Introduction

In 2024, Switzerland was no longer grappling with immediate crises, but the long-term effects of overlapping crises remained palpable. The 2023 collapse of Credit Suisse Group AG—one of the country's two major banks—had required emergency measures from the federal government, the Swiss National Bank and the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) to fast-track its takeover by UBS Group AG in order to avert global financial turmoil and a severe economic downturn. Although the federal government provided public liquidity guarantees totalling CHF 109 billion, these agreements were terminated by UBS in August 2023, ending the Confederation's direct financial exposure.

Still, this most recent episode of state intervention—following earlier bailouts such as the 2008 UBS rescue, the 2022 stabilisation mechanism for Axpo Holding AG (the country's largest energy company), the 2020 aviation rescue and Covid-19 emergency loans—fuelled a growing public sentiment that ordinary citizens were being sidelined in favour of large corporations. Amid inflation, a higher cost of living and an increasingly acute housing shortage, many perceived that their needs were systematically deprioritised.

Swiss direct democracy has long served as a mechanism for channelling such public discontent, a function it once again fulfilled in 2024. In a historic vote, the popular initiative ‘Better Living in Retirement’—which introduced a 13th monthly pension payment through the national old-age and survivors’ insurance scheme (AHV/AVS)—was approved by a clear majority. For the first time, Swiss voters endorsed (i) a popular initiative launched by trade unions in direct opposition to the entire centre- to centre-right majority in the federal Parliament and the federal government and (ii) an initiative expanding public welfare spending. Exit polls revealed broad support for the measure, which voters saw as a necessary and tangible benefit for ordinary people—standing in stark contrast to the recurring state support for major corporations amid structural deficits and strained public finances. More broadly, this historic referendum outcome reflected signs of a crisis of representation in Switzerland, marked by declining party identification (Tresch et al. Reference Tresch, Rennwald, Lauener, Lutz, Alkoç, Benevuti and Mazzoleni2024), increasing media distrust (Udris & Eisenegger Reference Udris, Eisenegger and Newman2024) and growing misalignment between voters’ policy preferences and those of MPs and party elites (Freiburghaus & Vatter Reference Freiburghaus and Vatter2025). At the same time, Switzerland continues to rank among the highest in Europe for political efficacy, with citizens still widely believing that the political system enables people like them to have a real influence (Freitag Reference Freitag2023).

Neither the more medium- to long-term reverberations of recent overlapping crises nor the signs of a growing crisis of representation occurred in a vacuum. Rather, they highlighted Switzerland's deep interconnectedness with global developments, shaping domestic politics. This long-standing and intensive economic integration into supranational frameworks is bound to persist—now increasingly complemented by a legal and a political dimension, particularly in light of the ruling of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in Verein KlimaSeniorinnen Schweiz and Others v. Switzerland and the new EU–Switzerland deal. With negotiations concluded on 20 December 2024, the historically close partnership has, in the words of European Commission President von der Leyen, been taken ‘to a new level’ (European Commission 2024). However, ratification remains pending and will depend both on the Federal Council's ability to broker domestic compromises (e.g., to safeguard wage levels) and on the procedural mode of the 2028 referendum, which will ultimately determine the deal's fate.

Election report

Parliamentary elections

At the national level, no parliamentary elections were held in Switzerland in 2024.

Presidential elections

The President and the Vice-President of the Swiss Confederation are elected annually in a joint proceeding of the two chambers of the federal Parliament (United Federal Assembly). In Swiss-style consociationalism, presidential elections are not competitive and there is an ‘unwritten rule’ that Federal Councillors are elected to the said positions in order of seniority. On 11 December 2024, the outgoing Vice-President of the year 2024, Karin Keller-Sutter (FDP/PLR), Federal Councillor and Head of the Federal Department of Finance, was thus chosen President of the Swiss Confederation for 2025. She received 168 votes (68.3 per cent).

This rather low vote share reflects a broader trend: Presidential elections in Switzerland during the 2020s have seen average vote shares decline by over 12 percentage points, compared to the 2010–2020 period (Freiburghaus Reference Freiburghaus2023, Reference Freiburghaus2024a). Even though the President serves merely as primus inter pares among the seven Federal Councillors, the decline in vote share is revealing. It points to a growing reluctance among Swiss political parties to cooperate across ideological lines and to form broad, cross-party alliances in an era of increasing polarisation (Freiburghaus & Vatter Reference Freiburghaus and Vatter2019).

Regional elections

While shifts in vote shares from cantonal elections are often treated as harbingers of national outcomes, their predictive power is absent when they fall well outside the federal electoral cycle (Bochsler Reference Bochsler2019: 392). Nevertheless, given the substantial administrative and fiscal autonomy of Switzerland's 26 cantons—the cornerstones of Swiss federalism—political developments at the cantonal level remain important to monitor (Dardanelli & Mueller Reference Dardanelli and Mueller2019; see Freiburghaus Reference Freiburghaus2024b).

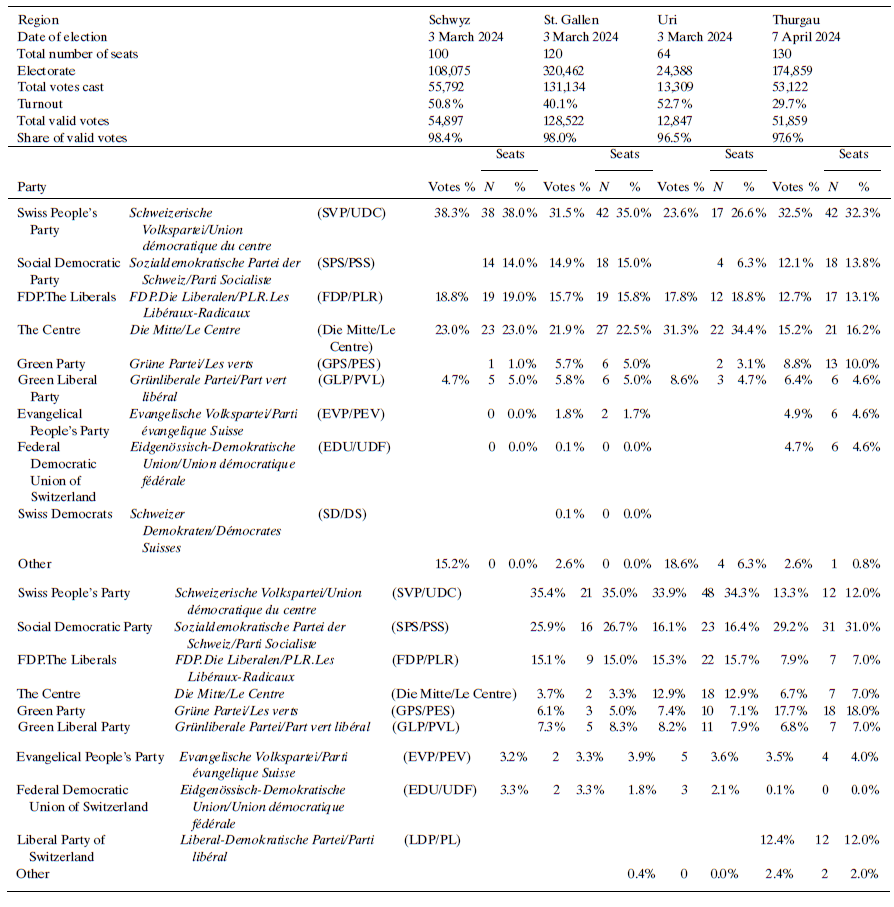

In 2024, cantonal elections were held in Schwyz, St. Gallen, Uri, Thurgau, Schaffhausen, Aargau and Basel-Stadt, in that respective chronological order (Table 1). Three major trends stand out: First, the far-right populist Swiss People's Party (SVP/UDC) made further inroads, gaining between one and seven additional seats in all of these seven cantons’ Parliaments—except Thurgau (minus three seats). The SVP/UDC thus consolidated its status as the most electorally successful party at the cantonal level, a position it has held only since the 2017–2021 cycle.Footnote 1 Second, the long-term electoral decline of the centre-right FDP/PLR continued, likely not despite, but because of its adoption of a tougher, SVP/UDC-inspired stance on immigration. This reinforces a well-established political science finding: mainstream centre-right parties that attempt to mimic far-right policy positions tend to lose electoral ground rather than gain it (see Krause et al. Reference Krause, Cohen and Abou-Chadi2023). Third, both parties from the green party family—the Green Party (GPS/PES), with its broad progressive agenda, and the Green Liberal Party (GLP/PVL), which combines environmentalism with fiscal conservatism—suffered losses in most of these cantons (Federal Statistical Office 2025). This trend reflects a recurring paradox in Swiss democracy: While environmental and climate protection consistently ranks as the second most important concern among Swiss citizens (UBS Sorgenbarometer 2024: 7), fewer voters are inclined to support green parties at the ballot box during elections. At the same time, however, voters often show greater willingness to approve ambitious environmental and climate-related proposals in referendums (Vatter et al. Reference Vatter, Arnold, Arens, Vogel, Bühlmann, Schaub, Dlabac, Wirz, Freiburghaus and Della Porta2024).

Table 1. Results of regional (i.e., cantonal: Schwyz; St. Gallen; Uri; Thurgau; Schaffhausen; Aargau; Basel-Stadt) elections in Switzerland in 2024

Notes:

1. Blank cells indicate that the political party did not participate in the election.

2. The residual category labeled ‘Other’ (Übrige) includes minor (or splinter) political parties grouped together by the Federal Statistical Office. Additionally, MPs without party affiliation are listed under this residual category. In the canton of Uri, four MPs are without party affiliation; in the cantons of Schwyz and St. Gallen, there is one MP each.

3. In the canton of Uri, the Left (including the SPS/PSS and GPS/PES) competed for votes on a joint list. As a result, the vote shares of the individual political parties on this joint list cannot be reported separately.

4. In the canton of Schwyz, the SVP/UDC, GPS/OES, EVP/PEV and EDU/UDF competed for votes on joint lists. Therefore, the respective vote share of the individual political parties on the respective joint lists cannot be reported individually.

5. In the canton of Thurgau, Aufrecht Schweiz has one MP. It is a minor party critical of COVID-19 protective measures and holds parliamentary representation only in this canton.

6. In the canton of Basel-Stadt, Aktives Bettingen and Volks-Aktion gegen zu viele Ausländer und Asylanten in unserer Heimat (VA) hold one MP each.

Source: Federal Statistical Office (2025).

Referendums

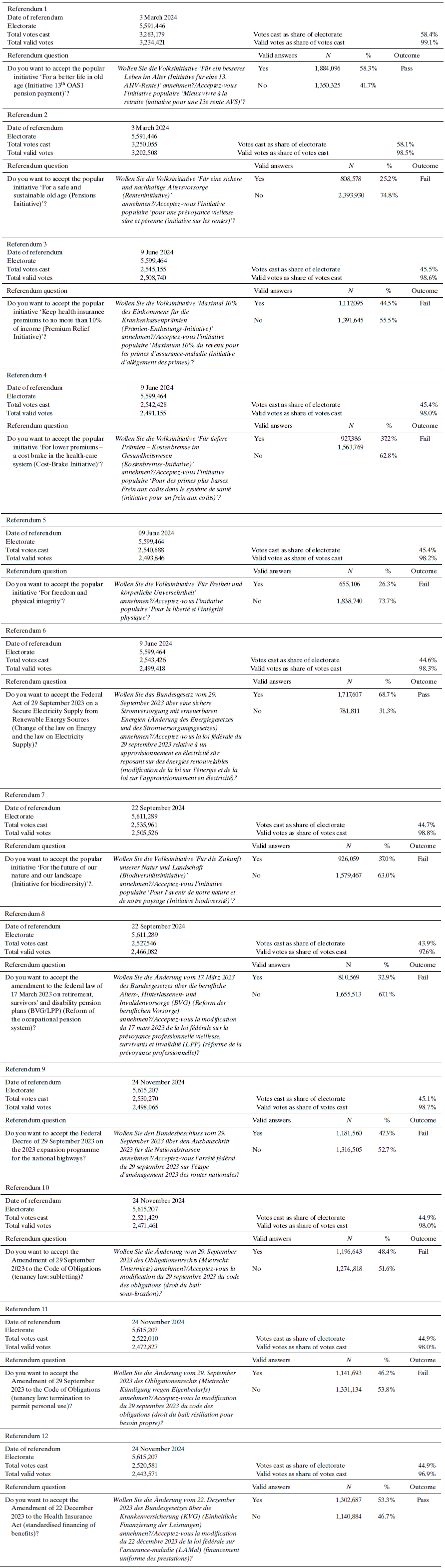

In 2024, Swiss voters voted on 12 nation-wide ballot proposals, that is, a total number that is well above the average of some eight nation-wide ballot proposals annually during the last three decades (Swissvotes 2025). Following the pre-fixed ‘referendum days’, Swiss voters headed to the polls four times (Table 2).

Table 2. Results of 12 referenda held on 3 March, 9 June, 22 September and 24 November 2024 in Switzerland

Source: Swissvotes (2025).

The first nationwide popular vote in 2024 took place on 3 March, with two proposals on the ballot. One of them, the popular initiative ‘Better Living in Retirement’, was launched by the trade unions. It called for the introduction of a 13th monthly pension payment through the AHV/AVS—Switzerland's first pillar of old-age provision. This measure was modelled after the widely established practice of the 13th monthly salary, an end-of-year bonus commonly granted to employees in December, typically equivalent to one month's regular salary. Approved by 58.3 per cent of voters, this popular initiative became only the 26th out of a total of 235 initiatives ever submitted to a vote to gain approval (11.1 per cent; as of 2024). Observers across the political spectrum unequivocally described the outcome as historic: It marked the first time a left-initiated popular initiative aimed at expanding welfare spending passed at the ballot box. According to exit polls, a clear majority of voters considered the additional pension payment a necessary response to the rising cost of living, which had been exacerbated by inflation. In contrast, the centre to centre-right opponents of the initiative criticised it for its ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach. They argued that the 13th monthly pension payment would benefit all individuals over 65, regardless of their financial situation (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Keller, Schena, Pagani, Tschanz and Rey2024a: 19–23).

The second popular initiative of that day, the ‘Pensions Initiative’, was launched by the FDP/PLR youth wing. It proposed gradually raising the retirement age from 65 to 66 over the next decade and then linking it to life expectancy. The initiative was clearly rejected (74.8 per cent ‘No’-votes). A majority of voters shared concerns voiced by the left and centre-left, arguing that raising the retirement age was unrealistic, especially given the difficulties older workers already face in the Swiss labour market (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Keller, Schena, Pagani, Tschanz and Rey2024a: 29–32).

On 9 June 2024, Swiss voters decided on three popular initiatives and one optional referendum.Footnote 2 The first initiative, launched by the SPS/SSP and titled the ‘Premium Relief Initiative’, aimed to cap health insurance premiums at 10 per cent of a household's disposable income. The proposal responded to rising premiums, which have increased by more than a quarter over the past decade, far outpacing wage growth. Although a growing number of people rely on state subsidies to cover their health costs, the initiative was rejected (55.5 per cent ‘No’-votes). Concerns about its estimated CHF 3.5–5 billion annual price tag resonated with voters—especially as the 13th monthly pension payment had just passed and funding sources for it remained unclear, raising fears of tax increases or spending cuts elsewhere (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Keller, Rellstab, Schena, Pagani, Roberts, Tschanz and Rey2024b: 23–27).

Given that healthcare consistently ranks among the top concerns of the Swiss population, The Centre party launched the ‘Cost-Break Initiative’ to curb rising healthcare costs. The proposal sought to require government intervention whenever healthcare spending grew by more than 20 per cent, compared to wage growth in a given year. However, the initiative failed to specify what measures authorities should take to reduce costs. This lack of clarity led to its rejection by 62.8 per cent of voters, who were unwilling to support such an imprecise proposal (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Keller, Rellstab, Schena, Pagani, Roberts, Tschanz and Rey2024b: 32–36).

The third popular initiative, named ‘For Freedom and Physical Integrity’, was launched by anti-vaccine activists and opponents of Covid-19 protective measures. It claimed that individuals should have full control over what is injected or inserted into their bodies, and that refusal should not lead to social or professional disadvantages. However, the initiative was overwhelmingly rejected by 73.7 per cent of voters. According to exit polls, most considered it exaggerated and unnecessary, as personal, physical and mental integrity are already protected under the Swiss constitution (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Keller, Rellstab, Schena, Pagani, Roberts, Tschanz and Rey2024b: 42–45).

The fourth and final vote on 9 June 2024 concerned an optional referendum on the Federal Act on a Secure Electricity Supply from Renewable Energy Sources. Aiming to accelerate Switzerland's path to net-zero emissions, the law mandates the production of at least 35 TWh of electricity from renewables by 2025 and 45 TWh by 2050. To meet these targets, regulations were eased to promote domestic renewable energy. While the law was widely supported by environmental groups (including Klimastreik Schweiz), economic stakeholders and all major parties except the far-right SVP/UDC, opposition largely came from the Franz Weber Foundation, who argued that large-scale solar plants, wind farms and 16 pre-defined hydropower projects would have harmful impacts on the environment. Nevertheless, 68.7 per cent of voters approved the bill, viewing it as a vital step towards sustainable energy and reduced reliance on imports (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Keller, Rellstab, Schena, Pagani, Roberts, Tschanz and Rey2024b: 51–55).

On 22 September 2024, two proposals were presented on the ballot. Switzerland ranks among the top four most developed democracies with the highest rates of threatened species across all categories of wildlife. In response to this, certain environmental and cultural heritage protection groups introduced a popular initiative, the ‘Biodiversity Initiative’. This proposal called for the allocation of adequate resources and space for nature, extending beyond existing protected areas, and sought stronger protections for both the landscape and the country's heritage. However, a majority of 63.0 per cent of the voters rejected the proposal, perceiving it as ‘too extreme’ amid concerns on the potential limitations it would impose on sustainable energy and food production, as well as restrictions for tourism (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Keller, Rellstab, Roberts, Tschanz and Rey2024c: 21–26).

On the same day, Swiss voters also decided on an amendment to the Federal Law on Retirement, Survivors’ and Disability Pension Plans (BVG/LPP). This government-backed reform represented a major overhaul of the second pillar of the Swiss pension system. Its objectives included securing the financial sustainability of occupational pension funds and improving pension conditions for part-time workers and low-income earners, who are often women. However, trade unions, left-leaning parties and a consumer protection organisation successfully triggered an optional referendum. Ultimately, voters rejected the highly complex amendment (67.1 per cent ‘No’-votes), primarily due to concerns that they would end up contributing more while receiving fewer benefits upon retirement (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Keller, Rellstab, Roberts, Tschanz and Rey2024c: 31–35).

On 24 November 2024, four optional referendums were held, the first concerning the Federal Decree on the 2023 Expansion Programme for the National Highways. In an effort to address road congestion, the government proposed six motorway expansion projects, with an estimated cost of approximately CHF 5 billion. However, the plan faced opposition from VCS Verkehrs-Club der Schweiz, a long-standing advocate for sustainable transportation. The organisation launched an optional referendum, supported by the SPS/PSS, the GPS/PES, the GLP/PVL and various pro-environmental groups. Ultimately, 52.7 per cent of voters rejected the government's proposal. The main reasons cited were the anticipated negative environmental impacts of increased private motorised traffic and doubts about the plan's effectiveness—many voters believed that more lanes in key motorway stretches would simply lead to more traffic. In contrast, concerns over the financial cost of the project were relatively less influential in the public's decision (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Keller, Schena, Rellstab, Tschanz and Rey2024d: 21–25).

With nearly six in 10 Swiss inhabitants living in rented housing (Europe's highest share), tenants’ rights are a recurring political issue. Two proposed amendments to the tenancy law in the Swiss Code of Obligations were put to a vote: One would have allowed landlords to more easily prohibit subletting, the other to more readily terminate leases early for personal use. The tenants’ association launched a referendum against both provisions, which were rejected by 51.6 and 53.8 per cent of voters, respectively. A majority prioritised tenant protection over expanding landlords’ rights, especially given the challenges faced by those unable to afford homeownership (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Keller, Schena, Rellstab, Tschanz and Rey2024d: 30–34, 38–42).

The fourth and final optional referendum on 24 November 2024 concerned an amendment to the Federal Health Insurance Act (KVG/LAMal), introducing a standardised financing model for healthcare services. Aimed at encouraging outpatient treatments and reducing reliance on costlier inpatient care, the reform proposed equal cost-sharing between cantons and insurers for both types of services. A majority of 53.3 per cent voted in favour, viewing the measure as a meaningful step towards curbing rising health insurance premiums (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Keller, Schena, Rellstab, Tschanz and Rey2024d: 47–50). It marked the first healthcare reform in more than 10 years to receive public approval.

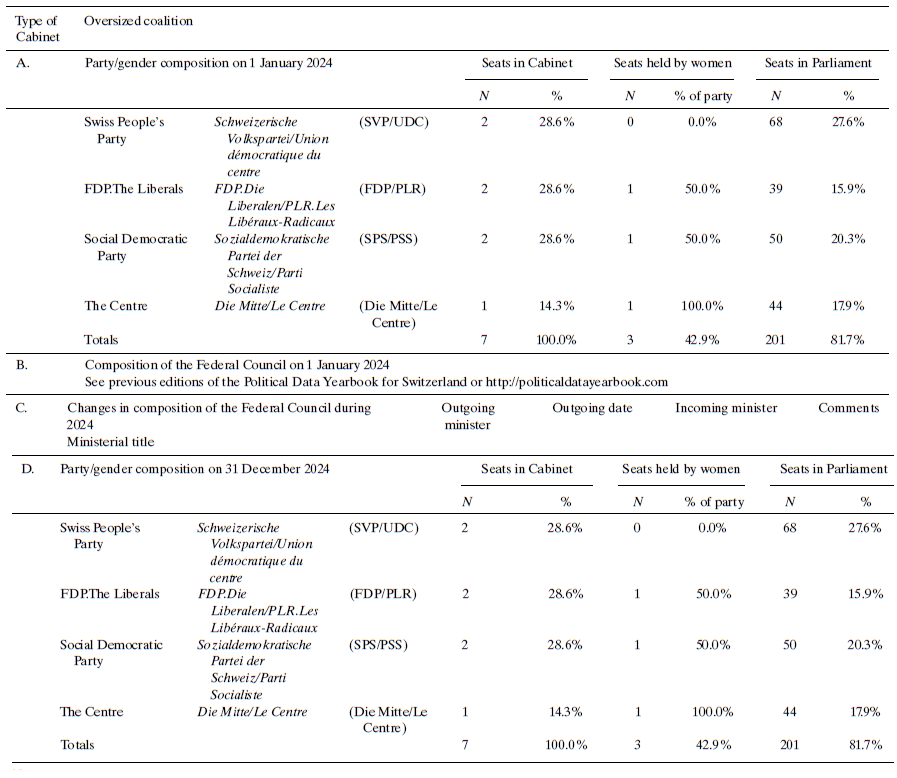

Cabinet report

There were no changes in the Cabinet composition of the Federal Council in 2024; the same seven members remained in office from 1 January to 31 December (Table 3).

Table 3. Cabinet composition of the Federal Council in Switzerland in 2024

Notes:

1. ‘Parliament’ refers to the United Federal Assembly and thus consists of the seats in both chambers (i.e., National Council and Council of States), adding up to a total of 246 seats.

2. The President and the Vice-President of the Swiss Confederation rotate annually. Since they are elected from the seven members of the Federal Council, their one-term-period-of-office does not change the party/gender composition of the Cabinet (see section ‘Election Report: Presidential Elections’ for details).

Source: The Federal Council (2025a).

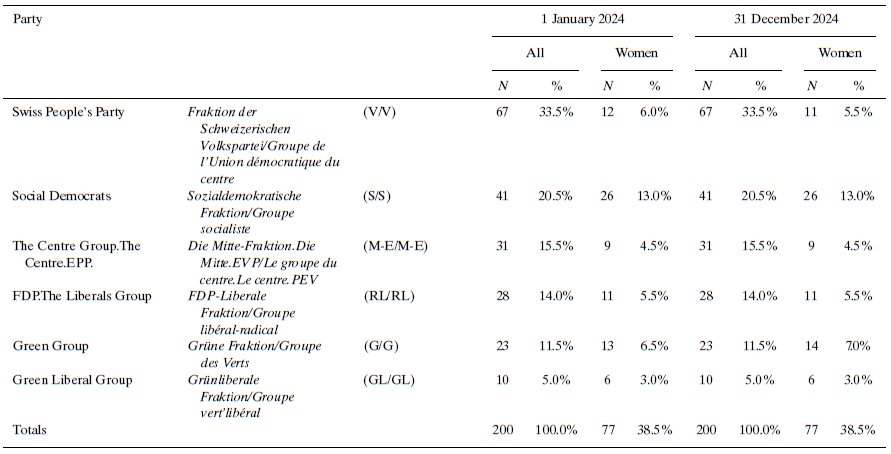

Parliament report

In 2024, three members of the National Council (lower house) left office—either due to a complete withdrawal from politics in the cases of Bastien Girod (GPS/PES) and Martina Munz (SPS/SSP), or as a result of election to a cantonal government, as in the case of Martina Bircher (SVP/UDC), who joined the government of the canton of Aargau. However, these departures did not alter the party or gender composition of the chamber (Table 4).

Table 4. Party and gender composition of the lower house of Parliament (Nationalrat/Conseil national) in Switzerland in 2024

Note: Parliamentary groups are not identical to political parties, as either MPs who belong to the same political party or MPs who share similar ideological views may get together to form a parliamentary group.

Source: The Federal Assembly (2025).

In the Council of States (upper house), no legislative turnover occurred during the year (Table 5).

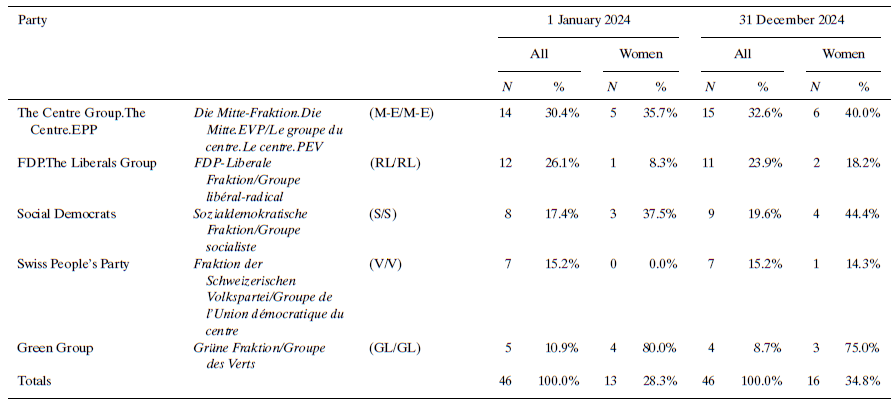

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the upper house of Parliament (Ständerat/Conseil des États) in Switzerland in 2024

Notes:

1. Councillor of State Tiana Angelina Moser from the Green Liberal Party (GLP/PVL) decided to join the Green Group.

2. Councillor of State Mauro Poggia from the Mouvement Citoyens Romand (MCR/MCR) decided to join the Group of the Swiss People's Party.

Source: The Federal Assembly (2025).

Political party report

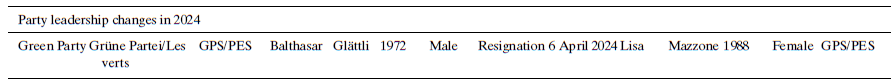

In 2024, the GPS/PES—the largest opposition force in Switzerland's non-parliamentary and non-presidential governmental system—underwent a leadership change (Table 6). Outgoing leader Balthasar Glättli had led the party, as campaign manager, to a historic record result in the 2019 federal elections, which earned him the party leadership in 2020. Although he secured the party's second-best result in 2023, the Greens still lost ground, compared to their 2019 high (Freiburghaus Reference Freiburghaus2024a), prompting Glättli to describe himself as the ‘face of the defeat’. This, combined with polling data indicating that even Green voters viewed him as lacking political influence, increased pressure for his resignation. On 14 November 2023, Glättli announced he would step down in spring 2024.

On 6 April 2024, the GPS/PES's delegates’ assembly unanimously elected Lisa Mazzone as the new party leader. A former member of the National Council (2015–2019) and the Council of States (2019–2023), Mazzone is regarded as the beacon of hope of the party's progressive wing and is widely recognised for her political talent. She quickly built a strong reputation in the Federal Assembly, becoming, within only two years of her tenure, one of the 15 most influential MPs (von Burg et al. Reference von Burg, Skinner and Tischhauser2017). However, she narrowly lost her seat in the 2023 federal elections in a tightly contested run-off. At the time of her election as party leader, she was therefore not a member of the Federal Assembly—an uncommon situation not seen in any major Swiss political party since 1999/2000.

Institutional change report

Since successful popular initiatives and mandatory referendums automatically result in constitutional amendments, the Federal Constitution was formally amended once in 2024. This change followed the approval of the popular initiative introducing a 13th monthly AHV/AVS pension payment (see section ‘Referendums’). Just one amendment in a year falls slightly below the post-2000 average of approximately 1.7 constitutional changes annually (Swissvotes 2025).

More noteworthy, however, are the significant institutional reforms that were widely deemed necessary but failed to materialise. At the national level, no major overhaul of direct democracy occurred, despite a serious scandal in 2024 that exposed vulnerabilities in the system. The country was shaken by what became known as the ‘signature scam’ (‘Unterschriften-Bschiss’, named Switzerland's 2024 Word of the Year). Investigative reporting by two award-winning Swiss journalists revealed that commercial signature collectors had forged thousands of signatures to prompt a referendum—signatures that have traditionally been gathered by volunteers. Several popular initiatives are suspected of having reached the ballot fraudulently, prompting an investigation by the Office of the Attorney General (Häfliger & Knellwolf Reference Häfliger and Knellwolf2024).

The scandal highlighted a structural weakness: During the signature verification phase, municipalities check signatories’ addresses and birthdates but not their actual signatures. This process remains entirely paper-based. A secure digital identity system and an e-collection procedure would be necessary to close this gap. However, Switzerland's e-ID is not expected to be available until late 2026, and it remains uncertain whether it will be authorised for use in digital signature collection.

A second set of long-anticipated but unrealised institutional reforms relates to measures deemed necessary to prevent systemic disruptions in the global banking sector—particularly in light of the 2023 collapse of Credit Suisse Group AG (Freiburghaus Reference Freiburghaus2024a). In response, the Federal Assembly established a parliamentary investigation committee (PUK/CEP)—Switzerland's most powerful oversight instrument, capable of summoning witnesses and accessing confidential Federal Council documents. This marked the first such committee in almost 30 years and only the fifth instance since the Swiss Federation's founding in 1848.

Despite the PUK/CEP publishing its final report in December 2024, none of the institutional shortcomings it identified have yet been addressed. These include (i) inadequate coordination and crisis-management capacity within Switzerland's non-parliamentary, non-presidential government structure (Vatter Reference Vatter2024); (ii) the limited authority of the FINMA to monitor and sanction failing bank management (PUK/CEP 2024); (iii) and the influence of vested interests within the semi-professionalised Federal Assembly—particularly the close ties between the banking sector and members of the far-right SVP/UDC and the centre-right FDP/PLR (Huwyler et al. Reference Huwyler, Turner-Zwinkels and Bailer2023; see BBl 2025 515).

At the cantonal level, the most significant institutional non-reform was the failed overhaul of the cantonal constitution in the bilingual canton of Valais. In 2018, voters had overwhelmingly approved the launch of a comprehensive reform process to replace the outdated 1907 cantonal constitution. An elected constitutional assembly worked over 4.5 years, culminating in a draft of a new cantonal constitution that was submitted to referendum in March 2024. However, a majority of 68.1 per cent rejected the new constitution—thereby blocking a broad set of progressive reforms, including local voting rights for non-Swiss residents, a constitutional commitment to respecting planetary boundaries, digital integrity, parental leave and the right to a freely chosen end of life. The outcome raised fundamental questions about the feasibility of institutional reform in Switzerland: First, such reforms have historically only succeeded within the framework of a full constitutional overhaul enabling package deals; and second, the process in Valais, widely seen as highly inclusive, suggests that even innovative, participatory design may not overcome political resistance.

Issues in national politics

As the most globalised country in the world (Freiburghaus & Mueller Reference Freiburghaus, Mueller, Emmenegger, Fossati, Häusermann, Papadopoulos, Sciarini and Vatter2024: 779) and often dubbed the ‘world champion of direct democracy’ (Altman Reference Altman2011: 49), Swiss politics are shaped both by global interdependence and by the high volume of popular initiatives and referendums. This dual dynamic—external influence and internal ballot-box induced pressure—is exemplified by the following three issues, widely regarded as the most significant in Switzerland in 2024.

The first key issue was the ruling of the ECtHR in Verein KlimaSeniorinnen Schweiz and Others v. Switzerland on 9 April 2024 (Blattner Reference Blattner, Bönnemann and Tigre2024). The Verein KlimaSeniorinnen, an association of 2400 older Swiss women, sued the federal government for failing to fulfil its obligations to mitigate climate change—arguing that this inaction violated several of their human rights, given that older women are disproportionately at risk during increasingly frequent and intense heatwaves caused by climate change. The ECtHR's top bench ruled in favour of the applicants, finding that the federal government's inaction on climate constituted a violation of the applicants’ right to respect for private and family life (Art. 8 European Convention of Human Rights, ECHR). This ‘landmark climate ruling’ (The New York Times 2024) made international headlines as the first time an international court held a state legally accountable under human rights law for failing to meet climate targets (see Kwai & Bubola Reference Kwai and Bubola2024). The judgement has been widely seen as increasing judicial pressure on governments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and is expected to influence other pending climate litigation globally.

Domestically, the ruling also underscored Switzerland's deep integration into international legal frameworks. The KlimaSeniorinnen had initially filed their case with Swiss authorities, arguing that the government failed to protect their fundamental rights. However, both the Federal Council and the Swiss Supreme Court either declined to hear the case or dismissed it. Only after exhausting all domestic remedies were the plaintiffs able to appeal to the ECtHR, exercising rights afforded by Switzerland's ratification of the ECtHR. Given the unprecedented nature of the ruling and the widespread deep scepticism within large segments of the Swiss public towards judicial decision-making—which many believe should reside with the citizenry through direct democracy (embodied in the notion of vox populi, vox dei)—the ruling sparked fierce domestic criticism. This criticism mainly came from centre- to centre-right parties, with some prominent members joining the far-right SVP/UDC, a party that has long vehemently attacked supranational courts for ‘undermining of national sovereignty’.

The second significant issue was the ongoing debate over Switzerland's strained federal budget and long-term fiscal stability. A 2024 report by the International Monetary Fund (2024) acknowledged that Swiss fiscal policy remains well-anchored by the debt brake but warned that rising expenditure pressures necessitate measures to eliminate structural deficits. The federal government—particularly the influential Finance Minister—shares this assessment, identifying the newly introduced 13th monthly AHV/AVS pension payment as an ‘additional burden on the federal budget’ (The Federal Council 2025b).

To stabilise public finances, the Federal Council commissioned an expert group to conduct a comprehensive review of public tasks and subsidies. Based on this group's recommendations, the Federal Council unveiled a cost-saving plan on 20 September 2024: the ‘Entlastungspaket 2027’, comprising 60 measures to reduce federal spending by CHF 3.6 billion annually from 2027, increasing to CHF 4.6 billion by 2030 (The Federal Council 2024a).

While military spending was exempt, many other areas faced proposed cuts—including federal contributions for supplementary childcare and climate protection subsidies, the reduction of refugee integration lump-sum payments, a freeze on development aid and reduced funding for infrastructure and transport. The plan sparked widespread criticism: The cantons, typically acting as lobbyists (Freiburghaus Reference Freiburghaus2025), warned of cost-shifting from federal to regional levels, while researchers cautioned that austerity measures could have adverse socio-economic effects, drawing on international evidence. In response to mounting dissatisfaction, the federal government pledged to review and possibly revise the proposal. By the end of 2024, it thus remained unclear which policy areas would ultimately face cuts and to what extent.

The third major issue in 2024 concerned Swiss–EU relations, which saw an unusually eventful year. Following the Federal Council's 2021 unilateral termination of negotiations on an overarching institutional framework agreement, and a new ‘common understanding’ with the European Commission reached in 2023, the Federal Council approved a definitive negotiating mandate with the EU on 8 March 2024 (The Federal Council 2024b).

At the heart of the mandate was a so-called ‘package approach’. Framed as a bold solution to a seemingly intractable problem, this approach aimed to reconcile Switzerland's interest in tailored access to the EU single market with the EU's insistence on preserving the market's integrity and uniform rule application. To address both sides’ concerns concurrently, the package included seven elements, grouped under four broad goals: (i) normalisation, through ‘institutional elements’ covering dynamic adoption of EU law, uniform application and dispute settlement; (ii) stabilisation, ensuring continued Swiss participation in, for example, free movement of persons or Horizon Europe; (iii) further development, including new agreements on electricity, food safety and health; and (iv) a newly established regular, high-level political dialogue, including regular Swiss contributions to EU cohesion efforts (The Federal Council 2024c).

Negotiations were concluded in less than eight months, and on 20 December 2024, Viola Amherd, President of the Swiss Confederation, and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, presented the new EU–Switzerland deal as ‘historic […], enabling both sides to fully harness the potential of [their] close collaboration’ (European Commission 2024). Whether the deal will be approved in a referendum planned for 2028—and thus ultimately enter into force—depends on two key factors: First, the Federal Council must broker domestic compromises, particularly between employer associations and trade unions to ensure decent wage levels amid increased competitive pressures (Good et al. Reference Good, Walter, Wasserfallen, Heidbreder and Kassim2025). Second, the outcome hinges on the referendum procedure that will ultimately be determined by Parliament. While a simple majority of voters would likely suffice for approval, a double majority, requiring both a majority of voters and a majority of the 26 cantons, would significantly raise the bar (Freiburghaus & Vatter Reference Freiburghaus and Vatter2024).

Acknowledgments

Open access publishing facilitated by Universitat Bern, as part of the Wiley - Universitat Bern agreement via the Consortium Of Swiss Academic Libraries.