During the so-called Viking Age – from the late eighth century to around 1050 – Scandinavians travelled far afield, and many settled permanently overseas. Over time, the emigrant populations became Christian, a conversion that was only later followed in the emerging kingdoms of their homelands of Norway, Denmark and Sweden. Thanks to the preservation of a repertoire of Norse mythological and cosmological lore by later medieval writers, especially in Iceland, we think we know a great deal about the religious world that Christianity replaced. However, the process of leaving it behind took place largely in darkness, and, when written traditions developed at a later time, even constructed conversion narratives are few and far between. Norway celebrated the brutal triumphal campaigns of St Olaf, a missionary king par excellence, and Iceland developed a literature harking back to the adoption of Christianity by arbitration.Footnote 1 However, where Scandinavian populations settled overseas in Christian societies – whether Britain, Ireland or Normandy – the churches that absorbed these newcomers seem to have shown little interest in recording or commemorating their conversion history.

The Scandinavians of the diaspora occupy a complex position in relation to this volume’s theme of ‘Margins and Peripheries’.Footnote 2 As, initially, followers of traditional polytheistic religions, in Christian terms their paganism made them outsiders, alien and threatening. Military, political and economic success nevertheless gave them dominant roles in many new environments, often placing them at the centre of highly Christianized societies, and their impact as immigrants remained significant even where independent Scandinavian political power was overturned. Some of the mobile army members and later settlers could have been converts, but even after they had been overseas for some time it is arguable that the majority remained pagan. That they became Christian tends to be taken for granted, but in the absence of conversion narratives, the mechanisms that brought this transformation about are often assumed to be irrecoverable. Bringing these communities of outsiders into the Christian fold must nevertheless have offered a challenge to all the churches. Some are known to have actively cooperated with the regimes the Scandinavians established, but it is difficult to envisage the pastoral response of religious establishments to the influx of incomers, as the sources are so few, so fragmentary and so random. In consequence, the religious interface between the Scandinavians and the churches where they settled has remained largely unprobed. Even if these conversions can only be construed from indirect evidence, I would like to argue that the sources are sufficient to reveal a diversity of experience for the new Christians and a striking creativity of approach by at least some of the churchmen faced with the task of converting them.

No single template of conversion could have fit all the Scandinavians of the diaspora. In addition to the obvious differences in political organization, social structure and economic practices in the zones of settlement, the churches of the regions where Viking armies were active and Scandinavian settlers made permanent homes were distinctly varied, with strong or weak episcopacies, dynamic or decadent monastic communities, and significantly different local cults. Some were clearly seriously weakened by years of war followed by hostile takeover; others were apparently robust. The nature of the Scandinavian immigration – elite takeover, peasant migration, urban or maritime mercantile communities – also differed, and all these factors conditioned the process of religious interaction. Each region therefore had its own chemistry, and locations of encounter between pagans and Christians spanned the economic, social, political and ecclesiastical spheres. The categories are overlapping, of course, but investigation of the economic context could lead us to the merchant quarter allocated to the Rus’ nation in Constantinople, where traditional Rus’ laws and pagan religious protocols were respected in the heart of Eastern Christendom. The social route could take us to an Icelandic farm where everyday non-Christian religious rituals were performed by households which included Christian Irish slaves.Footnote 3 The canvas is too vast to consider fully here, so I will focus on the interface between Scandinavian pagans and native Christians in political and ecclesiastical encounters and on two settings: Francia and northern England in the ninth and tenth centuries.

But first: what would have been involved in Christianizing immigrant Scandinavian populations? Conversion narratives usually describe missionaries going to do God’s work among the heathen, not what Christians should do when the heathen come and live next door. The terrain of investigation into the process of conversion can be a methodological and terminological minefield. At least four different criteria have been used to identify converts: is it sufficient merely to have received the sacrament of baptism, or is it the performance of Christian ritual that indicates that people have converted? Does conversion entail the taking onboard of a system of belief, or does it mean a life lived according to a new set of rules and moral guidelines? Understanding what Scandinavian pagans were converting from is similarly problematic. The term ‘pagan’ is loaded with judgements and pre-conceptions, and while one alternative, ‘pre-Christian’, may avoid this baggage, categorizing practices and beliefs with reference to what came to replace them is not ideal. Recently adopted by the noteworthy collaborative project, ‘The Pre-Christian Religions of the North’,Footnote 4 it nevertheless has the advantage of indicating the plurality of practice, whereas ‘paganism’ and other alternatives – ‘traditional’ religion, ‘Old Norse’ religion – mislead by implying a non-existent uniformity; regional variation was evidently standard also in the homelands.

Although contemporary evidence is far from plentiful, it does allow us to see that, in the ninth and tenth centuries, forms of religious practice brought from home were followed by Scandinavians in diaspora locations. Even this scarce and uneven evidence reveals traditional religious themes, but with overseas variations that stemmed from military campaigning, migration and exposure to Christianity in different locations, reflecting the diversity of local experience. It has been said that by the ninth century, Scandinavian paganism was ‘degenerate’ and ‘run-down’, ready to submit to Christianity,Footnote 5 but reconsiderations of the nature of religion have prompted something of a rethink of this assumption.Footnote 6 The recovery by metal-detectorists of increasing numbers of apparently pagan amulets has also changed the picture of religious life on the road. Almost identical images representing gods and mythical figures are found across the Scandinavian world, in the homelands and overseas alike: forty-one Thor’s hammers in England to date, for example.Footnote 7 I have argued elsewhere that an active and dynamic paganism underpinned the lives of the men, women and children who made up the army communities that led semi-nomadic lives overseas during the course of the ninth century.Footnote 8 When they gave up mobile warfare and settled, maintaining their religion could help sustain immigrants’ sense of connection with their homelands; losing it could help them assimilate.Footnote 9

Some scholars are cynical about the process. The few Viking-Age conversions outside Scandinavia that are recorded in contemporary texts took place in the diplomatic sphere in connection with peace agreements between Christian rulers and Viking leaders.Footnote 10 This was politics, of course, and therefore – the sceptical thinking goes – these so-called converts are not to be taken seriously as converts; Vikings agreeing to be baptized by kings must have been unscrupulous and opportunist. Dyspeptic Frankish churchmen first voiced this view. Vikings were feckless, sneaky and unreliable; they were too stupid to understand Christianity; they were only motivated by self-interest and greed, accepting conversion for the rich gifts handed out by royal sponsors; convertis de façade, in François Neveux’s telling expression, they failed to take their new religion seriously.Footnote 11 Variations on this theme appear in annals, narratives, poetry, sermons, exegesis and liturgical texts, where Vikings were seen to fulfil the prophecy in Jeremiah 1: 14, that evil shall come from the North. Comments such as these were not impartial: annalists and other writers often had political agendas, and colourful tabloid-style Vikings were useful weapons for critics of the king. In the 880s, Notker’s biography of Charlemagne caricatured Vikings who presented themselves for baptism at the court of his son, Louis the Pious: one Viking complained about the quality of the white baptismal robes, which were, he grumbled, inferior to those he had been given on many previous occasions.Footnote 12 Presented as ‘comically unchanged by their encounter with Frankish Christianity’,Footnote 13 Vikings were not just ridiculous, however; they were also dangerously duplicitous. Pierre Bauduin has argued that in Francia, throughout many decades of warfare punctuated by truces and alliances, stories of suspect and fraudulent Viking converts reveal significant anxiety among the Franks about the collaborative relationships engendered by the turbulent military and political situation.Footnote 14 In the 990s, Richer of Reims’s Historia featured an anecdote in which a retainer of King Odo (r. 888–98) killed a Viking chief just as the king was about to lift him from the font; the murderer defended himself by arguing that the Viking would have been ‘the cause of future calamity’, and he was later rewarded with land and honours by the king.Footnote 15 Vikings who failed to take their conversion seriously were not only denying God, they were deceiving the Frankish establishment by pretending to be allies, integrated into Christian society.

There were doubtless Vikings who were feckless, greedy, ignorant and unreliable, but to my mind the tetchiness and satirical tendencies of these clerical authors have had a disproportionate impact on scholars. So has another argument, that as Scandinavian paganism was polytheistic it had ‘room for another god’, and Viking-Age converts simply ‘added Christ to their pantheon’.Footnote 16 Converting, according to this thinking, would therefore have involved little change. I would question this too: for one thing, the church taught an extensive programme of regulated Christian living in the early Middle Ages, at least as an aspiration. Furthermore, ‘just adding another god’ inaccurately reduces Scandinavian paganism to the worship of gods and goddesses. Scandinavians did worship a range of deities, and their religion lacked Christianity’s single creed, authoritative scriptures and standardizing institutional infrastructure. However, like contemporary Christianity, traditional pagan religions were a way of life: daily interactions with the transcendental in the form of public and domestic ritual provided the contours of the political, social and physical landscape in which people lived.Footnote 17 The subject is admittedly obscured by the lack of contemporary evidence, making conclusions hypothetical, and (as we shall see) substitutions of one (Christian) thing for another (pagan) one certainly helped ease the process of change. Nevertheless, unexplored assumptions continue to have too much influence on perceptions of religious life in this period which then cloud our understanding of conversion. The premise that faith and doctrine are the essence of religious identity, for example, is not helpful here.

This is made clear in a source relating to the Bulgars, not Scandinavians but a contemporary people living on the Volga river. Their ruler, Khan Boris, was considering accepting Christianity from Rome, and he wrote to Pope Nicholas I in the 860s with one hundred and six questions. Can a man have two wives, he asked; and would it still be forbidden to eat near the king at his table? Just one wife, said Nicholas, and while the current practice of sitting on stools far away from the king and eating off the ground was, in his view, bad manners, it was not ‘against the faith’.Footnote 18 The implications of being Christian were troubling Boris, as Bulgar religious identity was linked to a wide range of everyday behaviour. The pope was reassuring. Asked whether the Bulgars could continue to wear trousers, he replied that ‘we do not wish the exterior style of your clothing to be changed, but rather the behavior of the inner man within you’ – unless what they were doing was a sin.Footnote 19 The pope’s answers make it clear that the complete transformation of social customs was not a prerequisite for a good Christian life. On the other hand, the workings of the devil that were manifested in ‘observations of days and hours, the incantations, the games, iniquitous songs, and auguries’ were to be entirely abandoned.Footnote 20

Contemporary Scandinavian concerns are unfortunately not so richly documented. As Francia shared a border with Denmark, however, it was on the receiving end of Viking activity for many years before the conversions of the homeland kingdoms, and Frankish observers of politics and war occasionally offer glimpses of their pagan neighbours’ religious protocols. Casual details in the record of events show that religious difference was no obstacle to treaty-making between pagans and Christians, for example: each side sealed contracts with their own religious rituals.Footnote 21 In England, King Alfred (r. 871–99) famously made a treaty which Viking leaders confirmed with oaths on a holy ring.Footnote 22 However, sometimes Christian kings, including Alfred, made baptism a condition of defeat or alliance, a strategy that is attested in Viking-Christian military and diplomatic relations for almost two hundred years.Footnote 23 It had its successes, though as we have seen, failure made better copy. Standing sponsor at baptism made kings the spiritual fathers of Viking leaders, establishing a dominance through religious and social ties that aimed to make the baptized subject to their military and political authority as well.

In the 860s, one Viking found this out the hard way. A letter to Roric, a ‘Northman converted to the Christian faith’, from Hincmar, archbishop of Reims (845–82), shows how churchmen could act as the Frankish king’s party whips.Footnote 24 Hincmar warned Roric not to help Baldwin, count of Flanders, who had been excommunicated for seizing Charles the Bald’s daughter Judith and marrying her. In Hincmar’s framing of the situation, it was Roric’s conversion that had committed him politically: it was his responsibility as a Christian to toe the party line and support the king. The letter points out the religious consequences of disobedience: if he goes against the king’s wishes, Roric’s baptism will count for nothing, says Hincmar, and the prayers of the saints will be useless and unable to help him.

Roric seems to have complied; he had been given a grant of land and he had a territory to run, sufficient motive, presumably, to submit to the king’s command. For leaders of Viking armies whose baptisms had sealed more temporary arrangements, however, religious commitments need not have lasted long. In 876, ‘a group of Northmen were baptised … but afterwards, like typical Northmen, they lived according to pagan custom just as before’, grumbled a Frankish annalist.Footnote 25 The complaint that Vikings were being baptized more than once was a repeated charge. However, if this was so and (as I believe) serial baptism was not just a trope but a real strategy for difficult times, the instigators of this practice are unlikely to have been ignorant and untrustworthy Vikings. Baptisms, after all, were performed by bishops and priests, and kings and other great men acted as sponsors. Despite being deplored by vocal anti-Viking churchmen, such a practice must have been implemented by their fellow bishops and royal patrons. This was a politically volatile time in the Frankish empire, and many peace agreements and alliances – with or without baptism – were made and unmade soon thereafter. When agreements broke down or outgrew their usefulness, Viking bands moved on, whereupon other lords might seal further short-term arrangements at the font. This was a violation of canon law, but churchmen were expected to be loyal to their lords and leaders, and the usefulness of baptism as a political instrument could override other considerations. There were also relationships between Viking bands and Frankish lords lower down the social ladder, although whether baptism was ever involved there is unknown. These relationships were similarly condemned for religious reasons. Fulk, archbishop of Reims (883–900), complained that local lords submitting to the protection of Vikings were abandoning their Christian religion; and in a fiery letter to Charles the Simple he condemned the king’s alliance with a Viking army in the 890s as an association that would corrupt the purity of Christians.Footnote 26

Another way kings attempted to subdue the Viking threat was by granting land and power, delegating the task of ruling small polities in their name to Viking chiefs like Roric, who thereby acquired a political identity and a place (admittedly precarious) amongst the elite.Footnote 27 The best attested example – and the most successful – is the grant of Frankish territory to Rollo in 911. While Rollo and his men may have been baptized to seal the political deal that put them in power in their terra Normannorum, no treaty-text or contemporary reference survives, and a gap in the annals leaves us ignorant of the arrangement that created Normandy and reliant on later, tendentious, sources. Although it may have increased the chances that the venture would succeed, it was apparently not always the case that land grants required the Viking recipient to convert.Footnote 28 Chronicles and hagiographies claimed that Rollo showed himself to be a glorious Christian, but they are all late, partisan and unreliable, especially on this religious question.Footnote 29 One contemporary survival, however, offers a snapshot of the early days of his regime. Some five to ten years after the grant to Rollo, Wido, the archbishop of Rouen, wrote to his colleague Herveus, archbishop of Reims (900–22). In turn, Herveus wrote to the pope, John X (914–28), who replied:

Concerning the Northmen, recently converted to the faith … . So brother, what should be done with regard to this that you have made known to us, that the Northmen have been baptised and rebaptised, and after baptism they have lived like heathens, and that in a pagan fashion [paganorum more] they have killed Christians, slaughtered priests, and eaten food sacrificed to the idols they worship?Footnote 30

Wido’s letter has not been preserved, but he had evidently reported that while some of the neophyte Viking Christians were compliant, others were baulking at the constraints of their new religion. How should he and his clergy deal with the crisis? In reply, the pope sketched out the guiding principles of a pastoral programme:

If they were not in fact novices in faith, they should face canonical judgment. However, since they are immature in faith, we entrust to your deliberation and judgement how to judge, since you, having that people in your neighbourhood, can better than anyone else seek to convert them and understand their ways and likewise all their deeds and how they live.

… For you well know that one should proceed with them more gently than holy canons decree, lest burdens of which they have no previous experience prove (God forbid) too heavy for them, and … they relapse into the old ways of their former life, which they had abandoned.Footnote 31

At least some of the bad behaviour mentioned – attacking churches, killing priests – may have been the collateral damage of war and political infighting; but the qualifying paganorum more might suggest something more sinister, and the reference to sacrifices to idols gives the actions of the Viking forces an explicitly religious definition. The pope made it clear that even in these less-than-ideal circumstances churchmen had the responsibility of making good Christians out of the kind of rough converts created by political settlements. Nevertheless, he acknowledged that the situation required special measures, and he recommended a lenient, flexible and accommodating approach, where it was not always necessary to obey canon law, and where converts were not to be judged by the standards applied to the local flock. The real burden of reply, however, fell not on the pope but on the archbishop of Reims. Herveus assembled for his colleague in Rouen a dossier of twenty-three chapters containing extracts ‘from the sentences of the Fathers and from the canons and decretals of the Roman pontiffs’ which offered guidance to Wido’s clergy.Footnote 32 Authorities cited range from Scripture through late antique texts to Bede, covering a variety of topics relevant to a pastoral programme. There is nothing in the collection about what the converts are to be taught to believe, however: the focus is discipline, not doctrine. Running themes include the authority of bishops and the vocation of the clergy, past measures for dealing with idol worship and pagan feasts, apostasy, serial baptism,Footnote 33 repentance and redemption. Penance is frequently recommended and is central to the approach. One extract specifies that it should be tailored to personal circumstances, including sex and age.Footnote 34

I have so far discovered nothing from the period to match this dossier’s snapshot of uncooperative Viking-Age converts in collision with Christian expectations, nor its outline of a pastoral programme specifically designed to absorb them into the church. Its message of leniency and tolerance, however, had many precedents, often building on Paul’s observation in 1 Corinthians 3: 2 that ‘babes in Christ’ should be fed milk, not meat. In early England, for example, the ‘milk of simpler teaching’ had been recommended as appropriate until the ignorant ‘grew strong on the food of God’s word … [and] were capable of receiving more elaborate instruction and of carrying out the more transcendental commandments of God’.Footnote 35 While the approach articulated by the pope and the archbishop in the dossier shares this vision of gentle progress, it is striking how much it contrasts with the uncompromising anti-Viking line expressed by other churchmen in the public sphere. Herveus’s brief prefatory remarks do include a conventional denunciation of apostates (the lapsed Viking converts are like dogs returning to their vomit) which may reflect the lost letter from the beleaguered local churchman, Archbishop Wido. However, the correspondence between Pope John and Archbishop Herveus seems to be intended to inform, not express judgements; its matter-of-factness is far removed from political point-scoring and that rhetorical device, the imagined Viking. This dossier appears to be a thoroughly practical piece of ecclesiastical business, churchman to churchman, in which, I would argue, we are hearing the authentic voice of experience at the interface between pagan and Christian, a voice notably silent elsewhere. If so, it is a rare contemporary witness to an active religious life in a Viking army. The dossier’s seemingly unprejudiced snapshot of pagan activity among Rollo’s followers and the responses of these senior clerics to the request for help offer unusual insight into ecclesiastical thinking about how one location of encounter could theoretically be navigated.

Unfortunately, there is no way of knowing how far – or even whether – the proposed programme was implemented. There is no trace of the dossier in Normandy. The surviving manuscript, copied at Reims in the tenth century, is now in Paris.Footnote 36 The ninth century had seen significant disruption in Francia, and opinions differ as to the degree of continuity of infrastructure in the region after its cession to Rollo, including the state of the church led by the province’s archbishop.Footnote 37 Throughout the tenth century, archbishops were apparently in post in Rouen, where they had close relations with the Scandinavian ruling regime, but the restoration of other dioceses was very slow: bishops were not in place everywhere until the 990s, many years after the Viking takeover,Footnote 38 suggesting that the episcopal church at least may have struggled to assert itself across the province. The picture is obscured by the fact that by c.1000, when the church emerged from an almost invisible first century of Norman rule, the written record was largely monopolized by its patrons, the powerful dukes who were Rollo’s descendants.Footnote 39

Across the Channel, a different dynamic was in place, as resistance to Viking attack had largely failed everywhere but in the Wessex of King Alfred. The rulers of England’s three other kingdoms had been defeated in the 860s and 870s by Viking armies who then seized power, after which substantial areas of eastern and northern England were settled by their followers. In the 890s, Pope Formosus threatened ‘all the bishops of England’ with anathema, having heard that ‘the abominable rites of the pagans have sprouted again in your parts and that you have kept silent, like dogs unable to bark’, a lack of bishops being apparently partly to blame.Footnote 40 Since they had ‘awakened’ and ‘begun to renew the seed of the word of God’, Formosus had withdrawn his threat of excommunication, he said; but he gave no explanation of how the bishops’ seed was being sown, and there is no further correspondence, no other record, and no dossier on the Reims model to help construct a picture of how change was being pursued.

While the conversion of those Scandinavians who settled in England may be unrecorded in the archives, it is nevertheless highly visible in the landscape in the form of carved stone monuments. Before the Viking Age, the English church had a longstanding tradition of sophisticated stone sculpture tied to devotional and funerary practices; after the Scandinavian settlement, this art was transformed, especially in northern England. Devotional monuments continued to be raised, but sculpture became increasingly important in secular society as a means of commemorating the dead in a Christian setting. The Scandinavian homelands had no comparable tradition of carved stone at this time, but political change and new patrons brought new ideas and aesthetics which, combined with the models and inspiration of the preceding ‘Anglian’ period, led to significant innovation. The technology, material and form of the many crosses and grave-slabs erected were largely local, but the ornament and iconography introduced were in many cases inspired by Scandinavian connections and radically different from previous English norms.

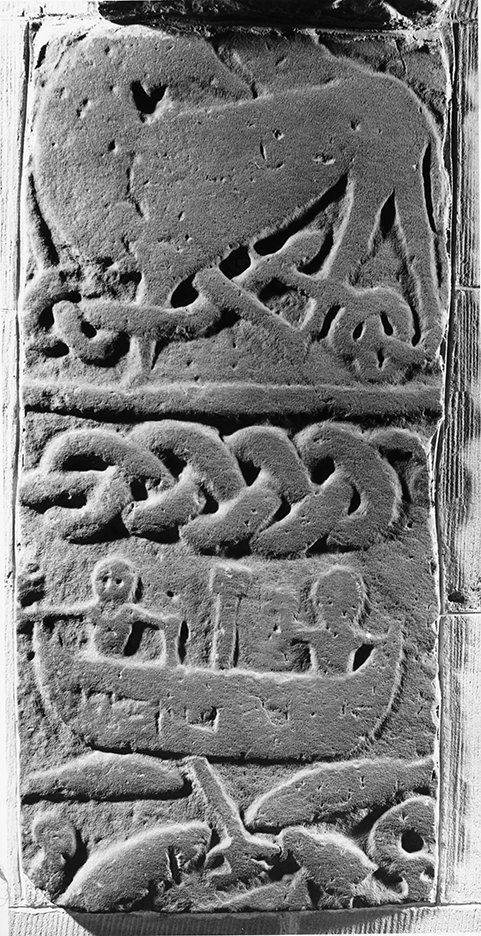

One striking subgroup of sculptures in northern England, for example, incorporated characters and scenes from Norse mythology, images that would have been immediately recognizable to a Scandinavian audience. The god Thor, his line baited with an oxhead, is shown fishing for the World Serpent on a fragment of a slab or frieze at Gosforth in Cumbria (Figure 1).Footnote 41 Stones with mythological references such as these are all preserved in church settings and also bear conventional Christian imagery. Above Thor on the Gosforth fragment, a hart, a symbol of Christ, is entangled in the coils of a snake: on this one stone, therefore, ‘two gods struggle with evil in serpent form’.Footnote 42 Interpretation of these monuments has varied: it has sometimes been assumed that the people who put them up ‘weren’t really Christian’; or they were so ignorant of Christian teaching that they failed to realize that Thor was incompatible with Christ, that one God meant just that. The decorative scheme has also been seen as evidence of a hybrid religion, a regional amalgam of Christianity and Norse paganism.Footnote 43 While there may of course have been pressure from below, from Scandinavians unwilling to give up their religion, stones like these are unlikely to have been raised without ecclesiastical involvement. The specialized craft of production, the appropriation of religious space and, most importantly perhaps, the thinking that is represented by these images strongly suggest that the church was involved. Analysis by Richard Bailey and Lilla Kopár has proposed that the mythological references to gods and heroes were actually in dialogue with Christian content: their pagan narratives were conscripted to a new purpose and were deployed to illustrate Christian truths.Footnote 44

Figure 1. Fragment of a slab or frieze, Gosforth, Cumbria. Copyright: Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture, University of Durham. Photograph credit: Tom Middlemass.

Norse mythology and Christian images are also paired on the large cross in Gosforth churchyard (Figure 2).Footnote 45 Here, Christ stands within a frame, blood pouring from his side. Above him (mid-cross), Viðar, the son of the god Oðin, prises open the jaws of the wolf that had killed his father, poised to tear it apart.Footnote 46 Viðar’s act belongs to a central narrative of Norse mythology, Ragnarøk, the apocalyptic battle between the gods and the forces of evil, and Bailey has argued that the images on the Gosforth Cross represent an eschatological programme that visualized victory over evil and chaos and aimed to inspire ‘reflective contemplation’ by evoking Ragnarøk together with the crucifixion and the Second Coming.Footnote 47 The ring-chain decoration on the lower section of the shaft recalls both Yggdrasil, the earth-tree where Oðin died, and the treow or beam (Old English ‘tree’) on which Christ was crucified.Footnote 48 Viðar and Christ both sacrificed themselves to defeat evil; both nonetheless emerged victorious. The complementary images offered a kind of commentary between two cosmic perspectives, although the driving force was Christian thinking. The juxtapositions invited the onlooker to reflect on the parallels and contrasts, but their presence was purposeful, not simply ‘cultural fusion’: the images are a ‘pagan iconography of Christian ideas’, the approach one of ‘speculative theology’.Footnote 49

Figure 2. Cross, Gosforth, Cumbria. Copyright: Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture, University of Durham. Photograph credit: Tom Middlemass.

Even an image as iconic as the crucifixion, Bailey has argued, could be adapted, and its meaning tailored. In most representations of Christ on the cross, the paired figures in attendance are either Longinus and Stephaton, or John and the Virgin Mary; the two attendant figures on the Gosforth Cross, however, have been identified as Longinus and Mary Magdalene, both arguably archetypes of the converted (Figure 3).Footnote 50 Mary’s dress and hair are Scandinavian in style, familiar from contemporary metal amulets.Footnote 51 Bailey has suggested that the choice of Mary Magdalene and Longinus was intended to further shape the cross’s iconographic programme, enhancing its power to address a newly Christian community more directly.

Figure 3. Detail of Gosforth Cross, Gosforth, Cumbria. Copyright: Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture, University of Durham. Photograph credit: Tom Middlemass.

Bailey has described the Gosforth Cross as ‘an extreme visual response to the advice given by Pope Gregory’ three hundred years earlier, during the Anglo-Saxon conversion, recorded in Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica. Footnote 52 ‘What I have decided after long deliberation about the English people’, Gregory had written to the missionary Mellitus in 601, is ‘that the idol temples of that race should by no means be destroyed, but only the idols in them’; Gregory instructed Mellitus to build altars with relics on the sites of pagan shrines.Footnote 53 This is what God did for the Israelites in Egypt, wrote Gregory: ‘he preserved in his own worship the forms of sacrifice which they were accustomed to offer to the devil.’Footnote 54 Festivals, where animals had been sacrificed to pagan gods, could carry on after conversion because what had been a pagan ritual, killing and eating animals to worship idols, could be continued as a Christian one, killing and eating animals in praise of God. It would not take much to extend this message from rituals and sites to narratives and imagery; they could likewise be allowed to remain unchanged in form, as their meaning was transformed. Bailey has observed that monuments such as the Gosforth Cross, erected centuries after Gregory’s advice, may be the only evidence to survive that people in northern England ‘were capable of this type of radical thinking’ at this time.Footnote 55

How the thinking behind these iconographic schemes went from theory to practice – how it filtered down to parish priests, for example – is obscure. Educated northern churchmen could have been familiar with Gregory’s letter through Bede, although other authorities for this reinterpretation of pre-Christian forms through a figurative lens would have been available. It is sometimes assumed that English, Irish and Frankish clergy knew little about contemporary paganism; but whoever created these decorative programmes must have been sufficiently well informed about pagan gods and myths to make them serve a Christian purpose, pairing that knowledge with Christian teaching, converting Sigurd and Viðar to the service of the true God (as Gregory would have it) and representing them locally in stone.Footnote 56

Monuments like these presumably had a devotional function, but they may also have served as teaching aids, important items in the preacher’s toolkit. The hero Sigurd, who appears on a number of stones – including an elaborate grave-slab from the cemetery at York Minster which featured many episodes of his life – was able to understand the language of birds after defeating a dragon, roasting its heart and tasting its blood.Footnote 57 Might this have helped explain the eucharist to Scandinavian converts?Footnote 58 If, however, we think of the monuments of this subgroup as just static representations of a theological vision of correspondences, we may be missing something about the way sculpture was experienced. Stone monuments may not have been simply ‘monumental’. While surviving Old Norse mythological lore has largely been preserved on the page, it was originally performed.Footnote 59 Viking-Age religion in Scandinavia, it has been argued, was a ‘behavioural experience’; surviving rich textiles show elaborate scenes of what seems to be highly performative spiritual practice.Footnote 60 Moreover, in England, stone could be imagined as animated: in the Old English poem Andreas, the figure of an angel on a frieze not only speaks but leaps from the wall and walks out along the road ‘to take God’s mission’ into the world.Footnote 61 If we think of sculpture as static, we are surely underestimating its performative role and undervaluing its experiential and communicative power.

We can only speculate about how the images on these stones were decoded by contemporaries, however, and interpretations along these lines, postulating a strategy of purposeful, sophisticated, theological thinking, go too far for some. The sculpture nevertheless shows a church readily recruiting and adapting imported images and ornament and apparently comfortable with correspondences from the immigrants’ traditional thought-world. David Stocker has taken a more secular line, suggesting that while the archbishops of York were ‘closely involved’ in the development of iconography ‘pandering to [the] pagan background’ of the settlers, the collaboration was motivated by political necessity: he has argued that these monuments served to articulate the archbishops’ alliance with Scandinavian kings in northern England, a coalition which lasted until the latter’s final defeat by the West Saxons in 954.Footnote 62 A political interpretation would certainly enhance understanding of the ostentatiously Scandinavian iconography on the grave-slab from York, although it is far from clear that it would apply to distant Gosforth, which may or may not have been within York’s jurisdiction.Footnote 63 Unfortunately, these sculptures are also difficult to date,Footnote 64 and art historians’ preference for date-ranges as unspecific as ‘tenth-century’ makes linking monuments and politics problematic. Furthermore, theologically creative decorative programmes as proposed by Bailey need not have been formulated solely for the first generation experiencing religious change. While the pagan-Christian juxtapositions had the potential to speak to converts, the message of correspondence and cultural connection could also have resonated at a later time, well after the initial settlement, when other kinds of capital (nostalgia, ethnic consciousness and regional solidarity) had accrued to the Scandinavian heritage in England.

Ecclesiastical initiatives – pastoral and political – remain hypothetical, and there were other ways in which conversion could occur. More organic and ad hoc forms of religious accommodation between incomers and locals, not driven from above, were no doubt also in play and instrumental in encouraging change. Local Christians and Christianity did not disappear, and there were many ways of attracting newcomers to the faith. Local saints could have drawn pagans into Christian worship, for example, their status as spirits of place akin to Scandinavian animistic traditions. English Christians could have befriended and then sponsored their pagan neighbours at the font. Churchmen were best placed to make decisions about what images could communicate the desired religious message, however,Footnote 65 and, as far as sculpture is concerned, they were the most likely to have spotted the potential of using the Scandinavian inheritance to articulate Christian teaching in material form in this way.

Monuments with mythological images represent only one, relatively small, regional manifestation of a revolution in sculpture that took place in northern England. The stone crosses of the pre-Viking period had been highly stylized, dense with liturgical and scriptural references, sometimes inscribed with Latin or Old English commemorative or devotional texts. After the Scandinavian settlement, another kind of radically different look was introduced. The occasional lapidary inscription in Norse and/or runes survives,Footnote 66 but much more common were crosses and grave-slabs with men on horseback, men with weapons, men with drinking horns; men hunting, standing, sitting: a cross from Middleton (Yorkshire; Figure 4), for example, shows a man with four bladed weapons, a helmet and a shield.Footnote 67 These monuments in local churches or churchyards portraying proudly armed men were a significant innovation, material signs which could combine declarations of lordship with allegiance to the Christian religion. This unprecedented secular self-representation expressed as Christian piety allowed individuals to advertise publicly their incorporation into the society of Christians. Christian art no longer provided the models for Christian monuments in other ways as well: while pre-Viking Christian sculpture had been decorated with ornament that reflected the art of the scriptorium, the large corpus of post-settlement sculpture is exuberantly decorated with art styles modelled on those current in Scandinavia. The Gosforth Cross’s Borre-style ring-chain motif, for example, appears on Scandinavian metalwork and textiles.Footnote 68 These changes in mortuary practice signalled the affinities of a new Anglo-Scandinavian elite in ways that combined elements of their Scandinavian heritage with established conventions of the English church.

Figure 4. Cross, Middleton, Yorkshire. Copyright: Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture, University of Durham. Photograph credit: Tom Middlemass.

In a perfect world, the two halves of this short study would now come neatly together. The strategy of openness, tolerance and accommodation outlined for Rouen’s Viking converts would be seen to manifest itself in material culture resembling these accommodating carved stones from northern England. On present evidence, however, there is nothing in Normandy that exhibits this kind of cultural mix in material form. Scandinavian place-names and personal names are abundant, as is evidence of pride in a Nordic heritage in sources as early as the eleventh century, but Normandy has no comparable corpus of monuments reflecting the Scandinavian origins of its founders.Footnote 69

The contrast is striking, and some of the explanation must lie with ecclesiastical actors. Stone sculpture was a highly developed element of England’s Christian heritage. Faced with a challenge, the church in northern England drew on this cultural inheritance and reworked it to suit a society absorbing newcomers and experiencing change. After the settlement, patrons were not necessarily all of Scandinavian descent, but the new classes of monuments with mythological and secular images allowed immigrants (and descendants of immigrants) to proclaim their new identities and anchor themselves in Christian society without losing everything that recalled their past lives as pagans: neither their language, their visual culture, nor the universe of their imagination. The Norman church must have found a way for its Scandinavian immigrants to become Christian that drew them into the indigenous religious identity, but whether or not that way allowed the converted immigrants to express their difference from the surrounding populations who had been Christian for so long is unclear. Is it significant that in England, the son of a member of the Viking Great Army of the 860s became not just a bishop but archbishop of Canterbury, whereas the earliest known bishop in Normandy with a Norse name was not in post until c.990 at the earliest?Footnote 70 Apart from the archbishops of Rouen, senior churchmen are noticeably absent from the record throughout the tenth century, and it is unclear how many priests remained in place in Normandy to minister to their flocks and apply the dossier’s programme.Footnote 71

The political matrix in which religious change took place nevertheless differed significantly in these two locations and doubtless affected the dynamic between pagans and Christians. The Scandinavian regime in Rouen soon came to identify itself vigorously with the church, and it may have used its new religion as an instrument in the drive to establish control over other communities of Scandinavians settled in the region. Pressure to convert in western Normandy, for example, could have been a reflex of Rouen’s ambitions and – if achieved – unwelcome, a sign of the loss of independence. Since both sides of this particular interface between paganism and Christianity traced their origins to the same homelands, allusions to Scandinavian heritage carried more complications than in England. Only when Normandy’s young leader Richard I (r. 942–96) found himself dependent on unconverted Viking warbands in the mid-tenth century, Fraser McNair has argued, did his court in Rouen develop a language of overarching Norman ethnicity, creating ‘a powerful if rather incoherent sense of group solidarity’ to appeal to the new arrivals.Footnote 72 By the time Dudo of St Quentin finished his history of the Norman dukes in the early eleventh century, Rouen’s supremacy was well established, inter-Scandinavian rivalries were conveniently obscured, and Dacigena, ‘Scandinavian-born’, had become a synonym for ‘Norman’.Footnote 73

We do not know whether the strategy of conversion by accommodation recommended to the archbishop of Rouen by the pope was a resounding success, or abandoned in despair, but there are hints that the approach across Normandy may have been fiercer and more coercive. Samantha Herrick’s study of eleventh-century saints’ lives has highlighted a distinctive regional interest in conversion, suggesting that the issue remained live long after Rollo’s takeover.Footnote 74 In these hagiographical narratives, holy men of the distant past battle pagan shrines and convert populations by force brutally sustained by royal power. Herrick has observed that this implies that, at least in parts of the Norman province, the process of conversion had also been unwelcome in more recent times.Footnote 75 Mark Hagger has argued that conversion was slow and ‘not easily achieved’ in Normandy because ‘coercion could take the process only so far’; ‘hearts and minds’ were only won ‘with the passing of generations’.Footnote 76 What was also required was a reconstruction of the infrastructure of the institutional church, but this was entirely dependent on the extension of ducal political control and far from rapidly achieved.

What did the Scandinavians make of their conversion, however it came about? We can only speculate, but we might wonder whether some of those who experienced a more accommodating strategy could have felt the adaptation of their cultural property as a loss, or perceived in the process an injury inflicted by what we would now call cultural appropriation. Christianity’s attitudes to other religions – its propensity to ‘ingest’ and ‘transform’ them in its own image while insisting on its superiority and separateness – is not universally admired;Footnote 77 nor can its introduction have always been perceived as entirely beneficial by those who accepted it. However, Viking-Age pagans are largely silent, their perspective lost; and the majority of sources relevant to their conversion – whether contemporary or retrospective – were written by churchmen whose work abounds with tabloid-style clichés or tendentious revisionism. Furthermore, in Normandy the origins of the province became entangled in ducal propaganda, and although its Scandinavian heritage came to define its identity, nothing was to be gained by retailing the religious struggles and institutional setbacks that probably characterized the Norman church in its first Scandinavian century. In England, Scandinavian regimes were everywhere replaced in the tenth century by a West Saxon king from southern England, ruling a single unified kingdom. It was consequently not in the interests of churches and churchmen in zones of Scandinavian settlement to talk about old allies; collaborations and compromises might have been better forgotten. In addition to the voice of the Scandinavian convert, we are therefore also missing – with the exception of the Norman dossier – the voice from the ecclesiastical coalface.

Outsiders in religious terms when interactions first began, Scandinavians nevertheless achieved notable power and were major actors in significant settings, as military enemies and allies, kings, merchants and settlers. Religious conversion was a crucial means of bringing them further inside the tent. Without narrative evidence – indeed, without conventional evidence of any sort – an unproblematized idea that conversion ‘just happened’ has taken root, but this tendency to see the transition from paganism to Christianity as an organic development conflates the diverse routes to conversion and ignores their singularity. A focus on the interfaces between pagan and Christian gives more room to the agency of churchmen, although the energy and creativity with which they faced their local challenges can generally only be imagined. The institutional church was not the only agent that brought Christianity to the Scandinavians of the diaspora, but even the scanty sources that we have show churchmen at work with strikingly different solutions to this task.