Introduction

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a common mental health condition with a lifetime prevalence of 12.1%,Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters1 imposing a significant economic burden on healthcare systems.Reference Konnopka and König2 GAD is characterized by unfocused and excessive worry, and uncontrollable anxiety without a direct connection to recent stressful events.Reference Tyrer and Baldwin3 In its severe expressions, the condition may lead to social and occupational impairment,Reference Emmelkamp and Ehring4 poor quality of life,Reference Comer, Blanco and Hasin5 and suicidal behavior.Reference Nepon, Belik, Bolton and Sareen6 GAD often occurs in comorbidity with other mental health conditions, particularly major depressive disorder and other anxiety disorders, which may complicate its manifestations, aggravate its course, and contribute to a worse treatment response.Reference Nutt, Argyropoulos, Hood and Potokar7, Reference Remes, Wainwright, Surtees, Lafortune, Khaw and Brayne8

According to international guidelines, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and pregabalin should be employed as first-line agents in the treatment of GAD.Reference Bandelow, Sher and Bunevicius9, Reference Buoli, Caldiroli and Serati10 Benzodiazepines, such as diazepam, are suggested as secondary alternatives for initial symptom control, in combination with the primary treatment.Reference Bandelow, Zohar and Hollander11 Moreover, some clinical trials have reported a beneficial effect for agomelatine, mood stabilizers, and atypical antipsychotics, either as monotherapy or as augmentation to standard pharmacotherapy.Reference Buoli, Grassi, Serati and Altamura12–Reference Buoli, Caldiroli, Caletti, Paoli and Altamura14 Despite the availability of effective pharmacological and psychosocial approaches,Reference Carl, Witcraft and Kauffman15 only an estimated 43.2% of individuals with GAD receive any form of treatment.Reference Mishra and Varma16

The duration of untreated illness (DUI) is defined as the interval between the onset of a disorder and the administration of the first approved pharmacological treatment, at standard dosages and for an appropriate duration.Reference Scott, Graham, Yung, Morgan, Bellivier and Etain17 A growing number of studies suggest that DUI can modify the course of various psychiatric conditions: a longer delay to treatment appears to be associated with increased suicide attempts, more frequent hospitalizations, and poorer treatment response.Reference Altamura, Dell’Osso, Mundo and Dell’Osso18–Reference Buoli, Cesana and Fagiolini20 While most studies have focused on the role of DUI in psychotic and affective disorders, research across anxiety disorders remains comparatively limited. However, preliminary findings, particularly in panic disorder, suggest that this area warrants further investigation.Reference Altamura, Santini, Salvadori and Mundo21, Reference Surace, Buoli and Affaticati22 Among anxiety disorders, patients with GAD are reported to experience the longest delay to pharmacological treatment.Reference Altamura, Buoli, Albano and Dell’Osso23, Reference Dell’Osso, Camuri, Benatti, Buoli and Altamura24 Despite this, only one study to dateReference Altamura, Dell’Osso, D’Urso, Russo, Fumagalli and Mundo25 has thoroughly examined the relationship between DUI and clinical factors in patients affected by GAD. The study found that a longer latency to treatment was associated with poorer response to pharmacotherapy, prolonged illness duration, and the development of comorbid mood and anxiety disorders.Reference Altamura, Dell’Osso, D’Urso, Russo, Fumagalli and Mundo25 Albeit limited, these findings suggest that a more comprehensive understanding of clinical variables associated with DUI could ameliorate the management of GAD patients. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to identify sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with a longer DUI in GAD.

Materials and methods

Study design and patient’s sample

We conducted a cross-sectional, multicenter study. Outpatients diagnosed with GAD were retrospectively identified from medical records compiled during the pre-pandemic period (2016–2019) at three Italian mental health services: Fondazione IRCCS San Gerardo dei Tintori (Monza), Fondazione IRCCS Ca′ Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico (Milan), and Ospedale Treviglio-Caravaggio (Bergamo). GAD diagnoses were made by a senior psychiatrist based on the criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—5th edition (DSM-5, APA 2013). At the time of the first psychiatric encounter, when medical records were compiled, clinical information was gathered through patient and relative interviews and by consulting the psychiatric database of the Lombardia Region.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) GAD as the main psychiatric diagnosis; (2) fluency in Italian; (3) ability and willingness to sign informed consent; and (4) a minimum treatment duration of 3 months at the outpatient clinic. Patients were excluded on the following grounds: (1) age < 18 years; (2) intellectual disability; (3) other DSM-5 diagnoses of anxiety disorders; and (4) insufficient sociodemographic and clinical information.

The following demographic and clinical variables were extracted from medical records for analysis: sex, age, occupational and marital status, age at onset, duration of illness, DUI (months), presence and type of psychiatric and medical comorbidities before and after GAD onset, cluster of comorbid personality disorder (PD), substance use disorders before and after GAD onset, family history of mental disorders, suicide attempts, hospitalizations, presence and type of obstetric complications, primary pharmacological treatment, poly-therapy, side effects, presence of multiple side effects, treatment duration (months), reason for treatment discontinuation, and the presence and type of lifetime psychotherapy. DUI was defined as the time elapsed between the onset of GAD and the initiation of the first appropriate pharmacological treatment, at standard dosages and for an appropriate duration, excluding benzodiazepines.Reference Altamura, Buoli, Albano and Dell’Osso23, Reference Locke, Kirst and Shultz26

Study procedures adhered to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the research project was reviewed and approved by the local accredited Medical Ethics Review Committee (Area 2 Ethics Committee) of Fondazione IRCCS San Gerardo dei Tintori, Monza (approval code 3955).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses were carried out on the whole sample. Frequencies with percentages were reported for categorical variables, and means and standard deviations were calculated for quantitative variables.

One-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and Pearson’s correlations were conducted to assess the relationship between DUI and categorical and quantitative variables, respectively. To identify the most relevant set of variables independently associated with the length of DUI, a linear multivariate regression model (backward procedure) was then employed, including variables that were statistically significant in univariate analyses.

Statistical significance was set at a nominal p-value of ≤0.05. The aforementioned analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences for Windows (version 27.0).

Results

Descriptive analyses

A total of 243 individuals with a GAD diagnosis were included. Among these, 162 (66.7%) were female, and 81 (33.3%) were male. The mean age of the sample was 47.83 (±16.84) years, and the mean DUI was 30.92 (±65.25) months. Results of descriptive and univariate analyses of categorical variables are presented in Tables 1–4 and the corresponding results for quantitative variables are presented in Table 5.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for the Total Sample (N = 243) on Sociodemographic and Family History Categorical Variables, and Corresponding Results of Univariate Analyses

Abbreviations: DUI, duration of untreated illness; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder; SD, standard deviation.

Statistically significant results are shown in bold.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for the Total Sample (N = 243) on Mental Health Categorical Variables, and Corresponding Results of Univariate Analyses

Abbreviation: BDZ, benzodiazepine; DUI, duration of untreated illness; ED, eating disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; NOS, not otherwise specified; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; PD, personality disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SD, standard deviation.

Statistically significant results are shown in bold.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics for the Total Sample (N = 243) on Categorical Variables Related to Medical Comorbidities and Obstetric History, and Corresponding Results of Univariate Analyses

Abbreviation: DUI, duration of untreated illness; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; SD, standard deviation.

Statistically significant results are shown in bold.

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics for the Total Sample (N = 243) on Categorical Treatment Variables, and Corresponding Results of Univariate Analyses

Abbreviation: AD, antidepressant; BDZ, benzodiazepine; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; DUI, duration of untreated illness; ED, eating disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; SD, standard deviation; SGA, second-generation antipsychotic; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

Statistically significant results are shown in bold.

Table 5. Pearson’s Correlations Between DUI and Quantitative Variables

Abbreviation: DUI, duration of untreated illness; SD, standard deviation. Statistically significant results are shown in bold.

One-way ANOVAs and Pearson’s correlations

Patients with multiple medical illnesses occurring after GAD onset (F = 5.026; p = 0.026) and those with multiple side effects from pharmacological treatment (F = 12.992; p < 0.001) had a longer DUI compared to their counterparts. Moreover, DUI length was significantly different based on the type of psychiatric comorbidity commencing after GAD onset (F = 5.833; p < 0.001), as well as the cluster of comorbid PD (F = 2.855; p = 0.024). In particular, post-hoc analyses showed that DUI was significantly longer in subjects who developed a panic disorder compared to those developing a major mood episode (p < 0.001), an eating disorder (p = 0.001), other psychiatric disorders (p = 0.001), or no psychiatric comorbidities (p < 0.001) after GAD onset. In addition, individuals with a ‘Cluster C’ or ‘Not otherwise specified’ (NOS) PD had a longer DUI compared to those with other clusters or no PDs (p = 0.024). No significant differences were found among patient groups based on other categorical variables.

A significant inverse correlation was found between DUI length and age at onset (r = −0.238; p < 0.001), and a significant direct correlation was observed between DUI length and duration of illness (r = 0.708; p < 0.001). No other significant results emerged for quantitative variables.

Linear multivariate regression model

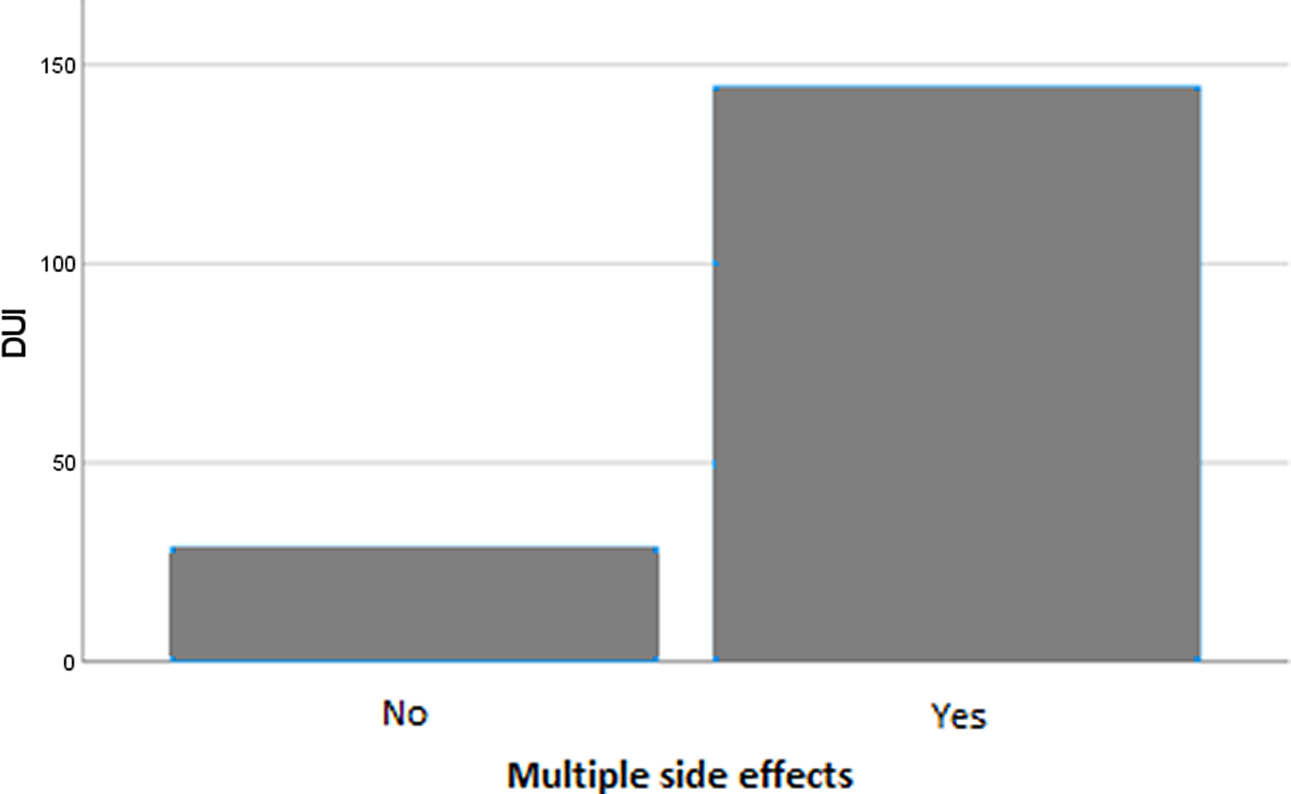

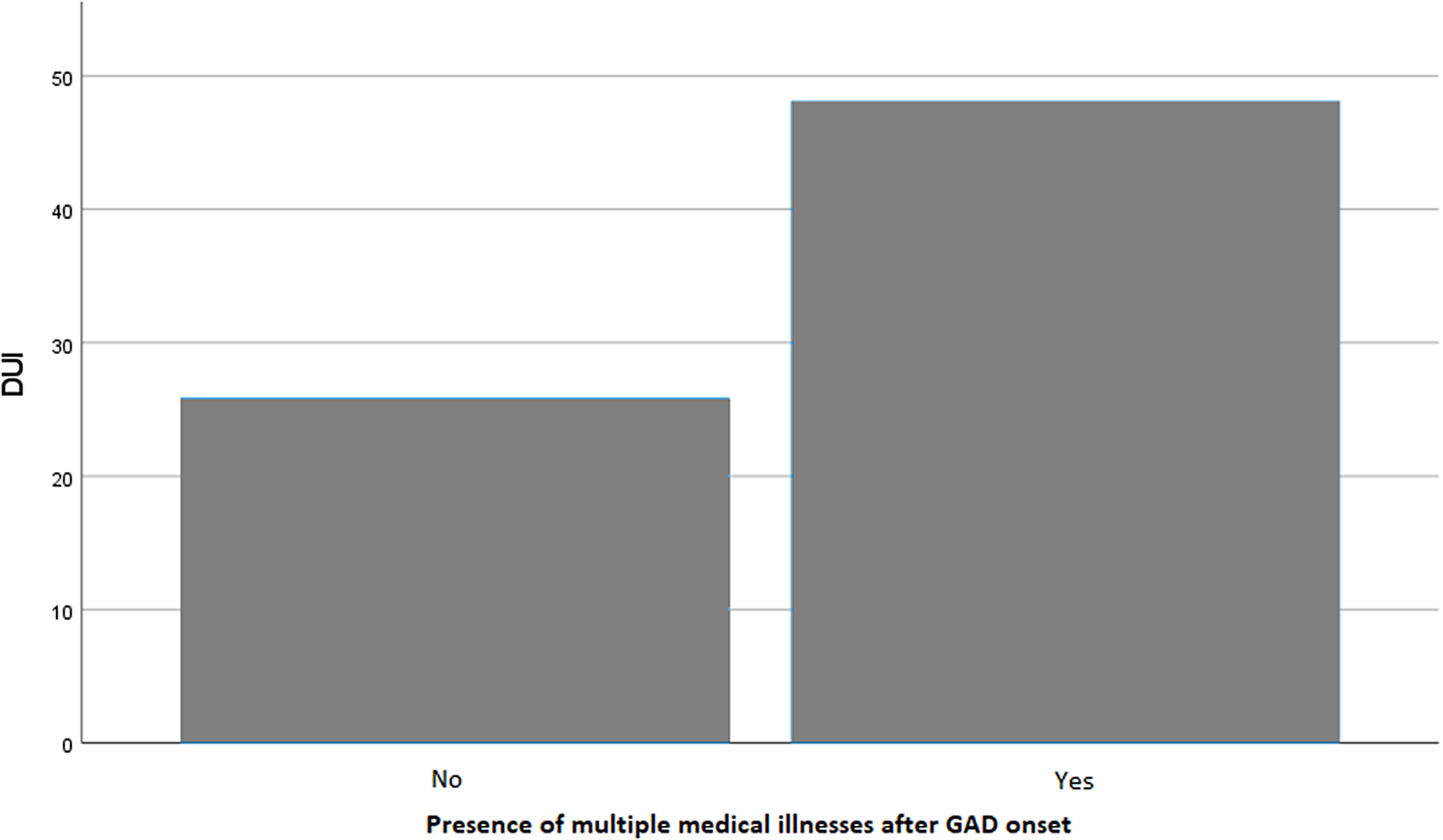

Variables that were statistically significant in univariate analyses were included as independent factors in a linear multivariate regression model, with DUI length as the dependent variable. The model was deemed reliable according to the Durbin–Watson test (1.992). Earlier age at onset (B = −0.428; p = 0.023) (Figure 1), a longer duration of illness (B = 0.431; p < 0.001) (Figure 2), and the presence of multiple side effects (B = 55.778; p = 0.017) (Figure 3) were significantly associated with a longer DUI. Additionally, a trend toward statistical significance emerged for the association between multiple medical comorbidities developing after GAD onset and longer DUI (B = 13.122; p = 0.076) (Figure 4).

Figure 1. Significant association between age at onset and length of DUI (months) in GAD patients. Abbreviation: DUI, duration of untreated illness. Statistics: B = −0.428; p = 0.023.

Figure 2. Significant association between duration of illness and length of DUI in GAD patients. Abbreviation: DUI, duration of untreated illness. Statistics: B = 0.431; p < 0.001.

Figure 3. Significant association between the length of DUI (months) and the presence of multiple side effects in GAD patients. Abbreviation: DUI, duration of untreated illness. Statistics: B = 2.404; p = 0.017.

Figure 4. Trend toward significance in the association between DUI and the presence of multiple medical illnesses after GAD onset. Abbreviation: DUI, duration of untreated illness. Statistics: B = 55.778; p = 0.076.

No further significant associations were found between DUI and the type of psychiatric comorbidity developing after GAD onset or the cluster of comorbid PD (p > 0.05).

Discussion

The present study sought to identify sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with a longer DUI in GAD. Patients with a longer DUI had an earlier age at onset, a longer duration of illness, and experienced multiple side effects from pharmacological treatment. Additionally, a trend toward statistical significance emerged in the association between longer DUI and the development of multiple medical comorbidities after GAD onset. Univariate analyses indicated a positive relationship between longer DUI and the occurrence of post-onset panic disorder (compared to other post-onset comorbidities) and Cluster C PD (compared to other comorbid PDs or no PD); however, these findings were not confirmed in the final model.

The mean DUI in our sample was 31 months (±65.25), with a maximum of 408 months. This aligns with previous findings indicating that patients with anxiety disorders frequently delay several years before initiating appropriate pharmacological treatment.Reference Altamura, Camuri and Dell’Osso27, Reference Dell’Osso, Oldani and Camuri28 However, it should be noted that the mean DUI in our sample was considerably shorter compared to previous studies on GAD—for example, 153.36 ± 85.2 months,Reference Altamura, Dell’Osso, D’Urso, Russo, Fumagalli and Mundo25 87.07 ± 97.47 months,Reference Altamura, Buoli, Albano and Dell’Osso23 and 77.47 ± 95.76.Reference Benatti, Camuri and Dell’Osso29 While this discrepancy may be due to sample characteristics, it may also reflect the progressive reduction in treatment latency observed in psychiatric cohorts in recent years.Reference Dell’Osso, Oldani and Camuri28 The delay in seeking treatment in GAD patients may be explained by the disorder’s insidious onset and gradual functional impairment, which may lead affected individuals not to recognize the need for medical attention promptly. Notably, patients with panic disorder, who typically experience more acute and disabling symptoms at onset,Reference Wang, Berglund, Olfson and Kessler30 tend to report a significantly shorter DUI.Reference Altamura, Buoli, Albano and Dell’Osso23, Reference Dell’Osso, Camuri, Benatti, Buoli and Altamura24 GAD patients may be more inclined to seek treatment when somatic symptoms emerge, turning to primary care physicians. However, somatic symptoms are frequently underrecognized in primary care, leading to extensive tests to rule out physical causes rather than addressing the underlying anxiety disorder.Reference Roy-Byrne and Wagner31 Even when GAD is diagnosed in this setting, it is commonly treated with benzodiazepines,Reference Baldwin, Allgulander, Bandelow, Ferre and Pallanti32, Reference Dell’Osso and Lader33 which may provide temporary symptom relief but also delay the initiation of guideline-recommended pharmacological treatment. Another contributing factor is that anxiety symptoms are often mistaken for personality traits rather than recognized as manifestations of a treatable disorder.Reference Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer and Fang34 Finally, affected individuals often fear medication side effects, which may further hinder the timely management of GAD.Reference Bandelow, Michaelis and Wedekind35

Prior research has highlighted that a prolonged DUI may lead to an unfavorable illness course in GAD and other anxiety disorders, as evidenced by a longer duration of illness,Reference Altamura, Dell’Osso, D’Urso, Russo, Fumagalli and Mundo25, Reference Surace, Buoli and Affaticati22 reduced response to pharmacotherapy,Reference Altamura, Dell’Osso, D’Urso, Russo, Fumagalli and Mundo25 and an increased frequency of post-onset depression.Reference Altamura, Santini, Salvadori and Mundo21 These findings are consistent with our results showing that a longer DUI is linked to both a prolonged illness duration and an increased risk of multiple side effects. It should be considered that prolonged anxiety can lead to alterations in the autonomic nervous system, increasing sensitivity to external stimuli, including the initiation of new pharmacological therapies.Reference Teed, Feinstein and Puhl36, Reference Buoli, Dell’osso, Bosi and Altamura37 Early initiation of pharmacotherapy may, therefore, be associated with better tolerability and effectiveness due to less pronounced dysregulation of biological systems. Notably, the relation between shorter latency to pharmacotherapy and improved treatment response has been reported only for guideline-recommended therapies (e.g., SSRIs/SNRIs)—which are known to induce neural changesReference Nord, Barrett and Lindquist38—and not for benzodiazepines.Reference Altamura, Dell’Osso, D’Urso, Russo, Fumagalli and Mundo25 In contrast, a longer DUI could reduce tolerability, increase the likelihood of poor compliance or treatment interruptions, and contribute to a chronic course of illness.

Our results indicate that patients with a longer DUI are more likely to develop comorbid medical conditions after the onset of GAD. Although this association has not been previously reported for anxiety disorders, increased rates of medical comorbidities have been documented in bipolar patients with a longer DUI.Reference Maina, Bechon, Rigardetto and Salvi39, Reference Di Salvo, Porceddu, Albert, Maina and Rosso40 This relationship may reflect structural barriers to accessing medical care (e.g., lower socioeconomic income and geographical isolation), as well as attitudinal barriers, such as the belief that health issues will resolve without intervention or the fear of treatment-related adverse events.Reference Chartier-Otis, Perreault and Bélanger41 Additionally, untreated patients with GAD are likely to experience elevated stress levels, which may contribute to unhealthy lifestyle choices and increased cortisol production, heightening the risk of poor glucose tolerance and high blood pressure.Reference Young, Abelson and Cameron42

Consistent with a previous study on GAD,Reference Altamura, Dell’Osso, D’Urso, Russo, Fumagalli and Mundo25 our results indicate that an earlier age at onset is associated with a longer DUI. Of note, a similar inverse relationship has also been reported in patients with panicReference Surace, Buoli and Affaticati22 and mood disorders.Reference Altamura, Dell’Osso, Mundo and Dell’Osso18, Reference Menculini, Verdolini and Gobbicchi43 One possible explanation for this trend is that younger individuals and their families may underestimate symptoms, interpreting them as typical emotional dysregulation of adolescence and young adulthood.Reference Reardon, Harvey, Baranowska, O’Brien, Smith and Creswell44 This perception may act as a barrier to seeking treatment, potentially contributing to a poorer illness course.Reference Reardon, Harvey, Baranowska, O’Brien, Smith and Creswell44

Finally, univariate analyses revealed that participants with a longer DUI were more likely to have a Cluster C or NOS PD, or to develop panic disorder, compared to other psychiatric comorbidities. Panic disorder may be considered an exacerbation of symptoms in individuals with untreated GAD, while the presence of PDs may represent an additional obstacle to accessing mental care, owing to avoidant-dependent traits or behavioral rigidity.Reference Garyfallos, Adamopoulou and Karastergiou45

Our findings should be considered in light of several limitations. First, the sample size could have been larger had additional mental healthcare facilities been included. Second, due to the cross-sectional design of our study, we are unable to provide prospective data on long-term outcomes. Moreover, we were unable to include data on illness severity and functional impact, as the retrospective nature of the study meant such information was either unavailable or inconsistently assessed across services using different evaluation tools. We chose to include only patients who had completed at least 3 months of treatment, as this duration is typically required to assess pharmacological response and tolerability; however, this criterion may have excluded individuals with more acute presentations. In addition, the sample size was insufficient to provide adequate power for subgroup analyses. Furthermore, most variables were analyzed dichotomously and then further stratified into specific subgroups; alternative approaches (eg, merging certain categories) may have allowed for more nuanced statistical exploration. Finally, the accuracy of the data extracted from medical records, such as illness onset, may have been affected by recall bias due to reliance on information provided by patients and family members.

Further studies with larger sample sizes and longitudinal designs are needed to confirm the present findings.

Conclusions

Our findings support existing evidence that patients with anxiety disorders often experience significant delays in initiating appropriate pharmacological treatment.Reference Altamura, Camuri and Dell’Osso27, Reference Dell’Osso, Oldani and Camuri28 Individuals with an earlier age at onset may be particularly vulnerable in this regard, as young patients and their caregivers are more likely to overlook symptoms and defer help-seeking.Reference Buoli and Caldiroli46

A longer DUI in GAD appears to contribute to a more complicated illness course, with evidence suggesting that reducing treatment delays could improve disease management.Reference Dell’Osso, Camuri, Benatti, Buoli and Altamura24, Reference Altamura, Dell’Osso, D’Urso, Russo, Fumagalli and Mundo25 The association between treatment delays and a worsening illness course is well-documented across a wide range of psychiatric disorders,Reference Murru and Carpiniello19, Reference Menculini, Verdolini and Gobbicchi43, Reference Zheng, Luo and Yao47 emphasizing the need to implement prevention strategies. Further research is needed to confirm these findings and identify specific intervention targets to reduce DUI in patients with GAD.

Data availability statement

De-identified data will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: LMA and MB; Investigation: EG, IR, and DLT; Data curation: EC; Project administration: FC and MC.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosures

The authors declare no competing interests.