Introduction

This paper compares the historical trajectories of different types of democratic innovations across space and time in the UK. It compares the design, use, and impact of referendums, mini-publics, collaborative governance (CG), and participatory budgeting (PB) (Elstub and Escobar Reference Elstub, Escobar, Elstub and Escobar2019). This is an interesting country for longer-term geographical analysis. First, the UK has traditionally been considered an inhospitable environment for democratic innovation because of its highly centralised institutional terrain and associated elitist political culture (Davidson and Elstub Reference Davidson and Elstub2014). Second, the UK has experienced asymmetrical decentralisation of many legislative powers from national to subnational governments and legislatures (Arnott Reference Arnott2024). Third, these changes have taken place during a period of democratic backsliding characterised by declining voter turnout, political party membership, and trust and increased political polarisation and citizen dissatisfaction, which has created space for the emergence of populism (Clarke, Jennings, Moss et al. Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2016). This paper considers the extent to which these three broad dynamics are interrelated by charting the trajectory of four democratic innovations across space (four different countries of the UK) and time (from the 1970s to the present). It assesses what is being transferred across the UK, the reasons for the transfer, and its varying effects on citizens’ opportunities to engage in meaningful participation and deliberation in UK politics. We find that, after decades of limited development, there has been an increase in democratic innovations across some parts of the UK in the 21st century. This roll out has also been asymmetrical, with the trajectories of each democratic innovation varying across the four nations. We argue that the importance of these differences should not be overstated in relation to democratic deepening. We conclude that, for democratic innovations in the UK to be progressed in a meaningful and coordinated manner, a constitutional convention is required to consider their use and the rules for their instigation, regulation, and outcomes.

Defining democratic innovations

Previously, Elstub and Escobar (Reference Elstub, Escobar, Elstub and Escobar2019: 11) wrote that ‘democratic innovation has become a buzzword’. The intensity of this buzz shows no sign of abating and is particularly resonant in the UK. In this paper we seek to understand whether this trend has led to meaningful political change in the UK. By democratic innovations we mean ‘processes or institutions that are new to a policy issue, policy role, or level of governance, and developed to reimagine and deepen the role of citizens in governance processes by increasing opportunities for participation, deliberation and influence’ (Elstub and Escobar Reference Elstub, Escobar, Elstub and Escobar2019: 11).

While building on previous definitions of democratic innovations (Smith Reference Smith2009; Geissel Reference Geissel, Geissel and Newton2012), this definition resolves four concerns. First, ‘innovation’ implies some improvement, and this definition provides clear criteria of ‘increasing opportunities for participation, deliberation and influence’ to assess whether improvement has occurred. Our approach to democratic innovation is then inspired and directed by the theories of participatory and deliberative democracy (Elstub Reference Elstub, Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge and Warren2018). Second, previous work on democratic innovations has stressed the importance of context for identifying whether something is new. This definition clearly specifies the relevant contexts of ‘policy issue, policy role, or level of governance’ that would qualify. Third, there is a clear steer on what should not be classified as a democratic innovation, eg, electoral reforms, as this does not ‘reimagine and deepen the role of citizens.’ Fourth, by including ‘processes or institutions’, the definition encompasses less formalised innovations as well as those in politics and governance, thereby finding a balance between previous definitions that were either too restrictive (Smith Reference Smith2009) or encompassing (Geissel Reference Geissel, Geissel and Newton2012).

From this definition, Elstub and Escobar (Reference Elstub, Escobar, Elstub and Escobar2019) develop four families of democratic innovations: referendums and citizens’ initiatives, mini-publics, CG, and PB. These are clusters of democratic innovations that share family resemblances in relation to participant selection method, mode of participation, mode of decision-making, and extent of power and authority. Referendums enable citizens to vote on issues and citizens’ initiatives to set the agenda for these ballots (Qvortrup Reference Qvortrup2015). Mini-publics select participants through sortition and aim to make decisions through deliberation (Elstub Reference Elstub, Elstub and McLaverty2014). The family of CG entails processes and forums that enable cooperation and coproduction between citizens, public authorities, and stakeholders (Bussu Reference Bussu, Elstub and Escobar2019). PB enables members of the public to propose, deliberate, and decide on public spending (Escobar Reference Escobar, Loeffler and Bovaird2020).

Democracy in the UK

While democratic innovations are extensively researched in the UK, this has primarily focused on cases rather than a macro-overview of trajectories in the field. One of the exceptions is Davidson and Elstub (Reference Davidson and Elstub2014), who assess developments in deliberative and participatory democracy during the Labour government (1997–2010) and the coalition government between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats (2010–15). They conclude that, despite rhetoric from both governments about transforming democracy, developments were unambitious and uncoordinated, lacking an enabling institutional and cultural landscape. Ultimately, the UK system was too hierarchical and centralised for democratic innovations to really take hold. There are some limitations of that paper that we seek to address. It only focuses on mini-publics and PB and on a relatively narrow period, with developments prior to 1997 and after 2014 not included, and does not cover all the devolved nations. The analysis of trajectories across space and time is therefore limited.

In relation to space, one of the primary constitutional changes introduced by the New Labour government in 1997 to decentralise power was devolution,Footnote 1 where legislative powers on certain issues were devolved to parliaments in Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. Devolution represented a significant change with many, consequently, describing the UK as ‘quasi-federal’ system (Chaney Reference Chaney2012). Devolution has been asymmetrical, with each parliament being given different levels of power over different policy issues – although these asymmetries have been diminishing as devolution settlements have evolved (Arnott Reference Arnott2024). Mitchell (Reference Mitchell2010) argues that we need to avoid a ‘narcissism of small differences’ when comparing devolved parliaments and Westminster. With respect to democratic innovations Davidson and Elstub (Reference Davidson and Elstub2014: 374) conclude that ‘devolution has simply transferred power from elite to elite and has failed to open up decision-making processes to citizens.’

Nevertheless, devolution has progressed further in the last decade, with more powers being transferred to the national parliaments (Arnott Reference Arnott2024) and through the establishment of ‘metro mayors’ and regional governments in England (Giovannini Reference Giovannini2021). It is certainly the case that local government has also been an important space relating to the trajectories of democratic innovations in the UK (Stewart Reference Stewart1996), and we highlight the key trends for each type. However, the nature of local government has also varied considerably across the different nations of the UK because of devolution (Jeffery Reference Jeffery2006). This is why the devolved nations is the primary focus of spacial analysis.

Regarding time, our analysis starts in the 1970s, when we see democratic innovations emerge in the UK. Since that decade, British citizens have become increasingly disenchanted and disillusioned with the political system’s capacity to deliver public goods (Clarke, Jennings, Moss et al. Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2016; Renwick, Lauderdale, and Russell Reference Renwick, Lauderdale and Russell2023), leading to democratic backsliding as people reduce their engagement with institutions such as elections, political parties, and parliaments. This decline in trust in political elites and institutions has been exploited by populists with the rise of political parties such as the UK Independence party and Reform UK. Yet, in the UK populists have been prominent within established and mainstream political parties too (Flinders Reference Flinders2020). Their rise to power has seen attempts to undermine British democracy further (James Reference James2023; Coulter, McKee, Pannell et al. Reference Coulter, McKee, Pannell and Sargeant2024).

Factors behind rising antipolitics in the UK are related to similar trends in other countries. First, citizens have become increasingly critical and keen to have a say and be heard in politics as their education and material levels have risen. Second, the capacity of the political system to deliver democratic control has been severely diminished because of depoliticisation, where public functions that used to be undertaken by the state are fulfilled by other organisations that are not subject to democratic authorisation (Hay Reference Hay2007; Flinders Reference Flinders2008). Third, the mediatisation of British politics has led to a decline in the quality of political communication, which alienates the public further (Clarke, Jennings, Moss et al. Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2016).

It is in this context of democratic backsliding that we have seen the growth of democratic innovations.

Trajectories of democratic innovations in the UK

This article contributes to the Special Issue on Trajectories of Democratic Innovations by charting how four families of democratic innovations have advanced in the UK. We follow the premise of the collection by understanding ‘trajectories’ as comprising key factors and evolving dynamics that mark the development of democratic innovations in space and time within a given country. Accordingly, we pay attention to the origins, contingencies, and patterns of dissemination of democratic innovations across the four constitutive parts of the UK (space) during the last five decades (time).

Referendums

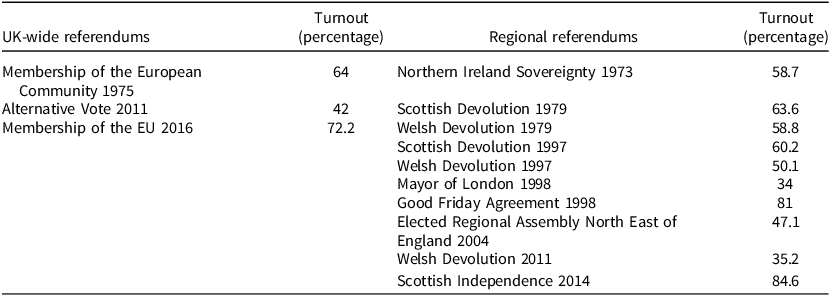

This section highlights trends about the sequence of UK referendums, topics, and voter turnout across our period of study at the UK and devolved level. As presented in Table 1, referendums in the UK started, in earnest, in the 1970s.Footnote 2 These cases were primarily instigated to avoid party splits (Qvortrup Reference Qvortrup2015). After four referendums in that decade there was a break under Conservative governments with none until New Labour in 1997, with various referendums central to their manifesto. More recently the Conservative party has become more accustomed to referendums, initially, as a compromise with the Liberal Democrats to consult on electoral reform in 2011, followed by the Scottish Independence referendum in 2014 and the Brexit referendum in 2016, the latter case being a return to the motivation behind the 1970s referendums, ie, to address party splits. Overall, there has been limited use of referendums – with only 3 UK-wide votes and 10 within the regions – especially compared with countries such as Ireland and Switzerland.

Table 1. National and regional referendums in the UK

Source: Electoral Commission.

There is greater use of referendums at the local level. Again, starting in the 1970s, the Local Government Act 1972 enabled citizens to initiate referendums in parish councils (the most local level of government in the UK at the time). Building on this through the Local Government Act 2003, local authorities in England and Wales were given powers to have nonbinding polls on issues such as service provision and council tax (Qvortrup Reference Qvortrup2015).

Three issues have dominated the UK’s referendum agenda, with European Union (EU) membership dominating the UK cases and national independence and devolution being the primary focus of the regional ones. Gordon (Reference Gordon2020) highlights the importance of focusing on occasions when referendums in the UK have not been held and details the EU and devolution legislation as passed without a public ballot.

Voter turnout is pivotal to the legitimacy of a referendum. Table 1 details the voter turnout at each. It is apparent that this varies depending on context, such as the salience of the issue to the electorate and the predictability of the outcome. Laycock (Reference Laycock2013) demonstrates how voting and campaigns in UK referendums differs to voting in elections. Firstly, party cues and identification are weaker influences on the vote in referendums. Party cues are less consistent in referendums than elections. Voters are also less likely to use a referendum vote to punish the government than in an election. Ultimately, campaigns matter more in referendums than elections in terms of influencing how people vote, especially if the campaigns are intense. Issue preference of voters is the key determinator, without being definitive. Despite their influence, UK referendum campaigns are generally thought to be low quality and not deliberative, include misleading and inaccurate information, and ultimately fail to enable voters to make informed choices, and the Electoral Commission does not have powers to intervene (Qvortrup Reference Qvortrup2015; Organ Reference Organ2019). The campaigns in the 2016 Brexit referendum are seen by some to be particularly divisive (Organ Reference Organ2019) and have led to continued polarisation among the public and politicians (Henderson, Jeffery, Wincott et al. Reference Henderson, Jeffery, Wincott and Jones2017). This highly controversial referendum may have dampened some enthusiasm or ‘accommodation’ for referendums in the UK precisely because it has shown they are not always benign instruments (Gordon Reference Gordon2020), but it is also hard to envision significant legislation on fundamental constitutional issues being passed in the UK without one because of these precedents.

To further understand the nature of referendums in the UK, we can employ institutional forms to analyse them. Legally referendums can be preregulated, where constitutional rules require them, or ad hoc, where they are discretional (Setälä Reference Setälä2006). The British referendums have all been ad hoc without ‘clear criteria which defined when a referendum would (or would not) be held’ (Gordon Reference Gordon2020: 214). This is starting to change via legislation to preregulate their use. For example, the European Union Act 2011 (now repealed because of Brexit) required changes to the powers of the EU to be subject to a referendum, and acts have been passed which require any change to the status of Northern Ireland, Scotland, or Wales to be put to a referendum (Gordon Reference Gordon2020).

A further distinction is between ‘decision-promoting referendums’, where the same political actor instigates and sets the agenda for the referendum, and ‘decision-controlling referendums’, where these roles are divided (Setälä Reference Setälä2006). In the UK they are the former and are controlled by the government, reducing their potential to deepen democracy, as ‘when governments control the referendum, they will tend to use it only when they expect to win’ (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1984: 203). There is therefore a case for introducing citizens’ initiatives to enable the UK public to influence the political agenda and make the use of referendums less top down.

Referendums can also be advisory or make binding decisions (Setälä Reference Setälä2006). In the UK, referendums are advisory. The exception was the referendum on electoral reform, as the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act 2011 made it a ‘binding referendum’.Footnote 3 Politically, though, it is very difficult for parliaments to ignore referendum results, even in the UK (Coulter, McKee, Pannell et al. Reference Coulter, McKee, Pannell and Sargeant2024).

Clearly, there is scope to go further in passing referendum legislation to embed and regularise this democratic innovation in the UK political system to make their use less ad hoc (Gordon Reference Gordon2020). This could include legislation on when to have referendums; how the campaigns are conducted to instil deliberation (Organ Reference Organ2019), including regulations on campaign funding; how the results are implemented; and whether there are rules on turnout and the size of the majority required. Organ (Reference Organ2019) also advocates for the use of mandated citizens’ assemblies (CA) in the campaigns to help inform voters. It is to a consideration of mini-publics to which we now turn.

Mini-publics

Mini-publics emerged in the UK in the 1990s, but the historical trajectory across space and time also varies according to type. The most prevalent types of mini-publics have been deliberative polls (DP), citizens’ juries (CJ), and CA. We consider the trajectory of each type in turn.

In some respects, the UK has been a global leader in the use of mini-publics, most notably the DP format (which have larger and more statistically representative participant samples but also tend to be shorter in duration and culminate in an aggregation of participants’ opinion). The world’s first DP was in the UK in 1994 on crime where proof of concept was achieved (Davidson and Elstub Reference Davidson and Elstub2014). To date, the UK is level with Japan as the country to have the second most DPs (8), behind only the USA, who are way out front (60). The most recent addressed immigration and regulation post-Brexit (Curtis, Davies, Fishkin et al. Reference Curtis, Davies, Fishkin, Ford and Siu2021), making it the only DP in the UK since 2010 despite their continuing dispersion around the globe.Footnote 4

There are several causes of this fate. First, the DP model is copyrighted, placing barriers to replication and institutionalisation. Second, UK DPs were only ever loosely connected to existing political and administrative institutions, and this meant they failed to achieve any real impact, which has affected their status. Third, the first few DPs were partly broadcast on national television, demonstrating the interest in the format. The fact that this level of media coverage was not extended to the subsequent cases indicates that this interest has waned (Davidson and Elstub Reference Davidson and Elstub2014). Fourth, as we will see below, the DP model has been surpassed by other mini-public forms in the UK.

CJs (which have a fewer number of participants than DPs but often last longer and culminate in agreed upon policy proposals) started in the UK at a similar time in 1996 and became established ‘in a remarkably short space of time’ (Delap Reference Delap2001: 39). Considerably cheaper and easier to replicate than DPs, there have been hundreds of cases; they are especially run by local authorities and public agencies on an array of policy issues, with a concentration in health initially (Delap Reference Delap2001: 39) and climate more recently. Furthermore, the New Labour government used CJs to inform their own policy,Footnote 5 and Gordon Brown argued they should be used more by local government (Davidson and Elstub Reference Davidson and Elstub2014).

CJs in the UK have varied greatly in policy influence, as they have nearly all been ad hoc, which promotes cherry-picking of recommendations (Elstub and Khoban Reference Elstub and Khoban2023). There are some exceptions. There has been a permanent CJ since 2002 offering proposals on moral and ethical issues in the National Institute for Clinical Health Excellence (NICE), a nongovernmental agency that produces clinical guidelines on new interventions (Rawlins Reference Rawlins2015) as part of the governance-driven democracy (Warren Reference Warren2009) response to depoliticisation. Having run several ad hoc CJs since 2019, the Scottish parliament is seeking to embed these processes within its committee system (Elstub Reference Elstub, Schwarzmantel and Beetham2024).

The CA format is also increasingly popular in the UK, especially on the topic of climate change (King and Wilson Reference King and Wilson2023).Footnote 6 A CA tends to have the larger number of participants that characterise DPs and last even longer than CJs. Since the first CA on regional devolution in England in 2016,Footnote 7 they have been used often by local governments. At this level, they usually have fewer participants and a shorter duration, so the distinction between CAs and CJs is narrowing, and the format of the CA stretching and diluting. One of the reasons why CAs have been so popular in the UK is the country’s proximity to Ireland, where high-profile CAs occurred on same-sex marriage and abortion between 2012 and 2018.

CAs are also used at the national and regional levels, especially by legislatures. The UK parliament and all the regional parliaments have commissioned, or have run, some form of CA/CJ in recent years. The influence of these CAs has been variable because of their largely ad hoc nature. There has also been a turn towards institutionalisation of CAs to address this. Firstly, in public administration in England, as another consequence of depoliticisation, via NHS Citizen a CJ and CA were used in conjunction with other participatory processes. NHS Citizen did not last more than one iteration though (Dean, Boswell, and Smith Reference Dean, Boswell and Smith2020). More recently, some councils in London (Newham and Camden) are seeking to imbed CAs into their governance structures following some ad hoc cases. The most ambitious plans for institutionalisation of CAs are from the Scottish government (2022), although these have not yet been implemented.

The UK has been a world leader in mini-publics with respect to the number of cases and in some aspects of their design. However, the mechanisms to afford them impact and publicity have been variable and limited. Some attempts at institutionalisation are occurring, but this agenda is in its infancy and is yet to address these weaknesses.

CG

CG is arguably the most populous family of democratic innovations in the UK and possibly worldwide. Much democratic innovation emerges in public administrations and governance networks, rather than traditional political arenas – as per Warren’s (Reference Warren2009) ‘governance-driven democratisation’ thesis. From this perspective, CG aims to compensate for loss of legitimacy in electoral democracy by seeking legitimacy ‘issue by issue, policy by policy, and constituency by constituency’ (Warren Reference Warren2009: 7 – 8). CG thus features great internal diversity (Bussu Reference Bussu, Elstub and Escobar2019; Elstub and Escobar Reference Elstub, Escobar, Elstub and Escobar2019: 27), encompassing public forums and partnerships where citizens assemble with organisational or institutional stakeholders to collaborate in the pursuit of public or common goods.

In the UK, CG can be traced to urban regeneration, community development, and environmental governance in the 1970s, but the turning point was the New Labour era. In the 1990s, the (New) Labour party experimented with pilots in England and Scotland, seeking ‘greater empowerment and involvement by communities in the affairs of local authorities’ while addressing the fragmentation of public services by neoliberal reforms in the 1980s (Lloyd, Coles, Peel et al. Reference Lloyd, Coles, Peel and Houghton2006: 3). CG was thus propelled by ‘Third Way politics’ and the ‘Communitarian Turn’ that emphasised participatory governance, public deliberation, active citizenship, decentralisation, and ‘new forms of partnership’ (Kennett Reference Kennett and Osborne2010: 23).

The 1997 New Labour government made such partnerships central to ‘the “modernisation” and “democratic renewal” of British public services’ (Sullivan and Lowndes Reference Sullivan and Lowndes2004: 51), turbocharging their proliferation across policy areas and levels of governance. Sullivan and Skelcher (Reference Sullivan and Skelcher2002: 24–27) estimated 5,500 partnerships just at the local level and spending £4.3bn annually. CG partnerships may be temporary or ongoing and have a geographic or thematic focus covering issues such as ‘urban regeneration, children’s and young people’s services, community safety, employment, education, environmental sustainability and health care’ (Sullivan and Lowndes Reference Sullivan and Lowndes2004: 52).

The institutionalisation of CG spread across the four UK nations as devolution gained pace (see Sinclair Reference Sinclair2008: 374). England and Wales saw the Local Government Act 2000 prescribing a new power of ‘community wellbeing’ and mandating ‘community strategies’. This generated local strategic partnerships in England and community strategy partnerships in Wales. In Scotland, social inclusion partnerships were succeeded by community planning partnerships in the Local Government in Scotland Act 2003. In Northern Ireland, local strategy partnerships eventually turned into community planning partnerships following the Scottish model. Despite idiosyncrasies, these partnerships converged in aims and form because of New Labour’s leading or co-leading administrations across the UK during this period (Sinclair Reference Sinclair2008: 385).

Subsequent administrations reformed these arrangements. In Scotland, the Community Empowerment Act 2015 sought to strengthen them with some successes (Weakley and Escobar Reference Weakley and Escobar2018). In England, Conservative governments since 2010 (first in coalition with Liberal Democrats) recoiled from centrally mandated partnerships to allow local approaches while watering down participatory mechanisms that connected local and national governance (Bua and Escobar Reference Bua and Escobar2018). In Northern Ireland, community planning partnerships were further developed since the Local Government Act (NI) 2014.

These partnerships are not the only forums in the CG family of democratic innovations, but they were given legislative basis and covered numerous policy areas. Citizens, at least in theory, could participate in governance through ‘new spaces within which citizens and officials meet together to deliberate, make and review policy’ (Barnes, Reference Barnes, Barnes and Prior2009: 33). Assessing the success of these partnerships is difficult. They were introduced as strategies to counter democratic deficits, deal with complex issues, increase problem-solving capacity, foster social capital, improve public services, and restore legitimacy to policy-making. Researchers usually point to mixed and highly contingent results (eg Barnes, Newman, and Sullivan Reference Barnes, Newman and Sullivan2007; Weakley and Escobar Reference Weakley and Escobar2018; Sullivan Reference Sullivan2022). From a democratic innovations perspective, have they contributed to reimagining and deepening the role of citizens? Four tensions have troubled this agenda.

First, mandated CG processes are riddled with power inequalities. In these democratic innovations, citizens and officials are meant to work as ‘partners’, but power-sharing has been limited (Barnes, Newman, and Sullivan Reference Barnes, Newman and Sullivan2007; Sullivan Reference Sullivan2022). Second, CG uncovers tensions between technocratic and democratic imaginaries of governance and their underlying managerial, organisational, and political rationales. Some partners’ motivation is to improve efficiency and effectiveness in policy, whereas others seek to deepen public participation and community empowerment – aims often at odds in practice (eg Sullivan and Lowndes Reference Sullivan and Lowndes2004; Barnes and Prior Reference Barnes and Prior2009). Third, CG is another arena where participatory and representative politics are in tension. Politicians undertake ambiguous roles, as partnerships usually have unclear relations with representative institutions. Finally, the ‘network governance’ logic of these democratic innovations often clashes with the command-and-control culture of politics and public administration in the UK – a highly centralised and elitist system of governance (Cairney, Boswell, Ayres et al. Reference Cairney, Boswell, Ayres, Durose, Elliott, Flinders, Martin and Richardson2024).

These tensions must be placed in the broader context of the new public management reforms carried out by successive governments in the UK since the 1980s, and the concomitant depoliticisation of key areas of public administration (Flinders Reference Flinders2008). Depoliticisation refers to the ‘transfer of functions away from elected politicians’ and the distancing of public governance from traditional democratic control and accountability, which became ‘the dominant model of statecraft’ in the UK by the turn of the century (Flinders and Wood Reference Flinders, Wood, Flinders and Wood2015: 2; Hay Reference Hay2007). The proliferation of CG arrangements can be understood against this backdrop, which opened spaces for democratic innovation – insofar as governance-driven democratisation required new legitimation processes, as without the administrators being elected, there was an absence of principal–agent bonds with the public (Warren Reference Warren2009) – but also imbued them with the tensions outlined above.

In sum, CG has generated myriad interfaces between citizens and authorities across policy arenas and public services, providing new spaces for collaboration and contestation. As Barnes (Reference Barnes, Barnes and Prior2009: 48) argues, the ‘objective of the “empowerment” of citizens is too simplistic but nor is it useful to understand these forums simply as another place in which officials exercise power over citizens’. Although early hopes are tempered, CG continues to pursue ‘a new set of relationships between government, communities, and citizens’ across the UK (Barnes and Prior Reference Barnes and Prior2009: 5).

PB

The UK was an early adopter of PB in Europe (Röcke Reference Röcke2014). The idea travelled from Brazil via activists and community workers through visits in the 1990s and the World Social Forum in Porto Alegre in 2001 (Jackson Reference Jackson and Graham2011: 96; Escobar, Garven, Harkins et al. Reference Escobar, Garven, Harkins, Glazik, Cameron, Stoddart and Dias2018: 314). PB enables citizens to participate in deciding the allocation of public or community budgets, including the development and scrutiny of proposals and monitoring of implementation (Escobar Reference Escobar, Loeffler and Bovaird2020). This makes PB a unique family of democratic innovations insofar as participation is inextricable from direct mobilisation of resources.

The UK history of PB reflects the interplay – collaborative and agonistic – between civil society and public authorities. Civil society organisations (ie community groups, anti-poverty charities, churches) started pilots and advocated PB’s potential to support social justice and democratic renewal. In the mid-2000s the New Labour government linked PB to decentralisation and community empowerment, resulting in the 2008 National Strategy for Participatory Budgeting, alongside legislation for a ‘duty to involve’ (Jackson Reference Jackson and Graham2011: 97). The PB Unit was funded by the Ministry of Community and Local Government and outsourced to Church Action on Poverty. The Home Office funded 20 pilots in 2008, and the UK government declared that all local authorities would feature PB by 2012 (Jackson Reference Jackson and Graham2011: 97–98). This policy context helped build capacity and a community of practice that would become instrumental to develop PB across the four nations (Hall Reference Hall, Dias, Enriquez, Cardita, Julio and Serrano2021: 209).

The two decades of UK PB maps onto ebbs and flows in the four nations. The first decade advanced PB in England and introduced it in Wales, while the second ushered PB in Scotland and later Northern Ireland (Dias, Enriquez, Cardita et al. Reference Dias, Enriquez, Cardita, Julio and Serrano2021). By 2010 there were 65 processes in England, with another 100 local areas planning to start PB (Jackson Reference Jackson and Graham2011: 96). The importance of New Labour’s support became patent when the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition took power in 2010 and the PB agenda waned down in England – although some authorities and civil society organisations continued to carry the PB torch (Hall Reference Hall, Dias, Enriquez, Cardita, Julio and Serrano2021: 209). Although Wales had pilots, PB never took off as in England, albeit the Welsh government has reconsidered rekindling this agenda (Williams, St Denny, and Bristow Reference Williams, St Denny and Bristow2017). In Northern Ireland, PB gained momentum since 2017 (Jackson Reference Jackson and Graham2011: 96) via housing associations, community planning partnerships, and the PB Works network – supported by practitioners from England and Scotland (O’Kane Reference O’Kane, Dias, Enriquez, Cardita, Julio and Serrano2021).

PB proliferated in Scotland from 2010 drawing on expertise from England. Civil society organisations, researchers, and reform commissions advocated PB, and the 2014 Independence Referendum provided fertile ground steeped in discourses of community empowerment and democratic renewal (Escobar, Garven, Harkins et al. Reference Escobar, Garven, Harkins, Glazik, Cameron, Stoddart and Dias2018). The Scottish government, led by the Scottish National Party, launched the Community Choices Fund to develop PB with local authorities and community organisations. This was supported by creating PB Scotland and the PB Charter and by policy developments such as the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015. By 2016, PB was a core commitment in Scotland’s National Action Plan to join the Open Government Partnership. It went from few cases before 2010 to over 200 by 2018 (Escobar, Garven, Harkins et al. Reference Escobar, Garven, Harkins, Glazik, Cameron, Stoddart and Dias2018: 314). Scottish government investment totalled £6.5m, match-funded by local authorities (£5m) and supported by other institutions and community organisations (Escobar and Katz Reference Escobar and Katz2018: 4; Escobar, Garven, Harkins et al. Reference Escobar, Garven, Harkins, Glazik, Cameron, Stoddart and Dias2018: 319). This developed a community of practice of 1,300 PB organisers and enabled participation by 122,000 citizens (National Participatory Budgeting Strategic Group 2021). Since 2017, the Scottish government and the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities agreed to allocate ‘at least 1% of local government budgets’ via PB – an estimated £100m (Escobar and Katz Reference Escobar and Katz2018: 5). A first milestone was reached in 2023, with 1.4% spent (£154m).Footnote 8

This trajectory illustrates how democratic innovations can develop apace through the interplay between civil society and public institutions. It also shows the fragility that stems from dependence on the support of a particular administration. UK PB is criticised for lacking radical ambition and the level of investment and impact seen elsewhere (Röcke Reference Röcke2014; Williams, St Denny, and Bristow Reference Williams, St Denny and Bristow2017; Escobar Reference Escobar, Loeffler and Bovaird2020). PB was adapted to the UK context of the early 2000s so that it could be piloted in civil society (Hall Reference Hall, Dias, Enriquez, Cardita, Julio and Serrano2021: 206). This generated the ‘participatory grant-making’ model featuring small funds for community projects – different from models that allocate larger mainstream public budgets (PB Partners 2016a; 2016b; Escobar and Katz Reference Escobar and Katz2018). Path-dependency ensued, and despite exceptions, most PB has been of this nature (DCLG 2011; Röcke Reference Röcke2014), albeit there are efforts to mainstream PB, particularly in Scotland (Escobar Reference Escobar, Loeffler and Bovaird2020). Along the way, PB organisers have faced cultural, political, capacity, and sustainability challenges now exacerbated by the mainstreaming agenda (Escobar and Katz Reference Escobar and Katz2018: 5).

Evaluations have documented positive results that are commensurate with relatively small investments (eg DCLG 2011; O’Hagan, Hill-O’Connor, MacRae et al. Reference O’Hagan, Hill-O’Connor, MacRae and Teedon2019; Harkins, Moore, and Escobar, Reference Harkins, Moore and Escobar2016). PB has improved citizen participation by mobilising resources towards community priorities across policy areas and public services. Nonetheless, this has not amounted to transformative impacts in outcomes for citizens or in democratising the governance of public budgets (Escobar Reference Escobar, Loeffler and Bovaird2020). Lessons from these two decades, sustained through civil society practice and institutional capacity-building, suggest that these democratic innovations have not reached their potential, but have perhaps laid groundwork for PB of greater potency.

Discussion and conclusions: The future of democratic innovations in the UK

We have sketched out contemporary UK trajectories of democratic innovations in space and time. The four families encompass participatory and deliberative processes across different policy areas and levels of governance. They illustrate diverse origins, development pathways, and forms of institutionalisation, showing asymmetries of democratic innovation across the UK’s four nations. Some evolution timelines were simultaneous (eg CG and mini-publics), while others were consecutive (eg PB and referendums), showing differentiation between processes supported by central UK institutions and those that followed their own path in devolved administrations and local government. We also illustrated the transfer of ideas and practices across civil society and institutions within and across the four nations. By our account, England and Scotland have opened more space for these democratic innovations than Wales and Northern Ireland, but all developed initiatives and advanced the field within the affordances and constraints of their political contexts.

These asymmetries should not be overstated. Discourses of public participation, community empowerment, and democratic renewal have been similar. Regarding practices, the isomorphism of some of these democratic innovations is striking. For example, the ubiquitousness of ‘partnerships’ as the quintessential form of CG or the prevalence of ‘grant-making’ PB, although the drivers of that isomorphism differ – ie CG was shaped by central UK government’s new public management reforms, while PB owes this to the interplay with civil society, devolved administrations, and local government. A key trend across the decades and regions for democratic innovations in the UK has been depoliticisation, and it therefore represents a good case of governance-driven democratisation (Warren Reference Warren2009). Some of these democratic innovations were propelled by institutionalisation (eg CG and PB), while others are in the early stages of that process (eg mini-publics and referendums). There are thus transferable lessons, such as the challenges emanating from the contradictions and power inequalities in centrally mandated CG partnerships, or from the dependence of PB on a particular administration.

We also identified a political party dynamic, with left-of-centre parties such as Labour and the Scottish National Party being more likely to support democratic innovations over time. The exception to this could be referendums, with the Conservatives having initiated the last three, and Reform UK making this democratic innovation a central part of its 2024 election manifesto. At that election, the Labour Party returned to government after 14 years in opposition, and we shall see whether this is a catalyst for further democratic innovation. One year on, it has not been so far.

In historical terms, this contemporary wave of democratic innovation is in its early stages, and each family continues to generate possibilities. Some recent developments are illustrative. Mini-publics are being incorporated into legislatures such as the Scottish Parliament (Elstub Reference Elstub, Schwarzmantel and Beetham2024), which promises new insight about the interface between participatory-deliberative processes and representative-deliberative institutions. Green PB is being developed in the northeast of Scotland, where PB is part of ‘just transition investment’ for this oil-dependent region.Footnote 9 Climate assemblies, particularly in local authorities, are another vibrant field stimulated by the imperatives of the climate and ecological crises (Escobar and Elstub Reference Escobar and Elstub2025).Footnote 10 Digitalisation has become an important trend, accelerated by the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic and generating new civic tech to support PB and mini-publics. There is more constitutional legislation than ever before that requires a referendum to amend (Gordon Reference Gordon2020) and even calls in parliament for the introduction of citizens’ initiatives.Footnote 11

CG continues expanding, for example, through community wealth-building programmes and public-commons partnerships that contest the neoliberal agenda of the new public management era.Footnote 12 These new forms of CG join the powers of the state and the commons in areas such as housing, energy, public services, and economic development, thus addressing a conspicuous gap: the need for democratic innovations focused on economic policy-making and governance (Vlahos, Bua, and Gagnon Reference Vlahos, Bua and Gagnon2024). This gap is troubling when many needs, priorities, and aspirations of UK citizens relate to persistent and growing socioeconomic inequalities (Dorling Reference Dorling2023). Moreover, new economic activities (eg infotech, biotech, artificial intelligence [AI]) exacerbate inequalities and challenge democratic governance (Vallor Reference Vallor2020). The field of democratic innovation must therefore engage more substantially with the political economy of contemporary capitalism.

The UK has made progress in this field, but democratic innovation has not yet changed the fundamentals of UK democracy. Perhaps this is an unrealistic expectation from an emergent field. We outlined the challenges of democratic backsliding, public dissatisfaction, political polarisation, and authoritarian populism. It seems a tall order for relatively modest waves of democratic innovation to overturn such tidal forces. Democratic innovations have not entered the public imagination in a mediatised public sphere focused on traditional institutions and party politics (Zappettini and Krzyżanowski, Reference Zappettini and Krzyżanowski2019). Nor have they dented public dissatisfaction with democracy, albeit research indicates citizens’ openness to new forms of public participation (Renwick, Lauderdale, and Russell Reference Renwick, Lauderdale and Russell2023). To be part of the antidote to democratic backsliding, the scale and depth of democratic innovation must be increased. The trajectories sketched out here show capacity for learning and evolution upon which a new generation of political reformers may build.

Nevertheless, democratic innovators face entrenched structures and cultures in politics and public administration. The centralised and elitist qualities of the UK political system present perennial challenges to modest, let alone radical, reforms (Cairney, Boswell, Ayres et al. Reference Cairney, Boswell, Ayres, Durose, Elliott, Flinders, Martin and Richardson2024). Devolution of powers to Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland has been an important step, but English devolution remains underdeveloped. Likewise, decentralisation and empowerment of local government (at least comparable to other European countries) has not been meaningfully addressed – despite various ‘localism’ agendas in recent decades. The shortcomings of UK’s democratic governance are so hardwired into the institutional landscape that constitutional reform seems an unavoidable prospect to revert democratic backsliding and advance democratic renewal. A UK Constitutional Convention seems an overdue first step in this direction (Renwick and Hazell Reference Renwick and Hazell2017; White Reference White2017; King Reference King2019). It could include democratic innovations within the process of reviewing the UK constitution and formally cement democratic innovations within the UK political system (Coulter, McKee, Pannell et al. Reference Coulter, McKee, Pannell and Sargeant2024), thereby reducing the control of political elites over them by legislating on their initiation, governance, and powers. We accept that, given the highly centralised, hierarchical, and unequal nature of the UK political system, ‘root-and-branch, systematic reform proposals are unlikely to emerge’ (Coulter, McKee, Pannell et al. Reference Coulter, McKee, Pannell and Sargeant2024: 777). Rather, we make a normative point, suggesting that this should happen to improve democracy in the UK, not that it will. However, a Constitutional Convention has been on the UK political agenda. For example, it has been a commitment included in political party election manifestos (Renwick and Hazell Reference Renwick and Hazell2017), and politicians have advocated for it (White Reference White2017). Indeed, the uncodified nature of the constitutional process in the UK does leave some scope for experimentation, so democratic innovations could feature (Coulter, McKee, Pannell et al. Reference Coulter, McKee, Pannell and Sargeant2024).

This paper has provided a synopsis of key trajectories of four families of democratic innovations in the UK. Taken together and placed in historical and political context, these trajectories show important trends in the development of new participatory and deliberative processes. The paper thus contributes by mapping democratic innovations as well as patterns and challenges across the field. We have schematically illustrated similarities and differences of these trajectories across the UK, but systematic comparative analysis is now possible and necessary – given the benefit of decades of evidence behind and the urgency of democratic challenges ahead.

Politicians are concerned about low levels of trust and high levels of dissatisfaction with democracy in the UK. Some have looked to democratic innovations to help remedy this problem and make it look like they are willing to do politics differently. The next stage of democratic innovation needs to lead to them moving beyond perception and to actually doing politics differently by sharing substantial power with citizens.

Data availability statement

There are no data associated with this paper.

Competing interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.