Introduction

When people experience fear, their appraisal tendencies change towards more protective behaviours, and they perceive threats and risk more pessimistically (Druckman & McDermott, Reference Druckman and McDermott2008; Lerner & Keltner, Reference Lerner and Keltner2000; Lerner et al., Reference Lerner, Gonzalez, Small and Fischhoff2003). The number of people rapidly infected with the virus causing COVID‐19, and the high death toll that followed, increased fear and intensified anxieties among the public (Ahorsu et al., Reference Ahorsu, Lin, Imani, Saffari, Griffiths and Pakpour2020; Degerman et al., Reference Degerman, Flinders and Johnson2020). Widespread lack of information, such as the one individuals experienced during the early stages of the pandemic, can trigger a psychological need for certainty, defensive reactions, and a strong desire for security (Jonas et al., Reference Jonas, McGregor, Klackl, Agroskin, Fritsche, Holbrook, Nash, Proulx, Quirin, Olson and Zanna2014; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Schott and Scherer2011). Research carried out during the first stage of the pandemic confirms that citizens' approval of extreme policies meant to combat the spread of Sars‐CoV‐2, but at odds with liberal democratic norms, increased (Alsan et al., Reference Alsan, Braghieri, Eichmeyer, Kim, Stantcheva and Yang2020; Amat et al., Reference Amat, Arenas, Falcó‐Gimeno and Muñoz2020; Bol et al., Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2021; Bartoš et al., Reference Bauer2021). We know much less about the effects of the pandemic beyond its peak and the potential negative effects of the fears that individuals experienced in relation to COVID‐19.

Considering the existing literature pointing to an erosion of liberal‐democratic attitudes during the pandemic, it appears critical to understand how citizens' experience with the crisis affected their support for liberal‐democratic norms. If the experience of fear and anxieties related to the pandemic would lastingly impact citizens' support for liberal democracy, we should most likely observe any such effect in the newer member states of the European Union that are most challenged in their democratic consolidation. In regimes experiencing authoritarian innovations, political elites have been more willing to centralize power during the health crisis (Rapeli & Saikkonen, Reference Rapeli and Saikkonen2020) and opt for measures more restrictive of fundamental rights (Engler et al., Reference Engler, Brunner and Loviat2021). In this context, the attitudes of citizens less committed to democratic norms could support elites' illiberal agendas. In this research note, we present empirical evidence of an original experiment conducted in two Central Eastern European countries – Romania and Hungary – one and a half years after the onset of the pandemic. Romania and Hungary are representative cases for regimes struggling with democratic consolidation (Enyedi, Reference Enyedi2020; Ganev, Reference Ganev2013). The restrictive measures required to deal with the pandemic were coupled with an accumulation of power in the hands of opportunistic incumbents with track records of illiberal agendas. This increased concerns of an erosion of democratic norms and structures (Guasti, Reference Guasti2020). The public in such post‐Communist settings also has greater tendencies towards right‐wing authoritarianism, ethnocentrism and illiberalism compared to the public in the European Union's Western half (Anghel, Reference Anghel2020; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018). In the absence of deep‐seated liberal‐democratic values among citizens, and given the illiberal agenda of governing elites, the effects of the pandemic might be lasting and particularly pronounced. To estimate the potentially erosive consequences of the pandemic on citizens' support for liberal democracy, in our study, we exogenously manipulate individuals' cognitive accessibility of fears related to COVID‐19. To do so, we exploit the transient lower salience and presence of COVID‐19 during August 2021. At this time, the number of new COVID‐19 cases and deaths hit its lowest point since the start of the pandemic (Johns Hopkins University, 2022), while the overall threat of new variants remained real (World Health Organisation and European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, 2021).

Our results show that this experimental manipulation is successful. Respondents in the treatment group experience significantly greater levels of worry, anxiety and fear when thinking about infectious diseases like COVID‐19. The results also demonstrate that these greater anxieties do not carry secondary effects on individuals' broader levels of right‐wing authoritarianism, nationalism or their outgroup hostility nor do they influence individuals' preferences for authoritarian or discriminatory policy measures aimed to fight a potential resurgence of COVID‐19. This finding holds across a range of different modelling strategies and is independent of how the various attributes of the different concepts are represented in a low‐dimensional space.

In drawing attention to the lack of negative consequences of the COVID‐19 experience on citizens' attitudes and their liberal‐democratic values in situations where we are most likely to encounter such effects, our results suggest that early concerns raised by political scientists were too pessimistic. In fact, citizens' liberal‐democratic attitudes may be more resistant to punctuated violations of liberal‐democratic norms in the wake of the COVID‐19 health crisis than previously assumed. These results contribute to a fine‐tuning of the literature related to the demand‐side determinants of democratic backsliding. Finally, the findings of our study show the limited impact of fears perceived during enduring health crises on people's culturally conservative political attitudes.

The article is organized as follows. First, we offer a concise review of the literature on the effects of fears and anxiety on individuals' political attitudes with a particular view to integrate the existing evidence on the related (early) effects of fear of COVID‐19. In doing so, we highlight the need to understand the implications of the pandemic for citizens' key liberal‐democratic attitudes beyond its initial shock. Second, we introduce our research design, aimed to understand such potentially harmful and lasting political consequences in two countries most likely to be affected due to political elites' propensity to nurture support for anti‐liberal agendas, and because of wider spread illiberal attitudes in the population. Third, we present the results of our study. We conclude by discussing the role that a strategic amplification and manipulation of anxieties by political elites may play in nurturing authoritarian attitudes among the public.

COVID‐19 and the Effects of Fear on Political Attitudes

The literature concerned with understanding the effects of emotions on political behaviour agrees that the experience of fear has important consequences on individuals' decision‐making and their political attitudes (Brader & Marcus, Reference Brader, Marcus, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013). Individuals experience fear and anxietyFootnote 1 when their emotionality reacts to certain events that are perceived as threatening, dangerous or highly novel in nature. Anxiety dominates over other emotions when individuals deal with an uncontrollable source of threat, or one that cannot be overcome (Lazarus, Reference Lazarus1991). Political scientists have studied the implications of such kinds of behaviour with respect to individuals' reaction to terrorist attacks (Albertson & Gadarian, Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015; Merolla & Zechmeister, Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2009), organized crime (Vilalta, Reference Vilalta2016), immigration (Brader et al., Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008), economic downturns (Kopasker et al., Reference Kopasker, Montagna and Bender2018), or deadly viral outbreaks (Brader & Marcus, Reference Brader, Marcus, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013; Clifford & Jerit, Reference Clifford and Jerit2018).

The global COVID‐19 pandemic led to widespread fear among the population (Ahorsu et al., Reference Ahorsu, Lin, Imani, Saffari, Griffiths and Pakpour2020), creating what some observers identified as a ‘culture of fear’ (Gruchoła & Sławek‐Czochra, Reference a and Czochra2021). The initial spread of an indiscriminate virus, coupled with individuals' lack of control over environmental conditions and their personal safety, nurtured illiberal attitudes among citizens. Potential bodily contamination triggers disgust in individuals, a powerful driver for social conservatism (Aarøe et al., Reference Aarøe, Petersen and Arceneaux2020). Studies concerned with infectious disease salience in a society demonstrate that threats related to pathogen contamination make people less extraverted and more risk‐averse (Schaller & Murray, Reference Schaller and Murray2008), more xenophobic (Faulkner et al., Reference Faulkner, Schaller, Park and Duncan2004) and more ethnocentric (Navarrete & Fessler, Reference Navarrete and Fessler2006). The acceptance of ethnic and national diversity, the prioritization of individual rights and freedoms, and the support of limited constitutional government are key liberal attitudes (Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). Studies show that the early experience of the pandemic affected these attitudes. Hartman et al. (Reference Hartman, Stocks, McKay, Miller, Levita, Martinez, Mason, McBride, Murphy, Shevlin, Bennett, Hyland, Karatzias, res and Bentall2021) show that perceptions of threat stemming from the virus causing COVID‐19 are strongly associated with nationalism, right‐wing authoritarianism and outgroup derogation in the United Kingdom and Ireland (see also Lu et al., Reference Lu, Kaushal, Huang and Gaddis2021, for similar results in the context of the United States). Filsinger and Freitag (Reference Filsinger and Freitag2022) demonstrate that reported levels of fear and worry predict authoritarian attitudes in four Western European countries (Germany, Switzerland, Italy, and the United Kingdom) during the second wave of the pandemic (late 2020 to spring 2021). Dipoppa et al. (Reference Dipoppa, Grossman and Zonszein2021) argue that the threat of infection‐triggered violence against certain minority groups, leading to an increase in hate crimes at the onset of the pandemic in Italy. Bartoš et al. (Reference Bauer2021) study citizens' early responses to the pandemic in the Czech Republic, showing that the salience of the COVID‐19 crisis increased their hostility against foreigners in a behavioural experiment.

Such findings are in line with research from political psychology, showing that individuals cope with threat by readily modifying their attitudes towards other individuals, in particular towards those who are not part of their social ingroup (Merolla & Zechmeister, Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2009). These studies also show that under conditions of a prolonged salience of infectious diseases within a society, such exclusionary norms may become culturally formalized (Bieber, Reference Bieber2022; Karwowski et al., Reference Karwowski, Kowal, Bernard, Bialek, Lebuda, Sorokowska and Sorokowski2020). Thus, it becomes important to investigate what the effects of the pandemic beyond its peak are. In unconsolidated democracies (such as Romania) or hybrid regimes (such as Hungary) – where exclusionary and illiberal tendencies are already widespread among the population – this formalization of exclusionary norms should be particularly likely in response to COVID‐19‐related anxieties. Following these arguments, we test the following hypotheses:

H1: Individuals who experience fear of COVID‐19 display higher levels of (a) right‐wing authoritarianism, (b) nationalism and (c) outgroup hostility.

Beyond affecting individuals' authoritarian, outgroup hostile or nationalist attitudes, the experience of fear of COVID‐19 might also directly shape citizens' preferences for specific policies designed to fight the spread and the resurgence of COVID‐19 through new strains and variants. Scientists agree that there is a high probability to observe pandemics similar to COVID‐19 in the coming decades (Marani et al., Reference Marani, Katul, Pan and Parolari2021). To respond to future health crises, governments might choose to implement similar mitigation measures. Policy measures used to combat the spread of COVID‐19 included not only the compulsory use of facial masks or public lockdowns and the obligation to quarantine, all of which are established approaches to handling epidemics and pandemics (Hays, Reference Hays2009). Governments across the world also proposed policies that involve infringements of individual rights (Jørgensen et al., Reference rgensen, Bor, Lindholt and Petersen2021), curtail the balance of powers (Bolleyer & Salát, Reference Bolleyer and t2021) and could challenge the fundamentals of democratic rule (Goetz & Martinsen, Reference Goetz and Martinsen2021). Several studies document that citizens' approval of extreme policies meant to combat the spread of the virus, but at odds with liberal democratic norms, increased under the impression of fear and anxiety at the height of the pandemic (Alsan et al., Reference Alsan, Braghieri, Eichmeyer, Kim, Stantcheva and Yang2020; Amat et al., Reference Amat, Arenas, Falcó‐Gimeno and Muñoz2020). Marbach et al. (Reference Marbach, Ward and Hangartner2020) demonstrate that the implementation of such policies lastingly increased authoritarian values in four Western European democracies. While in established democracies liberal democratic norms may have worked to create resistance to these illiberal policy measures to some extent (Arceneaux et al., Reference Arceneaux, Bakker and Hobolt2020), the same may not hold true in countries where liberal democratic norms are less entrenched in society. In light of these arguments, we assume that when individuals recall their fears related to the pandemic, they are more likely to support illiberal policy measures aimed at containing the spread of the virus that include discriminatory practices. The emotional experience of fear related to COVID‐19 may directly affect their policy preferences should a similar threat re‐emerge. Thus, we test the following hypotheses:

H2: When under conditions of fear of COVID‐19, individuals are more likely to approve of (a) authoritarian, (b) nationalist and (c) outgroup‐hostile policies related to COVID‐19.

Research Design

To test our hypotheses, we draw on an original experimental design that allows us to exogenously manipulate the cognitive accessibility of fear of COVID‐19.Footnote 2 The timing of the study is critical. The pandemic was central in people's decision‐making processes during its onset (Bol et al., Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2021). By August 2021, the dominance of health concerns in the minds of most citizens reduced significantly. The number of new COVID‐19 cases and deaths hit its lowest point since the start of the pandemic (Johns Hopkins University, 2022), while the more contagious COVID‐19 Omicron variant was still to be reported. Across most European countries, including Romania and Hungary, the society and the economy reopened with restrictions partially lifted and the vaccination campaign was underway. Citizens resumed pre‐pandemic practices like holiday travelling or returning to their offices for work.Footnote 3 At the same time, scientists urged to maintain efforts to prevent transmission (World Health Organisation and European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, 2021), warning that new waves no less harmful might hit countries during autumn and winter. As governments maintained the state of emergency, further restrictions on individual rights and elite manipulations of democratic norms and structures continued to be a possibility.

These conditions are favourable to experimentally study whether the anxieties that individuals experienced due to the pandemic have downstream consequences for their political attitudes and their authoritarian inclinations. They allow us to manipulate the cognitive accessibility of individuals' fears related to the pandemic in a random subset of the sample. To do so, half of the respondents recall and describe their fears in open‐ended questions (i.e., we apply a ‘bottom‐up’ approach to induce fear (Wagner & Morisi, Reference Wagner and Morisi2019); for similar designs, see, e.g., Kettle and Salerno, Reference Kettle and Salerno2017; Kugler et al., Reference Kugler, Connolly and ez2012; Lerner and Keltner, Reference Lerner and Keltner2000). We first ask them to share three things that made them feel afraid during the peak of the COVID‐19 pandemic, after which they describe in greater detail one situation during the COVID‐19 pandemic that made them feel most afraid.Footnote 4 Respondents are instructed to picture that situation in such a way that it would make other people feel afraid too. We deliberately avoid specifying what we consider the peak of the COVID‐19 pandemic to be, and we do not provide any specific examples of situations that could have made people afraid. This strategy aims to accommodate the variety of individual experiences which may have triggered fear and anxiety related to COVID‐19.

We field the study in two Central and Eastern European countries with low levels of democratic consolidation, Romania and Hungary. These are two most likely cases (Gerring, Reference Gerring2017) to see illiberal attitudes amplify in response to anxieties induced by the pandemic.Footnote 5 Hungary was a front‐runner of post‐communist transition that did not rise to expectations of rapid democratization and descended into authoritarianism (Magyar & Madlovics, 2020). Since 2014, the vote of a majority of the Hungarian population reconfirmed in office the party of Prime Minister Viktor Orban, Fidesz. Under PM Orban's leadership, Fidesz altered the functioning of democratic institutions as early as 2010 and pushed for an exclusionary heteronormative, white, Christian composition of the Hungarian society. Romania was considered a laggard of the transition–reflected in its late accession to the EU in 2007 – and continues to stagnate in its democratic consolidation (European Commission, 2021). Although initial concerns of Romania's descent into authoritarianism following its post‐Communist transition did not materialize, incumbents frequently challenge judicial independence and self‐servingly manipulate democratic institutions (Lacatus & Sedelmeier, 2020). Unlike the case of Hungary, Romania's illiberal elites cannot easily be linked to a single party. The population protested against obvious instances of corrupt practices, but entrenched clientelism and frequent cabinet changes have ensured the dominance of cross‐party illiberal views and practices regardless (Gherghina & Volintiru, Reference Gherghina and Volintiru2017; Protsyk & Matichescu, Reference Protsyk and Matichescu2011).

The pandemic provided Romanian and Hungarian elites with the opportunity to further pursue such agendas. The policy measures enacted by the Romanian or Hungarian governments included actions that minimized the role of courts in balancing discretionary executive actions, put the military in charge of civil objectives such as hospitals, and minimized freedom of speech to limit anti‐government dissent. In the case of Romania, it also provided government representatives with the opportunity to intensify a defamatory agenda against the Constitutional Court which ruled against COVID‐19‐related illegal government policies. These governments also endorsed policies that discriminated against minorities or immigrants. In Romania, the Roma community fell victim to brutal interventions by law enforcement (Amnesty International, 2020). Authorities pursued discriminatory policies to isolate mostly Romani communities from the rest of the population. In Hungary, observers reported hate crimes against the Asian community (Bard & Uszkiewicz, Reference Bard and Uszkiewicz2020) that were never sanctioned by Hungarian authorities. State representatives also branded foreigners or ethnic minorities as scapegoats for spreading the virus. Hungarian PM Viktor Orban declared that ‘primarily foreigners brought in the disease, and that it is spreading among foreigners’. Orban used the virus to advance his long‐established anti‐immigration policy to abolish asylum rights (Euronews, 2020). Representatives of the Romanian government urged and dissuaded citizens who lived or worked outside the country not to return to Romania (Paun, Reference Paun2020); those who did return at the start of the pandemic were forced into institutionalized confinement by an executive order soon to be struck down as unconstitutional (Romanian Constitutional Court, 2020). At the same time, mainstream media amplified politicians' racist undertones to show the influx of ethnic Romani returning from Western Europe (Chiruta, Reference Chiruta2021). We study two central outcome variables: higher level authoritarian attitudes and specific preferences for authoritarian COVID‐19 policy measures to combat the spread of the virus.Footnote 6 To test the first set of hypotheses (H1a–c), we measure respondents' authoritarian attitudes according to the six‐item ‘Very Short Authoritarianism’ (VSA) scale (Bizumic & Duckitt, Reference Bizumic and Duckitt2018). To estimate the effects of fear of COVID‐19 on nationalist attitudes, we complement this six‐item VSA scale with three more questions measuring respondents' nationalist attitudes. These questions ask respondents about their emotional attachment to their country, the importance of the birthplace as a major component of their identity (proxy for nativism) and whether they have a strong national devotion that places their own country above all others. Finally, we measure respondents' outgroup‐hostile sentiments by asking them about their approval of a set of statements related to the political rights of the diaspora, immigration by ethnic groups (of the same ‘race’ and of different ‘race'), the impact of immigration on the functioning of the economy and on the quality of life within their country, more generally. Tables S1 and S2 in the SI show the exact question wording of all items.

To test the second set of hypotheses (H2a–c) and to measure individuals’ support for COVID‐19‐specific policy measures, we ask respondents about their (dis‐)approval of a set of specific policies that were discussed in the context of the pandemic. Such policies would go against fundamental principles of liberal democracy that include institutional checks and balances on executive power, respect for the rule of law, human rights such as minority rights, and civil liberties. We broadly group these policies into three categories: authoritarian policy measures that relate to constitutional breaches or the concentration of executive power, nationalist policies that relate to the absolute prioritization of the respective country's national interests when faced with the COVID‐19 crisis, and outgroup‐hostile policies that relate to the enforcement of strict immigration policies and to outgroup‐specific limitation of freedom of movement during the pandemic. All these COVID‐19 containment policies were discussed by the Romanian or the Hungarian executives.

Results

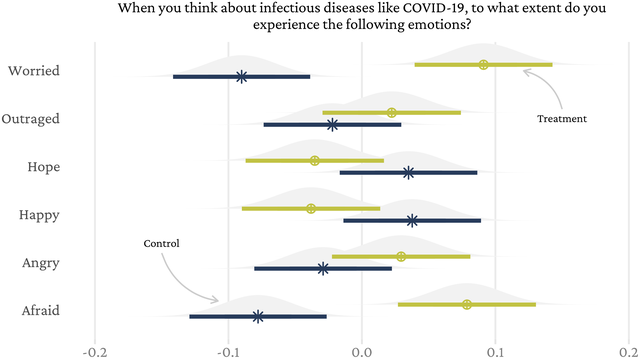

We begin by discussing the effectiveness of our fear treatment. Our recall questions in the treatment condition were meant to increase individuals' cognitive accessibility of fears and anxieties related to COVID‐19. On average, respondents spent 22 seconds answering these questions, recalling what made them feel afraid during the COVID‐19 pandemic. If our experimental manipulation was successful, we should observe that individuals in the treatment condition, on average, feel more worried and afraid when thinking about infectious diseases such as COVID‐19. To assess whether this is the case, respondents report on the feelings they experience when thinking about infectious diseases like COVID‐19. This manipulation check is included after respondents answer all the questions related to our outcome variables of interest (Kane & Barabas, Reference Kane and Barabas2019). Figure 1 shows the average levels of emotional responses among individuals in the treatment and control groups along with the respective confidence distributions around these sample means. The graph demonstrates that individuals who were assigned to the ‘fear of COVID‐19’ condition display significantly higher levels of fear and worry.Footnote 7 Having recalled their fears experienced during the peak of the COVID‐19 pandemic, respondents feel more anxious and concerned when thinking about infectious diseases like COVID‐19. While they also report somewhat lower levels of happiness and hope and greater levels of anger and outrage, these differences are not statistically significant.Footnote 8 Most importantly for the theoretical pursuit of our study, however, we find that treated respondents do experience significantly higher levels of being afraid and worried in relation to infectious diseases. This proves that our experimental manipulation was successful.Footnote 9 This strengthens our confidence in the validity of our design and in the inferences we draw from studying the differences among respondents in the treatment and control groups with respect to their levels of support for illiberal norms and policies.

Figure 1. Means of emotional responses among treatment and control groups when thinking about infectious diseases like COVID‐19. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

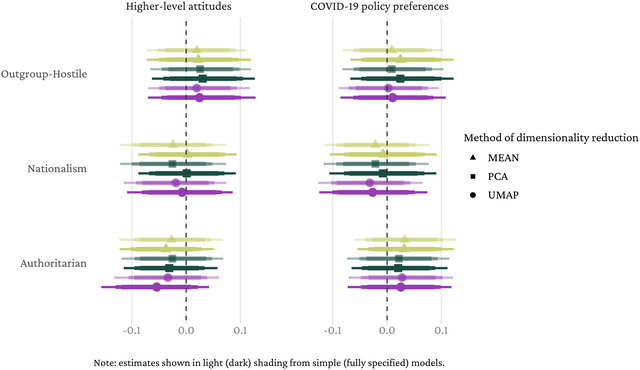

Can we observe any such effects of fear of COVID‐19 one and a half years after the onset of the pandemic? We next look at the variation that fear of COVID‐19 explains in the three conceptual dimensions of interest. Figure 2 shows that when under the impression of fear of COVID‐19, individuals do not express greater preferences for authoritarian policies during a crisis such as the COVID‐19 pandemic (see Table S6 in the SI for full results).Footnote 10 We also do not observe any secondary effects on their broader levels of right‐wing authoritarianism, outgroup hostility or nationalism.Footnote 11 All 90 per cent, 95 per cent and 99 per cent confidence intervals obtained from estimating our model on 5000 bootstrap resamples of the data include zero. We obtain the same results when accounting for any potential variation among treatment and control groups that may persist even after randomization (for balance statistics, see Table S3 in the SI).Footnote 12 We account for variation in respondents' gender, their age, their level of education, the degree of urbanity of their place of residence, self‐identification with an ethnic minority group, their level of religiosity, their satisfaction with the work of their respective government, whether they had been infected with the SARS‐CoV 2 virus that causes COVID‐19, whether they are vaccinated against the disease, and for the current COVID‐19 incidence rate in their region at the time of answering the survey.Footnote 13 The fully specified models including these covariates are shown in light shading in Figure 2. These results are also independent of the choice of a dimensionality reduction method.Footnote 14 We rely on three different such methods: the simple means of all items, their first principals of a principal component analysis (PCA), and their components obtained from a non‐linear algorithm that maximally preserves the data's dimensionality relying on stochastic gradient descent Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP).Footnote 15 Under any of these dimensionality reduction methods, the differences among respondents in the treated and control group are statistically insignificant.Footnote 16

Figure 2. The effect of fear of COVID‐19 on authoritarian, nationalist and outgroup‐hostile attitudes (left panel) and related COVID‐19 policy measures (right panel). Point estimates along with 90 per cent, 95 per cent and 99 per cent bootstrapped percentile confidence intervals obtained from 5,000 bootstrap resamples. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure S3 in the SI presents the corresponding results of a total of 72 different regressions fitted separately for each country. Figure S4 in the SI further shows that with respect to the various sub‐items there are also no statistically significant differences between those respondents who recalled their fears related to the COVID‐19 pandemic and those who did not, neither among Hungarian nor Romanian respondents. While this recall task was successful in elevating respondents' fears and anxieties related to infectious diseases like COVID‐19, these fears do not entail any downstream effects on individuals' levels of authoritarianism, outgroup hostility or nationalism. They also do not carry any impact on their preferences for related kinds of policies to fight the spread of the virus.

Conclusion

This study examines whether fears associated with the COVID‐19 pandemic amplify illiberal attitudes among citizens. Previous literature suggests that when people experience anxiety, they have a greater tolerance for violations of liberal democratic norms and are more likely to support discriminatory public safety measures. Exploiting the transient lower salience and presence of COVID‐19 in August 2021, we experimentally manipulate COVID‐19‐related anxieties among a random subset of respondents. We study two most likely cases in the European Union to see such attitudes amplify: Romania and Hungary are both countries that are challenged in their democratic consolidation. Our experimental manipulation is successful in increasing individuals' cognitive accessibility of the fears and anxieties they felt during the peak of the COVID‐19 pandemic. These anxieties, however, do not result in lower support for fundamental principles of liberal democracy and do not trigger higher levels of authoritarianism, nationalism and out‐group hostility.

In showing that citizens' liberal attitudes are less vulnerable to fears and anxieties than previously assumed, the results of our study appear encouraging for scholars concerned with the demand‐side determinants of democratic backsliding across Europe. Our results are also important for policy‐makers who aim to predict the political effects of imminent future epidemics. Future research should extend these insights to other political contexts that vary in terms of the prevalence of authoritarian inclinations or the extent to which democratic norms are internalized among citizens. While our study deliberately adopts a bottom‐up approach to analyse the effects of people's personal fears related to the COVID‐19 pandemic on their illiberal attitudes, more research is necessary to understand whether such anxieties could still pose a threat to citizens' support for liberal democracy when strategically engineered by elites (top‐down). Finally, the results of our study suggest that anxieties experienced during health crises, unlike anxieties experienced during economic crises or domestic crises resulting from terrorist attacks, are not associated with higher levels of anger – an emotion that is powerfully linked to illiberal attitudes (Vasilopoulou & Wagner, Reference Vasilopoulou and Wagner2017; Wagner, Reference Wagner2014). This finding may be of interest to scholars concerned with understanding the (lack of) transformative impact of crises on the cultural dimension of political conflict across Europe.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dorothee Bohle, Alice Iannantuoni, Erik Jones, Filip Kostelka, Markus Wagner, Sara Wallace Goodman, the participants of the Political Norms Workshop at the European University Institute, members of the Max Weber Eastern Europe Working Group at the European University Institute and the three anonymous reviewers for very helpful comments and feedback. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 885026) and from the European Union's Framework Programme for Research and Innovation Horizon 2020 under the Marie Sklodowska‐Curie (grant agreement No. 754388).

Open Access Funding provided by European University Institute within the CRUI‐CARE Agreement.

Data Availability Statement

All data and code are stored at Harvard Dataverse (DOI: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QKLSWY). The repository also contains a Dockerfile that allows to run all analyses in a reproducible environment.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure S1: Fear recall questions presented to respondents in the treatment group.

Table S1: Items measuring higher‐level attitudes related to right‐wing authoritarianism, outgrouphostility, and nationalism

Table S2: Items measuring right‐wing authoritarian, outgroup‐hostile, and nationalist COVID‐19 policy preferences

Table S3: Summary statistics by treatment and control

Figure S2: Heat map of correlations between different emotional states among treated and control respondents.

Table S4: Means and standard deviations of manipulated emotions among treated and control respondents

Table S5: First and second principal components of each conceptually relevant dimension and amount of variance explained by each component.

Table S6: Preferences for authoritarian, outgroup‐hostile, and nationalist COVID‐19 measures in response to fear of COVID‐19 (outcomes: PCA)

Table S7: Authoritarian, outgroup‐hostile, and nationalist attitudes in response to fear of COVID‐19 (outcomes: PCA)

Table S8: Preferences for authoritarian, outgroup‐hostile, and nationalist COVID‐19 measures in response to fear of COVID‐19 (outcomes: UMAP)

Table S9: Authoritarian, outgroup‐hostile, and nationalist attitudes in response to fear of COVID‐19 (outcomes: UMAP)

Table S10: Preferences for authoritarian, outgroup‐hostile, and nationalist COVID‐19 measures in response to fear of COVID‐19 (outcomes: mean)

Table S11: Authoritarian, outgroup‐hostile, and nationalist attitudes in response to fear of COVID‐19 (outcomes: mean)

Figure S3: The effect of fear of COVID‐19 on authoritarian, nationalist, and outgroup‐hostile attitudes (left panel) and related COVID‐19 policy measures (right panel).

Figure S4: The effect of fear recall on the various outcome items within each dimension.

Data S1