility for Turkey adopted in 1970 was never implemented, and other countries did not even glimpse such a clause. Colonial history played its part here, especially regarding financial repercussions in the field of social security. The British DHSS feared for the situation of Gibraltar and the costs (estimated at 2.5 million pounds) that would result for the territory if an equal standard were given to the 4,000 Moroccans working on the Rock and representing 25 per cent of the working population. Here as well, the contagious effect was a potent argument for opposing a single standard. The DHSS feared ‘the political repercussions arising from any agreement on our part to export family allowances and the costs of medical treatment outside the territory of the Community’ as well: these agreements ‘would likely give rise to demands from Commonwealth countries that their immigrant workers here should receive privileges’ of the same kind as those granted to the Maghreb countries.Footnote 60 The DHSS expressed its opposition to the export of the most expensive benefits (pensions, benefits for industrial injuries).Footnote 61 The French department was worried by the costs that would result from an integration of Algeria into the European scheme, given that the EEC project planned to export the family allowances to the rate of the country of employment. As it did with the EEC, France paid lower-rate allowances organized through a system of reimbursement. A report dramatized the costs of a new doctrine: ‘For Algeria alone, the costs would rise from 132 million francs to 500.’ It would, furthermore, put the Algerians in the situation they were in before independence. For these reasons, the department deemed the proposition unacceptable.Footnote 62 It was joined in this by other countries, such as Germany and Denmark, which feared the extension of the social security regulations to the countries associated with the EC (North African countries and Turkey especially).Footnote 63

4.3.2 Drawing the Racial Line.

The role of national bureaucracies in the formal racialization of the European border was pivotal and contrasted. Whereas bureaucracies in charge of migration (Home Offices under their various denominations) politicized their action and supported an anti-immigration policy in the 1970s, the social bureaucracies kept an eye on international regulations but did not prevent European and other international laws from going their separate ways. Because the post-imperial international law was made of bilateral agreements lacking the resilience of EC law, it progressively lost ground in the 1970s without dramatic break.

Altogether, by the end of the 1960s, the presence of racialized workers on European soil came to pose a political problem – step by step, the European integration has established a legal dual racial standard, suppressing the (unequal) competition between the postcolonial and European communities. This dual standard did not, however, come into being without debate and technical difficulties. In the 1970s, the British accession to the EC hit a stumbling block over its 1948 Nationality Act, which at the time encompassed 850 million people. Nearly every Member State opposed a British position that would have threatened – so they thought – their countries with an uncontrollable immigration of Pakistani and Indian migrants.Footnote 64 The issue at stake was how to exclude holders of a British passport (in other words, British citizens) from the Commonwealth countries. In an extensive exchange defining how to recognize a British national (contained in a file entitled ‘Definition of “Nationals of the UK” under the Treaty of Accession’), Britain put in place a special ‘endorsement’ of its national passports, carrying the mention that its carrier is ‘a British national for EC purposes’, reading: ‘Holder has the right of abode in the United Kingdom.’Footnote 65

In this period when immigration came to represent a major political issue, EC law proved more resilient than other international regulations, giving birth to an increasingly explicit dual standard. In 1975, France deployed a policy aimed at reducing the immigrant population on its soil and introduced a system to decrease the generosity of its social security benefits for non-nationals.Footnote 66 The international standards resisted some of these demands formulated within the framework of the immigration policy. The French social security officials torpedoed a project to impose on non-EC foreigners a period of one year during which they would not be granted certain social security benefits, arguing that it would be contrary to international rules. Moreover, under pressure from both the International Labour Organization and the EC, they extended maternity allowances, which had been reserved for French nationals, to all residents. Altogether, such pressure gave rise to better protection for EC citizens. The first draft of a decree granting foreigners a subsidy to return to their home country targeted both postcolonial and European migrants, especially Italian workers. Italian workers, however, because they were protected by EC legislation, disappeared from its final version. Furthermore, in its 1986 Pinna ruling, the European Court of Justice (later Court of Justice of the European Union) compelled the French administration to ‘treat equally’ EC children living abroad and to grant them the same allowances as children residing on French soil.Footnote 67 With this ruling, the Court imposed a dual legal standard which provides postcolonial workers with a lower level of social protection than that enjoyed by European workers. Meanwhile, bilateral treaties have gradually lost their relevance in this area. Currency devaluations in the countries of the South and the absence of any adjustment to benefit levels have reduced the allowances paid to the children of racialized migrant workers in those countries to token levels.

Although child support ran along different lines in Britain, the British authorities similarly cut off child benefits to the Commonwealth workers with children in their home countries through the suppression of the universal credit tax (Children Tax Allowances) in 1977. The new Child Benefit Scheme excluded non-resident children from any governmental support. Having no internationally binding agreements on family allowances with the notable exception of the EC regulations and an agreement concluded with Spain, this policy change primarily targeted postcolonial workers. A confidential note shed light on the intended unequal effect of this new piece of legislation:

A high proportion of those adversely affected – for each non-resident child the pay packet of a basic rate taxpayer would be reduced by up to £62 per week – are immigrants and the measure may well be attacked as racially discriminatory, even though the same treatment would be given to immigrants from all countries except the EEC and Spain.Footnote 68

In India and the West Indies this cut impacted 200,000 families and 560,000 children. Step by step, the protection of the post-imperial communities was withdrawn, and a dual standard in international law became established.

4.3.3 White Privilege in European Law.

As should by now be clear, EEC law and later EC law progressively established a dual standard. It translated racial considerations into legal statements. Throughout the 1970s, and especially in the Bozzone ruling in 1976, the European Court of Justice judgments cemented White privilege in dealing with two different legacies of European empires.Footnote 69 In general, the Court left African people aside to grant European workers the protection of the EC regulations but treated non-European empires differently than European ones.

Regarding the question of social security for Europeans, the European Court of Justice extended the EC territory to the former colonies. When Congo gained its independence, Belgium organized the legal status quo in regard to the regime of property in an effort to preserve European interests (meaning: the interests of the White population in Congo). Among other institutions, Belgium retained possession of the part of the Congolese social security office (Office de Sécurité Sociale de l’Outre-Mer or OSSOM) concerning the Belgian workers (civil servants, technicians, managers) as well as all its financial assets. Through a law passed two weeks prior to independence, Belgium guaranteed the rights acquired by the Belgian workforce during the colonization of Congo.Footnote 70 The Belgian State had to preserve the social security rights its nationals acquired when they worked in the Belgian colonies during the colonial era. Between 1972 and 1977, the European Court of Justice repeatedly condemned the OSSOM because of its discriminatory nature: Belgian nationality was a precondition to receive pension benefits from the OSSOM.Footnote 71 The OSSOM did not consider the EEC workers in the former Belgian colonies to be ‘migrant workers’ in the sense of the EEC/EC law as they exerted a professional activity outside the territory of the Member State. The matter was of some financial importance: 20 per cent of the more than 60,000 persons insured in 1960 by the OSSOM were foreign nationals, half of them coming from an EEC country. In the Bozzone case, the European Court of Justice referred to the disposition of the Treaty of Rome related to the freedom of movement. The Court declared the colonial law of 1960 discriminatory as Congo was considered part of the Belgian territory at the time. In doing so, the Court extended the European jurisdiction to Congo, Rwanda and Burundi, and reserved the social security benefits to EEC nationals. In the cases of Congo or of Algeria studied by Megan Brown, the Court considers the colonial territory as part of the territory of the Member State when it comes to establishing the right to social security or other types of pensions. In the case of the Belgian Congo, this benefited only EEC migrants, that is: EEC nationals having worked in an EEC colony. This jurisprudence excluded de facto the non-Europeans.

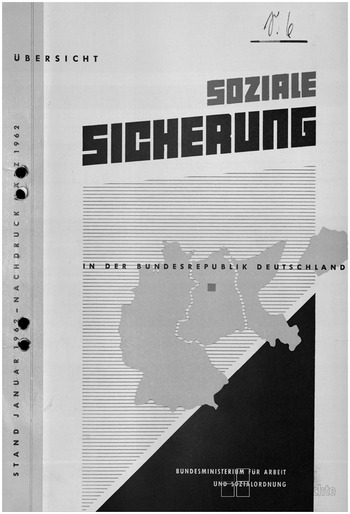

This situation constituted a dual standard and hierarchized the types of imperial belonging along a racial border. Not only colonial states had indeed been empires: Germany could be considered a continental empire until 1945 as well. The redrawing of the German borders during and after the Second World War had massive effects on the entitlements of the persons insured by institutions that either disappeared or relocated. Persons living in Poland or in Czechoslovakia would not be paid social benefits by German institutions. German refugees from Eastern Europe lost their German entitlements as they acquired their rights to pension or to unemployment benefits outside the state borders. To solve the domestic problem posed by the 20 million refugees on its soil, in 1960 Germany reformed its pension system. The main actor of this reform was Kurt Jantz. Born in Berlin, Jantz (1908–1984) had worked for the Department of Social Security at the Reichsarbeitsministerium (Reich Ministry of Labour) since 1938. After a short interlude in the aftermath of the Second World War (the reasons for which are unclear, but probably denazification related), he briefly worked as a university professor of theology before returning to state affairs in 1951. In 1953, he was appointed head of the Department of Social Reform at the Ministry of Labour. He remained in high-level positions throughout the 1960s and 1970s and represented Germany in the European social security institutions. In a nutshell, the reform he led granted German refugees on the soil of the Federal Republic social security rights as if they had never left German soil. The 1962 cover of the information bulletin of the Ministry for Labour and Social Order is a graphic representation of this legal fiction: the territory of German social security law was the whole ‘Reich’ in its 1919 borders (see Figure 4.1). In a way, social security reconstituted the defunct imperial community.

Figure 4.1 Leaflet of the Ministry for Labour and Social Order (Bundesminiterium für Arbeit und Sozialordnung), Social Security in the Federal Republic of Germany (Soziale Sicherung in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland) (1962).

Figure 4.1Long description

Leaflet cover of the Ministry for Labour and Social Order, titled ‘Social Security in the Federal Republic of Germany’ from 1962. The cover features a stylized map of Germany with the title ‘Soziale Sicherung’ prominently displayed. The document is dated January 1962 and is published by the Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Sozialordnung.

Yet, the situation raised a European issue: how should workers from other EEC/EC countries who had worked, whether as war prisoners or as migrants, in the eastern part of the German territory be treated? Should the ‘equality of treatment’ apply? In 1977, the Fossi ruling brought this question to the table.Footnote 72 Fossi worked in the Sudeten from 1942 to 1943 and under German law was socially insured by a German institution, the Sudetendeutsche Knappschaft (miners’ association). The central question was what territory was covered under EEC/EC law, and for Germany, this could carry a heavy financial burden as all the territories annexed by the German Reich could be included (such as Luxembourg and Alsace). In a document he prepared in order to plead the German case in front of the European Court of Justice, Kurt Jantz argued that the Federal Republic of Germany and the Reich were two different states, and that there could be no comparison with colonial states – French Algeria and Belgian Congo.Footnote 73 In contrast to its legal statements regarding colonies, the European Court of Justice rejected the claim. It considered that the 1960 pension law was aimed exclusively at the German national community and was benevolent (and not a social security right), dedicated to alleviating the harshness of exile.

4.4 Conclusion

To conclude, the interdependency between European mainland countries and their former colonies had an impact on EEC law and later EC law in the fields of free migration and social security. The Treaty of Rome paved the way to a dual standard for paradoxical reasons (preventing southwards migration, i.e. European countries flooding Africa with their low-skilled migrants). It treated European (Article 48 EEC) and African territories (Article 135 EEC) separately, postponing the freedom of movement for Africa to later negotiations – with the exception of the French ‘old colonies’ and of Algeria. The two polities did not immediately part ways, and the provisions of international law (embodied in bilateral treaties between former colonial powers and independent countries) and of EEC law remained comparable. A competition between postcolonial and European policies certainly was one of the reasons the ‘European priority’ on the labour market did not prevail in the 1960s. EEC law accepted the ad hoc idea that former colonies, having enjoyed ‘special relations’ with an EEC Member State, could not lose their privileged access to the labour market of their former mainland country for the benefit of EEC workers.

However, their exclusion from the scope of what had then changed name from EEC to EC regulations left African migrants less protected in the 1970s when France and the UK repealed the bilateral agreements (and other provisions) on free migration, unlike European migrants who remained under the protection of the EC law. This dualization of the international system went hand in hand with the resilience of EC social security law whose dynamism left the postcolonial standards behind, and postcolonial workers less protected by the obsolescence of the bilateral agreements. This racial bordering of Europe, and the implicit racial hierarchies established by the means of international law, were not a given at the beginning of the process, but were rather the consequences of the immigration policies in the 1970s and of the legal forms of protection (bilateral/European) afforded to migrants.